THE PHILOKALIA

Andrew Louth is Emeritus Professor of Patristic and Byzantine Studies in the Department of Theology and Religion at Durham University.

Jonathan L. Zecher is a Senior Research Fellow in the Institute for Religion and Critical Inquiry at the Australian Catholic University.

The Philokalia

A Selection

Translated by Jonathan l . Ze C her and a ndrew l outh with

an Introduction by a ndrew l outh

Penguin Books

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK

One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7B w penguin.co.uk

First published in Penguin Classics 2025 001

Translation copyright © Jonathan L. Zecher and Andrew Louth, 2025

Introduction copyright © Andrew Louth, 2025

The moral right of the editors and translators has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10.25/12.25pt Sabon LT Pro Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 Y h 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library is B n : 978–0–241–20137–4

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Contents

Introduction vii

Preface to the Translation xix

Liturgical Hours and Offices xxv

SELECTIONS FROM THE PHILOKALIA OF THE HOLY ASCETIC FATHERS

St Nikodemos of Athos, Introduction to This Book 3

Evagrios Pontikos, One Hundred and Fifty-Three Chapters on Prayer 13

St Mark the Solitary, Letter to Nicholas 34

St Diadochos of Photiki, One Hundred Gnostic Chapters 52

St Maximos the Confessor, Four Hundred Chapters on Love 102

St Maximos the Confessor, Commentary on the Lord’s Prayer 167

Anonymous, A Discourse on Abba Philemon 190

St Symeon the New Theologian, One Hundred and Fifty-Three Practical and Theological Chapters 206

Ps-Symeon, Methods of Holy Prayer and Attentiveness 252

Introduction

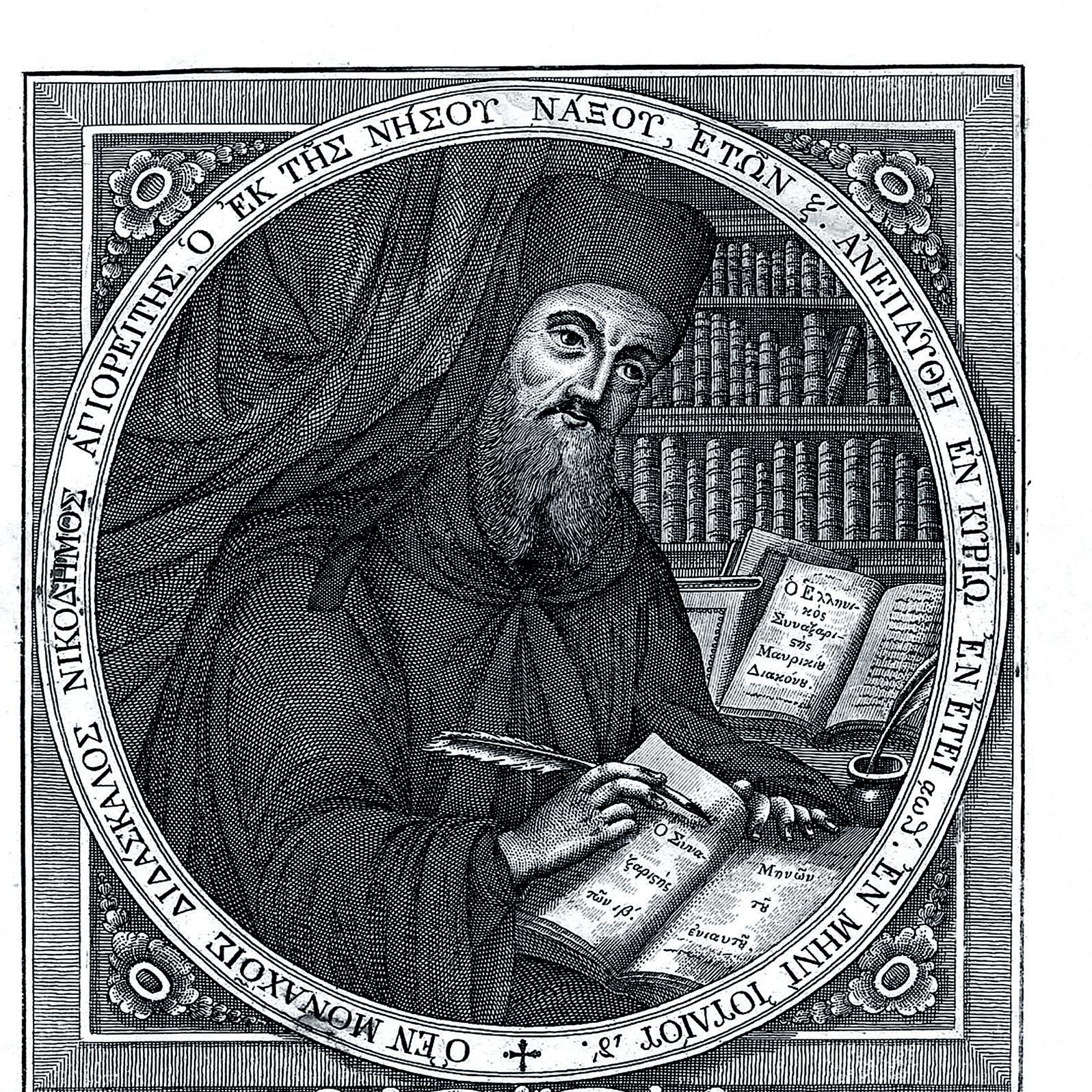

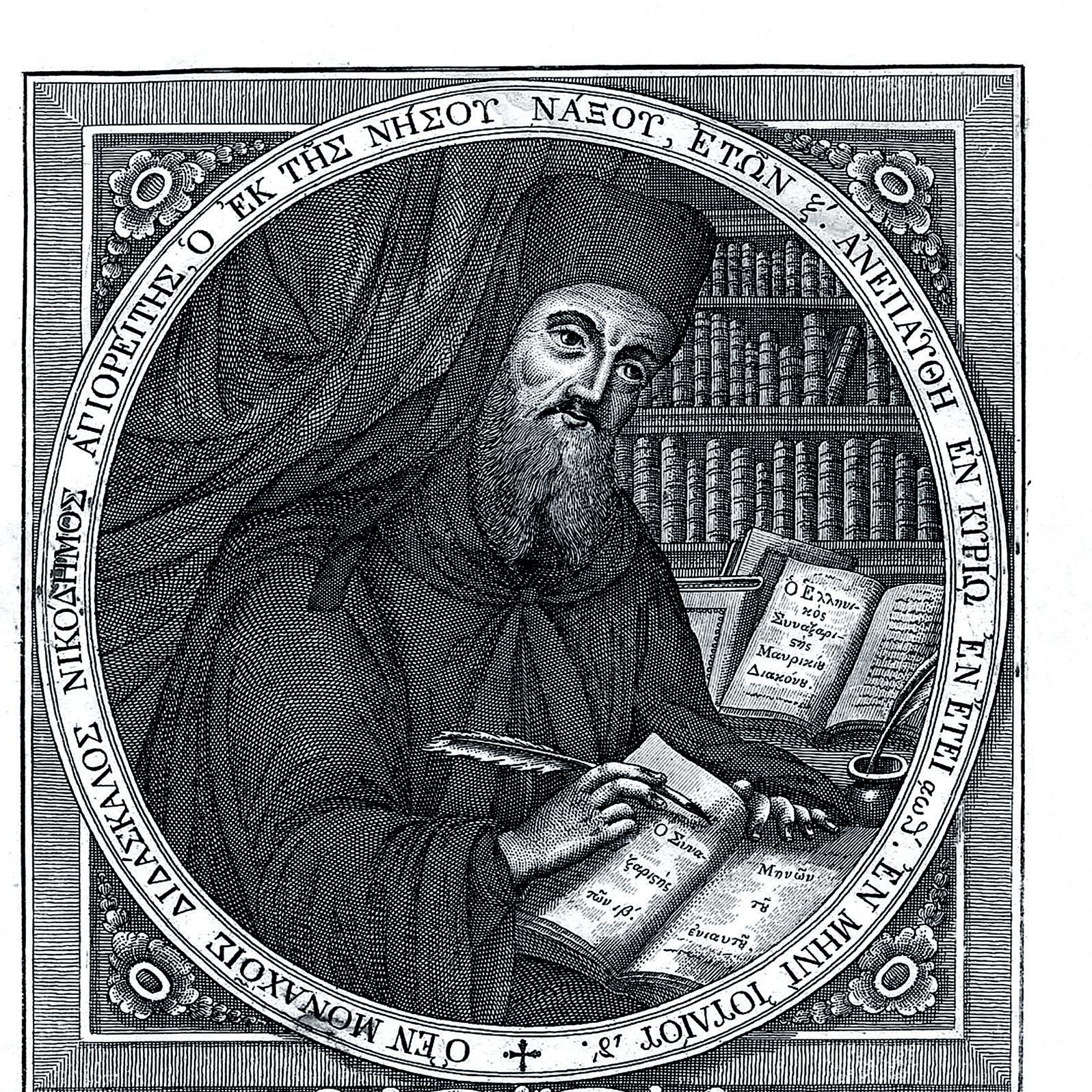

In 1782 there was published in Venice the Philokalia of the Holy Ascetic Fathers. It appeared in two folio volumes, continuously paginated and usually bound together, consisting of an anthology (which is what philokalia means in Greek, though etymology suggests ‘love of the beautiful’) of works of ascetical and mystical theology from the fourth to the fifteenth century – more than a millennium of monastic literature. The only names mentioned on the title page of the book are John Mavrogordatos, a wealthy Greek philanthropist who provided the funds for the publication of the collection, and Antonio Bortoli, the Venetian printer and publisher. Nevertheless the Philokalia is indelibly associated with two other names: Nikodemos, a native of Naxos and for most of his life a monk of the Holy Mountain of Athos until his death in 1809 (and thus called Nikodemos the Hagiorite, or Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain), declared a saint in 1955, and Makarios, a native of Corinth, briefly its bishop, a position he lost as a result of the Russo-Turkish war of 1768, after which he was confirmed in 1773 as a bishop, with a stipend but without a see, by the Sultan, and spent the rest of his life in various islands of the Aegean, much sought after as a teacher, and canonized by popular acclaim by his fellow Corinthians shortly after his death in 1805.

Both men, Nikodemos and Makarios, were associated with revival movements in Greece, as the Greeks started to flex their muscles and move towards independence from the Ottoman Empire, which they achieved (or, rather, began to achieve) in 1821. These movements involved the emergence of a national consciousness, the encouragement of Hellenism through teaching

and the establishment of schools, as well as a religious revival, which sought to restore authenticity to the practice of Orthodox Christianity, especially Orthodox monasticism, which had been damaged during the years from 1453 of the Tourkokratia, the ‘Turkish Yoke’. Orthodox Christianity, or ‘Orthodoxy’, is the version of Christianity practised for centuries in Greek, Arab and Slavic lands, and now globally. But it traces its roots to the earliest Christians via the history and Christian culture of the Eastern Roman – ‘Byzantine’ – Empire. It was within that world that Christian monasticism began and all of the authors of the Philokalia lived, prayed and died. The movement to restoring and purifying Orthodoxy in the nineteenth century meant recovering its roots in early and Byzantine Christian life, available through the long memory of liturgy and communal life, and, in this case, in the written monuments of unageing intellect.

The Philokalia is a shining beacon of this religious revival. But it does not stand alone: Nikodemos was tireless in preparing the ground for the renewal of Orthodoxy in Greece, to be independent of the political and religious authority of the Ottoman Empire; he put together a work called the Pedalion (the ‘Rudder’), a compilation of the Holy Canons (the legal code of the Orthodox Church) together with his own commentary; expositions of the meaning of the festal hymns of the Orthodox services; and a host of works of spiritual theology – guidance for the Christian life, especially the importance of frequent communion. Although his purpose was a kind of harvest of the Greek Orthodox tradition, he also drew on the spirituality of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, not least the Jesuits.

The contribution of the two men to the Philokalia remains unclear: the work itself is anonymous and, though the names of both men are associated with the work, what role each one played is a matter of conjecture – conjecture apparently affected by the rise and fall of the esteem in which they were individually held. After the canonization of St Nikodemos in 1955, modern scholars, writing in response to and celebration of this event, tended to attribute at least the scholarship displayed in the work to Nikodemos, but in the celebrations following the second centenary in 2005/6 of Makarios’s death and canonization it is

Makarios’s role that has been in the ascendant. It looks likely that Makarios provided the support for the project, eliciting from John Mavrogordatos the funds necessary for the publication of the final work in Venice (there, since in the Ottoman Empire there were no presses authorized to publish religious works in Greek script), and may well have had a say in the selection of the texts included in the Philokalia, while Nikodemos was involved in putting them together, providing introductions to each of the writers included, as well as the introduction to the volumes as a whole. Mavrogordatos is a rather shadowy figure, though a member of a prominent Greek family in Constantinople, with a long history of intellectual and cultural patronage. He was a layperson (not a monk or priest) and devoted to Orthodoxy.

Presenting the texts of the Philokalia in chronological sequence has the effect – surely intended – of demonstrating the traditional character of hesychast spirituality, as it emerged from the controversies of the fourteenth century. ‘Hesychast’ spirituality is a way of life – especially the monastic life – that sets great store on the acquisition of quiet and tranquillity (for which the Greek is hesychia ) in which prayer might become possible. The use of the term hesychia goes back to the beginnings of Christian (and indeed non-Christian) attempts to live a life centred on prayer. By the beginning of the second Christian millennium, there had grown up a considerable body of advice on living such a life of prayer and quiet (many such texts are included in the Philokalia ), and also claims for the efficacy of this way of life: claims that monks who persisted in their solitary prayer could come to see the uncreated light of the Godhead, and in beholding that light be irradiated by it and transfigured – claims dismissed by the opponents of hesychasm, in the controversy that arose in the first part of the fourteenth century, as self-deluding hallucination. In this sense, the Philokalia might be understood as a monumental statement of what tradition is and how one finds one’s place in it.

Many of the monks who pursued hesychast prayer in this way belonged to the monastic republic settled on a narrow peninsula, reaching out south-east of Thessaloniki into the Aegean, and dominated by Mount Athos; they found their champion in

St Gregory Palamas (c.1296–1359), himself for a time an Athonite monk, and later Archbishop of Thessaloniki, to the diocese of which the Athonite peninsula belonged, who defended transfiguration into the uncreated light of the Godhead as the final end of a process of deification or divinization, in which the human person was restored to the original state in which God had created him in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen. 1:26–7). Furthermore, Palamas’s defence of hesychasm went beyond simply establishing the legitimacy of hesychasm as a devotional practice; for him it meant seeing prayer as a lifetransforming engagement with God, in which the human is transfigured into the divine (‘deification’) without breaching the utter transcendence of the uncreated God over his creation, including the human creation, brought into being out of nothing. This theological vision was seen as entailing a distinction within the uncreated Godhead between his essence and his activities or operations (between his ousia and his energeiai ), as well as seeing the human person and the created cosmos as mutually informing each other in the ultimate reality of the Incarnate Christ – something manifest in the way in which the reality of every creature, its logos or principle, is grounded in the Logos or Word of God, incarnate in Christ. The lineaments of this vision of the ultimate coinherence of God and his creation were first traced by the great seventh-century theologian St Maximos the Confessor, who – after Palamas – is granted most space in the selections that make up the Philokalia.

This amazing vision of the ramifications of Christian belief in a God who creates all that is out of love, and who also, out of love, identifies himself with his creation through the Incarnation of the Word of God to the point of experiencing death on the Cross, is worked out by St Maximos in a way that draws on all the resources of patristic or Byzantine theology – Scriptural exegesis, liturgical experience growing out of the centrality of the Eucharist or divine Liturgy, the experience of prayer, the philosophical insights of the Greek tradition, beginning with Plato and Aristotle and reaching its speculative heights in Neoplatonism, an understanding of what it is to be human implicit in ascetical and mystical experience – and Maximos’s vision is

lent even greater power by the cumulative experience of Byzantine monasticism.

The selection of treatises, made by Sts Nikodemos and Makarios, traces adumbrations of this vision in early writers of the fourth and fifth centuries, such as Evagrios of Pontos, Diadochos of Photiki and Mark the Monk, leading quickly to a series of treatises by Maximos the Confessor, then to monks associated with the Monastery of the Burning Bush (now the Monastery of St Catherine) at the foot of Mount Sinai, with whom is associated a remarkable but otherwise unknown thinker, Elias Ekdikos. Then there follows a single long work by Peter of Damascus, itself a kind of philokalia or anthology of notable texts. He is followed by Symeon the New Theologian, represented by a short homily, an inauthentic popular work on three ‘methods’ of prayer, and a composition in the form of 153 chapters drawn from Symeon the New Theologian and his mentor, Symeon the Elder (or, ‘the Pious’): a brief interlude, overshadowed by the three Gnostic Chapters of the one to whom Symeon the New Theologian had entrusted his spiritual legacy as his biographer and editor, Nikitas Stithatos. We then enter into the heart of the hesychast controversy with writings by Gregory Palamas himself, preceded by his mentors, Theoliptos of Philadelphia and – at greater length – Gregory of Sinai. The works of Palamas in the Philokalia mostly display his skill as a spiritual father and guide; nevertheless they include the Hagioretic Tome, a statement and defence of the hesychast position, and Palamas’s summary of the philosophical basis of hesychasm in One Hundred and Fifty Philosophical Chapters. After Palamas we find a collection of works composed, no longer in the heat of the hesychast controversy, but in the decades following, when the assured doctrine of hesychasm could be ‘recollected in tranquillity’ – mostly, and confusingly, by authors called ‘Kallistos’.

Anthologies are curious creations, and it is not always clear how to approach them, especially one so massive and apparently (though not actually) comprehensive as the Philokalia. How did Makarios and Nikodemos expect it to be read? Their title suggests a highly aspirational aim: Philokalia of the

Watchful Elders, Gathered from Our Holy and God-Bearing Fathers, in which the Intellect is Purified, Enlightened, and Perfected through Moral Philosophy in Action and Contemplation. This lengthy description is not unusual for an early modern title, and it tells us how its compilers hoped it would be read: as a resource and mirror for readers’ own progress in prayer, contemplation and, as we will see below, deification. Yet they cannot have imagined that people would sit down and read the Philokalia cover to cover, all one thousand, two hundred and six double-columned pages. Probably, it was intended – as is this selection – for more limited, thoughtful forays. Readers might choose one author or another and read, pray, meditate, ponder, slowly, and without hastening to the next thing. There is no right order, no single method, for reading the Philokalia, and we hope that readers will find their own way into this anthology.

A thread that becomes increasingly manifest with the passage of time is a way of praying based on the use of the Jesus Prayer: ‘Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner’. The earliest references are tantalizing in their allusiveness – the prayer ‘Lord Jesus’, mentioned by Diadochos, for example – but gradually there emerges the prayer in its recognizable form, accompanied by breathing techniques to hold the one praying in the presence of God. The Philokalia itself, then, ranges from simple practical instruction in the Prayer of the Heart through the use of the Jesus Prayer – several of the most concise and practical works, including the Three Methods of Prayer, attributed to Symeon the New Theologian, and Mark of Ephesos’s brief commentary on the Jesus Prayer, are contained in a kind of appendix, outside the chronological sequence of works in Byzantine Greek, in a more accessible modern Greek (‘demotic’) translation – to works of real philosophical density, such as the works of Maximos the Confessor, and indeed Gregory Palamas himself. Both simple practical instruction in prayer and some indication of the philosophical complexities that underlie such prayer (but which the one praying does not himself need to understand) are to be found in the Philokalia – or at least in the Greek Philokalia of 1782, for the selection of texts found

in translation into Church Slavonic (by St Paisy Velichkovsky) and later into Russian (by St Theophan the Recluse), called the Dobrotolyubie, fights shy of the more intellectually demanding texts: the Church Slavonic version including nothing by either Maximos or Palamas, while the Russian version includes only the shorter pieces by Palamas.

Although this volume draws only on the Greek Philokalia, a word is necessary about the Slavonic and Russian versions called the Dobrotolyubie, a kind of chiastic calque of philokalia (with no independent meaning in the Slav languages, unlike philokalia, which means, we have already noted, an ‘anthology’): that is, dobro = kalos, meaning ‘good’, while lyubie = phil-, meaning ‘love’ or ‘affection’. The natural inference is that the Dobrotolyubie is a translation of the Philokalia, but the truth is more complicated. Indeed, the project of seeking out authentic monastic texts and translating them into Slavonic (and Romanian) began quite independently of the similar harvesting of monastic texts that culminated in the Philokalia of 1782, and is to be associated with the name of a Moldavian monk, St Vasile of Poiana Mărului. One of St Vasile’s disciples was St Paisy Velichkovsky, whose collection of monastic texts, called the Dobrotolyubie, is to be regarded as parallel with, rather than dependent on, the texts that came to form the Philokalia (the use of the calque Dobrotolyubie as its title was deliberate and probably an attempt to claim the authority of the Greek collection, published eleven years ahead of St Paisy’s Dobrotolyubie, to meet Paisy’s reluctance to publish a printed version of such texts at all). Furthermore, when we come to consider the influence of the Philokalia, this was not direct – the second edition of the Greek Philokalia did not appear for over a century, when it was published in an edition of five volumes in Athens in 1893; rather, the influence of the Philokalia was spearheaded by the Slavonic and Russian versions, which formed part of a monastic revival, as well as the revival of spiritual fatherhood (starchestvo ), in the course of the nineteenth century, assisted by a popular work that has come to be known as The Way of a Pilgrim, which achieved enormous popularity in the twentieth century – indeed through its figuring as the

‘small pea-green clothbound book’ carried by Franny in her handbag in J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, it acquired something of a cult status in the 1960s.1

The relationship between the Greek Philokalia of 1782 and the Slavonic and Russian versions of 1793 and 1877–89 is perhaps better expressed as a family resemblance rather than a simple dependence through translation – and the same is true, in an analogous way, of the relationship between the 1782 Philokalia and the later Greek editions of 1893 and 1957–63, the modern Greek translation of 1984–7, the Romanian version of 1946–91, the French (complete versions, 1979–91, reprinted in 1995, though an earlier Petite philocalie of 1953), the English (complete 1979–2023, though earlier selections from Theophan’s Russian, 1951–4), and the Italian of 1982–7. The Romanian version differs perhaps most radically from the 1782 Philokalia in that it includes many ‘Philokalic’ works not found in the Nikodemos and Makarios ‘original’: the correspondence of the Fathers of the Gaza desert, Barsanouphios and John, as well as Dorotheos of Gaza, The Ladder of Divine Ascent by John of Sinai, Isaac the Syrian and many works of Romanian hesychasm – Vasile of Poiana Mărului, George of Cernica and others. The text of 1782 was not regarded as sacrosanct: modern critical editions are often substituted for the 1782 texts, a process that began with the second Greek edition of 1893, which added ‘missing texts’ to Patriarch Kallistos’s Fourteen Chapters on Prayer and included further texts by Kallistos Angelikoudis (in the 1782 volume called Tilikoudis, and probably identical with Kallistos Kataphygiotis).

This Penguin Philokalia is by design no more than a selection, intended to introduce the ‘Philokalic literature’ to the reader. The selection has been made on grounds of interest, but to reduce the work to a single volume it was necessary to omit many texts that might be regarded as ‘secondary’, notably the whole work compiled by Peter of Damascus, and the ‘madeup’ centuries attributed to Maximos the Confessor, added to the two authentic Centuries on Theology and the Divine Economy to form a series of seven Centuries. Centuries 3–7 are mostly drawn from Maximos’s Questions to Thalassios,

the Confessor’s major work of Scriptural exegesis, more illuminating for how monks of later generations tempered the complexity of Maximos’s thought. The enormous, and enormously valuable, Exact Method and Rule of the Xanthopouloi, Kallistos and Ignatios, has, with regret, been omitted, as have the Three Centuries on Knowledge of Nikitas Stithatos, as we were concerned to include not extracts, but whole treatises, and the addition of these, admittedly fascinating and important treatises, would, in our view, have unbalanced the selection.

We have, however, in contrast to the ‘complete text’ of the Philokalia published by Faber & Faber (all five volumes of which have now, after a long delay, been published), included a translation of the preface, written for the 1782 volume by, presumably, St Nikodemos. For this preface is important for understanding the intentions of the original editors. On the one hand, Nikodemos makes much of the rediscovery of longforgotten and disregarded monastic texts to be found in the Philokalia :

Because of their great antiquity and their scarcity – not to mention the fact that they have never yet been printed – they have all but vanished. And even if some few have somehow survived, they are moth-eaten and in a state of decay, and remembered about as well as if they had never existed.

And his lament continues:

For behold, writings never ever published in earlier times! Behold, works which lay about in corners and holes and darkness, unknown and moth-eaten, and here and there cast aside and in a state of decay! Behold, texts conducive to purification of the heart, watchfulness of the intellect, and the dwelling in us of grace; and in addition scientifically guiding us to deification!

Nikodemos is certainly exaggerating. The earlier work in restoring authentic monastic texts associated with the circles of Vasile of Poiana Mărului and Paisy Velichkovsky makes it clear that Nikodemos was entering into an attempt to recover texts about

the core of the monastic, indeed, of the Christian life, already well advanced. Nevertheless, on the other hand, his sense of the need to restore the spiritual kernel of monasticism is certainly heartfelt: speaking of the neglect of the heart of monastic prayer, Nikodemos laments that ‘There is a real danger that such efficient and exceedingly sweet practice may, in the end, fail utterly, that grace itself be darkened and quenched in this world, and with it our union with God and divinization shattered.’

It is deification, divinization, becoming God, that Nikodemos sets at the heart of the Christian, the monastic, life. His preface begins with an address to God that recalls the opening of Dionysios the Areopagite’s Mystical Theology :

God, the blessed Nature, the perfection beyond perfection, Principle beyond the good and the beautiful that fashions everything good and beautiful – from eternity he determined, in accordance with his divine plan, to deify humankind.

Deification is the work of God; it is beyond human achievement:

ultimately to bear fruit and become through grace children of God [John 1:12] and to be deified, having attained to perfect manhood, unto the measure of the fullness of the stature of Christ [Eph. 4:13]. For this was, as in summary, the whole end and goal of the economy of the Word concerning us.

An unfailing way of laying hold on what the Incarnate Word has secured for us is to be found in the Jesus Prayer:

to pray without ceasing [1 Thess. 5:17] to our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God – not simply, I say, in our mind or only with our lips, for verbal prayer is obvious to all those who choose to worship God, and easy for the one who tries it.

And it is this that Nikodemos brings out by his careful choice of words. Alongside speaking in terms of theosis, a process of assimilation to God, he speaks of theourgesai, related to the word theourgia, which for Dionysios, Nikodemos’s source here,

means God’s work or activity, his working within us – primarily through the sacraments of the Church.

The Philokalia can, in short, be regarded as an epitome of theology, understood less as a learned discipline, and more as drawing out the entailments of the practice of prayer, leading to union with God.

Andrew Louth

Preface to the Translation

The principles of this, like those of any modern translation really, are a balance of fidelity to the original (Greek) and readability in English. We have differed from previous translators in precisely how we achieve those ends, though we have aimed at as strict a fidelity as modern English allows. The Philokalia presents several unique challenges in this balancing act, which require some explanation.

1. Technical terminology. Technical terminology presents two challenges. First, philosophical and theological Greek is replete with terms like nous, dianoia, ennoia, logismos, all of which refer to rational mental faculties, processes and products. In some instances these can be synonymous, in others they can be fitted to subtle distinctions, and some of them are particularly prone to negative moral connotations. For example, ennoia is a thought or concept, and so is logismos, but in some cases logismos means one’s rational capacity generally, and often it means a sinful or impassioned train of thought. It is difficult to tease out these distinctions without resorting to pleonastic constructions and cumbersome notes. We have aimed at consistency, which, in context, will hopefully give readers a sense of the connotative difference a given author is aiming for in a given moment.

Then there are load-bearing philosophical categories passed down from Plato and Aristotle all the way to Nikodemos, like dunamis and energeia, or nous and hêgemonikon. These carry rich intellectual histories and yet are the common stock of educated Greek-speakers. Words like nous and energeia are badly

served by exoticisms like ‘noetic’ and ‘energy’, which have been popular with previous translators. I confess, ‘energy’ has always made me think of batteries and aerobics rather than ‘that activity which is possible and appropriate to an entity by virtue of its nature and constitution’. However, this latter phrase, while more accurate, is a little unwieldy, and so we have simply translated energeia as ‘activity’. In this regard, we have generally opted for commonplace English terms, in keeping with current conventions in translations of wider Greek literature. We have let context determine connotation, as it usually does, and have avoided terms that suggest authors in the Philokalia were running a trade in exotic words. They were not. They were using the language available to them, which gradually came to be shaded with theological meanings thanks to the efforts of authors contained in this very collection. Thus, Gregory Palamas uses words and phrases learned from Gregory of Sinai, and both were deeply influenced by Maximos and Diadochos, among others. Maximos and Diadochos read deeply in Evagrios, and all of them in Aristotle and the Neoplatonic traditions. If you read Aristotle in English, you’ll see energeia rendered as ‘activity’, and the same should be true for Gregory Palamas, as he deploys this age-old category to distinguish the experience of divine light in prayer from an impossible cognition of God’s infinite and unknowable ‘essence’ (ousia ).

And then there is logos. How do you solve a problem like logos ? We have sometimes included it in brackets where we felt the wordplay demanded clarification. As, for example, when Gregory of Sinai uses logos to mean Word of God, teaching, account, spoken word and discursive reason, all in the same paragraph. A further, perhaps even more pressing, example is the frequent use of the noun gnosis, and its adjective, gnostikos, the latter translated ‘gnostic’. In English, ‘gnostic’ and related words have acquired an esoteric ambiance, and in scholarship on the early Christian centuries tend to be narrowed down to refer to second-century dualistic ‘gnosticism’, the archetypal heresy for those, like Irenaeus, later regarded as champions of Orthodoxy. However, in Byzantine ascetic literature, of which the Philokalia is a prime

example, ‘gnostic’ is a common term for one who has begun to experience knowledge (gnosis) of God and union with Him, and it should perhaps be reclaimed for this purpose. For interested readers, we have included a short glossary at the back of some of the more commonly used technical terms.

2. Language conventions and authorial style. Over the millennium of culture from which Philokalic texts were culled, changes in language, developments in technical terminology, not to mention a wide variety of individual styles, were all inevitable. Indeed, by Nikodemos’s day ‘Classical’ Greek had long given way to modern forms far closer to what is spoken today than what Plato wrote. Generally, Philokalic authors wrote in something like ‘Classical’ Greek, although the complete collection contains a few demotic texts and versions from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. More generally, our authors are writing in genres like the ‘gnomic century’ that encourage elliptic, not to say cryptic, aphorisms marked by terseness and allusion. In those cases, we have tried to clarify the sense without adding too much to the text. Thus, we have frequently reinserted the noun where Elias Ekdikos or Gregory of Sinai has only a definite article. We have not aimed for uniformity among the pieces translated here, and readers will readily discover that some authors, like Diadochos, are dense but beautiful writers, while others, like Maximos, are simply dense. By and large, we have happily sacrificed Greek syntax on the altar of readability. In some cases, this has meant splitting up sentences into two or more. In Maximos’s case, it has meant splitting sentences into two or more paragraphs and, in one case, pages. We hope, however, that such choices help clarify the meaning for readers without sacrificing the flow of argument.

3. Gender. Greek defaults to a masculine pronoun and so the implied reader or ‘someone’ of so many illustrations and exhortations is coded masculine. Moreover, almost all of our writers originally wrote for all-male communities, whether in monasteries or elite settings. However, we have taken seriously Symeon of Thessaloniki’s reminder that the Jesus Prayer is for everyone, and Nikodemos’s claim that the Philokalia is likewise for all. In the interest of inclusivity, we have used a mix,

then, of masculine, feminine and the increasingly common singular ‘they’, and likewise used ‘humankind’ or ‘human’, rather than ‘mankind’, for the Greek anthrôpos. In some cases, where it is clear that a male or female individual is implied (as in Gregory Palamas’s To Xenia ), we have retained exclusively masculine or feminine pronouns as seemed appropriate.

It is, of course, impossible to translate any part of the Philokalia into English without paying tribute to the monumental translation undertaken by Gerald Palmer, Philip Sherrard and Metropolitan Kallistos Ware over several decades, and only recently and posthumously completed. This present volume is, to repeat, a fresh translation of selected treatises from the Philokalia, fulfilling a rather different purpose from that full translation of the Philokalia by offering an introduction and overview, a sampler platter representative of the banquet that awaits with further reading. The Philokalia abounds in biblical quotations, allusions and citations. We have translated these as they appear in our authors, which is usually (but not always) the same text as underlies English Bibles. However, all quotations from the Old Testament are from the Septuagint version (abbreviated herein as LXX , but only noted to alert the reader to significant differences), which differs in several ways from the Hebrew text as it is translated in modern Bibles. There are three to be aware of:

1. The numbering of the Psalms and, in some cases, their verses is different. Because the Psalms are quoted more than any other biblical book in the Philokalia, it is worth keeping in mind that the numbering differs somewhat from the Hebrew text translated in most modern Bibles. For most psalms, the Septuagint number is one less than the Hebrew. However, what follows is a complete table of correspondences:

113 114–15

114 116:1–9

115 116:10–16

116–45 117–46

146 147:1–11

147 147:12–20

148–50 148–50

151

2. Content, especially in poetic texts like Isaiah or Job, is frequently obscure and not always traceable to the Hebrew. However, Christian writers frequently make much of semantic nuances in the Septuagint text, so it is essential to preserve what might otherwise be thought of as mistranslation.

3. The Septuagint contains a number of books not included in the Protestant canon of Scripture, though these are found in Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Bibles. Several such texts – referred to frequently as ‘apocrypha’ or ‘deuterocanonical’ books – are very important to our writers, such as the Wisdom of Jesus Ben Sirach (sometimes called Ecclesiasticus, cited throughout as ‘Sirach’). Some books of the Septuagint Old Testament bear a different name from those given in the Hebrew Bible. So the books of Samuel and Kings are grouped together as four books of Kingdoms (1 and 2 Samuel – 1 and 2 Kingdoms (Kgds); 1 and 2 Kings – 3 and 4 Kgds). 1 and 2 chronicles are called 1 and 2 Paralipomena (meaning supplements, as they supplement, rather than continue, 1–4 Kgds).

Outside Scripture, our authors regularly quote or allude to nonbiblical texts, both Christian and, more infrequently, Greek philosophical ones. While all translations of these are our own, we have noted them in the endnotes and, where possible, directed readers to accessible English translations. Where English translations do not exist, we have referred instead to available editions.

Liturgical Hours and Offices

Over the millennium of Christian history behind the Philokalic texts, Christian rites and rituals (liturgies) developed and regularized around set patterns of daily, weekly and yearly cycles. Our authors do not discuss these very often. Rather, they presume the rhythms of prayer, hymns and sacraments as the warp and woof of Christian life. All services include prayers, psalms and hymns. Psalms are sung in every service, in groups that, over the course of a week, comprise the entire Psalter. At the same time, some services always include certain psalms. Thus, Psalm 50 (‘Have mercy on me, O God . . .’) is sung at almost every service, while Orthros (or, Matins, ‘morning prayer’) begins with the ‘Six Psalms’: 3, 37, 62, 87, 102 and 142, and Hesperinos (or, Vespers, ‘evening prayer’) with Ps. 103.

Byzantine services are also peppered with other hymns, concerning the life of Christ, his Passion and Resurrection, the Cross, Mary, and the saints being commemorated that day. These are determined by the hour of the day, the day of the week, the day of the year, the festal seasons and so on. The day itself was divided not by clocks but by sunrise and sunset. The time of daylight was divided into twelve parts, called hours; and the time of darkness likewise. Liturgical offices came to be celebrated, especially in monasteries, at the first, third, sixth and ninth hours. The offices associated with these hours are relatively short, though the first was preceded by Orthros, and the ninth followed by Vespers, sung at sunset. Compline was sung after sunset. One thing to keep in mind is that these hours necessarily vary over the course of the year, and our authors sometimes account for seasonal differences in daytime and night-time.

The Eucharist came to be celebrated daily in monasteries, but more ancient practice had it only once or twice per week, on Saturday and Sunday, as part of a service known generally as the divine Liturgy, though sometimes just called the Synaxis. Each day of the week would eventually have its particular commemoration – angels, apostles and so on – in addition to the saint of the calendar day, and whatever fast or feast was being observed. Since Easter (in Greek, Pascha ) was, and is, reckoned according to a lunar calendar, the fast of Great Lent and feast of Pascha to Pentecost fall at different times in the spring. Depending on their era, Philokalic authors may presume either pattern or name, but in every era their lives were defined by interlocking rhythms of day and night, week and calendar, season and feast.

SELECTIONS FROM THE PHILOKALIA OF THE HOLY ASCETIC FATHERS

St Nikodemos of Athos, Introduction to This Book

ST NIKODEMOS OF ATHOS, ‘THE HAGIORITE’ (1749– 1809)

In his Prologue to the Philokalia, Nikodemos sets out both the purpose and scope of the anthology, and its genesis. Of this latter, the account he gives, of neglected manuscripts unknown and unread, is a stock device among premodern historians. It seems clear from comparison with other ascetic miscellanies copied between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, that the range of authors and works gathered in the Philokalia is rooted in Athonite reading and scribal practices going back centuries. Nikodemos, though, is not satisfied with exposing these texts to a wider monastic audience. Rather, he sees in them a way of prayer incumbent on all Christians, ever since Paul admonished the Thessalonians to ‘pray without ceasing’. Moreover, Nikodemos takes seriously the claims among authors that the ‘Jesus Prayer’ and its repetition, the cultivation of interior prayer, is the means of salvation and even deification. He presents the Philokalia as a practical manual, a source of inspiration, a guide and ever-present voice of conscience for readers who take its words seriously.

Sources

Text: PHILOKALIA (1782): 1–8; Philokalia (1893/1982): vol. 1, 19–24

For Nikodemos’s biography, please refer to our Introduction.

Introduction to This Book

God, the blessed Nature, the perfection beyond perfection, Principle beyond the good and the beautiful that fashions everything good and beautiful – from eternity he determined, in accordance with his divine plan, to deify humankind. Having pre-eminently set himself this goal from the beginning, at the time when it pleased him to do so, he created humankind. Taking the body from matter, he placed in it a soul from himself, which he established as a sort of world in miniature, though great in the multitude and pre-eminence of its faculties. This creature he made overseer of sensible Creation and initiate of the intelligible according to Gregory who is great in theology.1 And what else is man than God’s true portrait and image made by Himself, filled with every gift of grace? So then, having established the law of his command for man as a sort of trial of his liberty, God knew that he had to leave the rest to man. For, as Ben Sirach says, God left man to his own devices [Sirach 15:14], to choose to do whatever he was resolved on, with the prize that, if he kept the command he had received, he would obtain the genuine grace of deification, becoming God and blazing with the most pure light forever. But in fact – oh the wicked knavery of envy! – the original author of evil did not allow all this to happen. Rather, he conceived envy against both the Creator and his creation, as Holy Maximos says: envy of the Creator, lest the active power of the all-hymned Goodness that divinely works in humanity be manifest; envy of creation, lest it be revealed a partaker of such supernatural glory as deified.2 Cunningly did the deceiver outwit wretched man, and, indeed, he convinced them with plausible-sounding

arguments to transgress the God-given command. Having drawn man away from divine glory – alas! – the usurper fancied himself some kind of Olympian, because he had been able to thwart the fulfilment of God’s pre-eternal plan.

Since according to the divine oracles, God’s plan for the deification of human nature endures forever, and the thoughts of his heart to generation and generation [Ps. 32:10], the principles of providence and judgement, which alike drive towards this goal, operate unalterably both in this present age and in the age to come – according to the explanation of the Holy Maximos.3 So in these last days [Heb. 1:2], because of his tender mercy [Luke 1:78], the supremely divine Word of the Father was pleased to topple the plans of the rulers of darkness, to accomplish and bring into action what he established as his ancient and true plan. Therefore, by the good pleasure of the Father and the cooperation of the Holy Spirit the Word became incarnate and took to himself our whole nature and deified it. First, he gave us his salvific and deifying commands and the perfect grace of the All-Holy Spirit through Baptism – as though he were sowing divine seed in our hearts. Then he gave to us, according to the divine Evangelist, authority – provided we live according to his life-giving commands, maturing in the Spirit and through their operation preserve unquenched the grace in us – ultimately to bear fruit and become through grace children of God [John 1:12] and to be deified, having attained to perfect manhood, unto the measure of the fullness of the stature of Christ [Eph. 4:13]. For this was, as in summary, the whole end and goal of the economy of the Word concerning us.

But, alas! It is good to weep bitterly at this point, to quote the divine Chrysostom.4 For we were enjoying such grace and made worthy of such nobility, that our soul shone more than the Sun, by the Spirit in Baptism. Since as children we received such a most godlike radiance, we have been blinded to this by ignorance, but mostly by the darkness of worries about this life, and have buried grace under the passions so deeply that we are in real danger of quenching the Spirit of God within us. We are in danger even of suffering nearly the same things as those who replied to Paul saying, But we have not heard whether

there is a Holy Spirit [Acts 19:2]. We are risking even reverting back to where we were in the beginning when, according to the Prophet, grace did not rule us. Alas, our infirmity! That wickedness and our unnecessary attachment to sensible things should destroy us! And this is indeed a marvel, that even if we should sometimes hear that grace is actively working in others, we become envious and slander them – and do not even believe that grace is active in the present age! What, then? The Holy Spirit instructs our divinely wise Fathers and, through their unbroken watchfulness, their constant attentiveness and guarding of the intellect, reveals to them the way to find grace anew, a way truly marvellous and absolutely scientific. This way is: to pray without ceasing [1 Thess. 5:17] to our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God – not simply, I say, in our mind or only with our lips, for verbal prayer is obvious to all those who choose to worship God, and easy for the one who tries it. Rather, having our whole mind turned towards the inner man [2 Cor. 4:16] – which is also a marvel! – inwardly and in the very depths of our heart to call upon the all-holy Name of the Lord and seek out his mercy, paying attention only to the simple words of the prayer, admitting nothing else from within or without, so as to guard our mind wholly from anything of form and colour.

The means of this practice and, if I may put it thus, its matter I have from our Lord’s own teaching, when he said, The kingdom of God is within you [Luke 17:21]. And then, Hypocrite! First cleanse the inside of the cup and dish and then their outside will be clean [Matt. 23:26]. These statements are understood not as pertaining to matters of the sensory world, but to our inner man. And from the Apostle Paul writing to the Ephesians, we have this: For this reason I bend my knees to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, that he may give it to you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner man, so that Christ will dwell in your hearts through the Spirit [Eph. 3:14–17]. What could be clearer than this witness? And elsewhere he writes, Praising and singing psalms to the Lord in our heart [Eph. 5:19]. Do you hear? In our heart, he says! Moreover, Peter, the leader of the apostles, further confirms

this, saying, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts [2 Pet. 1:19]. The Holy Spirit teaches in these and how many myriad other pages in the New Testament that this practice is necessary for everyone practising piety, as can be seen by those who inquire carefully in these places. Alongside the more accessible practice of the commandments and the rest of the moral virtues, this practice, since it is both spiritual and scientific, utterly consumes the passions through the fervency which emerges in the heart from the invocation of the all-holy Name, and through the spiritual activity appropriate to that fervency. For our God is fire and a fire which consumes wickedness [Heb. 12:29]. As our intellect and heart are purified gradually, they come to be united one with another, and then the salvific commands are accomplished more easily. Thereafter the fruits of the Spirit make their appearance in the soul and the whole heap of good things sprouts up. Finally, to keep things brief, we will be able to return more swiftly to the perfect grace of the Spirit which was given to us in Baptism, which, though it is in us, has been buried under the passions like a spark in soot. Kindling this spark to flame we will see far and wide: we will be intelligibly enlightened, then perfected and, in due order, deified.

Most of the Fathers mention this activity here and there in their writings, crafting their argument for those who understand. Some of them, perhaps envisaging our generation’s ignorance and carelessness regarding this salvific practice, and having expressed its practical manner in detail through certain physical methods, did not shrink from handing this down to us their children as a kind of family inheritance. These men also extolled this practice under many names and addressed it as the principle of every other God-loving activity, the heaping-up of good things, the purest token of repentance, and the intellective act which leads to true contemplation. Extolling and addressing it thus, they exhorted everyone to this profitable activity.

But now I must mourn, and grief cuts short my account! For I speak of all the books which philosophize about such purifying, illuminating and perfecting activity (to speak like the Areopagite) – and not only these but others as well – as many as

are popularly called ‘Watchful’, because they expound in detail attentiveness and watchfulness. All of these alike are the necessary means and tools for attaining the same purpose, having the one goal of achieving divinization in humankind. Because of their great antiquity and their scarcity – not to mention the fact that they have never yet been printed – they have all but vanished. And even if some few have somehow survived, they are moth-eaten and in a state of decay, and remembered about as well as if they had never existed. I will add that most of our monks are disposed to be careless, and troubled about many things [Luke 10:41] – that is, bodily matters and the practice of virtues, or, to speak more accurately, only the tools of virtue, in which they spend their whole life. But as to the one thing – clearly, guarding the intellect and pure prayer – I do not understand how they stupidly neglect it. There is a real danger that such efficient and exceedingly sweet practice may, in the end, fail utterly, that grace itself be darkened and quenched in this world, and with it our union with God and divinization be shattered.

This very thing – our divinization – was, as has been said, planned from the beginning and, according to his good pleasure, the will of God [Eph. 1:4]. For this, indeed, as for a goal most suited to his purpose, we have been both brought into being and, through the economy of his Word concerning us, are being brought to well-being and eternal well-being and, to be blunt, all that has been accomplished in a manner befitting God in both the old and the new dispensations.

Once many even of those who were in the world – Kings themselves, and those who lived in palaces and exerted themselves in myriad thoughts and cares of this life – all had one and the same work: praying unceasingly in their heart. We find them often in our histories. But now, from carelessness and ignorance, not only among those in the world but even among monks and those who live as solitaries in stillness, this work is extremely rare and – what a tremendous loss! – hard to find. Deprived of what is needed, though they struggle each according to his own ability, and endure labours for the sake of virtue, none actually reaps any fruit. For, without unceasing

mindfulness of the Lord, which gives rise to purity, free from every evil, in the heart as well as in the intellect, it is impossible to bear fruit: Without me, it says, you can do nothing. And again, Who abides in me bears much fruit [John 15:5].

Right now, I can see no other reason why those eminent in holiness (both while living and after death) have been so forsaken, and so those being saved are so few [Luke 13:23] in our present time, than this, that clearly we have abandoned the work that leads to deification. And, someone says, apart from the deification of the intellect, it is not possible for the human to be sanctified or saved – which, even but to hear is exceedingly horrible, for being saved and being deified are the same thing according to the revelation of those wise in God. But the decisive issue is that we are robbed of the books which would guide us to our salvation and deification. Without these, it is absolutely impossible to attain our goal.

Behold, the ever noble and good Lord John Mavrogordatos, a true lover of Christ! One second to none, even among those of the highest rank, in the principles of liberality, of love for the poor and the stranger, and of the whole chorus of virtues. Behold one who ever glows with divinely inspired zeal for public beneficence! This man, yes, this very man, inspired by the grace of Christ who wills all people to be saved [1 Tim. 2:4] and deified, transforms my lament into joy as he resolves my perplexity! For having displayed the means of deification to the public with all his soul he works together in his turn in every way – indeed, if I may be so bold, with his hands and feet runs together – with the pre-eternal will of God. What glory! What magnificence! For behold, writings never ever published in earlier times. Behold, works which lay about in corners and holes and darkness, unknown and moth-eaten, and here and there cast aside and in a state of decay. Behold, texts conducive to purification of the heart, watchfulness of the intellect, and the dwelling in us of grace; and in addition scientifically guiding us to deification. Gathering these into a single whole without caring a whit about cost, he hands them over now to the glorious, shining light of the printed word. (For it was necessary, it was indeed necessary, that things which speak

in detail about divine illumination be deemed worthy of the light of printing!) And through this he frees the erudite from the labours of transcription while rousing the neophyte to the desire of its acquisition, and, I think, to putting this learning into practice.

So, dearest reader, you have without further labour easily procured this spiritual book, thanks to John, a man best in every way: a book which is a treasury of watchfulness, a guardhouse for the intellect, a mystical schoolhouse of intellectual prayer; a book which is an excellent outline of the practical life, an unerring guide in contemplation, the Paradise of the Fathers, a golden chain of virtues; a book which is intimate converse with Jesus, the sounding trumpet of grace, and – to speak briefly – the very tool of deification. It is a possession longed for ten thousand times more than any other, for many years pursued and sought after, but not found. For this reason an inescapable debt is imposed upon you, owed according to every principle of justice, that you beseech the Divinity with fervent prayers for your benefactor and his fellow-workers, that they may attain to the same measure of deification and that, since they have laboured on this, they may be the first to enjoy its fruits.

But at this point someone might perhaps find fault with what we have said, saying that it is not lawful to publish some of the things in this book and thus bring them to the ears of the public, because of their strangeness. They might add that a certain danger accompanies these things. We will briefly lodge our counter-objections. First of all, beloved companion, we did not come to such an undertaking contenting ourselves with our own thoughts; rather, we followed exemplars. First, we see in the sacred Scriptures that it is commanded to absolutely all the faithful without distinction to pray without ceasing [1 Thess. 5:17], and always to have the Lord before our eyes. And, according to Basil the Great, it is impious to say that something hinders the precepts of the Spirit or that they are impossible to follow.5 Moreover, we see the same also in the written tradition of the Fathers. For Gregory the Theologian commands absolutely all the laity under him to be mindful of God rather

than even to breathe.6 The divine Chrysostom dedicates three whole sermons to unceasing and intellectual prayer, and in ten thousand places in the rest of his works, he exhorts everyone to pray always. And that marvellous man, Gregory of Sinai, travelled through various cities teaching precisely this salvific practice. But even God himself, having by a miracle sent an angel from above, set his seal on such truth when he silenced the monk who spoke against it, as is seen in the end of this book! And what else should I say? Where those who are in the world, even living in palaces, have such meditation as their unbroken work (as we have said), they confirm our account by their actions, and are themselves sufficient to silence any critics. If some went astray after a little while, why is that so strange? In most cases, according to Gregory of Sinai, they have suffered their fall out of self-conceit. But I consider the cause of this wandering to be especially and properly this: that they do not carefully submit to the teaching of the Fathers concerning this activity. It is nothing against the activity itself. Stop that nonsense! For the activity is holy and we pray to be delivered from all error through it. And though unceasing prayer is a command according to the law of God, guiding us to life – in some, says Paul, it is found to be unto death [Rom. 7:10]. But this has not happened because of the command. How could it, when the command is holy, just, and true ? [Rom. 7:12]. Rather, it is because of the depravity of those sold under sin [Rom. 7:14]. Why, then, because of this? Must we condemn the divine command because of the sin of some? Must we set at naught such salvific activity because of the apostasy of some? In no way! We should do neither the one nor the other. Rather, having confidence in the one who said, I am the way and the truth [John 14:6], we must undertake the work with all humility and a sorrowful disposition. For, according to the teaching of the Fathers, even if every wicked phalanx of demons should attack him, they will not be able to come near one who has been delivered from self-conceit and the desire to please people. Since these matters stand thus, and on all sides Scripture proposes always and in every way blameless perfection (of which some passages have been quoted), it would be most opportune,

finally, to take in our hands that invitation to the banquet of Wisdom, and with a sublime proclamation to call all to the spiritual feast of this book. All of you – you are no despisers of the divine banquet, nor ones to offer excuses about fields and oxen and wives, like those in the Gospel [Luke 14:18–20] – all of you, then, come, come! Eat the gnostic bread of wisdom found in this book, and drink the wine which gladdens the heart [Ps. 103:15] intelligibly, abandoning everything, both sensible and intelligible, for the sake of ecstatic deification, and be drunk with a drunkenness truly sober! Come all, as many as are partakers of an orthodox calling, both laypeople and monks together, who have endeavoured to find the Kingdom of God that is within you [Luke 17:21], and the treasure hidden in the field of your heart [Matt. 13:44], which is our sweet Jesus Christ, so that with your intellect freed from the captivity and whirlwind of things below, and your heart purified from all passions, through the unceasing, fearsome invocation of our Lord Jesus Christ, with the cooperation of the other virtues which are taught in this book, you may be united to yourselves, and through yourselves to God. So did our Lord beseech his Father that they may be one, as we are one [John 17:11]. Finally, having been united to God and wholly transformed by the inspiration and ecstasy of divine eros, may you be most richly deified, in your intellectual sense and unwavering assurance, and return at last to God’s first purpose, glorifying Father, Son and Holy Spirit, the one, most thearchic Godhead, to whom is due all glory, honour and worship to the ages of ages. Amen.

Evagrios Pontikos, One Hundred and Fifty-Three Chapters on Prayer

EVAGRIOS PONTIKOS ( c . 345– 99)

Evagrios hailed from Pontos, on the south coast of the Black Sea, in what is now Turkey. He was ordained a reader by St Basil of Caesarea (‘the Great’, 330–79) in 371 and a decade later went to Constantinople with St Gregory Nazianzen, whom he impressed with his learning and theological acumen, and whom Evagrios would call ‘our wise teacher’. After an unhappy love affair, he fled Constantinople for Jerusalem and the monastic community led by a noblewoman named Melania, who eventually persuaded him to seek Egypt. Evagrios settled in Nitria, and spent the rest of his life there. He was already a renowned and controversial figure when he died in 399. In the sixth century, he would be implicated in attacks on the legacy of Origen of Alexandria and decried as a heretic. Many of his works survive only in Syriac, while others, like On Prayer, passed under the name of Neilos. So it is found in the 1782 edition of the Philokalia. Under this guise Evagrios’s works influenced traditions of prayer in Byzantine and Eastern Christianity, as the inclusion of On Prayer in the Philokalia demonstrates.

Evagrios was a prolific and profound writer, who leveraged philosophical concepts and ideas onto an educational programme for Christian ascetics. In this programme, the monk engages first in unlearning old affective and cognitive habits and developing new ones defined by tranquillity, humility and love (the life of ‘practical’ or ‘active’ virtue). They can turn then to contemplation, first of the created world, and then of

its creator (the ‘contemplative’ life). Prayer runs as a golden thread through these stages of life, though its content and practice develop with the Christian, from supplication to conversation with God. This text, On Prayer, was intended for Christians in the final stages of development, and presumes a life of careful discipline within the rhythms of monastic life. In it Evagrios describes the conditions and experience of ‘pure prayer’ as a way of communion between the intellect and the infinite God, unmediated by any imagined form or idea that would place limitations on the Deity.

Sources

Text: Paul Géhin (ed.), Évagre le Pontique: Chapitres sur la prière, Sources Chrétiennes 589 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 2017): 208–368

Alternative text: PHILOKALIA (1782):155–65; Philokalia (1893/1982): vol. 1, 176–89

One Hundred and Fifty-Three Chapters on Prayer

Prologue to the One Hundred and Fifty-Three Chapters on Prayer

You always refresh me when I burn with the fire of unclean passions, by the touch of your pious words, having imitated our great guide and teacher, Makarios.1 You have soothed my intellect, which flounders in the most shameful things. And no wonder! The speckled sheep have ever been your lot, as they were for the blessed Jacob [Gen. 30:42]. Like him, too, you served well for the sake of Rachel and, having received Lea [Gen. 29:25], you still seek the woman you desired, since for her too you have completed your seven years’ labour. But I would not deny that, having laboured the whole night, I have caught nothing. Nevertheless, having let down my net at your command, I have caught a multitude of fish. While I do not consider them very large, there are altogether one hundred and fifty-three [John 21:11]. Having sent these in a basket of love, through an equal number of short chapters, I have fulfilled the requisition.

I marvel at you and I greatly envy your desire for the excellent prospect of chapters on prayer. For you do not simply want such as are handy and which exist merely in ink on the page, but, rather, inscribed in your intellect, through love and absence of malice. But since All things are twofold, one opposite the other, according to the wise Jesus [ben Sirach] [Sirach 42:24], receive the spirit along with the letter. You know that understanding [nous ] always precedes the letter – for where there is no understanding, there is certainly no letter! And

so, therefore, the way of prayer is also twofold. The first is practical, the second theoretical. So too about the number of chapters: its quantity is a handy mnemonic aid; its quality is significant.

Having divided our discourse on prayer into one hundred and fifty-three parts, we have sent you an evangelical wage, that you may find delight in the symbolic number, with regard to its triangular2 and hexagonal forms.3 The former reveals a pious knowledge of the Trinity; the second, a pattern of this world. But, in addition, the number one hundred is itself a square number. And fifty-three is both triangular and spherical: you get it by adding twenty-eight to twenty-five, and while twenty-eight is triangular, twenty-five is spherical, since five times five is twenty-five.4 Then, you have the square form:5 for not only do you have the tetrad of the virtues, but also the wise knowledge of the present age – as with the number twentyfive, on account of the recurrent nature of time. For week moves into week and month into month, and time revolves from year to year and moment to moment, as we behold in the motion of sun and moon, spring and summer, and the seasons. But the triangular form could signify to you the knowledge of the Holy Trinity. Otherwise, preserving through multitude the number one hundred and fifty-three, which is triangular, consider it as practical, natural and theological knowledge; or, perhaps, as faith, hope and love [1 Cor. 13:13]; or even gold, silver and precious stones [1 Cor. 3:12]. There you have the number.

But do not mock the humility of these short chapters, since you have known how to be filled and how to go hungry [Phil. 4:12], especially since you remember that the widow’s two mites were not rejected, but received more than the wealth of many others [Mark 12:42]. So then, having known how to guard the fruit of goodwill and love with your neighbouring brothers, pray for one who is unwell that he may become healthy, and, having taken up his pallet, he may walk by the grace of Christ [John 5:8]. Amen.

On Prayer: One Hundred and Fifty-Three Chapters

1. Should someone wish to prepare fragrant incense, he will mix in equal measure translucent frankincense, cassia bark, onyx and oil of myrrh, as it prescribes in the Law [Exod. 30:34–7]. These four ingredients represent the tetrad of virtues, for if those are mixed in completely full and equal measure, the intellect will not be betrayed.

2. A soul purified through the fullness of the virtues prepares a stable arrangement for the intellect and so makes it receptive to the state that is sought.

3. Prayer is the intellect’s conversation with God. What sort of state must the intellect need such that it can be unstintingly drawn out towards its rightful master and, without need of any mediator, intimately converse with him?

4. If, when he attempted to approach the burning bush on earth, Moses was prevented until he loosed the sandals from his feet [Exod. 3:5], how will you – who wish to see the one beyond all perception and thought, and to be his confidant – how will you not remove from yourself every notion marked by passion?

5. First, pray concerning the acquisition of tears, that through mourning you may be enabled to sooth the savagery that indwells your soul, and, having confessed your transgression to the Lord [Ps. 31.5], you may find forgiveness with him.

6. Make use of tears for the success of every petition. For your master rejoices exceedingly when he receives tear-stained prayers.

7. Even if you pour out whole fountains of tears in your prayers, do not be exalted in yourself, as though you were better than the common crowd. For your prayer received additional aid, that you might be able to confess your sins eagerly, and propitiate your master with tears. So do not turn this defence against passions into a passion itself, lest you anger all the more the one who has given you this grace.

8. Many who weep for sins have forgotten the goal of tears and so they have fallen away in their madness.

9. Stand diligently, pray vigorously, and turn away all preoccupation with present concerns and calculations, for those trouble and confuse you to slacken your vigour.

10. When the demons see you exerting yourself to pray truly, then they will suggest notions of certain seemingly necessary matters. After a little while, they will take from you the memory of those same matters, and they will move your intellect to search for them – so that, when it does not find them, it will be greatly grieved and discouraged. At other times, when you are standing in prayer, they will remind your intellect of things sought after and recalled, so that your intellect will relax into the knowledge of those matters and so utterly lose its fruitful prayer.

11. Strive to make your intellect deaf and dumb during the time of prayer, and you will be able to pray.

12. Whenever temptation or contradiction come upon you or provoke you to be moved, for the sake of revenge on some opponent, to anger or to break into cries with an unseemly voice – remember your prayer and judge in accord with it, and immediately the disorderly movement within you will come to rest

13. Whatever you do to get revenge on a brother who has wronged you will become a stumbling block for you in the time of prayer.

14. Prayer is the flower of meekness and freedom from anger.

15. Prayer is the product of joy and thanksgiving.

16. Prayer is the remedy for sadness and discouragement.

17. Going away, sell your goods and give to the poor [Matt. 19:21] and, having taken up the cross, deny yourself [Matt. 16:24], that you may be able to pray without being distracted.

18. If you wish to pray praiseworthily, deny yourself hour by hour, and even if you suffer numerous terrible things, bear them philosophically for the sake of prayer.

19. You will find at the time of prayer the fruit of whatever difficulty that you endure philosophically.

20. If you desire to pray as you should, do not grieve a single soul – if you do, you will run in vain.

21. Leave your gift, it says, before the altar and, going away, first be reconciled with your brother [Matt. 5:24]. Then, on

return, you will pray without disturbance. For the remembrance of wrongs blinds the soul’s leading faculty in one who prays and darkens his prayers.

22. Those who heap griefs and grudges on themselves and yet imagine they are praying are like people who draw water and pour it into a sieve.6

23. If you are a patient sort of person, you will always pray with joy.

24. When you are praying as you should, matters will occur to you that you imagine justify anger. But there is no such thing as justifiable anger against your neighbour. If you seek, you will find that it is possible to resolve the matter without resorting to anger. Therefore, use every possible means to avoid breaking out in anger.

25. Watch out, lest, imagining that you are healing someone else, you put yourself beyond healing and, in fact, give a fatal blow to your prayer.

26. Be sparing with anger and you will find yourself spared; show yourself prudent and be among those who pray.

27. Armed against anger, you will never give in to desire. For desire gives fuel to anger, and anger troubles the eye of the intellect [Ps. 6:7], ruining the state of prayer.

28. Do not pray in outward forms alone, but, rather, with much fear, turn your intellect to the conscious experience of spiritual prayer.

29. Sometimes when you stand for prayer all at once you pray well. Sometimes, however, after long labour you still do not achieve your goal, so that you will go on seeking and, having received it, you will clutch your success tightly.

30. When an angel stands over you, suddenly all those who would trouble you stand back, and as you pray healthily your intellect will be relaxed. But, when they wage their customary war against you, your intellect fights and is not permitted to relax, for it has already been affected by various passions. Still, if you seek all the more you will find, and to the one who knocks vigorously it will be opened [Matt. 7:8].

31. Do not pray that your wishes be fulfilled, for these do not accord entirely with God’s will. Instead, pray just as you have

been taught, saying, Let your will be done in me [Matt. 6:10]. Petition God thus in every matter, that his will be done. For he desires what is good and beneficial for your soul, but you do not always seek that.

32. Often when I have prayed, I sought that what I thought good would come to pass for me, and I persisted, irrationally trying to constrain God’s will instead of yielding to it so that he might dispense what he knows to be beneficial. When I received exactly what I had asked for, I was then greatly grieved because I had not, instead, asked that his will be done – for the matter did not turn out as I had expected.

33. What is good but God? Let us, therefore, yield everything that concerns us to him, and it will be well with us. For he is entirely good and the giver of good gifts.

34. Do not fall into doubt when God does not immediately grant your request. For he wants to do you far more good if you persist in prayer before him [Acts 1:14]. For what could be nobler than to converse intimately with God and to be drawn into union with him?

35. Prayer without distraction is the supreme intellection of the intellect.

36. Prayer is the ascent of the intellect to God.

37. If you long to pray, renounce everything that you may inherit the whole.

38. Pray first to be purified from passions; secondly to be delivered from ignorance and forgetfulness; and thirdly to be delivered from all temptation and dereliction.

39. In your prayer, seek only righteousness and the kingdom – that is, virtue and knowledge – and all the rest will be added to you [Matt. 6:33].

40. It is right to pray not only for your own purification, but also for the whole human race, that you may imitate the way of the angels.

41. Look and see whether you have truly presented yourself to God in your prayer or are instead overcome by human praise and hastening to chase after it, so that you are using the appearance of prayer as a screen.

42. Whether you pray with your brothers or by yourself, force yourself to pray not by habit but with feeling.

43. Feeling in prayer means meditation with reverence, compunction, and pain in the soul as it confesses its failing with silent groans.

44. If your intellect is still looking around in the time of prayer, it does not yet know that it is a monk praying; rather, it is still a worldling decorating its outer tabernacle [cf. 2 Cor. 5:14].

45. When you pray, guard your memory with all your might, so that, instead of its presenting you with your own concerns, it moves you to attentive knowledge. For the intellect is quite naturally prone to be carried off by the memory at the time of prayer.

46. When you pray, your memory brings you the imaginings of old deeds, or new cares, or the face of someone who has grieved you.

47. The demon begrudges a person who prays and will use every trick to wreck their pursuit. Therefore, he does not cease from rousing the concepts of things through the memory, or from raising up as many passions as he can through the flesh, so that he can impede their excellent course and pilgrimage to God.

48. When that most wicked demon, after many attempts, cannot impede the zealous one’s prayer, he relaxes a little and thereafter revenges himself on the one who prays. For either, having kindled them to anger, he causes the excellent state that was formed in them from their prayer to vanish. Or, having provoked some irrational pleasure, he insults their intellect.

49. When you are praying as you should, watch out for what should not be, and stand boldly, guarding your fruit. For you were given this command right from the beginning: to work and to guard [Gen. 2:15]. So then, when you have worked, do not leave the fruits of your labour unattended, otherwise, for all your praying, you will gain nothing.

50. All war contrived between us and the impure demons is over nothing else than spiritual prayer, for it is exceedingly

hostile and grievous to them, while to us it is salvific and supremely pleasant.

51. What does it mean for the demons to rouse in us gluttony, lust, greed, anger, resentment and the other passions? It is so that the intellect, having been fattened up on these passions, cannot pray as it should. For as the passions of the irrational part of the soul take control, they do not permit the intellect to be moved rationally and to seek after God the Word.

52. We pursue the virtues for the sake of the natural principles [logoi ] of created things, and we pursue those inner principles for the sake of the substantial Word [Logos ] – but this last is accustomed to appear in the state of prayer.

53. The state of prayer is a dispassionate disposition which by a love most supreme finally enables the philosophical, spiritual intellect to attain the intelligible summit.

54. The person who wishes to pray truly must not only rule over anger and desire, but must pass beyond impassioned thought.

55. One who loves God will always converse with him as with a father, provided he turns away from every impassioned thought.

56. One who has already attained dispassion does not thereby pray truly. For it is possible to be among simple thoughts yet distracted by relating them, and so be far off from God.

57. It is not merely when the intellect does not linger among bare thoughts of things that it thereby finds the place of prayer. For it is possible to be in contemplation of things and meditate on their principles [logoi ]; for, even though they are mere words, they are nevertheless contemplations of things, which form and shape the intellect, and so lead it away from God.

58. Even if the intellect surpasses the contemplation of bodily nature, it has not yet seen the perfect place of God. For it is possible to come to the knowledge of intelligible things and still partake in their diversity.

59. If you wish to pray, you need God who gives prayer to the one who prays [1 Kgds 2:9]. Therefore, you must call upon him, saying, Hallowed be your name, that is, your onlybegotten Son; Your kingdom come, that is, your Holy Spirit