Alexander Douglas

LANE an imprint of

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Alexander Douglas, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 12/14.75pt Dante MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978– 0– 241– 64821– 6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my wife, Lauren Douglas: We are Zhuang Zhou, and we are the butterfly.

Long ago, in a mythical realm in what is now China,1 there were three emperors: Shu, Hu and Hundun. Shu was the Emperor of the Southern Sea. Hu was the Emperor of the Northern Sea. Between them was the Centre – the territory of Hundun. The two emperors of the seas frequently met in the Centre, where Hundun always welcomed them with perfect hospitality. Shu and Hu, like us, had openings in their heads: eyes, ears, mouth and nostrils. Hundun, however, had none. He was blank and featureless. One day, Shu and Hu decided to bore holes into him, so that he too could have features like theirs. Each day, they drilled a new hole. And on the seventh day, Hundun died.

One clue to the meaning of this mysterious story lies in the name Hundun (hun 混 dun 沌, or ‘mixture’, ‘chaos’). The meaning evoked is something like ‘roly-poly’ or ‘hotchpotch’. Pronounced in Cantonese, it is ‘wonton’ – the name of the famous Chinese dumplings, which can wrap up a variety of fillings.2 Thus, Hundun’s name implies that even though he is unformed, he contains potential forms, as an uncarved block contains all the shapes a sculptor could make from it.3 Some scholars therefore suppose that this story might be a parody of older creation myths, which often represent the formation of the cosmos from chaos, illustrated through the murder or casting out of a wayward figure personifying chaos.4 In this case, Hundun personifies the primal chaos from which the cosmos is formed, through the violently creative act of Shu and Hu.

But I find in Hundun’s story something more personal. It is the story of each one of us. Hundun’s facelessness is a metaphor for a lack of definite identity.5 In puncturing Hundun, Shu and Hu give him an identity by which he can be recognized. But in the process, Hundun dies. This is the story of how we receive identity from our peers and how, when we do so, something is destroyed within us. The power of the undefined is lost by being forced into something definite. Our inner being is not a blank emptiness; it is an all-embracing multiplicity: Hundun is wonton. Against Identity is about how our inner Hundun can be revived, and how destructive the process of losing it can be.

This book examines a philosophy in the ordinary sense of the word: a certain way of looking at life and the world. Good philosophy should provide us with a feeling of clarity and ease – a new understanding and an ability to navigate life wisely.

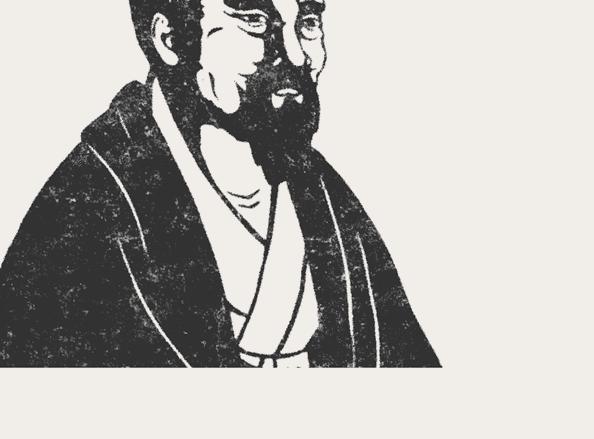

The philosophy studied here is found in the works of three thinkers, writing in entirely different cultures and times. We start by contemplating the ancient East Asian philosopher Zhuangzi (pronounced in modern Mandarin as ‘joo-ang zuh’),6 before moving on to the Dutch Republic (perhaps the first modern nation) with philosopher Benedict de Spinoza, and then, finally, we arrive in the near contemporary period, with twentieth-century French theorist René Girard. I propose that all three thinkers faced similar problems in their lifetimes and diagnosed the same ills in their society, which led them to develop strikingly similar philosophies against identity.

The philosophy I find in all three thinkers can be sketched out as follows. Each of us is born with a deep biological urge for self-preservation. But consciously pursuing self-preservation requires some notion of who or what our self is. Here is our predicament. In the beginning, we are not sure of who we are.

Some believe that we can find out by introspecting and looking within to find our true self. But Zhuangzi, Spinoza and Girard disagree. Look within, they would say, and you will find a mess. Introspection reveals only a confusion of qualities. There is no map highlighting which qualities truly define us: which are our defining traits and which our fleeting states. Nor does who you happen to be right now define who you essentially are. You might not yet have become your true self – and you may still have the enigma of yourself to solve, as Saint Augustine put it.7

Since introspection reveals nothing, we have no choice but to look outwards, to others – real or fictional – as models of our true being. Find the ones who stir your admiration and take them as exemplars for your best self. We do this as children, when we play at being superheroes, parents, monsters, criminals, police. We do not stop when we grow up. It just stops being a game. When people say, ‘I know who I am’, what they mean is that they know who somebody else is. They have decided to be that: a borrowed self to fill the blank inside. But this – our profound ontological unoriginality – is an embarrassing fact, which we go to some lengths to hide from ourselves. Proving the theory that drives this philosophy therefore requires more than just rational argument. It is also necessary to overcome some of our psychological defence mechanisms. ‘Individualism is a formidable lie,’ as Girard said.8

The reappearance of this same philosophy in diverse times and places suggests that it is a piece of wisdom transcending local culture. But the three epochs that Zhuangzi, Spinoza and Girard lived through have something important in common. They were all eras in which a social order had fallen apart, or was falling apart. Zhuangzi wrote his major works sometime during the Warring States period of pre-China, following the collapse of a great empire and its associated social hierarchy.

Spinoza conceived his main ideas in the Dutch Republic, following the breakup of Western Christendom and at the beginning of capitalist modernity. And Girard worked in France and the United States in the later twentieth century, where new ideals of self-invention arose in the ruins of the Second World War, the process of decolonization, and a revolution in media technology.

In each of these ages, philosophies of individualism developed, celebrating and justifying the power of individuals to decide who to be, newly liberated from regimes of social control. The philosophy examined here warns of the danger of these individualistic philosophies and presents an alternative. The alternative is not a reversion to a traditional social order. Rather, it aims to understand how identity is formed, in order to escape it altogether.

Some psychologists distinguish between identity and self. Your identity is a specific concept of your persona, role or social position. Your self is the subject that inhabits and operates your identity.9 But selves are always known under identities. To know any object, we must identify it under some concept or description. ‘Self’ and ‘identity’ are thus often used interchangeably in this book, though occasionally it is recognized that there is a portion of the self that eludes – and exists beyond – any identity. The starting point of the philosophy explored here is the theory that identity – the concept or description under which the self is known – comes from the observation of others. The process by which essential identity is thus modelled and then imposed is destructive. Really it is a form of spiritual violence, which often leads to violence of a more concrete kind.10 It is also an ultimately doomed enterprise. No matter how deeply you push yourself into your chosen essential identity, there will always be some residue that refuses to be absorbed – some

Introduction: Identity Kills remainder that cannot be resolved.11 This is the portion of the self that lies, always, beyond identity.

The way out of this destructive and unsatisfying predicament must be by tracing the problem to its root: our original hunger for being. Since mere being is an empty concept, wanting to be must mean wanting to find your true identity, which can only come from outside of us. If we were instead to strive to overcome the hunger for identity, then we could remain happily indefinite and enjoy whatever concatenation of accidents happens to be bestowed upon us by external circumstances and spontaneous inner drives.

This is how we can understand the story of Hundun’s death. The faceless, indefinite, identityless Hundun is amicable and hospitable. Shu and Hu meet in his territory because, perhaps, they are rivals to each other, and Hundun’s territory is neutral ground. Hundun avoids getting caught up in their conflict and is welcoming to both sides, perhaps because of his lack of identity. By piercing Hundun, Shu and Hu commit him to a distinct identity, a desire driven by the fact that they have faces themselves. They want to work out who he is, perhaps to decide whose side he is really on. Hundun represents everything in us that is unique and undefinable, impossible to fully capture in any concept or definition, impossible to recruit to any collective identity.12 Imposing identity upon us reduces us to what can be defined and recognized. Stamping somebody with a face kills the Hundun in them.

Identity, however, is not merely destructive. It also provides moral guidance in our lives. Knowing who you are provides a sense of what you should do in a given situation.13 Zhuangzi, Spinoza and Girard go further and propose that it is only through identity that we decide what to do. They hold to a theory of

metaphysical desire. The theory is, roughly, that while our basic appetites are biologically determined, our desires beyond these basic appetites arise from a fundamental psychological drive for identity – a drive to be a certain sort of person. What we desire is, first of all, to be something rather than to possess something or do something.14 I want to eat because I want to be a thriving organism; I want to eat foie gras because I want to be a member of a certain social group; I want to listen to black metal music because I strive to be the sort of person who listens to this genre – to have that identity, often with the clothes to match.

Why I should strive for one particular identity rather than another is not yet clear. But we can understand why I should want some identity. If I am not someone or other, I can feel like I am nobody – or nothing in particular. I can suffer from what psychologists call an ‘identity deficit’.15 As Spinoza puts it in his philosophical masterpiece, Ethics Demonstrated in Geometrical Order (1677), each thing strives ‘to persevere in its being’ (Ethics, 3p6). But here ‘its being’ refers to essential identity. After all, surviving cannot just mean remaining in existence as anything whatsoever, otherwise turning into a corpse would count as surviving. Surviving means remaining as what you truly or essentially are. Some notion of essential identity is necessary to define what you are striving to be, and to remain as. Desires grow from the root of this striving. You decide who you are, and then this determines how you want to act, what you want to possess, who you want to connect with, what you want to believe.

Identity also serves an important social function. Anthropologists studying human violence have proposed that there are two quite different types of violence.16 We humans seem to have developed our special ability to avoid one sort of violence by harnessing the power of another. The first sort is known

Introduction: Identity Kills

as reactive violence, an antisocial kind of violence that flouts the rules and conventions that govern a society – violence that is illegal, impolite, or in some way ‘not the done thing’. The second sort, proactive violence, is violence used to police and enforce the same rules and conventions. Human communities use proactive violence to punish and discourage reactive violence, forming coalitions to punish those who break the rules. But since we cannot always observe each other’s behaviour, societies in practice police the identities of their members. Those whose character makes them seem likely to transgress, who do not seem to be the right sort of person, are far more likely to be accused of breaking the rules and often punished as a precautionary measure.

Identity management is thus part of how communities are governed and maintained. Passing through the social filter without being targeted for proactive violence requires us to maintain a healthy profile as a friend of the community. Developing an identity – the right sort of identity – is necessary to avoid proactive violence, although in modern communities genuine violence can be replaced by more insidious psychological warfare. Yet the process by which identity is imposed is also a sort of violence, illustrated in the story of Hundun. All three thinkers studied here believed that violence is found at the origin of most social institutions. The Hundun story has been read as a warning for how humans are initiated into social institutions and what is lost in the process: it is a fable of a fall and loss of innocence.17

Identity is not just produced by violence; it also inspires it. This is because it is tied up with distinction and comparison. To identify yourself is also, inevitably, to identify others. Shu and Hu could not have faces without feeling the need to give

one to Hundun. If you define yourself by your ethnicity or your taste in music, then you ipso facto demarcate yourself against others who do not share in that identity. Here we have the basis for division and intergroup conflict. Groups that identify themselves – whether by ethnicity, politics, clothing, sports teams, opinions on metaphysics, or precise predictions of the consequences of economic policy – easily end up at war with groups that identify differently.

One reason for this is simple enough. Intelligent people often turn out to be surprisingly unresponsive to valid arguments and solid evidence. But for many people, their beliefs and practices define who they are. They belong to their essential identity. And since, as we have seen, surviving means remaining as what you essentially are, threats to such essential beliefs and practices appear as threats to survival. Arguments and evidence are up against something much more powerful than they can ever be: the fear of death, the survival instinct. Threatening your identity is threatening your very being.

Thus, the thirst for identity brings the constant risk of violence. When pursuing goal x is part of the essential identity of one group, and pursuing goal y – inconsistent with x – is part of the essential identity of another, then the groups are in a war of extermination. The goals x and y might not seem particularly important, yet by becoming entrenched in the identities of the combatants they take on existential significance. Winning becomes a matter of survival.

In such cases physical violence might not occur, but the tone of the disagreement will match that of a violent conflict. Belligerents can experience disagreement as violence: threats to ideas that define their very being. They will feel no hesitation in throwing out taunts, insults and condemnations. These harsh tactics make much more sense than rational argument,

Introduction: Identity Kills

once we recognize what the stakes are. If changing somebody’s mind requires you to change who they think they are, then what you need is not rational arguments but ways to undermine your opponents’ sense of self or self-respect. Aggression, performative contempt, public humiliation – anything that might fill the targets with enough shame to want to be somebody else – these are the right tools for the job.

Put bluntly, the struggle for identity is what leads people to fight so brutally over minutiae or matters that seem much too uncertain to be definite about. We find here a powerful diagnosis of our philosophical sickness.

Our philosophical sickness is manifested in many ways. At present, a hot political topic is polarization. The theme of the 2023–4 United Nations Human Development Report is ‘reimagining cooperation in a polarized world’.18 The report explains how people become polarized when they incorporate political opinions into their identities.19 If your whole identity is based on a political opinion, then you are likely to develop an extreme version of it, just as somebody who makes exercise their whole identity will progress inexorably from 10k park runs to ultratriathlons, while someone who makes recreational cannabis their whole identity will end up with t-shirts, wallets, bumper stickers and bongs emblazoned with the sacred leaf. When your political beliefs become part of who you are, anyone who disagrees, or even anyone insufficiently interested in the topic, is at risk of a heated conversation or an uninvited lecture.

In the case of political views, the UN report explains how polarization is a serious barrier to collective action. People can hardly work or compromise with others when their entire identity is based on opposing them. Identity stops the world from working together to solve its common problems. It also

makes people vulnerable to misinformation, thus reinforcing polarization by making each party feel like all the facts are on their side. Healthy scepticism about confirming evidence is hardly compatible with an identity-driven need to hold a certain belief or attitude.

To draw an example from my own experience, during a dispute over UK higher education pensions, driven by legitimate concerns over some proposed reforms, I saw one professor tweet a wild misinterpretation of her pension statement. She somehow inferred that her total retirement income would be £3700 per year. This attracted a chorus of outraged and supportive commentary. But the figure quoted was much less than the professor was paying in contributions per year, let alone what her employer was contributing. If both employee and employer were really paying in much more than the pension was due to pay out, why would the professor not have put the same money into savings instead? Why did the crowd of supportive and outraged academics – specialists in rigorous thinking – not ask this question, or at least recommend to the professor that she withdraw from a scheme that, apparently, lost all of her employer’s contributions and some of her own? Why did they not wonder whether, perhaps, there might have been a mistake in her calculation?

The reason, I think, is that the dispute had become so polarized that outrage about pensions had become an identity for many academics: it defined their sense of self-worth in the face of an attack by consecutive governments intent on reducing their public funding. They were ready to believe anything to retain that identity, even things that patently made no sense. I have no doubt that I have believed equally absurd things in the pursuit of a particular political identity. Or rather, I have expressed such beliefs; when it comes to identity, we often do

Introduction: Identity Kills

not get as far as thinking about whether we can really imagine the beliefs we loudly profess to as actually being true.20 Political commitments, often reasonable in themselves, can lead us to agree with nearly anything said by those we take to be on our side. Here, I chose to spotlight an elite group – academics – to show that neither education nor intelligence makes the mind more resistant to polarization. Even when people have the most to gain from working together, they instead polarize into warring tribes and twist the facts to show that they are right and good, while their opponents are wrong, stupid and evil.

Both philosophy and life tell me that this fight for and against identity is universal across humanity. I was raised in a multiethnic household and grew up on different continents – Australia, Asia and North America, eventually ending up in Europe – and in that time, I have been more struck by the deep similarities among people than their superficial differences. My parents set the example of delighting in, rather than resenting, those differences. But I have also experienced all these cultures as an outsider. I first left my native country, Australia, as a young child, and I am not even very native to Australia – my mother was a first-generation immigrant from Macau, and my father’s family had only migrated from Scotland a few generations back. Being an outsider makes it difficult to succeed in the specific status-game of culture. First you have to learn what the game is. Moving from understated, self-effacing, indirect Java, it took me a while to understand the bold, explicit game of selfpromotion required in Washington DC . Initially I could not control whether I signalled the healthy ambition and self-belief that was expected of me or arrogant showboating that nobody liked; to me they looked the same. Returning to Australia for university required a talk from my father about what we call

‘Tall Poppy Syndrome’ – the cool reception that would greet the American-style earnestness I had only recently learned.

An outsider is also subject to competing pressures. In addition to constantly learning what new peer groups expected, I had to weigh up the expectations of my family, itself dividing into different cultures with different expectations, reading my behaviour in different ways.

Cultural outsiders tend to cope by going in one of two directions. Either they throw themselves into beating the indigenous at their own game, rapidly mastering new techniques of status and identity, or they try to take advantage of their outside perspective to escape the game altogether. After a series of embarrassing failures with the first strategy, I was left with the second. I believe the philosophers that I present here went the same way. The Zhuangzi, written around 476–221 BCE in what is now China, is full of favourable presentations of dropouts, criminals, beggars and outcasts, suggesting that its author(s) were outsiders by choice. Spinoza was doubly displaced: the child of Jewish migrants who fled to the Dutch Republic, who was then expelled from his own community as a young adult.21 Girard was a quintessential outsider: a French expatriate in the United States and a practising Catholic among a milieu of secular postmodernist intellectuals. He once said: ‘All my life, I’ve never been able to work except outside institutions and so, subconsciously, I worked against them.’22

Perhaps this is only a self-serving narrative, but I believe that outsiders have a unique perspective on the question of identity. Those born native to a culture seem to me to fall easily into the illusion that their drive to cultivate a certain identity arises from deep within themselves – that their ambitions and aspirations are the feeling of their true self bubbling up from the individual soul and demanding expression in the world. From

Introduction: Identity Kills the outside, it is apparent how much these ambitions and aspirations are in fact imposed upon individuals by the prevailing culture, as Hundun’s face was drilled into him by the other emperors. The outsider can see how intensely people imitate each other and compete to express the same identities. The outsider can also see how identity-formation is driven by fear and implicit threats: we ‘find ourselves’ under duress from a crowd that demands to know who we are and will deal with us according to the answer. And the outsider can stand back and ask whether this whole process makes anyone happy.

It is hard to see how the pursuit of identity can lead to happiness. The inner self that we long to express is, in the first instance, modelled on an ideal found in our cultural environment. Whatever this identity might be – SUV-flaunting corporate lawyer, indigenous-art-buying diversity consultant, career politician at the top of the pyramid, or responsible citizen relentlessly educating those of feebler virtue – each is guaranteed to serve as an exemplar, and will possess the quality of exemplarity. Striving to be like our model, we will desire to become exemplary ourselves. This means seeking out admirers or disciples of our own, just as our model found a disciple in us. Unfortunately, others are not looking to become our emulators. On the contrary, they will want to retain their own hard-won identities and, propelled by the same dynamic, to attract emulators of their own. We end up in a sort of existential power struggle in which each wishes to be emulated and none wants to emulate. Everyone wants to be the influencer, nobody the influenced: and so the public sphere becomes a theatre with all actors and no audience, a fashion show with everyone on the catwalk, a university with lecturers and no students, an ashram with gurus and no disciples. Moreover, we work in a limited-attention economy. Public

admiration is a scarce resource because the attention span of the public is limited, as most people broadcast more than they receive. Different aspiring exemplars must compete for the approval of a highly inattentive crowd. Social interactions become a complex, competitive game of pride, envy and ambition, where the stake is survival – survival, again, meaning retention of identity. Influencing others becomes integral to its goal.

Not only does this lead to rivalry and conflict; it leads to frustration. What we wanted was our own identity. What we keep finding is somebody else’s, and maintaining it feels less like self-expression than pandering to the crowd. No wonder we kick so hard against those who threaten our identity. They take the blame for a failure whose real explanation lies in the fundamental inconsistency of our aim. They remind us of the embarrassing arbitrariness of what we take to be essential – of our ontological unoriginality, our essential emptiness. When they thump against us, we are ashamed to ring hollow.

All we can do to drown out this unwelcome reminder is drive ourselves harder into our aspiring identity: to be bigger and bolder in expressing it. That is exhausting and expensive. It costs us in time, effort, stress and material resources (status symbols are costly to produce). No wonder we live in such a busy, competitive, anxious world, straining against the limits of what an alien visitor might regard as enviously abundant natural resources and great ingenuity in enhancing them. No wonder millions of lives are destroyed in wars over empty abstractions like national honour. No wonder sensible institutions are torn down for the sake of a politician’s career aspirations or for one political tribe to prove a point to its recalcitrant rivals. No wonder everyone rails against the unchecked power of giant corporations while giving those same corporations unlimited

Introduction: Identity Kills access to their fragile self-esteem and nervous ambition, ready for conversion into endless purchases.

Most of all, we find ourselves unable to adapt – to each other, to the rhythms of nature, to the inevitability of change. Identities are formed in the past, but life drives us into the future. When our current ways of life prove unsustainable, you might think that we could just change them – after all, there are many worthwhile ways to live, and being forced to change is often a blessing in disguise. But if our current way of life has become part of who we think we are, then changing it means losing our being; it might as well be death.

If a superpower nation finds its global dominance challenged, you might think that it would welcome the break, letting others take the reins for a while. But if superpower status has become part of its national identity, then it will prefer war without end to a comfortable seat on the back bench of nations.23

When the economic tide turns against somebody on the Forbes list of the world’s richest people, you might think that they could drop out and retire to a life of luxurious leisure. Instead, they work harder, take greater risks, or increase the criminality of their activities to restore yield.

When we and our political rivals suddenly find ourselves in common difficulty, you might think that we could put aside our differences and find solidarity in a shared struggle. But then we would lose our tribal identity: better to both lose as opposing sides than both win and risk merging into the people we have defined ourselves by hating.

When an intelligent species finds that its current energy base is thoroughly unsuitable to its long-term needs, you might think it would quickly move to transform it. But human

individuals and communities have internalized current patterns of production and consumption into their own identities, making even small reforms appear as threats to their very being and large reforms politically impossible. Moreover, no group wants to make a sacrifice if there is even a chance that some rival group is getting a better deal: better a level playing field at the bottom of the ocean than any slight to our honour and status. Since perfect justice is impossible, let the heavens fall.

Thus, do we lock ourselves into unsustainable patterns, in hopeless denial of the fundamental instability of things, not because change is painful or difficult (after all, so is failing to change), but because our identity has made it logically impossible. We have become what we do, and so what we do cannot change, even when it must.

One symptom of the identity drive, therefore, is hyperactivity. We consume vast quantities of materials and energy trying to control events and each other – trying to make the world match the pattern consistent with our sense of self. Few philosophies enjoy less popularity in practice than what Daoist texts call wu wei 無為 – or non-action.24 Of course, there are many things to be done in the world. The poor must be lifted out of poverty, the sick must be treated, broken systems must be fixed, outdated ways of doing things must be reformed when circumstances change. But there is a great deal of activity that occurs only for the sake of extremification: gaining more wealth for the rich, more power for the powerful, more beauty for the beautiful, more popularity for the popular, more hegemony for the hegemonic, more status for the elite, more education for the already overeducated (here I am not innocent), more medals to pin onto chests already crowded. All this activity is driven by identity. People begin to achieve outstanding, glorious identities and then see others catching up. To retain their

Introduction: Identity Kills glorious status, an integral part of their being, they run to stay ahead, with the competitors hot on their heels.

Imagine if we could stop, even for a moment, trying to be anything. Could we then find new ways to act and live, consistent with a changing world? Could we raise our gaze from the inner easel on which we were so furiously painting our selfportrait and see the beautiful world around us, celebrating its capacity to defy all our categories, expectations and attempts at control? Could we learn to see each other, not as the backdrop to our own self-portrait but as subjects of a wonderful and multifarious tableau, of which we make up just one small but vital part? Could we then do the one thing that every creature that has ever endured in our world has done – every species that made it through an extinction-level event, every culture that survived a colonial invasion, every individual who came out the other side of grief or a life-changing trauma – could we learn to adapt?

The hardest thing I have experienced in my life so far is watching my father in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. His humour, wisdom and kindness were still there, but now they shone through clouds of confusion. My mother harnessed her linguistic gifts to sift grains of sense from his thought. The love was beautiful but heartbreaking.

To me, my father had always been defined by his bravery and intelligence. He always knew what to do, and he never let the situation get the better of him, no matter how hard things got. Wandering through the parks of London with him, listening to his strange rhapsody of blended past and future, of expertly identified trees alongside garbled fantasy-Latin, seeing the fear in his face as he realized what was happening to him, I worried that his core traits were, for the first time, under threat – from

an invisible, interior enemy. I was losing him, I missed him, and I could not imagine going on without him. What my mother was going through I could not fathom.

Alzheimer’s is a slow disease. Each time you adjust to one phase, it progresses to another. A friend told me I had to stop trying to bring my father back to my world and learn to enter his. That turned out to be the secret. My father was not vanishing; he was changing. He was continuing to teach me, even after losing the power of language. If he could learn to adapt to his strange new world, so could I. His personality dissolved, his appearance changed, but my love was the same. Nor did his love ever disappear; as I pushed him in his wheelchair and listened to his language breaking down from sentences to words to syllables, I felt it more than ever. He was becoming Hundun, and he was teaching me to become more like Hundun – letting go of the things I was exhausting myself trying to hold onto, the things by which I had defined both him and myself, and learning to find the joy in what was there.

This piece of wisdom shed new light on the philosophy I had been reading for years but not understanding. Nothing can stay the same. Trying to hold onto things the way they are is a losing game. But love remains, because love can flow along with the ways that things change. Love is as supple as the world, and the world’s transformations cannot erase it. Love is the opposite of identity and the secret to adaptation.

Adaptation means changing, and changing means not needing to be the same. Not needing to be the same means not having a definite, immovable identity. It means giving up on trying to remake the world in your image – giving up, indeed, on having any image at all. It is thoroughly inconsistent with egotism and ambition. The philosophy presented here holds that the world