with Kentucky Explorer

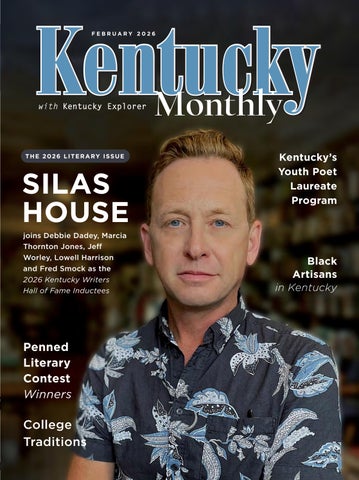

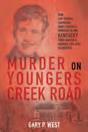

THE 2026 LITERARY ISSUE

with Kentucky Explorer

THE 2026 LITERARY ISSUE

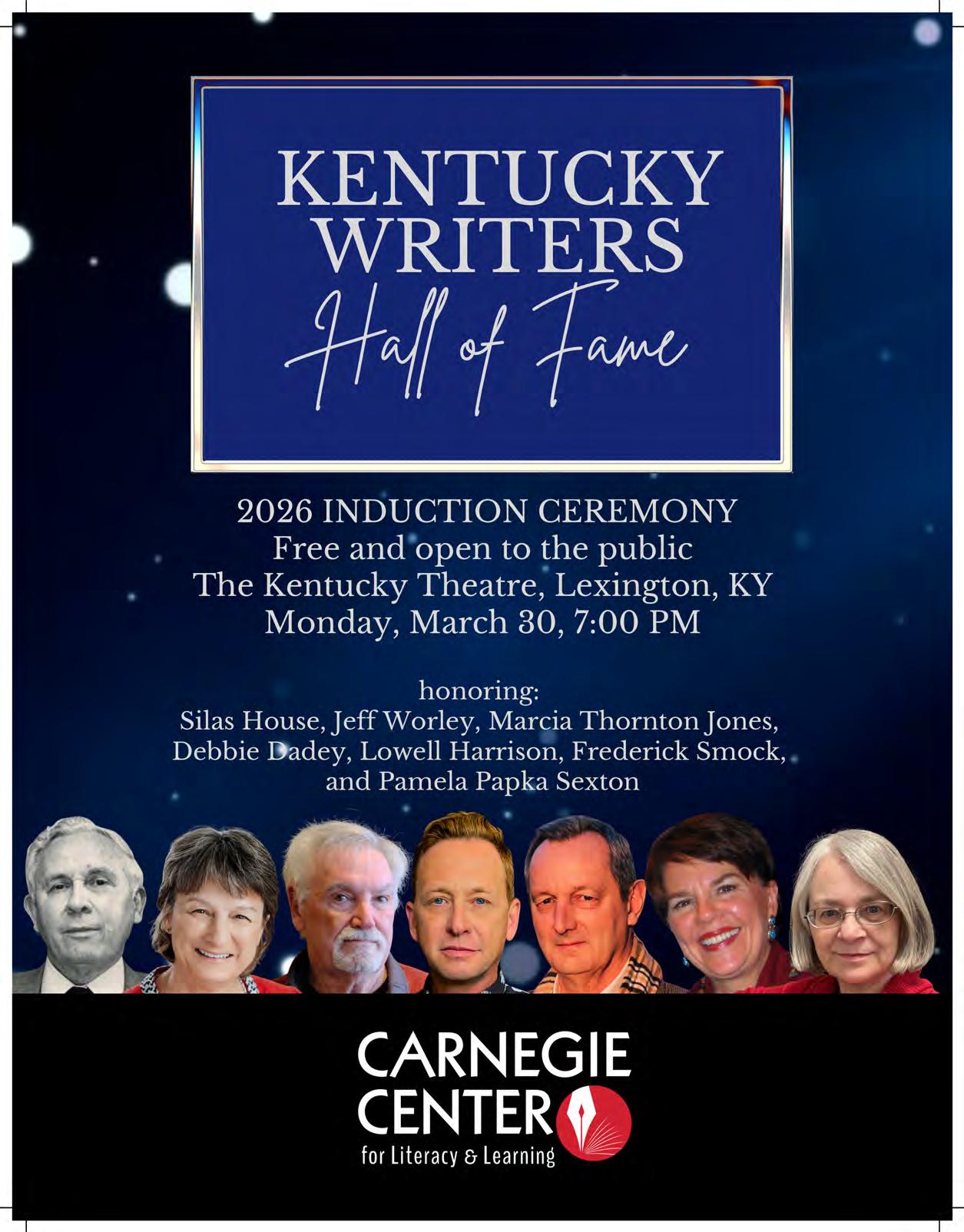

joins Debbie Dadey, Marcia Thornton Jones, Jeff Worley, Lowell Harrison and Fred Smock as the 2026 Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame Inductees

Youth Poet Laureate Program

Black Artisans in Kentucky

Penned Literary Contest Winners College Traditions

Back-to-back

2023-2024 & 2024-2025

85.5%

First-to-second year retention rate

Textbooks and course materials for all students

Nearly 1 in 4 of first-year students receive the UPIKE PLEDGE

A full-coverage scholarship for Kentucky residents who display full eligibility for Pell, CAP and KTG grants

Writers

Inductee

39 Thinking Bigger A Mount Sterling arts organization helped launch Kentucky’s Youth Poet Laureate Program and gave young writers a public voice

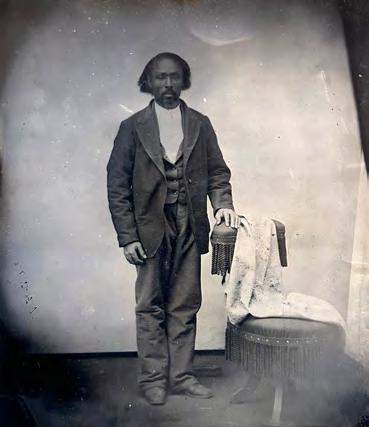

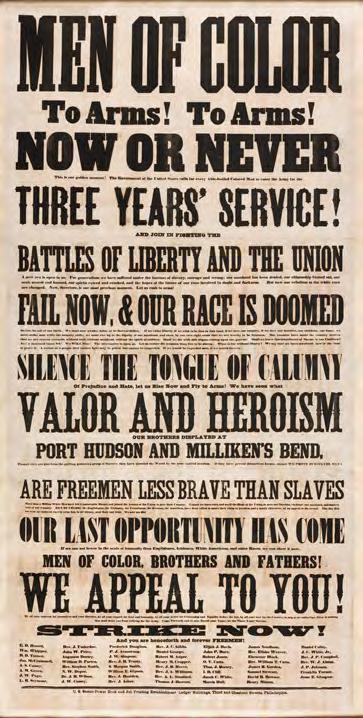

43 Rising to the Call Louisville’s Speed Museum honors Kentucky’s Black artisans who contributed to the cause of liberty in the 19th century

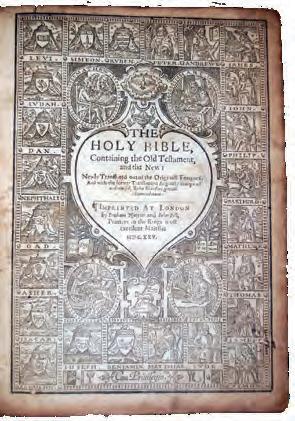

The Kentucky Historical Society and the Louisville-based National Society Sons of the American Revolution are two of the many groups (including the Daughters of the American Revolution and First Families of Kentucky) organizing special events this year to honor the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence on July 4. Look for many references to these events in Kentucky Monthly this year.

1. During the Cherokee War of 1776, “The Savage Napoleon” led the indigenous people in raids, ambushes and skirmishes against the 500 settlers who called “Kentucke” home. His Cherokee name was Tsiyu Gansini, but he was called what in English?

A. Fallen Timber

B. Dragging Canoe

C. Howling Coyote

2. Richard Henderson, the namesake of both the present Kentucky city and county, attempted in 1775 to colonize Kentucky as the 14th colony under which other name?

A. Transylvania

B. Franklin

C. West Carolina

3. Col. Johannes “John” Bowman, along with his three brothers, were called the “Four Centaurs of Cedar Creek.” They presided over the first what in Kentucky?

A. Horse race

B. Beauty contest

C. County court

4. John Todd (1750-1782), the grandfather of Mary Todd Lincoln, co-founded which Kentucky city?

A. Elkton

B. Lexington

C. Leestown

5. Benjamin Logan, who died in Shelby County, founded Logan’s Station—also known as St.

For answers, see page 4.

Asaph’s—just northwest of which present-day Kentucky city?

A. Harrodsburg

B. Danville

C. Stanford

6. In 1774, James Harrod and 37 men led an expedition into present-day Mercer County under orders from Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of which colony?

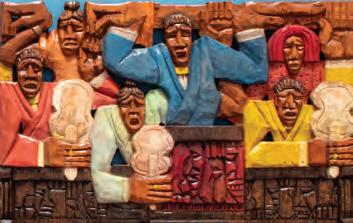

A. Maryland

B. Virginia

C. Pennsylvania

7. In 1739, Frenchman Charles III Le Moyne is credited with discovering which Kentucky landmark?

A. The Falls of the Ohio

B. Mammoth Cave

C. Big Bone Lick

8. On July 14, 1776, two Cherokee and three Shawnee warriors captured the daughters of which noted pioneers?

A. Daniel Boone and Simon Kenton

B. Simon Kenton and Richard Callaway

C. Richard Callaway and Daniel Boone

9. Ownership of the land we call Kentucky has been held by numerous groups and nations, including New France until 1763 and France’s loss of which war?

A. Lord Dunmore’s War

B. Queen Anne’s War

C. French and Indian War

©2026, VESTED INTEREST

PUBLICATIONS VOLUME TWENTYNINE, ISSUE 1, FEBRUARY 2026

Stephen M. Vest Publisher + Editor-in-Chief

EDITORIAL

Patricia Ranft Associate Editor

Rebecca Redding Creative Director

Deborah Kohl Kremer Assistant Editor

Ted Sloan Contributing Editor Cait A. Smith Copy Editor

SENIOR KENTRIBUTORS

Jackie Hollenkamp Bentley, Jack Brammer, Bill Ellis, Steve Flairty, Gary Garth, Kim Kobersmith, Brigitte Prather, Walt Reichert, Tracey Teo, Janine Washle and Gary P. West

BUSINESS + CIRCULATION

Barbara Kay Vest Business Manager

ADVERTISING

Lindsey Collins Senior Account Executive + Coordinator

Account Executives: Kelley Burchell Laura Ray • Teresa Revlett

Kentucky Monthly (ISSN 1542-0507) is published 10 times per year (monthly with combined December/January and June/July issues) for $25 per year by Vested Interest Publications, Inc., 102 Consumer Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601. Periodicals Postage Paid at Frankfort, KY and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Kentucky Monthly, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602-0559.

Vested Interest Publications: Stephen M. Vest, president; Patricia Ranft, vice president; Barbara Kay Vest, secretary/ treasurer. Board of directors: James W. Adams Jr., Dr. Gene Burch, Gregory N. Carnes, Barbara and Pete Chiericozzi, Kellee Dicks, Maj. Jack E. Dixon, Mary and Michael Embry, Judy M. Harris, Jan and John Higginbotham, Frank Martin, Bill Noel, Walter B. Norris, Kasia Pater, Dr. Mary Jo Ratliff, Randy and Rebecca Sandell, Kendall Carr Shelton and Ted M. Sloan.

Kentucky Monthly invites queries but accepts no responsibility for unsolicited material; submissions will not be returned.

My mother passed away in 2025, and she marveled over your magazine. Thanks for keeping her updated about all of the great things in Kentucky.

Gary Gribble, Essex, Maryland

My brother and I really appreciate your wonderful Kentucky articles, photos, poems and stories.

I enjoy the unique writing and reading you provide.

Leslie Dodd, Lexington

Pertaining to your mention of KET in its early days (October issue, page 52) and “Uncle Bert” T. Combs, a sibling of my mother, here’s a bit of background on how KET went from a thought to actual production: Uncle Bert was born and grew up in Eastern Kentucky, with educational guidance from his mother, Martha (my grandmother), who thought those in poverty might be able to rise via education.

Lois Combs Weinberg and I are the same age and have been appreciative of Bert

Combs’ uplifting actions for Kentucky. A bit of history is being offered to understand more fully why. He worked his way through college, as well as law school, with many tales that are inconceivable in today’s world. He also participated in World War II, and was an attorney and a judge after war. His interest in education stemmed from the past.

Most of us might forget that when Combs was elected governor, part of the platform was to create a sales tax to partially help support higher salaries for the educational community. His administration developed the Mountain Parkway to bring commerce to the eastern part of Kentucky. Uncle Bert was always open minded and sought out solutions to improve Kentucky’s education.

It was about this time, the 1960s, that his association with Leonard Press and others were developing the notion of helping educate the public via public TV. Unfortunately, the leader of our government has decided that KET and NPR are not worth the government support. Where else can you find programs such as Masterpiece Theater, Ken Burns series, objective reporting, and the education it provides our citizens?

Ben C. Kaufmann, Lexington

We Love to Hear from You! Kentucky Monthly welcomes letters from all readers. Email us your comments at editor@kentuckymonthly.com, send a letter through our website at kentuckymonthly.com, or message us on Facebook. Letters may be edited for clarification and brevity.

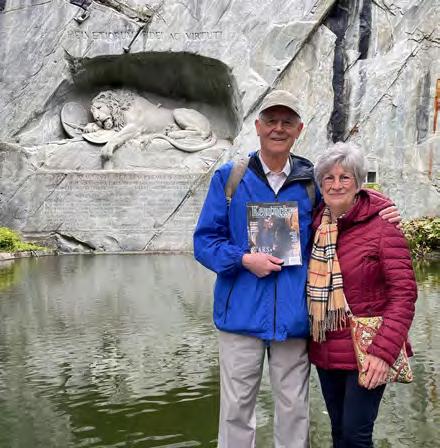

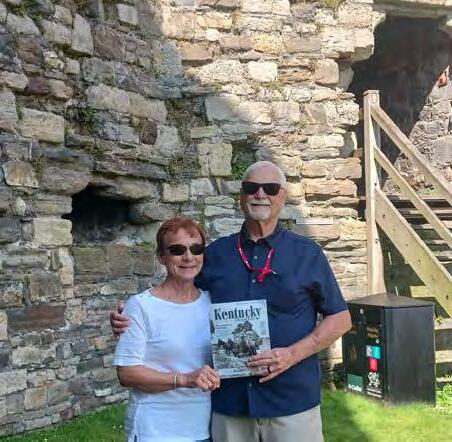

Even when you’re far away, you can take the spirit of your Kentucky home with you. And when you do, we want to see it!

Frankfort residents Richard and Sally Smothermon ventured to Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein and Germany. They are pictured in Lucerne, Switzerland, in front of the relief sculpture often referred to as the “Lion of Lucerne,” which commemorates more than 700 Swiss Guards who were killed in 1792 during the French Revolution.

KWIZ ANSWERS

SUBMIT YOUR PHOTO

Take a copy of the magazine with you and get snapping! Send your high-resolution photos to editor@kentuckymonthly.com or visit kentuckymonthly.com to submit your photo.

Patricia Dorton Whitaker and Morris Hunter of Maysville visited the ancient Beaumaris Castle on the island of Anglesey in Wales. Construction began on the concentric, symmetrical stronghold in 1295, but the castle was never completed. It is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

1. B. Dragging Canoe was a formidable champion of resistance to colonial expansion; 2. A. The short-lived colony got its name from Henderson’s Transylvania Company, which engaged in land speculation; 3. C. John Bowman, whose grandson founded the University of Kentucky, was the state’s first justice of the peace, county-lieutenant and military governor; 4. B. John Todd was killed fighting at the Battle of Blue Licks, and a county is named in his honor; 5. C. Stanford is Kentucky’s second-oldest city; 6. B. Kentucky was a part of Virginia until it attained statehood in 1792; 7. C. In 1744, fur trader Robert Smith confirmed Charles III Le Moyne’s discovery of large fossils and bones; 8. C. Elizabeth “Betsy” and Frances “Fanny” Callaway and Jemima Boone were rescued three days later; 9. C. The French and Indian War raged from 1754-63 between Great Britain and France and their respective Native American allies.

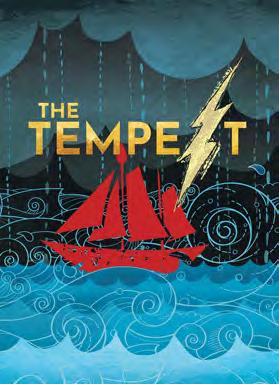

Murray State University’s 2026 Shakespeare Festival features two plays by the bard. Romeo and Juliet will be performed onstage at MSU’s Lovett Auditorium March 4-5 at 10 a.m. The curtain rises on The Tempest at the auditorium March 6 at 7 p.m. and March 7 at 2 p.m. Free tickets are available before each performance at the auditorium.

The Tennessee Shakespeare Company (Memphis) presents Romeo and Juliett, and Kentucky Shakespeare (Louisville) performs The Tempest. School group tickets can be arranged in advance.

Since 2001, the Murray Shakespeare Festival has brought high-quality productions to the Four Rivers Region. More than 10,000 students, teachers and the general public have attended at affordable prices or no cost. Throughout performance week, the festival offers free programming, including on- and off-campus lectures, hands-on experiences and community programs.

For more information, contact Dr. William R. Jones, chair, Murray Shakespeare Festival Department of English and Philosophy, wjones1@murraystate.edu, 270.809.2397. Follow the festival on Facebook or consult the MSU website, murraystate.edu/shakespeare — Constance Alexander

The Boone County Public Library in Burlington has received a $25,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) for Celebrating America250: Arts Projects Honoring the National Garden of American Heroes for outdoor mural wall panels featuring American trailblazers through their words, actions and advocacy.

“Libraries are places where stories are preserved, shared and brought to life,” said Julie Althaver, grant writer for the BCPL. “This project allows us to take history beyond our walls, using public art to honor American heroes, while inviting reflection, learning and conversation as we approach the nation’s 250th anniversary.”

This project consists of an outdoor exhibit at the main library featuring eight mural wall panels each measuring 8 by 16 feet. The panels will showcase three images of individuals identified as American heroes by Executive Order 13934, issued by President Donald Trump

Those chosen for this exhibit have Kentucky ties or have advanced freedom, justice and equality through the power of their words. For information on the other 49 projects, visit arts.gov/news

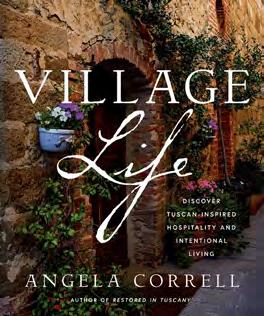

When Stanford author Angela Correll and her husband, Jess, found a deep connection with the Tuscan region of Italy during visits there, they decided to purchase a house, which they have since made into a comfortable, cozy home. An author of several books, including the May Hollow Trilogy of novels, Angela wrote Village Life: Discover Tuscan-Inspired Hospitality and Intentional Living to share the connection to “art, beauty, craftsmanship, creation, a slower pace, a nurturing meal, a rhythmic period of rest, and long walks in nature.” In Village Life, Angela shares recipes, a few of which are featured here.

Text and images reprinted with permission from Village Life: Discover Tuscan-Inspired Hospitality and Intentional Living by Angela Correll, copyright ©2025. Published by Ten Peaks Press, an imprint of Harvest House Publishers.

SERVES 6

3 cups fresh ricotta (about ½ cup per person)

3 tablespoons white sugar

2 cups pine nuts

Honey, for drizzling

1. Whip the ricotta and add sugar to desired sweetness (this may be more or less than the 3 tablespoons recommended).

2. Lightly toast the pine nuts in a dry pan.

3. Put the whipped ricotta in a small dessert dish and top with a sprinkle of toasted pine nuts and a drizzle of honey.

SERVES 4-6

4 cups fresh basil

½ cup pine nuts

½ cup fresh Italian parsley

½ cup olive oil

3 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon salt

½ cup Parmesan cheese

1. Put the basil, pine nuts, parsley, oil, garlic and salt in a food processor and mix well.

2. Add the cheese and process until desired texture is reached.

Note: The pesto sauce can be frozen in pint or jelly jars for later use in flavoring pasta or pasta salad. It also can be spooned into ice cube trays, frozen overnight, then popped out and placed in a freezer bag for small amounts of flavoring for soup or vegetables, such as carrots or roasted potatoes.

SERVES 10-12

¾ cup all-purpose flour

Pinch of salt

¾ cup beer or sparkling water

Peanut oil for frying

24 clean, large sage leaves

Salt to taste

1. Mix the flour and salt and then add the beer or sparkling water, little by little, blending with a fork or whisking until it is well mixed.

2. Heat the peanut oil. You’ll know the oil is ready when you flick droplets of water into the oil and it sizzles.

3. Dip the leaves one by one in the batter and drop in hot peanut oil. When golden brown—under 30 seconds—remove the leaves with a slotted spoon and lay them on a plate covered with paper towels to drain the excess oil.

4. Sprinkle a bit of salt on top to taste. Serve hot.

1 large orange slice, halved Prosecco

Aperol

Sparkling water or club soda

1. Place one half of the orange slice in the bottom of a large wine glass. Fill with ice.

2. Add equal parts of prosecco, Aperol and sparkling water or club soda. Stir gently and garnish with the other half of the orange slice.

San Pellegrino sparkling water or club soda

Fruit juice

Simple syrup

Fruit slice or berry for garnish

1. In a glass, pour one part sparkling water or club soda and one part fruit juice.

2. Add simple syrup to taste, depending on the sweetness of the juice you choose.

3. Add a slice of fruit or a berry and stir.

Note: Depending on the fruit in season and preferences, try limes, strawberries, grapes, cranberries, raspberries, blueberries or oranges.

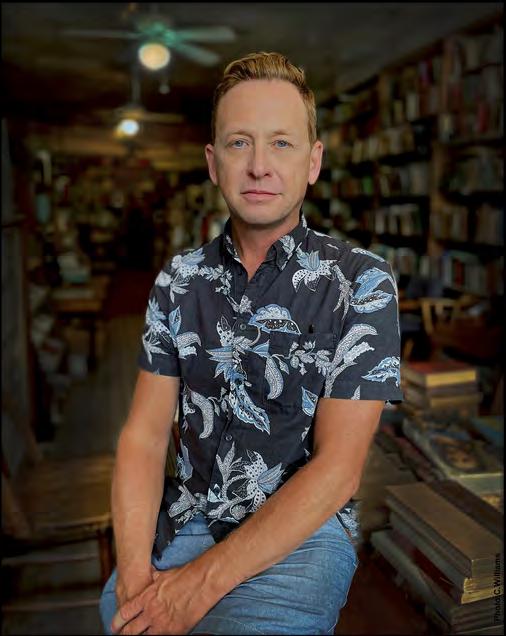

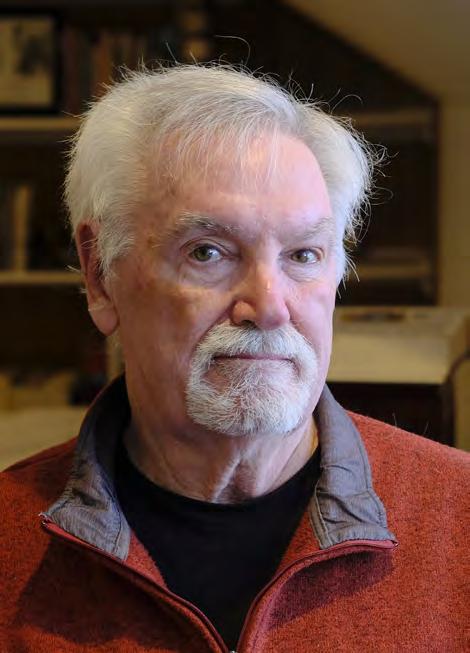

Silas House is one of Kentucky’s most acclaimed contemporary authors—a best-selling novelist and former Kentucky poet laureate who recently published his first two books in new genres for him: a collection of poetry and a mystery novel.

Marcia Thornton Jones and Debbie Dadey were Lexington educators 35 years ago, when they decided to write a children’s book. Now, often writing as a team, they have become among the most prolific and successful children’s authors in the business, with an estimated 46

million books sold worldwide.

Jeff Worley is a former Kentucky poet laureate who has published 10 poetry collections and more than 500 poems in journals. His poems sometimes display a mastery of something many modern poets often avoid: humor.

These four writers will be inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame this year, along with two deceased authors: Frederick Smock, an acclaimed Louisville poet and teacher at Bellarmine University, who died in 2022; and Lowell Harrison, a renowned Kentucky historian, author and longtime history professor at

Western Kentucky University, who died in 2011.

The induction ceremony, which is free and open to the public, will be at 7 p.m. on March 30 at the historic Kentucky Theatre in downtown Lexington. All four living inductees plan to attend.

Learn more about these Kentucky literary icons in this special section, written by Tom Eblen, a former Lexington Herald-Leader columnist and managing editor who is now the literary arts liaison at the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning in Lexington.

ilas House is one of Kentucky’s best-known literary figures: author of bestselling novels, plays and a nonfiction book; a former state poet laureate; an essayist in national newspapers and magazines; a music journalist; an editor and teacher; a social activist; a movie producer; a podcaster; and even a Grammy Award finalist.

Never one to sit still, House recently published two more books in the past few months in genres new for him: a poetry collection and a murder mystery, both of which have become national bestsellers.

And in March, House will become the youngest living inductee into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame. At 54, he shows no sign of slowing down.

“It means a lot to be voted in by your peers,” House said in an interview about his selection for the Hall of Fame, a joint project of the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning and the Kentucky Arts Council.

“I always have imposter syndrome about everything,” he added. “Some of that, I think, is what fuels an artist. It challenges you to keep going and to be better. Despite being published for so long, I still feel like I’m trying to earn my spot.”

House loves classic murder mystery novels, so he studied the form before writing Dead Man Blues under

the name S.D. House. Set along the Kentucky-Tennessee line, the novel has become a USA Today bestseller and a Barnes & Noble pick. He hopes it will be the first in a series of books.

House was even more serious about studying poetry before compiling his first collection, even though he has published occasional poems for more than a decade and was Kentucky’s poet laureate in 2023 and 2024.

“I mostly felt like an imposter as a poet for most of my writing career, because I had been trained formally as a prose writer,” he said. “And I really believe that if you’re going to call yourself something, then you really have to put in the 10,000 hours to earn that. So, I took a lot of poetry workshops and poetry classes. I studied with a couple of poets I really respect. I immersed myself in poetry,

especially during the pandemic. I devoted myself to the craft.”

The work paid off. His collection, All These Ghosts, is a finalist for the Southern Book Prize and has become a USA Today bestseller, an unusual feat for any poetry book. NPR’s Neda Ulaby interviewed House about the book in November.

Still, he hedged: “I want my fellow poets to know that I still feel very much like a greenhorn as a poet. But I think any good writer is always learning.”

House was born in Corbin and grew up in the nearby Laurel County community of Lily. He earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Eastern Kentucky University. He was working as a rural mail carrier in 2000 when the Millennial Gathering of Writers of the New South at Vanderbilt University chose him as one of 10 emerging talents in the region. Soon afterward, he sold his first novel, Clay’s Quilt, followed two years later by A Parchment of Leaves, which became an award-winning national bestseller.

House earned an MFA in creative writing from Spalding University. After being a writer in residence at EKU and Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee, he joined the faculties of Berea College and Spalding University.

His later novels include The Coal Tattoo (2005), Eli the Good (2009), Same Sun Here (2012, co-written with Neela Vaswani), Southernmost (2018) and C. Williams

Lark Ascending (2022), which won the 2023 Southern Book Prize. Little, Brown will publish his newest novel, The Tulip Poplars, an epic story that follows two couples over 70 years, this fall.

Four of House’s plays have been produced. He wrote a 2009 book of creative nonfiction, Something’s Rising, with Jason Kyle Howard, his husband. He has been a prominent activist on environmental issues— especially opposition to mountaintop-removal coal mining— and LGBTQ rights.

In 2022, House received the Duggins Prize, the nation’s biggest award for an LGBTQ writer. His essays have appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Time, The New York Times and other publications. He has been a commentator for NPR’s All Things Considered and was the executive producer of the film Hillbilly, winner of the Los Angeles Film Festival’s documentary prize and the Foreign Press Association’s media award.

In 2023, House served as writer, co-producer and creative director of Tyler Childers’ music video “In Your Love,” earning a Grammy nomination. His 2018 novel Southernmost is currently in pre-production as a feature film. On his podcast, Writing Lessons With Silas House, he interviews Kentucky writers about various aspects of the craft.

House is a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers and the recipient of three honorary degrees. His awards include an E.B. White Award, the Storylines Prize from the New York Public Library/NAV Foundation, the Lee Smith Award and the Caritas and Hobson medals.

Barbara Kingsolver, a Hall of Fame writer from Carlisle (Nicholas County) whose novel Demon Copperhead won the 2023 Pulitzer

Prize for Fiction, calls House “an Appalachian treasure.”

“When I claim Silas as my friend, I feel like I’m joining a huge family, not just because he’s a dear and generous friend to so many people,” she said. “He’s also a friend to our mountains, our traditions, our music, literature, culture and history.”

House said he was in seventh grade when he decided to become a writer, but “I cannot remember a time when I didn’t love to read and tell stories. I was born that way, but I also grew up around people who just had an innate sense of telling a story and really understood the importance of storytelling.”

A beloved aunt, Dorothy “Dot” Kelsey, ran a community store. “I spent a lot of time in her store, and everybody who came in had a story,” he said. “I also grew up around a lot of really quiet social justice. I would see Dot give people food who needed it. My parents were always helping other people very quietly, never wanting any attention for it.

“Also, when I was a child, there

was a massive strip mine right across from our house,” he added. “I think early on that gave me a real sense of not only injustice, but also that nothing lasts.”

House said he also has been nourished by the community of Kentucky writers. When he was a young writer, famous authors such as Kingsolver, Wendell Berry, George Ella Lyon and Chris Offutt took his work seriously and encouraged him. He also feels a special kinship with two Spalding classmates who were inducted into the Hall of Fame last year: Crystal Wilkinson and Frank X Walker

“That has meant a lot to me, and I try to pass that on,” he said of the support he has received from other writers. “One way I’ve done that is through editing a series at the University Press of Kentucky” to help promising Kentucky and Appalachian writers get published.

“When somebody helps you, the way you can really repay them is to do it for somebody else,” he said. “I think most Kentucky writers are that way.”

Marcia Thornton Jones and Debbie Dadey were faculty members at a Lexington private school in the late 1980s when they began talking one day about children’s books: what they liked, what they didn’t like, and how they might like to write one someday.

“And then Marcia just said, ‘Well, why don’t we do it? Let’s start tomorrow,’ because that’s the way she is,” Dadey recalled.

While on lunch break the next day, they jotted down story ideas and made homework assignments for each other. Dadey was Sayre School’s librarian, and Jones was the computer lab teacher. Week after week, month after month, they collaborated on new stories, mailed them off to publishers—and got rejection slips.

“Our primary goal was to see our names on the cover of a book like the ones we liked to read to kids,” Jones said. “We came into this business not knowing a lot about it, and, to be honest, I think that was to our benefit, because we did not accept rejections as a ‘no.’ We thought rejections were just a statement that it wasn’t good enough yet.”

After nearly two years of this, a representative from Scholastic, one of the nation’s largest publishers for young people, called the Sayre School library one day. The company wanted one of their manuscripts.

The novel Vampires Don’t Wear Polka Dots was published in 1990. In the 35 years since then, Dadey and Jones have written and published about 100

books together, as well as dozens more books as solo writers. They estimate their books have sold about 46 million copies worldwide, making them among the most prolific and successful authors for young people.

In 2000, they even wrote a how-to book for adults—Story Sparkers: A Creativity Guide for Children’s Writers They updated it with a complete rewrite in 2019—Writing for Kids: The Ultimate Guide

Jones, 67, was born in Joliet, Illinois, and moved to Lexington when she was 5. She earned elementary education degrees from the University of Kentucky and Georgetown College.

Dadey, 66, was born in Morganfield (Union County) and grew up in Henderson (Henderson County). She earned degrees in elementary education and library science from Western Kentucky University.

Most of their jointly written books are part of what became the Bailey School Kids series. The stories are about the adventures of kids who attend the Bailey School and encounter teachers and other adults who may or may not be mythical beings, such as vampires, werewolves or dragons.

Dadey’s and Jones’ first published novel was the result of a bad day at school.

“I’d been a teacher for many years, and usually, the kids were great,” Jones said. “But I had a very bad day one day. Debbie came over to my classroom at lunch when we would write. She could tell I was upset and

asked what was wrong. I said, ‘It’s been a horrible day, worst day ever. I guess I would have to grow 10 feet tall, sprout horns and blow smoke out my nose just for them to realize I’m the teacher. I’m in charge. They have to do what I say!’ I mean, I was really upset.

“But Debbie started to laugh and said, ‘Well, what if a teacher could do that?’ And so we sat down and started writing Vampires Don’t Wear Polka Dots simply as a joke to make me feel better. We wrote about a teacher who was indeed a monster who could grow 10 feet tall, sprout horns and blow smoke out her nose. It took us two weeks. We had a blast writing it. And when we were finished with it, we thought, we’ve got a book.”

They had noticed how much kids like books with elements of fantasy and the supernatural. “Kids really like to read about monsters, and it’s both of our passions to reach kids who maybe didn’t like to read,” Dadey said. “As a librarian, I was always trying to find the right book for the right kid.”

That first book became a huge seller, so Jones and Dadey wrote more stories about the Bailey School Kids, developing their four main characters—Howie, Melody, Eddie and Liza—and recurring adult characters such as Mrs. Jeepers, Mr. Jenkins and Dr. Victor.

“We were actually writing side by side,” Jones said of their initial collaborations. “I think that helped us learn authentic dialogue because we were speaking it.”

Jones said publishers are reluctant to commit to a “series,” so additional

titles were at first branded as “companion” books.

Dadey’s husband, Dr. Eric Dadey, was a pharmaceutical scientist who taught at the University of Kentucky. When he got a job in Texas in 1992, Jones and Dadey thought their writing partnership wouldn’t survive the long distance. But about the same time, Scholastic asked them to rewrite the sixth Bailey School Kids manuscript they had submitted—and write four more to turn it into an official series.

“And so that’s when we learned about faxing,” Dadey said, referring to facsimile machines, which predated email for fast electronic document transmission. “So we’d work on an outline, then one of us would start the book. A lot of times I started them, and I would send it to Marcia. We would kind of be each other’s editors, and we would send it back and forth.”

“By the time a book would be finished, it had been through multiple revisions,” Jones said. “And each of us had mucked with every single chapter so that sometimes, we could not tell who wrote what chapter. It was a system that worked really well.”

More recent additions to the series include four graphic novels, which have become popular. The most recent is Dragons Don’t Cook Pizza. They also have another popular series of books called Ghostville Elementary.

Over the past couple of decades, Dadey has also developed children’s book series on her own: Mermaid Tales, Mini Mermaid Tales, Keyholders, Swamp Monster in Third Grade and others. She is especially proud of a picture

book published in 2023 called Never Give Up: Dr. Kati Karikó and the Race for the Future of Vaccines, illustrated by Juliana Oakley. For that project, Dadey interviewed Dr. Katalin Karikó, a Hungarian-American biochemist who laid the scientific groundwork for mRNA vaccines in time for the COVID-19 pandemic and won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2023.

Jones’ many solo books include the mid-grade novels Woodford the Brave and Ratfink and Champ, as well as the picture books The Tale of Jack Frost and Leprechaun on the Loose. She also has taught and mentored other authors.

“I’ve done some reflection over the last couple of years, especially this last year,” said Jones, whose husband, Stephen Jones, died in September 2024. “I realized I’m not really sure if I’m a writer or if that writing was just part of my teaching experience. I get energized through the teaching of things. My classroom has just gotten really big through my writing.”

Dadey and Jones said the secret to a

good children’s book is the same as any other book: compelling characters and a story the reader can relate to and feel part of. But there are differences.

“Children’s books need to be very tightly written,” Jones said. “Those characters have to be realistic, because our audience has a short attention span. I think writing for kids can be more difficult than writing for adults, because every word matters. Every character matters. Everything matters because the audience is just not going to suffer fools for very long.”

Writing for children is rewarding, they said, because it can literally change lives.

“Kids are learning their place in their world,” Jones said. “They’re learning what type of person they are, and how do they relate to the character, what characters might help them build their own character.

“We have to treat our audience with respect,” she added, “because children are smart, much smarter than we think.”

When Jeff Worley was an English major at Wichita State University in the late 1960s, he made a little money playing guitar and singing, mostly in bars around his Kansas hometown.

“I wasn’t ever a particularly good guitarist, and my singing was maybe acceptable,” he said. “But I never forgot the words to a song.”

His favorite songs were by Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Gordon Lightfoot—writers who could tell a story in poetry. But it wasn’t until Worley took a poetry class that he got up the courage to begin writing his own poems—and go on to earn a master of fine arts degree from Wichita State in 1975.

“I think what attracted me to poetry was the serious play with language,” he said. “And the possibilities of making something that other people would appreciate. I always wanted my poetry to be understandable and, at its best, memorable.”

Worley, 78, has produced 10 books of his poetry and published more than 500 poems in journals and magazines. His most recent book, The Poet Laureate of Aurora Avenue (Broadstone Books, 2022) includes some favorite poems from his previous books, plus new work. He edited the book What Comes Down to Us: 25 Contemporary Kentucky Poets (University Press of Kentucky, 2009). And he served as Kentucky’s poet laureate in 2019 and 2020.

“Jeff Worley is a poet’s poet,” said Richard Taylor, another former state poet laureate who was inducted into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame in 2023. “His work seems motivated not by the latest fad or fancy that editors want to publish but by what ordinary readers want to read. He decodes the confusing world with which we are confronted and renders it knowably, often humorously, lest we take ourselves too seriously.”

Worley moved to Lexington in 1986 when his late wife, Linda Kraus Worley, was hired by the University of Kentucky as a professor of German

studies and folklore/myth. They met while Worley was teaching English in Germany as part of the University of Maryland’s European division. She died in 2021.

After what he described as a lackluster stint as a freelance writer in Lexington, Worley became a writer for and later editor of Odyssey magazine, which the University of Kentucky published from 1982 until 2010 to highlight research and scholarship on campus.

In Lexington, Worley found the writing community he needed to develop and improve as a poet. He and Marcia Hurlow, a former English professor at Asbury University, formed a poetry group in 1989 that featured several notable Kentucky writers, including Taylor, Michael Moran and Devin Brown

Critical feedback from his wife and fellow poets was invaluable. “So were some of the rejection slips I got from magazines, with an editor pointing out that this and this don’t work very well,” Worley said. “I have a whole

drawer full of these rejection slips.”

For Worley, writing has always been a process of discovery.

“I kind of don’t know what I think about anything unless I write about it,” he said. “The more I write about something, the more I understand what it is I feel about it. And so, a lot of my poems are about my parents and about extended family.”

Worley started writing poems about animals two decades ago, after he and his wife bought a weekend cabin on Cave Run Lake.

“Animals really intrigue me,” he said. “It’s a total delight to sit in the morning with my coffee and my roll

on the screened-in back porch and just watch the deer come in. This time of year, they’ll be coming in with their babies. And to me, that’s about as delightful as anything can be.”

Other poems spring from things he overhears, and he advises students to always carry a pen and notecard to jot down gems. Such as when he overheard a little boy in the grocery produce section ask his father, “Dad, we have two legs and two eyes and two arms; why don’t we have two penises?”

“I reached in my back pocket for my notecard, and it wasn’t there,” Worley recalled. “I discovered that you can write on a banana. I wanted to get his words exactly, this kid. My failing is that I don’t know how the dad answered. This other little kid came by and stared at me a long time and went over and said something to her mother. I bet it had to do with, ‘There’s a crazy man over there

writing on a banana.’ ”

And, yes, a bit of that story ended up in a poem.

Humor is the secret weapon of Worley’s poetry, often inspired by his own misadventures or the absurdities of life. Humor is a rare commodity in modern poetry, and Worley thinks that is a shame.

“I think a lot of poets, like a lot of people, don’t have a very good sense of humor,” he said. “And there still are a lot of poets out there who believe in poetry as a serious calling and that there’s no room for levity.”

Worley has hundreds of books by other poets on his study shelves and reads widely. His favorites include Mary Oliver, Sharon Olds, William Stafford, Stephen Dunn and Michael Van Walleghen, his first poetry teacher at Wichita State.

In recent years, Worley has found himself writing fewer short poems and more long, narrative pieces. “I like to get into a subject that is really difficult to write about and see if I can do it without falling into various traps that a difficult poem lays out for you,” he said. “That’s a challenge, and I never get tired of it.”

Frederick Smock was a Kentucky poet laureate, a literary journal editor and a Bellarmine University professor whose straightforward poetry lyrically evoked the natural world.

“As soon as I met Fred Smock, then a graduate student at the University of Louisville, I knew I was in the company of a special and wonderful sensibility,” said Sena Jeter Naslund, a Hall of Fame novelist and former Kentucky poet laureate who was his teacher at UofL. “To have seen his journey as a distinguished poet, trailblazing editor and splendid teacher has been both comforting and inspiring.”

reading and talking about poems, and reminding listeners of the joy in sound, rhythm and rhyme that we have as children,” George Ella Lyon, another former Kentucky poet laureate and Hall of Fame member, said after Smock’s death at age 68 in 2022.

Bingham, the late writer and philanthropist, co-edited The American Voice, a literary journal. Smock later joined Bellarmine University, teaching English and creative writing. Smock’s 11 collections of poetry included Gardencourt (Larkspur Press, 1997), The Good Life (Larkspur Press, 2000), Guest House (Larkspur Press, 2003), The Blue Hour (Larkspur Press, 2010) and The Bounteous World (Broadstone Books, 2013). He also wrote two books of prose, two collections of essays and a memoir.

Naslund said the Louisville Review, a magazine she founded in 1976, and her Fleur-de-Lis Press now run a triennial contest in Smock’s memory. The Frederick Smock Poetry Prize is a first-book prize for Kentucky writers that includes book publication and a $1,000 award. The winner will be announced in March.

“As poet laureate, Fred’s intent was to bring poetry to as broad an audience as possible, and he did that by simply

Smock was born in Louisville on June 23, 1954. When he was 6, his physician father moved the family to suburban Fern Creek, where he often spent time wandering forests and fields. “I am drawn to nature,” he once said.

After graduating from Seneca High School, Smock earned a bachelor’s degree at Georgetown College and his Master of Arts at UofL. He did postgraduate study at the University of Arizona.

From 1985-98, Smock and Sallie

He published in many prominent literary journals, including The Southern Review, The Iowa Review, The Hudson Review, Poetry East, Ars Interpres (Sweden), The Georgetown Review and Olivier (Argentina).

Smock received the 2005 Wilson Wyatt Faculty Award at Bellarmine University, the Al Smith Fellowship in Poetry from the Kentucky Arts Council, and the Jim Wayne Miller Prize for Poetry from Western Kentucky University.

Smock died of heart-related issues on July 17, 2022. He is survived by two sons, Ben and Sam Smock

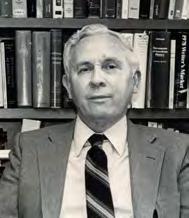

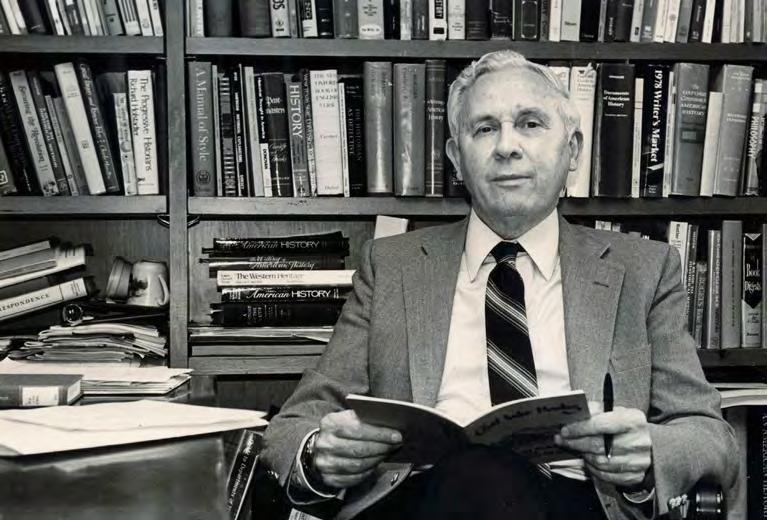

Lowell Harrison was an influential Kentucky historian who wrote or edited 15 books and taught history at Western Kentucky University for two decades.

Harrison’s books include The Civil War in Kentucky (1975), George Rogers Clark and the War in the West (1976), The Anti-Slavery Movement in Kentucky (1978), Kentucky’s Governors (1985), Western Kentucky University (1987), Kentucky’s Road to Statehood (1992) and Lincoln of Kentucky (2000).

He co-edited The Kentucky Encyclopedia in 1992 with fellow Kentucky historians Thomas D. Clark and James C. Klotter (both Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame inductees) and John E. Kleber. Also with Klotter, Harrison wrote A New History of Kentucky (1997). He published 115 articles in journals.

“As a writer and historian, Dr. Harrison published groundbreaking scholarship that reframed how we

think about Kentucky Civil War history, our state history, the Commonwealth’s governors and more,” said Stuart Sanders, director of research and publications at the Kentucky Historical Society. “Most important, his writing made the Bluegrass State’s past accessible to the public and demonstrated how our history influences Kentucky today.”

Harrison received several awards from WKU, including the Faculty Research Award in 1971, the Public Service Award in 1986, and inclusion in the Hall of Distinguished Alumni in 1999. He received the Thomas D. Clark Award for Excellence in Kentucky History from the Center for Kentucky History and Politics in 2001 and was awarded the Kentucky Historical Society Distinguished Service Award in 2010.

Harrison was involved with many historical associations, including the Kentucky and Filson historical societies and the Kentucky Oral

History Commission. He served on the University Press of Kentucky’s editorial board.

He was born Oct. 23, 1922, in Russell Springs (Russell County). He served in the Army during World War II as a combat engineer in Europe. He graduated from WKU in 1946 with a bachelor’s degree in history and earned his M.A. (1947) and Ph.D. (1951) at New York University. He attended the London School of Economics as a Fulbright Scholar.

From 1952-67, Harrison taught and was head of the history department at West Texas State University. In 1967, he returned to his alma mater in Bowling Green as a senior scholar and graduate adviser. He was twice elected to WKU’s Board of Regents.

Harrison retired from full-time teaching in 1988 but continued to teach part time until 1994. He died Oct. 22, 2011. Harrison’s wife of 63 years, Elaine “Penny” Harrison, died in 2016.

n conjunction with the annual Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame ceremony, the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning occasionally presents the Kentucky Literary Impact Award. This is awarded to someone who has had a major impact on helping Kentucky’s literary community. The previous two honorees were Gray Zeitz of Larkspur Press and the late Mike Mullins, director of Hindman Settlement School and the Appalachian Writers Workshop. This year, the third honoree is the late Pam Sexton.

Pamela Peyton Papka Sexton was a writer, poet, artist and community volunteer who helped create the Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning in Lexington and was a dynamic advocate for the arts and education in Kentucky.

She was born Jan. 13, 1946, in Thermopolis, Wyoming, to parents who valued education and volunteerism. After leaving Wyoming,

she lived in New Orleans and Puerto Rico before moving to Lexington in 1971. Sexton had a variety of jobs in banking, business writing, women’s health and the arts.

Sexton studied at the University of Kentucky and Spalding University, where she earned a master of fine arts degree in writing in 2003. She also studied sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Cambridge Arts Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sexton helped create the Carnegie Center in the historic Lexington Public Library building and later chaired its board of directors. “The Carnegie Center is a place where the light streams in, even on cloudy days,” she once wrote.

Her writing was widely published in Kentucky. She received a poetry award from the University of Kentucky’s Oswald Research & Creativity Competition and won the Leadingham Prize for Poetry from the Frankfort Arts Foundation. She was a founding member of KaBooM (the Kentucky Book Mafia), a writing group, and Mosaic, a group of women poets.

Sexton served on the boards of the Kentucky Folk Art Center in Morehead, Lexington Children’s Theatre, the Lexington Arts and Cultural Council (now LexArts) and the Lexington Philharmonic.

She was a founding member of the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence. Robert Sexton, her second husband, later became its director. Pam Sexton died in 2014 at the age of 68. She had three children: Ouita Michel of Midway, Perry Papka of Mount Sterling and Paige Walker of Lexington.

LIMERICK

Don Fleming

Camila Haney

Katie Hughbanks

Jon Pryor

POETRY

Bethany Broughton

Nancy K. Jentsch

Jay McCoy

Marianne Peel

Samantha Stotts

Cassie Whitt

Ashton Woodard

FICTION

Carla Carlton

Richard Day

Leanne Edelen

NONFICTION

Mary Casey-Sturk

Hayden Petty

kentucky monthly ’s annual writers’ showcase

I come from mountains, even the ones I’ve never stood on.

Somewhere in my blood there’s a memory of the Scottish Highlands stone ridges, cold wind, people shaped by weather, work, and a spine that doesn’t bend.

My ancestors crossed an ocean and found the Appalachian hills of Eastern Kentucky waiting for them like an echo. Fog curling the same way, ridges rising in familiar hymns, the land rolling out soft and fierce in a language they already knew.

Maybe that’s why Kentucky has always felt older than my own lifetime like the hills recognized me long before I understood them.

Here, we’re known for being stubborn, and we are.

We come from folks who hold their ground even when the world tries to move them. People who don’t back down from truth, who raise their voice when something matters, who carry faith like a lantern through the darkest hollers.

But we’re also the kind who help a neighbor first, even when our own cupboards sit thin. We give what we have a plate, a hand, a prayer because we know struggle, and we refuse to let someone else face it alone.

I grew up in a place where creeks carve their way through the hills with the patience of saints, and where winter settles like an old story everyone already knows.

Snow quiets the mountains, makes the world stand still long enough to remember.

In fall, the ridges burn red and orange, like the mountains setting themselves on fire just to remind us how beautiful endings can be. And spring spring turns everything green again, the color of forgiveness, the color of beginning, the color of a place that refuses to stay broken.

The hills teach us how To endure.

To bend without breaking. To grow back after every frost. To work for everything worth keeping.

Sometimes I think about my ancestors, how they must have stood here with the weight of a whole ocean behind them and felt something in their bones say, You know this land. You can build a life here.

And maybe that’s what it means to be from Eastern Kentucky: to be shaped by two sets of mountains the Highlands they carried in their memories, and the Appalachians that raised me.

To be tough where it counts, gentle where it matters, faithful even when the world shakes.

To stand my ground, love without holding back, and carry the kind of pride that doesn’t have to shout to be heard.

I am a Kentuckian because they saw home in these hills and now these hills live in me.

Ashton Woodard | Mount Sterling

In 1957, Kentucky had more bookmobiles than any other state in the country. But only one of them was haunted.

Marjorie Mae Crawford stood shivering in the parking lot of Little Flock Baptist Church. The early April breeze still carried the sharp edge of winter; it took spring a while to travel up the hollers in Sturgill. But Marjorie Mae hardly noticed the weather. She trembled with excitement as she strained for her first glimpse of the bookmobile.

Once a month, the sturdy white van growled its way up, down and around the hills of Southeastern Kentucky, its cargo area lined with shelves of books—everything from Dick and Jane reading primers to dog-eared copies of East of Eden. Marjorie Mae still couldn’t quite believe that the bookmobile lady allowed her to choose any book she liked and take it home for a whole month.

The town hadn’t had a library since the Roaring Paunch Creek, fed by days of unrelenting rain, had jumped its banks 20 years before, sweeping away the schoolhouse that had once stood on this very spot, along with 25 students and their teacher. The bodies of all but one had been found downstream in the desperate hours and days following. Rather than rebuild the school, the devastated community had instead erected the clapboard church.

Marjorie Mae read again the words engraved on the metal sign in front of the church: “In eternal remembrance of the little flock lost on April 3, 1937.

Jesus loves the little children.” Listed below were 26 names. She lingered on the first one, Daisy Lou Allen, the 10-year-old who had never been seen again.

Marjorie Mae, who had celebrated her 10th birthday the day before, shivered again, but her attention was quickly diverted by the sound of grinding gears: The bookmobile was here! Miss Birdwhistle turned off the engine, opened the back doors, and lowered the three folding steps.

First in line, as always, Marjorie Mae climbed inside and breathed in the lovely, dusty perfume of the pages.

“Hello again, Marjorie Mae,” Miss Birdwhistle said, taking an E.B. White book from her hand. “What did you think of ‘Charlotte’s Web’?”

“Oh, I loved it ever so much. But I wish Charlotte could have lived longer.”

“Well, that’s nature for you,” Miss Birdwhistle replied. “Everything has its time and season.”

“I suppose, but it still doesn’t seem fair,” Marjorie Mae said. “I think she had more living to do.”

She started toward the children’s chapter books as usual, but something stopped her. Without remembering exactly how, she found herself in front of a section of books she had never seen before: Kentucky Folklore. Her hand was drawn to a slim, ragged volume with threads trailing from the worn edges of its cover. “The Bell Witch, the Gray Lady, and Stories of Other Haunts

and Haints, by W.L. Montell,” she read softly to herself. She opened the back cover. The last date stamped on the checkout card inside the glued-on pocket was April 3, 1937.

This book hasn’t been checked out for 20 years, Marjorie Mae thought. But how can that be? The Bookmobile just started coming when I was 7.

Intrigued, she flipped through the pages until a story grabbed her. It was called “Trouble on Crawford Creek.”

She began to read.

The chalk squeaked as Charlie Johnson applied too much pressure on the blackboard. Ciphering was his worst subject, and darned if Miss Harris didn’t always call on him first. I could see his ears getting red, which was never a good sign.

But before he could turn around and confess to Miss Harris that he had no idea what to do next, we all heard another sound. The low rumbling built like the thunder that had shaken the town for days, but unlike the thunder, it didn’t ease. It sounded almost like a train, but the train hadn’t run in Sturgill since the Kingfisher Mine had closed the year before.

Whatever it was, it drew closer and closer, and louder and louder.

The wall of the schoolhouse buckled. I saw Charlie’s puzzled expression and Miss Harris’ horrified one and then all I saw was water, a wall of it, shoving aside desks and benches and the coat rack and the potbellied stove and the trees and the rocks and I couldn’t swim and I couldn’t float and I couldn’t breathe and …

“Marjorie Mae Crawford! Are you

going to check out that book or read the whole thing right here?” Miss Birdwhistle’s voice was warm with amusement and affection, but she did have other stops to make.

“What? Oh, my goodness, I got carried away,” Marjorie Mae said, shaking her head slightly. Her eyes, which had seemed slightly out of focus, fixed on Miss Birdwhistle’s. “Yes, I’d like to check this out, please.”

She laid the checkout card on Miss Birdwhistle’s tiny desk and carefully autographed it. The librarian had rolled the bands on her book stamp to display May 3, 1957, but she checked them again before pressing the stamp firmly into her ink pad and then onto the card.

“I’ll see you in a month,” she said to Marjorie Mae as she handed the book back to her.

“Yes, ma’am,” the girl replied. “I have more living to do.”

Miss Birdwhistle watched as she walked down the three steps and set off toward home. What an odd thing to say, she thought, picking up the checkout card. As she placed it in the box with the other cards, she noticed how yellowed it was. And the signature was smeared—highly unusual for that meticulous child. She looked closer at the autograph, then frowned with puzzlement.

Daisy Lou Allen.

Carla Carlton | Louisville

I had the inclination to write with my left hand as a child. But the teachers corrected me.

Told me it was wrong. So they made me write with my right. I learned my writing wasn’t the only thing left about me. I carried this questioning of my nature through my youth. And I’ve spent the rest of my life trying to be left again.

Because what They really told me was that I don’t have the right.

The right to— be like this.

to feel this way.

to act how I do.

I’ve spent my whole life unlearning the right way. For the glorious experience of getting to be wrong. I may not have the right according to Them. But that hasn’t stopped me yet.

Broughton | Barbourville

On the bar in front of me

Sits a glass of Woodford and Coke. It’s chilled with memories of you, But the taste burns with smoke.

The fire is out now; the flavor remains true.

I write three words in the ashes— Drinking of you.

Samantha Stotts | Nortonville (Hopkins County)

(Belle Brezing’s refined bawdy house, 59 Megowan Street, Lexington, Kentucky, 1894)

The parlor at Belle Brezing’s was warm and inviting that evening. Crimson velvet curtains shut out the autumn chill; lamps glowed on gilt-framed mirrors and mahogany Queen Anne tables. Perfume mingled with cigar smoke, softened by the rustle of silk and bursts of laughter. Belle herself presided in emerald satin, one hand on her crystal flute as she surveyed her well-schooled girls making easy conversation with the gentlemen.

At the center sat Gen. Basil W. Duke—famed Morgan’s Raider— genial, sharp-eyed, his mustache twitching with amusement. To his right lounged Col. Jack “Dirk Knife” Chinn, resplendent in ascot and patterned waistcoat, his laugh booming over every jest. Opposite them, Congressman Willie Breckinridge, florid and silverhaired, sipped a weak Old Crow, delighted to hold the floor, and holding an unlit cigar.

“General Duke,” Breckinridge declared, “you have discoursed on railroads, tariffs, and bourbon—each a Kentucky necessity. But what is your opinion on the suppression of dueling?

Surely you agree our legislature sought the higher plane.”

A ripple of mirth moved through the room. Sallie Fleming, whose popularity rivaled her décolletage, fluttered her fan. “Why, I like a man who fights for a

lady’s honor,” she said.

“Though it does depend on who wins.”

Laughter rose. Duke lifted his glass.

“My dear Congressman, the General Assembly has a peculiar genius—not for discouraging combat—but for tormenting politicians. To decree that a man convicted of dueling may hold no office and practice no law? Sir, you strike the Kentuckian at the heart of his pleasures. Denied office, he becomes a lawyer. Denied law, he seeks office. Denied both—he runs for Congress.”

The parlor erupted. Breckinridge bowed with a rueful smile.

From her corner Josie Roe, the sharp-tongued redhead, leaned forward. “Well said, General. But do you truly favor the duel? Seems a dreadful waste of handsome men.”

Duke bowed. “Madam, I favor no quarrel. But if one must occur, the duel is the least dishonest: two men, equally armed, equally imperiled. The coward finds no advantage; the bully, no refuge. Even a poor shot has a chance—more than he has in a street fight, where the other fellow begins by shooting him in the back.”

Chinn slapped his thigh. “True enough! More men in Frankfort fall to surprise than to honor at dawn. With pistols, a man knows when to stand tall.”

Belle raised her glass with an arch

smile. “And how many quarrels in this town were provoked by bourbon? If we banned whiskey instead of dueling, we might save lives—though it would ruin my business.”

“That,” Duke said with mock gravity, “would be tyranny of the blackest sort. Far better we banish the legislature than bourbon.”

Laughter rolled through the room. Sallie leaned toward Breckinridge and stage-whispered, “Wouldn’t it be easier if you politicians settled your rows with pistols at dawn? It might leave more offices for others.”

Breckinridge drew himself up. “Madam, if that were the case, there would be no one left to govern Kentucky.”

“Then we should be better governed,” Josie shot back, to general delight.

“How charming,” Chinn chuckled. Belle smiled, lifting her chin. “Charm, gentlemen, is a woman’s protection in a world built for men. We wear kindness like armor—and sharpen our smiles to a razor’s edge.”

Duke rose slightly, glass in hand. “To honor—whether on the field or in the parlor. In Kentucky, neither is ever without its combat.”

Glasses clinked. Laughter rose again. And Belle’s parlor glowed brighter for the Raider’s well-timed toast.

Richard Day | Lexington

Myrtle Watkins drove down the darkened two-lane highway in her 1995 Toyota Avalon.

The gnarled fingers on her right hand wrapped tightly around the steering wheel, while two of her left wrapped around a drug-store cigar. The knocking noise grew louder. Thankfully, she was headed to her son Randal’s service shop. She had called him after leaving the Piggly Wiggly. She inhaled the spicy smoke of the cigar. The cherry on its end blazed, lighting up the interior of the car far more than the faint dashboard lights. The knocking noise stopped. Her sturdy shoulders relaxed a little. Problems. She didn’t like these types of problems. But what was she to do since her Donald passed away? He was far from the best husband, taking to the drink a little more than most. But he kept the bills paid, and she could count on him when trouble called.

She rolled down her window, breathing in the fresh air with scents of pine and fallen leaves. The knocking started again. She shook her head. Randal had better fix this. He wasn’t the man his father was. He could handle problems but fluttered around a little too much in the career department. Partly because of her mothering. She coddled him, Donald used to say.

Myrtle saw it as helping Randal find his path to success and was willing to put her own back into making that happen. Probably took it too far, she thought. She’d delivered his papers when he overslept as a boy. When he was in his 20s, she battled bulls as a

rodeo clown for him when he went on fishing trips with his friends. Hell, when he was in his 30s, she let him use her as a teaching partner when he opened that Jiu-Jitsu studio so often, she eventually earned her black belt.

Blue strobe lights broke through the darkness.

“Damn.”

She pulled over. Her lips pulled tight. She butted out the cigar and gripped the steering wheel, her wrinkled knuckles whitening. The knocking noise stopped.

“Good evening, ma’am. Do you know why I stopped you tonight?” the officer asked.

Myrtle leaned into her age, slumping her shoulders for effect.

“Well,” she said quizzically, “I couldn’t have been speeding. I drive like a grandma. Was I going too slow?”

The police officer’s strong jaw relaxed and a smile spread between his cheeks.

“No ma’am. Your speed was fine. I pulled you over because one of your taillights isbroken.”

“Well, sadly, my car is in need of quite a few repairs. I’m on my way to my son’s shop right now. I’ll be sure to add the taillight to the list.” Myrtle turned her head a little to the side and smiled again.

“Where are you coming from?”

“I just went to get my groceries. That’s about the only time I come into the city anymore,” she replied.

“May I have your license and registration, please?”

Myrtle handed him the paperwork and her license.

“Hold tight. I’ll be right back,” he

said as he tipped the front of his wide-brimmed hat and returned to his car.

The knocking started again in a frantic cadence. Myrtle turned on the radio and tapped her foot for several minutes until the officer returned.

“Ma’am,” he said, handing her the license and registration back. “Everything is good. You’re free to go. Just gonna let you off with a warning. But also, I’d like to warn you about another matter. I heard on the radio that a robbery happened pretty near the grocery store. Just be careful driving to your son’s shop. Don’t pick up any strangers or stop anywhere. The suspect is still at large.”

“Oh, thank you. I’ll be very careful, officer.”

Myrtle watched the police car pull off before she reached into the console ashtray and retrieved her half-smoked cigar.

The knocking started back up.

Myrtle thought again about Randal. He had a bigger problem to solve than she originally thought. The cops knew about the misguided young man in the Piggly Wiggly parking lot. This definitely complicated things.

She inhaled her cigar.

That man made a very poor choice today. Not the robbery; Myrtle didn’t care about that.

But picking an old lady putting her groceries in her trunk to carjack— that was a mistake.

Myrtle put the car in drive. The knocking grew louder and much more frantic.

Leanne Edelen | Louisville

“Rain has buried her seed and her dead.” – James Still Shriveled seeds sleep in tombs but leap millennia when sown. Alive, they plead for rain, burst their eon-shells, outdoing what prophets promised.

So too, asleep, we barely inhale, shrouded by feathers and flannel, dead weight on our beds. But what lay dormant in mind’s core gathers rest’s rain, stretches, seeds scenes beyond foretelling.

Nancy K. Jentsch | Melbourne (Campbell County)

with a dear friend, I mention I’d rather keep talking than say, goodbye, so she offers, Did you know in Cherokee there is no word for goodbye?

We are connected—one by the Creator—and thus never leave one another. When we part, we say, when we meet again, always when, never if, & never goodbye.

It sounds so final farewell, so long like a severing, a parting, or losing a limb, rather than loosing the spirit to quest for beauty, for good, by and by,

until we can hold the same space. Even in the end, when we pass, the door opens to a new realm, a new beginning, something fresh. Even in death, saying goodbye

is too strong, too final, too much like the trickster trying to hide his stygian being under feathers colored by sky, by sea. Screeching, he does not sing; he calls, goodbye

Jay McCoy | Lexington

My father kept a flock of feral pigeons on the garage roof. Built the cages himself. Liked to watch the parent birds do their courtship dance, the male puffing up his neck feathers, bowing and pirouetting in front of the female. A ritual dance of trying to impress, emitting soft cooing notes to serenade his mate for life. My father believed in their affection for one another.

He would pick huckleberries off the mountainside, urging fruit, one by one, into hungry beaks. He’d steal worms from Uncle Joe’s coffee can, the one he kept next to the tackle box, and then coax the pigeons to devour them, bit by bit.

My father knew a platoon of pigeons carried messages across enemy lines at Normandy, delivering secrets to Allied forces. In a ceremony at Buckingham Palace, these birds received medals. Eternal gratitude for patriotism. My father paid respect to his pigeons, solemnly saluting his flock every night before he descended the rooftop aviary.

One night his own daddy hankered for some pigeon pie, knowing the breast muscles make for good-eating meat. My Nana used to serve pigeon pie at Thanksgiving, when they couldn’t afford a turkey. She’d cook the bird up with lard and onions and chicken livers, mushrooms if they could be found. Then stuff it all into Crisco pastry. She’d poke holes in the crust, letting it breathe while baking.

But my father wouldn’t hear of it. He’d named these birds, every one. They answered when he summoned them by name. So, that night, he ascended to the roof, unhinged the cages, and set those pigeons free. Neighbors, even those drunk on homemade moonshine, claimed they could hear wings flapping, even over church bells ringing.

Marianne Peel | Lexington

I’ve lied a few times. More than a handful. More than two handfuls. More than you could count on ten fingers and ten toes. Some were little and white, some big and black, and some were a rusty red, the words metallic tasting, coppery coins on my tongue. But some were delicious, sweet.

A few I even ate myself like cake.

Other lies weren’t born in words but in half-truths, which I told with my eyes and the places I put my hands when I shouldn’t have.

Still, I think I know the truth when I see it.

It’s in the dizzy feeling you get when you inhale too deeply and think you’ll never breathe again. But then you do.

Other times it comes out gently, like when the sunlight shines just so through the leaves of a tree, their dancing shadows confiding a grand universal in an unremarkable movement.

Maybe the truth is not something we tell or know but something we notice, if we look hard enough.

Maybe it is something we might even become.

Cassie Whitt | Winchester

The dog across the street is something like a Doberman— slick black hair, slim frame and pretty damn big. Until that night, her sheer size had been lost on me— she had refused to make friends. On a normal day, she barked at me from the safety of her front porch, as if scolding me for even looking her way, until that night when she was staring at me through the shadowy glass of the storm door. A succession of sound rapped like knuckles against the doorframe, as if she were shouting, “Let me in!” I hardly recognized Royal; her panting distorted her face into a half-grin, half-cringe-like expression—teeth exposed and tongue bouncing rapidly in time with the heaving of her chest.

I frowned at first, crept toward the door, and moved to unlatch its silver lock. My muttish hound dog failed to alert me that the beastly sized animal had approached. Any other evening, my dog would be coming out of her skin over the trespasser. I’d barely managed to crack open the door before a blur of black clung to my

side, desperately trying to squeeze past me. What the hell? I pushed her back, the storm door crashed shut behind me as I joined her in the darkness. I expected her to flee. Weirdly, her hips pushed into my thighs, clung to me instead. Panting, tail wagging, moving with me as I took another step. We were seemingly long-lost friends reunited. All right, maybe all those times I cooed at her from the side of the road really paid off. Except, that thought didn’t really make sense, did it? It’s against a paranoid’s nature. I brushed her fur back with the pads of my fingertips, feeling the sudden maternal urge to comfort her. I questioned her, a onesided interrogation, puzzle pieces taking shape. She didn’t really watch me as I repeated the motion—hardly looked at me, actually. No, her eyes were fixated elsewhere ... across the street. Humans are innately creatures of habit, set in their ways, comfortable in a routine. Rarely do they change—hardly ever is it coincidence when they do. Animals are hyper aware of danger. One piece

clicks together with the next.

Alarm bells frantically echoed in my head as more pieces started shifting together, one odd detail after another. The blinds were completely drawn; those are almost always open. Their front door was shut; they never close the door when Royal is outside. The porch lights were on; they’re usually off by now, the neighbors assumingly asleep inside. Packages sat on the edge of a step; those were delivered hours ago. She wouldn’t let me go back in without barking all over again; was she trying to tell me something?

One unfamiliar detail, maybe even two, would be reasonable on its own, but this many? Fissures formed amidst attempts to rationalize the sudden change in temperament, the bizarre breaks from routine, the stiffness in my chest that I couldn’t seem to shake. Every worst-case scenario took a breath of life. I felt myself gripping at Royal’s fur, as we stared together, synonymously. My neighbors were dead.

Hayden

Petty | Franklin

1956. The year my grandmother, also named Mary, came from Maidenhead, England, to Covington. Why, you might ask? There, it gets complicated. She had met and married someone from Kentucky during the chaos of World War II. About 18 months later, my mother came along. About six months before that, my grandfather had returned to the United States, leaving them behind for good.

Grandma didn’t let that deter her from building relationships with her new Kentucky relatives. She formed a bond with her former mother-in-law and her former sister-in-law.

Loving letters were sent, thoughtful gifts exchanged, and hope grew within my grandmother that maybe she’d have more opportunities here.

So, she came with daughter, mother and Pinky the cat in tow. A humble beginning with high hopes.

Mary Brenner Gibson had worked hard all her life. That continued in America. As the three generations of Brenner women settled in Covington, Mary found a job at the local newspaper. It was there that she bloomed and found her footing in a new land.

Not that it was easy. There were language barriers. Yes, really.

American slang and British slang (words I should not share here) are quite different, as are general terms for basic things such as toilets (loos) and lines (queues). Her desire for hot tea at meals in restaurants inevitably resulted in a tall glass of sweet tea being presented.

She caught on and embraced Kentucky. In fact, she loved it!

As time passed, she remarried, and more children came along. She became a den mother, a Girl Scout leader, a school volunteer and an avid camper. Grandma could name every bird, tree and shrub. Ask her anything, you got an accurate response.

Once, during the 1970s pet rock craze, she presented each child in my second-grade class with a pet rock, all lovingly painted by her. Unfortunately, some of the more rambunctious kids in the class decided that these made better projectiles than pets.

Undeterred, she continued to volunteer year after year—even after the principal banned all pet rocks and nearly banned my grandma.

She loved animals, too. Horses,

dogs, cats—you name it. Once, when she was in her 80s and living in Williamstown, I came down for a visit. I needed to use the bathroom, and when I opened the door, I was greeted by a hairy surprise—an alpaca! I shouted, “Why is there a llama in your bathroom?” and Grandma’s calm response was, “It’s an alpaca.” There was never an explanation beyond that. I didn’t ask, and she wasn’t telling.

Year after year, Grandma took the Girl Scouts to Campbell Mountain Girl Scout Camp, where I was always dazzled by her energy and ingenuity. Her annual treks to the Kentucky State Fair were infamous, as she tried to see how many of us could fit into one hotel room (for the record, it was 10), and there was nothing that excited her more than stopping to look at a waterfall. You can imagine her reaction at Cumberland Falls!

In case you wondered, yes, she loved Kentucky Fried Chicken. Eleven herbs and spices and one cup of hot tea, please!

Mary Casey-Sturk | Wilder

Three weeks with the man she adored, By then she learned how loud he snored. She’d pledged from the start, Till death do us part; So pawned her gold band for a sword.

Don Fleming | Crescent Springs

A man who was free and was lucky, Left town with his dog and his truck, he Drove somewhere urban, Discovered good bourbon, And decided he’d move to Kentucky.

Jon Pryor | Bowling Green

Mamaw’s fingers with needle and thread quilt a blanket to stretch across grandchild’s first bed stitched with love and care a silent blessing and prayer— not just a gift, a sacred heirloom instead.

Katie Hughbanks | Louisville

There was an old lady from Zemm they said who could cut, sew and hem. Often stitches too short. She ended up in court. Now she must go and make amend.

Camila Haney | Grayson

BY DEBORAH KOHL KREMER

Kentucky colleges and universities

bridge generations of students through traditions

Kentucky institutes of higher learning have deep-seated traditions that tie students and alumni to campus. Schools across the country boast epic fight songs and memorable hand gestures. Others are more extravagant, with campus bonfires or allowing students to jump in campus fountains one day per year. Here is a sampling of some of the rituals on campuses across the Bluegrass State.

A tradition for more than 60 years, Racer “sole” mates who meet on campus hang their shoes on the Shoe Tree, which is said to bring them a lifetime of good luck. Murray State’s shoe tree is believed to have started in the mid1960s. However, it didn’t quite catch on and become a tradition until decades later. It is a way for two people who met on campus to illustrate their love and devotion. Couples usually write their anniversaries on their shoes, and it is common for alumni to return to nail a baby shoe to the tree when they’ve started their family.

|| murraystate.edu

In Pippa Passes, the Christmas Pretties Program is one of Alice Lloyd College’s most cherished traditions, dating back to 1917, when Alice Lloyd and her mother, Ella Geddes, learned that few families on Caney Creek had ever celebrated Christmas. Determined to change that, they wrote to friends in Boston and across the Northeast, who sent dolls, toy trucks, mittens, candy, ornaments and other “pretties” that students carefully wrapped and delivered— sometimes on horseback—to families throughout the mountains. That spirit of service continues today as ALC students spend months preparing nearly 3,000 gifts to distribute at elementary schools, ensuring that the joy first shared on Caney Creek more than a century ago continues to reach new generations.

|| alc.edu

Berea College’s Mountain Day, which celebrated its 150th anniversary last October, is a time for students to celebrate nature and environment— specifically, exploring the Appalachian culture that is a key element of Berea College’s mission. The celebration of Mountain Day involves hiking up Indian Fort Mountain, located within the 9,000 acres of the college’s forest. Students are encouraged to hike up to the East Pinnacle before dawn to greet the sunrise atop the mountain.

Mountain Day activities include performances by many of the college’s dance, ensemble and choir groups.

|| berea.edu

Held each May, the Night of Lights marks the end of the academic year at Midway University. Students gather to say their farewells and light small candles to float down the stream by the Path of Opportunity on campus. Legend has it that if the candle stays aflame while passing beneath the bridge, one’s wish will come true.

|| midway.edu

One of Centre College’s most cherished traditions takes place just moments before commencement begins. As seniors proceed across the Danville campus, faculty and staff line the path in front of Crounse Hall, applauding the soonto-be graduates and honoring the hard work, dedication and perseverance that shaped their four years at Centre.

|| centre.edu

Frontier Nursing University, originally in Hyden and now in Versailles, has been home to the Circle-Up tradition for decades. At the end of each campus experience, students, faculty and staff join hands to form a circle. Each person in the circle is invited to reflect or share their thoughts, emotions or takeaway points from their experience. Circling up is based on an old Quaker tradition of taking a moment at the end of the day to share members’ thoughts with the community. As part of the FNU community, circling up continues virtually from home as a show of support when needed.

|| frontier.edu

Like clockwork, Campbellsville’s homecoming football game kicks off at 2:01 p.m. in honor of former head coach Ron Finley. The varsity coach from 1988-2002 established “Finley Time,” which involved starting a practice at 4:31 or a meeting at 8:01. His theory was that the players could remember the odd time better.

|| cambellsville.edu

Kentucky Christian University in Grayson has a longstanding tradition of hosting Grounds and Sounds, a monthly coffeehouse held in the McKenzie Student Life Center that features hot coffee and live music. Once each semester, the event is combined with Donald’s Pancake House, named after Donald Damron, vice president of student services, where pancakes and sausage are served hot off the grill—making it a favorite tradition among students and staff.

|| kcu.edu

Before exams at Richmond’s Eastern Kentucky University, students don’t just study, they give Daniel Boone’s toe a quick rub for a dose of good luck. The bronze statue of explorer Boone has been standing on EKU’s campus outside the iconic Keen Johnson Building for almost 60 years. His left foot shines more brightly, a result of the many rubs by students, alumni and visitors.

|| eku.edu

At the University of the Cumberlands in Williamsburg, a beloved statue of Abraham Lincoln has stood outside the Gatliff Administration Building since 2014. The statue stands with his hands cupped behind his back. On the way to exams, students drop a penny into Abe’s hands hoping he will bring them good luck.

|| ucumberlands.edu

For 21 years, Asbury University in Wilmore has hosted the Highbridge Film Festival. The festival showcases curated student films judged by industry professionals and celebrates the creativity that defines Asbury’s School of Communication Arts. Students run every aspect of the event, from promotion to production, making it both a celebration and a hands-on learning experience. Highbridge is one of Asbury’s most anticipated annual gatherings and a testament to the storytelling spirit woven into campus life. || asbury.edu.