BOUTIQUE CAFÉ

The thing about living in a fast city like Lagos is that everyone is constantly asking what’s next? Which isn’t a bad thing, really; but more often than not, people fail to pause to admire the now, or even maybe try to look back to how far we’ve come. I think this is what makes Boutique Cafe so special. Nestled in the eyes of Adeola Odeku, this charming and ageless cafe carries the weight of nostalgia that Lagos so desperately needs, while inviting busy Lagosians to relax and escape the city’s traffic and bustle with its European elegance, warm brews, artisanal flavours.

At the entrance of this cafe is a cute little forest green door and an automatic sliding glass that feels like an entryway into your fondest memories. A quick look around and you notice so many fun antiques from different periods. A black and white tv, retro art pieces, books, and collectables from the different eras. The interior? Victorianstyle: plush velvet and European leather seating, ornate furnishings, patterned wallpapers, and dramatic colour schemes. An opulent ambience. Just being in the lower, upstairs, or smoking area feels like a warm vintage hug.

The menu at Boutique Café is everything! Compact but confident. Their all-day brunches are the perfect fuel or refuel for work for any coffee purist or newbie who prefers their caffeine softened with steamed milk. The entire beverage selection is expansive yet refined: Double Espresso, velvety smooth Caramel Lattes and creamy Cafe Mochas topped with delicate chocolate shavings. Feeling playful? The Dirty Chai Latte, Vanilla Beetroot Latte and ‘Kiss the Berry’ mocktail are cups of flavourful poetry. Bonus: Boutique prints vintage-style black and white portraits of guests on their takeaway coffee cups. Chic? Très.

Brunch here is hearty, honestly, punching far above what one might

expect. The Classic Nigerian Breakfast carries our familiar and comforting Nigerian flavours, but with European-style serving: the yam slices perfectly cooked with a buttery edge, paired with thick, rich egg stew, long golden plantains that are equal parts sweet, soft, but firm, and a playful mix of sausages and baked beans. Then there’s the American Morning Breakfast, a plate that belongs in a dreamy 1950s diner: pillowy scrambled eggs, crispy beef bacon, golden hash browns with just the right crunch, soft sausages, buttery French toast, and fluffy pancakes dripping with maple syrup like golden sunshine.

And then, the digital nomad and remote workers’ favourites: dessertfor-breakfast, flaky croissants, moist pound cakes, and colourful macarons that crunch gently before melting into sweet, almondy perfection.

From sunrise to moonlight, 7am to 10pm, Boutique Café feels like a well-kept secret you almost don’t want to share. The service and baristas are absolute sweethearts. Knowledgeable, patient, and always ready to walk you through a pairing, recommend a mocktail for your mood, or just make your coffee exactly the way you didn’t know you needed it. Whether you’re sliding in for a peaceful morning coffee, afternoon latte time, waiting out Adeola Odeku’s evening traffic, reconnecting with an old friend, or setting up shop with your laptop and something frothy, Boutique Café offers a rare kind of fond stillness and remembrance for a city that always asks “what’s next?”

Boutique Café

64 Adeola Odeku St, Victoria Island, Lagos Phone: 0915 136 0000 e: info.boutique.lagos@gmail.com IG: @cafeboutiquelagos

Special Spotlight

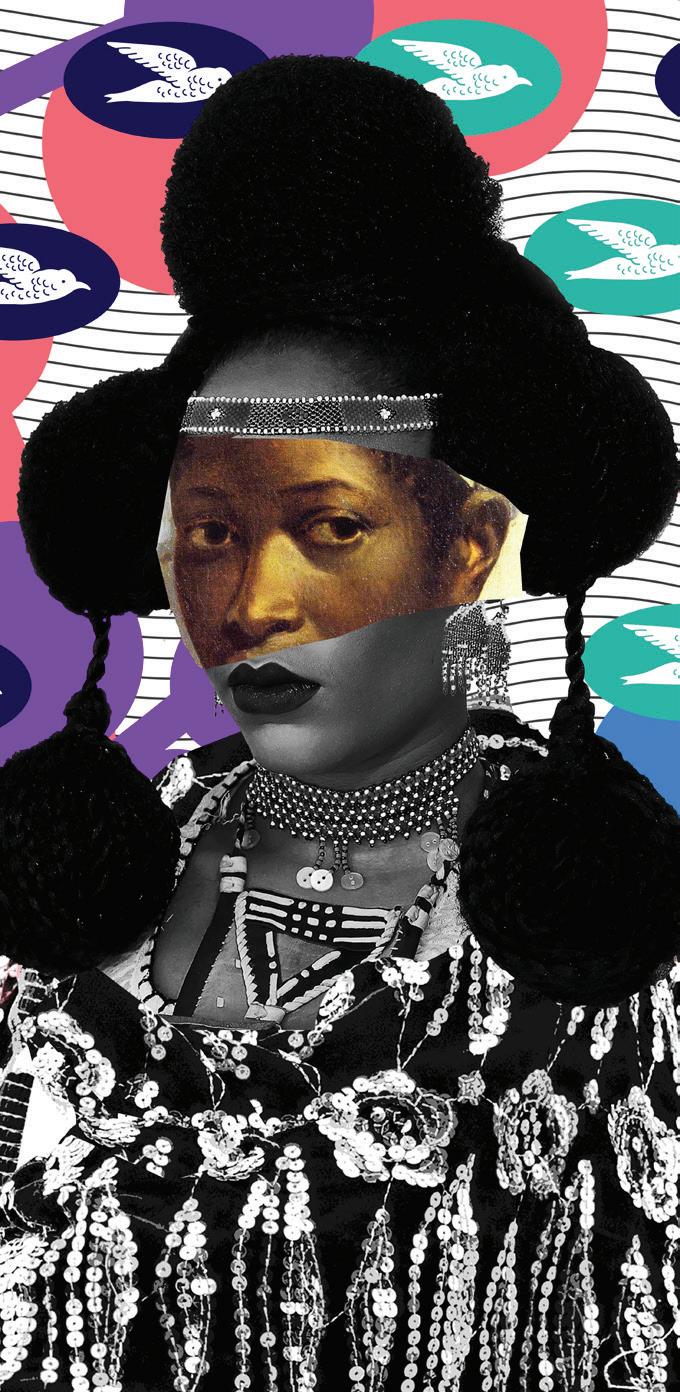

Late, Yusuf Adebayo Grillo Legendary Artist & Art Instructor

‘‘ Grillo believed an artist must be true to himself, and his creations must emanate from his true identity.

Tell us about Yusuf Grillo, what did he believe was the fundamental ‘power’ his art brought into a home or a public space?

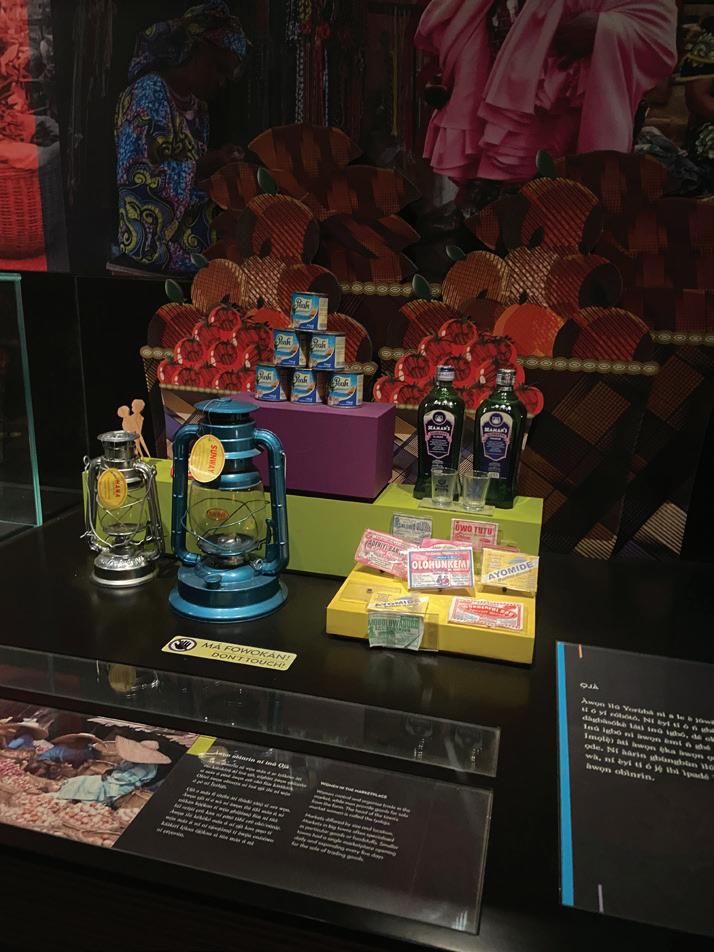

We present the enduring legacy of Yusuf Adebayo Cameron Grillo, a pioneering master of Nigerian modernism and a revered icon of Lagos, the city where he was born, raised, and lived his entire 86 years. His professional life, spanning over five decades, was a testament to an unwavering dedication to the intertwined passions of creating art and nurturing future artists. While serving as a distinguished and lifelong educator at the Yaba College of Technology, where he shaped generations of creative minds, his prolific genius simultaneously graced public and private spaces through a diverse range of media, including his signature paintings, magnificent stainedglass windows, intricate mosaic murals, and powerful sculptures. More than just an artist, Grillo was an institution builder, a beloved teacher, and a cultural custodian whose work remains a vital and celebrated part of our national heritage.

Yusuf Grillo saw art through the lens of his culture and environment. In the African context he embraced, art is not so much for its decorative factor, but more for its function. Art was used as an expression of spirituality (as in objects for worship and religious rituals). Furthermore, the patterns and motifs used to adorn textiles, stools, calabashes, pots, and other functional items of daily living were symbolic and best understood within the culture that created them. Therefore, Grillo believed an artist must be true to himself, and his creations must emanate from his true identity. Grillo saw the world through the lens of his ‘Yorubaness’ and expressed himself through the elements of that culture. Thus, his art brought the power of the Yoruba ethos to the homes and public spaces where it was installed.

How does the serenity portrayed by his art contribute to its power?

The serenity portrayed in his art is powerful because it is genuine. Grillo was committed to being true to himself, allowing the

canvas, the colours, and the brushstrokes to reflect what was truly within him. He was a peaceful and serene character; a stickler for truth, honesty, and unpretentiousness. These were the qualities within him as a person, which come through in his art and, by extension, speak to the audience of his paintings, evoking the same feelings in them.

How does the narrative power in his paintings contribute to the energy and conversation in a room?

He was a consummate storyteller. Whether speaking orally to his children and grandchildren or painting on canvas, there was always a backstory to evoke conversation among those beholding his pieces. His compositions were almost always based on his musings on Bible stories, Islamic literature, traditional religion, and the social life of the people in his environment. For those fortunate enough to have heard him explain his work, the depth of thought behind his portrayals is intriguing and becomes a catalyst for discussion. The questions and insights revealed lead to genuine learning experiences and cultural exchange.

How does cultural specificity become universal beauty, enriching rooms anywhere in the world?

His genius shines through in his ability to use his training in the classical, Western art of his colonial teachers and infuse it with his own cultural interpretation to create works that speak eloquently to both local and international audiences. Art itself is a powerful and evocative medium of communication that transcends cultural divides, which is why the looting of art as spoils of war was so significant, and the collection of art for pleasure and profit remains popular today. In this regard, Grillo’s work follows a long tradition of art that transcends its origins.

Three Works That Amplify Grillo’s Storytelling

of the market” or a young trader). Omoloja, representing COMMERCE, is depicted as an attractive young hawker, commonly seen hawking wares through the streets of Yoruba communities. The body language of these two figures, as captured by the artist, suggests their silent conversation is not merely transactional.

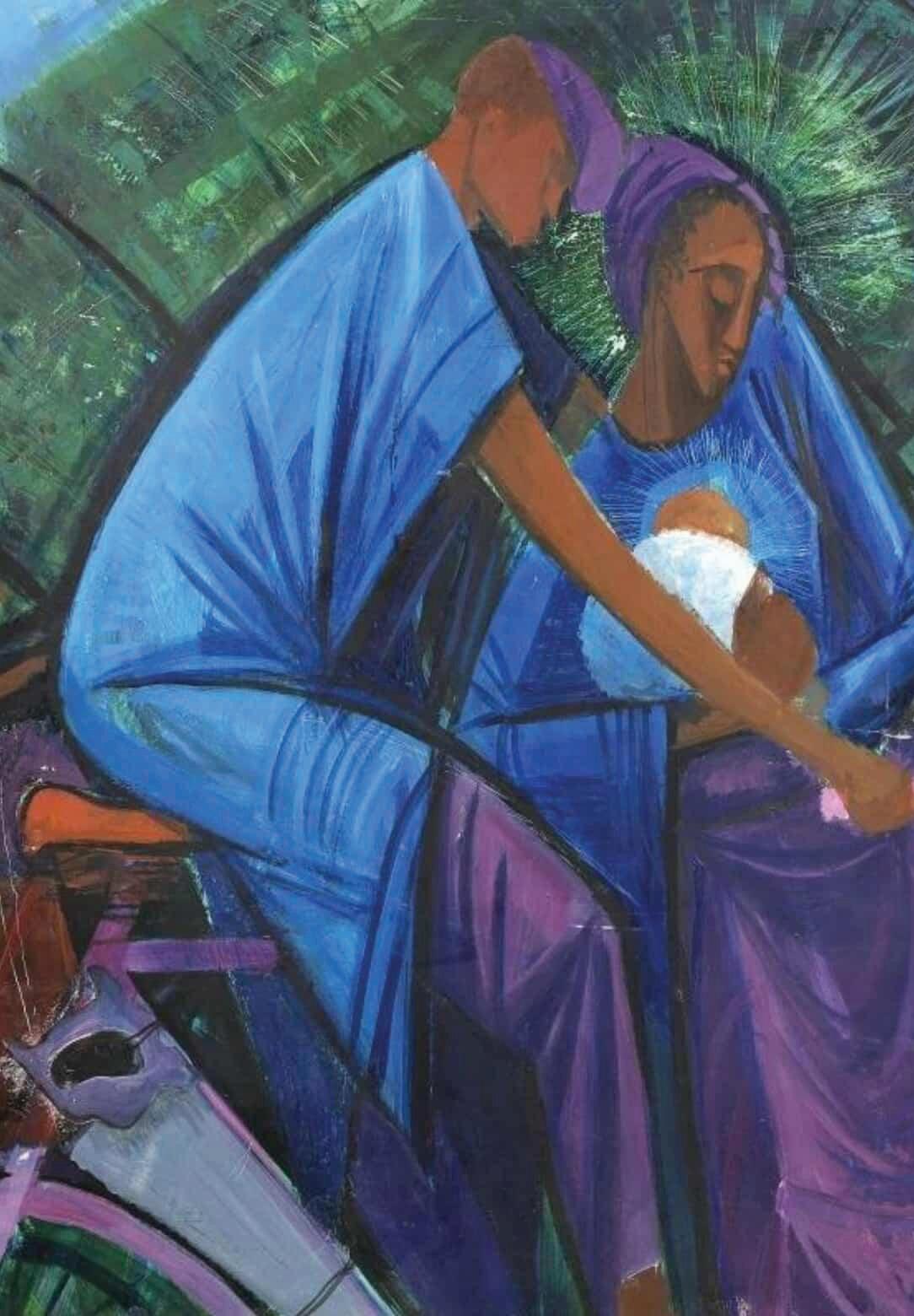

THE FLIGHT

This piece, created in 1972, tells how Grillo perceived the Bible story of the flight to Egypt of Joseph, Mary, and the infant Jesus to escape the wrath of Herod (Matthew 2:1323).

He depicts Joseph as a bicycle-riding Yoruba carpenter, with the tools of his trade hanging from the bicycle, and Mary cradling the infant Jesus while sitting on the crossbar. The figures are depicted in traditional Yoruba clothing and coloured in his favourite hues of blues, purples, greens, and burnt sienna.

MY TAIYE

My Taiye tells of the Yoruba love and veneration for twin births. Twins, in the Yoruba setting, were seen as very special children and venerated as deities. They are culturally represented by the Ère Ìbejì small woodcarvings thought to embody the spiritual essence of the twins. It was therefore a matter of serious spiritual import when one of a set of twins died. The mourning rituals involve having a woodcarving of the deceased twin kept in the household. It

Commerce and Industry (LCCI), now situated on the grounds Commerce House at the corner of Idowu Taylor and Adeyemo Alakija Streets in Victoria Island, Lagos. While fulfilling the brief for a sculptural piece to represent Commerce and Industry, Grillo’s sculpture tells the story of a love affair between Ṣokotí Ọrun), the heavenly blacksmith of Yoruba folklore, and Omo Oloja, the female trader. Ṣokotí, representing INDUSTRY, is depicted as a handsome, strong, muscular young blacksmith with the tools of his trade (anvil and hammer) visible. He is shown in a serious conversation with Omoloja appellation meaning “child

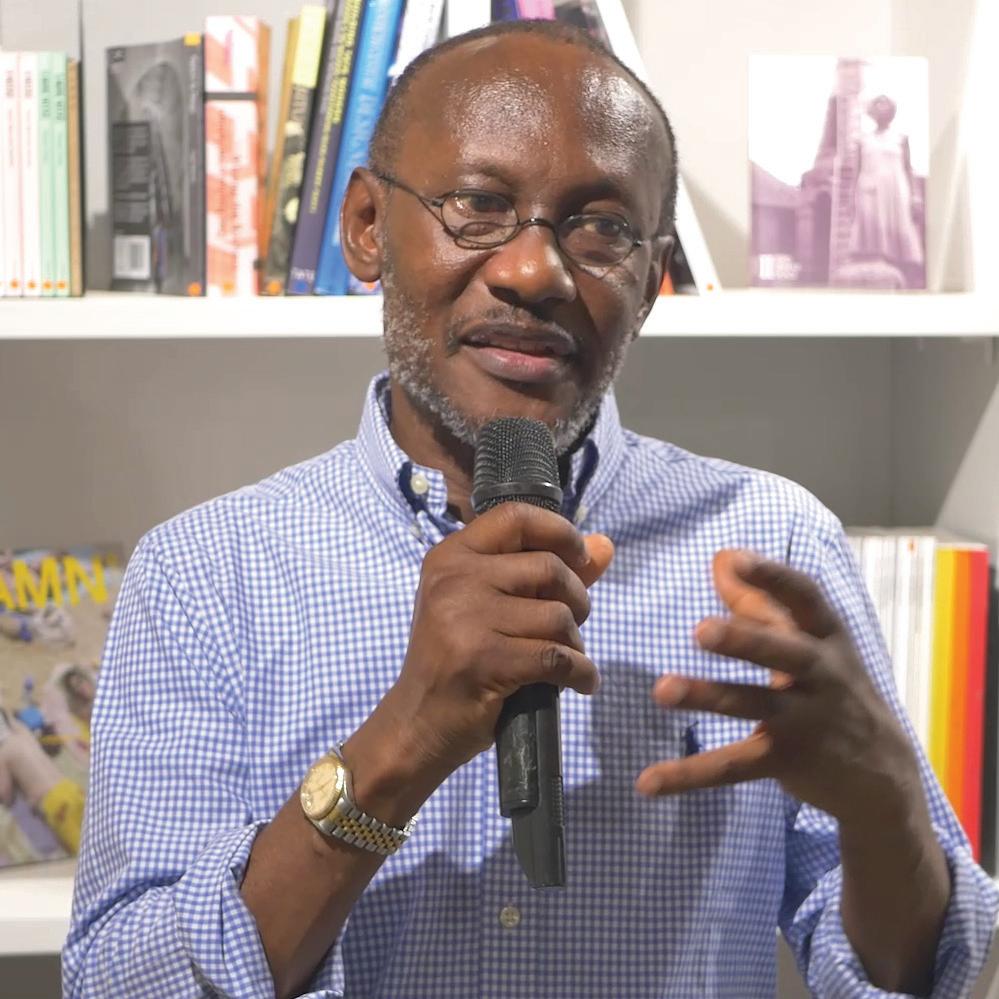

Interview

Tola Akerele

GM/CEO of the National Arts Theatre

Founder, iDesign & Soto Gallery Foundation

Convener, +234 Art Fair

Author, Orishirishi Cookbook

‘‘ Quality control is critical. If we want to take our work from local to international markets, we have to ensure we’re following best practices, especially when it comes to consistency and finish.

Meet Tola Akerele, a visionary whose work seamlessly weaves together culture through the vibrant mediums of food, design, and art. Her Afro-modern style, deeply rooted in sustainability, draws inspiration from local contexts while embracing global best practices. Across all her endeavors, Tola consistently champions cultural heritage, ensuring it shines through in a way that is both relevant and contemporary.

What does the “home” mean to you, not just as a designer, but as a Nigerian, a woman, and someone with such an expansive, layered career in the industry?

Home, for me, is where you recharge, it’s a space that brings peace. As a designer, I believe creating a home isn’t just about making something beautiful, it’s about how the space works for the person living in it. You have to take into account their lifestyle and daily rhythm. With my busy schedule, coming home is about having a place where I can truly relax and unwind. It needs to feel like a sanctuary. No matter who you are or what you do, your home should reflect your personality, it should hold space for who you are, and allow you to feel completely at ease. We also like to host people over, so spaces that are fluid, some entertaining space is super important. A home should adapt to both rest and connection.

Your work, synonymous with layered storytelling through space, is always iconic. How do you approach design as both a visual and cultural archive?

I think iDesign gets approached because of the way

we design. We’re very intentional about turning each brief into something that truly reflects the purpose of the space. Whether it’s a restaurant, a hotel, a home, or an office, we focus on how people will interact with that space. We don’t do copy-and-paste design. Each project is carefully thought through; who is the space for, how will it function, and what makes it unique? We’re always thinking about the context: why the space exists, who it serves, and how best to bring that story to life. That level of consideration shows in our work. It’s distinctive because our approach is rooted in meaning, originality, and a deep sense of place.

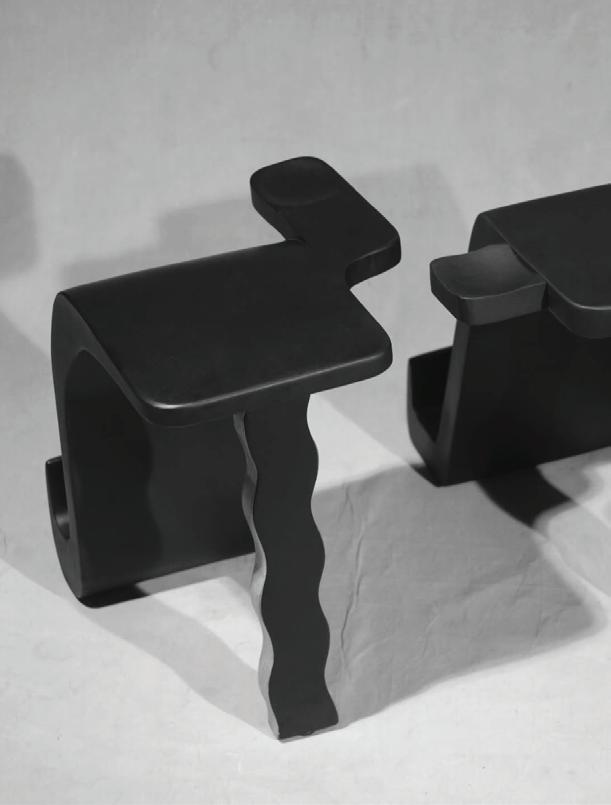

You’ve consistently championed local artisanship and Nigerian materials. What systems do you believe we need to institutionalize to support the design value chain; from the roadside carver to the export showroom?

I think what we really need to strengthen the design value chain is investment in research and training. Since I moved back to Nigeria, I’ve worked with a small team where we produce bespoke furniture made from wood. What I’ve seen is that we have incredible natural talent, people with raw skill and creativity but they need the right tools, training,

and infrastructure to scale and compete on a global level. Quality control is also critical. If we want to take our work from local to international markets, we have to ensure we’re following best practices, especially when it comes to consistency and finish. When I speak about research, I mean really understanding and expanding the potential of our local materials. Take bamboo, for example. Countries in Asia have invested in research to develop bamboo into flooring, cutlery, plates, everyday functional products. Meanwhile, we’re still using bamboo in its raw form for basic furniture. There’s so much more we could be doing if we invested in material research. It’s the same with our textiles and other textures, we have such rich resources, but we haven’t fully tapped into their potential. We also need more dedicated design schools; that’s a major gap. It’s difficult to grow without formal institutions supporting the ecosystem. Product design, in particular, is such an important part of the design conversation. Learning how to create for global markets, and how to produce functional, context-inspired pieces. Right now, we’re limited by the lack of structured education and training in that area. The good thing is that we do have a growing market here that could help fund research and development. If we build systems that support artisans from the roadside carver to the high-end export showroom, we’ll start to see real transformation in the design ecosystem.

With +234Art you have spotlighted over 200 artists, what have you observed to

be the biggest roadblocks for emerging Nigerian creatives, and how can they be overcome?

One of the biggest roadblocks I’ve seen is limited visibility and access. Many talented creatives from places like Nasarawa, Ebonyi and other parts of the country just don’t have the platforms to show their work. With +234Art, we’ve tried to address that by creating a space that brings new artists into the conversation and grows the art market at the same time. The market here can be small, with just a handful of collectors, so a big part of what we’re doing is expanding that base and making the ecosystem more sustainable. Beyond visibility, we also run training and programming helping artists understand their role in the local, regional and global art scenes. The international art market is a multi-million dollar industry, and our artists should absolutely be part of that. We’re now looking at how to do even more capacity building outside of the fair so things like artistic research, understanding the market, career planning, and longevity. All of that is necessary for artists to thrive not just now, but in the long term.

Soto Gallery has played host to critical conversations and art shows. What role do you believe art galleries should play in civic life, and how can they move beyond being just elite spaces?

I believe galleries should be spaces where people feel welcome, not intimidated. That was one of the reasons we started +234Art

in the first place. We wanted people to feel free to walk in and engage with art, without feeling like they needed prior knowledge or special access. Galleries should encourage dialogue and be open spaces for discovery. At Soto Gallery Foundation, we run various programmes that reflect this belief. For example, The Art of Collecting is one of our initiatives focused on helping people understand what it means to be a collector not just from a transactional point of view, but from a place of genuine appreciation and cultural investment. Beyond exhibitions, we’re also exploring how art intersects with other disciplines. In October, we’re hosting a conversation around art and health exploring how creativity can support mental and physical wellbeing. Art is incredibly powerful and inspirational; it shouldn’t be confined to gallery walls. It has the potential to spark civic dialogue and bring people together around issues that matter. Another key role galleries must play and one we take seriously is artist development. We work closely with a few artists because we understand the time and care it takes to support a creative career. From securing residencies to facilitating international shows and getting the right kind of exposure, it’s a long-term commitment. Globally, this is a traditional role galleries play, and I think we in Nigeria need to do more in that space.

Most underrated piece of advice you’ve received as a creative entrepreneur?

One of the most underrated pieces of advice I’ve received is to start where you are and with what you have. It’s easy to get caught up waiting for perfect conditions; more funding, the right team, a bigger platform but I’ve learned that consistency, resourcefulness, and staying true to your values will always open doors. I think when you create with intention, even in small ways, people take notice. That’s been my experience whether it’s working with local artisans, launching +234Art, or designing a space, you just have to begin. Everything else tends to align in time. It’s also really important to know your ‘why’. Knowing your why helps you articulate your how. It keeps you grounded when things get tough and helps guide your decisions, especially in a space as fluid as the creative industry. Once you’re clear on that, you’re not easily swayed and that clarity becomes part of your strength.

For young Nigerians looking to build culturally rooted, commercially viable businesses in art, design, or hospitality, what would you say is the most important first principle to hold on to?

I think to run a business in Nigeria today, especially in the cultural space you have to be extremely tenacious. It’s not an easy environment, so while passion is important, it can only take you so far. What really sustains you is understanding the fundamentals of business. Even though you’re building something creative, you still need to know how to structure and run it properly. I think my financial background helped me in that regard, and I always encourage young people not to shy away from the business side of things. It’s what allows your creativity to thrive in a sustainable way.

Interview

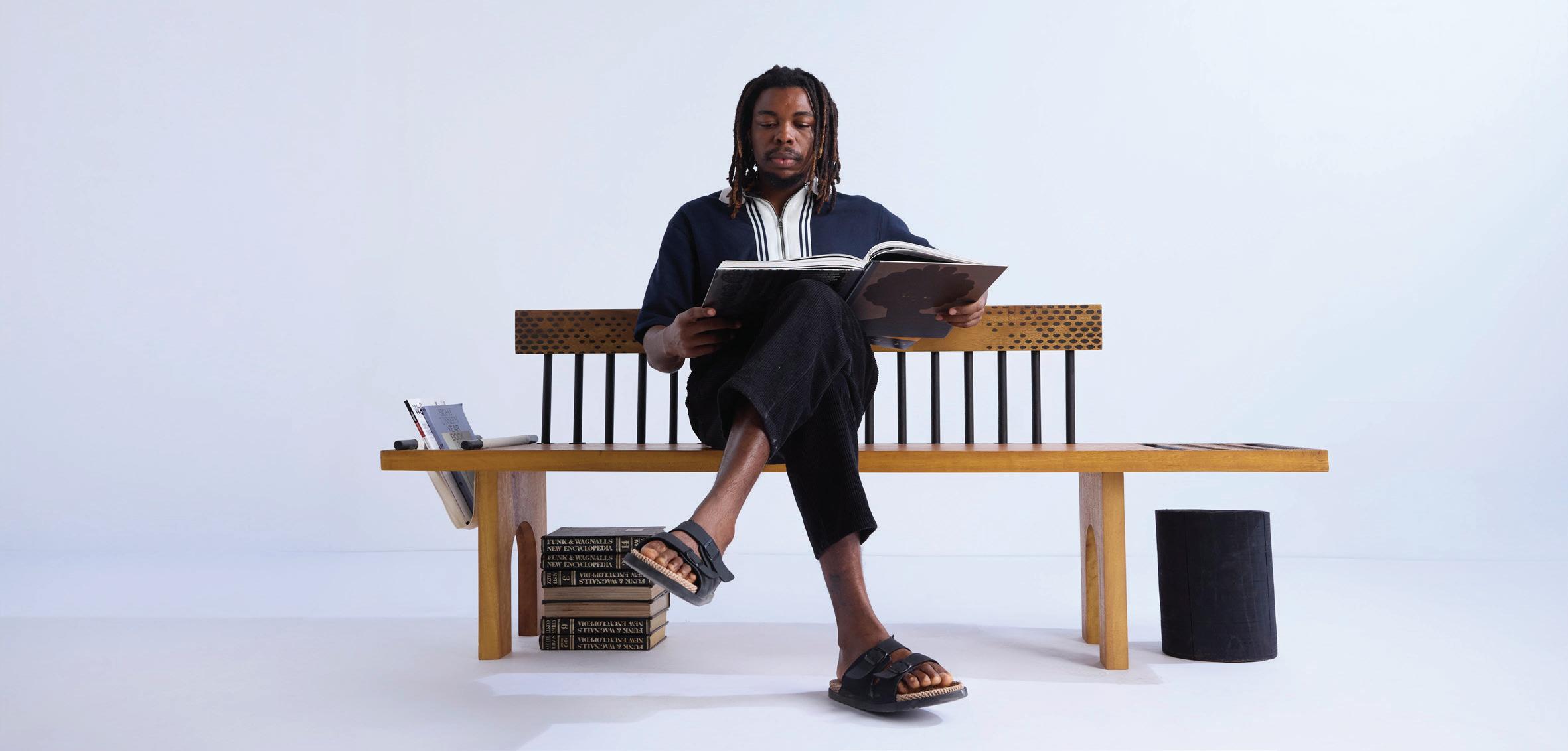

Chuka Ihonor Founder, ARG Studio, Ci Studio, 9H Media, & OKA4

Meet Chuka Ihonor, a visionary architect and designer who honed his craft at University College London before making an indelible mark on Nigerian architecture. He masterfully blends Modernism with the rich heritage of Nigerian lifestyle, particularly the Igbo Courtyard and Compound House model, through his acclaimed practice, ARG Studio. Beyond architecture, Chuka’s creative empire includes Ci Studio for bespoke objects, 9H Media for design-focused audio/visual content, and the forthcoming OKA4, dedicated to showcasing furniture and lighting by predominantly Nigerian and Black designers.

You’ve had a multifaceted impact across architecture, design curation, and urban discourse. What would you say, make you choose everyday to do the work you do?

The thing is that if I wasn’t an architect, I’d have been an Economist just like my father who studied at LSE (so we both attended University of London). But I always knew it would be design; I have drawn cars and houses ever since I can recall. I live for the world of design; the creation of new things, the journalistic side of it, writing books, and reaching out to universities and students of design in Nigeria and the UK.

You’ve long championed context-driven design. What’s the biggest misconception Nigerians have about architectural value when it comes to building homes and residential properties?

Nigerians hardly understand the work of the architect; they do not appreciate the enormity of the thought processes that go into creating architectural structures, and consequently almost never pay fees commensurate with the work they receive. Tied to this are the designers themselves, many of whom produce work that utilises little or no hard work, graft and thought. Clients who have the money are now turning to foreign architects for more exciting work, but this also backfires when the architect in question is no better than those you are running away from.

True value comes from design that not only solves problems, but creates a whole new world in itself. Inspiration from stories, from traditions, from the culture of the time and of the past, the use of, and manipulation of space and spatial hierarchies of past and present building traditions. Abstraction. These are the hallmarks of the best design work. Designers and clients ought to start to take these things seriously.

Through Ci Studio and ARG, you bridge design with community,

research, and policy. In what ways do you think policy and regulation must evolve to support better, more sustainable urban housing in Nigeria?

Nigeria is totally unprepared for a debate or any progress regarding affordable housing; nothing is in place to even start the conversation. Much more important to those in power is getting rich [quick]. There is no manufacturing base, so no supply chain. No hurry to address any of the issues that will help steer the way to the realisation of a plan for more housing. The cities and towns especially aren’t even properly designed and managed; without an urban plan, talk of housing policy is merely wishful thinking. Exactly where in a city do you build these structures?

What are three design interventions, big or small, that Nigerian homeowners and developers can embrace now to make more thoughtful, livable, and climate-conscious homes?

People will always build what they like; without their own money. Only a very small percentage are design-savvy and understand how design could solve problems. As an architect, I never set out to make a building fit into a type: climate conscious, sustainable, etc. Through design, these issues are silently tackled without typecasting the building.

There’s a growing interest in alternative building systems and local materials. What’s your take on the practicality and scalability of these trends in Nigeria today?

Using local materials is good; it helps to create a local industry. Beyond that, there’s the issue of the appropriateness of material to function, or to structure. Technological advancement has meant that you could build certain structures cheaper with certain materials; how then do you force the hand of the designer or client to only use that which he digs out from his locale? At what scale could local

‘‘

Nigeria is totally unprepared for a debate or any progress regarding affordable housing; nothing is in place to even start the conversation. Much more important to those in power is getting rich [quick].

material be used for larger, taller structures? What new applications can be achieved that rival the coming of reinforced concrete and steel? We can dream, but we must work towards realising progress.

For someone designing a home today in Lagos or Abuja, what should they absolutely not compromise on, and why?

Clients and developers should place a premium on design; they should attend design events, read up on design, listen to their designers and get their money’s worth (for those who actually pay). The rate of default on payments to consultants is alarming; there is an epidemic of scoundrel clients in the highest places who do not pay their bills, and I am considering exposing a few of them. It is inhumane, wicked, evil and at best, uncivilised.

What advice would you give a young architect who wants to operate not just as a designer, but as a civic voice and cultural advocate?

A true brilliant architect would be a cultural advocate; they go hand in hand. The richest designers are not necessarily the brilliant ones; far from it. So I am not referring to them. The true brilliant designer wants to teach, wants to galvanise others in the professions to move forward as a collective. They do not serve on the altar of the client’s whims and caprices; they teach the client. Many, sadly, are tutored by their clients. Isn’t that such a shame!

Interview Anita Oghenevwede Precious Creative Director, Noni Design and Noani Home

What do you see as the biggest misconception Nigerians have when it comes to designing the interior of their homes?

One of the biggest misconceptions Nigerians often have about interior design is that it should be cheap. There’s sometimes a lack of understanding of the value that thoughtful design brings not just in terms of beauty, but in how it enhances the functionality, comfort, and long term value of a space.

People often underestimate the cost of quality materials, skilled labor, custom furnishings, and the time it takes to properly execute a project from concept to completion. Alongside that is the belief that interior designers are simply offering a free service, almost like decorators who come in at the end to “arrange things nicely.” In reality, we are problem solvers, planners, creatives, and project managers all in one. We’re involved from the early stages, working through technical drawings, spatial planning, mood direction, sourcing, and coordination. It’s a service that requires not just talent, but deep expertise, experience, and emotional intelligence. Good design saves time, reduces costly mistakes, and transforms a house into a home and that kind of transformation requires investment.

Meet Anita Precious, the founder and creative director of Noani Design, a Lagos-based studio specializing in cozy luxury interiors. With nearly a decade of experience, she masterfully blends storytelling and cultural richness to create spaces that are not just beautiful, but deeply personal sanctuaries. Anita transforms both residential and commercial environments, infusing each project with an otherworldly and emotionally resonant energy.

What are some creative and budgetfriendly ways to incorporate artistic elements into a home without necessarily buying expensive fine art pieces?

There are so many beautiful ways to bring artistic elements into a home without spending a fortune on fine art. One of my favorite approaches is using fabric and textile art frames or even vintage scarves that can add so much personality to a space when displayed creatively. Wall baskets, ceramics, and locally crafted items also tell a rich story while supporting artisans.

Another great option is creating gallery walls

‘‘ When home, art, and design speak the same emotional language, the result is always harmony.

using personal photography, handwritten notes, or pages from meaningful books and magazines. You can even play with abstract paint techniques on blank canvases for a DIY statement piece. Oversized mirrors, sculptural lighting, and decorative objects can also act as art when styled intentionally.

Could you walk us through your process of harmonizing home, art, and design for a client? Where do you start, and how do you ensure the three elements work together seamlessly?

I always start by understanding the client, their lifestyle, emotions, and what they want their home to feel like. From there, I build a mood board that captures their essence, blending design elements with textures, colors, and cultural references that reflect who they are. Art is never an afterthought. Whether it’s a commissioned piece or a personal item, it’s integrated early so it complements the design, not competes with it. I focus on balance, scale, lighting, and color to ensure everything works together seamlessly. The goal is to create a space that feels personal, intentional, and timeless. When home, art, and design speak the same emotional language, the result is always harmony.

Let’s talk interiors! If you could only pick five magical spots in Nigeria to source pieces that truly make a home come alive, where would you go?

Nigeria is full of incredible places to source soulful, stylish pieces that bring a home to life. If I had to pick my top spots:

Nike Art Gallery Lagos, A haven for art lovers and culture enthusiasts. Beyond paintings, you’ll find handcrafted textiles, sculptures, and woven pieces that infuse depth and identity into any space.

Luxe Demi Lekki Phase 1, Known for its curated, high end décor and furniture, Luxe

Demi offers timeless pieces that feel both luxurious and affordable.

BoConcepts Victoria Island, Perfect for clean, contemporary furniture with a European flair. Their pieces add a sense of calm sophistication and work beautifully when mixed with more textured or organic elements.

Kitchen Accessories Lagos, A go to for elegant homeware and finishing touches that elevate your styling. Their collection includes everything from accent kitchen accessories to refined furniture that completes a room.

Iponri Market Lagos, Ideal for sourcing rich fabrics, curtains, upholstery, and soft furnishings. It’s a place where texture, color, and personality come to life.

If you could give one piece of ultimate advice to a Nigerian looking to build their dream home, what would it be?

If I could give one ultimate piece of advice to a Nigerian looking to build their dream home, it would be this: start with how you want the home to feel, not how you want it to look. So many people begin

with aesthetics, but the most timeless and fulfilling homes are built around emotion and lifestyle. Think about the mood you want to walk into every day. Do you want it to feel calm? Joyful? Inviting? Empowering? Let that emotional direction guide everything from layout to lighting, materials to colors. When the design is rooted in feeling, it becomes personal, functional, and deeply satisfying. And of course, surround yourself with the right professionals, people who understand your vision and can translate it with both creativity and structure. That’s where the real magic happens.

Adeyemo Shokunbi Architect and Co-Founder, PatrickWaheed Design Consultancy

‘‘ I have always seen home as the first architecture we encounter. It is the space that teaches us how to navigate the world.

Meet Adeyemo Shokunbi, a UK-trained architect whose work is deeply embedded in the cultural and environmental context of Lagos, Nigeria. He is the co-founder of the acclaimed firms Patrickwaheed Design Consultancy and NANA Collective. Across a range of residential, public, and cultural projects, his guiding philosophy is to create architecture that is quiet, honest, and intentional. Adeyemo’s design philosophy is centred on deep listening to context, climate, culture, and people, aiming to create architecture that expresses the environment rather than merely impressing. This approach has evolved from a restrained simplicity that emphasised form, light, and material to an intentional use of local materials like laterite for both aesthetic and functional reasons.

What does the ‘home’ mean to you, not just as an architect, but as a Nigerian, a citizen, and a curator of space?

Home, to me, is where identity is nurtured. It is where memory lives and meaning is embedded in the everyday. It is more than a structure. It is a place of belonging, of grounding, of quiet dignity. As a Nigerian, home carries emotional and cultural weight, from the shared rituals of daily life to the deeper need for safety, warmth, and continuity. As an architect, I have always seen home as the first architecture we encounter. It is the space that teaches us how to navigate the world. It shapes our values, our sense of comfort, and our way of seeing. But lately, the idea of home has become even more personal.

I recently designed a home for my mother, a deeply personal collaboration with my siblings, to mark a new chapter in her life as she turned 80. It became a way of honouring her, of creating a place of refuge and quiet for her to live out her later years in comfort and grace. I gave it everything. Not as a project, but as an act of love. A modest haven, curated with care, intention, and memory. As a curator of space, I believe “home” should reflect the spirit of those who inhabit it. It must hold the past gently, serve the present thoughtfully, and stay open to the future. Whether through filtered light, material texture, or spatial rhythm, the home is where architecture becomes most human and most sacred.

As someone who works across public,

residential, and cultural spaces, how does your approach shift depending on the type of project, and what constants always remain?

I try to approach each project with a fresh set of eyes. Public spaces often require more openness in thinking. You are designing for many people, most of whom you will never meet, so the space has to be intuitive and accommodating. It is less about personal taste and more about how people move through it, how it supports gathering, waiting, passing through, or simply being. Residential work is more personal. You are dealing with people’s lives most immediately. It is about understanding how they live, what they value, and how space can support their day-to-day reality. There is often more back and forth, more listening, and more adjusting. That process can be very fulfilling because when it works, it brings real comfort and joy to the people who live in the space.

Across all my work, the guiding principle is a commitment to honesty. I strive to create grounded architecture that serves people and fosters a sense of calm, rather than designing for mere effect. This approach is especially vital for cultural projects, which are layered with profound meaning, memory, and identity. In these sensitive spaces, my role is not to impose, but to listen to find what already exists and can be honoured or reinterpreted. The goal is to allow the building to breathe with its own story, expressed subtly through the texture of a wall, the quality of light, or the way

people are drawn to gather within it.

Many Nigerians still build without architects. Why do you think there’s a disconnect between everyday people and professional architecture? What must the industry do to fix this?

I think people build without architects for many reasons, and not all of them come from a place of disregard. For some, it is about cost. For others, it is about a sense of familiarity. They have seen buildings come up around them and believe they can piece one together too. Building is often seen as something anyone can do, and because people live in spaces every day, they feel they already understand how they should work. It is important to approach the disconnect between the public and architects with empathy. The truth is that the profession can often feel intimidating or overly formal, particularly when the design process is not explained clearly or when designers fail to listen. Understanding this perspective is the first step towards bridging the gap and making thoughtful, professional design feel more accessible to everyone.

The most successful projects are built on a foundation of mutual trust. When a client feels genuinely seen and heard, they are more willing to embrace the full creative process, leading to a richer and more collaborative outcome. This creates a balanced partnership where the architect provides expert guidance while empowering the client, the person who will live in the space, to help shape the final vision. The goal is shared ownership, blending a professional viewpoint with personal reality. Ultimately, the architectural profession has a collective responsibility to become more approachable. This means engaging more openly, speaking plainly, and showing the value of good design

without being defensive. The focus must shift from simply constructing buildings to fostering relationships, because trust is not granted by a title or qualification; it is earned through genuine conversation and a truly collaborative experience.

How can small and mid-scale developers implement high-impact design without high-end budgets? Any non-negotiables you would still insist on?

The truth is that most developers working at scale are under pressure to make the numbers work. I understand that. In this part of the world, the budget often takes precedence over everything else. That is the reality we are working within. But I have also learned that good design is not always about spending more. It is about making better decisions with what is available. We are selective about the projects we undertake, prioritising partnerships where thoughtful design is valued. If a brief is purely profitdriven and overlooks how people will live and interact within the space, it becomes difficult for us to contribute meaningfully. Our commitment is to clients who share our belief that architecture should serve the end user, which requires an approach that goes beyond simply maximising units.

Achieving high-quality design is not necessarily about a large budget, but about making intelligent, cost-effective decisions. We focus on resourceful strategies like optimising spatial layouts, maximising natural light and ventilation, and using durable, locally available materials. By simplifying construction methods and stripping ideas back to their essential purpose, we can deliver exceptional value and quality within realistic financial constraints. Regardless of the budget, there are non-negotiable principles we uphold: clarity of space, decent

airflow, and a fundamental sense of spatial dignity. People should never feel boxed in; they should feel that their well-being has been considered. This is achieved through care and intention, not added expense. When a developer shares this trust and focus, even the most modest projects can successfully blend beauty, comfort, and

minimalism to the adoption of traditional materials like adobe and laterite, how do you perceive the future of home design in Nigeria?

I am optimistic about the growing appreciation for design that is truly of our place. However, this shift must go deeper than just following trends or labels like ‘Afro-minimalism’. My core belief is that an architect’s responsibility in Nigeria is to create work that genuinely responds to our unique cultural, climatic, and social context. The ultimate focus must always remain on serving the people who will inhabit the spaces, not on chasing the latest terminology.

This philosophy demands that architecture in Nigeria be both grounded and practical, reflecting the realities of daily life. For instance, the use of traditional materials like laterite or adobe isn’t an aesthetic statement; it’s a logical decision. These materials are chosen because they make sense on multiple levels, environmentally, financially, and emotionally, offering solutions that are both sustainable and deeply connected to our heritage. By staying rooted in these principles of care and context, I believe the future of home design in Nigeria will become more honest, inclusive, and profoundly meaningful.

Interview

Olaniyi Israel Shina Lead Painter, Olshiz Integrated Concept Limited

M

eet Olaniyi Israel Shina, the lead painter and creative mind behind Olshiz Integrated Concept Limited, widely known as the Abuja Decorative Painter. A highly trained and certified professional based in Abuja, he specialises in providing expert solutions for wall defects to achieve a perfect, lasting finish on any interior or exterior surface. With a meticulous eye for detail and finesse, Olaniyi leads his competent team to deliver reliable, timely, and high-quality painting services, transforming spaces with skill and precision.

‘‘ One thing every tenant should know is that painting can improve their well-being and even their health.

You specialise in wall defect treatment before painting. Can you explain the most common types of wall defects you encounter in Abuja and how you fix them before applying paint?

One of the most common wall defects we encounter in Abuja is hairline cracks and damp issues. Most cases are rising damp, while others are penetrating damp. We have a device called a moisture meter, which we use to diagnose the walls to check the amount of moisture trapped inside and determine the water level. This helps us to select the right materials to provide a solution.

Let’s talk about material properties. What’s the difference between matte, eggshell, satin, and gloss in terms of durability, cleanability, and aesthetics?

These are all quality paint types; the best choice depends on the final feel an individual desires.

Matte: This finish is often described as ‘cool’ and ‘warm’. It can hide imperfections on a surface and can help create a calm space.

Eggshell: This finish is smooth and calm. It requires thorough surface preparation for a perfect result and does not have the ability to hide undulations or imperfections.

Satin: This is a highly shiny and bold finish. It also requires thorough surface preparation for a good result.

Matte and satin finishes are cleanable, but not highly washable. Eggshell is highly washable, and gloss is also wipeable. Overall, matte, eggshell, and satin are excellent choices for both residential and commercial surfaces.

Can mixing different brands of paint affect the final outcome of the job, supposing one finishes halfway through?

Yes, it can affect the outcome of the job. Every paint brand has its own formulations and properties. The pigments are not the same, nor is the expected colour. The quality of raw materials used also differs. Therefore, mixing brands can negatively affect the outcome of a painting job, especially if quality is compromised.

Some walls in rental homes feel really rough or patchy underneath the paint. Is that a bad paint job, or is it deeper than that?

It is often a deeper issue than just the paint. Surface preparation accounts for about 70% of the final result. This includes everything from the screeding materials and the abrading (sanding) process to priming the wall before applying the topcoat. These are essential steps for any paint job, but they are often ignored by many painters. If the surface preparation is poor, the paint will not adhere or look good, no matter how expensive or high-quality it is.

How important

apartment? For instance, if I’m not staying long-term, maybe six months to a year, should I bother, or is it only worth it for owners?

Screeding is a very important factor for any good painting job, regardless of whether it’s a rented apartment. What matters is the feeling you want to create in your space. The decision also depends on the individual’s budget and the quality of the ambience they wish to enjoy during their tenancy.

What questions should I ask a painter before hiring them, especially as a tenant who may not know all the technical terms? How do I spot a good painter?

To find a good painter, you should ask clear questions to understand their process. You could ask:

1. Can you assess the current condition of the walls and tell me what you see?

2. What treatment do you recommend for any defects you find?

3. What brands and quality of paint do you suggest for this job and why?

4. Can you walk me through the entire process you will follow, from preparation to the final coat?

5. What is the total area in square metres, and how have you calculated the quote?

A good painter will be able to answer these questions clearly and confidently, demonstrating their expertise.

Finally, what’s one thing every tenant should know about painting that most people never think to ask?

One thing every tenant should know is that painting can improve their well-being and even their health. When you live in a wellpainted house, it improves the ambience of the entire space, helping you to feel more comfortable. It is not a waste of money; it is a necessity for creating a pleasant home environment.

Nkechi

‘‘

Cleaning is a job many people look down on, yet it requires significant manpower.

M

eet Okoronkwo Nkechi, the Founder and CEO of Midas Touch Cleaning Services, a premier cleaning company based in Lagos, Nigeria. With four years of dedicated experience in the industry, Nkechi established the company in 2021 and has quickly positioned it as a trusted provider for both residential and commercial clients.

Let’s start at the beginning: what inspired you to launch Midas Touch Cleaning? Was there a moment or experience that sparked it all?

I would say money inspired me. I have always wanted to have my own business, and I sought something that felt personal to me because I knew the entrepreneurial journey would be hectic. I wanted to ensure I was doing something I truly cared about: transforming spaces through cleaning, whilst also owning a successful business in Nigeria. Starting Midas Touch helped me achieve both. Additionally, providing job opportunities and doing my part to help the economy were also major inspirations, among other things.

Running a business isn’t all sparkling floors and scented rooms. What’s been

one of your toughest challenges, and how did you overcome it?

One of my toughest challenges has been recruiting staff. Cleaning is a job many people look down on, yet it requires significant manpower. I have not overcome it completely, but one way I manage it is through networking. It’s about building a community of willing workers. When you meet one person, you build a relationship with them. In turn, they can bring in others, which helps us find people to do the work. So, that is one of the major challenges and how I manage it. Another challenge is logistics, mainly due to the traffic in Lagos, but we are managing to make it work.

What’s one underrated cleaning trick that always blows your clients’ minds? Perhaps the fact that you can use warm Coca-Cola to kill germs in your toilet. Many people are unaware of this, but when a bottle of Coke has been left in a warm room, it has the ability to kill germs on impact. That is one of the underrated tricks out there.

Kitchen stains, bathroom grime, and dusty corners, what’s your best hack for each of these common problem areas? Baking soda works for almost everything. Once you have baking soda in your house mixed with other ingredients, of course, there are very few stains it cannot remove.

It’s the one thing you would need for all three problems.

A lot of people struggle with keeping their homes clean consistently. What are five simple cleaning habits or hacks you recommend that can make a big difference, even for someone with a busy schedule?

(Note: The following answer provides one main habit.)

One thing I would say is to clean in small bits. Do not wait for messes to pile up; clean them right away. This way, you can keep your space relatively clean for a longer period until you have time for a deep clean. Letting dishes pile up, for example, only makes the task harder when you are eventually ready to tackle it. Cleaning in small bits is one thing that can help, despite a busy schedule.

What is something you want to tell the world about Midas Touch?

I want the world to know that our goal is to continue delivering premium cleaning services at affordable rates. We also aim to alleviate some of the stress of daily life in Nigeria. Taking that one task off your plate is something we are dedicated to doing. We will continue to improve and strive to become a force to be reckoned with in the cleaning industry.

Okoronkwo

Founder, Midas Touch Cleaning Services

Interview Lara Jarmakani Founder, Design Dot

‘‘ In creative industries, it’s easy to get distracted by trends or comparisons. But longevity comes from authenticity.

Take us back to the beginning. What was that “spark” moment when you identified the need for a platform like Design Dot, and what was the journey like bringing that idea to life?

The spark came from a frustration: I couldn’t find interiors in Lagos that felt truly considered or emotionally connected. And I couldn’t find designers from abroad who understood the realities of executing projects in Nigeria, from achieving quality finishes to meeting tough deadlines. So I began dreaming of a design studio that didn’t just decorate spaces, but translated personality and vision into environments that were both thoughtful and rooted in local understanding; a studio that could bridge creativity with practical execution. The journey started small: a sketchpad, a few passionate collaborators, and lots of

Meet Lara Jarmakani, the founder and Creative Director of Design Dot, a boutique interior design firm based in Lagos. Guided by the belief that design should transcend aesthetics, Lara leads her studio in creating spaces that tell a story, reflect identity, and enhance the way people move, live, and work.

bold ideas. But with every project, Design Dot began to take shape as a platform where thoughtful design could flourish, and where we could reimagine what modern design in Lagos looks and feels like.

How would you describe the evolution of the interior design industry in Nigeria, especially with the rise of new technology? What excites you most about how innovation is empowering designers today?

The interior design industry in Nigeria has grown tremendously, evolving from being seen as a luxury to becoming an integral part of how people approach lifestyle, wellness, and brand identity. Technology has been a huge accelerator in this growth, especially with the rise of social media platforms. Today’s clients demand more creativity and

attention to detail than ever before. Tools like virtual walkthroughs, material simulations, and even AI allow us to push creative boundaries while working more efficiently. What excites me most is how design is becoming more accessible, no longer reserved just for the elite. More people are engaging with design, and that’s truly powerful.

Building a business from the ground up is a monumental task. Was there ever a moment early on when you felt overwhelmed by the scale of the problem you were trying to solve? How did you navigate that challenge?

Many moments. Design is deeply personal, and you often carry the weight of your clients’ trust and expectations. In the early days, I felt overwhelmed trying to juggle creativity, logistics, and business management. What helped me was grounding myself in the “why.” Remembering that we’re not just designing pretty spaces, but creating impact, allowed me to keep going. Surrounding myself with a team that believes in the vision made all the difference.

For our audience looking to elevate their own spaces, the world of décor can be overwhelming. Could you share your expert insights on the most important things to note when looking for home décor?

Start with intention. Before buying anything, ask yourself: What mood do I want this space to create? From there, focus on quality over quantity. A few well-chosen pieces, whether it’s artwork, lighting, or a beautiful rug, will always elevate a space more than clutter. Natural materials and good lighting are key to timelessness. And don’t be afraid to layer textures; that’s what brings warmth and personality to a home. You do, after all, spend the most time in your home. Ultimately, your space should reflect you.

Your work empowers so many creative entrepreneurs. What is the single most important piece of advice you would give to someone looking to follow in your footsteps?

Know your voice and trust it. In creative industries, it’s easy to get distracted by trends or comparisons. But longevity comes from authenticity. Stay rooted in what makes your perspective unique, and be consistent with it. Also, don’t underestimate the business side; creativity needs structure to thrive. Surround yourself with people who can complement your strengths, and keep evolving.

Interview

Chukuka Okonjo

BDM, Fine & Country West Africa Founder, Compound

Meet Chukuka Okonjo, a dynamic disruptor at the nexus of real estate, storytelling, and culture in Africa. As the business development executive at Fine & Country West Africa and founder of Compound, he’s expertly reshaping how people discover and invest in African real estate. With a clear vision for the industry’s evolution, Chukuka consistently strives to learn and build better, making real estate feel more human and accessible through innovative digital platforms.

Let’s start with this: What made you take real estate online in such a fresh, fun, and engaging way, particularly on TikTok? Was there a “lightbulb” moment when you realised Nigerians needed a new language around property?

Let’s face it, Nigeria, and honestly, most of Africa, is terribly branded. The way we talk about property, investment, and even lifestyle is painfully outdated, inaccessible, or often, simply false. I’m on a mission to save the industry. TikTok is the fastest platform for growth and idea distribution. It gave me a low-touch way to test ideas, show personality, and start building a real connection and audience. But if I’m honest, my sister Chidi pushed me to start; she’s a marketing genius. She told me last year, “It’s 2025, you can’t make money and hide your genius at the same time.”

But let me be clear: TikTok is just the entry point. We’re going much bigger than that, much bigger. This is about reshaping how people discover, understand, and invest in African real estate at scale.

You show a lot of beautiful homes, but beyond aesthetics, what makes a home truly valuable in today’s market?

A home’s true value comes down to location, price, marketability, and exclusivity. Location is everything. A 20-square-metre box in Ikoyi is more expensive than the same box in Ikate because proximity to high-end environments drives value. It’s not just real estate; that’s how the world works.

A lot of people are still intimidated by the real estate world. What do you think are the biggest myths or fears about land and property ownership in Nigeria, and how would you like to debunk them?

A big myth is that all brokers and agents are clueless or scammers. A lot of them are, but that’s exactly why my company exists: to be the exception.

What cities or secondary markets in Nigeria do you believe are currently under-discussed but hold immense real estate potential, and why?

I don’t think in cities; I think in taste and spaces. I’ve mostly worked on Lagos Island, so I’m excited to explore the Mainland. It has massive untapped potential, with oldmoney homes and developments that just need a slight revamp. They’re significantly undervalued because of the current minimalist modern craze.

What are three pieces of content (videos, books, podcasts) that changed the way you think about real estate or building wealth through property?

1. Bernard Arnault, Chairman and CEO of LVMH, The Brave Ones, YouTube video by CNBC

2. ‘Does Lagos Have An Architectural Identity Crisis?’ article by Tim Ojo-Ibukun in The Republic.

3. Unreasonable Hospitality, a book by Will Guidara.

What’s your vision for property content in Nigeria? Do you think the way we talk about home ownership and land will look completely different five years from now?

I think the real estate market is severely unstructured. However, a lot of the people damaging the industry won’t last. The future of content is built on data, storytelling, personality, and truth. The dream of owning a home is a myth to most people; it’s a luxury most can’t afford. Therefore, content will continue to become more focused on lifestyle and environment, as the majority of people already rent.

Finally, a quick-fire round, just to keep things fun.

Most overrated real estate term? Opulent.

Lagos Island or Mainland? Island. I know it much better.

Land or house?

I’m an aesthetics guy, so homes.

Favourite neighbourhood to shoot content in? Ikoyi.

One property you WISH you bought three years ago?

I wasn’t looking in the market then, so I’m not sure.

Interview

Clement Tolulope

Architect

Founder, Penak Limited

Co-founder, PMPS consultancy

IG: @tolu.fell

C‘‘

lement Tolulope, founder and MD of Penak Limited and co-owner of PMPS, is a visionary in the design, architecture, and build consultancy space, specialising in translating client dreams into tangible realities while upholding strict structural and budgetary integrity. His profound passion for creating spaces that breathe, driven by the philosophy that beauty must meet function, began at age eight and solidified into a lifelong pursuit. Recognising the costly pitfalls of reactive consultation, Clement proactively empowers clients with crucial educational guidance, challenging the status quo to prevent poor outcomes and foster a legacy of smarter construction in Nigeria. With a diverse background encompassing architecture, electrical engineering, and an MBA, he navigates operational complexities as both a designer and an astute businessman. Clement’s unwavering commitment to challenging egoand fear-driven designs ensures clients build scalable ventures, not just structures, delivering a powerful blend of aesthetics and practicality.

For every five good projects, you see fifteen to twenty bad ones.

Over the years, what shifts have you observed in how Nigerians relate to architecture and space, especially with the rise of social media, Pinterest culture, and “fast-fashion” aesthetics?

I would say we are designing louder. There are many loud designs out there. I have seen some better designs recently, but for every five good projects, you see fifteen to twenty bad ones. And the budget for the bad projects may be higher than that of the good ones. The main shift I have seen over the years is the emergence of interior design as a popular skilled service, especially for commercial spaces, short-let apartments, and so on. But as I said, it is louder, not better. Because if it were truly getting better, our educational system would have formally integrated interior design into the curriculum over the last five years. You should be able to study it for five years here, not have to go to the Florence Institute of Interior Design or another

specialised school abroad.

We cannot just copy an interior design from the U.S., Turkey, or a restaurant in Dubai and replicate it here. We have a different climate, different weather, and different people. You have to understand what your environment needs. It is crazy because if you are going to shift, you have to do it correctly. The shift I have observed, driven by the emergence of interior design, often feels more abstract than grounded.

Every creative studio has growing pains. Was there ever a project that tested your values or pushed your practice to evolve? How did you move through that phase?

Workforce reliability is a primary operational challenge for us, impacting both internal staff and external artisans. To mitigate risks like fund theft, we’ve replaced direct artisan hires with vetted, accountable subcontractors. Internally, a difficult hiring market creates a frequent gap between employees’ stated skills and actual performance, leading to significant project delays. Consequently, we must continuously adapt our talent management processes to maintain efficiency in a fast-paced, competitive market.

These challenges and shortcomings affect us, but we have been able to navigate them and find a better system. The issue of theft has also

been a factor. When running an organisation like this, there is money flowing for procurement and logistics. We once had a new staff member steal a significant portion of project funds. We have learned from that and have put systems in place to prevent it from ever happening again in our next hundred years of existence, because we plan to exist long after we are gone.

Our commitment to Design Audits was solidified after a pivotal experience taking over a project that was already 60% complete. Upon conducting a thorough audit of the structure, mechanical and electrical plans, building flow, and zoning, we discovered significant loopholes that necessitated extensive remodelling. This project taught us the critical importance of insisting on comprehensive design audits from the outset to ensure a project’s structural integrity and overall success.

Finally, logistics is another significant problem. We are based in Lagos but handle projects all over Nigeria, from Enugu to Port Harcourt. Logistics is a significant challenge for our nationwide projects. While based in Lagos, we operate in over fourteen states, relying on thirdparty trucking for deliveries outside the South-West. This dependency creates substantial risks, as we recently experienced when a partner’s truck carrying 40 million in goods was seized due to the driver’s actions. Such incidents directly impact our delivery timelines and client trust, making it a critical problem we are still working to solve.

For emerging designers trying to find their voice or clients who want to collaborate more thoughtfully, what is the one piece of advice you think people overlook but is crucial to building

meaningful spaces?

My advice is to hire professionals early, right from the beginning of the project. I am glad that more people are now reaching out from the conceptual stage. For the last two years, people have been telling us what they want: a 50-room hotel, a laboratory, etc., from the very conception of the idea. They should consult professionals early, ask questions, pay for consultation, listen more, and plan for long-term use, not just for Instagram photos. They should think ahead: if there is a plumbing issue, where do we trace it? If there is an electrical fault, how do we find the source? So many buildings lack this foresight. They cannot track the source of a problem. Professional consultation is crucial from start to finish. The consultant doesn’t need to execute the project, but they must be involved in managing everyone on site. That is how you get results.

Looking ahead, what are your hopes for the industry in the future? And more broadly, how do you see your work affecting the entire architectural landscape of Nigeria?

I want people to see architecture in Nigeria as a reflection of real innovation, not imported inspiration. I want the government to invest in vocational schools. This will bring out talent in people and help us designers achieve a lot because when I design a concept and give the model to a skilled person for execution, it helps us scale. People who did not study in Nigeria often cannot design well here, so it is left to us. For the industry, I want architecture to help manage life, how we wait in hospitals, learn in schools, and build our communities.

Interview Osa Seven Multidisciplinary Artist

What does “home” mean to you, not just physically, but emotionally and artistically? And how has this definition evolved over the course of your career as your work moved from galleries to streets and large-scale installations?

“Home” is layered. It’s where I belong, where I remember, and where I create from. Emotionally, home is where I feel rooted, where my identity isn’t questioned. Artistically, it’s the context: the textures of Lagos, the sounds of traffic, the stories of Benin, all of that shapes the way I create. When I started, home was a concept I was trying to define for myself. I spent a lot of time in gallery spaces where art sometimes felt distant from the people it was made for. My art wasn’t accepted in galleries at the time because they didn’t understand it. But the streets taught me that art belongs to the people. That realisation shifted everything. Home, now, is wherever I can tell stories that live with the community, not just in front of them.

Your work often transforms neglected or overlooked urban spaces into something living, breathing, and meaningful. What do you consider when choosing a space to intervene with your art?

Meet Osa Seven, a multidisciplinary artist known for his work in urban art, including graffiti, murals, and large-scale public installations. His art masterfully fuses contemporary African identity with community consciousness, serving as a bridge between personal expression and collective memory. Working across diverse platforms such as walls, canvas, clothing, and digital media, Osa Seven’s ultimate goal is to shift perception and reflect people back to themselves with pride, colour, and meaning, encouraging them to feel, remember, and reimagine their world.

I pay attention to the energy of the space. What’s the story that space is already telling? Who walks past it every day? What memories or emotions might already be tied to it? I like spaces that have been forgotten because they hold the most potential to surprise and remind people that beauty can grow in overlooked places. I also think about accessibility: can people engage with the work up close? Will children see it on their way to school? Will someone who has never been in a gallery experience something that shifts how they see themselves? For me, art is dialogue, so the space has to invite that.

Nigeria’s urban design often leaves little room for public artistic expression. If

‘‘ We need ecosystems, not just workshops. Young artists need mentorship, access to tools, safe spaces to create, and platforms to be seen and commissioned.

you had a say in the national or state urban development plan, what would you change about how Nigerian cities are built to make space for art and artists?

First, I’d make intentional space for public art not as an afterthought, but as a design principle. Every city should have walls meant for expression, playgrounds infused with storytelling, and transit spaces that reflect the spirit of the people who use them. Second, I’d advocate for community-inclusive planning. Let local artists be involved in designing markets, parks, and bus terminals. We know how to reflect our people, their dreams, and their frustrations. Why not let that shape the city’s character? Finally, I’d push for funding structures that see art as infrastructure. Just like roads and bridges, art helps people move emotionally, psychologically, and even socially.

In a country where formal arts education and creative funding are still underdeveloped, how can we better support the next generation of street artists and muralists who want to make a living shaping the city?

We need ecosystems, not just workshops. Young artists need mentorship, access to tools, safe spaces to create, and platforms to be seen and commissioned. There should be residency programmes, art incubators, and local artist collectives that help creators move from raw talent to sustainable practice. And most importantly, we need to change the narrative to show that being an artist goes beyond passion; it’s a profession. That means funding, policy support, and cultural respect. I also think older artists like myself have a responsibility to reach back; to share our wins, but also our scars, the times we failed, pivoted, and started over. That transparency builds bridges. I’m trying to do all of this with my company, Inscribe.

What advice would you give young Nigerian artists trying to root their creativity in local culture while striving for global relevance?

Don’t dilute your identity. Your “local” is your superpower. The world doesn’t need another version of someone else; it needs your unique point of view as a Nigerian, as an African, as a creative person who understands both chaos and structure. But while you stay rooted, stay open. Study the craft and learn how global systems work: distribution, storytelling, branding, partnerships. It’s not selling out to understand structure. That knowledge gives you the power to share your culture on your terms. I’m a lifelong learner.

Finally, if you were to design a city-wide mural campaign titled “Nigeria Is Home,” what stories or symbols would you feature? And where would you paint the first wall?

“Nigeria Is Home” would be a love letter to the beauty of our culture and also its complexity. I’d feature symbols like the talking drum, the danfo bus, a Jollof rice pot on a Sunday, and fabric patterns and motifs, but also the faces of ordinary people, the woman selling boli, the boy carrying water, the elder who greets you with “my pikin.” I

would also include phrases and words that are distinctively Nigerian. While it’s tempting to include elements specific to every ethnic group, I think I would focus on the things that unite us. The first wall? If it’s in the City of Lagos, then Oshodi. Because it’s chaotic, alive, and unfiltered, just like Nigeria. Also, for many people coming to Lagos from other parts of Nigeria, their bus journey often ends at Jibowu or Oshodi. Besides, if we can put beauty on a wall in Oshodi and have it live, breathe, and inspire people there, it can live anywhere.

Interview

Richard Vedelago

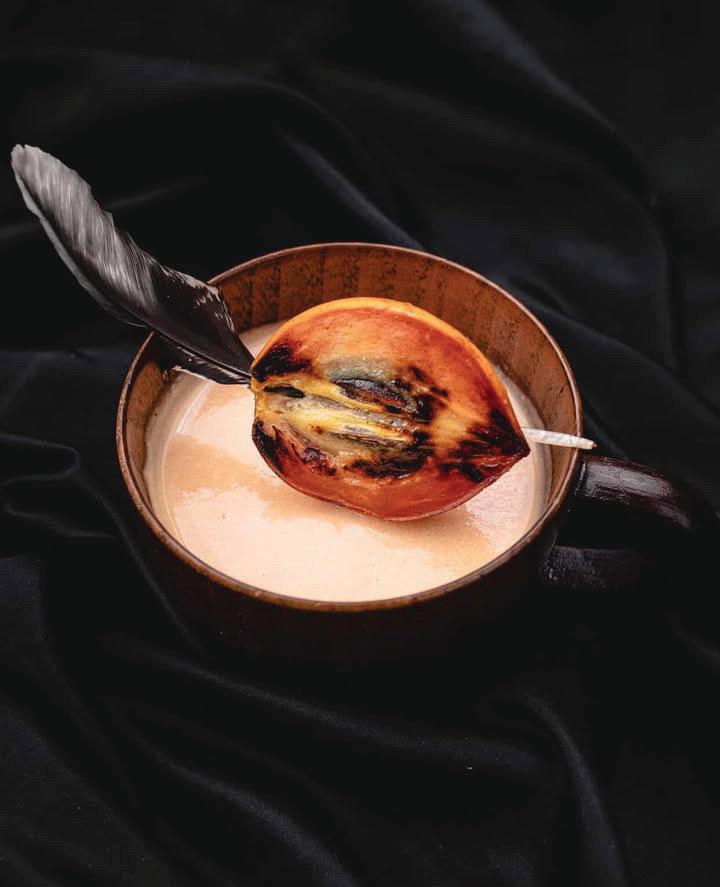

Founder, Windsor Gallery & Nahous

Meet Richard Vedelago, a cultural architect whose work is a testament to a singular, powerful idea: Africa’s creativity is not emerging, it is leading. A Nigerian-Italian polymath, he moves seamlessly between art, design, architecture, and gastronomy to build institutions that are both rigorous and romantic. He is the founder of Windsor Gallery, a leading voice in contemporary African art, and the visionary behind Nahous, the bold cultural hub resurrected from Lagos’s iconic Old Federal Palace. From award-winning restaurants to landmark publications, every project he undertakes is designed to craft a new narrative for the continent, creating enduring symbols of African excellence for a global audience.

‘‘ My goal is always to create space for reflection for people to think freely and connect with the work in their own way.

You speak passionately about bridging the insularity of African cities through art galleries. What does a truly connected panAfrican creative ecosystem look like to you, and what must we dismantle or build to achieve it?

It is a space where ideas circulate freely, where collaboration replaces competition, and where creativity is understood as a form of public infrastructure, just as essential as roads, education, or healthcare.

But for this to be possible, we need more than ambition; we need presence. We need a deeper, more intentional spread of galleries, cultural institutions, creative hubs, and public art initiatives across the continent. We need spaces that don’t just cater to the initiated few but actively invite new audiences into spaces that reimagine what a gallery or art experience can be. Spaces that blend art with food, music, technology, and everyday life, so that creativity becomes something

people live with, not something they visit occasionally.

Lagos should not feel worlds apart from Abidjan, or Nairobi from Dakar. We must reject the outdated idea that access to art is for the elite. Creativity belongs to everyone, and our institutions must reflect that.

Places like Windsor Gallery and Nahous are built with this ethos in mind: to serve as bridges, not walls. To create entry points for people of all backgrounds and interests, whether they come to see an exhibition, attend a music session, take a workshop, or simply experience a space where art and life meet. These are the kinds of ecosystems we need across the continent: inclusive, multi-layered, and rooted in dialogue.

Ultimately, we must believe in the power of our shared imagination. We must fund it, protect it, and expand it with the same urgency and seriousness we apply to other forms of nation-building. Because culture is not a by-product of development, it is the foundation of identity, unity, and possibility.

Nahous is not just a space; it’s a multi-sensory, multidisciplinary expression of African excellence. What does this space represent to you on a philosophical level? What void is it filling, and what kind of audience or community are you hoping to build through it?

Nahous isn’t just a space; it’s a response to a deeper need I see in the cultural landscape today. Right now, we’re at a turning point. So many creative spaces look good on the surface but lack originality and emotional depth. They feel like copies of each other, disconnected from our reality and from the people they are meant to serve.

Nahous was created to challenge that. It’s about building a space that feels alive where art, design, music, food, and fashion all come together to create something that moves you. For me, it’s about rethinking how we experience culture. It’s about creating an atmosphere that resonates, that lingers, that sparks something in you, whether you’re an artist, a collector, or someone who has never stepped into a gallery before.

On a deeper level, Nahous fills a void. It offers a new kind of space that reflects our complexity, creativity, and ambition as Africans. It’s not trying to copy what’s done elsewhere, it’s about defining our own standard. I want to build a community that’s curious, open, and willing to explore new ideas. A place that makes people feel seen, heard, and inspired.

Ultimately, Nahous is about creating space for connection for people, for ideas, for emotion. Because that’s what I believe we’re missing right now. And that’s what I think can truly move culture forward.

One of the most compelling parts of your vision is building infrastructure to keep artists on the continent. What are the three most important pillars that must be put in place to enable African artists to thrive locally while being globally relevant?

For artists to thrive here and still be globally relevant, we need to fix how they move, how they are supported, and how we as galleries work together.

First, we need to make it easier for artists to travel and exhibit their work across the continent. Right now, it’s harder and more expensive to get from Lagos to Abidjan than to London. We should have multi-city gallery networks that give artists multiple shows a year across Africa, not just one-off opportunities.

Second, governments need to understand that art is infrastructure. Moving artworks shouldn’t be treated like importing luxury goods. We need policies that support mobility and treat artists as cultural ambassadors.

And third, galleries need to collaborate more, share ideas, co-represent artists, and work together to push talent forward. We are stronger when we act like a network, not as competitors.

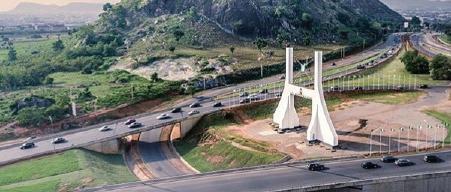

Cross-border gallery conversations are rare but increasingly necessary. What has been the biggest surprise for you, good or bad, about curating shows in Abidjan, Abuja, and Lagos? What have these cities taught you about creative differences and cultural connections?

What has surprised me most is how each city brings a different energy to art. In Abidjan, the work often feels more introspective and layered, there’s a deeper focus on concept and philosophy, which I think comes from the Francophone education system. Lagos, on the other hand, is bold and emotional; there’s an urgency to how people create and respond. Abuja is quieter and more measured, but there’s a growing curiosity and appetite for

engagement.

These differences have shaped how I curate. My goal is always to create space for reflection for people to think freely and connect with the work in their own way. I’m not trying to give answers. I want the viewer to feel that their response is valid, whatever it is. Art is subjective, and I see the exhibition as a conversation, not a lecture.

What is your perspective on the business of art, and how do you personally think about sustainability, especially when building something as ambitious and legacy-driven as Windsor Group?

For me, the business of art in Africa can’t just be about selling works; it has to be about building real economic infrastructure around creativity. If we want sustainability and legacy, we need to bring more financial institutions into the conversation. Banks, asset managers, and investors need to start seeing art not just as culture, but as capital, something that holds and grows value.

Right now, one of the biggest challenges is the lack of proper valuation systems across the continent. We don’t yet have widely accepted structures to quantify value, track provenance, or benchmark growth the way you would with other assets. Until we build those systems, supported by data, trust, and liquidity, African art will always be undervalued within its own market.

I believe the future lies in creating financial products that support the art economy: artbacked loans, collector funds, insurance products, and investment vehicles that help to diversify portfolios. But that can only happen when access to capital becomes a reality for artists, galleries, and collectors alike. The more we institutionalise the business side of art, the more confidence we build, both for local players and global investors.

That’s part of what I’m working toward with Windsor Group, not just curating shows, but building the financial and cultural architecture to support art as a serious, long-term asset class in Africa.

Tell us about your architectural and curatorial sensibilities, especially your love for brutalism. How do those influences show up in your projects, and what’s the most challenging part of reimagining old spaces into something living and modern?

I’ve always been drawn to brutalism for its honesty and strength. It doesn’t try to charm you, it confronts you. That rawness is something I also bring into my curatorial practice. I like to break codes, challenge expectations, and brutalist spaces give me the freedom to be bold. They allow me to place works in ways that feel direct, unfiltered, and sometimes even uncomfortable, and that’s where the most meaningful conversations happen.

Architecturally, I’m interested in reimagining existing spaces, especially ones with history and texture. With projects like Nahous at the Federal Palace, it’s about working with decay, not against it. These buildings weren’t made for today’s uses, so the challenge is always how

to make them functional without losing their character or having them collapse on you. It is a delicate balance between preserving the past and engineering a present that works.