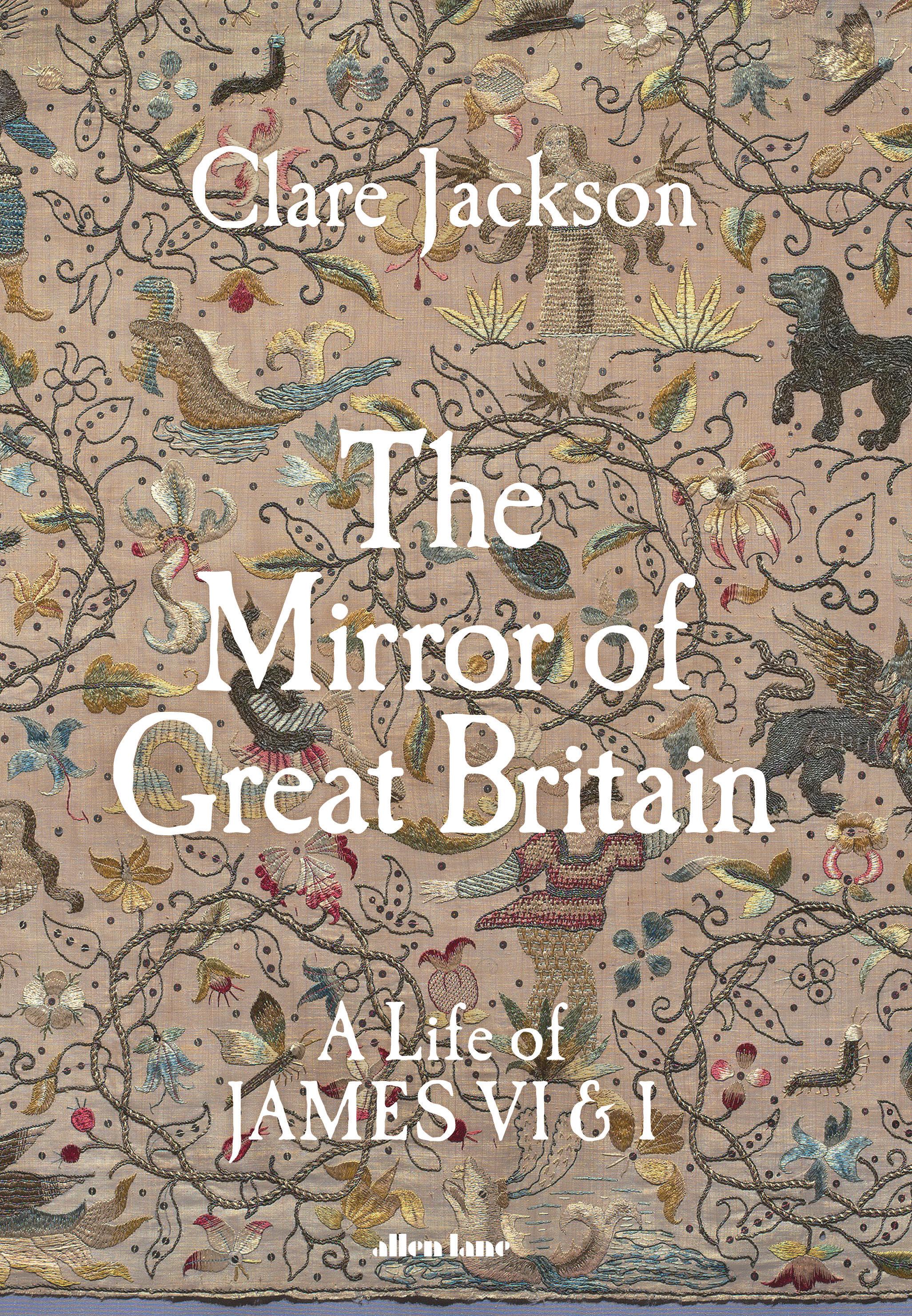

clare jackson

The Mirror of Great Britain

A Life of James VI & I

an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025

Copyright © Clare Jackson, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10.2/13.87pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–61127–2

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

List of Illustrations

Photographic acknowledgements are shown in italics.

1. King James VI as a boy, 1574, by Rowland Lockey. Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire. National Trust Photographic Library / Bridgeman Images.

2. Mary, Queen of Scots and her first husband, François II of France. Miniature by François Clouet, from the Hours of Catherine de Medici, c. 1573. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, NAL 82, folio 154 verso.

3. Armoured half-length portrait of James VI on a £20 (Scots) coin, 1576. Stacks Bowers Auctioneers.

4. Scene of James I at the tomb of his father, Henry Lord Darnley by Livinus Voghelarius, 1567. The Royal Collection Trust. Copyright © His Majesty King Charles III, 2025/Bridgeman Images.

5. James’s draft of the opening stanzas of his poem ‘Ane metaphoricall invention of a tragedie called Phœnix’, later published in The Essays of a Prentice, in the Divine Art of Poesie, 1584. The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Bodl. 165 ff 36r.

6. Urn-shaped acrostic, spelling the name of Esmé Stewart, Duke of Lennox, from The Essays of a Prentice, in the Divine Art of Poesie, 1584. Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 14373.

7. James VI gold ‘hat-piece’ coin, 1592. Heritage Auctions/HA.com.

8. Mary, Queen of Scots, and James VI, double portrait by an unknown artist, 1583. Blair Castle, Blair Atholl, Pitlochry. Reproduced by permission of the Atholl Estates.

9. King James VI, engraving from the Edinburgh edition of John Johnston, Inscriptiones Historicae Regum Scotorum, 1602.

10. King James VI, engraving from the Amsterdam edition of John Johnston, Inscriptiones Historicae Regum Scotorum, 1602.

11. The Coronation of King James I at Westminster Abbey, handcoloured copy of an original engraving by Abraham Hogenberg, 1603. Cabinet des estampes, Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. Raffaello Bencini/ Bridgeman Images.

12. Gilt brass and enamel table clock made by David Ramsay, 1610–15 (and later seventeenth-century alterations), with detail of the engraved base of the clock. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Copyright © V&A.

13. Stone-relief portrait of James, possibly carved by Maximilian Colt, 1608. Council Chamber of the King’s House, Tower of London. Copyright © Historic Royal Palaces.

14. James wearing the ‘Mirror of Great Britain’ jewel, portrait by John de Critz, after 1603. National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh. Bequeathed by Sir James Naesmyth 1897. National Galleries of Scotland.

15. Queen Anna, portrait by an anonymous English artist, early 1600s. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Luisa Ricciarini/Bridgeman Images.

16. Henry, Prince of Wales, large cabinet-miniature by Nicolas Hilliard, c.1610. National Portrait Gallery, London. History and Art Collection/ Alamy.

17. Charles, Prince of Wales, portrait by Daniel Mytens, c.1623. Parham House, West Sussex. Nick McCann/Bridgeman Images.

18. King Frederick V and Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia Riding near The Hague, watercolour by Adriaen van de Venne, 1620–26. British Museum, London. © Trustees of the British Museum.

19. James I, statue by John Clark, 1620. Tower of the Five Orders of Architecture, Old Schools Quadrangle, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Peter Wheeler/Alamy.

20. Dr John King preaching at Old St Paul’s before James I, painting by John Gipkyn, 1616. Society of Antiquaries of London. Bridgeman Images.

21. An Englishman smoking tobacco, illustration from Anthony Chute, Tobacco, 1595.

22. Pocahontas, illustration from Simon van der Passe, Baziliωlogia. A Book of Kings, 1618.

23. An edition of the ‘King James Version’ of the Bible, published in 1620 and brought to North America by John Alden. Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Massachusetts.

24. Undated letter from George Villiers, later Duke of Buckingham, to James. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Adv MS 33.1.7 vol 22 no 79.

25. James I, heart-shaped portrait miniature attributed to Lawrence Hilliard, undated. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

26. Letter from James to George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham (December 1623 or 1624?). The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS Tanner 72, fol. 14v.

27. George Villers, Marquis of Buckingham, and his wife, Katherine Manners, as ‘Venus and Adonis’, portrait by Anthony van Dyck, before 1621. Het Noordbrabants Museum, ‘s-Hertogenbosch Photo: Christie’s/Bridgeman Images.

28. King James I in garter robes, portrait Paul van Somer, 1620. The Royal Collection Trust. © His Majesty King Charles III, 2025/Bridgeman Images.

MAPS

List of Maps and Family Trees

Scotland xii

England and Wales xiii

FAMILY TREES

Descendants of Henry VII xv

The Stuarts xvi–xvii

Scotland

Isle ofLewis

Inverness

Aberdeen

SCOTLAND

Dundee

Lochleven Castle

Stirling

Dunfermline

Dumbarton

Langside

Linlithgow

Perth Musselburgh

Leith N

St Andrews

Burntisland

Glasgow Falkland Edinburgh

Dalkeith

Dunbar

Berwick-upon-Tweed

Carlisle

50 kms

miles

England and Wales

Berwick-on-Tweed

Carlisle

Newcastle

York

ENGLAND

Woodstock

Salisbury

Apethorpe

Fotheringhay

Peterborough

Huntingdon

Newmarket

Cambridge

Royston

Oxford

Richmond

Windsor

Hampton Court

Winchester

Greenwich

Eltham

Theobalds Palace 0 100 miles 0 100 kms

Dover

DESCENDANTS OF HENRY VII

Henry VII of England 1457–1509, reigned as King 1485–1509

m

Elizabeth of York 1466–1503

James IV of Scotland 1473–1513, reigned as King 1488–1513

Margaret 1489–1541 m

James V of Scotland 1512–42, reigned as King 1513–42

m. 1

m 2

Madeleine of Valois 1520–37 Mary of Guise 1515–60

Mary, Queen of Scots 1542–87, reigned 1542–67

m 1

François II of France 1544–60, reigned as King 1559–60

m 2

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley 1545/6–67

m. 3

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell c. 1534/5–78

Arthur, Prince of Wales 1486–1502

Mary I of England 1516–58, reigned as Queen 1553–8

m

Philip II, of Spain 1527–98, reigned as King of Spain 1556–98

JAMES VI OF SCOTLAND

AND I OF ENGLAND 1566–1625

m Catherine of Aragon 1485–1536

m 1

Mary 1496–1533 m 1 m 2

Louis XII King of France 1462–1515, reigned as King 1498–1515

Charles Brandon, Duke of Su olk c 1484–1545

Elizabeth I of England 1533–1603, reigned as Queen 1558–1603

Edward VI of England 1537–53, reigned as King under a regency council 1547–53

Henry VIII of England 1491–1547, reigned as King 1509–47

m 2 m 3

Anne Boleyn c. 1501–36

Jane Seymour 1508/9–37

m 4

Anne of Cleves 1515–57

m 5

m 6

Catherine Howard c. 1518/24–42

Catherine Parr 1512–48

Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales 1594–1612

Frederick Henry 1614–29

Elisabeth 1618–80

Karl Ludwig, 1618–80 Elector Palatine 1648–80

Rupert, Prince Palatine, Duke of Cumberland 1619–82

THE STUARTS

James IV of Scotland 1473–1513, reigned as King 1488–1513

m

Margaret Tudor 1489–1541

James V of Scotland 1512–42, reigned as King 1513–42

m 1

m 2

Madeleine of Valois 1520–37

Mary of Guise 1515–60

Mary, Queen of Scots 1542–87, reigned 1542–67

m. 1

François II of France 1544–60, reigned 1559–60

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley 1545/6–67

James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell c. 1534/5–78 m 2 m. 3

JAMES VI & I 1566–1625, REIGNED AS JAMES VI OF SCOTLAND 1567–1625 AND JAMES I OF ENGLAND 1603–1625

ANNA OF DENMARK 1574–1619 m.

Elizabeth Stuart, Electress Palatine, briefly Queen of Bohemia 1596–1662

Louise Hollandine 1622–1709

Maurice, Prince Palatine of the Rhine 1621–52

Edward, Count Palatine of Simmern 1625–63

m

Frederick V, Elector Palatine, briefly King of Bohemia 1596–1632

Henrietta Maria 1626–51

Philip Frederick, Prince Palatine 1627–50

Gustavus Adolphus, Prince Palatine 1632–41

Margaret 1598–1600

Sophia, Electress of Hanover, Heiress of Great Britain 1630–1714

2 others (died in infancy)

Ernst Augustus, Elector of Hanover 1629–98 m

George Louis 1660–1727, reigned as George I of Great Britain 1714–27

Charles II 1630–85, reigned as King of Scotland 1649–85, King of England and Ireland 1660–85

m.

Catherine of Braganza 1638–1705

Henrietta Maria 1609–69 m Charles I 1600–1649, reigned as King of England, Scotland and Ireland 1625–49

Robert, Duke of Kintyre and Lorne b. and d. 1602

James VII & II 1633–1701, reigned as King of England, Scotland and Ireland 1685–8

m 1

Mary 1605–7

Anne Hyde 1637–71

Sophia b. and d. 1606

Henry, Duke of Gloucester 1640–60

Henrietta Anne, Duchess of Orléans 1644–70

Elizabeth 1635–50

Mary, Princess of Orange 1631–60

m m

William II, Prince of Orange 1626–50

William III of Orange 1650–1702, reigned as King of England, Scotland and Ireland 1689–1702

Anne 1665–1714, reigned as Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1702–7 and as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, 1707–14

Mary II 1662–94, reigned as Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland 1689–94

m 2 m

George, Prince of Denmark 1653–1708

Mary of Modena 1658–1718

James Francis Edward Stuart, ‘The Old Pretender’ 1688–1766

Author’s Note

Dates in the text appear in ‘Old Style’ as per the Julian calendar, which was observed in the British Isles until 1752 and, until 1700, was ten days behind the Gregorian calendar that had been adopted in the majority of Continental European countries after its introduction by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. Having been born in 1566, James objected to English peers and MP s in 1610 that adoption of the Gregorian calendar had sown confusion; indeed, ‘I can never tell my own age; for now is my birthday removed by the space of ten days nearer me than it was before the change’. For convenience, each new year is taken to begin on 1 January, although, in England until 1752, and in Scotland until 1600, it was usual to deem each new year as starting on 25 March at the Feast of the Annunciation.

Aside from the sixth chapter considering James’s interest in verse composition, the spelling and punctuation in quotations and publication titles have mostly been modernized. During the seventeenth century, the official name of the Dutch Republic was the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

A Mirrored Life

‘Two snowballs put together, make one the greater: two houses joined, make one the larger: two castle walls made in one, makes one as thick and strong as both.’1 Thus King James I of England exhorted sceptical members of the English Houses of Parliament in March 1607 to admit the practical benefits that would accrue by creating a united British kingdom. When united, the two formerly warring countries of England and Scotland would become a prosperous, powerful, Protestant state, with potential foreign invaders deterred by the sheer strength of Fortress Britain. Four years earlier, as King James VI of Scotland, he had succeeded to the English Crown on Elizabeth I’s death in March 1603 and become the first monarch to rule both Scotland and England.

On his accession, James had assumed that closer union would inevitably follow with a single British state formed from his two separate kingdoms of Scotland and England. Unus Rex, unus Grex et una Lex : one king, one people and one law. But James’s confidence had been misplaced; as he later conceded, ‘I knew my own end, but not others’ fears.’ Although union commissioners held bilateral negotiations and produced a limited set of initial recommendations in 1604, the king was dismayed to observe, by March 1607, ‘many crossings, long disputations, strange questions and nothing done’.2 Only three months before James spoke in Parliament, the royal court had watched the premiere of William Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear, first performed at Whitehall on 26 December 1606. After having Lear call for a map of ancient Britain in order to divide his territory among his three daughters, Goneril, Regan and Cordelia, the play concluded in cataclysm. Rather than seeing father and daughters reunited and their lands preserved – as in the sixteenth-century drama King Leir – Shakespeare’s reworking

of Leir ’s plot ended with the dying Lear cradling a strangled Cordelia and crying ‘Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones.’ The widowed, childless Duke of Albany is left to contemplate the resulting destruction of Lear’s family and kingdom.3

Although King Lear ’s dramatic dénouement was quickly amended to have Lear die in the (mistaken) belief that Cordelia still lived, the state of ‘Great’ Britain – as distinct from the smaller ‘Britanny’ in France – would remain a rhetorical aspiration during James’s reign. Ambitious constitutional ambitions proved abortive: a bitter blow for a king who had hoped that his accession would effect ‘an eternal agreement and reconciliation of many long bloody wars that have been between these two ancient kingdoms’.4 The lessons of Shakespeare’s King Lear only reinforced James’s own convictions. In his advice manual entitled Basilicon Doron (‘The Royal Gift’) first published in 1599, James had counselled his eldest son and heir, Prince Henry, that, should he succeed to the triple Crowns of Scotland, England and Ireland, he must bequeath his territorial possessions intact, ‘otherwise by dividing your kingdoms, ye shall leave the seed of division and discord among your posterity’.5

Half a century after James succeeded as English king, an AngloScottish union ordinance was issued by the Cromwellian Protectorate in 1654 following the military subjugation of Scotland and the monarchy’s abolition in England. The ordinance’s provisions were, however, short-lived and ended with the collapse of the Protectorate and restoration of Stuart multiple monarchy in 1660 under James’s grandson, Charles II . James’s ambitions were partially realized under his greatgranddaughter Queen Anne in 1707, when the Anglo-Scottish Treaty of Union created a new British state. A somewhat hybrid arrangement, the new state’s unitary features included a single Westminster legislature, common currency and a single economic market, alongside more pluralistic aspects, notably the retention of separate national churches, legal systems and educational provision in Scotland and England. Having acclaimed the territorial conjunction of the two countries ‘in one island, compassed with one sea, and of itself by nature so indivisible’ as to render its internal borders redundant, James’s unionist vision had notably been confined to mainland Britain.6 In 1801, however, the Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland expanded the political state to include the island of Ireland. More than a century later, the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) provided for the creation of the Irish Free State – later the

Republic of Ireland – with six northern counties in Ulster remaining part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. None of these geopolitical outcomes was quite what James had envisaged.

Becoming English king in 1603, James was no neophyte sovereign. He had been crowned King James VI of Scotland on 24 July 1567, at the age of only thirteen months, after the deposition of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. With political power initially vested in regents, James declared his intention to rule Scotland in his own name in 1578, aged eleven, although, in practice, his adult rule only started in the mid-1580s. The peaceful nature of James’s accession to the English Crown in 1603 surprised many who had feared that, on the demise of the childless Virgin Queen, England would be plunged into a protracted and bloody war of succession between rival Protestant and Catholic claimants with French and Spanish interference. A week after Elizabeth’s death, James wrote to his brother-in-law, Christian IV of Denmark, to ‘acknowledge that what we have always wished has come true’.7 A momentous juncture in British history, James’s uncontested accession as English king appeared a providential fulfilment of ancient predictions, as panegyrists hailed a King Arthur redivivus who would gloriously fulfil Merlin’s prophecy by reuniting Britain under his rule.

But by the time James again addressed MP s and peers at Westminster in March 1610, he felt himself ‘now an old king’ who, in addition to his decades ruling Scotland, had been in England for ‘seven years [which] is a great time for a king’s experience in government’.8 On the day after his fiftieth birthday in June 1616, he summoned his English commonlaw judges to the Star Chamber at Westminster and recalled that, when he had arrived in London in 1603, ‘I was an old king, past middle age, and practised in government ever since I was twelve years old.’9 When James died at Theobalds Palace in Hertfordshire in March 1625, he had ruled England for twenty-two years. James was the only one of thirteen English monarchs between Henry VII and George I who lived to see a grandchild born and also the first King of Scotland to die peacefully of natural causes since Robert I (‘the Bruce’) in 1329.10 His tenure of the Scottish throne for nearly fifty-eight years has since been surpassed only by Victoria and Elizabeth II .

Four centuries after King James VI & I’s demise, his enlarged British snowball nevertheless looks vulnerable. Although the flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is nicknamed

after James – the ‘Union Jack’ deriving from the Latin ‘Jacobus ’ – the polity faces an uncertain future. In The Break-up of Britain (1977), first published half a century ago, Tom Nairn diagnosed the multinational state of the United Kingdom as being in terminal atrophy, beset by imperial decline, an archaic constitution, and the rise of popular nationalisms in Scotland, Wales and Ireland. Dismissed by the political mainstream as pessimistic polemic, Nairn’s apprehensions regarding the frailty of Britain’s unreformed, asymmetrical polity now appear prescient. Two years after Nairn’s book appeared, two referenda held in Scotland and Wales in 1979 failed to garner sufficient support for devolved deliberative assemblies to be established.11 The dynamics of British territorial politics then shifted significantly when devolved administrations were created in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast in the 1990s. Within Scotland, a referendum on independence in 2014 attracted a turnout of 84 per cent of the registered electorate and resulted in a majority of 55 per cent in favour of adhering to the status quo and retaining the Anglo-Scottish union.

Two years after the Scottish independence vote, a UK -wide referendum on membership of the European Union in 2016 generated a narrow majority in favour of altering the status quo, prompting negotiations that resulted in the UK ’s withdrawal from the European Union in 2020. The divisive and disruptive impact of ‘Brexit’ proved particularly acute in Northern Ireland, where commitments to avoid reintroducing either a ‘hard’ physical border within the island of Ireland or a customs border in the Irish Sea seemed ostensibly incompatible with simultaneously ensuring Britain’s exclusion from the European Union’s Single Market and Customs Union. Looking ahead, Northern Ireland’s changing demographic dynamics have been interpreted as likely to yield a majority in favour of Irish reunification in a future referendum vote.12

In early modern Europe, dynastic agglomerates, similar to that inherited by the Stuart dynasty in 1603, were not uncommon. Today, Charles III is the head of state in fourteen sovereign countries, albeit reflecting Britain’s colonial, rather than its dynastic, history. Referring to Scotland when addressing English peers and MP s in 1607, James put it simply: ‘I was born there, and sworn here, and now reign over both.’13 Inevitably, the reality was more complex as his accession as English king entailed absentee rule in Edinburgh, new forms of delegated authority, an asymmetrical balance of power, confessional tensions, overlapping and

competing legal codes and a new ‘British’ cultural lexicon. Constitutionally, however, the mainland polity over which James ruled between 1603 and 1625 offers a plausible approximation of the situation likely to arise were Scotland once again to become an independent state: the same monarch, two independent states, two parliaments and separate national churches, currencies, economic arrangements and legal systems. Campaigning for independence in 2013, as Scotland’s then First Minister, Alex Salmond reminded a public meeting in Campbeltown that ‘Scotland was an independent nation for more than 100 years after the first union of the crowns. It is a phrase with a deep historical resonance in Scotland.’14

In 1603, James’s wish to enact closer Anglo-Scottish union was a logical desire to convert the advantages of dynastic succession into territorial consolidation. Without the creation of a single British state, the link between the two formerly warring states of Scotland and England remained precarious, vested only in the persons of James and his three surviving children, Henry, Elizabeth and Charles. Following Prince Henry’s unexpected death from typhoid fever in 1612, the dynastic link shrank further, leaving Princess Elizabeth – later Palatine Electress in Heidelberg with a brief tenure as Bohemian queen – and her younger brother, who succeeded James as King Charles I in 1625, but whose tenure of the British crowns led to civil war and his public execution in January 1649 by order of a radically reduced ‘Rump’ of the English Parliament.

Addressing the English Parliament in 1607, James remained mindful of the long history of acrimonious Anglo-Scottish relations and perennial fears of hostile incursion. As recently as the 1540s, England’s failed attempt to conquer its northern neighbour had resulted in the deaths of over 10,000 Scots, the torching of numerous Scottish towns and the draining of both the English and Scots Treasuries. Those living in the traditionally lawless Border regions had, for generations, suffered endemic violence and been plagued by ‘bloodshed, oppressions, complaints and outcries’, standing in bleak contrast to the halcyon new world in which ‘they now live every man peaceably under his own figtree’. James warned that, ‘if after all this, there shall be a scissure [rift], what inconvenience will follow, judge you.’15 Styling himself ‘King of Great Britain’, he sought – in parliamentary speeches and proclamations, alongside designs for a common coinage and new flag, and sponsorship of dramatic masques replete with nuptial rhetoric – to invest the idea of

Britishness with tangible psychological heft. Not without irony, it was the Scots nationalist republican, Tom Nairn, whose survey of Britain’s historical evolution as a multinational state convinced him that James VI & I ‘deserves greater recognition’. As Nairn acknowledged in 1997, James ‘not only invented “Great Britain” but tried extraordinarily hard to make it work’.16

In a full-length portrait painted shortly after James’s accession to the English throne, the king was depicted wearing a prominent hat jewel called the ‘Mirror of Great Britain’ (see Plate 14). Comprising three large diamonds and a ruby, the ‘Mirror’ offered opulent symbolic endorsement of James’s vision of a united Britain, having been constituted from jewels in the English and Scottish royal collections.17 More usually, however, mirrors reflect present realities, albeit with the capacity also to distort and deceive. Reappraising King James VI & I – as this book’s title implies – can sometimes feel like entering a fairground hall of mirrors. To his subjects, especially his English ones, James often confounded popular expectations and his reputation has likewise disconcerted later generations. Mirrors, moreover, supplied James with one of his favourite verbal images. In 1626, the preacher and poet John Donne dedicated a printed sermon to the king’s son and successor, Charles I, recalling that likening a king to a mirror was ‘a metaphor in which your Majesty’s blessed father seemed to delight’. As Donne elaborated, ‘in the name of a mirror, a lookingglass, he sometimes presented himself, in his public declarations and speeches, to his people.’18

Addressing both Houses of the English Parliament in March 1607, for example, James sought to correct misconceptions regarding royal plans for Anglo-Scottish union and, ‘with the old philosophers’, had insisted ‘I would heartily wish my breast were a transparent glass for you all to see through, that you might look into my heart, and then would you be satisfied of my meaning.’19 Echoing the wish of Momus, Greek god of satire – that all humans might have a glass in their breasts to reveal their true souls – James invoked the same conceit in all subsequent English parliaments. In March 1610, he began a speech to peers and MPs ‘with a great and a rare present, which is a fair and a crystal mirror . . . as through the transparentness thereof, you may see the heart of your

king’. Following an address that must have lasted for the best part of an hour, the king concluded by warning that there were ‘three ways ye may wrong a mirror’. His listeners might regard ‘my mirror with a false light’ and misunderstand his words or ‘soil it with a foul breath and unclean hands’, thereby conferring ‘an ill meaning’ on his intentions. Most serious of all, however, would be to disdain royal authority so much as to ‘let it fall or break (for glass is brittle)’.20

Opening his next English Parliament in April 1614, James again conceived of his wishes as ‘a mirror which is clear and unpolluted’, hoping that his request for financial subsidy would be well received.21 In January 1621, he likewise offered peers and MP s ‘a true mirror of my mind and free thoughts of my heart’, despite earlier occasions when, ‘through a spice of envy’, critics had spitefully attacked his words and turned them ‘like spittle against the wind upon mine own face and contrary to my expectation’.22 Finally, when opening what would be his last English Parliament in February 1624, the same metaphor was deployed to a different end when the king reminded MP s of their vital responsibilities to their constituents. James exhorted members of the House of Commons, ‘be ye true glasses and mirrors of their faces, and be sure you yield true reflections and representations, as ye ought to do.’23

Underpinning the extensive speculum principiis – or ‘mirror for princes’ – genre of prescriptive literature offering advice to medieval and early modern rulers, mirrors supplied a metaphorical means of inculcating exemplarity and encouraging emulation. Between 1500 and 1700, four hundred works were published in England with titles including a reference to a mirror, a glass or a looking-glass.24 In Basilicon Doron (1599), James urged his heir to ‘let your own life be a lawbook and a mirror to your people.’ By the former, ‘they may read the practice of their own laws’ and, by the latter, ‘they may see, by your image, what life they should lead.’25 On James’s accession to the English throne four years later, the poet Alexander Craig combined the same metaphor with reference to the monarch’s literary publications to warn that ‘Kings be the glass, the very school, the book / Wherein private men do learn, and read, and look.’26 In private, James wrote an anguished, if simultaneously excoriating, missive to the courtier Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, in early 1615, citing ‘things directly acted or spoken to myself’ in the hope ‘that ye may make good use of this little mirror of yourself’ which ‘lays plainly and honestly before you both your best and worst parts’.27

In specifying ‘a fair and a crystal mirror’, James was also offering MP s – metaphorically at least – the very best in vitreous technology. Imported into England from Continental Europe since the mid-1570s, crystal mirrors were not produced domestically until 1624.28 Superior to their steel predecessors, crystal mirrors did not require regular polishing and presented images that were ‘crystal clear’. Indeed, when Sir Francis Bacon (later Lord Chancellor) outlined James’s preferred model of Anglo-Scottish union to MP s in April 1604, he deemed it too ‘dangerous’ a subject to paraphrase. Having asked the king to confirm his wishes in writing, Bacon read aloud the instructions as a ‘piece of crystal, to deliver him from mistaking’.29

Using the metaphor of a crystal mirror, James hoped to imply maximal transparency and representational accuracy in articulating his inner thoughts, but ‘definitionally, a reflection is never what it seems to be’.30 Plane mirrors laterally invert images, while concave and convex mirrors magnify and diminish. In an era of increasing visual uncertainty, moreover, it could no longer be axiomatically assumed that, when individuals viewed an external object, everyone looking at it would perceive the same identical image, which would then pass unmediated from their eyes to their brains, and thereafter to their memories. Rather, individual vision was affected by physiological and neurological conditions as well as by the imagination’s dispositional character. In 1612, Henry Peacham published an anthology of emblems inspired by Basilicon Doron, with each emblem matched to a quotation from James’s treatise. But in a dedicatory poem to Prince Henry, the painter and herald William Segar warned of the limitless possibilities of ways in which different readers might interpret Peacham’s images and the king’s words:

All eyes behold, and yet not all alike, Effects, and defects, both are in the eye, As when an object ‘gainst the eye doth strike, The imagination straightaway doth imply Shapes, or what else the object doth present, Weaker or stronger, as the sight is bent.31

While the recent invention of microscopes and telescopes was dramatically expanding the range and scale of what could be perceived, simultaneous developments in artistic perspective were encouraging

increasingly sophisticated forms of optical illusion such as anamorphosis and trompe l’oeil. In the religious sphere, the Protestant Reformation had provoked intense debates about visual delusion, with Catholic paintings and statues of divine entities denounced as ungodly while alleged miracles were dismissed as misreported or visually fraudulent. Undermining all forms of religion were, moreover, diabolic forces that were widely blamed for derailing cognitive processes by which images entered the eye or brain. In his published dialogue, Daemonologie (1597), James acknowledged the Devil’s skill in deceiving the human senses to assume supernatural powers. Given the popularity of card tricks and dice games, it was ‘no wonder, that the Devil may delude our senses, since we see by common proof, that simple jugglers will make a hundred things seem both to our eyes and ears otherwise than they are.’32

It was indeed often difficult to believe what one saw at the Jacobean court. At Whitehall, the Dutch scientist Cornelis Drebbel staged elaborate optical displays using a camera obscura to ‘present myself as a king, decorated with diamonds and all kinds of precious stones, and then in a moment transform myself into a beggar, all my clothing in rags, while in actual fact I am wearing only one set of clothes’. Drebbel could likewise ‘change myself into whatever creature I desire, now into a lion, then into a bear, now into a horse, now into a cow, a sheep, into a calf, into a pig’.33 In 1612, Drebbel informed James that he was devising a telescope to enable him to read private letters from a distance of seven miles and to observe actions occurring eight or nine miles away as easily as if they were in his royal bedchamber. Drebbel successfully achieved the world’s first submarine journey on the River Thames, with the king among several thousand spectators who watched for three hours in 1620, with mounting anxiety, before Drebbel’s leather vessel resurfaced, at a considerable distance from its point of descent. So impressed was James that he reportedly demanded that Drebbel immediately expand production from one prototype, able to carry nine passengers, to one hundred smaller submarines for solo individuals.34

The theatricality of optical illusion was also exploited on the Shakespearean stage where catoptrics – the branch of optics related to reflection – readily veered into catoptromancy, or divination by mirrors. In 1606, for instance, James is likely to have watched one of the first

performances of Macbeth in which the eponymous king consulted the ‘weird sisters’ in an attempt to secure his rule. Presented with a ‘show of kings’, Macbeth objected:

Another yet? A seventh? I’ll see no more. And yet the eighth appears who bears a glass Which shows me many more, and some I see That twofold balls and treble sceptres carry.35

In this classic ‘mirroring moment’, the ‘glass’ conjured for Macbeth images of an endless succession of future rulers, while also offering James, if he was in the audience, the opportunity to recognize himself in that descent, as ruler of Scotland and England, bearing the treble sceptred crowns of Scotland, England and Ireland.

The pre-eminent form of entertainment at the Jacobean court remained, however, glittering masques which created elaborate fictional universes and orbited around James’s presiding presence as the ‘Sun King’. Combining complex allegory, dialogue, music and dance, masques dazzled their elite audiences with intricate stage effects, such as those enabling performers dressed as Olympian gods to descend to the stage from hydraulic ‘clouds’. Eventually writing over twenty scripts for court masques, Ben Jonson panegyrically acclaimed the cultural transcendence of James’s court as a place in which ‘the whole kingdom dresses itself, and is ambitious to use thee as her glass.’36 Dazzling visual spectacles dramatically confirmed the majesty of royal power which, as the barrister Edward Forset marvelled in 1606, ‘surmounts the person’ of a monarch and acts ‘like a brittle glass all enlightened with the glorious blaze of the sun’, despite their physical body being ‘as infirm and full of imperfections as others’.37

In reappraising James VI & I, The Mirror of Great Britain is as interested in the fragile and vulnerable dimensions of this king’s life as in its more brilliantly gilded or sharply jagged aspects. In religious meditations published in 1624 – the year before James’s death – John Donne acknowledged that divinely ordained kings occupied ‘the highest ground’ on earth and were its ‘eminentest hills’ – but still remained mortal. Although monarchs offered models for emulation, ‘a glass is not the less brittle, because a king’s face is represented in it; nor a king the less brittle, because God is represented in him.’38

Four centuries after King James’s death, The Mirror of Great Britain supplies its own reflections on this remarkable king. Although it follows a broad chronological arc, its chapters are not narrative instalments, but thematic reflections on different aspects of James’s life and writings. Where possible, this book brings together both the Scottish and English experiences of a king in whom, too often, the interest of historians of Scotland tends to wane after the royal court relocated to London, which, in turn, is often the cue for historians of England to interest themselves in James only as Elizabeth I’s successor. While acknowledging that James’s accession to the English throne was a momentous juncture in British history, events in 1603 have, too often, seemingly presented an insuperable historiographical hurdle that has encouraged biographers to produce serial volumes, restricting their focus to specific periods of James’s life and reigns.39 This book is, rather, a single-volume life of James VI and I. But since its structure is more thematic than chronological, a brief conspectus of James’s life is helpful now, both to orientate readers unfamiliar with this era in British history and to serve as a reference point for events discussed later.

Born in Edinburgh Castle on 19 June 1566, James was the only child of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, and her second husband, Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, whom Mary had married after the death of her first husband, François II of France. When James was eight months old, Darnley was murdered by members of a faction close to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, who shortly afterwards married James’s mother. With Mary suspected of complicity in Darnley’s murder, a group of ‘Confederate Lords’ took custody of the queen and obliged her to abdicate in favour of James, who was crowned King James VI of Scotland in the parish church of Stirling in July 1567, aged thirteen months. A six-year civil war ensued between a ‘King’s party’, which promoted Protestantism and pro-English amity, while striving to uphold the infant king’s fledgling authority, and a ‘Queen’s party’, which rejected Mary’s deposition as illegal. Mary herself fled to England in May 1568, where she remained under permanent house arrest, suspected of fomenting Catholic rebellion and seeking to usurp Elizabeth I, her first cousin once removed. In Scotland, a series of regents governed the country during James’s minority, with the king assuming greater personal power from 1578 onwards, aged twelve. The arrival in Scotland of James’s French cousin

Esmé Stuart, later Duke of Lennox, dismayed pro-English factions at court and, in August 1582, William Ruthven, Earl of Gowrie, seized the teenage king’s person in the ‘Ruthven Raid’ and retained close control over him until James escaped ten months later. Thereafter ruling Scotland as an adult king, James agreed an Anglo-Scottish diplomatic alliance in 1585 that survived the trial and conviction for treason of his mother, Queen Mary, who was executed in February 1587 at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire, on Elizabeth I’s orders. In 1589, James married the Danish Oldenburg princess Anna, with whom he had seven children: Henry (1594–1612), Elizabeth (1596–1662), Margaret (1598–1600), Charles (1600–1649), Robert (born and died 1602), Mary (1605–7) and Sophia (born and died 1606).

As King of Scotland, James faced serial challenges to royal authority from ministers in the Established Church of Scotland, who preferred Presbyterian models of church government whereby ecclesiastical authority was entrusted to representative assemblies of church elders, rather than Episcopalian models where power lay with bishops under the monarch. During the 1590s, the king also survived sporadic violent attacks on his person by refractory nobles, most prominently his older first cousin Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell, whose title derived from his late, disgraced uncle, who had married James’s mother. In August 1600, another physical altercation involving the king – later dubbed the ‘Gowrie conspiracy’ – saw the death of Alexander, Master of Ruthven (whose father had led the ‘Ruthven Raid’ two decades earlier), while James celebrated his providential escape from another attempt at abduction or assassination.

The extinction of all lines of descent from the Tudor King Henry VIII of England and his six wives meant that James’s status as a greatgrandson of Henry’s elder sister, Margaret Tudor, underpinned his genealogical claim to succeed Elizabeth I and he became England’s first Stuart monarch in March 1603. In the first joint coronation in England since that of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon in 1509, James and Anna were crowned at Westminster Abbey on ‘St James’s Day’: 25 July 1603. The new king quickly turned his attention to addressing intra-Protestant tensions within the Church of England by convening the ‘Hampton Court Conference’ in January 1604 and, the following year, survived a major Catholic conspiracy when the ‘Gunpowder Plot’ was thwarted in November 1605. In a move aimed

at isolating a dangerously radicalized minority of English Catholics from the loyalist majority, James devised an ‘Oath of Allegiance’ to be levied on all indicted or suspected recusants, but its denunciation of key tenets of Catholic doctrine provoked attacks from opponents across Continental Europe.

In 1609, James also oversaw the ambitious ‘Ulster plantation’ project, with around 3.8 million statute acres of land in the north of Ireland reassigned to new owners following the ‘Flight of the Earls’, when two prominent Gaelic Irish chiefs unexpectedly left Ireland for the Continent. At Whitehall, James’s retention of Elizabeth I’s former Principal Secretary, Sir Robert Cecil, later Earl of Salisbury, secured administrative stability, but not crown solvency. By 1618, the royal debt had risen to unprecedented peacetime levels, approaching £900,000 sterling (or approximately £188 billion in today’s values, taking account of inflation).

Although James’s accession saw the first functioning royal family at the English court for more than half a century, Stuart dynastic confidence was shaken when the king’s eldest son and heir, Prince Henry, died from typhoid fever, aged eighteen, in November 1612. The following spring, Henry’s sister Princess Elizabeth married the German Palatine Elector, Frederick V, and left England to reside in Heidelberg. But by 1618, escalating confessional tensions in central Europe led to the outbreak of what was later known as the ‘Thirty Years War’. James’s family, moreover, became directly involved in hostilities when Frederick V accepted an offer to become King of Bohemia, following a revolt by Protestant members of the Bohemian Estates who had rejected their Catholic king-elect.

In 1619, Queen Anna died, aged forty-four, from dropsy and consumption. Having enjoyed close relations with a succession of male favourites throughout his life, James thereafter became increasingly reliant – personally and politically – on George Villiers, later Duke of Buckingham. As a self-styled ‘rex pacificus ’, James resisted pressure to intervene militarily in Continental Europe on behalf of his daughter and son-in-law, who were not only ejected from Bohemia but also saw their German territories overrun by Catholic Habsburg forces. Rather, James hoped to achieve a diplomatic solution through a marriage between Prince Charles and a member of the Spanish Habsburg dynasty. But plans for a ‘Spanish Match’ collapsed following the rash decision of

Prince Charles and Buckingham to travel incognito to Madrid in 1623 in an attempt to conclude the marriage negotiations in person. On their return to England after a six-month stay in Spain, Buckingham and Charles instead pursued a French alliance that resulted in the prince’s marriage in 1624 to the Bourbon princess Henrietta Maria. On 27 March 1625, James VI & I died, aged fifty-eight, and was succeeded by his son as King Charles I.

A King of Words

James had an irrepressible love of lexis and wordplay. An inventive neologist, the king is quoted over 650 times in the Oxford English Dictionary, with his writings cited over 200 times as the earliest recorded instance of a word being used to denote a particular meaning, and over 100 times when a word was seemingly used for the first, and sometimes only, time. According to the Dictionary, words inaugurated by James include ‘agitate’, ‘Anglican’, ‘anorexia’, ‘concern’ (as a noun), ‘decoration’, ‘demonology’, ‘Highlander’, ‘impostor’, ‘limited government’, ‘meat-eating’, ‘polysyllable’, ‘preening’, ‘preoccupied’, ‘quintessence’, ‘turbaned’ and ‘weld’ (as a verb). Admittedly, the Dictionary ’s citations more accurately reflect the popularity of certain authors among its readers and lexicographers than supply definitive proof of neologisms, and the marked prominence accorded by the Dictionary to the Jacobean era is largely attributable to Shakespeare being cited over 30,000 times.1

James’s locution is, nevertheless, richly distinctive and appealing. He labelled the Protestant polemicists John Knox and George Buchanan ‘archibellouses [archbellows] of rebellion’; attributed the fall of the Roman Empire to ‘mollities and delicacy’; and prescribed severe punishment for ‘poly-pragmatic Papists’. Elsewhere, the king encouraged Prince Henry to frame carefully his ‘enregistrate speech’ as a permanent record, counselled him against ‘orping’ (fretting), and recognized his own youthful ‘greening’ (yearning) for fame as a poet. Aside from citations in the Oxford English Dictionary, a large proportion of the king’s neologisms were in vernacular Scots, which remained the language of imaginative literature as well as of the government and the law in Scotland. James’s reign also witnessed the peak in popularity of neo-Latin humanist culture ‘with its reverence for the classical (and pagan) past’,

albeit ‘at the exact same time as Scotland became one of the most doctrinaire Reformed countries in Europe’.2

‘Spendidly logocentric’ is how one historian has saluted the impact of this wordsmith monarch.3 To convey the enduringly infectious character of James’s logophilia, I have foregrounded his own words as much as possible, as articulated in formal publications, parliamentary speeches, royal proclamations, private letters and reported conversations. James was unique among early modern monarchs in his enthusiastic embrace of printed media, in particular, as a vehicle to enunciate the extent of his royal powers and objects of his detestation, as well as his formidable learning. Anonymously printed in Edinburgh in 1584, James’s first publication, The Essays of a Prentice, in the Divine Art of Poetry, included a manual of poetic theory as the eighteen-year-old king sought to establish his cultural authority and to promote distinctive forms of literary creation in the Scots language. A second volume of verse, His Majesty’s Poetical Exercises at Vacant Hours, followed in 1591, while James’s Daemonologie (1597) examined the power of demonic forces in society, taking the form of a dialogue between Philomathes (‘someone who loves to learn things’) and Epistemon (‘someone who understands what he is talking about’) – two epithets that might just as aptly be applied to its royal author. The Trew Lawe of Free Monarchies (1598) cemented James’s reputation as one of Europe’s foremost proponents of the theory known as the ‘Divine Right of Kings’, while Basilicon Doron, published the following year, contained his contention that ‘books are vive [accurate] ideas of the author’s mind.’4 Four days after of Elizabeth I’s death in March 1603, an anglicized edition of Basilicon Doron was entered into the English Stationers’ Register on behalf of a booksellers’ syndicate, with copies available to purchase on London’s streets two days later, while Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, German, Hungarian, Swedish and Welsh translations appeared thereafter.5

Shortly after succeeding to Elizabeth’s throne, James unleashed a printed Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604), lambasting the substance’s recent arrival in England and asserting his royal duty – ‘as the proper physician of his politic body’ – to save his new subjects from toxic hellfire.6 Following discovery of the Gunpowder Plot in London in November 1605, James turned to theological controversy in repeated attempts to deny the papacy a temporal authority that could be used

by Catholics to legitimize such atrocities. Issued anonymously in 1608, James’s Triplici Nodo, Triplex Cuneus. Or an Apology for the Oath of Allegiance was republished under the king’s name the following year, with a ‘premonition’ reminding Protestant and Catholic monarchs alike of the papacy’s record in encouraging rebellion. Although chary about meddling in the affairs of other countries, in 1615 James publicly denounced as incendiary an oration delivered in the French EstatesGeneral by Cardinal Jacques Davy du Perron. In his determination to proscribe rebellion and bloodshed, James was confident that ‘many millions of children and people yet unborn, shall bear me witness.’

God had, after all, elevated him to kingship’s ‘lofty stage’ precisely to ensure ‘that my words uttered from so eminent a place . . . might with greater facility be conceived’.7 While the king’s final publication took the form of a Letter and Directions Touching Preaching and Preachers in 1622, he also issued an unusually high number of edicts in the form of printed proclamations throughout his reign. Insisting that ‘most of them myself doth dictate every word’, James contended that there was ‘never any proclamation of state and weight which I did not direct’.8 He was likewise an attentive editor of other people’s prose. Returning a draft document regarding the intended naturalization of Scots, for example, Sir Thomas Lake alerted the Earl of Salisbury to places where James had ‘thought there was some superfluity’, adding that he ‘prays to be excused for playing the secretary’.9

James’s most spectacular printed achievement was the folio edition of his collected Works published in 1617 that extended to over 500 pages and generated a Latin translation in 1619 and an expanded English edition in 1620. Prefacing the first edition, Bishop James Montagu of Winchester acknowledged the Bible as an inspirational model, explaining how books of scripture circulating individually had been collected together in order to constitute Holy Writ. Accordingly, James’s decision to monumentalize his writings for posterity has been deemed an ‘act of deliberate self-canonization’.10 Yet if no king had previously published their collected writings, several months earlier Ben Jonson had become the first dramatist to include stage plays in a folio edition of his collected Works, and both James and Jonson provided precedents for the first folio edition of Shakespeare’s collected Works (1623). Venturing into print for the first time in 1610 with his prose polemic, Pseudo-Martyr, John Donne had welcomed ‘your Majesty’s books, as

the sun, which penetrates all corners’. Dedicating Pseudo-Martyr to James, Donne hoped that it offered reciprocal homage to a king who had ‘vouchsafed to descend to a conversation with your subjects, by way of your books’.11 A decade later, the metaphysical poet George Herbert echoed Donne’s observation. James was a monarch who sought ‘to be thumbed in our hands; and laying aside thy majesty, thou dost offer thyself to be gazed upon on paper, that thou mayest be more intimately conversant among us’.12

Clearly, if other monarchs and noble writers disdained the ‘stigma of print’ and eschewed its possibilities, James did not. In his preface to James’s collected Works, Montagu acknowledged the cavils of critics who doubted that ‘it befits the majesty of a king to turn clerk.’ Since ‘book writing is grown into a trade’, it might be thought ‘as dishonourable for a king to write books, as it is for him to be a practitioner in a profession’. Although writing was central to James’s conception of royal authority, the very idea of a royal author disconcerted those more accustomed to royal prohibitions on free speech, as regularly enjoined by Elizabeth. As Montagu recalled, James’s subjects regarded ‘his Majesty’s books, as men look upon blazing-stars, with amazement, fearing they portend some strange thing’. James’s kingly status blurred boundaries between printed precept and official edict. It might rather be hoped, Montagu added ambivalently, that, ‘if a king will needs write, let him write like a king, every line a law, every word a precept, every letter a mandate.’13

Subsequent British monarchs seem to have shared Montagu’s wariness. Charles I’s volume of devotional meditations, Eikon Basilike, owed its prominence to its posthumous character, being first released for sale hours after its author’s public execution in January 1649. Two centuries later, when extracts from Queen Victoria’s Highland journals were published in 1868, their editor hastily reassured readers that ‘all references to political questions, or to the affairs of government, have, for obvious reasons, been studiously omitted.’ Only the queen’s impressions of Scotland’s rugged scenery and its rustic inhabitants were presented. The reviewer for the London Times was delighted, admiring how Victoria ‘takes us by the hand, she sits by our firesides, and she opens to us her heart . . . she lays aside her robes of state and enters into friendly conversations with her subjects’.14 Charles III also chose to stay within the Scottish confines of the royal family’s

Balmoral Estate when, as Prince of Wales, he published a children’s story, The Old Man of Lochnagar, in 1980, before later producing A Vision of Britain: A Personal View of Architecture (1989) and coauthoring Harmony: A New Way of Looking at our World (2010). In other words, nearly all monarchs apart from James have believed that the arcana imperii – the secrets of government known only to those in power – are better preserved as private credos than printed manifestos.

For the potency of print also brought potential pitfalls for royal authors. James himself believed in protecting the arcana imperii and his collected Works include a speech delivered in 1616 to England’s common-law judges, making clear that any matter ‘which concerns the mystery of the king’s power, is not lawful to be disputed’. Prying into politics was unlawfully ‘to take away the mystical reverence, that belongs to them that sit in the throne of God’.15 Mystical reverence could not, however, prevent accidental printers’ errors marring royal publications. Nor, in starting conversations with his subjects, could James deter readers from readily construing or misconstruing his intended meanings. Indeed, his final publication – a missive to the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1622 – aimed to curb debate and avoid ‘unprofitable, unsound, seditious, and dangerous doctrine’ emanating from England’s pulpits.16

To his subjects, James’s publishing activities self-evidently encouraged debate. Long before ‘speech act theory’ gained traction in the twentieth century, the Puritan polemicist Thomas Scott contended in Vox Regis (‘The Voice of the King’), published in 1624, that James’s ‘words and writings are published to this end and called his Works, because they should be turned into works’.17 Since James used his printed publications to accomplish political objectives, his subjects should be free to respond likewise. A generation later, the republican poet John Milton envied the authority axiomatically conferred by royal authorship as he struggled to counter the popularity of Charles I’s posthumous Eikon Basilike. In the second edition of Eikonoklastes (1650), Milton ruefully conceded that the moment ‘a king is said to be the author’, nothing more was needed ‘among the blockish vulgar, to make it wise, and excellent, and admired, nay, to set it next [to] the Bible’.18

There was, moreover, a compelling case to set King James’s Works alongside the ‘King James Bible’. For nowhere is the distinctive diction

and syntax of the Jacobean era more enduringly resonant than in the translation of the Bible published in 1611 by the King’s Printer, Robert Barker. Regarded as the ‘authorized’ version of Scripture on account of its royal sponsorship, its dedicatory epistle acclaimed James as ‘the principal mover and author of the work’.19 Amid celebrations of the translation’s 400th anniversary in 2011, one critic pronounced its sonorous cadences and verbal climaxes as ‘quite simply what English prose is, or ought to be’.20 In 1968, half a billion people worldwide listened on Christmas Eve to a live broadcast in which astronauts aboard Apollo 8 read aloud from the ‘King James Version’ to celebrate the first lunar orbit by a manned spacecraft.

Among North American Protestants, the ‘King James Version’ remained the best-selling translation of the Bible until the mid-1980s, with some of its most fervent adherents forming the ‘King James Only’ movement to insist on the Jacobean version’s doctrinal superiority, deny the legitimacy of alternatives and, in some quarters, assert its divinely inspired infallibility. As the translation celebrated its quatercentenary, the literary scholar Gordon Campbell detected a defiant self-assurance among some admirers: ‘Just as real men do not eat quiche, so, in a range of T-shirts sold on the Internet, “real men use a King James Version Bible”.’21 In the twenty-first century, the growth of activist translation has generated more versions, including The Queen James Bible (2012), whose anonymous editors justified its renaming on the grounds that ‘King James was a well-known bisexual.’ While retaining the ‘poetic, traditional and ceremonial language’ of the translation issued in 1611, The Queen James Bible included eight verses revised ‘in a way that makes homophobic interpretations impossible’.22

Homophobia has certainly been one factor shaping James’s later reputation. Contemporaries and critics alike acknowledged the intensity of the king’s capacity for love. Having served as one of Queen Anna’s chaplains, Bishop Godfrey Goodman of Gloucester later claimed of James that ‘no man living did ever love an honest man more than he did’; Goodman had never known anyone with ‘such a violent passion of love as he had’.23 In an undated letter, probably penned in late 1622, James described to George Villiers, then Marquis of Buckingham, his

desolation at their recent separation. Able to ‘do nothing but weep and mourn’, the king had taken a horse and ridden ‘this afternoon a great way in the park without speaking to anybody and the tears trickling down my cheeks, as now they do that I can scarcely see to write’. To ‘harden my heart against thy absence’, James had tried to focus on ‘thy defects with the eye of an enemy’, but quickly recognized that ‘this little malice is like jealousy . . . as it proceeds from love, so it cannot but end in love’. Hoping that his beloved might ‘come galloping hither’ the next day, the king insisted that ‘for God’s sake, write not a word again, and let no creature see this letter’.24

In memoirs published during the 1650s, a former courtier, Francis Osborne, blamed the mid-century civil wars on royal financial mismanagement, accounting James to have been ‘like Adam . . . the original of his son’s fall’. He also censured the political impact of the king’s ‘love, or what else posterity will please to call it’ for ‘his favourites or minions, who like burning-glasses were daily interposed between him and the subject, multiplying the heat of oppressions in the general opinion’. Moreover, James’s readiness in ‘kissing them after so lascivious a mode in public, and upon the theatre, as it were, of the world’ only encouraged ‘many to imagine some things done in the tyring-house [backstage], that exceed my expressions no less than they do my experience’. While Osborne left further speculation ‘floating upon the waves of conjecture’, subsequent critics were more sharply censorious.25 For the historical novelist Sir Walter Scott, ‘the odd familiarities which James used with his favourites’ were ‘to say the least, most disgusting and unseemly’, while the Victorian court historian John Jesse rejected as ‘hypocritical trash’ James’s printed dedication to Buckingham of his ‘Meditation upon the Lord’s Prayer’ and denounced the ‘gross indecency’ of their private correspondence.26

Recent commentators are, thankfully, more sanguine. One of Buckingham’s biographers has described James’s love for him as ‘joyful, overwhelming – the kind of love that ambushes at first sight’, while dismissing as unhelpfully anachronistic ‘the question of who-doeswhat-to-whom-in-bed’.27 Meanwhile, the Shakespearean scholar Will Tosh has reminded readers that ‘early modern queer lives weren’t lived with the doctrinaire clarity of today.’ Since ‘few people ever found themselves labelled a “bugger” or “sodomite” as defined by law’ in early modern Britain, proscribed sexual acts may well have been

‘vanishingly rare in prosecution, yet an everyday activity in practice’. While Tosh judged James to have been ‘no queer hero’, he argues that ‘Shakespeare’s passionate interest in queer desire is its own answer, although his personal queerness must have been bi rather than goldstar gay.’ In a stricture that applies equally to James, Tosh further insisted that ‘examining Shakespeare’s queer life and art doesn’t mean erasing his wife or his children, just as their existence doesn’t disprove his queerness.’28

More virulent than homophobia among Jacobean contemporaries was the vicious anti-Scottish xenophobia that greeted England’s new king at his accession in 1603 and kiboshed his vision of closer British union. In his Westminster speech in March 1607, James wearily acknowledged English fears ‘that this Union will be the crisis to the overthrow of England and setting up of Scotland’. Although he refused to credit claims ‘that Scotland is so strong to pull you out of your houses’, the king could not dispel popular panic that England would ‘be overwhelmed by the swarming of the Scots, who if the union were effected, would reign and rule all’.29 In 1604, the Scots union commissioner, Thomas Craig of Riccarton, spent several months in London and was dismayed by the extent of entrenched enmity. While Craig was convinced of the need for ‘a single heart and mind in Britain both to make and to resist attack’, he noted how, when English parents taught archery skills to their children, they ‘encourage them to take good aim by saying, “There’s a Scot! Shoot him!” ’. Craig had also met an English lawyer – ‘a man of some importance in his own opinion’ – who had confidently denied that any ‘English king had ever thought of conquering Scotland’, adding that ‘there were no educated men in Scotland and no universities, nor any laws other than those which had been borrowed from England’.30 But, as Craig knew, although England had its two universities of Oxford and Cambridge, Scotland had five such establishments, following the foundations of St Salvator’s College in St Andrews (1450), Glasgow University (1451), Marischal and King’s Colleges in Aberdeen (1493 and 1495) and Edinburgh University (1583).31

If English children imagined Scots as target practice, Guy Fawkes bragged that ‘his intent was to have blown them back again into Scotland’ during interrogations after the Gunpowder Plot’s discovery in November 1605.32 Two years earlier, Fawkes had objected of James’s

court that ‘near his person everyone in his Chamber are Scots – wherever there is an English official, he has placed another Scotsman’, according to an intelligence report reviewed by the Spanish court.33 Sitting in Parliament in 1610, the Nottinghamshire MP Sir John Holles likewise complained of James that ‘the Scots monopolise his princely person, standing like mountains betwixt the beams of his grace and us.’ Holles bore no ill-will to Scots courtiers, ‘only I wish equality, that they should not seem to be the children of the family, and we the servants’.34 Addressing Parliament four years later, the Hereford MP John Hoskins admired Canute’s decision to dispense with Danish advisers when he became English king in 1016. The anti-Scottish implications of Hoskins’s additional reference to the Sicilian Vespers – a rebellion in 1382 against a French-born king in which around 3,000 French settlers had been massacred by native Sicilians – were deemed so incendiary that Hoskins was detained in the Tower of London for over a year.

Yet Hoskins’s hostility paled by comparison with the vitriol of a Latin mock panegyric, Corona Regia, published by an anonymous Catholic author in the Low Countries in 1615. Amid a volley of insults, its author denied James’s legitimacy as king, attributing his capacity to ‘ignore, despise, and if necessary, even kill’ his mother to his having been ‘a suppositious child’ placed in ‘the royal swaddling clothes and cradle’ beside Queen Mary by heretic Protestant clerics. The tract’s author likened the adult James to an oversized whale who sought to ‘blast his spray high aloft’ by attacking the papacy ‘with a sopping quantity of words’, cuttingly conceding that ‘no king dared do this before, and certainly no one but you could.’ Corona Regia ’s author also mocked James’s physical person, venturing ‘Come on British, take heart ministers, no-one is going to fault all things curved, twisted, and wretched; by the example of the king, all things straight, level, and upright shall be banished.’35 Regarding the latter affront, modern analyses of James’s reported physical, neurological and behavioural abnormalities have since yielded a range of diagnoses including cerebral palsy and LeschNyhan Syndrome.36

Although James directed effort and expense in trying to identify its author, Corona Regia was unlikely to have been widely read in Britain. But the same could not be said for the slew of savage critiques published after the English Parliament’s decision to place James’s son – the Scots-born Charles I – on trial for treason, leading

to his execution in 1649 and the abolition of the monarchy shortly thereafter. Providing fertile fodder for generations of James’s detractors, a tract entitled The Court and Character of King James was published in 1650, attributed to a former Jacobean courtier, Sir Anthony Weldon, who had died in 1648 after serving as a prominent Parliamentarian governor during the civil wars. Of James’s physical appearance, Weldon recalled that the king’s ‘beard was very thin, his tongue too large for his mouth, which ever made him speak full in the mouth, and make him drink very uncomely, as if eating his drink, which came out into the cup of each side of his mouth’. Meanwhile, ‘his legs were very weak’ and ‘his walk was ever circular, his fingers ever in that walk fiddling about his codpiece’. In an epithet that stuck, Weldon claimed that James had evidently been reputed ‘the wisest fool in Christendom, meaning him wise in small things, but a fool in weighty affairs’.37

Two generations later, the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 saw James’s grandson James VII & II flee from London into French exile, before suffering military defeat by his Dutch nephew and son-in-law, William of Orange, at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland in July 1690. Jacobitism thereafter became synonymous with discredited Stuart despotism. Imitating the slanderous account of the Emperor Justinian’s reign penned by the Greek historian Procopius, Walter Scott anthologized the Interregnum’s hostile critiques in his Secret History of the Court of James the First, published in 1811. Six years later, Isaac Disraeli – father of Benjamin – was dismayed by the accrued torrent of invective and sought to restore ‘the character of James the First, which lies buried under a heap of ridicule and obloquy’.38 But the pantomime caricature had become entrenched and, by the mid-nineteenth century, the doyen of Whig history, Lord Macaulay, made clear his revulsion as he saw James ‘exhibited to the world stammering, slobbering, shedding unmanly tears, trembling at a drawn sword, and talking in the style alternately of a buffoon and a pedagogue’.39

Over a century later, J. P. Kenyon reproduced Macaulay’s reproof almost verbatim in his study of ‘English [sic] kingship’ entitled The Stuarts (1958), discerning ‘an element of buffoonery in all he [James] did’ and claiming that ‘at dinner his vulgarity, obscenity and uproarious pedantry had full play, as he slobbered in his drink’; if not actually intoxicated, ‘with his slurred speech, his heavy Scots accent and his

restless, rolling eye, he must often have seemed so.’40 A buffoon, a pedagogue – and also a persecutor. In 1921, lavish celebrations were staged in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to mark the tercentenary of New England’s founding by ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ who had sailed from England aboard The Mayflower in 1620. An outdoor pageant was performed on a specially constructed stage by Plymouth Bay before audiences of up to 20,000, with honoured guests including President Warren Harding. Written and directed by Professor George Pierce Baker of Harvard University, the pageant included a scene depicting Puritan nonconformists suffering in England and the Dutch republic, with an actor playing King James ‘shouting above a cacophony of bagpipes, “A Puritan is a Protestant scared out of his wits . . . I shall make them conform or I will harry them out of this land – or do worse” ’.41

The toxically unflattering account unleashed by David Harris Willson in his biography James VI and I (1956) only fuelled readers’ fevered imaginations. Academic critics were not uniformly enamoured, with one reviewer finding innumerable ‘examples of what Dr Samuel Johnson might have called its “bottomless Whiggery” ’ in which an entirely incompetent, indolent and inane James could seemingly nonetheless rule as ‘half a despot in England and a total one in Scotland’.42 Indeed, Willson’s biography presented an ‘astonishing spectacle of a work whose every page proclaimed its author’s increasing hatred for its subject’, as Jenny Wormald observed in her Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for King James in 2004.43 Two decades earlier, Wormald had herself rhetorically wondered whether James was ‘two kings or one’, given his starkly divergent historical reception on either side of the Anglo-Scottish border. Juxtaposing the views of two scholars of similar age and professional stature, Wormald had contrasted Gordon Donaldson’s cool assessment that, as King of Scotland, James had been ‘a man of very remarkable political ability and sagacity in deciding on policy and of conspicuous tenacity in having it carried out’, with Lawrence Stone’s shrill insistence that ‘as a hated Scot, James was suspect to the English from the beginning, and his ungainly presence, mumbling speech and dirty ways did not inspire respect’.44

Four centuries after James’s death, the depressingly common default response to mention of his name remains the glibly sarcastic dismissal that ‘James I slobbered at the mouth and had favourites; he was thus a

Bad King,’ as taken from W. C. Sellars and R. J. Yeatman’s parodic rendering of English history, 1066 and All That, first published in 1930.45 A Spectator book review in 2021 casually referred to ‘the goggle-eyed, slobbering Scottish king, James, with his peculiar penchant for shitting in the saddle while pursuing his passion for hunting’.46 In the fictional drama Mary and George (2024), James appeared, to one television critic, as ‘the mercurial sovereign, who veers between moments of lucidity and long stretches of what seems like madness, though it’s never identified as such’.47 As one commentator remarked at the start of the twenty-first century, ‘the awkward figure of the Stuart King continues to block the recuperative efforts of history, constantly under rehabilitation but somehow never quite rehabilitated.’48

Four centuries is too long for anyone to remain in rehab. The Mirror of Great Britain seeks neither to valorize nor to denigrate but rather to restore appreciation of the sheer difficulty, intensity and complexity faced by James as ruler of late sixteenth-century Scotland and as the first British king. Less The Comedy of Errors and more Macbeth, James had to survive recurrent assassination threats and navigate bitter confessional conflict, religious persecution and violent vendettas. Likewise, although the lure of early seventeenth-century overseas colonial endeavours might be rendered magical through The Tempest ’s stagecraft, their grim reality entailed commercial greed, genocide and savagery. In Devil-Land: England under Siege 1588–1688 (2021), I characterized Stuart England as denoting an era of endemic instability and geopolitical insecurity, and such leitmotifs apply equally to James’s Scottish and English reigns. Amid the chiaroscuro contrasts, the king that emerges in the ensuing pages is intelligent, resilient, idiosyncratic, irascible, guileful and witty. No monarch in British history was keener for his subjects to know him and more intent on communicating his vision of kingship. If there was a desire for gloire, there was also a keen awareness of the need for self-preservation. A fortnight after the assassination of the French king, Henri IV, in May 1610, James insisted to English peers and MP s that there was ‘nothing that shall concern the commonwealth, but I will be careful the people shall know it’. For ‘the more the people know the reasons of my doings’, the more royal power was respected. While James recognized that, ultimately, ‘my glory and security stands in the love of

my subjects’, the veracity of this maxim would be borne out in the fate of his son and successor, Charles I.49

In James’s early years, the very notions of royal power and the monarchical prerogative required rehabilitation, following his coronation as an infant King of Scotland by a faction that had removed his mother from power by enthusiastically extolling rights of resistance and tyrannicide. In early 1584, the seventeen-year-old James wrote to his French uncle, Henri, Duke of Guise, alarmed that ‘the strength of my enemies and rebels is growing daily’. In a letter intercepted by Elizabeth I’s ministers, James told his uncle that he had ‘abandoned the English faction’ among his advisers as he suspected the English queen of seeking ‘the subversion of my state, and the deprivation of my own life, or at least my honour and liberty, which I prize more than my life’.50 As King of England, James reiterated in 1608 that he accounted ‘my reputation’ to be ‘ten times dearer to me than my life’ in a letter to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury.51 Small wonder, then, that when he addressed the Westminster Parliament six years later, James rejected the attempts of MP s to challenge his right to levy certain taxes, by warning that he would ‘die a 100 deaths before he would infringe his prerogative’.52

Small wonder, too, that a king of words was admired for his rhetorical dexterity, but also distrusted. After one audience with the fourteen-yearold Scottish king in 1581, Elizabeth I’s envoy, Baron Hunsdon, advised her Principal Secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham, that the English queen would soon learn that ‘the king’s fair speeches and promises will fall out to be plain dissimulation.’ When it came to dissembling, Hunsdon rued that James was, ‘in his tender years, better practised than others forty years older than he’. And as Hunsdon emphasized three weeks later, Elizabeth was ‘not to trust to any word or promise’ made by the Scottish king, who was regarded by his advisers as ‘the greatest dissembler that ever was heard of for his years’.53

By the time James acceded to the English throne, the resident Venetian Secretary in London identified his chief trait as a ‘dissimulation’ that ‘constantly consisted in giving hopes to all, but never anything further to any’. Indeed, James had disarmingly defended this approach as the only means to have ‘escaped the dangers he had been in when king of Scotland’, believing it equally effective now he was ruler ‘of a great kingdom, of which he knew neither the people, the affairs, nor

the neighbours’.54 Dissimulation created room for diplomatic manoeuvre. For one French ambassador, James was ‘a king of artifices who dissimulates above all the rest of the world’, while a political maxim posthumously attributed to James was the credo that ‘greater and deeper’ political actions were achieved by those individuals who ‘can make other men the instrument of his will and ends, and yet never acquaint them with his purpose; so as they shall do it, and yet not know what they do.’55

This was also the king who, at eighteen, had confidently reassured a French envoy visiting Scotland that, although he spent much time hunting, ‘he could do as much business in one hour as others would in a day, because simultaneously he listened and spoke, watched, and sometimes did five things at once.’56 Fusing fatherly and royal advice, James later advised Prince Henry to remain mindful of divine judgement, ‘ever learning to die, and living every day as if it were your last’.57 Adept at working remotely, James responded to ministers’ queries by return; as Salisbury admired in 1607, the king was ‘quicker at a letter than the posts are with the packets’.58 One communication from James to Salisbury bore the holograph endorsements: ‘Royston [Hertfordshire], 16 January at past eight in the night. Haste, Haste, Haste, Haste, Haste for life, life, life. Royston, 16 of January at past 10 in the night. Ware, 17 January, at one in the morning.’59