Early Stages

The design process is not and should not be a linear process, and it has certainly not been for my thesis exploration and project design. When initially looking at the general idea of my thesis, lighting, I was unorganized and lacked a guiding hand to point me toward meaningful design. My work was initially looking at parks, seeing how they could be changed through the use of light to create spaces rather than just focusing on lighting pathways. Parks and the sites in question were not filled with issues, and much of what I was talking about was subjective. Yet, I did not have a basic understanding of what I was trying to accomplish fully figured out, so this whole series of iterations was deemed a “failure”.

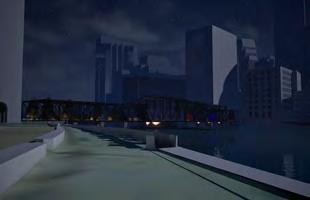

The benefit of this initial exploration was that it pushed me to want to have realistic or as close to realistic as I could get simulations/ testing of what different lighting technologies could accomplish in different spaces. That desire brought me to use Unreal Engine 5, a game-making tool that allowed for importing of 3d models and site information, as well as new “Lumen” simulation technology that could allow me to create realistic lighting conditions for my design work.

Small Scale Testing

The beginning of the Spring semester was a time for reflection and resetting my focus. I needed to take a step back and look at the root of my thesis, lighting. Further exploration of the element was necessary on a smaller scale. I wanted to be playful with my first approach, going onto the porch of my apartment and testing the effects of different colored lights on surfaces. I saw how it drastically changed the surfaces it was applied to, and the initial feelings that these different colors could invoke in people coincided with my research on the topic at this point. My takeaway from this experiment was that light can frame a space and different lights can change the feelings associated with a space.

Looking for a Site

The next step was figuring out where to put this exploration into lighting design. This was also the point where I decided to switch from parks to focus on industrial sites, seeing the problems they cause for the communities around them as a strong avenue to pursue.

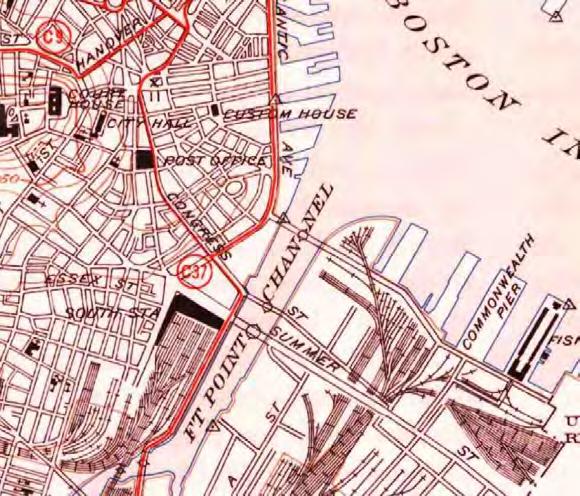

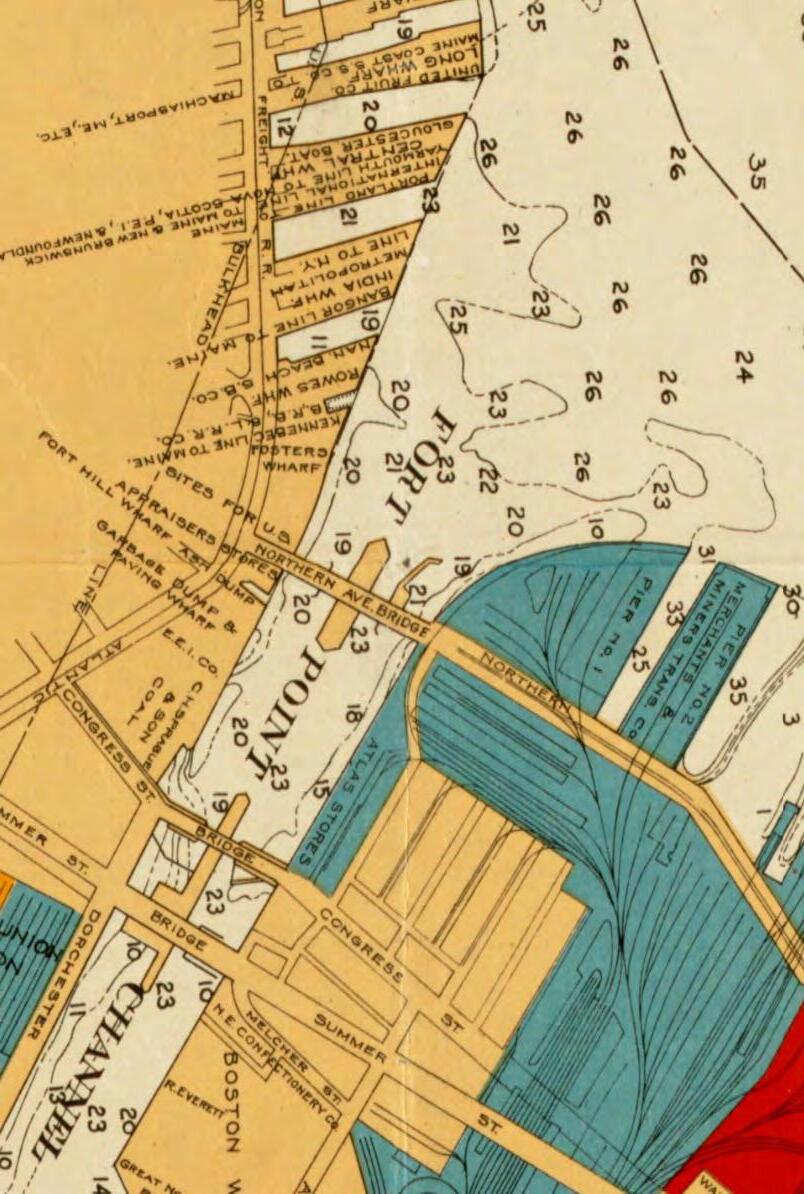

I looked at several sites across Boston, from old rail yards to abandoned docks. Two sites stuck out in my search. The first one I investigated was the Old Northern Ave. Bridge. There was also an East Boston Rail Dock that I investigated. My visits to these sites were on a particularly cold day, which gave me a rare, almost private viewing of these spaces, to see them without the bustle of sites surrounding them.

Analyzing Sites

Initially, I looked at lighting these places based on their historical aspects alone, and found that they could be strong factors to draw upon. The illumination scheme for this site focuses on the historical nature of this bridge, casting light to highlight the key features that make this structure so central to Boston’s history. The steel frame and the rotating structure are such features. Similar lighting schemes would be used in the area to attract and guide pedestrians to the area. This would tie together the connection of the two seafood establishments on either end into one food court experience/crossover.

This old harbor rail has gone into heavy disarray since its decommission decades ago. This area has gone through recent development, bringing the focus onto East Boston’s vibrant diverse background. The lighting of this site would highlight that history by reminiscing on the rail yard past through luminaries of rail-like form. This would coincide with artwork and a connection to the on-site ICA.

However, both of these approaches lacked reasoning beyond historical aspects for why I was attempting to do what I wanted to do with light. For that reason, I decided to pick one site and move forward with research and design development.

Pavilion/Stage ConnectiontoMarina

Reclaimed/RepairedDock

Settling on a Site

The site I landed on was the Old Northern Avenue Bridge to intervene.

The Old Northern Ave. Bridge was first opened in 1908 and served pedestrians, cyclists, automobiles, and even freight trains. Nestled between downtown Boston and Seaport, Old Northern Avenue Bridge was once a key mode of all forms of transport for Bostonians. now it lies unused and in a constant state of limbo between being developed or destroyed. Both areas around the site are rapidly developing with more high rises and larger architectural projects. Exposure to the elements for over 100 years eroded the infrastructure of the bridge. The bridge closed to all traffic in 2014 after structural integrity was investigated and found lacking.

According to the American Road & Transportation Builders Association, 1 out of every 3 bridges in the United States must be rebuilt or repaired to avoid structural collapse. Interestingly, while having been closed off for more than 10 years at this point, it is still receiving some amount of power to lights that focus on a decaying walkway and leftover planters from years ago. The last few years have been stagnant for any kind of development, with the site remaining unused for a decade at this point.

Existing Conditions

Existing Conditions - Program

Investigating the surrounding program of the area, I wanted to look at what I could add to the area/connect the existing elements through my work on site. In this area, there is a strong domination of residential, commercial, green areas, waterfront access, as well as a small but notable educational element present. Baring residential, these are the elements I will build upon.

Existing Conditions - Circulation

Movement is a key part of this site. Circulation for my design wants to engage between stationary and restful moments, to more active and exciting instances. Right now, the site is completely cut off from the surrounding area, forcing pedestrians to share a walkway with the primarily car-centric neighboring Evelyn Moakley Bridge, leaving an opportunity to create a space purely for pedestrian movement.

Character Exploration

An experiment in representation that I played with was designing a narrative based on several characters to use the site and its design in various functions. The group of characters I dubbed was “L.I.G.H.T.S.S.”, Lia on a night out, Issac going for a jog, Greg a retiree going finding a place to read, Heather an office worker heading home, Terry a security guard getting off the night shift, and finally Sam and Stacy who would be out on a date night visiting the market space.

This was an important experiment, yet criticism of this approach pointed at it being too individual-focused and lacking a more general approach that would be needed to reach the greatest number of people. There was also a need to have more explanation of design decisions for why I was using certain kinds of lighting. It caused me to again take a step back and investigate how I would define my definition of “correct” lighting for the space.

Figure 3.15 Circulation, Detailed Sections & Perspectives of each characters walk through of the site in different ways. Lucas Chichester, “L.I.G.H.T.S.S”.

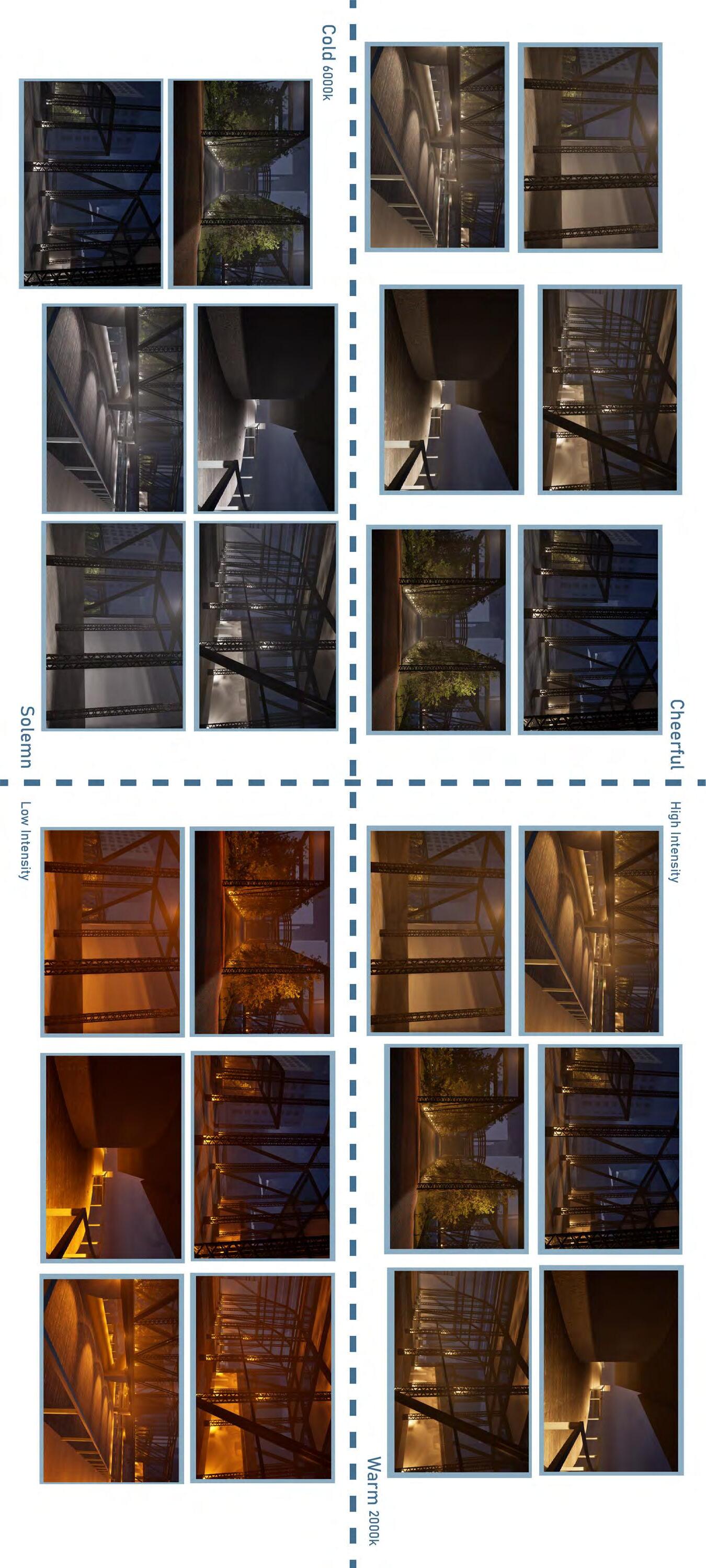

Testing Light

To identify what I mean when I say “correct” lighting, I needed to look at the site through several different light lenses defined by lighting color temperature and the intensity of lighting fixtures used throughout the project. In the array to the right, the color temperature ranges from 2000 kelvin (Sunup/Sunset) to 6000k (Daytime). The intensity ranges from 25-100 candelas throughout the project. Different environments work best for different programs, experimenting through these conditions allowed me to best define the lighting in these different parts of the project.

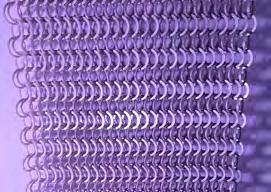

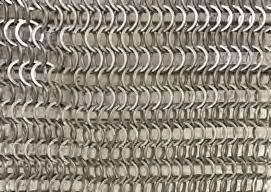

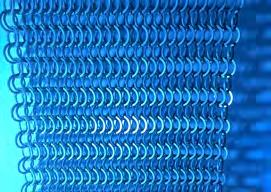

Material Testing

Materials are essential to lighting, for we are only able to see surfaces that light is reflecting off of. With the existing structure of the site, I found a material that could interact with light, but that didn’t limit visibility through it. This led me to utilize this interesting mesh/ chain material as the scrim that I would use throughout the project, to create a malleable surface that light could interact with strongly.

Precedents of Atmosphere

To further define my lighting methodology and design, I investigated several precedents focusing on the atmospheres they were producing, with their programs being similar to what I would want to implement on-site. These projects are examples from lighting designers L’Observatoire International and LAM Partners, two very amazing design firms.

Reflective & Expansive

Lower & Personable

Shadowed & Ground-lit

Focused & Centered

Welcoming & Comfortable

Figure 3.22 Lighting atmosphere precedents, a collection from the work of LAM Partners and L’Observatoire International. LAM Partners & L’Observatoire, “Lighting Atmospheres Precedents”.

Lighting Objectives

From my testing and precedent research, these are the objectives I’ve devised to light my project effectively. They were worked on with the aid of my advisor Carla Wille, who was instrumental to my understanding of architectural lighting. Through their use, they guided the design of my project to its concluding outcome.

Lighting is best used when it has specific goals in mind for its implementation.

1. The lighting of the whole project should highlight and focus on the historical nature of the site.

2. Bar/Restaurant - Lighting for this space should be personal, and closer to those who are within the space.

3. Green Walks - The green walks should be tranquil, with a guiding set of lights to bring pedestrians into the site.

4. Waterfront Taxi - The lighting of this section should focus on creating a well-lit environment for signage and pedestrian access to the water and water taxi system which would be a new public transit option on site. It should also utilize the unique relationship between water and light.

5. Market/Retail - The market area lighting should allow visitors to see the products within the area and feel comfortable walking throughout the area. As with the waterfront taxi space, it should utilize the close relationship with the water present on site.t

6. Performance Center - The lighting in this area should highlight where movement and performance take place, while not being uncomfortable for seated visitors. It should also utilize more specialized lighting conditions to enhance the experience of the performance.

7. Central Lighting - This area should be the beacon of the site for the surrounding area, its lighting should attract those from the surrounding area and encourage them to stay/use the surrounding programs.

Chapter 4 Beacon of Light

Existing Site Conditions

New Conditions

Figure 4.2 With new additions and a program guided by light, this site would change from an abandoned remnant to an Urban Spectacle. Lucas Chichester, “New Conditions”.

New vs. Old

Figure 4.3 The new areas highlighted leave the existing structure intact (with reinforcement being a given) and focus on an integrated program working to attract pedestrians to the site’s new uses. Lucas Chichester, “New vs. Old Diagram”.

Figure 4.4 Above: Introducing the program was essential to envisioning the potential of this site and the opportunities within this fascinating structure. The program consisted of natural green walks, gathering, performance space, a new commercial market area, as well as an active water taxi dock for transport through that system. All of this would be built on keeping the bridge locked at a 90-degree angle and introducing a pair of operable and permanent connecting bridges to not forget about the historic movement of the bridge, but not limit people’s movements throughout the site. Lucas Chichester, “Program Diagram”.

Figure 4.5 Top Right: This testing of material and atmospheres led to a division of the program into 5 lighting atmospheres. These would dictate and define the lighting methodology I would use in each section of the project. Lucas Chichester, “Light Atmospheres”.

Figure 4.6 Bottom Right: These atmospheres would be subdivided into “special” vs. general lighting conditions, to further define the use cases of these areas. Notable, the central area would be primarily special and exciting conditions, while the wings and lower dock area are aimed at relaxed and utilitarian. Lucas Chichester, “Special vs. General Lighting Diagram”.

Special vs. General Lighting

Greenway/Natural

Stationary Bridge

Restful Area

Existing Structure Reinforced and new program built uponit

LightEnveloping Infrastructure

Shading Canopy

Intermittent LED Screens

Lighting Key

A. 3500k Basic Uplight

B. 2500k Spotlight

C. RGB Spotlight

D. Mesh Projection Sheet

E. 4000k Basic Uplight

F. 3500k Basic Downlight

G. Railing Light

H. 3500k Underwater Spotlight

J. Recessed “Cobra” Light

K. Low Lighting Sheets

L. Paneled LED Screens

M. LED Screens

Lighting Key

A. 3500k Basic Uplight

B. 2500k Spotlight

C. RGB Spotlight

D. Mesh Projection Sheet

E. 4000k Basic Uplight

F. 3500k Basic Downlight

G. Railing Light

H. 3500k Underwater Spotlight

J. Recessed “Cobra” Light

K. Low Lighting Sheets

L. Paneled LED Screens

M. LED Screens

Lighting Key

A. 3500k Basic Uplight

B. 2500k Spotlight

C. RGB Spotlight

D. Mesh Projection Sheet

E. 4000k Basic Uplight

F. 3500k Basic Downlight

G. Railing Light

H. 3500k Underwater Spotlight

J. Recessed “Cobra” Light

K. Low Lighting Sheets

L. Paneled LED Screens

M. LED Screens

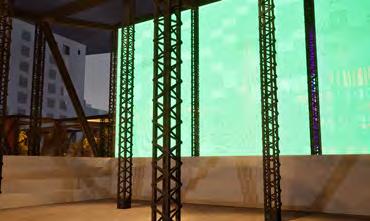

To offer some sense of scale, each bay of the structure is just over 21 ft. wide, as well as 30 to 50 feet tall. Lighting fixtures and new materials work with the preexisting structure to create the environments outlined in the previous atmosphere map. These atmospheres can also change as the need arises. These areas of zoom in are the Green Walk and (on the next page) the Gathering Space, two areas of the project with very different use cases for light, one being somber, while the other is more exciting.

Gathering Space

Seasonal Changes

Spring Summer Fall Winter

Figure 4.13 As seasons change, this site and its lighting can adapt and shift according to how the space is being used or what the intention of the space’s use should be. Lucas Chichester, “Seasonal Birdseye Views”.

Temporal Video

Since light is such a dynamic element, I found that a video format was the best way to show the quality of changes in environment through the use of different lighting effects. This is utilizing the same simulation technology that I have mentioned in my previous writings.

Please scan the QR Code or go to the link.

https://youtu.be/1HddeaHX97o

Figure 4.14 Central Promenade with alternating lights that bath different sections with movement changing lighting conditions. Lucas Chichester, “Central Promenade”.

Figure 4.14 Central Promenade with alternating lights that bath different sections with movement changing lighting conditions. Lucas Chichester, “Central Promenade”.

Chapter 5 Reflections of Light

The other day, I had a thought when preparing for the final: “I didn’t think Architecture could get harder than my first four years in undergrad.” Then it did. For the last five years of my life, architecture has been the most difficult but rewarding thing I have ever done. Over these last few months, my thesis exploration has been an uphill battle, pushing myself to learn new ways of expressing my ideas so they can be accepted and understood by my peers and faculty.

During the final discussion, I received positive feedback from my peers and faculty. They praised my graphic representation and the quality of my work. I had focused on lighting as the primary element and actor for change, and all the pieces fell into place. The feedback I received was that my work was “beautiful” and “profound.”

However, some criticisms were also made. I should have investigated the surrounding environmental properties of the area more thoroughly. It was also suggested that I should have further iterated the program and architectural elements of the project. The effects of surrounding buildings’ lighting and the environmental effects of water and wind on the site and lighting effects were also questioned. My peers suggested that I look at projects like the Pittsburgh Children’s Museum and the work of Janet Echelman for inspiration.

F inally, a larger question was posed about the economic implications of the project. While I researched the energy benefits of LEDs and lighting technologies, there is also the aspect of whether the site needs money-making infrastructure or if it could be a standalone public works project.

Overall, this experience was a positive sendoff to my time in architecture school. Although there were many hurdles to overcome, I am content with the final product and proud to call it my Thesis

Back Matter

Figure Notes

1.1 - 1.4 Images created by Lucas Chichester (CC BYNC-SA-ND).

1.5 Adobe Stock, “Madrid Plaza”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com.

1.6 Adobe Stock, “Perspective View of Modern Architecture”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com.

1.7 Adobe Stock, “Hallway Lighting”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com.

1.8 Adobe Stock, “Metallurgical Factory”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com. 1.9 Google Earth, “Aerial of Abandoned Wharf”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock. adobe.com.

1.10 Image created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NCSA-ND).

2.1 Image created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NCSA-ND).

2.2 Google Earth, “Old Rail Dock”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Google.

2.3 Adobe Stock, “Coal Mine”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com.

2.4 Lam, William, “Lighting Section”. Accessed 2024. Scanned Picture. Perception and Lighting – As Formgivers for Architecture.

2.5 Lee, James P, “Alaska Monument Lighting”. 2009. Photograph. Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Centennial. 2.6 Springer-Verlag/Wien, “LightBridge”. 2012. Photograph. Springer-Verlag/Wien.

2.7 Nielsen, Stine Louring, “Light Movement Experiments”. 2021. Photograph. SINTEF Academic Press.

2.8 WRT, “Steel Stacks Lighting”. 2017. Digital Photograph. Landezine, https://landezine.com/ bethlehem-steelstacks-arts-culture-campus-bywrt/.

2.9 Berns, Thomas , “Lighting Explosion”. Accessed 2024. Duisburg Kontor Management, https://www. landschaftspark.de/en/leisure-activities/lightinstallation/.

2.10 Bigg Design, “Craiglinn Underpass”. 2011. Digital Picture. Bigg Design, https://www.biggdesign.co.uk/ cumbernauld-underpass.

2.11 Adobe Stock, “Lighting Stair”. Accessed 2024. Digital Picture. Adobe, https://stock.adobe.com.

2.12 Martin, Ferran, “Lighting Cartoon”. Accessed February 11, 2024. Cartoon. https://metode.org/ cartoons/the-eyedropper/light-pollution.html.

2.13 Jones, Bassett, “Lighting Postcard”. Accessed 2024. Scanned Picture. Structures of Light. 2.14 Image created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NCSA-ND).

3.1 - 3.17 Images created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NC-SA-ND).

3.18 Berns, Thomas, “Duisburg-Nord Park, Duisburg, Germany”. Accessed 2024. Duisburg Kontor Management, https://www.landschaftspark.de/en/ leisure-activities/light-installation/.

3.19 WRT, “SteelStacks Art Campus, Bethlehem, PA”. 2017. Digital Photograph. Landezine, https:// landezine.com/bethlehem-steelstacks-arts-culturecampus-by-wrt/.

3.20 Seaward, Sharon, “Memorial Bridge, NH”. Accessed 2024. Photograph. Portsmouthnh.com, https://www.portsmouthnh.com/listing/memorialbridge/.

3.21 Weiss/Manfredi, “Hunter’s Point Park, New York, NY”. Accessed 2024. Photograph. Weiss/Manfredi, https://www.weissmanfredi.com/projects/15-hunters-point-south-waterfront-park.

3.22 LAM Partners & L’Observatoire, “Lighting Atmospheres Precedents”. Accessed 2024. LAM Partners & L’Observatoire, https://www.lampartners. com/projects/, https://lobsintl.com/projects/.

3.23 Image created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NCSA-ND).

All images in Chapter 4 created by Lucas Chichester (CC BY-NC-SA-ND).

5.1 Staudenmaier, Eric, “Children’s Museum Ceiling”. 2015. Photograph. Smithsonian American Art Museum, https://www.archdaily.com/928939/ installation-at-childrens-museum-freelandbuck/5 dd760f73312fdd7ba0000f1-installation-at-childrensmuseum-freelandbuck-photo.

5.2 Echelman, Janet, “1.8 Renwick”. 2019. Photograph. ArchDaily, https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/ echelman.

5.3 Nguyen, Quang, “Pictures of Lucas’s Presentation”. 2024. Digital Photograph.

Bibliography

1. American Road & Transportation Builders Association, Bridge Report 2023, ARTBA, 2023.

2. Brian Seibert, When the Finely Tuned Spotlight Falls on the Lighting Designers, The New York Times, November 11, 2022, https:// www.nytimes.com/2022/11/11/arts/dance/ jennifer-tipton-our-days-and-night.html

3. “Craiglinn Underpass, Cumbernauld”, Bigg Design, accessed February 8 11, 2024, https://www.biggdesign.co.uk/cumbernauldunderpass.

4. “Duisburg Nord Landscape Park”, Latz+Partners, accessed February 11, 2024, https://www.latzundpartner.de/en/ projekte/postindustrielle-landschaften/ landschaftspark-duisburg-nord-de/.

5. Dietrich Neumann, The Structure of Light –Richard Kelly and the Illumination of Modern Architecture, Yale University, 2010.

6. Elizabeth Chesla, SteelStacks Arts Cultural Campus, Bruner Foundation, 2018.

7. Elizabeth Colaton, Charles Bartsch, Industrial Site Reuse and Urban Redevelopment - An Overview, NortheastMidwest Institute, 1996.

8. Giovanni Maria Biddau, Antonello Marotta, and Gianfranco Sanna Abandoned Landscape Project Design, City, Territory and Architecture, 2020.

9. Mark Major, Jonathan Speirs, Anthony Tischhauser, Made of Light – The Art of Light and Architecture, Birkhauser, 2005.

10. S. Louring Nielsen, U. C. Besenecker, N. Hasle Bak and E. K. Hansen, Beyond Vision Moving and Feeling in Colour Illuminated Space, SINTEF Academic Press, 2021.

11. Stephanie Schemel, Felicitas zu Dohna, and Leni Schwendinger, Cities Alive: Rethinking Shades of Night, ARUP, 2015.

12. Susanne Setinger, LightBridge: Embracing the Messiness, Exposing the Analytics, Springer-Verlag/Wien, 2012.

13. Jonathan Crary, 24/7 - Late Capitalism and Ends of Sleep, Verso, 2013.

14. Tyler S. Sprague, The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Centennial,

2009.

15. William M.C. Lam, Perception and Lighting –As Formgivers for Architecture, McGraw-Hill Inc., 1977.

16. L. Dudley Stamp, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, 1951, 97-122.