95

THE MAGAZINE FROM PALAIS DES THÉS

Clément Régis CSR Manager

95

THE MAGAZINE FROM PALAIS DES THÉS

Clément Régis CSR Manager

Help to share tea with as many people as possible: this is what drives us every day here at Palais des Thés. Our business philosophy is a catalyst for fulfilment and fosters a collective spirit, and it is something we share with our long-standing partners, suppliers and the supported employment organizations (known as “ESATs” in France) with whom we work. For over thirty years now, we have established partnerships with fifteen French ESATs, which are designed to enable people with disabilities to work in a protected environment.

The company primarily assigns ESATs with the task of packaging our teas and herbal teas, such as filling our fresh-seal refill pouches and metal tins, applying labels and assembling our Advent calendars and certain gift sets. In 2024, sixty-eight thousand Advent calendars were assembled by disabled workers, some of whom were invited to come and present their work instore for the day, and share their experiences directly with customers during the holiday season. It was the opportunity to enjoy an exchange over a cup of tea and for the company to highlight the quality and success of our collaboration with the ESATs and the beneficial social impact this production model can have.

As a socially responsible and civic-minded company, we are naturally committed to integrate and empower disabled people in the workplace. Not only is supported employment a source of pride as well as strength for our company, but it also brings important social and professional value too. Further proof that tea brings us together!

Cold infusions reveal and highlight different notes, making for an alternative way to rediscover and explore your favorite teas.

By Elena Di Benedetto, Marie Laperrière and Kenza Benkhatar

CONTRIBUTORS

Lola Sitruk

Lola obtained her Master Tea Sommelier diploma in 2024 and loves discovering the same tea using different brewing methods to compare the impact on flavor.

Laetitia Portois

By Lola Sitruk

Laetitia Portois

Laetitia has a penchant for Japanese green teas. She enjoys storytelling and every day turns part of her job into a passion.

Elena Di Benedetto

Elena obtained her Master Tea Sommelier diploma in 2024 and is an expert in Taiwanese oolong teas. She considers every cup to be a source of discovery, whisking her away to faraway lands.

Every year, Palais des Thés founder François-Xavier Delmas invites the most recent Master Tea Sommelier* graduates on a trip to a tea-producing country. At the end of March, Lola, Kenza, Marie, Lucie, Simon and I all headed off to the “land of thunder.” It is one thing to have read about the adventures of Robert Fortune, the tea spy who made India the British Empire’s new tea-production powerhouse in the nineteenth century, and it is quite another to actually set foot on these dizzyingly steep tea gardens for the very first time!

By Elena Di Benedetto, Marie Laperrière and Kenza Benkhatar

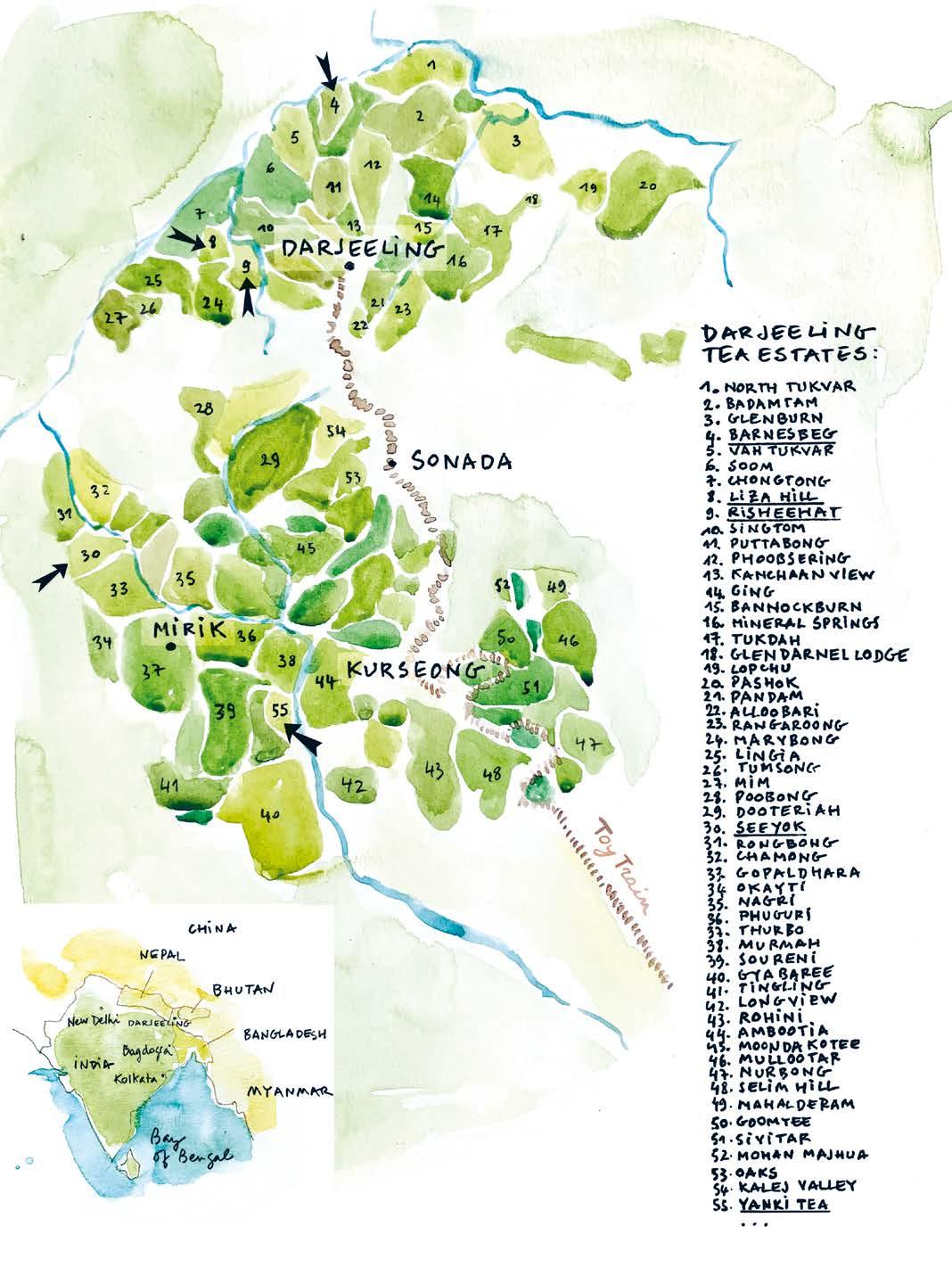

Darjeeling is François-Xavier Delmas’ favorite tea-growing region. Now in his sixties, he tells us he has given up counting the number of times he has visited these lands. Taking his role as guide very seriously, at the airport he explains the basic travel etiquette, from the subtilities of gestures and body language to local customs. We have barely landed in New Delhi before we jet off for Bagdogra, in northeast India and just south of Darjeeling. From the airport, there are tea plants everywhere, stretching as far as the eye can see. Their leaves will be used to make tea for tea bags, made using the CTC method (for “crush, tear, curl”).

Much more than just our drivers, Pema and Muhammad will be our travel buddies for the journey. They are full of tips for places to visit and willingly share anecdotes during the many long hours spent together, to the sound of the local radio in the background (mantras in the morning, international pop music in the afternoon). We follow the same route as the Toy Train, which links New Jalpaiguri, near Siliguri, to Darjeeling. This heritage steam train skims the mountainsides and pierces the clouds over a distance of exactly 88.48 kilometers. At every turn, we are clinging to our seats wondering only one thing: “Will it – or won’t it – pass?”

In Darjeeling, there is a vast difference in climate from one tea garden to another, despite only being a few kilometers apart. It is a unique feature of the region!

*A Master Tea Sommelier is a Palais des Thés employee who has passed a demanding internal exam that recognizes a high level of expertise in tea knowledge.

Our first port of call before arriving at a bustling Darjeeling at nightfall is for our first taste of momos – small steamed Tibetan dumplings – served with a local tea and slightly minty, sugar-coated fennel seeds. They are perfect for cleansing the palate – especially for ones like ours so unaccustomed to spicy foods. At over two thousand meters above sea level, Darjeeling is a city suspended at dizzying heights, lined with multi-colored houses which cling to the hillside. Up here, the climate is cooler than on the plains, which made it a popular vacation spot for the English in the nineteenth century, and today for local and international tourists in search of fresh air. From the main square, it is impossible to resist the breathtaking sight of the Himalayan range and Mount Kanchenjunga, the third-highest mountain in the world (8,586 meters), when the mist clears to reveal all its glory. Darjeeling will be our base for three days. We will have time to taste its culinary treasures filled with Tibetan, Nepalese and Chinese influences, and discover the rows of tiny shops and street vendors among the hubbub that we are gradually getting used to.

The following morning, we leave Darjeeling behind and take the hour-long journey to visit Risheehat and Liza Hill’s tea gardens. We soon realize that it is pointless to count the distance of each trip in kilometers, given the rocky and unpredictable state of the roads. These two estates, now joined together, are very steep, as is often the case in this mountainous region, which makes manual harvesting methods a must for this rather acrobatic exercise. The manager, Rajiv Kumar, welcomes us onto the estate which still bears witness to its colonial legacy. When India gained independence in 1947, three quarters of the tea estates belonging to British companies were nationalized. As such, tea farmers, like those here, rent the land from the state and often belong to major business groups that own several tea estates. Inside the spacious factory, we spot tea machinery made in England, still in perfect condition. As we arrive late morning, leaves harvested the day before have already been withered, rolled and dried overnight. The next step is for the leaves to be sorted by hand. Due to cold weather and lack of rain, this first flush harvest is currently poor. In the eighty-seven tea gardens clinging to the mountains, one of the challenges is to produce teas – of varying quality – while adapting to an unpredictable climate. The tea maker answers our countless questions and explains to us the differences in processing a first, second and third flush tea* and the importance of the withering stage. This stage makes the leaves more pliable, so they can be rolled without breaking. Experience alone is required to master the temperature and humidity in the room, as well as deciding when to stop the process at the point when the leaves have lost up to 50 percent of their moisture and begin the enzymatic transformation process necessary for oxidation. All the theory learned for the Master Tea Sommelier exam is finally being witnessed in real life! As in each of the first three factories we visit, we finish with a tea tasting session, in a dedicated room with a special tea tasting set (consisting of a tea infuser mug with a serrated edge and a lid). We will be tasting six incredibly fresh first flush teas from different tea varieties and different plots, all harvested two days before we arrived. Day after day, we are touched by the warm welcome we receive from the farmers who invite us in to their bungalows as distinguished guests and treat us to fried puffed bread rolls, a range of vegetarian curries, daals, jalebis (orange-colored fried pastries soaked in a fragrant syrup), lassis and much more.

Darjeeling must contend with a mountainous terrain and an unpredictable climate

If there is one shared intention across the three tea gardens visited – Risheehat, Barnesbeg and Seeyok – it has to be this: first flush teas should be light and bright. Although classed as black teas, the “light” teas we taste have a very clear tea liquor with vegetal notes due to the leaves not undergoing oxidation. These teas are primarily for export, as the domestic market has a preference for richer, fuller-bodied teas harvested in summer and fall. For example, we appreciate the zesty notes of the AV2 cultivar (tea plant variety), however these are rarely the tea makers’ favorites.

*In India, harvests are commonly referred to as flushes, a word that is remnant of its colonial past. First flush, second flush and third flush refer to the spring, summer and autumn harvests, respectively.

With the earliest harvest of the year, each year Darjeeling teas kick off the new tea season, with the long-awaited first flush Darjeeling.

The following day in Barnesberg, we are struck by how clean and spotless this tea estate is, which offers its workers additional facilities and services, like day nurseries and access to healthcare. “Quality breeds cleanliness,” reads a sign in the factory.

For this new day, we head off to meet Nikita, the Karuna-Shechen local representative, in a village near to Dooteriah, an old tea estate that is now closed. Over the past several years, Palais des Thés has been working in close collaboration with this NGO to provide financial support to projects in tea-growing regions. The villagers we meet have, for the most part, lost their jobs following the closure of the tea estates. Nevertheless, several locals continue to harvest and produce small quantities of tea at home, which they sell at markets or keep for their own consumption. Training courses in market gardening, horticulture and beekeeping enable them to support themselves in other ways and regenerate resources. In the spirit of KarunaShechen, the programs supervised on the ground by local leaders impact people directly, like the distribution of seeds and netting to protect crops, or providing training in good agricultural practices. We take part in the village council meeting, attended by around thirty others, and discuss possible solutions in relation to the current economic and cultural climate. While chatting to the young people, we understand why some of them wish to leave the mountains for the city on the plains down below, while others express their desire to develop sustainable projects locally.

In the afternoon, we follow the Nepalese border to reach Seeyok. The Seeyok estate is a lesson in agroforestry and applied biodiversity! Deer, birds, streams – there is so much to marvel at as we stroll through the estate. “We sometimes come across bears and leopards!” exclaims JP Gurung, the plantation consultant – both a great tea expert and a wise man – who leads

The teas tasted on site and pre-selected by François-Xavier Delmas will be tasted again back in France. The breathtaking setting, the emotional bonds and even the way in which the tea is prepared (here, with a higher water temperature and quantity of leaves than we would recommend) can all distort our judgment.

The first tea garden on our tour, Risheehat offers breathtaking views.

the tour. The teas produced here are of consistent quality. Despite the dangers of returning home late at night on this rugged terrain, we cannot decline the invitation to share a delicious buffet followed by an evening around the fire, singing a mix of Nepalese chants and French and international classics. The small town of Mirik will be our base for the night.

We arrive at Yanki Tea estate to discover a whole different manufacturing model. This estate may be the minority, but it is encouraging for the future of Darjeeling. First and foremost, Yanki Tea is a Nepalese family. Operating as a co-operative, Alan and his mother, a strong-minded woman who ran a business as a tea reseller before switching to making teas, purchase tea leaves from smallholders at a fair price. The tea garden is an example of the small proportion of estates (25 percent) which are not nationalized. The machinery – some of which are second-hand – are smaller. Teas are processed using a less conventional production method. Eusha, Alan’s wife, a tea maker at La Mandala, is certainly no stranger to this sidestep. Among the interesting teas tasted under the pergola built by the father, we enjoyed the creativity displayed in a hand-rolled tea (which results in a different level of oxidation than a “classic” black tea), a roasted tea and even some surprising blends. It is possible that you might just find in store small quantities of one of these teas that we enjoyed so much and are eager to share with you. It is only by going directly to the source, to meet the producers, that we can fully understand the tea makers’ intentions and measure their expertise for making the finest quality teas. Back in head office or in store, we each relive the warm and enlightening moments we experienced in Darjeeling by sharing them with other tea lovers – be they colleagues or customers in store –over a cup of light and bright, first flush Grand Cru tea! •

Matcha is made from Japanese green tea leaves ground into a fine powder. It is the central element for the traditional Cha No Yu tea ceremony. After years under the radar, its popularity boomed worldwide at the beginning of the aughts. From ancient tradition to modern superfood, how and why is this green tea taking over the foodosphere?

By Laetitia Portois

The story behind matcha does not begin in Japan, but in China, during the Song dynasty (960-1279). At the time, tea leaves used to be ground into a powder and mixed with hot water. It was in this form that the Japanese Buddhist monk Eisai brought tea over from China to the Land of the Rising Sun, at the end of the twelfth century. This drink has a high theine content as the whole tea leaf is consumed. It soon became popular in monasteries throughout the thirteenth century, because the monks found it helped improve their focus during long meditation sessions. In the sixteenth century, the Zen Buddhist Sen No Rikyu ritualized the relationship between tea and Buddhism and elevated the traditional Cha No Yu (literally “hot water for tea”) tea ceremony to its most accomplished form. This ritual is held in a purpose built tea room with understated decor, where, after several purification rituals, the tea master prepares the matcha – always of the highest quality. A thick matcha (koicha) is first served, followed by a lighter blend (usucha). Preparing the latter requires specific gestures: the tea master adds three scoops of matcha to a bowl, followed by a ladleful of hot water before whipping together with a bamboo whisk. The guest of honor receives the bowl, takes a sip and compliments the host on the tea. Synonymous with tradition, matcha has since undergone various transformations that have changed the way it is used. The preparation method used by monks inspired the samurai, for the philosophy behind it is similar to that of martial arts (the gestures must be precise, you savor the moment before going into action). It was drank before going into battle, to help them stay focused and alert. Noble warriors also helped spread its popularity within the Imperial court. As its use spread, so too did its use as an ingredient in the cakes served during the tea ceremony, often paired

with red bean paste. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Japanese government brought it back into the spotlight and wanted to make the Cha No Yu an elite artistic discipline. Matcha is a way for the archipelago to assert its cultural identity in the face of growing western influences. Despite opposition from tea masters, the ceremony is taught to young girls from good families and practiced by geishas as an art in its own right. This tea powder thus loses its martial aspect and is elevated to the status of an art form, inscribed in Japanese culture. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, thanks to globalization and Japan opening up more to the outside world, the country became a very popular travel destination, particularly for its culture and gastronomy.

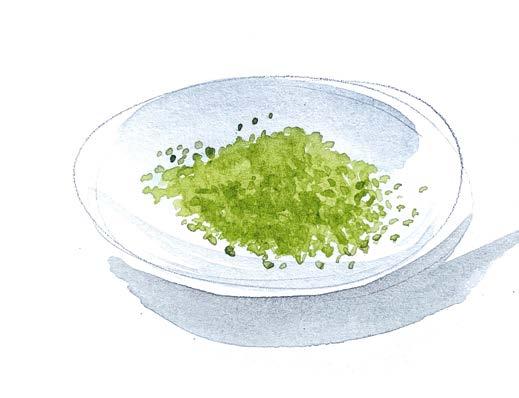

In Japan, a difference is made between shade-grown teas and teas grown in the light. Matcha is a shaded tea, made using leaves from tea plants that have been partially and deliberately deprived of light for several weeks. This causes the plant to draw nutrients from its roots, altering the leaf’s aromatic compounds: the level of sugars, amino acids and theine increase, giving the tea its strong umami flavor.1 The leaves are then machine-harvested several times a year. Machinery is then used to remove the veins and stems, leaving only the leaves (tencha). The leaves are steamed, then, once dry, ground between millstones. The duration of the grinding process determines how fine the resulting powder will be, which should have a beautiful, bright jade-green color. Another factor that influences the color is the harvest period: for example, leaves picked in spring are greener than those picked in summer, therefore the resulting matcha will be more vibrant green. The tea powder is then packaged in airtight metal tins, preventing exposure to light, odors and moisture to preserve its quality.

From being grown in the shade to steaming the leaves, then grinding them whole between millstones to create a fine powder, all these steps are characteristic of matcha. In more ways than one, this tea remains a specialty of Japan, the world’s leading producer and exporter. Beyond the tea ceremony, it is highly valued for its culinary uses, its exceptional aroma and taste, its characteristic green color and its health benefits.

Over the past few years, matcha is everywhere and its consumption is skyrocketing. This trend began in 2018, hitting its peak in 2023-2024. According to the British magazine The Economist, global daily sales of matcha increased fivefold between the summer of 2023 and the summer of 2024. For The Business Research Company, an Indian market research company, the market is currently worth an estimated $4 billion (the tea market was estimated at $52 billion in 2023) and this trend is exponential, with an estimated annual growth rate of 8 percent by 2030 (or more than €7 billion within five years).

This green tea powder has mainly become popular in the west on dessert menus in restaurants, tea rooms and cake shops, and as a takeaway latte. Its vibrant color makes it highly photogenic: a sought-after aesthetic in the culinary world that has helped it make a name for itself.

1 Umami, commonly translated as “savory,” is one of the five basic tastes, along with sweet, sour, salty and bitter.

Between the summer of 2023 and 2024, daily sales of matcha increased fivefold.

Source: The Economist

These days, matcha is seen as a drink enjoyed as part of a healthy lifestyle. It can be enjoyed any time of day as a latte, from breakfast to late afternoon. Thanks to its energizing properties and abundance of antioxidants, it is gaining popularity among younger people who are looking for the latest trend in coffee alternatives. Its high theine content provides a steady, slow release of energy, without the jitters or crash. Its high levels of L-theanine, an amino acid that steadily releases theine in the body, has a calming effect. Meanwhile, its green color evokes nature and freshness. Made using a special whisk, its preparation method is rather unique. These selling points appeal to younger generations who have made this green tea powder the symbol of a healthy lifestyle. It aligns with a quest for wellness fueled by routines popularized by a digital community and the “clean girl” aesthetic, a lifestyle concept born in the US. These women’s infatuation with matcha (always served as a latte, made with plant-based milk) has caused this trend to emerge – and then explode. Some content creators have even launched their own matcha brands with dazzling success.

Overnight success is a double-edged sword. The rapid rise of the hugely popular global matcha craze is putting producers under considerable pressure and straining the entire tea supply chain in Japan. According to data from the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), the archipelago produced 4,176 tons of matcha in 2023, three times more than in 2010 (1,471 tons). So why not produce more? There is the issue of farmland scarcity and the need to reconsider the type of tea plant used. Indeed, cultivars such as saemidori and gokou are ideal for making matcha, as the leaves have a more pronounced umami flavor than yabukita, the most common cultivar in Japan. Furthermore, the leaves are only harvested several times a year, unlike some producing regions that harvest continuously from spring to late autumn. This limits the amount available. Farmers are putting in overtime to meet demand. Added to this is the decline in the number of tea producers, which fell from 53,000 in 2000 to 12,353 in 2020 (according to the MAFF).

In 2024, Japan experienced an unprecedented matcha shortage. For certain brands, such as Ippodo, the majority of their stocks sold out in record time, prompting them to increase their prices and limit purchases to one item per customer. At Palais des Thés, we also encountered some supply chain issues, which we managed to overcome thanks to the relationships of trust built up over the past fifteen years with our partners and producers. With the trend showing no sign of slowing down, other countries, such as China, are now beginning to produce matcha. Here, teas are produced industrially, without following the process established by Japanese producers. They are certainly much cheaper, but the quality is significantly lower. Since there are no labelling controls, anything can be labeled “matcha,” despite it being the case.

Matcha’s global reach extends far beyond the realm of gastronomy. Matcha is now inspiring the perfume world and has even become a color shade trend dominating design and fashion. Just how far will this craze go? •

These days, matcha is enjoyed in a multitude of ways as a drink and in food. With its vegetal notes and pronounced umami flavor, matcha is appreciated for its culinary versatility, its gorgeous green color and its unique aromatic profile. If you want to learn how to recognize a good quality matcha and how to prepare it as a latte or in the traditional way, you need to follow a few easy steps.

The way in which a matcha tea has been produced will determine its flavor profile. The following points are an indicator of quality.

Its origin: Japanese matcha is best.

Harvest and production methods: green tea leaves harvested from shadegrown plants, ground using a millstone.

Characteristics: a very fine powder with a vibrant emerald-green color. And of course, as for any tea, the quality depends on the natural environment in which it is produced and the production techniques applied.

Organic matcha: this guarantees that no chemical fertilizers were used in its production, an essential factor as organic fraud is rife. At Palais des Thés, some of our matcha teas are organic and some are at a minimum SafeTeacertified (see Bruits de Palais no 93, p.36-37). Every tea is independently tested to ensure they meet strict EU regulations concerning pesticide residue standards.

To make a classic matcha the traditional way, special teaware is required: a bowl (chawan), a bamboo whisk (chasen) and its stand, which helps it keep its shape, plus a matcha scoop.

Sieve two scoops (or one level teaspoon) of matcha into a bowl. Add 50 ml of hot water (70°C) to the powder. Hold the bowl firmly with one hand and use the other to vigorously whisk the tea in a “W” shape, until a fine frothy foam is created.

Matcha has a really interesting umami flavor, which brings out and balances the sweetness, saltiness, bitterness and sourness of a dish.

For savory dishes, matcha’s herbaceous notes of sorrel, watercress and spinach add depth to seafood recipes. It can be mixed with salt or added to a sauce to accompany fish, or can even be used to enhance mayonnaise.

A coffee shop bestseller, the matcha latte is really easy to make at home.

Add a teaspoon or three scoops of matcha into a bowl or mug. Add 50 ml of hot water (70°C) then whisk with an electric milk frother or a bamboo whisk.

In a separate container, froth warm milk with the electric frother, then pour over the matcha mixture.

Top the foam with a dusting of matcha powder and enjoy!

Matcha has a lingering aftertaste, so can be used to accentuate the vegetal notes of a vegetable soup.

For cakes and pastries, it can be added to creams, cookie doughs, pancakes and waffles. It pairs just as well with chocolate as it does summer berries. The possibilities are endless with matcha. So let your imagination run wild!

From the tea bush to the teapot, the soil plays a background role. Essential for the tea plant to thrive, its influence shines through when preparing, serving and sharing a cup of tea. Let’s take a look at the unbreakable bonds between tea and the soil.

By Elena Di Benedetto

Soil, terroir, clay… From ground to cup, tea is a virtuous circle: if the Camellia sinensis takes root in fertile land, the tea it produces then reveals its character in earthenware objects that are sometimes thousands of years old. From India to Japan and China, the earth is inextricably bound to the way of tea.

The tea comes from an evergreen shrub, the camellia. While some varieties are ornamental and grown for their flowers, the Camellia sinensis is prized for its deep green leaves with an eye-like shape. Once processed, they make all the different tea colors.

Soil: “Substance to support the growth of plants and crops.”

The Camellia sinensis requires specific conditions to flourish and grow: sunshine, humidity, temperature, elevation and… soil quality. It is certainly pretty impressive that tea can grow in such varied latitudes, from flatland to steep mountains, in soil composed of various rocks such as gneiss or granite, but certain geological characteristics are particularly beneficial for a healthy tea plant.

Young, volcanic soil is best for the tea plant. The soil must be acidic, not chalky nor neutral, so that the plant can absorb all the nutrients it needs; its ideal pH is between 4.4 and 5.5. The soil must also be loose, welldrained, rich in organic matter and have good depth, so that the roots can burrow up to six meters deep. In addition, the soil must be able to retain moisture during periods of drought, but also allow good drainage during heavy rains, as waterlogged soils can damage the roots. Soil rich in nutrients (potassium, magnesium, trace elements) will ensure plants flourish. No fertile land, no healthy tea plant, and thus no tea. Hence why sustainable – and ideally organic – agricultural practices are important, as they respect both the soil and the environment. All life begins in the soil, which is forever transforming to offer the best conditions for our favorite drink.

In India, chai is often served in small, disposable clay cups that are thrown on the ground and crushed into the soil.

Terra cotta:

“Natural material made up of different clays; this material results from the potter working its natural form, clay.”

The first traces of terracotta (tao in Chinese) can be found as early as 20,000 BC in China. While animal skins could also be used to make waterskins and other airtight pouches, nothing could rival clay’s robustness. Clay was first molded and dried, then fired once at a low temperature (600°C-800°C). In the fourth millennium BC, and then from Antiquity onwards, the firing temperature increased to obtain more solid and less porous objects. Now watertight, these ceramics became crucial for transporting liquids. However, there was one notable drawback: they crack and warp.

More than three thousand years ago, stoneware (ci in Chinese), a more durable and completely waterproof ceramic, began to emerge. Twicefired and made from silica-rich clay, this type of pottery is glazed, preventing water absorption. What a game-changing innovation!

Trees planted among the tea plants provide shade and help the soil retain moisture.

Finally, porcelain (also called ci in Chinese) was created around the seventh century, again in China. At the time, it was even referred to as “white gold”: the porcelain recipe was a closely-guarded state secret, so much so that anyone who tried to reveal it was threatened with the death penalty. While the first example was believed to have been made during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), it was during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that this practice developed. Its immaculate whiteness and glossy glaze are due to the presence of kaolin, a new material that transcended the possibilities of ceramics. Delicacy and translucency were now synonymous with the artisanal craft of porcelain making.

With all these possibilities, artisan potters could have simply focused on a single type of ceramics. However, despite being considered as imperfect, porous terracotta continued to gain ground in the tea world. The various ways in which this material is used enables us to understand its influence in tea tasting.

Traveling through different tea-growing regions, it is striking to see how each region, each tradition adjusted these practices according to the raw materials available nearby. And every time, clay features prominently.

Yixing clay teapots, China: Made from clay produced locally in the Jiangsu province and which contains iron, mica and silica, these teapots are prized for their porosity and their ability to absorb the tea’s flavors. Used in a Gong Fu Cha tea ceremony, these small teapots are said to have a “memory” as they season with use. A deposit of tannins and aromatic compounds build up over time on the interior, meaning that every time tea leaves are brewed, there is an osmosis between the tea and its container.

Tokoname kyusu stoneware teapots, Japan: On the island of Honshu in Japan, Tokoname clay is renowned for being rich in iron and especially silica. Teapots made with this material are perfect for preparing Japanese green tea. In fact, apart from being a great diffuser of heat, the iron works with tea catechins to help reduce astringency. As such, this delicate objects works in symbiosis with the tea to enhance its flavor. These hand-crafted

Often used to elevate the finest teaware, the designation “Yixing” is commonly confused with zisha clay (“purple clay”), which seems to be the type of clay most commonly used to craft these exceptional objects, although other clays ( zhuni and duanni) exist in the region.

Japanese tea cups are often finely hand-crafted and meticulously detailed.

A smaller teacup captures the tea’s aromas better and will be enjoyed more quickly.

Silica is a natural compound composed mainly of silicon dioxide. It is found abundantly in nature in various forms, such as sand and quartz. It is responsible for rendering a material porous and waterproof. The higher the silica content, the less grainy the clay will be when fired.

teapots often have a side handle and are an essential part of the Senchado tea ceremony in Japan.

Terracotta chai teacups, India: While in the western world, terracotta is often synonymous with long-lasting objects, in India, it is often considered disposable. Chaiwallahs, or street vendors selling the milky spiced tea, sell the warm drink in thin, little terracotta cups that are smashed on the ground once finished. This ritual is observed to preserve purity between castes: as each cup is single use, it is certain that no person from a lower caste will have used it before.

But the connections between the earth and tea does not stop there. Some teas continue their journey in traditional earthenware vats to obtain a characteristic patina. From Korean onggi or Georgian kvevri, the earth then enters into synergy with the tea. Black and fermented teas are finished off in these vats, the material leaving its mark on the tea. Finally, there are countless “tea pets” made of porous clay. Widely used during the Gong Fu Cha ceremony, these small sculpted animal figurines are doused with leftover tea or discarded “wash” water, as if to feed the pet. With each shower, the clay changes color and the tea imparts its history, as a reminder of all the cups you have enjoyed.•

Join me on a journey to southwest China, to the mountainous Yunnan province. Nicknamed “the South of the Clouds,” the region offers up magnificent landscapes mixing mountains, rice paddies, rivers and tropical forests. Let’s taste together a rather complex and remarkable tea: the Golden Yunnan Buds.

By Lola Sitruk

Lola Sitruk is a data analyst who obtained her Master Tea Sommelier diploma in 2024. An avid tea lover, her ever-growing curiosity for teas continues to shine at Palais des Thés. She loves discovering the same tea using different brewing methods to compare the impact on flavor.

Considered the birthplace of tea , the Yunnan province is one of China’s most iconic tea-producing regions. The region is mainly renowned for its pu erh tea, a fermented tea made from long tea leaves harvested from tea bushes growing in the Yunnan province, which are then dried in the sun before undergoing fermentation. This undulating landscape is covered in forests filled with wild tea plants. To the south lies the mountainous Jing Mai region, where the oldest tea plants in China are found. Among them is the Camellia sinensis considered to be the oldest in the world. Steeped in history, the Yunnan province is the starting point for the earliest teahorse roads, ancient trading routes linking China to Tibet, India and Southeast Asia. Tea was traded for horses, a commerce that marked the beginning of the spread of tea while also contributing significantly to its growth throughout Asia.

The tea that we are going to taste is a Dian Hong Cha. The name indicates that this black tea is produced in the Yunnan province. “Dian” is in fact a reference

to a kingdom that existed between the fourth and second centuries BC, corresponding to the present-day Yunnan. Dian Hong Cha literally means “Dian red tea” (“Hong ” means “red” in Chinese).

This Grand Cru is a feast for the eyes, before you even taste it. It is composed almost exclusively of long, fuzzy buds [1] which, during oxidization, take on a beautiful tawny color. This first flush tea is hand-processed.

It is a delicate and skilled process which never ceases to amaze me. The dried leaves give off a powerful flavor, a mix of earthy, leather, animal aromas with yellow fruits.

I like to make this tea using the traditional Gong Fu Cha method, but in a tiny Yixing clay teapot, and enjoy watching the leaves swirl about and unfurl as they infuse [2]. This method consists of infusing the leaves multiple times in short succession (30-40 seconds), using a high ratio of leaves to water. I like this preparation technique because each serving offers something new. The leaves reveal their story and their secrets with each infusion. Before tasting it, I quickly “wash” the leaves for a few seconds for the first infusion, discarding the water without drinking it. I take the time to admire and smell the wet leaves. The buds have opened and softened, their golden hue takes on a beautiful coppery color.

The amber liquor is strong and bright [3], an indicator of the emotions it will arouse. This tea has a dominant mouthfeel, yet offers a deliciously sweet sensation. It has a round texture and a sharp astringency. The sweetness comes through with aromas of honey and jammy fruits, like apricot. I usually enjoy this tea in the morning, to savor its full aromatic richness. The first infusion will be sweet and honeyed, with the animal and coppery notes revealing themselves over successive infusions.

The Golden Yunnan Buds pairs beautifully with a fillet of duck breast. When grilled, the meat’s smoky, woody notes blend perfectly with the tea’s coppery,

animal flavor. For a sweet treat, this Grand Cru’s honeyed aspect perfectly balances out a rich dark chocolate lava cake. •

Golden Yunnan Buds

ORIGIN Yunnan (China)

BREWING GUIDE

→ Several successive infusions according to Gong Fu Cha method

FOOD PAIRINGS

Duck breast or dark chocolate lava cake

Enhanced with the toasted nutty notes of Mugicha, these stuffed zucchini can be served with a fresh green salad – also dressed with a Mugichainfused vinaigrette – making for a healthy and flavor-packed recipe!

Serves five

35 g Mugicha

25 g pearl barley

10 small round zucchini

1 garlic clove

2 scallions (white parts only)

Olive oil

Butter

Salt

Pepper

250 g ricotta

50 g breadcrumbs

Our grain-based teas, such as Mugicha, are just as delicious served iced or as a latte. For an iced tea: infuse 10 g of loose leaf tea in 500 ml of room temperature water for an hour. Add ice cubes and it’s ready to enjoy! For a latte version: infuse 10 g of loose leaf tea in 300 ml of your choice of warm milk. Enjoy as it is or served chilled as a refreshing summer drink.

1. Preheat the oven to 200°C.

2. Infuse 20 g of Mugicha in 500 ml of hot water (90°C) for ten minutes. Then set aside.

3. Grind the remaining Mugicha to a fine powder. Sieve and set aside.

4. Cook the pearl barely in salted boiling water. Drain and set aside.

5. Cut the tops off the zucchini and use a spoon to scoop out the flesh.

6. Chop the flesh, garlic and scallion whites.

7. Heat a little butter and olive oil in a skillet, then gently brown the zucchini flesh, garlic and scallions until all the moisture has evaporated. Remove from the heat and season to taste.

8. Add the ricotta and cooked pearl barley to the pan. Season with four pinches of the ground Mugicha.

9. Stuff each zucchini with the ricotta stuffing.

10. Put them in a baking dish and top with breadcrumbs and the remaining ground Mugicha.

11. Pour the Mugicha infusion into the base of the baking dish, to 1cm high. Bake for thirty minutes at 200°C, until the breadcrumb topping is golden and the liquid has reduced.

Serve this recipe with a mixed green salad seasoned with finely chopped parsley and scallion greens. Season with a Mugicha vinaigrette made with a neutral vegetable oil and 100 ml of infused Mugicha tea.

Afternoon tea is a quintessential English tradition. This time for tea is associated with a set of refined rituals and the tea drinking itself is a shared social experience. Originating back to the nineteenth century, this British tradition has crossed borders and is now served in many restaurants and tea rooms across the globe.

The Brits’ love affair with tea began in the seventeenth century. At the time, the first tea leaves arrived from China in small quantities, and the drink was rarely consumed.

Afternoon tea: a female affair

In 1662, King Charles II married the Portuguese infanta, Catherine of Braganza. The princess had barely arrived and she had already demanded a cup of tea, to help her recover from the long and stormy crossing. However, the drink was nowhere to be found, so instead she was offered a glass of… beer. Disappointed but resigned, the king’s young wife was in the habit of drinking tea throughout the day, and so made it her mission to spread this custom throughout the court. As part of her dowry, she brought a casket of precious Chinese teas, which she shared with her ladies-in-waiting. After winning over many, the drink became the reserve of the aristocracy, enjoyed in select circles. Considered exotic, tea was ten times more expensive than coffee at the time. However, the period is distinguished by the rise in popularity of tea rooms opening. In 1706, Thomas

Twining, from the family of British tea merchants, opened his first tea room in London. It wasn’t long until tea conquered all levels of society, as trade with China expanded. Tea was met with immense success and even ended up replacing beer as the drink of choice at breakfast.

This practice emerged later, during Victorian times. Its invention is associated with the Duchess of Bedford. At the time, dinner was served late in the evening, and so she had the idea of requesting that some tea with bread and butter be served mid-afternoon, to stave off hunger until the evening meal. She invited her friends to join, and the practice soon spread throughout English society. In the midst of the industrial revolution, this tea break was one of the first social victories for English trade unions, enshrined in workers’ rights. It was a sacred moment for workers, providing fuel during the long, draining hours in the factories. These days, afternoon tea is a social experience, time out to enjoy a cuppa (British slang short for “cup of tea”) with family or friends. The English usually drink black tea (Earl

Grey, breakfast tea, Darjeeling), brewed in a teapot and served in a cup with a splash of milk or sometimes a slice of lemon. This practice has evolved slightly over the years, and today there are two distinct variations of afternoon tea: low tea and high tea. Low tea is usually taken at four o’clock and served with sweets, like scones with jam and cakes. Meanwhile, high tea is a more substantial meal, almost like a light dinner served at the end of the day. A mixture of savory dishes are served, such as quiches, cold cuts and salads.

These two variations owe their names to the height of the tables at which it is served: low tea is served on a low coffee table, whereas high tea takes place in the dining room at the dinner table.

The concept of afternoon tea is deeply rooted in British history and culture, and offers a welcome break to bring people together at the end of the day. •

The British tradition has crossed the Channel and taken over Paris’ most stunning luxury hotels, which now serve their version of afternoon tea. This “accessible” luxury has won over epicurious gourmet diners. Afternoon tea à la française is an all-star cast of sophisticated patisseries with an original twist. For example, Matthieu Carlin uses tea as an ingredient in his pastries at the Hôtel de Crillon, meanwhile Cédric Grolet is famed for his signature trompe l’oeil creations at Le Meurice, and François Perret serves nostalgia-filled childhood classics at the Ritz. In June, the digital restaurant guide La Liste will announce the winner of its Best Afternoon Tea prize, in partnership with Palais des Thés, putting tea center stage of this gastronomic experience!

Woody, waxy and mysterious, the Darjeeling Mist Bari brings together several facets of the types of black teas most enjoyed at breakfast. Harvested in northern India in the misty Himalayas, it encapsulates the story of Darjeeling in a single cup of tea.

Although nowadays Darjeeling is considered an iconic tea terroir, it was not until the nineteenth century that this isolated region surrounded by Nepal and Bhutan became a tea-producing land. It is a relative newcomer in the history of this drink, compared to China, where tea has been produced for several millennia!

Indeed, while tea was probably already growing wildly in India in the eastern state of Assam ( Camellia sinensis assamica), the tea plants in Darjeeling are actually a Chinese variety ( Camellia sinensis sinensis). The mystery between the two is soon tied up when we look at the story of Robert Fortune (see Bruits de Palais, no 88, p.30-31). In the nineteenth century, the British botanist was commissioned by the Crown to steal China’s closely-guarded secrets of tea production, a country for whom the famous drink was a cultural marker as well as a considerable source of income. Refusing to sell to the price offered by the

British, who were becoming increasingly fond of this drink, Robert Fortune infiltrated China and kicked off his covert espionage mission. Wearing make-up and dressed up in disguise, he was able to observe how tea was grown and processed, with his aim being to illegally import tea plants and trade secrets to India, to create a new tea-producing region. During his time there, he discovered that both green and black teas in fact came from the same plant.

While his first attempt to exfiltrate crops to colonized India failed, his second trip in 1852 was a success: the stolen plants survived the journey, and once planted on the steep slopes of the Himalayas, they unleashed this cloud-covered region’s tea-growing potential.

In Darjeeling, tea is harvested between spring and fall, and each season’s harvest has its own signature taste. The Darjeeling Mist Bari possesses all the characteristics of a summer harvest tea: subtly sweet with woody,

at altitude,

waxy, chocolatey notes. Unlike first flush Darjeeling teas, it has a round mouthfeel and a lower level of astringency, offering a depth that is incredibly popular all-round.

But this tea also holds other surprises when drank, revealing notes of candied fruit and almond butter. This high-altitude black tea offers a sweet

and indulgent way to awaken the senses!

This Darjeeling goes just as well with a quick breakfast of toast and fruit as it does with a hearty, big brunch. It provides a slow burst of energy for the start of the day. This is because it is

partly composed of tea buds, as well as the fact that black teas are natural stimulants. It can also be served with a splash of milk, making for a very British afternoon tea, paired with scones, fruitcake and finger sandwiches. What better way to discover the multicultural origins of this legendary tea region. •

France’s gastronomic heritage permeates and influences our tea culture. From creating tea and food pairings, to using tea as an ingredient in both sweet and savory dishes, as well as tea mixology… these past few years, tea has increasingly played a bigger role in France’s gastronomic heritage, and become more present in restaurants, cafés, tearooms and cake shops. For years, Palais des Thés has been helping these establishments to curate their tea menus, providing bespoke advice for selecting the best teas and herbal teas to meet their needs. And this year, the company is going one step further by teaming up with the international restaurant guide, La Liste.

Last November during the awards ceremony gala dinner, our teas were served as part of a cocktail dinner with classic buffet recipes from Japan, China, Korean and France. Our teas were chosen to accompany the dessert specially created for the occasion by pastry chef Nina Métayer. Our common goal was to promote tea as a gastronomical drink and lend our knowledge and expertise to chefs who wish to showcase tea in their restaurants. In June, François-Xavier Delmas will have the honor of presenting the award for this year’s Best Afternoon Tea prize, which will take place during the Garden Party organized by La Liste.

In 2023, Palais des Thés became a patron of the museum and began supporting its work. Our contribution has helped finance the position of an expert botanist as part of its Vigie Nature citizen science program. Launched in 2006, this initiative brings together around twenty or so

biodiversity monitoring groups, made up of researchers and scientists, green space management professionals, concerned citizens and schools groups, among others.

The objective is to conduct joint biodiversity data collection (recording flora and fauna development in France) over the long term, for research purposes and to support government and public body decision-making. This approach requires active public participation. More than forty thousand people have already taken part, sending their data and findings to researchers at the museum. Ania Schleicher is the botanist in charge of coordinating the flora-related observatories. Her work focuses on wildflower obser vation and monitoring programs in France (Florilèges, Vigie Flore, and Sauvages de

ma rue). To ensure these three projects flourish, her daily tasks include training the general public to become better observers, providing support to people who manage urban green spaces, presenting the collected results, and organizing meetings regionally and nationwide, as well as workshops to improve the observation protocol. These initiatives are extremely important to us. We are incredibly delighted to be supporting them, especially at a time when environmental conservation education is a major issue.

→ For more information, visit: vigienature.fr

Make your own gift box in store!* Mix and match whatever takes your fancy, filling three forty-gram tins of your choice of Grands Crus teas.

Harou cup (28 cl)

→ Ref. N344 – € 18

Grands Crus gift set

→ Ref. DGC1 – € 42

Mosaic cup (16 cl)

→ Ref. N343 – € 26

Yakushima cup (16 cl) → Ref. N345 – € 15

With its colorful new makeover, our iced tea collection is sure to keep you cool now the sun is finally here. These extra-large iced tea pouches are easy to use to brew up a pitcher, anytime, anyplace! Are you ready for a refreshingly fruity summer?

€ 6.90 per berlingot

1. ORGANIC Icy Peach

→ Ref. DTG8370N

2. ORGANIC Summer Fizz

→ Ref. DTG832N

3. ORGANIC Tropicolada

→ Ref. DTG8430N

4. Exotic Party

→ Ref. DTG814N

5. ORGANIC Bahia

→ Ref. DTG8460N

Iced tea pitcher

→ Ref. M208 – € 38

Iced tea tin*

Fill with your choice of iced tea

→ Ref. V423 – € 6

Bruits de Palais is a Palais des Thés publication

Editorial team

Lucile Block de Friberg, Bénédicte Bortoli, Mathias Minet

Translation and proofreading Kate Maidens

Art direction and layout

Prototype.paris

Styling

Sarah Vasseghi

Illustrations Sabine Forget Imaging & retouching services

Key Graphic Palais des Thés

All translation, adaptation and reproduction rights in any form are reserved for all countries.

Photo credits François-Xavier Delmas: p.1011, 12, 20-21, 22, 23, 24, 33 • Guillaume Czerw: front cover, p.2, 4, 15, 26, 27, 29, 36, 37, 38, 39 • Karuna-Shechen: p.6 • Kenza Benkhatar: p.13 • Anna Miyoshi: p.25 • Kenyon Manchego: p.33 • MNHN - J érôme Munier: p.34-35.

Customer service

+33 (0)1 43 56 90 90

Cost of a local call (in France) Monday to Saturday 9am-6pm

Corporate gifts

+33 (0)1 73 72 51 47

Cost of a local call (in France) Monday to Friday 9am-6pm

“Drink your tea slowly and reverently, as if it is the axis on which the whole earth revolves – slowly, evenly, without rushing toward the future.”