Mozart’s

Three Symphonies

29-31 January 2026

Mozart’s Last Three Symphonies

Kindly supported by Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher.

Thursday 29 January, 7.30pm Usher Hall, Edinburgh

Friday 30 January, 7.30pm City Halls, Glasgow

Saturday 31 January, 7.30pm Aberdeen Music Hall

MOZART Symphony No.39

MOZART Symphony No.40

Interval of 20 minutes

MOZART Symphony No.41

Maxim Emelyanychev conductor

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB +44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

Maxim Emelyanychev

© Andrej Grilc

THANK YOU

Principal Conductor's Circle

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Geoff and Mary Ball

Bill and Celia Carman

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Sub-Principal Flute Marta Gómez

Judith and David Halkerston

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Sub-Principal Bassoon Alison Green

George Rubienski

Principal Horn Kenneth Henderson

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Funding Partners

SCO Donors

Diamond

The Cockaigne Fund

Malcolm and Avril Gourlay

John and Jane Griffiths

James and Felicity Ivory

George Ritchie

Tom and Natalie Usher

Platinum

E.C. Benton

Michael and Simone Bird

Silvia and Andrew Brown

David Caldwell in memory of Ann

Dr Peter Williamson and Ms Margaret Duffy

David and Elizabeth Hudson

Helen B Jackson

Dr and Mrs Peter Jackson

Dr Daniel Lamont

Graham and Elma Leisk

Professor and Mrs Ludlam

Chris and Gill Masters

Duncan and Una McGhie

Anne-Marie McQueen

James F Muirhead

Robin and Catherine Parbrook

Patrick and Susan Prenter

Mr and Mrs J Reid

The Walter and Janet Reid Charitable Trust

Martin and Mairi Ritchie

Hilary E Ross

Elaine Ross

Sir Muir and Lady Russell

Jill and Brian Sandford

Michael and Elizabeth Sudlow

Robert and Elizabeth Turcan

Alan and Sue Warner

Anny and Bobby White

Robert Mackay and Philip Whitley

Finlay and Lynn Williamson

Ruth Woodburn

Gold

Peter Armit

Adam Gaines and Joanna Baker

John and Maggie Bolton

Elizabeth Brittin

Kate Calder

James Wastle and Glenn Craig

Jo and Christine Danbolt

James and Caroline Denison-Pender

Andrew and Kirsty Desson

David and Sheila Ferrier

Chris and Claire Fletcher

James Friend

Iain Gow

Margaret Green

Christopher and Kathleen Haddow

Catherine Johnstone

Julie and Julian Keanie

Gordon Kirk

Janey and Barrie Lambie

Mike and Karen Mair

Roy and Svend McEwan-Brown

John and Liz Murphy

Tom Pate

Maggie Peatfield

Sarah and Spiro Phanos

Charles Platt and Jennifer Bidwell

Alison and Stephen Rawles

Andrew Robinson

Olivia Robinson

Anne McAlister and Philip Sawyer

Irene Smith

Dr Jonathan Smithers

Ian S Swanson

Ian and Janet Szymanski

John-Paul and Joanna Temperley

Douglas and Sandra Tweddl

Bill Welsh

Catherine Wilson

Neil and Philippa Woodcock

Silver

Roy Alexander

Fiona and Neil Ballantyne

The Batsleer Family

Jack Bogle

Jane Borland

Alan Borthwick

Dinah Bourne

Michael and Jane Boyle

Mary Brady

John Brownlie

Laura Buist

Robert Burns

Sheila Colvin

Lorn and Camilla Cowie

Adam and Lesley Cumming

Dr Wilma Dickson

Seona Reid and Cordelia Ditton

Sylvia Dow

Colin Duncan in memory of Norma Moore

Raymond Ellis

Dr and Mrs Alan Falconer

Sheila Ferguson

Dr William Irvine Fortescue

Dr David Grant

Anne Grindley

Andrew Hadden

J Martin Haldane

Ronnie and Ann Hanna

Roderick Hart

Norman Hazelton

Ron and Evelynne Hill

Philip Holman

Clephane Hume

Tim and Anna Ingold

David and Pamela Jenkins

Margaret Mortimer and Ken Jobling

Ross D. Johnstone

Professor Christopher and Mrs Alison Kelnar

Dr Ian Laing

Geoff Lewis

Dorothy A Lunt

Vincent Macaulay

James McClure in memory of Robert Duncan

Ben McCorkell

Lucy McCorkell

Gavin McCrone

Michael McGarvie

Brian Miller

Alistair Montgomerie

Andrew Murchison

Pamela Andrews and Alan Norton

Gilly Ogilvy-Wedderburn

Mairi & Ken Paterson

John Peutherer in memory of Audrey Peutherer

James S Potter

Timothy Barnes and Janet Sidaway

Catherine Steel

John and Angela Swales

Takashi and Mikako Taji

C S Weir

Susannah Johnston and Jamie Weir

David and Lucy Wren

We are indebted to everyone acknowledged here who gives philanthropic gifts to the SCO of £300 or greater each year, as well as those who prefer to remain anonymous.

We are also incredibly thankful to the many individuals not listed who are kind enough to support the Orchestra financially on a regular or ad hoc basis. Every single donation makes a difference.

Become a regular donor, from as little as £5 a month, by contacting Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk.

“…an orchestral sound that seemed to gleam from within.”

THE SCOTSMAN

HM The King Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

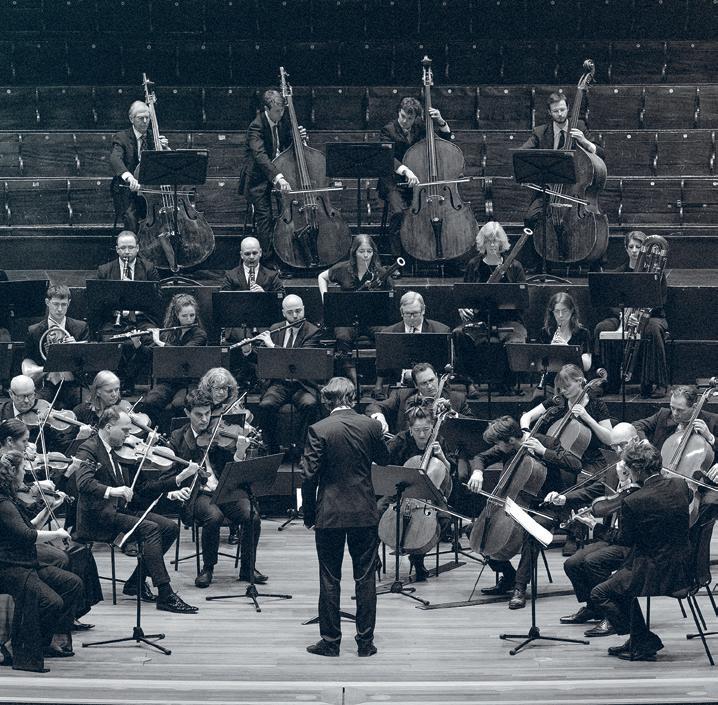

© Chris Christodoulou

Our Musicians

Your Orchestra Tonight

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Stephanie Gonley

Afonso Fesch

Agata Daraškaitė

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Aisling O’Dea

Fiona Alexander

Sarah Bevan Baker

Wen Wang

Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Hatty Haynes

Michelle Dierx

Rachel Smith

Tom Hankey

Kristin Deeken

Elvira van Groningen

Catherine James

Viola

Max Mandel

Francesca Gilbert

Brian Schiele

Steve King

Rebecca Wexler

Kathryn Jourdan

Cello

Philip Higham

George Ross

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Kim Vaughan

Bass

Jamie Kenny

Ben Havinden-Williams

Yehor Podkolzin

Flute

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Clara Schweinberger

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Cristina Mateo Sáez

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

William Stafford

Sub-Principal Clarinet

Horn

Kenneth Henderson

Daniel Lőffler

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

What You Are About To Hear

MOZART (1756-1791)

Symphony No.39 in E-flat major, K.543 (1788)

Adagio – Allegro

Andante con moto

Menuetto (Allegretto)

Allegro

MOZART (1756-1791)

Symphony No.40 in G minor, K.550 (1788, revised 1788-91)

Molto allegro

Andante

Menuetto (Allegretto)

Allegro assai

MOZART (1756-1791)

Symphony No.41 in C major, K.551 (1788)

Allegro vivace

Andante cantabile

Menuetto (Allegretto)

Molto allegro

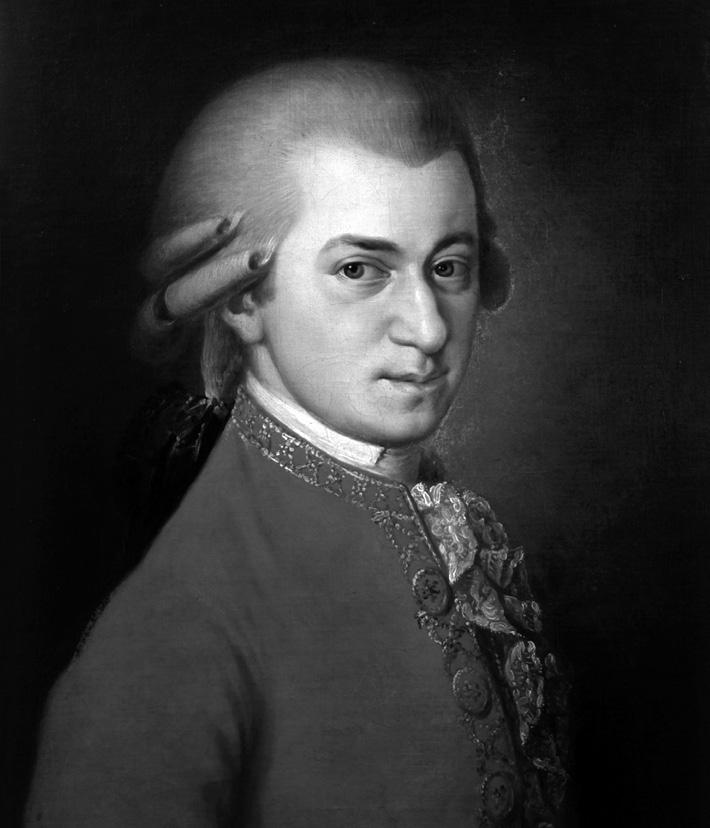

Amadeus – whether Peter Schaffer’s 1979 play or Miloš Forman’s 1984 movie adaptation – has got a lot to answer for. Yes, we’re probably all aware that the play/film’s speculation about the genius Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart being poisoned by his less talented rival Antonio Salieri is more dramatic invention than historical truth. Indeed, that kind of speculation goes right back at least to Alexander Pushkin, whose 1830 drama Mozart and Salieri – written just four decades after Mozart’s actual demise – suggested pretty much the same thing, and was turned into an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov in 1897 (Schaffer acknowledged Pushkin’s play as a direct inspiration for his own work).

But even if we might not take Amadeus’ (or Mozart and Salieri’s) plotline as the undisputed truth, it’s the way that those fictionalised accounts serve to mythologise Mozart, to foreground his apparently Godgiven genius and the tragedy of his early death, that has cast quite a deep shadow over broad perceptions of his life and music.

Just take the composer’s final three symphonies – Nos 39, 40 and 41 – which we’ll hear in tonight’s concert (and which, interestingly, don’t get a mention in either version of Amadeus). They’re pieces that raise significant questions. We know they weren’t commissioned, so why did Mozart even write them? Was the composer aware of his impending demise, and did he therefore intend them as his legacy, his musical offering to posterity? He wrote them pretty much concurrently across eight busy weeks in the summer of 1788: does that unusual way of working support the posterity hypothesis? Did Mozart even get to hear them before he died?

There’s long been an aura of mystery and almost spiritual profundity attached to

There’s long been an aura of mystery and almost spiritual profundity attached to Mozart’s final three symphonies.

Mozart’s final three symphonies. It’s summed up nicely by eminent music historian Alfred Einstein, who, in his 1945 book Mozart: His Character, His Work, asserted that the symphonies’ mystery ‘is perhaps symbolic of their position in the history of music and of human endeavour, representing no occasion, no immediate purpose, but an appeal to eternity’.

That’s certainly one way of looking at things. Another, perhaps, is to point out that in 1788, Mozart still had three years to live: with no indications of his untimely demise, would he himself really have considered these three works his final symphonies? They’re the last works he composed in that particular form, but he was still producing music at a rate of knots: between 1788 and his death in December 1791, he’d go on to compose several chamber and keyboard works; the three ‘Prussian’ string quartets; the operas

Così fan tutte, The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito; the Clarinet Concerto; the choral miniature Ave verum corpus; and of course the unfinished Requiem.

But claims about the final three symphonies don’t stop there. Many musicians – most prominently the eminent conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who died in 2016 – have felt that they form a stand-alone mini-cycle, even a single entity, conceived and intended to be experienced as a grand, overarching megapiece, with No.39 forming a kind of expansive overture to the drama of No.40 and the lavish celebration of No.41. It’s a perspective that this evening’s concert – alongside many performances by other orchestras across the world – seems to support, even tacitly. And there’s no denying that the three symphonies fill a conventional evening’s programme very well, providing a satisfying and diverse arc of music across their 12 combined movements.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Harnoncourt described them as an ‘instrumental oratorio’ with an inner dramatic unity, highlighting specific aspects of the music to support this view. Symphony No.39 has a long, slow introduction but no closing coda, for example, suggesting it might run straight into No.40, whereas No.41 has the longest, grandest finale of them all, perhaps indicating that that movement is intended as the summation of the entire trilogy.

It wouldn’t have been unprecedented to conceive a trilogy of symphonies in this way. Haydn had done something similar in 1761 in his trio of symphonies (Nos 6, 7 and 8) inspired by times of the day, ‘Le matin’, ‘Le midi’ and ‘Le soir’. But despite the pleasing, three-part, light-dark-light, major-minor-major arch-like form in Mozart’s final symphonies, he created no specific connections between their respective musics – certainly no recurring melodies or shared ideas – and even used a slightly different combination of instruments for each symphony’s orchestra. It’s hard to assert with confidence, then, that he really intended them to be experienced together as a 12-movement whole – which is not, of course, the same as saying we shouldn’t.

Perhaps the real mystery behind Mozart’s final three symphonies, though, is why we seem so intent on discovering a deeper, hidden meaning behind the works, and why we seem to want to tie that meaning to a mythologised version of Mozart the boy genius whose life was so mysteriously cut short. Perhaps what actually makes these symphonies special, rather than any mysterious speculation about their purpose or connections, is quite simply their music, which shows the composer not only at the height of his powers, but also straining against the bounds and very definition of

what a symphony could and should be, at least in late 18th-century Vienna.

Viennese audiences in Mozart’s time would have expected something concise, tuneful, immediate and fairly lightweight from a symphony. What Mozart increasingly offered them were symphonies that were longer, more ambitious, more dramatic, and more challenging for players and listeners alike. No wonder, perhaps, that by 1788, the city’s notoriously fickle cultural tastes that had once adored the mischievous but pioneering young musician were increasingly turning away from him. While they’d once lapped up anything he produced, their tastes had moved on. On top of that, after the Hapsburg monarchy declared war on the Ottoman Empire in February 1788, wealthy Viennese patrons found they had far less disposable income to fritter on such luxuries as concerts and commissions. Once the darling of Viennese society, Mozart was quickly reduced to begging friends for loans.

That said, the popular perception of a penniless Mozart struggling to make ends meet during the final years of his life isn’t quite right either. He was still receiving a relatively comfortable income. It’s just that he also managed to spend substantially more than he earned – and, of course, he was supporting his wife Constanze and their two young children. The family moved from central Vienna to the then suburb of Alsergrund in the summer of 1788, ostensibly to save money, though Mozart later admitted that he was paying the same rent away from the city centre, just for a larger property.

It's perhaps an unlikely context in which to create three pioneering works devoted solely to posterity, but one in which Mozart may nevertheless have felt compelled to continue

Perhaps the real mystery behind Mozart’s final three symphonies, though, is why we seem so intent on discovering a deeper, hidden meaning behind the works, and why we seem to want to tie that meaning to a mythologised version of Mozart the boy genius whose life was so mysteriously cut short.

his development of the symphonic form itself. The three symphonies that resulted are undeniably a leap forward from Mozart’s earlier symphonies – something we can only really appreciate by imagining ourselves as listeners at the end of the 18th century, rather than two decades into the 21st. Today, we might consider a symphony to be a glimpse into a composer’s innermost, profoundest thoughts, a deeply personal drama melding together abstract logic, confrontation and resolution. That, however, is essentially a model that would be laid down by Beethoven a few decades later. In Mozart’s time, conceiving and creating a symphony in this way was something of a radical departure – and goes some way, perhaps, towards explaining these three symphonies’ enduring power, fascination and relevance.

If the Symphony No.39 does function as the trilogy’s overture, then it’s a grand,

expansive introduction that has more than enough to capture the imagination in its own terms. Mozart builds up a sense of expectation in the slow introduction to his first movement, complete with majestic fanfares and drum strokes. And though the grand opening melts seamlessly into the movement’s faster main section, in a lilting three-beat time, the movement’s ceremonial grandeur remains until its sonorous conclusion.

An elegant violin melody kicks off the delicate second movement, though Mozart holds his woodwind back until the stormier central episode, where flutes and clarinets emphasise a distinctively rich, mellow sound world. His bumptious third movement sounds more like an Austrian Ländler dance than an elegant court minuet, and his finale plays endless witty games with its mischievous, dashing opening melody, which he puts

through all manner of transformations before it even makes one last, cheeky appearance amid the movement’s otherwise assertive conclusion.

From ceremonial grandeur to drama and tragedy: Mozart’s Symphony No.40 – one of only two by the composer in a darker minor key – occupies a very different emotional world from that of its predecessor. Indeed, its apparently intense emotions made the Symphony particularly popular with audiences and performers who came directly after Mozart, almost as an early herald of the stormy, individualistic, heroic Romantic style that Beethoven would usher in. It’s known, in fact, that Beethoven was a particular admirer of the Symphony No.40. He painstakingly copied out a section of it among the sketches for his own Fifth Symphony, suggesting that it may have exerted a direct influence on that later work.

After a moment or two of mood-setting accompaniment only – hardly usual practice in Mozart’s time – the first movement’s sighing main theme arrives quietly, but it’s quickly interrupted by fanfares and rushing scales. The movement’s second main theme, however, is far slinkier, even coquettish –though it sounds more resigned and listless when it returns in the darker minor towards the end of the movement.

The slower second movement feels far brighter and calmer, though he would no doubt have perplexed Viennese listeners by dragging the music through unfamiliar, strange and distant harmonies as the music develops. His third movement minuet would pose serious problems for dancers with its angry, forceful theme and its rhythmic tricksiness, though its central trio section pits choirs of stringed and woodwind instruments against each other in a brighter major key.

View of Vienna during the Baroque era, by Bernardo Bellotto

Mozart’s finale takes us back to the darker minor, but there’s a sense of determination and resistance to its explosive main theme. Again, Viennese listeners might have raised an eyebrow at the opening to his central development section, which sends the movement’s melody through all manner of angular, jagged figures and all but destroys any sense of a home key. The movement ends not with an uplifting slide into the brighter major, but doggedly in the Symphony’s original minor key.

Mozart’s final Symphony, No.41, is also his longest and grandest. Its ‘Jupiter’ nickname, however, is nothing to do with the composer: it was probably coined by London impresario Johann Peter Salomon or possibly the English music publisher Johann Baptist Cramer. And though it was essentially a marketing tag, there’s no denying that its reference to the mightiest of the Roman deities is an appropriate one in music of such grandeur and power.

It’s not known when the ‘Jupiter’ Symphony was first played, though the first documented performance was under Salomon in London in March 1798. The piece quickly gained an almost mythic status, however, as much for its scope and ambition as for the immediacy and vibrancy of its music. Robert Schumann wrote in 1835: ‘about many things in this world there is simply nothing to be said – for example, about Mozart’s C major Symphony with the fugue, much of Shakespeare, and some of Beethoven.’

It’s significant that Schumann should mention Beethoven. Mozart’s Symphony No.41 is probably the closest he came to his later colleague’s innovations, in terms of shifting the symphony as a musical form away from being a lightweight diversion and towards

an intense, compelling form of personal expression, a profound but also abstract musical utterance.

There’s a definite military character to the first movement’s assertive opening theme, a ceremonial exclamation from the full orchestra (no doubt intended to capture the audience’s attention), followed by a somewhat restrained response from the violins. The movement’s tripping second theme is songlike and heavily decorated, and Mozart even squeezes in – unusually – a third main theme, a coy and courtly folksong-like tune that seems to start in mid-flow. This is actually a self-quotation from Mozart’s concert aria ‘Un bacio di mano’ (‘A kiss on the hand’), which seems quite at odds with the military splendour of the movement’s opening.

The second movement begins serenely on veiled, muted strings, but the arrival of a far more troubled second theme, full of dissonances and syncopations, threatens to destabilise the movement entirely. After a good-natured, bouncing minuet, Mozart launches into the complexities and splendours of his lavish, expansive finale, whose opening theme begins with four distinctive, slowmoving notes. It’s a simple musical idea that many composers – including Mozart himself – had already used in their music, and it also featured as one of the exercises in Johann Joseph Fux’s counterpoint textbook Gradus ad Parnassum, known to all musicians in Mozart’s time. It’s almost as if Mozart is self-consciously drawing attention to what splendours he can achieve using such simple material, and the movement reaches its climax with a grand fugue that brings together all of its themes, and brings his final trilogy of symphonies to a deservedly triumphant conclusion.

© David Kettle

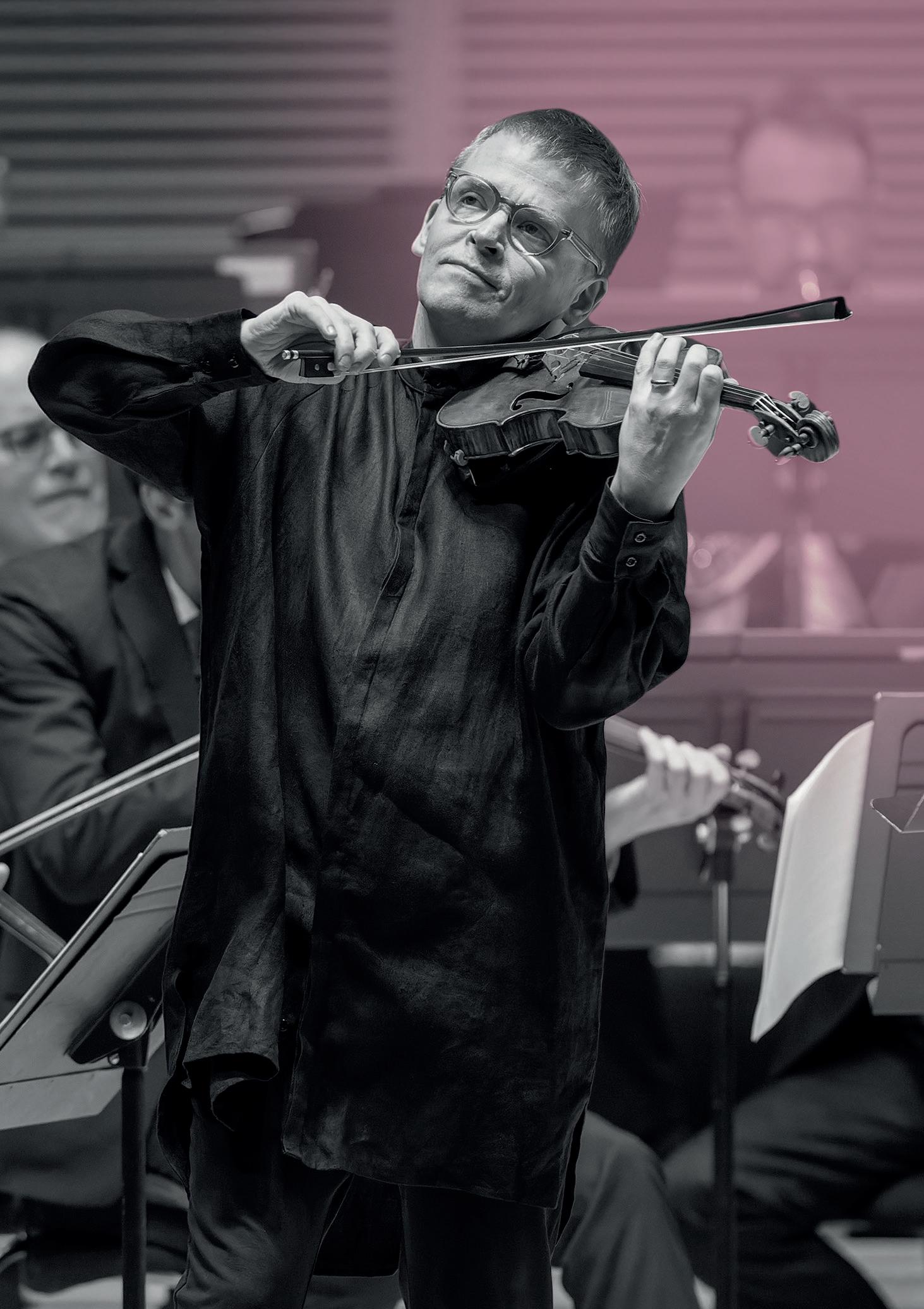

Conductor Maxim

Emelyanychev

Maxim Emelyanychev has been Principal Conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra since 2019. He is also Chief Conductor of period-instrument orchestra Il Pomo d’Oro, and became Principal Guest Conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra from the 2025/26 Season.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod, Emelyanychev made his conducting debut at the age of 12, and later joined the class of eminent conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky at the Moscow Conservatoire.

Emelyanychev was initially appointed as the SCO’s Principal Conductor until 2022, and the relationship was later extended until 2025 and then until 2028. He has conducted the SCO at the Edinburgh International Festival and the BBC Proms, as well as on several European tours and in concerts right across Scotland. He has also made three recordings with the SCO, of symphonies by Schubert and Mendelssohn (Linn Records).

Emelyanychev has also conducted many international ensembles including the Berlin Philharmonic, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Seattle Symphony and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. In the opera house, Emelyanychev has conducted Handel’s Rinaldo at Glyndebourne, the same composer’s Agrippina as well as Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and Mozart’s Die Entführing aus dem Serail at the Opernhaus Zürich. He has also conducted Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte and Così fan tutte with the SCO at the Edinburgh International Festival. He has collaborated closely with US soprano Joyce DiDonato, including international touring and several recordings.

Among his other recordings are keyboard sonatas by Mozart, and violin sonatas by Brahms with violinist Aylen Pritchin. He has also launched a project to record Mozart’s complete symphonies with Il Pomo d’Oro. In 2019, he won the Critics’ Circle Young Talent Award and an International Opera Award in the newcomer category. He received the 2025 Herbert von Karajan Award at the Salzburg Easter Festival.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

©

Andrej

Grilc

19-21 March, 7.30pm

Edinburgh | Glasgow | Aberdeen sco.org.uk

Beethoven, Pekka & Dreamers’ Circus

Pekka Kuusisto director/violin

Dreamers’ Circus:

Ale Carr cittern

Nikolaj Busk piano/accordion

Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen violin

Kindly supported by LEARN MORE

Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony interspersed with Nordic folk tunes

Scottish Chamber Orchestra

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

© Christopher Bowen

Support Us

Each year, the SCO must fundraise around £1.2 million to bring extraordinary musical performances to the stage and support groundbreaking education and community initiatives beyond it.

If you share our passion for transforming lives through the power of music and want to be part of our ongoing success, we invite you to join our community of regular donors. Your support, no matter the size, has a profound impact on our work – and as a donor, you’ll enjoy an even closer connection to the Orchestra.

To learn more and support the SCO from as little as £5 per month, please contact Hannah at hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk or call 0131 478 8364.

SCO is a charity registered in Scotland No SC015039.

Photo: Stuart Armitt

The