Eithne Massey

Eithne Massey

Reviews of Legendary Ireland, also by Eithne Massey

‘The celebration of the natural world and the close connection to it are everywhere in this striking collection.’

Irish Voice

‘Eithne Massey’s attractive book takes readers on a visit to twentyeight atmospheric locations across Ireland, each providing the cue for a retelling of the legends ... A book which evokes a time when storytelling had true status.’

Evening Echo

EITHNE MASSEY has had a lifelong love of the beautiful landscape of her native Ireland, with its history, lore and legend. Where the Waters Flow grew from a particular fascination with the living, ever-moving inland waters of Ireland. Eithne’s lyrical books include a perennial bookshop favourite, Legendary Ireland, in print since 2003 and published in many countries worldwide. She is also the author of The Turning of the Year: Lore and Legends of the Irish Seasons and has written numerous books of Irish myths and legends for children, among them the beautiful and popular children’s picture books Best-Loved Irish Legends, Legends of the Cliffs of Moher, and Legends: Newgrange, Tara and the Boyne Valley. Her numerous novels for young readers include the award-winning Blood Brother, Swan Sister, along with The Silver Stag of Bunratty, Where the Stones Sing, Michael Collins: Hero and Rebel, and her adaptation of the award-winning animated Cartoon Saloon movie The Secret of Kells.

Eithne Massey

First published 2025 by The O’Brien Press Ltd., 12 Terenure Road East, Rathgar, Dublin 6, D06 HD27, Ireland.

Tel: +353 1 4923333

E-mail: books@obrien.ie. Website: obrien.ie

The O’Brien Press is a member of Publishing Ireland.

ISBN: 978-1-78849-475-5

Copyright for text and author photographs © Eithne Massey 2025

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright for typesetting, layout, design © The O’Brien Press Ltd.

Cover and inside design by Emma Byrne.

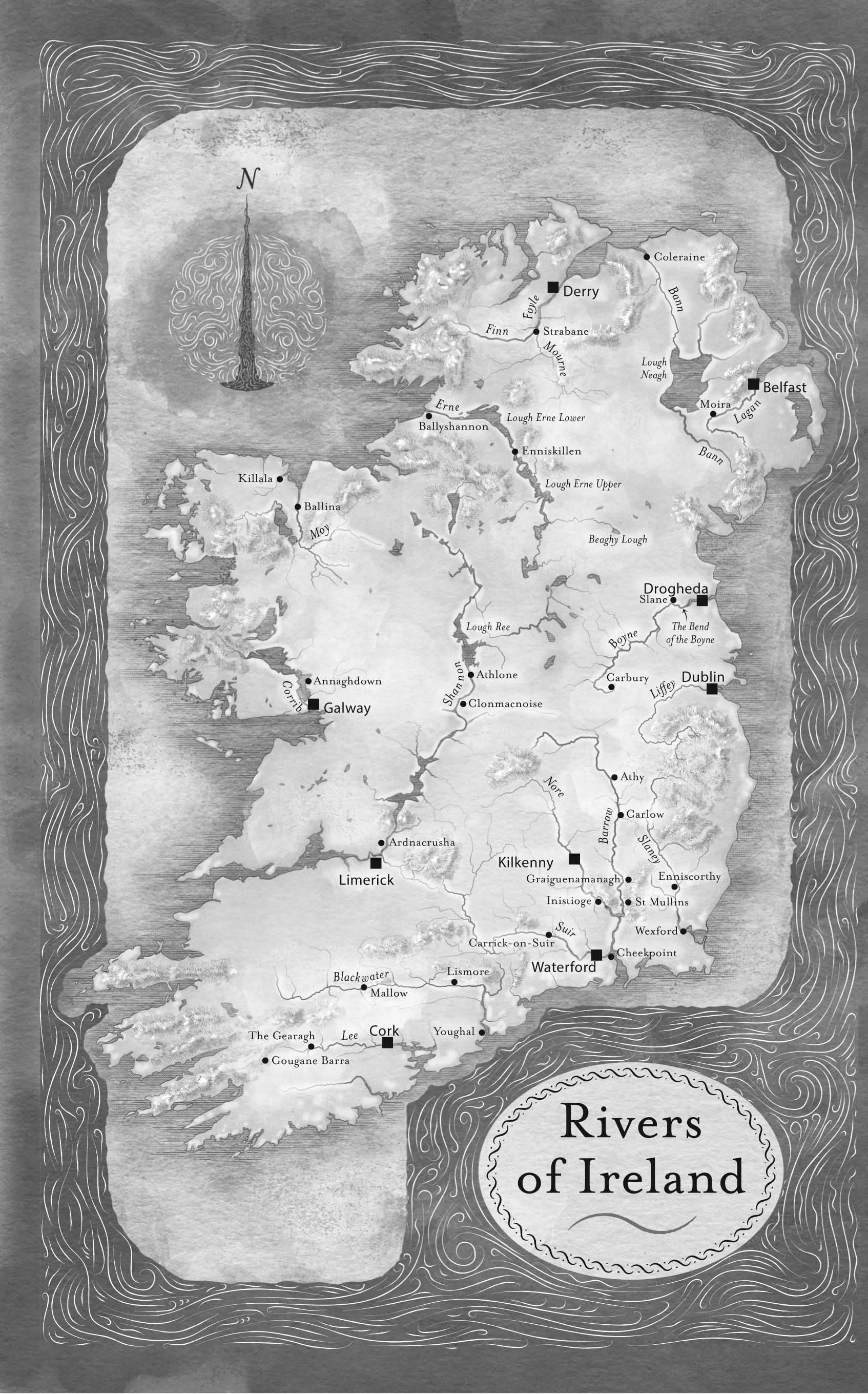

Map artwork by Anú Design, anu-design.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including for text and data mining, training artificial intelligence systems, photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

29 28 27 26 25

Printed and bound by Drukarnia Skleniarz, Poland. The paper in this book is produced using pulp from managed forests.

To the best of our knowledge, this book complies in full with the requirements of the General Product Safety Regulation (GPSR). For further information and help with any safety queries, please contact us at productsafety@obrien.ie

Published in

This book is dedicated to all those who love rivers, and battle for their survival.

Many thanks to all who accompanied me on my journeys around Ireland, in particular Jacques Le Goff and Patricia Donnelly. Thanks are also due to John Campbell and particularly Terry McKeown in Belfast for their insights on Sailortown. Many thanks also to Tara Doyle, Jessica Mc Carry and the staff of Dublin City Libraries, Ailbe van der Heide of the National Folklore Collection UCD, Dúchas, as well as the staff of The National Library and Graiguenamanagh Public Library. The websites from the various bodies overseeing Irish rivers and Ireland’s environment, both State funded and voluntary, are too many to mention individually but were invaluable during the research for this book. Ailish and Fidelma Massey, Emer Jackson and Rosena Horan helped me out with images. Finally, as always, a huge thank you to designer Emma Byrne and to Susan Houlden, the editor who for many years has helped enormously to make each of the books she has worked on a better one.

Ariver runs through us, no matter where in Ireland we may be. There will always be a stream, a river, a ditch nearby, leading to a larger channel of water and finally to the sea. These local watercourses are sometimes quiet and undramatic and are often ignored by those who pass by them every day.

Where the Waters Flow is an exploration of some of these shining waters and a plea to see them, hear them, care for them better than we have done. This book will take the reader on a journey around Ireland, looking at some of the history, myths and folklore associated with fifteen rivers, beginning with the Liffey and ending with the Boyne. The stories we will explore will come from every epoch of Ireland’s history, from the myths which tell of the first invasions of Ireland to twentieth-century folk accounts of fiddlers hunted by fairies. During our river journey we will meet medieval bishops, wild squireens and women who raise the dead. A book of this length cannot hope to do more than paddle in the shallows of the wealth of these stories, but it will hopefully inspire readers to go a little deeper. Each river and its valley is a world in itself.

Look at a map of Ireland. You will see a fine network of lines covering its surface, like blue capillaries, connecting each part of the country, the lifeblood of the island. Rivers are the great connectors. They were the path taken by the first settlers as they ventured upstream from the coast, into the heart of Ireland. They were also the route adventurers took downstream towards the coast when they wanted to travel beyond the sea that

surrounds us. For humans, like the salmon, rivers are both the call of home and the call to adventure. In the past they have been used as a protection from attack, acting as the frontier line between opposing tribes. This role can still be seen in the rivers that act as the dividing lines between counties. Rivers were also used as an access route by Gaelic and Viking raiders and by later invaders. There are many contradictions inherent in rivers, the source of life and healing that also carries the threat of death, the cradle of civilisation that can annihilate human life and our works. There are two sides to every river.

In mythical terms, rivers symbolise life and fertility, and also death. The mighty Ganges and the rivers of Eden, the sacred Nile and the holy River Jordan, the Otherworld rivers of the Lethe and the Styx are just some of the rivers which flow through the myths and religions of the world. A river protects the infant Moses, and another carries the head of the singer Orpheus downstream. But as well as being the fount of life, a river can rise up in anger. The Scamander river-god in the Iliad battered the murderous hero Achilles with a furious, roaring torrent that swept across the plains of Troy, because he had defiled the god’s waters with the bodies of the men he had killed.

Rivers in Irish myth and folklore are somewhat more benign, although we do have stories of rivers rising up and pulling humans into their watery and fatal embrace. Irish folklore tells us how some rivers take a toll of a human life every year, and how others have drawn back their waters so that a man seeking a drink dies of thirst. Often seen as a route to the Otherworld, sometimes the voyage there is not a voluntary one. Rivers carry the symbolism of the earth they rise out of and the sea they flow into. Throughout Celtic Europe, many water deities were placated with offerings to rivers and lakes, and they were sometimes used for gruesome divinatory purposes. Warriors in Germany placed newborn babies on their

shields and sent them to float on the water of rivers. If they floated, it was proof that the child was theirs.

Rivers were the place where kings and heroes were conceived and born. The Mórrigán straddled the banks of the river where the Dagda mated with her. It was in a river that Nessa gave birth to King Conchobar. Rivers have mourned with those who have lost their loved ones and provided inspiration and knowledge to those who walked their banks.

In historical terms, our Irish rivers have been used and sometimes abused by humans since settlers came and constructed their homes on the banks of the Bann around 7600 BCE. Our ancestors built in the shelter of riverbank trees, and they lived on the food the river provided. Rivers supplied the water that kept them alive, and they used its flow to cleanse themselves and carry their waste away. River water powered the mills to grind the corn for their daily bread. Tradition says that King Cormac created the first cornmill to lessen the labour of his beloved. As time has gone on, water power has been used to make everything from cloth to paper to gunpowder.

While many rivers have been harnessed for energy, the concentration of nineteenth-century industry in the eastern parts of Ulster has led to river pollution and changes to their natural configurations. Rivers like the Bann and the Lagan have suffered more from human interference than rivers such as the Moy on the country’s west coast. In our own times, the rivers of the heavily farmed south-east of Ireland are particularly vulnerable to pollution from fertilisers and agricultural run-off. Buried, channelled, canalised, dammed, blocked and poisoned – there is hardly an indignity that rivers have not suffered at our hands. The final indignity is that in the twenty-first century they are largely ignored. Rivers rarely even appear on road maps anymore. On other maps, the river has become the thinnest of blue lines, sometimes without even the courtesy of a name, viewed merely as an obstacle to be crossed or possibly a traffic

hazard with an old-fashioned humped bridge.

We have become blind and indifferent to the fact that our rivers, like so many others on the planet, are under threat. While the wet climate of Ireland means that we are unlikely to lose the flow of our rivers to drought, the possibility of preserving them in a healthy state literally hangs in the balance. As the twenty-first century moves forward, numerous Irish rivers are listed as seriously polluted. There has been little or no improvement in the quality of our rivers in almost a decade, and phosphorus and nitrogen levels remain high in about a quarter of them. Overall, the condition of just over half of our rivers is high or good, while the other half is considered moderate, poor or bad. There have been some improvements in the water quality in rivers such as the Liffey and the Slaney, but a decline in others such as the Barrow and the Shannon. Since the second half of the twentieth century there have been inestimable losses in biodiversity and in the numbers of every form of river life, from the pearl mussel to the salmon. These losses – in particular the catastrophic decline in salmon numbers internationally – owe much to climate change, but also a great deal to the phosphorus and nitrogen which flow into our rivers from the bright green fields on their banks. Industrial activity, industrial-scale forestry, sand extraction and human waste removal also play a role in the damage done, but intensive agriculture is the most widespread threat. Irish farmers, many of whom are finding it hard to make ends meet, have been reluctant to cut back on their use of artificial fertilisers or look at different ways of dealing with animal waste, a major source of nitrogen pollution. The growth of toxic blue-green algae, most obviously in Lough Neagh but also in other rivers and lakes all over Ireland, is one of the clearest signs of the destruction of the freshwater environment. While the situation in Ireland is not as serious as it is in some other European countries, there is no room for complacency. We are part of an international problem.

Globally, floodplains are considered among the most threatened of all ecosystems. The threats to rivers cross international barriers. Pollution upstream is carried down to other communities; the headwaters of a river are particularly vulnerable as the whole river system will be affected by any pollutants close to the source. Damming upstream can deprive another area of water. The massive dams being built in Turkey are just one example of the use of rivers as a political tool, taking water security from people living downstream, in addition to playing havoc with biodiversity. Areas of once fertile land in Iraq and Syria, bounded by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, have been left dried up and barren, partly because of climate change but also because of the dams upriver. Disruption of the flow of water raises the question of who holds the rights to rivers and their waters. There are many who believe that these rights are held by the river itself.

Recognition of rivers as individual and unique entities has developed into the argument that a river is itself a living creature. This is the argument put forward by the Rights of Nature, an international movement which is active in Ireland. Some county councils have already passed a motion recognising such rights, and there has been movement towards submitting a referendum proposal which would enshrine these rights in the Irish Constitution. Rivers in Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia have been acknowledged as having rights as legal entities, including the right not to be polluted. There has been a shift in our relationship to the natural world. Where before, the majority of people thought of the river as a resource, something to be exploited and bent to our will, there is now more awareness that the river – and the ecosystem it supports – has its own individual integrity.

The problem with listing a river as a legal entity is that it does not recognise that rivers are beyond human laws, and that their rights should perhaps at times supersede individual human ones, such as

that of land ownership. In addition, laws and directives are sometimes just ignored, and laws can actually bind and limit rights as well as protect them. The rights of rivers can flow into a morass of legal technicalities as easily as humans can, while using legal language when dealing with rivers can limit our understanding of their importance and innate power.

The language we use when we speak of rivers – words like flow, mouth, source, bridge, depth, bed – are all highly charged with imagery and emotional heft and evoke a response that no legalese can possibly achieve. Imagination and wonder are important factors in our relationship with rivers, though it must be admitted that calling rivers ‘sacred’ has not always safeguarded them. The sacred nature of the Jordan and the Ganges has not protected them from being two of the most polluted rivers in the world. But the legal designation of the river as a minor needing a ‘guardian’ somehow diminishes the river, pulling it into our human-focused approach. It also raises the possibility that the role of the guardian could be usurped by a group or individual who might not have the river’s best interests at heart. The Ganges was declared a legal entity (though it later had its legal status challenged and overturned by India’s Supreme Court) but is still a victim of massive pollution by humans.

If we accept that rivers are in some sense living beings, perhaps they may also become as angry as the Scamander river-god, as the Biblical increase in flooding worldwide demonstrates. Myths of apocalyptic floods going back as far as the Epic of Gilgamesh look to the future as well as the past. In Ireland, the combination of climate change, massive building on floodplains and the rampant increase in hard, impermeable surfaces around rivers has resulted in disastrous flooding in many communities. These local tragedies have served to re-focus our attention on rivers and to acknowledge their power. Whereas traditionally the approach taken to flood control was to create further barriers to the river’s freedom to flow, new approaches

such as re-wiggling – replacing the meanders in formerly straightened rivers – demonstrate our changing relationship with rivers.

This changing relationship can be seen in the huge numbers of people now fighting for the rights of rivers. The number of associations and groups actively struggling to save rivers and their wildlife has increased exponentially, both internationally and in Ireland, and there are far too many to list individually. These groups are dedicated to the protection of the fish, fowl, insects, animals, plants and most of all the water of our rivers. These are the people who have taken on the voice of the river, and these are the people to whom I have dedicated this book.

Although they cannot speak in human terms, it would not be true to say that rivers do not have a voice – nothing is more alive and various. The rippling, whispering, gurgling, bubbling, sighing – and sometimes roaring – they make as they flow has its own story to tell. To be on or in a river brings us out of our normal modes of being. Simply walking along a riverbank, watching the light on its water and listening to its music, can lead us to a place where we lose our sense of individual consciousness and become part of its flow. Even urban rivers, bounded by stone or concrete, can take us out of our everyday selves, as we look at the light reflected from the water under ancient stone bridges or watch the water transformed by the ripples of rain falling. That is one of the great gifts they give us. For rivers are the great givers, endlessly patient with creatures whose lifespan is not even a drop in their endless flow, their youthful rushing and falling, their turning back on themselves, their last meanderings.

Rivers pull us in. In Irish myth there is a strong connection between the music of water and the bubbles that can be seen on the surface of rivers with the deepest form of poetic inspiration, or indeed revelation. Stories describe the hypnotic state that is familiar to those who spend time listening to the voice of the river and watching its light-filled flow.

In these myths, the music of the water is sometimes identified as the sound of the Sídh, Ireland’s fairies, or of mermaids. Women and women’s voices are closely linked to rivers, from the Washer at the Ford to the drowned girls who sought knowledge at forbidden wells and were swept away, becoming the water itself. The writer Manchán Magan points out that almost every river is gendered as feminine in the Irish language, and the vast majority of Irish stories relating to the birth of rivers are connected to a female.

Irish folklore abounds with stories of the Sídh linked to rivers.

Fairies, though they cannot cross running water, often lure humans to the other bank of the river, where they do things differently and where time ceases to matter. There is an interesting connection between the hypnotic effect of rivers, the connection with the Other Crowd (as the Sídh are often referred to) and what is called the state of ‘flow’. ‘The Flow’ is described by neurologists as the condition when one is deeply engaged in an activity, concentrating hard, fully immersed. There may be difficulty involved in the activity, but when we are ‘in the flow’ we feel not stress but pleasure. In this state time passes and we have no idea whether it’s been ten minutes or half an hour since we started the task. We have been taken by the fairies of the central nervous system to another world where time works differently. Interruption of this state can feel like a sharp and painful loss.

Perhaps a river feels a loss when its flow is blocked and diverted by weirs and dams and mill streams. Or perhaps it just shrugs and gets on with the job as water does, taking the path of least resistance, while over time making channels through rock and moulding entire landscapes. The message of the river is constant renewal and the capacity to keep changing (we never step in the same river twice) while remaining inherently the same.

Rivers have mouths, like humans. They have sources, like stories. In the stories which follow I hope that the rivers will speak to you.

‘the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of’ James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Blessington Bridge and the River Liffey, 1938.

The Liffey, once known as the Ruirteach, the wildscrambling one, starts quietly enough as a small dark spring (or several small dark springs) in the rugged landscape of the Wicklow Mountains, close to the Sally Gap and on the western slopes of Tonduff mountain. It is, like the source of so many rivers, undramatic; an amalgam of pools and rivulets which spring up in an expanse of bog, and any exploration of the Liffey’s beginnings will be a boggy experience. What is known as the Liffey Head Bridge is not, in fact, the highest point of the river, which is further up the mountains, but the dark peaty pools, surrounded by moorland and exposed to the winds and birds wheeling, does give a sense of the river’s beginning.

Dublin, the Liffey’s city, also takes its name from the words Dark Pool or Dubh Linn. From the source, the river makes its way westwards towards the sun setting on the plains of Kildare. The Liffey is a contrary river; instead of taking the most direct route east over the mountains to the sea, she meanders in a circular way through three counties before reaching Dublin Bay. Her journey takes just under 130 kilometres, although the source and mouth are no more than 22 kilometres apart.

Over time, the Ruirteach saw its name changed to Life or Liffey, the plain which covers much of Kildare and west Dublin. The legend associated with this is that Deltbanna, who acted as butler to King Conaire Mór, travelled over the plain with his wife, Life, who, seeing its beauty and fertility, asked that it should be named after her. Thereafter:

Deltbanna dealt out no more liquor for the men of Erin until the plain was called by his wife’s name.

There are other sources for the name Life, including a drowned princess and a maiden converted by St Patrick. The Liffey is also

associated with the high king Cairbre Lifechair, son of Cormac Mac Airt and lover of Life. While Cormac is considered one of the greatest high kings of Ireland, famous for his wisdom, Cairbre is better known for the bitter enmity between himself and Fionn Mac Cumhaill, the leader of the Fianna, the renowned troop of hunters and warriors. Their rivalry resulted in Cairbre’s defeat of the Fianna at the Battle of Gabhra. Cairbre was not given a chance to celebrate his victory; he killed Oscar, grandson of Fionn, but Oscar in turn took Cairbre’s life.

A less tragic story tells how St Moling came from his hermitage on the River Barrow to ask the King of Leinster to reduce his rent. The king agreed but changed his mind after St Moling had left and sent his soldiers in pursuit of the saint. When St Moling saw the men following him, he made the Sign of the Cross over the Liffey, and the waters rose up and blocked his pursuers.

Before it reaches the Plain of Life, the River Liffey rushes down to the beautiful Blessington Lakes, a reservoir created by the damming of the river at Poulaphouca for a hydro-electricity scheme. Built in the 1930s, this was one of the earliest of such projects in the new Irish state. Further west is the site of the Poulaphouca Hydro-Electric Dam and the water treatment plant for the two reservoirs which still provide most of Dublin’s water. The writer A.A. Luce describes the calamitous effect the creation of the reservoir had on the trout population of the rivers that fed it. For the first season the fish ‘had a right royal time of it’, but then tapeworm killed practically all of them, as the reservoir was a perfect breeding ground for disease. Prior to the damming of the river, travellers from Dublin would take a tram to view the three pools formed by the steep incline of the waterfall at Poulaphouca. The middle one was where the Pooka (Púca), that fairy creature which often took the form of a black horse, was said to live. This is now the main road between Blessington and Baltinglass. Before the bridge was built here, travellers would have

passed through Ballymore Eustace, a quiet village which has known its share of excitement in the past. Ballymore Eustace is where the river settles down and becomes a river of the Pale, the area around Dublin that was controlled by English settlers during Norman and Tudor times. Its six-arched bridge was a strategic crossing point of the Liffey and was a target of attack from the Irish of the Wicklow Mountains, notably in 1578 when Rory O’Moore burned the town. As late as the 1820s the town was described as a place of some consequence. Now, it is possible to pass through Ballymore without realising the river is there at all, as it is tucked away behind houses and the church, although there is a lovely walk along its banks. The castle that guarded the village is long gone. The Church of Ireland graveyard still holds some grave slabs, an effigy of a sixteenth-century Fitzeustace knight, and its baptismal font dates from the tenth to eleventh century.

The other major feature of Ballymore was its mill. Probably dating as far back as the church, the mill at Ballymore is listed as one of the possessions of John Comyn, Archbishop of Dublin in the late twelfth century. The ruins are a short, wooded walk from the bridge, and date from 1802 when a woollen mill was built by Christopher Drumgoole. It went through various incarnations, but by the late 1800s Copeland’s woollen mills were well established, using the wool from the sheep that grazed the surrounding Poulaphouca, pictured in the nineteenth century.

mountain pastures. By the beginning of the twentieth century the mill had declined and eventually the complex had become little more than a large atmospheric ruin. It has recently been given a new lease of life by plans for the conversion of parts of the building into a micro-distillery.

The Liffey mills have from earliest times served the needs of those who lived on its fertile plain, with its herds of sheep and fields of grain. There were 200 mills in the river’s catchment area: woollen, corn, paper, cloth, printing mills for calico, flour and tuck mills, mills for grinding linseed oil and even making gunpowder. Many of these mill buildings, long neglected, have been transformed in recent years, but even into the 1930s some had a sinister reputation. One, located between Chapelizod and Lucan further down the Liffey, was already in ruins when the Folklore Commission recorded the story that it had been built by the Devil in a single night. This is an international tale, but it also echoes stories of that mythical builder the Gobán Saor, who in turn may be an incarnation of the ancient Irish smith-god, Goibhniu. Mills figure prominently in folklore and folktales, with saints like Moling building miraculous ones on the banks of the Barrow, and the Hag of the Mill, Lonnach, playing an important role in the story of King Suibhne.

The middle stretch of the river is quiet and wide, travelling across the great fertile plain of Kildare, long settled by the Normans and after them the Anglo-Irish. Families farmed the good land, and the wealth of these landlords resulted in the construction of some of the most impressive Georgian mansions in Ireland. Carton, Castletown, Straffan, Sandymount and Millicent are just a few of these. These big houses and the lives of those who lived in them and worked in them – and their gardens – have ultimately left us with a legacy of grace and beauty. And despite the proximity to a massively bloated capital city, there is oasis after oasis of vibrant wildlife here.

The Liffey valley is the only place where I have ever seen

a kingfisher in Ireland. This most elusive of river birds, the tiny kingfisher or cruidín is mainly spotted as a flash of blue along the riverbank. As with many other species, kingfishers were hunted down in the nineteenth century, their beautiful feathers used to adorn fashionable hats. The good news is that, like all wild birds, they are protected in Ireland and the kingfisher is still widespread. Their main habitats are the Boyne, Cork Blackwater, Barrow and Nore. Kingfishers have some strange habits, using regurgitated fish bones as building material in the nests they make in burrows. As the fledgelings grow and the number of waste pellets increase, home life must become rather unsavoury. For whatever reason, for their second brood, the adult kingfishers move

to a new nest. This practice was explained to me as a smart move as it ensures that adult children don’t move back in!

Writer Arthur Young greatly admired the grand houses of the Liffey valley and their wooded estates when he toured Ireland at the end of the eighteenth century, and was particularly impressed by the plantations of trees, some of which still survive. In more recent times, Ireland’s fast-growing population has resulted in the creation of very different kinds of estates, of both the industrial and the housing variety. Industry and the large housing complexes of the dormitory towns of Dublin now dominate the valley.

Large multinationals have sprung up. What were small villages have become large towns. Clane is a typical Liffey town in that its population increased from 600 in 1971 to over 8,000 in 2022. Nearby is Bodenstown graveyard, the quiet resting place of one of Ireland’s national heroes, the political and revolutionary leader Theobald Wolfe Tone. Clane is also the burial site of Mesgegra, King of Leinster, killed by the Red Branch knight Conall Cearnach during a conflict with the Ulster king. On her husband’s death, Mesgegra’s wife Buan lifted up her cry of lamentation, ‘which was heard even unto Tara and to Allen, and she was dead’. She is said to be buried at Mainham, north of Clane, where there is a holy well and the remains of a motte, now surrounded by apartment blocks.

In the eleventh century, the monastic settlement at Clane was one of the many victims of Viking raids. The Vikings founded Dublin, coming from the east up along the river. The early core of the city was at Wood Quay, close to where Dublin Castle is now. But there was also a large Viking settlement further west, at Islandbridge, where the river is no longer tidal. The presence of the Phoenix Park on one side of the river and the War Memorial Gardens on the other has preserved a sense of rural greenness in this western enclave of the city. The stretch of the river here was once famous for its salmon, which may be one of the reasons the Vikings chose

to settle there. The Viking finds in the Islandbridge/Kilmainham area constitute the largest Viking burial plot outside of Scandinavia, with fifty-nine graves currently identified. Viking finds were made in the area from 1832 onwards, and more discoveries were made in the 1930s when the War Memorial Gardens were created. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, yet another sword and spearhead were discovered there.

This site must have been a massive burial complex, stretching westwards along the bank of the Liffey and southwards towards the ancient monastic complex of Kilmainham. The remains date from circa AD 825. The finds include tongs and weights and spindle whorls and what are possibly needle cases, so it seems likely that there was a thriving settlement here, one of the earliest longphorts in Ireland. Glass, amber, white metal and bronze ornaments, iron swords, spearheads and shield bosses have been found, as well as human remains. The ford at Islandbridge continued to be an important strategic crossing point on the Liffey, marking the Irish National War Memorial Gardens, Islandbridge.

western reaches of the settlement of Dublin and the site of more than one battle.

The sleeping Viking warriors and their families on the hill overlooking the river are now part of the Irish National War Memorial Gardens. The Gardens, constructed to commemorate those Irish soldiers who died in the First World War, has thankfully been rescued from its former neglect; as late as the 1990s it held the sense of a place abandoned. Now, it has blossomed, with beautiful rose gardens and a lovely river walk. At Islandbridge the river shows the last vestiges of its rural self, uncorseted by stone walls, flowing freely through green banks bordered by trees.

From the Memorial Gardens it is possible to walk westwards along the southern bank of the Liffey to Chapelizod, a place much associated with James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, a book built around the river itself. In the novel, H.C. Earwicker dreams. Beside him in his bed is Anna Livia, his wife, once a sprightly young girl, who begins as ‘a cloud, shower, a rivulet, brook, a young thin pale slip of a thing’, becoming Missislifi and falling into night and the sea, ‘and it’s old and old it’s sad and weary’, with her ‘old father’, her ‘cold mad father’. The two washerwomen on either side of the young Liffey babble and gossip and the language of the book tries, as Joyce himself said to critic Arthur Power, to emulate the language of water itself.

Joyce also connects Chapelizod with the legend of Tristan and Isolde (or Iseult). This is one of the stories told by the troubadours of the Middle Ages, part of the Arthurian Cycle. There is a tradition that says ‘Izod’ comes from the name Iseult and that this was the home of Iseult, the lover of Tristan and wife of King Mark, heroine of this tragic cycle of love and revenge. In Irish, Chapelizod is Séipéal Iosóid, meaning ‘Iseult’s chapel’. Connections are frequently made between this story and the Celtic tale of Diarmuid and Gráinne, but there is actually not that much connecting the two stories, apart

from the fact that the young woman, promised to an old king, falls in love with a young warrior and they run away together. Gráinne is a very different character from Iseult; she is a woman with a strong will who mocks Diarmuid into making love to her. As they cross a river on their flight and the water splashes her thighs, Gráinne tells him that the river has more courage than he has.

Other sources link the origin of this unusual name – still called Chapel Lizard by some of the older locals – to Lazer or Leper. There was a leper house in nearby Palmerston.

The writer Sheridan Le Fanu grew up close to Chapelizod and set some of his stories nearby. He described it as a gay and pretty village, and it is one of the few village suburbs of Dublin that has managed to retain a certain charm, though Dubliners no longer come out during the long summer days to visit its famous Strawberry Beds.

In its heyday, the Strawberry Beds was the scene of outdoor dancing, drinking, flirtations and probably a lot more. Cars from the city were kept busy ferrying groups of young people back and forth to admire the river views, while eating strawberries served on cabbage leaves by the local growers. The concentration of various army barracks in the area must have resulted in a strong military presence and I imagine the place had something of a louche atmosphere. It was certainly considered a venue for romance; honeymooners from Dublin came out here if they could not afford to go further afield.

The Liffey between Chapelizod and Islandbridge is the site of a true story involving James Joyce’s celebrated frenemy Oliver St John Gogarty, a man of a multitude of talents and writer of rip-roaring memoirs. He is the first character to appear in Ulysses, as ‘stately, plump Buck Mulligan’. But there was much more to Gogarty than a wild young buck in a Martello Tower. He was a respected surgeon, sportsman, writer and politician. A friend of W.B. Yeats, George Moore described him as ‘author of all the jokes that enable us to live

in Dublin’. Distrusted by many, Gogarty’s wit was often scatological and sometimes wounding, and even as a member of the Irish Senate he could not resist a joke, suggesting that the stone bird on the Phoenix Monument in the Phoenix Park should be included in the Wild Birds Protection Bill. But he was a serious supporter of social and economic reform, especially for action on the tenement housing and substandard sanitation that was causing the astronomical death rate in the poorer areas of Dublin. Mercurial and restless, Gogarty ended his days in America. One has the feeling that the piety of the new Irish State made him miss the Dublin of his youth, when one of his claims to fame was his encyclopaedic knowledge of Monto, the red-light district of Dublin.

Gogarty was made a Free State senator in the 1920s, thereby bringing on himself the ire of the anti-Treaty side, who burned his house in Renvyle in Galway. They also kidnapped him, luring him into a car on the pretence of a patient needing help. He was huddled in a fur coat – it was a freezing January day – and driven to a house on the Liffey, near Chapelizod. There he was told he would be shot if some Republican prisoners were not released. The garden of the house led down to the banks of the river and Gogarty decided that the best chance of escape lay there. He convinced his captors to take him outside, saying he urgently needed to void his bowels. He then slipped his arms from his coat and made for the river. Fifteen minutes of freezing water and vigorous swimming brought him to freedom. Years later, when the Civil War was over, Gogarty released two swans on the Liffey as a sign of gratitude, and who knows, perhaps it is their descendants that can be seen on a summer’s evening from the War Memorial Park, tranquilly gliding on the water, unworried by the politics of the old, or indeed the new Ireland.

The essence of tranquil beauty, swans glide across the river, creatures of myth and magic. Leto was the mother of the heavenly twins Artemis and Apollo, who hatched from two eggs; she had been impregnated by Zeus in the guise of a swan.

European folklore is full of swans, viewed as solar symbols, often shown wearing golden chains around their necks. Swan maidens fly and float backwards and forwards in the myths of the Scandinavian and Germanic people and are prominent in Irish myth. The best-known story is that of the children of Lir, where, out of jealousy, their wicked stepmother turns four children into swans. The legendary hero Mongán took the form of a swan, as did the three sons of Tuireann; and at the end of the story of Midir, one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, and Étaín, his lover, the couple’s final transformation is into two swans. The story of the god Aonghus and the Swan Maiden Caer Ibormeith is a love story with an unusually happy ending. Not so that of Dealfaith. The great hero of Ulster Cú Chulainn threw stones at a flock of white birds flying overhead, unaware it was a woman of the Sídh and her handmaidens coming

to declare her love for him. Flocks of white birds often foretell magical events in ancient Irish stories. In Mayo folklore, swans carry the souls of virgins.

Bronze Age Ireland celebrated the swan in artefacts such as the Dunaverney flesh-hook. This ceremonial feasting tool is beautifully decorated with two groups of birds: on one side a group of ravens and on the other a family of swans, two adults and three cygnets.

Swans may have been a taboo bird in terms of hunting, although in later times a roasted swan was the centrepiece of many a medieval feast, and there are recipes given for the delicacy up until 1861, when Mrs Beeton’s cookbook appeared.

Swans are not considered endangered in Ireland. In recent years, the Swan Census has shown an increase in Whooper swans, with many more of them migrating to Ireland from Iceland during the winter months, and a decrease in the numbers of the Bewick’s swan, which no longer has to travel as far south as Ireland during the winter in order to survive. The third type of swan found in Ireland is the Mute swan, which in many cases stays in Ireland throughout the year.

Swans have the gift of seeming unperturbed by proximity to humans, bringing beauty into everyday city life by nesting everywhere, under bridges, on canals, beside the roar of trains and traffic and humans. Gliding along tranquil waters, they are an inspiration to poets, artists and storytellers. As Seamus Heaney put it in ‘Postscript’, the sight of swans on a grey lake can still catch the heart off guard and blow it open.

And so, eastwards, to Dublin. Past the many barracks that have become centres of culture rather than defence, past the old markets at Smithfield, rejuvenated with stone and iron. Past the old sites of colonisation and control, along the quays, making our bows to the

Four Courts, the monolithic Civic Offices and, a little away from the quays, Dublin Castle.

The river’s story has always been overshadowed by and in some ways overshadows that of Ireland’s capital city. Dublin and its river have borne the brunt of every invading force since Ireland was first settled, and the city was the site of the 1916 Rebellion, which finally brought Ireland the independence it had sought for so many years.

At the time of its early twentieth-century creative flowering it was a small, intimate city, where it was said that you could not walk the length of Grafton Street at around four o’clock without meeting someone you knew. But despite its recent growth, the faint sense of Dublin still being a place where everyone knows everyone, or at least knows someone they know, remains part of its charm.

Dublin’s history is a rich tapestry of stories and songs. The city has experienced change after change during the last hundred years, since Ireland became an independent state and Dublin became a capital city of a young nation. Nowadays, the city is beset with the problems that massive growth and creaking infrastructure bring with them. The Greater Dublin area is home to almost half of the Irish population. When we look down the tidal Liffey to the east, to the new skyscrapers of Dublin Port, it does not seem possible that this is the shabby-genteel city Joyce wrote about, mourning its spiritual paralysis. What was a wasteland of disused storage sheds and abandoned factories has become the redeveloped Docklands area, looking out beyond Ireland to the sea and the world beyond. Financial centres and technical hubs, multinational giants, their giant logos dwarfing the humans passing underneath them, overpriced apartments and expensive restaurants – everything shouts capital investment. Walking along the Liffey quays on a summer’s evening, away from the shadow of Christ Church, with its ghosts of Darkey Kelly (a famous murdering madam), past the house on Usher’s Island where Joyce set his short story ‘The Dead’, the city