By Shauna Dobbie

Gentle readers, Old Man Winter is on his way toward us, which can mean only one thing: Christmas (or Hanukkah or Kwanza) is on its way. Just when you’ve hung up your rake it is time to start getting ready for the season.

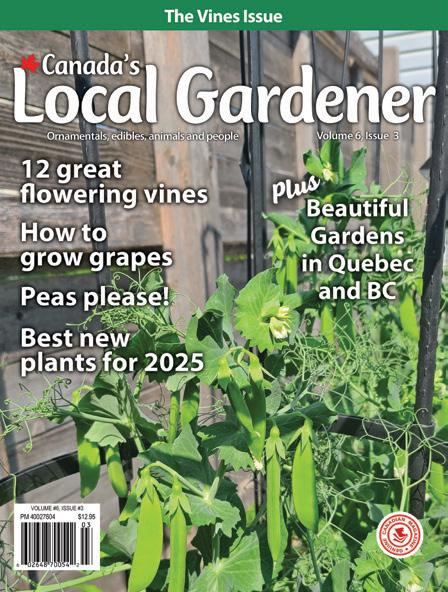

We aim to be ever helpful here at Canada’s Local Gardener, so here is an idea: why don’t you get a gardener in your life a subscription to the magazine?

If in the past you have eschewed the possibility because you would have nothing to wrap and put under the tree, we can fix that. If you order a gift subscription by December 1, 2025, we will send you:

• a free copy of the current issue

• a packet of Seaweed Magic, our special nutrient booster, that mixes into 250 litres

• a Christmas card

You can wrap these all up with a pretty bow and present them to your favourite gardener on the big day.

All these items add up to a value of about $70, and you get them for a loved one for the price of a subscription: just $35.85. (Of course, you could also get the deal with a two-year subscription for $68.08, or three-year for $98.40.)

A little about Seaweed Magic

Seaweed Magic is one of those simple but powerful additions to your gardening routine that makes a visible difference. Made from Atlantic seaweed harvested from the coast of Canada, it is packed with natural growth stimulants, amino acids, and micronutrients that help plants reach their full potential. I like it because it doesn’t just push growth in one direction the way chemical fertilizers often do. Instead, it strengthens the whole plant – roots, stems, leaves, and flowers – so they can better resist stress, drought, and disease. The result is healthier plants, more blooms, and tastier vegetables without the worry of synthetic additives.

What really sets Seaweed Magic apart is its versatility. You can use it on seedlings to give them a strong start, on established perennials to encourage abundant flowering, or on vegetables to boost yield and flavour. I find it especially valuable in the Canadian garden, where we ask a lot from our plants in a short growing season. A little Sea Magic in the watering translates to stronger growth and more resilience when the weather turns against us. It’s easy, organic, and economical; the small packet we send mixes up into gallons of plant tonic that truly delivers.

Order online at http://bit.ly/4gtZztP; follow the prompts to the winter gift promo. Or call Karl at 204-940-2700.

Find additional content online with your smartphone or tablet whenever you spot a QR code accompanying an article. Scan the QR code where you see it throughout the magazine. Enjoy the video, picture or article! Alternatively, you can type in the url beneath the QR code.

Follow us online www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @LocalGardenerLiving

Published by Pegasus Publications Inc.

President Dorothy Dobbie dorothy@pegasuspublications.net

Editor & Publisher Shauna Dobbie shauna@pegasuspublications.net

Art Direction & Layout Karl Thomsen karl@pegasuspublications.net

Contributors

Steven Biggs, Sarah Coulber, Dorothy Dobbie, Shauna Dobbie, Robert Pavlis, John Rutten, Tania Scott, Kate Spirgen and Nancy Zomer.

Editorial Advisory Board

Greg Auton, John Barrett, Todd Boland, Darryl Cheng, Ben Cullen, Mario Doiron, Michel Gauthier, Mathieu Hodgson, Jan Pedersen, Stephanie Rose, Michael Rosen, Aldona Satterthwaite and Trudy Watt.

P rint Advertising

Gord Gage • 204-940-2701 gord.gage@pegasuspublications.net

Marketing Manager Micaela Soto • 204-940-2702 micaela@pegasuspublications.net

Subscriptions

Write, email or call Canada’s Local Gardener P.O. Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9 Phone: 204-940-2700 info@pegasuspublications.net

One year (four issues): $35.85

Two years (eight issues): $68.08

Three years (twelve issues): $98.40

Single copy: $12.95

Plus applicable taxes.

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Circulation Department

Pegasus Publications Inc. PO Box 47040, RPO Marion Winnipeg, MB R2H 3G9

Canadian Publications mail product Sales agreement #40027604 ISSN 2563-6391

CANADA’S LOCAL GARDENER is published four times annually by Pegasus Publications Inc. It is regularly available to purchase at newsstands and retail locations throughout Canada or by subscription. Visa, and American Express accepted. Publisher buys all editorial rights and reserves the right to republish any material purchased. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright Pegasus Publications Inc.

back issues as far back as Volume 2 Issue 4! https://order.emags.com/ca_local_gardener_digital the QR code to the right to access our issues at a special reduced rate!

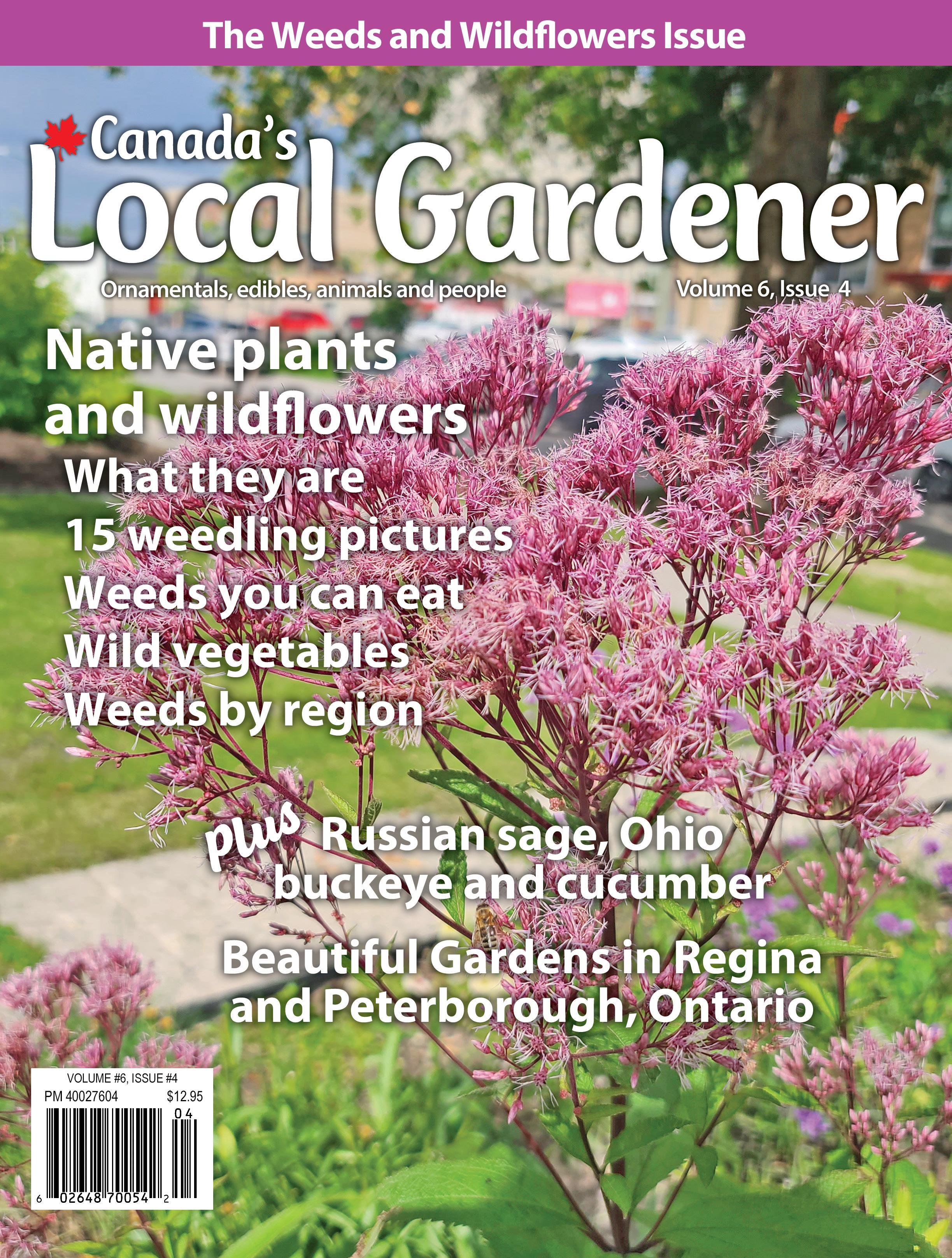

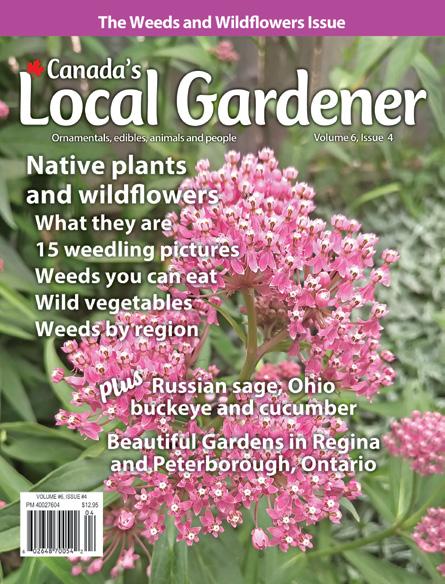

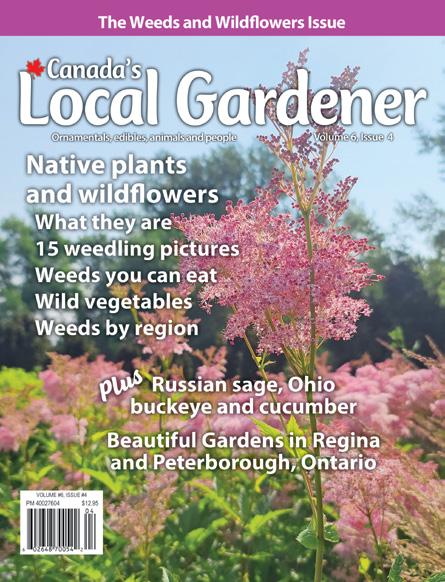

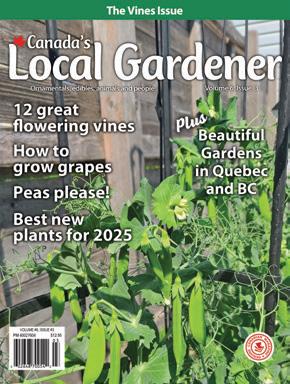

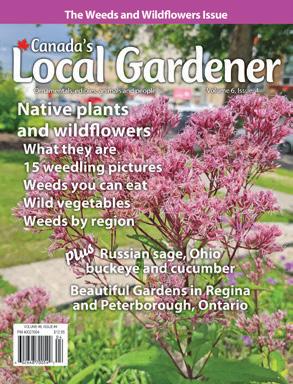

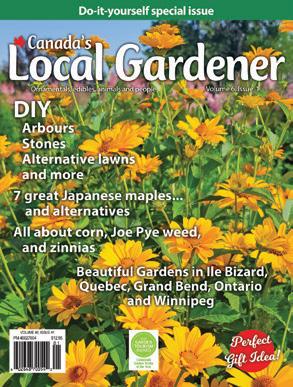

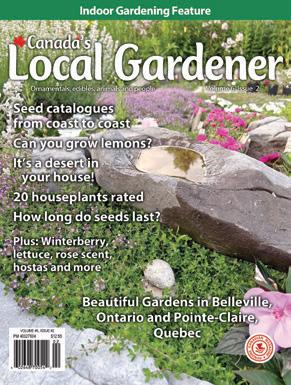

Choosing a cover image is a lot harder than one might think. It needs to be in a vertical orientation. It needs to have the focus slightly down and to the right to account for the masthead (title) and slugs (promotional bits that say what’s in the magazine).

For this issue, we knew we should feature something wild and probably native to Canada.

I came up with these three from our files, and I love each one. The milkweed is clear and in a great position and the asters are like a field of stars. The problem is that they both have a hole in the centre, a dead spot where nothing is growing.

Without the slugs, they don’t look too bad, but add the slugs and the dead spot is all you can see.

The filipendula is a lovely image too, taken on a clear sunny day at the International Peace Garden. The problem here is that the main flower is way too tall.

In frustration, I went out and snapped the picture of the Joe Pye weed in my front garden and I quite like it. I hope you do too!

Have you missed us? Have no fear - catch up on our recent back issues on our digital newstand at a reduced rate – including:

Purchase a single digital copy of any issue of Canada’s Local Gardener from Volume 2 Issue 4 and up now available! Scan the QR code or go to https://order.emags.com/ca_local_gardener_digital

Story by Shauna Dobbie

In recent years, wildfires have grown in both frequency and severity across many parts of Canada. British Columbia, Alberta and Manitoba are the most recent provinces to struggle through the summer months and all Canadians have been subjected to smoke in the air.

Gardeners not directly in the line of danger are hit more than we may realize. Aside from difficulty breathing in the garden on smoky days, our plants may be affected. The closer you are to fires, the worse the effects are. When smoke from wildfires fills the air, it reduces the amount of sunlight that reaches plants. This can slow down photosynthesis, especially in vegetables, annual flowers, and other fast-growing plants. During periods of heavy smoke, gardeners may notice reduced growth, wilting, or leaf drop. Chronic smoke exposure can also lead to lower yields in fruit-

ing crops like tomatoes, peppers, and squash.

Falling ash may seem like free fertilizer, since it does contain calcium, potassium, and magnesium, but its effects on soil are mixed. In small amounts, ash can help neutralize acidic soils, but in excess, it can cause imbalances. High pH can make nutrients like iron and phosphorus less available to plants.

In some cases, wildfire-affected soil becomes hydrophobic – it repels water. This is more common in forested areas where intense heat burns off organic matter. For gardeners on the fringes of wildfire zones, this may mean reduced infiltration of rainfall or irrigation, leading to drought stress. Mulching and amending the soil with compost can help rebuild structure and moisture retention.

Like people, plants under stress are more susceptible to disease. Smoke exposure, ash, and irregular watering

due to fire restrictions can all lower a plant’s natural defences. Powdery mildew, root rot, and pest infestations often appear in gardens that have gone through prolonged smoke exposure.

Fires are part of a larger climate trend that includes drought, intense storms, and earlier springs. Many gardeners are finding that their hardiness zones are shifting, their frost dates are less predictable, and traditional planting times need adjusting. Smoke events can also cool daytime temperatures while trapping heat at night, creating confusing signals for flowering and fruiting plants.

While gardeners are a resilient bunch, wildfire seasons are forcing a new level of adaptation. Whether it's using more resilient planting strategies, increasing soil testing, or advocating for better land management practices, the intersection of fire and food has never been clearer. P

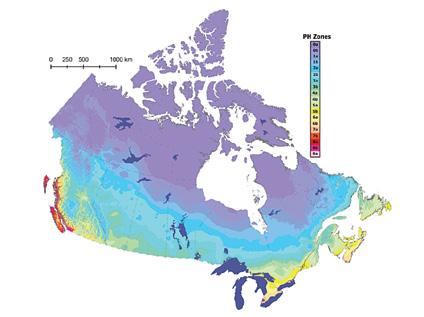

Gardeners may notice some big changes on the newly updated Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone Map. Based on climate data from 1991 to 2020, the new version shows clear signs of warming across much of the country. Some regions, particularly in British Columbia and parts of Alberta, have shifted by up to two full zones. Victoria, for example, has moved from Zone 7b to 9a since the year 2000. That change puts it closer to northern California’s climate than to most of Canada. The Vancouver area is now showing Zone 9a as well.

The new map, developed by scientists at the National Research Council, uses seven climate variables, including minimum winter temperature, frostfree days, precipitation, snow cover and wind. Unlike the USDA zone map used in the United States, which is based only on extreme minimum temperatures, Canada’s system takes a broader range of weather conditions into account.

Dan McKenney and John Pedlar, who led the project, explained that most of the country saw zone changes of about half to one full zone. The most dramatic changes occurred in remote parts of the west, though smaller shifts were seen throughout southern Canada.

For Prairie gardeners hoping their hardiness zone has improved, the news may be disappointing. Winnipeg remains a solid Zone 3b, with no immediate sign of moving to Zone 4. Even with consistent snow cover in winter, the extreme lows of -35 Celsius or colder still limit what can reliably overwinter.

The new maps are not just for gardeners. They are used in agriculture, forestry, insurance, and ecology. Certain invasive pests, such as the hemlock woolly adelgid, are known to be limited by specific climate thresholds. Hardiness zone data helps track where such pests might take hold.

The NRC’s online tool at planthardiness.gc.ca allows users to look up the current zone for their municipality, compare it to past data, and even explore plant-specific habitat maps based on climate profiles.

Printable PDFs and posters are in the works and will soon be available through the website.

Whether you are growing roses, vegetables or trees, the new maps are a useful guide. But McKenney and Pedlar remind gardeners that local microclimates, snow depth, soil and personal care also make a difference. Gardening is still an experiment, and one that is gradually shifting with the climate. P

Anew community garden, Jardins du monde & des Premières Nations, is transforming a once vacant lot in Montreal’s Plateau Mont Royal neighbourhood into a green space centred on Indigenous traditions. The project, a collaboration between local residents and Indigenous leaders, highlights traditional cultivation methods while promoting social inclusion.

At its heart is a Three Sisters garden,

featuring corn, beans, and squash planted together to support one another’s growth. Surrounding plots include sacred Indigenous plants such as sage, sweetgrass, cedar, and tobacco. Additional beds feature vegetables from the diverse cultural backgrounds of the community’s residents.

The garden aims to serve as both a teaching tool and a space for reconciliation, honouring the unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation while

encouraging dialogue between Indigenous and non Indigenous Montrealers.

Organizers hope the garden will become a model for other urban green spaces that link community building, ecological stewardship, and Indigenous knowledge. P

Check out https://espacepourlavie.ca/en/ first-nations-garden for more information, or scan the QR code above.

In late July 2025, the PEI Invasive Species Council reported a rapidly expanding infestation of wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) on Prince Edward Island. Initially underestimated, the scale of the problem surged after a wave of public reports. The plant’s sap can cause serious phototoxic reactions, including burns and blisters. If you get it in your eyes, it can cause temporary blindness.

The bright yellow, flat-topped flower clusters and serrated leaves atop a grooved green stem are key identification traits. The flowers are very similar to dill, but the leaves are quite different. Once contacted, sap needs immediate washing with soap and cold water, and sun exposure should be avoided for at least 48 hours.

Wild parsnip is the same species as parsnip you grow in your vegetable garden. It’s a biennial, so it develops the delicious taproot the first year and flowers in the second year. As gardeners, we tend to dig up the roots in the first year, and we tend not to get the sap, which the roots don’t contain, on us. (Though if you do, this will also give you blisters when exposed to sunlight.) When the plant is left to its own devices, it gets big and rangy, and it is often mown, releasing sap.

Local health and natural resources authorities in Ontario, Nova Scotia, BC and PEI issued warnings, urging residents to report sightings and protect growers and outdoor workers. Disposal guidance advises bagging plants, sealing them in direct sunlight for at least a week, and avoiding composting or burning to prevent toxic fumes or seed spread.

Although giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) boasts a far smaller presence on PEI, it remains a significant concern, particularly due to its severe sap-caused skin injuries, ecological dominance, and high seed output.

Often reaching 10 feet and taller, giant hogweed features a hollow green stem with random reddish-purple blotches and coarse hairs, and enormous compound leaves up to 3 feet wide. Its white umbrella-shaped flower clusters can spread up to 3 feet in diameter. A single plant can produce 10,000 to 50,000 seeds in late summer.

Of the two plants, wild parsnip is found throughout southern Canada while giant hogweed is rare or absent in the Prairies and northern Canada. Giant hogweed has a nastier bite, but really, any painful reaction is not good. P

Story by Kate Spirgen

Each spring, you’re faced with the difficult decision of which plants to add to your garden. When the weather turns warmer and you head to your local garden centre, you’re greeted with greenhouses full of options. And while you likely recognize tried and true favourites, there are also some new varieties that you’ve never seen before.

Those new plants are the result of years and years of breeding, discovery, trialing, testing and perfecting that culminate in introductions that will beautify your green space all season. But how exactly do breeders introduce the new options you see each year?

Let’s take a look at how the plant development process at Proven Winners works.

Breeding a new variety

For more than 30 years, Proven Winners has worked with plant breeders from all over the world to bring new and exciting options to you each spring. While the new plants you see on retail benches sometimes come from a natural mutation, or even the discovery of an entirely new plant in the wild, they’re most often the result of a more purposeful procedure.

Plant breeding is a meticulous process in which breeders choose plants with the characteristics they’re looking for either in the wild or from their own greenhouses. They then cross-pollinate them, harvest the seeds and grow the cross of the two plant parents.

From that first crop of seedlings, breeders will choose the healthiest and most attractive young plants to watch how their experiment has turned out in the first few life cycles. If they’re happy with the results so far, they’ll continue to monitor results for several years to make sure the cross is viable.

Graduating from the greenhouse

Once the breeder is confident that their cross is successful, they begin the trialing and screening process where only a small selection of the very best performers move on to the next stage. That can be as few as a handful or several hundred out of thousands, depending on how well the seedlings perform. For annuals, this process will take place over a number of years in the greenhouse, while perennials and shrubs are monitored throughout their

life cycle in the field.

Once the breeder has narrowed down the seedlings to the very best few, they’ll pass them along to a brand like Proven Winners for trialing. Our propagators trial plants in a variety of locations and climates for years to ensure that their garden performance lives up to our standards before introducing them for sale to gardeners like you. Annuals will move through the process in four to six years since they have a shorter life cycle, but perennials can take eight to 15 years, and shrubs can take 10 to 12 years to go from initial cross to first sale.

Not only do we consider the plant’s appearance, we look at heat, drought and cold tolerance, habit, size and more to make sure gardeners all over the country can be successful with every plant we sell. And to make sure that each plant is worthy of the Proven Winners name, we test propagation and uniformity in our greenhouses. That assures growers that every crop of each variety will perform the same. We even test each new variety to make sure it can stand up to the rigors of shipping. So, from start to finish, quality is our top priority.

Proven Winners is constantly evaluating potential new plants in our facilities alongside varieties that have already been introduced to see how they compare. Expert growers keep an eye on the newcomers, evaluating their growth and tossing out any seedlings that are underperforming. If they are consistently living up to the Proven Winners standards year after year in trials, they’ll be given an internal nickname and we’ll begin building

stock for future sales. Once that stock is built, and a new variety is ready to be introduced, it will be given its official name.

It’s a vigorous process and only 2 per cent of plants we trial ever make it to stores. But you can rest assured that every single plant in a Proven Winners container was the result of years of research, trialing and growing.

Bringing the best to your garden

Even after a plant makes it to your garden centre, the quality control process never stops. Proven Winners is always looking for ways to enhance gardeners’ favourite varieties, which leads to ‘improved’ varieties or even entirely new ones. From improved branching for fuller plants to better disease resistance, there are many ways to improve on a great plant. And often, we add new colours, modified habits and various sizes to series of plants to offer more options and applications.

And that’s how new plants are invented and grown! For more than 30 years, Proven Winners plants sold in Canada have been grown by two propagators: Nordic Nurseries in Abbotsford, British Columbia, and Ed Sobkowich Greenhouses in Grimsby, Ontario. From greenhouses to garden centres, the Proven Winners plants you buy in Canada are Canadian grown for Canadian gardens.

In fact, 98% of the money you spend on Proven Winners plants stays right here in Canada. Learn more about our commitment to supporting Canadian growers, garden centres and gardeners at provenwinners.com/Canada. P

Kate Spirgen is the Marketing Communications Manager at Proven Winners.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Russian sage (formerly Perovskia atriplicifolia, now Salvia yangii) is a plant that looks as though it belongs in an aristocrat’s garden but behaves like it was born for the back forty. With its feathery silver foliage and clouds of lavender-blue flowers, it brings elegance to a border, yet it thrives on conditions that would make many perennials sulk. This long-blooming, drought-tolerant plant is one of the easiest ways to add late-season colour and movement to the garden.

Russian sage is hardy to about Zone 4, so it can handle most Canadian climates, including prairie winters if protected from heavy snow and wind. It is equally tolerant of heat, standing strong through long, hot summers.

Plant features

Growing three to four feet tall, Russian sage forms upright, shrubby clumps topped with airy sprays of

purple flowers from midsummer well into autumn. The finely cut, silvery leaves are aromatic when brushed, adding a pleasant scent. Viewed en masse, the flowers create a soft, hazy look that moves beautifully in the breeze.

One of the few criticisms of Russian sage is its tendency to flop by late summer. The best way to keep it upright is to cut it back hard in spring before the buds form to about 6 or 8 inches, which encourages strong new stems. You will get a later bloom, but it will be more upright and denser.

Planting it in full sun, with poor soil rather than rich, also ensures sturdier growth. Overwatering and fertilizer should be avoided, since both make the plant grow lush but weak. Each plant needs about three feet of space around it so it can grow without competing for light, and if it still sprawls you can tuck it among ornamental grasses or other sturdy companions to give it a natural support.

Russian sage is at its best in full sun and lean, welldrained soil. Sandy or gravelly ground is ideal, but it adapts to clay provided it does not sit in water. Too much richness or shade results in weak, floppy growth. Once established, it is highly drought tolerant, making it an excellent choice for prairie gardens, xeriscaping, or anywhere a low-maintenance perennial is desired.

If you’re gardening in a rainier part of the country, this plant can still be grown successfully, but it needs a little help to mimic the dry, gravelly slopes of its native home. The most important thing is drainage. Heavy clay soils that stay wet through winter are its downfall, often leading to crown rot. To prevent this, amend the soil with gravel and compost before planting, or plant it on a slope or in a raised bed where water runs off quickly. A wide planting hole filled with a gritty mix helps keep roots dry, especially around the crown.

Another trick is to avoid mulching right up to the base. Organic mulches hold moisture, which is helpful for many perennials, but not for Russian sage. If you like the look of mulch, use a thin layer of gravel or stone instead, which keeps the roots cooler while allowing water to drain away.

Spacing also becomes even more important in wetter climates. Giving each plant ample room on all sides ensures good air circulation, which helps prevent mildew in damp summers. With those adjustments, even in the Maritimes or the Lower Mainland of BC, Russian sage can be coaxed to perform beautifully.

Care and maintenance

Russian sage is remarkably undemanding. Beyond the spring pruning and perhaps a light midsummer shaping, it needs little care. It does not require fertilizer, and once established, it can be left alone through dry spells. Deer and rabbits usually ignore it, and its aromatic foliage helps deter browsing.

Part of Russian sage’s appeal is its toughness. It is seldom troubled by pests or disease. Powdery mildew can appear if air circulation is poor, but this is rare.

Crown rot may occur in heavy, poorly drained soil, especially in wet winters. Keeping the plant in dry, well-drained conditions prevents almost all problems. Landscape use

Few perennials provide such long-lasting colour with so little effort. Russian sage looks particularly striking in drifts, where its hazy flowers create a soft veil over brighter companions such as rudbeckias, echinaceas, and daylilies. It also pairs well with ornamental grasses, which lend both structure and support. Pollinators, especially bees, love it, making it a valuable addition to wildlife-friendly gardens.

‘Blue Spire’ remains the most widely available and celebrated cultivar. It’s thought to be a robust hybrid with deep blue blossoms and growing up to about 4 feet tall. It has earned the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit, the garden equivalent of a standing ovation. It’s also a popular staple in landscapes worldwide.

‘Blue Spritzer’ offers light lavender-blue flowers and a neat habit, typically reaching around 30 inches tall and 32 inches wide. It was one of the top-rated performers in the Chicago Botanic Garden trials.

‘Denim ’n Lace’ was named Proven Winners’ Perennial of the Year in 2020. It’s appreciated for its strong, upright stems, lacy sky-blue flowers held close together, and a more compact size of roughly 32 inches tall by 48 inches wide, which makes it less prone to flopping.

‘Little Lace’ delivers highly lobed foliage, a medium lavender-blue hue and grows to about 32 inches tall by 38 inches wide. It, too, earned an “excellent” rating in the Botanic Garden trials.

‘Filigran’, features delicately dissected, fern-like leaves and bright blue flowers on tall and elegant 2-to-3-foot spikes.

‘Little Spire’ has an especially compact form, about 2 feet in height.

‘Blue Steel’ is a vigorous cultivar with sturdy stems, silvery foliage, and violet-blue blooms. It is another shorter variety, reaching 18 to 24 inches. P

Russian sage often gets mistaken for lavender or catmint, and at first glance you can see why. All three wear the same silvery foliage and bear purple flowers, but their garden roles are quite different.

Lavender (Lavandula) is the perfume star of the trio, with tight spikes of blossoms that make their way into sachets and oils. It prefers the Mediterranean conditions of hot sun and sharply drained soil, and in much of Canada it can be tricky to overwinter reliably.

Catmint (Nepeta), on the other hand, is a cottage-garden

charmer. It mounds lower, usually one to two feet tall, and flowers earlier in the season, often sending up a second flush if cut back. Its fragrance is sweeter, too, and of course, cats sometimes make it their personal playground.

Russian sage is the big, airy cousin. It rises 2 to 5 feet with clouds of violet-blue flowers that carry the show long after catmint is finished and lavender is looking tired. More rugged than lavender and more statuesque than catmint, it fills in the hazy purple niche of the garden from midsummer right into fall.

To subscribe to Canada’s Local Gardener magazine or to give it as a gift scan the QR code below or go online to simplecirc.com/subscribe/canada-s-local-gardener

With each year of subscription you will receive 4 issues a year in print and digital. Or you can go for the digital only subscription.

Already have a subscription and need to renew, or need to update your personal information? Head over to Canada’s Local Gardener subscriber portal with your 9 digit account number (found above your name on the mailing label) and your postal code. Scan the QR code below or go online to simplecirc.com/subscriber_login/canadas-local-gardener

Or contact us directly and we can handle all your subscription orders and queries by phone at 204-940-2700, by email at info@pegasuspublications.net or by sending in the subscription form found in this magazine.

Check out 10 Neat Things, our free weekly newsletter by email. It’s full of fun and fascinating facts about all things gardening. Sign up today at localgardener.net/10-neat-things-enewsletter-registration-form

Keep in touch with us online www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @CanadasLocalGardener

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Few garden vegetables are as refreshing as a homegrown cucumber. Sliced into sandwiches, chopped into salads or turned into crisp pickles, cucumbers taste like summer. And while they thrive in heat, with a little planning they’re well within reach for gardeners from coast to coast, even in short-season areas. From seed, depending on the variety, they take 50 to 70 days above 21 Celsius to mature.

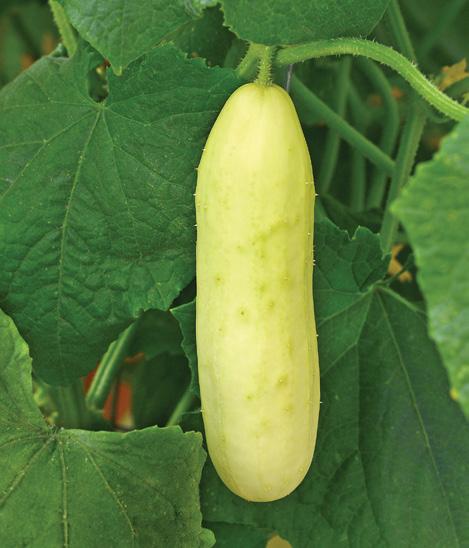

Cucumbers are broadly grouped into slicers (for fresh eating) and picklers (for preserving), though there are plenty of crossovers – pickling slicers and slicing picklers – that perform double duty in the garden and kitchen. A third category includes specialty types like English and lemon cucumbers.

Slicers

Slicing cucumbers are usually longer, smoother, and bred for fresh eating. Many modern slicers have white or no spines, and some, like the greenhouse types, are

completely spineless. These cucumbers often have thin skin and little to no bitterness – perfect for salads, sandwiches, and snacking.

If you’re gardening in a cooler region or short-season area, try compact slicers like ‘Diva’, ‘Salad Bush’, or ‘Patio Snacker’. These bush or semi-bush types are well-suited to containers and raised beds. For traditional full-size slicers, ‘Marketmore 76’ and ‘Early Fortune’ are reliable open-pollinated choices. For a smoother, seedless bite, look to long European types like ‘Tasty Green’ or ‘Telegraph Improved’ – best grown in greenhouses or under protection in northern areas.

Some slicers – like ‘Manny’ or ‘Beit Alpha’ – can also be pickled when young. These are sometimes called pickling slicers and are especially good for refrigerator or quick pickles.

Picklers

Pickling cucumbers are typically shorter and firmer

with bumpy skin and more prominent spines, often dark in colour. The spines don’t affect the preserved flavour but may indicate a thicker, more bitter skin in raw eating, which is why many picklers are peeled if eaten fresh.

Classic varieties like ‘National Pickling’, ‘Homemade Pickles’, and ‘Excelsior’ are bred for even size, blunt ends, and crisp texture. They hold up well in jars and ferment beautifully. Many also produce a high yield over a short period, which is helpful if you’re aiming to do all your canning at once.

Some pickling varieties, like ‘Picolino’ or ‘Green Light’, are tender and sweet enough to enjoy fresh. These are great for gardeners who want the option to snack or preserve from the same plant.

Sow after frost or start indoors

Cucumbers are heat-loving plants and will sulk or die in cold soil. Wait until at least two weeks after your last frost date to direct sow, or start them indoors three

Powdery mildew

Downy mildew

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV)

Angular leaf spot

to four weeks before planting out. The soil should be at least 18 Celsius for germination and 21 Celsius or warmer for good growth.

Transplant carefully. Cucumbers dislike root disturbance, though honestly, I’ve never lost one by transplanting. Nonetheless, sources recommend biodegradable pots if starting indoors. Harden them off for a few days before planting in the ground or containers.

Give them sun and shelter

Choose a sunny, sheltered spot, ideally with six to eight hours of direct sun daily. Cucumbers appreciate fertile, well-draining soil rich in compost or rotted manure. Raised beds warm up faster in spring, which cucumbers love.

Vining types need support, like a trellis or tomato cage, to keep fruit clean and save space. Bush types stay low but still appreciate mulch to retain moisture and keep weeds at bay.

Cucumbers are quick to suffer if disease takes hold. Here are the most common threats, how to spot them, and what to grow to stay ahead of trouble.

White, powdery coating on leaves, yellowing

Yellow angular leaf spots, grey fuzz underside

Stunted plants, mottled or curled leaves

Water-soaked leaf spots that tear into holes

Anthracnose Dark, sunken lesions on leaves and fruit

Prevention tips

• Trellis to improve airflow

• Mulch to reduce soil splash

• Water at the base to keep leaves dry

• Clean up debris to stop overwintering spores

• Rotate crops each year

Warm days, cool nights

Cool, damp weather

Spread by aphids

Wet foliage, poor air flow

Warm, wet weather

Marketmore 76, Vista, Salad Bush

Excelsior, Carmen, Picolino

Salad Bush, Vista, Homemade Pickles

Use rotation and copper sprays

Practise crop rotation

Feed and water consistently

Cucumbers are fast-growing and thirsty. Water deeply two to three times per week, more often in hot weather, aiming for moist but not soggy soil. Uneven watering can cause blossom-end rot (see side bar) or bitter fruit.

Feed with a vegetable fertilizer every few weeks or side-dress with compost or worm castings. Avoid highnitrogen fertilizers, which promote leafy growth at the expense of fruit.

Watch for pests and problems

Cucumber beetles, aphids, and powdery mildew are the main threats. Cover young plants with a floating row cover to deter insects, removing it when flowers appear for pollination. Encourage beneficial insects like lady beetles and lacewings, and practise crop rotation to avoid disease build-up in soil.

Mulch and trellising both help reduce splash-back

Bof soil-borne fungal spores. Water in the morning so leaves dry quickly.

Harvest early and often

Most cucumbers are ready to pick 50 to 65 days after seeding. Harvest when they’re firm, green, and just the right size for their type. If you wait too long, they turn bitter or seedy. Picking regularly encourages more fruit to form.

If you miss one and it grows into a zucchini-sized beast, remove it anyway. Overripe cucumbers signal the plant to slow down production.

If you’ve struggled in the past with bitter or stubby fruit, the culprit may be inconsistent watering or too little pollination. Try growing two or more plants to increase pollinator activity and keep moisture levels steady throughout the season.

With a bit of sun and steady care, cucumbers reward you with crunchy, juicy fruit all summer long. P

lossom end rot is most notorious in tomatoes, but it can also affect cucumbers, along with peppers, eggplants and zucchini. In cucumbers, it tends to show up as a soft, sunken, water-soaked area at the blossom end (opposite the stem). The damage often appears early in fruit development.

It occurs owing to the plant not getting enough calcium to build strong cell walls, especially in fastgrowing tissues like fruit. Even if the soil contains enough calcium, the plant won’t be able to move it effectively to the fruit if it’s under water stress. So no, adding an antacid to

the planting hole won’t prevent the problem.

Blossom end rot happens when:

1. Soil moisture fluctuates. This can happen from dry spells followed by heavy watering or rain.

2. Roots are damaged by transplanting, tilling, or pests.

3. Excess fertilizer is applied, especially high-nitrogen fertilizers that push leafy growth at the expense of root health).

4. The soil is too cold or compacted, limiting root function,

5. The plant is growing too fast, especially in hot weather or under stress.

To prevent blossom end rot:

1. Water regularly and deeply. Use mulch to maintain even moisture.

2. Avoid disturbing roots. Be gentle when weeding or transplanting.

3. Don’t over-fertilize. Stick to balanced fertilizers with moderate nitrogen.

4. Ensure good soil drainage. Raised beds and organic matter help.

Fixing blossom end rot after it appears isn’t possible for affected fruit but if the plant’s needs are met, future fruit should develop normally. Consistent care is the cure.

Aladdin Slicer 50

Artist Gherkin Pickler 48

Avenger Pickler 53

Babylon Slicer 60

Beit Alpha Slicer 55

Carmen Slicer 58

Mini, crisp cucumber for fresh eating; compact vine. High yield in small spaces.

Small, firm pickling cucumber with traditional gherkin shape.

High-yield pickling variety with disease resistance.

High-yielding greenhouse type with smooth skin and seedless fruit.

Quick harvest, perfect size for jars.

Tolerant of scab and mosaic virus.

Performs reliably in greenhouses.

Smooth, thin-skinned slicer, great for snacking fresh. Thin skin, no peeling required.

Seedless European-style cucumber for greenhouse growing. Greenhouse standard; high production.

Corentine Pickler 50 Extra early and seedless variety with 4 to 6 inch fruit.

Early Fortune Slicer 55

Excelsior Pickler 52

Green Light Slicer 45

Homemade Pickles Pickler 55

Lemon Slicer 70

Parthenocarpic; no pollination needed.

Heirloom with classic slicing shape and thin skin. Great old-fashioned flavour.

Blocky pickling cucumber bred for high density and firmness.

Small, seedless cucumber, tender skin and great for snacking.

Strong disease package and uniform size.

One of the earliest maturing varieties.

Blocky pickler with crisp texture and strong vines. Firm fruit that holds up in jars.

Round and sweet with yellow skin and never bitter. Very productive and easy to grow.

Manny Slicer 55 Early slicer with uniform fruit and high yield. Performs well in cool summers.

Marketmore 76 Slicer 67

Martini Slicer 57

Patio Snacker Slicer 50

Picolino Slicer 52

Straight Eight Slicer 63

Summer Dance Slicer 54

Tasty Emperor Slicer 60

Tasty Green Slicer 60

Tyria Slicer 60

Vista Pickler 50

Open-pollinated, reliable heirloom slicer for field growing. Dependable across Canada.

Unique white cucumber with mild flavour and tender skin.

Compact plant with full-sized cucumbers, perfect for containers.

Mini cucumber with very crisp, seedless fruit.

Popular heirloom slicer with classic shape and flavour.

Novelty colour for farmer’s markets.

Stays compact, ideal for patios.

Excellent for kids and lunchboxes.

Open-pollinated and easy to grow.

Crisp Japanese hybrid, smooth skin and great crunch. Excellent for slicing and salads.

Crisp, slightly spined slicer with high productivity.

Long, slender Japanese cucumber with sweet flavour.

European seedless type with smooth, straight fruit; greenhouse preferred.

Heat tolerant and attractive fruit.

Very few seeds, minimal bitterness.

Parthenocarpic; no pollination needed.

Crisp, uniform pickler with excellent disease resistance. Good for high-density planting.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

If ever there were a houseplant with stage presence, it’s Mimosa pudica. Brush your fingers lightly over its feathery leaves and it instantly collapses into itself, folding each leaflet and drooping its stems as though you’ve mortally offended it. Give it a few minutes, though, and it perks up again, carrying on as if nothing ever happened.

A shrinking violet by nature Native to Central and South America, Mimosa pudica is often called the sensitive plant, touch-menot, or shy plant. Its rapid response to touch is a survival trick: by suddenly wilting, it becomes less appealing to herbivores and more difficult for insects to settle on.

The secret lies in tiny swellings at the base of each leaflet and stem joint, which pump water in and out of cells to snap the leaves shut. It’s hydraulics, not nerves, though it looks like the plant has feelings.

Growing your own little drama queen

Mimosa pudica isn’t as forgiving as a pothos or a spider plant. It needs bright light, preferably a sunny windowsill, and warmth year-round. The soil should be kept moist but not soggy. Most gardeners grow it from seed, since it’s short-lived (often just one or two years) and rarely sold as a mature plant.

Fortunately, the seeds are quick

to sprout if you treat them right. Soak them overnight in warm water to soften the coat, or nick the surface gently with a nail file. Sow them about a quarter of an inch deep in a light, well-draining mix, keep the soil evenly moist, and give them a warm spot between 21 and 27 degrees Celsius. A clear cover over the seed tray helps with humidity until the seedlings emerge, usually within a week.

Once they’re up, uncover them and move them into bright light. With care, seedlings can be potted up individually, and if you’re lucky, by midsummer they’ll produce those whimsical pink, powder-puff flowers.

Scan me

Check out this link to see Mimosa pudica react to being touched.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Mimosa_Pudica.gif

Handle with restraint

While it’s tempting to show off its leaf-folding trick every time a guest drops by, too much touching will exhaust the plant. Think of it as a delicate performer who only shines when the spotlight is used sparingly. It’s also best kept away from children and pets, as it’s a little toxic if ingested.

Why it matters

Mimosa pudica is more than a parlour trick. It demonstrates that plants aren’t passive green statues; they sense and respond to the world around them in ways that surprise us. In fact, it’s been used in experiments since the 18th century to explore plant behaviour and memory. Not bad for a modest little tropical that just wants a sunny seat and a bit of attention on its own terms. P

Quick reflexes: The leaflets fold in less than a second when touched. Whole stems can droop within seconds.

Memory experiments: In the 19th century, scientists observed that Mimosa pudica “learns” not to close its leaves if a stimulus proves harmless, like repeated drops of water. Sensitive to more than touch:

It also reacts to heat, vibration, and even changes in light intensity.

Global traveller: Although native to the Americas, it has spread to tropical regions worldwide, often becoming weedy.

Short-lived beauty: Most plants only live a year or two, which is why they’re often grown fresh from seed each season.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

The Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) is an invasive species with a voracious appetite for more than 300 species of plants. Originally from Japan, the beetle was first detected in North America in New Jersey in 1916 and has been gradually expanding its range northward ever since. It is now a growing concern in several parts of Canada, especially in urban and agricultural settings where it can cause significant damage.

Adult Japanese beetles are easily recognized: about ½ an inch long, they have metallic green bodies and bronze wing covers. Their white tufts of hair arranged in patches along the sides and rear of their abdomen are a key identifying feature. The adult beetles emerge in late June and are active for six to eight weeks. Eggs are

laid in the soil, hatching into larvae (white grubs) that feed on plant roots, especially turf grass, throughout the summer and into autumn.

Japanese beetle grubs overwinter in the soil and are surprisingly cold-tolerant (see sidebar). Research indicates they can survive in soils where temperatures reach -10 Celsius. However, prolonged exposure below -10 Celsius, particularly in the upper layers of soil where grubs rest, can reduce survival. Snow cover acts as insulation, protecting them in colder regions. In bare ground with no insulating snow, grub mortality increases when soil temperatures drop below -8 Celsius.

The beetle is currently established in parts of southern Ontario and southern Quebec, especially around

It is known for its

An illustration of the year-long life cycle of the Japanese beetle. The white lines at the bottom mark the months of the year.

urban centres like Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. Infestations have also been found in small pockets of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and most recently in Vancouver, British Columbia. The Vancouver outbreak, first reported in 2017, triggered aggressive eradication efforts, including quarantine zones and restrictions on soil movement. As of 2024, beetles in Vancouver have been reduced but not eliminated.

The Prairie provinces have so far been largely spared, likely due to colder winter soil temperatures and less hospitable conditions. However, climate change and increased movement of plant material could shift the range westward.

Even without climate change, I have limited faith in the Japanese beetle being unable to invade Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Consider the lily leaf beetle, that red menace that was around a few years ago (and is making a comeback). It is supposed to die at -15 Celsius, so it should not overwinter on the Prairies, and yet it does.

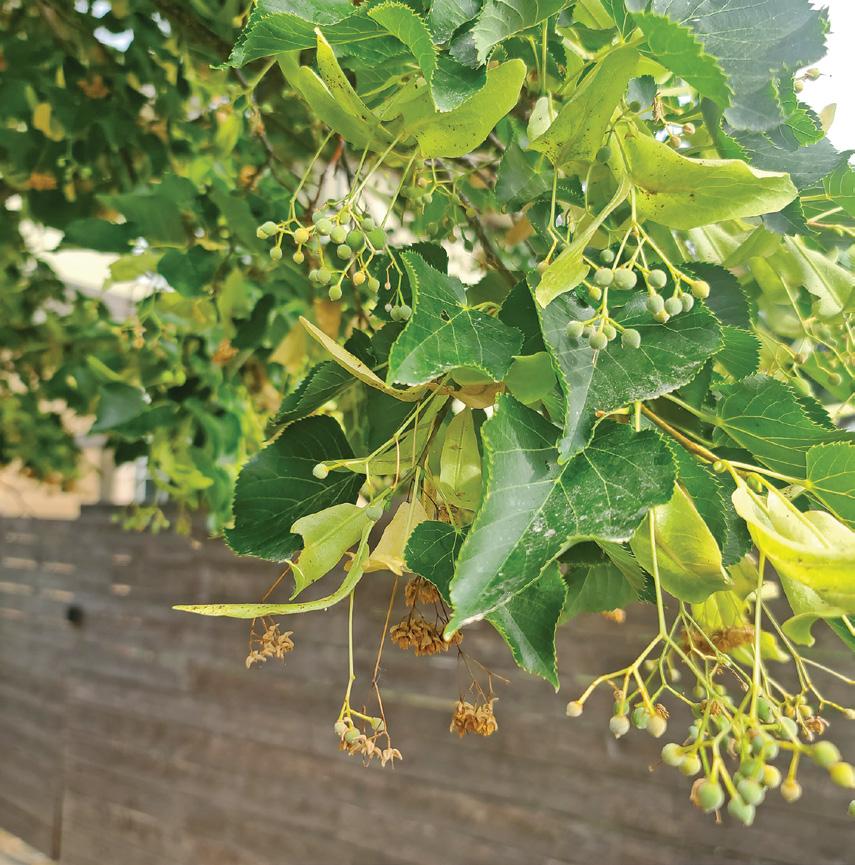

Damage and plant preferences

Adult beetles feed on foliage, flowers, and fruit, often skeletonizing leaves by consuming the tissue between veins. Favourites include roses, grapes, raspberries, apples, beans, linden trees, and many ornamental shrubs. Grubs, on the other hand, feed underground on the roots of turfgrass and pasture grasses, leading to dead patches of lawn that can be lifted like sod.

Looking ahead

As winters warm and snow cover becomes more

• Hand-picking in early morning or late evening can be effective in small gardens.

• Insecticidal soap and other contact sprays offer temporary relief.

• Traps are commercially available but should be used cautiously – they tend to attract more beetles than they capture and may worsen infestations if placed too close to susceptible plants.

Japanese beetle larvae

• Beneficial nematodes (such as Heterorhabditis bacteriophora) applied in late summer or early autumn can reduce grub populations.

• Healthy lawns that are aerated, dethatched, and not overwatered are more resilient to grub damage.

erratic, the spread of Japanese beetles across Canada may accelerate. Monitoring and early detection remain the best tools for limiting their establishment in new areas. Gardeners are advised to inspect new plants before bringing them home, avoid moving soil from infested areas, and report sightings to local agricultural authorities.

Japanese beetles may be small, but their impact is anything but. Keeping ahead of this pest requires awareness, vigilance, and community co-operation. P

If you have grubs in your lawn, they may be Japanese beetle grubs, but they may not. Chafers, another invasive species, produce grubs that feed on our turf roots, and we also have our native June beetles, also known as May beetles and June bugs.

Fortunately, the treatment for all grubs is roughly the same: keep your lawn healthy and apply beneficial nematodes (Heterorhabditis bacteriophora) in late July or August.

Province/territory Common grub species Japanese beetle present?

British Columbia European chafer, masked chafer, June beetles

Yes – Lower Mainland & Okanagan

Alberta June beetles (native) No

Saskatchewan June beetles (native) No

Manitoba June beetles (native) No

Ontario Japanese beetle, European chafer, June beetles

Quebec Japanese beetle, European chafer

New Brunswick Japanese beetle, some European chafer

Nova Scotia Japanese beetle, some European chafer

Prince Edward Island Japanese beetle

Yes – Southern Ontario widespread

Yes – Especially in the south

Yes – Localized populations

Yes – Spreading

Yes – Monitored closely

Newfoundland & Labrador Minimal grub pressure No

Territories Too cold for grub development No

Story by Shauna Dobbie

There are two Ohio buckeyes ( Aesculus glabra) in my front yard. At first I hated them. They seem to be in awkward spots – at least to me, as I think about putting in big ornamental gardens. But an arborist friend convinced me not to have them removed, and I’m thinking about them much more favourably now. They are uncommon trees in Winnipeg and they are healthy, so I think I’ll keep them.

According to a bit of reading, it is a native North American tree known for its early leaf-out, attractive palmate foliage, and upright spring flowers. “It makes a striking addition to a naturalized or wooded garden, particularly in moist, welldrained soil. Its modest size and quick growth are appealing to

gardeners seeking shade or seasonal interest,” says one source. Mine, however, have held steady at about 15 feet in heavy prairie clay for the three years we’ve lived here. I don’t know when they were planted but their shorter stature suggests they are adolescents.

Appearance and growing habit

Ohio buckeye grows as a small to medium deciduous tree, typically reaching 40 to 50 feet tall – though I suspect such heights are in more southern climes – with a rounded crown. Its distinctive compound leaves have five to seven leaflets arranged like fingers on a hand. They emerge early in spring and turn yellow-orange in autumn, but the tree often drops its foliage early in dry summers.

In mid to late spring, the tree produces upright clusters of pale yellow-green flowers that attract bees and hummingbirds. These are followed by leathery, slightly prickly capsules containing one to three glossy brown seeds known as “buckeyes”.

Site preferences and hardiness

Ohio buckeye is native to the Midwestern US and parts of southern Ontario, particularly within the Carolinian zone. It prefers rich, moist, slightly acidic soils and tolerates both full sun and partial shade. It is hardy to Zone 4, making it viable in many parts of southern Canada, particularly in protected or sheltered locations.

This tree grows naturally along riverbanks, in lowland woods, and

in areas with regular moisture. It does not perform as well in hot, dry, or heavily compacted urban conditions. Yet the trees persist in my almost-downtown yard.

Wildlife value and toxicity

Although the flowers provide early-season nectar for pollinators, its seeds and all other parts of the plant contain compounds such as aesculin and saponins, which are toxic to humans and many animals if consumed in quantity. Nonetheless, squirrels will gather the nuts.

I’m not worried about toxicity. Half the plants in most ornamental gardens contain some degree

of toxicity, including foxglove, daffodils, monkshood and lily of the valley – all of which are deadly toxic and very common. As with many garden favourites, caution is advised, but avoidance isn’t necessary.

Apparently, Ohio buckeye is best suited for larger gardens or naturalized settings where its leaf and fruit drop won’t be a nuisance. In my front yard, I’ve never noticed a problem with fruit drop, and most trees lose their leaves. I rake all leaves into the garden beds for winter and I haven’t really noticed

the buckeye leaves among them. Why plant Ohio buckeye?

The answer is… because you can. It is a lovely little tree, particularly in Manitoba and other parts of Canada where it is only marginally hardy. The spiky pods and palmate leaf arrangement are uncommon; only other Aesculus trees (different buckeyes and horse chestnuts) are similar. The upright flowers are also uncommon. Outside of Aesculus, catalpas are the most alike. Catalpa, of course, has drop-dead gorgeous flowers and huge foliage. Ohio buckeyes are a little less flamboyant, and that is their charm. P

Story by Sarah Coulber, Canadian Wildlife Federation

Pollinator gardens have become trendy in recent years, a key component of which are regionally native plants. But some people cringe at the idea of including native plants in their garden, the very word conjuring images of messy-looking yards that are an eyesore, if not a menace. In fact, the opposite is true. So many Canadian plants have gorgeous blooms and can be incorporated into any garden style, including the most formal of beds. Some native perennials are already popular, like Liatris spicata and shrubs like serviceberries, dogwoods and viburnums. As an added bonus, when situated with their ideal growing conditions, native plants often require less maintenance and are typically more pest and disease resistant.

But why the fuss over natives? Are they really that necessary?

The answer is a clear resounding yes.

We benefit from many services that wildlife provide, including pollination and pest control. But in many ways,

it starts with native plants as the flora and fauna of a particular region co-evolved over the millennia. In doing so, they developed a perfect relationship with one another, one which has been significantly disrupted by human activities which have not kept this important factor in mind.

With pollination, for instance, many pollinators are “specialists”. This means they have a specialized relationship with certain plants, without which they can not survive. We see this with butterflies and moths needing specific plants for their young, as with the monarch butterfly which needs milkweed for its caterpillars. No milkweed, no monarchs. In our time we have seen the Karner blue butterfly disappear from Canada because the lupine native to its area was eradicated due to human activity. But specialization applies to other animals, too, including many species of bees which are considered Canada’s most important and efficient pollinators (along with flies).

This has a ripple effect to the animals that rely on these

and other insects as food. Many adult birds eat insects but over 96 percent of North America’s terrestrial bird species depend on them when young, in particular soft-bodied and nutrient-dense caterpillars. And observations of various bird species making trips to their nest each day show that thousands of insects are needed to feed their young during that time. This continues for several days after the baby birds have fledged, while they follow parents around for food. And that’s not including how many insects are needed for the adults during this feeding marathon.

Because of this, having non-native trees in your garden reduces the chances of having insects and therefore having birds nest or visit, as they would have to travel farther for food, expending precious energy and leaving their young vulnerable for longer periods of time. In Nature’s Best Hope, researcher Douglas Tallamy tells of a study by one of his students comparing areas with mainly introduced plants versus native plants. Findings show there were less chickadees in areas with non-native plants and those that did nest had fewer eggs and those that hatched had lower survival rates.

Many non-native plants are also invasive, spreading into natural areas and pushing out natives, as with the commonly planted Norway maple, causing further disruption to ecosystems.

Nutrition is another factor to consider. One study compared fall berries of some native and non-native shrub species and found that the native shrubs had higher fat content compared to the high sugar content of the nonnatives. This can impact birds as they prepare for overwintering or migration.

In supporting our pollinators and ‘pest’ control allies, we ensure our garden veggies get pollinated, potential problems are kept in check and that our natural spaces can thrive. Our mental health also benefits, given the delight these animals bring with songs, colours and antics that grace our spaces. Sadly, many species in our communi-

ties have been declining at an alarming rate, as with an estimated three billion fewer birds in North America than just 50 years ago.

So, how wonderful to think that by simply adding some regionally native plants to our spaces we can help tip the scales and make a difference in the biodiversity on our property and in our community and therefore our wellbeing.

When shopping for natives, try to get plants from locally grown sources, rather than from seed that evolved in a different part of the country or continent. Also ensure the seed or plant wasn’t sprayed with neonicotinoids, a group of pesticides which can stay with the plant and travel into our soil and waterways, seriously harming or killing pollinators and other animals. Grow a diversity of plant types and species and include blooms from early spring until late fall. And while some cultivars can still be beneficial, do your research as many are less so; in fact, some become sterile, for example. Together, this will help support a myriad of wildlife all year long. Of course, we can still have some non-native favourites but keep these points in mind (as well as avoiding invasive species) when choosing plants.

At a time when many feel that problems are too big for them to tackle, this is a simple and attractive way for us to make a positive impact both near and far. We can help turn the tides on threats like habitat loss, pollution, pesticides and invasive plants by making our spaces not only beautiful but also beneficial. The natural habitat that once stood where our homes, schools and businesses now lie can, to some degree, once again be a viable and beautiful part of the ecosystems which we all need to thrive! P

Sarah Coulber is the Gardening for Wildlife Specialist with the Canadian Wildlife Federation.

You can visit GardeningForWildlife.ca for more information, resources and tools to help you enhance the biodiversity of your property.

Story by Shauna Dobbie

There’s something magical about stumbling across a patch of wildflowers. Whether it’s a delicate violet blooming in spring woodland shade or a swath of goldenrod glowing in late summer fields, wildflowers hold an effortless beauty. But not all wildflowers are as innocent as they look. Some are beloved natives; others are aggressive spreaders dressed in floral disguise. Knowing the difference matters not just for your garden, but for the broader ecosystem.

The term “wildflower” generally refers to any flowering plant that grows without intentional cultivation. That includes native plants – species that have evolved naturally in a region – and non-natives, which were introduced by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally. Some of these introduced plants behave themselves. Others do not.

Native versus non-native

Native wildflowers are adapted to local conditions. They support native pollinators and birds, and they usually fit into the ecological checks and balances of the region. Examples include:

• Canada anemone ( Anemone canadensis): spreads politely and supports native bees.

• Wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa): a magnet for hummingbirds and butterflies.

• Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium montanum): not a grass at all, but a tiny iris.

Non-native wildflowers, on the other hand, come from other continents or ecosystems. Some, like the cheerful bachelor’s button (Centaurea cyanus), behave well in garden beds. Others, like oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), can escape and outcompete native species in meadows and roadsides.

Aggressive versus well-mannered

Gardeners often describe unruly plants as invasive, but in ecological terms, that word has a specific meaning: it refers to non-native species that spread rapidly

and cause environmental harm. These are usually regulated or monitored by conservation authorities. In the home garden, though, it’s more helpful to think in terms of aggressive versus well-mannered behaviour.

Aggressive wildflowers, whether native or not, are those that spread quickly by seed, roots, or rhizomes, and tend to outcompete other plants in the bed. Think of them as over-enthusiastic guests: they may be beautiful, but they don’t always play nicely with their neighbours. Examples include:

• Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) – native and excellent for pollinators, but a space hog in small gardens.

• Soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) – charming but spreads persistently by rhizomes.

• Oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) – now common along roadsides; spreads quickly and often pushes out native flora.

Well-mannered wildflowers, on the other hand, grow in clumps or scatter gently without taking over. They’re easier to manage and more suitable for smaller spaces or mixed borders. Some reliable choices include:

• Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium montanum) – tidy and graceful, without crowding others.

• Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) – reseeds modestly and adds bold colour.

• Nodding onion ( Allium cernuum) – lovely blooms and clumping habit.

• Bachelor’s button (Centaurea cyanus) – pretty purple blooms that won’t take over.

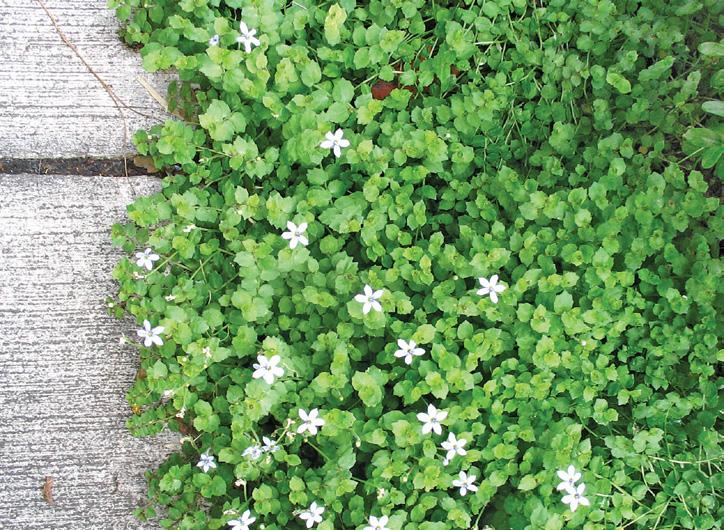

• Forget-me-not (Myosotis sylvatica) – a charming biennial with small, sky-blue flowers that self-seeds gently in moist, partly shaded areas.

Understanding the growth habits of each plant helps gardeners make choices that support both aesthetics and ecological harmony. Aggressive doesn’t always mean bad – it just means you need to keep an eye on it. P

If you’re looking to add wildflowers to your space, here’s how to do it responsibly: Go native when possible. Native species support local biodiversity and are more likely to thrive with less water and fertilizer.

Buy from reputable native plant

nurseries. Avoid seed mixes that don’t list exact species. “Wildflower mix” often includes invasive or unsuitable plants.

Think regionally. What’s native to southern Ontario may not be native to the Alberta foothills or the Acadian forest.

Control spreaders. Use physical blockage like root barriers – sheets of rigid plastic or fabric buried vertically in the soil – to contain underground runners. Limit irrigation for vigorous growers and deadhead plants to prevent unwanted reseeding.

You might be surprised at how much is out there.

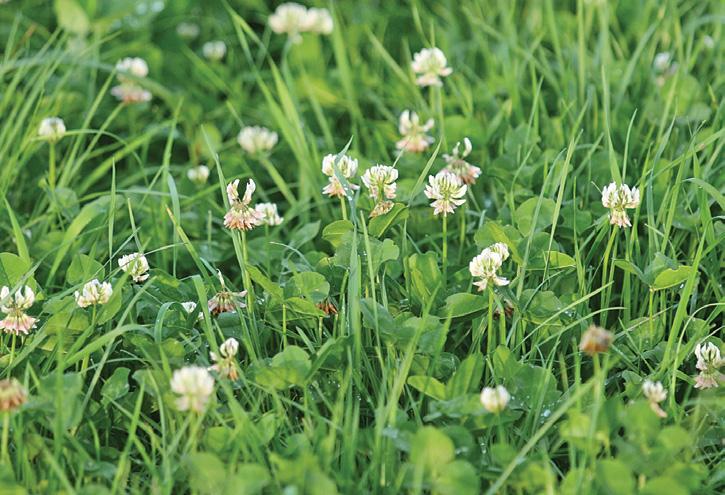

Alawn is rarely just grass. Over time, other plants creep in, some welcome, some not so much. In recent years, many gardeners have started rethinking what makes a healthy lawn. Instead of obsessing over a monoculture of turfgrass, some are embracing a more biodiverse, low-input groundcover that includes wildflowers, legumes and pollinator-friendly “weeds”.

Here’s a guide to some of the most common lawn dwellers, which you might want to encourage and which deserve the boot.

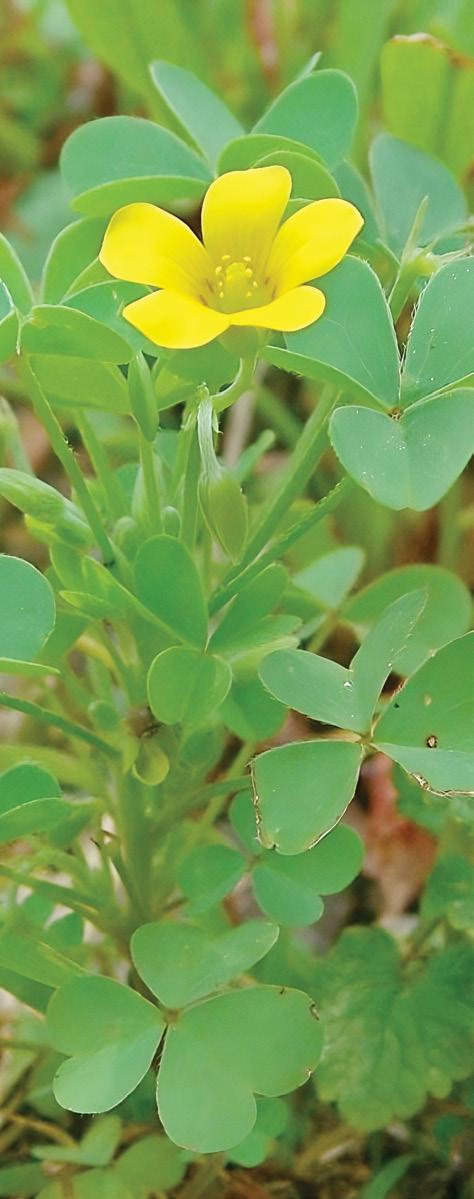

Plants to encourage

White clover (Trifolium repens). Once a standard in lawn seed mixes, white clover is making a comeback. This low-growing legume fixes nitrogen in the soil, helping feed nearby grass and reduce fertilizer needs. It tolerates foot traffic, stays green during drought, and feeds pollinators with its small white flowers.

Birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus). Another nitrogen-fixing legume, birdsfoot trefoil has bright yellow

flowers and deep roots that help with erosion control. While it can be aggressive in pastures, in lawns it tends to blend well with turfgrass and handles poor soils. It’s bee-friendly and thrives in dry, sandy areas where grass may struggle.

Yarrow ( Achillea millefolium). Common yarrow is a hardy, drought-tolerant native plant in much of Canada. It tolerates mowing, spreads by rhizomes, and adds texture with its feathery foliage and flat flower clusters. Some lawn enthusiasts use it in mixes for “stepable” turf alternatives.

Self-heal (Prunella vulgaris). Low and spreading with purple flowers, self-heal is native to many parts of Canada and provides nectar for bees and butterflies. It holds up well to mowing and adds seasonal interest to a mixed lawn.

Creeping thyme (Thymus serpyllum). This sun-loving herb forms a fragrant, dense mat with purple flowers in early summer. It’s excellent for hot, dry sites and tolerates

light foot traffic, making it a favourite in lawn alternatives.

Violets (Viola). Often appearing in shady lawns, violets provide early-season colour and are the larval host plant for several species of fritillary butterflies. While they spread readily, many gardeners are content to let them naturalize in low-traffic or semi-wild areas. (Some are native, others are not.)

Plants to tolerate

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). Love them or hate them, dandelions are here to stay. Their deep taproots help break up compacted soil, and their early blooms feed hungry bees. Mowing before they set seed will keep them in check.

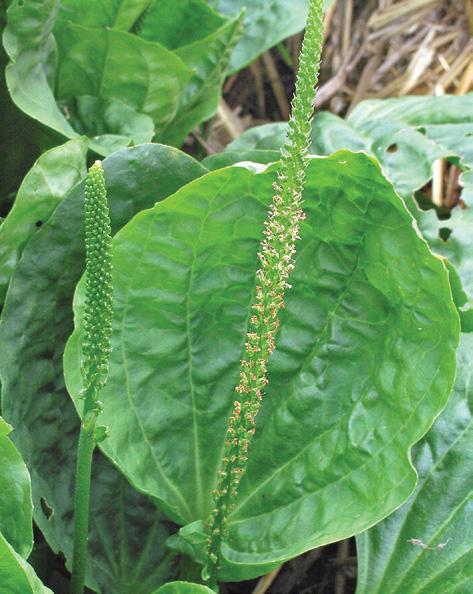

Plantain (Plantago major and P. lanceolata). These low rosettes thrive in compacted soil and may indicate poor drainage. They don’t spread aggressively and can be left alone unless you’re aiming for a pristine look.

Moss. Moss in the lawn isn’t a problem unless you’re trying to grow turfgrass in the same spot. It indicates shade, acidity, or poor drainage. If you can’t beat it, consider switching to a moss-friendly shade garden.

Plants to discourage Creeping bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides). Pretty but problematic, this plant spreads by deep roots and smothers neighbouring plants. Once established, it’s very hard to remove. Dig deeply or isolate infested areas. Ground ivy or creeping Charlie (Glechoma hedera-

cea). A fast spreader in shady areas, ground ivy forms thick mats that can crowd out grass. It resists mowing and pulling. If it becomes dominant, it’s often a sign your lawn needs more light, more air and better drainage.

Crabgrass (Digitaria). This warm-season annual weed germinates in bare patches and spreads quickly. It dies off with the first frost, leaving holes behind. Mow high, overseed regularly, and consider corn gluten meal in early spring as a pre-emergent control.

Quackgrass (Elymus repens). Quackgrass is a tough, aggressive perennial with deep, spreading rhizomes. It invades garden beds and lawn edges and is hard to

remove without digging or chemical control.

Rethinking lawn perfection

A perfect lawn isn’t necessarily a uniform carpet of Kentucky bluegrass. Many of the plants that “invade” lawns offer important ecosystem services, from feeding pollinators to improving soil health. Encouraging a mix of low-growing wildflowers and legumes can reduce your need for fertilizer, watering and herbicides. It also creates a more resilient, environmentally friendly green space.

Instead of asking “How do I get rid of this?” – try asking, “Is it hurting anything?” You might find that some of your weeds are just wildflowers in disguise. P

Story by Shauna Dobbie

Dandelions.

Here are some of the most common weed offenders, region by region.

Yes, many of them are edible; if you know which, go ahead and harvest them and have a feast.

Yes, many are listed in one area but quite common in one or more other areas. There is nowhere that is immune from Canada thistle (not Canadian, by the way) or dandelion. If you don’t see your favourite weed under your region, look for it in the other regions.

Three of them are natives. Normally we are disinclined to be uncharitable about our native plants, but these three can hurt you and are very prolific, so they are included.

British Columbia

Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) – Aggressive thicket-former in southern BC; hard to remove once established.

Buttercup (Ranunculus repens) – Creeping roots make it difficult in lawns and wet gardens.

Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) – Invasive shrub with yellow flowers; spreads in coastal areas.

Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) – Twining vine that strangles other plants.

Prairies

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) – Deep roots and wind-dispersed seeds; very difficult to control.

Scentless chamomile (Tripleurospermum inodorum) –Daisy lookalike that thrives in disturbed areas. Common tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) – Aromatic, button-flowered, invasive in pastures and roadsides. Leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula) – Toxic to livestock,

with milky sap and underground rhizomes.

Kochia (Bassia scoparia) – A tumbleweed that thrives in dry conditions and crowds out crops.

Wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis) – Fast-growing brassica weed; common in grain fields.

Russian thistle (Salsola tragus) – Spiny tumbleweed forming large, brittle skeletons.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) – Common everywhere but especially resilient in prairies.

Creeping bellflower (Campanula rapunculoides) –Invades gardens and lawns, hard to dig out.

Garlic mustard ( Alliaria petiolata) – Invasive in shady areas; displaces native plants.

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) – Native but aggressive in rich, moist soils.

Ontario and Quebec

Dog-strangling vine (Vincetoxicum rossicum) – Invasive twining plant in southern Ontario.

Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) – Extremely tough; spreads by rhizomes and root fragments.

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) – Woody invasive shrub with black berries and serrated leaves.

Ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea) – A creeping mint that smothers garden beds.

Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) –Dangerous phototoxic sap; can cause skin burns.

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) – Found in rural and semi-urban areas; three shiny leaflets.

Goutweed ( Aegopodium podagraria) – Aggressive ornamental escapee, hard to control.

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) – Invasive in wetlands and along ditches. Atlantic Provinces

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) – Especially invasive near water and roadsides.

Common ragweed ( Ambrosia artemisiifolia) – Allergy trigger; common in open fields and disturbed soil. Sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella) – Spreads by rhizomes;

common in acidic, sandy soils.

Hawkweed (Hieracium spp.) – Bright yellow flowers; invades lawns and roadsides. Northern Canada

White sweetclover (Melilotus albus) – Escaped forage crop now invading riverbanks.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) – One of the few widespread weeds even in the north. P

Story by Shauna Dobbie

In gardens across the country, some vegetables refuse to stay put. Whether by spreading underground, self-seeding freely, or simply outliving expectations, certain vegetables have a tendency to go wild when left to their own devices. Sometimes this is welcome; imagine a self-replenishing patch of greens! But in other cases, these exuberant edibles can verge on nuisance. Here’s a look at which vegetables are prone to naturalizing, reseeding, or even becoming weedy, and what that means for gardeners.

Perennials and biennials that come back stronger

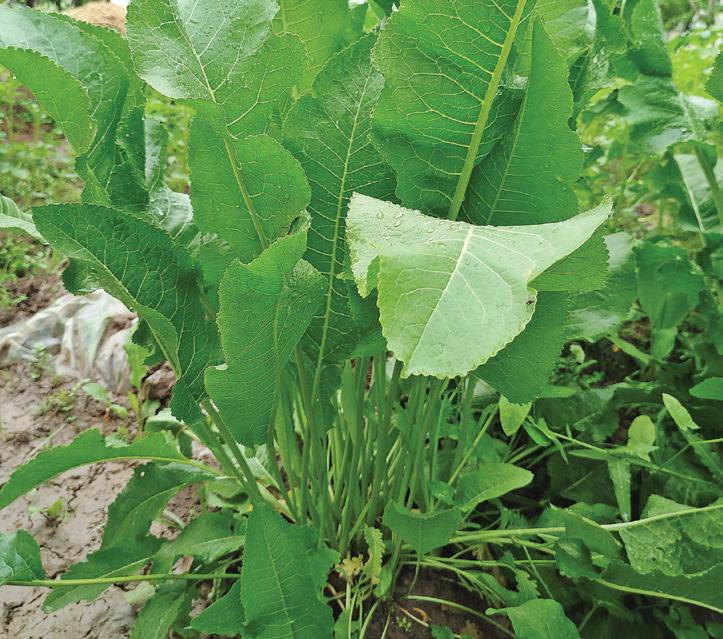

Horseradish ( Armoracia rusticana). Once planted, horseradish rarely leaves. Its thick roots are persistent and will regrow from even small fragments left in the

soil. It’s technically a perennial vegetable and doesn’t spread by seed, but its underground growth is vigorous. Gardeners often grow it in bottomless pots sunk into the ground to keep it contained.

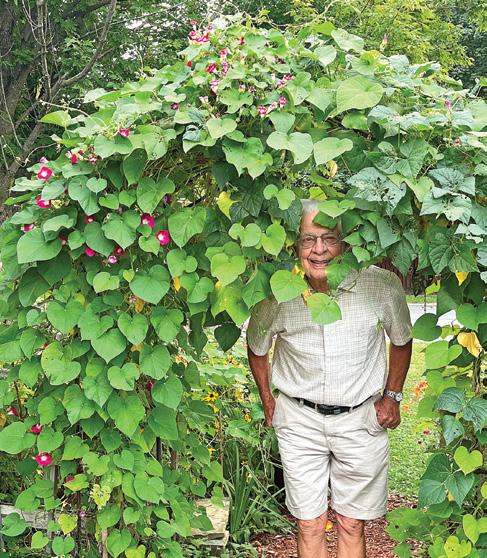

Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus). Also known as sunchoke, this sunflower relative produces edible tubers and can quickly form a thicket if not managed. Left unchecked, it spreads underground and re-emerges each spring, often in greater numbers. It’s beloved by pollinators but needs annual thinning.

Walking onion ( Allium × proliferum). These quirky onions earn their name from the way their top sets (bulbils) form at the ends of tall stalks, eventually flopping over and rooting wherever they land. Over time,

they’ll march across a garden bed unless corralled.

Asparagus ( Asparagus officinalis). The asparagus we see growing in ditches and field margins across the Prairies and parts of Ontario and Quebec are escapees from old homesteads and abandoned gardens. Asparagus is a perennial that can live for decades, and once established, it spreads modestly by seed. Birds are likely the main agents of that spread, eating the red berries from female plants and depositing the seeds elsewhere.

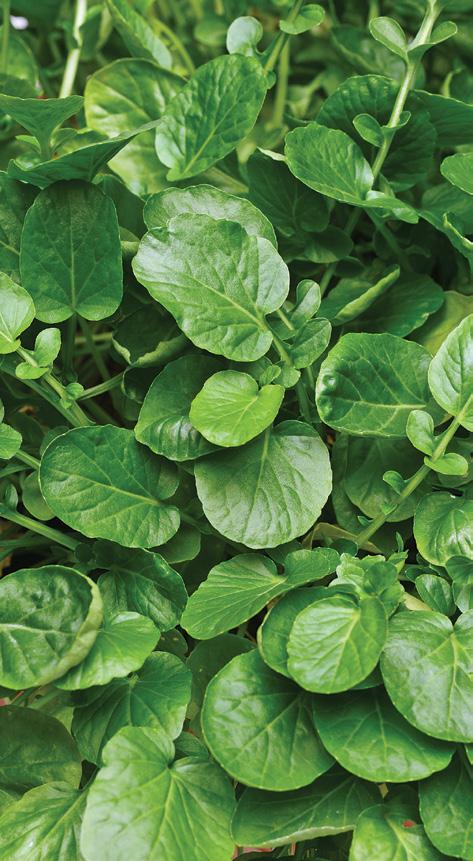

Arugula (Eruca vesicaria). This quick-growing green bolts easily in warm weather, sending up flowers and eventually scattering seeds. In no time, you

may find arugula growing in cracks in the sidewalk or popping up among other vegetables. It tends to revert to a spicier, more pungent form in later generations.

Dill ( Anethum graveolens). Loved for both its foliage and seeds, dill is a prolific self-seeder. Once established, it will happily reseed itself year after year. Though not invasive, it can be mildly annoying when it pops up in the middle of your lettuce patch.

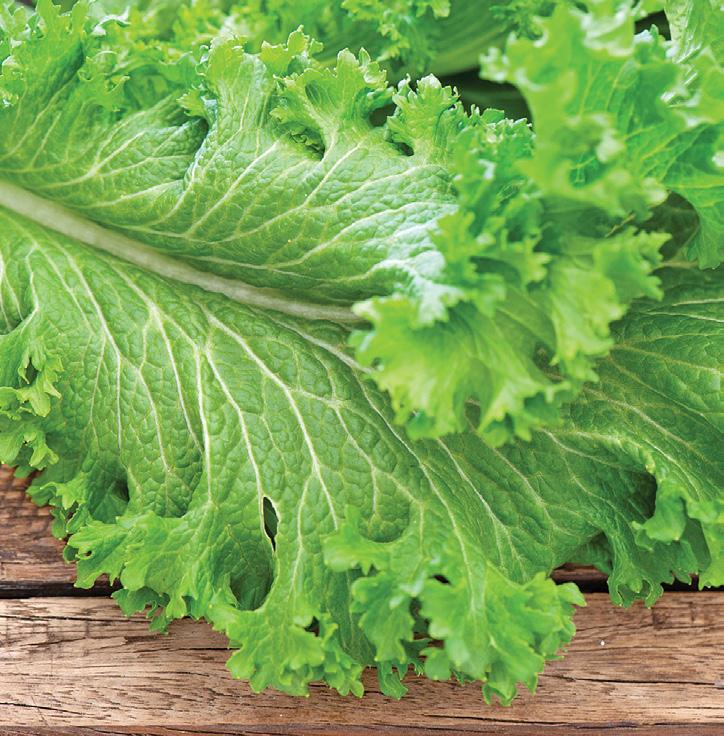

Mustard greens and other brassicas. Many brassicas are biennial, forming seed in their second year, but they can sometimes act like self-seeding annuals. Mustard greens, in particular, are enthusiastic re-seeders and may cross with each other to produce unpredictable offspring.

Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum). Surprisingly, tomatoes can naturalize in gardens, especially cherry or paste types with thick skins. Seeds from dropped fruit survive winter in mild regions or sheltered compost heaps, then germinate in spring. These volunteers are often hardier but less predictable. Escapees that turn weedy

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea). Some gardeners cultivate purslane for its nutritious, succulent leaves. Others spend all season pulling it out. Purslane is native in many regions, but cultivated varieties can go rogue and intermingle with weedy types.

BOB’S SUPERSTRONG GREENHOUSE POLY.

Amaranth ( Amaranthus). Whether you plant it for grain or greens, amaranth produces thousands of seeds and can escape cultivation. Some species are already common weeds in Canadian gardens. ‘Red Leaf’ and ‘Callaloo’ types often persist as volunteer seedlings in warm beds. Note that our native amaranth species are generally not those planted or used for food.

Garden cress (Lepidium sativum). This fast-growing green goes from seed to bolt in weeks. It self-seeds prolifically, and although it’s not persistent in colder zones, in milder climates it can become a recurrent feature. P

10 & 14 Mils. Pond liners. Resists hail, snows, winds, yellowing, cats, punctures. Long-lasting. Custom sizes. Free samples. Email: info@northerngreenhouse.com www.northerngreenhouse.com Ph: 204-327-5540 Fax: 204-327-5527

Box 1450 Altona, MB R0G 0B0

To place a classified ad in Canada’s Local Gardener, call 1-888-680-2008 or email info@localgardener.net for rates and information.

Join the conversation with Canada’s Local Gardener online! www.localgardener.net

Facebook: @CanadaLocalGardener

Instagram: @local_gardener

YouTube: @LocalGardenerLiving

Story by Shauna Dobbie

When spring rolls around and tiny green shoots begin to poke up from the soil, the excitement of new growth can quickly be tempered by a gardener’s dilemma: did I plant this or is it a weed?

It’s a common problem. Many weeds germinate earlier and grow faster than the plants we want in our gardens, and at the baby stage, they can look surprisingly similar. Being able to tell them apart is a skill that saves time, protects your plants, and helps you stay ahead of garden chaos.

Know your seed leaves

The first leaves to emerge from a seed are called cotyledons. These “seed leaves” look different from the plant’s later true leaves and are often smooth and rounded. Each plant species has distinctive cotyledons, though the differences are often very subtle. Once you learn to recognize the shape for what you’ve planted, you can start sorting what you want to grow from what you want to get rid of. See the chart for reference. Remember what was planted where

In the vegetable garden, you can often recognize sprouts in rows where you’ve planted seeds. Weed seeds don’t blow in as tidy rows. If you see a lone sprout outside the planting zone, it’s probably a weedling. There are times you may wonder what is growing early on, though.

In the flower garden, you’re often dealing with perennials coming back from last year, self-seeded annuals, and newly planted ornamentals all in the same bed. Unlike vegetable rows, there’s usually no neat layout to guide you. The key is observation and memory. Did you plant that spot with larkspur last year? Did you scatter poppy seed or leave that area for rudbeckia?

Using garden markers or snapping a photo when planting helps you compare later. Even knowing roughly which colour or height goes where can narrow it down. And if you are a very diligent gardener, a drawing of what is where will help a lot.

Many weeds will take advantage of bare spots, but a plant growing precisely where something came up last year – or where you tucked in seeds last fall – is more likely to be welcome.

If you’re not sure, gently tease the plant out of the soil. Seedlings typically have a fine, fibrous root system, especially if they’re annuals. Weedlings often have a strong taproot or thick spreading roots even at a young age, since they’re adapted to compete in tough conditions.

Use a photo guide or make your own

If you are really keen, you can plant a few extra seeds in a labelled tray or pot and photograph them as they emerge. That way, you have a reference for what your seedlings should look like. You can also find excellent

online guides with images of common weeds at the cotyledon and first-true-leaf stages. When in doubt, wait a few days

It’s often better to let a mystery plant grow a little until it produces its first true leaves. These are the second pair of leaves that appear and often look much more like the mature plant. If it turns out to be a weed, you can always remove it before it flowers or seeds. Patience and observation are your best tools. With a bit of practice, you’ll soon be able to tell your kale from your crabgrass and your cosmos from your chickweed before it’s too late. P

Plant Often confused with How to tell them apart

Tomato Black nightshade

Carrot Grass seedlings

Beet Lamb’s quarters

Radish Mustard or shepherd’s purse

Lettuce Chickweed

Peas Vetch

Beans Velvetleaf

Zinnia Pigweed or lamb’s quarters

Marigold Ragweed

Cosmos Dill or fennel

Sunflower Burdock

Petunia Chickweed

Nasturtium Wild violet or mallow

Morning glory Bindweed

Impatiens

Spurge or purslane

Bee balm Stinging nettle

Daylilies

Creeping bellflower

Violets Garlic mustard

Tomatoes have oval cotyledons and fuzzy stems; nightshade is shinier.

Carrot cotyledons are very narrow; true leaves are fern-like.

Beets are often red-stemmed; lamb’s quarters have powdery leaf backs.

Radish has thick, heart-shaped cotyledons and fast top growth.

Chickweed is sprawling and mat-forming; lettuce grows upright.

Peas are thick and fleshy; vetch is viney and has tendrils early.

Beans have thick, rounded cotyledons; velvetleaf has more heart-shaped ones.

Zinnia cotyledons are smooth and oval; amaranth leaves are rougher.