09 Defining Sethism Asif Saad

12 Jahangir Siddiqui will soon own two banks. Not everyone is happy

17

17 Pakistan’s economy under Musharraf Dr Ishrat Husain

21 Calling a spade a spade; Is Capital Value Tax the new wealth tax? 23

23 Mera bank, meri marzi

26 Have car prices sleepwalked into no-man’s land where nobody can afford them anymore?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Chief of Staff & Product Manager: Muhammad Faran Bukhari I Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Ariba Shahid I Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Ahtasam Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

by Sethism

Ask economists and planners what ails the economy; the general response would be in fiscal and monetary terms. What is not so well understood are the detrimental behaviours exhibited by our society as a whole. This piece attempts to define one of the significant ones - the affliction of being a Seth.

I am taking the liberty to add ‘ism‘ to ‘Seth’ to best describe the specific personality traits or symptoms which need to be understood to be able to diagnose those with this disease. Before I share the symptoms, let me say that I have many friends and acquaintances who are business owners and who are not plagued by Sethism.

In fact, Sethism is not limited to business owners. There are strong candidates for this affliction within the ranks of politicians, important institutions, bureaucrats, corporate executives, doctors, lawyers, accountants, and many other professions. In fact, many senior members of these honourable professions exceed business owners in many of the following aspects.

Hence, it is to be kept in mind that the disease is widely spread and treatment may require a broad national consensus.

The writer is a strategy consultant who has previously worked at various C-level positions for national and multinational corporations

What follows is a list of symptoms displayed by those diagnosed with Sethism.

It was Steve Jobs who said, “It doesn’t make sense to hire smart people and then tell them what to do. We hire them so they can tell us what to do.” The local Seth is unfortunately ignorant of such wisdom.

Those who have worked for Seths, will tell you that the Seth proceeds to define exactly what you need to do to be of service to them. There should be no problem with that as professional managers do the same and it is good that there is clarity on what is expected. In any case, Micromanagement is prevalent in many organisations so this is no big deal.

But then, soon after, the next step emerges – you will now be told about how and when you are expected to do what you need to do. Let me illustrate with a hypothetical, but typical, Seth-driven process;

You are a top manager in an organisation that needs to hire against a vacancy. You are expected to do so and the same is agreed in a discussion with the Seth.

A few hours later you will receive a voice note saying please interview Mr Xyz. You think Xyz would be one of the candidates so, yes sure, you will consider them.

You will then receive the next voice note in the next 30 minutes that Mr Xyz is willing to join and will cost Rs xx per month and is also available to start by such and such date.

You are also asked to meet Mr Xyz and finalise the deal. And of course, you can share your opinion!

To describe a Seth as having a good memory is an oxymoron. A Seth is incapable of remembering what they have said in the past. This is a pure DNA requirement and you cannot qualify to be a Seth if you are able to recall the past, especially your own words. If a Seth remembers, he will not be able to change track when it suits him and this is considered a fundamental flaw in Sethism. A Seth must think differently in the evening about the same subject as they did in the morning. This morning-to-evening-to-night shifting of opinions keeps people around them guessing and then agreeing to completely opposite positions – at times within a matter of a few hours.

Besides the well-understood issues of capital constraints, budget deficits and lack of planning, the economy is chained

People who believe in shifting positions and quick U-turns would easily pass the Sethism test.

The Urdu idiom “kaan ka kacha hona” fits the Seth mentality better than my English translation in the caption above. This connects to the point about taking U-turns, Seths tend to agree with anything and everything they hear, This is probably because they don’t really

listen or do not consider anyone else’s opinion important. They will nod their heads and proceed to act from the latest bit of information their brains acquire.

They do not have principled positions and long-term views about much in life.

You cannot disagree with a Seth. A Seth has attained much in life and is full of wisdom, and the need for selfpraise is hardly required when there is an army of people sucking up.

Disagreeing with the Seth is taken as a mark of disrespect. Especially if this is done in the presence of other people. Meetings with Seths and their teams are mostly occasions described via the parable of the emperor without clothes!

The Wharton professor Adam Grant calls the HIPPO (highest paid person’s opinion) the most dangerous for organisations.

By the way, HIPPO also corresponds to its animal namesake known for having a big mouth and little ears meaning that they are prone to talking much and listening less.

This is one of my favourites. Seths do not have the time or inclination to be comfortable with information technology, with one exception – the whatsapp voice note! It is amazing to see how proficient they are with Whatsapp voice notes and I sometimes wonder what they would have done if it was never invented.

Unfortunately, its invention has meant that Seths do not need to read or write or indulge in any habits which could help them reflect and review their thinking.

The attention span of a Seth is limited largely because they believe in consistent multi-tasking. They have limited time available for any single subject and refrain from in-depth understanding of any subject.

The lack of focus and depth means their impact will be limited and one would not expect them to build anything truly meaningful and sustainable.

I am sure there are several other symptoms, and I could go on. However, I hope readers are now aware of what to look for and can uncover the rest themselves.

Encyclopedia Britannica describes Seth from Egyptian mythology; “Originally Seth was a sky god, lord of the desert, master of storms, disorder, and warfare — in general, a trickster. Seth embodied the necessary and creative element of violence and disorder within the ordered world.”

Apparently, our Seths have drawn from this description when practising destructive behaviours. If the land of the pure is to find solutions to its economic malaise, it must also find a cure for Sethism, sooner rather than later. n

Owning a bank is a pretty big deal, even for the very rich. This is true not just in Pakistan but all across the world. But getting your hands on one isn’t quite so easy. Just look at Malik Riaz of Bahria Town fame, who by some accounts is Pakistan’s richest man. Riaz has wanted to buy a commercial bank since the early days of his ascent but has seen his efforts blocked on account of not having a ‘clean’ enough reputation to be trusted with depositor’s money. And he isn’t the only one. Albeit for different reasons, Habibullah Khan of Mega Conglomerate, a self proclaimed Pakistani billionaire’s bid to acquire Meezan Bank in 2013 was also shot down by the regulator. And much like this, every Pakistani billionaire has either tried to or dreamed of owning a bank at some point or the other. Very few have managed.

And yet, here we have Jahangir Siddiqui, the owner of JS Bank and a leading stock broker, who

in BankIslami, is about to buy his second commercial bank. If the transaction goes through, Siddiqui, according to one interpretation of the banking law, will become the first to own and operate two Pakistani commercial banks at the same time.

Naturally not everyone is particularly happy about this. It is illegal to own two commercial banks, and it seems that the attempted acquisition will now go through legal proceedings. At the forefront of this battle is Aqeel Karim Dhedhi — another leading Pakistani stockbroker whose legendary rivalry with Siddiqui is well-recorded. And while the antagonism between the two stockbrokers meant it was always a foregone conclusion that Dedhi would go to court over the BankIslami issue, it seems he is not alone.

Dhedhi’s crusade has been joined by a number of voices in the financial industry that suspect Jahangir Siddiqui is manipulating loopholes in our securities regulations to snuff out minority shareholders. Put in so many words: foul play. And unlike Dhedhi, these voices seem to have no personal scores to settle with Siddiqui or his JS Group.

There is a very technical legal question at the centre of this story. Because at the end of it it boils down to this: can one man own two banks? The jury is still out on the answer with the court case being fiercely contested in the Sindh High Court (SHC).

Essentially, the case hinges on two points. The first is very simple: that Jahangir Siddiqui is not fit and proper to buy a bank. According to the case filed by Dhedhi, Siddiqui is a controversial person who has been accused of many fraudulent activities and hence like Malik Riaz, should not be allowed to own a bank in the first place. Dhedhi obviously forgets to mention that it was Dhedhi himself who had made most of these allegations against Siddiqui in the first place. Not to mention that Siddiqui already owns a bank which means the State Bank has once before screened and greenlit his ownership of a bank.

This is the simpleton’s argument. It is a polemical point made a part of legal proceedings simply to irk the opposing party. The real question can be found in the second part of the case where Dhedhi points out that according to the banking laws of Pakistan, one business group is not allowed to own two or more competing banks.

You see, normally when a bank buys another bank the two financial institutions merge into one entity.. But unlike previous M&As in the banking industry, Siddiqui does not plan to merge BankIslami into his JS Bank. Instead he plans to continue running BankIslami as BankIslami, i.e. completely separate from JS Bank. The only commonality between the two banks would be the sponsor shareholder, the JS group which inturn means Jahangir Siddiqui himself.

For now, the court has granted Dhedhi a stay order until the next hearing, which is due today (Monday, 20th of March). But that’s the easy part. Courts are quite liberal with handing out stay orders and halting progress on all manner of things until they make up their minds. What is important, however, are the legal arguments that will be presented in the courtroom over the next few weeks. Because as far as the law goes, it is illegal for one business group to own two banks. But is it?

Take the example of Mian Mansha, who also owns two banks in the shape of MCB Bank and MCB Islamic Bank. Now, while this is an example of one person owning two banks, it works because the SBP in order to encourage islamic banking in Pakistan, does allow all conventional banks to open new Islamic banking subsidiaries as separate legal entities. And this is exactly what Mansha had done when he had

opened his MCB Islamic bank as a fully owned subsidiary of his main bank, MCB bank.

Jahangir Siddiqui is relying on the same principle. Since BankIslami is an Islamic bank that is being acquired by JS Bank, the JS Group should technically be allowed to buy the bank. However, Dhedhi in his court case against the acquisition has claimed that this technicality does not hold because the rules do not allow for one bank to buy an already established bank and make it into its subsidiary, even if the bank being bought is an Islamic bank. The exception is for setting up a new legal entity Islamic Bank, not for buying an existing one.

The question is both the letter and spirit of the law. On the one hand, there is an exception that allows the same group to own two banks if one of those banks is an Islamic bank. However, the purpose behind that exception is to promote the introduction of new Islamic banks. In the acquisition of BankIslami, JS Bank is simply buying an existing Islamic bank and not introducing a new lender in the system.

The JS Group obviously finds Dhedhi’s interpretation completely frivolous. According to them, as far as the law is concerned, there is no difference between opening a new Islamic bank subsidiary, or buying an existing Islamic bank and converting it into a subsidiary company. Both are allowed. Obviously, there would have been no question of interpretation had Jahangir Siddiqui acquired a conventional bank and tried to run it separately, as a subsidiary of his JS Bank. That would clearly not have been allowed. The JS Group and its legal team seem confident that the objections raised by Dhedhi will soon be dismissed by the courts and the transaction will go through as planned.

But this isn’t where it all ends. While the legality of the acquisition itself is being challenged in court, there are others in Pakistan’s finance industry that are pointing towards much bigger problems in this transaction. In fact, claims have been made that the JS Group through stock price manipulation and regulatory capture done with the connivance of the corporate regulator and the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) management are shortchanging minority shareholders of

BankIslami.

However, to understand the basis of these very serious assertions, we first need to understand some specifics of this deal, as well as the regulations that govern such deals, and the recent changes made to these.

Let’s start at the beginning. What does it look like when you try to buy a bank? Imagine you are the owner of a big business group, and one day you decide to enter Pakistan’s islamic banking industry. But starting afresh is not your style, so you decide to try and buy a 51% controlling stake in BankIslami, the third largest Islamic bank in the country. The bank has a total of a billion plus shares, only some of which are regularly traded on the stock exchange.

You do your homework and notice that approximately half of the total shares are owned by four big shareholders, while the rest of the half are owned by 20,056 shareholders, most of whom own only a few hundred shares each. The only real way to go about acquiring the 51% shares is to go to the four big shareholders. The only other route would involve your broker first buying all the shares available on the PSX followed by approaching the tens of thousands of sellers that aren’t active on the stock market.

This would mean that very quickly shareholders would realise that there is a big fish in the market, and the price of the share would skyrocket. The ones selling the last lot of shares required to get you to 51% majority shareholding are the most difficult to convince. In all likelihood, you fail to get majority shareholding or get it at a very steep price.

The preference of the acquirer is always to convince a few big shareholders of the target company and strike a deal with them instead. These large shareholders are usually the sponsors and directors of the target company, and it’s just so much easier and also cheaper to get majority control this way. The acquirer would normally offer them a reasonable premium over and above the market value of their share and if they agree to sell, that’s that.

But is it? It would be wise not to jump the gun since this would also mean the smaller

“We have no comments on this matter at this point in time”, Farrukh H. Khan, CEO PSX

shareholders of any company would almost always lose out on these once in a lifetime opportunities that offer an exit at a premium above the market price. And the good news for the minority shareholders is that the Securities & Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), the company’s regulator, does not like this. And it has a law that ensures that the minority shareholders also get an equal opportunity to exit at a premium in such takeover bids. Basically the acquirer can make all the one-on-one deals it wants with the big shareholders, but the SECP still binds the acquirer to also make an offer to purchase at least half of the shares held by minority shareholders.

So in the case of JS Bank’s bid to acquire majority shareholding of BankIslami, JS Bank has already announced that it has a deal with two big shareholders of BankIslami, namely the Randeree family which owns 19.5% and Jahangir Siddiqui and Co Ltd, which is also the holding company of JS bank and owns 21.3% of BankIslami. Now JS Bank itself already owns 7.8%, and we all add all three up, it takes JS Bank to 48.6%. Just a little short of the magic number of 51%. This is where the deal with Sumya Developers, a relatively small shareholder with 1.7% stake of BankIslami comes in. Assuming all regulatory approvals come in, this would take the tally to above 50%, allowing JS Bank to have majority control of the islamic bank. This is where that SECP law meant to protect minority shareholder rights comes in. You see, despite JS Bank already having struck deals for majority control and thus not needing to buy more shares from the other 49% shareholders, this law would still force JS Bank to make an offer to acquire a minimum of 50% of the remaining shares, owned mostly by small shareholders.

Not just this, the law also dictates a minimum price per share that the minority shareholders are to be offered, and this price can not be less than what JS Bank had agreed to pay to three majority shareholders. But that would still leave the possibility that the acquirer, in this case JS Bank, and the majority shareholders under-declare their deal price to the SECP. To address this, the price offered to minority shareholders is calculated using five different methods, and the method that gives the highest price is the one offered to the minority shareholders.

Common sense would dictate that since every shareholder, whether small or big, is offered the same price and that shareholders have a right to either accept to sell at this price or refuse and stay on as a shareholder, there should be no reason to worry about mistreatment to the minority shareholders or for that matter any shareholder in any such acquisition deal. However, in reality there remain many loopholes, and amazingly the main one was added in our companies takeover regulations as recently as September 2022.

Up until September 2022, if minority shareholders opted to sell their shares during an acquisition they were to be settled in cash. However the new amendment allows acquiring companies to decide whether they want to settle the price decided through the above mentioned mechanism through cash or in kind. This one change has potentially rendered the whole exercise of mandatory public offerings redundant. And JS Bank was the first to take advantage of this, raising suspicions as to whether these changes were made by SECP on purpose to please the JS Group in particular. When Profit asked SECP for the reason for this change in takeover regulations, it said, without giving any reference, that it was done to align the regulations with the Securities Act of the country. So how exactly was the new regulation exploited?

If JS Bank wanted to avoid buying shares of BankIslami that the SECP is mandating it to, one way could have been to offer a really low price that would have been unacceptable to the sellers. But as explained earlier, because of the very thorough process in place to determine the minimum price that needs to be offered to the remaining 49% shareholders of BankIslami, JS Bank had to think of some other strategy to circumvent having to buy more shares than it wanted.

The good people at JS Bank must have said to themselves: so what if the regulations do not allow us to give a low offer for BankIslami shares? We could still make it a bad deal for the minority shareholders by offering them shares of unwanted companies instead of offering them the usual cash. All thanks to the new change in regulations that allow for in kind payment.

So on March 7th that is exactly what JS did. The bank disclosed to its shareholders that instead of cash, it plans to offer shares of JS Global Limited

and JS Investments Limited, both group companies, to the other 49% shareholders of BankIslami. There are three problems with these two shares that make this offer a very bad one for BankIslami shareholders and is equivalent to taking away their legal right to benefit in a takeover bid.

Firstly, the shares of both JS Global and JS Investments are largely illiquid, meaning it would not be easy to sell them in the market. Secondly, both these companies are not Shariah compliant, meaning offering such shares against shares that are Shariah compliant might be a non-starter for many shareholders of BankIslami for religious reasons. Lastly, and probably most importantly, the price of JS Global shares have increased by an astonishing 4 times since the last three months, while the price of JS investments shares has also increased substantially during this period. This would mean that in an exchange,a shares of both these companies would have a higher value than usual and shareholders of BankIslami would get fewer shares of JS Global and JS Investment, were they to opt

for the exchange.

Profit reached out to JS Group to enquire for the possible reasons for this steep increase in prices of these shares, despite the overall bearish sentiment in the PSX, but they chose not to respond. Profit also reached out to Farrukh H. Khan, the CEO of PSX, to ask why, unlike their usual practice, in this case the PSX has not asked the companies concerned to give reasons for this unusual increase in their share prices. A one line response was received: “we have no comments on this matter at this point in time”.

Let’s take a recap of the situation:

Jahangir Siddiqui’s JS Bank is on a mission to acquire a majority shareholding in BankIslami and make Jahangir Siddiqui the first person to own two commercial banks in Pakistan at the same time. On the path to that mission, JS Bank is fighting off a court case that claims one business group cannot own two banks at the same time and that Siddiqui is exploiting a loophole for Islamic Banking to get his way. And that isn’t the only loophole being exploited: recent changes in SECP regulations have left minority shareholders shortchanged once again through technicalities.

The JS Group and JS Bank have not responded to Profit’s queries despite multiple attempts to reach them. However, to understand the decisions being made at JS, your correspondent spoke to a number of industry experts and gathered some background information to craft what a hypothetical reply in support of Jahangir Siddiqui and his group would look like:

1. The thing to understand is that this is not a delisting transaction in which shareholders have no other choice but to accept the price being offered to them.This is true even if the shareholders feel that they are not being compensated fairly. In this case Bank Islami’s shareholders are being given an option to sell their shares if they wish to. If some, or even all of them feel that they are not getting a good enough price or do not like the ‘in kind’ option of payment, they are absolutely free not to sell. No one is forcing them.

2. BankIslami is a good share and after the majority acquisition by JS Bank, there is no reason that the share will not perform even better. The folks over at JS are also likely to point towards the example of the Zindagi App by JS Bank, which has successfully transformed a brick and mortar bank into a truly digital bank. No other bank has been able to do this. They have invested a lot of money and effort in making this state of the art app, and with BankIslami becoming a subsidiary of JS Bank its customers will also benefit from the tech plat-

form created by them. This could be one of the examples JS Bank uses to claim that BankIslami shareholders will in fact greatly benefit from this acquisition.

3. All this ruckus is being created by only those shareholders who bought BankIsami’s shares only to make a quick buck. You see, as soon as the market realised that JS Group was interested in buying majority shareholding in BankIslami, some greedy players in the stock market started buying shares of BankIslami and drove up its share price. They thought that when JS Group would make a public offer, which it is mandated to do as per SECP regulations, they would sell these shares at a higher price to the acquirer and make a quick buck. Now this quick buck would have been made at the expense of shareholders (both majority and minority) of JS Bank.

What these people did not realise was that regulations had recently been changed which allowed for in kind payment now. So now that JS Bank was legally allowed to make a public offer in which it could pay BankIslami shareholders with shares of listed companies that JS Bank owned, instead of using its own cash, it was only prudent that JS Bank used this newly available option. Had JS Bank offered cash to acquire these shares, they could reasonably say it would have violated the fiduciary responsibility of JS group towards its shareholders. This is especially true in a high interest rate environment where this cash could have been deployed much more profitably, say in government bonds which are paying record high returns.

4. This obviously means that the bet made by some investors on BankIslami shares did not pay off. But like in every transaction there are winners and losers. It is important to note that this was all done as per the law and if the law allows something it is natural for companies to make the decision which is in the interest of their shareholders, as long as it is within the law.

So what have we learned? The JS Group and JS Bank are awfully quiet about their controversial attempt to buy BankIslami. And while some of the mud is being thrown by old rivals, there are genuine concerns and possible responses from the JS Group.

The case is for the courts and the regulators to decide. However, the attempt to buy BankIslami may not go down even less smoothly than had already become evident. According to a response received by Profit from the SECP, the regulator is “reviewing its rules

and regulations on an ongoing basis”. While the commission, despite being specifically asked, did not clarify further whether they would make any changes before or after the JS deal, there is clearly room still for the SECP to throw a spanner in the works.

Pakistan is not the only country where an offer for in-kind returns to minority shareholders during an acquisition is legal. However, there are ways to avoid acquirers exploiting the situation. But since the SECP has not been clear on the issue, it is anybody’s guess whether Jahangir Siddiqui will be able to squeeze out of this loophole or be pushed back with a slap on the wrist.

Because at the end of the day this entire episode is far from squeaky clean. Even if one believes the argument that there was no regulatory capture by JS Group or other future beneficiaries of this change in regulation, there are some issues that even Profit’s pro bono devil’s advocate could not explain.

It could not explain the astonishing increase in the share prices of JS Global and JS Investment in the past few months, especially considering the performance of the overall stock market. It could not explain why Jahangir Siddiqui Co Limited would accept only 1.138 shares of JS Bank which are trading at less than Rs 5 at the moment, in exchange for every share of BankIslami presently trading at close to Rs 11 in the market.

Then there is also the little issue of JS Bank and the big shareholders they are in partnership with hiding the value of their transaction. For example, the Randeree family is accepting to sell their shares in BankIslami presently trading at Rs 11 in exchange for 1.138 shares of JS Bank trading at less than Rs 5 at the moment. Considering that the Randeree family had recently bought some of the BankIslami shares from Emirates NBD at Rs 13.24, it defies logic that they would now want to sell them for shares worth less than Rs 5. Suspicions that there could be a side deal with the Randeree family and others that have not been disclosed to the exchange and to the regulators, can not be wished away.

The acquisition effort finds itself in some truly choppy waters. On the one hand, old rivals have blocked them on one front and held up JS Bank’s attempts to buy in court. In the meantime, all of the problems associated with the deal have come to the fore. To opponents like Dhedhi and others in the financial sector raising questions, this is an example of shady practices. To those vouching for JS Bank, it is an example of a wily business group managing to get the timing right and use institutional loopholes to their benefits. Now it is simply a matter of waiting and seeing what the courts and the SECP decide. That is what will decide whether Jahangir Siddiqui can pull this off. n

Economic achievements in difficult circumstances during former president Pervez Musharraf‘s regime are dismissed outright because of abhorrence of the military rule, imposition of the emergency in 2007, his decision to join the US in Afghanistan War, open tussle with the judiciary, withdrawal of corruption cases against politicians, and his quest to get elected in uniform. This column is an attempt to provide a first-hand, data-driven account of the economic record of the period 2000-2008.

Pakistan suffered serious setbacks in the 1990s in terms of economic and social indicators. Economic growth rates decelerated, inflation rose to peak rates, debt burden escalated substantially, macroeconomic imbalances widened and worst of all the incidence of poverty almost doubled. Pakistan’s credibility in the international financial community was at its lowest ebb as successive agreements concluded with the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) were not implemented. Foreign investors were unhappy as all power purchase agreements were being re-examined and criminal action was initiated against Hubco.

The situation exacerbated after the nuclear testing in 1998 when sanctions were imposed on Pakistan. External liquidity had dried up due to freezing of foreign currency deposits of $ 11 billion held by resident and non-resident Pakistanis. The loss of confidence evaporated workers remittances, foreign investment

and foreign currency deposits. The assumption of power by the military government in October, 1999, led to fresh sanctions, and bilateral and multilateral official flows were suspended. Credit rating agencies downgraded Sovereign Credit of Pakistan to the Selective Default category, and therefore the door for access to financial markets was shut down. The country faced a gap between external receipts and payments of $ 2.5 to 3 billion annually for the next five years. The new cabinet had to face this crisis i.e how to meet its current obligations such as imports of goods and service, its debt service obligations and other payments with almost no reserves. To fill in this gap and keep the wheels of the economy moving Pakistan had to get its debt service obligations rescheduled for which it was imperative to have an agreement with the IMF.

Pakistan entered into a stand-by arrangement with the IMF in 2000 for a nine-month period followed by a three-year Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF). For the first time in the history of Pakistan the IMF was able to complete all reviews successfully and released all tranches on time. The credibility of Pakistan vis a vis international financial institutions was restored setting the stage for a re-profiling of Pakistan’s external debt owed to Paris Club. This re-profiling of bilateral debt resulted in the reduction of external debt and liabilities as the percentage of foreign exchange earnings from 224% to 125% and debt servicing from 26% to 9%, saved $ 1 billion annually for an extended period of time.

Pakistan’s economic performance under Musharraf was impressive in terms of income per capita, employment generation and poverty alleviation. As a result of a reasonably high GDP growth rate of about 6.3% a year the per capita income in current dollar terms rose to about $ 1000. The Headcount Poverty ratio fell from 34% to 15%. Unemployment rate also fell from 8.4 % to 6.5%, and about 11.8 million new jobs were created. Gross and net enrolment at the primary level improved and health indicators such as children immunisation, incidence of diarrhoea and infant mortality showed favourable changes.

There are at least five strands of criticisms of economic policies pursued during the Musharraf era. It is therefore necessary to address each one of them with the aid of hard-published data.

First and foremost, it is the post-2001 massive capital flows of official aid from the US, other bilateral and multilateral sources that is responsible for the exceptional growth recorded during this period. The annual gross flows from all official bilateral and multilateral sources

received between 2002 and 2008 accounted for 8.5 % of Pakistan’s total foreign exchange receipts (the US provided 4.5% of this total) . The remaining 91.2% of foreign exchange receipts were generated by exports, remittances, and Foreign Direct Investment.

Thus, the impact of these capital flows is highly exaggerated as the amounts received are no different from the historical record of foreign assistance or subsequent acceleration of US assistance under the Kerry Lugar bill. The annual net official assistance between 2009-2014 was $ 2.8 billion compared to $ 1.6 billion between 2002-2008. A British researcher found that “the statistical evidence failed to relate these US aid capital inflows with savings and investment, expenditure, imports, domestic and external debt, corporate profitability and boost in public investment. The episode of growth was better explained by a stronger government able to mobilise domestic resources, ensure that they were utilised productively and create institutions that were able to overcome the conflicts associated with economic development”.

The second popular perception is that Pakistan’s debt reprofiling was made possible by the US because of September 11, 2001 events. As a matter of record, the broad contours of this arrangement were agreed with the IMF and Paris Club long before September 11 as Pakistan had successfully implemented the standby agreement with the Fund establishing its credibility and becoming eligible for their medium-term facility. It is true that the formal agreement was signed in December 2001 but the lead time because of extensive preparation, negotiations and building consensus of 20 members of Paris Club had taken almost a year.

Third, there are those who argue vociferously that Musharraf did not take advantage of debt relief and did not focus on any structural reforms, oversaw Pakistan spending beyond its means and that the growth was fueled by consumption.

What does the evidence show?

Investment/GDP ratio touched 23% which was the highest in Pakistan’s economic history and has since then revolved around 15%. The structural reforms consisted of fiscal consolidation by raising tax revenues, reducing expenditures, cutting down subsidies and containing the losses of public enterprises. Tax reforms were undertaken to widen the tax base, remove direct contact between taxpayers and tax collectors, introduce value-added tax as the major source of revenue, simplify tax administration and strengthen the capacity of the Central Board of Revenue. The adoption of universal self-assessment followed by random audit of selected tax returns, automation and reorganisation of the

tax machinery helped tax collection to double in five years.

To tackle external account weaknesses, trade policy reforms and liberalisation helped the country in earning foreign exchange through non-debt-creating flows. Exports of goods almost tripled from $7.8 billion to $ 21.2 billion, along with a six-fold increase in workers remittances ($1 billion to $6.5 billion). Foreign exchange earnings almost tripled from $ 16.8 billion to $ 46.0 billion. Tariffs on imports were rationalised and brought down to average 7.6%. FDI inflows touched $ 5 billion in each of the last two years and foreign exchange reserves rose from $ 991 million to $ 14 billion covering six months’ imports .

An aggressive privatisation plan of state-owned enterprises in oil and gas, banking, telecommunications and energy yielded $ 3 billion. The privatisation of Habib Bank, United Bank, and Allied Bank – three large nationalised commercial banks of the country transformed the banking sector into an efficient, privately owned and managed sector. Private sector credit grew at an average rate of 25% annually. At the same the central bank was granted autonomy and its capacity strengthened. Banks became profitable, non-performing loans were reduced substantially, and interest rates fell significantly. Capital market capitalisation rose eight times and 60 new IPOs were listed and 48 corporate debt bonds issued.

Oil and gas, telecommunication, media and civil aviation sectors were deregulated. New gas fields operated by private sector companies added new capacity to meet the growing energy needs of the country. Power generation exceeded the demand and relied predominantly on domestic fuel i.e. natural gas thus saving foreign exchange. Telecommunication witnessed a boom since private sector companies were allowed licences to operate cellular phones. Telephone penetration rate reached 50% with 70 million subscribers.

The cornerstone of the governance agenda was the Devolution plan which transferred powers, responsibilities and financial resources from the federal and provincial governments to local governments headed by elected representatives. A new Police Order replacing the 19th century law was passed to modernise the force. The National Accountability Bureau (NAB) was established under a new legal framework as the main anti-corruption agency.

Fourth, some economists are of the view that the loose monetary policy stance of SBP resulted in overheating of the economy and led to inflationary pressures. It is true that the monetary policy in initial years managed to

kick start the economy when it was trapped in low growth-low inflation equilibrium. Until FY 2005 inflation remained subdued (the average rate for first five years was slightly below 4%) but subsequently the inflation target slipped due to the uptrend in the global commodity prices as well as inefficiencies of wholesale and retail markets.

As soon as there were signs of upsurge in inflationary pressures, interest rates were raised and monetary policy tightened. Other macroeconomic indicators also did not provide any signs of overheating as the fiscal deficit was contained between 3 to 4% and the current account was in surplus for three consecutive years and in negligible deficit in the next two years. Domestic productive capacity in agriculture and manufacturing had been expanding and thus supply shocks were not imminent. Excess demand therefore did not spill over into higher imports which were in any case financed mainly by non-debt creating flow. How can one, in the weight of this overwhelming evidence, read overheating of the economy?

Finally, it has been surmised by some economists that the exchange rate was artificially fixed for over six years. The data on Real Effective Exchange rate for this entire period does not show any such indication as it hovered around 100 deviating from the mean by 5 percentage points. Exchange rate can be defended by the SBP only if it is burning its reserves. In this period the situation was quite the opposite. Foreign exchange reserves were accumulating at a rapid pace because of huge inflows of export earnings, remittances and FDI, official grants and relief on account of debt servicing rising from $ 0.9 billion to $ 14 billion. The SBP had the difficult task of avoiding appreciation of the exchange rate, thus hurting exporters, and had to sterilise these foreign inflows.

It is, however, true that the policies pursued in 2007/08 did leave the economy in a parlous state. The momentum of growth slowed down due to derailment from the past track. Fiscal and current account deficits did widen leading to excessive borrowing, resulting in expansion in money supply, shrinking foreign capital inflows, intensifying inflationary pressures to reach double digits, and exchange rate coming under pressure as foreign reserves depleted. Both agriculture and large-scale manufacturing performed poorly. International prices of food and fuel were not passed onto the consumers because of political considerations in an election year. This expediency cost the country another round of the IMF programme which the new government had to enter in 2008. The lesson is that delayed and postponed decisions bring with them avoidable grief to the economy.

“Tax the rich’’ has always been a popular political slogan that resonates with a lot of people. And why shouldn’t it? The rich have an excess of money available, tax them and put the money to good use.

It’s not long before this thought leads one into a utopian realm of equity, of a society where the economic system offers the same facilities to both rich and poor. Everyone has enough, everyone is happy. But this thought cannot germinate for long. For starters, the rich do not want to be taxed. And more often than not, the rich get what the rich want. And then there is another problem. You can’t make the rich angry. Especially if you are a country that is desperately in need of capital. Private investment is the only way you will be able to crowd in wealth, so the poor can eat scraps of that wealth to survive. And most importantly, rich or poor, the idea of taxation has to have some importance. There needs to be a standardised imposition and enactment of taxes whether they are considered to be progressive or not.

In the last one year, Pakistan has seen all kinds of new taxes. Most of these were claimed to be for the rich. In the Finance Act 2022, the government of Pakistan imposed a Capital Value Tax on local and foreign assets of taxpayers. What seemingly had good intentions, turned out to be just a whole lot of confusion. In imposing the tax, the government forgot not only the nitty gritties of jurisdiction and nomenclature, but also the best interest of the country.

The problem starts with the very name of this tax. The tax is called a Capital Value Tax (CVT) but it taxes much more than just the capital value of the asset. For this we first have to understand what CVT means.

Globally, CVT stands for an amount payable by individuals, firms and companies which acquire an asset by purchase or a right to use for more than 20 years. The tax is levied on the recorded value of the asset at the time of the transaction. Say you buy a house today, and you are not a real estate broker. Traditionally, the seller would pay a fixed rate of tax, called CVT, on the value of that house at the time of the purchase.

CVT was first introduced in Pakistan in 1989 as part of the Finance Act. The tax was levied on the sale, transfer or gift of immovable property, such as land or buildings.

Wealth taxes on the other hand are a completely different concept. They are a tax measure aimed at disincentivising the accumulation of wealth. The major difference between wealth taxes and capital value taxes is that wealth taxes are supposed to be incremental. The higher the wealth, the higher the tax.

Pakistan has a history of both CVT and wealth taxes. In the Wealth Tax Act, 1963, tax was levied on the net wealth of individuals. Meaning that tax was levied on the amount left after subtracting liabilities from assets. Ever since 2002, Pakistan has not had a wealth tax. Economic experts believe that the wealth tax was abolished because of strong resistance from big real estate owners, including military personnel.

The current confusion exists because the current tax is a retrospective measure. As per Section 8 of the Finance Bill 2022: “A tax shall be levied, charged, collected and paid on the value of as-

sets at the rates specified in the First Schedule to this section for tax year 2022 and onwards.” In the first schedule, this tax is estimated at 1% of the fair market value of these assets.

Basically what this means is that anyone who is in possession of immovable and movable assets in the tax year 2022, is supposed to file and pay the taxed amount on that asset, regardless of whether that asset was traded or not. Since it is not levied upon the transfer of asset, rather it is being levied upon the mere holding of that asset, it could better be characterised as a wealth tax. However, while talking to Profit, Adjunct Faculty Member LUMS and tax law expert, Dr Ikramul Haq stated that it could be better understood as a tax on the “notional gains”.

“It is quite absurd, the manner in which this tax is imposed. Since the element of cost is missing it cannot even be categorised as a wealth tax, and similarly no transfer is being made, hence, CVT isn’t fit either,” said Ikram.

The level of public debate in Pakistan is such that even if the government imposes an outright wealth tax, the majority would not have opposed it. However, the current regulations are nothing if not a comment on competence and policy homogeneity.

Abig part of the public debate in Pakistan revolves around the devolution of powers to local governments and provinces. This is exactly the reason why the 18th Amendment was brought about. Ever since that amendment, it has been the province’s right to tax immovable property.

After the 18th Amendment, the federal government cannot levy wealth tax, CVT, Capital Gains Tax (CGT) or any tax under any nomenclature on immovable property as this is within the exclusive domain of the provinces.

Entry 50, Part I of the Federal Legislative List (FLL), Fourth Schedule to the Constitution [hereinafter “Entry 50”] gives exclusive power to provincial assemblies to levy “taxes

on immovable property”. Under Entry 50, the Parliament can only levy taxes on capital value of assets excluding taxes on immovable property. Under such circumstances, the federal government to levy a tax directly in contention is either a mistake, or a deliberately non-constitutional move. Both of which do not reflect well on the government.

The overseas people have a bittersweet relationship with their homeland. They often leave the country in the hopes to earn a good future. A future ripe with the hopes of relocating to their homeland, as soon as they have enough money. And when the time comes, they want to bring their wealth back to the country.

However, to bring back any asset that they have acquired overseas, they need to first register that asset and pay a CVT on it. Think of it as an overseas Pakistani. All your life, you have paid a tax on the asset in its home country (depending upon that country’s tax law). Now that you want to relocate to your homeland, the homeland is asking for a certain chunk of that asset, that could very well still be overseas, to allow you to be a legitimate citizen. And if you fail to do so, you become a tax evader and are worthy of penalty or jail time.

Tragic as it may sound, it is almost customary for countries to tax overseas assets of their citizens. Most of the countries do that. What most countries don’t, however, face is a crippling balance of payment crises.

There is another problem with overseas assets as per Pakistan’s own laws, and that problem is one of jurisdiction. While movable assets are only taxed once they are brought

back, immovable assets don’t fall under the purview of any province’s jurisdiction. Former Chairman FBR, Shabbar Zaidi, in one of his articles, states that, “Unless there is an amendment in the Constitution, the citizens of Pakistan cannot be taxed on the capital value of immovable properties outside Pakistan by the federal government in any manner whatsoever.”

On the other hand, even if the federal government claims jurisdiction over overseas assets, there is another alarming detail in the Finance Act 2022. In the section 8, subsection 3, part c (1), the Finance Act states that, “the value shall be – (i) the total cost of the foreign assets on the last day of the tax year, in relevant foreign currency converted into rupees as per exchange rates notified by State Bank of Pakistan for the said day.

Explaining this act, Haq said, “Imagine if you bought a property for 100 pounds, 10 years ago and the property’s value did not grow in the UK market. The value of that property in PKR terms still grows more than twice in PKR terms, considering the fall in exchange rate. The government is asking for a tax on the PKR value of that same property. You as an investor did not have anything to do with the exchange rate fall, why should you be paying the price?”

“When we look at this it seems as if it is neither CVT nor wealth tax, rather it looks as if the government is trying to tax the notional gains of people.” he added.

As if it was not complicated enough, the asset declaration laws of 2018 and 2019, or simply the amnesty on declaration of assets, awarded in 2018 and 2019, is exempt from any income or

capital taxes after the payment of the upfront principal. Ironically, when Imran Khan’s government gave this amnesty, they did so to increase the tax net of the country.

Whether those assets, under amnesty, are up for grabs in the Finance Act 2022, is still a debatable issue but the precedent suggests that if any pakistani had a time travelling machine, they would rather go back four years and pay an upfront tax rather than be saddled with a perpetual tax of a much higher value.

Those who held back on their declarations till 2018, get rewarded, whereas those who abided by the laws since the get go, get to pay the newest CVT.

There already is a hue and cry about the multitudes of problems that exist in the current version of this law. The Sindh High court resolved one of the cases regarding federal jurisdiction, in favour of the federal government, however the judgement still awaits appraisal from the Supreme Court.

It is also strange that no parliamentary debate was observed on this Finance Act 2022, otherwise legislators in the parliament themselves could have found discrepancies. And even if they didn’t, institutions and collectives almost always weigh in on such matters. But that chance was not given.

CVT is a legitimate form of taxation, and progressive economies encourage such public finance measures. However, carrying out steps such as these require a long-standing understanding of not only your fiscal needs but also the pressure points of your economy. To do that in Pakistan, the country would first have to be rid of vested interest.

The current CVT is riddled with complications, and there is no guarantee whether it will do the job that was required from it. Even in the context of real estate business, it is more predatory than progressive.

To have progressive taxation, the country needs efficient institutional machinery. Something that it does not currently have. The machinery that it does have, runs the risk of inefficiency even with a perfectly drafted tax. With the current law, the state becomes vulnerable to a lot more than just inefficiencies.

n

“Unless there is an amendment in the Constitution, the citizens of Pakistan cannot be taxed on the capital value of immovable properties outside Pakistan by the federal government in any manner whatsoever”

Shabbar Zaidi, Ex Chairman FBR

“When we look at this it seems as if it is neither CVT nor wealth tax, rather it looks as if the government is trying to tax the notional gains of people. It is shocking that they are being asked to pay something as extraneous as the exchange rate difference”

Dr Ikramul Haq, Adjunct Faculty LUMS, Advocate Supreme Court

Has the aftermath of the Aurat March this year been a little bit less vociferous in its hate? Or have we just got so used to being demonised that we’re not feeling the heat as much? Amongst the myriad conversations that took place at the marches but most especially in the days following them, one particular plaint has stood out.

It is the barrier that many women still face in Pakistan: Access to financial services. Pakistan is part of the seven-nation group that has more than 50% unbanked population. So there are no surprises there that women’s ownership of bank accounts lies abysmally low at 7%.

It is commonplace to have joint bank accounts with husbands as co-owners. According to a recent report discussed at the launch of Standard Chartered’s women-specific banking titled “SC Sahar Women’s Account,” in February, only 14 million bank accounts are owned by women, of which one in six are operated by

women, the rest are joint accounts with men. These stats tell a story. Women essentially do not have agency over their own money. In conversation with Profit, a young working woman who wishes not to be named, said that after she got married the couple decided to open a joint bank account for savings. But “Now I can’t even take out my money to spend on my parents’ needs and luxuries without giving him a justification. I don’t ask him where he spends his money but because he gets to know every time I take out money it becomes a matter of discussion,” she said.

“When I got my first job in 2021, I went to Bank Alfalah to open my bank account,” says Memoonah Asad, a young woman in her 20s. On the first day, no banking agent paid heed. Maybe I looked too young, or maybe it was just because I was a woman. I kept telling them that I’m running out of time so eventually, I left. The next day when I visited they kept asking me for a ‘valid’ source of income even though I did show them proof of my employment. On the third visit, I took my father along and once he showed them his proof of income

only then they started the process.”

Asad points out two major contentions: Relatability and documentation. In 2021, SBP noted that only 13% of the banking staff and 1% of the branchless banking staff are women. Therefore, like Asad, a lot of women feel intimidated to visit the bank as they fear they won’t be taken seriously. So they can never really be financially literate enough to understand which documents are needed.

In the last few years, the gender gap in financial services has widened significantly. This is mostly because the population is slowly becoming part of banking and financial services, but it comprises mostly men. “The majority of unbanked adults continue to be women even in economies that have successfully increased account ownership and have a small share of unbanked adults. In Türkiye, for example, about a quarter of adults are unbanked, and yet 71% of those unbanked adults are women. Brazil, China, Kenya, Russia, and Thailand also have relatively high rates

Women despite having their own bank accounts are not free to make their own financial decisions

of account ownership, compared with their developing economy peers, and yet a majority of those who are still unbanked are women. Things are not much different in economies in which less than half the population is banked. For example, in Egypt, Guinea, and Pakistan women make up more than half of the unbanked population,” says World Bank’s Findex Report, 2021.

Below is the breakdown of women’s participation in banking services in Pakistan

world, which impedes their access to money and even the right documentation. The following graph explains the reason behind women’s financial exclusion.

With such problems, women turn to other alternatives. According to Halima Iqbal, a former banker in Canada and co-founder of the online committee system Oraan, pooling in money for committees is a more acceptable form of financial services. “They are not just pooling in but are actively participating in vari-

family when there is a need so often times they are seen financially assisting extended family members as well. “My maternal uncles have shops so their income is not stable. To kickstart their businesses, I took a loan from the bank of Rs 500,000 and now I face a deduction of Rs 14,500 in my pay every month. Their business is not going too well, so I pay for their kids’ school fees too,” said Hina Abbas, a lady health care worker in Shikarpur.

Abbas’ story busts the traditional myth that women don’t need banking services. When women are involved in formal financial services, there is a trickle-down effect on the community.

Realising the utmost importance of women’s participation in the financial system, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) launched a targeted Banking of Equality policy in 2021. The policy comprises five pillars: improving gender diversity in the banking staff, women-centric products and services in all commercial banks, deploying women champions at all touchpoints to make the process easier and smoother for women, collecting of gender-disaggregated data to sharpen focus on financial inclusivity and reviewing existing and new policy frameworks for gender sensitivity.

compared to men:

Source: Data Darbar

A lot of it has to do with the cultural and social norms, and perceptions about women. For example, in Pakistan there’s a massive gender gap in mobile ownership. Pakistan falls behind even Afghanistan in this regard. The graph below shows these dismal numbers.:

Without mobiles phones there can be no access to digital banking, or even electronic banking because registration requires a phone number. Forget phones, some women don’t even have an ID card.

“The biggest hindrance is the cultural restriction. A lot of women who apply for loans don’t have the right documentation, they struggle with something as simple as a CNIC,” said a member of the senior management at a local bank. It’s not that they don’t get it. It’s the overly complicated system that pushes them away from it.

Having said that, numbers show that over the years women’s participation has doubled, reaching a double figure percentage of 13% from 3% in the last decade.

This shows that though the gender gap may have narrowed, women’s inclusion is still less than half when compared to their male counterparts. This is because they generally have little to no digital exposure to the outside

ous schemes to strategise their spending and loans. The success of committees is because the treasurer is a woman. A lot of women have expressed their concern that they trust a woman to handle their finances,” she said.

Household expenditure is often handed over to women. They devise how to pay bills, school fees, manage groceries and maybe even create savings. Cultural normative behaviour dictates they help everyone and anyone in the

The policy has thoroughly been applauded by the banking industry. But there are implementation measures which pose challenges, as many women have experienced. “Even now when you go to open a bank account, you will be asked to provide proof of income. It’s redundant for women who are housewives and don’t have official documentation of their money,” said Iqbal.

However, Abid Qamar, the spokesperson of SBP is hopeful. “It will take some time

to be fully implemented. We launched Asaan account to cater to this problem. You can register an account on the phone just by entering your NIC number. No extra documents are required,” he explained.

Meanwhile, problems abound. Often, women’s information is breached by the banks. “It is a common practice to call the husband for confirmation when a woman registers their accounts. It has happened to me and so many women I know. Even if the husband is not a customer of the same bank, the bank staff thinks it’s their responsibility to inform how and when their wives are spending money,” highlighted Iqbal. This is a major violation of privacy and is rooted from the general perception that women do not understand finances.

When questioned, officials from different banks requesting anonymity, denied any such happening. One senior member at a local bank in Karachi described it as “hogwash” saying that in her knowledge, nothing like this has ever been done. “Even if it had, we would have vehemently stopped such a practice from perpetuating.”

The SBP’s policy, specifically the part of deploying women champions directly, contests against the overarching belief about women and their access to financial institutions. Profit asked Qamar what to do if the banking staff is not taking a woman seriously, and making the process more confusing for them rather than walking them through it. He replied, “you complain about the bank to us. The State Bank can’t employ their own agents to check what’s happening in each bank. But we do have a

helpline and an email address on our website where we encourage everyone to launch their complaints if they are not following the protocol. This will help us review the performances and create better policies.’’

But what kind of woman does this policy really help? It seems like it would be very helpful for someone who is financially literate. But what about the woman who has little to no education? What is she supposed to do?

“Of course it does. Every bank is supposed to have women-centric products and services that are designed specifically for your needs. If you visit any bank near you, you will find many products such as HBL Nisa Savings Account, Allied Khanum Account, and MCB Ladies Account. You can find a plan according to your needs,” mentioned Qamar. “The purpose of these accounts along with women champions is to facilitate the banking journey according to different needs and problems,” he added.

However, Profit reached out to some women, who visit banks often and try to avail banking services, and asked if they knew of

such products in their banks. Almost every respondent said they had no idea such products existed. The very few who said they knew, expressed a very superficial understanding of what is available. “Yes, I saw a banner of Nisa Savings Account in HBL and something similar in UBL. But I never really inquired about it and no one from the bank told me either,” said Oroba Tasnim.

“Not inquiring is on her,” said the banker from Karachi, “but yes, these products need to be marketed in a way that makes them appealing enough for women to ask about them.”

Not many women know about the services that can be available to them and so are unable to derive any benefit from them. “We are encouraging commercial banks to market these products. It’s not a matter of two or three days. It will take some time. Banks’ performance is assessed based on their efforts to include more women so in a few years we can hope to see the real results,” said Qamar.

The central bank’s policy mandates every woman to have a bank account just with an ID document. But for those who don’t, SBP can’t do much about it. “It’s not under our mandate. It’s an issue that must be addressed by NADRA,” added Qamar.

The only thing that will stand the test of time then is for women to step out of their comfort zone, to visit these banks, to insist on knowing and understanding the products and services to them. But even then, this will help those who are literate and can therefore be pushed into making a change. For underprivileged women, access to financial services seems like a pipe dream. n

Imagine the thrill of cruising down the streets of your beloved cities, the wind in your hair, the unbridled freedom of the open road, and the heady scents of Karachi’s salty sea breeze, the misty mountains of Islamabad, or Lahore’s pungent potpourri of spices. For those belonging to the middle-class, car ownership is not only a symbol of triumphant success but also a testament to their hard work and tireless perseverance in the pursuit of a better life.

In a country where public transportation is fraught with inconvenience and unreliability, owning a car is not just a hard-earned luxury – it is a veritable necessity, a means to unfettered mobility, independence and convenience, and an emblem of personal progress as well as social mobility.

However, that once-cherished dream

is now disintegrating, crushed by soaring rates of inflation that have left many families reeling, struggling to keep their heads above water. Middle-class families, who have striven and struggled to attain the dream of car ownership, are now facing a dilemma: relinquish a reward for their rigorous labour or forgo other essentials, and risk plummeting into destitution.

The depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee, and the higher taxes imposed by the Pakistani government amidst skyrocketing inflation have brought many to a gut-wrenching realisation that the cherished ideal of car ownership, one that seemed within sight may now become a distant memory for many.

It is almost a guarantee at this point that one can expect car manufacturers to increase their prices with ever reducing intervals, sometimes within a fortnight even. And each revision leaves us aghast at the numbers.

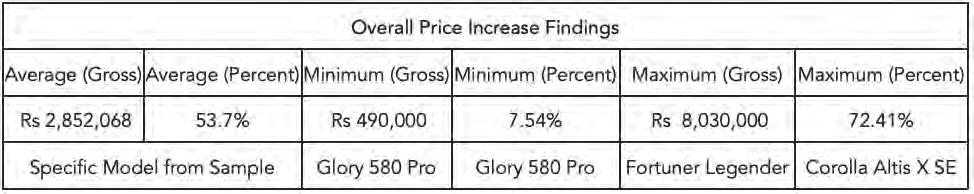

Looking at just the cars that saw their prices revised following the Federal Board of Revenue’s (FBR) increase in the GST, Profit found that customers fork out an additional Rs 2.8 million on average for their vehicle compared to what they would have just a year ago. On a year-on-year basis, car prices have risen by 53.83% on average from March of last year to March this year. The further back we go, the more depressing this statistic gets for prospective customers.

What’s the reason?

The rupee’s depreciation against the US Dollar is the quick answer Are we in crisis mode?

Of course. Will prices go down?

Unlikely.

Yes.

Let’s first start with how bad the prices are to begin with.

The constant flurry of price revision via company circulars has probably desensitised many prospective buyers from even pondering over whether they should purchase their vehicle of choice. However, it’s important to take a deep dive into how bad things are to get an idea of what we’re talking about.

But first, let’s explain how we did the maths here. Profit has only looked at the car prices that had been revised after the FBR’s decision to levy the 25% GST. The cars also had to be a year old in terms of their availability which means that they must have been available for customers to buy in March 2022. Furthermore, cars selected based on the aforementioned criteria were done so as of writing this article; March 15. The companies in question that were thus explored for the article were then Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Changan, BAIC, DFSK, KIA, and Peugeot. It is also worth mentioning that not every model across the aforementioned brand pool could be explored due to the limitations of the criteria

we outlined.

Upon examining the chosen brand portfolio, Toyota stands out with the highest average price increases, both in absolute and relative terms. On average, Toyota cars increased in price by Rs 3.795 million, or 62%. Moreover, the SUV segment had the largest gross increase in price, with a surge of Rs 5.1 million. Meanwhile, pickups had the largest relative price increase, at 59%, since March.

In terms of simply looking at cars you might have been interested in buying. DFSK’s Glory Pro 8 recorded the lowest absolute and relative price increases at Rs 490,000, and 7.54% respectively. In contrast, the Toyota Legender recorded the greatest gross increase whilst the Corolla Altis Special Edition recorded the greatest relative increase. The former saw an absolute increase of Rs 8 million, whilst the latter saw a relative increase of a whopping 72.41%.

“The greatest reason for the price increase is the rupee’s depreciation against the US dollar. Maqsood Ur Rehman Rehmani, Vice President and Company Secretary at

Honda Cars, tells Profit. Similarly, “The raw materials used in the manufacturing of an automobile constitute a major cost. This cost can be compared to that of a house where construction expenses form a significant part of the overall cost structure. When the rupee depreciates against the dollar, it results in an increase in the prices of parts across the supply chain.,” says Syed Shabbiruddin, Director Sales & Marketing at Master Changan Motors.

“If the rupee were to appreciate against the US dollar then there is a possibility for price reductions,” says Rehmani, however, there is a caveat to his statement which he explains in conversation to Profit. We’ll get to that later though.

The rupee has depreciated a whopping 57.83% from its value of Rs 179 on March 15, 2022, to Rs 283 on March 15, 2023, against the US dollar. The depreciation is also largely consistent with the average price increases seen across the industry following an increase in the GST. Profit found that across its entire sample, the average price increase sat at 53.7%. Are these prices, however, the norm? Most likely.

“I don’t think the rupee is going to appreciate in any material way,” says Fahad Rauf, Head of Research at Ismail Iqbal Securities. “There are a lot of challenges on the macro front and there does not seem to be an easy way out. The pressure would continue to mount on the rupee. It would be great if it could only stabilise around 275 and not depreciate beyond 300. So, in that sense, I don’t see car prices going down,” Rauf continues.

Economics dictates that prices tend to be downward sticky.This is where the caveat we mentioned comes into play. Now, Rehmani did agree to the fact that an appreciation of the rupee against the dollar - however likely it seems based on Rauf - would lead to a reduction in the prices

If we set our prices based on the expectation that the dollar will reach Rs 280 when our parts arrive and it doesn’t happen, we face the opportunity cost of our savings. We may choose to reduce car prices, advertise more, increase worker salaries, or save the money for a rainy day if we anticipate future cost increases suchSyed Shabbiruddin, Director Sales & Marketing at Master Changan Motors

It might take some time for demand and purchasing power like that to pick up, and incomes might not readjust to their previous levels for a while

Yousuf M.Farooq, Director of Research at Topline Securitiesat Ismail Iqbal Securities

of our favourite cars. The degree to the price reduction is, and whether it will be significant, is the next point of concern.

“The dollar is not the only factor. There are other factors too,” says Rehmani. “The cost of doing business has significantly increased now. Look at the state of general inflation. There has been a multiplier effect in terms of the costs we now incur due to the state of the economy,” Rehmani continues.

Shabbiruddin responded similarly when asked if a rally by the rupee could lead prices to be revised downward, stating “Although this is how things are supposed to work in theory, it’s not always the case due to various complexities. Companies typically set their prices based on their expected future costs. For instance, if we order parts in March and expect them to arrive by June, we may set our prices based on the anticipated costs of clearing the parts when they arrive at the port”.

“If we set our prices based on the expectation that the dollar will reach Rs 280 when our parts arrive and it doesn’t happen, we face the opportunity cost of our savings. We may choose to reduce car prices, advertise more, increase worker salaries, or save the money for a rainy day if we anticipate future cost increases such as electricity,” Shabbiruddin continued.

So what are the rising costs that these

companies have faced beyond the immediate cost to import their parts?

“The cost of materials has risen, the cost of utilities has risen, the cost of petrol has risen. The companies that transport the cars to and from the plant to the showrooms have increased their costs. Our vendors have increased their costs,” explains Rehmani.

Again, “Let’s consider a tier 3 vendor that produces rubber seals for a car’s shock absorbers. Typically, these vendors hire

individuals from lower income strata, so any increase in inflation rates may lead to higher salaries demanded by their workforce. The vendor’s increased labour costs will result in higher prices for the rubber seals sold to tier 2 vendors. Similarly, the tier 2 vendor may increase the price of the shock absorber, citing the increased cost of one of its key subcomponents. By the time the product reaches the car manufacturers, the cost of inputs has already gone up by several rounds,” explains Shabbiruddin

“Automotive companies typically do not have high profit margins compared to their peers in industries such as cement and sugar. The illusion of high profitability is often assumed by outsiders. Thus, when a company faces higher costs for a particular part, they may pass on that cost to consumers, which can reduce demand for cars. Reduced demand may lead to a tier 3 vendor reducing production levels, which in turn can result in higher per unit costs for the part. This cycle of spiralling costs can perpetuate itself over time,” Shabbiruddin continues to explain.

For whatever its worth, companies are likely to extract every last rupee they can to cover their own costs as best as they can. Not just because they’re suffering from spiralling costs but there are also theoretical caps on

There are a lot of challenges on the macro front and there does not seem to be an easy way out. The pressure would continue to mount on the rupee. It would be great if it could only stabilise around 275 and not depreciate beyond 300. So, in that sense, I don’t see car prices going down

Fahad Rauf, Head of Research

I’m not sure that is true. I think there is a lull period instead. Till incomes eventually rise 3x, which I’d hope to see in the next couple of years. Maybe a bit longer this time

Dr Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor and the Head of the Economics Department at LUMS

how many cars they can make too now. What do we mean now?

Well, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) enforced its own version of India’s Licence Raj when it enacted administrative controls to stem the outflow of foreign exchange from the country. Profit has covered this previously.

Read more: The SBP is controlling car imports

The tl;dr edition of what is relevant for us is that car companies could only import a very certain amount of parts. The consequence of that decision unfolded across the latter half of 2022 when car companies began to hike their prices as a consequence, in order to maximise their per units profitability.

The administrative controls came to an end on December 27 with the SPB’s EPD Circular Letter No. 20 of 2022. The circular put an end to the administrative controls, however, in name only. The circular instructed banks to follow a hierarchy in terms of necessity for approving imports. Munir Bana, Chairman of the Pakistan Association of Auto Parts & Accessories Manufacturers, told Profit that “The auto industry is not an essential item and therefore our imports will continue to be controlled and rationed by SBP,” when the circular was first issued. Bana’s words have been on the mark with the sheer number of non-production days across the industry, with each non-production day notification blaming the decision solely on the SBP’s circular.

The circular does highlight how companies who can obtain deferred payments for 365 days should be given preference by local banks. Firstly, what do deferred payments in this context even mean? “We have been told to procure our imports, and make the payment for them after 365 days. The letters of credits that will be issued will be usance letters of credits, for which payments will be made at a

later date,” Rehmani explains.

Now this has had its own problems. Rehamni states that this decision has led to a lot of problems with suppliers. “When you make the payment after 365 days, how will you know the rate of the rupee to the dollar will be then? The rupee’s current volatility has made this near impossible. Itni lambi forecasting kon kar sakta hai?” says Rehmani. For those companies that fare better than Rehmani in negotiating with their suppliers, the most likely step is to maximise their profits even more so due to the fear of a worst case scenario for the payment they have to make next year.

“There is a restriction on completely knocked-down imports. So companies will try to compensate to some extent by keeping prices high, even if the cost of certain components comes down,” adds Rauf.

So, where are we then? Let’s recap. The rupee looks unlikely to appreciate against the dollar. On the assumption that it does, it’s likely that companies have now priced in the general level of inflation and a possible worst case scenario for the payments they have to

The cost of doing business has significantly increased now. Look at the state of general inflation.There has been a multiplier effect in terms of the costs we now incur due to the state of the economy

Maqsood Ur Rehman Rehmani, Vice President and Company Secretary at Honda Cars

The auto industry is not an essential item and therefore our imports will continue to be controlled and rationed by SBP

Munir Bana, Chairman of the Pakistan Association of Auto Parts & Accessories Manufacturers

make to their suppliers in a year’s time. In the absence of hope that car prices are going to come down, should we all forsake our dream to own a car? Maybe, at least for a bit longer.