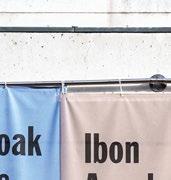

Ibon Aranberri PARTIAL VIEW

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

With texts by: Ruth Noack, Shep Steiner & Miren Jaio

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

With texts by: Ruth Noack, Shep Steiner & Miren Jaio

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía,

Madrid

Museum of Contemporary Art of the Basque Country, Artium Museoa, Vitoria-Gasteiz

With texts by: Ruth Noack, Shep Steiner & Miren Jaio

pp. 6–224

Plates 1–64

SPENDING TIME IN PARTIAL VIEW

pp. I–XII

SNOW CHANGES EVERYTHING

pp. XIII–XXIV

MIREN JAIO

DI FRONTE E ATTRAVERSO

pp. XXV–XL

p. 9 – Contraplan, 1996

p. 13 – Disorder, 2007

p. 17 – Mapa interrumpido, 2000–2004

p. 31 – Mirando a Madrid desde la distancia, 2000–2024

p. 33 – Protopaisaje (working title), 2003

p. 39 – Zulo beltzen geometria, 2019

p. 45 – Inverted Schemes, 2003

p. 49 – S/T (Detour), 2011

p. 51 – Mar del Pirineo, 2006

p. 57 – PLACED SOMEPLACE WITH INTENT / ASMOZ NONBAIT JARRIA, 2014

p. 58 – Pronóstico meteorológico de Madrid del 10/04/2014 al 06/06/2014 escrito en euskera, 2014

p. 65 – Barrutik kanpora, 2019

p. 71 – Macrosistema, 2011

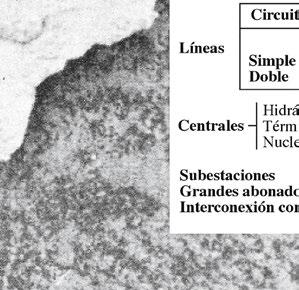

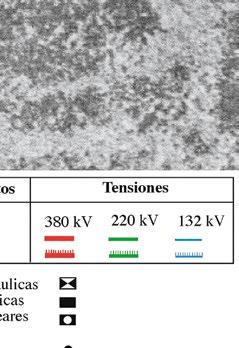

p. 73 – Política hidráulica, 2004–10

p. 81 – Exercises on the North Side, 2007

p. 89 – Untitled, 1996

– Positions (working title), 1996

p. 93 – Cavity, 2005

p. 97 – S/T (San Pellegrino), 2016

p. 99 – Firestone, 1997

p. 103 – Home & Country, 2018

– Basauri, 1998

p. 107 – Dam Dreams, 2004

p. 111 – S/T (Territoire), 1997–2024

p. 115 – Transakzio denbora, 2003

– S/T (Taula), 2003

– S/T (Retratos), 2003

p. 121 – S/T (Blackout), 2003

p. 127 – Untitled, 2005

p. 129 – Piedra e intersección, 1994

p. 131 – Itzal marra, 2019

p. 139 – Modelos y constructos, 2014

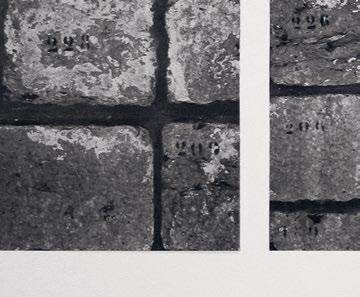

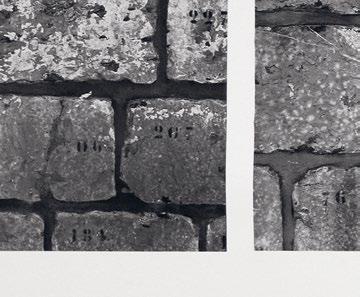

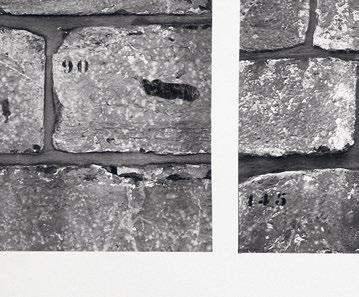

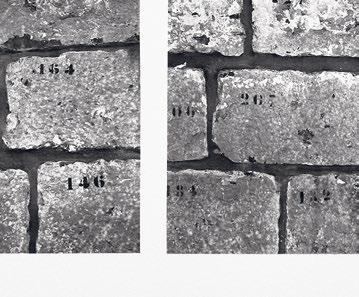

p. 143 – Obstáculos para la renovación, 2010–22

p. 149 – …

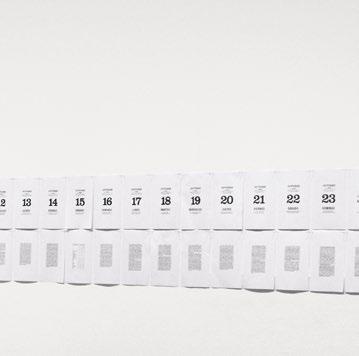

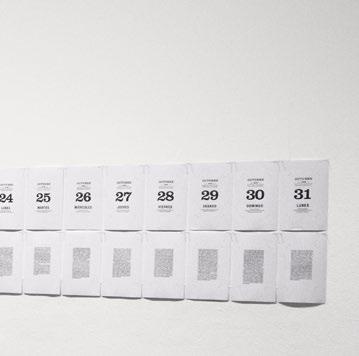

p. 151 – Almanaque, 2022

p. 157 – Compendium, 2022

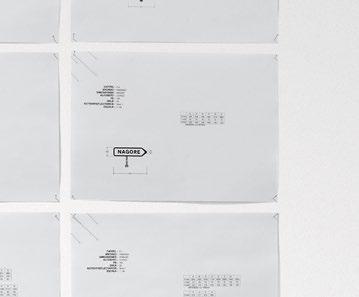

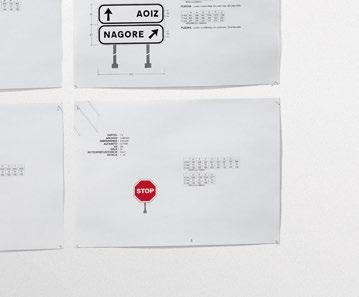

p. 161 – Operatori, 2021–ongoing

p. 171 – Makina eskua da, 2016

p. 181 – Sources Without Qualities (2), 2017

p. 185 – Dana, 1994

– Laranjak, 1994

p. 189 – Gramática de meseta, 2010

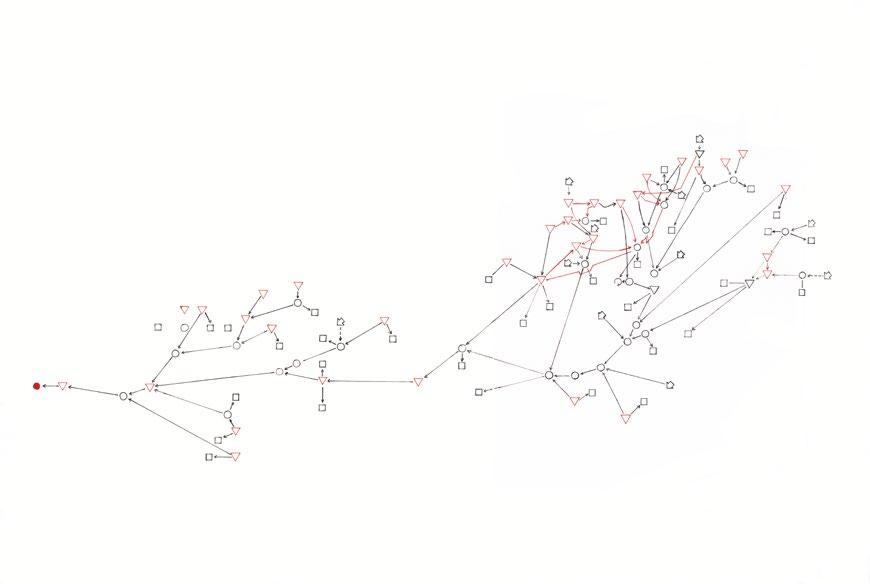

p. 195 – Organigrama, 2010–11

p. 203 – Despoblación (working title), 2010

p. 209 – Apariencia tridimensional, 2013

p. 213 – Modulaciones, 1998

p. 217 – Untitled, 2010

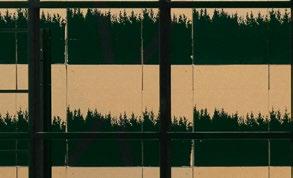

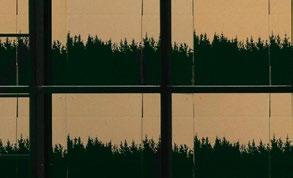

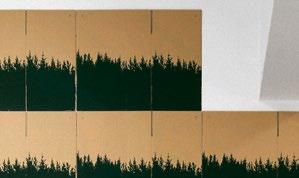

p. 221 – Gaur Egun (This is CNN), 2002

Single-channel video on three monitors placed on three medium-height stands with a perimeter matching that of the monitors, and a gap of approximately 50 cm between them

Color, no sound, Betacam SP

Duration (in loop):

– Video 1: 9 min.

– Video 2: 7:25 min.

– Video 3: 11 min.

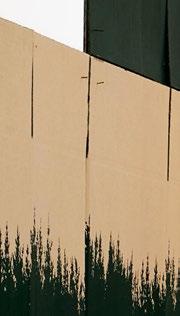

In the first recording, a video camera has captured the recurring shape of the forestry plantations from a distance. The tracking shot was repeated several times through the window of the bus traveling along the northern highway. These images are accompanied by footage of other camera movements—panning and zoom in and out—capturing the same plantations from different angles.

The retrieval, editing, and playback of this footage attempts to merge the repeated image of the jagged outline, creating a constant movement: a continuity of views and looped sequences divided across three monitors.

The texture of the camera used in television news bulletins reflects the kinds of images produced at the time. They are typical of professional media prior to digital technology. With twentieth-century industrialization, the Pinus radiata species gradually replaced the native forest. This artificial transformation of the environment gradually darkened the tonal range of the horizon.

This exercise carried out through the camera aimed to recreated the generic archetype that will replace the image of a depleted ancestral landscape. After several years, the obsolescence of a disused medium meets the vision of a landscape in decline. At the same time, forest species have been getting sick as their ecosystem deteriorates as a result of successive monoculture farming, without the power to resist new global pandemics.

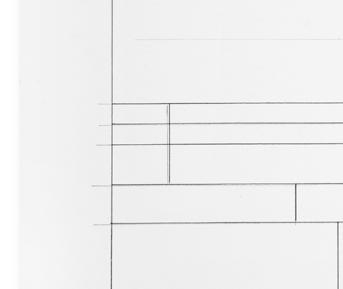

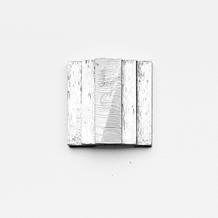

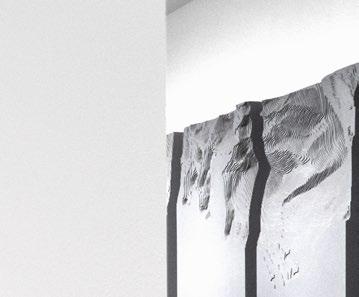

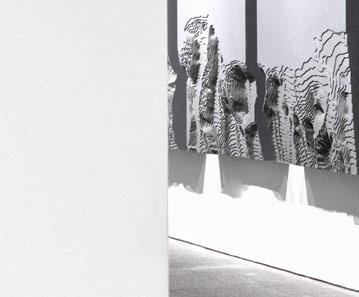

Spruce wood and wood stain

Measurements of each board: 14 × 2 × 481 cm

Dimensions: 481 × 265 cm

The timber-slatted surface was conceived by the museum curators as a way to present archival material from various projects in the artist’s solo exhibition. Timber commonly used in DIY projects was stained in a dark color to match the floor of the exhibition hall, which has a late nineteenth-century hardwood finish.

It was originally intended as a raised horizontal platform on four trestles. This idea was discarded when the rest of the works resolved the exhibition on their own. However, a decision was made to keep it in the room as a freestanding material element, devoid of content, juxtaposed to the floor, without the trestles.

In the next exhibition, this surface was displayed as an autonomous form, in a vertical position leaning on the wall to emphasize its status. On subsequent occasions it was placed in various positions, adapting to the different architectural characteristics.

On each occasion, the surface is assembled from the boards with tongueand-groove joints. The handling of the timber during the assembly and dismantling of the surface leads to erosion and creates marks that remain visible, as consequences of its own past. After being in storage for several years, the boards have been reassembled to create the full surface, repeating the same exercise in the museum space.

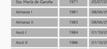

Exhibited in:

1. Integration, Kunsthalle Basel, 2007

2. Disorder, Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt am Main, 2008

3. Organogramme, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 2011

4. Partial View, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2023

5. Entresaka, Artium Museoa, Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2024

Projection of 80 35mm slides

4 printed sheets, A4 format

Orographic map. India ink on onion paper, A3 format

90 screen-printed T-shirts

Project to Turn the Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant and the Affected Lands into a Space for Public Use, 1998

Carmen Abad Ibáñez de Matauco, architect

Private collection

Untitled, 2007

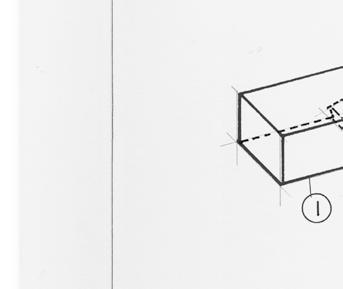

Paper, cardboard, wood construction

Dimensions: 140 × 130 × 123 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Atlántida (Atlantis). Project for a Science Museum for Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant, 2001–02

Néstor Basterretxea

Paper and cardboard construction

Museum of Contemporary Art of the Basque Country, Artium Museoa, Vitoria-Gasteiz

Banner. Printing on canvas

Measurements: 80 × 75 × 4 cm (collected)

Invited by consonni, a center for contemporary artistic practices, Ibon Aranberri’s project focused on the urban space of Bilbao, attuned to the work of other artists who had participated in this initiative since its launch in 1996. The period he was researching coincided with the changes associated with the 1997 opening of the Guggenheim Museum that substantially transformed ways of living in and understanding the city. The proposal involved revisiting the archetype of the contemporary city, taking the anachronistic setting of the Lemoniz nuclear power plant as a line of flight.

Located on the coast of Bizkaia, twenty kilometers as the crow flies from the city center, the nuclear power plant—which was never switched on—forms part of the industrial and social landscape that transformed the region in the second half of the twentieth century. Its construction—in line with a developmentalist economic model committed to industrial growth, increasingly dependent on energy supply—sparked strong opposition, giving rise to a social and cultural movement against the nuclear plan and in favor of protecting the environment and the identity of the region. In addition, the actions of ETA, with a campaign of harassment and deadly attacks against the plant, and the start of the transition period strengthened the political decision to declare a moratorium on the proposed nuclear projects. The plan came to a standstill in 1984, but the infrastructure—neglected and half-forgotten on the map— maintained a palpable emotional and symbolic weight.

The year 2000 came at a time of relaxation and optimism that seemed to offer the right conditions for revisiting this scenario with a certain critical distance.

It also offered the opportunity to implement elements of collective analysis and social participation. In this spirit, the idea was to revisit the physical site of the power plant as well as the enduring imaginary associated with it, through present-day points of view and forms of mediation such as drawing figurative maps, moving bodies in response to past events, a fireworks choreography designed for the site, visual reinterpretations of the iconography of the past, and graphic documentation (both reissued and specifically generated).

Three years after the official opening of the Guggenheim, the juxtaposition of the site, the industrial ruin, and the social mass was intended—the artist said—as a form of reparation and learning that drew on complex and traumatic elements. The proposal was suspended due to certain circumstances, but over time the images that had been created and the archives that had emerged during the process took on a meaning of their own. After several attempts, a projection of eighty slides in the form of a dynamic loop was completed. Thus, this visual narrative is presented in a different order each time.

Near the projection in the exhibition space, there is a heap of T-shirts originally intended to be offered to visitors. They had been stored in boxes without ever being used. They altered and combined commercial iconographies and graphics from the social opposition movement, emulating the concentration of a social mass in the open landscape that, once it ceased, never came to pass.

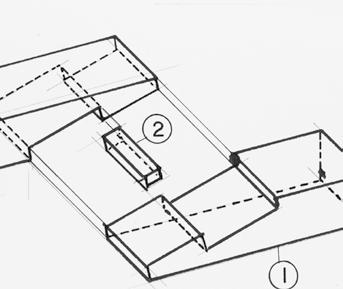

The content and appearance of this installation has been modified the few times it has been shown in public. It has also taken on a different title with each new staging, in a progressive revision of its narrative. On this occasion it is temporarily accompanied by three borrowed scale models, produced by different people, that propose interpretations and future uses of the Lemoniz nuclear power plant. They represent projects for the recovery and reuse of the infrastructure, which from to time to time are proposed but fail to crystallize. The models of these three projects have been sculpturally modified by Ibon Aranberri in various ways with the use of successive layers and additional perspectives.

Carmen Abad Ibáñez de Matauco, 1998

These models are part of the 1998 final course project “Project to Turn the Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant and the Affected Lands into a Space for Public Use,” as a basis for the development of a heritage park. Given that the models accompanied the development process, they are essentially working models. The project consists of two phases: Selective Destruction and Transformation. Models 3 and 4 can be dismantled to show the evolution of the building in the two phases of the project.

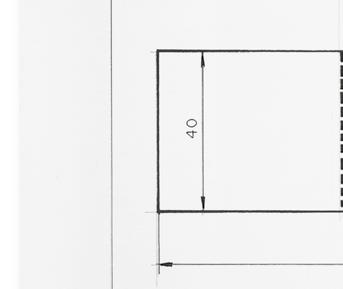

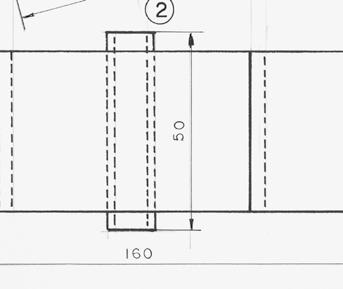

Working MODEL 1

Setting of the site on the coastal strip between Armintza and Bakio

Scale: 1:10,000. Dimensions: 70 × 37 × 10 cm

Materials: cork, cardboard, wood

Made by Carmen and José Luis Abad

Working MODEL 3 (dismountable)

Main building: when fully assembled, the model represents the site in its current state. The removal of the pieces simulates the destruction, which is the first phase of the project. The model then becomes the ruins of the building, forming part of the landscape. On these ruins, the second phase of the project is carried out: the transformation of the administration building into a square, of the control building into a bridge building, of the north and south units into centrifugal containment and centripetal containment buildings, of the auxiliary buildings into labyrinths, of the turbine building into a sea island, etc.

Scale: 1:800. Dimensions: 62 × 45 × 15 cm

Materials: cork, cardboard, balsa wood, card stock

Made by Carmen Abad

Working MODEL 2

Location of the site turned into a park and of the platform, which is the location of the Main Building, turned into a garden

Scale: 1:2,000. Dimensions: 86 × 72 × 15 cm

Materials: cork, cardboard, wood

Made by Carmen and José Luis Abad

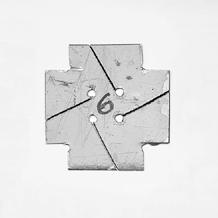

Working MODEL 4 (dismountable)

South containment building: when fully assembled, the model represents the site in its current state. The removal of the pieces simulates selective destruction, which is the first phase of the project (4 pieces). The second phase of the project is its transformation into a centripetal containment building.

Scale: 1:250. Dimensions: 26 × 26 × 36 cm

Materials: wood pulp, recycled packaging, balsa wood

Made by Carmen and José Luis Abad

Working MODEL 5

Section of the three walls of the southern part of the control building turned into the bridge building

Scale: 1:250. Dimensions: 20 × 6 × 6 cm

Materials: balsa wood

Made by Carmen Abad

Working MODEL 6

Section of the north auxiliary building turned into a labyrinth

Scale: 1:100. Dimensions: 46 × 33 × 12 cm

Materials: balsa wood, wire mesh, paper

Made by Carmen Abad

Paper, cardboard, and wood construction

Dimensions: 129 × 122 × 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

This model, not created by anyone in particular, is a scaled-down representation of the nuclear power plant site as it would have looked once the work was completed, in the late 1970s. Interpreted in general terms based on existing models and plans, it shows the external appearance of the completed infrastructure, located in the bay that had previously been filled by earthworks.

Over time, the industrial components of the power plant have degraded, some elements have been dismantled, and plant life has taken over the open spaces. Despite occasional media announcements about new projects and various interests, the reality of the existing scene still prevails, as a trace of its own past. The materiality of the ruin persists in time, as a surface on which speculations are marked out.

The nuclear power plant site, unoccupied for decades, has generated its own image. In this sense, it has consolidated itself as a possible setting that reveals its memory and determines future hypotheses. The blue plexiglass casing placed upside down over the model posits a reversible alternative between the transparency and opacity of a saturated sky, generating a dual effect, part idyllic nature and part dystopian fiction.

Atlántida (Atlantis): Project for a Science Museum for the Lemoniz Nuclear Power Plant, 2001–02

Néstor Basterretxea

Paper and cardboard construction

Dimensions: 172 × 74 × 44 cm

Museum of Contemporary Art of the Basque Country, Artium Museoa, Vitoria-Gasteiz

This model, created as a promotional image by Basque artist Néstor Basterretxea, was the first materialization of the project commissioned by the provincial council in collaboration with the university.

The Atlántida project proposed turning the structure of the nuclear power plant into a thematic park, and implementing it as a city of energy, science, technology, and the environment. The design was expressed in sketches first, and then in geometric volumes showing the architecture transformed into a sculptural concept. An enclosure was to cover the entire nuclear power plant structure, with a façade of approximately 54,000 m2 of white stone, glass, and stainless steel.

According to the proposed plan, Ciudad de Atlántida (City of Atlantis) would revolve around the emblematic building, with energy as the unifying thread and the nuclear power plant as the main element, and with a science and technology museum, an educational and training center, a theme and leisure park, astronomy and hospitality, a science park, a business incubator, an environmental center and space set aside for energy generation.

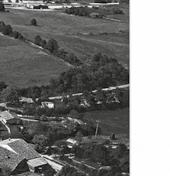

Mirando a Madrid desde la distancia (Looking at Madrid from a Distance), 2000–2024

72 framed 35mm slides, on a light box

This slide captures the moment of an improvised journey to the outskirts of Madrid, in response to an invitation to present projects in the context of the city’s public space.

The image reproduced here shows the artist in the shade of several trees, looking at the horizon through binoculars. Based on the direction he is facing, we deduce that he can see the city skyline in the distance. This movement can be interpreted as taking up a particular position in relation to the city. The fact that he is on the outskirts and looking from a distance suggests an ambivalent relation with the metropolis, perhaps as a result of misapprehensions and conflicting emotions.

The fragile slide—which has survived as one of a few existing images—has been stabilized and reproduced in order to update it as a pretext seeking to change its nature, shedding its original status as document.

The seventy-two copies of the same slide cover the surface of a light box, recreated here in its new role as a lamp that stands out in the exhibition. The light box, with the slides mounted on its external surface, generates an abstracted scene that becomes a focus within the museum space. The material fragility of these images—which will gradually fade as a result of prolonged contact with the light of the box—is in line with the transience of an action barely represented in time.

Over the course of several decades, the city’s inexorable sprawl swallowed up the site where the photograph was taken, and today it is no longer possible to identify the actual place.

Protopaisaje (Protolandscape, working title), 2003

Five analog photographs, b/w, gelatin silver prints on baryta paper Dimensions: 73 × 94 cm (each)

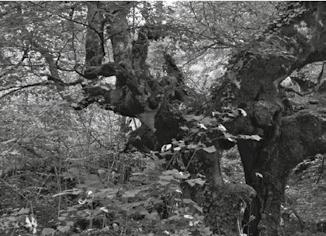

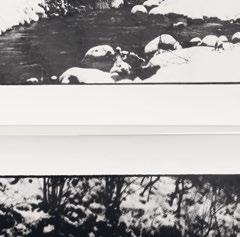

Photographs taken with no specific purpose by artist Ignacio Sáez while exploring inside the prehistoric cave. A printed map was handed out in advance, with the notice and instructions for walking to the site. The blanket of snow that had fallen the day before changed the perception of the landscape, causing participants to pay notable attention to the surrounding nature. The black-and-white photographs capture a timeless, almost archaic scene, in which the dark figures against the white backdrop mimic the chiaroscuro of the vegetation, the rocky hollow, and the stream flowing past it. The negatives taken on that excursion have been enlarged for the first time, and the views have been placed in a vertical sequence on the walls of the museum.

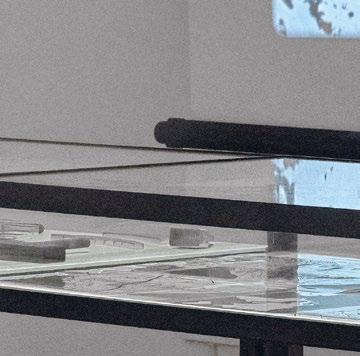

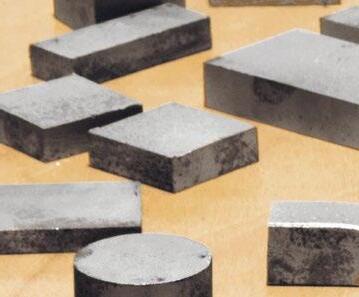

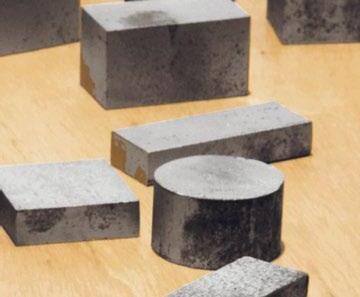

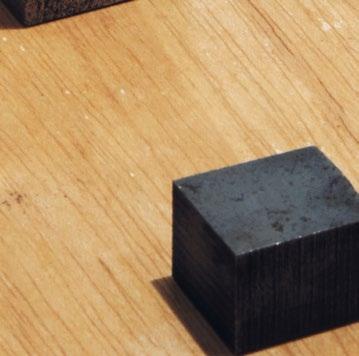

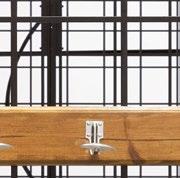

Cataphoresis-treated steel, galvanized steel, and wood

21 modules (11 units of 100 × 175 × 5 cm, 10 units of variable sizes)

4 galvanized steel beams:

10 × 610.5 × 10 cm

10 × 597 × 10 cm

10 × 500 × 10 cm

10 × 296 × 10 cm

26 wooden slats: 3 × 104 × 9 cm (each)

34 wooden blocks: 3 × 9 × 9 cm (each)

Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao. Acquired in 2019

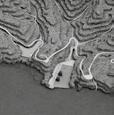

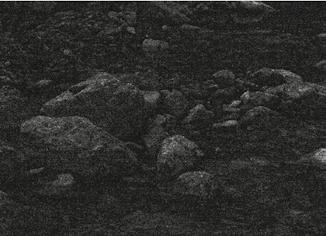

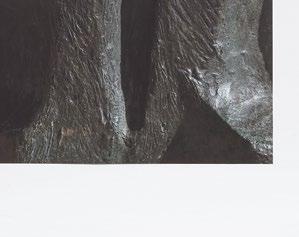

The metal sheets stand out against the granite floor. They are spaced apart and scattered over the surface of the exhibition hall. In a previous version they were stacked together in two blocks, arranged as they would be for commercial supply.

Some of the elements (half) are whole rectangular modules of the same size. Others have one or two irregular sides, with the metal surface outlining the relief of the rock—a different pattern in each case. One of the whole modules has a circular opening in the center, its diameter spanning almost the entire width of the surface. In another, integrated hinges and a lock protrude from the inside. All the modules in the room rest on wooden slats and rectangularsection blocks that lift them slightly off the floor.

Some parts show the wear and tear of the passing of time, with rusty corners and slight distortions of the surface. The matte, opaque black is covered by a whitish layer, which results from the lime deposits caused by rainwater running down the surface after falling through the limestone of the promontory where the cave is located.

There are also four square-section galvanized beams of different lengths, placed parallel to each other. Their ends are cut and capped at different angles, according to the slant of the rock at the point of contact, with a groove in which to embed the nuts of the eight threaded rods inserted into the walls, which held up the whole assemblage.

These modules and beams formed part of the structure that sealed the entrance of a prehistoric cave for almost two decades. The closing structure was dismantled when circumstances changed over time, returning the cave to its original state.

There is no rational explanation for the action of closing a cave. It was the consequence of an inner search, when the artist had temporarily distanced himself from the city where he had made his previous works. The rapid transformation of cities in the postindustrial era seemed to open up opportunities to expand artistic projects. However, the limitation of these aspirations soon became clear, with the tendency for ideas to be subjected to consensus and faced with the regulated and increasingly restrictive uses of public space.

…

The determination to probe, measure, and physically disrupt the status of the caves can be understood as an attempt to find a counterpoint to technical and social codes in the natural environment. After studying the various existing regulations and taking advantage of bureaucratic gaps, the closure of the cave was negotiated with the authorities. As a result, one of the caves that had been explored was made inaccessible. It was closed off to humans without obstructing the habitat inside. At the same time, the terrain could not be altered due to the heritage value of the subsoil. These parameters determined the technical aspects of the structure closing off the entrance. The blackened steel surface separated the inside from outside, connecting them by means of a hole cut into the sheet, allowing bats to fly in and out. A margin around the perimeter ensured temperature and humidity levels remained the same.

Almost two decades after that action, and contrary to the original discourse, the entire structure that sealed the cave was removed, returning it to its original state. The dismantled materials were gathered up for display in disassembled form. The result has been exhibited in various settings, uncoupled from its original function. The title and the time of this work pertain to that second action. It is displayed in the museum gallery without references that could help us understand its intra-history.

The original process of closing off a prehistoric cave also generated other images, some of which can be found in this exhibition (drawings of sleeping bats, a video recorded inside the sealed cave before returning it to its original state, a series of photographs taken by artist Ignacio Sáez on an excursion through the snow to the interior of the cave days before it was closed off, etc.).

Graphite pencil on paper

21 drawings

Dimensions: 210 × 297 mm (each)

The dark mass of the sleeping bat reveals a vague shape, different each time. It is like a body with no fixed anatomy; it could be a solid extension of the rock supporting it.

These drawings were made as automatic memory sketches after visiting the interior of numerous caves—which are abundant in the region—following the information on the archaeological maps. The expedition was carried out in the old-fashioned way, with the artist in the role of solitary naturalist, deliberately dispensing with means of representation. No photographic cameras or image-capturing devices were used, ensuring at every turn a purely contemplative journey.

The pencil lines with no clearly defined style are now a retrospective trace of an unrecorded gaze. So we could also read the sleeping bodies of the bats as a small extrapolation of the rocky formation of the interior of the caves.

Some time later, one of the caves explored during this expedition was, after obtaining the necessary permits, deliberately closed off. Years later, the materials used for this action were removed and used to create Zulo beltzen geometria (Geometry of the Black Holes, 2019), the work that shares the space with the drawings in the museum gallery. Spatially attached to one of the corners of the room, the drawings are shown together as a group for the first time: a personal testimony of that transformative quest.

S/T (Detour), 2011

Diameter 185 cm

Mar del Pirineo (Sea of the Pyrenees), 2006

Media: polyester resin and fiberglass

Dimensions: 6 modules, 244 × 122 × 35 cm (each)

Additional elements: photographic prints, log sections, etc. Colección Fundación Valentín de Madariaga y Oya-MP

This work is a three-dimensional scale model of the actual cartography of a valley transformed by the construction of water infrastructure. Its title seems to evoke a strange, fictional place—it sounds like the abstraction of a dual environment that can be both sea and mountain, blue and green. It is a reference to an actual existing site: a recreational complex built around the infrastructure that over time has lost its appeal.

Accurately reproducing the orography of the flooded valley, the six contiguous modules form the unreal place as negative space. The smooth surface of the water looks like a prairie plateau and the hills that rise in the surrounding area become dolines and hollows, like upside-down geographic features.

The synthetic neutral gray material standardizes the orographic variations. The irregularity perceived from the outside suggests a place reminiscent of an anthropological void—an imagined representation based on a model displayed on the wall as if it were a sculptural frieze. The gaps between the modules interrupt the continuity of the abstracted landscape, generating a repeated, specific progression in each case.

For his solo exhibition at Parra & Romero gallery in Madrid in 2014, New York artist Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021) prepared a new statement. In keeping with his line of work, he was to graphically adapt the statement to the physical characteristics of the gallery, seeking a precise relationship in his distinctive typeface and using a vector design.

Because of his interest in linguistics, for this adaptation Lawrence Weiner decided to work with the official languages of the Spanish state, expanding the initial idea and de-hierarchizing it in order to collaborate with artists with cultural ties to those languages and a certain affinity with the methods of conceptual art. These artists were Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, working with Spanish, Antoni Muntadas with Catalan, David Lamelas with Galician, and Ibon Aranberri with Basque. Avoiding a purely literal translation of the proposed statement, each artist was asked to appropriate its polysemy and interpret its meaning in accordance with the use of words in Weiner’s practice.

The initial idea was to reproduce Lawrence Weiner’s statement PLACED SOMEPLACE WITH INTENT along with the adaptation in each of the four official languages in four versions, displaying them on each of the four walls of the gallery. The words of the English statement paired with each adaptation were graphically framed with borders the same width as the typeface. Their overlapping right angles intertwined, creating gaps and intersections. Ibon Aranberri formulated the Basque version as ASMOZ NONBAIT JARRIA

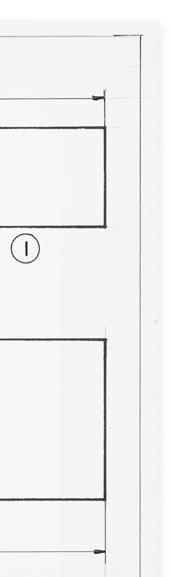

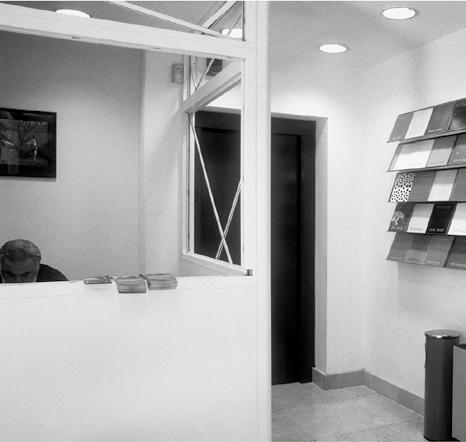

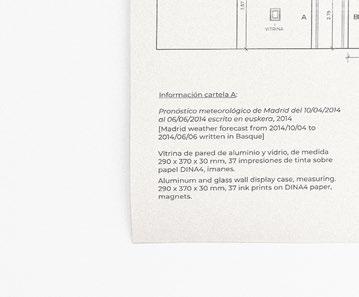

In the second part, during the exhibition, each artist added a new formalization, maintaining the idiomatic link through a text-object. Among Basque uses, which are often subject to symbolic prejudice, meteorology seemed to offer an apparently neutral field. An external lockable bulletin board fixed to the wall displayed the daily weather forecast for Madrid. First thing every morning, the glass case was unlocked and the new day’s updated forecast received by email was placed inside. Each new printed A4 sheet covered the previous ones, and was held in place by two magnets pressing against the metal base. They continued to overlap in successive layers until the last day of the exhibition.

The written weather forecasts were based on the variables used by meteorological bureaus, and sought to maintain a plausible expression. The descriptions were open to a contingent reading, given that they were written and presented without translation in a language unintelligible to most citizens of Madrid. At a time when meteorological reporting tends toward recognizable visual codes, this formulation suggested an anachronistic narrative, which today’s means would lead us to describe as perhaps more poetic than scientific writing.

In this exhibition, the two elements of Aranberri’s contribution to Lawrence Weiner’s work have been brought together again, removed from their original context. As such, they have been added to the list of works in the exhibition at the museum, with their own title and technical specifications. On the one hand, Placed Someplace with Intent / Asmoz nonbait jarria is listed as a work consisting of cut vinyl wall lettering, reproduced from the recovered file, and attributed to Lawrence Weiner. On the other, Pronóstico meteorológico de Madrid del 10/04/2014 al 06/06/2014 escrito en euskera (Madrid Weather Forecast from 4/10/2014 to 6/6/2014 Written in Basque) is listed as a lockable bulletin board containing all the forecasts, and attributed to Ibon Aranberri.

However, both elements—the glass bulletin board with the sheets of paper and the rolled-up vinyl lettering—have been placed on a shelf, away from the wall of the corridor where they were to have been displayed. Legal issues concerning ownership following the death of Lawrence Weiner and the museum’s code of ethics regarding the global geopolitical situation during the exhibition were a deterrent to the lettering and the bulletin board being displayed together, as intended. Thus, the wall remains empty, with the museum lighting maintained as planned. A sheet of paper with a draft of the text for the wall label, provisionally stuck to the wall with some masking tape, is the only reference to the idea.

Información cartela A:

Pronóstico meteorológico de Madrid del 10/04/2014 al 06/06/2014 escrito en euskera, 2014 (Madrid Weather Forecast f rom 4 4/10/2014 to 6/6/2014 Written in Basque)

Vitrina de pared de aluminio y vidrio, de medida 29 × 37 × 3 c cm, 37 impresiones de tinta sobre papel DINA4, imanes.

Aluminum and glass wall display case, measuring. 29 × 37 × 3 c cm, 37 ink prints on DINA4 paper, magnets.

PARED 1.4.4.

Información cartela B:

PLACED SOMEPLACE WITH INTENT / ASMOZ NONBAIT JARRIA, 2014

Vinilo de corte

304 × 53 cm

Cut vinyl

304 × 53 cm

Lawrence Weiner en colaboración con Ibon Aranberri

Lawrence Weiner in collaboration with Ibon Aranberri

Apirilak10,osteguna

EGURALDIALDAKORRA

Lainotsuhasikodaeguna,erdietagoimailakohodeienmenpe.Ostarteakagertzekojoerahar lezakeeguerdialdera.Arratsaldeanordeahodeiaknagusitukodiraerabat,etalitekeena tartekaekaitzedotabanakakozaparradakbotatzea. Hego-ekialdekohaizea,5eta10km/oabiaduraz. Maximoak,27ºC.

Apirilak11,ostirala

EURIZAPARRADAKMENDEBALDETIK

Lainoetaostarteaktxandakatukodiragoizeanzehar.Arratsaldean,erdimailakoeta goi-hodeiakagertukodira,batezeremendialdean,tartetakoeuriaetaekaitza erakarriz.Giroaldakorragainontzean:lainoakugalduzhego-ekialdetik, noizbehinkakoeurijasakeragingodituhan-hemenka. Horrelaeutsikodiogauparteanere.

Tenperaturakbeheraegingodu,bainaezdaaskoigarriko.25ºcinguruan.

Apirilak12,igandea

Zaparradakarratsaldeanetaekaitzukitua

Asteburuarenhaseraipar-haizearenetorreraktenperaturarenhozteaekarrikodu, nahizetaorokorreanerkidegoarengehienean20ºCgainetikobatazbestekoaniraun. Erdietagoi-mailakohodeiekinargitukoduegunak.Ostarteknabarenduzjoangodira goizeanzehar.Arratsaldeanordeahodeitzarraknagusituzjoangodiraetaargiuneak urrituz,horrelaeuri-zaparradaetaekaitzarriskuaaldeguztietanemangodelarik. Mendialdeanbatezere.Gauparteanerejoeraberetsuakeutsikodio.

Apirilak13,igandea EgonkorragoErramuEgunean

IgandearekinbakeanabiatukodaAsteSantua.Goipresioatmosferikoeneraginez egonkortasunanagusitudaorokorrean.Euriarriskuakuxatuta,hodeimaila aldakorrekoegunaizangodugugaurkoa.Lainotzeetaargialdiakbateraibilikodira goizeanzehar.Eguerdialderakoargiuneakpixkanakaugalduzikusikoditugu. Goizekotankeraberetsuanigarokodaarratsaldean,hodeimailaaldakorrean.Antzeko joeran,gauparteanerehodeietaostarteaktxandakatuzjoangodira.

Epeltzeraegingodugutxienekotenperaturak,erabereanmaximoakeregoraegingo du.25ºCinguruanibilikodahiriburuan.

Apirilak22,asteartea

Eguzkiaageriagoyetaepeltzejoera

Atzokoabainoegonkorragoigarokodaeguna,Atlantikotikzeharkadatorrendepresio fronteberriarenesperoan.Edonolaereestalitasegikoduzeruak,noizbehinkakoeurilardatsarenmehatxuan.Mendialdeanbehetikibilikodalainoa,girobustianeguerdi bitartean.Arratsaldeakereeuriaekarlezake,ahulaetatartekakoagertatuarren. Lainoarenondoriozgutxienekotenperatutakfreskoibilikodira,maximoakaldizgora egingodu,21º/22ºCiristeraino.Hego-ekialdetikjokoduhaizeaktartekabolada zakarrakharrotuz.

Apirilak23,asteazkena, Eurigiroamendialdean

Barealdiarenondotik,aldakorjoangodaasteazkena.Ipar-mendebaldetiksartuzaigun fronteakeurigiroaekarridiguorokorrean,han-hemenka.Horrela,goizeanzehar hodeietaargiuneaktartekatukobadiraere,arratsaldeakbustitzeraegingodu, pixkanakazaparradakugalduz.Mendialdeanbotakodusarriago,gainontzeko eremuetanhodeietaostarteekberehorretaniraundezakete.

Tenperaturadidagokionez,aldaketahandirikez,beherakojoeran,7ºCeta19ºC bitartean.Hego-mendebaldetikjokoduhaizeak,18km/oabiaduraz,tarteka astinaldiakeraginez.

Apirilak24,asteazkena

Euriasarrietaekaitzatarteka

Atlantiarfronteakbatabestearenatzetikdatoz,etabeteanharrapatukogaituztegaur, eguraldiarenokertzeaeraginez.Aldakoragerikodazerua,ostarterenbathaseran, bainageroetalainotuagoetaeuritsu.Ondoriozekaitzaereigarrikoda,mendialdean batezere.Gainontzean,etaegunosoanzehareurizaparradakbotakoditu,arratsaldez batikbat.Mendebaldekohaizeakhozkirriaetagirozakarradakartza,udaberriaren gozoauxatuz.Termometroakbeheraegingoduarinki,9ºCeta15ºCbitarteanibiliko delarik.

Apirilak25,ostirala

Eguzkia,etalainorenbat

Fronteareneraginaapaldudelarikegonkorabiatukodaegunagaur,aspaldikopartez eguzkianagusituz,nahizetahodeizirriakgerturatunoizbehinka,hanetahemen zeruazurituz.Arratsaldeakereoskarbieutsikodioetaederkijokodueguzkiak. Epelduezinikdabiltenperatura,gorena18ºCinguruanibilikoda,hotzenakbehera egingoduelarik.Haizeakipar-mendebaldetikjokodu,apal.

Apirilak26,larunbata Lainoaldietazaparrada

Joaldiaezdabaretzen,izanereerasoberribatsartukozaiguatlantikoitsasotik, arratsaldetikaurrera.Zeruagoibelduzjoangodaeguneanzehar,euritantaeta zaparradazekarrikorduakigarohala.Txartzeamendialdeannabaritukodagehiago. Eguerdialdeanaterieutsikodiohalaere.Gainontzeanhodeietaostarteak txandakatukodira,eurilardatsaeraginezhan-hemenka,hiriareniparparteanbatez ere.Horrela,hego-mendebaldekohaizeaidartuzjoangodaeguneanzehar. Tenperaturaksamurtuzdoa,pittinka,20ºCinguruankokatuzgaurkorako,hotzena ordeaezda9ºC-tikpasako.

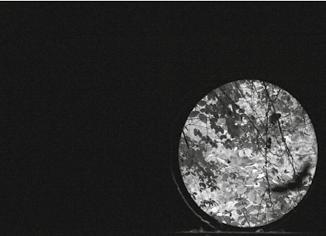

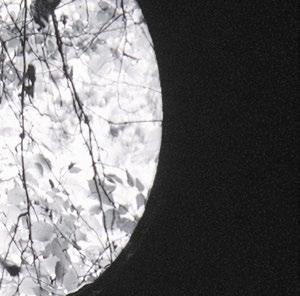

Single-channel digital video projection, 13 min.

In the images filmed in the dark interior of the cave at dusk and dawn, there is a hole in a flat black surface. Due to the contrast with the light outside, it resembles a vision of a full moon. When the camera lens is focused on the background of the scene, the branches of the trees outside can be seen, moving in the wind.

Every now and then, the erratic flight of bats is silhouetted against the light, entering and leaving in the semidarkness through the hole cut from the opaque surface. When the movement stops and the camera lens is pointed at the emptiness of the hole, it tends to lose focus due to the bats flying in and out, confusing the autofocus sensor.

Previously, the panning of the camera had captured in chiaroscuro the uneven surfaces inside the cave, revealing markings, inscriptions, and graffiti. Several views of the exterior complete the sequence. The flowing stream was filmed at dusk. It is probably where the rainwater seepage ends up after percolating through the limestone. At the beginning of the video, the image of an ancient leafy tree dominates the scene in the dim light. The camera zooms in and frames the hollowed-out trunk, which can be seen through. Throughout the video, the intermittent sound of drops of water can be heard hitting the puddle on the floor of the cave—created by the erosion caused by the water itself—which at a certain point merges with the sound of the stream.

The video has been edited as a series of shots filmed outside and inside the closed-off cave. Years later, the structure that had blocked the entrance to the cave for almost two decades was dismantled, and the site was returned to its natural state prior to the closure. It is present in several of the works in the exhibition.

Two prints on canvas

Dimensions: 121 × 78.5 cm (each)

98 framed photographs

49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm; 49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm; 49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm: 49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm; 48.5 × 60 × 3 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm; 44 × 63 × 4 cm; 49.5 × 61.5 × 3 cm; 62 × 76 × 3.5 cm; 68 × 70 × 3 cm; 58 × 87 × 3.5 cm; 67.5 × 79 × 2 cm; 66 × 82 × 4 cm; 60 × 90.5 × 3.5 cm; 63 × 83 × 4.5 cm; 71 × 85 × 3.5 cm; 80.5 × 80.5 × 2.5 cm; 76 × 90 × 2 cm; 73 × 87.5 × 4 cm; 73 × 92.5 × 3.5 cm; 78 × 97.5 × 3 cm; 95 × 78 × 4 cm; 82.5 × 98 × 4 cm; 98 × 98 × 3.5 cm; 92 × 102.5 × 4.5 cm; 84 × 103.5 × 4.5 cm; 87 × 111 × 4 cm; 93 × 111 × 3.5 cm; 105 × 126.5 × 2 cm; 107 × 132.5 ×× 4 cm; 57 × 67 × 4 cm; 57 × 67 × 4 cm; 51.5 × 64 × 4 cm; 104 × 132.5 × 4 cm; 104 × 128 × 4.5 cm; 103 × 128 × 4.5 cm; 105 × 126.6 × 2 cm; 107.5 × 128 × 4 cm; 110 × 132.5 × 3 cm; 107.5 × 127.5 × 4 cm; 106 × 133 × 3 cm; 104 × 134.5 × 4 cm; 113 × 133 × 4.5 cm; 64 × 75 × 2 cm; 88 × 113 × 2.5 cm; 93 × 125.5 × 3.5 cm; 128 × 107.5 × 4 cm; 105.5 × 127 × 2 cm; 85.5 × 103.5 × 3 cm; 88 × 133 × 3.5 cm; 105 × 126.5 × 2 cm; 101.5 × 123.5 × 3 cm; 108.5 × 123 × 5 cm; 106 × 135 × 4.5 cm; 92 × 127 × 5 cm; 103 × 122 × 6 cm; 108.5 × 131 × 3.5 cm; 115 × 132 × 3.5 cm; 113 × 133 × 4.5 cm; 93 × 147 × 4.5 cm; 93 × 147 × 3 cm; 115 × 150 × 2 cm; 120 × 152 × 3.5 cm; 53 × 186 × 4 cm; 149 × 181 × 3 cm; 149 × 181 × 3 cm; 149 × 181 × 3 cm; 149 × 181 × 3 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 4.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 97.5 × 115.5 × 3.5 cm; 135.5 × 164.5 × 3 cm; 140.5 × 172 × 3 cm; 100 × 140 × 2 cm; 125 × 153.5 × 3.5 cm; 120.5 × 164.5 × 3 cm; 121 × 180 × 5 cm; 123 × 147 × 3 cm; 135.5 × 165.5 × 3 cm; 93 × 147 × 4.5 cm; 116 × 140 × 3.5 cm; 93 × 147 × 4.5 cm; 93 × 147 × 4.5 cm; 135 × 195 × 4 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 140 × 197.5 × 3 cm; 140 × 197.5 × 3 cm; 135 × 195 × 4 cm; 150.5 × 183 × 3.5 cm; 140 × 180.5 × 5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 2.5 cm; 149 × 181 × 4.5 cm

Chromogenic print on photographic paper

Museo Reina Sofía

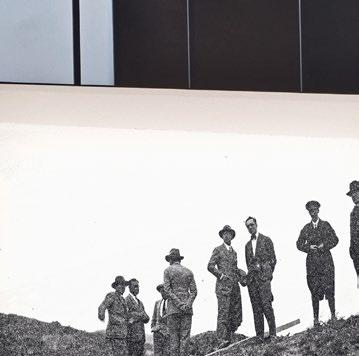

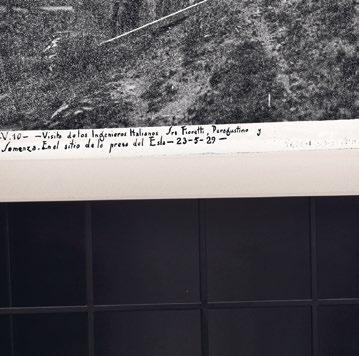

Through a boundless strategy of accumulation, Política hidráulica brings together almost a hundred photographs of dams and reservoirs dotted throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The emphasis on aerial views and certain framings lends a sculptural dimension to the engineering projects in the installation, embodying a factual archive that is almost unreal.

The accumulated images not only show how large infrastructures and industrialization processes definitively shaped the landscape—and our way of looking at it—but also draw attention to their role as mechanisms of appropriation and control. Thus, Política hidráulica springs from an approach that questions landscape representations as a space immune from connotation.

This series begins with an exploration of the first reservoir, which was still under construction at the time the photographs were taken. As part of the twentieth-century hydrological plan it is quite recent, and its construction gave rise to strong protests. The effects on the landscape and the anthropological effects were photographed first and foremost for documentary purposes. The camera captured the social context and actions opposing the huge infrastructure that would extinguish life in the area.

The realism of the images obtained was in line with this day-to-day space, and discouraged media coverage. However, this was the link that prompted the artist to look for the contrasting bird’s-eye view, and to approach the erasure of the place from the distance typical of images of power. As such, the photographers flew over the territory, adopting the perspective of corporate reportage.

These first photographs attempted to replicate the process used by specialists. Rather than turning to existing snapshots (from offices, etc.), there was an attempt to recreate the actual reality, using the codes of the period in which the discipline had a mission. A learning process was involved in following the technique of similar photographic reports. But the results of this approach revealed the problems involved in constructing images, insofar as the technology and ways of looking have changed over time.

For this reason, professionals were commissioned to take the photographs in Política hidráulica. Interpreting earlier instructions, they flew over each site, taking off from the nearest airfield. A methodology was thus established and the series was completed in several actions, over several years, shaping the historical sequence in reverse time.

This series of photographs is not intended to cover an entire geographical area, but rather follows the layout of the systems that have shaped resource extraction and distribution processes over the last century. The infrastructures, which are usually located in remote and unpopulated areas, produced the energy that was transmitted through power lines to the more industrialized regions, under the control of corporations.

1 sculpture-panel, made as an exhibition device for documenta 12, subsequently unused.

Dimensions: 204 × 365 × 18 cm

1 portable projection screen, adaptable. Dimensions: 200 × 200 × 25 cm

21 metal and wooden benches (7 Red: RAL-1018, 7 Green: RAL-3020, 7 Yellow: RAL-6037), based on a standard model Dimensions: 44 × 175 × 28 cm (each)

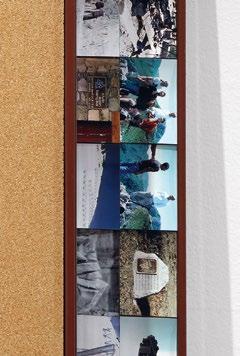

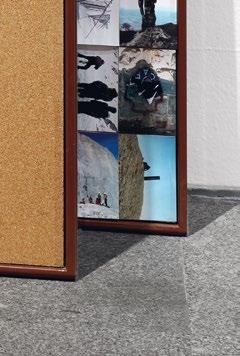

18 cork panels with enameled metal framing.

Dimensions: 189 × 103 × 3.5 cm (each). *1 of these cork panels displays a set of 120 photographs: 10 × 15 cm (each), obtained during pre-shoot preparation

6 metal and glass display cabinets: 98 × 123 × 75 cm (each)

Contents of the display cabinets:

2 metal ice axe-sculptures, with anchor bolts, based on a missing model.

Dimensions: 30.5 × 68 × 5.7 cm (each)

Metal parts, ice axe components

1 color print showing a rock base for the ice axe-sculpture.

Dimensions: 56 × 39 cm

127 b/w photocopies, with graphics including maps used.

Dimensions: 21 × 29.7 cm (each)

222 slides taken by a photographer during the shoots

42 b/w prints on acetate, with graphics including the film’s credits

Dimensions: 42 × 30 cm (each)

8 b/w photographs, gelatin silver prints on baryta paper mounted on foam board. They are views of the scenery from the film, modified with red marker.

Dimensions: 90 × 113.2 × 1 cm (each)

16mm film, color, no sound, 18 min.

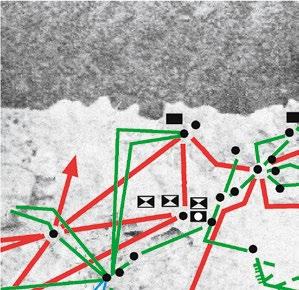

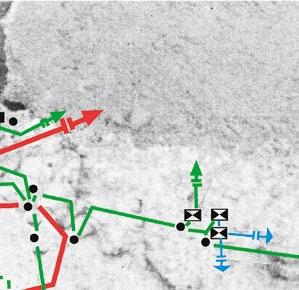

The 16mm film projection consists of an accumulation of footage from a series of film exercises carried out as part of a learning process. The pretext for these tests was an attempt to make a mountain film—a goal that is inherently unattainable due to the impossibility of establishing a language structure that defines such a category.

In earlier works, the representations and journeys in the natural environment were mediated by physical elements or time frames that helped to sustain the narrative. In this case, as a separate result, the idea was to generate a brief situation—a particular relationship with the landscape—by approaching the image through common formal strategies easily identified in the archives consulted.

The young mountaineers repeatedly tried to take up the film camera to capture a series of movements and actions, with the aim of making a mountain film. The result of these exercises became the film itself, which is projected in a randomly edited loop.

Using the narrative strategies, topics, and tools that underpin this genre, images of high mountain landscapes and the movements that take place in them are projected. The projector showing the film on a loop is placed on a display cabinet—one of six arranged in a horizontal line in the exhibition room. The display cabinets contain acetates with possible credits for the film, maps, slides, and other materials relating to the process followed. A portable screen receives the projected images. Off to the side, another larger, heavier, and less flexible screen leans sideways against the wall. Several rows of stacked benches painted in three colors serve as seating for looking at the images in the room. On one side, a pile of corkboards suggests the possibility

…

of a room (such as a hiking club) in which these panels line the walls, as shown in the top panel on which photos can be seen. On top of one of the display cabinets there are eight black-and-white analog photographs mounted on cardboard, of a size similar to the width of the display cabinet. Lines drawn with a red marker show the movement followed on the film set.

All of this together makes up a multifaceted record of the languages used in representations of movement and action in rugged high country. The perspective of the fake epic style of twentieth-century film overlaps with the present-day vision of a group of young people walking up a glacier carrying old, heavy film cameras.

Untitled, 1996

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 212 × 212 × 51 cm

INJUVE Collection

Installation, 5 pieces:

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 280 × 45 × 45 cm

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 279 × 44 × 3.5 cm

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 186 × 44 × 3.5 cm

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 148 × 44 × 4 cm + 129 × 44 × 4 cm

Lacquered steel

Dimensions: 212 × 212 × 51 cm

Cavity, 2005

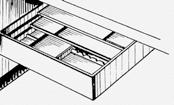

Tinted northern pine platform on empty 750 ml San Pellegrino glass bottles. Variable dimensions

Following the architectural geometry of the space, empty bottles of San Pellegrino mineral water turned on their side are arranged in continuous lines. The bottles can be angled to fit the dimensions of the available space.

The area filled by the bottles is covered by a wooden platform, in which the slats are “staggered” and placed crosswise to the direction of the bottles.

The platform, approximately ten centimeters smaller on each side than the surface occupied by the bottles, follows the shape of the walls and the edges of the filled space, revealing some of the glass bottles beneath.

The raised floor, which appears to float over the bottles, is stable and solid enough to allow people to walk on the wooden surface. Underneath there is a hollow space, reminiscent of a double floor. Looking down from above, the gaps left by the bottles can be seen, revealing the actual floor of the space.

Exhibited in:

1. Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, 2005

2. Several Ways Out, UKS (Unge Kunstneres Samfund / Young Artists’ Society), Oslo, April 21 – May 21, 2006

3. Partial View, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, December 29, 2023 – March 11, 2024

S/T (San Pellegrino), 2016

Firestone, 1997

Single-channel video, color, no sound, 15:44 min.

Bergé Collection

The black tire keeps rolling down, suggesting that something might have happened at the top of the hill. Sometimes it veers off course, passing over natural barriers and onto the road, but as it is a low-traffic area there is very little danger. Quite a lot of force is required to throw the tire so that it will roll in a linear direction. Depending on the inertia, it can reach high speeds and become difficult to control. Sometimes two tires moving at different speeds cross each other’s paths. The hardest part is the strenuous physical effort of carrying the tire back to the starting point for each throw. The repeated descents create a loop effect, which is then reinforced in postproduction. The people who were watching also captured the action in photos and videos.

Steel Forge, 106 × 64 × 150 cm

Legs, 106 × 64 × 50 cm

Sheet metal, 166 × 110 cm

Tube 1, 22 × 22 × 198.5 cm

Tube 2, 22 × 22 × 91.5 cm

Stitched and screen-printed fabric

Screen printing on T-shirts

Courtesy of the artist and Begoña Muñoz

Screen-printed T-shirts produced by the artist Begoña Muñoz for her solo exhibition basauri.nl, held at Casa Torre de Ariz museum in Basauri in 1998. Several of these T-shirts were included in the Ibon Aranberri exhibition that followed in the same space, overlapping with the works on display. The T-shirts have been issued again in collaboration with Begoña Muñoz. To recreate the original setup at Museo Reina Sofía, the T-shirts were incorporated into the sculpture Home & Country (2018), covering its base. The same T-shirts were presented as freestanding piles on the granite floor of the Artium Museoa exhibition room.

Dam Dreams, 2004

12 prints on paper

Dimensions: 29.7 × 21 cm (each)

S/T (Territoire) (Untitled [Territory]), 1997–2024

Screen-printed and folded cardboard

Edition for Museo Reina Sofía: 9 pcs.

Edition for Artium Museoa: 226 pcs.

Dimensions: 100 × 80 cm (each)

Transakzio denbora (The Timing of Transaction), 2003

Transakzio denbora: The Timing of Transaction was a closed-door meeting of artists and “parallel thinkers” from different geographical and professional backgrounds.

Following the closed-door discussions and after producing a post-meeting written statement, the thirty participants reflected on the role of the new aesthetic practices by establishing a new map of relationships between art and civil society. As well as participating in the discussions, several artists contributed ephemeral projects and interventions, creating forms of mediation and visual communication aimed at the public.

Donostia-San Sebastián, Palacio Miramar, 2003

Organized by Arteleku and consonni

S/T (Taula) (Untitled [Board]), 2003

30 laser-cut wooden boards. Rubber band, paper

This modified board in the shape of an oak leaf was handed out to participants as an instrument for personal use, without specific instructions. It was originally intended as a surface to support paper for taking notes during the meeting but soon found other uses, such as sampling cuisine. Later, the wooden board ended up having all kinds of domestic uses. This exhibition recovers several of those apparently spare boards with traces, erosion, and clear indications of the different uses they have been put to in the intervening time.

S/T (Retratos) (Untitled [Portraits]), 2003

Stencil portraits of the 30 participants drawn by José Antonio Iglesias Moreno “Blami” from photographs by Conny Beyreuther

These drawings were used on various graphic mediums that improvised their self-production and maintained a low-level visibility. A photomontage with beach views and the superimposed portraits of all participants was published in the media. For this exhibition, the portraits have been reprinted as stickers and pasted on a shelf in the museum in a chaotic way.

S/T (Blackout), 2003

Laser-cut lacquered steel: 5 pcs.

Dimensions:

91 × 67 cm (RAL 9005)

67 × 40 cm (RAL 6029)

96 × 69 cm (RAL 3020)

70 × 81 cm (RAL 1018)

73 × 69 cm (RAL 3020)

Untitled, 2005

107 analog color prints

Dimensions: 20 × 13 cm

Single edition

A shelf placed over the wall of the exhibition hall corridor holds a large number of photographs of surfaces of water. The photos were taken as a spontaneous record while visiting dams and reservoirs scattered through the land. Thus, this series is a kind of intimate counterpoint to the production of larger-scale images in the work Política hidráulica (Water Policy, 2004–10).

The almost monotonous images form a color chart of different shades of blue, each one slightly different from the others. There are very few indicators of place, beyond the flat expanse of water that fills each photograph. A more detailed color analysis shows that the dominant blue includes shades of brown, probably due to the effect of the clay soil deposited at the bottom of the bodies of water.

The photographs have been stacked in a pile, so that only the top image is visible. One surface is superimposed over the others, creating a continuous succession of layers.

Piedra e intersección (Stone and Intersection), 1994

Polyester resin and fiberglass

Dimensions: 64 × 40 × 43 cm

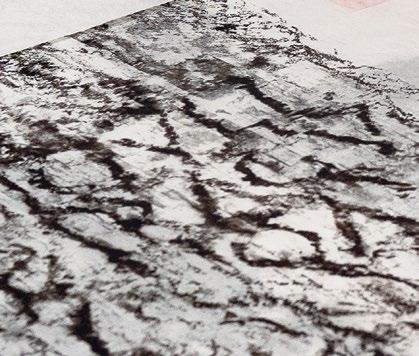

Charcoal, graphite, wax crayon, crayon, conté pencil, sanguine, India ink on tracing paper

Dimensions: 110 × 86 cm; 110 × 71 cm; 110 × 79 cm; 110 × 106 cm; 153 × 110 cm; 110 × 101 cm; 101 × 44 cm; 145 × 110 cm; 150 × 110 cm; 147 × 110 cm; 138 × 110 cm; 164 × 110 cm; 154 × 110 cm; 142 × 10 cm; 143 × 110 cm; 145 × 110 cm; 190 × 110 cm; 150 × 110 cm; 230 × 110 cm; 210 × 110 cm; 156 × 52 cm; 185 × 110 cm; 136 × 110 cm; 200 × 58 cm; 200 × 110 cm; 110 × 93 cm; 210 × 110 cm; 152 × 60 cm; 230 × 110 cm; 135 × 110 cm; 120 × 110 cm; 95 × 100 cm; 135 × 110 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 124 × 110 cm; 90 × 92 cm; 97 × 85 cm; 110 × 95 cm; 10 × 87 cm; 65 × 110 cm; 110 × 113 cm; 186 × 110 cm; 117 × 110 cm; 128 × 110 cm; 110 × 90 cm; 110 × 61 cm; 110 × 92 cm; 124 × 110 cm; 110 × 63 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 110 × 138 cm; 183 × 110 cm; 145 × 110 cm; 163 × 110 cm; 110 × 83 cm; 140 × 110 cm; 194 × 110 cm; 140 × 110 cm; 217 × 110 cm; 175 × 110 cm; 205 × 110 cm; 200 × 110 cm; 150 × 110 cm; 200 × 110 cm; 200 × 110 cm; 130 × 110 cm; 130 × 110 cm; 120 × 110 cm; 96 × 110 cm; 160 × 110 cm; 113 × 110 cm; 110 × 100 cm; 110 × 86 cm; 113 × 110 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 135 × 110 cm; 104 × 110 cm; 126 × 110 cm; 128 × 110 cm; 110 × 90 cm; 120 × 110 cm; 110 × 123 cm; 103 × 110 cm; 110 × 107 cm; 110 × 100 cm; 130 × 110 cm; 106 × 110 cm; 145 × 110 cm; 113 × 110 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 90 × 110 cm; 110 × 90 cm; 110 × 93 cm; 110 × 75 cm; 152 × 110 cm; 114 × 110 cm; 110 × 88 cm; 112 × 110 cm; 110 × 119 cm; 110 × 87,5 cm; 110 × 89 cm; 110 × 98 cm; 110 × 80 cm; 83 × 110 cm; 103 × 110 cm; 110 × 82 cm; 110 × 70 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 110 × 87,5 cm; 110 × 97 cm; 110 × 103 cm; 110 × 106 cm; 110 × 116 cm; 110 × 110 cm; 110 × 83 cm; 78 × 110 cm; 110 × 120 cm; 110 × 104 cm; 110 × 82 cm; 100 × 110 cm; 110 × 88 cm; 110 × 104 cm; 58 × 110 cm; 50 × 62 cm; 42 × 110 cm; 53 × 110 cm; 46 × 110 cm; 42 × 110 cm; 70 × 110 cm; 114 × 110 cm; 110 × 93 cm; 95 × 110 cm; 107 × 97 cm; 110 × 73 cm; 110 × 78 cm; 110 × 91 cm; 110 × 89 cm; 62 × 85 cm; 61 × 84 cm; 110 × 92 cm; 110 × 82 cm; 62 × 86 cm; 110 × 93 cm; 49 × 79 cm; 78 × 60 cm; 52 × 67 cm; 43 × 55 cm; 110 × 95 cm; 110 × 42 cm; 110 × 38 cm; 33 × 110 cm

Collection of San Telmo Museoa, Donostia-San Sebastián. Created as part of the Museo Bikoitza / Double Museum program

This installation, scaled to fit the room, is made up of numerous rubbings of tombstones on paper, made using the frottage technique.

Most of the tombstones traced have no special heritage or artistic status. They were carved centuries ago, as a marker of social distinction at burials on behalf of the new bourgeois class that emerged from the commercial boom in the local area, and thus imitate patterns of power in antiquity. As the city grew, the large number of tombstones were removed from church floors and stored in the rooms of the former convent, which became a municipal museum in the early twentieth century.

After the founding of the museum, these common tombstones were included in its inventory as an anomaly, protected as part of the city’s historical legacy. With a view to adding value to the permanent collection, the museum acquired other tombstones, which were chosen for their uniqueness and relocated from different geographical areas based on heritage preservation criteria. …

This wealth of funerary motifs shaped the museum’s collection. Over time, the initial jumble of spaces was emptied out to make room for the new services of a contemporary institution, improving circulation and increasing its versatility. As a result, many of the tombstones amassed ended up being relocated to different storerooms.

When this project was presented, the paper rubbings temporarily took over the transit areas and the space of the permanent collection. The procedures, lines, and materials used on the carved surfaces of the tombstones generated a series of images that were different in each case, thus calling into question the credibility of the means of reproduction. The same process was used on eroded tombstone reliefs, creating illegible stain-images. The rubbings scattered on the ground emulate their original position and overlap, eventually generating a continuous—arbitrary and unpredictable—image (shadow line).

In this exhibition, the rubbings are displayed on the floor of another museum, decontextualized from the original arrangement. In conversation with the other works in the exhibition, they give rise to a final image of ever-changing continuity. Moving from the hidden to the obvious, from abstraction to matter, it shows that, with the passage of time, the trend toward dematerialization means that identification with the past no longer requires a physical record, but access to the traces that remain.

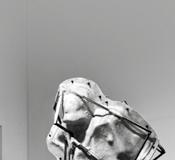

Modelos y constructos (Models and Constructs), 2014

Steel and polyester resin on fiberglass

This double body emerged as a result of applying the process of sculptural technique in reverse. A public bronze statue of an illustrious philosopher was used as a pretext. The sculptural form presented in the exhibition room is the negative mold, which is empty inside. Thus, this result of a process of industrial documentation deconstructs the intention of the monument through its own absence. The shell, made up of several detachable sections that are assembled together with screws, opens up the fictitious possibility of serial reproduction. In turn, the metal tube frame fitted to the outside to stabilize and reinforce the mold generates a double without any purpose, coexisting in the same room like a phantasmal presence.

Exhibited in:

1. Finite Location, Wiener Secession, Vienna, 2014

2. Galería Elba Benítez, Madrid, 2016

3 and 4. Unequal Diameters, Raven Row, London, 2023

5. Partial View, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2023

Obstáculos para la renovación (Obstacles for a Renovation), 2010–22

C-prints on wallpaper:

14 pieces, black and white, 125 × 100 cm (each)

6 pieces, color, 145 × 120 cm (each)

1 piece, color, 118 × 79 cm (each)

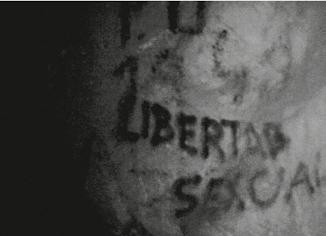

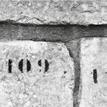

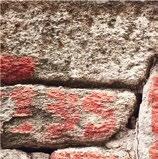

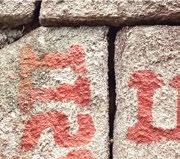

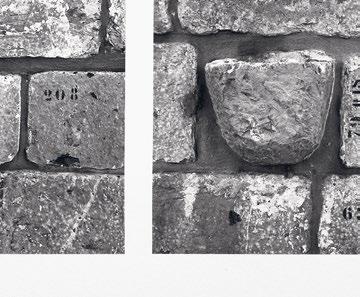

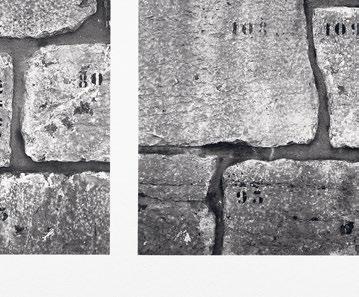

The numbers were occasionally printed with a standard die-cut stencil, resulting in a particular typography of uniform size. Most were painted freehand with a brush, and they lack symmetry. There seem to be no specific guidelines as to the use of color or the choice of technique. Taken as a whole, they appear to be signs from a larger plan.

In some cases, the numbers are traces of building displacements or changes that have been carried out, generally as a result of major works. They are presences abandoned at will that have not yet been erased by the passage of time. In other cases, the masonry remains unaltered in its original site, with the numbers painted on it, as if bearing witness to a failed plan that was never carried out.

The reformulation of historical elements necessarily implies a second life, in which they are stripped of their original sacred nature. In the exhibition, these modern versions of relocated “secondhand monuments” become a motif, generating new images and permutations.

Through the camera lens, as close as possible before losing focus, the numbers are abstracted and isolated from the broader overview. As such, they appear like signs without context. Depending on their position, cardinal points rather than numbers are shown on some of the key pieces of the displaced masonry. When the walls of the exhibition space are covered with the images printed on adhesive paper, the numbers and letters are rearranged, disrupting the continuity.

The occasional protection of heritage elements in the past can be compared to the philanthropic campaigns of corporations today, aimed at the limited preservation of historical and environmental assets in an attempt to transmit positive values.

194 ink-on-paper prints (97 sheets recto and verso)

Dimensions, adjusted calendar format: 8.9 × 13.5 cm

Size of each printed sheet: 16 × 24 cm

This graphic edition emerged from graphic designer Filiep Tacq’s invitation to produce a temporary work for a wall in his studio, located in a village surrounded by forests. It is linked to Compendium, the artist’s first response to Tacq’s invitation. The two formulations coexisted ephemerally, mutually connected to each other.

The daily publication of Almanaque arose from the worktable in the studio and the need to organize the typologies and the narratives associated with the materiality of the farm tools lent by local residents following the initial call. One page was printed each day during the three-month exhibition period, in an attempt to record the fleeting nature of this intervention. The prints took the form of a calendar block, a format that was very popular in the rural world until recent times.

The front side of each page consisted of the daily information printed on traditional calendars, based on an analysis of historical trends and examples: the lunar phases, church saints’ days, sunrise and sunset times, and so on. The back of each page, written on a daily basis, contained knowledge related to the cycles of nature, oral wisdom transmitted by the valley’s inhabitants, information about endemic plants and trees, animal species spotted in the elapsed time, and social customs and special events that took place during the process. It also included descriptions of the tools and implements sourced for Compendium—mostly linked to timber extraction and processing—which were gradually gathered and displayed during the exhibition period.

In this second iteration, the calendar pages from the original intervention have been rearranged and displayed on the museum walls in the form of an uninterrupted timeline. They protrude longitudinally, creating an empty space around the central element of the tools grouped on the floor of the exhibition hall. Thus, the numbers on the calendar, which initially appear neutral, bear witness to the elapsed period of time.

258 — 2022 — 107

Sol: 7:53 a 20:28 – Luna: 23:09 a 13:20

Cuarto menguante el 17 de septiembre

Los Dolores Gloriosos de N. S.; Ss. Nicomedes, Teodoro. Ntra. Sra. del Camino, patrona de la Región Leonesa.

Un incendio ha destruido una vivienda familiar pasada la medianoche. No ha habido que lamentar daños personales, puesto que la propietaria, una persona de avanzada edad, pudo salir por sus propios medios. El dispositivo de bomberos consiguió que las llamas, que se iniciaron en la cocina, no afectaran a los edificios colindantes ni al sótano de la vivienda siniestrada, y evitaron que se propagaran a los alrededores. La casa donde se originó el fuego, una vivienda antigua de piedra y madera, situada en el centro de la aldea, ha quedado totalmente calcinada. El fuego, se inició en la cocina, y cuando llegaron los bomberos ya estaba muy desarrollado y afectaba a varias estancias de la casa. Apenas dos horas después de haberse producido el aviso, los bomberos dieron el fuego por extinguido. Iniciaron la extinción desde el interior y, tras el colapso de la cubierta, centraron el trabajo en controlar la propagación horizontal para salvar un pajar y una vivienda anexos. Una vez extinguido el incendio, procedieron a realizar labores de desescombro, refrigeración y revisión de temperatura de la zona afectada

Cotton fabric, tools, and implements on temporary loan: saw, jacks, miter saw, adze, filling blade, axe, hatchet, axe, chains, drag spike, strickle, bucksaw, gimlet, axe, saw set, pail, sickle, rasp, ropes, whetstone, mallet, etc.

This temporary intervention is directly linked to Almanaque (Almanac). Both works arose in the same space and time, in response to an invitation from Filiep Tacq.

For centuries, the economic livelihood of the valley’s inhabitants relied mainly on the exploitation of the surrounding communal woodland. With the advent of mechanization, many of the hand tools and implements associated with this way of life became obsolete and were kept for specific tasks or stored away for no particular purpose.

Some of the tools took on a second life as decorative elements inside domestic spaces—vestiges of times gone by. Often, these memory objects from the past, of no particular value, are also symbolically reappropriated by the tourist and hospitality economy.

In light of this, Aranberri collected a series of tools with the idea of holding a temporary exhibition in Tacq’s studio, located in the same area. The tools had been lent by local residents in response to a word-of-mouth request. However, the initial idea of displaying them as if in a mock museum was discarded, and in the end they were not hung on the walls. Instead, they were grouped together and scattered around the worktable in the studio for the duration of the intervention. In this improvised layout, a space was cleared so that the daily publication of the Almanaque calendar pages could take center stage.

Once the intervention had ended, each tool was photographed against the backdrop of a white sheet spread on the ground, before being returned to its owner. This approach is reminiscent of the methods of early twentiethcentury ethnographic studies in which frequent visits were made to rural areas to document their customs and material culture.

Echoing this gesture and thanks to the generosity of the residents of the village, the tools are now presented as a single group on the white sheet in the exhibition space at the museum.

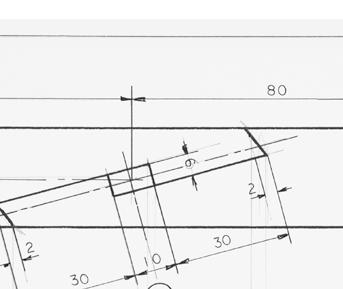

Operatori, 2021–ongoing

74 drawings, 21 × 29.7 cm (each)

Pencil and ink on paper

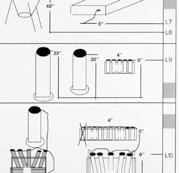

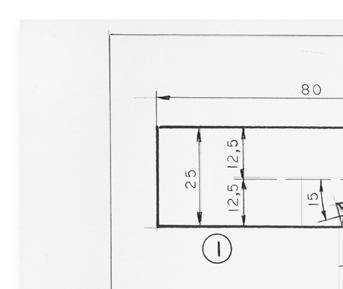

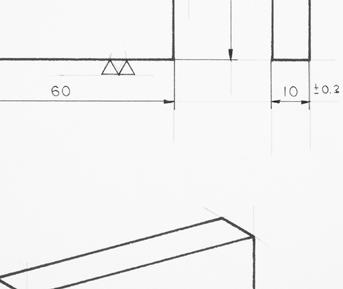

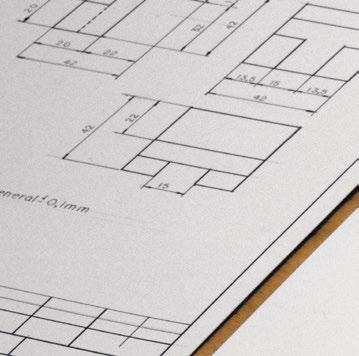

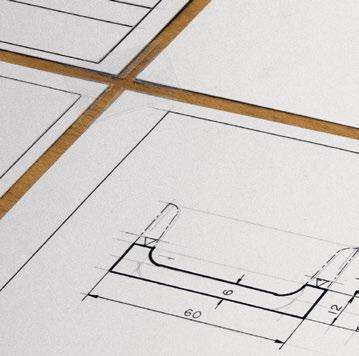

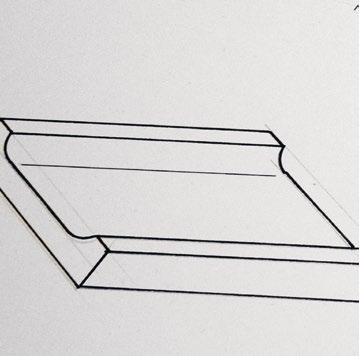

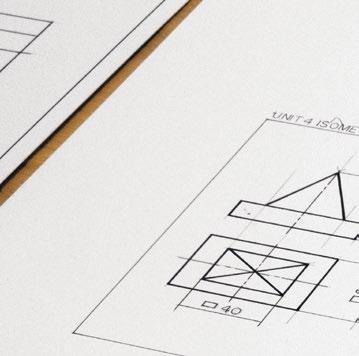

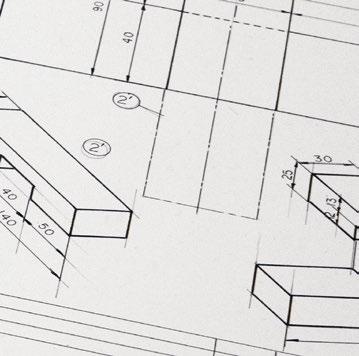

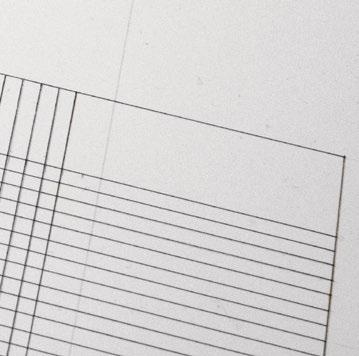

The technical drawings, reminiscent of plates from a textbook, are handdrawn. At first glance they resemble a diverse collection of geometric shapes and prototypes. On closer inspection, we can see ink lines drawn over faint pencil sketches. The drawings, copied from existing worksheets, are unfinished: there are blank boxes that seem to omit some of the original notes. The ink lines are imperfect and some are smudged. In some cases, mistakes in the drawings have been left uncorrected. Each drawing corresponds to a type of figure or model in preparation. The lines reveal the physical properties that determine scale, proportions, and volumes. Some text definitions, also written in ink on the paper, take on ambiguous connotations when detached from their educational purpose. The versions in different languages show the diverse origins of these exercises. And even though agendas change, the set of geometric shapes remains the same.

The educational worksheets on which the drawings are based were commonly used in the historical context of vocational training schools. Different variations of the exercises—of a more intuitive origin—were incorporated into general educational units to develop formal teaching programs in the industrial era. In addition to their role in professional technical training, we can identify an aspect of social discipline in the practices associated with these types of exercises, which, like other programs of modernity, have gradually regulated productive lives. There is thus a possible correlation between the originally technical terminology used in the exercises and their translation into the systems that surround us.

Over time, the learning of mechanical trades has been replaced by the programming of automated machines. However, while the production of industrial work has moved toward ubiquitous technical knowledge, the formal vocabulary and manufacturing methods have remained the same, albeit with different results.

Operatori focuses on the glossary of forms and programs that shape our material and immaterial realities. The term “operatori”—the plural of the Italian word for operator/worker, which describes object and subject as one—implicitly alludes to twentieth-century radical educational movements and models, and to a series of practices based on the potential of technical training as a means of emancipation. It thus suggests a vanishing point for the utilitarian training culture that the technical drawings seem at first glance to encapsulate.

Steel parts/exercises, on temporary loan from local residents

Unformed steel sections

Wooden (okoume) tables, 1122 × 244 × 89 cm

Kraft paper rolls, 30 × 30 × 130 cm and 20 × 20 × 140 cm

Variable dimensions

The large wooden tables are placed across the space, from one side to the other, at an oblique angle with regard to the symmetry of the room’s architecture. When a table meets the wall, it is cut so as to continue on the other side, in the same direction, creating the effect of a drawn line. This layout is a smaller-scale version based on the original presentation, where various parallel rows of tables cut across whatever they encountered on their path: walls, artifacts on display, and exhibition devices. A table-sized gap interrupts the longitudinal row, in order to comply with the museum’s evacuation protocols and also to allow visitors to pass. The table removed to create the opening is placed upright against the adjoining wall, revealing the lightweight materiality of its construction, in contrast to its solid appearance. In the earlier exhibition the tables were arranged in a diagonal line, separated from each other, maintaining the angle and size of the space between them. Two tables with no apparent use were placed on top of each other, with the four legs facing upward. Several kraft paper rolls were placed vertically around the tables.

This work emerged in conjunction with the Peace Treaty project curated by Pedro G. Romero as part of the Donostia/San Sebastián European Capital of Culture program. Several artists were invited to respond to the theme of the main exhibition, which explored representations of peace in the history of art, culture, and the law.

Under this premise, the research focused on the context of the weapons industry, the roots of which went on evolving—sometimes in the same sector, but in most cases diversifying and opening up to other lines of production. Industrial growth has traditionally been linked to the logic of weapons production, and from the twentieth century on, following successive reforms, the technologies and knowledge developed in the arms industry started to move into civilian industry, particularly areas linked to the domestic sector.

Common practices carried out as training exercises in the context of industrial production produced certain shapes that harbor a kind of ambiguity—that of a material that is inoperative, fulfilling its purpose in the mere learning of the trade. They are geometric elements produced from solid steel sections as calibration, fitting, precision, and composition models.

As simple manual exercises, they have an abstract power that maintains a certain distance from what were originally gun-making learning models, later developing into the discipline of vocational schools of different levels.

…

Over time, these manual programs were moved out of workshops and replaced by increasingly mechanized production. This work recreates a small-scale version of the type of trade fairs that were historically organized as social events in areas associated with industrial culture.

This entailed gathering a series of common exercises sourced from private collections, schools, and stored crates that preserve the idiosyncrasy of this medium of discipline. Organized in the form of a temporary museum exhibit, they intermingled and contrasted with the permanent educational exhibition at the Museo de la Industria Armera in Eibar. The resulting intervention interfaced with the entire museum, recreating the repertoire of materials and exercises linked to learning the gunsmith’s trade.

Some of the materials shown—which their owners have kept for sentimental rather than heritage value—are brought together again in the material landscape of this exhibition, in which the set of exercises contrasts with the untreated steel sections displayed as hypothetical raw material for their production. This layout also reinstates the exhibition devices, seemingly creating an oblique intersection through the different spaces of the museum.

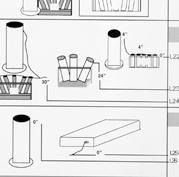

Steel shelving, 296 × 38 × 189 cm

Cut steel parts

Quadrangular: 3 × 1.5 × 1.8 cm; 2.5 × 2.5 × 10.5 cm; 3 × 2 × 23.5 cm; 3.5 × 3.5 × 14 cm; 4 × 2 × 8.5 cm; 5 × 5 × 10 cm; 4 × 4 × 12 cm; 5 × 1.5 × 9.5 cm; 6 × 4 × 10.5 cm

Cylindrical: 12.5 × ø 4 cm; 4 cm × ø 3 cm; 7 × ø 2.5 cm; 7 × ø 5 cm; 4.5 × ø 6 cm; 3 × ø 5 cm

Calibrated: 3 × 3 × 6.3 cm; 4.5 × 2 × 12 cm; 3.5 × 3.5 × 6.3 cm; 6 × 2 × 9.5 cm; 4.5 × 4.5 × 3 cm; 6 × 6 × 3 cm; 6 × 6 × 12.5 cm; 12 × 2 × 12 cm

Hexagonal calibrated: 5 × 5 × 12 cm; 2 × 2 × 12 cm

Cylindrical calibrated: 4 × ø 4.5 cm; 3 × ø 7 cm

Materials change, as does their meaning, until they end up differing from their original conception. We can see these obsolete solid forms as fossils from the twentieth century. A collection of recent history that reappears as antiquity.

The solid metal parts cut into sections present the potential of a hypothetical production. Each different size and ratio would thus be a different possible exercise. A square-shaped cabinet—which is also metal—provides compartments for storing the pieces in an orderly manner according to their width, ratio, and hardness, resulting in a formal cataloguing system.

However, the specifications of the exhibition room in which these materials were placed for the first time meant it was unable to support their full weight. Thus, the parts have been scattered around the floor of the room, distributing the excess load on the surface, away from the empty shelves.

On the floor of the museum, the parts and the shelves are again separated, as they far exceed the maximum recommended weight. In this case, the pieces have been scattered chaotically on the floor, extending horizontally to the area near the wall, in order to comply with the technical standards.

Dana, 1994

Polyester resin and fiberglass

Dimensions: approx. 26 × 26 × 25 cm

Polyester resin and fiberglass

Dimensions: 33 × 41 × 8.5 cm

Goetschmann projectors are custom-engineered for the most demanding applications. Due to their extremely bright and evenly illuminated screen images, they are preferred for large auditoriums like congress halls or stadiums.

If you have ever experienced how much more impressive a 6×7 transparency looks on a light table compared to a 35mm or even 6×6 slide, you will be even more enthusiastic when you see a 6×7 slide projected on a large screen, compared to the smaller formats. This is not surprising if you consider that a 6×7 transparency is 4.5 times larger than a 35mm slide. This also means superior sharpness, resolution, and color fidelity. In comparison with beamers with 2 million pixels, the G8585 AV offers approximately 50 million

Consider further the superb triple condenser, coated optical system, the finest Schneider projection lenses and the extreme brightness — light output 6000 lumens— of the Goetschmann projector, produced by a 400-watt quartz halogen lamp with dichroic reflector (250-watt or 300-watt projectors offer only 1000–1500 lumens).

These features combine to bring out the startling image quality, the fine detail, and the subtle tonal richness, which the best 6×7 camera lenses have created on your film. Your will experience an almost lifelike, three-dimensional quality, far superior to what you have seen with other projectors.

The Goetschmann G 8585 AV projectors will accept standard SAV-type multi-image dissolve controllers and can be used for fantastic multi-image shows. They can also be equipped with optional automatic lamp changers, as well as PC (Perspective Control) adapters.

Projection of 40 medium-format slides

The location of some of the projected images is not easily identifiable. Perhaps because they predate the major plans, they have shaped a new domesticated landscape. Some of the slides show the presence of humans, looking at, interpreting, and surveying the land, probably in anticipation of the changes yet to come.

The slides also show elements (material fragments) that have been lost, as well as repurposed remains subjected to processes that seek to reestablish an identity linked to the past with morphological and semantic changes. The highways, reservoirs, industrial parks, railways, high-voltage lines, bridges, and ski resorts that cause these effects are outside the frame of the images.

The projection presents a story of stories, or an interrupted continuity in which focused and concrete examples decontextualized from the original situation overlap, and images from different sources are interspersed. On the one hand, it includes copies of original photographs deposited in corporate archives and the private collections of amateur photographers. On the other, it incorporates images taken as a fortuitous result of an itinerant, updated approach to those same places.

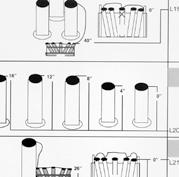

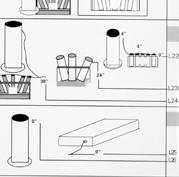

Modular system consisting of panels, columns, footings, extensions, and various additional elements.

23 steel panels:

13 grids, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

6 filler panels with matte black lacquer finish, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

2 filler panels with polished stainless-steel finish, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

1 glazed panel, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

1 tinted glazed panel, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

1 grid with inlaid concrete, 324 × 194.4 cm (each)

29 steel columns:

19 matte black lacquered columns, 210 cm (each)

3 columns with raw stainless-steel finish, 210 cm (each)

3 columns with polished stainless-steel finish, 210 cm (each)

4 matte black lacquered columns, 420 cm (each)

11 footings:

9 matte black lacquered steel footings, 42 × 21 × 21 cm (each)

2 raw stainless-steel footings, 42 × 21 × 21 cm (each)