SENECA

LETTERS FROM A STOIC

LETTERS FROM A STOIC

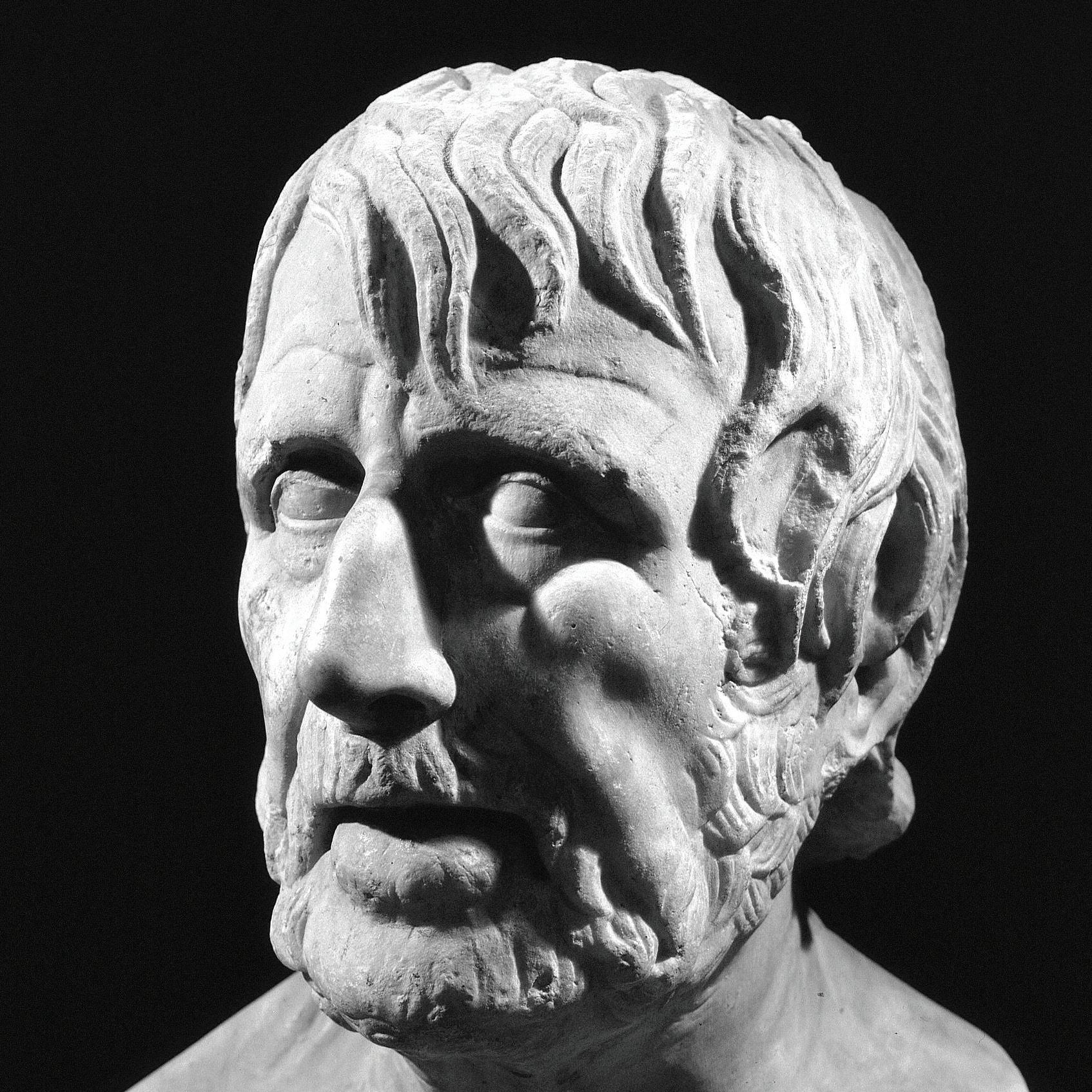

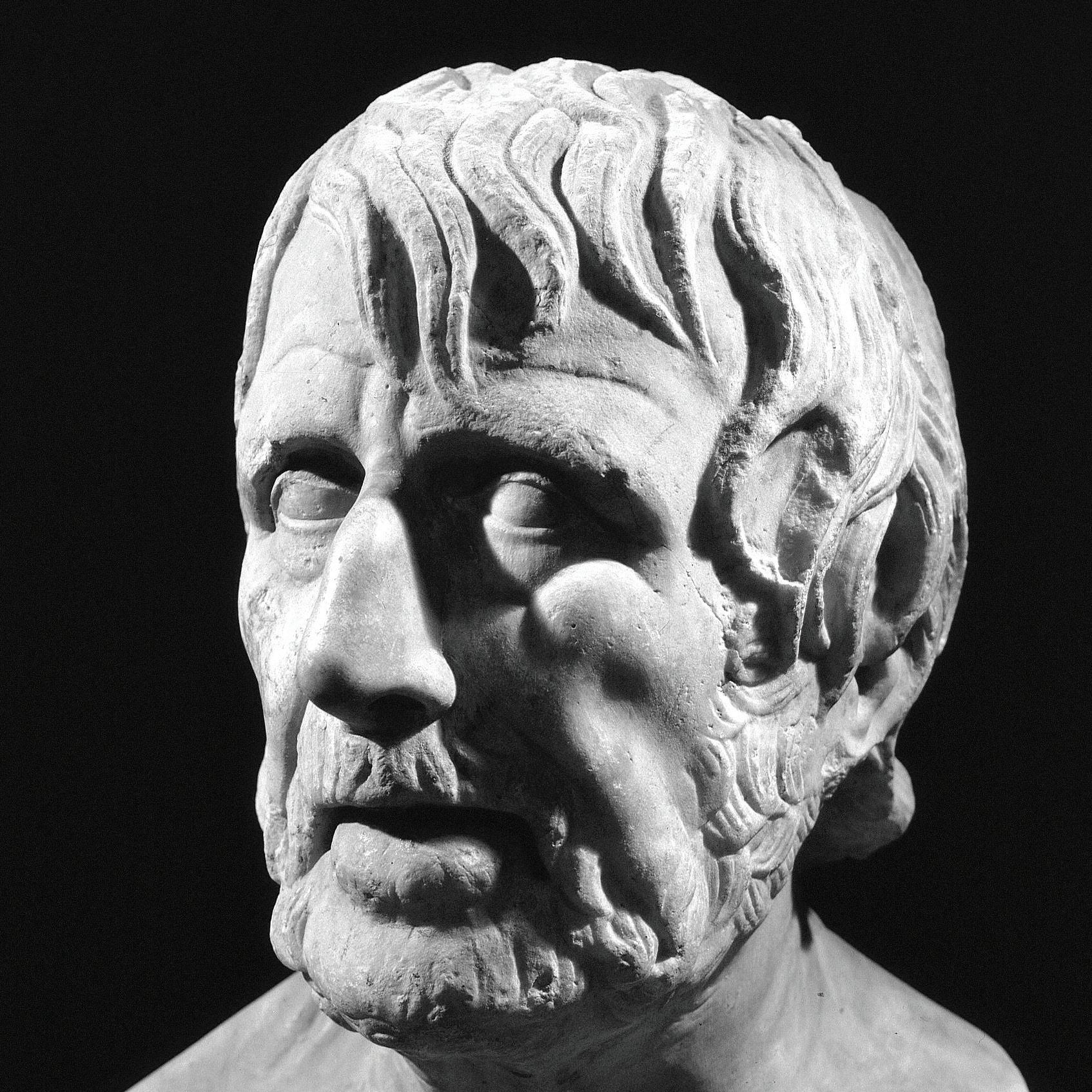

LuCius AnnAeus seneCA (c. 4 BC – AD 65) was born in Cordoba, Spain, into a Roman political family who divided their time between their Spanish estate and the Roman capital. After beginning his political and legal career under the emperor Caligula, he was exiled in AD 41 by the emperor Claudius; he was later recalled in AD 49 to serve as tutor to a young Nero. Following Nero’s accession, he continued to act as his advisor before his retirement. In AD 65, Seneca died by suicide on Nero’s order after he had been implicated in an assassination plot against the emperor. He was a prolific writer who wrote in a wide range of genres, encompassing philosophy, satire and tragic drama, and is one of the most significant figures in the history of Stoicism.

LiZ gLoYn is a Reader in Latin Language and Literature in the Department of Classics at Royal Holloway, University of London. She completed her BA and MP hil in Classics at Newnham College, University of Cambridge, and then earned a second MP hil and her PhD at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. She worked at the University of Birmingham before joining Royal Holloway, where her research focuses on the intersections between Latin literature, ancient philosophy and gender studies. She has a strong specialism in classical reception, and is co-director of the Centre for the Reception of Greece and Rome. She is the author of The Ethics of the Family in Seneca (2017) and Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture (2019), as well as a broad range of chapters and articles.

seneCA

Letters from a Stoic Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium

Selected and Translated by

RoBin CAMPBeLL

With an Introduction by

LiZ gLoYn

Penguin Books

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7 B w

penguin.co.uk

This translation first published in Penguin Classics 1969 Reprinted with minor revisions 1990 and 2004

This edition first published in Penguin Classics 2014 Published with a new Introduction in Penguin Classics 2025 001

Translation copyright © Robin Alexander Campbell, 1969, 1990, 2004 and 2014

Introduction and notes copyright © Liz Gloyn, 2025

The moral rights of the translator and author of the Introduction have been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library is B n : 978–0–140–44210–6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Chronology vii

Introduction ix

Note on Translation and Text xl

LETTERS FROM A STOIC

Appendix: Tacitus’ account of Seneca’s death 279 Index of Persons and Places 283

Su estions for Further Reading 298

Chronology

c. 4 bc Seneca born in Cordoba, Spain.

c. ad 5 Seneca comes to Rome, with his aunt, to live at his family’s home in the city.

ad 14 Augustus dies; Tiberius becomes emperor.

ad 37 Tiberius dies; Gaius (Caligula) becomes emperor.

ad 39 Seneca becomes a quaestor.

ad 41 Gaius dies; Claudius becomes emperor. Seneca exiled to Corsica on charges of adultery with Julia Livilla, sister of Gaius, possibly on instigation of Messalina, third wife of Claudius.

ad 48 Messalina is accused of treason and executed.

ad 49 Claudius marries Agrippina, his fourth wife. Seneca recalled to Rome on Agrippina’s authority to become tutor of her son Nero.

ad 50 Claudius formally adopts Nero as his heir, superseding Britannicus, his son by Messalina.

ad 54 Claudius dies; Nero becomes emperor. Seneca gradually shifts from Nero’s tutor to his amicus, or ‘friend’.

ad 55 Britannicus dies.

ad 59 Nero murders his mother Agrippina.

ad 62 Burrus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard, dies of throat cancer. Seneca begins to withdraw from public life, pleading ill health. His in uence on Nero weakens as that of Tigellinus, the new prefect, increases. Nero divorces his wife, Octavia, and arranges her murder.

ad 63 Nero marries his mistress, Poppaea.

ad 65 Poppaea dies, allegedly after Nero kicks her in the stomach while she is pregnant. Seneca dies by suicide on Nero’s orders, after being implicated in an assassination plot.

ad 68 Nero dies.

Readers will nd an index of people and places mentioned in the Moral Letters at the back of this volume.

Introduction

Seneca: Philosopher and Politician

Seneca was born into an equestrian family with roots in Cordoba in Spain. His father, Seneca the Elder, had been educated in Rome and became a specialist in legal rhetoric.* Seneca the Younger came to Rome with his aunt in about ad 5, where he received a standard Roman rhetorical education.† As a young man, he spent time with various di erent philosophical schools that were then active in Rome, particularly the Sextii, who shared many aspects of their approach with middle Platonism.

Seneca began his political career under Caligula, becoming a quaestor , a junior nancial o cial, in ad 39. Although Caligula at one stage considered having him killed because of the eloquence with which he pleaded a case, Seneca escaped assassination on the grounds that * Seneca the Elder was the author of two collections of legal texts, the Controversies and the Persuasions, usually known by their Latin titles of the Controversiae and the Suasoriae. † Seneca, Consolation to Helvia 19.2.

his ill health meant he wouldn’t survive for long anyway.*

In ad 41, following Caligula’s assassination and Claudius’ succession, Seneca was accused of adultery with Caligula’s sister Julia Livilla and exiled to Corsica.† The initiator of the accusation was probably Messalina, Claudius’ then-wife; after her execution for adultery, Claudius’ new wife Agrippina engineered Seneca’s recall in ad 49 so that he could serve as tutor to her son Nero.‡

When Nero became emperor in ad 54, Seneca became an adviser or amicus to the young ruler, o ering advice and sometimes acting as speechwriter.§ Seneca gradually tried to distance himself from public life as Nero’s reign progressed, ostensibly in order to concentrate on his philosophical work. When a plot to assassinate Nero was uncovered in ad 65, Seneca was implicated along with his nephew Lucan.¶ He died by suicide on Nero’s orders, in a long and di cult process in which he opened his veins, took poison and immersed himself in a hot bath to speed up the process.**

The earliest of Seneca’s philosophical works that survive

* Dio Cassius, 59.19.

† Dio Cassius, 60.8.

‡ Dio Cassius Epitome, 61.32.

§ Dio Cassius Epitome, 61.3; Suetonius, Life of Nero, 7 and 52; cf. Tacitus, Annals, 13.6.

¶ Tacitus, Annals, 15.61.

** Dio Cassius Epitome, 62.25; Suetonius, Life of Nero, 35; Tacitus, Annals, 15.60–64.

x Introduction

Introduction

are his three consolations – To Marcia, To Polybius and To Helvia. These three texts explore the central Stoic concern of how best to deal with loss. The consolation to Marcia was written to console her on the death of her son, with the goal of moving her beyond the grief which had consumed her for the three years since he died; the consolation to Polybius was written shortly after the death of his brother; and the consolation to Helvia, Seneca’s mother, was written to console her over his own absence in exile.

A practical approach to the application of philosophy also appears in Seneca’s other works. On Anger takes the Stoic idea that irrational emotions should be removed and applies it speci cally to anger; Seneca explains why anger is an irrational impulse and should be resisted, as it is the most harmful of all our irrational behaviours. The exchange of bene ts was a key element of Roman social culture; On Bene ts examines, in great detail, what a bene t consists of, how one should give and receive a bene t, and how the moral framework behind exchanging bene ts a ects human interaction. On the Shortness of Life argues that any life, however brief, is enough if it is lived well and with wisdom. The idea that the good life is the wise life is also picked up in On Leisure and On the Happy Life . These works explore questions of the appropriate attitude to wealth and poverty, emphasizing the importance of recognizing what humans need as opposed to what humans want. Seneca himself was considerably wealthy, leading to charges of hypocrisy after

xi

Introduction his death. However, he himself would have been the rst to admit that he was seeking virtue and had not actually achieved it.

Some of Seneca’s work deals with more explicit political concerns. The most obvious example is On Clemency, which is directly addressed to the emperor Nero. In the text, Seneca presents clemency as the imperial virtue par excellence, and outlines the reasons that Nero should behave as leniently as possible to his subjects. The text walks a ne line between exhortation and attery; it also o ers many examples of good and bad rulers as learning aids for the young emperor. A contrasting theme runs through Seneca’s works more broadly, which explore ways in which the aspiring Stoic might distance himself from public life in order to obtain the solitude necessary for philosophical contemplation.

The Natural Questions give the Senecan corpus an extra dimension. The work explores various ancient theories of natural science, including commentary on earthquakes, lightning, snow and comets. In doing so, it serves as a meditation on the world as a whole, and provides a philosophical examination of creation as permeated by the divine.

The Moral Letters takes a completely di erent approach to writing about philosophy, adopting a letter format to communicate key Stoic ideas. The Letters are usually dated as Seneca’s last philosophical work, probably written after he had retired from active political life; as such, they draw on a lifetime of thinking and debating about Stoicism.

A Short Introduction to Stoicism

Seneca was an adherent of Stoicism, a school of philosophy that originated in the fourth century bc in Athens. The name comes from the poikilē stoa, or ‘painted colonnade’, under which the group met to discuss their emerging philosophical principles. That the group’s name comes from the place where they met rather than the person who led them is signi cant; contrast, for instance, the Epicureans, who emerged at around the same time, and are named after their founder. One of Stoicism’s central ideas was that a philosopher should wrestle with ideas and concepts themselves to come to their own conclusion rather than take the word of a prior thinker as authoritative. Thinkers within the school thus often developed Stoic thought in a range of di erent directions despite their shared foundations. In Seneca’s case, he sometimes strikes out on his own to consider the implications of a particular theory, but later Stoics do not always engage with the arguments he makes. This encouragement of independent thought took place within a framework of broadly agreed philosophical concepts. Our evidence for these is badly fragmented. Of the considerable corpus of work attributed to Chrysippus, a prominent pupil of Zeno and Cleanthes, only the titles survive.* Cicero, although not himself a Stoic, attempts to

* These titles are listed in Diogenes Laertius, 7.189–202.

Introduction

represent Stoic theories as part of his philosophical dialogues, albeit in order to disagree with them in good faith. Other writers who cite the Stoics, such as Plutarch, are less generous. They often present small passages in polemical contexts deliberately to refute Stoic ideas. The quotation collection of Stobaeus from the fth century ad provides a compilation of excerpts of moral wisdom for his son and contains many Stoic snippets that appealed to him. It is from these kinds of texts that we can reconstruct the thought of Posidonius and Panaetius, two key gures from around the second century bc, who are usually credited with moving the school’s moral philosophy in a more practical direction. We also have writings that survive from Roman Stoics, like Epictetus, Musonius Rufus and Seneca himself. From this jigsaw of sources, we can reconstruct a basic picture of the major concepts which supported Stoic systems of thought.

The Stoic sage is one of the most important gures in Stoicism and an important anchor for the Moral Letters. The Stoics believe that the sage is the only human who truly achieves virtue, and thus happiness; everyone else is a pro ciens or someone approaching virtue. However, reaching this level of moral achievement is not easy; it was said that the sage was as rare as the phoenix.* The Stoics de ne virtue as the equivalent of acting in accordance with reason, that is, of always following the rational path of action and not being controlled by irrational impulses of the mind. They also describe virtue

* Alexander, De Fato 196.24–197.3, Long and Sedley 61N.

Introduction

in terms of acting in accordance with nature (kata phusin in Greek and secundam naturam in Latin). Nature is considered analogous to reason, as the creator of the world, so acting in accordance with nature is by de nition rational behaviour. The sage is the only person who will always act in accordance with reason, and so is the only person who can truly be called virtuous. Everyone else either acts following irrational impulses or performs the correct actions without the correct moral intentions; in neither of these cases are they acting truly virtuously. Seneca uses the language of acting in accordance with nature as one of his guiding principles in the letters.

The Stoics had a strong position on determinism, namely that this is the best of all possible worlds, because it has been ordered by the divine intelligence which is also found in all living things. Sometimes they identify this divine force with nature, or simply as being visible through nature. They also believed that the universe had a cyclical existence, coming periodically to a mass con agration after which it was reborn and would begin the cycle again. While Seneca does not engage with these ideas closely, they have a major e ect on how he talks about fate or Fortune. According to this world view, whatever fate brings is the most providential outcome; however, as Seneca’s treatment makes clear, fate can also change a person’s position from prosperity to poverty in an instant. Rather than rail against these changes as somehow unfair, Seneca recommends preparing for the possibility of such a reversal, in the spirit of seeing transformations of status as part of a providential universal narrative.

Introduction

The Stoics call the irrational impulses that guide our actions ‘the passions’ or pathē. The four primary passions are appetite, fear, distress and pleasure. The correct approach to them is to replace them with the eupatheiai, the ‘rationally-oriented emotions’ of caution, volition and joy. The pathē arise from a mistaken value judgement about ‘indi erents’ or adiaphora. The Stoics argue that the only truly important and good thing in the world is virtue, and thus its pursuit should be our only concern; everything else, for instance political power or wealth, is an indi erent. A person experiences the pathē when they consider the pursuit of an indi erent more important than the pursuit of virtue, and thus misjudges its importance. A common misunderstanding about the Stoic position is that what is technically called the extirpation of the passions, or reaching a state of apatheia, means suppressing all emotional responses, making the perfect Stoic a sort of impassive robot. This misunderstanding comes from assuming that our modern idea of an emotion means the same as the quite technical Stoic de nition of a passion as a response driven by irrational beliefs. The Stoics do not want us to stop having feelings, but they would like those feelings to be based on the right sort of underlying beliefs and values.

Some indi erents, like good health and an adequate diet, are known as ‘preferred indi erents’. All things being equal, the Stoic sage will select them over the alternatives, such as starvation and sickness. However, they should not take priority over the pursuit of virtue. If behaving in accordance

Introduction

with reason means becoming ill, or even dying by suicide, then the sage will prioritize behaving rationally over retaining the indi erent. For instance, if the sage had to choose between being killed or betraying his friends, and the rational course of action was to die, then the sage would willingly die despite life being a preferred indi erent.

Another key Stoic theory is oikeiōsis, sometimes inadequately translated into English as ‘assimilation’.* This process enables one’s sense of self to expand out from a single individual’s perspective to embrace the whole community of virtuous people, via the intermediate step of assimilating one’s family’s interests to oneself. Strictly speaking, there are two processes to which the name oikeiōsis refers. The rst is that through which a human baby gradually realizes that her limbs belong to her, and that thus she has an interest in their well-being; the second takes that concept of self-interest and extends it from the individual out to those closest to you, so that their interests become your own. This process, ideally, continues to expand, until the sage considers the interests of all humanity to be the same as her own.

One consequence of the completed process of oikeiōsis is the cosmopolis. Stoics de ne the cosmopolis as a conceptual universal city which contains all beings who have perfect grasp of reason. This includes the gods (who are, by

* See Inwood 1999: 677 n.8 for the issues involved in translating this word accurately.

de nition, embodiments of reason in the Stoic scheme of things) as well as virtuous sages. Arguably, every human being has the potential to join the cosmopolis, although that membership is only activated by full exercise of reason; the cosmopolis thus exists, although its citizens may be small in number. The cosmopolis provides a sense of identity grounded in a person’s nature as a rational human being, rather than in allegiances to the temporal world, which is ultimately indi erent to the pursuit of virtue. While Seneca does not explicitly engage with the idea of the cosmopolis in the letters included in this volume’s selection, the fact that each person has the same underlying potential for virtue informs several of the letters included here, including the famous Letter 47 concerning the proper treatment of enslaved people. This position did not preclude the Stoics from participating in the political systems of the states in which they happened to live, and some strands of Stoic thought encourage political participation as a way to exercise virtue and encourage others to do the same; however, political success would be categorized as an indi erent.

I should say a word here about the Stoics and gender equality. While Seneca speaks exclusively of ‘the wise man’, and most of his examples in the Moral Letters feature men, the Stoics believed that women and men had an equal potential for virtue. Indeed, in his consolations to Marcia and Helvia, Seneca speci cally writes to women about their philosophical and moral well-being in extremely positive terms. Some readers nd passages where Seneca uses casually sexist language,

xviii Introduction

Introduction

for instance in Letter 78 where he critiques su ering pain in ‘a womanish fashion’, at odds with this position. This type of language re ects the embedded misogyny of the idioms and values of Rome, in which Seneca was thoroughly steeped. While some of the Moral Letters can feel directed towards men, particularly given Campbell’s translation practice (for instance, ‘mankind’ rather than ‘humankind’ even when the original Latin may be closer to the latter), the underlying principles of how to acquire virtue are applicable to all.

A parallel issue arises subtly from time to time, and most explicitly in Letter 123, the nal one in this selection. Here, Seneca critiques those who use Stoicism as camou age for wicked behaviour and gives as an example a person who asks up to what age it is proper to love young men; he dismisses that question as being acceptable for the Greeks, but says Roman Stoics have better questions with which to concern themselves. This kind of statement has to be read in the context of a philosophical tradition which, since Plato, had considered the social appropriateness of pederasty, where a younger man had an erotic relationship with an older man. Such relationships have since been interpreted as either benecial mentoring or sexually abusive. Roman Stoics sought to move discussions of love away from relationships between men to those between husband and wife, and this shift had been mostly completed by the time Seneca was writing. While Seneca tends to characterize age asymmetric relationships of this kind as being against nature, his comments cannot be understood as condemning all homosexual relationships.

xix

Why Letters?

The Moral Letters take the form of a correspondence between Seneca and his friend Lucilius. We know very little about Lucilius, other than that he belonged to the equestrian class and was also the addressee of the Natural Questions and On Providence. When the Moral Letters begin, he is governor of Sicily, although he appears to retire from public life on Seneca’s advice during the course of the collection. However, the Moral Letters only give us Seneca’s side of the correspondence. There are 124 letters in the surviving collection, organized into twenty books of varying lengths. We know this was not the full collection; for instance, Aulus Gellius preserves an excerpt of a letter from book 22.* However, we do not know how long the collection was in its complete form, or the content of the missing letters.

Much ink has been spilled on whether these letters represent, in full or in part, a genuine historical correspondence, like the letters of Cicero. It is easy to understand the temptation to read them as representing the inner thoughts and feelings of the ‘real’ Seneca, in as much as we can ever know the innermost thoughts of someone who lived centuries before us. Perhaps that temptation is intensi ed because in the case of Marcus Aurelius, another famous Roman Stoic, we really do appear to have access to

* Aulus Gellius, 12.2.

Introduction

someone’s private musings and re ections. However, the general scholarly consensus is now that the letters are literary creations, that they are unlikely to have ever been sent, and that we should understand Seneca and Lucilius as characters in them rather than historical gures, a virtuous equivalent of C. S. Lewis’ Screwtape and Wormwood rather than people exchanging a genuine correspondence. In choosing to use the letter form for communicating philosophical ideas, Seneca joined a long tradition of earlier thinkers who had also used this format. There are a series of letters attributed to Plato, for instance (even if they are now assumed to be attributed to him rather than written by him); Epicurus, the founder of Epicureanism, also made great use of letters in his own work.

The other interpretative risk in accepting that the letters are a literary production is to try and nd ways of understanding them that ignore the fact they are letters. This approach tends to lead to reading the letters as free-standing miniature essays, each self-contained in isolation, taking an individual theme or idea and developing it to Seneca’s satisfaction. An alternative but aligned reading sees the letters as having a primarily educational goal; this understands the letters in terms of the relationship between Seneca and Lucilius, prioritizing the moments where Seneca positions himself as an authoritative voice who is leading Lucilius through a set didactic programme in order to deliver a thoroughly Stoic curriculum. Neither of these approaches is willing to grapple with what it means for the

Introduction

Moral Letters to be letters, and as such underplay other features which are key to their construction and nature. What is key to understanding the letters is that, like regular correspondence, they have a rich and varied texture. On both the level of the collection and the individual letter, they skip from idea to idea, shift their tone, abandon topics only to return to them later, and switch from intimate confessional to abstract concepts. The reader encounters Seneca’s voice in a range of modes – formal, casual, bitingly sarcastic. Each letter must, by de nition, be comparatively compact, a clear contrast to the longer multi-book form of (for instance) On Anger or On Bene ts; yet the brevity of the form does not prevent Seneca from packing a great deal into each letter. Indeed, part of the point of the letter sequence is to allow Seneca to think through issues – to write through them – as he returns to ideas he has handled in earlier letters with more sophistication or a di erent angle, giving the impression of an evolving conversation between the correspondents.

Taking the letters as essays, or alternatively as some kind of Stoicism-by-Post instruction course, also minimizes the role that the reader must necessarily take in them. A letter, as a medium of communication, expects a reply. The absence of Lucilius’ letters creates a space for the reader both to put themselves into Lucilius’ sandals and to consider their own response to the material. The way that the letters, individually and collectively, transition between themes and ideas demands an active reader, who makes their own links and connections between the content of

the letters. The idea of the ‘correspondence course’, in which a recipient passively follows instructions to gain the desired end, is (it turns out) the complete opposite of what the reader of Seneca’s letters has to do. This is very much in line with general Stoic principles of education, which resisted giving set precepts or rules for adherents to follow; instead, aspiring Stoics were encouraged to work out the best course of action for their speci c circumstances based on their deep understanding of foundational principles.

The nature of this current volume poses a nal question about the letter format. Seneca organized the letters with an internal structure and logic, so that a reader working through the letters sequentially can appreciate the gradual build-up and reiteration of the themes and ideas he expounds, as well as the wide range of other literary features that he includes. In the original compilation of this volume, Robin Campbell selected forty-two letters based on his own selection criteria which, sadly, he did not elaborate in his original introduction. Is it still possible to read the Moral Letters in a selection like this, removed from the overall structure in which they were originally placed?

My answer here is a cautious yes. I remain cautious because this selection is only a part of the wider collection, and as such some elements must inevitably be lost in the selection process. Campbell also has a tendency to excise sections of the longer letters which he deems irrelevant or unhelpful; these omissions are marked in the text. Ultimately I answer yes, because the continual developments of

central themes over the sequence of the letters means that this volume gives a good sense of the key ideas contained in the collection as a whole, even if the reader misses some points of iteration. Campbell kept the letters in their original chronological order, allowing that organic growth of ideas and concepts to be partially mirrored. The letters are also drawn from the full range of the Moral Letters, beginning at Letter 2 and ending at Letter 123, giving a rst-time reader good coverage of the scope of the collection. I would invite the modern reader to understand this volume in their hands as a sample of the Moral Letters, a taster menu, and to take it as an invitation to sample the full range of what they have to o er at some later stage.

Key Themes in the Correspondence

The nature of the letter collection means that key ideas are repeated, revisited and reintegrated as the reader makes their way through the text. The selection included in this volume highlights the key ideas that Seneca explores in the Moral Letters as a whole. The selection also highlights how he moves from theme to theme as the letters progress; a letter may focus on a single theme at some length, or it may weave together several di erent ideas in varying combinations to draw out a particular idea. While I would refrain from seeking to neatly pigeonhole each letter as belonging to a particular subset of ideas, as this is not in the nature of most correspondence,

Introduction

there are some central themes which are worth watching out for in the letters in this particular selection. The rst major theme to highlight is that of study. Given that the purpose of the collection is to urge Lucilius and the reader onwards in the study of philosophy, and Stoicism speci cally, this should not come as a surprise. Seneca talks often about the pleasures of a good book, even to the extent of confessing he had lost himself in one that Lucilius recommended (Letter 41). However, he does not shy away from admitting that the study of philosophy requires work and regular e ort. He talks frequently about the need to pay attention to philosophical enquiry and to devote one’s whole self to it, with the reward of knowing how to live well (cf. Letter 90). He spurs on Lucilius not to lose his enthusiasm and to keep at it, suggesting various study strategies that will help him achieve his goal. In the world that Seneca paints of his own life, he also presents engaging with reading, writing and talking about Stoicism as central and regular parts of his daily routine. For instance, in Letter 65 he talks about doing a little bit of reading and writing before his friends arrived to begin a lengthy conversation about a technical Stoic matter over which he invites Lucilius to arbitrate.

Nonetheless, one of the major strategies that Seneca advocates is not getting distracted by intellectual rabbit holes, or meaningless minutiae. For instance, in Letter 108 Seneca explicitly tells Lucilius to bring his enthusiasm for learning under control. The point Seneca wants to make is that Lucilius should learn what he needs to learn, and no

more; otherwise it would be very easy to spend time on nitpicking details that do not, in fact, bring us closer to virtue. A similar theme emerges in the discussion of the liberal arts in Letter 88, where Seneca argues that the only true liberal art is philosophy, and that nothing else counts unless it draws us closer to virtue. In these contexts, he is scathing about the kind of philological studies that seek, for instance, to establish the relative ages of Patroclus and Achilles, or why Hecuba didn’t age gracefully even though she was younger than Helen. He is equally unimpressed by philosophical quibbling, such as spending time on the word games of syllogisms rather than considering guidance for how to live (Letter 48; see also Letter 83). The point is to focus your intellectual energies on subjects worthy of them. The emphasis on the importance of study arises from the need for Lucilius to gain intellectual independence as a thinker. It is not enough for him to rely on the short sayings of wisdom with which the early letters conclude. Indeed, in Letter 33 Seneca addresses Lucilius’ complaint that he has stopped included these pat ending apothegms for easy digestion. This letter helpfully outlines that the point of Stoic study is for Lucilius to become an intellectually independent adult, who draws on a shared treasury of intellectual ideas, but ultimately makes his own judgements and decisions based on his study instead of relying on being spoon-fed these bite-sized ideas. Already from early in the collection, Seneca lays out for Lucilius the path on which they walk together – not as student and teacher,

Introduction

but as co-enquirers into virtue, with their individual moral strengths and weaknesses.

The end-of-letter tags have been part of a wider question about Seneca’s relationship to Epicureanism. Seneca attributes to Epicurus many of the pithy sayings with which he closes his early letters. The rst letter in this selection, Letter 2, ends with the Epicurean motto that ‘cheerful poverty is an honourable state’. Epicurus is also a signi cant interlocutor in other letters; for instance, Letter 9 explicitly addresses Epicurus’ critique of the wise man’s su ciency. Epicurus was the founding thinker of the Epicurean school, who saw pleasure rather than virtue as the ultimate goal of human life. Although Epicureanism has become associated with pure hedonism in contemporary culture, the ancient Epicureans instead strove to gain as much happiness as possible by making their threshold for happiness as low as possible. For instance, they noted that if you experienced happiness when drinking ne wine, you would experience pleasure much less often than if you had the same sensation from slaking your thirst with water. Seneca’s frequent dialogue with Epicurus and Epicurean ideas was one reason why academics in the mid-twentieth century interpreted him as an eclectic philosopher, one who lifted ideas from various di erent philosophical schools rather than being a strong adherent of just one.

Certainly, Seneca’s own description of his intellectual beginnings, including a irtation with vegetarianism inspired by the Pythagorean thought of Sextius and Sotion,

xxviii Introduction in Letter 108 might lead us in this direction, but it’s worth remembering Seneca is describing his teenage years rather than his mature self. Similarly, the intellectual environment at Rome involved plenty of give and take between di erent philosophical schools, with lively debates and public discussions a regular feature of the literary (and social) calendar. In fact, in Letter 2, Seneca reassures Lucilius that he has gone over into ‘the enemy’s camp’ to fetch his tag as a scout on reconnaissance, not as a deserter; in Letter 33, rebuking Lucilius for still wanting to be given sayings, he notes that good ideas come into general ownership, and do not belong exclusively to any one group. It’s not surprising to nd Seneca engaging explicitly with Epicurus, as the Stoics and Epicureans very much positioned themselves as rival philosophical schools. The relationship should be understood in terms of ongoing dialogue and debate in which Seneca remains rmly on the Stoic side, whilst recognizing areas in which the two schools overlap in their thinking. While one goal of philosophy is to learn how to live well, the Stoics also believed it taught us how to die well. Given that this is the last of Seneca’s philosophical works, it is perhaps not surprising that a major theme within the corpus is ageing and death; in some ways, the Moral Letters are deeply re ective about Seneca’s own experience of ageing. Letter 12 is entirely about encounters that have prompted him to ponder his own mortality, like seeing trees he remembers planting now drying out and withering. Similarly, Letter 26 re ects on the inevitability of old

Introduction

age. Both letters, and others that explore this theme, emphasize the importance of preparing to die, and being ready to die well when the time comes, rather than living in denial of this fact. An intertwined motif with the bodily frailty of old age is that of sickness, both of body and of mind. Seneca himself lived with chronic physical conditions, which leads to discussions of how his experiences with asthma and gasping for breath have helped him prepare for death (Letter 54). He has no qualms about accepting his own physical limitations; his frank description of his own seasickness in Letter 53 can come as quite a shock to readers expecting him to maintain a certain philosophical dignity! But that experience leads him into a deeper re ection on how easy it is to gloss over both our physical and mental illnesses, and the need to allow our souls time to heal properly just as we would allow it to our bodies.

The themes of ageing and study intertwine as Seneca describes his experience of retirement from court. (It is worth noting, in passing, that Nero does not make a major impact on the Moral Letters as a whole.) Letter 8 speci cally frames his retirement from active political life as a way for him to be more use to society by producing philosophical literature to guide others. He even goes as far as arguing that he does more good through his writing than he would by attending the Senate. He argues that just because he has retired from public life does not mean he is inactive – yet this move to intellectual activity is bound up in his ageing. Letter 55 restates the di erence between retiring and living

Introduction for yourself. In Letter 77 Seneca notes he wasn’t particularly interested when long-awaited boats from Alexandria carrying post arrived at Puteoli, because in his old age he has lost interest in his nancial losses and gains – all he requires is enough to sustain the remainder of his life. The collection re ects a fundamental change of perspective as Seneca looks back over his life and considers his priorities – presumably not unaware of the number of coerced deaths that Nero enforced, and the reality of death being a close companion whether through physical ailment or imperial whim. As such, the collection’s emphasis on how to deal with the death of others is also re ected in this volume’s selection. The Stoics are sometimes accused of being cold to other people and treating human relationships as disposable. This is a misinterpretation of how they approach death in terms of the doctrine of indi erents I outlined above. Letter 58 provides a good summary of the Stoic position. Seneca writes to Lucilius in condolence on the death of his friend Flaccus. While he does discourage Lucilius from grieving excessively, he encourages him to take pleasure in the memories of his friend, as a gift he was given but that Fortune has now taken away. He also points out the hypocrisy of not paying attention to friends when they are alive and then being overcome with hysterical grief when they die; the performative demonstration of a relationship doesn’t match up to how a person nurtured a friendship during life. The message of the letter, and the Stoics’ views on death and grief in general, is not that the

Introduction

wise man should not mourn and feel loss, but that he should put it in the perspective of the workings of Fortune in his life; take pleasure in the memories of the departed friend; and be sustained by the other relationships that he has nurtured and still enjoys.

These kinds of re ections take us to the collection’s thinking on hardship, poverty, and the capriciousness of Fortune. The idea that what had been given to us can be taken away was so ingrained that Seneca actually quotes a line of poetry expressing this thought that he attributes to Lucilius himself at the end of Letter 8; this follows a lengthy exploration of the same concept as expressed in Epicurus’ work. He immediately follows this idea up in Letter 9 with the example of Stilbo, whose town was destroyed and family was slaughtered by the Macedonian king Demetrius. When Demetrius asked Stilbo if he had lost anything, he replied ‘nothing’. Again, this might be interpreted as evidence of a Stoic remoteness from human realities, but what Seneca is alluding to is that Stilbo is both entirely reliant on himself for happiness and was prepared for the loss of things that had been given to him by Fortune. Seneca returns to the motif of the ruin of cities in Letter 91, which focuses on his friend Liberalis’ distress following the destruction of Lyons by re. The irony that this happens in peacetime rather than in the midst of war is not lost on him, but he uses this disaster as a reminder that Fortune strikes whenever she wishes, with no warning, and that her attacks can take many forms. A central lesson is that nothing lasts,

whether in the lives of people or cities; it is possible to tip from prosperity to destitution overnight.

While this attitude may feel almost nihilistic at times, Seneca o ers a solution. In Letter 91, he advises Lucilius to rehearse the misfortunes that might befall him – he lists exile, torture, war and shipwreck as possibilities. Such anticipation of things that commonly occur to people should mean that when they do happen, our internal stability is not disturbed and, like Stilbo, we are able to continue living without feeling we have been wronged. A similar encouragement to practise for poverty comes in Letter 18, in which Seneca advises Lucilius to regularly set aside a certain number of days when he wears rough clothing and eats only the plainest food, in order to acclimatize himself to those conditions should he be pitched into them, and to realize that they are not in fact so bad. This advice has been critiqued for having more of a whi of Marie Antoinette and her pseudo-shepherdess’ cottage about it, for cos-playing poverty whilst in the lap of luxury. To give Seneca his due, he explicitly says that this practice shouldn’t be a mere amusement and should last long enough to be a proper trial, but it remains to be seen just how meaningful this kind of imitation poverty would be for anticipating the real thing. That said, the practice of envisioning what might happen in a particularly disastrous circumstance and considering what that might be like is very similar to some of the practices adopted in modern cognitive-behavioural therapy, with the shared goal of reducing anxiety about catastrophic scenarios we might encounter. Certainly, it seems

xxxii Introduction

Introduction

to work for Seneca, or so he claims in Letter 123. When he arrives at his house in Alba to nd nothing ready for him except himself, he can cheerfully make do with what is available without getting upset about it and sees the experience as an unexpected test of how well his spirit is prepared for such inconveniences, albeit of a minor sort.

On the opposite side of the spectrum to extreme poverty lies the collection’s interest in luxury and corruption. The risk of moral corruption surrounds us simply by existing in society; hence one reason that Seneca emphasizes the importance of spending time with friends who improve us. A contrasting example occurs in Letter 7, where Seneca famously lambasts the pernicious in uences of attending gladiatorial displays. After being surrounded by a large group of people behaving badly as they watch mindless slaughter, it’s no wonder he complains about going home feeling crueller and less humane as a result. A similar sense of group-think, or being drawn along by those you spend time with, emerges in Letter 122, which critiques those who live their lives at night and sleep during the day, seeing it as a vice particularly of the young who wish to be modish and get noticed. The problem is that in their desire for notoriety, they lose sight of what is natural, and so end up living back to front.

The idea that excessive luxury and the vices attendant on it are a feature of Seneca’s own time is frequently repeated in this volume’s selection of letters. This is a running theme in Letter 90, which disagrees with Posidonius’ position that philosophers were behind many of the inventions that have

led to progress, and instead argues that human ingenuity has meant we have forgotten how to live within the limits set by nature. Seneca adopts a similar tone in his discussion of the bathhouse at Scipio Africanus’ villa as he tells Lucilius about his visit there in Letter 86. The dingy and functional amenities that suited Scipio are contrasted at length with the huge windows, marble tiling and silver taps found as standard in modern Roman bathrooms. The implication is that if such simple arrangements were good enough for Scipio, the general attributed with Rome’s victory over Carthage in the Second Punic War, then they are good enough for everyone. Seneca’s hyperbolic and satirical tone is unmistakable in the description of luxurious bathing arrangements, and indeed pervades many of his other discussions of indulgent living. He is similarly scathing in Letter 27 about Calvisius, an obscenely rich freedman who spent an extortionate amount of money on enslaved people who each had memorized the complete works of a famous literary writer, but never engaged with the texts directly himself.

Luxury doesn’t just manifest in physical possessions; it turns up in writing and oratory as well, interlinking again with the collection’s interest in study and learnedness. In our selection, this aspect of degeneracy comes out particularly in Letter 40 and Letter 114. The former concentrates on the style of people giving speeches; it emphasizes the importance of using plain and simple language to communicate ideas rather than an overwrought and owery style. The latter responds to a query posed by Lucilius about why

xxxiv Introduction