The unnatural forest

Solo silver foxes and arctic wolves surge forward briefcases in hand, rippling the pack with suave waves of motion. Thick coats, white teeth. Wise not to get in their way. The young’uns are sharp as sharks, massing in a great grey pod pushing in sync towards the front, sleekly suited

rolling on their toes, bobbing and keen for action. Others are decorous in navy, white-bibbed

like minkes, curious, communal, not pushing themselves to the starting line. The rest of us

gather loosely in undifferentiated shoals behind the pack, patient, moving aside en masse to let the insistent ones through. A wild boar snuffles up to me, hungry eyes, yellowed tusks.

I want to close my coat, step back. He smiles but nothing reaches his eyes. I don’t want to get

close enough to smell his sweat or what he has wallowed in or the rank odour of his breath.

With apologies to the animals for using them in describing (mostly) undesirable human traits experienced in airport queues.

His thumbs prickle

Brother Cadfael

Chief Herbalist, Benedictine Abbey, Shrewsbury UK

Plenty of gruesome work for a herbal alchemist cum sleuth in the crusade-ridden, barbarous 12th century. Brother Cadfael has discovered his vocation in charge of the physic garden and distillery of a thriving medieval Monastery. In good odour with his Abbott, he has free rein outside Abbey walls to winkle out crime, his holy duty to expose evil. Used to working with his hands, when criminals prowl it’s his thumbs which prickle. He kneels on his ‘chair’, a prie-dieu in his apothecary, surrounded by aromatics of drying herbs – yarrow, comfrey, plantain – and the beakers and flasks of his trade, making unguents and simples for townsfolk and monks alike. He doesn’t need to be in Church to pray, nor does he need to be out of it to think through clues which collar culprits. All is God’s good work. Perhaps, he says having wished ardently and the thing accomplished, thought really is prayer.

Based on the character created by Ellis Peters in The Second Chronicle of Brother Cadfael, One Corpse Too Many, published 1979.

Photograph courtesy https://mysterytribune.com/

© Anne M Carson

©Mark Ulyseas

Derek Coyle

Derek Coyle’s Reading John Ashbery in Costa Coffee Carlow (2019) was shortlisted for the Shine Strong 2020 award for best first collection. Sipping Martinis under Mount Leinster (2024) is published in a dual language edition in Tranas, Sweden. His poems have appeared in The Irish Times, Irish Pages, The Stinging Fly, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Texas Literary Review, The Honest Ulsterman, Orbis, Skylight 47, Assaracus, The High Window and The Stony Thursday Book. He reviews books regularly, and he has written literary essays on the poetry of Seamus Heaney, John Montague, James Schuyler and Paula Meehan. He lectures in Carlow College/St Patrick’s, Ireland.

Carlow Poem #39

I remember listening to Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme. My dad’s record player, the seventies or eighties living room, depending where your eye landed. Art Garfunkel, ethereal in the speakers, a faint crackle. ‘For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her,’ the rise and swell of his voice. ‘Crinoline …and lamplight.’ I saw fields of ripened wheat damp in the rain. I must play you this song. Even though it will probably make no sense to you. How to convey the meaning of a sentence we’ve run through our fingers, weighing up the words like a village grocer measuring out sugar? Sifting through others, like braille, or a rosary. How we hold a line close to the heart. What I didn’t see in those dreams, what I didn’t hear between the lines of Paul Simon’s song, was you striding through the hall of my house, your cap on your head, the green one with the brownand-red lined squares – the one you bought in T.K. Maxx in Kilkenny, and wore to Cork all that weekend, our first trip away. It’s like the way Paul Simon wrote the song, but Art Garfunkel filled it full of feeling. Sometimes, the way you move your hands to your glasses, to re-arrange them, to get them back in place, although they’ve hardly moved, is enough.

Carlow Poem #121

The way the head rises up and out of the stone, almost like fizz surging to the top of a soda. Is it joy in Mahler’s face, or satisfaction —how Rodin felt after he laid down his chisel? He had found some kind of answer – man accounts for nothing, stone everything. Still, the flex of muscle, the feel of flesh laid bare in marble. The receding hairline. The bumps in the brow. This stone has captured it all. Something is stored here. Rodin spoke no German. Mahler spoke no French. Something is exchanged beyond words. Rodin decides to call it ‘Mozart’. Despite the fact, he later claimed, Mahler had a head like Benjamin Franklin, or was it Frederick the Great?

Carlow Poem #89

It is like biting into a raw slice of that dun rhizome, ginger. Pungent, insistent and exotic, these thoughts I have sitting outside the Irish bar on Guantanamo Bay. I’m thinking about Gustav Mahler as a kid. He follows the local brass band home, the pulse of their march, the vibrato of the brass, dances inside his ear. In Cambridge, England, in discrete corners of the universities’ gardens, you can dig up a fungus the locals call the jelly ear. I eat one in my mind’s eye. Poetry sprouts abundant, its tangled mycelium settles itself into my nooks and crannies. Like music. The way Mahler heard cowbells at the centre of his symphony, or the twitter of a bird flittering over the woodwinds. I see him in his music hut, lying down on the floor, like a frog doing yoga, meditating, motionless, as the wind gently moves the world outside his door.

Dominique Hecq

Dominique Hecq is a widely anthologised and award-winning poet, fiction writer, essayist and translator. She lives and works on Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung land (Naarm/Melbourne). Hecq writes in English and French. Her creative works comprise a novel, six collections of short stories and seventeen books of poetry. Together with Volte Face and Otopos her bilingual sequence, Pistes de rêve, appeared in 2024.

Passing through

Wherever you come from or are— hybrid or not uprooted or not you only ever write to prove that you exist. In doing so, you lose yourself empty yourself dispossess yourself destroy yourself re-craft yourself.

Only nothingness signifies everything. It is from loss that you draw your strength.

You pulled at your moorings moved on transgressed.

All the while knowing that one never leaves.

Yours is a borderline, insular, precarious, ambiguous predicament: you keep on displacing the horizon.

On the edge of alien shores

The giant neon swan flashes white against the black sky.

Beneath, the naked city lies on its back like Leda knees apart in porno freeze-frame.

The freeway busts right up through.

The territory slides off the map towards Bass Strait but you’re grounded.

Decay oozes from the river. Gets into your skin. You choke on its humid breath.

It’s so hot and humid this could be Singapore or Saigon but it’s the city you now call home.

The further west you go the fewer lights And all seems on the verge of subsidence.

Stripped out factories crumble under their weight as mud percolates its way up through the sediment.

When the river breaks its banks the scum of petroleum rises up the waterways, drowning the eels—iuk iuk iuk iuk iuk.

Cri et silence

You are made of particles separated in time and space, so only truly become yourself in your relationships with others. With leaps into gorges within these very relationships. At the font of all life, which is essentially the other. And which allows you to be yourself and more present to others.

You who also have a dual allegiance as human: to life and death; to time and eternity; to murder and life; to time and eternity, to the unconscious and consciousness. A dual allegiance compounded by your sex: you can give life, but also take it away.

In this world in which we live and which, in its very convulsions, is already that of tomorrow, what is required of us in the first place? If not to work towards the advent of this relationship between oneself and the other. To write. Which is why I can’t dissociate writing from crying out.

Doreen Duffy

Doreen Duffy was awarded her Masters with 1st Class Honours in Creative Writing, at Dublin City University, she also studied at National University Ireland Maynooth, University College Dublin and Oxford Online. Doreen is a Pushcart Nominated Writer. Publications include Chicago Writers Association, Write City Ezine, Poetry Ireland Review 129 by Eavan Boland, Live Encounters (Free Online Magazine From Village Earth), Washing Windows 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 by Arlen House, Beyond Words Literary Magazine, (Germany), The Storms Journals 1 & 3 & 4, The Galway Review, Flash Fiction (USA) and in, Glisk & Glimmer by Sídhe Press, The Incubator Journal, The Woman’s Way and The Irish Times amongst many others. She won The Jonathan Swift Award and was presented with The Deirdre Purcell Cup at The Maria Edgeworth Literary Festival. Doreen was shortlisted in The Francis MacManus Writing Competition. Her story ‘Tattoo’ was broadcast on RTE Radio One. https://doreenduffy.blogspot.com/

Every grain of sand

The sea came begging in waves, over and over again. Standing at the edge my thoughts racing. Jostling stones struggling between brown leathery straps of weed, tied themselves up in knots. Over the sound of the washing waves, I breathed in. Heard my breath shake as I exhaled.

How could life alter so suddenly after a simple check-up. Maybe it was me, maybe I’d flaunted my happiness. I always got scared when I allowed myself to get too happy. The miscarriages had taught me that.

Earlier in the warm glow between sleep and fully awake I’d reached out to Joe, without opening my eyes, found his mouth and kissed him deeply, moving against him bringing him into me. It was pure bliss to make love just for the sake of making love. Afterwards he looked at me, smiling all the way up to his eyes. He looked at me differently these days. Warm relaxed smiles replaced guarded looks. Some of the creases around his eyes seemed to have smoothed out. When I felt him drift back to sleep, I eased myself out from under his arm and hauled myself out of bed.

In the kitchen I’d flicked the switch on the kettle, opened the curtains letting sunlight spill into the room giving everything a hazy yellow glow. My mind wandered into thoughts about how perfect our little family was going to be. I was so happy. Unable to resist I reached for the shopping bags from the day before. I took each item out slowly, one by one placed them on my knee, smoothing the tiny white Babygro’s, feeling their softness. I couldn’t wait to feel the little form wriggle inside them; the same way I felt our baby flutter inside me. When Joe came down to the kitchen, he saw me with the little clothes, he smiled and leaned down and kissed the top of my head.

‘You go have a shower, take your time getting ready to go to the hospital; I’ll make us a nice breakfast. I’ve got a few hours before I have to get to the airport.’

I knew he felt awful not being able to come to the check up with me, but his boss had insisted he was the man needed to secure the new contract in London and it had to be today. He promised he would be home tonight. I said I didn’t mind at all, but there was just a tiny niggle of superstition gnawing inside me. When we had attended the previous check-ups together, everything had been perfect.

I spent time choosing my clothes. I wanted to look nice, feel as pretty as I could, it was important to me because I knew I might feel older than some of the other ‘mums to be’ at the hospital. I thought of how long it had taken and winced at the memory of some of the more invasive tests before we finally became pregnant.

‘That’s what makes you even more special,’ Joe said regularly, stroking my stomach, using a soft voice I’d never heard him use before.

I chose a long skirt and a loose silky blouse over it that settled itself, covering my softly swelling stomach in its folds.

The other mums couldn’t have been friendlier. There was an air of happiness in that room that I was thrilled to be a part of. A buzz of excitement while we chatted, compared notes. Laughing, I showed them my attempt at knitting,

‘It’s a new hobby,’ I said, feeling the heat reach my face while I showed them. ‘I only started to knit when I found out I was pregnant. Mam said she would teach me.’

‘Imagine.’ I’d laughed, ‘only learning to knit at my age.’ It didn’t actually feel so bad to admit being older. Not anymore.

I loved the days me and mam spent together.

‘You’ll get the hang of it in no time,’ she’d said, piling on the encouragement. ‘Just persevere, don’t worry about making mistakes it’ll all come right in the end.’

The conversations we hadn’t ever shared before, topped up with cups of tea meant so much. I thought of the warmth of Mams hands over mine as she helped me with my knitting, I was taken aback noticing how much more wrinkled her hands had become. Hands that had dealt with so much, aware for the first time of their immense strength, reminded of all she had done for me.

I held up the shape of a tiny, knitted cardigan and showed the other mums the holes where distracted I’d dropped stitches.

‘But’ I told them, ‘I am determined to keep going even if my baby is the only one in the ward with holes all over their little cardigan. I’ll still show it off as one of my first masterpieces of knitting wrapping my little baby in its woolly warmth.’

I squeeze my eyes tightly shut against the salty breeze, trying to squash out the image of the nurse’s face as she had swept the transducer over my jelly covered stomach and watched the pictures on the screen.

She had started out happily pointing out which way baby was lying, showing fingers and toes. I was in my element. But then she went quiet, an eerie quiet grew around the room filling up all the space. She swished the transducer again. More slowly this time over my stomach. Everything seemed to slow down, the nurse’s movements, the whispering hum of the machines, everything except the beating of my heart, it started to race so much it hurt.

The nurse said she would be back in a minute, she just had to speak to someone. She left the room. When she came back, she had another nurse with her who smiled tightly, just for a second at me. Then they both sat and pored over the screen, this time the second nurse performed the scan. I was so cold I was shivering, trying to stay still, trying not to do anything to upset whatever it was they could see. Afraid to speak. I wanted to get up and run out, go back to how I felt in the waiting room maybe if I stayed perfectly still would the world stop spinning, stop whatever this was that was happening.

The second nurse stood up, held my now freezing cold hand in hers, mine cold and wet, hers warm and dry. She looked down with eyes full of concern. I felt that look reach in and rip something inside me, my breath caught for a second, my mind tried hard to clear the swirl of thoughts. The other nurse busied herself wiping the jelly off my stomach pulling a blanket up over me.

‘You see, it’s some of these measurements, some markers showing, fluid behind baby’s neck, they’re showing as a little more than is considered normal at twenty weeks.’ She touched the screen pointing her finger at the grainy image.

My stomach lurched at the word ‘normal.’

I felt cornered, at the mercy of these two people moving in front of me, a blue uniform dance of horror while they churned out words that broke off and splintered into me. I hated the fact that she could utter these words, that I could not stop her, that I could not put my hand over her mouth and smother the life out of every syllable. A surge of viciousness rose up inside me. What kind of sick twist of fate was this, turning life upside down in a second. Language I rarely used pierced my thoughts; burst all those stupid, stupid bubbles of dreams I’d had in my head.

We were careful, we didn’t tell anyone until we were twelve weeks. We did everything we were supposed to do. Read all the books. Ate the right food. No one told me that from the time I realised I was pregnant I wouldn’t be able to stop myself from thinking about this child’s life, school, leaving school, getting a job, maybe having their own family. I saw and imagined their whole life. I couldn’t stop myself.

‘These measurements.’ The nurse went on quietly, ‘would mean you would need to have further tests.’

Even while she said it, her eyes made their own confirmation.

‘Your doctor may recommend that you consider having an amniocentesis. I’ll make an appointment for you to discuss this as soon as possible.’

An appointment, was she mad. I had to leave here today with our three lives turned upside down and inside out. I had to tell Joe, how was I supposed to do that, and then we were to live each day and try to sleep each night until I went for another appointment for some sort of test, I couldn’t even remember what she called it. How, how were we supposed to do all of this.

Questions bubbled up in my throat. But there was no point in questions now. I knew the blame lay with me. I didn’t know how, but I just knew it. I shook my head, tried to sit up, they didn’t stop me, they helped me, fixed my clothes, brought me to the chair, a glass of water was poured, the second nurse held it to my lips told me to sip it.

I had left the Hospital clutching my things to me.

‘No, I don’t want you to contact anyone; I just want to go home and talk to Joe.’

I was surprised to hear my own voice sound normal, that I could still form a sentence and speak it. I half walked; half ran through the waiting room of happy expectant mothers. One of them jumped up smiling,

‘You forgot your knitting.’

She held it out to me but when she saw my face, a tiny gasp broke free, she bit her lip to stop it, rolled up my knitting and pressed it softly into the top of my handbag and turned quickly away.

I drove, somehow, I don’t know how, almost automatically. I didn’t stop until I reached the car park at Greystones. The place Joe and I loved. We went out there to the coast almost every weekend, in all weathers. I needed time to think, time to breathe. The thought of telling Joe, seeing his face tighten, as the words filtered through, the pulse in his jaw start with the effort of trying to be strong. He would do his best to try to stifle his own fears to support me. He would tell me everything would be okay; he would tell me we would be the best parents for this baby. But I didn’t know if we would.

The thought of him trying to cover his emotions made mine rush to the surface. My throat made a horrible choking sound. I thought I was going to be sick. I opened the car door, grabbed my handbag to get tissues and felt the soft wool brush my fingers. There’s this tiny life, there’s Joe, there’s me, there are all the people in this world who wake up one day and their lives have changed forever.

Everything has darkened, the sea has changed colour from blue to dark green, a completely different view in a split second. A cloud has passed across the sun. I shiver. The silky blouse isn’t warm enough to shield me now from the cold coming in from the sea, it seals itself to my skin in parts, trying to keep in the heat. I can feel my body beneath all these folds, still the same. The shape still there. I wish I was still in the waiting room, waiting for the scan, looking forward to getting another glimpse of our baby, a peep at the little life growing inside me. Waves are riding in, pushing against me, like a monster hiding a bellyful of horrors in its depths.

My feet and legs are totally immersed now. I can hardly see anything beneath the water. The coldness has settled into me; it is no longer unbearable. I move further in. How long would it take to cover me completely. Could I just stop all of this, the hospital, the scan, the nurse’s face, her pointing finger, could I take my baby and all those babies before that didn’t make it. Could I give in and let the gasping fear choke the life out of us in its salty liquid.

The cloud moves and a glare of heat sears my shoulders around my back, sweeping around my legs now deep in the water. I look down at them feel them rocking gently against the grainy mass, trying to envelop them, but they are still moving, it’s not just my legs, my hands go to my stomach and feel the little life inside me move and nudge against me, gently at first and then stronger.

There’s a stinging burning at the back of my eyes and tears start to fall. Hot like the blood I had lost so many times before. I cry, hard, for the baby I thought I was going to have, and I cry for the baby I now know I will have.

I keep my hands around my middle raising it above water and drag my legs, one at a time out of the deep suffocating sands I struggle through the shallows towards the beach. I walk back to my car, my skirt slapping wetly against my legs. I lower myself into the car, pull my knitting out of the bag. I smooth the little cardigan over my stomach feeling my fluttering baby inside. I sit for a long time, until it gets too dark to see the holes in the wool.

© Doreen Duffy

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Eugen Bacon

Eugen Bacon is an African Australian author. She’s a Solstice, British Fantasy, Locus and Foreword Indies Award winner, a twice World Fantasy and Shirley Jackson Award finalist, and a finalist in the Philip K. Dick and Ignyte Awards, and the Nommo Awards for speculative fiction by Africans. Eugen is an Otherwise Fellow, and was also announced in the honor list for ‘doing exciting work in gender and speculative fiction’. Danged Black Thing made the Otherwise Award Honor List a sharp collection of Afro-Surrealist work’. Visit her at eugenbacon.com

Is This How You Pictured It?

Random edicts dispensed with the need for artists and lovers because the universe needed streamlined solutions.

Robots replaced doctors and priests. New capsules, amputations, implants, placebos and brains in three dimensions for— the most outspoken to— encode statistically beautiful humans, constructed with replaceable parts.

We can’t remember how to feel. Shadowless seasons cartwheel along dream-a-day calendars.

No more vulnerable and needy people— just the elegance of chromatic mandolin music glittering in high pitch along pristine streets as instruments of war.

Nurses in starched uniforms play lacrosse in a manicured graveyard.

All things are a price

she met a myth and a chant— now time is a melody for the epilogue of a new night sky the antiquity of cosmic love an ultraviolet replay of mindless songs drifting memories, death spiralling hot to beat the sunrise.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Jean O’Brien

Jean O‘Brien is an award winning poet with six collections, the latest being Stars Burn Regardless published in 2022 by Salmon Publishing. She was poet in residence in the Centre Culturel Irelandais in Paris in 2021. She has won, been places and highly commended in many competitions. Coming first in the Arvon International competition (UK.), the Fish International and amongst others has been Highly commended in the Forward Single poem prize (UK.), placed and Highly commended in the Bridport Prize (UK). She was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh fellowship and various arts counclil awards. Her work has been broadcast and appeared in many anthologies and in Poems on the Dart (Ireland‘s Rapid Rail System). This spring she read and appeared on conversation panels in Carlow University, Pittsburgh (USA), where she tutors in Ireland on their MFA low residency programe. She collaborated with the Texan State Artist Dixie Friend Gay and with Irish Artist Ray Murphy. Her poetry has been set to music and voice by celebrated composer Elaine Agnew and at the inagural launch in Trinity College, Dublin from where she holds an M. Phil in cw/poetry. She currently tutors in Prisons, The Irish Writers Centre and Community Groups.

Grace

Even now, in this delicious noisy quiet, in this place where nature rules, flies buzz, bees drone, birds go about their day singing till sundown, sometimes I long for the background thrum of city noise, the ceaseless throb of traffic, raucous gulls tormenting the skies, alarms and ambulances competing for prominence. The breaking and shattering of air causing pandemonium, not to mention the regular ding of the Luas tram pulling out from the station, the ping of yet another notification from our phones, the clatter of supermarket trollies bashing together. Sometimes you need discord to remind you of grace.

Reading the National Geographic Magazine as a child.

The cover yellow, as a hazard warning, lured me to read the fat pile of magazines. Sent to Granny’s to do homework and bored with maths I didn’t understand I flicked the illuminated pages filled with strange lands, lush Amazon forests, not yet denuded back then;

saw people with sticks through their noses, Myanmar women with elongated ringed necks. They revealed the world as a wonderous place and offered more interest than my well-thumbed school books, that seemed designed to keep us inside the margins of a limited life.

We were shown pictures in history class of the Irish famine and impoverished lives on the Blasket Islands. The National Geographic said Africa was a dust bowl, our books showed Irish missionaries bringing religion to these far flung place. I flicked the shiny pages of the magazine almost blinded by flocks of neon green parrots, orange fire raining from volcanoes

and oceans so blue they were hard to believe.

I studied my atlas, followed the convoluted course of rivers feeding the Amazone basin, fingertip traced the river Nile travelling through Africa and Egypt until it emptied into the Mediterranean sea. Eventually granny called me for tea.

As I sat amongst egg sandwiches, doilies and delicate china I imagined they were yams and prickly fruits and felt I had travelled so far over hazardous terrain that my mind had stretched like those women’s necks and would never shrink so small again.

Furniture

Discarded like an ill-fitting coat, vignettes or maquettes of peoples lives on the street, remnants of a lived life, furniture put out there for strangers to claim and keep.

There is a chair, a side table, a well mottled mirror, missing only a bed to complete the tableau, it all reminds me of the old Pathé newsreels of war bombed streets where half a house still stands, almost vulgar, exposed to air and eye. The ripped floral wallpaper, the cold grate, all there to be viewed by any passer by, perhaps a door that leads to who knows where, rooms never seen by any stranger before, naked now. On another street I come upon a small table, some toys and two children’s seats

and wonder where those same children are now, no doubt somewhere walking in the world masquerading as adults as we do. Our secrets hidden behind four walls and a front door that you need permission to enter or retreat. Not old castoff lives like this sprawled out on pavements. Perhaps some passing child will entreat her parents to lift the chairs home and grant them succour.

Jim Burke

Jim Burke is co-founder with John Liddy, of The Stony Thursday Book. His haiku feature in ‘Between the Leaves: New Haiku Writing from Ireland’, Arlen House (2016). ‘Quartet’ with Mary Scheurer, Peter Wise and Carolyn Zukowski (2019) ‘Montage’ Literary Bohemian Press (2021) ‘Slipstreaming in the West of Ireland’ (with John Liddy), Revival Press (2024). Guest editor with John Liddy of the 2025, 50th Anniversary Edition of The Stony Thursday Book.

Soldier

One day he shelved his childhood and left a glass-jar life with minnows. UK bound, then soon to Iceland and Reykjavik with the RAF, where his voice acquired an English cadence. He accepted a service medal but carried in the breast pocket of his tunic, a half crown that his father gave him at the bus station.

‘If you ever need to make it back home,’ is what he said.

Era

Everything is but for the moment a rick of hay the joker sitting up front behind a slow old horse.

Nostrils tingle in the dust of the hot afternoon air. Sometimes these left-over echoes of humour and affection gather from our ghostly land to become anecdotes on a cart-path that evinces the clacking accent of time.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

John Liddy

John Liddy was born in Ireland. Between Boundaries (Nora McNamara/Limerick Leader (1974) and Slipstreaming in the West of Ireland, co-authored with Jim Burke, Revival Press, (2024) he has published fourteen poetry books, a collection of stories for children Cuentos Cortos en Ingles: Los Sonidos de los Vocales (Bruno, 2011), edited with Dominic Taylor 1916-2016 An Anthology of Reactions and Let Us Rise 1919-2019 An Anthology Commemorating The Limerick Soviet 1919. Liddy has also translated poems to and from English, Irish, Spanish and edited special editions of Vietnamese poets and Irish language poets for The Café Review and The Hong Kong Review, of which he is a Board Member. Two in One, a collection of short stories, co-authored with his brother Liam, was recently published. He is currently working on a collection of poems True to Form.

The Dead Man

(Dinggedicht)

He lies out there, beyond Clogher Strand, without protection, a stake in his chest, like a man playing dead on sand surrounded by poking children.

Lashed by storms and baked by sunshine he is all glum; the sea crashing against his sides, the gulls taking advantage when the whim is on them.

On summer and autumn evenings I see him all askew, waiting for a sign from the Northern star to solve his dilemma, which I vow to do.

During winter nights we both struggle to find peace, the constant wind and sleet echoing the turmoil around us, while I imagine he hears the pleas

I send him from the seashore, for a world forlorn because of rampant destruction by people who care nothing for the home we so dearly depend on.

Perhaps I hear him too, urging me to visit, to sit beside him and listen to his take on life, the wisdom of his years, his most precious request denied

Which I rectify, under a bright spring shower –I go out and pull the stake from his chest and the whole Island shakes. From where do we get the power?

The Dead Man is a rock island off the coast of Kerry in Ireland known in Irish as An Fear Marbh, because of its shape. Clogher Strand, Trá Chloghair, from where the dead man can be observed.

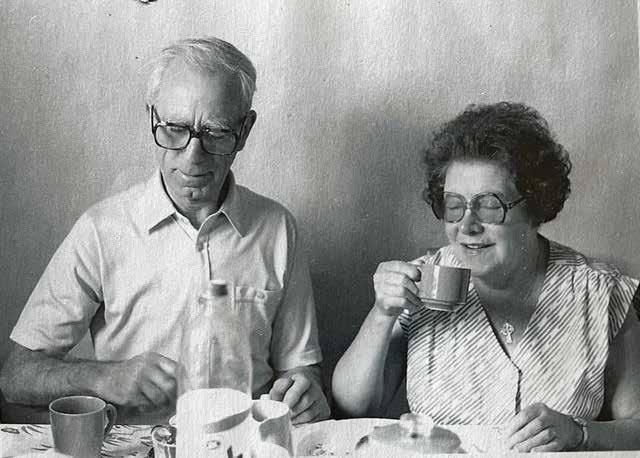

Fifty Years A-Growing

Ode for Jim and Jean

1.

How long is a piece of string, one might proffer by way of reply to the longevity of a lasting union only you can justify.

Reason enough to contemplate the palpability of communion, whatever luck may dictate, your children’s children

The echo of that first ‘yes’ resounding fifty years later, now speaks warmly of largesse and what you share together.

2.

There were no smoke signals from that pipe given as a gift –Magritte would posit claims that it never did exist

Along with those balls of wool and knitting needles, gan dabht strange offerings but brimful back then like a strand far out –

Emblems for a life woven from a treasured trove, mind and body in unison sustained by enduring love.

gan dabht: without doubt

Snookered

(Open)

One by one the red satellites drop out of existence

And each colourful planet is returned to its spot.

Then they too begin to disappear as the young

Deity angles for position, weighing up the safe shot

Or all-out attack, caution abandoned, risk its reward

While the older deity patiently waits in ambush

To send the last red behind the black sun with the white

Moon at the end of the world, beyond the reach of its predator.

John W Sexton

John W. Sexton lives on Carn Mór, a mountain on the Kerry side of the Beara peninsula. He identifies with the Aisling poetic tradition and his work spans vision poetry, contemporary fabulism and tangential surrealism. His poetry is widely published and he has been a regular contributor to Live Encounters. He is the author of eight poetry collections, the most recent being Futures Pass (Salmon Poetry 2018), Visions at Templeglantine (Revival Press 2020) and The Nothingness Kit (Beir Bua 2022). In 2007 he was awarded a Patrick and Katherine Kavanagh Fellowship in Poetry.

A Chime of Hearts

A slow darkness obscured her heart after the slam of the door. A solstice froze all light. Her heart took refuge inside her mind, a wren snuggling into its own feathery knot of comfort. A coincidence of déjà vu, her heart encountered all her hearts of past hurts; those hearts a confluence of betrayals, memories congealed as a stunning now. All of her hearts converging in warm anxious uniona nesting of wrens in a winter box.

The Early Warhols 1949 – 1959

In the cloud-spotted sky, light from the moon was never flat, but fell in funnels down all the Pittsburgh nights of his youth. Under a cone of moonlight he beheld his first transformation of colour, where cars and buildings were bright in their mutedness. And the moon itself was constant in its changing faces. This lesson, much later, he’d apply to his silk-screen series of the famous: Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, Elizabeth Taylor, Debbie Harry, Ethel Scull, Man Ray, Basquiat, Mao Zedong, character upon character, like the palimpsests of the moon’s phases. Moonlight, a mere reflection of something true, would become a filter towards a new way of seeing. Though long before that he would be making his first experiments with repetition, but in the vivid colours of daylight.

Straight from his degree in illustration he was selling textile designs of repeating patterns to Stehi Silks, Fuller Fabrics Incorporated, M. Lowenstein, Cohama, Balmoral Loom, and his resultant dress fabrics containing multiples of pretzels, ice cream sundaes, toffee apples, nautical flags, bugs, clocks, luggage tags and suitcases, bezum brooms and brushes, cut lemons, buttons, and jumping acrobatic clowns, were rippling without stop, upon the dresses upon the bodies of young women in every American city and town, all wearing the anonymous art of a for now unknown, unremarkable, undiscovered Warhol.

Chiyo-ni and the Oracle of Cups

Fukuda Chiyo-ni, Japanese poet and latterly Buddhist nun, 1703 -1775

The first bowl of jasmine tea pours clear from the pot, a selfless window into nothing.

In the steam from the bowl she sees her dead husband; he is unfolding a paper lotus.

The lotus expands into a door. Her husband enters the door and bravely closes himself into it.

The second bowl pours golden. In the oil floating on the tea she sees a Death Spirit.

The Death Spirit is stretching her husband between its hands, kneading him into pale dough.

The Death Spirit drops the malleable lump of her husband into a bamboo steamer basket.

The third bowl pours dark. On the dusky surface of the tea she sees a moon of dumpling.

Inside the dumpling her husband is humming like a child. The dumpling splits open.

From the dumpling a choir of hornets rises upwards, a drone of the word “beginning”.

Lisa C Taylor

Lisa C. Taylor is the author of the 2025 novel, The Shape of What Remains, three poetry collections and two short story collections, most recently Impossibly Small Spaces (2018). Her honors include the Hugo House New Works Fiction Award, Pushcart nominations in fiction and poetry and Best-of-the Net nominations in both categories. Her poetry collaboration with Irish writer Geraldine Mills, The Other Side of Longing received the Elizabeth Shanley Gerson Honor at University of Connecticut. Lisa holds an MFA in Creative Writing, and she is the co-director of the Mesa Verde Writers Conference and Literary Festival. Lisa has received writing residencies from Vermont Studio Center, Willowtail Springs, and Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Ireland. Lisa was a spotlight feature on the AWP website and a two-time mentor for the AWP writer-to-writer program. Lisa edited the anthology Four Corners Voices in 2025, and it recently received the Colorado Book Award.

Primary and Secondary

He could irritate me just by unzipping his parka. He wasn’t content to take it off, he liked to zip and unzip it repeatedly, so it sounded like a swarm of bees congregating in the mudroom. That was another thing—the mudroom. It’s called a mudroom so I can put all my soiled clothes and shoes down there. It wasn’t uncommon to find Calvin’s paintsplattered coveralls hanging from the wooden pegs or several pairs of dirty sneakers and boots scattered on the floor.

We met at a party that my college roommate dragged me to, saying I didn’t go out enough. You’re never going to find anyone by staying in the apartment every weekend. I didn’t want to tell her that I wasn’t looking because it sounded as if I’d given up. The truth was a slightly different. I didn’t like sex and I didn’t like men. Calvin showed up on a bet. He’d spent every weekend in the lab and his housemates offered him $20 each if he went to a party and left with a woman.

We’ve had this deal for ten years now. I pretend we’re partners, and he tells his parents we decided not to get married because I come from a family of divorce and I’ve been traumatized. Truth is we’ll never be lovers because we’re gay. Yeah, I know that gay marriage is legal and this should be a non-issue in 2024 but he’s from the South and I’m a private person. It makes me squirm to think of my parents imagining my sex partners—men or women---makes no difference. They already call every other day and dropped in without asking when I lived locally. Getting the librarian job in Oregon solved that problem. It took them two years to get used to the fact that Oregon is three hours earlier than Maine. Calvin’s family lives in Florida so our ruse is successful. He brings me to weddings and an occasional family reunion but locally he doesn’t pretend even though we share a three-bedroom house.

“This is my friend, Bertie,” he tells a muscular man with a stud in his nose and spiked hair.

I don’t bring him most places because there are only a few places I want to go with Calvin. We both like flea markets and Indian food so we do that together. Some people are loners, my mother said last time I was home. She looked at me with the kind of look that translates to you need help but I just stared right back. I’ve perfected the art of staring.

“Roberta Marie, you need to drop a few pounds. You’d feel so much better about yourself.”

My mother is built like a jockey—a small-boned miniature person. No horse would want me on his back. Some of us make bigger footprints in the world. My last lover called it zoftig but my mother just calls me fat. Needless to say, I don’t go home often. I’m not obese or anything, just on the rounder side of average but in my family, that’s a felony.

“Aunt Marvella kept her figure even after her fifth child.”

Chain-smoking and drinking shot glasses of bourbon every night probably helped Aunt Marvella but it didn’t do a lot for my cousins, two of whom have been in rehab for as long as I can remember.

It’s true that parents compare kids and everyone else’s kids seem to turn out better. Doesn’t it ever occur to them that we’re all lying? That Phi Beta Kappa snorts coke every weekend, and Marvella’s youngest, the one who went to medical school? She’s anorexic and losing her teeth.

Claudine believes that secrets keep relationships alive. I met her at the Food Co-op eighteen months ago but she’s never been to the house. We meet at her condo or on the getaway weekends we try to do every few months. I tell Calvin I’m at a book club retreat. I’m not even in a fucking book club because I work at a library.

During the day, I sort books and recommend them to people who come to our beautiful coastal library. I plan author events and I never have a shortage of reading material. It pays enough for half the mortgage of the house we jointly own. I’m not sure what part of this is confusing but we get asked questions all the time.

“You own a house with a guy who isn’t a lover or relative? Just a friend?”

“Yeah. We met in college. Works out great most of the time.”

“What does he think when you...bring people home?”

“He’d be fine with it except we don’t.”

“So, you don’t like...go out.... or get involved with anyone?”

“Nope. Like my space. Calvin likes his.”

And then comes the line that gets thrown at me again and again.

“You just haven’t met the right person.”

“Actually, I have. We’re compatible mostly—just not that way.”

I don’t understand all that fuss over relationships. They are messy and complicated and if you’re a cis man or woman, there’s the possibility of pregnancy or disease. I like kids as well as the next person but I don’t need to replicate my defective genes and be responsible for another human for eighteen years. Calvin is a little more flexible on this one and we’ve talked about artificial insemination or adopting but decided a dog would be easier—and they don’t live as long.

When Calvin brought Teddy home, it defied everything we’d agreed upon. Teddy cooked us a chicken dinner, made a batch of strawberry daiquiris and guacamole while dinner was cooking. He even cleaned up after and served a chocolate flan. I just knew he was trying to weasel his way into our sweet set-up.

“But Bertie, we have an extra room. He could help with expenses.”

“It’s hard enough to live with you, Calvin. I don’t want to get used to a whole other person.”

Pretty soon, Teddy was staying over on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Some nights Calvin didn’t come home. When he posted his relationship on Facebook and Instagram, I figured things were changing faster than I expected.

“My life, Bertie. People change. I didn’t know what I was missing and now that I do, I’m not going back.”

Then I saw the ad on Craigslist.

For Sale: three-bedroom bungalow on the east side of town. Two baths, mudroom, deck.

The photo was undeniably our house. I printed the ad and slipped it under Calvin’s door with a big ? on it. When I returned from work the next day, there was a handpainted sign on the little patch of lawn we have: For Sale by Owner.

“What the fuck? I own this house too!”

“I’m the primary and you’re the secondary. I don’t have to ask you to put it on the market. I want to live with Teddy now.”

Although I was trying not to lose it, it seemed more and more likely I was going to hurt someone or break something. Fucking Teddy with the perfectly done roasted fucking chicken and the melt-in-your-mouth flan. That’s when I thought to Google him. Ted (maybe Theodore) Gutkowski. There he was on Facebook and Instagram as well as all kinds of hook-up sites. Described as self-made man whatever that is, works at a local community college as a counselor. I’ll bet he’s effective. Divorced, two kids. I print six pages about Teddy and leave them on Calvin’s unmade bed. On the way out, I add my phone number to the For Sale sign on the front lawn.

I hate mudrooms. The very name suggests dirt. What ever happened to garages or just leaving your muddy shoes outside the door? My next house is going to be twobedroom and I’ll use the other one as an office. Wallpaper borders and ceiling fans and maybe an entertainment center. I look on Zillow, see at least four possible properties, all of them closer to my job. That’s when Calvin bursts in my room without knocking.

“That was low, even for you, Bertie. Snooping on my boyfriend.”

“Googling someone isn’t snooping. That information is out there for anyone to find. Your precious Teddy has kids,” I say.

“You think I didn’t know that?” he says in a tone of voice that makes me certain he didn’t.

“Yup. Kids, Cal. Different game.”

Calvin sits on my bed. Excuse me. My bed is off limits.

“Get off. I didn’t say you could sit there,” but he’s crying so I let it go.

“I fucked up. I really like Teddy. What do I do now?”

“For starters, take down that Craigslist ad, change your relationship status on Facebook, and get that fucking sign off of our lawn.”

Calvin is still sitting on my bed, sniffling into his hand.

“I’m still going to see him, you know.”

“I don’t care what you do when you’re not at home.”

That’s how we decided to turn the mudroom into an entertainment center with a wallpaper border and a huge television. We left a little square by the door with pegs for hanging up coats and a rack for dirty shoes. Next week we’re going to the animal rescue to look at dogs. I see no reason to tell him about Claudine. What I do in my free time is my own business.

Luke Morgan

Luke Morgan is an Irish poet. His third collection “Blood Atlas” is new from Arlen House in 2025 and was completed with the assistance of a bursary from The Arts Council of Ireland. He is the recipient of the Lawrence O’Shaughnessy Award 2025. He lives and works in Galway, Ireland.

Two Parades

We watched from the Claddagh artists from Macnas puppeteering their giant amphibian named Alf with blinking eyes, steering his paper-mâché head toward children who had the glare of their parents’ phones ignored in the briefly shimmering air.

Nights later, thousands of folks lined O’Connell Street for a parade that did not happen – a hoax. The social media brigade quickly took to points-scoring –misinformation and its effect –but in the photos from this outpouring on those who’d failed to fact-check

I saw vacant silhouettes starved behind the structures cold made of their breaths for fire, drumbeat, sculptures of newts hewn from kitsch –a great connective stem rendered by the streetlight which, alone, could not reach them.

Mathematics

Given they did not believe that one was a number, according to Aristotle, Archimedes, and the other great mathematicians, I do not exist on this anonymous Sunday as the hours tottle up to night outside my country home.

These days between subtracted summer and added winter are the realm of twos –hands held at a Christmas market, the possibility of root vegetables in a pot before work is finished, an ultrasound polaroid tacked to the door of a dyadic fridge.

Instead, I define my tidy life with the cold stock-taking of the calculator –enough money, enough time, more books than I could ever hope to read, my face by lamplight in a window like an abacus bead the world forgot.

No Funeral

The Royal College of Surgeons collected her body and we were left with no God to pretend in front of; no trays of sandwiches adorned a room, no uncle quipped about how she didn’t believe in any of this; no bloated tyres signalled the arrival of in-laws, gaudy neighbours, those of increasingly tenuous connection blessing themselves out of some clumsy trend to consider her wax-like non-self mourned; we were left with no grey morning, no awkward bow before the shuffle into pews, no gentle fires of tall candles, nor greetings whispered out of affection for a place unfamiliar and familiar as a church; no cold marble floor shocked our knee-bend and no perfume-choked hugs from high-fliers who were sorry for our loss, but keen to lurch on what our plans would be, just the same; above all, no mass card, made with the lend of a flash-flattened photograph taken on a warmed Mediterranean bench of her smiling, now above no fridge stocked with all a loss requires; fruit salad, smoked salmon, a potato dish without a name; while no kettle nearing overspill invited no old and cherished friend who grabbed hold of our shoulders, scorned by the sorrow these occasions avow to make us roar with laughter, despite the criers; celebrate the living, the living still.

Magdalena Ball

Magdalena Ball is a novelist, poet, reviewer, interviewer, Sustainability Manager, Vice President of Flying Island Poetry Community and Managing Editor of Compulsive Reader, one of Australia’s most respected online review sites, which has been publishing high quality book reviews since 1997. Her work has appeared in an extensive list of journals and anthologies, and has won or listed in many local and international awards, including, in 2023/24, the QRAA Ekphrasis Challenge, the Melbourne Poets Union International Poetry Competition, the SCWC Poetry Award, the Liquid Amber Press poetry prize, the University of Canberra ViceChancellor’s international poetry prize, and the Woollahra Digital Literary Award, as well as shortlisting for a Red Room Poetry Fellowship. She is the author of several novels and poetry books, most recently, Bobish, a verse-memoir published by Puncher & Wattmann in 2023.

Spot Fires

In the Walkman era love letters were mixtapes scattered across an apartment floor spot fires, capitulation do the thing, say anything to get you home. A compliment that raises the hair on your arms. Plastic film scattered across a bedroom that no longer exists.

The stereo system of your dreams playing on repeat in another dimension.

The body is an answering machine leaving a message for a future self the sound held for decades delicate and enduring as glitter.

Fire & Moon

Acrostic after Fire & Moon 1 by Vyvian Wilson (2012)

First I dreamt of fire chimera without fear in an ocean that melted into air my body also liquid raging and lost crashing waves emptying breath the long night & later, in the darkness of predawn I was there still

morning as light purple shadows over another tableau texture of what was yet to come on the surface there was nothing to tell but below a rising chaos no sunrise could dissipate.

Money box

boxes for dollars cells for a shrinking heart

coffee ring laminate text to column

sunlight for fluorescent trees for a migraine

the money box never lies statisticsa different lifeform

always a few minutes later than you needed

it adds up if you don’t check the backend

the wind is getting up but cells hold me

such soft lines, I never imagined this would be the way we’d end

tapping out seconds left-aligned bullet points

picking up the pressure breaking code

Michael Farry

Michael Farry’s latest poetry collection, his fourth, An Apology for our Survival was published

Rescuing Don Quixote

The last knight of Europe looked me in the eye lean and foolish on the stalls of Malvern— those rusting cast-off acres, the residue of progress—his sword stolen, his servant fled. I had no option but to pay the ransom promise to rearm him, supply a valet,

to display him in a place of honour. I’ve studied chivalry, read the romances and seen enough of worn-out nags to know the story’s faulty, the ending fatal. Sometimes you just grab what’s splayed before you even if it’s foreign and overpriced

so I paid the man and took the wooden piece. My sidekick cynic mocked my innocence, queried my forging skills, asked what my children would say, where on my overburdened shelves I could display him. I’ll find room I told him, above the row of European novels

I’ve still to read, Mann, Undset and Conrad. Yes, there were other useless treasures there had we the time—that railway sign our fathers would have cherished, too heavy for the train, the stained glass panel, angel poised to help, too pious for today. We leave so much behind, the time short, our energy low. But where in this vast paddock is my trusty car? We walk, aisle by aisle, for hours, then find it by its number plate, drive off along a straggling road towards the distant blue hills, the cider farm, the festival, the last knight of Europe safe in bubble wrap.

by Revival Press, Limerick in 2024. A historian as well as a poet, he has published widely on the history of the Irish war of independence and civil war in Sligo. He lives in Co Meath, Ireland.

Cut Throat Lane, Ledbury

Its swashbuckling name entices you like a silver cross on a white neck or the splash of accidental blood

Then narrows as the lush hedges close like the gloom swallowing a galleon in a winter’s evening dying daylight

Mocking your ignorance and gullibility like the photo of an infamous ancestor a mirror reflecting the unnoticed

And what keeps you going is terror like the whisperings in the night time the black spot in the summer garden

Until you do reach the main road like a raindrop finding a friendly stream a tributary welcoming extinction.

Back home, the name demands attention like a family legend you can’t forget or an old sports injury which still nags.

Men in Suits

The men in suits are lost

outside the windswept porch beleaguered by hail and guilt waiting to be assigned their stations, front or back, left or right to bear the casket’s dead-weight

in the corners of the function room floundering in noose-tight ties checking their lists, punch lines their not-so-funny-now tales of youthful misdemeanours

along late-night gravelled aisles unsteady, half blind, shirts loose, shoes muddied, searching for stones above coloured pebbles their names and dates, alphas to omegas,

rehearsing apologies, excuses even prayers, like drunken muttered retorts to insults hurled across a public lounge or like, in a single room, the unburdening of half a century’s heartache

They find no answer, no accord in church, hotel or silent graveyard.

Neil Leadbeater

Neil Leadbeater is an author, essayist, poet and critic living in Edinburgh, Scotland. His work has been published widely in anthologies and journals both at home and abroad. His latest publications are ‘Italian Air / Radiant Days’ and ‘Cycling to the End of the World’ (both published by Cyberwit.net, Allahabad, India, 2024 and 2025). Other publications include ‘Librettos for the Black Madonna’ (White Adder Press, 2011); ‘The Loveliest Vein of Our Lives’ (Poetry Space, 2014); ‘The Fragility of Moths’ (editura pim, Iași, Romania, 2014); ‘Sleeve Notes’ (editura pim, Iași, Romania, 2016); and an e-book, ‘Grease-banding The Apple Trees’ (Rafaelli Editore, Rimini, Italy, 2015). His work has been translated into Chinese, French, Dutch, Nepali, Romanian, Spanish and Swedish.

Birmingham Botanics

Heeling south: agapanthus in a light breeze scrawls its signature in bright blue-ink across the boundary wall.

The glasshouses, hot as gossip, swelter in the heat.

Office workers with sweat on their palms flood in at noon.

Half an hour of peace from the constant trilling of phones.

In the far corner the foxgloves are having a field day flaunting themselves in a riot of pink: bells for the bees.

Unforgettable Moments

Strawberry fields in Sefton Park / Visiting the Bluecoat Chambers / art at The Walker / Pre-raphaelites in the Lady Lever / the Isle of Man steam packet docked at the quayside / Gerry and the Pacemakers singing Ferry ’cross the Mersey / calling in at the Sudley for Strudwick’s ‘St. Cecilia’ or the fanciful informality of Leighton’s ‘Sunny Corner’ / hearing Widor’s Toccata in the high Anglican Cathedral / Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana at the Philharmonic Hall / the pride of Cammell Laird / views of the Clywdian Hills from the windows of Woolton Manor /Beatlemania at The Cavern / the song I will always remember: Norwegian Wood

Maltese Pearls

are the white olives of the Mediterranean bajda in the original— blushed by brine to a pale ivory (think of white canellini beans or say bianca or biancolilla and everyone will know what you mean). Held in high esteem, they are sacramental oil, gifts from God shaped like crescent moons.

How readily you place them pearlescent in your mouth.

Pistachio

Say it out loud and it is almost like sneezing— that ‘semi-autonomous, convulsive expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth’— that makes you think of hayfever, salad dessert and pollen, of the terraced orchards of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and northern Iran: a Silk Road indulgence in the dustbowl of summer.

Noel Monahan

Noel Monahan is a native of Granard, Co. Longford, now living in Cavan. He has published seven collections of poetry with Salmon Poetry. An eight collection, Celui Qui Porte Un Veau, a selection of French translations of his work was published in France by Alidades, in 2014. A selection of Italian translations of his poetry was published in Milan by Guanda in November 2015: “Tra Una Vita E L’Altra”. His poetry was prescribed text for the Leaving Certificate English, 2011- 2012. His play: “Broken Cups” won the RTE P.J. O’Connor award in 2001and Chalk Dust, a long poem of his, was adapted for stage and directed by Padraic McIntyre, Ramor Theatre, 2019. During the Covid-19 lockdown, Noel had to reinvent his poetry readings and he produced a selection of Short Films: “Isolation & Creativity”, “Still Life”, “Tolle Lege” and A Poetry Day Ireland Reading for Cavan Library,2021. Recently, he edited “Chasing Shadows”, a miscellany of poetry for Creative Ireland. His ninth poetry collection, “Journey Upstream” was published by Salmon Poetry in April 2024.

Canticle

That distant joy Of one having recalled Fields full of happy memories Far beyond the potato drills.

Sometimes A Divine spark Comes alive for us In a Line of poetry

And we can return To that distant joy Beyond the drills If only for a short moment.

Paris Rosemont

Paris Rosemont is a Thai-Australian poet and author of Banana Girl (2023) and Barefoot Poetess (2025). Her poetry has been widely published and awarded worldwide, including first place in the Hammond House Publishing Origins Poetry Prize 2023 (UK) and Honourable Mention in the Fish Poetry Prize 2025 judged by Billy Collins. Paris has been on judging panels including the Western Australian Premier’s Book Awards 2025, and her books have been shortlisted for awards in Australia, Greece, the UK and USA. She is a member of the Randwick City Council Arts & Culture Advisory Committee and sits on the Hunter Writers’ Centre Board. Paris may be found at www.parisrosemont.com

Diomedea

Contemporary sonnet after Lois Herman’s artwork ‘Ghost Vessel’

Out on the slategrey horizon—the very same shade as my lost lover’s eyes, a humble sailboat skims the waves through spitting sleet and sheets of fog. Its hull an urn for secrets kept, for summers past, for dreams stillborn. Its sails of snow unfurl like wings: an albatross in search of rest.

Mary Smokes Weed

A stakehouse sonnet (after Mary I, aka ‘Bloody Mary’)

CONTRARY Mary, how your garden grows

Enriched with blood and bone of those who sinned: Those smokin’ lads all lit up in a row; Your savageness burst forth from wounds within.

REJECTED child, violently wild you grew; With barren seeds and tangled weeds you choked. Your father’s love you barely ever knew Because of that vile wench on whom he’d dote.

A BASTARD child: your new station in life

So he could take his paramour to bed Legitimately making her his wife; At least you got to keep your pretty head.

OH, MARY—your name lingers on the lips Of folks who lap you up in little sips.

Remnants (a haiku series)

(i) staring at fine cracks in the ceiling—remnants of a great depression

(ii) out of compost springs new life—an onion—beauty worth crying over

(iii) wobbling through heat haze spitting on hot tin bonnet eggs sunny side up

(iv) whip bird pierces air thundercrack of blue fragments punctuating peace

Raine Geoghegan

Raine Geoghegan, (she/her) is a prize winning multi-disciplinary artist with an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Chichester. Born in the Welsh Valleys, she is of Romany, Welsh & Irish ethnicity. Her work has been nominated for the Forward Prize, Pushcart Prize, Michael Marks Award and ‘The Best of the Net.’ It’s been published with Poetry Ireland Review; Travellers’ Times; ‘The Royal Literary Fund’ and many more. Her essay, ‘It’s Hopping Time’ was featured in Gifts of Gravity & Light (Hodder & Stoughton, 2021). She has three pamphlets published with Hedgehog Press. ‘Apple Water: Povel Panni’ was listed in the Poetry Book Society Spring 2019 Selection. She is the Romani Script Consultant for the musical ‘For Tonight’. ‘The Talking Stick: O Pookering Kosh’ was published in June 2022 with Salmon Poetry Press. She has read at festivals in the UK, Ireland and Sydney. She is the curator and editor of ‘Kin’ an anthology of Gypsy, Roma & Traveller Women Writers and Artists, with Salmon Poetry Press.

Words for Maya Angelou

She sits quietly, waiting for words to rise like bubbles from the pit of her stomach. Some have hardened like stones, lingering in the darkness. They make no effort to come to the surface. Once they were free, floating in the forest with the leaves, warming themselves under the sun. Some fly out of her mouth, moths seeking the light. Others slither and slide, not knowing which way to go Some jump like frogs onto the page, wet and beady eyed. When she tries to grab them, they hop away. Words fly, fall; like leeches they stick to her clothes and make her cry. They swim, tiny fishes through her veins, into her fingers. They live. This is enough.

Charlie Chaplin and the Gypsy Flower Seller

She stood outside the Bull in the Old Kent Road, the basket of flowers resting on her hip. Her name was Rosalie, one of the Lees, a Romany family who camped at the end of the lane. They went hop picking every September to Kent, his brother Sydney went too. She liked tosing and she was jolly good. When she saw him she’d say, ‘Ello Charlie boy, ‘ow yer doin, flowers fer yer ma is it’? She knew that on pay day he’d buy his mother a bunch of carnations. She always gave him a few extra and he used to stop and chat with her. Walking home, clutching the flowers, he’d think of how Rosalie resembled Hetty, the girl that got away. She had the same almond-shaped brown eyes, long lashes, and that smile, just like Hetty. He courted her for a while when they were on the same bill at the Streatham Empire and oh how she could dance and flash those lashes.

‘One day, I’ll make a film, I’ll ask Rosalie to play the part of Hetty. I’ll teach her the craft of acting, how to look straight at the camera. She’d be perfect. I’d have to think of a story, something that would make people laugh and cry but now I’ll get home, parley with ma in the kitchen over a cup of char, tell her all about my plans to be a filmmaker, how I’ll change the world. That’ll make her happy. I got to try something. I got to lift her spirits somehow.’

My Father Used to Tell Me

People ask me. ‘Are you a Gypsy Charlie?’

I’d like to tell them about my beautiful grandmother. She had jet black hair, the darkest of eyes, the sharpest of insight, the Gypsy gift.

But I simply say.

‘My father used to tell me that there’s Gypsy blood, running though our veins, but I’ve never trusted him, you know’.

Richard W. Halperin. Photo credit: Joseph Woods.

Richard W. Halperin’s poetry is published by Salmon/Cliffs of Moher (four collections) and by Lapwing/Belfast & Ballyhalbert (eighteen shorter collections). In 2025-26 Salmon will bring out All the Tattered Stars: New and Selected Poems, Introduction by Joseph Woods. Many videos of Mr Halperin’s readings in Ireland are on the internet (e.g., Achill Island; Limerick; University College Dublin Irish Poetry Reading Archive).

Before sleep, thoughts come.

Before sleep, thoughts come.

If thoughts come during the day, I am not very concerned with them. They are part of the day, not part of me.

Before sleep is different: sleep and I are caught in the same strands. Maybe we were born at the same time.

Before sleep tonight, I think of Arthur Waley’s 170 Chinese Poems. The best use of English since Jane Austen’s, not a speck of dirt on it.

One of the poems is ‘General Su Wu to his wife,’ circa 100 BC:

‘And if I die, we will go on thinking of each other.’

That is my wife and I. She died. Here I am. Here we are.

Before sleep.

Watch and Pray

But I fell asleep. That was most of my life. That is still most of each day. Sometimes I watch. Sometimes I pray. Rarely both.

This morning, both. I heard ‘Let the dead bury their dead.’

All the adults in my life are dead.

I have been left, adultless, in the department store, with others, also adultless.

I watch, not knowing what I watch. I pray, not knowing what prayer is.

Even Vishnu – I think of ‘The Bell Song’ –is lost in the forest, Brahmaless.

A pariah saves him from wild beasts with her little bells.

When I write, when I was with my wife, when I die laughing in conversation with pals, little bells.

Higher and higher, little bells.

Cured of His Blindness

In Damascus my wife and I visited the house where Paul was cured of his blindness. This was part of our life together, because who could explain that either?

Turgenev belongs in this poem, so here he is. He had to make Bazarov the centre of Fathers and Sons but didn’t understand the man at all. So, over eighteen months, he meticulously wrote Barazov’s diary. Then he destroyed it and began the novel.

My poems are Barazov’s diary. All of them, even the political ones, are love poems, so that I can begin to understand who my wife and I actually were.