Reclamation through Light

Light as the Catalyst for Reclaiming Industrial Remnants

By Lucas Chichester Wentworth Institute of Technology Masters of Architecture 2024

By Lucas Chichester Wentworth Institute of Technology Masters of Architecture 2024

By Lucas Chichester Wentworth Institute of Technology Masters of Architecture 2024

By Lucas Chichester Wentworth Institute of Technology Masters of Architecture 2024

Bachelor of Science in Architecture

Wentworth Institute of Technology, 2023

Submitted to the School of Architecture and Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at the Wentworth Institute of Technology, April 2024

Lucas Chichester Author School of Architecture and Design

Certified by Mark Pasnik Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by Jason Rebillot Director of Graduate Programs

©2024 Lucas Chichester. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants Wentworth Institute of Technology permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part using print, digital, or other means now known or hereafter created.

I, Lucas Chichester, am aware of the academic standards for acknowledging non-original content through citation and other means of crediting sources. In compliance with the Institute Academic Honesty policy, this thesis does not explicitly or implicitly represent the work of others as my own, including written work, whether copied verbatim or paraphrased, visual work, whether directly reproduced or redrawn, or content prepared by a third party.

Our senses play a vital role in our daily lives, shaping our perception of the world around us. However, a simple change in lighting can dramatically alter our perception of the same environment. Thanks to technological advancements, we have more control over our urban and community environments, particularly when it comes to lighting. The intensity and color temperature of lighting can significantly impact our mood, level of activity, sense of calm, and even movement.

One of the most significant challenges faced by cities and communities is the negative perception of abandoned industrial and infrastructure sites. These areas are often associated with various environmental, health, and economic problems that affect the surrounding areas. However, through carefully designed urban interventions and lighting, we can change our perception of these spaces and turn them into positive elements for our communities. By illuminating these abandoned urban elements in a new light, we can breathe new life into these areas and create a positive impact on the surrounding communities.

To the ones in my life that I love, who have supported me through it all, you know who you are.

I want to start by thanking the one who initiated my interest in lighting design, my advisor Carla Wille. Through her guidance and advice, I gained a greater understanding of the world of lighting design and what its impact could be on the architectural space.

I want to also thank those who have guided me through the ups and downs of the design and writing process over this last year, Mark Pasnik, John Ellis, Lora Kim, and Burcu Kutukcuoglu. Without them and their various expertise, I would never have reached a point with my project that I am happy with.

I would like to also extend my thanks to the greater Wentworth Architecture Faculty, without whom, my education would never have been as robust and generally excellent as it has been these last 5 years.

Finally, thank you to my friends, family, and loved ones, who, without them, I would never have had the support to continuously push myself and succeed in this wonderful field of architectural design I chose those many years ago.

Thank you all. I won’t let you down.

Chapter 1: Turning on the Light

Thesis Statement

Argument

Perception and Light

The Technical and Poetry of Light

Chapter 2: Reviewing the Light

Urban Spectacles

The Problem: Reclamation

Perception through Light

Technology of Light

Case Studies: Urban Lighting

Social and Cultural Contexts: Public Lighting

Conclusion: Reclaiming

Precedents

Criteria Map

Chapter 3: Finding the Light

Early Stages

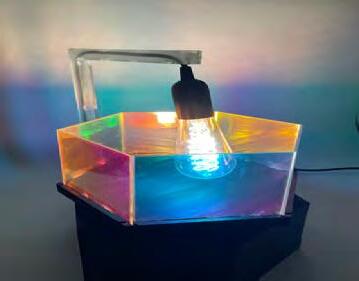

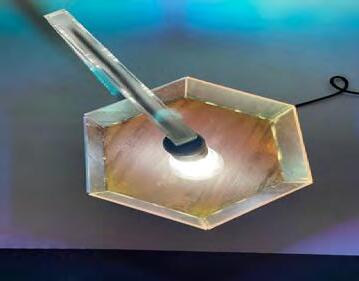

Small Scale Testing

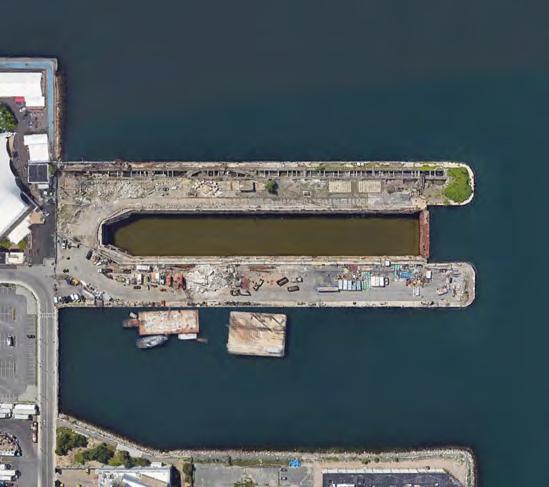

Looking for a Site

Analyzing Sites

Settling on a Site

Character Exploration

Testing Light

Material Testing

Precedents of Atmospheres

Lighting Objectives

Chapter 4: Beacon of Light Design

Exploded Program

Lighting Plans

Zoomed In Details

Seasonal Changes

Temporal Video

Chapter 5: Reflections of Light

Across the world, massive industrial remnants lie abandoned, creating various negative impacts on their surroundings. However, architectural lighting can transform these spaces into attractive and useful areas that benefit the public With the right lighting, these sites can be adapted to create a variety of atmospheres that enhance the movements and emotions associated with urban spaces. Through the reclamation of these industrial zones, we can create animated environments that energize our daily activities in a fun new manner.

Throughout the world, urban centers and countrysides have left abandoned industrial zones to rust and decay throughout. Perception of these spaces is tied to the loss of opportunities for what these mills and working sites used to represent. As architects, we have the ability to shift the perception of space through form and materials. Thus, we can be powerful advocates with a unique tool set of skills to reclaim and revitalize these castaway environments. For hundreds of years, we have been chasing control over our environments, a specific factor is the control over light. Through light, it shifts our visual perception of the world, yet it goes beyond just the visual spectrum. Light has the ability to affect emotions, movement, and senses of active vs. relaxed no matter if visual senses are engaged, it is a whole body experience. Utilizing light can be a terrific tool for the reclamation of these industrial sites, allowing communities to further utilize these places past just the sunlight hours, but also into the hours of darkness Softness and hardness, atmospheres

Perception has always been a fascination of mine. Architecture’s ability to shape people’s perceptions of space and affect their mentality beneficially is the end goal of any design process. When I was 12, I was diagnosed with a condition that tends to affect perception in young children, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome. It’s a rare issue that when stress levels are high, the mind alters depth and size within the visual spectrum, making people’s faces larger or hallways stretch. It’s a rare condition and while it tends to go away when individuals grow older, my experience with it has had a long-lasting impact on the way I think about perception. Perception is subjective, it changes for every individual per what they see and experience in space. Light is a way to shape that perception. In my academic career, incorporating lighting design has been confined to natural lighting. Artificial/controlled lighting elements have never been brought up through my years in Studio. My introduction to architectural lighting began in a course last fall taught by lighting designers from LAM Partners, a major lighting design firm in Cambridge, MA. The fact that architectural lighting was so different from anything else I have studied intrigued me. During that course, I had a unique experience of seeing a side of design I had not previously, where lighting was the focal point, and launched my thesis interests.

One of the very first conversations I had in my architectural academic career focused on the reality that adaptive reuse would be one of the foremost issues in the field. The cost, both economically and environmentally, of new construction contrasts the benefits of utilizing existing infrastructure and space that is already pre-existing. That conversation was one of many that led me down quite the road over the past 5 years. Now, I’ve come to understand that light and spaces needing reclamation have a unique relationship, one that I explore in these following pages. One that seeks to explore how through the use of architectural light, we can reclaim industrial zones in urban centers and return them to the public sphere, reestablishing

their previous historical standing, while also continuing their usage into the nighttime.

The phenomenon of lighting is a natural element that exemplifies surfaces and forms of architecture. The work of lighting designers goes far beyond illuminating a surface or a living space, it is about controlling the perception and emotions people have when they experience the built environment. A controlled lighting scheme can benefit the human body when used correctly, or harm if used incorrectly. Florence Lam, William M.C. Lam, Richard Kelly, James Turrel, and Jennifer Tipton are some of the most prominent lighting artists and designers who have made lighting design what it is today. Lighting design as a dedicated field has only existed for the last 150 years of all architectural history. With the invention of gas and electrical lighting being introduced into more and more cities, the abilities of lighting our cities and spaces have only grown as technology has developed. Modern-day LEDs are beyond their HID bulb counterparts. There is an obvious but fascinating fact about light that keeps being driven to this subject, “We cannot see a surface that does not have light shined upon it.” As architects, it is our job to incorporate such a pivotal design element into our work and craft it, so it benefits the communities of our projects. Lighting is a small but rapidly growing field of design. Our circadian rhythms are also dictated by light. Researching the effects of light on the human body has been a complex point of study that has only recently, in the last 20-30 years, been investigated in more detail past purely scientific and numerical values.

New technology has also increased the possibilities of lighting design to even greater heights. The introduction of LED (Light Emitting Diode) and OLED (Organic Light Emitting Diode) technology brings forth new colors and design formats that can be considered by designers. These devices are smaller than your traditional “light bulb” but can produce the same or more light, as well as have the possibility for RBG color spectrum to be emitted as well. LEDs

also benefit from greater energy efficiency than previous lighting technologies such as HID bulbs, up to 90% less energy is used by LEDs. Initially, lighting was treated as an engineering problem, not a human problem.

Today’s cities come alive at night more than at any other time in our collective history. However, urban planners still only plan for uses of spaces in the daylight; they neglect any nighttime lighting conditions and how such lighting can support the city’s nighttime. Night makes up half of the time we have across the world. The solution is not to just blanket public areas with floodlights, but rather to carefully craft the lighting design to highlight the city’s nature and promote safety and wellbeing for all.

Over half of all time, our cities are shrouded in the darkness of nighttime. Technology is allowing cities to be lit up more effectively and efficiently than at any other time in our history, allowing for more usage of public space to be invested in, beyond the hours of sunset. The pedestrian experience has gone by the wayside in car-centric urban design. Pedestrian access to areas of architectural intrigue should be encouraged and pushed for throughout our cities and communities. There needs to be a larger push from our architects within the field to design with a people-first mentality. It’s time for us to reclaim areas that have gone unused in both the day and extend their usage into the night.

Light, industrial areas, and reestablishment of space are the topics of my research with each being pivotal to the end goal, whatever that ends up being. With light, the scientific study of this field is very young, the last 10-30 years. Architecture has been slow to incorporate such research into itself. The different colors, hues, and levels of light have a wide range of effects on the human body that are still being studied. Industrial areas worldwide are similar, yet they are a part of architectural history that needs to be addressed more and is barely getting the attention it deserves. With more and more industries moving away from Western nations

due to corporations cutting “costs”, they leave behind graveyards of industrial sites that are in desperate need of redevelopment. Without it, they go unused and add to the pile of issues cities have. A few projects have attempted and succeeded in redeveloping these areas, where they utilize light and its effects to accomplish it all.

Testing these ideas is a complex issue. It’s about selecting the right site, determining the correct lighting to be used, as well as what that lighting is exemplifying about the space. My design tests have focused on scale, each increasing with the level I am working at and the intensity I am applying lighting ideology and architectural elements. As the design process has developed the work took leaps between iterations, yet always guided by a framework of “Lighting Objectives” that were essential to developing the lighting scheme that would best support the program of the project, while engaging the poetic qualities of lighting.

With those objectives constantly in mind, the outcome of the process would be a spectacular blend of architecture guided by lighting design to result in a project that works to bridge the sides of a river and community. This project uses the ideological best practices of lighting designers from around the world and specific lighting conditions to create a beneficial addition to the surrounding area and the city of Boston as a whole. This final production is but one example of what could be done on this site, however, its design and the work done put forth an ideology that should not be forgotten in the process of lighting.

The final part of this text deals with reflections. Based on the feedback received from critiques, where can one go from here? What would be the next steps to take this project to the next level and thesis to a greater height than it has ended on? These are but a few questions that could be answered through further analysis of reclamation through light.

Architecture is a constantly developing field, one that is not only limited to massive office complexes or residential developments. As architects, it is our duty to have our designs service the community through the projects we accept and the principles we follow in the design itself. Light is a fascinating factor in design, one that as technology develops, so does our control over its beneficial effect on people. Through the perception of the world, light shapes our visual experiences. We only have to understand and use it for the good of our cities, to better them through the use of beautiful and poetic architecture.

Figure 1.10 Perspective of Gathering space from design project on Old Northern Avenue Bridge site. Lucas Chichester, “Unreal Market Perspective”.

Figure 1.10 Perspective of Gathering space from design project on Old Northern Avenue Bridge site. Lucas Chichester, “Unreal Market Perspective”.

When light and architecture are combined, their effects are vast on the physical, social, and cultural landscapes of the cities and communities they affect. Light is a valuable tool that can be used to intervene at key points in cities and the design of new “urban spectacles”. Across the United States, industrial sites have been left desolate and abandoned, benefiting very little from the communities they are near and adding to the growing crumbling infrastructure of our cities and towns. Industrial zones are sources of amazing and intense structural marvels. Designers and architects such as James Turrell, William M.C. Lam, Jennifer Tipton, Florence Lam, Richard Kelly, Stine Louring Nielsen, and Susanne Seitinger researched the ability that lighting has to shape the spatial and urban environment, as well as having explored how this light can affect historical industrial areas. These creators possess a profound ability to bridge the divide between the phenomena of light and the necessity for redeveloping industrial sites. Varius project across the world in the past few years have utilized light to give new meaning to industrial zones, specifically Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park in Germany and the Steel Stacks Art Campus in Pennsylvania. Urban intervention is necessary at this juncture, and lighting is the tool that can reshape people’s perceptions of these spaces by bringing forth new ways to reclaim these sites through the preservation of history, a poetic eye to these structures of iron and steel, and finally, the beneficial use of these spaces for the public.

Since the early 1980s, there have been drastic changes in the production industry across the United States, leaving scatted abandoned industrial infrastructure across the country.1 These structures are often massive in scope and sites of severe environmental damage, having been unused and decaying for decades. The discussion about how to handle these abandoned zones has been going on for decades, with a 1996 document, “Industrial Site Reuse and Urban Redevelopment—An Overview” by Elizabeth Collaton and Charles Bartsch, as a concise summary of the issue. In this document, the authors speak about the dangers of having brownfields and abandoned industrial sites near our communities, with severe health and financial issues associated with leaving these sites undeveloped.2 Laws such as the Environmental Protection Act and Clean Air Act have contributed to the incentive for governments and corporations to clean up environmentally damaged sites.3 Redevelopment and reclamation of these sites are essential from a community understanding, and even more so, an environmental standing. Bridges are a subset of these underutilized sites, yet they have a vital role in forming connections on the road to reclaiming these industrial zones. Bridges are points of connection, allowing us to pass the natural (and at times unnatural) barriers in our cities and countryside. In a 2023 report by the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, 1 out of 3 bridges in the United States alone need to be repaired or replaced to avoid imminent structural collapse. From 2022 to 2023, the numbers across the board for bridges in “good” condition went down by over 1000, while others in “fair” condition rose by 2000, and finally, those in “poor” condition rose only by 500.4 With those kinds of present dangers with bridge infrastructure, intervention is necessary.

1 Colaton, 17

2 Colaton, 25

3 Colaton, 27

4 Biddau, 6

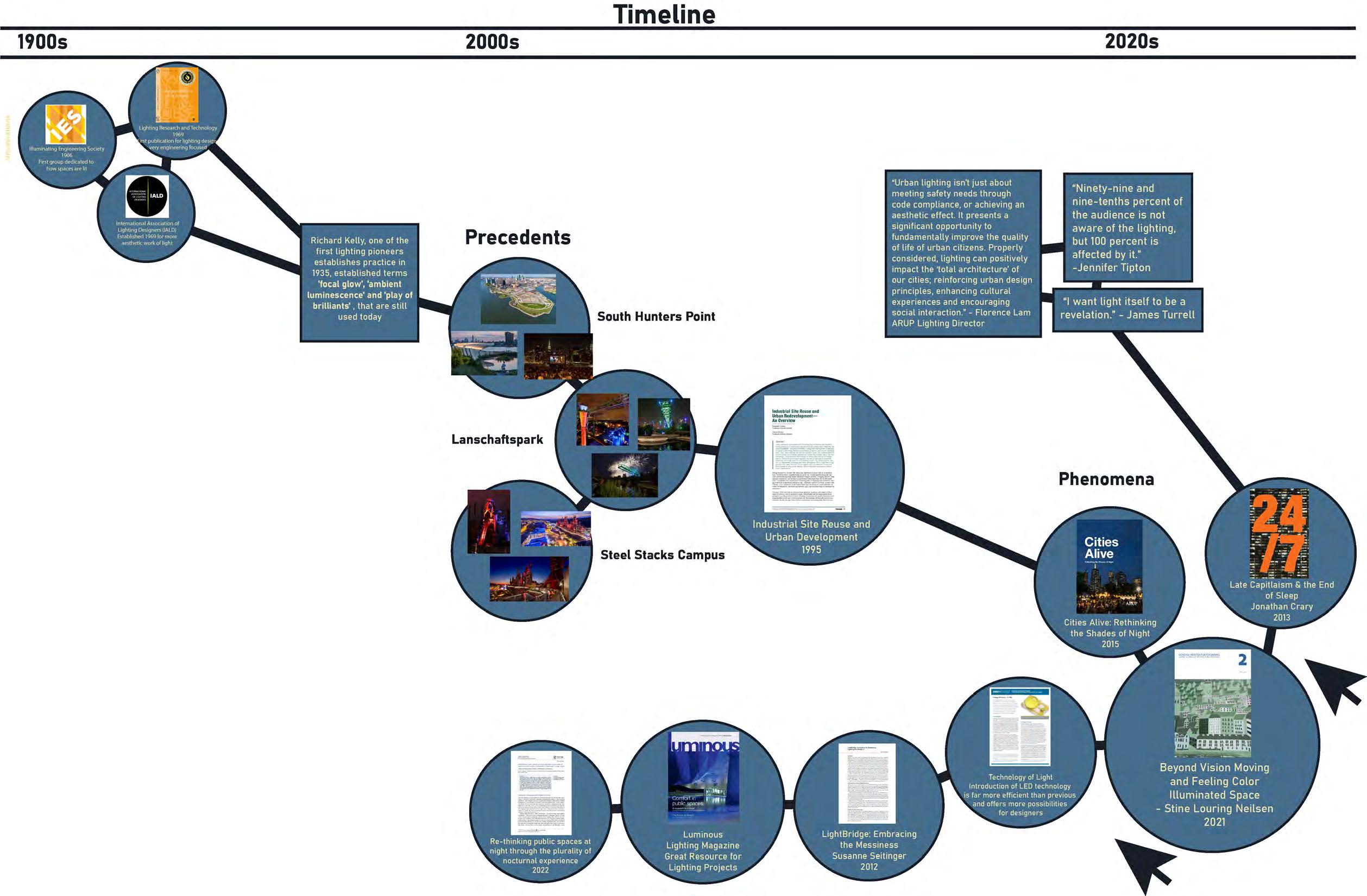

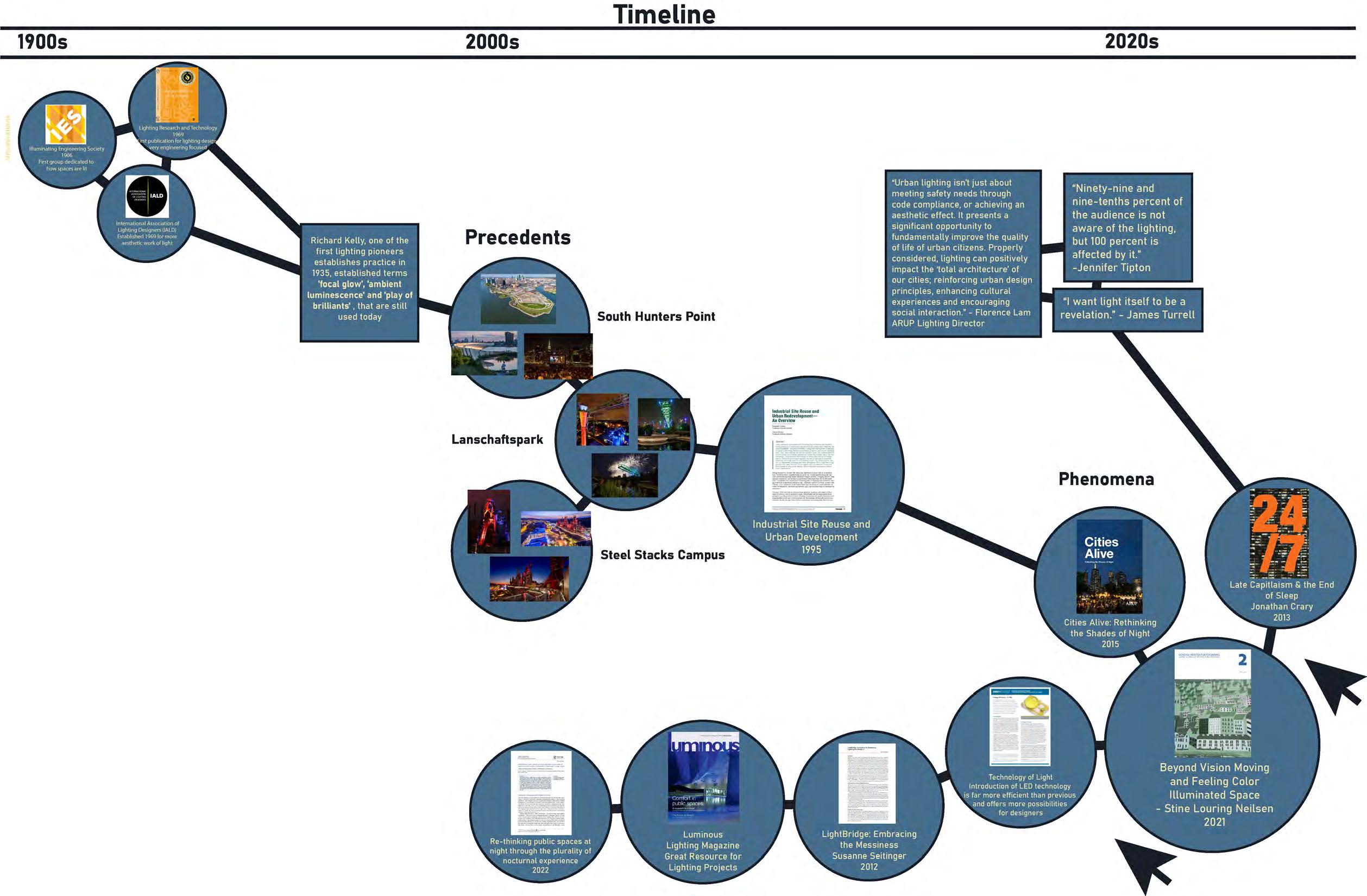

The study of light in an architectural, human-focused setting has only been a source of focus and study for a very short period. The lighting of space has had a considerable uphill battle when it comes to design for experience rather than for function. Since the late 60s, engineering organizations such as the IES (Illuminating Engineering Society) have guided lighting design into a technical corner, seeing the issue of lighting as an engineering problem rather than a human one. One of the first lighting designers to pioneer the switch to experience over function was Richard Kelly. When he established his practice in 1935, he created the terms for lighting design that are still used as a guide to this day focal glow, ambient luminescence and play of brilliants. Through his work with several “star architects” such as Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson, Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, and Eero Saarinen, his lighting concepts shaped the experiences and material palettes of these modernist architects.5 Kelly set off a decades-long battle between experiential and data-driven design.

William M.C. Lam was another pioneer in the world of lighting design. He questioned the over-engineering focus and numberdriven lighting of space. A key aspect of his research focused on perception and how that drove people’s experiences within architecture. Lam, to understand the intricacies of lighting’s effect on the body, studied psychology. He looked at work by James J. Gibson’s Perception of the Visual World where he came to an understanding that “perception is an active, information-seeking process, not a string of unconscious and mechanistic responses to external stimuli.”6 Perception “is not a passive response to patterns of light; rather, it is an active information-seeking process directed and interpreted by the brain…It is the information content and context of a stimulus, not its absolute magnitude, which generally determines its relevance and, finally, its importance.”7 Perception can be distracted (focused) by several aspects such as luminance dominance

5 Neumann

6 Lam

7 Lam, 35

and pattern dominance.8 Each of these strategies can bring an audience’s attention to a particular aspect of a building or space.

As architecture has become more complex and nuanced, it has allowed nontraditional designers to break into the space and make a significant impact on how spaces are perceived. Jennifer Tipton is one such artist who has leaped the lake that is architectural lighting design. Tipton has made a career designing theaters and stages, areas of high focus for audiences, where lighting matters most. She says, “Ninety-nine and nine-tenths percent of the audience is not aware of the lighting, but 100 percent is affected by it.” Tipton has an understanding of light that people and architects “understand” but they do not “know”. It affects us all and we know it when we see it, but there should be a greater understanding of it. James Turrell is a name that is constantly brought up in the world of lighting design. His work does not fall into just design, it is far closer to art, “I want light itself to be a revelation.” James Turrell’s art philosophy revolves around light, intertwining perception, spirituality, and human consciousness. Viewing light as a malleable material akin to paint he sculpts immersive environments, manipulating its intensity, color, and direction. Drawing from religious traditions, Turrell’s works transcend traditional boundaries, blending art with architecture to prompt viewers to reassess their relationship with the environment. Site-specific installations consider location characteristics, inviting engagement and challenging conventional static art perceptions, creating an effect of movement through the lighting experience of his art.

As technology improves the level of control people have over lighting has expanded exponentially. A study conducted by the architectural light researcher, Stine Louring Nielsen from the Copenhagen University of Architecture, details the effects of different colors of light on the human body. This study focused on the movements of participants and 8 Lam, 37

how they changed depending on the light they were shrouded in. The light colors that were used were white, blue, amber, and red light. Participants were both blindfolded and not blindfolded to see what effects there would be on all the human senses. There were 26 participants in the experiment, ranging from 1869 in age.

The observations of participants based on the kind of light they were exposed to ranged the emotions and movements they were able to accomplish/feel. In white light, their movements were described as fast, clear, sharp and/or geometric, with their mindset being described as in my mind and not my body like they could cut through things, had a reaction of a hurry, felt like being overtired or impatient, sensed a higher tone in my body or were searching for things but couldn’t find them.9 Red light movements were described as power, being in charge and/or more confidence and direction, with the attitude of, sensation of grounding, for example, manifested in an urge to sit down or participants feeling curious of the floor, heavy or pushed down.10 With Blue light the description from participants was silence, more space inside, feeling chilled out, dreamy, inwards, intuitive. Their experience was described as, feeling more tactile, emotional, fragile or separated from the space big, infinite, fresh and cold space.11 Finally, with amber light the descriptions for movement were, comfortable, energized, natural or neutral in the amber spectrum (A) of illumination, while the mindset was happy, care- less, content, strength, safe, good, free and content.12 This study and the work Stine has done convey that lighting is not just a visual aspect to design, but a whole-body experience for those within its effects.

LightBridge is one such project that utilizes existing infrastructure to better service the community through (unsurprisingly) light. Located in Boston, MA, this project uses LED screens along a bridge railing to create an intractable and adaptable lighting effect for this

public walkway. Created by Susanne Seitinger and Pol Pla in conjunction with the MIT Media Lab, their work looks to question the distribution of light in cities is often uneven and inaccessible by certain demographics. This work explored the ability of changes in light to be choreographed to fit different media messages and lighting conditions. Yet, Seitinger speaks to how the more tech, the more thought there has to go into what is being done in these places.13 This technology can be reactive, programmable, and even interactive, each with a different kind of human element integrated into it. The level of relevance of this technology must be taken into account at its inception, seeking to transcend temporal boundaries and adapt to future use cases.

When it comes to architecture, controlled lighting is a constant throughout all contemporary projects, yet the amount of design that goes into lighting varies greatly. Projects focusing on industrial reuse understand lighting above the average of other architectural fields. The Craiglinn Underpass is a beautiful example of lighting design with clear intent. An existing street underpass was prone to vandalism and had an intimidating aura through a lack of any lighting and accompanying dangerous street crossing overhead. This underpass has been transformed from a barely used husk to an element with lighting that, “changes color from dusk till dawn representing the various states of sunset, twilight, night and sunrise.”14 The designers, Bigg Design, worked with the local community to create a provocative example of bespoke lighting and a design that reflected the neighborhood around it.

Landscape Park Duisburg-Nord in Duisburg, Germany by Latz+Partner with lighting designed by Jonathan Park is one of the earliest examples of transforming industrial sites through the careful use of lighting installations. The goal of this park is to bring together locals into the space at night when the lighting installations are only visible. As with many 13

German parks that have been built since the 90’s, they are nature-conscious. This park offers a haven for a huge number of endangered and rare animals and insects. Its lighting has a low illumination to account for this. It brings people to the park as early as 5 PM in the winter, while being closer to 10 PM in the summer. Initially, the project by Park used colored lights, flood lights, spots, strip lights, and high-pressure gas discharge lamps.15 All of these were replaced however since 2009 with energy-saving LEDs that have reduced the cost of this project but also added more dynamic possibilities for the color changes. These lighting events happen regularly, attracting hundreds to thousands for their events. The rest of the site has been redeveloped to create a program that adds to the community around the site rather than remain sedentary. Duisburg-Nord stands as a shining (literally) example of the power of light to transform industrial sites into public good uses.

Inspired by Duisburg-Nord’s success, other projects such as the Steel Stacks in Bethlehem, PA stand to repeat many of its successes while creating a more historically conscious lighting scheme. With both projects, the lighting is meant to amaze and attract, yet the Steel Stacks made a conscious decision to restrain the color spectrum of their lighting conditions to red and blue, to reflect the historical inferno that once inhabited the repurposed steel mill. Events run nearly all day at the ArtQuest Center in front of the steel stacks, ending in the late evening to midnight or even later on special occasions. The designers Wallace Roberts & Todd and L’Observatoire

Intr. intended this to be a new city center for the area. This project refurbished the site and brought new meaning to an old steel mill. The lighting and architecture allowed this once derelict husk to breathe new life into the surrounding abandoned town of Bethlehem, PA.

15 Latz+Partners

2.9 - An image of one of the many lighting installation events that occur on site at Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park throughout the year. Thomas Berns, “Lighting Explosion”.

Figure 2.10 - Project done by Bigg Design, conveys ability of only light to create amazing visual stimuli to inspire use of spaces that often go underused or not used at all. Bigg Design, “Craiglinn Underpass”.

Figure 2.13 - A Night-time illumination over Biglen, Switzerland, depicting the light pollution present on the horizon.

Figure 2.13 - A Night-time illumination over Biglen, Switzerland, depicting the light pollution present on the horizon.

Now, more than any other time in the history of architecture, architects have a greater range of influence and scope on the urban environment. As that scope increases, the influence of public lighting on the public sphere grows accordingly. The ARUP design firm has produced a document that explores its approach to lighting design, offering an intriguing perspective. Thanks to smart technology, lighting design now offers a wide range of possibilities. It’s predicted that by 2030, artificial light will have increased by 80% globally, with LEDs and OLEDs leading the way. This document emphasizes the importance of human experience, focusing on both exclusivity and accessibility while promoting social and environmental sustainability.16 Furthermore, it’s worth noting that 18-27% of the workforce perform duties between 10 pm-6 am. To combat the “broken window theory,” this document highlights the importance of thoughtful implementation of lighting design to provide more amenities during the night and to enhance people’s perception of space at all hours of the day.

City lighting has been a point of urban development for hundreds of years. The desire to conquer the night has been a constant in our societies across the world. Some of the first recorded cases cited Greek nobles lighting oil lamps outside their homes. Throughout time this has expanded to where there is an inconceivable amount of electrical lighting throughout the world. Florence Lam, the lighting director for ARUP has stated, “Urban lighting isn’t just about meeting safety needs through code compliance or achieving an aesthetic effect. It presents a significant opportunity to fundamentally improve the quality of life of urban citizens. Properly considered, lighting can positively impact the ‘total architecture’ of our cities; reinforcing urban design principles, enhancing cultural experiences, and

encouraging social interaction.” When lighting is thoughtful, the effects can be profound and beneficial for communities and neighborhoods within the urban fabric. The experience of people must be tested and be in line with the beneficial needs of the area; if not, the effects could be disastrous.

Lighting is a complex system that when used incorrectly, can have negative effects on the urban and special environments it is being used upon. In the book, 24/7 – Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, the author Jonathan Crary outlines the dangers of overlighting and how capitalist society can erode the natural boundaries between the day and night. The text emphasizes the dangers of 24hour design, cautioning against its potential negative impacts. It highlights examples of cities designed with light as a tool and warns against the desolation caused by blurring the difference between day and night, work and reprieve, and the private and public spheres.17 The author expresses concern that embracing a 24-hour ideology could further erode our ability to break away from capitalist work ideals. In The Human Condition by author Hannah Arendt, she discusses the importance of maintaining a rhythmic balance between exhaustion from labor and regeneration within a domestic setting.18 Several texts are cited to support the idea that work and rest should be separated, with light playing a crucial role in this distinction. The text also mentions extensive research conducted by governments and corporations to keep people productive, often through manipulating light usage. It warns of the detrimental effects of prolonged wakefulness, stating that “being awake too long can drive you insane.” Ultimately, the text suggests that capitalism prioritizes productivity at the expense of individuals’ health, both mentally and physically.

As cities grow, the use of spaces becomes muddled, and without constant supervision, abandonment can and has become a serious problem in many cities and towns around the world, especially in the United States. When 24-hour design is brought up, it can be a benefit for cities when used correctly but it can also spell doom when used brazenly. Perception is key to understanding an environment, as William M.C. Lam outlines through his research and writings. The work of artists such as Tipton and Turrell pushes the boundaries of what lighting design means, furthering the possibilities for other designers in more practical, less artistic use cases. By reclaiming industrial site we can expand a locations potential, increasing their effect and creating a spectacle from them, one that benefits the community around them. Through the lens of lighting design, architects can utilize their abilities to reclaim the abandoned industrial sites next to our neighborhoods and communities, bringing them back into the realm of not just urban intervention, but further into an Urban Spectacle.

Figure 2.14 Perspective view of right wing, looking into the central section of my bridge intervention. Lucas Chichester, “The Light Wings”.

Figure 2.14 Perspective view of right wing, looking into the central section of my bridge intervention. Lucas Chichester, “The Light Wings”.