19 minute read

Mera bank, meri marzi

By Momina Ashraf

Has the aftermath of the Aurat March this year been a little bit less vociferous in its hate? Or have we just got so used to being demonised that we’re not feeling the heat as much? Amongst the myriad conversations that took place at the marches but most especially in the days following them, one particular plaint has stood out.

Advertisement

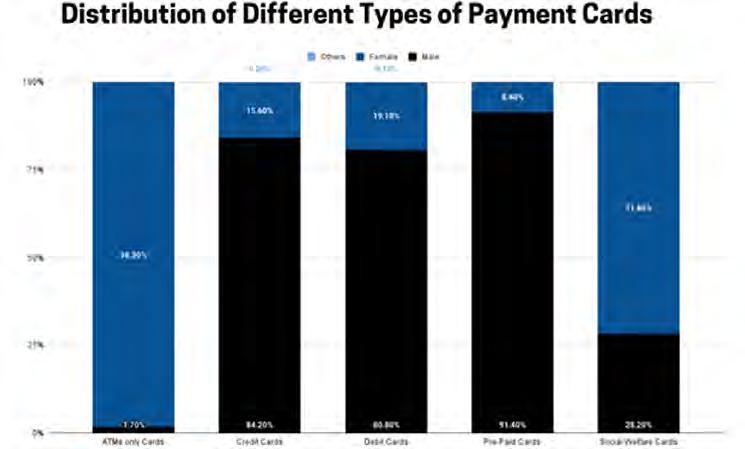

It is the barrier that many women still face in Pakistan: Access to financial services. Pakistan is part of the seven-nation group that has more than 50% unbanked population. So there are no surprises there that women’s ownership of bank accounts lies abysmally low at 7%.

It is commonplace to have joint bank accounts with husbands as co-owners. According to a recent report discussed at the launch of Standard Chartered’s women-specific banking titled “SC Sahar Women’s Account,” in February, only 14 million bank accounts are owned by women, of which one in six are operated by women, the rest are joint accounts with men. These stats tell a story. Women essentially do not have agency over their own money. In conversation with Profit, a young working woman who wishes not to be named, said that after she got married the couple decided to open a joint bank account for savings. But “Now I can’t even take out my money to spend on my parents’ needs and luxuries without giving him a justification. I don’t ask him where he spends his money but because he gets to know every time I take out money it becomes a matter of discussion,” she said.

“When I got my first job in 2021, I went to Bank Alfalah to open my bank account,” says Memoonah Asad, a young woman in her 20s. On the first day, no banking agent paid heed. Maybe I looked too young, or maybe it was just because I was a woman. I kept telling them that I’m running out of time so eventually, I left. The next day when I visited they kept asking me for a ‘valid’ source of income even though I did show them proof of my employment. On the third visit, I took my father along and once he showed them his proof of income only then they started the process.”

Asad points out two major contentions: Relatability and documentation. In 2021, SBP noted that only 13% of the banking staff and 1% of the branchless banking staff are women. Therefore, like Asad, a lot of women feel intimidated to visit the bank as they fear they won’t be taken seriously. So they can never really be financially literate enough to understand which documents are needed.

Unbanked women

In the last few years, the gender gap in financial services has widened significantly. This is mostly because the population is slowly becoming part of banking and financial services, but it comprises mostly men. “The majority of unbanked adults continue to be women even in economies that have successfully increased account ownership and have a small share of unbanked adults. In Türkiye, for example, about a quarter of adults are unbanked, and yet 71% of those unbanked adults are women. Brazil, China, Kenya, Russia, and Thailand also have relatively high rates of account ownership, compared with their developing economy peers, and yet a majority of those who are still unbanked are women. Things are not much different in economies in which less than half the population is banked. For example, in Egypt, Guinea, and Pakistan women make up more than half of the unbanked population,” says World Bank’s Findex Report, 2021.

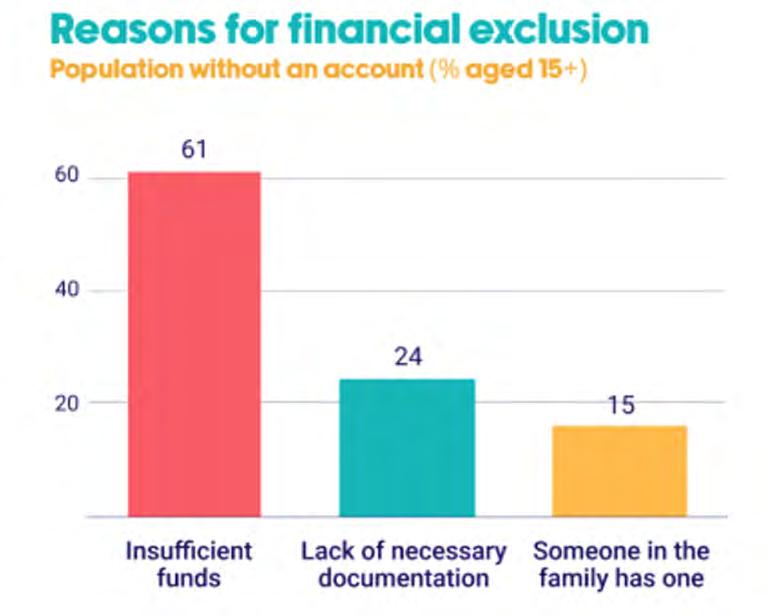

Below is the breakdown of women’s participation in banking services in Pakistan world, which impedes their access to money and even the right documentation. The following graph explains the reason behind women’s financial exclusion.

With such problems, women turn to other alternatives. According to Halima Iqbal, a former banker in Canada and co-founder of the online committee system Oraan, pooling in money for committees is a more acceptable form of financial services. “They are not just pooling in but are actively participating in vari- family when there is a need so often times they are seen financially assisting extended family members as well. “My maternal uncles have shops so their income is not stable. To kickstart their businesses, I took a loan from the bank of Rs 500,000 and now I face a deduction of Rs 14,500 in my pay every month. Their business is not going too well, so I pay for their kids’ school fees too,” said Hina Abbas, a lady health care worker in Shikarpur.

Abbas’ story busts the traditional myth that women don’t need banking services. When women are involved in formal financial services, there is a trickle-down effect on the community.

How efficient are SBP’s policies?

Realising the utmost importance of women’s participation in the financial system, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) launched a targeted Banking of Equality policy in 2021. The policy comprises five pillars: improving gender diversity in the banking staff, women-centric products and services in all commercial banks, deploying women champions at all touchpoints to make the process easier and smoother for women, collecting of gender-disaggregated data to sharpen focus on financial inclusivity and reviewing existing and new policy frameworks for gender sensitivity.

compared to men:

Source: Data Darbar

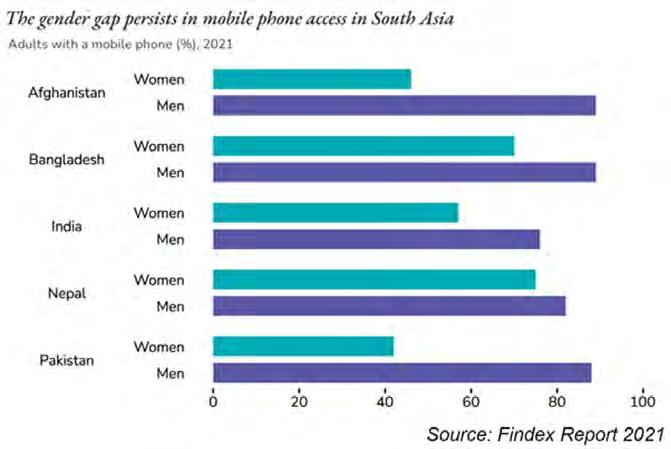

A lot of it has to do with the cultural and social norms, and perceptions about women. For example, in Pakistan there’s a massive gender gap in mobile ownership. Pakistan falls behind even Afghanistan in this regard. The graph below shows these dismal numbers.:

Without mobiles phones there can be no access to digital banking, or even electronic banking because registration requires a phone number. Forget phones, some women don’t even have an ID card.

“The biggest hindrance is the cultural restriction. A lot of women who apply for loans don’t have the right documentation, they struggle with something as simple as a CNIC,” said a member of the senior management at a local bank. It’s not that they don’t get it. It’s the overly complicated system that pushes them away from it.

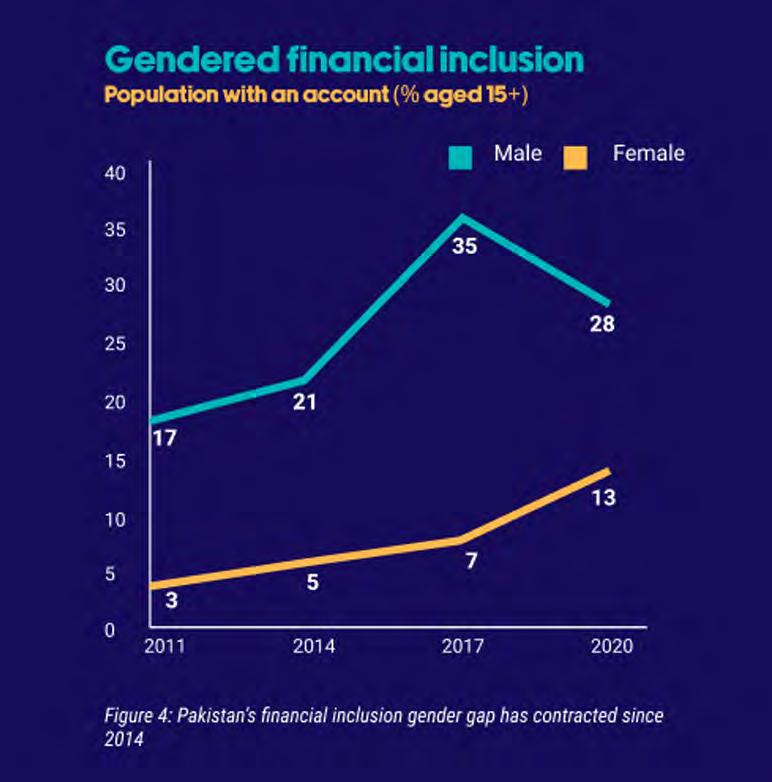

Having said that, numbers show that over the years women’s participation has doubled, reaching a double figure percentage of 13% from 3% in the last decade.

This shows that though the gender gap may have narrowed, women’s inclusion is still less than half when compared to their male counterparts. This is because they generally have little to no digital exposure to the outside ous schemes to strategise their spending and loans. The success of committees is because the treasurer is a woman. A lot of women have expressed their concern that they trust a woman to handle their finances,” she said.

Household expenditure is often handed over to women. They devise how to pay bills, school fees, manage groceries and maybe even create savings. Cultural normative behaviour dictates they help everyone and anyone in the

The policy has thoroughly been applauded by the banking industry. But there are implementation measures which pose challenges, as many women have experienced. “Even now when you go to open a bank account, you will be asked to provide proof of income. It’s redundant for women who are housewives and don’t have official documentation of their money,” said Iqbal.

However, Abid Qamar, the spokesperson of SBP is hopeful. “It will take some time to be fully implemented. We launched Asaan account to cater to this problem. You can register an account on the phone just by entering your NIC number. No extra documents are required,” he explained.

Meanwhile, problems abound. Often, women’s information is breached by the banks. “It is a common practice to call the husband for confirmation when a woman registers their accounts. It has happened to me and so many women I know. Even if the husband is not a customer of the same bank, the bank staff thinks it’s their responsibility to inform how and when their wives are spending money,” highlighted Iqbal. This is a major violation of privacy and is rooted from the general perception that women do not understand finances.

When questioned, officials from different banks requesting anonymity, denied any such happening. One senior member at a local bank in Karachi described it as “hogwash” saying that in her knowledge, nothing like this has ever been done. “Even if it had, we would have vehemently stopped such a practice from perpetuating.”

The SBP’s policy, specifically the part of deploying women champions directly, contests against the overarching belief about women and their access to financial institutions. Profit asked Qamar what to do if the banking staff is not taking a woman seriously, and making the process more confusing for them rather than walking them through it. He replied, “you complain about the bank to us. The State Bank can’t employ their own agents to check what’s happening in each bank. But we do have a helpline and an email address on our website where we encourage everyone to launch their complaints if they are not following the protocol. This will help us review the performances and create better policies.’’

But what kind of woman does this policy really help? It seems like it would be very helpful for someone who is financially literate. But what about the woman who has little to no education? What is she supposed to do?

“Of course it does. Every bank is supposed to have women-centric products and services that are designed specifically for your needs. If you visit any bank near you, you will find many products such as HBL Nisa Savings Account, Allied Khanum Account, and MCB Ladies Account. You can find a plan according to your needs,” mentioned Qamar. “The purpose of these accounts along with women champions is to facilitate the banking journey according to different needs and problems,” he added.

However, Profit reached out to some women, who visit banks often and try to avail banking services, and asked if they knew of such products in their banks. Almost every respondent said they had no idea such products existed. The very few who said they knew, expressed a very superficial understanding of what is available. “Yes, I saw a banner of Nisa Savings Account in HBL and something similar in UBL. But I never really inquired about it and no one from the bank told me either,” said Oroba Tasnim.

“Not inquiring is on her,” said the banker from Karachi, “but yes, these products need to be marketed in a way that makes them appealing enough for women to ask about them.”

Not many women know about the services that can be available to them and so are unable to derive any benefit from them. “We are encouraging commercial banks to market these products. It’s not a matter of two or three days. It will take some time. Banks’ performance is assessed based on their efforts to include more women so in a few years we can hope to see the real results,” said Qamar.

The central bank’s policy mandates every woman to have a bank account just with an ID document. But for those who don’t, SBP can’t do much about it. “It’s not under our mandate. It’s an issue that must be addressed by NADRA,” added Qamar.

The only thing that will stand the test of time then is for women to step out of their comfort zone, to visit these banks, to insist on knowing and understanding the products and services to them. But even then, this will help those who are literate and can therefore be pushed into making a change. For underprivileged women, access to financial services seems like a pipe dream. n

By Daniyal Ahmad

Imagine the thrill of cruising down the streets of your beloved cities, the wind in your hair, the unbridled freedom of the open road, and the heady scents of Karachi’s salty sea breeze, the misty mountains of Islamabad, or Lahore’s pungent potpourri of spices. For those belonging to the middle-class, car ownership is not only a symbol of triumphant success but also a testament to their hard work and tireless perseverance in the pursuit of a better life.

In a country where public transportation is fraught with inconvenience and unreliability, owning a car is not just a hard-earned luxury – it is a veritable necessity, a means to unfettered mobility, independence and convenience, and an emblem of personal progress as well as social mobility.

However, that once-cherished dream is now disintegrating, crushed by soaring rates of inflation that have left many families reeling, struggling to keep their heads above water. Middle-class families, who have striven and struggled to attain the dream of car ownership, are now facing a dilemma: relinquish a reward for their rigorous labour or forgo other essentials, and risk plummeting into destitution.

The depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee, and the higher taxes imposed by the Pakistani government amidst skyrocketing inflation have brought many to a gut-wrenching realisation that the cherished ideal of car ownership, one that seemed within sight may now become a distant memory for many.

It is almost a guarantee at this point that one can expect car manufacturers to increase their prices with ever reducing intervals, sometimes within a fortnight even. And each revision leaves us aghast at the numbers.

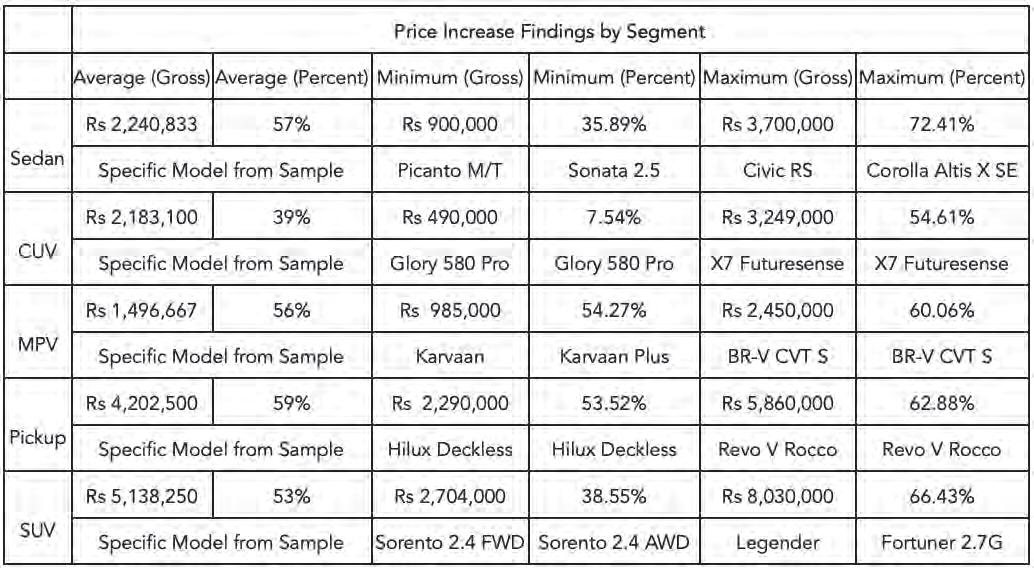

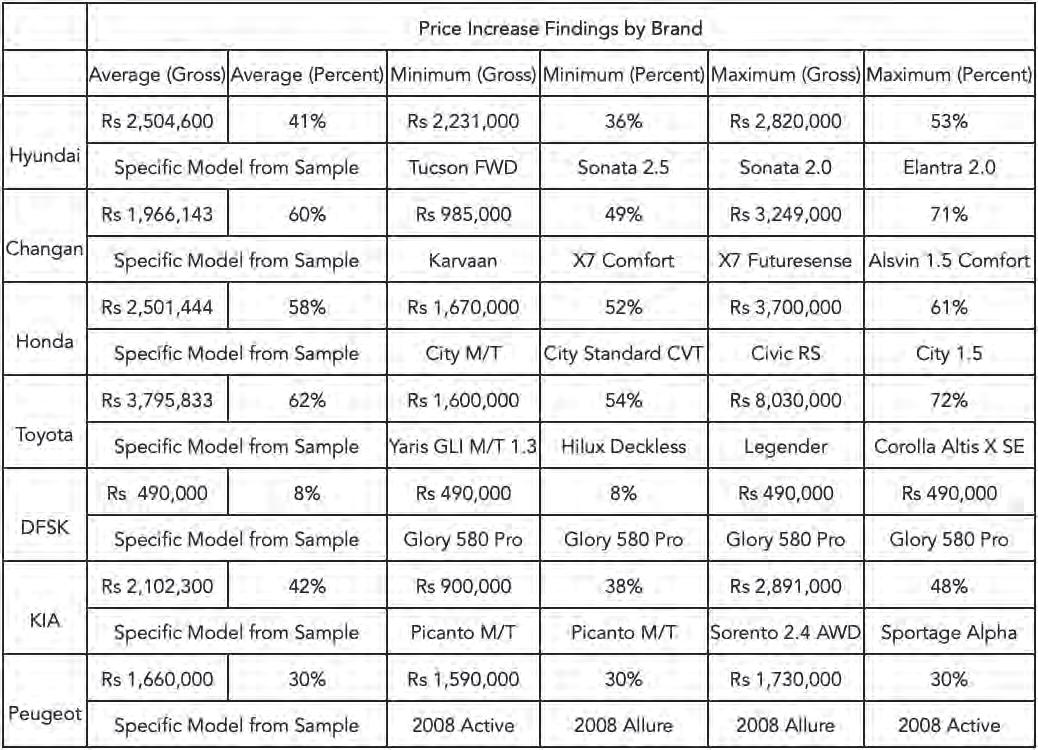

Looking at just the cars that saw their prices revised following the Federal Board of Revenue’s (FBR) increase in the GST, Profit found that customers fork out an additional Rs 2.8 million on average for their vehicle compared to what they would have just a year ago. On a year-on-year basis, car prices have risen by 53.83% on average from March of last year to March this year. The further back we go, the more depressing this statistic gets for prospective customers.

What’s the reason?

The rupee’s depreciation against the US Dollar is the quick answer Are we in crisis mode?

Of course. Will prices go down?

Unlikely.

Is there hope?

Yes.

Let’s first start with how bad the prices are to begin with.

Staring into the abyss

The constant flurry of price revision via company circulars has probably desensitised many prospective buyers from even pondering over whether they should purchase their vehicle of choice. However, it’s important to take a deep dive into how bad things are to get an idea of what we’re talking about.

But first, let’s explain how we did the maths here. Profit has only looked at the car prices that had been revised after the FBR’s decision to levy the 25% GST. The cars also had to be a year old in terms of their availability which means that they must have been available for customers to buy in March 2022. Furthermore, cars selected based on the aforementioned criteria were done so as of writing this article; March 15. The companies in question that were thus explored for the article were then Toyota, Honda, Hyundai, Changan, BAIC, DFSK, KIA, and Peugeot. It is also worth mentioning that not every model across the aforementioned brand pool could be explored due to the limitations of the criteria

As Electricity

we outlined.

Upon examining the chosen brand portfolio, Toyota stands out with the highest average price increases, both in absolute and relative terms. On average, Toyota cars increased in price by Rs 3.795 million, or 62%. Moreover, the SUV segment had the largest gross increase in price, with a surge of Rs 5.1 million. Meanwhile, pickups had the largest relative price increase, at 59%, since March.

In terms of simply looking at cars you might have been interested in buying. DFSK’s Glory Pro 8 recorded the lowest absolute and relative price increases at Rs 490,000, and 7.54% respectively. In contrast, the Toyota Legender recorded the greatest gross increase whilst the Corolla Altis Special Edition recorded the greatest relative increase. The former saw an absolute increase of Rs 8 million, whilst the latter saw a relative increase of a whopping 72.41%.

How did we get here? And what is the way out?

“The greatest reason for the price increase is the rupee’s depreciation against the US dollar. Maqsood Ur Rehman Rehmani, Vice President and Company Secretary at

Honda Cars, tells Profit. Similarly, “The raw materials used in the manufacturing of an automobile constitute a major cost. This cost can be compared to that of a house where construction expenses form a significant part of the overall cost structure. When the rupee depreciates against the dollar, it results in an increase in the prices of parts across the supply chain.,” says Syed Shabbiruddin, Director Sales & Marketing at Master Changan Motors.

“If the rupee were to appreciate against the US dollar then there is a possibility for price reductions,” says Rehmani, however, there is a caveat to his statement which he explains in conversation to Profit. We’ll get to that later though.

The rupee has depreciated a whopping 57.83% from its value of Rs 179 on March 15, 2022, to Rs 283 on March 15, 2023, against the US dollar. The depreciation is also largely consistent with the average price increases seen across the industry following an increase in the GST. Profit found that across its entire sample, the average price increase sat at 53.7%. Are these prices, however, the norm? Most likely.

“I don’t think the rupee is going to appreciate in any material way,” says Fahad Rauf, Head of Research at Ismail Iqbal Securities. “There are a lot of challenges on the macro front and there does not seem to be an easy way out. The pressure would continue to mount on the rupee. It would be great if it could only stabilise around 275 and not depreciate beyond 300. So, in that sense, I don’t see car prices going down,” Rauf continues.

What if the Rupee did appreciate in value?

Economics dictates that prices tend to be downward sticky.This is where the caveat we mentioned comes into play. Now, Rehmani did agree to the fact that an appreciation of the rupee against the dollar - however likely it seems based on Rauf - would lead to a reduction in the prices

at Ismail Iqbal Securities

of our favourite cars. The degree to the price reduction is, and whether it will be significant, is the next point of concern.

“The dollar is not the only factor. There are other factors too,” says Rehmani. “The cost of doing business has significantly increased now. Look at the state of general inflation. There has been a multiplier effect in terms of the costs we now incur due to the state of the economy,” Rehmani continues.

Shabbiruddin responded similarly when asked if a rally by the rupee could lead prices to be revised downward, stating “Although this is how things are supposed to work in theory, it’s not always the case due to various complexities. Companies typically set their prices based on their expected future costs. For instance, if we order parts in March and expect them to arrive by June, we may set our prices based on the anticipated costs of clearing the parts when they arrive at the port”.

“If we set our prices based on the expectation that the dollar will reach Rs 280 when our parts arrive and it doesn’t happen, we face the opportunity cost of our savings. We may choose to reduce car prices, advertise more, increase worker salaries, or save the money for a rainy day if we anticipate future cost increases such as electricity,” Shabbiruddin continued.

So what are the rising costs that these companies have faced beyond the immediate cost to import their parts?

“The cost of materials has risen, the cost of utilities has risen, the cost of petrol has risen. The companies that transport the cars to and from the plant to the showrooms have increased their costs. Our vendors have increased their costs,” explains Rehmani.

Again, “Let’s consider a tier 3 vendor that produces rubber seals for a car’s shock absorbers. Typically, these vendors hire individuals from lower income strata, so any increase in inflation rates may lead to higher salaries demanded by their workforce. The vendor’s increased labour costs will result in higher prices for the rubber seals sold to tier 2 vendors. Similarly, the tier 2 vendor may increase the price of the shock absorber, citing the increased cost of one of its key subcomponents. By the time the product reaches the car manufacturers, the cost of inputs has already gone up by several rounds,” explains Shabbiruddin

“Automotive companies typically do not have high profit margins compared to their peers in industries such as cement and sugar. The illusion of high profitability is often assumed by outsiders. Thus, when a company faces higher costs for a particular part, they may pass on that cost to consumers, which can reduce demand for cars. Reduced demand may lead to a tier 3 vendor reducing production levels, which in turn can result in higher per unit costs for the part. This cycle of spiralling costs can perpetuate itself over time,” Shabbiruddin continues to explain.

For whatever its worth, companies are likely to extract every last rupee they can to cover their own costs as best as they can. Not just because they’re suffering from spiralling costs but there are also theoretical caps on how many cars they can make too now. What do we mean now?

Well, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) enforced its own version of India’s Licence Raj when it enacted administrative controls to stem the outflow of foreign exchange from the country. Profit has covered this previously.

Read more: The SBP is controlling car imports

The tl;dr edition of what is relevant for us is that car companies could only import a very certain amount of parts. The consequence of that decision unfolded across the latter half of 2022 when car companies began to hike their prices as a consequence, in order to maximise their per units profitability.

The administrative controls came to an end on December 27 with the SPB’s EPD Circular Letter No. 20 of 2022. The circular put an end to the administrative controls, however, in name only. The circular instructed banks to follow a hierarchy in terms of necessity for approving imports. Munir Bana, Chairman of the Pakistan Association of Auto Parts & Accessories Manufacturers, told Profit that “The auto industry is not an essential item and therefore our imports will continue to be controlled and rationed by SBP,” when the circular was first issued. Bana’s words have been on the mark with the sheer number of non-production days across the industry, with each non-production day notification blaming the decision solely on the SBP’s circular.

The circular does highlight how companies who can obtain deferred payments for 365 days should be given preference by local banks. Firstly, what do deferred payments in this context even mean? “We have been told to procure our imports, and make the payment for them after 365 days. The letters of credits that will be issued will be usance letters of credits, for which payments will be made at a later date,” Rehmani explains.

Now this has had its own problems. Rehamni states that this decision has led to a lot of problems with suppliers. “When you make the payment after 365 days, how will you know the rate of the rupee to the dollar will be then? The rupee’s current volatility has made this near impossible. Itni lambi forecasting kon kar sakta hai?” says Rehmani. For those companies that fare better than Rehmani in negotiating with their suppliers, the most likely step is to maximise their profits even more so due to the fear of a worst case scenario for the payment they have to make next year.

“There is a restriction on completely knocked-down imports. So companies will try to compensate to some extent by keeping prices high, even if the cost of certain components comes down,” adds Rauf.

So, where are we then? Let’s recap. The rupee looks unlikely to appreciate against the dollar. On the assumption that it does, it’s likely that companies have now priced in the general level of inflation and a possible worst case scenario for the payments they have to make to their suppliers in a year’s time. In the absence of hope that car prices are going to come down, should we all forsake our dream to own a car? Maybe, at least for a bit longer.

Bracing the storm

Given the aforementioned complications associated with prices being revised downwards, is the middle-class dream of owning a car in tatters because of the state unaffordability then? “I’m not sure that is true. I think there is a lull period instead,” says Dr Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor and the Head of the Economics Department at LUMS. “Till incomes eventually rise 3x, which I’d hope to see in the next couple of years. Maybe a bit longer this time. Hard to assess,” Hasanain muses.

“This crisis of affordability is very shortterm, and is being faced by a very limited number of people. This is not being experienced in the villages. As soon as a crop is harvested, things improve in the villages - relatively,” says Yousuf M.Farooq, Director of Research at Topline Securities.

“You need to be mindful of one thing, 40-45% of Pakistan’s population is employed in the agricultural sector. The agricultural sector is protected from devaluation, and thus

40-45% of the population is insulated as well,” explains Farooq. “As soon as the wheat or sugar is harvested in Sindh, you will see that even the dollar has appreciated, the support price of sugar will have immediately risen. It will be harvested for Rs 360-370 which was not the rate last year because the support price was lower. The same applies to wheat. If you notice, then the Corolla picks up in sales after every crop cycle regardless of what is happening in the cities,” explains Farooq. Where does that leave people who live in the cities? Well. not in the best of spots, “The incomes that are affected because of devaluation are the ones in the cities, and those too for individuals that are on fixed salaries,” Farooq explains. Have people in the cities been given the short end of the stick then? Based on Farooq’s statements, yes. However, there is hope even for them. “Incomes for those on fixed salaries in the cities tend to readjust within a span of six-to-eight months to a year. Things recover. If devaluation happens, and someone receives a certain salary then it’s likely they’ll receive the same salary for the next six months. However, things will improve after a year,” Farooq explains. Despite Farooq’s statements, he does not paint a complete rosy picture of things to come.

“It might take some time for demand and purchasing power like that to pick up, and incomes might not readjust to their previous levels for a while,” says Farooq. “We probably need to run a current account for the next 10 years now to cover for the antics we’ve been pulling for the last 20 years,”. Despite Farooq’s warnings, there can be no talk of the current account without mentioning Pakistan’s historical proclivities. And that is where middle class car buyers might find their last hope to once again buy cars.

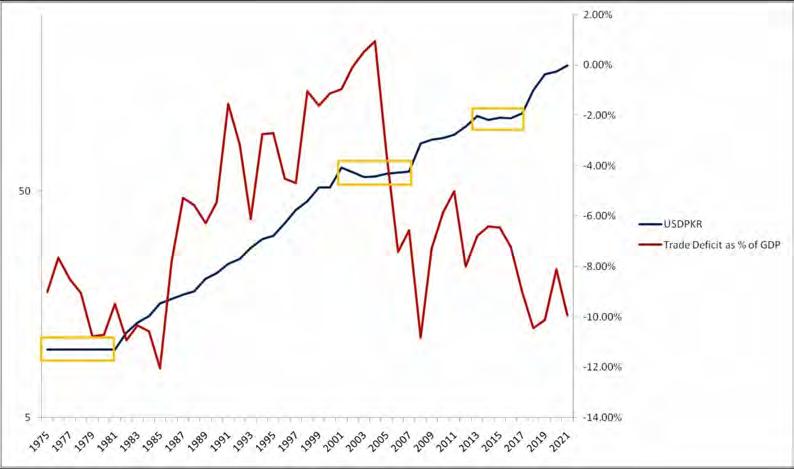

One man’s folly is another man’s new Civic

Looking at Pakistan’s historical economic track record, to say we have an addiction with an overvalued rupee is an understatement. Pakistan has had three notable periods of an overvalued currency; the 1960s to 1982, 2002 to 2007, and 2013 to 2017. These time periods are key. Why? “The earliest Daronomics was before the car industry anyway,” says Hasanain. The automotive industry may not be the reason for Pakistan’s addiction to an overvalued rupee, but it is most definitely a beneficiary of it.

A return to ways of old might just rekindle the hope that most of us have for being able to buy their favourite. However, one would assume this to be something of the past, right? That Pakistan has learnt from the recent bout of economic plight to not relapse? No. Pakistan has most recently returned to its old ways as recently as last month. Profit has written on the most recent episode of an overvalued currency for those interested.

Read more: Dollar Cap, IMF, Ishaq Dar and ECAP; A week of showdowns at the exchange market

What’s relevant is that if we did not learn amidst a collapsing economy, it’s likely that we have not learnt at all. Now is this something to look forward to? It depends. Are you looking to buy a car, or are you the one managing the crisis? n