METAMORPHOSIS OF INDIGENOUS LIVING :

An Evolutionary Journey of Cultural Resilience in Eksar Gaothan

Collaborative research project

January 2023

Rohit Mujumdar, SEA

Sanya Jain

SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE, NAVRACHANA UNIVERSITY

CONTENTS

Acknowledgement

Abstracts

1. The Set-off

1.1. What is Climate Change?

1.2. Mumbai : A Climatic Upheaval

1.3. What is the concern?

1.3.1. Research context and Significance

Aim

Objectives

Research questions and Sub-questions

2. Structuring the Ideology

2.1. Establishing a link

2.2. Building a theoretical framework

3. What is Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living?

3.1. Building practices through Indigenous Eyes

4. Site Introduction

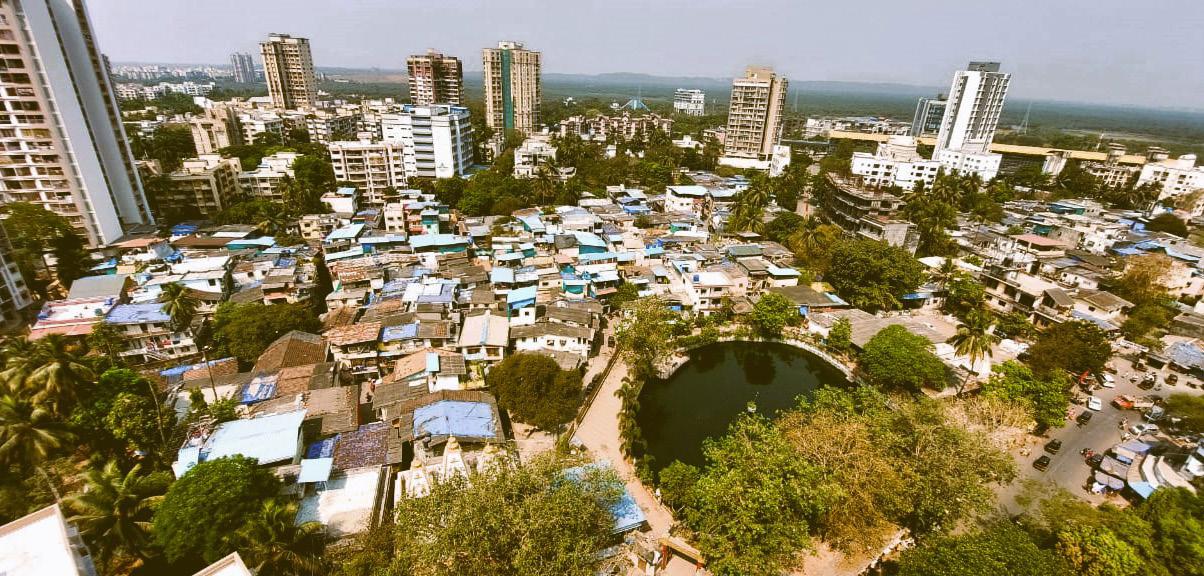

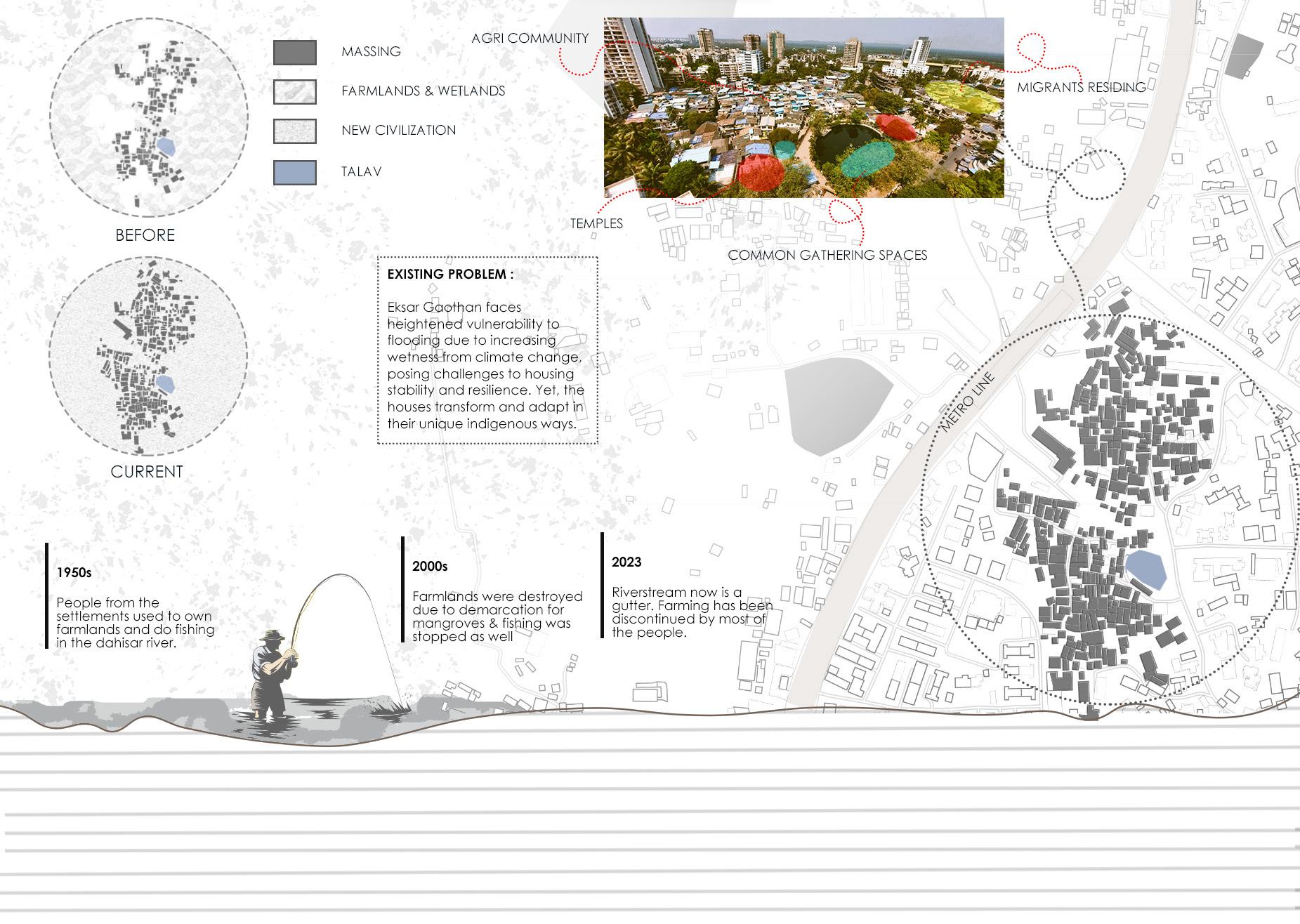

4.1. Eksar Gaothan : A Cultural Oasis Amidst Urban Dynamics

4.2. Site analysis

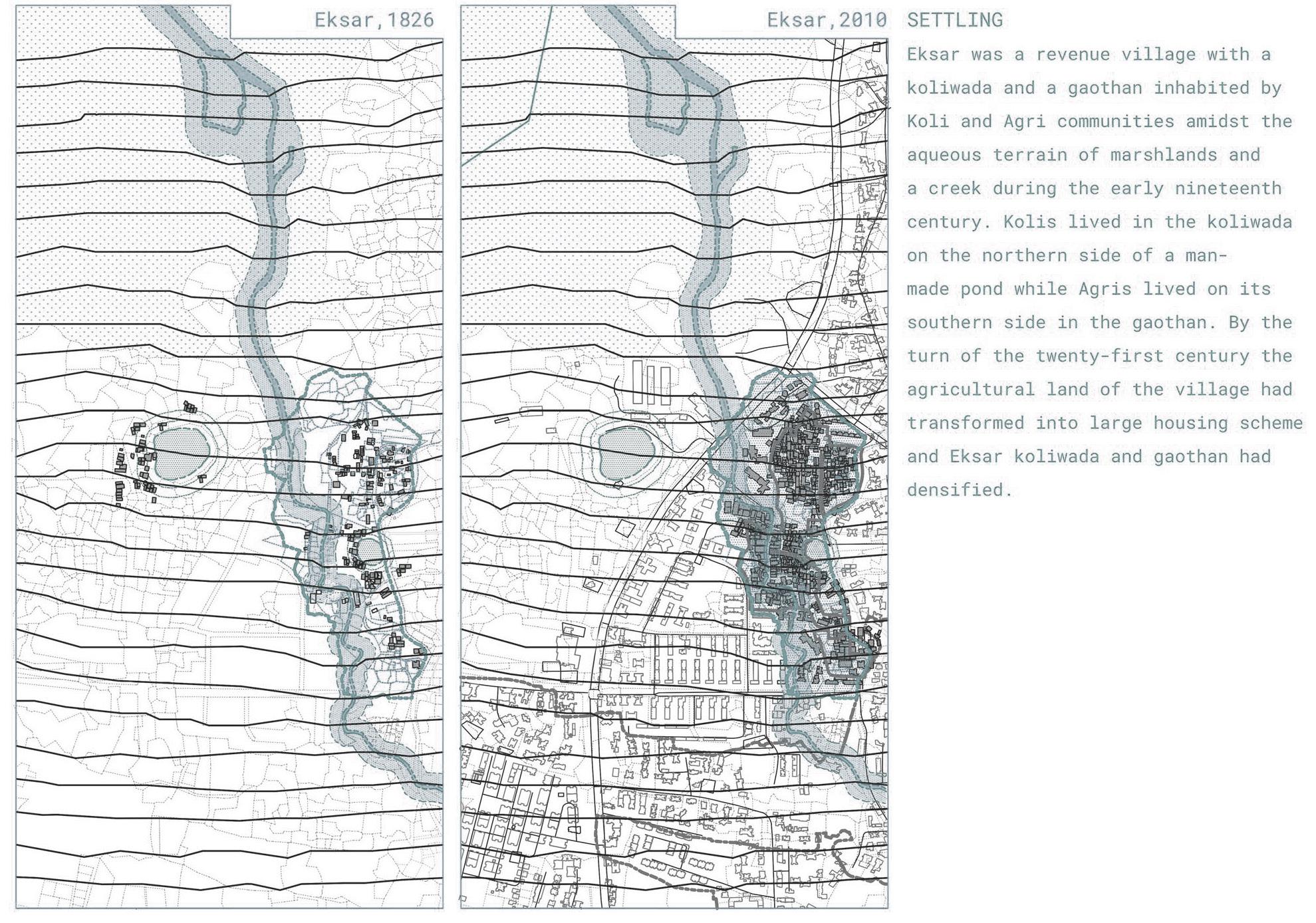

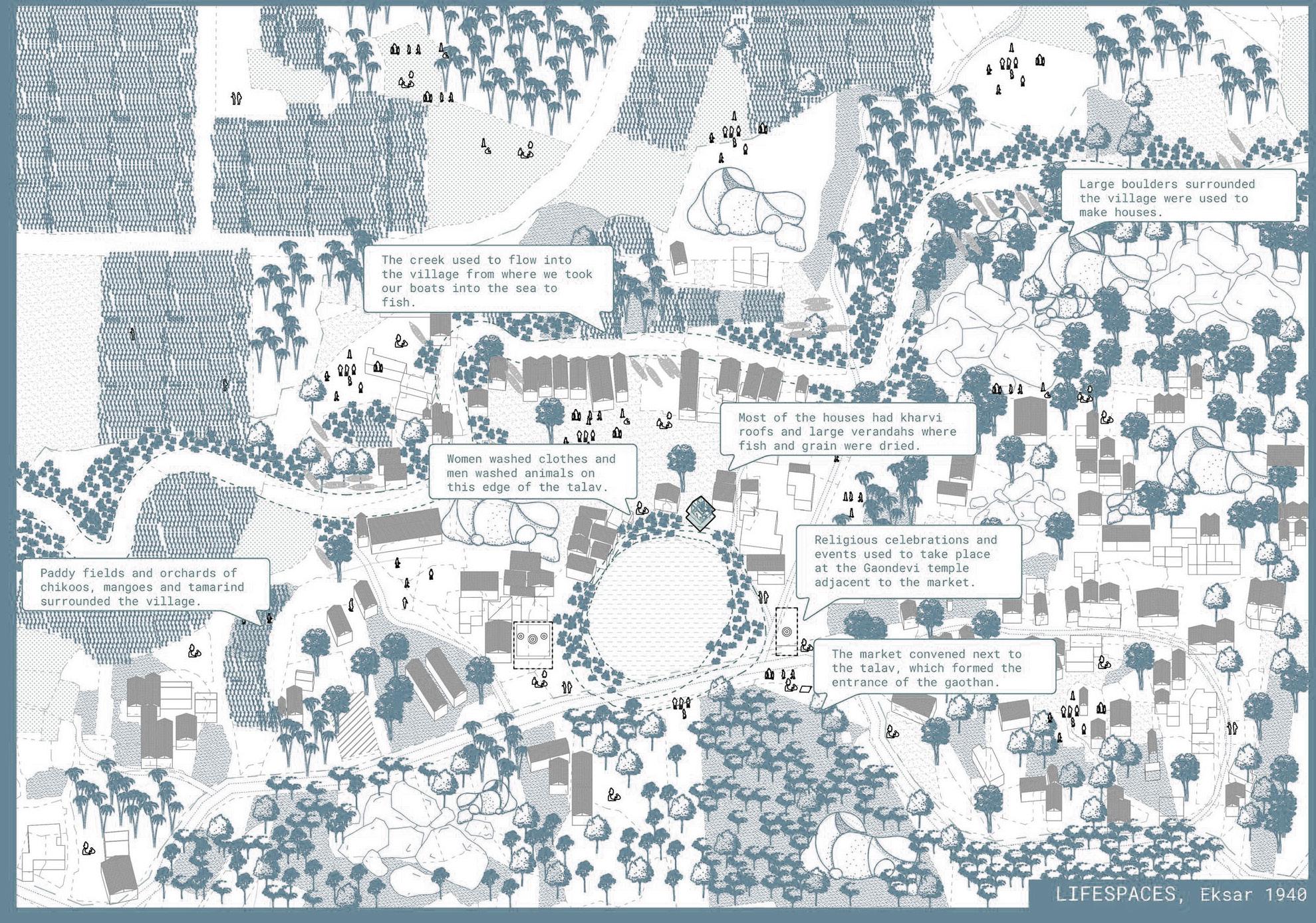

4.3. SIte mapping

4.4. Oral histories : Eksar

5. Chapter 1 : A Staircase to Haven

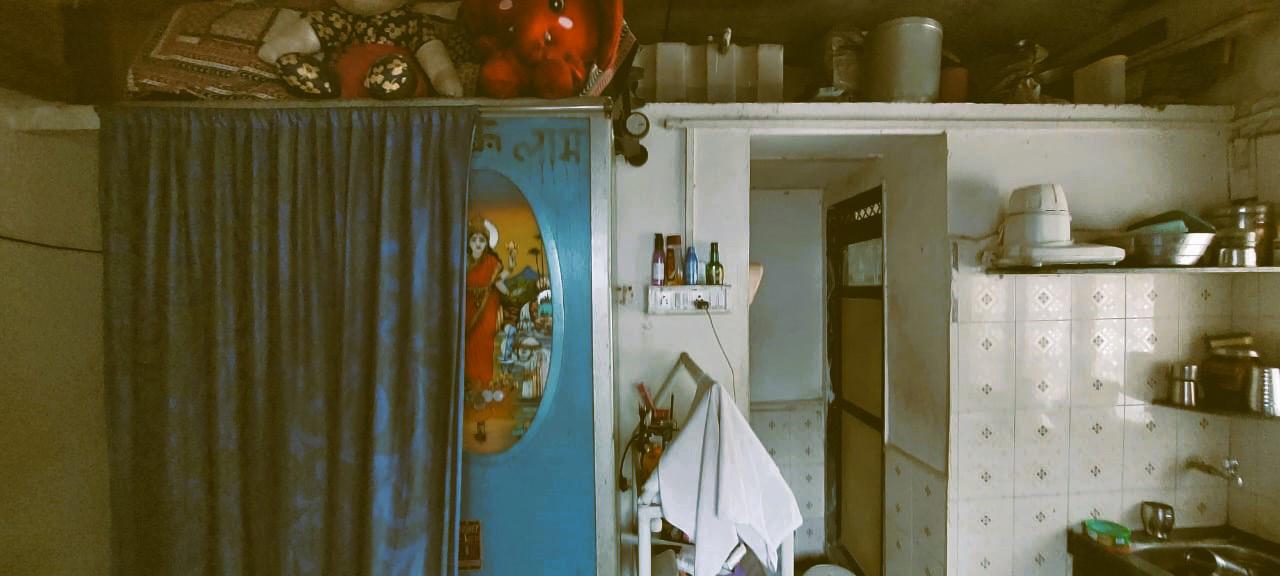

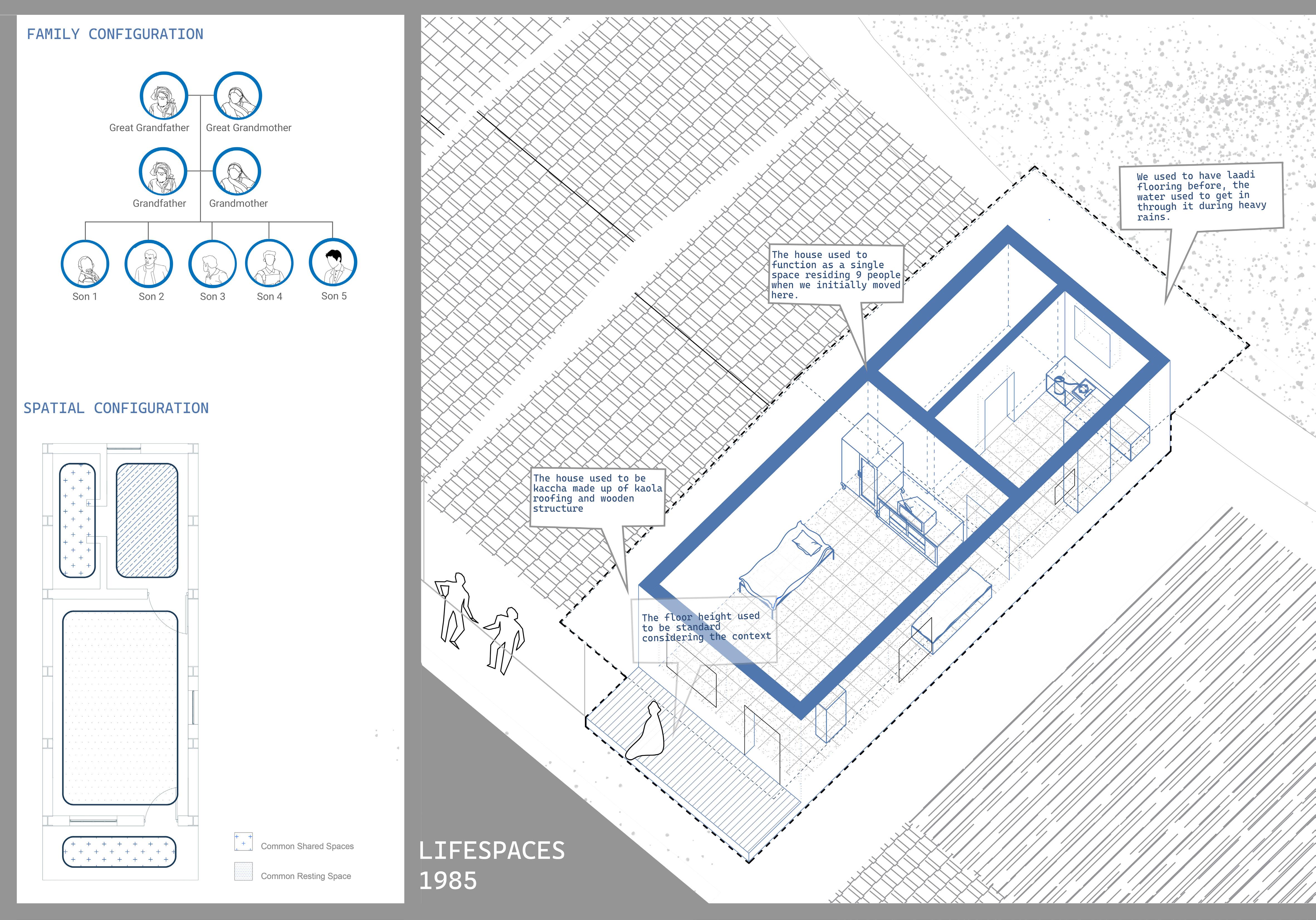

5.1. Lifespaces 1985

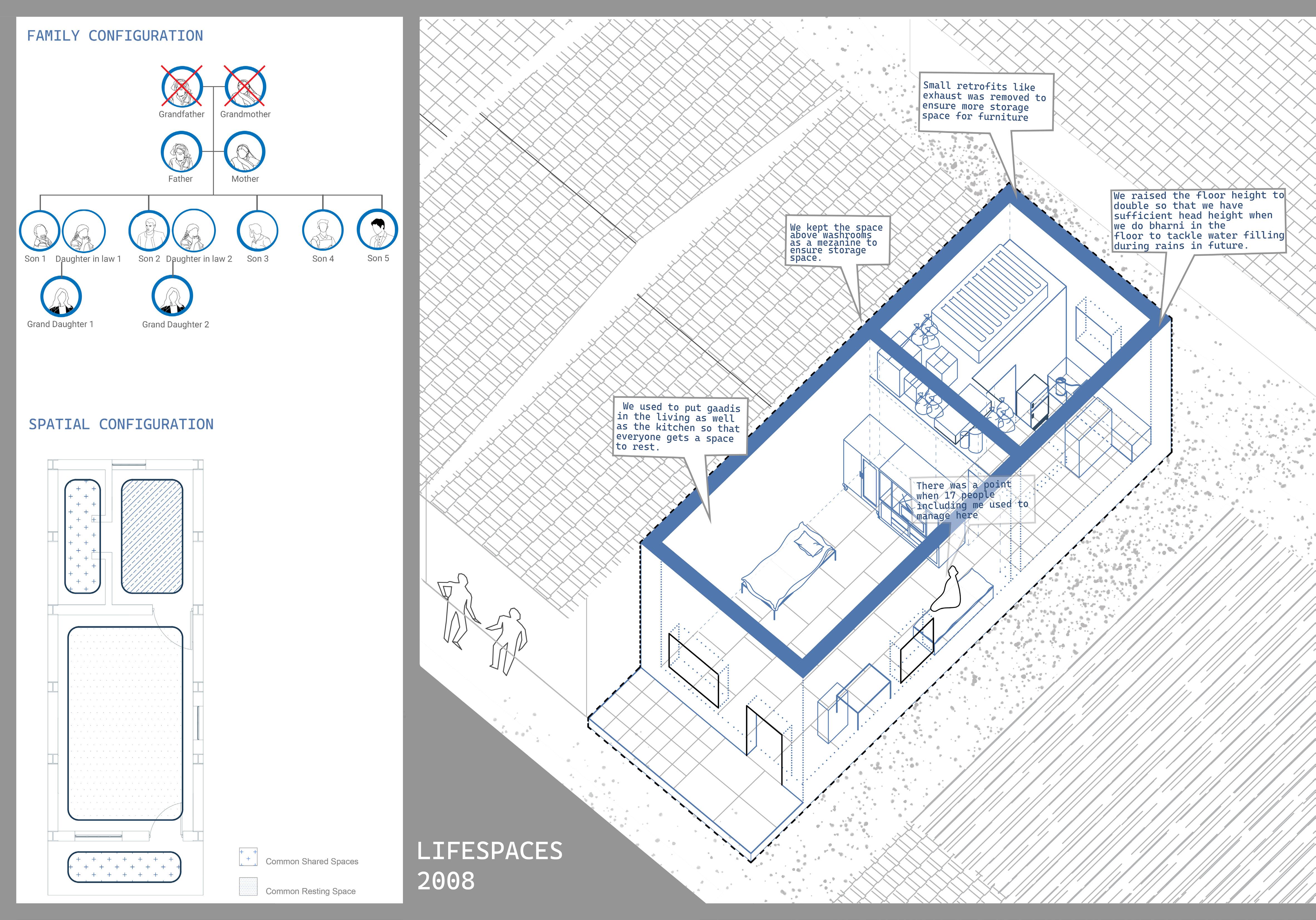

5.2. Lifespaces 2008

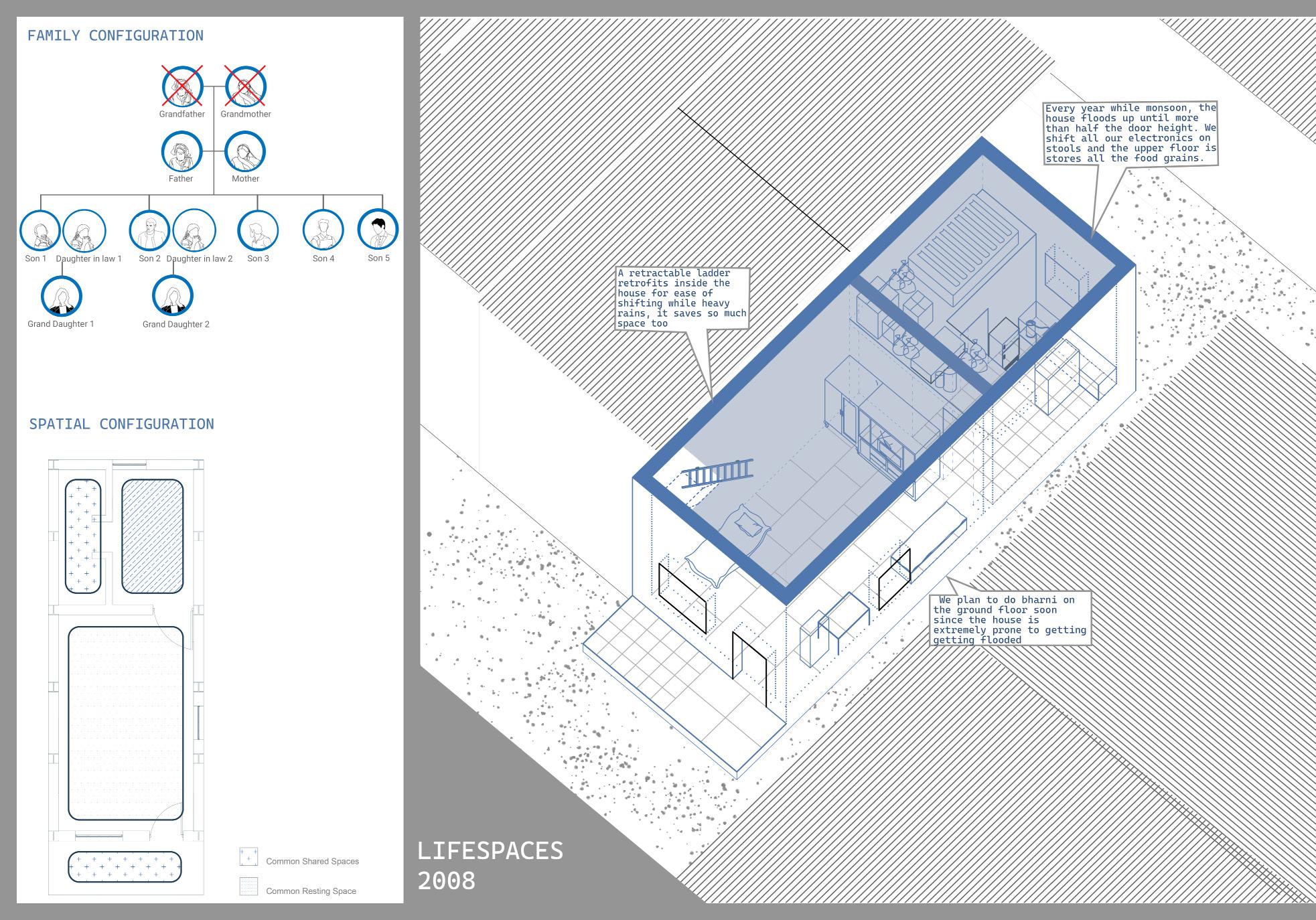

5.3. Lifespaces 2008

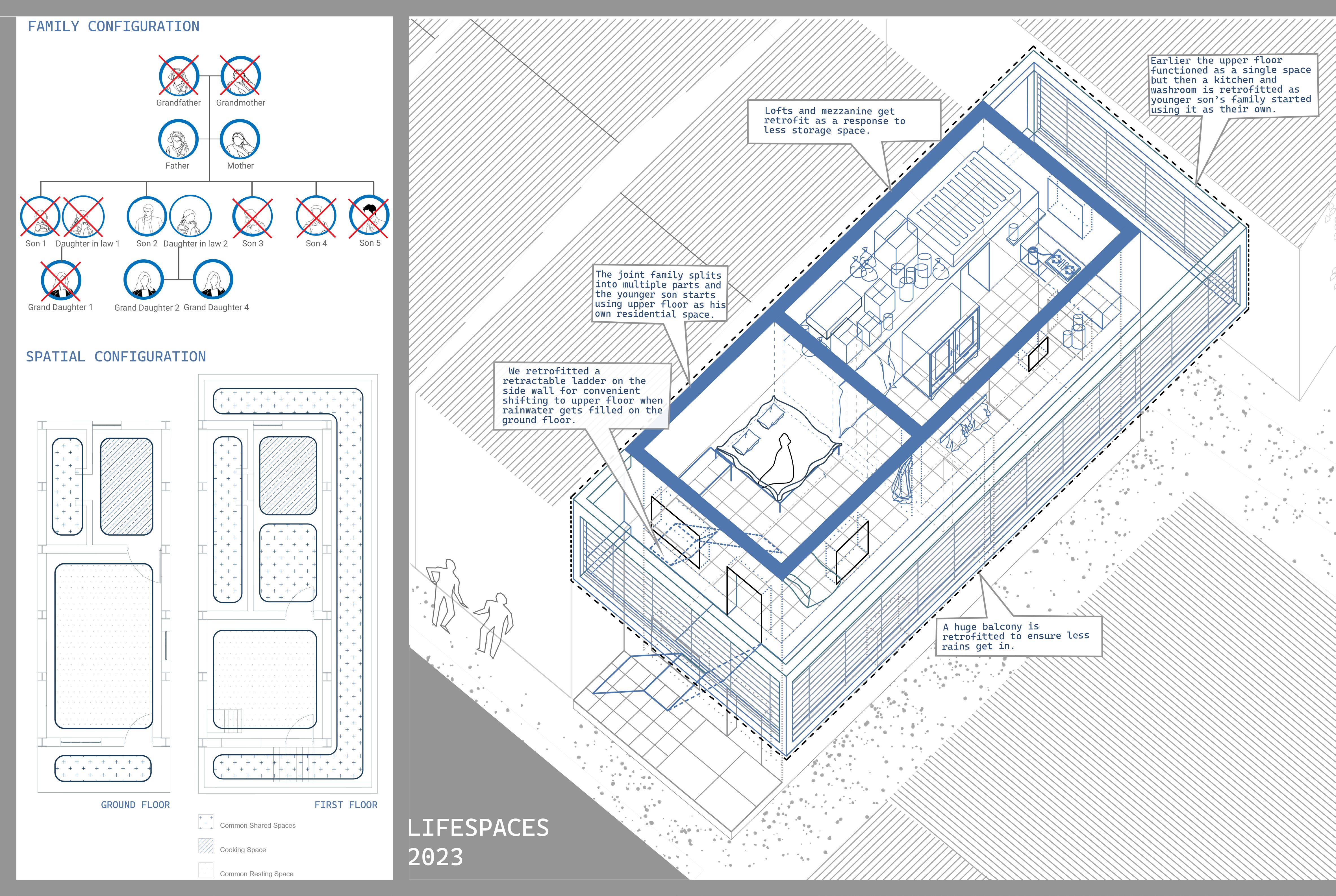

5.4. Lifespaces 2023

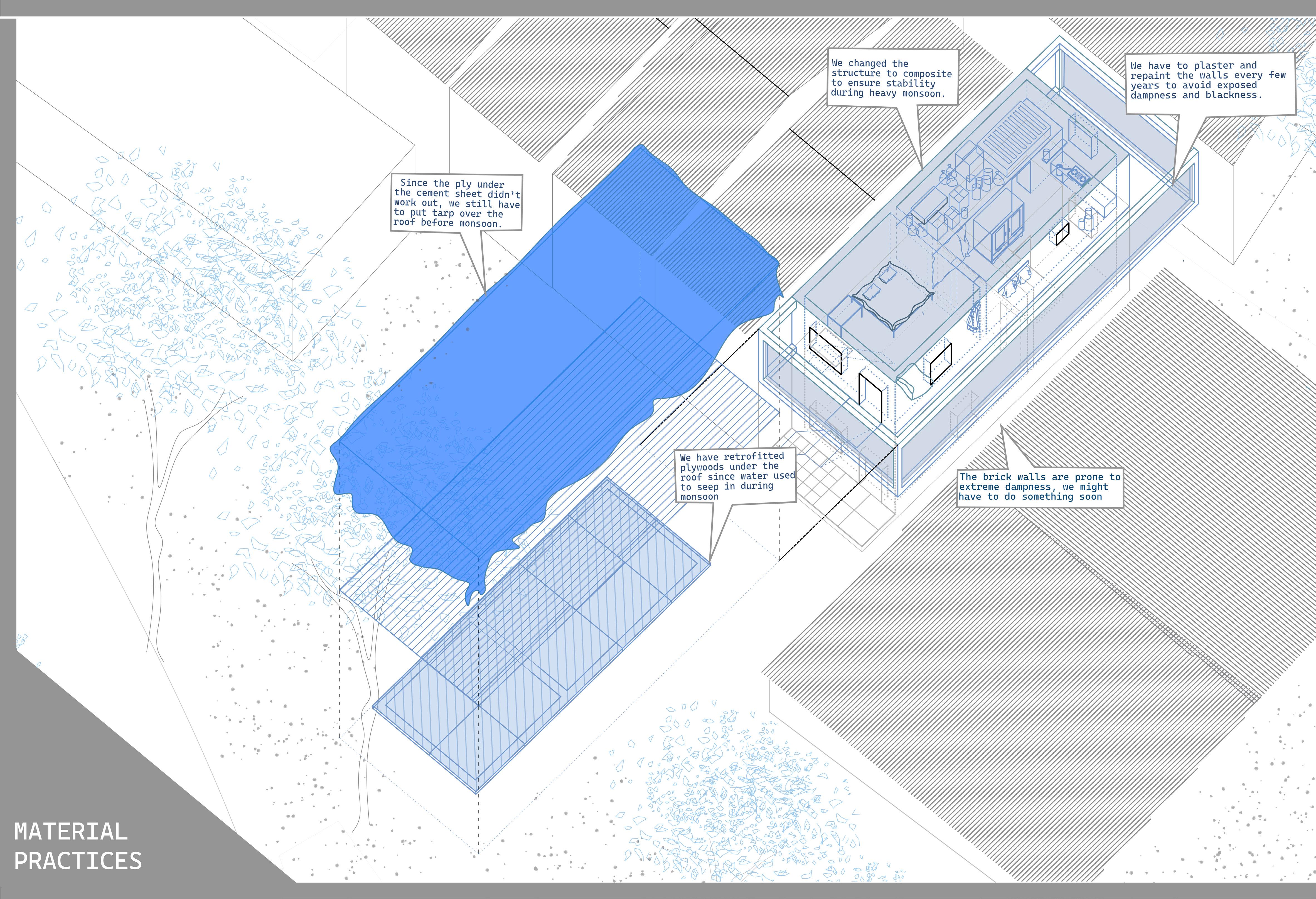

5.5. Material Practices

5.6. Conclusive analogies

6. Chapter 2 : Undergoing Metamorphosis

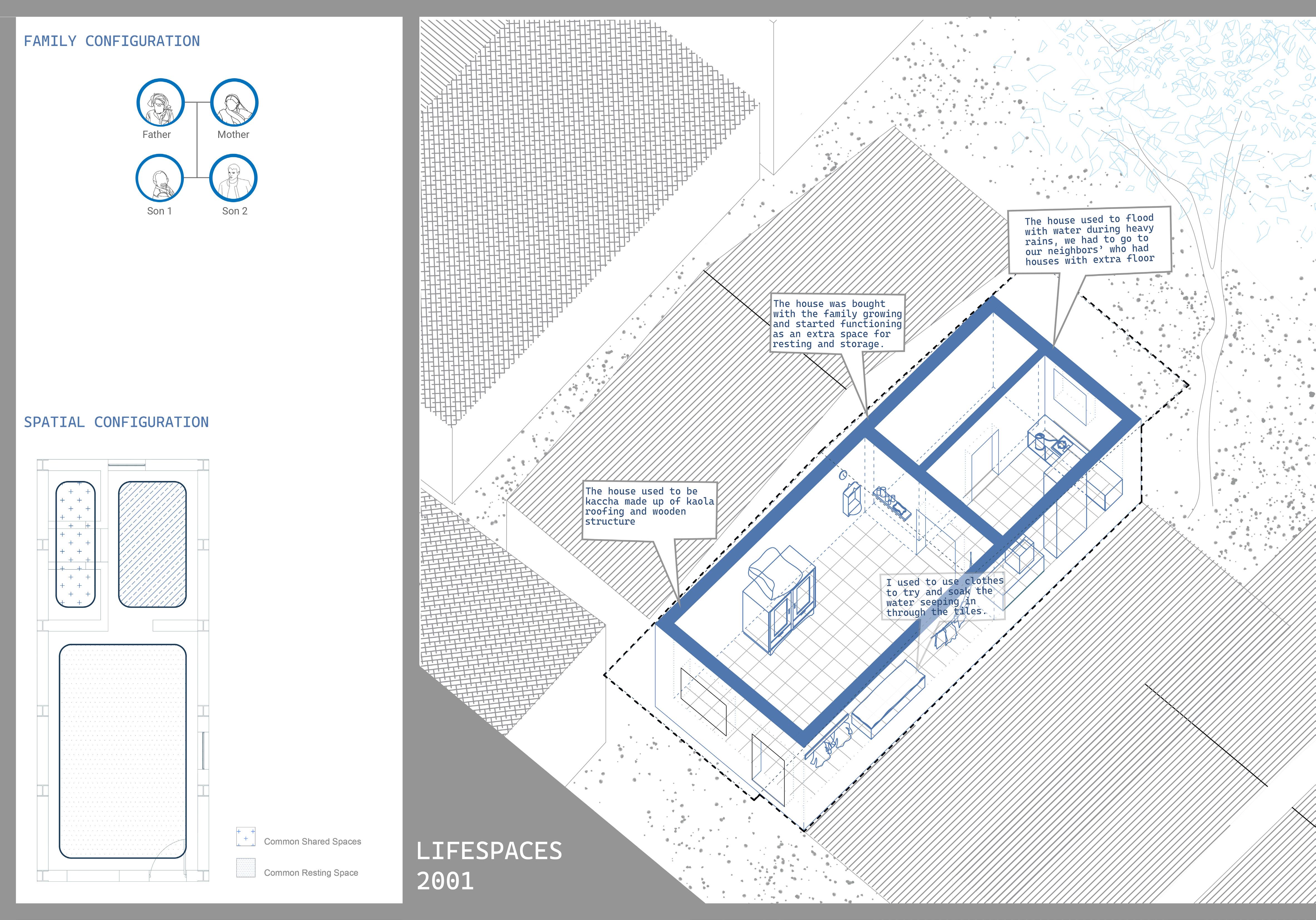

6.1. Lifespaces 2001

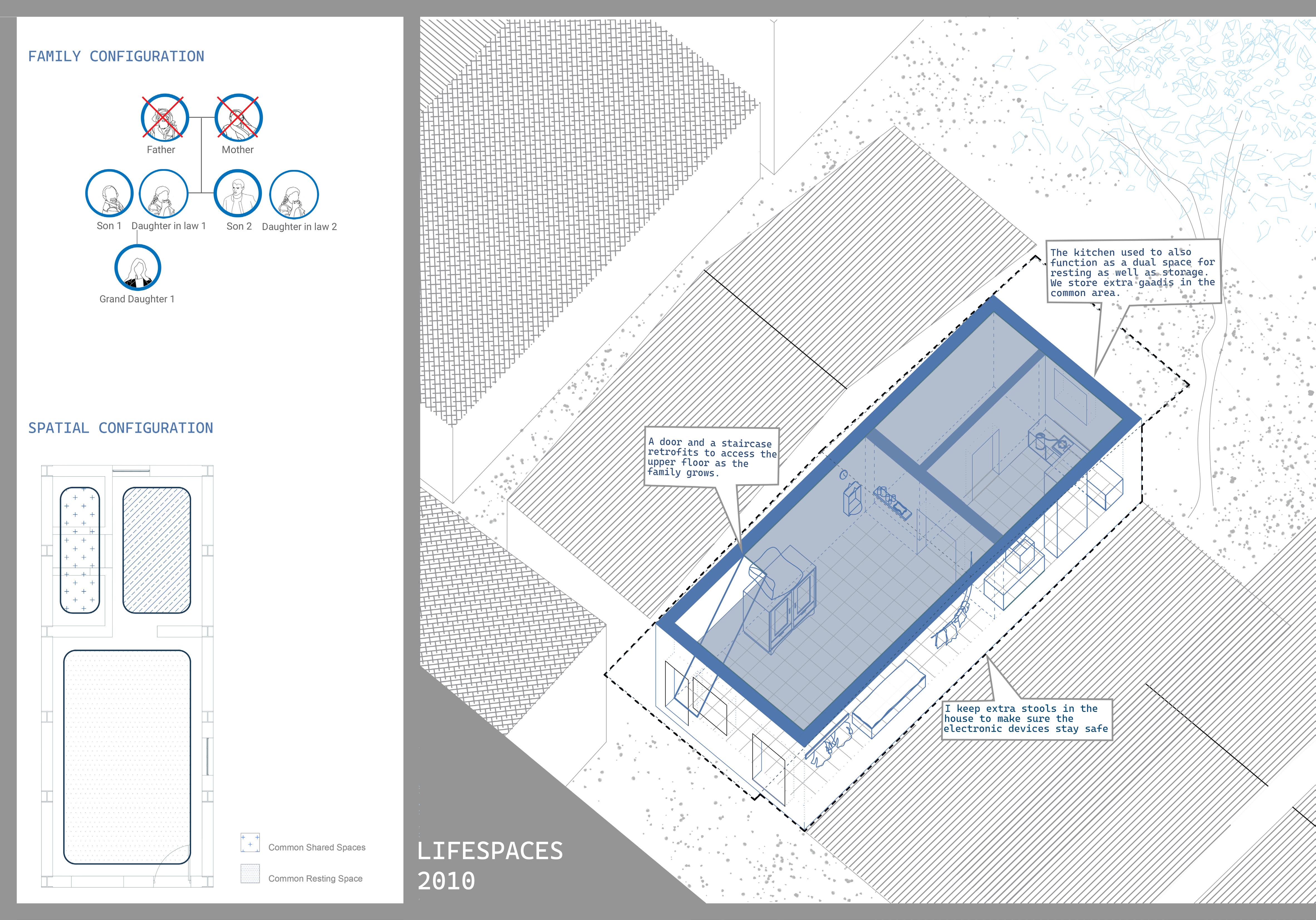

6.2. Lifespaces 2010

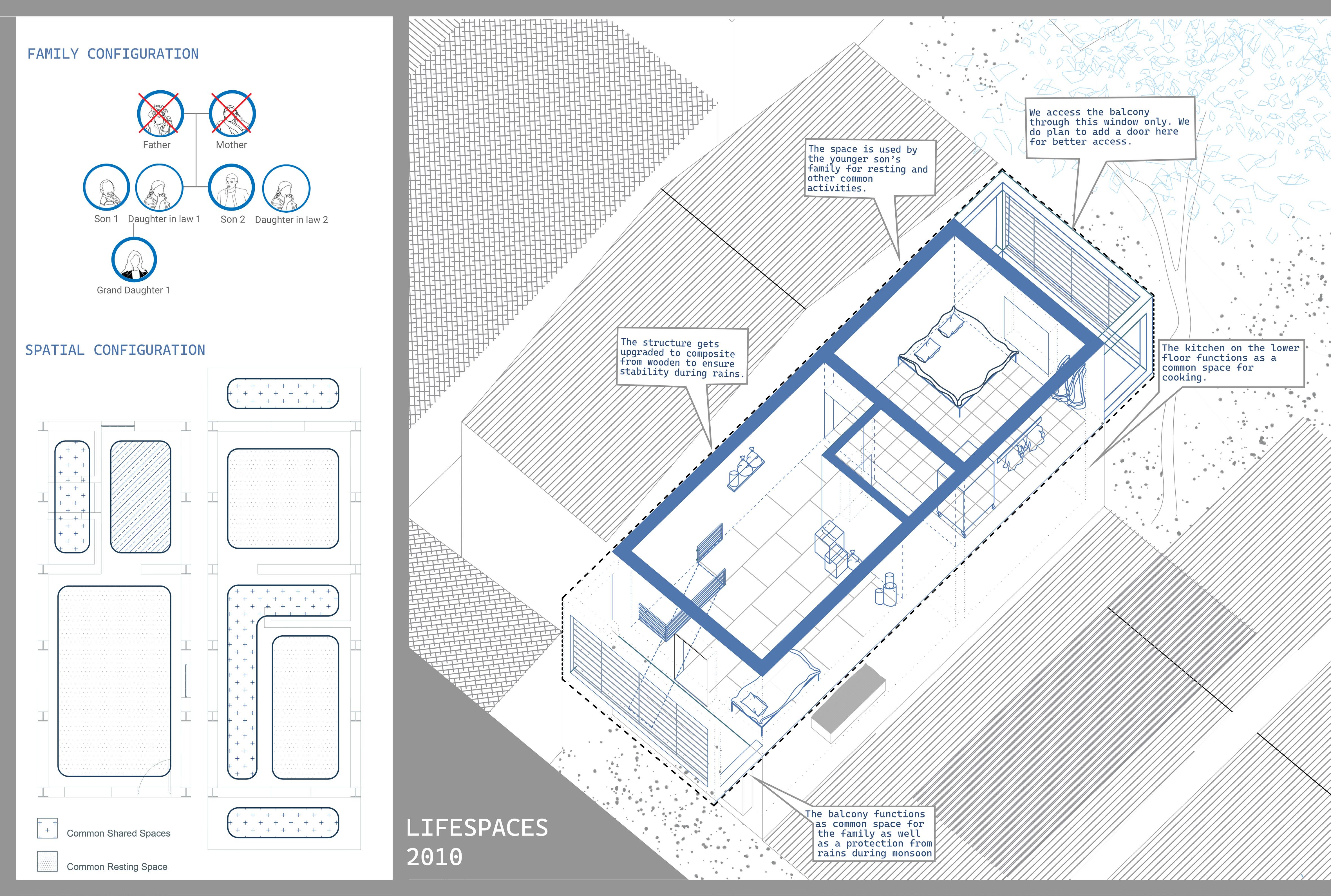

6.3. Lifespaces 2010

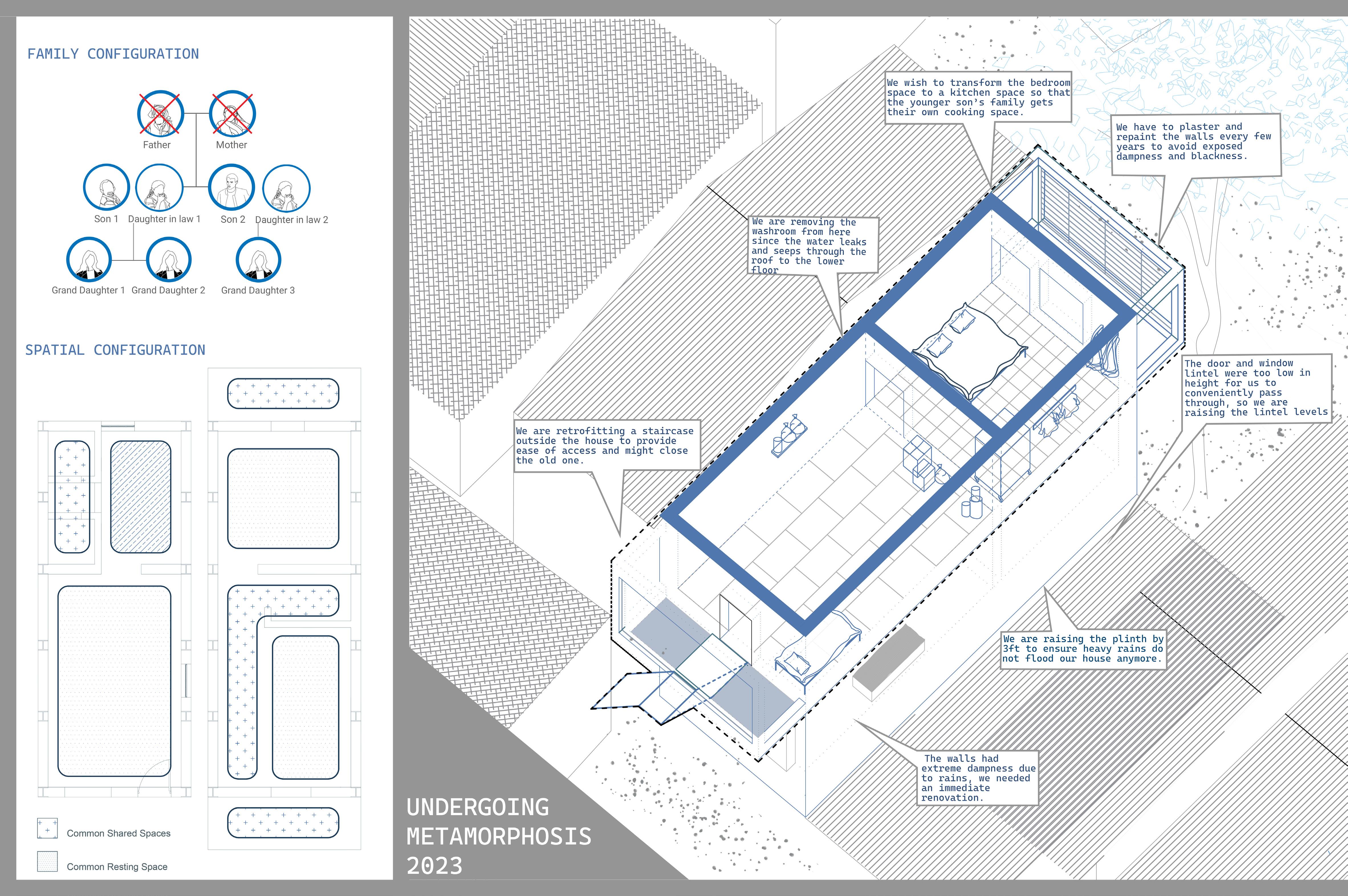

6.4. Undergoing Metamorphosis 2023

6.5. Conclusive analogies

7. Lifespaces : Conclusion

Citation Bibliography

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Mr. Rohit Mujumdar for his invaluable support and guidance throughout the completion of this thesis. His unwavering encouragement, expertise, and insightful feedback have been instrumental in shaping the research. Rohit’s extensive knowledge and expertise in the field provided me with invaluable insights and perspectives that enriched the content of this thesis.

Beyond his academic guidance, I am truly grateful for Rohit’s mentorship and encouragement. His genuine belief in my abilities and dedication to my personal and professional growth have been a source of inspiration and motivation throughout this research journey.

I extend my sincere appreciation to Rohit for his patience, understanding, and unwavering support during moments of challenges and obstacles. His mentorship has not only shaped this thesis but has also contributed to my personal and intellectual development.

I would also like to give regards to Ruchita Sarvaiya for being such a great colleague to work with. I am grateful for her friendship, for her selfless guidance at any time and for believing in me constantly.

And finally, to the faculty as well as the students of SEA (School of Environment and Architecture, Mumbai) for welcoming me with such warmth. My momentary visit there opened me up to such great intellect and persuaded me to look at things with multiple perspectives.

Finally, I want to thank the SEDA professors and my closest friends, Parth, Dhruvin, Stuti, Prithvi, Naishar, and Aashna, for always being there for me. I appreciate you always being by my side and being there to listen when things became tough.

Abstract

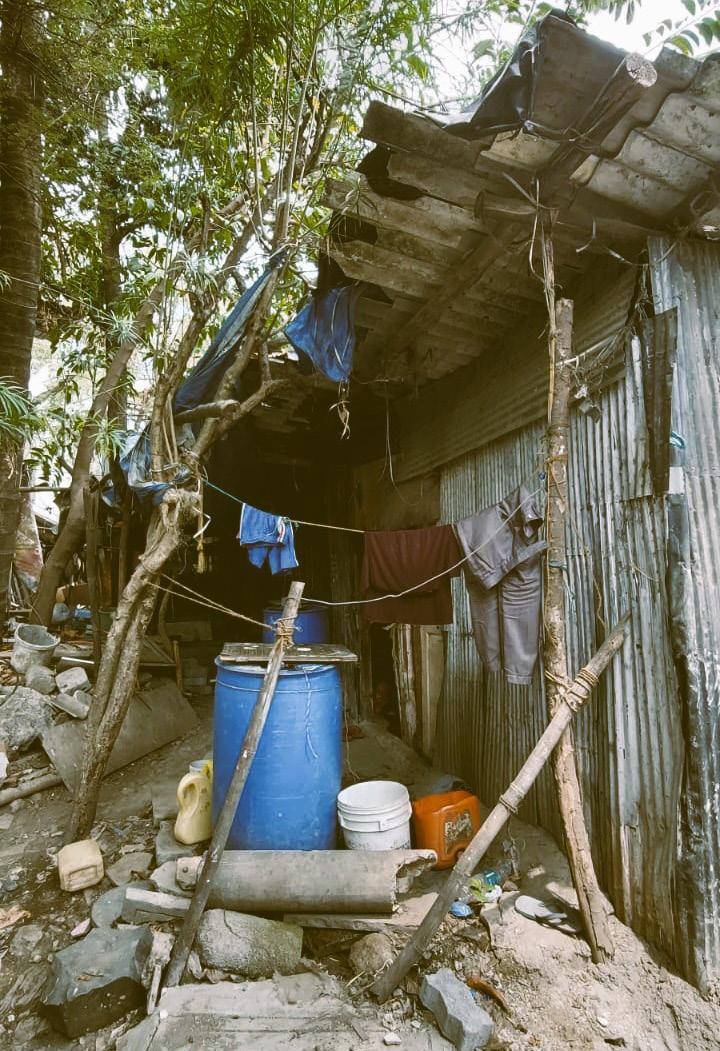

This thesis examines the metamorphosis of indigenous communities living in Eksar Gaothan, a neighborhood in Mumbai, India, in the context of their interaction with wetness. The study investigates how the presence of wetlands and the challenges and opportunities they bring have influenced the social, cultural, and environmental dimensions of indigenous life in this urban setting. By analyzing the transformative effects of wetness, this research aims to provide insights into the complex dynamics shaping the indigenous community’s existence.

Through a combination of qualitative research methods such as interviews, ethnographic observations, and ecological assessments, this study explores the experiences, perspectives, and adaptations of the indigenous residents. It investigates how wetness affects their livelihoods, cultural practices, and community cohesion. Furthermore, the research addresses the environmental impacts of wetness, including issues related to flooding, land use, and ecological conservation.

The thesis also delves into the resilience strategies employed by the indigenous community to navigate the changes brought about by wetness. It examines how traditional knowledge, cultural practices, and community-based initiatives contribute to sustainable living and coping mechanisms. Moreover, the study highlights the importance of recognizing and valuing indigenous perspectives in urban planning and environmental decision-making processes.

The findings of this thesis contribute to the understanding of the metamorphosis experienced by indigenous communities living amidst wetness in urban environments. By emphasizing the significance of wetlands for indigenous livelihoods, cultural identity, and environmental sustainability, the research aims to promote inclusive and informed approaches to infrastructural development. The insights gained from this study can inform policymakers, urban planners, architects and community organizations in their efforts to create resilient and culturally sensitive infrastructural and urban spaces.

Ultimately, this thesis seeks to empower and advocate for the well-being of the indigenous population in Eksar Gaothan by recognizing their unique experiences in the face of wetness. By highlighting the transformative nature of their lived realities, the research contributes to fostering sustainable development practices that prioritize the preservation of indigenous cultures and the conservation of wetland ecosystems.

1. The Set-off

I was considering a concept for my fourth year undergraduate studio and browsing the internet along with reading various articles about what might be something that was an obvious concern. While looking for the same, these news stories on the alarming effects of climate change used to appear in my feed very frequently. These publications discussed triggering consequences of climate change in many places, including nations worldwide. They threw me off guard and made me think why it is occurring? And so, can architects or architecture do anything about it?

1.1 What is Climate Change?

Climate change, according to (United Nations, n.d.), refers to long-term changes in the Earth’s climate system - particularly changes in temperature, precipitation, and other weather patterns - brought about by an increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs) in its atmosphere. This change has proven to be anthropogenic, particularly the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas has significantly increased the levels of GHGs in the atmosphere. According to the (IEA – International Energy Agency, n.d.), buildings and construction sectors combined are responsible for approximately 39 percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions. If yes, how can the design field address energy-efficient designs, usage of renewable energy, green infrastructure, sustainable / local materials and construction methods in an effort towards reducing the impact of energy emissions?

1.2 Mumbai : A climatic upheaval

Mumbai is one of the the cities most susceptible to risks brought on by Climate change, such as sea level rise, urban floods and storm surge. The city is vulnerable to dangers, as seen by 2005 Floods, which claimed 410 lives and forced thousands to flee their homes, particularly in low-income neighbourhoods. Climate change has had a significant impact on Mumbai, exacerbating existing challenges faced by the city. Rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, and sea-level rise have contributed to the increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like cyclones, heatwaves, and heavy monsoons. These changes have disrupted the delicate balance of Mumbai’s ecosystem, leading to urban flooding, waterlogging, and infrastructure damage. During the monsoon season, households in Mumbai often face challenging conditions. Poor drainage systems and inadequate infrastructure make the city vulnerable to waterlogging, causing inconvenience and health hazards for residents. Many households struggle with leaks, seepage, and water damage, particularly in low-lying areas. Moreover, power outages and disruptions in transportation further complicate daily life, making it difficult for people to commute and carry out their routine activities. Efforts are being made to improve Mumbai’s resilience to climate change, but continued adaptation measures and sustainable urban planning are crucial to mitigate the impact on households and ensure a more resilient future for the city.

According to Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP), Mumbai is one of the C40 (Cities Climate Leadership Group) members. Mumbai agreed to C40’s 2020 pledge, which is in accordance with the Paris agreement which calls for cutting the Green House Gas emissions by 50% by 2030, assistance to the Government of India in the accomplishment of its Nationally Determined Contributons, and a transition to net zero by 2050. With technical assistance from World Resources Institute India (WRI India), which has been engaged as a knowledge partner, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) is creating the city’s first-ever climate action plan (CAP) in accordance with the C40 Climate Action Planning Framework in order to meet C40’s Leadership Standards. season, households in Mumbai often face challenging conditions. Poor drainage systems and inadequate infrastructure make the city vulnerable to waterlogging, causing inconvenience and health hazards for residents. Many households struggle with leaks, seepage, and water damage, particularly in low-lying areas. Moreover, power outages and disruptions in transportation further complicate daily life, making it difficult for people to commute and carry out their routine activities. Efforts are being made to improve Mumbai’s resilience to climate change, but continued adaptation measures and sustainable urban planning are crucial to mitigate the impact on households and ensure a more resilient future for the city.

1.3 What is the Concern?

Amidst the looming threat of changing weather patterns and rising sea levels, discussions about the future of Mumbai depict extreme possibilities. Various perspectives on how to respond to projected sea-level rise for 2050 have emerged. These include expanding waterways and constructing tall, solid walls along their edges to divert monsoonal waters, demolishing slums near water bodies to enhance drainage capacity, relocating the entire city to higher ground, and even considering a post-apocalyptic submerged city for recreational purposes. While such conversations aim to prepare the city for a future beyond climate tipping points, they often neglect the current needs and rights of the majority of households. Additionally, the envisioned infrastructure solutions, primarily focused on containment and drying out the city, can paradoxically increase its vulnerability to natural disasters or merely displace existing problems elsewhere.

1.3.1 Research context and Significance

This collaborative research project aims to contribute a tiny component to the ongoing action-research project titled Stories of Climate Action (SCA): Democratising planning in Mumbai’s wetscapes by contributing to expanding the architectural dimensions for climate action expertise. SCA is coordinated by Rohit Mujumdar (PI, Assistant Professor, School of Environment and Architecture), Lalitha Kamath (CoPI, Associate Professor, Tata Institute for Social Sciences) and Nikhil Anand (CoPI, Associate Professor, University of Pennsylvania) under the institutional umbrella of the Centre for Spatial Studies (CSS) of the Society for Environment and Architecture, Mumbai.

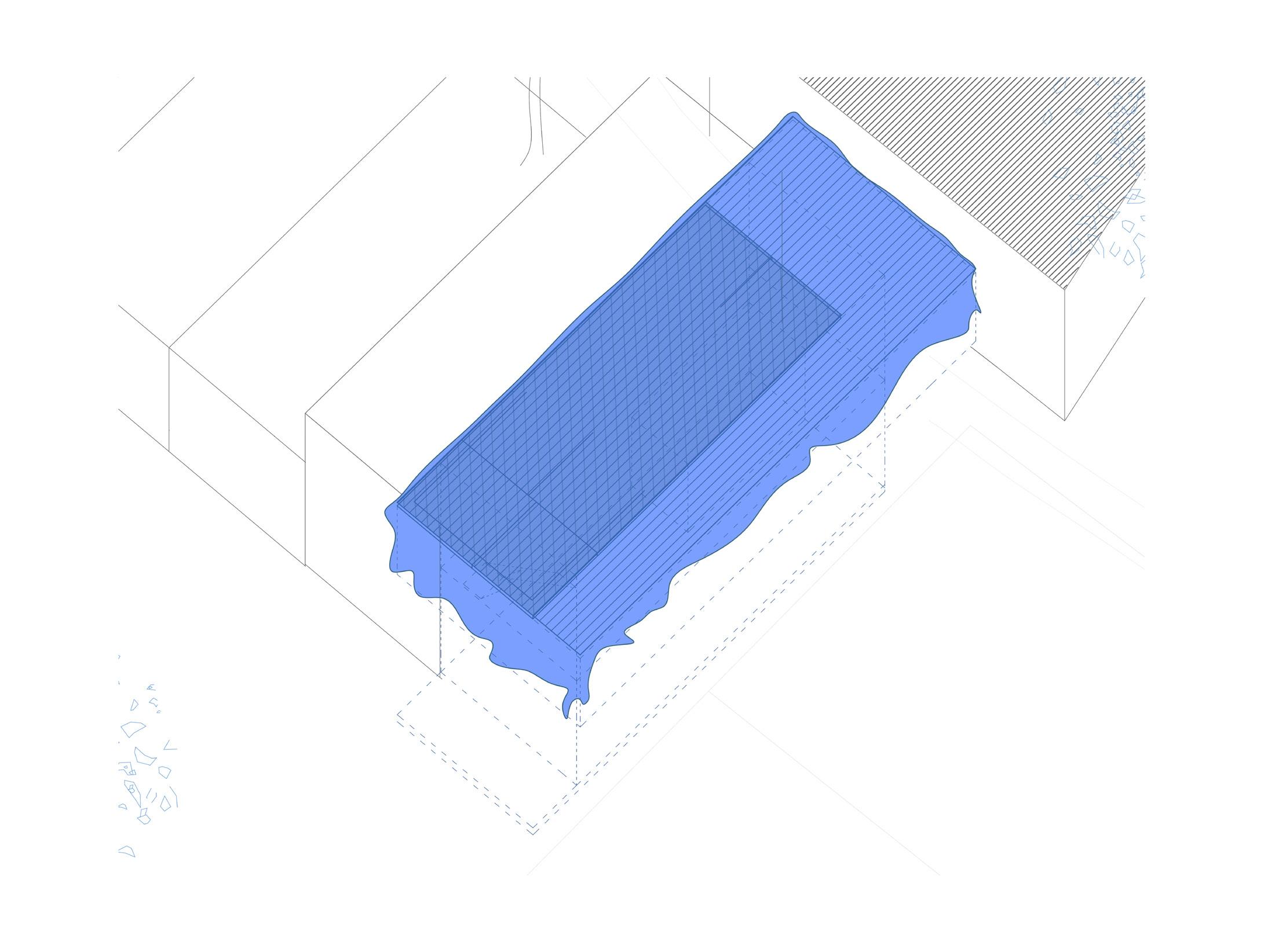

This research embarks on a comprehensive exploration that intricately weaves together the historical nuances of the natural environment and the social dynamics of a specific location. This intertwined narrative is termed the “Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living.” Centered around the monsoonal estuary of the Dahisar River, this study employs a range of analogies—such as layering, shedding, folding, fission, and fusion—to meticulously dissect the intricate interplay of formal and spatial processes. These processes are profoundly influenced by a myriad of factors, including the topography of the land, human settlement patterns, water flow dynamics, and the adaptive practices employed in shaping both the physical landscape and its built structures.

At its core, the research asserts that tackling climate-related challenges requires a holistic approach—one that actively engages in ongoing and meaningful dialogues spanning diverse knowledge systems. This inclusivity extends to ordinary perspectives and practices that have historically shaped the metamorphosis of indigenous living. By broadening the definition of expertise in climate mitigation and adaptation and upholding principles of equity, we can effectively democratize climate action, particularly in urban areas confronted with escalating water-related issues due to climate change.

As the relentless and intense monsoonal wetness becomes an integral part of the daily lives of residents, the narrative shifts its focus to the aspirations of households within this context. These households yearn for a novel, cost-free abode situated on elevated ground within the estuarine landscape of the Dahisar River. They aim to leverage the policy instrument of incentivizing Floor Space Index to drive housing redevelopment in this area. However, the realization of these aspirations is far from uniform, hampered by an array of challenges. Even among those fortunate enough to secure new residences on elevated ground, the perpetual cyclical wetness of the monsoonal estuary presents a formidable challenge. Within this complex landscape, the metamorphosis of indigenous living surfaces as a strategy to enhance the resilience of both traditional and contemporary structures against the dual onslaught of everyday wetness and extreme monsoon events. However, it is essential to acknowledge that these strategies bear both strengths and limitations.

In summation, this research journey navigates the nexus of nature, society, and adaptation. By threading together historical contexts, urban dynamics, and local practices, it offers insights into democratizing climate action and fostering equitable resilience. The intertwined stories of indigenous living and its metamorphosis present a canvas upon which climate solutions are woven, blending ancestral wisdom and innovative adaptation strategies to pave a way forward in the face of climate uncertainty.

Aim

Indigenous experiences, practices and knowledges of inhabiting estuarine coastal wetscapes in cities such as Mumbai can offer avenues to expand climate action expertise.

Objectives

• To formulate a methodological inquiry into mapping indigenous senses (experiences, practices and knowledges) of inhabiting Mumbai’s tranforming estuarine coastal wetscapes.

• To articulate the architectural implications of indigenous senses and practices for expanding climate (mitigation and adaptation) expertise.

Research question and subquestions

How can stories of indigenous experiences, practices and knowledge of inhabiting transforming estuarine wetscapes of coastal cities such as Mumbai be drawn into a creative conversation with expert knowledge of climate adaptation?

• How does expert knowledge articulate climate action amidst ecological and economic uncertainity in Mumbai?

• How can indigenous experiences, practices and knowledge of inhabiting coastal Mumbai’s estuarine wetscapes help articulate a constructive engagement to expand climate action expertise in the architectural field?

• How can the existing landscape of field (Eksar Gaothan) be uncovered and drawn?

• How are the settlements adapting to the ecological and urban change that existed throughout and continues to exist?

• What are the challenges faced by the households in the settlement followed by this change?

2. Structuring the Ideology

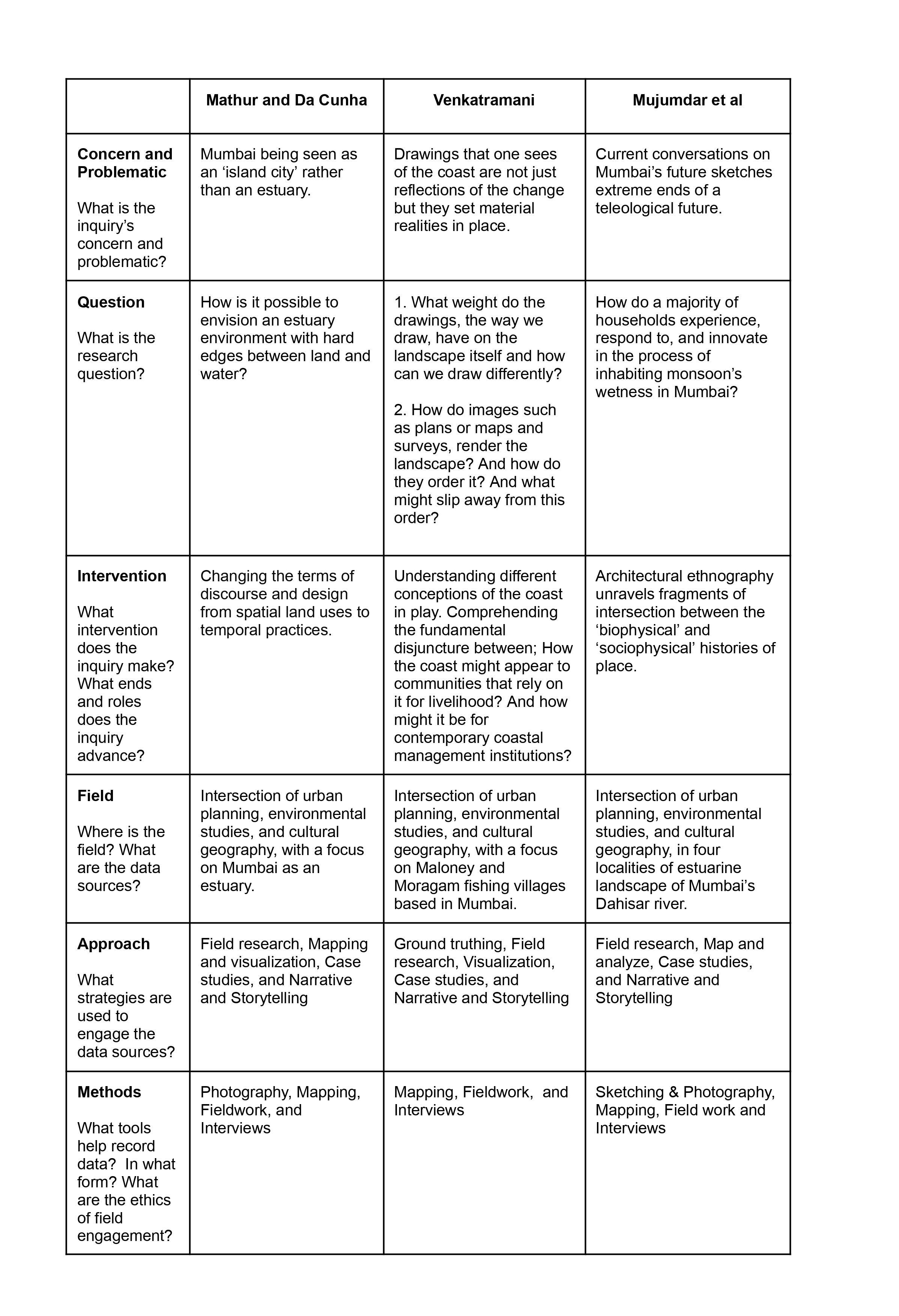

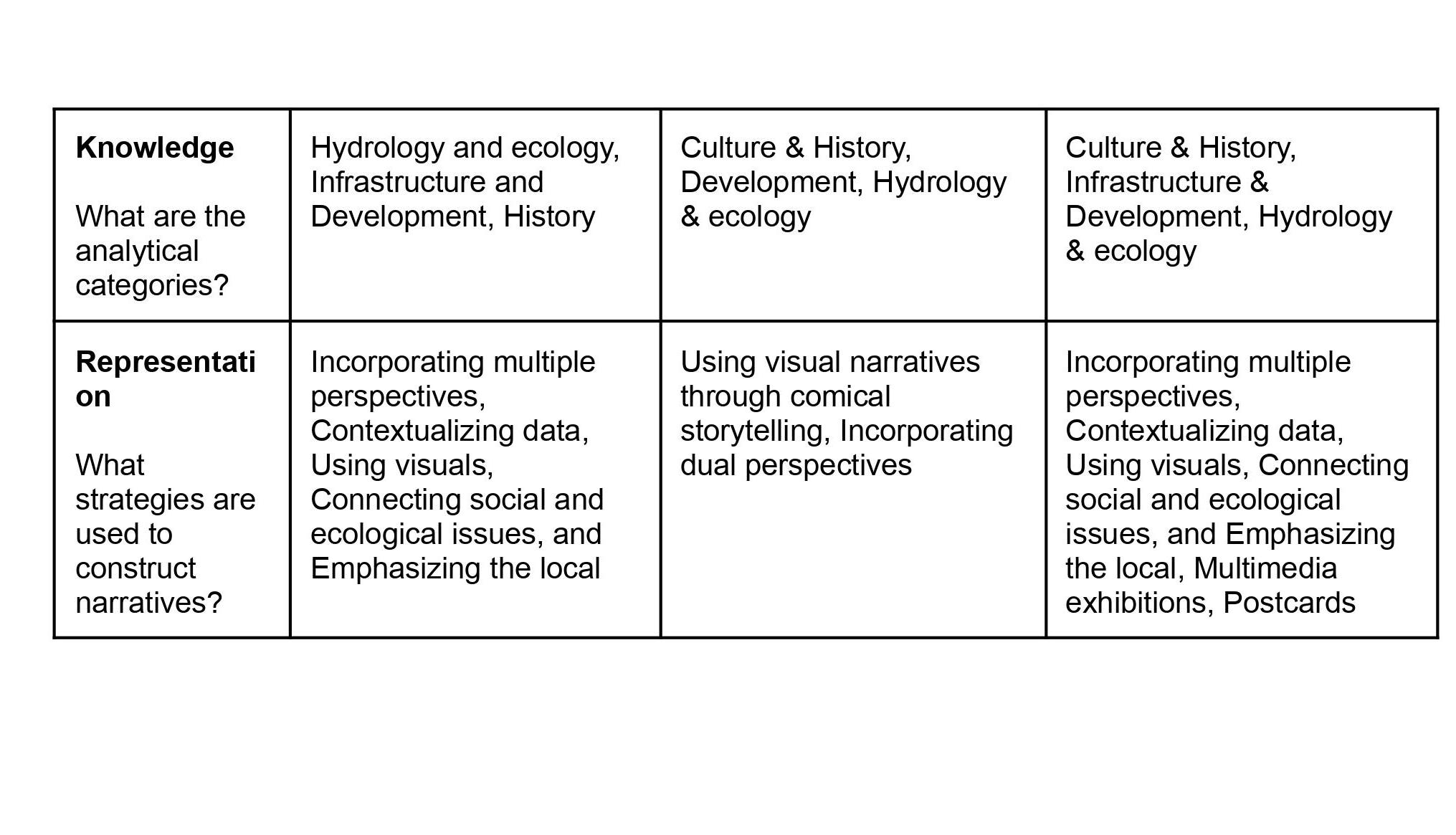

To set up a narrative for the research, it was important to thoroughly understand multiple opinions and perspectives about Mumbai city with respect to its monsoonal wetscapes. Table 2.1 analyzes and compares three such literatures followed by sharp theoretical framework for the thesis.

2.1 Establishing a link

In line with the research approach for the literature review (see Table 2.1.1 Comparison of various literature material to build direction.), Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha’s SOAK : Mumbai in an estuary, Chitra Venkatramani’s talk on Drawing Coastlines and Rohit Mujumdar’s Architectures of Exfoliation, have very similar yet individual profiles, which backs up the validity of the comparison study. In-depth exploration of Mumbai’s wetscapes from a variety of angles is the focus of these investigations. In order to address the issue of Mumbai being perceived as a “island city” rather than an estuary, SOAK explores the complex relationship between Mumbai and its surrounding landscape. Drawing coastlines discusses how various communities perceive the coast, and Architectures of Exfoliation delves into discussions on Mumbai’s teological future by examining various housing typologies and how they react to monsoonal and non-monsoonal wetness.

These sources aided in developing the research’s narrative by offering a wealth of data and in-depth descriptions of the essential components, such as the concern, the research question, the inquiry’s intervention, the research field and data sources, the research approach, the method of recording data, the analytical categories, and the representation or narration of the final data.

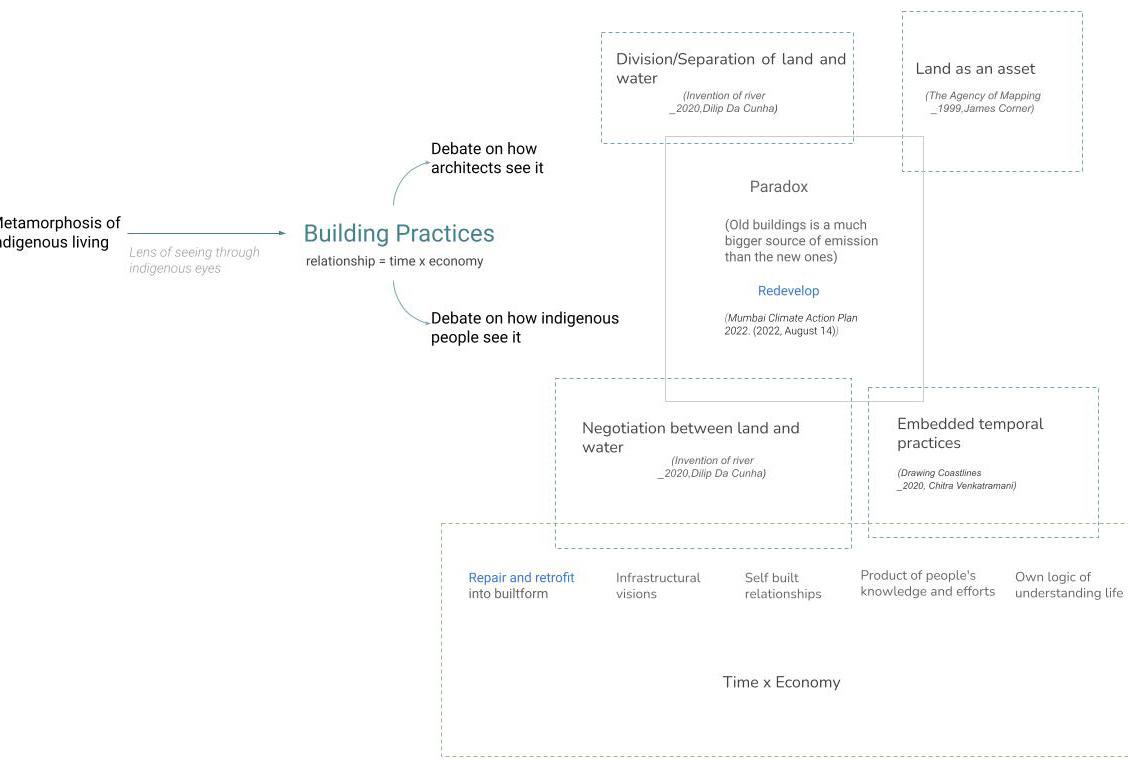

2.2 Building a theoretical framework

The framework (Figure 2.1) is created by drawing conclusions from the literary evaluations, with wetness serving as the key connecting factor between all of the thesis’s components. In spite of whether monsoons occur or not, it discusses how there is always some level of wetness present. The concept of wetness extends ubiquitously rather than being confined to specific locations, challenging the notion of dryness. Even amidst distinctions like monsoon intensifying wetness, its multifaceted presence remains evident. In a world centered around land, water often takes a marginalized role, reminiscent of how structures separate inside from outside. Coastlines emerge as a boundary between land and water, yet paradoxically, wetness permeates everywhere. The essence of wetness is encapsulated by the act of selecting a moment in time, establishing a surface, and delineating a line. The interplay of time, surface, and line enables mapping and colonization of territories creating a need of resilience leading to a land centric approach. This approach comes up with two perspectives; one sees the surface as a division between land and water, emphasizing separation, akin to the architect’s perspective. The other envisions a realm encompassing clouds and aquifers, where rain embodies wetness, and negotiation takes precedence over segregation—this outlook resonates with farmers and fishermen i.e. ‘Indigenous people.’

The central theme of the thesis revolves around exploring the Indigenous perspective on wetness, understanding how these communities perceive it, and examining their strategies for coping with its aftermath. A primary approach that surfaces in this context is the adoption of temporal practices. Indigenous groups exhibit a unique connection to time, employing strategies that emphasize adaptation over time.

At the heart of these strategies lies the concept of repair. For Indigenous communities, repair isn’t just about fixing something that is broken; it encapsulates the idea of restoring harmony and balance within their ecosystems and societies. This restorative approach extends beyond mere physical repairs to encompass the renewal of relationships, both with the environment and among community members. By repairing the damage caused by various factors, they actively engage in the preservation of their cultural heritage and knowledge.

Rebuilding, another facet of their strategy, goes beyond constructing physical structures. It entails the reinvigoration of cultural traditions, social bonds, and ecological equilibrium. The act of rebuilding signifies a commitment to their ancestral wisdom and practices, allowing them to rejuvenate their collective identity while navigating contemporary challenges.

Retrofitting stands out as a particularly crucial aspect of Indigenous strategies. This involves integrating new knowledge and technologies with their existing practices and values. Retrofitting enables these communities to adapt to the evolving circumstances while preserving their heritage. It’s not just about incorporating new elements; it’s about ensuring that these elements align with their holistic worldview and contribute positively to their way of life. By selectively integrating modern tools and ideas, they bolster their resilience and enhance their ability to thrive in an ever-changing world.

In essence, Indigenous approaches to temporal practices—repair, rebuild, and retrofit—redefine resilience and adaptation. They underscore the profound connection between their cultural heritage, the environment, and their strategies for responding to challenges. Through these practices, Indigenous communities display a nuanced understanding of time as a dynamic force, acknowledging the past, responding to the present, and safeguarding the future.

Subsequently, the thesis aims to document and portray the temporal practices of Indigenous communities, focusing on the evolution of their housing and settlements over time—essentially, capturing the transformation referred to as the “Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living.”

3. What is Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living?

‘’Metamorphosis means the transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly. Metamorphosis doesn’t mean eradicating the past, but rather integrating the best of the past into our future,’’ said Vincent Callebaut Architectures.

Metamorphosis means privileging writing a story over another. Metamorphosis means selecting which components of the past will form the foundations of a future still to be imagined. The role of architects extends beyond mere conservation or restoration: it involves advocating for a hybrid history.

~ (Botanic Center Bloom Brussels Urban Renewal | Vincent Callebaut Architectures Arch2O.com, 2021)

The metamorphosis of indigenous living represents a captivating and profound journey of cultural adaptation and resilience across countless generations. Indigenous communities around the world have inhabited diverse ecosystems for centuries, cultivating a deep understanding of their environment and developing sustainable ways of life that harmonize with nature.

Throughout history, these communities have faced numerous challenges, from changing climates and resource constraints to encounters with outside cultures and colonization. Despite these trials, the essence of indigenous living has remained rooted in their profound connection to the land, spiritual beliefs, communal values, and traditional knowledge.

The metamorphosis begins with the indigenous people’s harmonious relationship with nature, utilizing their deep understanding of local ecosystems to harness resources responsibly and maintain ecological balance. Their traditional practices often encompass agroforestry, sustainable hunting, fishing, and organic farming methods, which not only provide for their needs but also foster biodiversity conservation.

Another fundamental aspect of the metamorphosis lies in the preservation of indigenous cultures and traditions. The passing down of oral histories, storytelling, rituals, art, and craftsmanship has ensured the continuity of their unique identities and wisdom across generations. Indigenous languages play a crucial role in maintaining cultural heritage, and efforts to revive and protect these languages further strengthen their resilience.

However, the metamorphosis has not been without challenges. Many indigenous communities have faced forced displacement, loss of land rights, and marginalization from dominant societies. The encroachment of modern technologies, globalization, and consumerism has introduced external influences that may sometimes conflict with their traditional values and practices.

In recent years, there has been an increasing recognition of the value of indigenous knowledge systems in addressing contemporary global challenges, such as climate change, sustainability, and biodiversity conservation. Collaborative efforts between indigenous communities and external entities have emerged, acknowledging the significance of incorporating traditional wisdom into modern practices.

The metamorphosis of indigenous living is an ongoing narrative of resilience, adaptability, and cultural pride. As the world increasingly recognizes the importance of preserving biodiversity, ecosystems, and indigenous knowledge, there is a growing acknowledgment that respecting and learning from these communities can lead to a more sustainable and inclusive future for all. By supporting and empowering indigenous people to maintain their unique ways of life, we enrich the tapestry of human existence and collectively embrace the diverse wisdom that our planet has to offer.

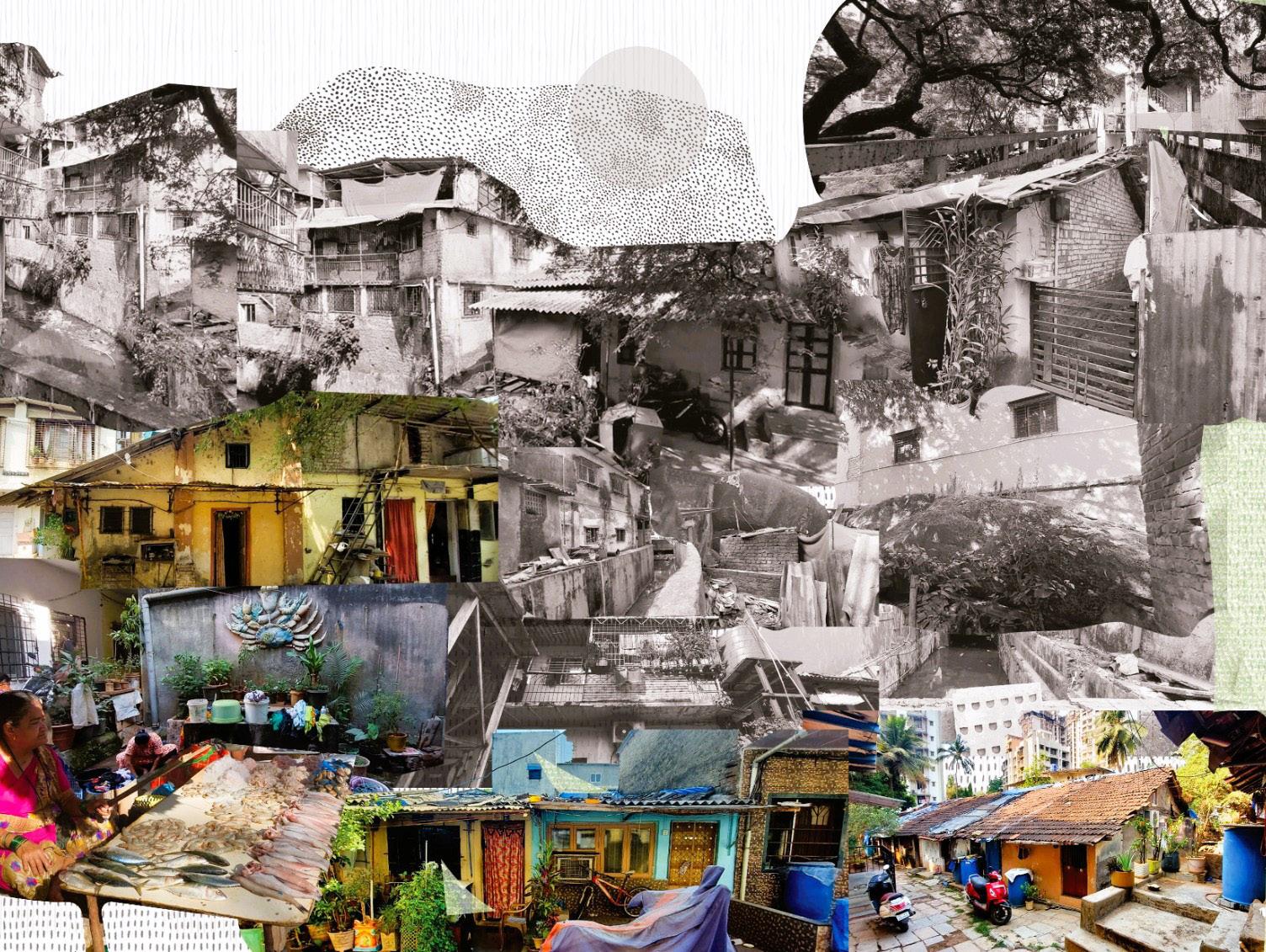

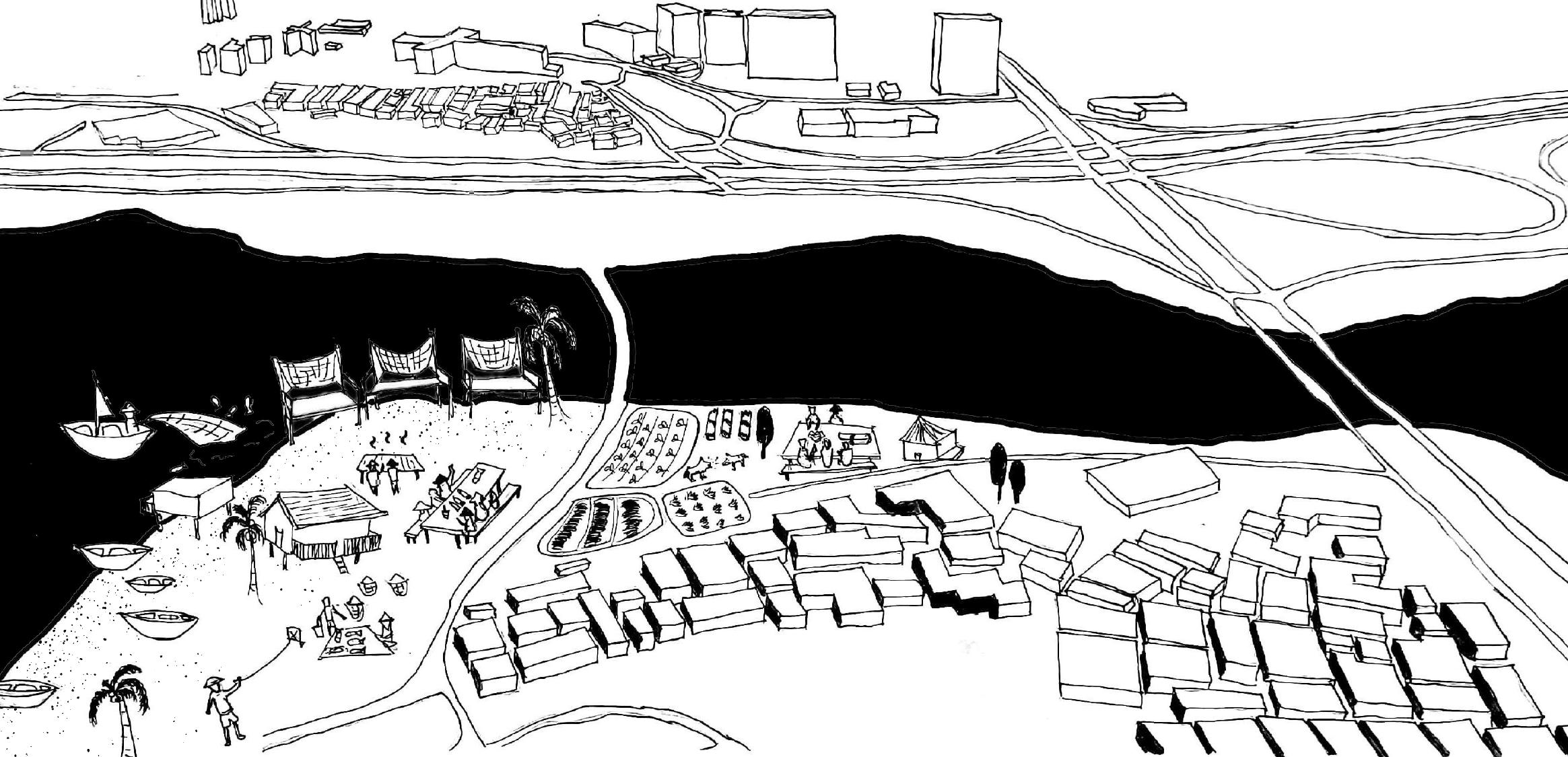

3.1 Building Practices Through Indigenous Eyes

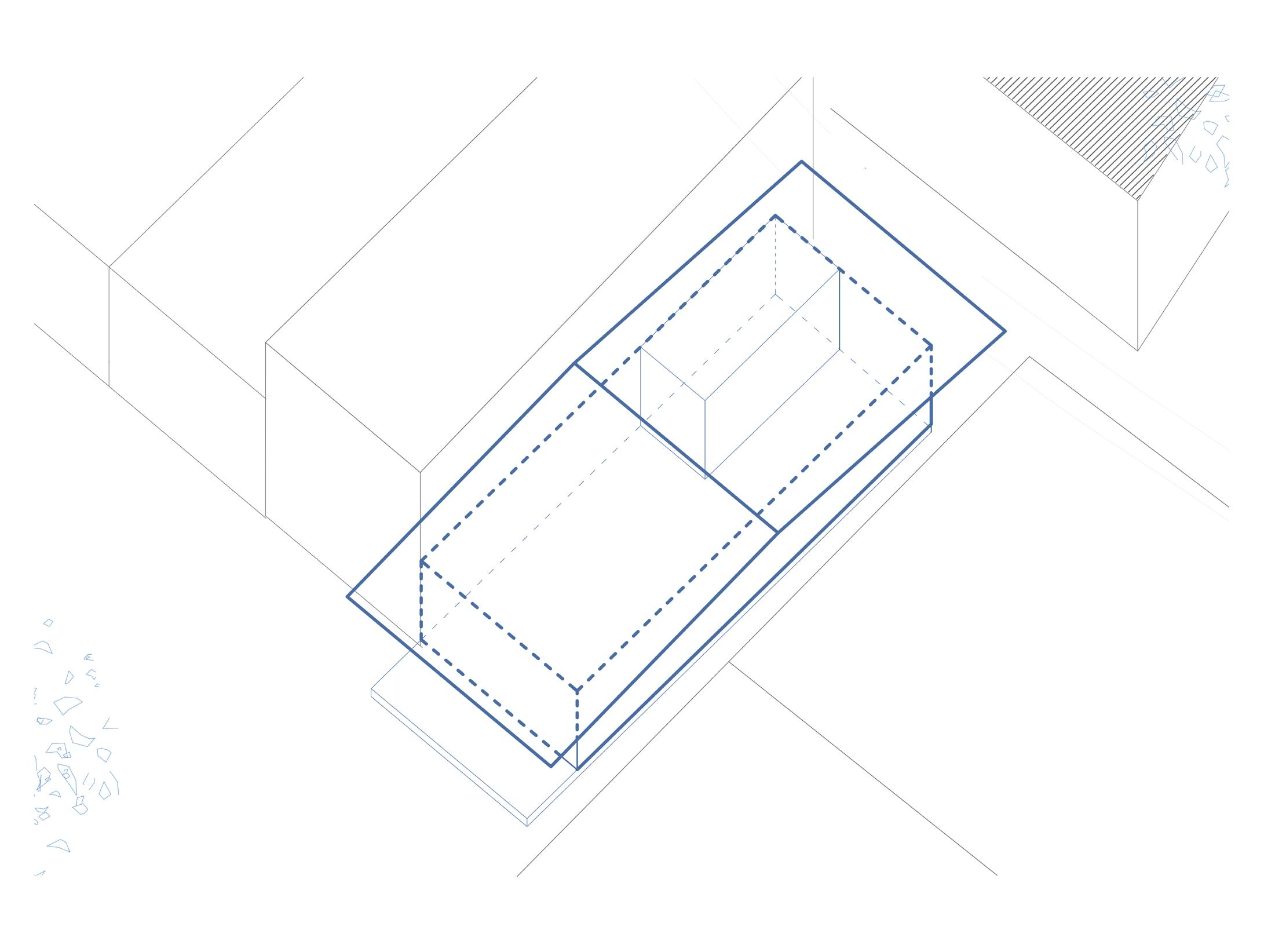

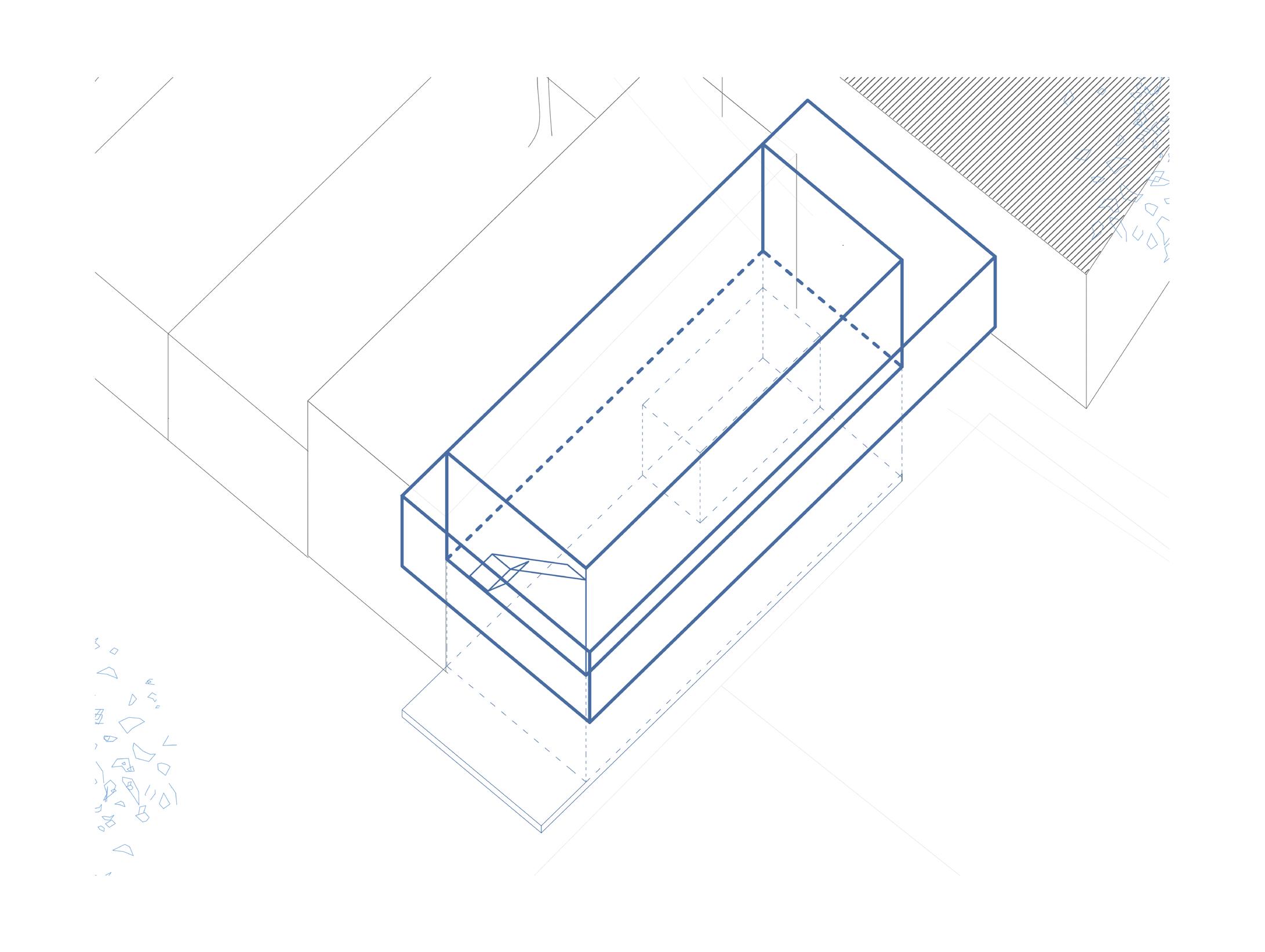

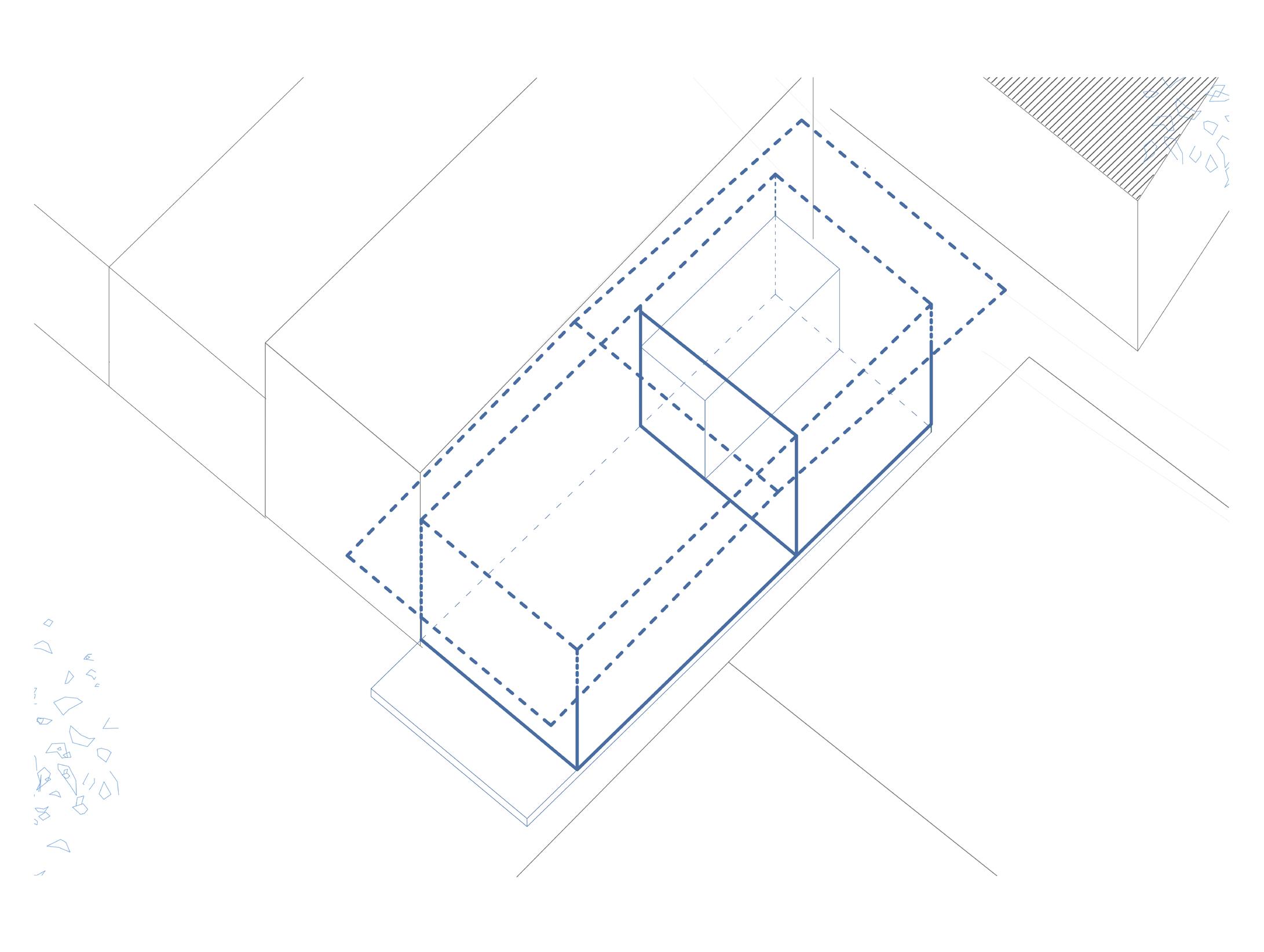

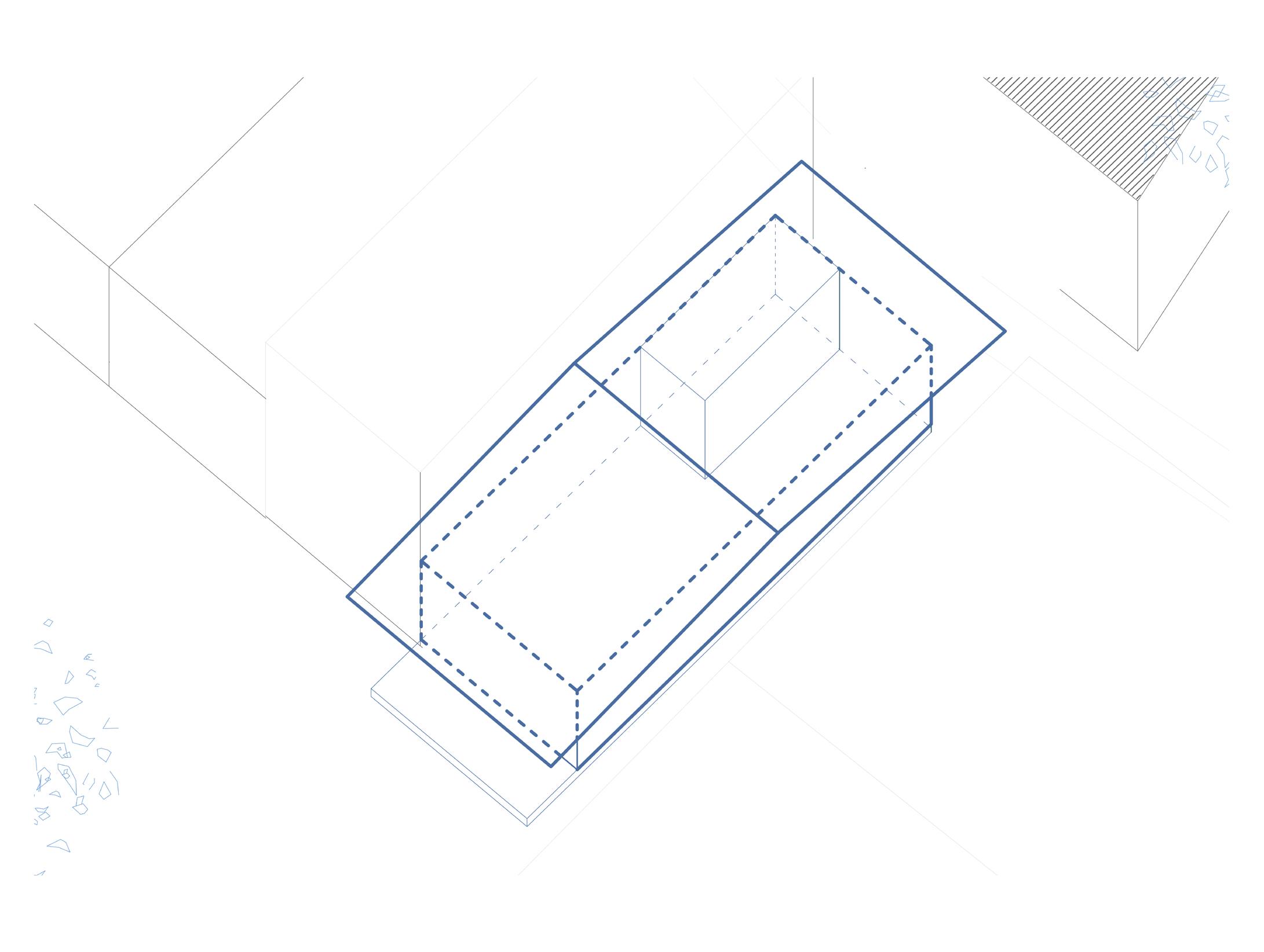

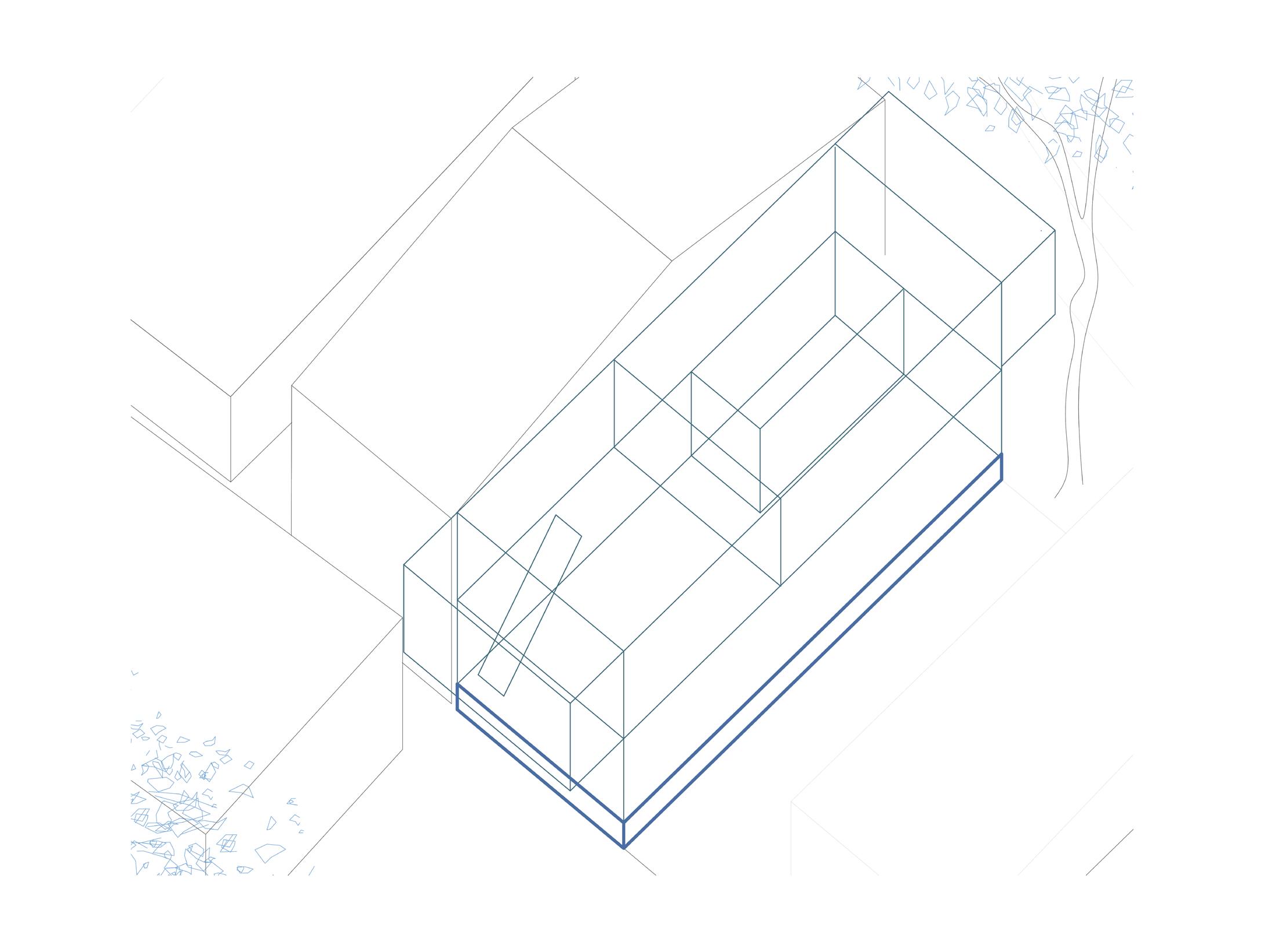

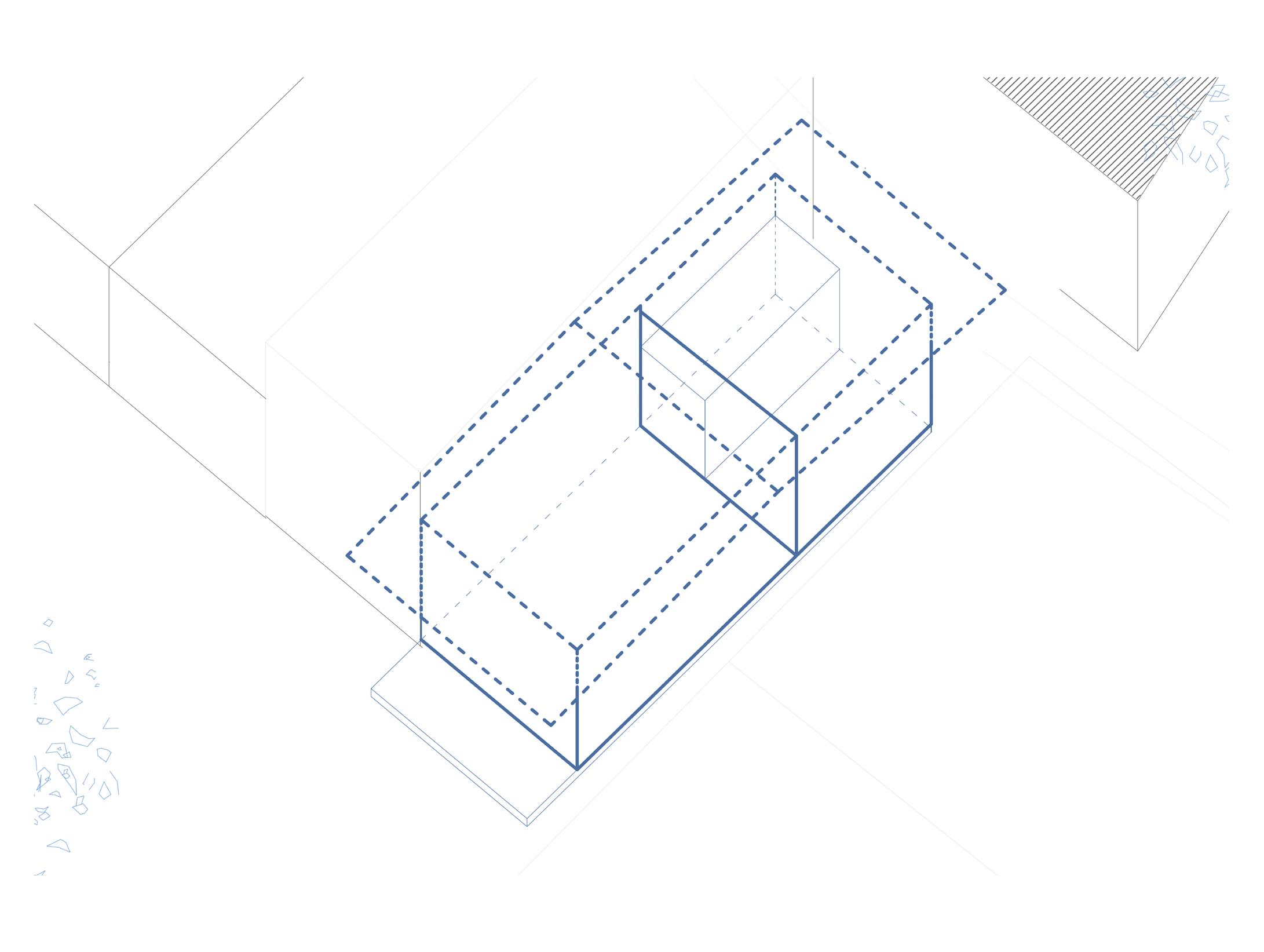

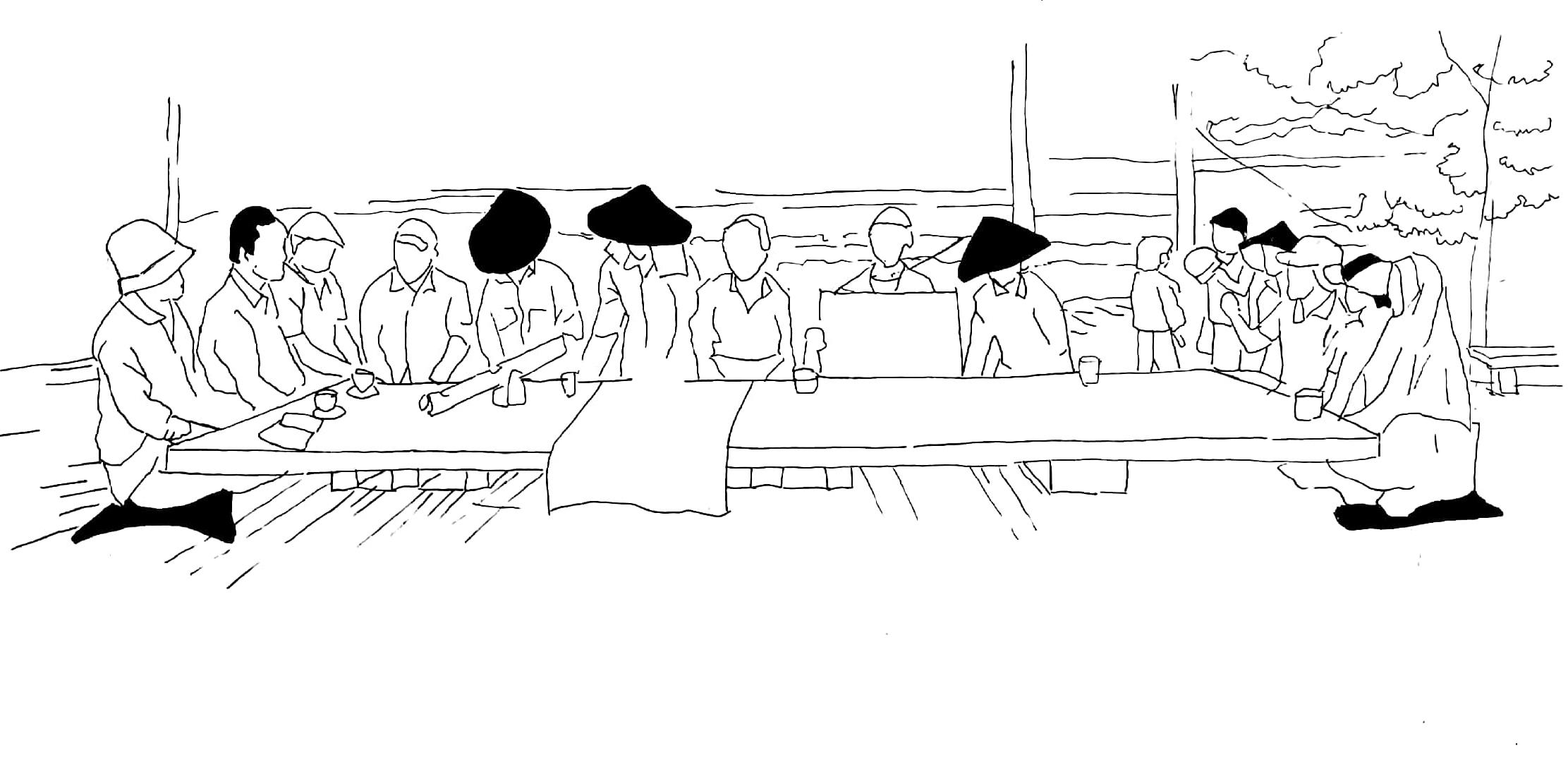

“Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living” takes a unique perspective, immersing itself in the world of Indigenous people within their settlements. Through a captivating series of graphical representations, this project delves deep into the building practices that these communities have developed over generations. However, it goes beyond mere architectural exploration; it engages in meaningful conversations with the Indigenous residents, uncovering their visions, wisdom, and stories. By focusing on graphical representations, this project transcends traditional storytelling. It visually encapsulates the essence of Indigenous building practices, capturing the intricacies of design, material choices, and structural adaptations. These visuals not only showcase the tangible results of their efforts but also mirror the communities’ intimate connection with their environment and their harmonious coexistence with nature.

Through these graphical representations, the project opens dialogues with the Indigenous residents themselves. It invites them to share their stories, beliefs, and traditional knowledge. Their voices resonate through these visuals, revealing how each building choice carries layers of cultural significance, ecological awareness, and resilience. The project’s emphasis on conversations with the Indigenous people creates a bridge between their oral traditions and contemporary expressions. Elders share insights passed down through generations, while younger community members offer innovative perspectives that fuse ancestral wisdom with modern needs. These conversations, depicted visually, paint a holistic picture of Indigenous life, where building practices are intertwined with community identity and wellbeing.

Importantly, this approach recognizes that Indigenous knowledge is not static; it evolves as the community faces new challenges. Climate change, globalization, and urbanization present novel obstacles, compelling these settlements to adapt while staying true to their roots. The graphical series captures these adaptations, underscoring the Indigenous people’s resilience and ingenuity.

In essence, “Metamorphosis of Indigenous Living” celebrates Indigenous architecture as a living testament to a profound relationship between people and place. It encapsulates their ethos, visions, and traditional understandings, weaving them into the fabric of their built environment. Through graphical representations and the voices of the Indigenous inhabitants, the project invites viewers to journey into the heart of these settlements, where building practices encapsulate the metamorphosis of a resilient, adaptive, and culturally rich way of life.