UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Dial Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 2025

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Michael Joseph 2025 001

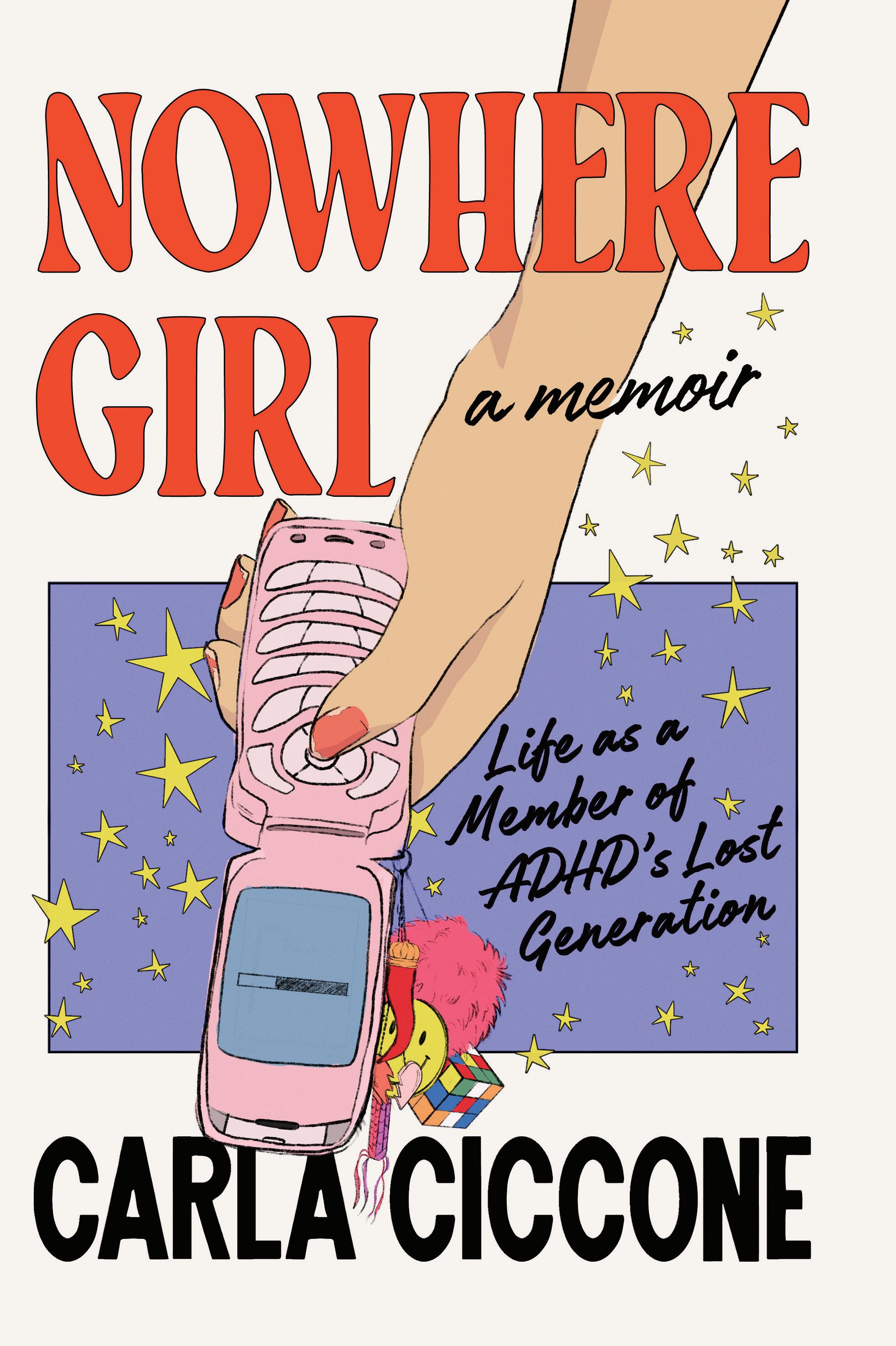

Copyright © Carla Ciccone, 2025

Lyrics on p. 89 from ‘Doll Parts’ by Hole; on p. 95 from ‘Gutless’ by Hole; on p. 237 from ‘Keep Me In Your Heart’ by Warren Zevon

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases names of people, places, dates, sequences and the detail of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Book design by Diane Hobbing

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HARDBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–64733–2

TRADE PAPERBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–64734–9

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is for the daydreamers, especially my bella stella, P.

They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.

— Edgar Allen Poe, “Eleonora”

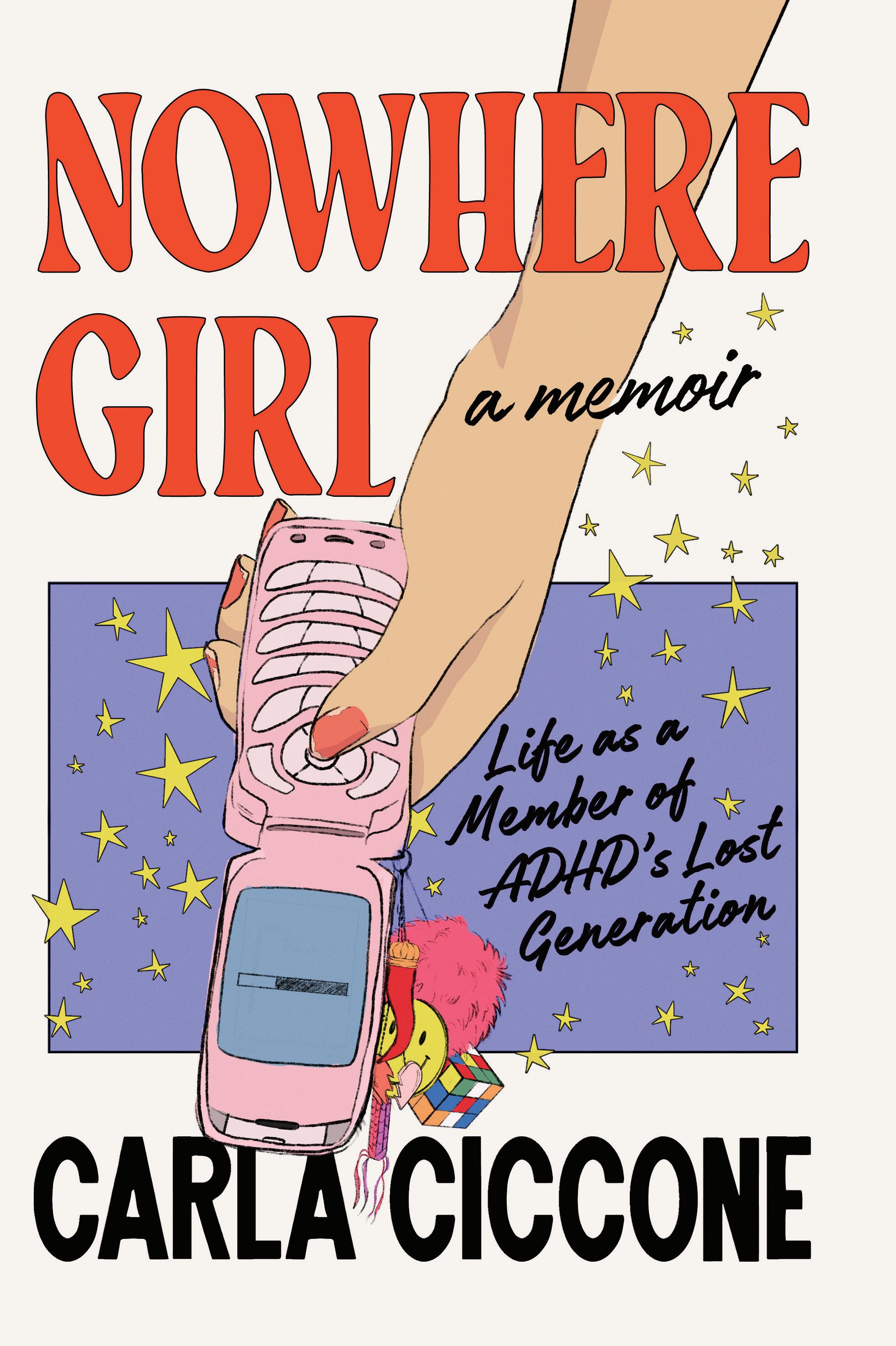

This book is about living with ADHD, a common disorder that’s often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed in girls and women. It’s about how undiagnosed ADHD wreaked havoc on my life. I hope my story is relatable, but it’s not my intent to speak for everyone with ADHD.

As with many areas of medical research, women and girls with ADHD were historically not studied. Nowhere Girls refers to the people assigned female at birth who were excluded from the field. The words women and girls appear throughout this book, but not all Nowhere Girls identify as women. The majority of the forty women and nonbinary people I surveyed as part of my research for this book were diagnosed in their mid-thirties to late forties. Like me, they were pre-internet nineties teens who watched their brothers get ADHD while they got Girl, Interrupted.

I’ve used the symbol of the Greek goddess Psyche Ψ throughout the book to indicate reading pauses. Most current use of the word psyche relates to the mind, but Psyche was the Greek goddess of the soul. The story goes that she was a beautiful human who fell in love with Eros, the god of love. Unfortunately, his mother, Aphrodite, didn’t approve, and forced Psyche to endure many harrowing and impossible trials to be with Eros. Even though I hear this story and think, girl, run, Psyche completed the tasks, which included shearing violent rams and going to Hades to bring back water from the River Styx. Afterward, she became the goddess of the soul and was allowed to marry Eros. Psyche is depicted as a woman with butterfly wings, and since butterfly wings are sometimes used as the symbol of ADHD, I thought it fitting that her trident help to represent the struggles and triumphs many neurodivergent people face. We may not all attempt impossible feats to appease a difficult mother-in-law, but many of us have traveled a long, lonely, and sometimes torturous road to live authentically.

The language of neurodiversity is exciting, necessary, and continually evolving. I’ve tried my best to keep this book up-todate with current neurodivergent-affirming language standards.

The names of many of my family members, friends, and foes were changed to protect their identities. While I’ve told my story honestly and tried my best to remember the past accurately, there might be details I didn’t get quite right, or left out, or forgot. But, as I say whenever I forget to pay my cellphone bill: It’s not my fault! I have a squirrel brain.

The way I spoke to myself in early motherhood was diabolical, but I’d been perfecting the art of motivational meanness for decades. It helped me get shit done, and it hid the war within me under a veneer of togetherness that I constantly fought to maintain.

Keep smiling, I said as we walked by the nurse’s station. A nurse asked how I was feeling. “Great!” I said. You stupid liar. Round and round I went, pushing my beautiful newborn through the cesarean recovery wing in her plastic hospital bassinet. I ignored the piercing pain emanating from the diagonal wound in my low belly as my arms shook from the Percocets and I clung to the bassinet like a life raft. I marveled at my baby’s tiny brand-newness and resolved to keep my shit together for her. I should have been in bed resting, but instead, to prove I was a good mother, I pushed through my body’s pleas to slow

down. This was my job now. I didn’t feel worthy of the title, but no one else could know that, so I faked it.

Eight hours prior, my baby was stuck in my pelvis and cut out of my stomach during an emergency C-section. Nurses handed her to me, and I held her on my chest and kissed her perfect bald head, and about an hour after we were brought to our room, I told my partner to go home. What was the point of Luke sleeping on the floor of a tiny, sweltering hospital room with paper-thin walls?

“Don’t worry. I can handle this,” I told him. I was very high. I attempted to breastfeed my baby, and a kind nurse placed her in the bassinet and told me to get some sleep. Seconds, or minutes, or maybe an hour later, a different nurse shook my bone-weary body awake, threw off my blankets, handed me my baby, and told me to feed her. I didn’t want to cry, so I swallowed my tears along with the handful of painkillers and stool softeners she gave me. She also administered strict orders to pee, poop, and walk around as soon as possible, then she vanished. No one mentioned what was normal or what a body that was recently cut in half should feel like, so I did what I was told and forced my body to perform.

I shuffled by the rooms of my fellow C-sectioners and heard them moaning in their beds. Didn’t they hear the nurses? We have to pee and walk around. Pretending to be fine was a part of me, and denying my pain was nothing new. My bodily experience came secondary to the front I’d been keeping up for my whole life.

My miraculous cesarean recovery performance was so convincing, the hospital released me less than forty-eight hours

after giving birth, but my facade cracked when it hit me that I was in charge now. The nurse who brought over my discharge paperwork was met with the desperate face of a person who was not ready to be on her own and could no longer fake it when met with reality.

“I don’t feel ready to leave,” I cried, hunched over in pain, straining to comprehend the enormity of the task ahead of me.

“It’ll be okay,” she said sympathetically before adding: “We do need your bed for another patient.”

She walked out of the room, and I looked in the mirror. Get it together, bitch. You’re a mom now.

Despite the self-hate that emerged as a survival mechanism in early motherhood, having a baby pushed me closer to the person I’d always wanted to be. Prepping for it while pregnant was the catalyst to getting and staying sober after two decades of on-and-off substance use.

Motherhood also made me determined to confront generational demons and raise my daughter differently than I was raised, to give her the gentleness, encouragement, and ease I wasn’t afforded. It’s a nice idea many new parents have, but one that I was comically unqualified to put into practice. It turns out, if you truly want to be kind and gentle with your kids, you must first learn how to be kind and gentle with yourself. I had to learn how, and I didn’t know where to start, so when my daughter was two, I began therapy.

After a month of weekly sessions, my therapist urged me

to get assessed for ADHD. She suspected I had it, but my symptoms—trouble concentrating, feeling too damaged to fix, hypervigilance—also matched the profile for C-PTSD.*

At the mention of ADHD, my mind went back to the nineties classrooms I longed to escape from, full of tween boys hawking spitballs past motivational posters with kittens on them. Those kids definitely had “ADD.” I was just a daydreamer back then, a hair-twirler who frequently forgot her textbooks at home and doodled endlessly on notebooks and desks. Surely, I had nothing in common with the hyperactive boys of my youth who ate glue for fun.

ADHD’s a disorder, like OCD,† that has become a part of our cultural lexicon, and one used as a personal punchline by many women trained to excuse themselves and apologize for living. When I heard I might have it, my first response was in line with this conditioning: “Well, doesn’t everyone have a little ADHD?”

No, it turns out.

ADHD is a brain disorder that affects approximately 2 to 4 percent of adults worldwide (although if we account for the undiagnosed, that number is likely much higher).1

Once I became aware of adult ADHD, it was everywhere. The online tracking gods had my number, and social media fed me an endless supply of on-theme memes and TikTok videos. I could relate to the feelings of confusion, overwhelm, and shame people were depicting, but I still wasn’t convinced I could have it. I viewed ADHD as an excuse for being scattered and disorganized, and I wasn’t ready to excuse myself. Not yet.

* Complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

† Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

My assessment with a psychiatrist was long and taxing, detailing the inner workings of my mind and my experience of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The report came back a week later, and I was officially diagnosed with ADHD at thirty-nine years old.

This happened one year into the pandemic, and I’m far from the only one who made this discovery about herself at that time. Memberships in the Attention Deficit Disorder Association (ADDA), an international nonprofit that serves adults with ADHD, nearly doubled between 2019 and 2021.* And worldwide Google searches for “ADHD women” started climbing in April 2020 and haven’t come back down since.2

At the time, I didn’t even know what ADHD stood for, or at least what the H meant. It’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; however, most experts agree that the name is confusing. It might be better titled “attention malfunction disorder” or “restless mind syndrome” or “I’m definitely going to interrupt you but it’s not my fault.”

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition, or brain disorder. It impacts the prefrontal cortex, and in case you didn’t pay attention in biology class either, that’s the organization and attention center of the brain. It also affects the limbic system, which helps control emotions, memories, behavioral responses, and autonomic nervous system functions.

A 2006 study found that the cerebellum, the brain’s mover, shaker, and decision-maker, is the most “robustly deviant” region of ADHD brains.†3 The cerebellum, or “little brain” in

* According to data from the association’s president.

† Naughty!

Latin, is responsible for regulating our movements, controlling balance, and coordinating gait and muscle activity.4 Learning this gave me much relief because balance eludes me. I had BandAids on my knees for my entire childhood. I split my lip open twirling into an old wooden TV. I even lost my balance while dancing on a speaker in the club as a teenager and fell onto the concrete floor, knees first (they’ve never been the same).

The symptoms of ADHD usually first show up in early childhood and become more obvious as kids enter grade school. There is no biological test for it, and the diagnostic criteria, as we will learn, suffer from the pathological parameters of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5—the book many mental health professionals consult to identify the disorder. The criteria it lists are largely geared toward the hyperactive, or typically young White male presentation. Some of the symptoms listed are:

- squirms when seated,

- fidgets,

- displays poor listening skills,

- sidetracked by external or unimportant stimuli,

- marked restlessness that is difficult to control,

- overly talkative,

- diminished attention span,

- interrupts, and

- impulsively blurts out answers before question is completed (my fave).

People aged seventeen and over need to have at least five symptoms for a diagnosis, while those under seventeen need six

My Head 9 or more.5 These criteria are helpful, but they also leave out a lot of the nuance that defines ADHD in girls and women.

Learning I have a neurological disorder that emerges in childhood baffled me at first. I showed many of the DSM symptoms, so how did no one notice it for over three decades?

I started looking back with suspicion, then anger, at the many signs that my parents, teachers, doctors, and caretakers not only missed but also turned into personality flaws: “She’s lazy,” “She has her head in the clouds,” “She gives up too easily,” “She’s careless,” “She’s a klutz.” I dug into the research conducted on girls and women with ADHD with a sinking feeling in my stomach. In 2022, while chatting with UC Berkeley distinguished professor of psychology Stephen Hinshaw, a leading expert on the subject and one of the first researchers to study girls, so much of what felt off about these massive holes in ADHD research was confirmed for me. I asked Hinshaw what the field was like when he first started studying the disorder, and he told me that in the 1980s and ’90s, most people assumed girls just didn’t get ADHD. “The beat went on with that stereotype, no one did any research and girls kept getting ignored,” Hinshaw said. “I’m an objective scientist, but I had a hunch the field was full of shit.” (He was right.)

There are three main presentations of ADHD. The stereotypical type is hyperactive—the fidgety little boy who can’t sit still. Energy generally gets directed outward with this type. It can also calm down with age, as our bodies do.

A person with inattentive ADHD usually appears calmer but makes careless mistakes, becomes easily distracted, has a hard time with organization and following instructions, and loses and forgets things regularly. Although the word inattentive im-

plies a lack of attention, it’s a misnomer. People with inattentive ADHD can pay attention, and if something is of special interest to us, we display intense focus, but we lack the internal regulation required to make decisions about how and when to deploy our attention. Having this type makes it harder to focus when we’re bored and to process information, especially if it’s unstimulating. Girls commonly exhibit the inattentive type.

There’s also combined type ADHD, which features qualities of hyperactive and inattentive. The hyperactive elements can also get internalized with the inattentive and combined types, leading to internal restlessness and subtle fidgeting. I suspect this is what I was dealing with as a kid.

“I could argue the inattentive [type] is actually more severe in terms of impairment than hyperactive because you can still listen to what the teacher’s saying if you’re running around the room,” says Emma Climie, a child psychologist who runs a strengths-based clinic for kids with ADHD at the University of Calgary. “But if you’re staring out the window and you don’t even know what’s going on, that’s very different, right?”

Those with inattentive ADHD are normally diagnosed later into their school years, if at all, because their symptoms and the struggles they cause become more apparent in academic settings. Many appear high functioning and keep their torment to themselves. This type tends to get worse as we age, which is one clue as to why so many full-grown women are being diagnosed with ADHD in recent years.

Even after the definition of ADHD evolved to include inattention and impulsivity in the 1980s, the disorder was still centered on boys, so the very same symptoms displayed in girls were often attributed to anxiety, conduct problems, or depres-

sion, to name a few. These comorbidities tend to add up in undiagnosed women, with recent research putting the mean age of ADHD diagnosis at thirty-six to thirty-eight. Most of these women were eventually clocked for the disorder either because of the concurrent mental health challenges they experienced, or because they had a child diagnosed first.6

In 2022, I put out a call on social media to survey women diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood, and heard from forty of them. Some filled out a Google form I made full of invasive personal questions, others exchanged emails or texts with me, and a few I chatted with (and we’re besties now, obviously). They ranged in age from their early twenties to their fifties, but most of them fell into the thirty-four-to-fifty age range. They were honest, vulnerable, and beautifully generous with their stories. They were also grappling with the pain that comes from learning something essential much later than you should have.

Many of us were undiagnosed in childhood, only to see our issues compounded by the time we reached adulthood. We got used to being, and feeling, invisible.

Since an immense loneliness, born of feeling like an outsider in most school, work, and social situations, had defined so much of my life, it was baffling to consider myself one of many. The imposter syndrome that has followed me since childhood had another reason to torture me. I always thought I was a uniquely fucked-up fraud. Discovering that I was actually part of a big, chaotic sisterhood felt like being ushered into a secret group that I’d been searching for my entire life. It was cathartic, hearing from other people whose life experiences mirrored mine. I felt less alone in the world. I refer to us as ADHD’s lost generation because we were all overlooked and suffered for it in

similar ways. This made me want to create some kind of Island of Misfit Toys for us to just talk, heal, and validate one another. I don’t have those kinds of resources, so I wrote this book instead.

I decided to call us Nowhere Girls because we’re a group of women who have felt like we were running, without a destination, from our emotional demons for most of our lives; because finding out, or even considering, that there was something larger at play than simply being fuckups who couldn’t get our shit together is a process that often plunges us into grief and anger at the way we’ve been treated. At the way we treated ourselves.

Nowhere Girls are a cohort that science left out of studies and literature for decades, and the impact of this extends far beyond the pages of the papers we should’ve been included in. Too many women of this generation grew up missing a pretty essential piece of information about themselves, one that has likely touched every aspect of their lives.

What being undiagnosed, untreated, and ignored for most of our lives means for Nowhere Girls is incredibly complicated. A late diagnosis forces one to look back and filter the past through a different, hopefully kinder lens, but the process of reliving your entire life in order to change your mind about it is gnarly.

By the time I was a kid in the 1990s, little White boys with ADHD were everywhere, and the rest of us were nowhere. The reason for this is as simple as it is sad: the socioeconomic, gen-

der, and racial biases baked into medical science, historically a field of White men reluctant to look beyond their own reflections for answers. It makes the bias inherent in the ADHD field inescapable.

Research that does exist on girls and women with ADHD is not necessarily indicative of most of our experiences, because when girls were finally included in the 1990s, the ones with more typically male-presenting hyperactive symptoms were noticed and studied first.

Boys externalized their struggles; girls buried theirs. While I was biting my nails, twirling my hair, and staring through my teachers instead of listening to them, the boys with ADHD were chronically unseated, fidgeting, and usually willing to go to great lengths to break open the classroom tedium.

I didn’t struggle in school until seventh-grade math class came along, but I also stayed up late doing my homework, relied on my mom to help me when I forgot about school projects, was constantly bored or overwhelmed, and fought a losing battle inside my brain while trying to pay attention in class.

Many Nowhere Girls told me that they were branded as daydreamers or chatterboxes in school, but since we didn’t act out or fail our classes, teachers and doctors had no reason to suspect we had ADHD.

When they did alert our parents that something was wrong, as my seventh-grade math teacher did, it was usually done in a way that placed blame on us instead of considering issues beyond our control, reinforcing the myth that we were simply slacking off or unmotivated.

The ways ADHD presents in women might seem complicated, but let’s not get it twisted—the biggest reason girls didn’t

and don’t get diagnosed with ADHD as much as boys is because we were not considered in the research for many decades. You need only look at the rise in adult women being diagnosed with the disorder to see that there’s a major course correction currently under way, and it’s been a long time coming.

Becoming a part of this course correction and looking back at my own history has answered many questions I had about my brain and life experiences. But more important, it’s also quieted my most frequent question to myself, which for a long time was, What the hell is wrong with you?

The research is finally catching up for those of us left behind. Flawed as they might be, the studies from the past few decades prove that while a strong contingent of women with ADHD fall into the high-achieving, high-masking Type A category, a lot of us are also likely to have histories and lives that match our chaotic brains.

While interviewing Professor Hinshaw, I admitted that I was having a hard time thinking of my diagnosis as a reason, instead of an excuse, for my many mistakes.7 “You probably felt that somehow you deserve this because you’ve internalized a lot from the years of missed and untreated ADHD, and from trauma,” he said. I nodded, and started quietly crying over Zoom.

You don’t heal a lifetime of shame by getting a mental health diagnosis, but learning the impact of trauma, especially multiple traumas in childhood, on the progression of ADHD changed the way I saw my past. It made me realize I had chopped my life up into sealed silos. I’d grown convinced that the substance use, impulsive decisions, unhealthy relationships, and inability to hold down a job were all shameful personal defects and sepa-

rate manifestations of the worst parts of myself. That, as Hinshaw pointed out, I somehow deserved a hard life.

When I looked in the mirror with my daughter in the background, I had to learn a different story. I was so used to accepting discomfort as deserved that I didn’t know how to view myself as worthy of more. Learning about how childhood trauma and ADHD interact forced me to see myself as a small kid who was, and is, good. I started to see myself the way I see my daughter.

For me, the only way to understand the implications of relearning (and rewriting) my story was to start at the beginning.

Since ADHD carries a strong genetic component, it’s likely that I was born to parents and grandparents who were neurodivergent (and experienced their own trauma on account of it). Along with learning to forgive myself for my scattered brain and all it has wrought, I also had to forgive my family for not noticing I needed help, because our system was designed so that no one notices when little girls do.

I began the work of examining the narrative I’d been telling myself about my life. I also learned that many of my most reviled traits—my inability to put things away, to have enduring close relationships, to make and stick to a plan, to communicate without getting derailed by rejection, to organize my life— weren’t personal flaws, but symptoms of early traumas and undiagnosed ADHD.

Considering my own story with empathy and knowledge instead of shame and guilt gave me permission to begin to heal.

But even with self-forgiveness and therapy, it’s not easy attempting to change intergenerational cycles and the emotional programming they contribute to. It’s the emotional equivalent

of setting an alarm to get up in the middle of the night to catch a flight. You know you have to leave, and that a vacation awaits in the end, but getting out of your warm, cozy bed to step out into a cool night feels like the hardest thing you’ve ever had to do at that moment. And it’s like that every day, for a long time. Some of our healing, for me and the women I’ve encountered, happens when we find each other. The moment you tell someone you were diagnosed with ADHD as an adult, and they say, “Me too!” you know they know and they know you know. You don’t have to explain further (but we usually do).

We are everywhere. In my regular little life, most of my friend group has been diagnosed, or has started to identify as neurodivergent, since my own diagnosis. I also run into, on average, one woman per week who has been recently diagnosed with ADHD.

In the hallway of my daughter’s ballet class, I told the mom beside me about this book, and she got teary-eyed. “I just found out I have ADHD, and my daughters do too,” she said. At Pilates, which I used to go to once a week, a woman next to me told me she works out to keep her ADHD from getting out of control. I have conversations about ADHD with strangers at coffee shops, once while getting my legs lasered, and even while stricken with indecision at the ice cream shop. Everyone invited late to the ADHD party has felt a sense of relief to have a diagnosis to point to, but our emotions are in conflict. We are sad and frustrated about the time we’ve wasted on doubting and blaming ourselves for being different. A lot of us are angry, and we have every right to be, especially since many of us grew up with our anger denied and rejected. Owning that anger and learning to live with it is just as critical as our need for gentle-