CL ARIFIER

In all that we do, our commitment to quality is clear. From the experience of our skilled craftsmen to our command of the latest technologies, we stand apart from the competition. We take customer service very seriously, and work hard to prove it everyday.

water well services

•well cleaning and rehabilitation

•well drilling

•water treatment

•electrical and controls

•pump repair

•hydrogeological services

MICHIGAN RURAL

WATER ASSOCIATION

2127 University Park Drive, Suite 340 Okemos, MI 48864

P: 517-657-2601 www.mrwa.net

PRESIDENT

Todd Hackenberg, Village of Lawton

VICE PRESIDENT

Randy Seida, Lansing Charter Township

SECRETARY/ TREASURER

Michelle Thibideau, Village of Centreville

DIRECTORS

Tom Anthony, Village of Mattawan

Ron Bogart, City of Leslie

Darin Dood, Village of Lakeview

Andrea Schroeder, City of Davison

ASSOCIATE DIRECTORS

Bob Masters, Peerless-Midwest, Inc.

Dale Stewart, Northern Pump and Well Company

NATIONAL DIRECTOR

Chris Kenyon, City of lonia

MRWA A DMINISTRATIVE STAFF

Tim Neumann, Executive Director

Mike Engels, Director of Training/ Assistant Director

Melisa Lincoln, Membership & Marketing Director

Louanna Lawson, Finance Director

PUBLISHED FOR MRWA

P: 866.985.9780 info@kelman.ca www.kelmanonline.com

MANAGING EDITOR Lauren Drew

DESIGN/ LAYOUT Tabitha Robin

MARKETING MANAGER Al Whalen

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR Sabrina Simmonds

PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE CHAIR

Todd Hackenberg, Village of Lawton

125 S Main Street

Lawton, MI 49065

Phone: 269-624-6406

Phone: 269-624-6401

hackenbergt@lawtonmi.gov

VICE PRESIDENT

Randy Seida, Lansing Charter Township

3209 W Michigan Avenue

Lansing, MI 48917

Phone: 517-485-5476

Phone: 517-819-8720 seidar@westsidewater.com

SECRETARY/TREASURER

Michelle Thibideau

Village of Centreville 221 Main Street Centreville, MI 49032

Phone: 269-467-6409

Phone: 269-506-6800

mthibideaucentreville@gmail.com

DIRECTOR

Tom Anthony, Village of Mattawan

24221 Front Avenue

Mattawan, MI 49071

Phone: 269-668-2300

Phone: 269-217-4921 tom@mattawanmi.com

DIRECTOR

Ron Bogart, City of Leslie 602 W Bellevue Street PO Box 496

Leslie, MI 49251

Phone: 517-589-8236

Phone: 517-257-3094 manager@cityofleslie.org

DIRECTOR

Darin Dood

Village of Lakeview PO Box 30

Lakeview, MI 48850

Phone: 989-352-6322

Phone: 989-289-3110 manager@villageoflakeview.org

DIRECTOR

Andrea Schroeder, City of Davison

200 E Flint Street, Suite 2

Davison, MI 48423

Phone: 810-653-2191

Phone: 810-845-1682

aschroeder@cityofdavison.org

NATIONAL DIRECTOR

Chris Kenyon, City of Ionia DPU 720 Wells Street Ionia, MI 48846

Phone: 616-523-0165

Phone: 616-813-1263

ckenyon@ci.ionia.mi.us

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

Bob Masters, Peerless-Midwest, Inc.

505 Apple Tree Drive Ionia, MI 48846

Phone: 616-527-0050

Phone: 616-690-8139

bob.masters@peerlessmidwest.com

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

Dale Stewart, Northern Pump & Well 6837 W Grand River Avenue

Lansing, MI 48906

Phone: 517-322-0219

Phone: 517-242-8949

dstewart@northernpumppwco.com

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Tim Neumann

Michigan Rural Water Association 2127 University Park Drive, Suite 340 Okemos MI 48864

Phone: 616-401-5436

tneumann@mrwa.net

You need equipment that works and works within the rules. Sulzer’s XFP submersible sewage pumps deliver clog-resistant performance and long-term reliability, all while meeting full Build America, Buy America (BABA) compliance.

That means peace of mind for your operations and access to funding your project relies on, without compromising performance.

We don’t just meet standards. We help you move forward with confidence.

Built here. Built to last. Built for you.

Learn more about Sulzer’s BABA go.sulzer.com/trusted-baba

Todd Hackenberg, President, Michigan Rural Water Association

Across Michigan, small and rural water systems serve as the lifeline of their communities – providing safe, reliable drinking water while facing the growing challenges of aging infrastructure, regulatory compliance, and limited staffing.

Yet despite these hurdles, Michigan’s rural water operators continue to demonstrate remarkable resilience and professionalism.

The Michigan Rural Water Association (MRWA) plays a critical role in that success. Through hands-on technical assistance, operator training, source water protection initiatives, and emergency response coordination, MRWA strengthens the capacity of local systems and builds partnerships that

protect public health. Whether it’s helping a community map its water lines, navigate lead service line inventory requirements, or secure funding for infrastructure upgrades, MRWA stands ready to assist every step of the way.

As we look ahead, collaboration remains key. By sharing knowledge, resources, and success stories, Michigan’s water professionals ensure that even the smallest systems can thrive in an era of increasing complexity. Together, we safeguard not only our water, but the future of our rural communities. So please support the MRWA and NRWA and when you talk to your senators and congress let them know the important role MRWA plays to help small water systems.

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Tim Neumann

Phone: 616-401-5436 tneumann@mrwa.net

MRWA OFFICE

2127 University Park Drive, Suite 340, Okemos, MI 48864

Phone: 517-657-2601 | www.mrwa.net

DIRECTOR OF TRAINING/ ASSISTANT DIRECTOR

Mike Engles Phone: 231-878-3285 mengles@mrwa.net

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Louanna Lawson Phone: 517-657-2601 finance@mrwa.net

MEMBERSHIP/MARKETING DIRECTOR

Melisa Lincoln Phone: 517-657-2601 membersvcs@mrwa.net

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Cheri Laverty Phone: 517-657-2601 training@mrwa.net

COMMUNITY WATER AND WASTEWATER SPECIALIST

Kyle Bond Phone: 989-745-4405 kbond@mrwa.net

WATER CIRCUIT RIDER

John Monsees Phone: 989-529-1342 jmonsees@mrwa.net

WATER CIRCUIT RIDER

Jonathan Edwards Phone: 231-429-3289 jedwards@mrwa.net

WATER QUALITY ACTION SPECIALIST

John Holland Phone: 989-506-0439

jholland@mrwa.net

EPA TRAINING SPECIALIST

Joe VanDommelen Phone: 517-525-4553 jvandomnmnelen@mrwa.net

SOURCE WATER PROTECTION SPECIALIST

Kelly Hon Phone: 989-621-2361 khon@mrwa.net

WASTEWATER TECHNICIAN

Matt Lumbert Phone: 269-908-3792 mlumbert@mrwa.net

WASTEWATER TECHNICIAN

Amanda White Phone: 616-633-4070

awhite@mrwa.net

ENERGY EFFICIENCY TECHNICIAN

Ginger Van Conet Phone: 517-444-1321

ggrant@mrwa.net

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Tim Neumann, Executive Director, Michigan Rural Water Association

Hope everyone’s doing well as we head into the last stretch of 2025! I wanted to share an update on one of our programs that’s been on pause since August 31, 2024.

We used to have an EPA Wastewater (WW) program made up of four parts –supporting tribal systems, decentralized systems, lagoons, and providing compliance assistance. Even though funding had been set aside, we’ve been without the program since 2024 while the EPA worked through the award process.

The good news is that in September we officially got word of a new start date for the EPA-WW program, and the start date was backdated to September 1. This new round is a two-year program with three main areas of focus:

• Decentralized Wastewater Systems

• Acquisition of Finance and Funding

• Water Quality and Compliance

We’re really looking forward to getting this program going again and continuing to help communities through these efforts.

The Decentralized Wastewater System Program will offer assistance and guidance to rural and small communities, as well as decentralized wastewater systems, that are most in need of support.

Wastewater treatment challenges are a community-wide issue – they’re longterm, complex, and often expensive to address. WQAS plays a key role by providing technical assistance (TA) to help guide community decision-makers, stakeholders, and homeowners through these oftenunfamiliar processes.

One of the main reasons communities –especially rural and Tribal ones – struggle to access funding is the lack of technical assistance to help them navigate steps like engineering, project design and planning, evaluating potential solutions, and identifying funding sources.

Decentralized wastewater systems also face their own set of challenges, including limited funding, poor soils, shallow bedrock, high water tables, small land parcels, aging or undersized

septic systems, and surfacing sewage issues. On top of that, many homeowners simply aren’t fully aware of how to properly operate and maintain their septic systems.

The Acquisition of Finance and Funding Program will help municipalities plan, develop, and secure financing through the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) and EPA’s Clean Water Indian Set-Aside Grant (CWISA). The program will build economic impact, facilitate locally driven solutions, addresses weather related challenges, deliver accelerated results, and builds local capacity and sustainability with a goal of increasing grant funding to rural, small, and Tribal communities and wastewater systems that have struggled to secure funding. Classroom sessions and follow-up technical assistance will also be provided. Funding Specialists will provide training classes with approved Continuing Education Units (CEUs) to promote operator licensure and improve workforce development – key components of WWS sustainability. The objective of this program is to provide onsite, face-to-face T/TA to operators, managers, and decision-makers of small WWSs to help achieve access to funding sources.

The last program for assistance is the Training and Technical Assistance for Small

and Rural Wastewater Systems is a training and technical assistance program to rural, small, and tribal publicly owned treatment works, decentralized systems (including lagoons), and municipalities in improving water quality and achieving and maintaining compliance.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) Compliance Assistance Program is designed to strengthen the technical capacity in small wastewater systems, ultimately resulting in the reduction of the number of WWSs out of compliance with health-based standards.

Rural and small wastewater treatment systems are defined as systems that treat up to 1 million gallons per day (MGD) of wastewater or serve a population of less than 10,000 persons and may also serve operations such as, but not limited to, hospitals, schools, and restaurants. Most wastewater systems in the nation serve populations less than 10,000.

We are excited to have these EPA-WW programs back to provide assistance to communities throughout Michigan. If you need assistance with one of these three programs please reach out to John Holland our Water Quality Action Specialist as he will be moving back into this program and can be reached at jholland@mrwa.net or 989-506-0439.

By Jonathan Edwards, Water Circuit Rider, Michigan Rural Water Association

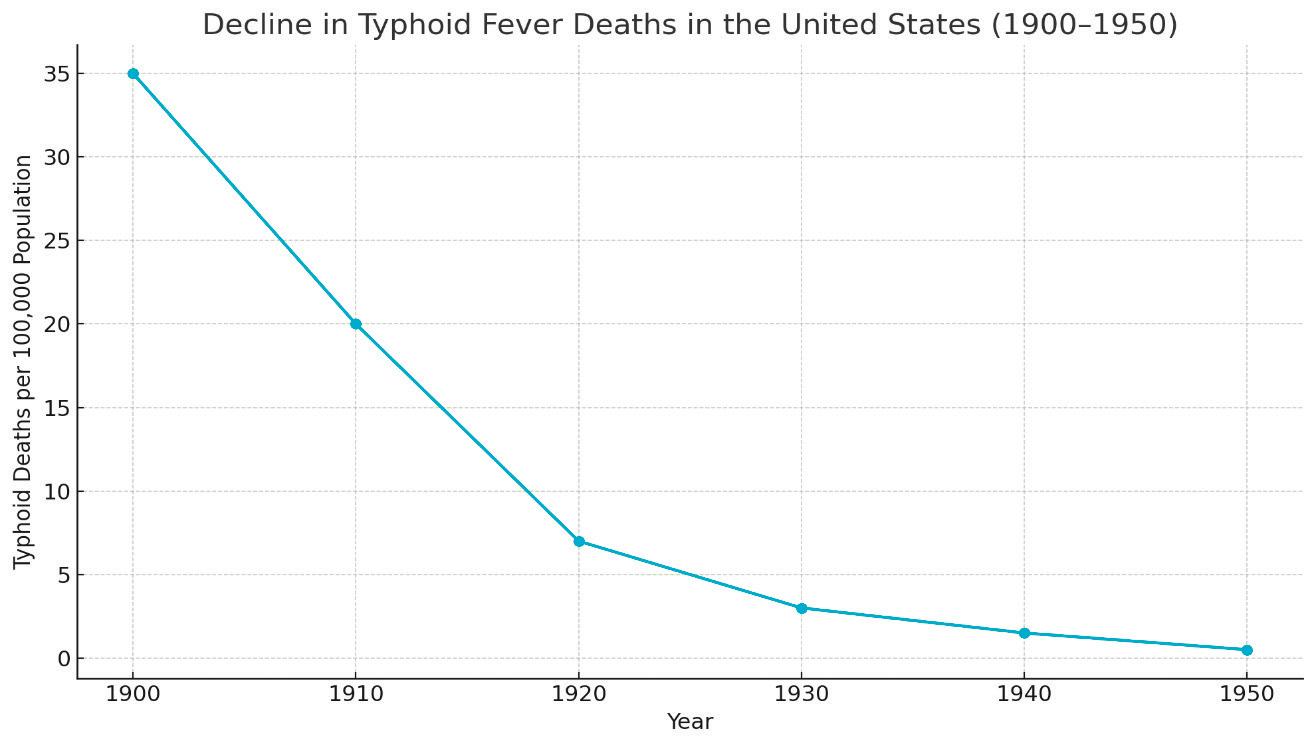

hen we think about major public health breakthroughs, it’s easy to picture vaccines, antibiotics, or surgery. But one of the quietest and most powerful advances came from something as simple as disinfecting drinking water. Chlorine changed the game. By adding it to water supplies, communities were able to stop deadly outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and other waterborne diseases. This article looks back at how chlorine came into use, why it was such a big deal, and how it continues to shape water treatment today.

Before the discovery of germ theory, water was primarily judged by its appearance, smell, or taste. Ancient methods, such as settling and sand filtration, made water clearer but didn’t significantly reduce the risk of disease. By the 1800s, rapid industrial growth and crowded cities made waterborne diseases a constant threat. Cholera and typhoid outbreaks were common and deadly.

Things began to change in 1854 when Dr. John Snow linked a cholera outbreak in London to a contaminated well. His work is often seen as the foundation of modern public health.

The first large-scale use of chlorine in the U.S. happened in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1908. Sanitary engineer John L. Leal and George W. Fuller designed a system that added calcium hypochlorite to the city’s drinking water. The results were almost immediate: typhoid cases dropped sharply.

Even though people were nervous at first –some worried chlorine might be harmful – it quickly proved its value. Within a few decades, chlorination became the standard practice across much of the country (McGuire, 2013).

Chlorine disinfects by creating hypochlorous acid (HOCl) in water, which is a strong oxidant that destroys bacteria, viruses, and other microbes.

A few reasons it caught on so widely:

• It leaves a residual: A small amount stays in the pipes, protecting against recontamination.

• It’s affordable: Easy to produce, transport, and store.

• It’s flexible: Works for both big city systems and small rural ones.

The difference chlorine made is hard to overstate. Typhoid fever deaths in the U.S. dropped by more than 90% between 1900 and 1940 (CDC, 1999; Cutler & Miller, 2005). Clean water played a huge role in longer life expectancy, safer cities, and healthier communities.

The CDC has even listed drinking water disinfection as one of the ten greatest public health achievements of the 20th century.

Today, chlorine is still the most common disinfectant. But we’ve learned it can also react with organic matter to form disinfection byproducts (DBPs), some of which can be

harmful at high levels. Because of this, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created strict rules, like the Stage 1 and Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rules (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], 2025).

Water systems now use tools like online monitoring, automatic chemical feeds, and distribution modeling to balance safety and compliance. Some utilities also use

chloramines or other methods alongside chlorine to keep DBPs under control.

Chlorine turned drinking water into one of the safest things we have today. What started in Jersey City back in 1908 is still protecting communities all over the United States and World today. Even with today’s new challenges – aging pipes, climate

impacts, emerging pathogens – the need for reliable disinfection hasn’t changed. Chlorine remains a foundation of safe water, and water professionals continue to build on that foundation to keep people healthy.

American Water Works Association. (2005). Water chlorination and chloramination (2nd ed.). AWWA Manual of Water Supply Practices M20.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Control of infectious diseases. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48(29), 621–629. https://www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4829a1.htm

Cutler, D., & Miller, G. (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The 20th century United States. Demography, 42(1), 1–22. https://doi. org/10.1353/dem.2005.0002.

McGuire, M. J. (2013). The chlorine revolution: Water disinfection and the fight to save lives. American Water Works Association. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025). Disinfectants and disinfection byproducts rules https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/ stage-1-and-stage-2-disinfectants-anddisinfection-byproducts-rules.

THE MODERN UTILITY'S APPROACH CENTERS ON UNIDIRECTIONAL FLUSHING (UDF) AS THE MOST EFFECTIVE STRATEGY.

By Joe VanDommelen, EPA Training Specialist, Michigan Rural Water Association

To the public, fire hydrant flushing might look like a simple, wasteful act. To a water professional, it is a crucial, non-chemical method of preventative maintenance that directly impacts regulatory compliance, infrastructure longevity, and customer satisfaction. The modern utility’s approach centers on Unidirectional Flushing (UDF) as the most effective strategy.

UDF: THE PREFERRED TECHNIQUE FOR OPTIMAL SCOURING

Conventional flushing – simply opening hydrants to release water – often lacks the velocity needed to fully clean pipes. UDF, however, is a systematic engineering process that isolates segments of the distribution system to achieve maximum effectiveness:

• Velocity is Key: By strategically closing valves and opening a single hydrant,

flow is restricted to a specific section. This engineered constraint achieves high Reynolds numbers (which is a measure of how turbulent the water is) and a water velocity of 2.5 feet per second (ft/s) or greater, which is necessary to create the scouring action that dislodges material adhering to the pipe walls. The higher the velocity the better the water will clean the pipes.

• Targeted Removal of Deposits: This turbulent flow effectively clears accumulated sediment, tubercles, and biofilm which are the primary sources of aesthetic water quality issues (e.g., color, turbidity, taste, and odor).

• Compliance and Disinfectant Residual: UDF ensures that areas of the system prone to low flow are flushed with fresh, treated water. This is vital for maintaining an adequate disinfectant residual (e.g., free chlorine) to the furthest points of the network, supporting compliance with the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) regulations.

Beyond water quality, UDF is an integral component of a robust asset management program:

• Valve and Hydrant Exercising: The flushing process inherently requires the operation (exercising) of key system components. This regular use prevents valves and hydrants from seizing up, ensuring they remain fully operational in an emergency.

• Critical Fire Flow Data: During the flush, operators collect essential data, including static pressure, residual pressure, and

flow rates. This data is critical for the fire department’s pre-planning and confirms the system’s ability to meet Insurance Services Office (ISO) requirements for fire protection.

• Identifying Infrastructure Issues: Abnormal pressures, unusually persistent high turbidity, or slow clearing times can indicate underlying issues such as partially closed or broken valves, cross-connections, or failing pipe segments, allowing for timely repairs.

To execute a successful UDF program, water operators must adhere to strict protocols:

1. Systematic Mapping and Sequencing: UDF requires accurate mapping of the pipe network and a detailed sequence of valve closures to ensure water flows from the cleanest source to the dirtiest outlet.

2. Monitoring and Documentation:

Continuously monitor the discharged water for turbidity until it runs clear. Document all operational changes, flow data, and water quality results for regulatory reporting.

3. Customer Notification and Mitigation: Provide ample advance warning to residents and businesses about potential temporary discoloration or pressure drops. Advise customers not to use hot water or perform laundry during the flushing window to prevent drawing sediment into their home plumbing. In summary, hydrant flushing is not merely the release of water; it is a meticulously planned, data-driven activity that is foundational to maintaining the hydraulic and chemical integrity of the distribution system, thereby ensuring safe, clean water delivery and reliable fire suppression capabilities.

DURING THE FLUSH, OPERATORS COLLECT ESSENTIAL DATA, INCLUDING STATIC PRESSURE, RESIDUAL PRESSURE, AND FLOW RATES. THIS DATA IS CRITICAL FOR THE FIRE DEPARTMENT'S PRE-PLANNING AND CONFIRMS THE SYSTEM'S ABILITY TO MEET INSURANCE SERVICES OFFICE (ISO) REQUIREMENTS FOR FIRE PROTECTION.

By Kyle Bond, Community Water & Wastewater Specialist, Michigan Rural Water Association

n Michigan, the safety of our drinking water depends on more than just treatment and distribution – it also depends on prevention.

One of the most overlooked threats to water quality is the crossconnection, a physical link between a potable and non-potable water source that can allow contaminants to flow backward into the system. A single backflow event can jeopardize not only an individual customer’s water but potentially an entire community supply.

That’s why Michigan’s Safe Drinking Water Act rules, known as Part 14 – Cross-Connections, require every Type 1 public water supply to establish and maintain a comprehensive cross-connection control program. These rules, administered by the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), work hand-in-hand with the Michigan Plumbing Code to ensure that our drinking water systems remain protected from contamination. But while the rules are clear, building a strong local program takes thoughtful planning, sound ordinance language, and consistent inspection practices.

A good cross-connection program starts with a solid written plan. Michigan Rule R 325.11404 requires every community water supply to have an EGLE-approved program that outlines exactly how inspections, testing, and enforcement will be carried out. The written plan becomes the backbone of your prevention efforts – it’s where you define who administers the program, how often inspections occur, and how you’ll ensure compliance across residential, commercial, industrial, and institutional customers.

Each plan should begin with a clear statement of authority, identifying who will conduct inspections and enforce corrections. It should also include a hazard-based customer inventory, which

prioritizes facilities by their potential risk to the water supply. Industrial and commercial customers usually pose the highest hazards, followed by institutional and governmental users, with residential irrigation systems making up a large share of lower-risk connections.

Your plan should also spell out which backflow prevention assemblies are approved for use, referencing ASSE or CSA standards. Since 2018, all testable devices in Michigan must be tested by individuals holding ASSE 5110 certification – a key requirement that ensures testing is done by qualified professionals.

Testing schedules must meet or exceed the state’s minimum requirements: all testable devices should be checked at installation, after repair, and at least once every three years. Lawn irrigation systems without chemical injection are the only exception – they may be tested every five years if your EGLE-approved plan allows it. The plan should also include public education components, such as customer notices or outreach materials explaining why testing is important and how customers can comply. And don’t forget about reporting – EGLE requires each public water supplier to submit an annual program report summarizing inspections, testing, and corrective actions.

STRENGTHENING THE PROGRAM THROUGH LOCAL ORDINANCES Even the best-written plan needs legal authority behind it. That’s where a strong ordinance comes in. Michigan communities are encouraged to adopt EGLE’s Part 14 Rules (R 325.11401–R 325.11407) by reference within their local ordinances. This step not only aligns your local authority with state law but also gives your utility the power to access properties, require compliance, and enforce corrections.

An effective ordinance should clearly authorize inspection access to any property served by the public water supply, define testing

requirements, establish correction timelines, and outline enforcement tools such as service disconnection for noncompliance. It should specify that backflow prevention devices must meet ASSE or CSA standards, be installed per the Michigan Plumbing Code, and be tested by ASSE 5110-certified testers at the required intervals.

Many communities also use their ordinance to address recordkeeping and report submission requirements, ensuring that all test results are properly documented and available for EGLE review. For properties with secondary water sources – like private wells or process water systems – the ordinance should require either clear color-coding of piping or the installation of a backflow preventer at the service connection if tracing is not practical.

Strong enforcement language not only protects the water system but also helps utilities manage the program consistently and fairly. When customers understand that cross-connection control is a matter of public health – not just paperwork – they’re more likely to cooperate.

Once the plan and ordinance are in place, the real work begins in the field. Inspections and testing are the lifeblood of any cross-connection program. EGLE expects utilities to perform initial inspections and periodic reinspections of all customers served by the public supply. How often these inspections occur depends on the hazard level, but every connection should eventually be reviewed on a regular cycle.

A well-run inspection program starts with clear communication. Send customers advance notices explaining the purpose of the inspection and what to expect. During the inspection, document all findings carefully –recording device types, serial numbers, installation details, and the degree of hazard. If violations are found, issue a written notice specifying what needs to be corrected and the time allowed to make the fix.

All testing must be performed by ASSE 5110-certified testers, and results should be submitted promptly to the utility. The utility, in turn, should maintain detailed records for every connection inspected and every test performed. These records form the basis for the annual EGLE report and serve as documentation in case of future compliance reviews.

The most successful programs don’t treat cross-connection control as a one-time effort but as a continuing cycle of prevention, inspection, education, and correction.

Many Michigan utilities share similar hurdles when running their programs. One of the most common is confusion about testing frequency. Some customers assume annual testing is required, while the state’s minimum standard is every three years (or five for non-chemical irrigation systems). Aligning your plan, ordinance, and communication materials with EGLE’s rules helps avoid mixed messages.

Another issue involves the use of the wrong backflow device for the level of hazard. For example, a double-check valve may not be sufficient for a high-hazard industrial process that requires a reduced pressure zone (RPZ) assembly. Referencing the Michigan Plumbing Code and EGLE’s Cross-Connection Rules Manual in your plan helps ensure that each connection is properly protected.

Finally, access and enforcement can be challenges – especially when customers are hesitant to allow inspections. The best way to prevent disputes is to ensure that your ordinance clearly grants right of entry for inspection and defines the consequences of noncompliance.

At its core, a cross-connection program is about protecting the integrity of our drinking water systems. It’s not just a regulatory

checkbox – it’s a proactive safeguard against contamination events that could harm public health and erode community trust. By developing a comprehensive written plan, enacting a strong ordinance, and committing to consistent inspections and testing, Michigan’s water systems can ensure that clean, safe drinking water remains one of our state’s most valuable resources. In the end, prevention always costs less than correction – and a strong crossconnection program is one of the best investments a community can make in its future.

• Prevention pays off. Investing time in inspections, education, and proper documentation will always cost less than dealing with a contamination event or enforcement action later.

• Consistency is key. The most successful programs maintain a predictable schedule for inspections, testing, and reporting –building both compliance and trust.

• Local authority matters. A strong ordinance gives your utility the legal power to enforce corrections, gain access for inspections, and protect the water system effectively.

• Qualified testing protects everyone. Ensuring all tests are performed by ASSE 5110-certified testers maintains credibility and consistency across the state.

• Communication builds cooperation. Customers are far more willing to comply when they understand that cross-connection control is about protecting their own health, not just following regulations.

• Keep learning. EGLE’s Cross-Connection Rules Manual and MRWA training resources provide excellent guidance for refining your program and staying ahead of evolving standards.

From our humble beginnings in Jackson over 20 years ago to nine locations spanning the entire state of Michigan, Michigan Pipe & Valve is dedicated to supplying residential, commercial and municipal clients alike with top quality products and customer service. Find the location nearest you and reach out to us so that we can help you fulfill your needs, large or small .

Gaylord

375 Chestnut St, Gaylord, MI 49734 (989) 889-6682

Genessee 1217 E. Stanley Rd. Mt. Morris, MI 48458 (810) 547-7154

Grand Rapids 5500 36th St SE Grand Rapids, MI 49512 (616) 805-3206

Holland 518 E.16th Holland, MI 49423 (616) 376-8636

Jackson 3604 Page Ave Jackson, MI 49203 (517) 764-9151

Kalamazoo 3308 Covington Rd Suite C Kalamazoo, MI 49001

Mt. Pleasant 1314 S. Mission Road Mt. Pleasant, MI 48858 (989) 817-4331

Saginaw 596 Kochville Rd. Saginaw, MI 48604 (989) 752-7911

Traverse City 487 West Welch Court Traverse City, MI 49686 (231) 929-7473

DUCTILE IRON PIPE

VALVES, HYDRANTS

WATER METERING

HDPE PIPE, PVC PIPE AND FIITINGS

TOOLS AND MUCH MORE

OF THE MICHIGAN RURAL WATER ASSOCIATION’S 28TH ANNUAL UPPER PENINSULA CONFERENCE AND EXPO

October 15-16, 2025 | Ramada in Marquette, MI

LUNCH SPONSOR

COFFEE SPONSOR

BREAKFAST SPONSOR

SOCIAL HOUR SPONSORS

BINGO CARD

THE CITY OF PORTLAND, MI, located in Ionia County, was incorporated as a village in 1869 and as a city in 1969. Portland has a population of approximately 4,000 and owns and maintains a storm sewer system, sanitary sewer system, wastewater treatment plant (WWTP), and water system. The first WWTP was constructed in 1958, with upgrades in 1971 and 2012.

SUMMARY:

Customer: City of Portland, MI

Project:

Wastewater System Improvements

Equipment:

•Flygt Concertor pumps

• DeZurik valves

•Waterman hydraulic gates

• Kaeser high efficiency screw blowers

• Parkson influent auger screen

• Watson Marlow chemical feed system

• Sanitaire diffused aeration system

• AquaPoint MBBR system

Result: Modernization of the WWTP with advanced treatment technologies, ensuring reliable, high-quality effluent.

The WWTP is rated to treat an average daily flow of 0.5 million gallons per day (MGD), with a maximum daily flow of 1.5 MGD. Prior to the 2023 improvements, the plant consisted of influent screening, aerated grit removal, traditional activated sludge treatment, chemical phosphorus removal, secondary clarification, ultraviolet disinfection, and solids treatment and handling. Much of the equipment was installed in 1971, with some upgrades in 2012. An engineering study identified plant inefficiencies, primarily due to aging infrastructure and limited biological treatment capacity.

(continued on the next page)

Kennedy Industries collaborated with the City and its consulting engineering firm to define a clear scope of supply aimed at improving the treatment process and replacing outdated equipment through a State Revolving Fund (SRF) project. F&V Construction served as the construction management team, while Midwest Power Systems was awarded the mechanical construction contract and partnered with Kennedy Industries to supply equipment and coordinate commissioning and training.

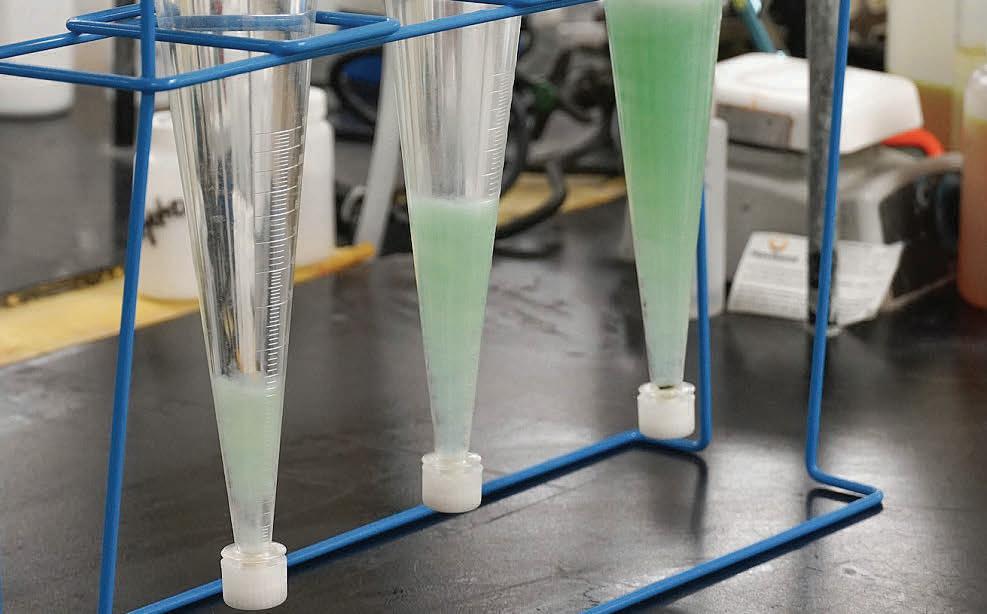

Kennedy Industries supplied the following equipment for the project:

• Flygt Concertor horizontally installed dry-pit centrifugal pumps

• DeZurik valves

• Waterman hydraulic gates

• Kaeser high-efficiency screw blowers

• Parkson influent auger screen

• Watson Marlow chemical feed system

• Sanitaire diffused aeration system

• AquaPoint moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) system

By utilizing the MBBR biological treatment system, the City was able to repurpose the existing aeration basins while increasing biological treatment capacity— without adding new tankage.

The City of Portland’s Wastewater Treatment Plant has been nearly fully modernized, incorporating current treatment technologies that provide high-quality effluent discharged to the Grand River. With this upgraded system, the plant can rely on long-term, efficient, and reliable water treatment operations.

By Kelly S. Hon, MRWA USDA-FSA Source Water Protection Specialist

Globally, as populations rise, extreme weather patterns soar and pollution to our waterways increase, it likely comes as no surprise that the international water crisis has been and will continue to be upon us. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), one in four children worldwide will be living in areas with extreme water stress by 2040. Equally as alarming is the statistic that currently, 2.2 billion people do not have access to clean water while 3.5 billion people are forced to manage daily without hygienic sanitation (United Nations World Water Development Report 2024). Although the United States (U.S.) has not experienced devastation to this extent, water shortages are upon us. National Geographic reports that within fifty years, many regions of the U.S. could see their freshwater supply reduced by as much as a third. In fact, with as many as 96 out of 204 basins in trouble, water shortages would impact most of the U.S., including the central and southern Great Plains, the Southwest, the central Rocky Mountain states as well as parts of California, the South and the Midwest. Today, in fact, forty out of fifty states are experiencing water shortages.

As significant players in the water and wastewater industry, it is important that we understand where our water is going, determine what steps we can take to be better water stewards and put our words into action through effective source water protection implementation measures. Although abundantly rich in water, Michigan is trying to lead such efforts. Great leaders will take the proactive route, creating or controlling a situation before something happens rather than waiting until something has happened to scramble and identify the solution.

According to the Associated Press, in 2007, the U.S. government predicted that “at least 36 states would face water shortage issues by 2013 because of a combination of rising temperatures, drought, population growth, urban sprawl, waste and excess” (The Associated Press, 2007). Their predictions were accurate and there are several alarming examples throughout the U.S. The Ogallala Aquifer, the largest aquifer in North America, spans eight states from Texas north to South Dakota and from eastern Nebraska to Wyoming. The agricultural economy of the Ogallala region “generates more than $20 billion (USD) each year, constitutes about 27% of all irrigated land area and makes up 95% of all groundwater withdrawals.

level of about 15 feet, when averaged over the entire Ogallala area (Oklahoma State University 2024).

Similarly, the California Department of Water Resources 2023 State Water Project Delivery Capability Report indicates that if the current patterns continue in California, delivery, capability and reliability could be reduced by as much as 23 percent in 20 years. Relatively speaking, a 23 percent decline would be equivalent to about 496,000 acres-feet per year, enough to supply 1,736,000 homes for a year (California Department of Water Resources 2024). More alarming statistics have surfaced from other states as well. Las Vegas, one of the fastest growing cities in the U.S., has had its population more than double from 259,834 in 1990 to 660,929 in 2020.

ALTHOUGH THE UNITED STATES (U.S.) HAS NOT EXPERIENCED DEVASTATION TO THIS EXTENT, WATER SHORTAGES ARE UPON US. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC REPORTS THAT WITHIN FIFTY YEARS, MANY REGIONS OF THE U.S. COULD SEE THEIR FRESHWATER SUPPLY REDUCED BY AS MUCH AS A THIRD.

Moreover, the Ogallala region is responsible for 10% of the total farm crop value of the U.S.” (Science Direct 2023). In addition to supporting and contributing significantly to local economies and agricultural industries, the Ogallala Aquifer also provides drinking water to approximately 82% of the people living within the Ogallala boundaries In 2007, the Ogallala Aquifer had been pumped at a rate 14 times greater than it could be replenished (Lohan, 2007). The most recent United States Geological Survey (USGS) publication estimates a drop in the water

Along with several other communities, approximately 90% of the City of Las Vegas’s water is supplied by the Colorado River. In August of 2021, the Colorado River captured the attention of the nation when the federal government declared a water shortage on the river. This comes as no surprise as water challenges have increasingly become more concerning.

In November of 2024, the Bureau of Reclamation released four alternatives to divide water from the river to stakeholders and states in the Colorado River Basin.

Avenues such as this will continue to push the topic from “conversation” to “action” and in a more tangible, meaningful way. States within the Ogallala Region and Colorado Basin, along with New Mexico, California, Arizona and Nevada are not alone as other states, face their own challenges concerning water quality, quantity and withdrawal.

Michigan, with its rich abundance of water, is surrounded by the Great Lakes. The Great Lakes boast 6 quadrillion gallons of fresh water, which is one-fifth of the world’s fresh water supply. Spread evenly over the entire U.S., the Great Lakes would submerge the country under approximately 9.5 feet of water. In addition, not only is Lake Superior the biggest of the Great Lakes, but it also has the largest surface area of any freshwater lake in the world. It contains almost 3,000 cubic miles of water, an amount that could fill all the other Great Lakes, plus three additional Lake Eries (Great Lakes Information Network, 2010). About 60% of the State’s population, and approximately 67 public water supply systems (PWSSs) utilize surface water from either the Great Lakes or inland surface water bodies in Michigan.

Groundwater statistics within Michigan are almost as impressive. According to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE), Michigan has approximately 1,400 community water supplies, 10,000 noncommunity water supplies and 1.12 million households served by private wells, with approximately 15,000 domestic wells drilled each year (EGLE 2024). With such abundance, comes a level of great responsibility and stewardship for Michiganders.

Michigan, and seven other Great Lakes States including Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the premiers of the Canadian Provinces of Ontario and Quebec realized the value and exception of this resource and its management almost forty years ago. On February 11, 1985, the governors of these states signed the Great Lakes Charter, which resolved to protect the water resources of the Great Lakes by establishing state programs to manage water withdrawal. Until 2006, however, Michigan remained the only state that had failed to honor its promise.

Committed to the implementation of water resource management, former Governor Jennifer Granholm began pressing the issue in 2004. At the same time, several

highly publicized controversial issues surfaced. A proposed bottled water operation in northern Michigan, conflicts between small and large quantity water users, and the release of a report by a legislatively created advisory council further stressed the need for action. In February 2006, these laws, which are outlined below, amended Part 327, Great Lakes Preservation, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (MDEQ, No Date Given).

Essentially, Part 327 prohibits new or increased large quantity water withdrawals that cause an adverse resource impact (ARI). To determine an ARI, the Groundwater Conservation Advisory Council worked with some of the state’s leading aquatic ecologists to develop a water withdrawal assessment tool (WWAT). This online tool allows users to enter information which quickly determines if their withdrawal will have a negative impact on the environment. It also compares the amount of groundwater contributing to stream flow to the size of the stream’s watershed. Removing too much water from the stream can cause a change in the flow depth, velocity and temperature of the stream (MDEQ, No Date Given). These factors impact which fish populations dwell within each water body. If a proposed withdrawal is found to cause an ARI, the request is denied.

If it is determined that the withdrawal does not have an ARI, registration is required along with information on the withdrawal amount, location, proposed and consumptive use. Each year thereafter, the user must report the withdrawal volume and pay a reporting fee which helps offset the cost of the WWAT. In addition, new or increased large quantity water withdrawal users must

obtain a permit if the withdrawal is from an inland lake or stream of greater than two million gallons per day (gpd) (unless it is a seasonal withdrawal that averages no more than two million gpd averaged over a consecutive 90–day period) or if the withdrawal is greater than five million gpd and from one of the Great Lakes. If the withdrawal is from one of the Great Lakes, all water withdrawn, less consumptive use, must be returned to the Lake’s watershed (MDEQ, No Date Given).

Several activities which were once regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act were also affected by the water withdrawal legislation. First, a community water supply is exempt from the permitting requirement. If the withdrawal is over two million gpd from an inland source or five million gpd from a Great Lake, the ARI applies. Because PWSS withdrawal is necessary and if there are no alternative locations, the state may grant the request even if there is an ARI. Second, withdrawal for agricultural purposes is also exempt. Agricultural users must report on their withdrawal to the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD).

A permit is also required for a bottled water operation that uses a new or increased large quantity withdrawal of more than 250,000 gpd. This permit will only be granted if the withdrawal does not cause an ARI, the use is reasonable under traditional Michigan water law and riparian rights are protected. The bottled water company must implement activities that address the hydrologic impact of the withdrawal.

Other provisions within the law encourage the creation of voluntary water user committees and the development of water conservation guidelines by water users.

In 2025, EGLE announced the update of the WWAT. This work occurred in large part to allow for increased transparency of tools and data, software updates, accessibility and user interface improvements and State of Michigan security requirements.

In addition to the water use legislation, Granholm also signed the Great Lakes Compact on July 9, 2008 (MDEQ, 2009). Among other things, the Compact joins Michigan and the other Great Lakes States and Canadian Provinces in a commitment to use responsible and science-based management of the region’s water resources (MDEQ, 2009).

While putting together the legislation, some environmental groups pushed to change public and private water rights. These groups could not convince the legislature as the final law indicated that “it shall not be construed to affect common law water rights or property rights; the applicability of other environmental laws; or limit any rights or interest of the State as sovereign” (Great Lakes Law, 2008). Despite the disappointment of these groups, many were pleased that requirements were enacted. A necessary step in the right direction was made in the protection of Michigan’s most valuable resource.

MICHIGAN

In addition to the development of legislation on water withdrawal and in response to the 1986 amendments to the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, Michigan also developed a state-specific Source Water Protection Program (SWPP). Voluntary and locally implemented, Michigan’s SWPP provides a means for water resource management at the local level. Seven SWPP elements are required and outlined in Figure 1.

Information on each of the seven elements is compiled into a SWPP Plan, submitted to EGLE and approved. Once approved, the next step involves implementation. Turning the goals and objectives outlined within the SWPP Plan into action items that are checked off the list as they are implemented is the key to success. EGLE also provides source water protection grant funding through an annual application process if communities are interested in financial assistance.

To most, source water protection is not a new concept. In fact, there are SWPPs throughout the U.S., all of which vary in scope and detail.

Some are required while others are voluntary, states may have fewer elements while others may have more, and all will

MICHIGAN SWPP

IDENTIFY THE SOURCE WATER PROTECTION AREA

ESTABLISH A SWPP TEAM

DEVELOP A CONTAMINANT SOURCE INVENTORY

IMPLEMENT LAND USE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

CREATE AN EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN

PLAN FOR NEW WATER WELLS/INTAKES

ORGANIZE A PUBLIC EDUCATION PROGRAM

face different challenges, circumstances and areas of focus. If implemented, however, each local SWPP can determine which key environmental issues to focus on that will aid in the management, protection and preservation of their local water source. Several of the more common key environmental issues that impact source

water protection are identified in Figure 2. Now, imagine if the almost 1,400 PWSSs in Michigan (of which supply seven million Michiganders with drinking water) all actively implemented local SWPPs. And on an even larger scale, imagine if all PWSSs throughout the U.S., or the almost 282 million people (87% of the total population) actively

implemented local SWPPs (USGS 2015). In addition to understanding more about key environmental issues, we would have a higher level of public understanding on topics such as why we have water bills, why dumping the oil on the ground could end up percolating down into the ground and into the coffee cup, where to drop off local pharmaceuticals instead of flushing them down the toilet, why it is important not to dump contaminants on the ground or down storm drains and where the dirty water goes if septic systems are not pumped and maintained. Understanding these and other issues would be a game changer for source water protection practices and if implemented in all communities would be a step in the right direction.

As we celebrate the almost forty-year mark of source water protection, one of the largest challenges that we face is the lack of knowledge and understanding surrounding SWPP implementation. For many systems, if source water protection is not a mandatory requirement, it is pushed aside to focus on the required mandates. For other systems, SWPP Plans are developed to appease the state primacy agencies with little thought on final outcomes, the possibility of resulting success and exemplary efforts in drinking water protection achievements. Changing this mindset along with assistance on implementation and outreach are a must. Community leaders may not have the time to create outreach materials, and many may not know how or where to start.

TURNING THE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES OUTLINED WITHIN THE SWPP PLAN INTO ACTION ITEMS THAT ARE CHECKED OFF THE LIST AS THEY ARE IMPLEMENTED IS THE KEY TO SUCCESS.

Forming partnerships with local rural water associations can alleviate the burden. Areas of focus should be tailored to individual communities, and their circumstances and programs should be ongoing.

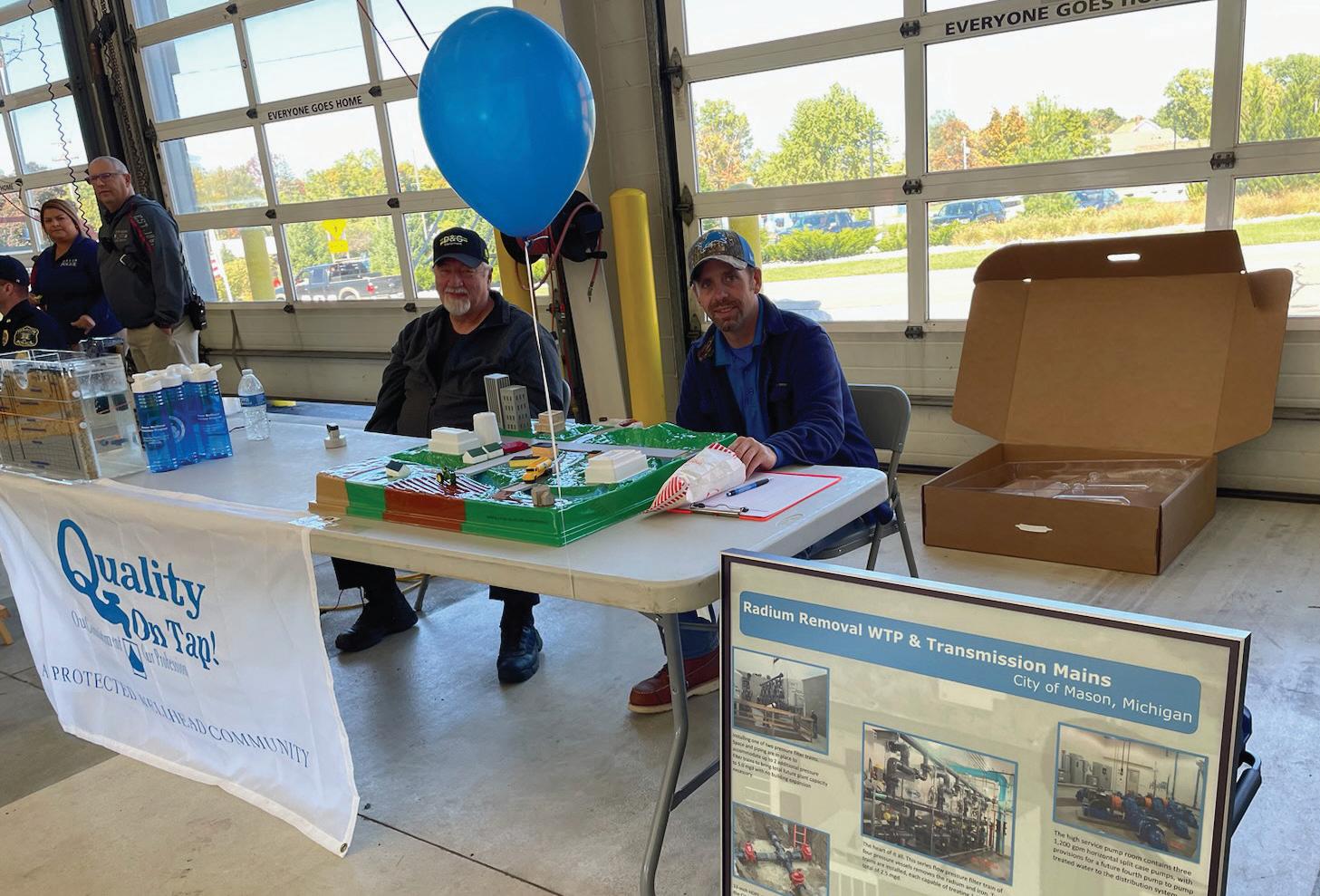

Michigan EGLE works closely with the Michigan Rural Water Association (MRWA) Source Water Protection Specialist to host SWPP training, conferences and webinars throughout the state. MRWA assists communities with the development and implementation of local SWPPs. Local dedication and commitment are paying off as communities throughout Michigan enact long term, active SWPPs. Several communities have received state and national awards for exemplary efforts in environmental protection.

As a nation and as we work together to address water quality and quantity, future challenges, such as climate change and population growth, will further intensify the water dilemma. Water legislation, alternative options in metering, rationing, conservation, source water protection and other policy driven action items are all steps in the right direction. In addition, locally driven water resource management strategies, tailored to each community’s needs and specific situations, will be important factors. After all, water quality and quantity issues vary significantly from one state to another. Michigan, for example, clearly has different challenges than its southern and western allies. What works for one may not provide the most effective solution for the next. Collectively, however, we need to work together through partnerships, collaboration and training. Let us learn from the minimal water resource management mistakes of the past and implement measures that will work to ensure the protection of our most valuable and precious resource for current and future generations.

For more information about developing, updating or implementing a SWPP in your community or state, contact Kelly Hon, MRWA USDA-FSA Source Water Protection Specialist at khon@mrwa.net.

Associated Press. Crisis Feared As U.S. Water Supplies Dry Up, October 27, 2007. 2011 http://www.msnbc.com/id/21494919/ns/ us_news-environment.

California Department of Water Resources. New Report Estimates Potential Water Losses Due to Climate Crises, Actions to Boost Supplies. July 31, 2024. 2024 https://water. ca.gov/News/News-Releases/2024/Jul-24/ New-Report-Estimates-Potential- WaterLosses-Due-to-Climate-Crisis-Actions-toBoost-Supplies.

Great Lakes Information Network. Great Lakes Facts and Figures, Janaury 2010. 2011 http:// www.great-lakes.net/lakes/ref/lakefact.html. Hall, Noah. Michigan’s Innovative New Water Withdrawal Law, July 24, 2008. 2011 http:// www.greatlakeslaw.org/blog/2008/07/ michigans-innovative-new-waterwithdrawal-law.html.

Hutchinson, Alex. “Las Vegas Tries to Prevent a Water Shortage.” Popular Mechanics. October, 2009. 2011 http://www.popularmechanics. com/science/environment/4210244.

Lohan, Tara. “Our Drinkable Water Supply Is Vanishing.” October 2007. 2011 http://www. countercurrents.org/lohan111007.htm.

Michigan Department of Environment Great Lakes and Energy. Drinking Water. No Date Given. 2024 https://www.michigan.gov/egle/ about/organization/Drinking-Water- andEnvironmental-Health/drinking-water.

Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Groundwater Statistics. July 2003. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Michigan Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool. July 9, 2009.

Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. New Water Use and Water Withdrawal Legislation. April 16, 2007. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. New Water Withdrawal Law for Michigan. No Date Given. 2011 http://www. michigan.gov/documents/deq/deq-wdwithdrawallaw-summary_260216_7.pdf.

National Sea Grant Law Center. Michigan Passes Water Withdrawal Legislation. April 2006.

Oklahoma State University. “The Ogallala Aquifer.” March 2017. 2024 https:// extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/theogallala-aquifer.html.

Science Direct. The Declining Ogallala Aquifer and the Future Role of Rangeland Science on the North American High Plains. March 2023. 2024 https://www. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S155074242200118X#:~:text=The%20 Ogallala%20Aquifer%20region,%20 located%20in%20the.

USGS. The quality of our Nation’s waters: Quality of water from public-supply wells in the United States, 1993-2007: Overview of Major Findings. July 1019. 2024 https:// pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1346/.

Critical infrastructure, including adequate water service, is a basic requirement for a healthy economy, encourages employment opportunities and makes a community a desired place to live and work. The nearly 45,000 water systems in rural America are anchor institutions in their communities.

In many rural communities water infrastructure is past its useful life. Without adequate water and sanitation services, businesses move out of our rural communities, forcing the next generation to leave to find better opportunities. Those left behind are robbed of hope for a prosperous future.

Rural America’s economy is driven by entrepreneurship, and made of a diverse range of operations through over 700,000 businesses. Rural areas produce most of the food we consume, provide lumber and other forest products used to build our homes and furniture, and supply the energy we consume daily.

Rural economies are deeply connected to their urban counterparts

USDA RD WEP not only provides essential services to the families that live in rural America, but also all business activities. These include small businesses, farming, manufacturing, emergency services, and more. In rural America, nearly 85% of all business establishments are small. These small businesses are critical to local economies, employing 54% of workers in their communities. Rural communities need access to funding through USDA RD WEP to thrive.

WEP is instrumental in helping rural America maintain affordable water access for all rural people, and it is imperative that Rural Water’s voice and priorities are heard within the Halls of Congress and within our nation’s leadership. Through our combined thousands of rural leaders from every state, we can ensure Congress and the Trump Administration know that WEP is the trusted partner for rural America and must be maintained.

USDA RURAL DEVELOPMENT WATER & ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAMS (WEP)

In 2023, USDA RD WEP funded over $1.7 billion in projects to small and rural communities.

The average median household income for communities that received WEP funding was $37,029, half of the national average household income of $74,580.

In 2023, 308 WEP projects addressed health and sanitary challenges and 28,326 new connections provided drinking water to residents for the first time, resulting in over 400,000 individuals and households benefiting from this funding.

TELL CONGRESS NOW KEEP RURAL AMERICA STRONG!

Scan the QR Code to learn more about how you can help keep Rural America Strong!

RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Without the grant from USDA RD, we would be exactly where we were. And that’s where we were 30 years ago. The customers aren’t able to pay higher rates easily. This system hadn’t been updated in so long and this was a lifesaver for it. For small rural villages to update their water systems and have good, reliable drinking water for all their citizens, the only way possible is through USDA RD funding.

- Mike Hamilton, Kaleva Water System Operator

The Village of Kaleva faces challenges common to many small towns, particularly regarding its water system.

VILLAGE OF KALEVA, MI POPULATION | 400 BUSINESSES I 30

With just over 30 local businesses, ranging from museums, grocery stores, restaurants, barber shops and salons, to automotive and industry, water is vital for the livelihood of all citizens in the village.

In recent years, Kaleva has confronted issues stemming from aging infrastructure, water quality anxieties, and financial constraints. Kaleva pursued a comprehensive approach to address its water challenges. This strategy encompassed infrastructure upgrades, refinement of water treatment procedures, and the implementation of protective measures for water sources.

Kaleva’s endeavors were supported by $3.6 million in funding from USDA RD. System upgrades include the replacement of 2,950 feet of 8-inch asbestos-cement pipeline, along with 1,100 feet of 4-inch and 350 feet of 2-inch pipeline. Additionally, the village has installed 1,300 feet of new 8-inch pipeline, expanding its distribution network. Kaleva has secured its water supply by drilling two artesian wells. The project installed 300 new meters, replaced two old hydrants, and installed five new ones, bolstering emergency response efforts.

Rural Development will continue to play a vital role in modernizing, preserving, and protecting rural America’s infrastructure and public health. You can help secure its future today by signing the pledge and writing to your Congressional representatives today.

Providing adequate support and resources necessary to protect and enhance the environment, public health, sustainability of utilities, and economic vitality of rural America with clean, affordable, and safe water service is a primary responsibility for our federal elected officials.

Visit www.ruralwaterstrong.org to learn more.

Kyle Bond, Community Water & Wastewater Specialist

Nestled in northern Michigan’s Missaukee County, the City of McBain is a vibrant small community with a strong sense of identity and forward-looking infrastructure investments. While McBain retains its charming small-town character – with local businesses, schools, and community gatherings – it’s also making significant strides in upgrading its municipal services.

The Need for Change

Historically, the city’s water system included older wells and a storage tank that posed quality, capacity, and reliability challenges. For example, more than half of the storage tank’s volume was unusable, limiting usable capacity and system pressure. Additionally, the system’s cast-iron mains, dating to the 1950s, increased

the risk of discoloration, sediment buildup, and reduced fire-flow capability.

McBain has undertaken a comprehensive multi-million-dollar improvement plan that includes the following:

• A nearly $7 million water-system improvement project with a new municipal well, enhancements to existing wells, and replacement of approximately 12,000 feet of water main.

• Construction of a new elevated water storage tank – planned for about 200,000 gallons capacity – to reduce detention time, improve water quality and boost system pressures.

• Replacement of aging wells and installation of iron-treatment systems to improve water quality.

McBain’s installation of a new water tower, signaling a commitment to long-term resilience and service reliability. Standing approximately 130 feet tall, this upgrade underscores the city’s strategic approach to investing in infrastructure that benefits residents and future generations.

• Improved water quality: Reduced sediment and iron burdens lead to clearer, better-tasting water.

• Enhanced fire-flow capacity: Larger mains and a modern storage tank strengthen system performance during emergencies.

• Future-proofing: The new infrastructure positions McBain for continued growth.

• Community confidence: Visible investments like the new tower foster civic pride and attract business investment.

The commissioning of the new tower will significantly enhance pressure and reliability for the community. This major

MCBAIN’S INSTALLATION OF A NEW WATER TOWER, SIGNALING A COMMITMENT TO LONG-TERM RESILIENCE AND SERVICE RELIABILITY.

upgrade is expected to make a noticeable difference in the daily lives of residents, providing a more consistent and efficient water supply. To ensure a smooth transition and keep everyone informed, a key focus will be on maintaining transparent communication with residents throughout the project. This will include regular updates on project timelines, progress, and improvements, so that the residents can plan ahead and stay informed about what to expect. By keeping the community well-informed, the goal is to minimize disruptions and ensure that residents are aware of the benefits and enhancements that the new tower will bring, ultimately resulting in a better quality of life for all.

McBain’s story is one of proactive investment and strategic infrastructure renewal. By upgrading its water system – down to a brand-new storage tower – the city is reinforcing its foundation as a resilient, forward-looking small community. For residents, this means reliable, high-quality water today and sustainable service tomorrow.

Letters regarding the assistance you have received from MRWA are useful in discussing with our lawmakers the need for water programs for small communities. If you have received assistance from MRWA that has been helpful, please consider writing a letter of thanks and sending it to us.

November 7, 2025

Michigan Rural Water Association

CITY OF MARINE CITY OFFICE OF CITY MANAGER 260 SOUTH PARKER STREET

MARINE CITY, MI 48039

PHONE: (810) 765-0513 FAX: (810) 765-4010

Mr. Timothy Neumann – Executive Director – tneumann@mrwa.net

Mr. Christopher Kenyon – Senior Vice President – cdkenyon45@gmail.com

2127 University Park Drive, Suite #340

Okemos, Ml 48864

Re: Recognition of MWRA Staff Members

Mathew S. Lumbert – Wastewater Technician/Joe VanDommelen – Water Technician

Dear Sirs,

Over the six to seven months' time, the city of Marine City and its staff members have had the opportunity to utilize the services of the Michigan Rural Water Association and its staff here in Marine City, Ml. Marine City has a history of inconsistent water and sewer rate structures, failure to address sustainability issues, long term costs, and even commodity pricing needs. Like many other communities our past leaders strove to keep costs exceedingly, and to not address needs and future concerns of our water plant, and our wastewater treatment plant. Both of our facilities are extremely old, and we are facing a situation that requires immediate emergency planning and attention to these infrastructure units.

Enter Matt Lumbert and Joe VanDommelen of the MWRA to assist us in an extensive review of our water and sewer rate program. The amount of expertise held by these two gentlemen was amazing. Not only did they provide an excellent service to our community – they went above and beyond. Both MRWA employees undertook a training approach with our Marine City Staff members, our Board of Commissioners, as well as the public. Each of them always made themselves available, answered numerous questions, and were patient in explaining the work behind their work. We learned so much about the process of professionally establishing a concise and forward-thinking approach to water and sewer rate setting.

I have told many other area community leaders, politicians, etc. of the MRWA, and staff members Lumbert & VanDommelen. I have strongly suggested that the service product they provide is unmatched and available for their communities. At a recent town hall we held were both Matt and Joe gave a presentation – we had in attendance representatives from other communities, so they could learn and understand the process behind setting appropriate water and sewer rates.

I want to commend and thank both Matt Lumbert and Joe VanDommelen for all their help and assistance with Marine City. We have now come to recognize the other expert services available from the MRWA as well. We will be taking advantage of these services and the expertise behind them soon. With representatives such as Lumbert & VanDommelen – the MRWA is well represented and respected. I cannot express my sincere thanks enough for all their help and assistance.

Sincerely,

Michael W Reaves City Manager

"In the Heart of Blue Water District" Marine City is an Equal Opportunity Provider

REGISTRATION OPENS SOON

Wastewater Conference, February 18–19, 2026, Frankenmuth

Water Distribution School Week, March 9–13, 2026, Northville

Water Distribution School Week, March 30–April 3, 2026, Mt. Pleasant

MRWA 2026 CLASSES IN PROGRESS

OSHA Compliance, First Quarter of 2026, Location TBD

Microsoft Excel and Office, First Quarter of 2026, Saginaw

Excavation Safety Week, Second Quarter of 2026, Multiple Locations TBD ...and many more, so keep an eye on the website and the bi-weekly newsletter. www.mrwa.net

CLARIFIER is made possible by the companies that convey their important messages on our pages. We thank them for their support of the Michigan Rural Water Association and its publication, and encourage you to contact them when making your purchasing decisions. To make it easier to contact these companies, we have included the page numbers of their advertisements, their phone numbers, and, where applicable, their websites.

Fleis & Vandenbrink

JETT

•