PA R T ONE SENATOR

‘Urbem,

urbem, mi Rufe, cole et in ista luce vive!’

‘Rome! Stick to Rome, my dear fellow, and live in the limelight!’

Cicero, letter to Caelius, 26 June 50 bc

MIy name is Tiro. For thir ty-six years I was the confidential secretar y of the Roman statesman Cicero. At first this was exciting, then astonishing, then arduous, and finally extremely dangerous. During those years I believe he spent more hours with me than with any other person, including his own family. I witnessed his private meetings and carried his secret messages. I took down his speeches, his letters and his literary works, even his poetr y – such an outpouring of words that I had to invent what is commonly called shorthand to cope with the flow, a system still used to record the deliberations of the senate, and for which I was recently awarded a modest pension. This, along with a few legacies and the kindness of friends, is sufficient to keep me in my retirement. I do not require much. The elderly live on air, and I am ver y old – almost a hundred, or so they tell me.

In the decades after his death, I was often asked, usually in whispers, what Cicero was really like, but always I held my silence. How was I to know who was a government spy and who was not? At any moment I expected to be purged. But since my life is almost

over, and since I have no fear of anything any more –not even torture, for I would not last an instant at the hands of the carnifex or his assistants – I have decided to offer this work as my answer. I shall base it on my memory, and on the documents entrusted to my care. Because the time left to me inevitably must be short, I propose to write it quickly, using my shorthand system, on a few dozen small rolls of the finest paper – Hieratica, no less – which I have long hoarded for the purpose. I pray forgiveness in advance for all my errors and infelicities of style. I also pray to the gods that I may reach the end before my own end overtakes me. Cicero’s final words to me were a request to tell the truth about him, and this I shall endeavour to do. If he does not always emerge as a paragon of virtue, well, so be it. Power brings a man many luxuries, but a clean pair of hands is seldom among them.

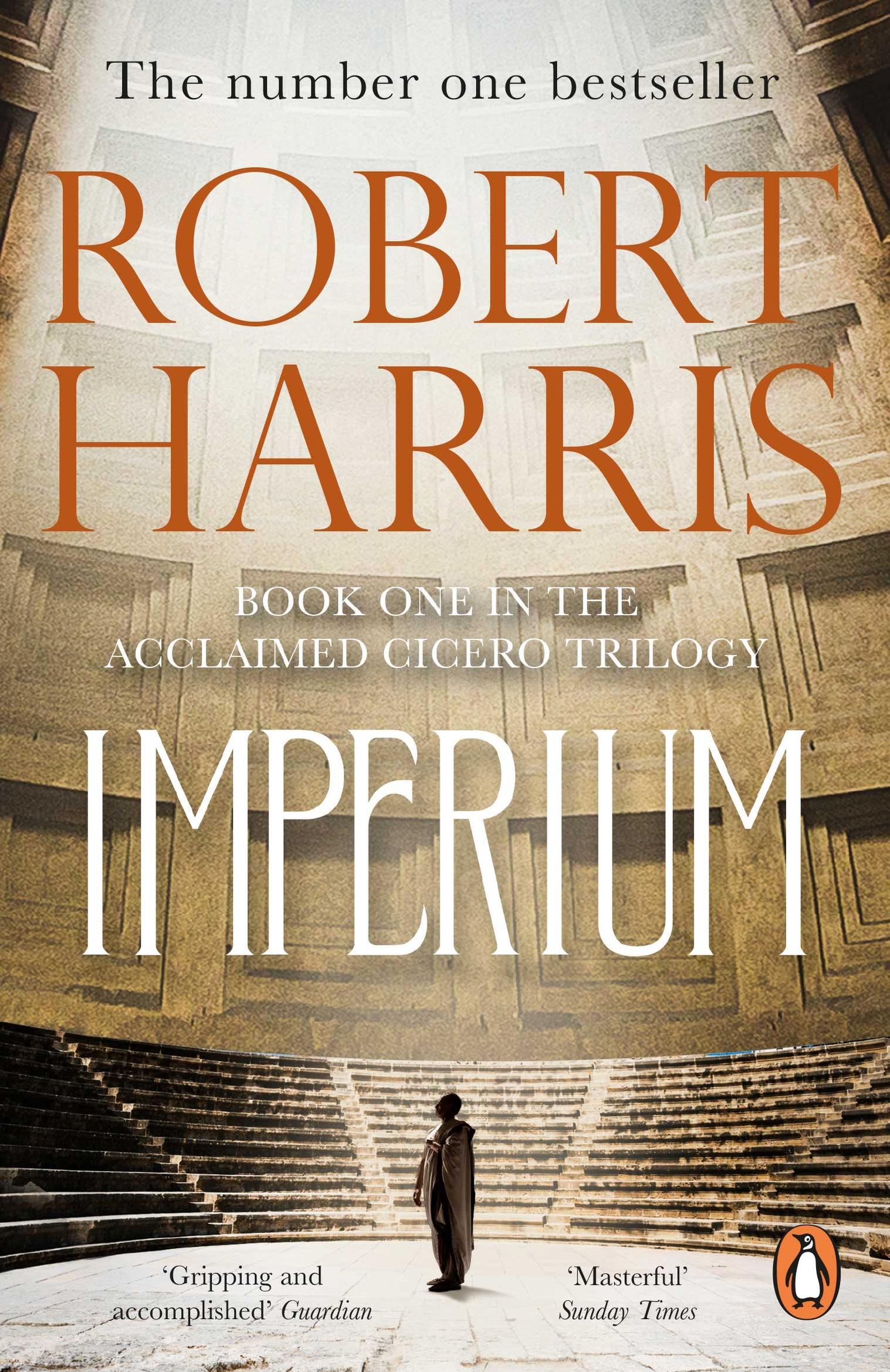

And it is of power and the man that I shall sing. By power I mean official, political power – what we know in Latin as imperium – the power of life and death, as vested by the state in an individual. Many hundreds of men have sought this power, but Cicero was unique in the history of the republic in that he pursued it with no resources to help him apart from his own talent. He was not, unlike Metellus or Hortensius, from one of the great aristocratic families, with generations of political favours to draw on at election time. He had no mighty army to back up his candidacy, as did Pompey or Caesar. He did not have Crassus’s vast fortune to grease his path. All he had was his voice – and by sheer

effort of will he turned it into the most famous voice in the world.

Iwas twenty-four years old when I entered his ser vice. He was twenty-seven. I was a household slave, born on the family estate in the hills near Arpinum, who had never even seen Rome. He was a young advocate, suffering from ner vous exhaustion, and struggling to overcome considerable natural disabilities. Few would have wagered much on either of our chances.

Cicero’s voice at this time was not the fearsome instrument it later became, but harsh and occasionally prone to stutter. I believe the problem was that he had so many words teeming in his head that at moments of stress they jammed in his throat, as when a pair of sheep, pressed by the flock behind them, tr y at the same time to squeeze through a gate. In any case, these words were often too highfalutin for his audience to grasp. ‘The Scholar’, his restless listeners used to call him, or ‘the Greek’ – and the terms were not meant as compliments. Although no one doubted his talent for orator y, his frame was too weak to carr y his ambition, and the strain on his vocal cords of several hours’ advocacy, often in the open air and in all seasons, could leave him rasping and voiceless for days. Chronic insomnia and poor digestion added to his woes. To put it bluntly, if he was to rise in politics, as he desperately wished to do, he needed professional help. He therefore decided to spend some time away from Rome,

travelling both to refresh his mind and to consult the leading teachers of rhetoric, most of whom lived in Greece and Asia Minor.

Because I was responsible for the upkeep of his father’s small librar y, and possessed a decent knowledge of Greek, Cicero asked if he might borrow me, as one might remove a book on loan, and take me with him to the East. My job would be to super vise arrangements, hire transport, pay teachers and so forth, and after a year go back to my old master. In the end, like many a useful volume, I was never returned.

We met in the harbour of Brundisium on the day we were due to set sail. This was during the consulship of Ser vilius Vatia and Claudius Pulcher, the six hundred and seventy-fifth year after the foundation of Rome. Cicero then was nothing like the imposing figure he later became, whose features were so famous he could not walk down the quietest street unrecognised. (What has happened, I wonder, to all those thousands of busts and portraits, which once adorned so many private houses and public buildings? Can they really all have been smashed and burned?) The young man who stood on the quayside that spring morning was thin and round-shouldered, with an unnaturally long neck, in which a large Adam’s apple, as big as a baby’s fist, plunged up and down whenever he swallowed. His eyes were protuberant, his skin sallow, his cheeks sunken; in short, he was the picture of ill health. Well, Tiro, I remember thinking, you had better make the most of this trip, because it is not going to last long.

We went first to Athens, where Cicero had promised himself the treat of studying philosophy at the Academy. I carried his bag to the lecture hall and was in the act of turning away when he called me back and demanded to know where I was going.

‘To sit in the shade with the other slaves,’ I replied, ‘unless there is some further ser vice you require.’

‘Most certainly there is,’ he said. ‘I wish you to perform a ver y strenuous labour. I want you to come in here with me and learn a little philosophy, in order that I may have someone to talk to on our long travels.’

So I followed him in, and was privileged to hear Antiochus of Ascalon himself assert the three basic principles of stoicism – that virtue is sufficient for happiness, that nothing except virtue is good, and that the emotions are not to be trusted – three simple rules which, if only men could follow them, would solve all the problems of the world. Thereafter, Cicero and I would often debate such questions, and in this realm of the intellect the difference in our stations was always forgotten. We stayed six months with Antiochus and then moved on to the real purpose of our journey.

The dominant school of rhetoric at that time was the so-called Asiatic method. Elaborate and flower y, full of pompous phrases and tinkling rhythms, its deliver y was accompanied by a lot of swaying about and striding up and down. In Rome its leading exponent was Quintus Hor tensius Hor talus, universally considered the foremost orator of the day, whose fancy footwork had earned him the nickname of ‘the Dancing

Master’. Cicero, with an eye to discovering his tricks, made a point of seeking out all Hortensius’s mentors: Menippus of Stratonicea, Dionysius of Magnesia, Aeschylus of Cnidus, Xenocles of Adramyttium – the names alone give a flavour of their style. Cicero spent weeks with each, patiently studying their methods, until at last he felt he had their measure.

‘Tiro,’ he said to me one evening, picking at his customar y plate of boiled vegetables, ‘Ihave had quite enough of these perfumed prancers. You will arrange a boat from Lor yma to Rhodes. We shall tr y a different tack, and enrol in the school of Apollonius Molon.’

And so it came about that, one spring morning just after dawn, when the straits of the Carpathian Sea were as smooth and milky as a pearl (you must forgive these occasional flourishes: I have read too much Greek poetry to maintain an austere Latin style), we were rowed across from the mainland to that ancient, rugged island, where the stocky figure of Molon himself awaited us on the quayside.

This Molon was a lawyer, originally from Alabanda, who had pleaded in the Rome courts brilliantly, and had even been invited to address the senate in Greek – an unheard-of honour – after which he had retired to Rhodes and opened his rhetorical school. His theor y of orator y, the exact opposite of the Asiatics’, was simple: don’t move about too much, hold your head straight, stick to the point, make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, and when you ’ ve won their sympathy, sit down quickly –‘For nothing,’ said Molon, ‘dries more quickly than a

tear.’ This was far more to Cicero’s taste, and he placed himself in Molon’s hands entirely.

Molon’s first action was to feed him that evening a bowl of hard-boiled eggs with anchovy sauce, and, when Cicero had finished that – not without some complaining, I can tell you – to follow it with a lump of red meat, seared over charcoal, accompanied by a cup of goat’s milk. ‘ You need bulk, young man,’ he told him, patting his own barrel chest. ‘No mighty note was ever sounded by a feeble reed.’ Cicero glared at him, but dutifully chewed until his plate was empty, and that night, for the first time in months, slept soundly. (I know this because I used to sleep on the floor outside his door.)

At dawn, the physical exercises began. ‘Speaking in the forum,’ said Molon, ‘is comparable to running in a race. It requires stamina and strength.’ He threw a fake punch at Cicero, who let out a loud ‘Oof ! ’ and staggered backwards, almost falling over. Molon had him stand with his legs apart, his knees rigid, then bend from the waist twenty times to touch the ground on either side of his feet. After that, he made him lie on his back with his hands clasped behind his head and repeatedly sit up without shifting his legs. He made him lie on his front and raise himself solely by the strength of his arms, again twenty times, again without bending his knees. That was the regime on the first day, and each day after wards more exercises were added and their duration increased. Cicero again slept soundly, and now had no trouble eating, either.

For the actual declamator y training, Molon took his eager pupil out of the shaded courtyard and into the heat of midday, and had him recite his exercise pieces – usually a trial scene or a soliloquy from Menander –while walking up a steep hill without pausing. In this fashion, with the lizards scattering underfoot and only the scratching of the cicadas in the olive trees for an audience, Cicero strengthened his lungs and learned how to gain the maximum output of words from a single breath. ‘Pitch your deliver y in the middle range,’ instructed Molon. ‘ That is where the power is. Nothing too high or low.’ In the afternoons, for speech projection, Molon took him down to the shingle beach, paced out eighty yards (the maximum range of the human voice) and made him declaim against the boom and hiss of the sea – the nearest thing, he said, to the murmur of three thousand people in the open air, or the background mutter of several hundred men in conversation in the senate. These were distractions Cicero would have to get used to.

‘But what about the content of what I say?’ Cicero asked. ‘Surely I will compel attention chiefly by the force of my arguments?’

Molon shrugged. ‘Content does not concern me. Remember Demosthenes: “Only three things count in orator y. Deliver y, deliver y, and again: deliver y. ”’

‘And my stutter?’

‘The st-st-stutter does not b-b-bother me either,’ replied Molon with a grin and a wink. ‘Seriously, it adds interest and a useful impression of honesty.

Demosthenes himself had a slight lisp. The audience identifies with these flaws. It is only perfection which is dull. Now, move further down the beach and still tr y to make me hear.’

Thus was I privileged, from the ver y start, to see the tricks of orator y passed from one master to another. ‘There should be no effeminate bending of the neck, no twiddling of the fingers. Do not move your shoulders. If you must use your fingers for a gesture, tr y bending the middle finger against the thumb and extending the other three – that is it, that is good. The eyes of course are always turned in the direction of the gesture, except when we have to reject: “O gods, avert such plague!” or “I do not think that I deser ve such honour.”’

Nothing was allowed to be written down, for no orator worthy of the name would dream of reading out a text or consulting a sheaf of notes. Molon favoured the standard method of memorising a speech: that of an imaginar y journey around the speaker’s house. ‘Place the first point you want to make in the entrance hall, and picture it lying there, then the second in the atrium, and so on, walking round the house in the way you would naturally tour it, assigning a section of your speech not just to each room, but to ever y alcove and statue. Make sure each site is well lit, clearly defined, and distinctive. Other wise you will go groping around like a drunk tr ying to find his bed after a party.’

Cicero was not the only pupil at Molon’s academy that spring and summer. In time we were joined by

Cicero’s younger brother Quintus, and his cousin Lucius, and also by two friends of his: Ser vius, a fussy lawyer who wished to become a judge, and Atticus –the dapper, charming Atticus – who had no interest in orator y, for he lived in Athens, and certainly had no intention of making a career in politics, but who loved spending time with Cicero. All mar velled at the change which had been wrought in his health and appearance, and on their final evening together – for now it was autumn, and the time had come to return to Rome –they gathered to hear the effects which Molon had produced on his orator y.

I wish I could recall what it was that Cicero spoke about that night after dinner, but I fear I am the living proof of Demosthenes’ cynical assertion that content counts for nothing beside deliver y. I stood discreetly out of sight, among the shadows, and all I can picture now are the moths whirling like flakes of ash around the torches, the wash of stars above the courtyard, and the enraptured faces of the young men, flushed in the firelight, turned towards Cicero. But I do remember Molon’s words after wards, when his protégé, with a final bow of his head towards the imaginar y jur y, sat down. After a long silence he got to his feet and said, in a hoarse voice: ‘Cicero, I congratulate you and I am amazed at you. It is Greece and her fate that I am sorr y for. The only glor y that was left to us was the supremacy of our eloquence, and now you have taken that as well. Go back,’ he said, and gestured with those three outstretched fingers, across the lamp-lit terrace to the

dark and distant sea, ‘go back, my boy, and conquer Rome.’

Very well, then. Easy enough to say. But how do you do this? How do you ‘conquer Rome’ with no weapon other than your voice?

The first step is o b vio us: y ou must become a senator.

To gain ent r y to the senate at that time it was necessar y to be at least thirty-one years old and a millionaire. To be exact, assets of one million sesterces had to be shown to the authorities simply to qualify to be a candidate at the annual elections in July, when twenty new senators were elected to replace those who had died in the previous year or had become too poor to keep their seats. But where was Cicero to get a million? His father certainly did not have that kind of money: the family estate was small and heavily mortgaged. He faced, therefore, the three traditional options. But making it would take too long, and stealing it would be too risky. Accordingly, soon after our return from Rhodes, he married it. Terentia was seventeen, boyishly flat-chested, with a head of short, tight black curls. Her half-sister was a vestal virgin, proof of her family’s social status. More importantly, she was the owner of two slum apartment blocks in Rome, some woodland in the suburbs, and a farm; total value: one and a quarter million. (Ah, Terentia: plain, grand and rich – what a piece of work you were! I saw her only a few months

ago, being carried on an open litter along the coastal road to Naples, screeching at her bearers to make better speed: white-haired and walnut-skinned but other wise quite unchanged.)

So Cicero, in due course, became a senator – in fact, he topped the poll, being generally now regarded as the second-best advocate in Rome, after Hor tensius – and then was sent off for the obligator y year of government ser vice, in his case to the province of Sicily, before being allowed to take his seat. His official ti tle was quaestor, the most junior of the magistracies. Wives were not permitted to accompany their husbands on these tours of duty, so Terentia – I am sure to his deep relief – stayed at home. But I went with him, for by this time I ha d become a kind of extension of himself, to be used unthinkingly, like an extra hand or foot. Par t of the reason for my indispensability was that I had devised a method of taking down his words as fast as he could utter them. From small beginnings – I can modestly claim to be the man who invented the ampersand – my system eventually swelled to a handbook of some four thousand symbols. I found, for example, that Cicero was fond of repeating cer tain phrases, and these I learned to reduce to a line, or even a fe w dots – thus proving what most people already know, that politicians essentially say the same thing over and over again. He dictated to me from his bath and his couch, from inside swaying carriages and on countr y walks. He never ran shor t of words and I never ran shor t of

symbols to catch and hold them for ever as they fle w through the air. We were made for one another.

But to return to Sicily. Do not be alarmed: I shall not describe our work in any detail. Like so much of politics, it was drear y even while it was happening, without revisiting it sixty-odd years later. What was memorable, and significant, was the journey home. Cicero purposely delayed this by a month, from March to April, to ensure he passed through Puteoli during the senate recess, at exactly the moment when all the smart political set would be on the Bay of Naples, enjoying the mineral baths. I was ordered to hire the finest twelve-oared rowing boat I could find, so that he could enter the harbour in style, wearing for the first time the purple-edged toga of a senator of the Roman republic.

For Cicero had convinced himself that he had been such a great success in Sicily, he must be the centre of all attention back in Rome. In a hundred stifling market squares, in the shade of a thousand dusty, wasp-infested Sicilian plane trees, he had dispensed Rome’s justice, impartially and with dignity. He had purchased a record amount of grain to feed the electors back in the capital, and had dispatched it at a record cheap price. His speeches at government ceremonies had been masterpieces of tact. He had even feigned interest in the conversation of the locals. He knew he had done well, and in a stream of official reports to the senate he boasted of his achievements. I must confess that occasionally I toned these down before I gave them to the official messenger, and

tried to hint to him that perhaps Sicily was not entirely the centre of the world. He took no notice.

I can see him now, standing in the prow, straining his eyes at Puteoli’s quayside, as we returned to Italy. What was he expecting? I wonder. A band to pipe him ashore? A consular deputation to present him with a laurel wreath? There was a crowd, all right, but it was not for him. Hortensius, who already had his eye on the consulship, was holding a banquet on several brightly coloured pleasure-craft moored nearby, and guests were waiting to be ferried out to the party. Cicero stepped ashore – ignored. He looked about him, puzzled, and at that moment a few of the revellers, noticing his freshly gleaming senatorial rig, came hurr ying towards him. He squared his shoulders in pleasurable anticipation.

‘Senator,’ called one, ‘what’s the news from Rome?’ Cicero somehow managed to maintain his smile. ‘I have not come from Rome, my good fellow. I am returning from my province.’

A red-haired man, no doubt already drunk, said, ‘Ooooh! My good fellow ! He’s re tur ning from his province . . . ’

There was a snort of laughter, barely suppressed.

‘What is so funny about that?’ interrupted a third, eager to smooth things over. ‘Don’t you know? He has been in Africa.’

Cicero’s smile was now heroic. ‘Sicily, actually.’

There may have been more in this vein. I cannot remember. People began drifting away once they realised

there was no city gossip to be had, and ver y soon Hortensius came along and ushered his remaining guests towards their boats. Cicero he nodded to, civilly enough, but pointedly did not invite to join him. We were left alone.

A trivial incident, you might think, and yet Cicero himself used to say that this was the instant at which his ambition hardened within him to rock. He had been humiliated – humiliated by his own vanity – and given brutal evidence of his smallness in the world. He stood there for a long time, watching Hortensius and his friends partying across the water, listening to the merr y flutes, and when he turned away, he had changed. I do not exaggerate. I saw it in his eyes. Very well, his expression seemed to say, you fools can frolic; I shall work.

‘This experience, gentlemen, I am inclined to think was more valuable to me than if I had been hailed with salvoes of applause. I ceased thenceforth from considering what the world was likely to hear about me: from that day I took care that I should be seen personally ever y day. I lived in the public eye. I frequented the forum. Neither my doorkeeper nor sleep prevented anyone from getting in to see me. Not even when I had nothing to do did I do nothing, and consequently absolute leisure was a thing I never knew.’

I came across that passage in one of his speeches not long ago and I can vouch for the truth of it. He walked away from the harbour like a man in a dream, up through Puteoli and out on to the main highway

without once looking back. I struggled along behind him carr ying as much luggage as I could manage. To begin with, his steps were slow and thoughtful, but gradually they picked up speed, until at last he was striding so rapidly in the direction of Rome I had difficulty keeping up.

And with this both ends my first roll of paper, and begins the real stor y of Marcus Tullius Cicero.

TIIhe day which was to prove the turning point began like any other, an hour before dawn, with Cicero, as always, the first in the household to rise. I lay for a little while in the darkness and listened to the thump of the floorboards above my head as he went through the exercises he had learned on Rhodes – a visit now six years in the past – then I rolled off my straw mattress and rinsed my face. It was the first day of November; cold.

Cicero had a modest two-storey dwelling on the ridge of the Esquiline Hill, hemmed in by a temple on one side and a block of flats on the other, although if you could be bothered to scramble up on to the roof you would be rewarded with a decent vie w across the smoky valley to the great temples on Capitol Hill about half a mile to the west. It was actually his father’s place, but the old ge nt lem an was i n poor health nowa days and seldom left the countr y, so Cicero had it to himself, alo ng with Te rentia and their fiv eyear-old daughter, Tullia, and a dozen slaves: me, the tw o secretar ie s working under m e, Sositheus and Laurea, the steward, Eros, Terentia’s business manager,

Philotimus, two maids, a nurse, a cook, a valet and a doorkeeper. There was also an old blind philosopher so me whe re , Di odotus the Stoic, w ho occasiona lly groped his way out of his room to join Cicero for di nner when his master needed an intellectual workout. So: fifteen of us in the household in all. Te rentia complained endlessly about the cramped conditions, but Cicero would not move, for at this time he was still ver y much in his man-of-the-people phase, and the house sat well with the image.

The first thing I did that morning, as I did ever y morning, was to slip over my left wrist a loop of cord, to which was attached a small notebook of my own design. This consisted of not the usual one or two but four double-sided sheets of wax, each in a beechwood frame, ver y thin and so hinged that I could fold them all up and snap them shut. In this way I could take many more notes in a single session of dictation than the average secretar y; but even so, such was Cicero’s daily torrent of words, I always made sure to put spares in my pockets. Then I pulled back the curtain of my tiny room and walked across the courtyard into the tablinum, lighting the lamps and checking all was ready. The only piece of furniture was a sideboard, on which stood a bowl of chickpeas. (Cicero’s name derived from cicer, meaning chickpea, and believing that an unusual name was an advantage in politics, he always took pains to draw attention to it.) Once I was satisfied, I passed through the atrium into the entrance hall, where the doorman was already waiting with his hand on the big

metal lock. I checked the light through the narrow window, and when I judged it pale enough, gave a nod to the doorman, who slid back the bolts.

Outside in the chilly street, the usual crowd of the miserable and the desperate was already waiting, and I made a note of each man as he crossed the threshold. Most I recognised; those I did not, I asked for their names; the familiar no-hopers, I turned away. But the standing instruction was: ‘If he has a vote, let him in’, so the tablinum was soon well filled with anxious clients, each seeking a piece of the senator’s time. I lingered by the entrance until I reckoned the queue had all filed in and was just stepping back when a figure with the dusty clothes, straggling hair and uncut beard of a man in mourning loomed in the doorway. He gave me a fright, I do not mind admitting.

‘Tiro!’ he said. ‘ Thank the gods!’ And he sank against the door jamb, exhausted, peering out at me with pale, dead eyes. I guess he must have been about fifty. At first I could not place him, but it is one of the jobs of a political secretar y to put names to faces, and gradually, despite his condition, a picture began to assemble in my mind: a large house overlooking the sea, an ornamental garden, a collection of bronze statues, a town somewhere in Sicily, in the north – Thermae, that was it.

‘Sthenius of Thermae,’ I said, and held out my hand. ‘Welcome.’

It was not my place to comment on his appearance, nor to ask what he was doing hundreds of miles from

home and in such obvious distress. I left him in the tablinum and went through to Cicero’s study. The senator, who was due in court that morning to defend a youth charged with parricide, and who would also be expected to attend the afternoon session of the senate, was squeezing a small leather ball to strengthen his fingers, while being robed in his toga by his valet. He was listening to one letter being read out by young Sositheus, and at the same time dictating a message to Laurea, to whom I had taught the rudiments of my shorthand system. As I entered, he threw the ball at me – I caught it without thinking – and gestured for the list of callers. He read it greedily, as he always did. What had he caught overnight? Some prominent citizen from a useful tribe? A Sabatini, perhaps? A Pomptini? Or a businessman rich enough to vote among the first centuries in the consular elections? But today it was only the usual small fr y and his face gradually fell until he reached the final name.

‘Sthenius?’ He interrupted his dictation. ‘He’s that Sicilian, is he not? The rich one with the bronzes? We had better find out what he wants.’

‘Sicilians don’t have a vote,’ I pointed out.

‘Pro bono,’ he said, with a straight face. ‘Besides, he does have bronzes. I shall see him first.’

So I fetched in Sthenius, who was given the usual treatment – the trademark smile, the manly doublegrip handshake, the long and sincere stare into the eyes – then shown to a seat and asked what had brought him to Rome. I had started remembering more about

Sthenius. We had stayed with him twice in Thermae, when Cicero heard cases in the town. Back then he had been one of the leading citizens of the province, but now all his vigour and confidence had gone. He needed help, he announced. He was facing ruin. His life was in terrible danger. He had been robbed.

‘Really?’ said Cicero. He was half glancing at a document on his desk, not paying too much attention, for a busy advocate hears many hard-luck stories. ‘ You have my sympathy. Robbed by whom?’

‘By the governor of Sicily, Gaius Verres.’

The senator looked up sharply.

There was no stopping Sthenius after that. As his stor y poured out, Cicero caught my eye and performed a little mime of note-taking – he wanted a record of this – and when Sthenius eventually paused to draw breath, he gently interrupted and asked him to go back a little, to the day, almost three months earlier, when he had first received the letter from Verres. ‘ What was your reaction?’

‘I worried a little. He already had a . . . reputation. People call him – his name meaning boar – people call him the Boar with Blood on his Snout. But I could hardly refuse.’

‘You still have this letter?’

‘Yes.’

‘And in it did Verres specifically mention your art collection?’

‘Oh yes. He said he had often heard about it and wanted to see it.’

‘And how soon after that did he come to stay?’

‘Very soon. A week at most.’

‘Was he alone?’

‘No, he had his lictors with him. I had to find room for them as well. Bodyguards are always rough types, but these were the worst set of thugs I ever saw. The chief of them, Sextius, is the official executioner for the whole of Sicily. He demands bribes from his victims by threatening to botch the job – you know, mangle them – if they do not pay up beforehand.’ Sthenius swallowed and started breathing hard. We waited.

‘Take your time,’ said Cicero.

‘I thought Verres might like to bathe after his journey, and then we could dine – but no, he said he wanted to see my collection straightaway.’

‘You had some ver y fine pieces, I remember.’

‘It was my life, Senator, I cannot put it plainer. Thirty years of travelling and haggling. Corinthian and Delian bronzes, pictures, silver – nothing I did not handle and choose myself. I had Myron’s The Discus Thrower and The Spear Bearer by Polycleitus. Some silver cups by Mentor. Verres was complimentar y. He said it deser ved a wider audience. He said it was good enough for public display. I paid no attention till we were having dinner on the terrace and I heard a noise from the inner courtyard. My steward told me a wagon drawn by oxen had arrived and Verres’s lictors were loading it with ever ything.’

Sthenius was silent again, and I could readily imagine the shame of it for such a proud man: his wife wailing,

the household traumatised, the dusty outlines where the statues had once stood. The only sound in the study was the tap of my stylus on wax.

Cicero said: ‘ You did not complain?’

‘Who to? The governor?’ Sthenius laughed. ‘No, Senator. I was alive, wasn’t I? If he had just left it at that, I would have swallowed my losses, and you would never have heard a squeak from me. But collecting can be a sickness, and I tell you what: your Governor Verres has it badly. You remember those statues in the town square?’

‘Indeed I do. Three ver y fine bronzes. But you are surely not telling me he stole those as well?’

‘He tried. This was on his third day under my roof. He asked me whose they were. I told him they were the property of the town, and had been for centuries. You know they are four hundred years old? He said he would like permission to remove them to his residence in Syracuse, also as a loan, and asked me to approach the council. By then I knew what kind of a man he was, so I said I could not, in all honour, oblige him. He left that night. A fe w days after that , I rec ei ved a summons for trial on the fifth day of October, on a charge of forgery.’

‘Who brought the charge?’

‘An enemy of mine named Agathinus. He is a client of Verres. My first thought was to face him down. I have nothing to fear as far as my honesty goes. I have never forged a document in my life. But then I heard the judge was to be Verres himself, and that he had

already fixed on the punishment. I was to be whipped in front of the whole town for my insolence.’

‘And so you fled?’

‘That same night, I took a boat along the coast to Messana.’

Cicero rested his chin in his hand and contemplated Sthenius. I recognised that gesture. He was weighing the witness up. ‘ You say the hearing was on the fifth of last month. Have you heard what happened?’

‘That is why I am here. I was convicted in my absence, sentenced to be flogged – and fined five thousand. But there is worse than that. At the hearing, Verres claimed fresh evidence had been produced against me, this time of spying for the rebels in Spain. There is to be a new trial in Syracuse on the first day of December.’

‘But spying is a capital offence.’

‘Senator – believe me – he plans to have me crucified. He boasts of it openly. I would not be the first, either. I need help. Please. Will you help me?’

I thought he might be about to sink to his knees and start kissing the senator’s feet, and so, I suspect, did Cicero, for he quickly got up from his chair and started pacing about the room. ‘It seems to me there are two aspects to this case, Sthenius. One, the theft of your property – and there, frankly, I cannot see what is to be done. Why do you think men such as Verres desire to be governors in the first place? Because they know they can take what they want, within reason. The second aspect, the manipulation of the legal process –that is more promising.

‘I know several men with great legal expertise who live in Sicily – one, indeed, in Syracuse. I shall write to him today and urge him, as a particular favour to me, to accept your case. I shall even give him my opinion as to what he should do. He should apply to the court to have the forthcoming prosecution declared invalid, on the grounds that you are not present to answer. If that fails, and Verres goes ahead, your advocate should come to Rome and argue that the conviction is unsound.’

But the Sicilian was shaking his head. ‘If it was just a lawyer in Syracuse I needed, Senator, I would not have come all the way to Rome.’

I could see Cicero did not like where this was leading. Such a case could tie up his practice for days, and Sicilians, as I had reminded him, did not have votes. Pro bono indeed!

‘Listen,’ he said reassuringly, ‘your case is strong. Verres is obviously corrupt. He abuses hospitality. He steals. He brings false charges. He plots judicial murder. His position is indefensible. It can easily be handled by an advocate in Syracuse – really, I promise you. Now, if you will excuse me, I have many clients to see, and I am due in court in less than an hour.’

He nodded to me and I stepped for ward, putting a hand on Sthenius’s arm to guide him out. The Sicilian shook it off. ‘But I need you,’ he persisted.

‘Why?’

‘Because my only hope of justice lies here, not in Sicily, where Verres controls the courts. And ever yone

here tells me Marcus Cicero is the second-best lawyer in Rome.’

‘Do they indeed?’ Cicero’s tone took on an edge of sarcasm: he hated that epithet. ‘ Well then, why settle for second best? Why not go straight to Hortensius?’

‘I thought of that,’ said his visitor artlessly, ‘but he turned me down. He is representing Verres.’

Ishowed the Sicilian out and returned to find Cicero alone in his study, tilted back in his chair, staring at the wall, tossing the leather ball from one hand to the other. Legal textbooks cluttered his desk. Precedents in Pleading by Hostilius was one which he had open; Manilius’s Conditions of Sale was another.

‘Do you remember that red-haired drunk on the quayside at Puteoli, the day we came back from Sicily? “Ooooh! My good fellow ! He’s returning from his province . . .”’

I nodded.

‘That was Verres.’ The ball went back and forth, back and forth. ‘ The fellow gives corruption a bad name. ’

‘I am surprised at Hortensius for getting involved with him.’

‘Are you? I’m not.’ He stopped tossing the ball and contemplated it on his outstret ched p alm. ‘ The Dancing Master and the Boar . . .’ He brooded for a while. ‘A man in my position would have to be mad to tangle with Hortensius and Verres combined, and

all for the sake of some Sicilian who is not even a Roman citizen.’

‘True.’

‘True,’ he repeated, although there was an odd hesitancy in the way he said it which sometimes makes me wonder if he had not just then glimpsed the whole thing – the whole extraordinar y set of possibilities and consequences, laid out like a mosaic in his mind. But if he had, I never knew, for at that moment his daughter Tullia ran in, still wearing her nightdress, with some childish drawing to show him, and suddenly his attention switched entirely on to her and he scooped her up and settled her on his knee. ‘Did you do this? Did you really do this all by yourself . . . ?’

I left him to it and slipped away, back into the tablinum, to announce that we were running late and that the senator was about to leave for court. Sthenius was still moping around, and asked me when he could expect an answer, to which I could only reply that he would have to fall in with the rest. Soon after that Cicero himself appeared, hand in hand with Tullia, nodding good morning to ever yone, greeting each by name (‘ The first rule in politics, Tiro: never forget a face’). He was beautifully turned out, as always, his hair pomaded and slicked back, his skin scented, his toga freshly laundered; his red leather shoes spotless and shiny; his face bronzed by years of pleading in the open air; groomed, lean, fit: he glowed. They followed him into the vestibule, where he hoisted the beaming little girl into the air, showed her off to the assembled

company, then turned her face to his and gave her a resounding kiss on the lips. There was a drawn-out ‘Ahh!’ and some isolated applause. It was not wholly put on for show – he would have done it even if no one had been present, for he loved his darling Tulliola more than he ever loved anyone in his entire life – but he knew the Roman electorate were a sentimental lot, and that if word of his paternal devotion got around, it would do him no harm.

And so we stepped out into the bright promise of that November morning, into the gathering noise of the city – Cicero striding ahead, with me beside him, notebook at the ready; Sositheus and Laurea tucked in b ehind, carr yi ng the document cas es wit h the evidence he needed for his appearance in cour t; and, on either side of us, tr ying to catch the senator’s attention, yet proud merely to be in his aura, two dozen assor ted pe ti tio ners and hange rs-on, includi ng Sthenius – down the hill from the leafy, respectable heights of the Esquiline and into the stink and smoke and racket of Subura. Here the height of the tenements shut out the sunlight and the packed crowds squeezed our phalanx of suppor ters into a broken thread that still somehow determinedly trailed along after us. Cicero was a well-known figure here, a hero to the shopkeepers and merchants whose interests he had represented, and who had watched him walking past for years. Without once breaking his rapid step, his sharp blue eyes registered ever y bowed head, ever y wave of greeting, and it was rare for me to need to

whisper a name in his ear, for he kne w his voters far better than I.

I do not know how it is these days, but at that time there were six or seven law courts in almost permanent session, each set up in a different part of the forum, so that at the hour when they all opened one could barely move for advocates and legal officers hurr ying about. To make it worse, the praetor of each court would always arrive from his house preceded by half a dozen lictors to clear his path, and as luck would have it, our little entourage debouched into the forum at exactly the moment that Hortensius – at this time a praetor himself – went parading by towards the senate house. We were all held back by his guards to let the great man pass, and to this day I do not think it was his intention to cut Cicero dead, for he was a man of refined, almost effeminate manners: he simply did not see him. But the consequence was that the so-called second-best advocate in Rome, his cordial greeting dead on his lips, was left staring at the retreating back of the so-called best with such an intensity of loathing I was surprised Hortensius did not start rubbing at the skin between his shoulder blades.

Our business that morning was in the central criminal court, convened outside the Basilica Aemilia, where the fifteen-year-old Caius Popillius Laenas was on trial accused of stabbing his father to death through the eye with a metal stylus. I could already see a big crowd waiting around the tribunal. Cicero was due to make the closing speech for the defence. That was attraction

enough. But if he failed to convince the jury, Popillius, as a convicted parricide, would be stripped naked, flayed till he bled, then sewn up in a sack together with a dog, a cock and a viper and thrown into the River Tiber. There was a whiff of bloodlust in the air, and as the onlookers parted to let us through, I caught a glimpse of Popillius himself, a notoriously violent youth, whose eyebrows merged to form a continuous thick black line. He was seated next to his uncle on the bench reserved for the defence, scowling defiantly, spitting at anyone who came too close. ‘We really must secure an acquittal,’ observed Cicero, ‘if only to spare the dog, the cock and the viper the ordeal of being sewn up in a sack with Popillius.’ He always maintained that it was no business of the advocate to worry whether his client was guilty or not: that was for the court. He undertook only to do his best, and in return the Popillii Laeni, who could boast four consuls in their family tree, would be obliged to support him whenever he ran for office.

Sositheus and Laurea set down the boxes of evidence, and I was just bending to unfasten the nearest when Cicero told me to leave it. ‘Save yourself the trouble,’ he said, tapping the side of his head. ‘I have the speech up here well enough.’ He bowed politely to his client – ‘Good day, Popillius: we shall soon have this settled, I trust’ – then continued to me, in a quieter voice: ‘I have a more important task for you. Give me your notebook. I want you to go to the senate house, find the chief clerk, and see if there is a chance of having this put on the order paper this afternoon.’ He was

writing rapidly. ‘Say nothing to our Sicilian friend just yet. There is great danger. We must take this carefully, one step at a time.’

It was not until I had left the tribunal and was halfway across the forum to the senate house that I risked taking a look at what he had written: That in the opinion of this house the prosecution of persons in their absence on capital charges should be prohibited in the provinces. I felt a tightening in my chest, for I saw at once what it meant. Cleverly, tentatively, obliquely, Cicero was preparing at last to challenge his great rival. I was carr ying a declaration of war.

Gellius Publicola was the presiding consul for November. He was a blunt, delightfully stupid militar y commander of the old school. It was said, or at any rate it was said by Cicero, that when Gellius had passed through Athens with his army twenty years before, he had offered to mediate between the warring schools of philosophy: he would convene a conference at which they could thrash out the meaning of life once and for all, thus sparing themselves further pointless argument. I knew Gellius’s secretar y fairly well, and as the afternoon’s agenda was unusually light, with nothing scheduled apart from a report on the militar y situation, he agreed to add Cicero’s motion to the order paper. ‘But you might warn your master,’ he said, ‘that the consul has heard his little joke about the philosophers, and he does not much like it.’

By the time I returned to the criminal court, Cicero was already well launched on his closing speech for the defence. It was not one of those which he after wards chose to preser ve, so unfortunately I do not have the text. All I can remember is that he won the case by the clever expedient of promising that young Popillius, if acquitted, would devote the rest of his life to militar y ser vice – a pledge which took the prosecution, the jur y, and indeed his client entirely by surprise. But it did the trick, and the moment the verdict was in, without pausing to waste another moment on the ghastly Popillius, or even to snatch a mouthful of food, he set off immediately westwards towards the senate house, still trailed by his original honour-guard of admirers, their number swelled by the spreading rumour that the great advocate had another speech planned.

Cicero used to say that it was not in the senate chamber that the real business of the republic was done, but outside, in the open-air lobby known as the senaculum, where the senators were obliged to wait until they constituted a quorum. This daily massing of white-robed figures, which might last for an hour or more, was one of the great sights of the city, and while Cicero plunged in among them, Sthenius and I joined the crowd of gawpers on the other side of the forum. (The Sicilian, poor fellow, still had no idea what was happening.)

It is in the nature of things that not all politicians can achieve greatness. Of the six hundred men who then constituted the senate, only eight could be elected

praetor – to preside over the courts – in any one year, and only two of these could go on to achieve the supreme imperium of the consulship. In other words, more than half of those milling around the senaculum were doomed never to hold elected office at all. They were what the aristocrats sneeringly called the pedarii, the men who voted with their feet, shuffling dutifully to one side of the chamber or the other whenever a division was called. And yet, in their way, these citizens were the backbone of the republic: bankers, businessmen and landowners from all over Italy; wealthy, cautious and patriotic; suspicious of the arrogance and show of the aristocrats. Like Cicero, they were often ‘new men’, the first in their families to win election to the senate. These were his people, and obser ving him threading his way among them that afternoon was like watching a master-craftsman in his studio, a sculptor with his stone – here a hand resting lightly on an elbow, there a heavy arm clapped across a pair of meaty shoulders; with this man a coarse joke, with that a solemn word of condolence, his own hands crossed and pressed to his breast in sympathy; detained by a bore, he would seem to have all the hours of the day to listen to his drear y stor y, but then you would see his hand flicker out and catch some passer-by, and he would spin as gracefully as a dancer, with the tenderest backward glance of apology and regret, to work on someone else. Occasionally he would gesture in our direction, and a senator would stare at us, and perhaps shake his head in disbelief, or nod slowly to promise his support.

‘What is he saying about me?’ asked Sthenius. ‘ What is he going to do?’

I made no answer, for I did not know myself. By now it was clear that Hortensius had realised something was going on, but was unsure exactly what. The order of business had been posted in its usual place beside the door of the senate house. I saw Hortensius stop to read it – the prosecution of persons in their absence on capital charges should be prohibited in the provinces – and turn away, mystified. Gellius Publicola was sitting inthe door way on his car ved ivor y chair, surrounded by his attendants, waiting until the en trails had been inspected and the auguries declared favourable before summoning the senators inside. Hortensius approached him, palms spread wide in enquir y. Gellius shr ugged and pointed irritably at Ci cer o. Hor t ensius swung r ound to discove r hi s ambi tious rival surrounded by a conspiratorial circle of senators. He frowned, and went over to join his own aristocratic friends: the three Metellus brothers –Quintus, Lucius and Marcus – and the two elderly ex-consuls who really ran the empire, Quintus Catulus (whose sister was married to Hor tensius), and the double-triumphator Publius Ser vilius Vatia Isauricus. Merely writing their names after all these years raises the hairs on my neck, for these were such men, stern and unyielding and steeped in the old republican values, as no longer exist. Hortensius must have told them about the motion, because slowly all five turned to look at Cicero. Immediately thereafter a trumpet sounded

to signal the start of the session and the senators began to file in.

The old senate house was a cool, gloomy, cavernous temple of government, split by a wide central aisle of black and white tile. Facing across it on either side were long rows of wooden benches, six deep, on which the senators sat, with a dais at the far end for the chairs of the consuls. The light on that November afternoon was pale and bluish, dropping in shafts from the unglazed windows just beneath the raftered roof. Pigeons cooed on the sills and flapped across the chamber, sending small feathers and even occasionally hot squirts of excrement down on to the senators below. Some held that it was lucky to be shat on while speaking, others that it was an ill omen, a few that it depended on the colour of the deposit. The superstitions were as numerous as their interpretations. Cicero took no notice of them, just as he took no notice of the arrangement of sheep’s guts, or whether a peal of thunder was on the left or the right, or the par ticular flight-path of a flock of birds – idiocy all of it, as far as he was concerned, even though he later campaigned enthusiastically for election to the College of Augurs.

By ancient tradition, then still obser ved, the doors of the senate house remained open so that the people could hear the debates. The crowd, Sthenius and I among them, surged across the forum to the threshold of the chamber, where we were held back by a simple rope. Gellius was already speaking, relating the dispatches of the army commanders in the field. On

all three fronts, the news was good. In southern Italy, the vastly rich Marcus Crassus – he who once boasted that no man could call himself wealthy until he could keep a legion of five thousand solely out of his income – was putting down Spartacus’s slave revolt with great severity. In Spain, Pompey the Great, after six years’ fighting, was mopping up the last of the rebel armies. In Asia Minor, Lucius Lucullus was enjoying a glorious run of victories over King Mithradates. Once their reports had been read, supporters of each man rose in turn to praise his patron’s achievements and subtly denigrate those of his rivals. I knew the politics of this from Cicero and passed them on to Sthenius in a superior whisper: ‘Crassus hates Pompey and is determined to defeat Spartacus before Pompey can return with his legions from Spain to take all the credit. Pompey hates Crassus and wants the glor y of finishing off Spartacus so that he can rob him of a triumph. Crassus and Pompey both hate Lucullus because he has the most glamorous command.’

‘And whom does Lucullus hate?’ ‘Pompey and Crassus, of course, for intriguing against him.’

I felt as pleased as a child who has just successfully recited his lesson, for it was all just a game then, and I had no idea that we would ever get drawn in. The debate came to a desultor y halt, without the need for a vote, and the senators began talking among themselves. Gellius, who must have been well into his sixties, held the order paper up close to his face and squinted