Discovering Diverse Content Through Random Scribd Documents

cup to a reservoir beneath. If you pour water in the cup, it will rise in the shorter leg by its upward pressure, driving out the air before it through the longer leg; and when the cup is filled above the bend of the syphon, (that is, level with the chin of the figure,) the pressure of the water will force it over into the longer leg of the syphon, and the cup will be emptied: the toy thus imitating Tantalus of mythology, who is represented by the poets as punished in Erebus with an insatiable thirst, and placed up to the chin in a pool of water, which, however, flowed away as soon as he attempted to taste it.

IMITATIVE DIVING BELL.

Nearly fill a basin with water, and put upon its surface a floating lighted wick or taper; over this place a glass goblet, mouth downwards, and push it into the water, which will be kept out, whilst the wick will continue to float and burn under the goblet; thus imitating the living inmate of a diving bell, which is merely a larger goblet, with a man instead of a candle within it.

THE WATER-PROOF SIEVE.

Fill a very fine wire-gauze sieve with water, and it will not run through the interstices, but be retained among them by capillary attraction.

MORE THAN FULL.

Fill a glass to the brim with water, and you may add to it spirit of wine without causing the water to overflow, as the spirit will enter into the pores of the water.

TO CAUSE WINE AND WATER TO CHANGE PLACES.

Fill a small narrow-necked bulb with port wine, or with water and coloured spirit of wine, and put the bulb into a tall, narrow glass jar, which is then to be filled up with cold water: immediately, the coloured fluid will issue from the bulb, and accumulate on the surface of the water in the jar, while colourless water will be seen accumulating at the bottom of the bulb. By close inspection, the descending current of the water may also be observed, and the coloured and the colourless liquids be seen to pass each other in the narrow neck of the bulb without mixing.

The whole of the coloured fluid will shortly have ascended, and the bulb will be entirely filled with clear water.

PYRAMID OF ALUM.

Put a lump of alum into a tumbler of water, and, as the alum dissolves, it will assume the shape of a pyramid. The cause of the alum decreasing in this peculiar form is briefly as follows: at first, the water dissolves the alum very fast, but as the alum becomes united with the water, the solvent power of the latter diminishes. The water, which combines first with the alum, becomes heavier by the union, and falls to the bottom of the glass; where it ceases to dissolve any more, although the water which it has displaced from the bottom has risen to the top of the glass, and is there acting upon the alum. When the solution has nearly terminated, if you closely examine the lump, you will find it covered with geometrical figures, cut out, as it were, in relief, upon the mass; showing, not only that the cohesion of the atoms of the alum resists the power of solution in the water, but that, in the present instance, it resists it more in some directions than in others. Indeed this experiment beautifully illustrates the opposite action of cohesion and repulsion.

VISIBLE VIBRATION.

Provide a glass goblet about two-thirds filled with coloured water, draw a fiddle-bow against its edge, and the surface of the water will exhibit a pleasing figure, composed of fans, four, six, or eight in number, dependent on the dimensions of the vessel, but chiefly on the pitch of the note produced.

Or, nearly fill a glass with water, draw the bow strongly against its edge, the water will be elevated and depressed; and, when the vibration has ceased, and the surface of the water has become tranquil, these elevations will be exhibited in the form of a curved line, passing round the interior surface of the glass, and above the surface of the water. If the action of the bow be strong, the water will be sprinkled on the inside of the glass, above the liquid surface, and this sprinkling will show the curved line very perfectly, as in the engraving. The water should be carefully poured, so that the glass above the liquid be preserved dry; the portion of the glass between the edge and the curved line, will then be seen partially sprinkled; but between the level of the water and the curved line, it will have become wholly wetted, thereby indicating the height to which the fluid has been thrown.

CHARCOAL IN SUGAR.

The elements of sugar are carbon and water, as may be proved by the following experiment: Put into a glass a table-spoonful of powdered sugar, and mix it into a thin paste with a little water, and rather more than its bulk of sulphuric acid; stir the mixture together, the sugar will soon blacken, froth up, and shoot like a cauliflower out of the glass: and, during the separation of the charcoal, a large quantity of steam will also be evolved.

FLOATING NEEDLES.

Fill a cup with water, gently lay on its surface small fine needles, and they will float.

WATER IN A SLING.

Half fill a mug with water, place it in a sling, and you may whirl it around you without spilling a drop; for the water tends more away from the centre of motion towards the bottom of the mug, than towards the earth by gravity.

ATTRACTION IN A GLASS OF WATER.

Pour water into a glass tumbler, perfectly dry, and it may be raised above the edge, in a convex form; because the particles of the water have more attraction for each other than for the dry glass; wet the edge, and they will be instantly attracted, and overflow, and the water will sink into a concave form.

TO PREVENT CORK FLOATING IN WATER.

Place at the bottom of a vessel of water, a piece of cork, so smoothly cut that no water gets between its lower surface and the surface of the bottom, when it will not rise, but remain fixed there, because it is pressed downward by the water from above, and there is no pressure from below to counter-balance it.

INSTANTANEOUS FREEZING.

During frosty weather, let a vessel be half filled with water, cover it closely, and place it in the open air, in a situation where it will not experience any commotion: it will thereby frequently acquire a degree of cold more intense than that of ice, without being frozen. If the vessel, however, be agitated ever so little, or receive even a slight blow, the water will immediately freeze with singular rapidity.

The cause of this phenomenon is, that water does not congeal unless its particles unite together, and assume among themselves a new arrangement. The colder the water becomes, the nearer its particles approach each other; and the fluid which keeps it in fusion gradually escapes; but the shaking of the vessel destroys the equilibrium, and the particles fall one upon another, uniting in a mass of ice.

Or, provide a glass full of cold water, and let fall on its surface a few drops of sulphuret of carbon, which will instantly become covered with icy network: feathery branches will then dart from the sulphuret, the whole contents of the glass will become solidified, and the globules will exhibit all the colours of the rainbow.

TO FREEZE WATER WITH ETHER.

Fill a very thin glass tube with water. Close it at one end, and wrap muslin round it: then frequently immerse the tube in strong ether, allowing what the muslin soaks each time to evaporate, and in a short time the water will be frozen.

PRODUCTION OF NITRE.

Dip into the above solution a piece of paper: if its colour be changed to brown, a drop or two more acid must be cautiously applied: if, on the contrary, it reddens litmus paper, a small globule or two of potassium will be required; the object being to obtain a neutral solution: if it then be carefully evaporated to about half its bulk, and set aside, beautiful crystals will begin to form, which will be those of the nitrate of potash, commonly called nitre, or saltpetre.

CURIOUS TRANSPOSITION.

Take a glass of jelly, and place it mouth downward, just under the surface of warm water in a basin: the jelly will soon be dissolved by the heat, and, being heavier than the water, it will sink, while the glass will be filled with water in its stead.

ANIMAL BAROMETER.

Keep one or two leeches in a glass bottle nearly filled with water; tie the mouth over the coarse linen, and change the water every two or three days. The leech may then serve for a barometer, as it will invariably ascend or descend in the water as the weather changes from dry to wet; and it will generally come to the surface prior to a thunder-storm.

MAGIC SOAP.

Pour into a phial a small quantity of oil, with the same of water, and, however violently you shake them, they cannot be mixed, for the water and oil have no affinity for each other; but, if a little ammonia be added, and the phial be then shaken, the whole will be mixed into a liquid soap.

EQUAL PRESSURE OF WATER.

Tie up in a bladder of water, an egg and a piece of very soft wax, and place it in a box, so as to touch its sides and bottom; then, lay loosely upon the bladder a brass or other metal plate, upon which place a hundred pounds weight, or more; when the egg and the wax, though pressed by the water with all its weight, being equally pressed in all directions, will not be in the least either crushed or altered in shape.

TO EMPTY A GLASS UNDER WATER.

Fill a wine-glass with water, place over its mouth a card, so as to prevent the water from escaping, and put the glass, mouth downwards, into a basin of water. Next, remove the card, and raise the glass partly above the surface, but keep its mouth below the surface, so that the glass still remains completely filled with water. Then insert one end of a quill or reed in the water below the mouth of the glass, and blow gently at the other end, when air will ascend in bubbles to the highest part of the glass, and expel the water from it; and, if you continue to blow through the quill, all the water will be emptied from the glass, which will be filled with air.

TO EMPTY A GLASS OF WATER WITHOUT TOUCHING IT.

Hang over the edge of the glass a thick skein of cotton, and the water will slowly be decreased till the glass is empty. A towel will empty a basin of water in the same way.

DECOMPOSITION OF WATER.

The readiest means of decomposing water is as follows: take a gun-barrel, the breech of which has been removed, and fill it with iron wire, coiled up. Place it across a chafing-dish filled with lighted charcoal, and connect to one end of the barrel a small glass retort containing some water; and, to the other, a bent tube, opening under the shelf of a water bath. Heat the barrel red hot, and apply a lamp under the retort: the stream of water, in passing over the redhot iron of the barrel, will be decomposed, the oxygen will unite with the iron, and the hydrogen may be collected in the form of gas at the end of the tube over the water.

WATER HEAVIER THAN WINE.

Let a tumbler be half-filled with water, and fit upon its surface a piece of white paper, upon which pour wine; then carefully draw out the paper, say with a knitting-needle, so as to disturb the liquids as little as possible, and the water, being the heavier, will continue at the lower part of the glass; whilst the wine, being the lighter, will keep above it. But, if a glass be first half-filled with wine, and water be poured over it, it will at once sink through the wine, and both liquids will be mixed.

TO INFLATE A BLADDER WITHOUT AIR.

Put a tea-spoonful of ether into a moistened bladder, the neck of which tie up tightly; pour hot water upon the bladder, and the ether, by expanding, will fill it out.

AIR AND WATER BALLOON.

Procure a small hollow glass vessel, the shape of a balloon, the lower part of which is open, and place it in water, with the mouth downwards, so that the air within prevents the water filling it. Then fill a deep glass jar nearly to the top with water, and place the balloon to float on its surface; tie over the jar with a bladder, so as to confine the air between it and the surface of the water. Press the hand on the bladder, when more water will enter the balloon, and it will soon sink to the bottom of the jar; but, on removing your hand, the balloon will again ascend slowly to the surface.

HEATED AIR BALLOON.

Make a balloon, by pasting together gores of bank post paper; paste the lower ends round a slender hoop, from which proceed several wires, terminating in a kind of basket, sufficiently strong to support a sponge dipped in spirit of wine. When the spirit is set on fire, its combustion will produce a much greater degree of heat than

any ordinary flame: and by thus rarefying the air within the balloon, will enable it to rise with great rapidity, to a considerable height.

THE PNEUMATIC TINDER-BOX.

Provide a small stout brass tube, about six inches long, and half an inch in diameter, closed at one end, and fitted with a hollow airtight piston, containing in its cavity a scrap of amadou, or German tinder. Suddenly drive the piston into the tube by a strong jerk of the hands; and the compression of the air in the tube will give out so much heat as to light the tinder; and upon quickly drawing out the piston, the glowing tinder will kindle a match.

THE BACCHUS EXPERIMENT.

This experiment, showing the elasticity of air, is performed with a pleasing toy. It represents a figure of Bacchus sitting across a cask, in which are two separate compartments. Put into one of them a portion of wine or coloured liquid, and place the apparatus under the exhausted receiver of an air-pump, when the elastic force of the confined air will cause the liquid to ascend a transparent glass tube, (fitted on purpose,) into the mouth of the Bacchanalian figure. To render the experiment more striking, a bladder, with a small quantity of air therein, is fastened around the figure, and covered with a loose silken robe, when the air in the bladder will expand, and produce an apparent increase in the bulk of the figure, as if occasioned by the excess of liquor drunk.

THE MYSTERIOUS CIRCLES.

Cut from a card two discs or circular pieces, about two inches in diameter; in the centre of one of them make a hole, into which put the tube of a common quill, one end being even with the surface of the card. Make the other piece of card a little convex, and lay its

centre over the end of the quill, with the concave side of the card downward; the centre of the upper card being from one-eighth to one-fourth of an inch above the end of the quill. Attempt to blow off the upper card by blowing through the quill, and it will be found impossible.

If, however, the edges of the two pieces of card be made to fit each other very accurately, the upper card will be moved, and sometimes it will be thrown off; but when the edges of the card are on two sides sufficiently far apart to permit the air to escape, the loose card will retain its position, even when the current of air sent against it be strong. The experiment will succeed equally well, whether the current of air be made from the mouth or from a pair of bellows. When the quill fits the card rather loosely, a comparatively light puff of air will throw both cards three or four feet in height. When, from the humidity of the breath, the upper surface of the perforated card has a little expanded, and the two opposite sides are somewhat depressed, these depressed sides may be distinctly seen to rise and approach the upper card, directly in proportion to the force of the current of air.

Another fact to be shown with this simple apparatus, appears equally inexplicable with the former. Lay the loose card upon the hand with the concave side up; blow forcibly through the tube, and, at the same time, bring the two cards towards each other, when, within three-eighths of an inch, if the current of air be strong, the loose card will suddenly rise and adhere to the perforated card. If the card through which the tube passes has several holes made in it, the loose card may be instantly thrown off by a slight puff of air.

For the explanation of the above phenomenon, a gold medal and one hundred guineas were offered, some years since, by the Royal Society. Such explanation has been given by Dr. Robert Hare, of Philadelphia, and is as follows:

Supposing the diameter of the discs of card to be to that of the hole as 8 to 1, the area of the former to the latter, must be as 64 to

1. Hence, if the discs were to be separated, (their surfaces remaining parallel,) with a velocity as great as that of the air blast, a column of air must meanwhile be interposed, sixty-four times greater than that which would escape from the tube during the interim; consequently, if all the air necessary to preserve the balance be supplied from the tube, the discs must be separated with a velocity as much less than that of the blast, as the column required between them is greater than that yielded by the tube, and yet the air cannot be supplied from any other source, unless a deficit of pressure be created between the discs, unfavourable to their separation.

It follows, then, that, under the circumstances in question, the discs cannot be made to move asunder with a velocity greater than one-sixty-fourth of that of the blast. Of course, all the force of the current of air through the tube will be expended on the moveable disc, and the thin ring of air which exists around the orifice between the discs: and, since the moveable disc can only move with onesixty-fourth of the velocity of the blast, the ring of air in the interstice must experience nearly all the force of the jet, and must be driven outwards, the blast following it in various currents, radiating from the common centre of the tube and discs.

PRINCE RUPERT’S DROPS.

Let fall melted glass into cold water, and it will become suddenly cooled and solidified on the outside before the internal part is changed; then, as this part hardens, it is kept extended by the arch of the outside crust: and, if the finely drawn-out point of the drop be broken off, the cohesion of the atoms of the glass is destroyed, and the whole crumbles to dust with a smart explosion.

VEGETABLE HYGROMETER.

The dampness of the air, and the consequent approach of rain, is denoted by several simple means, which are termed hygrometers. Thus, if an ear of the wild oat be hung up, its awn or bristly points will be contracted by a rotatory motion in damp air, and relaxed by a contrary motion when the air is dry. Similar effects are observable on all cordage, string, and every description of twisted material; as the moisture swells the threads, and increases their diameter, but reduces their length; hence, catgut is used in the construction of a weather-house, in which the man and woman foretel wet or dry weather, moving as the catgut stretches or contracts, according as the air is moist or dry.

To prove the moving power of the awn, separate one from the ear, and, holding the base between the finger and thumb, moisten the awn with the lips, when it will be seen to turn round for some time.

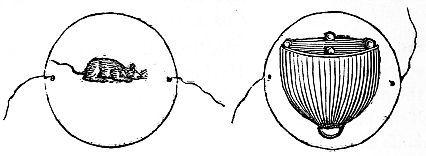

THE PNEUMATIC DANCER.

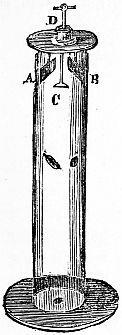

This amusing pneumatic toy consists of a figure made of glass or enamel, and so constructed as to remain suspended in a glass jar of water. An airbubble, communicating with the water, is placed in some part of the figure, shown at m, near the top of the jar, A, in the engraving. At the bottom, B, of the vessel is a bladder, which can be pressed upwards by applying the finger to the extremity of a lever, e o, when the pressure will be communicated through the water to the bubble of air, which is thus compressed. The figure will then sink to the bottom; but, by removing the pressure, the figure will again rise, so that it may be made to dance in the vessel, as if by magic. Fishes, made of glass, are sometimes substituted for the human figure. A common glass jar may be used for this experiment,

in which case the pressure should be applied to the upper surface, which should be a piece of bladder, instead of being placed at the bottom, as shown in the figure engraved.

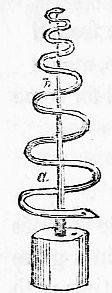

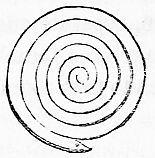

THE ASCENDING SNAKE.

Fig. 2.

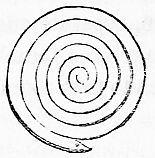

To construct this pretty little pneumatic toy, take a square piece of stiff card, or sheet copper or brass, about two and a half or three inches in diameter, and cut it out spirally, so as to resemble a snake, as in the engraving (fig. 1.). Then paint the body on each side of the card the colours of a snake; take it by the two ends, and draw out the spiral till the distance from head to tail is six or seven inches, as in fig. 2. Next, provide a slender piece of wood on a stand, and fix a sharp needle at its summit; push the rod up through the spiral, and let the end of the spiral rest upon the summit of the needle. Now place the apparatus as nearly as possible to the edge of the mantel-shelf above the fire, and the snake will begin to revolve in the direction of its head; and, if the fire be strong, or the current of heated air which ascends from it is made powerful, by two or three persons coming near it, so as to concentrate the current, the snake will revolve very rapidly. The rod a, b, should be painted, so as to resemble a tree, which the snake will appear to climb; or, the snake may be suspended by a thread from the ceiling, over the current of air from a lamp. Two snakes may be made to turn round in opposite directions, by merely drawing out the spiral of one from the upper side, and of the other from the under side of the figure, and fixing them, of course, on separate rods.

Fig. 1.

THE PNEUMATIC PHIAL.

Provide a phial one-fourth filled with any coloured water, and with a glass tube passing through the cork, or cemented into the neck of the phial, so as to be air-tight; the tube may reach to within a quarter of an inch of the bottom of the phial, so as to dip below the surface of the liquid. Hold this little instrument before the fire, or plunge it into hot water, when the air that is in the phial will expand, and force up the coloured liquor into the tube.

RESIN BUBBLES.

Dip the bowl of a tobacco-pipe into melted resin, hold the pipe in a vertical position, and blow through it; when bubbles of various sizes will be formed, of a brilliant silvery hue, and in a variety of colours.

MOISTURE OF THE ATMOSPHERE.

Moisture is always present in the air, even when it is driest. To prove this, press a piece of sheet copper into the form of a cup; place on it a piece of phosphorus, thoroughly dried between blotting-paper; put the cup on a dry plate, and beside it a small piece of quick-lime; turn over it a glass tumbler, and leave it for ten minutes, that the lime may remove all moisture from the included air; take off the tumbler, touch the phosphorus with a hot wire, and instantly replace the glass; when a dry solid will be formed, resembling snow. As soon as the flame is extinct, examine the plate; when the solid will, in a very short time, attract so much water from the air, that it will pass into small drops of liquid.

CLIMATES OF A ROOM.

The air in a room may be said to resemble two climates: as it is lighter than the external air, a current of colder or heavier air is continually pouring in from the crevices of the windows and doors; and the light air must find some vent, to make way for the heavy air. If the door be set a-jar, and a candle held near the upper part of it, the flame will be blown outwards, showing that there is a current of air flowing out from the upper part of the room; and, if the candle be placed on the floor, close by the door, the flame will bend inwards, showing that there is also a current of air setting into the lower part of the room. The upper current is the warm, light air, which is driven out to make way for the stream of cold, dense air, which enters below.

BUBBLES ON CHAMPAGNE.

Pour out a glass of champagne, or bottled ale, and wait till the effervescence has ceased; you may then renew it by throwing into the liquor a bit of paper, a crumb of bread, or even by violently shaking the glass. The bubbles of carbonic acid chiefly rise from where the liquor is in contact with the glass, and is in greatest abundance at those parts where there are asperities. The bubbles setting out from the surface of the glass are at first very small; but they enlarge in passing through the liquor. It seems as if they proceeded more abundantly from the bottom of the glass than from its sides; but this is an ocular deception.

PROOFS THAT AIR IS A HEAVY FLUID.

Expel the air out of a pair of bellows, then close the nozzle and valve-hole beneath, and considerable force will be requisite to separate the boards from each other. This is caused by the pressure or weight of the atmosphere, which, acting equally upon the upper and lower boards externally, without any air inside, operates like a dead weight in keeping the boards together. In like manner, if you stop the end of a syringe, after its piston-rod has been pressed

down to the bottom, and then attempt to draw it up again, considerable force will be requisite to raise it, depending upon the size of the syringe, being about fourteen or fifteen pounds to every square inch of the piston-rod. When the rod is drawn up, unless it be held, it will fall to the bottom, from the weight of the air pressing it in.

Or, fill a glass tumbler to the brim with water, cover it with a piece of thin wet leather, invert it on a table, and try to pull it straight up, when it will be found to require considerable force. In this manner do snails, periwinkles, limpets, and other shells adhere to rocks, &c. Flies are enabled to walk on the ceiling of a room, up a lookingglass, or window-pane, by the air pressing on the outside of their peculiarly-constructed feet, and thus supporting them.

To the same cause must be attributed the firmness with which the oyster closes itself; for, if you grind off a part of the shell, so as to make a hole in it, though without at all injuring the fish, it may be opened with great ease.

TO SUPPORT A PEA ON AIR.

This experiment may be dexterously performed by placing a pea upon a quill, or the stem of a tobacco-pipe, and blowing upwards through it.

PYROPHORUS, OR AIR-TINDER.

Mix three parts of alum with one of wheat flour, and put them into a common phial; set it in a crucible, up to the neck in sand; then surround the crucible with red-hot coals, when first a black smoke, and next a blue sulphureous flame, will issue from the mouth of the phial; when this flame disappears, remove the crucible from the fire, and when cold, stop the phial with a good cork. If a portion of this powder be exposed to the air, it will take fire.

Or, a very perfect and beautiful pyrophorus may be obtained by heating tartrate of lead in a glass tube, over a lamp. When some of the dark brown mass thus formed is shaken out in the air, it will immediately inflame, and brilliant globules of lead cover the ignited surface.

Or, mix three parts of lamp-black, four of burnt alum, in powder, and eight of pearl-ash, and heat them for an hour, to a bright cherry red, in an iron tube. When well made, and poured out upon a glass plate or tile, this pyrophorus will kindle, with a series of small explosions, somewhat like those produced by throwing potassium upon water; but this effect should be witnessed from a distance.

Put a small piece of grey cast-iron into strong nitric acid, when a porous, spongy substance will be left untouched, and will be of a dark grey colour, resembling plumbago. If some of this be put upon blotting paper, in the course of a minute it will spontaneously heat and smoke; and, if a considerable quantity be heaped together, it will ignite and scorch the paper; nor will the properties of this pyrophorus be destroyed by its being left for days and weeks in water.

BEAUTY OF A SOAP BUBBLE.

Blow a soap bubble, cover it with a clean glass to protect it from the air, and you may observe, after it has grown thin by standing a little, several rings of different colours within each other round the top of it. The colour in the centre of the rings will vary with the thickness; but, as the bubble grows thinner, the rings will spread, the central spot will become white, then bluish, and then black; after which the bubble will burst, from its extreme tenuity at the black spot, where the thickness has been proved not to exceed the 2,500,000th part of an inch.

WHY A GUINEA FALLS MORE QUICKLY THAN A FEATHER THROUGH THE AIR.

The resistance of the air to fallen bodies is not proportioned to the weight, but depends on the surface which the body opposes to the air. Now, the feather exposes, in proportion to its weight, a much greater surface to the air than a piece of gold does, and therefore suffers a much greater resistance to its descent. Were the guinea beaten to the thinness of gold-leaf, it would be as long, or even longer in falling than the feather; but, let both fall in a vacuum, or under the receiver of an air-pump, from which the air has been pumped out, and they will both reach the bottom at the same time; for gravity, acting independently of other forces, causes all bodies to descend with the same velocity.

An apparatus for performing this experiment is shown in the engraving: the coin and the feather are to be laid together, on the brass flap, A or B: this may be let down by turning the wire, C, which passes through a collar of leather, D, placed in the head of the receiver.

SOLIDITY OF AIR.

Provide a glass tube, open at each end; close the upper end by the finger, and immerse the lower one in a glass of water, when it will be seen that the air is material, and occupies its own space in the tube, for it will not permit the water to enter it until the finger is removed, when the air will escape, and the water rise to the same level in the inside as on the outside of the tube.

BREATHING AND SMELLING.

Hold the breath, and place the open neck of a phial, containing oil of peppermint, or any other essential oil, in the mouth, and the smell will not be perceived; but, after expiration, it will be easily recognised.

HE chief requisites for success in the performance of feats of Magic are manual dexterity and selfpossession. The former can only be acquired by practice; the latter will be the natural result of a well-grounded confidence. We subjoin a few preliminary hints, of considerable importance to the amateur exhibiter.

1. Never acquaint the company before-hand with the particulars of the feat you are about to perform, as it will give them time to discover your mode of operation.

2. Endeavour, as much as possible, to acquire various methods of performing the same feat, in order that if you should be likely to fail in one, or have reason to believe that your operations are suspected, you may be prepared with another.

3. Never venture on a feat requiring manual dexterity, till you have previously practised it so often as to acquire the necessary expertness.

4. As diverting the attention of the company from too closely inspecting your manœuvres is a most important object, you should manage to talk to them during the whole course of your proceedings. It is the plan of vulgar operators to gabble unintelligible jargon, and attribute their feats to some extraordinary and mysterious influence. There are few persons at the present day credulous enough to believe such trash, even among the rustic and most ignorant; but as the youth of maturer years might inadvertently be tempted to pursue this method, while exhibiting his skill before his younger companions, it may not be deemed superfluous to offer a caution against such a procedure. He may state, and truly, that every thing he exhibits can be accounted for on rational principles, and is only in obedience to the unerring laws of Nature; and although we have just cautioned him against enabling the company themselves to detect his operations, there can be no objection (particularly when the party comprises many younger than himself) to occasionally show by what simple means the most apparently marvellous feats are accomplished.

THE RING AND THE HANDKERCHIEF.

This may be justly considered one of the most surprising sleights; and yet it is so easy of performance, that any one may accomplish it after a few minutes’ practice.

You previously provide yourself with a piece of brass wire, pointed at both ends, and bent round so as to form a ring, about the size of a wedding-ring. This you conceal in your hand. You then commence your performance by borrowing a silk pocket handkerchief from a gentleman, and a wedding-ring from a lady; and you request one person to hold two of the corners of the handkerchief, and another to hold the other two, and to keep them at full stretch. You next

exhibit the wedding-ring to the company, and announce that you will make it appear to pass through the handkerchief. You then place your hand under the handkerchief, and substituting the false ring, which you had previously concealed, press it against the centre of the handkerchief, and desire a third person to take hold of the ring through the handkerchief, and to close his finger and thumb through the hollow of the ring. The handkerchief is held in this manner for the purpose of showing that the ring has not been placed within a fold. You now desire the persons holding the corners of the handkerchief to let them drop; the person holding the ring (through the handkerchief as already described) still retaining his hold.

Let another person now grasp the handkerchief as tight as he pleases, three or four inches below the ring, and tell the person holding the ring to let it go, when it will appear to the company that the ring is secure within the centre of the handkerchief. You then tell the person who grasps the handkerchief to hold a hat over it, and passing your hand underneath, you open the false ring, by bending one of its points a little aside, and bringing one point gently through the handkerchief, you easily draw out the remainder; being careful to rub the hole you have made in the handkerchief with your finger and thumb, to conceal the fracture.

You then put the wedding-ring you borrowed over the outside of the middle of the handkerchief, and desiring the person who holds the hat, to take it away, you exhibit the ring (placed as described) to the company.

THE KNOTTED HANDKERCHIEF.

This feat consists in tying a number of hard knots in a pocket handkerchief borrowed from one of the company, then letting any person hold the knots, and by the operator merely shaking the handkerchief, all the knots become unloosed, and the handkerchief is restored to its original state.

To perform this excellent trick, get as soft a handkerchief as possible, and taking the opposite ends, one in each hand, throw the right hand over the left, and draw it through, as if you were going to tie a knot in the usual way. Again throw the right-hand end over the left, and give the left-hand end to some person to pull, you at the same time pulling the right-hand end with your right hand, while your left hand holds the handkerchief just behind the knot. Press the thumb of your left hand against the knot to prevent its slipping, always taking care to let the person to whom you gave one end pull first, so that, in fact, he is only pulling against your lefthand.

You now tie another knot exactly in the same way as the first, taking care always to throw the right-hand end over the left. As you go on tying the knots, you will find the right-hand end of the handkerchief decreasing considerably in length, while the left-hand one remains nearly as long as at first; because, in fact, you are merely tying the right-hand end roundtheleft. To prevent this from being noticed, you should stoop down a little after each knot, and pretend to pull the knots tighter; while, at the same time, you press the thumb of the right hand against the knot, and with the fingers and palm of the same hand, draw the handkerchief, so as to make the left-hand end shorter, keeping it at each knot as nearly the length of the right-hand end as possible.

When you have tied as many knots as the handkerchief will admit of, hand them round for the company to feel that they are firm knots; then hold the handkerchief in your right hand, just below the knots, and with the left hand turn the loose part of the centre of the handkerchief over them, desiring some person to hold them. Before they take the handkerchief in hand, you draw out the right-hand end of the handkerchief, which you have in the right hand, and which you may easily do, and the knots being still held together by the loose part of the handkerchief, the person who holds the handkerchief will declare he feels them: you then take hold of one of the ends of the handkerchief which hangs down, and desire him to repeat after you, one—two—three,—then tell him to let go, when, by

giving the handkerchief a smart shake, the whole of the knots will become unloosed.

Should you, by accident, whilst tying the knots, give the wrong end to be pulled, a hard knot will be the consequence, and you will know when this has happened the instant you try to draw the lefthand end of the handkerchief shorter. You must, therefore, turn this mistake to the best advantage, by asking any one of the company to see how long it will take him to untie one knot, you counting the seconds. When he has untied the knot, your other knots will remain right as they were before. Having finished tying the knots, let the same person hold them, and tell him that as he took two minutes to untie one knot, he ought to allow you fourteen minutes to untie the seven; but as you do not wish to take any advantage, you will be satisfied with fourteen seconds.

You may excite some laughter during the performance of this trick, by going to the owner of the handkerchief, and desiring him to assist you in pulling a knot, saying, that if the handkerchief is to be torn, it is only right that he should have a share of it; you may likewise say that he does not pull very hard, which will cause a laugh against him.

THE INVISIBLE SPRINGS.

Take two pieces of white cotton cord, precisely alike in length; double each of them separately, so that their ends meet; then tie them together very neatly, with a bit of fine cotton thread, at the part where they double (i. e. the middle). This must all be done beforehand.

When you are about to exhibit the sleight, hand round two other pieces of cord, exactly similar in length and appearance to those which you have prepared, but not tied, and desire your company to examine them. You then return to your table, placing these cords at the edge, so that they fall (apparently accidentally) to the ground

behind the table; stoop to pick them up, but take up the prepared ones instead, which you have previously placed there, and lay them on the table.

Having proceeded thus far, you take round for examination three ivory rings; those given to children when teething, and which may be bought at any of the toyshops, are the best for your purpose. When the rings have undergone a sufficient scrutiny, pass the prepared double cords through them, and give the two ends of one cord to one person to hold, and the two ends of the other to another. Do not let them pull hard, or the thread will break, and your trick be discovered. Request the two persons to approach each other, and desire each to give you one end of the cord which he holds, leaving to him the choice. You then say, that, to make all fast, you will tie these two ends together, which you do, bringing the knot down so as to touch the rings; and returning to each person the end of the cord next to him, you state that this trick is performed by the rule of contrary, and that when you desire them to pull hard, they are to slacken, and vice versâ, which is likely to create much laughter, as they are certain of making many mistakes at first.

During this time, you are holding the rings on the fore-finger of each hand, and with the other fingers preventing your assistants from separating the cords prematurely, during their mistakes; you at length desire them, in a loud voice, to slacken, when they will pull hard, which will break the thread, the rings remaining in your hands, whilst the strings will remain unbroken: let them be again examined, and desire them to look for the springs in the rings.

THE MIRACULOUS APPLE.

To divide an apple into several parts, without breaking the rind:— Pass a needle and thread under the rind of the apple, which is easily done by putting the needle in again at the same hole it came out of; and so passing on till you have gone round the apple. Then take both ends of the thread in your hands and draw it out; by which

means the apple will be divided into two parts. In the same manner, you may divide it into as many parts as you please, and yet the rind will remain entire. Present the apple to any one to peel, and it will immediately fall to pieces.

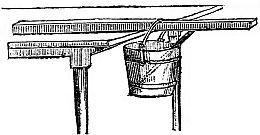

THE SELF-BALANCED PAIL.

You lay a stick across the table, letting one-third of it project over the edge; and you undertake to hang a pail of water on it, without either fastening the stick on the table, or letting the pail rest on any support; and this feat, the laws of gravitation will enable you literally to accomplish.

You take the pail of water, and hang it by the handle upon the projecting end of the stick, in such a manner that the handle may rest on it in an inclined position, with the middle of the pail within the edge of the table. That it may be fixed in this situation, place another stick with one of its ends resting against the side at the bottom of the pail, and its other end against the first stick, where there should be a notch to retain it. By these means, the pail will remain fixed in that situation, without being able to incline to either side; nor can the stick slide along the table, or move along its edge, without raising the centre of gravity of the pail, and the water it contains.

THE PHANTOM AT COMMAND.

This feat is performed by means of confederacy.—Having privately apprised your confederate that when he hears you strike one blow, it signifies the letter A; when you strike two, it means B; and so on for the rest of the alphabet, you state to the company, that if any one

will walk into the adjoining room, and have the door locked upon him, perhaps the animal may appear to him which another person may name.

In order to deter every one except your confederate from accepting the offer, you announce at the same time, that the person who volunteers to be shut up in the room must be possessed of considerable courage, or he had better not undertake it. Having thus gained your end, you give your confederate a lamp, which burns with a very dismal light; telling him, in the hearing of the company, to place it on the middle of the floor, and not to feel alarmed at what he may happen to see. You then usher him into the room, and lock the door.

You next take a piece of black paper, and a bit of chalk, and giving them to one of the party, you tell him to write the name of any animal he wishes to appear to the person shut up in the room. This being done, you receive back the paper, and after showing it round to the company, you fold it up, burn it in the candle, or lamp, and throw the ashes into a mortar; casting in at the same time a powder, which you state to be possessed of valuable properties.

Having taken care to read what was written, you proceed to pound the ashes in the mortar thus: Suppose the word written to be CAT, you begin by stirring the pestle round the mortar several times, and then strike three distinct blows, loud enough for the confederate to hear, and by which he knows that the first letter of the word is C. You next make some irregular evolutions of the pestle round the mortar, that it may not appear to the company that you give nothing but blows, and you then strike one blow to denote A. Work the pestle about again, and then strike twenty blows, which he will know to mean T; finishing your manœuvre by working the pestle about the mortar, the object being to make the blows as little remarkable as possible. You then call aloud to your confederate, and ask him what he sees. At first he is to make no reply. At length, after being interrogated several times, he asks if it be a CAT.

That no mistake may be made, each party should repeat to himself the letters of the alphabet in the order of the blows.

THE MIRACULOUS SHILLING.

Provide a round box, the size of a large snuff-box, and likewise eight other boxes, which will go easily into each other, letting the least of them be of the size to hold a shilling. Observe that all these boxes must shut so freely that they may all be closed at once, by the covers accurately fitting within each other.

Previously to commencing your performance, fit the boxes within each other, and place them in a table drawer at another part of the room. You also fit the covers in the same manner, and lay them by the side of the boxes; you likewise provide a silk handkerchief, into one corner of which a shilling is sewed.

You now commence your operations, by borrowing a shilling, desiring the lender to mark it, that it may not be changed. Take this shilling in your right hand, and the handkerchief in your left, pretending to place the shilling in the centre of the handkerchief; instead of which, you put the corner of the handkerchief in which a shilling was sewed, as previously described, concealing the borrowed shilling in your right hand. You then desire the person to feel that the shilling is there, and tell him to hold it tight.

You now go to the drawer, and placing the borrowed shilling in the smallest of the boxes, you put on all the covers, by taking them in the centre between the fore-finger and thumb, to prevent their separation, and fit them on, by carefully sliding them along, and then pressing them down.

Having thus closed your boxes, you produce what appears to be a single box, and lay it on the table. You now ask the person, who still retains his hold of the shilling in the handkerchief, if he is sure that it is there. He will reply in the affirmative; you then request him to allow you to take the handkerchief, and having done so, you strike

that part of the handkerchief containing the shilling on the box, and immediately shake out the handkerchief, holding it by two corners, and shifting it round so as to get the shilling within your grasp: it will thus appear that the shilling is no longer there. You desire the person to open the box, and hand it round, till the shilling be found; and when the last box is opened, and the shilling taken out, you ask the lender to state whether it is the one which he marked; to which he must, of course, reply in the affirmative.

THE LOCOMOTIVE SHILLING.

Privately place a shilling, which you previously mark on the head side with a cross, under a candlestick, or in any other out-of-the-way situation, where it is not likely to be discovered. You next borrow a shilling of one of the company, and say: “Now I am going to show you a trick with this shilling, but that you may know it again, I will mark it.” Then take your penknife, and cross it in the same manner as the one you have concealed; show it to the person who lent it to you, and ask him if he will know it again. He will reply: “Yes; it is marked with a cross.” Knock under the table, and say “Presto! fly quickly!” at the same time, adroitly conveying the shilling into your pocket. You then tell the spectators that it is gone; but you have a strong notion that if they look they will find it under the candlestick, (or whatever other place you may have concealed it in,) where the first shilling you marked will of course be found, and having the same marks as the genuine one will be mistaken for it.

THE PENETRATIVE SIXPENCE.

You profess that you will make a sixpence appear to pass through the table. To perform this feat, you must have a handkerchief, in one corner of which is sewed a sixpence. Take it out of your pocket, and ask one of the company to lend you a sixpence, which you must seem to carefully wrap up in the middle of the handkerchief, but instead of which, you keep it in the palm of your hand, and in its

stead, wrap up the corner in which the other sixpence is sewed, in the midst of the handkerchief, and bid the person from whom you borrowed the sixpence, feel that it is there. You then lay it under a hat upon the table, take a glass in the hand in which you have concealed the sixpence, and hold it under the table. Give three knocks upon the table, crying “Presto! come quickly!” Then drop the sixpence into the glass; bring the glass from under the table, and exhibit the sixpence to the spectators. You lastly take the handkerchief from under the hat, and shake it, taking care to hold it by the corner in which the sixpence was sewed.

THE VANISHING SIXPENCE.

Having previously stuck a small piece of white wax on the nail of your middle finger, lay a sixpence on the palm of your hand, and addressing the company, state that it will vanish at the word of command. “Many persons,” you observe, “perform this feat, by letting the sixpence fall into their sleeve; but to convince you that I shall not have recourse to any such deception, I will turn up my cuffs.” You then close your hand, and bringing the waxed nail in contact with the sixpence, it will firmly adhere to it. You then blow your hand, and cry “Begone!” and suddenly opening it, and exhibiting the palm, you show that the sixpence has vanished. If you borrow the sixpence of any of the company, take care to rub off the wax, before you restore it to the owner.

TO MAKE A SIXPENCE BALANCE AND SPIN ON ITS EDGE, ON THE POINT OF A NEEDLE.

Procure a common wine-bottle, two forks, two corks, a needle, a sixpence, and a penknife. Having corked the bottle, force the eye of the needle into the cork perpendicularly, leaving more than half the needle sticking up. You next cut a small slit with the penknife in the centre of the bottom of the second cork, into which you insert the

sixpence edgewise; then stick the forks into the upper cork, and, with a steady hand, place the edge of the sixpence on the point of the needle, and it will immediately find its balance. You may now take the upper cork between the finger and thumb, and spin it round as fast as you please, as the sixpence will not fall off. When it goes slow, hit one of the forks with your finger as it goes round, to increase its velocity.

THE MULTIPLYING COIN.

Let a tumbler be half-filled with water; put a sixpence in it; and holding a plate over the top, turn the glass upside down. The sixpence will fall down on the plate, and appear to be a shilling; while at the same time a sixpence will seem to be swimming in the water. If a shilling is put in the glass, it will have the appearance of a quarter of a dollar and a shilling; and if a quarter of a dollar were put in, it would seem to be half a dollar and a quarter of a dollar.

MAGIC RAT TRAP.

Prepare a pasteboard circle, upon one side of which draw a figure of a cage, and on the other side that of a rat. Near the outer edge of the circle fasten two strings opposite each other. So that they may be held between the fore finger and thumb in such manner that the circle may be made to revolve rapidly. When it is set in motion the transition is so quick, that it presents the appearance of a rat in the cage.

Welcome to our website – the perfect destination for book lovers and knowledge seekers. We believe that every book holds a new world, offering opportunities for learning, discovery, and personal growth. That’s why we are dedicated to bringing you a diverse collection of books, ranging from classic literature and specialized publications to self-development guides and children's books.

More than just a book-buying platform, we strive to be a bridge connecting you with timeless cultural and intellectual values. With an elegant, user-friendly interface and a smart search system, you can quickly find the books that best suit your interests. Additionally, our special promotions and home delivery services help you save time and fully enjoy the joy of reading.

Join us on a journey of knowledge exploration, passion nurturing, and personal growth every day!