PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw penguin.co.uk

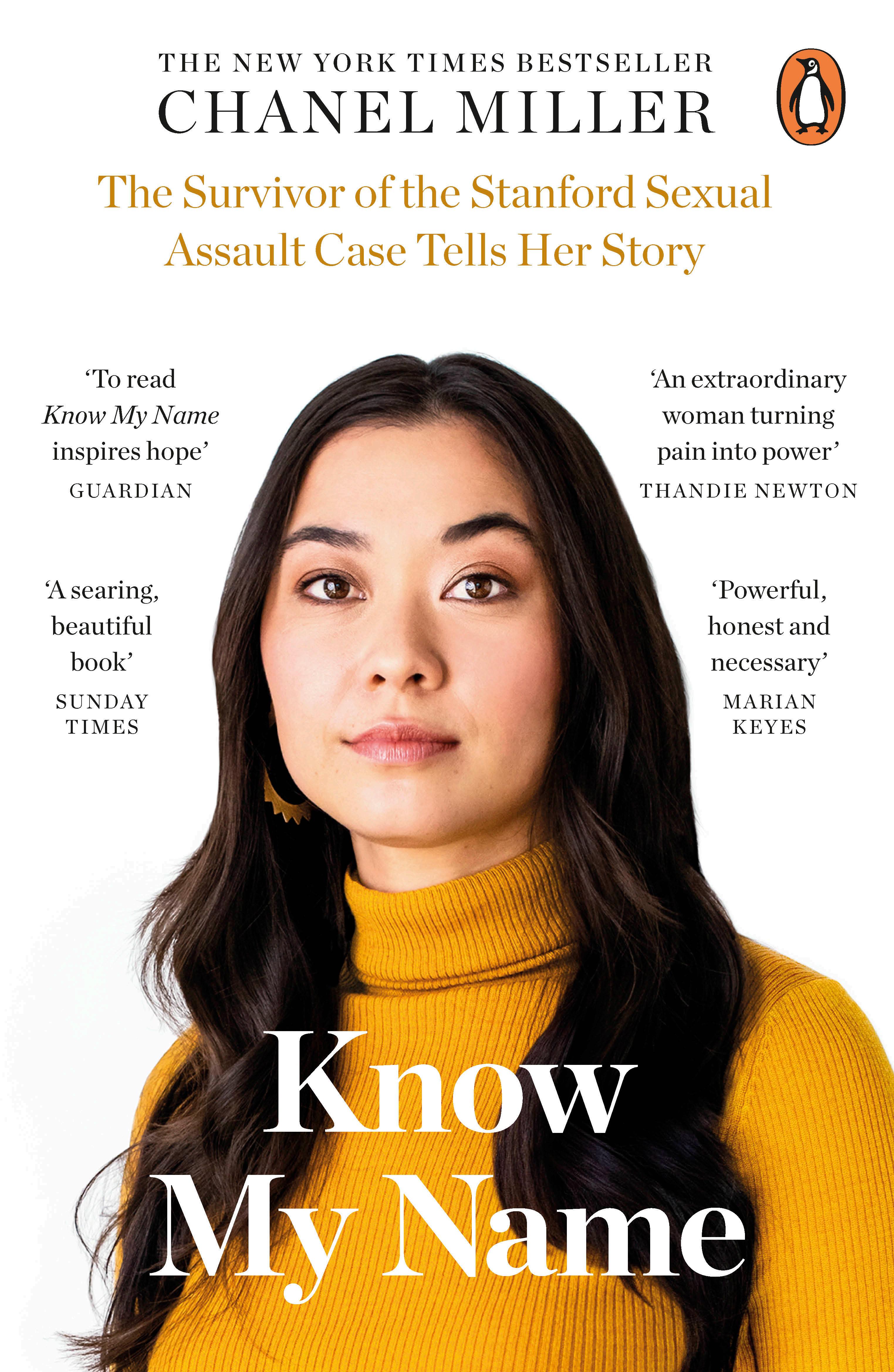

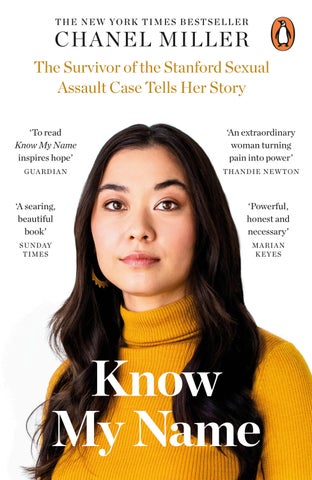

First published in the United States of America by Viking 2019

First published in Great Britain by Viking 2019

Published in Penguin Books 2020 001

Copyright © Chanel Miller, 2019, 2020

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The Victim Impact Statement on pages 341–365 was originally published by BuzzFeed News on 3 June 2016

The poem “And then, all the and thens ceased” excerpted from A Year with Hafiz by Hafiz, translated by Daniel Ladinsky (Penguin Books, 2011), used with permission from Daniel Ladinsky

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978–0–241–42829–0

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

mom dad tiffy

The fact that I spelled subpoena, suhpeena, may suggest I am not qualified to tell this story. But all court transcripts are at the world’s disposal, all news articles online. This is not the ultimate truth, but it is mine, told to the best of my ability. If you want it through my eyes and ears, to know what it felt like inside my chest, what it’s like to hide in the bathroom during trial, this is what I provide. I give what I can, you take what you need.

In January 2015, I was twenty-two, living and working in my hometown of Palo Alto, California. I attended a party at Stanford. I was sexually assaulted outside on the ground. Two bystanders saw it, stopped him, saved me. My old life left me, and a new one began. I was given a new name to protect my identity: I became Emily Doe.

In this story, I will be calling the defense attorney, the defense. The judge, the judge. They are here to demonstrate the roles they played. This is not a personal indictment, not a clapback, a blacklist, a rehashing. I believe we are all multidimensional beings, and in court, it felt harmful being flattened, characterized, mislabeled, and vilified, so I will not do the same to them. I will use Brock’s name, but the truth is he could be Brad or Brody or Benson, and it doesn’t matter. The point

is not their individual significance, but their commonality, all the people enabling a broken system. This is an attempt to transform the hurt inside myself, to confront a past, and find a way to live with and incorporate these memories. I want to leave them behind so I can move forward. In not naming them, I finally name myself.

My name is Chanel.

I am a victim, I have no qualms with this word, only with the idea that it is all that I am. However, I am not Brock Turner’s victim. I am not his anything. I don’t belong to him. I am also half Chinese. My Chinese name is Zhang Xiao Xia, which translates to Little Summer. I was named summer because:

I was born in June.

Xia is also China’s first dynasty.

I am the first child.

“Xia” sounds like “sha.”

Chanel.

The FBI defines rape as any kind of penetration. But in California, rape is narrowly defined as the act of sexual intercourse. For a long time I refrained from calling him a rapist, afraid of being corrected. Legal definitions are important. So is mine. He filled a cavity in my body with his hands. I believe he is not absolved of the title simply because he ran out of time.

The saddest things about these cases, beyond the crimes themselves, are the degrading things the victim begins to believe about her being. My hope is to undo these beliefs. I say her, but whether you are a man, transgender, gender-nonconforming, however you choose to identify and exist in this world, if your life has been touched by sexual violence, I seek to protect you. And to the ones who lifted me, day by day, out of darkness, I hope to say thank you.

When you know your name, you should hang on to it, for unless it is noted down and remembered, it will die when you do.

—Toni Morrison

In the beginning I was so young and such a stranger to myself I hardly existed. I had to go out into the world and see it and hear it and react to it, before I knew at all who I was, what I was, what I wanted to be.

—Mary Oliver, UPSTREAM

. . . it is our duty, to matter.

—Alexander Chee

I AM SHY. In elementary school for a play about a safari, everyone else was an animal. I was grass. I’ve never asked a question in a large lecture hall. You can find me hidden in the corner of any exercise class. I’ll apologize if you bump into me. I’ll accept every pamphlet you hand out on the street. I’ve always rolled my shopping cart back to its place of origin. If there’s no more half-and-half on the counter at the coffee shop, I’ll drink my coffee black. If I sleep over, the blankets will look like they’ve never been touched.

I’ve never thrown my own birthday party. I’ll put on three sweaters before I ask you to turn on the heat. I’m okay with losing board games. I stuff my coins haphazardly into my purse to avoid holding up the checkout line. When I was little I wanted to grow up and become a mascot, so I’d have the freedom to dance without being seen.

I was the only elementary school student to be elected as a conflict manager two years in a row; my job was to wear a green vest every recess, patrolling the playground. If anyone had an unsolvable dispute, they’d find me and I’d teach them about I-Messages such as I feel when you . Once a kindergartner approached me, said everyone got ten seconds on the tire swing, but when she swung, kids counted one cat,

two cat, three cat, and when the boys swung, they counted one hippopotamus, two hippopotamus, longer turns. I declared from that day forward everyone would count one tiger, two tiger. My whole life I’ve counted in tigers.

I introduce myself here, because in the story I’m about to tell, I begin with no name or identity. No character traits or behaviors assigned to me. I was found as a half-naked body, alone and unconscious. No wallet, no ID. Policemen were summoned, a Stanford dean was awakened to come see if he could recognize me, witnesses asked around; nobody knew who I belonged to, where I’d come from, who I was.

My memory tells me this: On Saturday, January 17, 2015, I was living at my parents’ house in Palo Alto. My younger sister, Tiffany, a junior at Cal Poly, had driven three hours up the coast for the long weekend. She usually spent her time at home with friends, but occasionally she’d give some of that time to me. In the late afternoon, the two of us picked up her friend Julia, a Stanford student, and drove to the Arastradero Preserve to watch the sun spill its yolk over the hills. The sky darkened, we stopped at a taqueria. We had a heated debate about where pigeons sleep, argued about whether more people fold toilet paper into squares (me) or simply crumple it (Tiffany). Tiffany and Julia mentioned a party they were going to that evening at Kappa Alpha on the Stanford campus. I paid little attention, ladling green salsa into a teeny plastic cup.

Later that night, my dad cooked broccoli and quinoa, and we reeled when he presented it as qwee-noah. It’s keen-wah, Dad, how do you not know that!! We ate on paper plates to avoid washing dishes. Two more of Tiffany’s friends, Colleen and Trea, arrived with a bottle of champagne. The plan was for the three of them to meet Julia at Stanford. They said, You should come. I said, Should I go, would it be funny if I went. I’d be the oldest one there. I rinsed in the shower, singing. Sifted through wads of socks looking for undies, found a worn polka-dotted triangle of fabric in the corner. I pulled on a tight, charcoal-gray dress. A heavy

silver necklace with tiny red stones. An oatmeal cardigan with large brown buttons. I sat on my brown carpet, lacing up my coffee-colored combat boots, my hair still wet in a bun.

Our kitchen wallpaper is striped blue and yellow. An old clock and wooden cabinets line the walls, the doorframe marked with our heights over the years (a small shoe symbol drawn if we were measured while wearing them). Opening and closing cabinet doors, we found nothing but whiskey; in the refrigerator the only mixers were soy milk and lime juice. The only shot glasses we had were from family trips, Las Vegas, Maui, back when Tiffany and I collected them as little cups for our stuffed animals. I drank the whiskey straight, unapologetically, freely, the same way you might say, Sure I’ll attend your cousin’s bar mitzvah, on the one condition that I’m hammered.

We asked our mom to take the four of us to Stanford, a seven-minute drive down Foothill Expressway. Stanford was my backyard, my community, a breeding ground for cheap tutors my parents hired over the years. I grew up on that campus, attended summer camps in tents on the lawns, snuck out of dining halls with chicken nuggets bulging from my pockets, had dinner with professors who were parents of good friends. My mom dropped us off near the Stanford bookstore, where on rainy days she had brought us for hot cocoa and madeleines.

We walked five minutes, descended the slope of pavement to a large house tucked beneath pine trees. A guy with tiny tally marks of hair on his upper lip let us in. I found a soda and juice dispenser in the fraternity kitchen, began slapping the buttons, concocting a nonalcoholic beverage I advertised as dingleberry juice. Now serving le dinglebooboo drank for the lady! KA, KA all day. People started pouring in. The lights went off.

We stood behind a table by the front door like a welcoming committee, spread our arms and sang, Welcome welcome welcome!!! I watched the way girls entered, heads tucked halfway into their shoulders, smiling timidly, scanning the room for a familiar face to latch on to. I knew that

look because I’d felt it. In college, a fraternity was an exclusive kingdom, throbbing with noise and energy, where the young ones heiled and the large males ruled. After college, a fraternity was a sour, yeasty atmosphere, a scattering of flimsy cups, where you could hear the soles of your shoes unpeeling from sticky floors, and punch tasted like paint thinner, and curls of black hair were pasted to toilet rims. We discovered a plastic handle of vodka on the table. I cradled it like I’d discovered water in the desert. Bless me. I poured it into a cup and threw it back straight. Everyone was mashed up against each other on tables, swaying like little penguins. I stood alone on a chair, arms in the air, a drunk piece of seaweed, until my sister escorted me down. We went outside to pee in the bushes. Julia and I began freestyle rapping. I rapped about dry skin, got stuck when I couldn’t think of anything that rhymed with Cetaphil.

The basement was full, people spilling out onto the orb of light on the concrete patio. We stood around a few short Caucasian guys who wore their caps backward, careful not to get their necks sunburned, indoors, at night. I sipped a lukewarm beer, said it tasted like pee, and handed it to my sister. I was bored, at ease, drunk, and extremely tired, less than ten minutes away from home. I had outgrown everything around me. And that is where my memory goes black, where the reel cuts off.

I, to this day, believe none of what I did that evening is important, a handful of disposable memories. But these events will be relentlessly raked over, again and again and again. What I did, what I said, will all be sliced, measured, calculated, presented to the public for evaluation. All because, somewhere at this party, is him. U

It was too bright. Blinking, I saw crusty patches of brown blood on the backs of my hands. The bandage on my right hand was already flapping

loose, the adhesive worn. I wondered how long I’d been there. I was lying in a narrow bed with plastic guardrails on each side, an adult crib. The wall was white, the floor polished. Something cut deep into my elbow, white tape wrapped too tightly, the flesh of my arm bulging around it. I tried to wedge my finger beneath it, but my finger was too thick. I looked to my left. Two men were staring at me. An older African American man in a red Stanford windbreaker, a Caucasian man in a black police uniform. I blurred my eyes, they became a red square, black square, leaning against the wall, arms behind their backs, as if they’d been there awhile. I brought them into focus again. They made the face I make when watching an old person descend a set of stairs: tense, anticipating a tumble at any moment.

The deputy asked if I was feeling okay. As he leaned over me his eyes did not waver, did not wrinkle into a smile, just stayed perfectly round and still, two small ponds. I thought, Yeah, should I not be? I was turning my head around looking for my sister. The man in the red windbreaker introduced himself to me as a Stanford dean. What’s your name? Their focus was unnerving. I wondered why they didn’t ask my sister, she must be here somewhere. I’m not a student, just visiting, I said, I’m Chanel.

How long had I napped? I must’ve gotten too drunk, fumbled to the nearest building on campus to sleep it off. Did I crawl? How’d I scrape my hands? Who patched me up with this rinky-dink first-aid kit? Maybe they were a little miffed, another drunk kid they had to look after. Embarrassing really, I was too old for this. Anyway, I’d relieve them of me, thank them for the cot. I scanned the hallway wondering which door was the exit.

They asked if there was anyone they could call, to tell them I was here. Here where? I gave them my sister’s number, and I watched the man in the windbreaker walk away out of earshot, taking my sister’s voice into another room. Where was my phone? I began patting around,

hoping to hit a hard rectangle. Nothing. I berated myself for losing it, I’d have to circle back.

The deputy turned to me. You are in the hospital, and there is reason to believe you have been sexually assaulted, he said. I slowly nodded. What a serious man! He must be confused, I hadn’t talked to anyone at the party. Did I need to get cleared? Wasn’t I old enough to sign myself out? I figured someone would come in and say, Officer, she’s good to go, and I’d give a salute and head off. I wanted bread and cheese.

I felt a sharp pressure in my gut, needed to pee. I asked to use the restroom and he requested I wait because they may have to take a urine sample. Why? I thought. I lay there quietly clenching my bladder. Finally I was given the clear. As I sat up I noticed my gray dress was bunched up around my waist. I was wearing mint-green pants. I wondered where I’d gotten the pants, who had tied the drawstring into a bow. I sheepishly walked to the restroom, relieved to be out of their gaze. I closed the door.

I pulled down my new pants, eyes half closed, went to pull down my underwear. My thumbs grazed the sides of my thighs, touching skin, catching nothing. Odd. I repeated the motion. I flattened my hands to my hips, rubbed my palms along my thighs, as if they’d materialize, rubbing and rubbing, until heat was created, and then my hands stopped. I did not look down, just stood there frozen in my half squat. I crossed my hands over my stomach, half bent over in complete stillness like that, unable to sit, unable to stand, pants around my ankles.

I always wondered why survivors understood other survivors so well. Why, even if the details of our attacks vary, survivors can lock eyes and get it without having to explain. Perhaps it is not the particulars of the assault itself that we have in common, but the moment after; the first time you are left alone. Something slipping out of you. Where did I go. What was taken. It is terror swallowed inside silence. An unclipping from the world where up was up and down was down. This moment is

not pain, not hysteria, not crying. It is your insides turning to cold stones. It is utter confusion paired with knowing. Gone is the luxury of growing up slowly. So begins the brutal awakening.

I lowered down onto the seat. Something was poking my neck. I touched the back of my head, felt rough textures inside knotted hair. I had gone outside briefly, had trees shed from above? Everything felt wrong, but inside my gut I felt a deadened calm. A still, dark ocean, flat and vast. Horror was present, I could feel it moving, shifting my insides, wet and murky and weighted, but on the surface, I saw only a ripple. Panic would arrive like a fish, briefly breaking the surface, flicking into the air, then slipping back in, returning everything to stillness. I could not fathom how I’d found myself in a sterile room, one toilet, no underwear, alone. I would not ask the deputy if he happened to know where my underwear was, because a part of me understood I was not ready to hear the answer.

A word came to me: scissors. The deputy used scissors to clip off my underwear, because underwear has vaginal, has vaginal germs they need for testing, just in case. I’d seen this on TV, paramedics slicing through clothes. I stood up, noticed dirt on the floor. I smoothed out my pants, tying my drawstring into two bunny ears. I hesitated at the faucet, unsure if I was allowed to wash the blood away. So I dipped the tips of my fingers in the narrow stream, touching water into my palms, leaving the dark stains preserved on the backs of my hands.

I returned as calm as I had been before, smiling politely, and hoisted myself back into my crib. The dean said my sister had been informed of my whereabouts, handed me his business card, Let me know if you ever need anything. He left. I held on to this little card. The deputy informed me that the SART building would not be open until morning. I didn’t know what that building was, only understood I was supposed to go back to sleep. I lay flat on my back, but it felt cold and strange, the two of us in the stark lighting. I was grateful I wasn’t alone, but wished he

would read a book or go to the vending machine. I couldn’t sleep while being watched.

A nurse appeared, glanced at me, and immediately turned to the deputy. Why doesn’t she have a blanket?! The deputy said he had given me pants. Well, get her a blanket! Why hasn’t someone given her a blanket? She’s lying there with no blanket! I watched her wildly gesture, demanding more, so adamant about my warmth, unafraid to ask for it. I let it repeat in my head, Somebody get her a blanket.

I closed my eyes again, this time settling into warmth. I was ready to leave this messy dream, to wake up in my own bed, beneath my floral comforter and rice-paper lantern, my sister asleep in the room next to mine. I was gently jostled, opened my eyes into the same brightness, same blankets. A golden-haired lady stood in a white coat, with two other women behind her. They were beaming at me like I was a newborn. One of the nurses’ names was Joy and I took this to be a good sign from the universe. I followed them out the door into a small parking lot. I felt like a frumpy queen, the blanket dragging behind me like a velvet cape, flanked by my attendants. I squinted up at the sky to figure out the time. Was it dawn already? We entered a one-story building, empty. They guided me into an office. I sat in my pile of blankets on a couch, noticed the spines of binders on a shelf labeled SART. In black Sharpie, below it, Sexual Assault Response Team.

So this was who they were. I was nothing more than an observer, two eyes planted inside a beige cadaver with a nest of ratty brown hair. That morning, I would watch silver needles puncture my skin, bloody Q-tips emerge from between my legs, yet nothing would elicit a flinch or wince or intake of breath. My senses had shut off, my body a nerveless mannequin. All I understood was the ladies in the white coats were the ones to be trusted, so I obeyed every command, smiled when they smiled at me.

A stack of papers were set in front of me. My arm snaked out of the blankets to sign. If they explained what I was consenting to, it was lost on me. Papers and papers, all different colors, light purple, yellow, tangerine. No one explained why my underwear was gone, why my hands were bleeding, why my hair was dirty, why I was dressed in funny pants, but things seemed to be moving right along, and I figured if I kept signing and nodding, I would come out of this place cleaned up and set right again. I put my name at the bottom, a big loopy C and two lumps for the M. I stopped when I saw the words Rape Victim in bold at the top of one sheet. A fish leapt out of the water. I paused. No, I do not consent to being a rape victim. If I signed on the line, would I become one? If I refused to sign, could I remain my regular self?

The nurses left to prep the examination room. A girl introduced herself as April, a SART advocate. She wore a sweatshirt and leggings, had hair that looked fun to draw, a volume of scribbly ringlets in a ponytail. I loved her name like I loved Joy’s; April was a month of light rain, the time when calla lilies bloomed. She gave me a lump of brownsugar oatmeal in a plastic cup, I ate it with a flimsy white spoon. She appeared younger than me, but cared for me like a mother, kept encouraging me to drink water. I wondered how she’d awoken so early on a Sunday. I wondered if this was a normal day for her.

She handed me an orange folder. This is for you. Inside were blackand-white xeroxed packets about PTSD, crooked staples, convoluted lists of phone numbers. A pamphlet picturing a girl with an eyebrow piercing, so angsty, so peeved. In purple block letters it said, you are not alone. it’s not your fault! What’s not my fault? What didn’t I do? I unfolded a paper brochure, “Reactions in the Aftermath.” The first category read, 0 to 24 hours: numbness, light-headedness, unidentified fear, shock. I nodded, the similarity striking. The next category read, 2 weeks to 6 months: forgetfulness, exhaustion, guilt, nightmares. The final category

read, 6 months to 3 or more years: isolation, memory triggers, suicidal thoughts, inability to work, substance abuse, relationship difficulties, loneliness. Who had written this? Who had mapped out an ominous future on this crappy piece of paper? What was I supposed to do with this timeline of some broken stranger?

Would you like to use my phone to call your sister? You can tell her you’ll be ready to be picked up in a few hours. April held out her phone. I was hoping Tiffany would still be sleeping, but she picked up immediately. I know her cries; know when she’s dented the car or can’t find something to wear or if a dog has died on television. This crying sounded different, like birds beating their wings inside a glass box, chaos. The sound made my whole body stiffen. My voice became level and light. I could feel myself smiling.

Tiffy! I said. I could not make out what she was saying. This only made my voice calmer, smoothing hers over. Dude, I’m getting free breakfast! Yes, I’m okay! Don’t cry! They think something happened, no, they don’t even know if it’s true yet, it’s all just a precaution, but it’s better if I stay here a little while, okay? Would you be able to pick me up in a couple of hours? I’m at the Stanford hospital. The intern gently tapped me on my shoulder, whispering, San Jose. You’re at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center. I stared at her in misunderstanding. Oh, sorry, I’m at a hospital in San Jose! I said, thinking, I’m a forty-minute drive from home in a different city? Don’t worry! I said. I’ll call you again when I’m ready!

I asked April if she knew how I got here. Ambulance. I was suddenly worried, I couldn’t afford this. How much would the exam cost? The pine needles kept itching my neck like little claws. I pulled out a spiky, auburn fern. A passing nurse gently instructed me to leave it alone, because they still needed to photograph my head. I put it back as if inserting a bobby pin. The examination room was ready.

I stood up, noticed tiny pine cones and pine needles scattered across the cushions. Where the hell was this coming from? As I bent to pick them up, my hair unraveled over my shoulder, releasing more onto the

clean tiles. I got on my knees, beneath my blankets, started pushing the dead pieces into a neat pile. Do you want these? I asked, holding them out in my palm. Can I throw them away? They said not to worry about it, just leave them. I set them down again on the couch, embarrassed by the mess I was making, careless trails over the spotless floors and furniture. The nurse comforted me in a singsong voice, It’s just the flora and the fauna, flora and the fauna.

Two nurses led me into a cold, gray room with a big mirror, morning light. They asked me to undress. It seemed excessive. I did not understand why I needed to reveal my skin, but my hands began removing my clothes before my mind approved the request. Listen to them. They held open a white paper lunch bag and I placed my beige padded bra with the worn straps inside. My gray dress went into another bag, never to be seen again. Something about checking for semen. When everything was gone, I stood naked, nipples staring back at me, unsure where to put my arms, wanting to cross them over my chest. They told me to hold still while they photographed my head from different angles. For portraits I was accustomed to smoothing my hair down, parting it on the side, but I was afraid to touch the lopsided mass. I wondered if I was supposed to smile with teeth, where I should be looking. I wanted to close my eyes, as if this could conceal me.

One nurse slid a blue plastic ruler from her pocket. The other held a heavy black camera. To measure and document the abrasions, she said. I felt latex fingertips crawling over my skin, the crisp edge of the ruler pressed against the side of my neck, my stomach, my butt cheeks, my thighs. I heard each click, the black lens of a camera hovering over every hair, goose bump, vein, pore. Skin had always been my deepest source of self-consciousness, since I began suffering from eruptions of eczema as a child. Even when my skin healed, I always imagined it blotted and discolored. I froze, magnified beneath the lens. But as they bent and circled around me, their gentle voices lifted me out of my head. They

tended to me like the birds in Cinderella, the tape measures and ribbons in their beaks, flitting around taking measurements for her gown.

I twisted around to see what they were photographing and glimpsed a red crosshatch on my rear. Fear closed my eyes and turned my head to face forward again. Usually, I am my body’s worst bully: Your boobs are too far apart. Two sad tea bags. Your nipples are looking in different directions like iguana eyes. Your knees are discolored, almost purple. Your stomach is doughy. Your waist is too wide and rectangular. What’s the point of long legs if they’re not slender. But as I stood stark naked beneath the light, that voice evaporated.

I locked eyes with myself as they continued up, down, around. I lifted the crown of my head, elongated my neck, pulled my shoulders back, let my arms go slack. The morning light melted onto my neckline, the curves of my ears, along my collarbone, my hips, my calves. Look at that body, the nice slope of your breasts, the shape of your belly button, the long, beautiful legs. I was a palette of warm, sandy tones, a glowing vessel in this room of bleached coats and teal gloves.

At last we were free to begin cleaning my hair. The three of us slid the pine needles out one by one, placing them into a white bag. I felt the snags of pieces getting caught, a sharp twinge when threads were plucked off my scalp. Pulling and pulling until the bag was stuffed to the brim with sticks and hair. That should be enough, she said. It was quiet as we pulled out the rest, discarding it onto the floor to be swept away. I blew softly on my shoulders, dispersing the dirt. I worked to untangle a dead needle shaped like a fishbone, while the nurses raked through the back of my clotted head. It felt endless. If they had told me to bow my head to shave it, I would’ve bent my neck with no questions. I was given a limp hospital gown and escorted into another room with what looked like a dentist’s chair. I laid back with my legs spread apart, feet perched on stirrups. Above me was a picture of a sailboat, thumbtacked to the ceiling. It seemed to have been ripped out of a

calendar. Meanwhile the nurses brought in a tray; I’d never seen so many metal tools. Between the peaks of my knees I saw the three of them, a small mountain range, one sitting on a stool with two standing behind her, all staring into me.

You’re so calm, they said. I didn’t know who I was calm relative to. I stared at that little sailboat above me, thinking about it floating somewhere outside this small room in a place so sunny and so far away from here. I thought, This little sailboat has a big job, trying to distract me. Two long, wooden Q-tips were stuck inside my anus. The sailboat was doing its best.

Hours passed. I didn’t like the chilled metal, the stiff heads of cotton, the pills, syringes, my thighs laid open. But their voices soothed me, as if we were here to catch up on life, handing me a cup of neon-pink pills like it was a mimosa. They kept making eye contact, every act preceded by explanation, before insertion. How are you doing, are we doing all right. Here’s a little blue paintbrush, just gonna glaze over the labia. It’ll be a tad bit cold. Did you grow up around here? Any plans for Valentine’s Day? I knew the questions they’d asked me were for distraction. I knew the small talk was a game we were both playing, an act they were cuing me into. Beneath the conversation their hands were moving with urgency, the circular rim of the lens peering into the cave between my legs. Another microscopic camera snaked up inside of me, the internal walls of my vagina displayed on a screen.

I understood their gloved hands were keeping me from falling into an abyss. Whatever was crawling into the corridors of my insides would be dragged out by the ankles. They were a force, barricading me, even making me laugh. They could not undo what was done, but they could record it, photograph every millimeter of it, seal it into bags, force someone to look. Not once did they sigh or pity or poor thing me. They did not mistake my submission for weakness, so I did not feel a need to prove myself, to show them I was more than this. They knew. Shame

could not breathe here, would be shooed away. So I made my body soft and gave it over to them, while my mind bobbed in the light stream of conversation. Which is why, thinking back on this memory with them, the discomfort and fear are secondary. The primary feeling was warmth.

Hours later they finished. April guided me to a large plastic garden shed against a wall. Every inch of it was stuffed with sweaters and sweatpants, smashed against each other in stacks, ready and waiting for new owners. Who are they for, I wondered. How many of us have come in and gotten our new clothes along with our folder full of brochures. A whole system had been set up, knowing there would be countless others like me: Welcome to the club, here’s your new uniform. In your folder you’ll find guidelines that will lay out the steps of trauma and recovery which may take your entire lifetime. The intern smiled and said, You can choose whichever color you like! Like choosing toppings on frozen yogurt. I chose an eggshell white sweatshirt and blue sweatpants.

All that was left was for me to get cleaned up. The detective was on his way. I was taken back to the cold, gray room where I now noticed the metal showerhead in the corner. I thanked them, closed the door. Hung up my hospital gown. Sifted through a haphazard basket of donated hotel shampoos, green tea, coastal breeze, spa sandalwood. I turned the handle. For the first time I stood fully naked and alone, no more cooing sounds or tender hands. It was quiet but for the water hitting the floor.

Nobody had said rape except for that piece of paper. I closed my eyes. All I could see was my sister under a circle of light before my memory flickered out. What was missing? I looked down, stretched out my labia, saw that it was dark from the paint, felt sick from its merlot eggplant color. Tell me what happened. I’d heard the nurses say syphilis, gonorrhea, pregnancy, HIV, I’d been given the morning after pill. I watched the clear water stream over my skin, useless; everything I needed to clean was internal. I looked down at my body, a thick, discolored bag, and thought, Somebody take this away too, I can’t be left alone with this.

I wanted to beat my head against the wall, to knock the memory loose. I began twisting off the caps, pouring the glossy shampoos over my chest. I let my hair drop over my face, scorched my skin, standing among a scattering of empty bottles. I wanted the water to seep through my pores, to burn every cell and regenerate. I wanted to inhale all the steam, to suffocate, go blind, evaporate. The milky water swirled around my feet, streaming into a metal grate as I scrubbed my scalp. I felt guilty; California was parched, stuck in an unrelenting drought. I thought of my home, where my dad kept red buckets beneath every sink, carrying our leftover soapy water to the plants. Water was a luxury, but I stood unmoving, watching gallon after gallon flow into the drain. I’m sorry, I have to take a long one today. Forty minutes must have gone by, but nobody rushed me.

I turned off the faucet. I stood in the fog and silence. My fingertips had withered into pruney, pale rivulets. I smudged the mirror, clearing the condensation. My cheeks were pink. I combed my wet hair, slid my limbs through the cotton sweatshirt, draped my necklace back over my neck, centering it on my chest. I laced up my boots, the only other item I’d been allowed to keep. I stuffed my blue sweatpants inside them, on second thought, untucked them, pulling them over the outside, better. As I shaped my hair into a bun, I noticed a tag dangling from my sleeve. On it a tiny drawing of a clothesline, Grateful Garments.

Every year Grandma Ann (not blood related but our grandmother all the same) made extravagant paper hats out of recycled material; the mesh netting of pears, colored comics, indigo feathers, origami flowers. She sold them at street fairs and donated the proceeds to local organizations, including Grateful Garments, which provided clothes for survivors of sexual violence. Had this organization not existed, I would have left the hospital wearing nothing but a flimsy gown and boots. Which meant all the hours spent cutting and taping hats at the dinner table,

selling them at a little booth in the sun, had gifted me a gentle suit of armor. Grandma Ann wrapped herself around me, told me I was ready. I walked back into the office and sat with hands clasped between my knees, waiting. The detective appeared in the doorframe, neatly cut hair, rectangular glasses, a black coat, wide shoulders, and a nametag that said KIM, he must be Korean American. He stood at the door apologetically, as if this were my home and he was about to enter with muddy boots. I stood up to greet him. I trusted him because he looked sad, so sad that I smiled to assure him I was all right.

He laid down a legal pad, a black rectangular audio recorder, notified me that everything I said would be on record. Of course, I said. He sat with his pen hovering over the page, the little wheels of the cassette rolling. I did not feel threatened; his expression told me he was here to listen.

He had me walk through what type of food my dad served, how much I ate, how many shots, how far apart, brand of whiskey, why I went to this party, time of arrival, number of people at the party, what alcohol was consumed, was it a sealed container, where and when I peed outside, what time I went back inside. I kept looking up at the ceiling as if this could somehow make me think better. I was not used to recalling mundane things so precisely. All the while he was scribbling, giving small nods, working his way down the legal pad, flip, flip, flip. When I arrived at the part about standing on the patio, I watched him write LAST SHE REMEMBERS. His pen clicked off. He looked at me, he was still searching for something. We were going somewhere and then the road cut off. I didn’t have what he needed.

According to the transcripts, all he said that morning was that a couple people saw me passed out, deputies arrived, but I remained unresponsive. He said, Because of the nature of, where you were, and your condition, we always, we have to consider that there was a possibility of some

type of sexual assault. The nature, your condition. He said when the investigation was done, the man’s name and information would become public record. We don’t know exactly what happened yet either, he said. Hopefully nothing. But, worst-case scenario, we have to work off of that. All I heard was, Hopefully nothing.

CHANEL : Um, do you know where it was exactly that they found me?

OFFICER : Okay. In between there and the house, there’s a little area, um, I believe it’s a dumpster. Not in the dumpster.

CHANEL : Yeah, no.

OFFICER : No, but the area behind.

He said, Some people passing by saw you were there, and they’re like, “Wait, that doesn’t look right.” And then they stopped, um, they saw someone . . . and then another person came by, saw you. And called, called us . . . Um, naturally in the beginning, um, we assume a possible rape.

I didn’t understand. How’d I get outside? What didn’t look right? The detective shifted in his seat, and I caught a slight wince as he said, Did you hook up with anyone? This struck me as a weird question. I said no. So no one had permission to touch you anywhere. The way he looked sorrowful, like he already knew the answer. I felt my body stiffen. I said, They caught him like, like last night right? Were they trying to escape?

He said, So now we just have to make sure that this is the right person, so was this the person that was doing something to you, or trying to do something to you? Um, but someone was acting really hinky around you. Hinky. I’m trying to be cautious to say that this person is the person. According to the penal code, we can arrest someone based on probable cause, since rape is a felony, we can arrest someone based on probable cause to believe that a felony occurred. Even if it didn’t occur.

There was subtext that something grave had happened, but every

sentence was capped off with an alternate scenario where I was left untouched. Even if it didn’t occur. Doing or trying. Hopefully nothing. Hinky. I had a foothold in two different worlds; one where nothing happened, one where I may have been raped. I understood he was withholding information because the investigation was still pending. Maybe he also saw that my hair was dripping and I was wearing the wrong clothing. Maybe he was thinking about my sister, who was about to arrive.

Detective Kim said tomorrow I might remember more, he’d give me his card. I nodded, but knew I’d given him all I had. He said I’d be able to pick up my phone at the police station later that evening. Behind him, my sister appeared, hunched up, face drained. The victim in me vanished as I became the older sister. On the tape at the end of my interview you can hear her arrive:

I said, Hey.

Oh my god.

Hey.

Oh my god.

I’m so sorry.

Oh.

I made you worry.

No, it’s okay.

Oh, sorry.

She said, Don’t apologize.

I was upright, unshakable, I was the adult showing her that the other strangers in this room were kind, you could talk to them. April was pouring her water, pulling up a chair. Tiffany could not stop crying. As the detective began questioning, my eyes stayed on her. She was talking through the same drinks, names of friends, atmosphere of party. She mentioned there’d been a blond guy that kept putting his face in hers, touching her hips, following her around. All her friends started avoiding him. She said she thought it was weird the guy never said anything,

just stared with large eyes as he leaned in. She said she started laughing from discomfort and as a result their teeth hit.

She said she’d left me briefly to take care of a sick friend, thinking I’d be fine on my own. When she returned police were clearing out the party. She asked two students who’d been manning the door, What’s going on, and they told her the party had been shut down due to a noise complaint. She asked a policeman in the parking lot and he said he couldn’t say. She assumed I’d left to meet up with friends in downtown Palo Alto. Still she wandered around asking, Have you seen a girl who looks like me? She and Colleen swung open every door of the fraternity, mad and then worried when I never picked up my phone. They yelled my name into the trees, while I was being carted out the side on a gurney, disappearing into the boxy white vehicle.

Students stopped him, I said. Cool, right. That morning, I understood bystanders had seen a man acting peculiar, had pursued him in a chase. I was unaware any physical contact had been made. I did not know this man had touched me beneath my clothes, had no idea that any of my body parts had been exposed. I told myself the crisis had been averted, the bad guy had been arrested, and now we were free to leave. The detective thanked us. We would go to the Stanford police station in the evening to pick up my phone. The white-coated ladies surrounded me in a hug, a tight hold, then release.

The sun was out now, harshly reflecting off sparse cars in the lot. What a surreal Sunday morning. How nuts was that? That was like the nuts-est thing to have ever happened. They stuck so much stuff into my hoo hoo. I can’t even—like look at what I’m wearing. How sick is this outfit? I was modeling my slicked-back hair, my oversized sweat suit, strutting a walk, a little spin. Tiffany was still teary-eyed, her breathing uneven, hiccuping her laughs.

We sat in the car, stared at a chain-link fence, she was waiting for me to tell her where to go. She was still visibly shaken. I wasn’t thinking

about who he was, or how I felt, or where the photographs would end up. All my thoughts wrapped around her, my baby sister, for whom I’m supposed to have the answers.

Holding it together for her was what I’d been trained for. One time she became ill on a plane, lurching forward, and I held out my hands to catch her vomit before it could hit her lap. When my grandma crumbled blue cheese over our salads, Tiffany pinched her nose, and I’d wait for my grandma to turn around before shoveling her cheesy leaves into my mouth. After we watched E.T. she slept in my bed every night for the next seven years, terrified of that dehydrated alien and his wrinkly finger. When people kissed in movies I held a pillow in front of her face, Inappropriate, you’re too young. I wrote and redrafted persuasive essays that convinced my parents to get us Nokia cell phones. At every class party, I’d wrap half of my donut or snickerdoodle in a napkin so I could deliver it to her at recess. When I loved horses, I tied her to a chair with a dog leash, called her Trinity, put a bath mat on her back like a saddle, brushed her hair, and made her eat Cheerios out of my hand. I still remember when my parents found her in her “stable.” If you want to play, you have to be the horse, my parents said. You sacrifice for her, you protect her from aliens, you eat the blue cheese. I understood that was the first and most important job I had.

But I was not ready to go home to my parents. I needed time to think. Tiffany and I were old enough to have the freedom to come and go; not coming home meant we’d stayed at a friend’s house, no reason to worry, our neighborhood safe. I understood I couldn’t tell them I woke up in a hospital, covered in vegetation, because someone was acting hinky, and have them accept that information. But it’s okay, I would say. It’s not okay, they would say. My dad would say who and where and why and how. My mom would make me lie in bed and drink a heated concoction with ginger. When you tell your parents, there is fuss. I did not want fuss. I wanted everything to go away.

I was convinced the police would tell me a man tried to do something but did not succeed, we apologize for the inconvenience. In fact, I was so sure that this was all an error, that when my sister asked if I was going to tell our parents, I said, Maybe in a few years. I imagined one day dropping it casually into a conversation at dinner. Did you know one time I was almost assaulted? They’d say, Oh, I’m so sorry, I never knew that happened to you. Why didn’t you tell us? I’d say, Well, it was a long time ago, it turned out to be nothing really, and I’d wave my hand and ask them to pass the string beans.

Sitting in that parking lot, the only place I could think to go was In-N-Out. It was ten in the morning, early for burgers, but In-N-Out was different. We’d treated the white-tiled interior like a church growing up. It was where we gravitated when one of us was upset or celebrating or heartbroken. All that salt and sauce always made me feel better. But by the time we arrived, I felt embarrassed in my clothes and requested that we do drive-through. We ordered our burgers and pulled over to eat. I took one bite but didn’t taste the sauce. I slipped the burger under its wrapper and set it down by my feet. I had killed enough time. By now we knew the house would be empty, Dad out running errands, Mom with friends, off on their regular Sunday routines.

My dad is a retired therapist, who had worked six days a week, twelve hours a day, listening to people. All the money that has housed and fed us comes from guiding people through stories we will never hear. My mom is a writer who has authored four books in Chinese, which means her books are ones I cannot yet read. As open as my parents are, much of their lives are unknowable to me.

After two decades of private practice, my dad said he has heard every scenario you could imagine. Having grown up during the Cultural Revolution in rural China, my mom has seen every atrocity you could see. They both understand that life is large and messy, that nothing is black and white, there is no such thing as a linear trajectory, and at the end of

the day it is a miracle just to wake up in the morning. They were married at the only Chinese cultural center in Kentucky, an attractive, unlikely pairing.

None of our furniture matches. Our towels are not plush and white, but worn, featuring Scooby-Doo. When we have guests over for dinner parties, Tiffany and I hide all the books and deflated basketballs and lotion samples until everything is spotless. We aim to emulate the polished sheen of our friends’ houses. But afterward, it’s as if the house can unbutton its pants, release its gut, all of our items pouring out again.

My home is a place where everything grows and all spills are forgiven, where anyone is welcome at any time of day. My family is four planets orbiting in the same small universe. If we had a slogan it’d be, Feel free to do your own thing. Home is unconventional. Home is warmth. Home is closeness while maintaining independence. Home is where darkness could not get in. I was determined not to let it.

As we pulled into the driveway, my sister’s phone rang with a call from the detective. She passed it over. Would you like to press charges? he said. What does that mean? I asked. He said he wouldn’t be able to tell me much about the process, that it was more in the district attorney’s department. He said that the department was already legally inclined to press charges, but it was up to me whether I wanted to participate. He said it would make things easier for them if I did, but that I did not have to. I asked if I could have a minute to decide, that I would call him back. I hung up and turned to my sister. I had nobody to ask, and Tiffany had no idea. Should I? Yeah, right? Maybe I shouldn’t. But they are anyway, so I might as well, I mean, what is? How can? I sat and looked around, stumped. I’m probably supposed to, right? If they are. At the time I figured it was equivalent to signing a petition, a little stamp of affirmation, saying I endorsed the police’s decision to pursue this case. I was afraid that if I said no, it would mean I was on the stranger’s side. Court hadn’t even crossed my mind, was nothing more than an obscure, dramatic

showdown that happened on television. Plus, the guy was already in jail. If it turned out he did nothing, he’d be let go, otherwise he’d stay and serve time. They had all the evidence needed to make the conviction. This was just a formality. I called him back. Uh, yes. Yes, I will. Thanks.

I didn’t know that money could make the cell doors swing open. I didn’t know that if a woman was drunk when the violence occurred, she wouldn’t be taken seriously. I didn’t know that if he was drunk when the violence occurred, people would offer him sympathy. I didn’t know that my loss of memory would become his opportunity. I didn’t know that being a victim was synonymous with not being believed.

Sitting in the driveway, I didn’t know this little yes would reopen my body, would rub the cuts raw, would pry my legs open for the public. I had no idea what a preliminary hearing was or what a trial actually meant, no idea my sister and I would be instructed to stop speaking to each other because the defense would accuse us of conspiring. My threeletter word that morning unlocked a future, one in which I would become twenty-three and twenty-four and twenty-five and twenty-six before the case would be closed.

I walked down the hall to my room, told my sister I’d be out soon. I locked the door and took another shower, washing the hospital off me. She set up the pullout couch in the living room, turned on the TV. I laid down next to her. As I did, her arm rested on me like a paperweight, as if she was worried I’d blow away. The TV droned on, the afternoon sun dissolving through the living-room windows, our parents walked up and down the hall, as we drifted in and out of sleep. We’d gone to the party together and we’d been separated, and now we were together again, but not the same.

When night fell, we emerged, told our parents we were going to get ice cream. I regret this, because when I get ice cream now, my mom eyes me, and I have to say, I promise, real ice cream.

First we picked up Julia, who was studying in the library on campus. She and Tiffany had been friends since their little teeth had been notched up with braces. Julia was always lively, but when I pulled up, she looked shaken.

As I looked at the two of them in my car, it weighed on me that my secrecy had become theirs. I understood this was not how we were supposed to be handling things. If Tiffany was ever in a hospital, I would want my parents to know. But I was in a strange position. When asked, Why didn’t you tell your parents? I ask, Why didn’t anyone tell me? I needed to keep the story in my control until I knew more.

The parking lot was quiet, dark. I’d passed this building many times before. It was small, surrounded by a moat of tanbark and stocky shrubs, moths ricocheting off the outdoor lights, lines of white illuminated thread. The door buzzed and we were let into dingy halls covered in corkboard bulletins and fliers. Detective Kim was not there. Instead I was introduced to a deputy wearing a windbreaker; she had olive skin, and thin black hair nearly down to her waist. I followed her into a small room, where a notepad and audio recorder sat on the table, while Tiffany and Julia waited in a room down the hall. I thought she’d tell me what happened with the man, hand me my phone, and wish me well. But the door was closed, blinds pulled down. The questions began again, asking me to recall every trifling detail from the previous night, even more precise this time. The transcript of our conversation would come out to seventy-nine pages. It felt tedious and redundant and I could not understand the significance of what I was saying or how it would come into play.

A knock, another deputy, tall in an acorn-colored uniform, thick mustache, black belt full of black shapes. He looked stern and weary, said he was glad to see that I was okay. The way he said it made it sound like a miracle, like I had died and come to life. He told me that one of the guys who had found me had paused while speaking to cry and catch

his breath. The sergeant said he almost choked up too. Grown men are crying, I thought. What the hell happened.

The female deputy pulled my phone out of a large envelope. The blue case was covered in dirt, a crisp, brown border caked along the edges, as if my phone had been buried and then unearthed. I had dozens of missed calls and texts from Tiffany and Julia, Where are you, I’m scared. The deputy asked me to email her all the photos I’d taken that night. There was one of me holding a red cup, eyes deliberately crossed . Why couldn’t I have smiled normally, just this once. I sent her photos and screenshots of everything, unaware they’d all be filed as evidence. She gave me the opportunity to ask questions. According to transcripts I said, Um, they said that something had happened to me. I didn’t really understand what that meant. I still real— , don’t really understand what it means.

She said she hadn’t been fully briefed yet. She said I’d been found by two Stanford students, said no more. So I asked her why the man ran. She told me because something didn’t look right. I was trying to get closer to the crime scene, edging toward the commotion of parked police cars and yellow tape. But every time I stepped closer, she stepped in front of me. When I stepped to my right, she sidestepped. I craned my neck to try to see what they were hiding, but it was no use, the area off-limits. I was to remain behind some unspoken line.

Here’s what I did understand. The rooms I walked into, the air changed. People’s expressions darkened, they used indoor voices. They approached me with hesitancy, like an animal they didn’t want to spook. They scanned my face for something, and I’d look blankly back in return. And all of them said they were impressed to see how well I was doing. She said, I have to say, you are very calm, you’ve very . . . Are you usually that way? I nodded, said that when my younger sister was present, I downplayed my emotions. Still they seemed perplexed by my composure; it seemed, given the circumstances, I should be reacting some other way entirely, and this unnerved me.

I explained that I hadn’t told my parents. That’s understandable, she said. You know, you’re trying, I think you’re trying to save your parents emotionally . . . until you can . . . kinda get a better grip of what happened and occurred. She was very kind, validating my feelings, but she redirected all my questions.

Before the interview ended I made two things clear:

1. No one was to contact my parents until I understood what happened.

2. I never wanted to see or be in contact with whoever this man was again.

I was led into a waiting room with dusty trophies while Tiffany went in for her interview. The deputy typed up the following notes:

One of the other guys was a quiet guy, who did not speak. Colleen and Tiffany thought he was weird because he was aggressive. Tiffany described him to be about 5’11 to 6’0 tall. He had blond curly hair, and blue eyes. He appeared clean shaven. He wore a baseball cap backwards. He had on pants, not shorts. She could not remember what kind of shirt he wore. She thought he looked like one of her friends from college. The aggressive guy was giving out beers. And one point, he came up to Tiffany and started making out on her cheek. Then he went in for her lips. She laughed in shock. Colleen, and Julia saw it happen, and also laughed. The guy left. Then a short time later, while Tiffany was talking face to face to Colleen, the aggressive guy came back. He stepped between her and Colleen, and tried to make out with Tiffany again. He grabbed her from in front, at her lower waist, and kissed her on the lips. She told him she had to go, and wiggled out from his hold.

When we got home, Tiffany went inside while I sat in the car. I realized my boyfriend, Lucas, would be wondering why I’d been mute all day. He lived in Philadelphia and we’d been dating for a few months.

He picked up after the first ring. I was worried about you last night, he said. Did you make it home okay?

I was unaware I’d even called him. I scrolled through my phone log, found his name buried in my missed calls. I had phoned him around midnight, woken him up at 3:00 a.m. his time. Did you find Tiffany? He asked. I was worried you’d wake up in a bush or something. My stomach hardened. He knew? How could he know? What do you mean? I said. He said by the end of our conversation I wasn’t speaking English, that I kept rambling gibberish. Every time there was a pause in my speech, he would yell into the phone to go find Tiffany, but I never responded. He knew I’d been alone, incapacitated. I felt myself sinking. You left me a voice mail, he said. You sound obliterated. I said, Don’t delete it. Promise me you won’t delete it?

Is everything okay? You sound sad, he said I nodded, as if he could hear this. Just sleepy, I said. I went inside, stripped my iPhone of its dirty case, but didn’t wash it. I folded my sweat suit, tucked it into the back of my drawers. I slid my orange folder onto my shelf, my hospital bracelet clipped off and tucked inside it. I had a strange desire to preserve everything, artifacts that proved the existence of this alternate reality.

The next day was Martin Luther King Day, the last day of the long weekend. Before Tiffany drove back to school, I wanted to show her this was not a time to disengage or distance ourselves, we had to stay close to Mom and Dad. I proposed we go out for dinner. We stood waiting to be seated, next to red paper decorations, a bowl of melon candies, a tank full of frowning fish. We ordered an entire Peking duck. As always, my mom prepped us with a demonstration; lay out the circular bun, spread a dollop of plum sauce, add a crispy morsel of crimson duck meat, a few sprigs of green onion and cucumber stalks, wrapping it all up. Mom is rolling duck blunts. Mom, Mom look, Quack Kush. After dinner, my sister drove the two hundred miles back to school, through stretches of flatland,