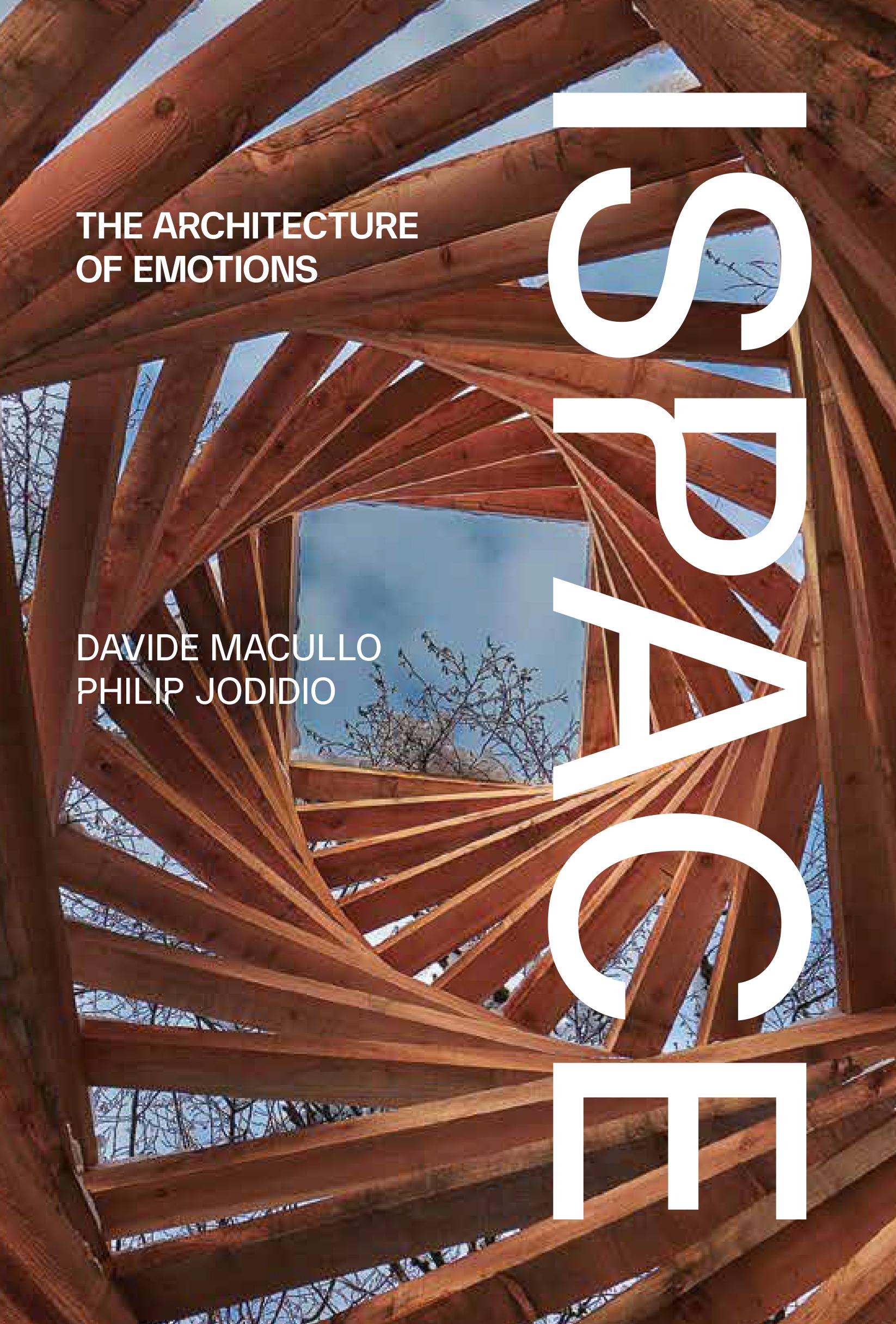

A WORLD THAT IS ALREADY THERE. DAVIDE MACULLO IN ROSSA

Philip Jodidio

Lausanne, December 11, 2024

In Frank Capra’s 1937 film Lost Horizon, a plane crashes in the Himalayas. Its passengers, who had been fleeing the turmoil of China, are led by Tibetans to the hidden valley of Shangri-la, where peace is a way of life, and the very process of aging has come to a halt. Based on a novel by James Hilton, Lost Horizon is merely one recent version of a story which recurs throughout the history of literature and art. It is the story of the Garden, of Paradise, lost and regained. The story remains symbolic of the search for meaning and understanding in a time when rapidity has all but overwhelmed contemplation.

The Val Calanca in the Italian-speaking region of the Canton of Graubünden (Switzerland) still brings to mind the image of a hidden paradise. Stretching about 25 kilometers from Roveredo in the south to Rossa in the north, it is a picture of idyllic mountain scenery which becomes more and more magical as visitors travel up its single access road. Rossa is located at 1,100-meters

above sea level, not especially high as mountain villages go, but this valley and this town have an unexpected and rich history. The proximity of the Val Calanca to the San Bernardino Pass, which used to allow (or block) access from the north since the time of the Romans, places the area along a historic path leading from northern Europe to Italy.

In the 12th century, the neighboring valley of Mesolcina, which leads to the San Bernardino and Calanca, were inherited by the De Sacco family who resided in the castle of Mesocco. They ruled Calanca until 1480 when Giovanni Pietro De Sacco (Sax-Misox, 1452–1540) sold the territory to the Milanese warlord Gian Giacomo Trivulzio (1442–1518) who was then in the service of Ludovico (Il Moro) Sforza, Regent of Milan. In 1496, the area joined the so-called Grey League formed in what later became Graubünden. Following the French conquest of Milan in 1499, Louis XII appointed Trivulzio marshal of France, governor of the duchy, and marquis of

Vigevano in Lombardy. Trivulzio was thus recognized as a baron of the Grey League and a feudal lord of the King of France. The warlord’s fame was such that he asked Leonardo da Vinci to design his tomb. Never realized, this grand equestrian monument survives only as a sheet of sketches (c. 1508) held today by the Royal Collection Trust. Trivulzio participated in the First Italian War of the newly crowned Francois I (1515–1516), when the French routed the combined forces of the Papal States and the Old Swiss Confederacy at Marignano in Lombardy in 1515 and captured Milan. The significance of this event is such that French school children still learn the date 1515 for “La Bataille de Marignan.” As a consequence of their defeat, the following year, the thirteen Swiss Cantons signed a “perpetual” peace agreement with France in Fribourg and placed themselves in the service of the King of France, a status that they retained until the French Revolution. Trivulzio’s star had faded in

this period, and he died in France in 1518. His successor was his grandson Gian Francesco Trivulzio (1509–1573). The people of Mesolcina succeeded in buying their freedom from him in 1549.

This rather convoluted bit of history goes a long way to explaining the deeper nature of the Val Calanca and its inhabitants. Set near one of the major routes between northern and southern Europe, their fate was closely tied to the north while their language originated in Lombardy. As poor as it may have been in the 16th century and before, the mountain valleys near the San Bernardino Pass were a place of refuge from the sometimes-violent events that swept over the Alps. In 1803, Mesolcina and Calanca became part of the Swiss Confederation with the rest of Graubünden, and in 1818 a convention was signed between the King of Sardinia and Graubünden for the construction of the San Bernardino trade route.

Davide Macullo

Buildings will outlive us, so we build for generations to come. As Bruno Munari said, our journey is a time best used to contribute to allowing “a civilised people to live in the midst of their own art.”

The architecture of necessity is a concept that covers every aspect of creating architecture. It offers the opportunity to organize thoughts, without necessarily finding or having to focus on a sequence of priorities. In creating a habitat, every element is considered, and, as such, can be instrumental in positively influencing a way of life. The two major themes we should consider in designing are the ecology of the Earth and human ecology.

Territory is the first essential element that building needs. The territory, our landscape, represents two prime conditions—the physical and the social—necessary for the transformation from a natural to a cultural condition. The first question, simple but fundamental

is, “Why do I have to build in this place?” The place is never neutral and has unique and distinct values. The shift in positioning of a wall or an opening by even one meter changes both the meaning and the perception of an environment. The physical part includes climatic, geographical, orographic, geological, urban planning, and preexisting conditions. The social aspect is constituted by cultural components such as history, traditions, social relations, the economy, and politics.

The task is to draw from the context until architecture becomes the link between the DNA of a place and its future. From a distance, a building is a form. The closer we come to it, it appears as a set of details filtering the outside and inside, and from inside it is a world, our world.

Our work is also imbued with a fundamental and universal value that is added to the specificities of a place: the psychology of the human being

and the capacity for perception and assimilation of space through the senses and intellect. The analysis of these themes branches in many directions and leads to reflections that go deep into the ancestral needs of humans, the human condition—linked to a place—and future ambitions. It is a theme whose potential depends on the ability of the designer to question themselves through scientific, humanistic, and personal research. Fundamental to obtaining valid results are dedication through great curiosity, unconditional love for life, and the passion to draw from emotional states what is necessary to transform spaces into inhabit. These are the emotions that design spaces.

Every space reacts and influences moods, thus influencing lives. This is the greatest responsibility we assume in contributing to sustainable growth and to the human spirit. Building with respect of nature includes respecting human nature. The ultimate goal is to provide for a world where every individual can cultivate and better their being.

Unlike the past, both recent and remote, today the architect must take on a more humanistic role and relate differently to the technical field of the profession. Technology has exceeded the assimilatory capacity of a single individual, making building an increasingly interdisciplinary subject. It is good that the designer manages to direct the orchestra by focusing on the emotions of the sounds that feed and engage the audience.

Currently we are witnessing a general phenomenon, which leads people to experience spaces constructed in an increasingly two-dimensional way. This is due to a series of factors that

have followed one another over time, starting with a more aseptic lifestyle, to the seemingly unstoppable increase in the concentration of populations in denser urban areas, and to the ease of rapid movement, which has increased in recent years.

The growing use of artificial intelligence, which unravels across the web of globalization, will result in an epochal change in the habits of the human race. We are close to complete robotization in in the capacity to create and print “not yet intelligent” buildings to be ordered online. These reflections lead to refine the role of the architect by choosing a possible evolution, which takes ecology into account in a broad sense. Even if today’s spaces are realized in the laboratory, and tomorrow they will be realized in situ, the figure of the architect will be necessary to give a reason to build. We imagine a biodegradable fluid substance, which stiffens on contact with air and 3D printers that spray it on site to build our habitat by reacting to the surrounding environment according to a predefined schedule. We will have a complete project that will lack the poetic component of architecture, guided by human doubts and emotions. The limits of humans leads to obtaining sublime results because they are cultivated in the sphere of fragile souls.

To the universe of these ingredients that contribute to creating a project, we add others that we consider to be tools. Time is one of the fundamental tools for Gestalt, an organized whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

A building resembles a tree: rootsfoundations, stem-structure, crownspaces. We want a building to be an intuitive organism: one that becomes an

extension of the senses, like having a long nose, enormous ears, eyes that see 3D, a huge mouth, and the longest limbs for the strongest embrace. Architecture must not require instructions to be lived in, but to offer a natural sense of orientation, to live in it simply by feeling at ease. Understanding the ebb and flow of human lifetimes creates the ability to make spaces static or dynamic based on their use, working on moods such as feelings of tranquility, aggression, fear, or safety.

The more reflections are articulated, reasoned, and sensitive, the more complete and continuous the experience is in living spaces.

A built place, like a natural one, must convey a sense of wonder in time—every day, but also with each passing year. This experience, linked to the expansion of time, brings us back to perceiving a place again in a complete way, no longer in two-dimensions only.

Human senses are the instrument of measuring surrounding space. The increase in technology leads to a slide in the use of perceptive functions. The task of the architect is, among other things, to take care of perception and stimulate people to “feel” embraced by harmonious spaces. The design is the connection of points, following priorities linked to contingencies on a three-dimensional grid like the stars in the sky.

In addition to the elements, the ingredients and the tools necessary for creation, there are other aspects that can be defined as the arteries of metabolic-space, comparable to the vital pathways of the human body and their structure that allow us to enjoy life in a positive way. One of these is to provide, for each environment, a visual escape route so that a person

never feels trapped in a space. Another is to find the center of gravity of a composition that creates the feeling of psychophysical balance at every scale of the intervention, from the territorial to the intimate. This reflection starts from recognizing our body as a container of fluids that needs a continuous balance to calibrate our internal motion, avoiding excessive oscillations. The organization of spaces and spiral paths completes the perceptive experience of human wellbeing. The principle of structuring paths and spaces in a spiral motion allows for a sequence of time necessary for the individual to pass from a public condition to a private one, creating an intimate context wherein to cultivate dreams. Architecture must facilitate these harmonic steps to allow social cohesion based on mutual respect. Once we arrive in the most intimate space of a built organism, we find ourselves confronted with ourselves, and from there we can project ourselves into the universe.

Photo by Adriana Bertossa