The Glass Mountain

Escape and Discovery in Wartime Italy

Malcolm Gaskill

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Malcolm Gaskill, 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Set in Dante 12/14.75pt

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–0–241–62259–9

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For my mother, Audrey, and my friend Domenico with love, admiration and gratitude and in memory of the fugitives Ralph and Charlie

‘Our concern with history . . is a concern with pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere . . . [and] when memories come back to you, you sometimes feel as if you were looking at the past through a glass mountain.’

W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz, trans. Anthea Bell (2001)

‘There is no complete life. There are only fragments.’

James Salter, Light Years (1975)

Prologue: The Dream

Late summer, 2017. We – my wife, children and I – drove from Cambridge across country to visit my elderly parents in Shropshire, a journey of a couple of hours or so. My sister, who lived nearby, invited us for tea in her spacious garden, which backed on to rolling meadows, resplendent that day under a valiant sun and cornflower sky. The warm air was tinged with eucalyptus, lavender and mown grass.

It was a perfectly ordinary occasion – but ordinary is where the uncanny creeps in, takes you by surprise. I was chatting to Mum about the usual things – kids, work, the book I was writing – when, quite abruptly, she said: ‘I had a strange dream about Uncle Ralph last night.’ Perplexed, she looked away, frowning to recover the memory. ‘He stepped out of the shadows and held me by the arm – as if pulling me back.’

Pulling her back where, Mum wasn’t sure. ‘To when he was alive?’ I suggested. She shrugged, as if that was all she had. But we both sensed the past had called on the present, that this wasn’t just some random flotsam from the subconscious. More like a visitation, a haunting, which is how it can feel to dream of the dead.

I knew a bit about Ralph, though I’d never met him. A soldier in North Africa, a military policeman, he’d escaped from a prison camp and hidden in a farmhouse. It was all I remembered, and even that could have been wrong. I once had a couple of photos of him; perhaps they were still around somewhere.

Then, another sliver of recollection: ‘Didn’t he take you on holiday to Switzerland, when almost no one went abroad – and in a car?’

He did, replied Mum – but the whole thing was a virtual blank. She looked dumbfounded, which wasn’t like her at all. Even in her late eighties her memory was impeccable.

Prologue: The Dream

‘It must have been about 1955 or 56,’ she said. ‘It couldn’t have been much earlier, because I was only twenty, and no later, because Dad died in 1957, and I’d never have left Mum and John on their own.’ This made sense. John, her brother, was only eight when they lost their father, after which my grandmother wore her grief heavily for the rest of her days. Her name was Charlotte; I called her ‘Nan’. Nan’s younger sister Florence – or Flo, as she was known – had married Ralph just before the war.

Mum’s scant memories of this Swiss trip were like old photos, a scatter of silent, faded scenes. Picture-postcard chalets with wooden shutters. Sunshine and snow. Washing in a stream. Wearing white sandals by a lake. Being taught how to smoke by Flo, who, Mum noticed, was missing part of a finger. That was all.

Why did Ralph and Flo go to Switzerland? Mum had no idea. Did she like them? Not really. So why go with them? ‘I expect I just thought this was my chance to go abroad and I should take it. That, and the fact they saw me as the child they’d never had. Perhaps I felt sorry for them.’

Auntie Flo was, she continued, very particular. In 1940, as little Audrey Davis, Mum had been evacuated to live with her in the Yorkshire town of Wombwell, near Barnsley. The train was full of soldiers, and they’d got off at the wrong station because the signs had been taken down to confuse German parachutists. At Wombwell, Flo wouldn’t let Audrey touch her piano unless she scrubbed her hands. Mum didn’t recall Uncle Ralph having been there – he was probably already away at war – but later she’d known him well. What was he like? ‘Well . . . you couldn’t get close to him. Stiff, he was. Stiff and cold.’ Ralph’s father, Thomas, who worked on the railways, used to give Audrey sweets and was a kinder soul, as was Ralph’s younger brother, George.

Tea was poured and cake passed round. Swallows darted in and out of the eaves; a rook cawed. Conversation and togetherness, the now-ness of the present, tangible yet vulnerable to irruptions of the past.

Two things drifted into my mind. Hadn’t Ralph kept a diary? And

xviii

Prologue: The Dream

cut his way out of a train? Yes, Mum said, she thought both things were true.

We stared at each other expectantly. We knew no more – but we would. For that summer’s day marked the start of a journey of discovery into Ralph’s life and adventures in wartime Italy. Like so many of the twenty million Allied servicemen – British, Commonwealth, US and others – overseas between 1939 and 1945, he had been wrenched from the innocence of an ordinary life and thrust into terrible experience. Nearly 700,000 died; another 100,000 were never heard of again. Some who survived had epiphanies; most did not. A million men had been wounded, many maimed or weakened in body or mind.1

And they came home to a world familiar yet different – the old dispensation utterly changed – and to families who, in turn, found their sons and husbands and fathers transformed. And too often these men’s tales of hardship and trauma were kept private within marriages or never told at all. Although often similar, each story was unique, and Ralph’s was exceptional.2

Seven years on, recalling Mum’s dream, it seemed less like he had been pulling her back into some shadowy past, and more that she’d pulled him forward into the present. For even then, at the very beginning of everything, his silent, inscrutable ghost was edging out of the gloom, daring us to know him properly.

Part one Becoming

War Relics

A Sunday afternoon in 1976. I’m nine years old, at home in Kent watching a war film, Von Ryan’s Express. Ryan, a US pilot, played by Frank Sinatra, arrives in an Italian prisoner of war camp pitching the ‘why bother escaping’ argument against the ‘it’s our duty at all costs’ line taken by Trevor Howard’s British officer. Italy surrenders and the Germans put the POW s on a train bound for the Reich. But Ryan, who has come round to the idea of escaping, breaks through the carriage floor and leads the men out. Seizing control of the locomotive, they switch destinations from Innsbruck to neutral Switzerland.1

There were always old films like this shown on Sundays, full of danger and courage and swelling pride. The myths of the Second World War they played to were ingrained in British culture, a balm for economic decline and the loss of empire. Without a sense of destiny, the future was a scary place: all the country had to look forward to was the past. And there was no better past than the war: six years of finest hours, when people had proudly united to defeat Hitler. What did 1976 have to offer? Soaring inflation, terrorism and the snarl of punk, an affront to patriotism and civility. God seemed tired of being an Englishman, and that summer visited a biblical drought upon the land.

For boys like me, nostalgic rituals mattered less than the war’s sheer violent excitement. We eagerly did our bit as consumers of not only films, but comics such as Warlord and Victor, and graphic novellas in the War Picture Library and Commando series. Bedrooms bristled with model soldiers, action figures and construction kits. The planes dangling from my ceiling were riddled with hot-needle

The Glass Mountain bullet holes and billowed singed cotton-wool smoke. We dressed up to re-enact ghost battles that rippled benignly from another age. Dad carved me a Sten gun and a grenade with a pullable pin, while Mum made a green pullover with sergeant’s stripes and an elasticated beret that sat on my head like a shower cap. A friend’s brother built us a box cart painted like a German jeep, which we crashed and nearly died laughing.2

The same friend also had a Colditz board game. (Much later, chasing that memory, I bought a set in a charity shop only to find half the pieces, each representing a prisoner, were missing – or ‘escaped’, someone joked.) A TV series about the famous castle was still running in the mid-1970s, when I received an Action Man Colditz set for my birthday. I can still see him hanging from the washing line with one hand, cardboard suitcase in the other. At secondary school, I spent a fortnight of lunch breaks in the library gripped by Pat Reid’s memoir on which the dramatization, game, toy, and an earlier feature film, were based.3

Hardcore war enthusiasts were also avid collectors. Having begged Mum to try knitting me a gas mask, I bought a real one from a junk shop in Gillingham, owned by a man known as ‘Fifty-Pee Brian’ owing to his inflexible pricing strategy. It took half an hour to cycle there, but I was a regular. The shop window was like some historical shore, military medals and badges washed up there – context gone, cut loose by time. Relics were props for imagining the past, with talismanic power, opening a conduit back to the war. All this spoke meaningfully to my young life. At the Queen’s Silver Jubilee street party in 1977 – itself an echo of VE Day celebrations – I wore the musty gas mask and other paraphernalia for the fancy dress parade. There’s cine film to prove it.

Intimacy with the war also came from family connections. Yet both my grandfathers had been in reserved occupations – Manchester lorry driver on Dad’s side, electrician in Chatham Dockyard on Mum’s – whereas all my friends’ grandfathers seemed to have landed in Normandy, been shot down over enemy territory or torpedoed in the Atlantic. I had some stories. One relative had fought

in France – he gave me the dog tag he’d worn – and Dad’s cousin Billy had been killed in Germany in 1945, the only casualty on a day when his company commander won the Victoria Cross. Aged six, Dad himself was nearly killed in the Salford Blitz, and Mum once hid under a deckchair when a flying bomb crashed at Gillingham Strand. During an air raid, Nan had refused to let my granddad into the Anderson shelter because she was bathing in the tin tub. And this was after he’d raced home from work because incendiary bombs were falling.

The scene of this comedy was a Victorian terraced house three miles from our own, and Nan still lived there when my sister and I were small. It hadn’t changed much since the war. The front room was a mausoleum of polished wood and lace doilies, where I never went except to read a book with an embossed red cover about the lives of soldiers and statesmen, explorers and inventors.4 There was no bathroom, nor any heating except for a coal fire in the sitting room, and instead of a fridge Nan had a meat-safe in the cellar. Out in the yard, a spider-infested privy stood next to a vegetable patch, and further down the garden, among the nettles, the corrugated bomb shelter was rusting away. I remember fireside baths and fetching potatoes, which felt like digging for victory. It was the best place to hear Nan’s war stories. As I listened, one relative stood out: my great-uncle, Ralph.

After the visit to Shropshire in 2017, I found myself thinking about those days, and about Uncle Ralph. Although each time Mum and I spoke on the phone she would say, ‘I still can’t find a little corner of my memory about going to Switzerland’, more of Nan’s words came back to me as I ransacked my study cupboards looking for old photos.

Soon, I’d established five things that Nan had told me back then: Ralph had been a prisoner of war in Italy; punched an Italian officer, breaking his nose; escaped from a train using, of all things, a knife and fork; hidden in a hayloft, where a family nursed him when he was sick; and written a diary. In 2017, as in 1976, I wanted everything to be true. The train escape seemed improbable, especially as this

The Glass Mountain is what happens in Von Ryan’s Express, a film about as far-fetched as war stories go. But I was convinced that Nan had told me all this, so presumably she’d got it from Ralph or Flo. Unlike the academic history from which I’d made a career, family lore doesn’t insist on documentary proof. It’s just a loose collection of stories, mostly unchallenged, that makes sense of the past.

I found Nan’s photos, which long ago I’d put in the wooden box that once contained treasures from Fifty-Pee Brian’s shop, now washed by time to another shore. One showed Ralph cross-legged at a training camp; in another he was a Guardsman in a bearskin, like a sentry at Buckingham Palace; and the third was a portrait of him wearing an unidentified uniform, complete with a row of medal ribbons, meaning it must have been taken after 1945. It dawned on me how much Ralph had tethered me to the war, and how Nan’s snaps, as she called them, had lent substance to her stories, tall though they probably were. They were mine and I’d cherished them like myths.

A door shouldered ajar by Mum’s dream was now fully open after

forty years. In that time, Ralph and Nan had both died, and for me the war had been displaced by music, guitars, girls and books. A longing to leave the Medway Towns propelled me to university, where, in different institutions, I hung around for the next three decades teaching the social history of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. My final years of research had been spent exploring historical inner lives, extracting emotion from stories in the archives. Storytelling is embedded in histories, and history a way of telling stories.

This prepared the ground for what was to come: a seed sown in the 1970s germinated decades later by a dream, then flowering into the reanimation of Uncle Ralph’s life. At first, I had little sense of what lay ahead, no plan or even a clear intention. I was curious about Ralph and my childhood fascination with the war, and that curiosity led me deeper into the story.

I pulled up outside a bungalow in Warmsworth, a suburb of Doncaster in South Yorkshire. A woman in her seventies opened the door and introduced herself as Pauline, my mother’s cousin. We’d never met before, but she seemed familiar, having a faint look of Mum and some of her mannerisms. Soon after the Shropshire visit, it had occurred to Mum that if anyone had Ralph’s war diary it would be Pauline, since her father was Ralph’s brother, George, and Ralph had had no children to inherit his effects. Thinking about Ralph had started me wondering about the diary. If it still existed, I knew I had to see it.

We chatted as the kettle boiled, but the folders and papers and albums, which Pauline had brought down from the attic and piled on the work surface, made it hard to concentrate. I was feeling the ‘affective tremor’ that afflicts historians, the spooky anticipation of handling documents so long imprisoned in silence yet screaming to be heard.5

Pauline handed me a scuffed manila envelope. Inside were three Italian school exercise books with faded illustrated covers: a skiff idling on a lake, speedboats racing, a family of rabbits. I turned the fragile pages crammed with copperplate – the remains of a life and

The Glass Mountain its vanished world levelled and compressed into blue-black script. Thrillingly, the opening sentence read: ‘Contrary to enemy propaganda life in a prison camp is not a happy one, and every ex-prisoner of war will, without exception, second that statement.’

I moved on to the photos. Pauline pointed to Ralph and Flo’s wedding portrait from 1938, with Mum as a three-year-old bridesmaid standing just in front of the groom. Then we jumped forward to a middle-aged Ralph dressed like a British army officer, with peaked cap and Sam Browne belt. Flo, at his side, looked blithely refined in polka dots, gloves and bonnet.

I sensed that Pauline hadn’t liked Ralph much. She gestured at an open box-file, in which I found letters of notification, certificates of education, a pay book, a typed document in Italian, a notelet to Flo written in a prisoner of war camp and a report in Spanish recording Ralph’s death. There was also a dossier on the history of the Corps family – an old Anglo-Norman name pronounced ‘Corr’.

There in front of me lay the full span of Ralph Corps’ life – or as much of a life as fits in a box. Pauline lent me the diary, and on the drive back I felt its radiant presence on the passenger seat. Without my being fully conscious of it, the power of this relic in my possession had activated a quest.

Back home in Cambridge, I looked closely at the diary. The exercise books – or quaderni – had a distinct prewar look. ‘Book No. 1’, as Ralph had labelled it, was the one with the skiff on the cover. The reverse identified Lake Garda, and inside the front cover Flo had written her name three times – ‘Florence E. Corps’ – as if practising a signature. Beneath, she had added ‘Kingolwira Prison Farm, Kingolwira, Tanganyika’; above, in a larger, curvilinear hand, was pencilled ‘Chiodi Agostino, Paitone (Brescia) Italy.’

I scoured the second quaderno for clues – not yet the text but rather the covers. In tiny writing on the inside, Ralph had quoted someone he had thought was Disraeli, but was actually Philip James Bailey, an obscure Victorian poet: ‘He most lives who thinks most, feels the noblest, acts the best’. And in spare pages at the back were scraps of poetry he’d learned at school. There was also Italian vocabulary:

Davvero? = really?; comportarsi = behave; insegnare = to teach; mi sembra = it seems to me . . .

The rabbits, happy on the front cover, were on the back being made into hats with the smiling approval of two elegant women. I got the gist of the text, which had a totalitarian ring to it: breeding rabbits on an industrial scale benefits the national economy by providing not only felt and fur, but delicious food for the working masses.

The third quaderno, with the speedboats, bore the fascio littorio, the Roman bundle of sticks that had been the Italian fascists’ emblem. Ralph opened this notebook with a list of self-improving Latin tags relevant to his life and, as it happened, to my growing curiosity. ‘Verba volant, scripta manent’ (spoken words fly, written ones endure), ‘Prima frons saepe decipit’ (the first look often deceives) and ‘Mens agitat molem’ (the mind can move mountains).

Once I’d started on the text and had got used to Ralph’s slanted hand, I found I couldn’t stop. It was like being drawn through a rent in the fabric of time. It was immediately clear that this wasn’t actually a diary, rather a memoir of POW life and an escape, which, judging by the stationery and the inscribed Italian name, must have been written soon after the event. Although the prose was mostly descriptive, Ralph hinted at deeper meanings. ‘Had it not been for later events which occurred to me on Italian soil’, read one statement, ‘I should have returned (by God’s Will) to England and hated Italy and Italians for the rest of my days.’ This suggested reluctance to assume he’d ever get home – but home from where exactly? The farmhouse where Nan said he’d been? Was ‘Chiodi Agostino’ his host?

Paitone, I discovered, is a hamlet near the town of Prevalle, between the north Italian city of Brescia and the great open body of water that is Lake Garda, 100 miles south of the Swiss border. Paitone is small and unremarkable: there seemed almost nothing to learn about it. The memoir didn’t specify what ‘later events’ had changed Ralph’s mind about Italians, presumably something to do with the inhabitants of Paitone. I knew only what Nan told me: a family had cared for him when he was poorly.

The Glass Mountain

I read on. Ralph had escaped from Campo Prigionieri di Guerra Sessanta-Cinque Gravina-Altamura – Camp 65 for short. The town of Gravina was a long way from Paitone, 600 miles south down the boot of Italy to Puglia at the top of the heel. Astonishingly, not only was the site marked on Google Maps but some buildings still remained. Even more astonishingly, a local enthusiast had just a few days earlier conducted a tour of the camp and posted footage on Facebook. His name was Domenico Bolognese. He replied to my email at once, full of excitement.

Domenico – Dom – was about my age and lived in the small Puglian city of Altamura, three miles east of the camp. He was married with teenage sons and worked as an export manager for a furniture company. His spare time was devoted to preserving Camp 65’s memory through a small association, of which he was founder and president. These days, he explained, the struggle to remember was fraught. The political right was less concerned with commemorating Italy’s enemies – specifically, in this case, Britain and its Commonwealth – than with the massacre of Italians by Yugoslav partisans, hundreds of whom had trained in the repurposed Camp 65 after Italy surrendered in 1943.

Dom sent pictures of the camp, adding a visual setting to the memoir. Ralph’s spectral outline thickened. I worked though copies of documents and photos I’d made of Pauline’s archive, often late at night and before sunrise, reading between the lines and staring at images as if to make them disclose their secrets.

There was Mum, barely twenty, posing with Flo on a snowy peak; another showed them sitting outside a café. As I pressed these relics for meaning, so the image of the mountain, a romantic metaphor of self-discovery, imprinted itself differently. In Austerlitz, a novel about a twentieth-century life disfigured by war and unruly memory, the German writer W. G. Sebald invokes the image of a glass mountain, a mystical symbol with the indeterminacy of dreams and their power to reveal truth. Through this cloudy prism, hopes are both raised and restrained: you can know the past, the mountain promises, but only imperfectly. Nothing on the other side remains intact,

and it’s up to us to find the pieces, in dim light and in darkness, and from them make a story that in good conscience feels real.

When Tolstoy once said that ‘history would be an excellent thing if only it were true’, he wasn’t trying to be funny. By ‘true’ he meant ‘as it really happened’ – much as when his German contemporary Leopold von Ranke declared that history should be ‘as it actually was’, he was idealizing something that posterity cannot truly own because it’s locked in time’s glacier, a frozen shower of distorted fragments.6

The next seven years would be taken up finding these fragments and piecing them together. Propelled by Mum’s dream, I found myself sitting in far-flung libraries and archives, hiking up rocky hillsides, splashing through autumn mud, sheltering from storms. I visited old barracks and remote farms, neck-hair prickling as the ghosts flared past, and met Italians with long memories who shared their stories. That sense of engagement and halting discovery mattered as much as the wartime events they revealed. These could only live again because, like the departed Ralph, they were dragged from the gloom.

Research became everything it should be: a journey into the unknown, leading to some of the most exciting discoveries of my life as a historian.7 And along the way, I would make some incredible friends – as, it transpired, had Ralph. He may never have spoken of this intimacy; it certainly didn’t colour the war stories he told his family. His feelings were but flecks and flaws in the glacier – but once they became known, as they did, they breathed life into an unexpected, absorbing story.

Having borrowed a title from Sebald, I came across a 1949 war film of the same name about an RAF observer shot down in the Dolomites and nursed by a young Italian partisan. ‘Call your lover’s name in the mountains’, she says, ‘and you will hear a mournful echo.’ And that, in a way, was what I ended up doing too, gazing at the glass mountain, quietly obsessed, straining for sounds and glimpses of movement through the ice.8

A Perfect Gentleman

For the next couple of years, Uncle Ralph’s story emerged slowly yet steadily. My curiosity about him grew, but the demands of my own life kept me from satisfying it. Meanwhile, faint wraith that he was, Ralph waited patiently for my full attention.

During this time, Dom, the Italian expert on Camp 65 I’d found on Facebook, became a constant presence in my life. He sent regular messages, and more photos and documents relating to the camp; in return, I told him what I knew about Ralph’s captivity and cool reserve, his buttoned-up dignity. Away in Puglia, Dom worked Ralph’s story into tours of the camp ruins, which he laid on for people in Gravina and the neighbouring town of Altamura, mostly school children innocent of the events of the war that had unfolded on their doorstep. He also received visitors, mostly from South Africa and New Zealand, drawn to see the place they’d heard about from fathers and uncles. Soon Dom and I – kindred spirits, in middle age, shaped by our generation – began to talk about things other than the war. The formalities fell away, and we chatted like old friends, by email and on the phone.

All my free time, such as it was, I spent assembling what turned out to be the easiest part of the research: Ralph’s backstory. Something of the man I knew from the memoir, which covered little more than a year, was surely there in his prewar past. I speculated about Ralph, fictionalized him in my head, even dreamed about him. I didn’t know exactly why I was stalking him, only that he had entered my life and I was compelled to find out about him and his war. Perhaps, Dom playfully suggested, Ralph was stalking me.

I ordered birth and marriage certificates from the General

A Perfect Gentleman

Register Office to learn more about Ralph’s immediate family – my extended family – and also drew on what Mum and Pauline and other relatives knew. There had been numerous documents in Pauline’s archive, some relating to Ralph’s military service, and I printed copies to read by lamplight, peering closely, annotating them. Much I could do online. I subscribed to Ancestry.com, and scoured the web for local history sites, chatrooms, maps and catalogues. I contacted a man in Doncaster knowledgeable about local schools, Ralph’s in particular, and read around the context of his childhood: the environment that had moulded him into adolescence.

As research progressed, I arranged my notes in narrative order, plugging or eliding gaps as I went. Whenever a new fact surfaced, I’d phone Mum, whose memory it sometimes jogged. By these means, the light cast on Uncle Ralph’s expectant figure grew brighter, and the lineaments of his early years, scattered and flattened by time, were raised from dim memory and old papers into a third dimension. To my surprise, it became possible to flesh out the evasive character in the memoir, even recovering Ralph’s attitudes and ambitions, and the strengths and weaknesses that the test of war exposed in him.

Ralph Corps was born on 9 May 1914 at 16 Albert Road, a terraced two-up two-down in Mexborough, near Doncaster. A centre for mining and pottery, by the mid-nineteenth century the town was also a thriving railway depot, where outsiders found work and insiders dreamed of leaving. It produced footballers and boxers and trades unionists, as well as poets and actors. Mexborough’s most famous soldier was William Hackett, a miner in a tunnelling company who in 1916 won a posthumous Victoria Cross. For Mexborough’s boys, Hackett was a paragon of Christian sacrifice. Methodist churches and cooperative and temperance societies taught thrift and hard work, self-discipline and self-reliance.

The Corps family were sober, law-abiding patriots, church rather than chapel, exemplars of upper-working-class respectability. Ralph’s father, Thomas, had eschewed his own father’s life

The Glass Mountain as an agricultural labourer in the Yorkshire Dales and come to Mexborough to improve himself. Hired as a railway fireman, he met twenty-two-year-old Gladys Catherall from the Welsh town of Holywell, whom he married in 1913. Ralph was born the following summer, named after his maternal grandfather. Three months later, Britain was at war. Thomas and his younger brother George both fought on the Western Front, where George was killed. In 1918, Thomas was posted to the North-West Frontier to fight tribesmen hostile to India and the British Empire. Upon his return two years later the people of Bedale, his ancestral home, presented him with a plaque: today, Pauline has it hanging on her wall. He went back to his job on the railways, and the family moved to number 55. Ralph was six and his brother, George, born in 1916 and named after his uncle, was four.

By this time Ralph had been at Mexborough Adwick Road School for over a year. He was well-behaved and studious. Census records show that in the mid-1920s the family relocated to Bentley, north of Doncaster, where Ralph attended the village school before moving again, to the new Woodfield estate in the suburb of Balby. Weston Road was leafier, its semi-detached houses spaciously arranged near countryside for a twelve-year-old boy to explore. It must have felt like progress, the kind of upward social mobility that impressed the bright, ambitious Ralph. In September 1926, he was admitted to Oswin Avenue School, where the headmaster praised his enthusiasm for sport and trustworthy character. There was no uniform as such, but he did get to wear a cap and a striped tie.1

At Oswin Avenue, Ralph felt like every subject, every lesson, was an opportunity for self-advancement. Technically inclined, he also took to literature, memorizing the poetry he would later copy into his notebook. He was fond of Tennyson, Longfellow and Kipling, whose names were immortalized in streets near Weston Road – indeed, any kind of verse that spoke to the nobility of the common man, romantically masculine, dignified yet sentimental. In class, they read the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, an epic poem meditating on life and love and death. The stiffness with which Ralph faced the

A Perfect Gentleman

world did not mean he wasn’t dreamily introspective, and his love of poetry was a clue to this.

Ralph’s brother, George, cheerfully followed his father onto the railways, which was not quite what Ralph had in mind for himself. Nor was there much romance in Doncaster, no exotic landscape for expanding his sense of himself and his future. His father had fought rebels in the dusty hills of Afghanistan; presumably Ralph had wanted a taste of that, not coal and steam. He was restless – but what else could he do?

Pauline believed her grandfather had scraped together the money for Ralph to finish his education at a grammar school in Doncaster – typical that he had to be different, treated specially, she scorned. But he didn’t appear in any of the registers, suggesting that he must have left school and entered into an apprenticeship or work. By chance, I found buried in an archive a letter of reference indicating that between the ages of fourteen and seventeen he had been employed by the London North Eastern Railway as a ‘telegraph lad’, receiving and sending messages in Morse code. It was a responsible job, for which only the brightest and best employees were selected.2

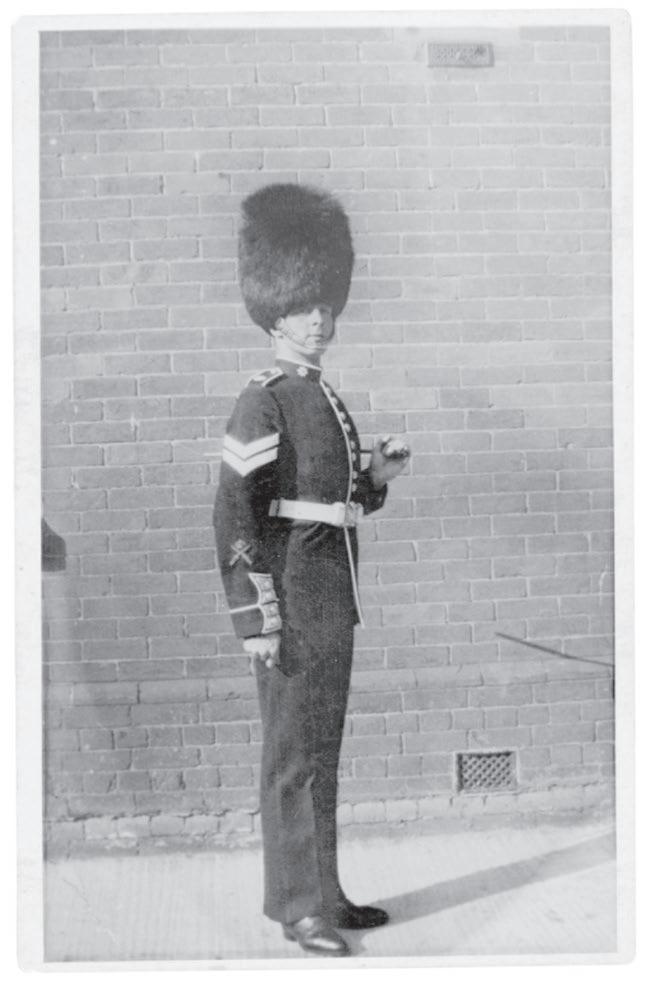

The LNER taught Ralph a trade, one that later would prove useful – but he was biding his time. In the spring of 1932, he wrote to the Sheffield depot of the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards, the oldest and arguably most illustrious regiment in the British army. ‘Nulli Secundus’ was its motto. I found a recruiting poster calling for ‘smart men’, illustrated with a guardsman in bearskin and scarlet tunic parading in front of Windsor Castle. Pasted up in railway stations and labour exchanges, it may have caught Ralph’s eye. Feeling a flush of confidence, perhaps also a sense of destiny, he handed in his notice.

On 2 May 1932, at 9.15 a.m., Ralph was called to interview, where a captain judged him to be a respectable man of sound Christian principle, eager to join the regiment. The LNER superintendent confirmed that Ralph was a decent chap who had never been in trouble with the police. Ralph’s educational attainment was graded

The Glass Mountain ‘very good’, as was his physical fitness, albeit with a high resting pulse, raised perhaps by the fear of being rejected. But all was well. A week later, on his eighteenth birthday, Ralph returned to Sheffield, where he swore an oath of allegiance and signed a contract of enlistment, now preserved in Pauline’s archive. He would serve twelve years – three in the ‘Colours’ (active service) and nine in the Reserve – starting on three shillings a day.3

At school Ralph had surely been one of the tallest boys in his class, where the growth of many was stunted by poverty and pollution. At his army medical, his height was recorded as 5 feet 11¼ inches, an inch above the minimum required for the Guards. I could see him now, walking tall, chest out, and in thick socks and army boots just reaching his own desired height of six foot. Brimful of pride, he was on his way.

Packed off to Caterham Barracks in Surrey, he trained for five months, during which time he received his Army Certificate of Education, third-class, before being transferred to Pirbright Barracks, a Victorian depot for Foot Guards. There he also studied for his second-class certificate, with classes in English, Map Reading, ‘Army and Empire’ and Mathematics, the last of these chosen over a foreign language. He learned writing and dictation, fractions and equations and the rudiments of regimental accounting. The qualification was awarded in March 1933 and, as a result, within four months he was promoted.4

To mark his becoming a lance corporal – two stripes in the Guards – a photographer visited the depot and immortalized Ralph in his parade uniform: the snap Nan gave me. Another photo in one of Pauline’s albums, from the same occasion, showed him smiling and bareheaded, wearing a white number one mess jacket. I was to see this portrait again, stuck to a forged document from another very different time in his life.

Ralph completed his three years in the Colours on 8 May 1935 and received a glowing report from his lieutenant colonel: ‘A good smart well turned out NCO. Honest, intelligent and reliable.’ Moved to the Reserve and registered by the army at the Labour Exchange in

A Perfect Gentleman

Sheffield, he considered his options. His family may have expected him to return to the railways. But Ralph was a man with a strong desire to move on.5

The Coldstream Guards offered to help find suitable occupations for ‘all men of good character returning to civil life’, which may explain how by the time he left Pirbright Ralph was already halfway to becoming a policeman. His former headmaster at Oswin Avenue, J. P. Mason, provided a second reference, which survives among Ralph’s papers, describing his former pupil as ‘a perfect gentleman, and thoroughly trustworthy’. Mason, who came from Bentley, where the Corps family had briefly lived, was a prominent local figure, so it may have been he who arranged for Ralph to join the West Riding Constabulary. Ralph acquired a taste for pulling strings, and for having others pull strings for him.

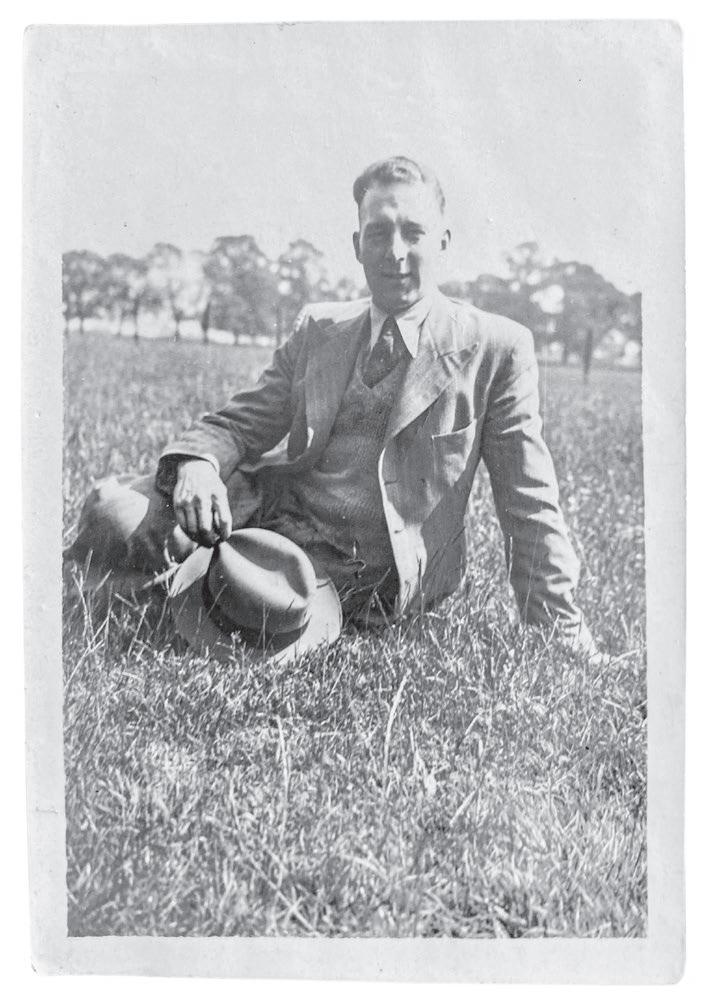

Unlike my usual research, available sources now included photographs. According to the American writer Susan Sontag, a photo is ‘something directly stencilled off the real’, not just an imitation of what the eye sees but a faithful copy of life, its captured essence. And yet, as my Italian friend Dom had warned me about the pictures he sent, a photo is also an illusion playing by its own rules. Reality is boxed in there, concealing, perhaps for ever, its surroundings and the flow of its before and after. Shorn of original truth, photos are free to deceive. When Ralph was snapped as a soldier and a policeman at this time, he was thinking and feeling something about himself, and it bothered me I might never know what it was.6

After a probationary period, during which he passed courses in First Aid and Lifesaving, Ralph became one of twenty-six new constables admitted on 15 December 1935.7 He was PC 191, the silver characters pinned to the high collar of his uniform. Cut from midnight-blue serge, and worn with a crested helmet, it perpetuated the self-respect and command of deference that Ralph had enjoyed in the army. He was posted to Knaresborough, forty miles north of the WRC station in Barnsley, nearer to the Corps ancestral home of Bedale. He was given a place to live, a stone cottage with views of the Nidd Valley, allotted a beat and issued

The Glass Mountain with a bicycle. Local newspapers from the time suggest there wasn’t much for him to deal with: some pilfering, the odd traffic accident, drunks to be locked up. He may have felt life was happening elsewhere.

The day before Ralph qualified, the Italian leader Benito Mussolini authorized the use of chemical weapons in Ethiopia, which his army had invaded in October. The League of Nations looked increasingly toothless. In March, flouting the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler commenced rearmament, and a year later sent troops to reclaim the forfeited Rhineland. Mussolini, hitherto allied to Britain and France, drew closer to Germany. With every western submission, European politics became more polarized, and the dictators’ confidence grew. Hitler and Mussolini backed the nationalists in the civil war raging in Spain, during which the bombing of civilians at Guernica in 1937 was to prove a nightmarish prophecy.

By now, Ralph had been ordered back to South Yorkshire and returned to live with his parents in Balby. There he met Florence White, who lived a short walk across the playing fields. By 1938 the Corps brothers, Ralph and George, were engaged to the White sisters, Florence and Ethel. The girls had grown up in the pit town of Rawmarsh near Rotherham, where their father, James, was a miner, their mother, Florence Mary, a housewife from Shoreditch in the East End of London. Their parents had another five children, in a tiny house on a soot-blackened hill street with shared privies and reeking pigsties. Flo worked in the Peglers factory in Doncaster making bathroom fittings, Ethel in a hardware shop.

No one seems to have thought well of my great-grandfather, James Arthur White. According to Nan – Ethel’s and Flo’s elder sister – he was an alcoholic like his own father, a Methodist lay preacher who whipped his children with a belt. Abuse was common in cheerless towns like Rawmarsh. James Arthur’s wife, my Cockney great-grandmother (who we knew as ‘Big Nanny’), detested him and waited patiently until she’d married off the last of her daughters. He lurks in the White girls’ wedding photos – yet by the time their brother married in 1940 he had gone, and his long-suffering

A Perfect Gentleman wife was a live-in housekeeper for a teacher and her elderly mother in Doncaster.

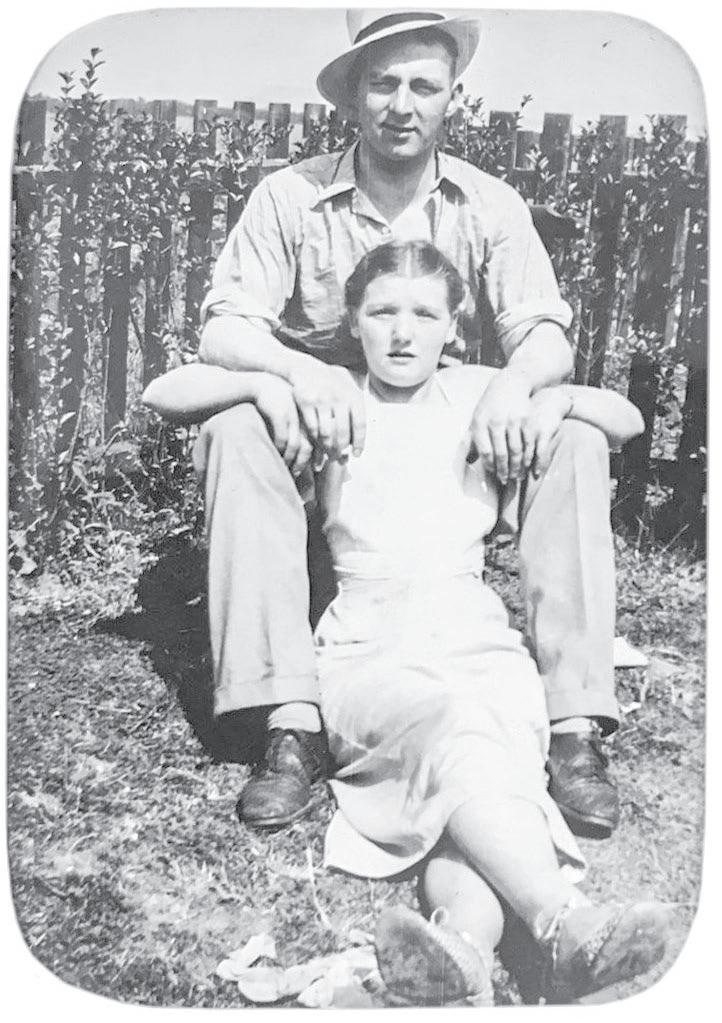

Young Flo White longed to escape this sordid world. She had already left Rawmarsh, was holding down a job at Peglers and lived in an end-of-terrace house in Balby. To progress further, she needed to marry. Ralph, the policeman from Mexborough, was not only six feet tall, give or take, used long words and had dreamy blue eyes, but came from a working-class family a shade more respectable than her own. To her, he was the perfect gentleman. She accepted his proposal, nudging her mother a step closer to leaving James Arthur. Now engaged, Ralph and Flo spent more time alone, albeit in public. Ralph owned a camera, and they took it with them on walks. It may have been Flo who snapped Ralph in his Sunday best, trying to smile, somewhere in the countryside or in a park. The photo is undated and the context is gone. But Pauline had another from this time, one that held my gaze much longer. Ralph sits in front of a picket fence, Flo on the grass between his knees, legs crossed at the

calf, his hands draped over hers. Squinting at the sun, unsmiling, the lovers stare seriously into the lens, almost as if they had an inkling of what lay ahead.

In March 1938 Hitler annexed Austria, and Mussolini was granted equal power to the king over the armed forces. In April, Britain recognized Italian control of Ethiopia, and in May, Hitler announced his designs on Czechoslovakia. These commotions were a long way from Balby, where a wedding was being planned. On 11 June, a shiny car carried Flo White in her bridal gown and veil to St John’s Church, a journey of just a couple of minutes. There, she and Ralph Corps became husband and wife. Flo’s sister Charlotte had made the journey from Gillingham, where five years earlier she had married an electrical wireman named Archibald Davis. Arch also attended the wedding, as did their little daughter Audrey, my mother.

Ralph, then twenty-four, and Flo, two years younger, set up home half an hour away in West Avenue, Wombwell. It was a tidy cul-de-sac near Ralph’s police station, housing the better grades of railwaymen and their wives – described as ‘unpaid domestics’ in the