‘Magical’ Sunday Express

‘Comic, adventurous and charming’ Guardian

‘Funny, sweet and charming – a real delight!’

Sam Copeland , author of Charlie Changes Into a Chicken

‘Utterly gorgeous storytelling . . . The Last Firefox will long burn bright in your heart’

Jenny Pearson , author of The Super Miraculous Journey of Freddie Yates

‘Crackles with adventure and love’

Maria Kuzniar , author of The Ship of Shadows

‘An enchanting fantasy adventure as warm as a firefox’s tail . . . a joyous gem!’

Lesley Parr , author of The Valley of Lost Secrets

‘A heart (and tail!) warming adventure about family, friendship and one flamin’ cute fox cub’

Thomas Taylor , author of Malamander

Author photo © Desiree Adams

Author photo © Desiree Adams

Lee Newbery lives with his son and dog in a seaside town in West Wales. By day he works for an arts charity, helping people to share their stories through creative writing, painting and participatory arts, and by night he sits down at his laptop to write.

Lee Newbery lives with his son and dog in a seaside town in West Wales. By day he has a boring grown-up job, but by night he sits down at his laptop to write stories of adventure, magic and love.

Lee Newbery lives with his son and dog in a seaside town in West Wales. By day he works for an arts charity, helping people to share their stories through creative writing, painting and participatory arts, and by night he sits down at his laptop to write.

Lee enjoys adventuring, drinking ridiculous amounts of tea, and giving his dog a good cuddle – or a cwtch, as they say in Wales. His first book, The Last Firefox, was shortlisted for the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize.

Lee enjoys adventuring, drinking ridiculous amounts of tea, and giving his dog a good cuddle – or a cwtch, as they say in Wales. His first book, The Last Firefox, was shortlisted for the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize.

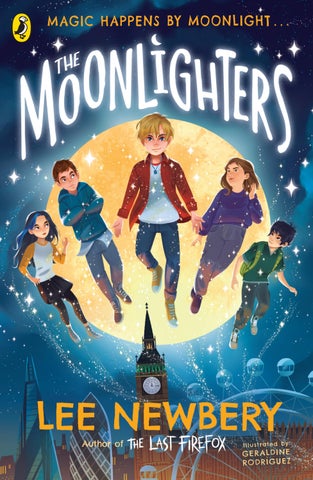

BOOKS BY LEE NEWBERY

The Last Firefox

The First Shadowdragon The Lost Sunlion

The Moonlighters

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Text copyright © Lee Newbery, 2025

Illustrations copyright © Geraldine Rodríguez, 2025

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted Set in 12.8/20pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–0–241–49355–7

All correspondence to: Puffin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned on this school trip to the Natural History Museum, it’s that fossilized dinosaur poop doesn’t smell.

It’s also called coprolite, which is the fancy name scientists use. All right, that’s two things. I guess I’ve paid more attention than I’d realized. I wasn’t expecting to come away from this trip with much new information. Museums aren’t really my thing. Everything’s a bit too . . . dead.

The only reason I know all this stuff is because I’ve been dared to drop a nugget of coprolite into the hood of the ginormous coat Hayley Pritchard is wearing today.

It was all Keegan’s idea, and the rest of the Crew soon tagged on. I think he just wants to get back at her because he fancies her and she won’t go out with him, but he can’t let her know how furious he is, which is why he’s getting me to do the deed for him.

It’s a rubbish dare but I’m not exactly in a position to say no. Keegan and the Crew are the only friends I’ve managed to make at this stupid new school. I’m the new recruit, and if I do this . . . well, I’ll properly be one of them. I’ll be a legend.

I look round the vast room, filled with the skeletons of long-dead dinosaurs. A few of the teachers chat together near a glass cabinet full of swirly rocks, sipping from flasks of coffee and not paying much attention. And the only thing the security guard is guarding is his handheld games console, which he plays from his chair in the corner.

I study the dinosaur poop. It’s on a small pedestal, with a tag next to it that reads: Coprolite – Dinosaur Faeces. It looks like an ordinary rock, about the size of my fist, except it’s a bit . . . knobbly, like a fossilized chicken nugget. Did whatever dinosaur pooped this visit the drive-thru before they met their end?

‘Just do it,’ whispers a voice in my ear.

I turn and find Keegan standing behind me. He’s got this ratty face, all pointy features and narrow eyes.

‘What’re you waiting for? A dino poo bag?’ Keegan sneers and glances over his shoulder. Behind him, the rest of the Crew snicker on cue.

‘No,’ I huff. ‘I’m just . . . waiting for the right moment.’

‘Well, don’t wait too much longer,’ he warns.

‘Remember last week, when you chickened out of putting chewing gum on Mrs Perrot’s seat? We were so disappointed, weren’t we, guys?’

The rest of the Crew nod in agreement.

‘We fancied a laugh,’ says Kayleigh.

‘And this museum is so boring,’ says Keegan. ‘Who cares about all this dead stuff? Let’s liven things up a bit. Ha! Get it? Liven things up a bit! Because everything in here is dead?’

The Crew start snorting hysterically, like a bunch of demented pugs.

‘OK , fine. I’ll do it,’ I mutter.

I turn back to the lump of dino doodoo as Keegan and the Crew retreat across the room, sniggering at me.

Well, not at me, I don’t think. At what I’m about to do.

Hayley stands a few metres away, her back turned, surrounded by a cluster of girls.

And there’s her hood – an open goal. I take a breath.

Don’t do it, says a voice in my head. Mum and Dad would be so disappointed.

And that’s what seals it. Doing something bad is like getting back at them for what they’ve done to me. If my dad hadn’t lost his job a few months ago, we wouldn’t have had to move to this stupid old house in this ridiculously boring village in the countryside where nothing ever happens except for prize- winning butternut squashes. I’d have been able to stay at my old school, where I definitely wouldn’t be about to lob a lump of dinosaur poop into a popular girl’s hood in order to impress my new mates.

I reach out and pick up the coprolite.

OK . OK . I’m holding a lump of dinosaur poop. Something that actually came out of a giant lizard’s

butt, gazillions of years ago. I look around. The security guard is still playing his game. Hayley’s back is turned, and the teachers –

They’re moving! Mrs Perrot has finished her coffee and now she’s turning round. She’s going to see me standing here with a fossil in my hand, and I’m going to be in so much trouble.

There’s no time to drop the poop into Hayley’s hood like I’d planned, so instead I do the only thing I can think of: I toss it.

Time slows as the lump of ancient poop arcs through the air like some sort of meteorite from the bowels of outer space. Sweat beads on my forehead as Mrs Perrot continues to turn. Keegan and the Crew follow the coprolite’s path with wide-eyed focus.

And Hayley – well, at the very last second, Hayley steps to the left, her school bag swinging round and batting the poop right out of the air, sending it whizzing on a new trajectory across the room. My heart leaps into my throat as it soars above the heads of my classmates, straight towards the skull of a velociraptor skeleton elevated on a podium nearby.

My mouth opens around a Nooooooooooooo! but it’s too late.

The coprolite smacks into the velociraptor’s face and falls to the ground, smashing into three pieces.

Heads start turning.

My body seizes up.

And then a groan fills the air, and I watch in disbelief as the raptor’s skull starts to tilt before breaking away from its body and dropping to the marble floor.

It shatters, its lower jaw severing from the rest of its head, sharp brown teeth scattering over the floor. The crashing sound seems to go on and on, and then . . . silence.

The security guard is on his feet. The teachers gawp.

Keegan and the Crew are nowhere to be seen.

There’s only me, standing among the chaos, my cheeks bright red and my hand held up – very much the hand of somebody who’s just thrown something extremely precious and expensive.

All eyes land on me.

So I do the only thing I can think of in that moment. I run.

The next thing I know, I’m running through the grand entrance gates of the Natural History Museum and on to the busy London street. While everything inside the museum was very dead, the air outside buzzes with life. Car horns blare and scarlet double-decker buses zoom down the road.

I look behind me, expecting to see Mrs Perrot and an army of security guards spilling out behind her.

What am I going to do? I can’t go back. I broke a lump of ancient poop and smashed a velociraptor – they’ll arrest me and bundle me off to kiddie jail or something. But where can I go?

The answer arrives on a cloud of taxi fumes: Nan!

Nan lives in London! My parents and I used to catch the train to visit her when I was younger, when I used to enjoy going places with them. Before butternut squash village, and this awful new school where I’m the newbie who doesn’t fit into any of the friendship groups, apart from the Crew. But I remember seeing the station name: Finsbury Park. Nan’s flat is only a few streets from there.

I pull out my phone so that I can give Nan a ring, but my battery’s gone. I whirl round, my eyes searching for the red Underground symbol, and instead I almost collide with somebody standing behind me.

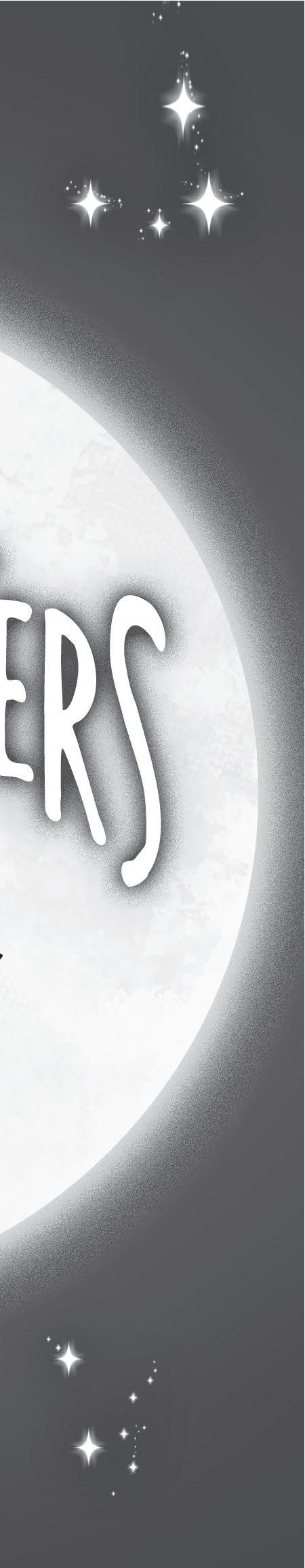

‘Argh, sorry –’ I exclaim, but my voice breaks off when I find myself looking at one of the most peculiar individuals I’ve ever seen.

They’re older than my twelve years – perhaps sixteen or seventeen – and they’re wearing a pair of aviator goggles so big that they hide the top half of their face. On their head is a bright-blue top hat, a sleek peacock feather tucked into the ribbon that winds round it, and on their spindly frame is a dazzling cerulean tuxedo

jacket with tails that swoop to the ground. They’re wearing knee-high boots with astonishingly high heels.

‘You need not apologize,’ they say, ‘for today is a good day to get lost and then find your way again.’

I gawp at them. ‘Eh?’

‘That was a curious sound.’ The stranger sniffs. ‘But don’t you agree?’

‘What?’

‘That today is a good day to get lost and then find your way again!’

The stranger beams, twirling a sleek white cane. It’s topped with a clear stone, which catches the spring sunlight and sends rainbows into the air. Something hums through me at the sight of it – at the sight of them, this bizarre person with their peacock top hat. Something I’ve never felt before, and yet somehow feels familiar.

I glance over my shoulder. The security guard is emerging from the museum, followed by Mrs Perrot. All they have to do is turn and they’ll spot me.

‘Now’s really not a good time –’ I stammer.

‘Fear not,’ the stranger replies, digging into their

jacket and pulling out a tattered old umbrella, which they spring open and thrust into my hands. There are holes in the canopy, one of them so big I’m pretty sure I could stick my head through it.

That familiar hum intensifies as my fingers close round the handle, like I’ve just waltzed into a dream that I’ve had before.

‘Whatever you do, keep the umbrella open above your head,’ they instruct. ‘And stay quiet.’

Without another word, they place their hands on my shoulders and swivel me round so that I’m standing beside them. Then, with a mischievous grin, they turn back to face the museum.

‘What? Are you serious? I need to go –’

‘Ssh!’ the stranger hisses, clacking their cane against the ground for emphasis. ‘Trust me!’

And then it’s too late. Mrs Perrot and the security guard are moving now, ricocheting from pedestrian to pedestrian. I can hear them from here – they’re asking if anybody has seen a young boy running out of the museum.

My heart pounds in my chest. I’m caught. If I run

now, they’ll see me. But if I stay still, they’ll find me anyway.

‘Excuse me, ah . . .’ Mrs Perrot pauses, an eyebrow arched in hesitation. ‘Mr . . . er, I mean, Miss –’

She stumbles clumsily around the words, but at that moment the stranger swoops in and rescues her from her obvious plight.

‘Neither, actually,’ they say, but they do so with an encouraging smile on their lips. ‘Some people feel that neither Mr or Miss quite fit, and so they choose to go by neither. You can be whoever you feel you are on the inside, as long as you are kind. Instead, I go by Mx –’ they say it like the word mix – ‘but it’s OK that you didn’t know.’

Mrs Perrot regards them curiously – with a sense of wonder, maybe? ‘Ah, yes, well . . . now I know. Thank you. So, have you seen a young boy run past?’

The security guard has reached us, with Mrs Perrot trailing behind. Oddly, though, it’s the stranger they are focused on.

‘Hmm,’ the stranger replies. ‘A boy, you say?’

‘Yes,’ says Mrs Perrot. ‘Twelve years old, blonde hair, about this tall?’

‘It’s not a hard question,’ the security guard grunts. They haven’t noticed me. How is that even possible?

‘I suppose not,’ says the stranger. ‘But what gets wetter the more it dries? That is a hard question.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I don’t think they’ve seen him,’ says Mrs Perrot. ‘Come on. Let’s keep looking.’

She takes a step to the side so that she’s right in front of me. My heart leaps into my throat. She scans the other side of the road, then turns her head back and looks directly at me.

Or, rather, through me.

Because her face doesn’t light up with the mixture of rage and relief I was expecting. In fact, her despair seems to deepen. It’s like she hasn’t seen me at all.

But . . . but how? I’m standing in full view, holding an umbrella !

‘I’ll alert the authorities,’ says the security guard, and Mrs Perrot returns her attention to the museum.

‘We have to find him before the end of the day,’ she says, and then they stalk back to the building together.

What on earth just happened?

A few seconds pass in silence. My mouth is open so wide you could fit three tennis balls inside. Once Mrs Perrot and the security guard are safely out of sight, the stranger sighs and wheels round to face me.

‘It was a towel,’ they say. ‘Eh?’

‘The thing that gets wetter the more it dries. A towel. Nobody ever gets that one.’ They pull a face at the umbrella I’m still holding. ‘Put that thing down, will you? You’ll have somebody’s eye out with one of the spokes.’

When I make no move to lower it, they pluck it from my fingers and do it themselves.

‘W-what just happened?’ I finally manage.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘My teacher looked right at me. Or, at least, I thought she did, but then she looked away like she hadn’t seen me at all!’

The stranger cackles. ‘Oh! The umbrella, silly!’

‘The umbrella?’

‘Yes,’ they reply proudly. ‘Deflects more than just rain, if you know what I mean.’

‘No,’ I blurt. ‘I don’t know what you mean.’

The stranger rolls their eyes – which, I swear, when they catch the fading sunlight, sparkle violet.

‘Attention! It deflects attention. When you use my umbrella, you can walk down the street without a single person noticing your presence.’

‘What, like you’re invisible or something?’

‘I suppose you could say that,’ they reply. ‘I had a feeling I’d need it today, if you know what I mean.’

‘Will you stop saying that?’ I snap. ‘I don’t know what you mean. There’s not a cloud in the sky!’

‘I mean the streets are particularly busy today. And sometimes, you don’t want to be seen. Isn’t that right?’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ I say, glancing over my shoulder at the museum. No security guards or teachers to be seen – but how long before they come back?

‘Mmm,’ says the stranger, pursing their lips. ‘So, ah . . . ?’

‘Theo,’ I say automatically. I know you’re not supposed to share your name with strangers, but there’s something very inviting about this person.

‘Theo.’ They smile. ‘So, Theo, can I assist you in any way?’

Now that they mention it, I could do with some help. Sure, I’ve been to London before, but I was always with Mum and Dad. And now I’ve got to find Nan’s flat on my own. I would phone her if my battery wasn’t dead. Anyway, I don’t want to talk to my parents, not until I’m safe with Nan, so she can convince them that what happened at the museum was just a huge misunderstanding.

Except it wasn’t really, was it? I meant to take the coprolite. I even meant to throw it. I just hadn’t anticipated Hayley swinging her school bag like a

champion cricket player’s bat. It all went wrong in the space of two seconds, and now I’m in deep dino dung.

Maybe Keegan and the Crew will back me up. Say it was their idea and just a prank. Yes. That’s what’s going to happen. I try not to think about how they vanished the moment things went wrong.

‘Erm, do you have a phone I could use?’ I ask in a small voice.

The stranger’s face lights up. ‘Ah! It’s your lucky day! As a matter of fact, I am indeed in possession of a telephone, and I should be delighted to let you use it!’

The relief wraps itself round my waist like a cloud of balloons, making me feel all light and feathery.

‘Thank you so much. It will just be a quick call, I promise!’

‘All right then, follow me!’ They turn on their extravagant heel and start marching down the street.

I stare after them. ‘Erm, what?’

‘Well, you need to follow me back to my home so that you can use the telephone.’

‘Oh,’ I say, my heart sinking. ‘I thought you meant I could use, you know . . . your mobile phone?’

‘Mobile phone,’ they repeat, turning the words over in their mouth like a sour sweet. ‘Heavens, no. I don’t carry one of those. But if you’d just like to follow me –’

‘No, thank you.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I can’t go with you,’ I say. I really need a phone, but following a stranger back to their house . . . that’s a bit too far. ‘How do I know you’re not a murderer? Or a kidnapper? Or a cannibal? You might have your oven pre- warming to a hundred and eighty degrees, right now.’

They nod, thoughtfully. ‘That is quite true. You have absolutely no way of knowing I’m not dangerous. How very wise of you. Are you sure?’

I nod, even though I really do want to use their phone. ‘Yes, but thanks for the offer.’

‘A polite young man,’ they muse, ‘who just happens to have got into a spot of bother. We’ve all been there.’

They stare off into the distance, like they are recalling a sad memory. Then they shake their head. ‘Anyways, I must dash. It’s been lovely talking to you, Theo.’

‘You too,’ I say.

‘One more thing, before I take my leave,’ they say, reaching into their jacket. They pull something out and extend it to me. It’s a card.

I take it and look down at the curlicued writing. It reads: Mx Alistair Goodfellow cordially invites you to stay at the Casablanca Lily, the hotel for vagrant children.

I look up. ‘Is this some kind of joke?’

‘Oh, there’s absolutely nothing funny about it,’ they say, without even the slightest hint of a wobble in their voice.

‘But how did you . . . ?’ I falter. This individual is a bit too strange. First, the funny umbrella that can apparently make you invisible, just when I needed not to be seen. Then, the invitation to some sort of hotel for runaway kids – minutes after I started running away.

It’s all a bit too coincidental. It’s almost like they meant to meet me here.

‘If you change your mind, all you need to do is pay

me a compliment. Just make sure the card hears you,’ says the stranger. ‘Oh, and might I suggest you keep this? I’ve a feeling you might need it. But not to use against rain, if you know what I mean?’

They wink as they hold out the umbrella, and, for the first time, I think I actually do know what they mean. Sort of. There’s not a cloud in the sky, but there are people everywhere – and I’ve no doubt some of them will soon be teachers and police on the lookout for me.

I take the umbrella and my fingers hum once again with that strange sing-song energy, but before I can say anything, my rescuer swirls round and strides off, heels and cane clacking against the pavement as they go.

‘Wait!’ I cry. They pause. ‘Yes?’

‘Who are you?’

‘Alistair Goodfellow, at your service,’ they say, tipping their top hat. ‘Proprietor of the Casablanca Lily and overseer of Moonlighter operations. It’s all there on the card. I bid you good day. For now.’

They give their cane a flick and, just like that, they’re

gone. I’m not sure if the crowd has gobbled them up, or if they’ve actually disappeared – all I know is that they’re there one second and gone the next.

I’m left standing alone on the London streets.

Thanks to the lady who works in South Kensington Station, I find the right Tube train and get to Finsbury Park pretty easily, so less than an hour after setting off, I’m climbing the steps of Nan’s apartment building all the way up to the third floor and come to a stop outside her door. I knock, paste on my biggest, most puppyish grin, and wait. Nothing happens.

I knock again and lean in, listening for the sound of Nan’s slippered feet padding down the hallway, or the sound of her chain locks clinking as she fumbles with them.

But I don’t hear anything.

I try the handle, but it doesn’t budge. It’s locked. My heart sinks.

Where is my nan?

A door opens across the way, and an old woman in a pink coat shuffles out. She pauses when she spots me.

‘Can I help you, young man?’

‘I, er . . .’

‘Are you looking for Carol?’ I nod.

‘Well, you won’t have any luck today,’ the old woman mumbles. ‘She’s on her holibobs in Benidorm. She’s probably sitting by the pool right now with her boyfriend, Paolo, sipping from a glass with a little paper umbrella in it.’

She drifts by, grumbling about expensive cocktails and handsome lifeguards, then disappears down the stairs.

I feel a bit sick. My nan is in Benidorm. Why didn’t Mum or Dad tell me? They’re ruining everything again, and they’re not even here. My cheeks flush furiously when I think about how little I’ve spoken to them over

the last few weeks, how angry I’ve been with them for uprooting my whole life and moving us backwards.

Not even sideways. Backwards.

OK , maybe that’s why they haven’t told me – because I’ve been doing my best not to listen to them. In fact, I’ve been trying my hardest to do precisely the opposite of listening to them. I know Keegan and the Crew aren’t the sort of friends they like me to have, but there was something alluring about doing something they wouldn’t want me to do.

And since I got in with the Crew, I’ve done my fair share of things they wouldn’t like. Just a few weeks ago, we stumbled upon the crumbling ruins of a stone cottage in the woods that border our village, and we started a fire in one of the rooms. Keegan is the one who actually lit it, but I didn’t say anything. It wasn’t supposed to be dangerous – just a mini bonfire we could chuck homework on – but it ended up spreading, and, well . . . we had to make a run for it. Good thing we never got caught.

But I don’t think even that can top this. Running away from a school trip in the middle of London.

I stand there for a few minutes, frozen. This is bad. This is very, very bad. I was going to cosy up in Nan’s flat and enjoy her famous banana bread and a cup of extra-sugary tea while she phoned my parents. Then they were supposed to get on to the school, who would get on to the museum, and everybody would have a bit of a laugh about it.

Instead, I’m stranded in London with no phone, no money, no Nan and no banana bread. This might be the worst day of my life, even worse than when Mum and Dad broke the news that we had to move house.

The sensible option would be to get back to the museum before the school coach leaves and face whatever fate awaits me. But with no money for another Tube ticket, I’d have to walk. That could take hours, assuming I managed to find my way back at all. London is an epic-scale maze.

I turn and plod back down the staircase. I’m just going to have to turn myself in to the first police officer I see. If they send me off to some juvenile prison, so be it.

So that’s how I come to be roaming the London

streets as the sun sets, the cold pressing around me and a wormy feeling at the base of my stomach. The skin of my knuckles pulls white as my grasp tightens round Alistair Goodfellow’s umbrella, which I use like a sort of walking stick. My eyes sting, but I don’t let myself cry. There’s still some tiny part of me that thinks this might all be a huge joke, and that Keegan will jump out from an alleyway any second now and shout, Gotcha!

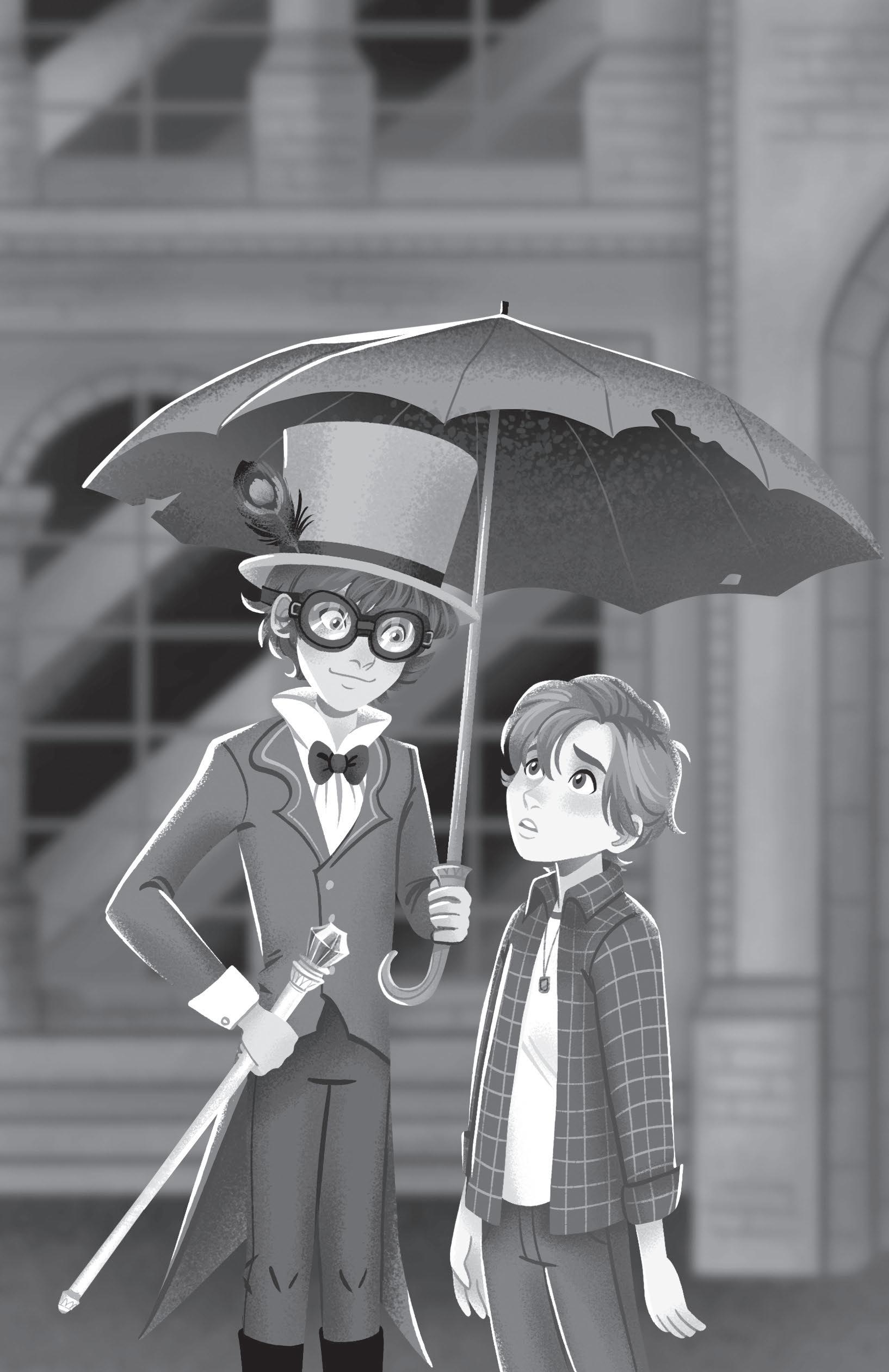

But Keegan doesn’t jump out, nor do I spot any police officers as I trudge the streets. It doesn’t take long for night to arrive, the streetlamps casting murky yellow light across the city. Every road I walk down looks the same, lined with newsagents and takeaways and cafes, and after a while I come to a set of horrible realizations.

I’m lost.

I’m hungry. And I’m being followed.

I look over my shoulder, spot the silhouette of a person ducking behind a bus stop, and let out a whimper. I pick up the pace, my feet moving so fast that they send jolts of pain up my shins – not quite running, but more of a demented penguin waddle. I turn corner after corner, and after a few minutes I stop and cast another tentative glance behind me.

My pursuer is still there, creeping down the pavement. I can’t tell who they are, just that they’re dressed head to toe in black. I swallow hard and start running, hurtling round another corner, before ducking down the next alleyway I find.

Not my smartest move, considering most alleyways lead to dead ends. I turn back to face the entrance, fear making me feel like I might throw up. Any second now, the shadowy figure is going to step into the head of the alleyway and discover me.

Maybe they just want my wallet, or my phone, or maybe they want to gnaw my bones clean of flesh and use them as toothpicks.

Something hisses at me from the darkness over my shoulder, and I spin round, brandishing the umbrella that Alistair Goodfellow gave me like a sword –

The umbrella!

I don’t know if it really made me invisible earlier or not, but it’s worth a shot. I fumble with the handle, opening it like a slug-nibbled flower above my head.

I stand completely still, refusing even to breathe as my hunter steps into view – a tall, willowy young man with a narrow face and ashen skin, and white hair that pokes out from beneath his hood.

But it’s the smile that gets me. It’s the smile a snake might give as it dislocates its jaw to consume its prey.

‘Come out, my little friend,’ he says in a slithery voice. ‘I know you’re there somewhere.’

That word – somewhere. He can’t see me, even though I’m standing in front of him. The umbrella is working again!

‘I can sense you, feel the power in the air, wrapped round you like mist. It’s faint, barely more than a wisp. Ah, how I know that feeling.’

What is it with the people in London today? First Alistair Goodfellow, and now this guy? What is he on about?

‘What’s a young magismith like you doing, walking the streets alone at night?’ the man asks, taking a step towards me. My grasp on the umbrella handle tightens so much I’m scared I might snap it.

‘Why don’t you come out? I won’t hurt you,’ he says, and I hear his lips peel back from his teeth. ‘I just want to talk to you. I might be able to help . . .’

I stay deathly still, his words crawling over my skin. When I don’t respond, he abandons his display of politeness and sighs. ‘If you won’t come to me, I will come to you, and I promise that will not be pretty . . .’

I brace myself for him to pounce forward and discover me, when suddenly the road lights up behind him and the rumble of an engine approaches. The man turns just as a police car pulls up, window rolled down to reveal an officer staring out at him with narrowed eyes.

‘Is everything all right, sir?’ she asks. ‘Lost, are you?’

‘Oh, no,’ he says. ‘Just thought I saw something. I’ll be on my way.’

He casts a final glare at the empty air where I stand, then slinks down the street and out of sight.

The police officer’s gaze lingers on the alleyway, and it takes all my strength not to step out from underneath the umbrella and bellow for help – but how on earth would I explain that?

The police car drives away, and I wait a few seconds before bursting out of the alleyway and running in the exact opposite direction to that man. I want to put as much distance between him and me as I possibly can. I run until my legs scream and my lungs feel like they’re about to burst.

Finally, halfway down a shabby, shop-lined street,