THE LEADING SURFACE OF TRACK & FIELD

FULL CONTROL ON QUALITY

Beynon controls all aspects of the manufacturing value chain. From start to finish, your project doesn’t leave our hands.

PROVEN DURABILITY

Manufactured and installed with the highest attention to detail, Beynon systems showcase proven durability.

TRUSTED

For indoor or outdoor venues, Beynon is the trusted surface of leading NCAA Div I programs, thousands of high schools and distinguished municipal facilities.

FINANCIALLY STRONG

Part of Tarkett Sports, a division of the Tarkett Group, a worldwide leader of innovative flooring and sports surface solutions, Beynon has unprecedented financial support and stability. You can rest easy.

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, OH

IF THE ATHLETE...

Takes off too close to the bar

Takes off too far from the bar

Is at the right distance for take-off, but the turn is too narrow

Is at the right distance for take-off, but the turn is too wide

Takes off too close to the middle of the bar

Takes off too close to the standard

session. I believe it’s generally safer for the athlete to be a little bit out on the take-off during the early part of the session because this allows the athlete to bail on their attempt more safely. From that baseline, use your observations. As noted earlier, factors like cold weather or fatigue may require moving the mark inward (forward) immediately, while a well-rested athlete on a warm day may hold their previous distance. This is where knowing your athlete counts! Trust your coaching eye and adjust the environment to fit the day.

I like using a 4-stride pop-up drill to adjust the approach and help athletes become comfortable with turn and take-off. No bar or bungee is needed for this drill. Instruct your athlete to run two strides down linearly from their starting mark. From this point in the approach they will begin the turn and run two more strides along a curve. Then, at take-off, they will jump into a triple extension position and land on their feet on the mat. No flop, no scissors—just a popup. The 4-stride pop-up allows you to make adjustments based on stride length and turn width, but you can also correct running posture, trunk lean, and foot strike at take-off.

There’s one last problem with the turn— the geometric discrepancy between a calculated arc and a measured line. In my quest for developing a better coaching methodology for the approach, I have found that mathematical precision is no substitute for athletic consistency. When we compare the path length of a precisely “mapped” turn to the empirical estimation used in this methodology, the difference is minute. We’re talking about maybe a foot, which is still negligible compared to the natural variation of a starting mark within a given practice.

We do not need a protractor to solve a problem that a developed coaching eye and a 6-inch adjustment can fix in real-time. By estimating the initial arc and immediately moving into the 4-stride pop-up, we allow

THEN, MAKE THIS ADJUSTMENT:

Move the starting mark backward, away from the bar.

Move the starting mark forward, closer to the bar.

Widen the turn and move the starting mark forward 6 inches.

Narrow the turn and move the starting mark back 6 inches.

Move the starting mark outward 6-12 inches, depending on observation.

Move the starting mark inward 6-12 inches, depending on observation.

the athlete’s own execution to prompt our adjustment. We know the stride length will elongate as practice progresses from the warmup to the middle of the session. We catch the steps, observe the rhythm, and adjust the environment to fit the athlete.

PART 3 - CORRECTIONS VS. ADJUSTMENTS

As a coach, you have two tools for feedback: Corrections and Adjustments. Corrections are internal. They require the athlete to change their mechanics (e.g., “Stay tall,” or “Heel strike below the hip”). Adjustments are external. They acknowledge that the athlete’s movement is successful, but the environment (the starting mark) must change to accommodate it. If the athlete’s mechanics are sound but the take-off is off, use these adjustments (starting with 6-inch increments): See chart above

Don’t overcomplicate it. Apply one adjustment at a time. As an athlete matures and their speed increases, their stride will naturally open up. Do not fight this. I have seen too many talented jumpers foul out or clip the bar because their coach refused to move a mark. Avoid being too tight at take-off. Avoid being too far out. Make the adjustment.

As you develop a keen eye for the approach, you may begin combining adjustments and/or corrections. Typically, 6 inches is a good distance for an adjustment, but it’s your observations that matter most. Intermediate or advanced athletes generally require larger adjustments, like a full foot or more.

PART 4 - BALANCING GEOMETRY WITH HUMAN VARIABILITY

In 2021, former Olympic high jumper and University of Nebraska track coach Dusty Jonas published an article in “Techniques Magazine” that presents a mathematically derived model of the high jump approach,

offering coaches a more structured alternative to the trial-and-error methods often used in the past. Jonas suggests that his geometric model can give “a more precise measurement of where an athlete’s approach should be,” with the benefit of minimizing variation “of a few inches instead of changing a few feet from practice to practice.” No doubt, his work serves as a valuable reference point for understanding approach geometry, but he also acknowledges that his blueprint is not static, an important consideration when working with developing athletes.

In practice, however, meaningful fluctuations occur in stride length for all athletes from day to day. The athlete who shows up on Tuesday is not the same athlete who shows up on Friday. In my own coaching, I have observed 3-stride starting marks easily shift by more than a meter between seasons, or shift based on other factors, such as rain, prior training load, and even academic stress. These changes are not anomalies. The central nervous system is a moving target and we always have to meet it. A stride-based, observational approach allows coaches to respond more directly to these natural fluctuations.

CONCLUSION

A coaching methodology grounded in observable stride length and live adjustment offers advantages that extend beyond the use of a static reference model. By prioritizing real-time observation over a pre-calculated radius, the approach aligns with the athlete’s current state of readiness. Adjustments match an athlete’s actual output on a given day. This also sharpens your coaching eye, and shifts attention toward rhythm, posture, and foot strike. Over time, you will learn to trust what you see and make adjustments— often as little as six inches—to keep the takeoff in the right place. Finally, anchoring the approach in broad, practical stride-length

ranges makes the framework scalable as speed, strength, and technical proficiency increase. In this way, individualized geometric models can help organize the approach, but a stride-based system gives coaches a practical toolkit for solving problems as they show up in real time.

Good coaching begins with simplification. While biomechanical research provides the raw data for our sport, its practical implications are not always obvious from tables or graphs alone. Those insights are often clarified and validated through experience and repetition on the track. A technical model should not be viewed as a fixed prescription, but rather as an evolving synthesis of evidence-based conclusions refined through daily coaching practice. Whether a technical model is supported by formal data or by experience matters less than whether it consistently holds up in practice. When we strip away unnecessary complexity and focus on how athletes move and how their movements change, we make better adjustments, communicate more clearly, and manage variability more effectively. The result is

not just better performances, but a higher standard of coaching that allows athletes to reach their potential.

REFERENCES

Dapena, J. (1995). How to design the shape of a high jump run-up. Track coach, 131, 4179-4181.

Dapena, J. (1988). “Biomechanical Analysis of the Fosbury Flop.” Track Technique, 104, 3307-3317.

Dapena, J., Ae, M., & Iiboshi, A. (1997). A closer look at the shape of the high jump runup. Track Coach, 138, 4406-4411. https:// sportbm.publichealth.indiana.edu/paperhj-1997.pdf

Dapena, J. & Ficklin, T. (2007). High Jump Report #32 (pp. 2-4, 24). Indianapolis: USA Track and Field.

Dapena, J., McDonald, C. and Capert, J. (1990). A Regression Analysis of High jumping technique. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 6:246-261.

Jonas, D. (2017) High Jump Approach Mapping: A New Way To Develop A Consistent High Jump Approach. Techniques

Magazine, Vol. 10, No. 4, 8-22. https://issuu. com/renaissancepublishing/docs/techniquesmay17

Kaminsky, N. (2025) Building a Better High Jump: A Review of Stride Patterns. Simplifaster Blog, June 2025. https://simplifaster.com/articles/building-a-better-highjump-a-review-of-stride-patterns

NOAH KAMINSKY IS A VOLUNTEER JUMPS COACH AT THE HUNGARIAN UNIVERSITY OF SPORT SCIENCE IN BUDAPEST. HE HAS COACHED TRACK FOR SEVERAL CLUBS AND TEAMS IN THE NEW YORK AREA FOR THE PAST 10 YEARS, INCLUDING THE DALTON SCHOOL, HUNTER COLLEGE HIGH SCHOOL, THE UNIVERSITY OF MOUNT SAINT VINCENT, AND APEX VAULTING CLUB IN NEW JERSEY. BETWEEN 2021 AND 2023, HE COACHED CLINICS FOR ATHLETES AND COACHES IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOL ATHLETIC LEAGUE. KAMINSKY IS A USATF LEVEL 2 COACH, AND OPERATES COACH KAMINSKY ATHLETIC CONSULTING, AN ONLINE SERVICE TO SUPPORT COACHES WITH PERFORMANCE, TEAM CULTURE AND PROGRAMMING. YOU CAN CONTACT HIM AT COACHKAMINSKY.COM.

KIRBY LEE IMAGE OF SPORT

•

•

•

•

Going Distancethe Dynamics of the Airborne Phase

in Discus Throwing

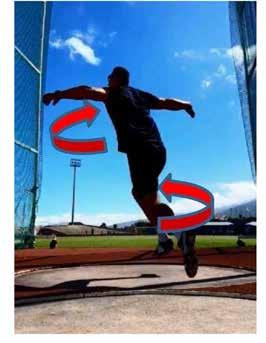

During a discus throw, an airborne phase follows the first double and first single support in the back of the ring, before the thrower assumes his final position for the delivery of the discus. From a mechanics point of view, the execution of the airborne phase can affect the execution of the delivery phase, and eventually the distance thrown. The basic dynamic elements of the airborne phase are examined below.

Terms:

CCW= Counterclockwise, or towards the thrower’s own left.

CW= Clockwise, or towards the thrower’s own right. Airborne phase= The period between left foot take off in the back of the ring and right foot touch down in the middle of the ring.

BASIC CONCEPTS

In the back of the ring, during the turning of the athlete+discus system CCW, the thrower will generate the majority of the total angular momentum for the throw (Dapena, 1997). Following that phase, the thrower becomes airborne, and while airborne, the total angular momentum is conserved, and it remains constant unless acted upon by an external torque. While airborne, the only force made on the system is weight. Since the weight force is exerted at the center of mass of the system, it makes zero torque about the c.m. Therefore, angular momentum always stays constant while the athlete is in the air. When the thrower’s extremities are away from the axis of rotation, (body) the athlete+discus system has great inertia and it has a tendency to rotate slower. When the thrower’s extremities are closer to the center of rotation, the athlete+discus system has low inertia and it has a tendency to rotate faster.

While airborne, the upper body has a certain amount of momentum, and the lower body likewise. It is possible to transfer angular momentum from one part of the body to another with the use of the oblique muscles while the total amount of momentum remains the same.

THE SPEED OF THE TURN IN THE MIDDLE OF THE RING

During this phase, throwers can rotate at various speeds from very fast to quite slow depending on ability and anthropometric characteristics. A question that immediately arises then, is as to how the speed of rotation may affect the outcome of the throw, and what may be the factors that are involved to help one assess the importance of the speed in the middle of the ring. In other words, does the thrower need to minimize the time it takes to complete the airborne phase? Furthermore, how this time interval may affect the overall outcome of the throw?

Central in this assessment, is the consideration of the planting of the left foot in the front of the ring, i.e., how the airborne phase

may affect that action. The reason is the fact that unless the left foot plants, the delivery phase cannot begin. [(Note: The throwing action in reality begins just briefly before the left foot plants in the front of the ring (Dapena, 1997)]. That planting then needs to be quick and very active, to ensure, among other reasons (see also Maheras, 2011), that the upper body does not have the opportunity to rotate CCW and that the discus is as CW as possible. If the athlete has a lot of angular momentum (a very good thing), and then lets the left foot linger in the air instead of dropping it down to the ground as soon as it is in the right position, it is very likely that the discus will travel CCW too much before the left foot is planted. That will then reduce the time the thrower will have available to transfer angular momentum from the body to the discus (during the second doublesupport), and that would be counterproductive for the outcome of the throw (Dapena, 2025).

Given that the thrower, while airborne, can do nothing to increase or decrease the system’s angular momentum, the speed of

the turn will not influence the amount of momentum generated thus far. Therefore, the issue is not whether the angular momentum of the whole system may decrease or increase while airborne. The issue will be more about whether the thrower will have enough time in the final delivery phase to TRANSFER angular momentum from the body to the discus before the discus is released.

MECHANISMS FOR THE PROMPT PLANTING OF THE LEFT FOOT

So, how can the thrower get the left foot to reach quicker the position where it can be set down to land on the ground? During the airborne phase the thrower can position his extremities close or away from the axis of rotation, which is the thrower’s torso. Again, being “wide” or being “closed” in the airborne phase does not affect the generation of angular momentum. But it can affect the time when the left foot lands to start the double-support delivery.

In the discus, the thrower wants the lower body to rotate fast so that the left foot can

FIGURE 1. AIRBORNE PHASE CONFIGURATION WITH THE LEFT ARM AWAY FROM THE BODY. TOP ARROW= POSSIBLE CLOCKWISE ROTATION OF THE UPPER BODY; BOTTOM ARROW= COUNTERCLOCKWISE ROTATION OF THE LOWER BODY.

plant earlier. But he also wants the upper body to rotate more slowly than the lower body so that the upper body will be in a very clockwise position relative to the lower body at the instant when the left foot lands. The difference in rotational speed between the lower body and the upper body can be achieved by two mechanisms:

WITH THE LEFT ARM EXTENDED

Here the thrower keeps his left arm relatively away from the body through the airborne phase (figure 1).

1st mechanism: The thrower will keep a “wide” upper body, i.e., both arms are relatively spread out (figure 1), while keeping a “narrow” lower body. This will increase the moment of inertia of the upper body and it will slow it down, but it will continue rotating CCW. In fact, it will rotate CCW so much slower than the lower body, that it may seem to an outside observer that the upper body rotates CW, but it doesn’t. Relative to the lower body, the upper body does rotate clockwise, but in absolute terms (i.e., rela-

FIGURE 2. AIRBORNE PHASE CONFIGURATION WITH THE LEFT ARM CLOSER TO THE BODY. TOP ARROW=POSSIBLE CLOCKWISE ROTATION OF THE UPPER BODY; BOTTOM ARROW= COUNTERCLOCKWISE ROTATION OF THE LOWER BODY.

tive to the ground), it will continue rotating CCW, more slowly CCW but still CCW. However, increasing the moment of inertia of the upper body will NOT automatically make the lower body speed up its own CCW rotation. It will slow down the CCW rotation of the upper body, but it won’t speed up the rotation of the lower body. This mechanism of keeping the upper body spread out is still a good thing, because it keeps the upper body (including the discus) further back (further CW) relative to the lower body. So this ensures that, whenever the left foot gets planted on the ground, the discus will be far back, and therefore will have a longer range of motion available for acceleration before release. The (relatively) extended arm configuration, while airborne, does slow down the CCW rotation of the upper body, but it does nothing to accelerate the lower body. Although an observer may see that the lower body “outruns” the upper body (CCW), this is due to the fact that the upper body slows down, not that the lower body speeds up. By the same token, if the first mechanism

does nothing to speed up the lower body, is there some other mechanism at play, a mechanism that will actually increase the CCW speed of rotation of the lower body? Yes. 2nd mechanism: The thrower can activate the oblique muscles of the trunk to make the upper body exert a CCW torque on the lower body, and by reaction a CW torque on the upper body. Such an action will make the upper body rotate even slower CCW, and the lower body rotate even faster CCW. To make the lower body rotate faster CCW, the oblique muscles have to be involved. Changes in the moment of inertia of the upper body, and action-and-reaction torques between the trunk and the left arm, none of that will have a direct effect on the CCW rotation of the lower body. The only way to increase the CCW rotation of the lower body is by using the oblique muscles of the trunk. In addition, the thrower can also change the speed of rotation of the lower body by changing its own moment of inertia, like keeping the legs closer together to each other.

The thrower then, through this mechanism, uses the muscular actions of the oblique muscles of the trunk, which will transfer momentum from the upper body to the lower body, which will, in turn, result in an increase of the amount of angular momentum carried by the lower body and decrease the amount of angular momentum carried by the upper body. If the upper body remains wide while the lower body gets narrow, the lower body will increase its speed of rotation, which is good because it will make it possible to plant the left foot on the ground sooner. Meanwhile, the upper body will rotate slower, which will make the shoulders and the discus be very clockwise in relation to the lower body at the instant when the left foot gets planted. This is also good, because it gives the thrower more time to transmit angular momentum to the discus in the subsequent double-support delivery action.

WITH THE LEFT ARM “WRAPPED”

In this configuration, the thrower keeps his left arm closer to the body through the airborne phase (figure 2).

Here, the first mechanism employed in the previous, extended arm, configuration cannot be of much help because the combined left arm+upper trunk system will have a smaller moment of inertia and will therefore tend to rotate faster instead of

slowing down, and it will have the tendency to advance CCW due to its lower inertia. Moreover, the CW action of the left arm itself across the body (the “wrapping” action) will be produced by a CW torque that the upper trunk makes on the left arm through the muscles of the left shoulder. By reaction, the left arm, through those same muscles, will make a CCW torque on the upper trunk, and this CCW torque will also tend to make the upper trunk rotate CCW faster.

Indeed, the “wrapping” of the left arm around the chest does make the upper body a little bit less “wide,” and this is by itself counter-productive from the point of view of increasing the speed of the CCW rotation of the upper body. However, the thrower can help the lower body rotate faster CCW through a different mechanism, i.e., a rotational action-and-reaction mechanism, closely linked to the transfer of angular momentum from the upper body to the lower body. In addition, the “wrapping” of the left arm around the chest has a separate benefit in that it can be later thrown CCW over a longer path, in the early part of the double-support delivery. This is a beneficial action which will help generate more CCW angular momentum for the thrower+discus system during the early part of the doublesupport delivery, through the interaction of the feet with the ground (also see Maheras, 2011, 2022).

In the end though, we do want the left arm to be in a very CW (=”wrapped”) position at the time when the left foot lands to start the double-support delivery, for the advantages it offers during the delivery phase. But, as mentioned above, such an action will tend to make the upper trunk rotate faster. And we don’t want that to happen at this stage of the throw because as the upper body rotates CCW there will be less distance and time for pulling the discus.

So, what can be done to prevent the upper trunk from rotating faster CCW as the left arm gets “wrapped” CW? Here the thrower needs to remember the 2nd mechanism that was mentioned earlier in the “extended arm” configuration, which is the employment of the oblique muscles of the trunk. At the same time that the upper trunk receives the CCW torque from the left arm, the upper trunk can be rotated CW and by reaction make a CCW torque on the lower body. So by this use of the oblique muscles, it is possible to wrap the left arm without resulting in an increase in the speed of the CCW rotation of the upper trunk, and in fact, it will help to speed up the CCW rotation of the lower body, which is a good thing.

It is noted here that in both the “extended” and the “wrapped” left arm configurations, the thrower+discus system should have as much angular momentum as possible, angular momentum that was generated

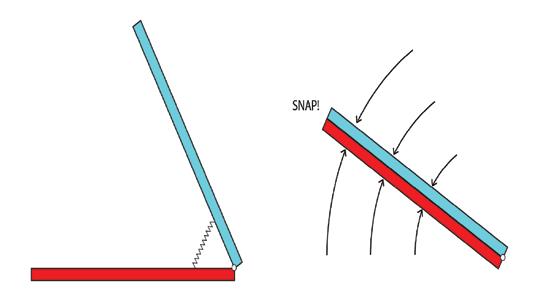

FIGURE 3. THE OBLIQUE MUSCLE ACTION ILLUSTRATED.

HIGH-PERFORMANCE TRACK DESIGN AND SURFACING

With decades of experience working with top-ranked programs across the country, TenCate brings the latest in surfacing, design and construction technology to the track market.

Randal Tyson Track Center (Top) University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR Host of the 2026 NCAAA DI Indoor Track and Field Championship

Fasken Indoor Track & Field

Texas A&M University, College Station, TX

tencategrass.us

Building healthier, more beautiful communities.

previously during the double-support and single-support phases in the back of the ring.

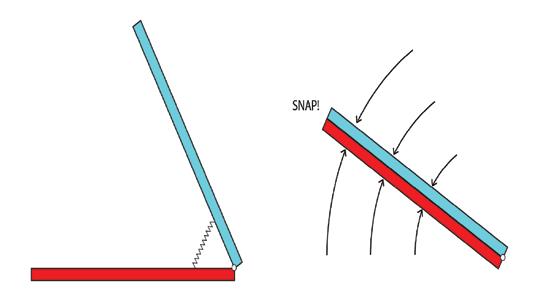

THE ACTION OF THE OBLIQUE MUSCLES ILLUSTRATED

Figure 3 shows two bars, one red and one blue, both free to swivel around a hinge joint. There is also a stretched spring that connects them and that is trying to snap them both together. Let’s say that the two bars are held “open” with the hands (image on the left). From this position, if both bars are released, they will snap together (image on the right). The spring made the blue bar rotate CCW and it also made the red bar rotate CW. It produced the movements of both bars.

Did the red bar make the blue bar rotate CCW? Yes, but it needed to do it through the action of the spring. Did the blue bar make the red bar rotate CW? Yes, but it needed to do it through the action of the spring. Without the spring, the two bars would have stayed “open” (as in the image to the left). In this simple illustration with the two bars and the spring, one bar is analogous to the upper body; the other bar is analogous to the lower body; and the spring is analogous to

the oblique muscles. The oblique muscles make the upper body rotate CW and the lower body rotate CCW. In the same way, the opposite oblique muscles will make the upper body rotate CCW and the lower body rotate CW.

ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND THE PLANTING OF THE LEFT FOOT

A question that may arise in this discussion, is regarding the amount of momentum available to the thrower in the case where the thrower, through ignorance or lack of coordination, significantly delays the planting of the left foot following the landing over the right foot in the middle of the ring. Once the right foot lands, the thrower will be in single-support over the right foot. During that period of time, he will receive a force from the ground, something that is unavoidable. That ground reaction force can increase the angular momentum, it can decrease the angular momentum, or it can leave the angular momentum unchanged. This is because that force, in the view from overhead, can point off-center to the center of mass, or right through the c.m., and therefore, it can make a torque

(CW or CCW), or no torque at all.

Those options are all mechanically possible. However, in practice, in a discus throw the ground reaction force tends to pass pretty much through the c.m. in the view from overhead (Dapena, 1997). Therefore, during the single-support on the right foot, there is essentially no torque, and therefore angular momentum stays pretty much constant (Dapena, 2025).

CONCLUSIONS

From a mechanical point of view, it is not very important to minimize the time it takes to complete the airborne phase or how fast the thrower turns in the middle. On the other hand, throwers who generate more angular momentum in the back of the circle will tend to rotate faster, which in turn will tend to shorten the time between takeoff in the back of the circle and left foot landing in the front of the ring. Technically, as long as the thrower is very “wrapped” (very clockwise position of the shoulders and of the discus relative to the hips and the feet), the thrower should be OK. The critical moment is actually not the landing of the left foot per se, but the instant when the body starts

to “unwrap,” which is just a little bit earlier than the landing of the left foot in the front of the circle (Dapena, 1997).

There are four viable configurations for the thrower during the airborne phase. First option, the thrower allows the left arm to be relatively extended throughout the phase and hopes that the increased inertia of the upper body alone will allow the lower body to run ahead of the upper body and plant the left foot quickly. Second option, as in the first option, but in addition to the inertia of the upper body, the thrower can actively rotate it CW to make the lower body rotate faster CCW and hopefully plant the left foot even faster. In the third option, the thrower wraps the left arm so he can take advantage of the CCW “throwing” action of that wrapped arm during the release phase, and also hoping that the unwanted CCW rotation of the upper body will not seriously affect the planting of the left foot. Fourth option, as in the third, but in addition, the thrower mitigates the increased CCW upper body rotation, as he actively rotates the upper body CW to slow down the CCW rotation of the upper body and speed up the CCW rota-

tion of the lower body.

Option four is the recommended option because it takes advantage of both, a.) a slowly CCW rotating upper body, and also, b.) the extensive “throwing” of the left arm CCW to further aid in the delivery of the discus, which are two factors that the other options do not adequately satisfy. The thrower then, can and should stop any increase in the CCW rotation of the upper body by using a stronger action of the oblique muscles, while at the same time brings the lower extremities closer together to decrease their inertia and speed up their CCW rotation, which is what the thrower wants.

By planting the left foot on the ground very early, the thrower will help the upper body, the right arm and the discus to be still in a very CW position at the start of the double-support phase. If he delays, for whatever reason, the planting of the left foot, then since the upper body, right arm and discus are all already rotating CCW, the delay in the landing of the left foot will allow the upper body, right arm and discus to rotate CCW through a longer CCW range

of motion before the start of the final double support phase. This will leave a shorter CCW range of motion available for the upper body, right arm and discus to rotate during the final double-support phase. In turn, this will reduce the capability of the thrower to transfer angular momentum from his body into the discus.

The thrower can slow down the upper body as much as he wants, as long as he does not interfere with the normal course of the throw and he is indeed able to set up a normal second double support for the delivery of the discus. In that direction, the thrower should be advised not to overdo the slowing down of the upper body, as in completely stopping its rotation, with the use of the oblique muscles, because as the upper body’s angular momentum will tend to go to zero, the thrower will not have enough total momentum (upper body+lower body) to transfer to the discus, and the throw will resemble a standing throw. Transferring all upper body momentum to the lower body, while in the air, is possible mechanically but impossible to physically execute. It would make the lower body rotate so much more (so many more degrees) than the upper body, that nobody would be flexible enough to do that. In that impossible position, the shoulders would be facing forward (towards the direction of the throw), but the pelvis would have to rotate 180 degrees more CCW, facing perfectly backward, and nobody can do that.

REFERENCES

Dapena, J. (2025). Personal communication. Dapena, J. and W.J. Anderst. (1997) Discus throw, #1 (Men). Report for Scientific Services Project (USATF). USA Track & Field, Indianapolis.

Maheras, A. (2022). Speed GenerationMomentum Analysis in Discus Throwing, Techniques for Track and Field & Cross Country, 15 (4), 34-42.

Maheras, A. (2011). The Function of the Extremities in Discus Throwing. Techniques for Track and Field & Cross Country, 4 (4), 8-16.

ANDREAS MAHERAS, PH.D., IS THE LONG TIME THROWS COACH AT FORT HAYS STATE UNIVERSITY IN HAYS, KS, A FREQUENT CONTRIBUTOR TO “TECHNIQUES”, AND THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL OTHER ARTICLES PERTAINING TO THE THROWING EVENTS; SCHOLARS.FHSU.EDU/TRACK

Always Improving

A panel of leading coaches discuss 800-meter training topics, techniques and ideas.

The idea that there are many different ways to successfully train athletes in track and field is a commonality that has surfaced in all my articles concerning training. There are certainly a lot of different ways to successfully train 800-meter athletes, and this coaches’ question and answer article proves that.

This is what always strikes me as being very exciting about a coaches’ roundtable forum: coaches are exposed to different methodologies and training perspectives, insights, and information. That, in my mind, is invaluable. As a young coach (and often even as a not-so-young coach), I was often overwhelmed by what training my athletes should be doing. I would go to a clinic and see something that I felt was really good. Then, a month later, I would see another training program and really like that. On and on it went. Always looking for the perfect training program.

The reality shows us that there is no perfect training program. A line from John Steinbeck’s book “East of Eden,” where he talks about giving yourself permission to act, learn, and grow, sums this up very well: “And now that you don’t have to be perfect, you can be good,” the author says.

That is very true. The training programs of great coaches are constantly evolving and changing, always improving. Nearly all great coaches are open to new ideas; they are always self-evaluating and eager to learn. They are always customizing and individualizing training. They are never content with the status quo. I have often said that complacency, whether it be in athletics, business or really any facet of life, is a kiss of death The master himself, Dan Pfaff, a retired former collegiate and elite professional coach, said it best: “One of the biggest hurdles to growth, learning and progress can lie within our own certainty,” noted the long-time Altis coach. “When we believe we already understand something, we lose our curiosity. Embracing new ideas can then feel threatening as it requires us to confront and possibly overturn our previous understanding, making us feel vulnerable. The most effective coaches, whether seasoned or still early in their journey, carry the mindset of a curious student of the craft,” he stated.

Most of my training programs that were successful were the result of a lot of mistakes and trial by error. They certainly weren’t perfect. I have always liked the quote by the late Ralph Mann when talking about the “correct” or “right” training: “There is no right or wrong way of coaching,” said the former 400-meter hurdler great, and a pioneer in sports research, “only a better way.”

The better way for most coaches, including me, was finding what works for your athletes in your particular setting, program and environment. It took me a long time to figure that out.

None of the running events are easy to train, but the 800 meters may be more difficult due to the complexity and specific type of athletes that

KIRBY LEE IMAGE OF SPORT

compete and do well in the race. This goes back to my philosophy that stresses the need for individualized training. The first item on the agenda for any coach is to establish what type of 800-meter runner they are training. Are they training a “sprint-type runner” who is moving up in distance, or a middle distance/ distance runner who is moving down?

A prime example of this occurred in the University of Mary program in 2013 when two athletes ran basically the same 800meter times utilizing totally different training programs. I had the privilege of coaching Brie Lynch, who was a part of our 2013 national championship distance medley relay team. She was a former high school sprinter who didn’t do cross country, and who excelled in the 600 meters. Brie loved sprint-type interval training and was often below 20 miles for weekly mileage. Melissa Agnew, an NCAA Division II Hall of Fame athlete who was a national champion in the mile/1500 meters, was a cross country All- American who loved mileage. She was coached by one of the nation’s best cross

country and distance coaches, Dennis Newell, a many-time coach of the year. Despite having vastly different training programs, they ran nearly identical times. Lynch ran 2:08.89 (a school record at the time) and Agnew 2:08.99, proving that there are many different ways to train for excellence in the 800 meters.

Our past roundtable forums were received very well, with coaches saying they really enjoyed the different ideas and philosophies of their peers and successful, proven practitioners. I have always felt it is an obligation for coaches to share their knowledge and expertise. A quote by James Taylor, a famous musician best known for the song “Fire and Rain,” speaks to this: “Musicians have a duty and responsibility to reach out and share love and pain,” said the singer known as “Sweet Baby James.” The same could be said about coaches in the athletic world. That has always been our mentality. We are very grateful to the coaches who were willing to share their expertise in this article to help educate other coaches. The panelists for this

forum consisted of a mixture of young and veteran coaches, with eight of them being NCAA Division 1 mentors, one from NAIA, and one from a junior college. I most often ask seasoned coaches to be in our coaching conclaves because they are typically “smart” after having failed enough to learn what does and what doesn’t work. The coaches for part one include Nate Wolf from Dordt (IA), Brandon Bonsey from Georgetown, Houston Franks from LSU, Dennis Newell from North Dakota State University, Jeremy Wilk from the University of Miami, Pat McCurry from Boise State, Cade Burks from Sacramento State, Jeff Pigg from North Florida, Dee Brown from Iowa Central, and Ryun Godfrey from Oklahoma State.

A quick look at the coaches with a short bio on each:

Ryun Godfrey (Oklahoma State) Godfrey is in his second year at Oklahoma State as a cross country and distance assistant coach, following a stint at Nebraska as the head cross country coach. A 28-time conference coach of the year, Godfrey has also coached

at Arizona State, Kansas State, and his alma mater, North Dakota State University in Fargo, ND. It was at NDSU, where Godfrey graduated in 1996, that he had amazing success, winning 30 conference championships and an NCAA Division II women’s national championship in indoor track and field. The long-time coach was a six-time regional coach of the year, as well as a Division II national coach of the year. The success has followed Godfrey to Oklahoma State, where the Cowboys won the men’s national championship in cross country this past fall.

Pat McCurry (Boise State) McCurry is in his second year as the Broncos track and field and cross country coach after serving as an assistant coach 2016-18. McCurry, known for having strong 800 and steeplechase runners, had a highly successful career at the College of Idaho, mentoring 14 NAIA national champions. He also had a successful tenure at Division 1 San Francisco (201821). McCurry, who has coached 21 Olympic Trials qualifiers, was an assistant coach at his alma mater, Eastern Oregon, prior to Idaho. McCurry continues to coach world class, elite athletes, including Olympians Lizzie Bird of Great Britian, seventh in the steeplechase at Paris, and Marisa Howard of the USA, who was ninth in the steeple at the Paris Olympic games.

Cade Burks (Sacramento State) Burks is entering his third year of coaching the distance, cross country and mid-distance athletes at Sacramento State, arriving at the university in 2023. With Burks at the helm, the distance program has improved immensely, with multiple school records, over 20 top-10 school performances, and multiple NCAA first round appearances and Big Sky finalists. Prior to his tenure at Sacramento, Burks ran at Northern Arizona University from 2016 to 2021 where he was a part of four national championship cross country teams and was a four-minute miler on the track.

Jeremy Wilk (University of Miami) Coach Wilk is in his third year at the University of Miami in Florida and it has been a very successful one, having coached school record holders and numerous top performers in the ACC conference. Wilk serves as the distance coach and cross country mentor for the Hurricanes. Prior to Miami, the two-time All American from Grand Valley (MI), who had the school record in the 800 meters at 1:45.40, was at Northwood in Michigan. He was at the Michigan institution from 20162023, taking over head coaching duties in 2021. His athletes broke school records 33

times while he was at Northwood and he coached Jordan Chester, a 2020 Olympic Trials qualifier. Wilk was at Ashland in Ohio as an assistant and director of operations prior to Northwood.

Brandon Bonsey (Georgetown) Coach Bonsey is in his seventh year as the very successful head coach of the Hoyas men’s cross country program and middle distance/ distance athletes in the Georgetown track and field program. Bonsey has coached 49 All-Americans in 10 different events after returning to his alma mater for the 2012-13 campaign. Prior to returning to Georgetown, he had been at Syracuse. Coach Bonsey competed for the Hoyas 2004-09, graduating in 2009. He coached for the Hoyas as an assistant before heading to Syracuse.

Jeff Pigg (North Florida) A veteran coach who has a lengthy record of success everywhere he has been, Pigg came to North Florida from Georgia in 2012 to serve as the director of track and field and cross country. He has guided his North Florida teams to their best showings in their Division I era, winning a number of ASUN conference titles in cross country. Prior to the Georgia stint, Pigg was the head cross country coach at Florida, his alma mater from which he was a1988 graduate. The many-time coach of the year also spent 10 years at the University of Missouri.

Dee Brown (Iowa Central) Coach Brown has had an unbelievable career since starting the cross country and track and field programs at junior college powerhouse Iowa Central. Since starting the program in 2004, he has led the Tritons to 40 national championships. He has been named JUCO national coach of the year 14 times. The men’s and women’s director of track and field and cross country, Brown has guided his women to eight national cross country championships and the men five. His teams have also won 14 national half marathon team titles. Brown was at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, prior to coming to Iowa Central.

Nate Wolf (Dordt IA) (With assistance from Craig Heynen, the Dordt head track and field coach. See Coach Wolf’s note at end of bio) Coach Wolf is the head men’s and women’s cross country coach and assistant in charge of the distance runners at Dordt, an NAIA school in Iowa. He has had amazing success in cross country. Since he arrived in 2015, his women’s teams have won eight GPAC conference titles, earning him coach of the year all eight of those years, and the men have won seven conference

titles, earning him coach of the year seven times on the men’s side. He has also won two regional coach of the year awards with his women and five with the men. A graduate of Northwest College in Iowa, his first coaching position was at his alma mater from 2005-12. He spent 2012-15 at Southwest Minnesota in Marshall, MN. A note from Coach Wolf: As a point of reference, in our program the 800 runners are split into those that do cross country and those who do not. I coach the cross country group, as I combine their cross country training into the track season plan. Coach Heynen coaches the non-cross country 800-meter runners. Our philosophies are pretty similar, but due to the type of athletes, their physical and psychological makeup, we emphasize different aspects of the training to get them to similar places. Our answers to the questions may read like two people contributed to the writing, because we both did. In our program, the 800 meters is a link between the distance groups and sprint groups.

Houston Franks (LSU) The LSU Tigers program has flourished under Coach Franks, who is in seventh year at the Baton Rouge school. The program has been remarkably successful from both a team and individual standpoint. Some of Franks’ most notable individuals include Marco Arop from Canada, the world champion in the 800 meters in 2023 and a silver medalist in the 800 at the Paris Olympics; Michaela Rose, a former NCAA 800-meter national champion who recently signed with Adidas; and Lorena Rangel Batres, the 2024 Mexican national champion in the 800. Franks, who came to LSU from Mississippi State, coached at Southwest Missouri State (1999-2004) for five years where his women won three conference championships and he was the Missouri Valley Conference coach of the year three times. Franks, a 1998 graduate of Mississippi State, is very involved in coaching education, presently serving as the lead instructor for the USTFCCCA Academy endurance, middle distance, and distance master’s level courses.

Dennis Newell (North Dakota State University) Astounding success has been a trademark for Coach Newell, who is in his fifth year as the Bison cross country coach and assistant track and field coach. Newell has contributed to nine Summit League Team titles for the Bison indoor and outdoor track and field program since his arrival in the fall of 2021, with the Summit League women’s cross country coach honors being

ALWAYS IMPROVING

one of his top accolades. Prior to NDSU, Newell spent 15 years at the University of Mary, developing the Marauders into a regional and national power in cross country and track & field. The Marauders won 24 NSIC team championships in cross country and track & field during his tenure, including 19 titles in women’s track & field since 2007. The Mary women earned NCAA Division II runner-up team finishes in cross country in both 2017 and 2018 and earned an NCAA Division II podium finish (4th place) in indoor track & field in 2018. Newell has mentored 172 NCAA D 2 All-Americans and 12 individual national champions, including Ida Narbuvoll in 2021, who won national titles in both the 5000 and 10,000 meters, setting the Division II outdoor 5,000-meter record. Narbuvoll also won the 2021 Norwegian national title in the 10,000 meters. Newell boasts 21 coach of the year honors in his career, highlighted by being named the 2013 NCAA Division II Indoor Women’s Assistant Coach of the Year.

Without further ado, let’s get into the questions and answers. Each of the 10 coaches were asked to answer the same 12 questions, with six questions being addressed in this first installment, and the second set in part two to follow. Some of the answers were edited for brevity and the coaches were free to select what questions they chose to answer.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

DO YOU TAPER OR DO ANYTHING DIFFERENTLY TO PEAK FOR CHAMPIONSHIP MEETS? EXPLAIN.

Godfrey: On competition weeks, we reduce the volume of the training sessions. At the end of a season our volume is less than it is at the beginning of the season. So, yes, we do taper. However, the taper is not significant.

McCurry: Yes, but I’ve never believed in a gradual taper down in training load. We drop things pretty significantly at a sensible point heading into the championship phase. I am also more concerned about lowering high intensity in training than volume at that point, though we do over the course drop volume some. Middle distance athletes race a lot in the championship season with rounds, so the races themselves bring a frequent intensity load.

Burks: Our speed-based 800-meter athletes do not significantly taper in mileage, as their mileage throughout the season is

generally quite low. However, a small reduction of total volume will occur as we shift towards shorter, faster sessions. Aerobic work becomes more vVo2max-focused and our anaerobic sessions increase in intensity. For example, 2x300-200 at paces faster than their 800-meter race pace was used in the championship period of the year. For aerobic/distance -based 800-meter athletes, mileage drops by up to 40%. Decreases any higher than that have caused my athletes to feel “flat.” For these athletes, the intensity of the main training sessions of the week will be increased, with workouts prioritizing running fast while at high lactic acid levels. For example, 600-400-300-200-200, descending from mile to sub-800-pace one week out from our conference championship. We maintain weekly lactate threshold work throughout the championship phase.

Wilk: Yes, I try to make sure that the athletes feel strong, sharp, and confident. Sometimes they need a “cupcake” workout that feels much easier than they expect, and other times they need to just feel comfortable running fast. I base it off what I feel the particular student-athlete needs.

Bonsey: Yes, we do taper for the championship meets both indoors and outdoors. Really every aspect of their training is reduced to have them feeling as fresh as possible. Their weekly volume and long run are reduced, although not by much. The volume in the weight room is scaled down. The amount of threshold they do on their Tuesday workout will be reduced and the Friday workout the week before generally will be something with a lot of rest. That way they come out of the workout not too fatigued. There is a holistic approach taken to tapering. I’ve always found middle distance runners respond to rest and a taper more than pure distance runners.

Pigg: Peaking is somewhat individual. We cut down volume and increase speed. 20-15 days out we do 3 x 300 full speed with full recovery. Two weeks out we do a 600-400200, and the week of a race, 500/300 race simulation. Approximately 2:30 rest. We don’t cut much on the volume of mileage, as it stays consistent.

Brown: Our volume is less than it is during the season. Our workouts are more intense, and there is more fine-tuning. Back 10-15 years ago, I used to drop the volume con-

siderably. We don’t do that any longer. The volume is less so they feel fresher and are more physically and MENTALLY recovered, but we keep the volume relatively close to the previous two weeks.

Wolf: It can depend a little on the specific athlete, but as a general rule, we tend to decrease the volume and maintain the intensity as we get close to the championship meets.

Franks: The only thing that we do different in terms of “peaking” (which is a word I don’t love, I really like the word “optimize” better in terms of our thought process) we do reduce the volume of the sessions the last couple of weeks, but the intensity remains high. Absolutely no reduction in intensity. We do also have a slight reduction in density of workouts, meaning we may take an extra recovery day here and there to ensure proper recovery from a certain session. Workouts at this time of the year are designed to bring confidence and are often geared around race modeling (not necessarily every workout is race modeling, but many are).

Newell: 10-14 days out from our goal race we taper down the ‘hard’ workouts volume, while maintaining the “hard” workouts intensity. Consistency is king. We continue to do what has allowed a student-athlete to progress over the entire season, with situational adjustments. We remind our student-athletes there is no magic workout… the magic is health, consistency, sustainability, and passion. There is usually a natural tendency to press in the hard workouts at the end of the season, but we try to avoid “pressing” or “going to the well” outside of the designed paces at the end of any training cycle. We are looking for energy system and biomechanical efficiencies at the end of the training cycle. I monitor effort and movement more than I do splits and paces the last two weeks of a training cycle.

QUESTION 2: WHAT FORMS OF RECOVERY DO YOU BUILD INTO YOUR TRAINING PLAN? EXPLAIN.

Godfrey: We typically have a rest day once per week. In addition, there are times during the season that we provide for multiple days of rest in a row. I didn’t do this earlier in my coaching career, but I’ve learned how valuable this can be to help ‘reset’ and keep things fresh. Also, at the end of the season we will take two weeks off from training. This

is something we have always done. Other forms of recovery include cross training, cold tubs, hot tubs, and massage therapy.

McCurry: We explain training as “stress AND recovery”... with the recovery half being just as critical to the seeing of the adaptation we seek. Good sleep is what we emphasize the most, followed by fueling regarding both high volume and optimal timing of intake. As far as recovery elements in training, I’m a big believer in EVERYONE having one non-run day per week, even highly developed elite athletes. For younger middle distance athletes, I usually want one light cross training day and one day completely off... sometimes even a third day of cross training. We work when we work and recover between.

Burks: Within my training plan we have a couple points of recovery. Our training plan goes from Monday to Saturday, with Sunday being a rest day each week. We also have a focused mobility and drills day twice a week.

Wilk: The most common one is easy days. I think that the greatest benefit of these super easy, and not very long runs, is that running doesn’t feel like a chore that day. We practice at 6/6:30am or earlier five days per week, so giving them these days on their own when they can sleep in a bit, do it whenever works best for their schedule, and not feel like they are trying to gain fitness on a given day, pays dividends for their longevity. Some of them take a day off per week, or supplement with cross training. The guys who run seven days per week, I tell them that they can take a day off on these recovery days whenever they need. I just tell them to let me know when they take them, so I can track it and look for trends in how they respond.

Bonsey: Our 800 runners run either five or six days a week depending on who they are. They are getting two days a week off from running, which I think helps them recover and stay healthy. All other forms of recovery would be done in the training room with our trainer. We also try to massage once a week.

Pigg: We do easy runs with the last 10:00 barefoot jogging on grass. We run on a Boost at 88% instead of the ground ( Editor’s note: a Boost is a microgravity treadmill that uses air pressure to create a lifting force, allowing the runner to run with a reduced percentage of their body weight.) Cross training with pool running and swimming are primary. We rest!

Brown: Obviously, easy days after the hard sessions are a big part of our recovery. Recovery weeks after three to four intense weeks of training help them rebuild and refresh, too.

Wolf: For athletes who come from cross country, running is the major recovery component. For the long sprint group, recovery days can also include training different energy systems. For example, a max velocity day with low volume and high intensity with some mileage might be an active recovery day. We also utilize our pool for recovery days. Additionally, mobility work is a key component of our recovery days.

Franks: We try to follow scientific data and research on rest periods within sessions and between sessions based on various intensities and volumes. We also have planned recovery weeks within each cycle of training. Typically, we have three building and/or harder training weeks followed by a lesser workload week that serves as our recovery week. That doesn’t mean that we don’t work out hard that week. It would be the usual slight reduction of volume both within sessions and on distance run days (including long runs). Also, workouts are typically structured to be workout and/or types of workouts the athlete typically recovers easily from. Although we typically use the 3-1 rotation, during the season depending on when some of the more important meets fall in the calendar, we may use a 2-1 or a 4-1 rotation to make an important meet line up with a recovery week.

Newell: A well thought-out periodized training program is key. Stress and recovery need to complement each other and work together in harmony. The best recovery modality is a balanced training plan and an appropriate lifestyle that allows the maximum training stimulus and appropriate recovery from said work. Additional steps in the recovery process can be engineered through additional behaviors and thinking. We use ice baths, contrast baths, sauna exposure, hot tub exposure, sports massages, massage sticks, compression therapy, foam rollers, hurdle drills, dynamic movement routines, nutrition, hydration, electrolyte replacement, vitamin and mineral supplementation, sleep, stress management, low intensity/ large muscle group cross training, “easy” running, soft surface strides, med ball routines, strength training, band/ rope stretches, sports psychology, mental skills training, and

meditation. All these recovery modalities can be used based on the recovery needs of each student-athlete within a well-planned training program.

QUESTION 3: CONSIDERING THE PERCENTAGES FOR THE 800 METERS ARE 66% ANAEROBIC, 34% AEROBIC, WHAT DO YOU EMPHASIZE AS YOUR MAJOR ENERGY SYSTEM, AND DO YOU TRY TO BALANCE ALL THE DIFFERENT ENERGY SYSTEMS INTO YOUR TRAINING PLAN?

Godfrey: I try to balance all the energy systems. However, I think the aerobic system is more predominant than 34% of total energy contribution in the 800 meters. My goal is to build the strongest aerobic system possible and at the same time develop speed. In our fall training, we focus on aerobic development and lactate threshold sessions. We also address “speed” (40m – 50m) once per week. As the competitive season approaches, we introduce more VO2 and anaerobic capacity sessions. I do think the anaerobic capacity sessions can be over-done and thereby damage the aerobic development, so I try to be very strategic when incorporating these types of efforts.

McCurry: I’ve always varied this by athlete as there are so many different types of athletes that can come to the 800 meters and have success. One of my key mentors in this area was Brian Janssen, who was at Idaho State in the 80’s, 90’s, and early 2000’s. He had a TON of success in the 800 meters, so I gleaned much from him. He always told me, “train the athlete, not the event.” This of course is commonly said, but carries so much weight in the 800 meters as the athletes can be SO different. If the athlete is more aerobically-based, we feed them more aerobic work. If they are anaerobically-based by nature and sport development, we feed them a bit more on that side. However, across the board, we emphasize the aerobic heavily as there are just bigger margins of improvement to be had there. The trick is knowing how to develop athletes aerobically with different forms of work. You don’t necessarily need to run a bunch of aerobic volume to do this.

Burks: The main focus of the training depends on the strengths of the athlete. For our speed-based 800-meter athletes our main focus is anaerobic power and efficiency. The aerobic work is focused on increasing the athletes training load – making them capable of handling larger workloads and

lactate threshold capabilities. For our more aerobic/distance-based 800-meter athletes, the aerobic system is central in our training. From cross country through the track season, these athletes will be doing large amounts of sub-threshold, threshold, and double-threshold sessions. As the season progresses, anaerobic sessions increase in frequency and intensity.

Wilk: The answer to this question varies greatly with the particular student-athlete. I have had 800-meter runners that run 60+ miles per week and train more like 1500meter runners, and 800-meter runners that train with our sprints coach in spikes twice per week as part of their training. It’s all about what each person responds best to, and what helps them feel strongest for the event. Even our 400/800 runners hop into workouts with the more “distance-based” 800-meter crew here at the University of Miami though, so it’s generally somewhere in a spectrum.

Bonsey: They do threshold work every Tuesday year-round so that is generally how we work on the aerobic system. That and the long run on the weekend. We do sets of 40’s, 80’s and 120’s on Thursday and that serves as a speed development day, but also primes them for the Friday workout. Their Friday workouts are generally race specific and that is where we build up that race pace tolerance. I believe whatever event you’re getting ready for, you need to be in shape to run the event above it and the event below it. I think you can see in our weekly training that we are constantly working at both ends of the spectrum.

Pigg: We are balanced with somewhat of a funnel. Early season we talk about training like a 3000 runner, then a miler for a few weeks, and then becoming more 800 focused the last few weeks. It really depends on the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses. Throughout all phases, we have a balance of threshold-3K-1500-800-400 training.

Brown: We certainly work at balancing the anaerobic and aerobic. We also lean towards training our mid-distance athletes from a distance perspective versus a sprint perspective, so perhaps there is more aerobic work being done. I feel that traditional programs neglect the aerobic base and training and put a much higher percentage of training

into the anaerobic system. While our 800meter runners excel at their event, they can be just as effective running a leg of a 4x400 meter relay, 1500 meters and sometimes the 3k if needed.

Wolf: It depends on how the athlete attacks the event. For athletes with a greater distance background, aerobic is a larger percentage of training. For those who come at 800 meters from a pure track background, the anaerobic is emphasized to the largest degree possible.

Franks: I am not sure I agree with those percentages. I believe that the percentages of aerobic and anaerobic contribution are much closer to 50/50, although I do believe that it depends on the athlete and their muscle fiber make up. I do emphasize training both energy systems continuously all year. In saying that, there is a much higher emphasis on each at different times of the year. I look at both energy systems as two parts. The aerobic part I look at as aerobic efficiency (how much oxygen I can use) and aerobic power (how much oxygen I can move). These two things definitely work together, but at certain times of the year are focused on separately (or at least one side of that equation is focused on much more). Anaerobically, I look at max velocity speed and speed endurance/lactate tolerance/buffering capacity. Max velocity is in the mix almost year round, even in the “off season.” Not a primary focus at all, but we will at least touch on it in some form, like short hill sprints (6-8 seconds) at least one day every two weeks. The aerobic side we work efficiency to power, so longer and slower to shorter and faster, while the anaerobic side we work shorter and faster to longer and sustained.

Newell: We use a balanced training approach to develop the Aerobic/Oxidative system, the Anaerobic/Glycolytic system (Lactic), and the ATP-CP system (Phosphagen). The majority of our work is the aerobic system for several reasons: energy system efficiencies, injury risk, room for development, strengths and weaknesses of student-athletes, and sustainability. The driving force and foundation behind our training is aerobic strength and endurance (The Engine), while using the anaerobic system to meet the necessary energy demands of the 400-800 meter event (refining the Engine with performance parts to with-

stand work at and above Anaerobic Lactic Threshold/Tolerance), and touching on CNS work and ATP-CP effort for increased power, speed development, and biomechanical efficiency (Making sure the wheels and body of the vehicle are moving and working smooth).

QUESTION 4: HOW IMPORTANT IS THE PURE SPEED COMPONENT IN TRAINING DESIGN?

Godfrey: We address speed (40m – 50m) once per week in the build-up to our competitive season. During the competitive season we do 150-meter reps once per week. This can be viewed as speed endurance; except we take a very conservative approach and use the 150-meter efforts as build-ups and typically only run the last couple reps fast.

McCurry: The pure speed component is certainly important. I use the phrase “relative speed” often, and what I mean by that is simply that efforts at all paces are in some manner relative to an athlete’s top speed. If someone can only run 50’s over 400 meters, it is going to be difficult for them to average 53’s for two laps....to put it simply. That 400-meter time is of course not completely determined by pure speed, but it’s a strong component. We believe heavily in strength training, plyometric work, and short sprint efforts. This is what we refer to as speed development to improve and refine pure speed in all middle distance athletes.

Burks: Pure speed is a cornerstone of our training plan. We include weekly wicket sprints, flying sprints, and short hill sprints for all distances 800-10,000 meters. I believe this supports mechanic and neuromuscular development, but also assists in injury prevention and training load management.

Wilk: Again, this one depends on the student-athlete. Some do it once per week, and some rarely hit that component in training. The more speed-oriented the runner is, the more I do it. The more aerobic-oriented they are, the less frequently we hit it.

Bonsey: I would say that in the recruiting process I look for people with good pure leg speed. The 800 takes a lot of talent, and if you don’t have the requisite talent, you won’t be that good. I am lucky to work with guys that naturally have good leg speed. We try

to improve it through the weight room and the Thursday strides, but we don’t put a ton of time into improving leg speed. With 18-22 year olds, they improve their speed through physical maturity.

Pigg: We involve our sprint coach and do wickets, buildups and eventually 40’s-60’s80’s-100’s with full recovery. It is a progression though the season but always present.

Brown: Simply put, less important than the overall balance of everything else. You either have it or you don’t. DNA doesn’t lie.

Wolf: Speed is a component we continue to emphasize more and more in our training plans. Regardless of whether the athlete is more of a traditional middle-distance runner, or more of a 400-800 meter runner, we continue to look for more and more opportunities to build speed into our plans.

Franks: Pure speed is a very important component. It isn’t the end all be all at 800 meters, but having more pure footspeed I would argue is never a bad thing for any track and field event. Having more speed reserve and being more efficient at faster velocities is very important and useful. Not to mention the strength gains and muscle fiber recruitment from doing pure speed training. It is also a great biomechanical activity (typically people run their most efficiently when they sprint) and coordination building activity.

Newell: Acceleration Development, Max Velocity, and Speed Endurance are of vital importance for the 800-meter studentathlete (as is the strength training and plyometrics to further develop speed and power). With that being said, pure speed is a small percentage of the overall training workload that we do. The last sentence is not to be confused with meaning a small percentage of importance. We designate one day a week on developing acceleration, max velocity, and speed endurance. We typically do all three on a Monday, after an easy day or rest day on Sunday. We like doing these sessions rested and fresh since they are high intensity stress sessions. I also follow up these sessions with an explosive plyometric/strength session to further develop the CNS.

QUESTION 5: WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER YOUR MAJOR TRAINING PRINCIPLES THAT YOU BASE YOUR TRAINING ON?

Godfrey: Most importantly, we emphasize rest and recovery. We know adaptation does not occur if we short-change our recovery. We know proper nutrition also plays a key role. Our goal is to build the strongest heart possible and build a better delivery system. To accomplish this we include lactate threshold, aerobic recovery, and speed and strength sessions throughout the year. During the pre-competitive and competitive seasons, we include VO2 efforts, speed endurance sessions, lactate threshold, aerobic recovery, and strength maintenance.

McCurry: 1. Train the athlete, not the event. 2. Engine AND Body. When I say engine AND body, I’m thinking about the running elements of training primarily to build a more robust engine, and the purpose of the non-run elements is to consistently build a stronger, more capable body around that engine. We use the race car analogy, meaning you can’t put a Ferrari engine in a Ford Festiva body. Or we explain it like there’s a reason NASCAR or F1 cars are different from cars out on the road. If you are going to have a massive engine, you need the right axles, tires, chassis, etc. to keep up with it. Strength and mobility work needs to parallel the running training load. 3. Consistent and efficient aerobic development work.

Burks: Most generally, throughout the entire group I coach, I maintain a focus on quality aerobic work throughout the year. For middle distance athletes in particular, I have seen the biggest jumps in performance align with jumps in aerobic capacity and ability to maintain higher training loads. Year-round sprinting is also a major training principle for me. We regularly use wickets, treadmill hills, and flying sprints to develop quality form/mechanics, strength, and speed. In my coaching, I generally try to make sure that we are consistently touching all the bases in training – quality aerobic work, anerobic efficiency, maximum speed, and general strength.

Wilk: I would say that I’m a relatively Jack Daniels-oriented coach and follow many of his training principles. This is more of a guideline rather than just following his book. I try to adjust things based on the training environment (especially since we train in the unique heat/humidity combo that is Miami). I have also focused heavily on where the student-athlete’s mind goes in training and how they execute reps. A K (1,000 meters)

repeat run consistently at 72” per 400 for a 3:00 versus a K repeat run in 70/73/37 are very different. I think that it’s important that they learn how to pace from feel and not just go out fast, and “get to the finish line.” The ability to do this generally translates well to being able to stay mentally focused, hang tough and finish races well.

Bonsey: I’ve been very lucky to work with some amazing 800 coaches like Pat Henner, Mike Smith, and Chris Miltenberg. Ron Helmer was also the director at Georgetown when I was an athlete. I have kind of just picked their brains and taken things from all of them that I thought were smart. Like I said earlier, we constantly want to improve their aerobic system and improve their leg speed. If we are doing both of those things consistently, then I think the race pace stuff comes together nicely. I am not the right guy to ask about training principles or the science of the sport. Thankfully, running isn’t overly complicated, and I’ve figured out what works for us.

Pigg: Five principles: 1. Don’t bury their talent. 2. Focus on late season. 3. Don’t burn matches too often or early. 4. Be healthy and hungry late in season. 5. Progression in all aspects.

Brown: At the junior college level, we specialize but also train well-rounded athletes (academically, athletically, socially) to the best of our abilities in order to increase recruiting options for them once they are finished here.

Wolf: For the athletes who do cross country, we are working on the strength and power they need to move during the middle of the race. For those who do not do cross country, the focus is on the speed and speed endurance necessary to run the race.

Franks: One of my major training principles is that endurance work does NOT kill speed. Endurance training only kills speed if it takes the place of speed training. Both endurance and speed can be built (and maintained) at the same time. Another is that every athlete is a different biological unit, and no two athletes are exactly the same. So, when you design training for an individual athlete, you try to put good athletes together as much as possible, but sometimes they need to be doing some different things. Always play to an athlete’s strengths, while addressing their weaknesses.

Newell: Before I start: Design with Science, Apply with Common sense. Things I think about: Who, What, How, When, Why? Who are we training (student-athletes)? What are we training the student-athlete to do (event)? How are we going to get the student-athlete to achieve their goal in the event (training)? When is the goal timeline that we must get the student-athlete to their event goal with the appropriate training (season)? Why are we doing the things we do with our decisions, thinking, and behaviors? Other things I stress: Get/ Stay Healthy. Get/ Stay Consistent (at the highest level possible). Get/ Stay Sustainable. Train Within Yourself and Compete Beyond Yourself. We lean into a balanced periodization system that develops all the important variables to training and racing the 800 meters. Balanced does NOT mean equal parts. Balanced means we use all the necessary variables needed for success for a given student-athlete in a given event at all times. We start broad and general and progress towards narrow and specific. As the season progresses, more specific training receives greater emphasis. We use aerobic strength and endurance as the driving foundation, anaerobic bouts to

stress event specific energy demands, and ATP-CP and CNS work to emphasize power, speed, and biomechanics. We stay consistent with situational adjustments through the training cycle as adaptations are made. We are touching on a variety of different training variables throughout the training cycle, progressing all systems and variables as the season progresses, with a tapering off the last 10-14 days before the peak event. We use Endurance Runs (Steady and Recovery), Long Runs (Steady and Progressive), Tempo Runs, LT Intervals, VO2 Intervals, 1500 meter RP Repetitions, 800 meter RP Repetitions, 200-400m RP Repetitions,1020m Accelerations, 20-30m Max Velocity, 80-120m Speed Endurance.

QUESTION 6: CAN YOU GIVE US A PEEK AT SOME OF YOUR FAVORITE WORKOUTS, OR A WORKOUT THAT TELLS YOU YOUR ATHLETE IS READY TO “RUN FAST.” EXPLAIN.

Godfrey: Over the years we have done 3 x 4 x 200m with 1’ rest b/w reps and 3’ b/w sets to help gauge some race readiness. Most of the 800-meter athletes I’ve coached enjoy running fast and 200-meter reps help develop race rhythm. We can manipulate this session and

do less rest b/w reps and longer rest b/w sets if we want higher levels of acidity. I think this is appropriate at times. But mostly, I like this session during the season to see how comfortable the athletes can be and still run fast.

McCurry: I’m pretty averse to putting too much emphasis on the big, event specific sessions. I focus more on how an athlete is progressing in their foundational work. Are we seeing pace at threshold effort come down over time? Are we seeing the same with VO2 effort? Are they moving more efficiently and easier at and below 800 meter effort? That being said, I love work like 2-3 x 500m-600m near max to maximum with a 15 minute jog between. I think that calluses the athlete up really well for race efforts. Understand though, we do this VERY rarely with a collegiate athlete. These workouts look shiny, so everyone loves them, but they make their hay on the long run, the threshold reps, the speed development, etc. that we do EVERY week.

Burks: For our speed- based 800 runners, threshold repeats of 400-800 meters are a staple throughout the season. Faster ses-

sions that highlight race readiness include 1. 2x(300-200) w/ 200 walk recovery and 8:00 set recovery, faster than 800-meter race pace. 2. 400-300-200 – 400-200-200 with the second set faster than the first set. 3. 600-400300-200-200 going from mile-pace to faster than 800-pace w/ 3:00 recovery throughout. Each of the above workouts were done one week out from PR races for various athletes. Many of our most intense workouts include 2 sets of 2-3 reps of 200 to 400 meters with substantial recovery between the sets. The second set is typically faster than the first set, with the direction being to run aggressively through fatigue.

Wilk: One of my favorite 800-meter race specific workouts is 4x400 meter repeat. Generally, I have the men do it with about 5’, 6’ and 7-8’ recoveries between reps and women with about 6’, 7’ and 8-9’ between reps. This one is easy to give a false sense of accomplishment if they don’t push the first three reps and just blast the last rep. Closing a workout in a 49-50” or 55-56” is well and good, but the key is being able to close hard with fatigue in your legs. I generally tell them to treat the third rep like it’s their last one, then to just deal with the consequences of it afterward. If they sandbag the first few (the third one in particular), this workout isn’t race specific and they don’t get the full benefit.

Bonsey: One we come back to often is 2x 4x 200. Generally, that is run at opening lap 800 pace. If someone can do that and run faster on the last 200, then I know they are fit. If we have a long time to recover, then 2x 200400-200. Short rest in the set and a lot of rest between sets. Same as the above workout: If they are strong enough to run fast on the last 200, I know they are ready. We don’t do a ton of these super difficult sessions, but when we do they know they need to bring it.

Pigg: 4x 400 with 5:00 rest at goal pace. When a woman can run sub-60 for all 4 and close strong, she is close to 2:00 shape.

Brown: Nothing special or new here, but two workouts essentially. Aerobically, 15 x 300 meters, which is done continuously (100m jog recovery) – which is honestly more of a tempo run. This shows me they are both aerobically and mentally fit for whatever is to come next in our training. Broken 800s are a favorite, with 400 meters at the target pace of your first quarter of the 800-meter race,

followed by a 200-meter jog--and then a hard 200 meters. Can the athlete do multiple reps of this before breaking down? Practice heroes can run one, but can they keep going?

Wolf: We do variations of 200s with 2-2:30 rest. Early season has more volume and is slower, and the later season is faster and has lower volume (reps). These end up being largely aerobic workouts, and then toward the end of the season, they are a good race prep. For example, if you run 8 x 200 in 28, (or 7 in 27), you are at a pretty good first 400 pace, and this is helpful for the athletes to learn what that pace feels like.