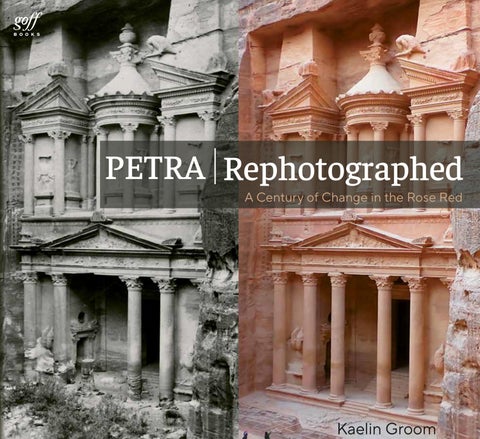

11 F OR ew OR d

15 Int RO d UC t IO n

17 t w O S C h O la RS a Cent UR y a pa R t

26 Ove R v I ew OF the R OS e Red C I ty

33 The Grand Entrance: Al-Khazneh and the Greater Siq Region

57 Eastern Highlands: Royal Tombs, Nasara Ridge, and Jabal Khubtha

81 Center of It All: Qasr al-Bint, al-Habis, and Wadi Turkmaniya

101 Top of the World: Deir Plateau and the Northwest Ridges

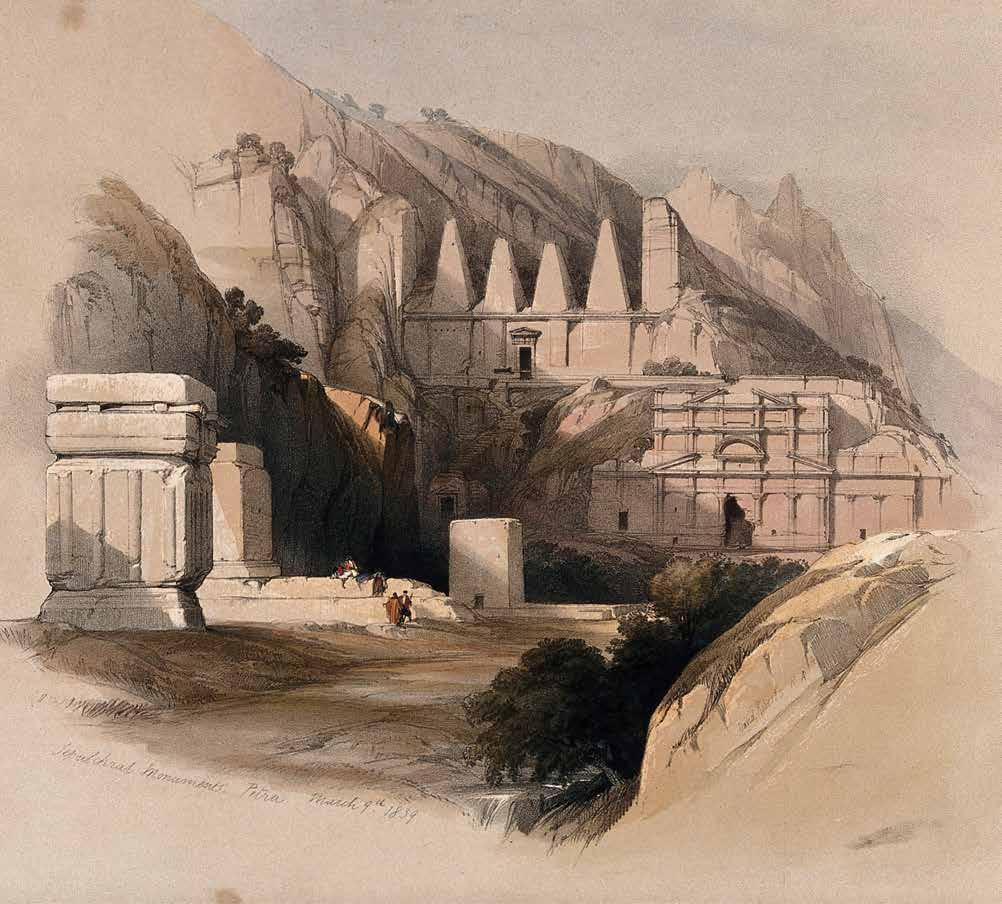

121 Trail to the Heavens: Wadi Farasa, Obelisk Ridge, and the High Place of Sacrifice

141 Outer Fringes: Jabal Harun, Bayda, Wadi Mousa, and the Southern Tombs

160 p et R a’ S e nd URI n G l e G a C y

Through photography, we create images of our world and reality just as we do with language. Whether moving or still, the images we create open a window into the world despite the difference between the object as it appears, the image, and the world. After the author, Dr. Kaelin Groom, asked me to write a foreword for this book, I was captivated by the images within for far longer than I expected. The book displays dozens of photographs that expand our understanding of the artistic creativity of the Nabataean architectural style. In addition to the author’s deep passion, the book’s success, in my view, can be ascribed to the masterful use of the techniques of modern digital photography, which lie behind much of the transformation of our cultural experiences and artistic expression. Photography has earned its place as fine art, helping us deepen our understanding of reality. The images in this volume, through the creative use of light, shadow, angle, and tasteful composition, testify to this transformative power.

Dr. Groom masterfully overcame the technical limitations of the camera that distort the relationship between image and reality, portraying Petra’s beauty with bravura. With her images, she raises questions about the nature of reality and subjectivity that go beyond perception, revealing to us the wonder of viewing these Nabataean monuments with the naked eye. Dr. Groom has presented this wonder to anyone interested in Petra, whether tourists, amateurs, researchers or otherwise. This book is a reference that enables us to compare photographs taken of Petra almost a hundred years ago with those of today, where we can see the extent of the damage Petra has suffered over the course of a century and the ability of this city to withstand the challenges posed by nature and human activity. The book does not only take us on a journey through images but also presents us with a fun, attractive, and enticing place for people to visit, confidently conveying the magnificence and strength of the city hidden behind the rose-red mountains.

proud of his procurement of a brand-new travel camera: the 1923 Dallmeyer “Speed” Camera. The slightly less-bulky camera captured negatives on 4.5 × 6 cm glass plates that had to be transported back to London with him to be developed—an admittedly risky situation since it would have been rare for all plates to arrive unbroken or cracked. I didn’t share that same risk, although one time I did temporarily misplace one of my memory cards (not a fun evening). My camera setup included a tripod-mounted Olympus Tough TG6 that, when paired via Bluetooth with a Samsung Galaxy S7 tablet, allowed me to check the accuracy of my new images by digitally overlaying them on Sir Kennedy’s original photographs while still vin the field.

I made every effort to repeat Sir Kennedy’s photographed scenes as precisely as possible. Identifying the photographed landmarks and their locations was only the first step. The more tedious task was determining the exact vantage point to correctly align all elements in the foreground, midground, and background of the historic images. This included capturing images, field checking their accuracy, and adjusting the camera position accordingly—a process repeated as many times as necessary to best match the height, angle, and location of the historic photograph. I was determined to perfectly match each image with its historic counterpart, even if that meant I needed to scale a steep hillside or My camera set up:

crawl under a bush that wasn’t present when Sir Kennedy took his photograph a century earlier.

One image required me to dig a small trench in a riverbed that had been buried since Sir Kennedy’s visit and lie flat on the ground to capture the image, much to my field assistant’s amusement.

It was also imperative that I duplicated Sir Kennedy’s approximate time of day so that the harsh desert sunlight and distinctive shadows were comparatively displayed in both images. This required a good deal of trial and error, planning, and unrelenting patience. Through the seasons, it quickly became apparent that

I also needed to give additional attention to determining—and matching—the estimated time of year in which the original photographs were taken, to account for the north-south seasonal migration of the sun’s path, which influences the angle of shadows cast on Petra’s steep cliffs and detailed façades.

Ultimately, repeat photography provides a powerful visual tool for understanding and communicating the ever-changing visual nature of the Rose Red City and beyond. It helps bridge the gap between past and present, offering insights into the complexities of environmental, cultural, and geological changes over time. By capturing images at different points in time, researchers can gain insights into the rate and extent of changes. This technique of repeated

Easily the most famous views of Petra, this region introduces readers to the enigmatic Djinn Blocks guarding Petra’s entrance, the twists and turns of the imposing Siq slot canyon, and the awe-inspiring emergence of the iconic Khazneh (the Treasury) monument which opens the way to the vast city beyond.

“That most perfect of the monuments, Khasna Faraoun, whose sculpted columns and cornices are pure lines of a crystalline beauty without blemish, where upon the golden sun looks from above, and Nature has painted that sand ruck ruddy with iron rust.” — m r. Charles m on tagu d o ughty 5

“Within the Siq itself, in a cross opening near its western end, stands the Khazna Fir’un, which from its picturesque and unexpected appearance in the ravine, as well as from its striking form, has become the best known and most discussed of all the Petraean monuments.” — s ir Kenned y (1925, pg. 51)

This now-famous view of the Khazneh emerging from the Siq has become an iconic image of Petra, and quite justifiably so. It is stunning. And unexpected. Ironically, this was also one of the most difficult images to recapture without throngs of delighted visitors completely obscuring the narrow entrance. This challenge was exacerbated by requiring the photograph be taken during a particularly busy time of day to match the sharply angled shadows seen in the original photograph. Those wishing for a more private audience with the striking monument should arrive in those early hours when the ethereal tranquility of Petra breathes magic.

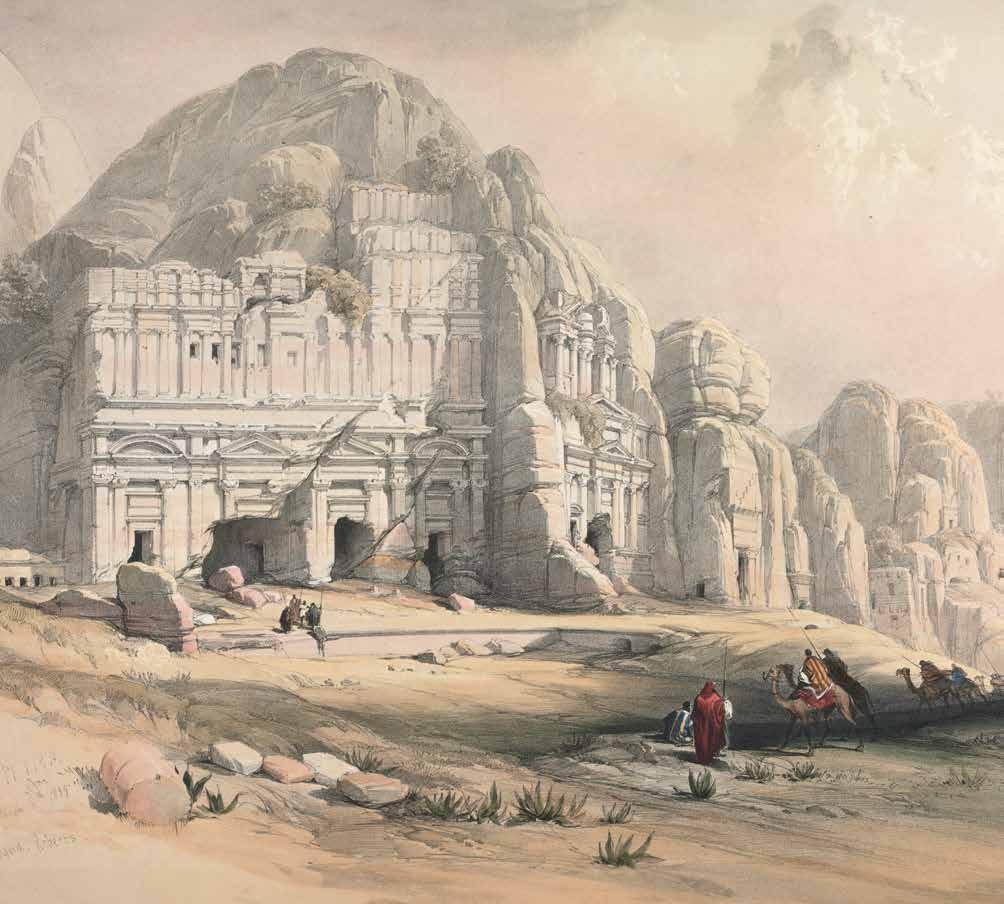

Looming over the main city center, the Royal Tombs are named for their intricate designs, unique attributes, and panoramic vistas. This region examines these regal tombs in greater detail, as well as exploring the upper trail leading to the peak of Jabal Khubtha and the city’s eastern edge.

“On all sides the gaunt red cliffs stand, honeycombed by rock dwellings and tombs, with here and there a pseudo classic facade or one that reminds you of Assyria or Egypt; immense headlands stand up against a sapphire sky. It is all new, strange and indescribably old; which may sound paradoxical, but which is strictly true.” — m rs. s teuart e rs K ine 7

“In the wall of al-Khubdha [al-Khubtha], stands a very badly weathered monument, generally called the ‘Corinthian’ tomb from the fact that the capitals of its columns are––or supposed to have been––of the Corinthian order. Next to this, northwards, stands an immense façade, unique in its design as regards Petra, which is a copy, in arrangement,

of the front of a Roman palace, and which it will be convenient to refer to simply as ‘the Palace’.”

— s ir Kenned y (1925, pg. 51)

While both the Corinthian (right) and Palace (center) Tombs can be seen in this photo, the Palace Tomb’s towering mass of columns, cornices, and friezes dominates the image. Even with the cleared debris, the scale of the photograph makes it difficult to convey the sheer size of this monumental façade. It is truly enormous, and it is crumbling. Many of

the upper decorations have required modern stabilization and reconstruction—some as recent as 2022. Sir Kennedy did include in his tome another image focused on the Corinthian Tomb, but its inferior quality and awkward lighting negated its viability for replication. Capturing the entire façade of the monolithic Palace for this repeat

image required placing the camera in the middle of a large, unshaded boulder field, a situation made far more delightful with the company of a young Bedouin child bringing tea from her mother’s nearby stall and helping to “stabilize” the camera tripod by stacking loose pebbles around its feet.

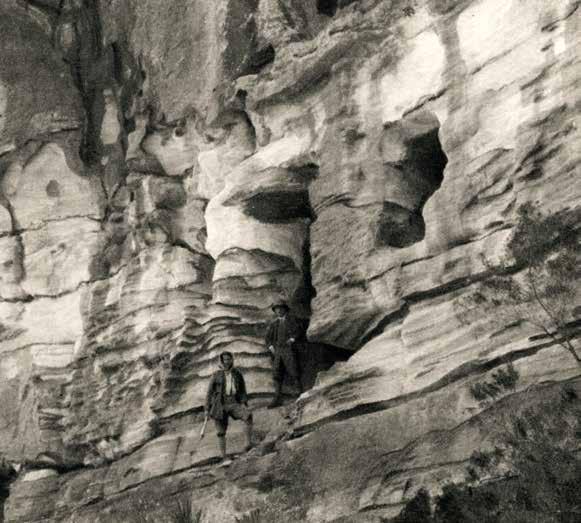

c ham BE r wi T h w in D ows on al- h a B is “On the same wall [of al-Habis], not much further round, is another ‘house’ with a window on each side of its doorway. [The photograph] shows that it is very rough in appearance and has obviously never had the trouble taken with its construction that must have been given to the other.”

— s ir Kenned y (1925, pg. 63)

With the harsh sun obscured by the massive al-Habis mount, the intricate dance of colors and minerals painting Petra’s sandstone sing in the soft lighting of these images. The deep purples, vibrant reds and oranges, and the stark, sparkling whites highlight the natural beauty in even the simplest of façades. In this instance, it is the very decay and deterioration of the stone face that enhances its grandeur. My field assistant Dr. Casey Allen (left) and I (right) occupy the same places as Sir Kennedy’s unnamed companions.

“Jabal Harun, the highest of the Petra peaks, has been identified by some authorities as Mount Hor and, according to Muslim and local tradition, claims the honour of bearing on its summit the tomb of Aaron, from which it takes its Arabic name. The view from the summit [of Jabal Harun] is magnificent, especially towards the north, where the

whole of Petra and the Wadi Araba lie before one, spread out as a map, with the line of Wadi Musa flowing in the latter far below, while the great temple of the Dair plateau stands out visibly from its setting of crags.”

— s ir Kenned y (1925, pg. 9)

The small white dome of this humble shrine can be seen throughout Petra, marking the highest point of the region—the shining star atop a sea of rusty crags and sandy basins. The panoramic views offered at the peak are reward enough for making the climb, especially the uncanny visage of looking down at the lofty Deir Monument located

just one peak away. The monument itself is a modest stone building, carefully maintained by locals and government entities, but it emanates a certain reverence that inspires tranquility and self-reflection. Replicating Sir Kennedy’s companions, from right to left, are Habis al-Bdoul, Rami al-Bdoul, Dr. Casey Allen, and Ahmad al-Masry.

p et R a I n the pR e S ent:

While Sir Kennedy’s photographs give us a glimpse of the past, mine reveal changes that bring us to the present. What we see today is the continuation of Petra’s extraordinary adaptability to its inhospitable environment. Where flash floods caused erosion, new plants have taken root, sometimes next to ruins freshly exposed by the rushing waters. Yet, through the centuries —regardless of nature’s relentless onslaught and stone’s natural decay—the carved monuments continue to stand steadfast as weather-worn sentinels guarding the resplendent city.

Part of what makes Petra such a fascinating place is its unique ability to incorporate change instead of resisting it. Even at the height of the city’s Nabataean Era, Petra was never only Nabataean but a multicultural array of style and design, drawing inspiration from Roman, Hellenistic, Greek, and Egyptian motifs. It seems each phase of Petra’s legacy has added new layers to the multifaceted landscape without negating or defacing those that came before. It is my hope that we can do the same by celebrating the past without degrading it.

In the modern repeated imagery, we see the new era in Petra’s occupational history: tourism. Traditional tents and shops have been erected by local Bedouins to share their handicrafts as well as their culture and histories. And yes, always with tea, a ubiquitous ritual that symbolizes their friendly and inviting culture. The authorities have built museums, restaurants, and facilities to accommodate the valley’s thousands of daily visitors. What better way to incorporate modern tourism into the rich historical record of Petra than as manifestations of hospitality, a cornerstone of Jordanian and Bedouin society? I frequently found myself to be the grateful recipient of extraordinary conviviality that is extended generously to Petra’s guests. It is almost an odd sensation to be so warmly invited to join in traditional meals for absolutely no other reason than to enjoy your company. The people of Petra exemplify a genuine desire to connect. Taking a moment to rest in a dwindling spot of shade on a scorching summer day can easily turn into hours of chatting and laughing with a passing local on their way home––complete with a dinner invitation you are simply not allowed to refuse.

Dr. Kaelin Groom is fervently dedicated to fieldwork, discovery, and fusing art with science. Her life's mission, as a scholar and as a person, rests in understanding how our beautifully complex world all fits together--what makes it tick--to proactively conserve the past for the sake of the future through heritage science and cultural resource management. By maintaining an active and contributing role in each arena, her career is built upon bridging the rift between education, policy, and scientific research. For more information, visit kmgroom.com.

Map of Petra showing the approximate location of each repeat photograph showcased in this book.