Tigers Between Empires

TIGERS BETWEEN EMPIRES

The Journey to Save the Siberian Tiger from Extinction

JONATHAN C. SLAGHT

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the USA by Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2025

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Jonathan C. Slaght, 2025

Frontispiece, Siberian Tiger (2000) © John Banovich, 2025

Tiger illustration on title page and part-title pages © Meadow Kouffeld

Part-opening photographs © Jonathan Slaght Maps © Scott Waller

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–63345–8

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Anwyn

Having left Terney on December 27, 1939, I was on skis with a backpack and spent forty nights in the open air. I had to fast for six of those days, and in January the temperatures reached −48 degrees. But I successfully completed the main task that I set for myself—a tiger census in the reserve.

—LEV KAPLANOV,

1940

Contents

Maps xi

List of Key People and Tigers xvii

Prologue 3

Introduction 7

PART ONE: 1989–1993

1. The Green Fire 17

2. The Cold and Ice of Terney 32

3. A Moose Biologist in Tiger Country 45

4. Dale and Viktor Track a Tiger 57

5. A Tigress Named Olga 70

6. Thinking Like a Tiger 85

7. In a Forest of Ancient Pines 99

8. Dale, Igor, and the Tunsha Bear 108

9. Olga and Her Mother by the Sea 124

10. Maurice Gets His Tiger 134

11. Natasha of the Ivanga 144

12. The Slow Burn of a Capture Season 154

13. Mariya Ivanovna and Her Cubs 165

14. Tiny Tracks in the Snow 176

15. In Russia, Tigers Fly Coach 186

PART TWO: 1994– 2005

16. The Kolumbe Man- Eater 197

17. Olga Versus the Metal Kite 214

18. New Arrivals from Wyoming 227

19. Katya the Fearless 241

20. Murder, Snakes, and the Meare Heath Bow 254

21. Counting All the Tigers in the East 264

22. Hope for the Tigers of Dongbei 273

23. A Secret Known Only to the Forest 282

24. Olga, the Oldest Tiger in the World 292

PART THREE: 2010– 2024

25. Cracks in Collaboration 305

26. The Horse Hunter of Orlovka 318

27. The Tragedy of Galina 333

28. Kristina and the Boar Hunter 349

29. The Orphan from Changbai 365

30. Zolushka in Captivity 376

31. A Strange Convoy to Birobidzhan 390

32. The Last Capture 404

33. Tiger Conservation Across Borders 414

Author’s Note 427

A Note on the Siberian Tiger Project from Dale Miquelle 431

Acknowledgments 437 Notes 439 Index 467

MAPS

List of Key People and Tigers

Listed chronologically, by date of affi liation with the Siberian Tiger Project

Russians

DMITRIY (DIMA) PIKUNOV: Founding member of the Siberian Tiger Project. Senior scientist, Russian Academy of Sciences’ Pacific Institute of Geography in Vladivostok. Seasoned Amur tiger and Amur leopard biologist; one of the leads of the 1995 and 2005 All-Russia Tiger Surveys.

IGOR NIKOLAYEV: Founding member of the Siberian Tiger Project. Senior scientist, Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Biology and Soil Sciences in Vladivostok. One of the most experienced, knowledgeable, and influential Amur tiger biologists of the twentieth century.

YEVGENIY (ZHENYA) SMIRNOV: Lead field representative for the Siberian Tiger Project on the Russian side. Active with the project until 2006. Scientist at the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve in Terney.

NIKOLAY (KOLYA) RYBIN: Terney-based field assistant for the Siberian Tiger Project 1992–2016. One of the most experienced tiger capture specialists in the world. In 2016 began working for the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve. Older brother of Sasha.

ALEKSANDR (SASHA) RYBIN: Worked in Terney as a field assistant for the Siberian Tiger Project 1997–2006. Moved to Vladivostok to become manager of Amur leopard project. Worked with brother Kolya on multiple tiger confl ict situations across the Russian Far East. Has led multiple trainings in Russia and China on Amur tiger captures and human-tiger confl ict mitigation.

VLADIMIR (VOLODYA) MELNIKOV: Terney-based field assistant for the Siberian Tiger Project from 1997 until retirement in 2023. Involved in multiple captures of tigers and bears. Worked with Kolya and Ivan to address human-tiger confl icts.

IVAN SERYODKIN: Managed the Siberian Tiger Project from the Russian side 2010–2018. Senior scientist, Russian Academy of Sciences’ Pacific Institute of Geography in Vladivostok. Received his PhD studying brown bears in the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve with support of the Siberian Tiger Project.

Americans

MAURICE HORNOCKER : Conceived the Siberian Tiger Project. One of the most influential and respected carnivore biologists in North America. Experience studying cougars, jaguars, leopards, and tigers, with early tutelage under John Craighead in Yellowstone National Park.

HOWARD QUIGLEY: Oversaw the Siberian Tiger Project remotely 1992–2006. Integral to the establishment of the Siberian Tiger Project and led capture of Olga, the fi rst tiger collared for the project. Wildlife biologist and president of the Hor-

nocker Wildlife Institute, later Global Carnivore Program director at Wildlife Conservation Society, and conservation science executive director for Panthera.

KATHY QUIGLEY: Founding member of the Siberian Tiger Project. Traveled to Primorye periodically 1992–2006. Wildlife veterinarian. Trained Russian and American field biologists in basic veterinary care of tigers during capture process.

DALE MIQUELLE : Lead field representative for the entirety of Siberian Tiger Project on the American side. Based in Terney, Russia, 1992–2022. Wildlife biologist. Director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Russia Program until 2016; WCS Global Tiger Program coordinator until retirement in 2024. Author and coauthor of over 185 scientific publications about Amur tigers and leopards.

BART SCHLEYER : Worked for the Siberian Tiger Project 1992–2004. Wildlife biologist, experienced in large carnivore capture, immobilization, and tracking. Helped develop tiger capture methods in Russia replicated worldwide.

JOHN GOODRICH: Managed the Siberian Tiger Project for the American side 1995–2010. Wildlife biologist. As of 2024 is chief scientist at Panthera, where he has worked since 2012.

LINDA KERLEY: Worked for the Siberian Tiger Project 1995–1999. Wildlife biologist. Continued to live in Russia studying tigers until 2022, working for the Zoological Society of London 2007–2020. Used dogs to track tigers and leopards.

Tigers of the Sikhote-Alin

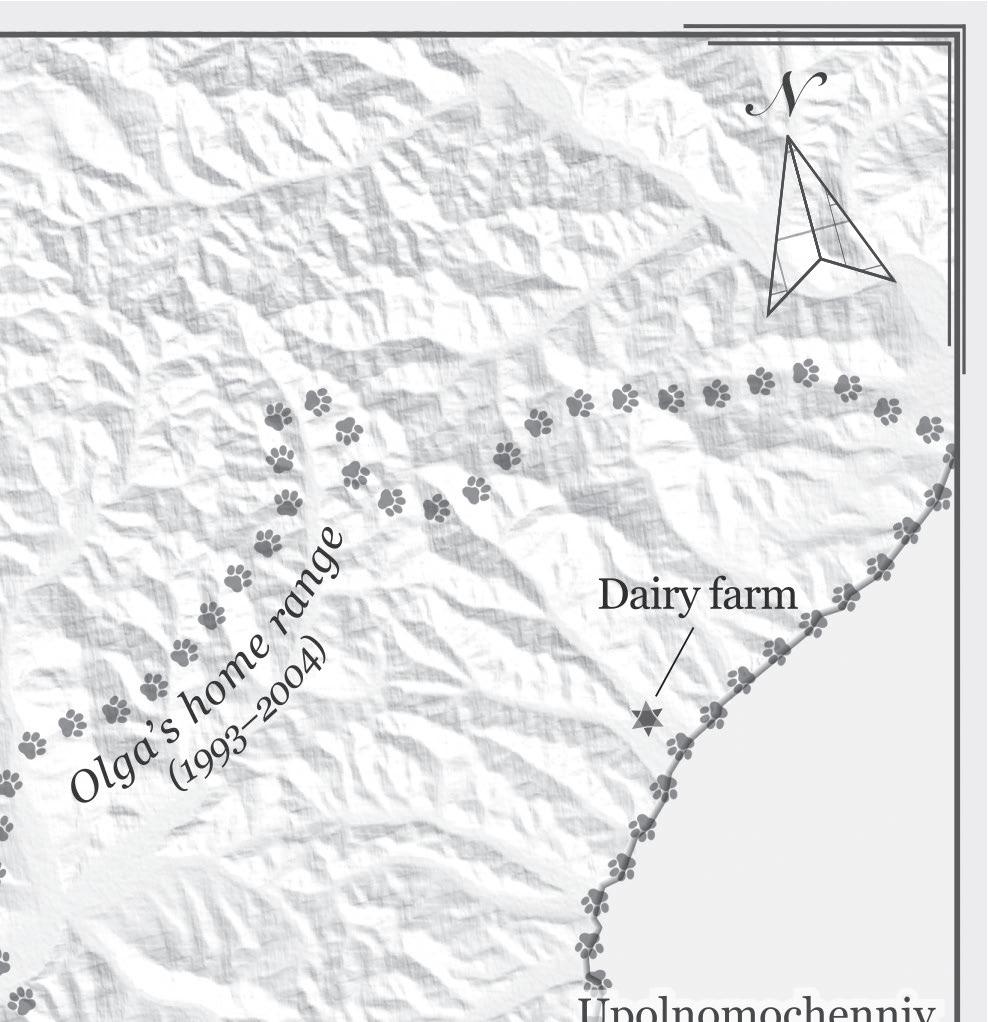

OLGA : PT01. First capture: Yaponskoye Lake, February 11, 1992. One-year-old cub, 74 kg (165 lbs.). Monitored continuously for thirteen years, longer than any tiger anywhere in the world. Captured a total of six times. Gave birth to six litters. Died in 2005.

LENA : PT02. First capture: Khanov Creek, June 22, 1992. Adult, 113 kg (252 lbs.). Birthed at least one litter. Resident female of the Blagodatnoe area. Died in 1992.

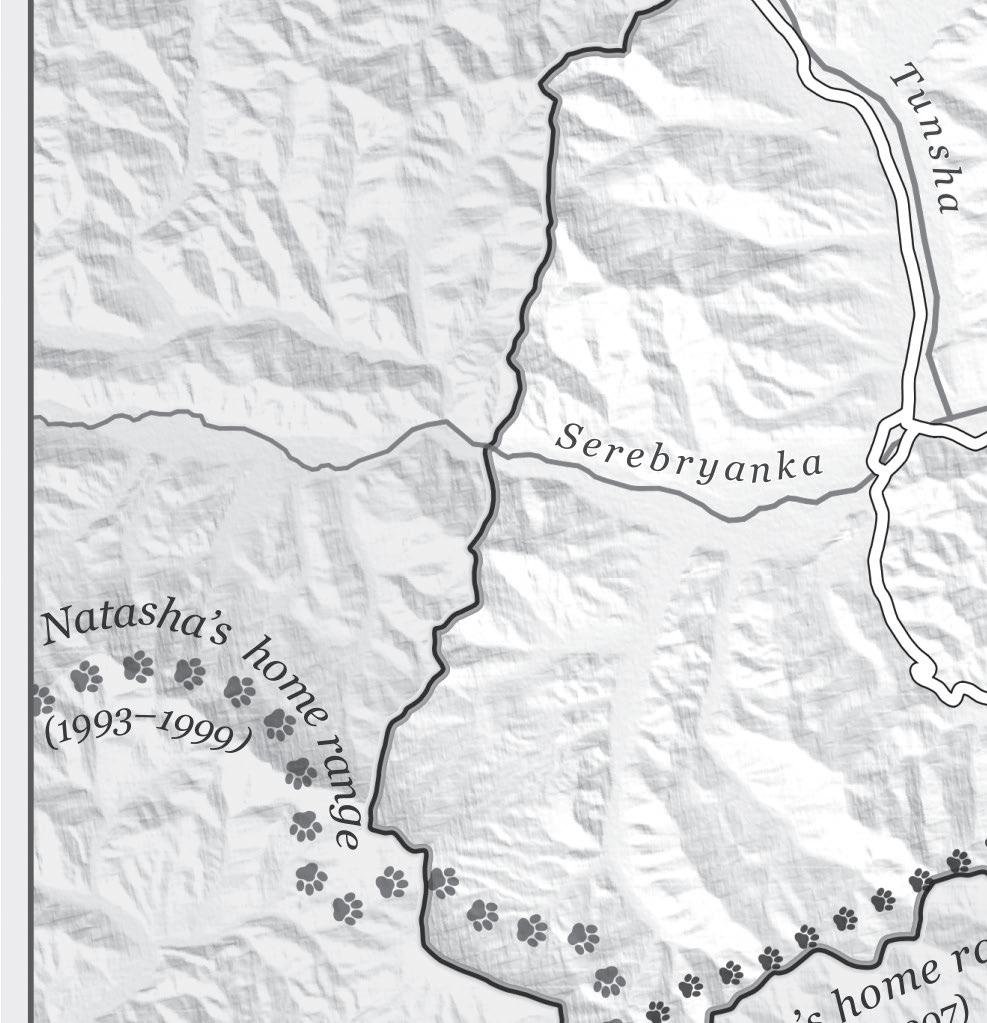

NATASHA : PT03. First capture: Ivanga River, October 17, 1992. Adult, 101 kg (225 lbs.). Captured a total of four times. Raised three litters while collared. Died in 1999.

MARIYA IVANOVNA : PT04. First capture: Tunsha River, November 11, 1992. Adult, 128 kg (285 lbs.). Mother of Kolya. Captured a total of three times. Raised three litters. Died in 1997.

KOLYA : PT06. First capture: Tunsha River, November 11, 1992. Son of Mariya Ivanovna. Predispersal young adult, about 90–100 kg (200–220 lbs.). Disappeared in 1995.

KATYA : PT15. First capture: Khanov Creek, October 29, 1993. Adult, 104 kg (230 lbs.). Resident female of the Blagodatnoe area. Birthed three litters. Disappeared in 1998.

ZHENYA : PT16. First capture: Kuruma, November 10, 1993. Adult, 173 kg (385 lbs.). Resident male between Terney and Plastun; mated with Katya in August 1995. Died in 1999.

LIDIYA : PT35. First capture: Kunaleyka River, October 21, 1999. Six-year-old adult, 113 kg (250 lbs.). Raised three litters. Died in 2006. Mother of Galina (PT56).

GALINA : PT56. First capture: Khanov Creek, October 24, 2002. Cub, 99 kg (220 lbs.). Resident female of the Blagodatnoe area after her mother, Lidiya, died. Captured a total of three times. Birthed three litters. Died in 2010.

ROMA : PT57. First capture: Kunaleyka River, November 7, 2002. Cub, 61 kg (135 lbs.). Slipped his collar in 2003; fate unknown.

IVAN: PT90. First capture: Tunsha River, October 29, 2009. Tenyear-old adult, 190 kg (419 lbs.) estimated weight. Mated with Galina. Died in 2010.

KRISTINA : PT99. First capture: village of Orlovka, Primorye, February 18, 2010. Adult, 120 kg (265 lbs.) estimated weight. Confl ict tiger that survived a poaching attempt. Collar stopped functioning in 2011; fate unknown.

VARVARA : PT114. First capture: Kunaleyka River, October 21, 2011. Two- or three-year-old adult, 110 kg (243 lbs.) estimated weight. Last radio-collared tiger in the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve. Last located in 2014. Fate unknown, but poaching suspected.

SEVERINA : UNCOLLARED. Based on camera trap images, an adult who became the resident female of the Blagodatnoe area in early 2022. As of 2024 has given birth to two litters.

Tigers of the Pri-Amur

ZOLUSHKA : Found near village of Krounovka, southwest Primorye, February 25, 2012. Five-month-old cub, 25 kg (55 lbs.). First tiger raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility. First tiger released into the Pri-Amur region. Collared and released in Bastak Reserve on May 9, 2013.

BORYA : Found in Yakovlevsky County, Primorye, December 2, 2012. Orphaned five- or six-month-old cub. Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild May 22, 2014. Brother of Kuzya. First encountered Svetlaya’s trail in 2015; met and later mated with her in 2016. Fate unknown.

ILIONA : Found in Svetlogorsk County, Primorye, March 2013. Orphaned nine- or ten-month-old cub, 60 kg (132 lbs.). Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild May 22, 2014. Sister of Svetlaya. As of 2024 still living in and around the Khingansky Nature Reserve.

KUZYA : Found in Yakovlevsky County, Primorye, December 2, 2012. Orphaned five- or six-month-old cub. Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild May 22,

2014. Brother of Borya. Crossed the border to China. As of 2021 was in the Taipinggou Nature Reserve in Heilongjiang Province, China.

SVETLAYA : Found in Svetlogorsk County, Primorye, February 2013. Orphaned eleven-month-old cub, 82 kg (181 lbs.). Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild June 5, 2014. Sister of Iliona. As of 2024 believed still alive.

USTIN: Found in Kavalerovo County, Primorye, February 14, 2013. Orphaned five- or six-month-old cub. Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild June 5, 2014. Recaptured in December 2014 after coming too close to human settlements. As of 2024, living in the Rostov Zoo.

LAZOVKA : Found near the village of Lazo in 2018. Orphaned four- to six-month-old cub. Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the wild in spring 2018. Fate unknown.

PHILIPPA : Found in Khasansky County, Primorye, in 2017. Orphaned four- to six-month-old cub. Raised at Alekseyevka rehabilitation facility, released into the Jewish Autonomous Region in spring 2018. As of 2024 believed still alive.

Tigers Between Empires

Prologue

PERCHED ATOP a coastal cliff, a tigress named Lidiya reclined, illuminated by the sun rising from the sea. She lay as a house cat might in a bay window, content and at ease. The colors of her pelage—cuts of black and washes of orange against a background of white—allowed this predator to all but disappear amid the complexity of the forest floor, hidden by the uneven terrain and obscured by shadows in the spindly oak forest.

Lidiya, the name given to her by staff of the Siberian Tiger Project, was the thirty-fi fth Amur tiger captured and released by this Russian-American research team. She was already an adult when caught in October 1999; at an estimated six years old then, she was in her prime for a species whose wild females might live to be fi fteen. That day on the cliff in the spring of 2002, she wore a tan collar, made from a leather-like material the width of a belt, which held a radio transmitter about the size of a dinner roll. The device emitted a silent VHF signal: a constant, monotone thwacking sound that researchers could hear with a

special receiver. This is how they studied Lidiya’s movements from afar. And as she sat lethargically, scanning her surroundings, two biologists were peering down on her from the sky, in a biplane, circling like an eagle riding a coastal updraft. If the tigress heard the drone of the airplane’s motor overhead, she gave no indication.

Over the seven years that the Siberian Tiger Project tracked Lidiya, from 1999 to 2006, she raised three litters and patrolled a territory that included about twenty kilometers of rugged coastline and stretched west another fi fteen, climbing into the forested slopes of the Sikhote-Alin Mountains. Her home range intersected with that of Volodya, the eight-year-old resident male, who wore a collar as well. His territory was three times larger than hers and overlapped with that of several females.

Lidiya looked so perfect that morning in 2002, basking in the sun high above the rocks wet from sea spray, that it would be natural to conclude that tigers had always been part of the landscape. But for decades, they hadn’t.

Predators once secure at the top of the food chain, Amur tigers had roamed unchallenged across nearly three million square kilometers of northeast Asia for thousands of years. Then, following seventy years of hunting and habitat loss, tigers almost went extinct in Russia. By 1916, the coast that Lidiya surveyed in 2002 had lost its tigers; survivors had retreated inland, where humans were scarce. Only in recent history—sometime in the late 1960s, following decades of conservation efforts—did tigers return to this edge of the sea.

The scientists in the biplane radioed Lidiya’s location to colleagues on the ground. A team would hike to this cliff in a day or two, after the tigress had moved on, to investigate what she’d done there. Perhaps they’d fi nd the remains of a kill, or evidence that she had consorted with Volodya, or nothing at all—maybe

she’d just been admiring the view. Such information would add to their body of knowledge about tiger ecology and inform management recommendations. The biplane’s wings dipped west, drawing it toward the mountains in search of more collared tigers, leaving Lidiya alone to gaze out over the water.

Introduction

WHEN A FRIEND ASKED Dale Miquelle if he wanted to go to the Soviet Union to catch tigers and track them, he thought the idea sounded insane. It was also exactly what he was looking for. It was 1990 and Dale was thirty-five years old; he had a stocky build and a face dominated by a Tom Selleck– style mustache growing thick along his upper lip. His laugh was like a roar, an unexpected eruption of sound that surprised and infected those around him, and his eyes were like those of a bear: sharp, penetrating, and curious. He was a New Englander living in northern Virginia, bored with his job at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, where he worked as an instructor for visiting scholars. He was trained as a field biologist and had professional experience in exotic places like Isle Royale in Lake Superior, Denali National Park in Alaska, and Chitwan National Park in Nepal. He’d been in the Washington, D.C., area for nearly two years and saw few opportunities for career advancement. Dale had never thought about Amur tigers, but he was eager to get back to the wilds, where he

could make a more immediate difference in conservation than he could in the classroom. Amur tigers might be the answer.

Dale was in regular contact with Howard Quigley, his friend from graduate-school days at the University of Idaho. For more than a year, Howard had been telling Dale about a research project that he and his mentor, the renowned cougar biologist Maurice Hornocker, had been trying to jump-start with Soviet colleagues in eastern Russia to study tigers. The plan was to combine Russian strengths of fieldwork savvy and knowledge of tigers with American expertise of capture and tracking. Together they would design a project, build stakeholder constituencies in the Soviet Union and in the United States, raise funds, and study tigers.

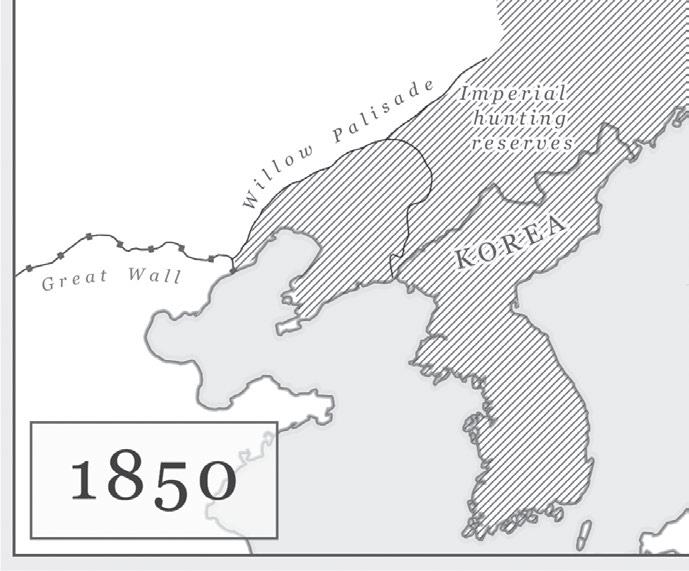

At their population peak before the 1850s, perhaps three thousand Amur tigers occupied a huge swath of northeast Asia centered on the Amur River basin and spilling outward, with some individuals roaming as far east as Lake Baikal, in the middle of Russia, and south to fi ll the Korean Peninsula. The Amur tiger’s fortunes changed for the worse in the second half of the nineteenth century, when two accords were signed between Russia and China, fi rst the Treaty of Aigun in 1858 and then the Convention of Peking in 1860. These agreements were unequal— Russia gained everything and China nothing—and wedged a political border in the center of the Amur tiger’s range. Everything north of the Amur River and east of the Ussuri River became Russia, including what are today Primorye Province, the Jewish Autonomous Region, some of Khabarovskiy Province, and most of Amur Province.

In the immediate aftermath of the treaties, both the Chinese and Russian empires poured settlers into the Amur region, the Russians eager to consolidate gains on their side and the Chinese anxious to stave off any further territorial losses on theirs.

Colonists to the new Russian lands, many of them from Ukraine, brought with them the then-predominant Western attitude of predator eradication and big game hunting. As the ecologist Yevgeniy Matyushkin noted in 1998, “For them it was natural to view the tiger and other large predators through their gunsights.” The Europeans hunted the cats with gusto, and as waves of immigration swelled, up to 150 of them were killed annually in the decades leading to the twentieth century. By 1898, only an estimated eight hundred Amur tigers remained in Russia. Within four decades the tiger population had fallen to no more than thirty—and maybe only twenty, a 96 percent decline. Surviving tigers retreated to isolated, roadless pockets of habitat deep in the Sikhote-Alin Mountains of Primorye, out of reach for all but the most persistent hunters.

Thankfully, a series of strong conservation measures driven by dedicated Soviet scientists prevented the accidental extinction of tigers from Russia in the twentieth century. In the 1930s, newly protected areas gave tigers safe spaces to raise their young. Starting in the 1940s, laws prohibited sport hunting of adult tigers, then later banned the capture of cubs; such legislation allowed tigers to survive long enough to breed. Slowly, over the second half of the twentieth century, tiger populations in Russia began to recover. An estimated 66 tigers were in Russia in 1958, 130 by the late 1960s, and 240 to 250 in the mid-1980s.

On the Chinese side of the Amur River, tiger populations showed the opposite trajectory: a constant decline over the twentieth century. The cats were hampered by human settlement, land conversion to agriculture, and intensive natural resource use. While there had been around two thousand Amur tigers in China just before the turn of the century, by the 1930s there were only five hundred. Natural resource exploitation accelerated in the early 1930s after the Japanese invasion of northeast

China and subsequent creation of the Manchukuo puppet state, which controlled northeast China until 1945. Following the formation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, pest eradication campaigns under the government of Mao Zedong, driven by the belief that tigers were impediments to Chinese economic development like mosquitoes and rats, depressed the tiger population even further. By the mid-1950s, perhaps two hundred individual Amur tigers remained in China; by the 1980s there were no more than thirty.

It wasn’t just the Amur tigers of Russia and China that were under threat. The twentieth century had, in no uncertain terms, been catastrophic for all tiger subspecies. In 1900 there were thought to be a hundred thousand tigers in the entire world— from Russia through China and Central Asia as far west as Turkey, and as far south as Bali in Indonesia. Three of the nine tiger subspecies—the Caspian, the Bali, and the Javan—went extinct in the twentieth century. A fourth subspecies, the South China tiger, was extinct in the wild as of 2001 and is preserved only by captive populations. Tigers today occupy just 7 percent of the lands they did a hundred years ago. Forest loss due to human development, predator eradication campaigns, and hunting for sport and profit have whittled tigers down to fewer than five thousand.

Just about every component of a tiger, even its urine and scat, is valued across Asia. Products like tiger wine, in which bones are soaked in alcohol, are a status symbol. People wear tiger skins as coats in Tibet and use them to decorate offices in Indonesia, and various concoctions of bone or tissue or even whiskers are said to treat everything from ulcers to toothaches. Purveyors of tiger bits regularly update the complement of maladies that tigers address: in 2020 their parts were touted for effectiveness against COVID-19 infection.

By 2022, the Bengal tigers of India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan were the most numerous tiger subspecies; more than 3,000 still live in this region, though they are relegated to small islands of intact habitat surrounded by oceans of humanity. The next most populous subspecies is the Amur tiger of Russia and China, with about 450 in the wild. About 400 Sumatran tigers remain in Indonesia. There are fewer than 200 Indochinese tigers in Thailand and Myanmar, and about 100 Malayan tigers on the Malaysian Peninsula. Since the turn of the twenty-fi rst century, tigers have disappeared from Vietnam (in 2002), Cambodia (in 2007), and Laos (in 2013).

The Amur is the only tiger subspecies that showed a positive population trend in the twentieth century. Unfortunately, when the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, tigers were once again being killed in large numbers, perhaps sixty per year, as the strong laws and habitat protections that facilitated population recovery under Soviet rule began to unravel. With unstable national and local economies, as well as weakened international borders, their carcasses were dragged from the forest, disarticulated, then secreted to China in suitcases at border crossings or smuggled on boats destined for South Korea, hidden among logs or tucked in shipping containers.

WHEN HOWARD QUIGLEY FIRST MENTIONED the Siberian Tiger Project to Dale Miquelle, he was simply discussing the details of his life with a friend. But throughout 1991 he started to see Dale as a possible collaborator. The project needed a field manager, someone to live in Russia full-time to lead the American side of the team. Howard thought that Dale, given his proven ability to work in remote areas under difficult circumstances, might be that person. Howard’s stories fi lled Dale with a sense of wonder

about the Russian province of Primorye, the place Amur tigers lived. Howard argued that there was true purpose to the work: they would be collecting new knowledge about an imperiled species to help save it. By the time Maurice Hornocker officially offered him the job, Dale needed no more convincing.

In January 1992, a contingent of American conservationists—Dale, along with Maurice, Howard, and a wildlife veterinarian named Kathy—arrived in Primorye to meet their Russian counterparts. The Americans were excited to get the science started but were alarmed to fi nd a society in chaos: the Soviet Union had collapsed only weeks before. The Americans and their Russian collaborators watched as a catastrophe bloomed in Primorye’s forests, documenting in real time how, with local people desperate for income, poaching and unsustainable extraction of timber and other natural resources bludgeoned tiger populations. The research questions they initially sought to answer remained the same—how much space do tigers need, how much prey do they eat, and how do they die—but the potential value of their data morphed into something more urgent. To save both Amur tigers and the forests of Primorye, they needed to build a case for the government and the public, and convince them that conservation was necessary to prevent irrevocable loss of a unique natural system.

Despite this uncertain start, the Siberian Tiger Project evolved across three decades, becoming the longest-running tiger research project anywhere in the world. When success is measured by a single animal captured, or the discovery of a lone, tiger-killed boar carcass in the forest, the larger impact of such work can be difficult to contemplate. Their efforts may have seemed small at the time, but their ideas, research methods, and actions to protect both tigers and habitat grew to influence tiger conservation not just in Russia and China but across all of Asia, wherever the

species is found. These dedicated biologists collected information on tiger ecology, created wildlife management plans, and worked with partners in government to adopt policy in support of tiger population recovery. Without these timely and essential interventions, we might now be speaking of Amur tigers as wild things of the past—like the Bali, Caspian, Javan, and South China tigers. Ever since settlers, both Russian and Chinese, fi ltered into Amur tiger forests in the middle of the nineteenth century, the fate of these cats has been linked to human attitudes. Amur tigers have been caught in this strange space between two empires— skirting the human- drawn line superimposed over forest and mountain in northeast Asia. For 170 years, tiger numbers have fallen and risen on both sides of the border as feelings toward these creatures have evolved: they were something to be feared, then hunted, and fi nally protected. The Siberian Tiger Project and its allies were at the center of the Amur tiger conservation renaissance. The project became a model of how like-minded individuals focused on a shared vision of a future with tigers could work together and enact meaningful change. How the project began, and what it accomplished along the Sino-Russian frontier, is a remarkable tale of innovation, camaraderie, adventure, and, ultimately, inspiring success.

The Green Fire

AMUR TIGERS , popularly called Siberian tigers, are paradoxes of grace and violence. These lithe, elegant creatures regard their surroundings with the dispassionate air of royalty. They are also predators, evolved to slip unnoticed across the landscape; to insert themselves like puzzle pieces among rises, rocks, shadows, and trees; to position themselves as close as possible to a grazing deer or a resting boar before showing a burst of speed and force to incapacitate their target. Tigers rely on discretion for survival, which means that these cats of the north are almost impossible to see, much less study.

“Siberian tiger” is a misnomer: these mysterious cats do not live in Siberia; rather, they occupy and spill forth from the Amur River basin, one of the largest drainages in Asia. The Amur draws water from as far west as Mongolia and flows east to form the contemporary border between Russia and China before emptying into the Tartary Strait near the Sea of Okhotsk. Throughout most of the twentieth century, scientists largely investigated Amur tigers in the colder months of the year, when the creatures

left pugmarks, or tracks, in the snow. Researchers could follow these imprints to glean insights into tiger life and behavior, such as how large their territories were, or what kinds of prey they pursued. But the knowledge of where tigers went and what they did melted into the forest floor in spring. This left biologists with an incomplete understanding of tiger ecology. Information outside of winter was sporadic, anecdotal: a summer berry picker might be intimidated by low growls from the understory, or an autumn fi sherman might return home wide-eyed, reporting fresh pugmarks on a muddy riverbank that hadn’t been there the day before. But in the late 1980s, thawing political tensions, emerging technologies, and the prospect of new discoveries cracked a door of opportunity for Amur tiger research in Russia.

Maurice Hornocker, an Idaho-based carnivore specialist, had spent his career studying solitary cats, from cougars in the United States and jaguars in South America to leopards in Africa. He was instantly likable and spoke with a gentle western drawl that rolled easily into a laugh—a folksy persona that should not be confused with naïveté. Maurice was sharp, opinionated, knowledgeable, and well-read; he was also a naturalborn storyteller with a life full of adventures. He would often quote Mao Zedong saying “All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience,” while pulling a calloused hand across the thin gray stubble of his unshaven face.

Maurice was born in a south Iowa farmhouse in 1930 and as a teenager moved to Montana, where his interests in wildlife started early. After attending the University of Montana for undergraduate and master’s degrees, he took on a PhD study of cougars in 1964. He worked under the legendary wildlife biologist John Craighead, who, along with his twin brother, Frank, had pioneered radiotelemetry in the 1950s using old

navy equipment. The Craigheads later worked with NASA to attach the fi rst satellite collar to an elk—nicknamed Monique the Space Elk—an innovation that led to the development and use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology in telephones, automobiles, and other electronics. John believed that research was not just a job but a way of life, and he instilled in Maurice the idea that “there is no greater joy than that of discovery, and the creation of new knowledge.”

Maurice was frustrated that the focus of wildlife management in the United States was traditionally limited to game species: ungulates (or hoofed mammals) like mule deer, elk, and bighorn sheep. Through the 1950s, the pervasive attitude among managers toward predators was one of wildlife persecution: cougars, wolves, coyotes, and other predators were considered parasites on nature, gluttons who ate too many ungulates, and so were targeted by aggressive government eradication efforts. But some, like the Craigheads and the ecologist Aldo Leopold, saw it differently. In Leopold’s consequential work A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949, the scientist described the moment he started to see carnivores as part of nature, not something to be removed from it, when he shot a wolf in 1912:

We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fi re dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fi re die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.

Maurice, influenced by the Craigheads and Leopold, believed the same. As virtually no studies in North America had investigated how cougars fit into nature—a system that had functioned beautifully for thousands of years before humans came along and started killing them—Maurice sought to do so himself. He adapted the Craigheads’ methods of radiotelemetry to cougars and developed policy recommendations to restore balance to the ecosystem. “We have to know what the natural situation is before we can mend our mistakes,” he explained. Maurice continued the cougar project until 1973. His curiosity about solitary wild cats seemed insatiable and, with dual positions at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the University of Idaho, Maurice began taking on graduate students to study other poorly known cat species: bobcats in Idaho, jaguars in Brazil, and leopards in Africa.

One species of solitary cat perpetually missing from Maurice’s personal body of knowledge was tigers, so he began looking for ways to engage. In the early 1970s, under contract from the Smithsonian Institution, Maurice joined a team that traveled to South Asia hoping to initiate a large-scale study of tiger population dynamics. The landscape he found there, however, was too fragmented and fi lled with too many people for any possible study of the tiger’s natural ecology.

Just as one potential pathway closed, another emerged. Maurice received a letter from Dr. Yevgeniy Matyushkin in Moscow, an ecologist who studied Amur tigers and had read about Maurice’s past radiotelemetry work. Seeing this technology as the key to revolutionizing tiger study in his home country, Matyushkin invited Maurice to the Soviet Union. But this was still the 1970s; Maurice was still a federal employee. Political barriers fashioned from mistrust prevented the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union from allowing such a

collaboration to germinate. And so, despite the invitation, the tiger forests of eastern Russia remained behind the Iron Curtain.

At about the same time, President Richard Nixon’s official visit to Beijing in 1972 precipitated a thaw in relations between the United States and China, and led to a period of cultural and scientific exchanges. This offered Maurice another opportunity. He joined an American delegation of academics who spent six weeks at Harbin University, in northeast China’s Heilongjiang Province, in the early 1980s, presenting a lecture series on wildlife management. While there, Maurice spoke with local scientists and toured the countryside, probing for any information he could fi nd about Amur tigers.

What Maurice saw in Heilongjiang Province discouraged him: a hundred years of intensive land use instigated by the 1860 Convention of Peking. The change was so pronounced that the China-Russia border today is discernible on satellite imagery. Maps show the browns of Chinese agricultural lands on one side transition abruptly to the greens of Russian forests on the other. In one Chinese village, a farmer told Maurice through an interpreter that no one had seen a tiger nearby for generations. The animals had lived there once, but with high human population densities, poacher snares in the remaining forests, considerable habitat conversion to farmland, and low prey availability, Maurice doubted that conditions could support them any longer. In fact, he was surprised to learn later that there may have been as many as thirty Amur tigers in China at that time.

By the late 1980s, Maurice had retired from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to start his own organization, the researchfocused Hornocker Wildlife Institute, housed at the University of Idaho. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union opened up as China had; cultural and scientific exchanges proliferated between the United States and Russia.

In 1989, Soviet researchers visited Idaho as part of a scientific exchange program. Clustered around a fi repit, they told spellbinding stories of Amur tigers. Yuriy Puzachenko, a wellrespected and influential ecologist, spoke of cats that were built like battering rams and thrived in the wilderness of his country’s southeast, in Primorye.

The province of Primorye dangles from the jaw of eastern Russia like an eyetooth, long and sharp, fl anking the Ussuri River and China beyond it on one side, and stretching along the East Sea (or Sea of Japan) between 48 and 42 degrees latitude on the other. This is the equivalent of the length of the Washington and Oregon coasts in North America, or the distance from Norway south almost to Rome in Europe.

Winters are deeply and dangerously cold in Primorye; the landscape shivers under a heavy quilt of snow for five months of the year. The raccoon dog, a species found in Primorye and as far south as Vietnam, doesn’t hibernate anywhere else in its natural range, but chooses to wait out Russian winters in burrows. It is the only canid species that hibernates. Inland, some parts of the province record an annual average of eighty centimeters of precipitation, with typical January temperatures hovering around −23 degrees Celsius. Conditions along the coast are milder, but the trade-off is the wind, especially in January, with average hourly windspeeds of twenty-one kilometers per hour and gusts regularly exceeding fi fty kilometers per hour.

Spring presses a dense fog to the province’s coastal cliffs, stunting vegetation growth, then lifts to reveal a hot and humid summer, when Pacific swifts cut lines through the sky to gorge on swarms of insects. Typhoon season peaks in August and September, when Primorye’s residents—wild or otherwise—seek cover from heavy rains and punishing winds. The storms are sometimes significant: Typhoon Lionrock in 2016 battered the

province with howling 108-kilometer-per-hour winds, leveling four hundred square kilometers of forest. In autumn, Primorye’s rolling hills are afl ame with color as senescing maple, oak, birch, and larch pay tribute to the end of another year.

As he spoke, Puzachenko described the tigers of Primorye as solitary creatures adapted to mountain and pine: ice-fringed apparitions that burst from shadow to ambush their favorite food, wild boar, prey that can weigh as much as a grand piano and can have tusks like sharpened knives. The Russian also told of the intrepid researchers who studied the Amur tigers, men almost as wild as the predators themselves, who sacrificed comfort and safety to advance our scientific understanding of this endangered species.

Alas, Puzachenko lamented, global advances in VHF radiotelemetry, which allowed for remote tracking and had been accessible to Western scientists since the 1960s, had not yet reached the Soviet Union. As a result, Amur tigers could be studied only in winter, when their massive tracks could be followed in the snow. What happened outside of winter, he said with a shrug, no one knew: tigers were too cryptic and too cautious to be observed directly for any meaningful period.

Fortuitously, Howard Quigley, fi nishing his PhD under Maurice Hornocker at the University of Idaho, was listening from the far side of the fi re. He leaned forward when Puza chenko stopped, the light from the fl ames reflecting off his glasses and causing his beard to shimmer. “Maybe this is something we can work on together,” he offered.

Howard shared the details of that fi reside discussion with Maurice, who immediately recognized a new opportunity to study tigers—his most realistic shot yet. The collaboration was not without precedent. In 1987, only two years earlier, Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev had introduced the Soviet Joint

Venture Law as part of his perestroika program, a sweeping set of reforms intended to infuse innovation and cash into the stagnant economy. Under this law, foreign entities were invited to work with Soviet industries to produce, market, and distribute Russian goods that could be competitive on the global market. Russians would provide manpower and logistical expertise, while foreigners would contribute funding and technical support. The Siberian Tiger Project would follow this same model, but instead of a commercial product, their output was information about an endangered species.

Within the year, Maurice and Howard had arranged a trip to the Soviet Union to meet with Puzachenko in Moscow, then continued on to Vladivostok, the capital of Primorye, in January 1990. Vladivostok was a dull city with a colorful past, tucked into a secluded bay once ruled by the Balhae, Jurchen, Ming, and Qing empires for a thousand years before the Russians arrived. The Soviets had banned free travel to Vladivostok in 1958, not just for foreigners but for Russians as well: their Pacific Naval Fleet lay hidden among folds of coves and inlets around the city, and the government hoped that the restricted access would shield the navy from spying eyes. The simple presence of two Americans in this closed city spoke to Puzachenko’s political influence. It was cold and overcast in Vladivostok. Maurice and Howard met with Dima Pikunov and Igor Nikolayev, giants of the Soviet tiger world and among the men mentioned by Puzachenko around the Idaho campfi re. Maurice and Howard were impressed; an apt descriptor commonly attributed to Dima Pikunov was zrivniy—explosive. Packaged tight within his skin was so much passion, stubbornness, and opinion that he periodically vented like a volcano, bellowing unpredictably in joy or rage. The writer David Quammen, who spent time with Dima in Primorye while researching his book Monster of God, described

him as “a cross between Mel Brooks and Nikita Khrushchev.”

Dima was not tall, but he was imposing: built like a steelworker, with broad shoulders and calloused hands, and doggedly devoted to tiger research. He had once spent weeks tracking a single male tiger, following the animal in the snow, himself eating only the scavenged remains from the carcasses of deer and boar that the tiger had left behind. Igor Nikolayev was almost the reverse of Dima—diminutive and quiet—but his dedication to tigers was no less passionate. With a face of wrinkled leather and a ropy body jettisoned of everything but raw muscle, he was like a heavy-smoking, hard- drinking Bilbo Baggins; the tiger was his Ring.

THE PROSPECTIVE Soviet-American research team needed to settle on a study area, some location where they could expect to capture and monitor a population of tigers in their natural habitat. Dima and Igor drove the Americans north, into the forests, where Maurice was instantly enamored by the pristine habitat he found in Primorye. This was what he’d hoped to see in China in the 1980s. The mountains they drove through, the SikhoteAlin, reminded Maurice of the Sierra Nevada in the American West, and the coastline was like the Pacific between San Francisco and Seattle. The Sikhote-Alin is a low, long range that rises in the south of Primorye, clings to the East Sea coast as it moves north, then sinks back into the land just before reaching the mouth of the Amur River some twelve hundred kilometers later. Maurice was fascinated by the vegetation assemblages that, according to what he knew about temperate forests, shouldn’t be found here: kiwis, apricot, yew, and ginseng grew alongside birch, pine, and oak. This section of northeast Asia had escaped glaciation during the Pleistocene, and as a result served as a

refugium for plant and animal assemblages found together nowhere else on earth, a blend of subtropical and boreal species swirled in a temperate forest. Peter Matthiessen would later visit Maurice in Primorye to research his book Tigers in the Snow. The well-traveled author considered Primorye’s coast one of the most beautiful places he’d ever been.

Radiotelemetry would be a key component of the project’s success. The concept behind it was simple: attach sturdy collars to as many tigers as could be caught, then monitor the predators yearround from afar, using a directional antenna and receiver to triangulate their approximate location based on the strength of the signal. Maurice embraced technologies like this but recognized they were not a panacea. He believed that innovations should guide researchers in how to more efficiently explore wildlife habitat, not remove them further from it. The proliferation of tracking technology in the 1990s meant that more people were spending less time in the field. Too much reliance on remote investigation, Maurice contended, erected a wall of technology between researchers and their subjects. When learning comes at a computer, not in the forest, important nuances can be missed.

Citing Aldo Leopold’s wolf anecdote as an example, Maurice remarked, “Leopold changed his whole philosophy to conservation when he saw the green fi re. If he’d been staring at data points on a computer screen, he would have missed it.”

Once the biologists acquired a tiger’s location, they had to visit the spot to understand why it was of interest. By gathering a database of hundreds of such locations from multiple tigers across many seasons and years, scientists would gain an understanding of how a population of wild tigers lived and interacted. It would tell them where tigers went and how much space they needed. Any discovered prey remains would give them clues about the tiger’s diet.

Due to the confl icting needs of the project—an area sufficiently remote to fi nd tigers yet also accessible enough for the biologists to track them—Maurice was curious to see what the Russians proposed as a study site. The fi rst area to which Dima and Igor brought the Americans was the inland Iman River basin in the central Sikhote-Alin Mountains, where Igor had led a study of tiger ecology in the 1970s. Maurice could see a project working in the area: there were tigers to be caught and roads to help the team monitor them, but it wasn’t perfect. These forests had a relatively high human presence, with 70 percent of Igor’s study area subject to logging or other natural resource exploitation, like hunting and trapping. Maurice was most interested in learning how tigers functioned in undisturbed habitat; he’d consider the Iman basin but fi rst wanted to see what else Primorye had to offer.

The team chartered a helicopter to the Bikin River basin, a wild landscape of braided river channels and dense forest framed by steep cliffs in northern Primorye where Dima had spent time working with indigenous Udege. From Maurice’s perspective the Bikin basin was suitably remote, but almost too much so for a scientific study of a wide-ranging species like the tiger. A lack of infrastructure along the Bikin River would make it almost impossible to efficiently track tigers—very few roads meant travel was mostly by foot, boat, or snowmobile.

Their third stop was the Sikhote-Alin Nature Reserve, headquartered in the village of Terney along the seacoast. It was immediately clear to Maurice and Howard that, while all sites they visited in Primorye could potentially host a tiger research project, this was the only location suitably wild and with the necessary infrastructure to handle what they proposed. It met all their criteria of undisturbed yet accessible habitat: roads ringed most of the protected area, allowing for quick access to three

thousand kilometers of forest with no logging or hunting. About five hundred kilometers of foot trails cut through the reserve as well—narrow, blazed paths that followed rivers and crossed mountain passes, linking more than fi fty small cabins placed like way stations every ten kilometers or so. This meant that no matter where their tiger tracking took them, a warm, dry shelter would usually be no farther than half a day’s walk. The Siberian Tiger Project had found its field site.

BACK IN THE UNITED STATES , generating support for this initiative was surprisingly difficult. Maurice had a Rolodex of potential funders who had donated to his cat conservation work in the past. But few saw this potential work in Russia in the same light he did. First, his peers in the carnivore world were doubtful of the plan’s viability. Maurice was especially irritated by the response from one specialist, who had experience with tranquilizing tigers in southeast Asia and was adamant that the only way to catch a tiger was by using elephants, as they did in Nepal. There, biologists had adapted the art of royal tiger hunting to their purposes, using three elephants and a dozen people. Once they knew a tiger was in a certain area, unseen in the tall grasses but lingering on a kill perhaps, field assistants would lay out two rows of bright white cloth about four hundred meters long to fl ank the area. These cloths, which tigers instinctively avoided given their fl ashy and alien nature on the landscape, angled in like a funnel to meet at some strategic location where researchers balanced in the crooks of trees with tranquilizer guns. Men on elephant back, called beaters, then moved noisily into the funnel mouth, pushing the tiger toward the open space where the cloths met the darters’ crosshairs. Given the lack of pachyderms in Russia, the specialist contended, Maurice’s project was doomed from the