Industrial

Agriculture

9 billion animals are raised for food each year in the United states, most of them on Concentrated Animal Feed Operations (CAFOs), which operate covertly and largely outside of EPA regulations. Aside from the cruel living conditions that life is subjected to on these industrial farms, CAFOs are an environmental disaster that produce noxious odors, release methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and produce nitrates that pollute local waterways and disrupt local ecologies.

Historically, architecture has not recognized industrial agriculture as a social, spatial, ethical and ecological concern - which has led to “buildings” on factory farms to be appropriated by large corporations. These buildings are conversion mechanisms with a primary function of converting vibrant life into products. The design of hyper efficient spaces in factory farms perpetuates this conversion.

If a building can act as a machine whose primary goal is profit, what are the opportunities for architecture to act as an imperfect machine with goals of land remediation, biological and terrestrial care.

In the medieval open field system, land was communally organized and privately owned. Shared stewardship of the open field meant that the health of the field and the productivity of the crops was dependent on the animals and community that cultivated the land. A 3 field crop rotation allowed one field to always recover in between growing seasons which ensured the natural replenishing of nutrients in the soil.

In the Medieval system, the animal was a necessary component in the production of its own food. The Medieval open field system also reflected a closer relationship between the site of production and Consumption.

Agricultural Episode 1: Medieval Open Field System

Oat / Barley Fallow

During the 1930s, the introduction of the gas engine into agriculture meant human and animal labor was replaced with machinery. Farms were able to drastically expand and through this expansion, produce surplus goods. This meant farms could now be profitable, and a viable business. The addition of the machine into the landscape meant human and animal labor was largely removed from the production process. Car engines created a new mechanical workforce. The health of the animals was no longer considered in the production process. Animals became an input into the system instead of an contributor.

Expansion west across the united states led to increased plowing and tilling of unsuitable land which eventually led to the Dust Bowl. The new agricultural system that could produce a surplus, could no longer produce enough to sustain the growing demand for food. The division between rural farming areas, and urban areas meant that people were removed from the land and processes of food production.

Agricultural Episode 2: Introduction of the Gas Tractor

Fossil Fuels

Agricultural Episode 3: Introduction of CAFOs

In response to the food instability of the 1930s, the Introduction of fertilizer and genetically modified crops and animals created a new synthetic agricultural landscape - one that is more resistant to food shortages but more intensive on the biological and terrestrial bodies that are used for its production. Concentrated Animal Feed Operations (CAFOs) became a hyper efficient model of producing large amounts of dairy products on a concentrated land area.

The spatial arrangement of these forms allows for surveillance and constant monitoring of life. By consolidating livestock and crop production to one large operation, farms became vertically integrated with the goal of efficiency and profit. The architecture on these sites acts as a perfect mechanism for the conversion of beings into products.

CAFO Spatial Arrangement

PROFIT CO2 CH4

CH4 H2S P4

Agricultural Episode 4: Precision Farming

After the chemical modification of land and organisms started to deplete the environment and make people sick once againPrecision agriculture emerged as a ‘solution’ that focused on Reducing the environmental impact of farming by optimizing Resource use and minimizing runoff of chemicals and nutrients.

Precision farming is the introduction of satellite imaging and GPS to survey the landscape With the data gathered from satellite imaging - variable rate applications of agricultural processes are applied to the land instead of following the modern agricultural trend of uniform chemical saturation. The health and wellbeing of the agricultural landscape is acknowledged as a method of increasing productivity without the need for increased chemical processes.

Precision Farming Spatial Arrangement

Thesis Statement

This thesis investigates the history of entanglements between biological and mechanical systems in industrial agriculture and positions architecture as a spatial and political tool that challenges capital exploitation of land resources.

Architecture becomes an active agricultural agent in regenerating exhausted farming landscapes through scouting, shepherding, grazing, re-mediating and metabolizing resources through interspecies synergy. A decentralized migratory farming collective leverages interspecies entanglement and redistributes power and land locally through a dispersed and variable land organization. This thesis speculates on possible architectures that emerge in a near bio-mechanical future where architecture acts as an imperfect machine towards goals of remediation, biological and terrestrial care.

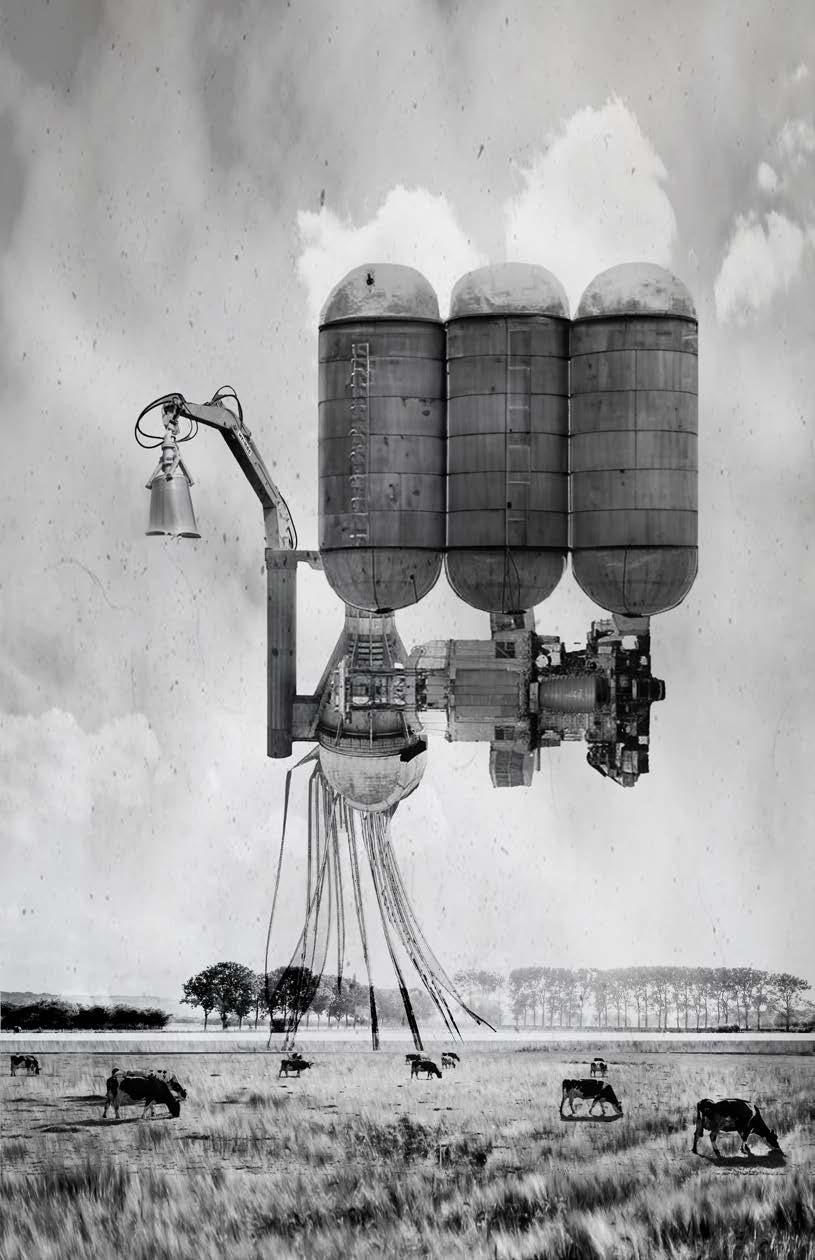

// Barn

// Feed // grain silo

// Digestion Tanks

// CAFO building CAFO Components

The main mechanism of the design is based the ideas from Joe Salatin’s Chicken Tractor : A floorless, movable pasture for chickens to continuously have access to fresh pasture while allowing the land behind to fallow and regenerate.

Cows, Chickens, Rabbits are enrolled in this system because their natural feeding habits and movement are aligned with holistic forms of agriculture and can actually start to re-mediate previously over-tilled and nutrient depleted landscapes. Animals in the system are recognized for their value as ecological agents capable of metabolizing and re-mediating landscapes through the production of their own food and land.

Precedent : Chicken Tractor

This system is pulled slowly across landscape - giving animals access to fresh pasture and allowing land to regenerate behind. This farming technique eliminates the need for antibiotics and GMOs because animals can be raised in pasture instead of in concentrated factory farms.

Scout for fresh pastures

Allow land to rest and regenerate during winter months

20% of farming collective is left behind each year in order to replensih landscapes, liberate creatures and strnegthen local ecology for future farming

Remediate Exhausted Landscapes through species synergy

Pollinate!

Shephard!

Graaaaaze

Program Diagram // Migratory Farming Collective

Metrics

- 48 cows

- 90 chickens

- 72 rabbits

chickens eat weeds // bugs from cow pies and leave behind fresh fertilizer for rabbits + future creatures

the chickens scratch and aerate the sawdust bedding so the rabbit and chicken manure can compost

Forage-based rabbits provide nutrient rich material for chicken / rabbit enclosure

Fresh Pasture

Scout scans/ images landscape to assess health of ecology

Decides which areas are ready for harvest, and which need to rest.

Directs M.F.C

Scouted Landscape approx. 30 miles away

...buzzz

re-seeding farmed landscape

Scouts pollinates landscape through accidental interactions with dust / seeds / microbes

Scouts re-seed overfarmed landscapes to create an ecologically stable silvopasture

Path of M.F.C

Current Location of M.F.C

MICRO SCOUTS // SHEPHARDS

Design Iterations

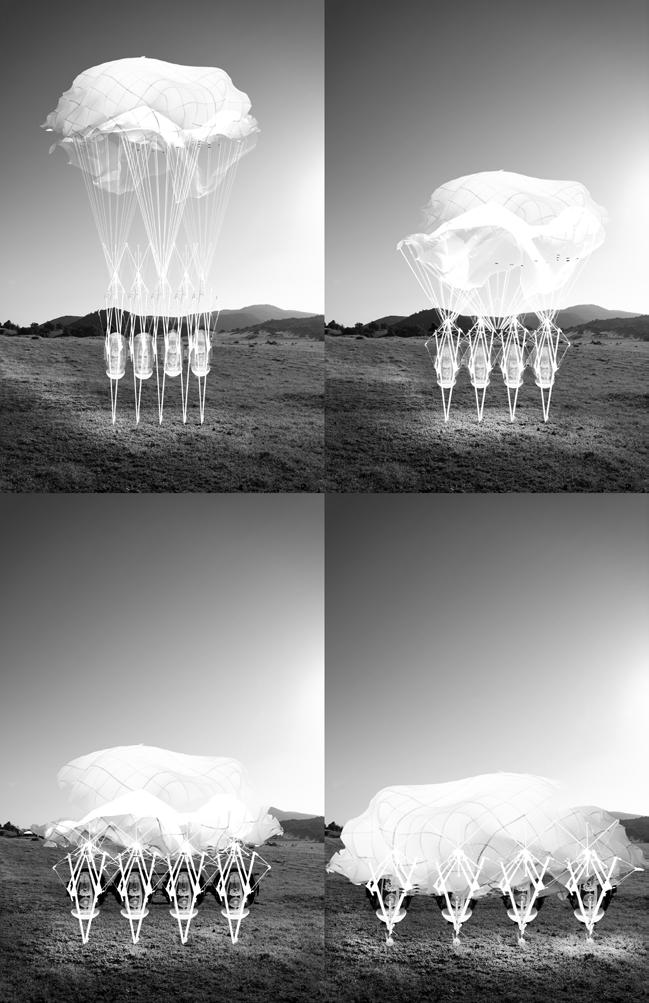

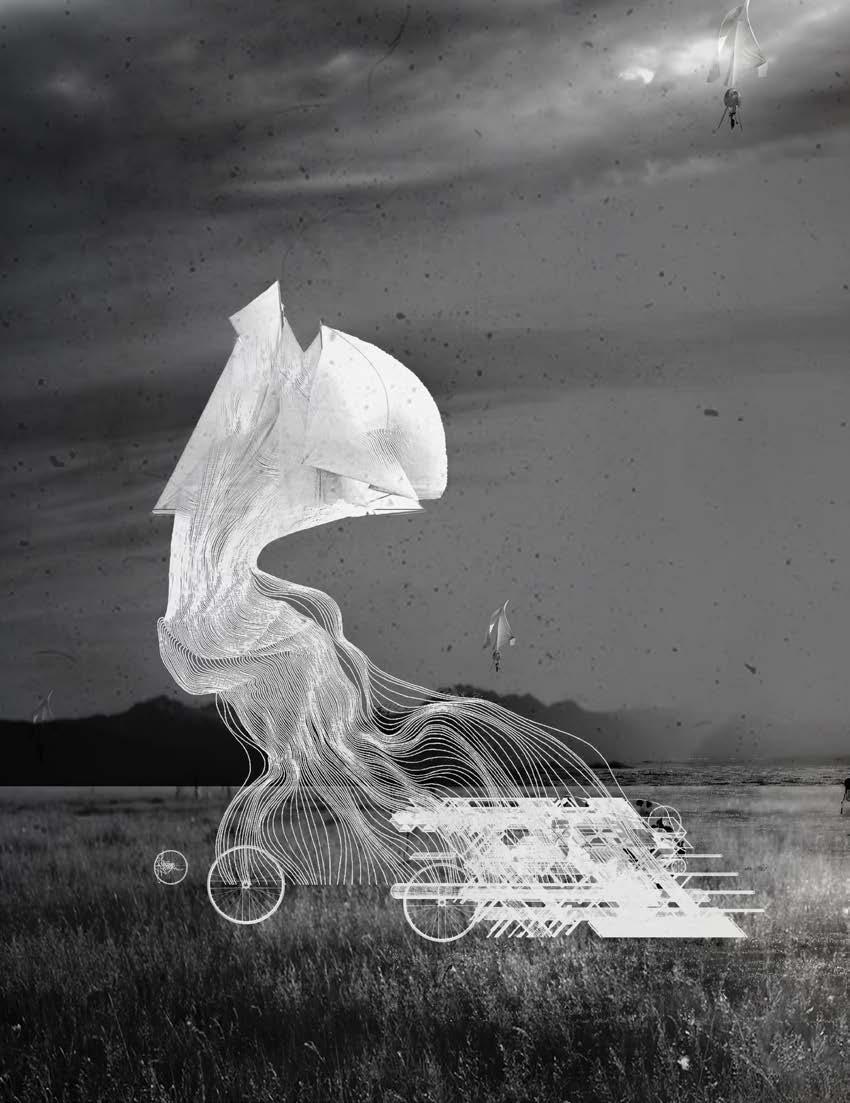

The approach towards the design of the migratory farming collectives is to think of them in terms of generations. Each iteration of the farming system is evaluated for its fitness in the landscape and its effectiveness in providing biological and terrestrial care. Different forms of mobility, growth, and enclosure continuously evolve overtime based on the parameters of their present environment.

An assemblage that is established as fit in the northeast region of the United states will look different, and contain different ecological agents than an assemblage that resides in south America.

The selected design iteration was determined to be ecologically fit in a northeastern rural context through its sustainable form of movement, daily and seasonal formal transformations, and production and replenishment of resources through an agroforestry model.

Inflatable Mobile Resource Collector SILO

“Drifter”

Encampment Collage

A sail structure, in addition to small propellers Receiving information from imaging drones, guides the direction and the speed of the assemblage. The sail contracts at sunrise, allowing the herd to go out to pasture, and slowly expands at sunset to provide shelter. The inhabitants, around 40 chickens and rabbits, 30 cows and fewer than 10 humans loosely constitute the herd. The open system allows for spontaneous forms of coexistence and acknowledges architecture as a co- producer of space.

The concept of passive feeding is employed by the assemblage as a metabolic system. As the Architectural assemblage grazes over the Landscape, the herd metabolizes and deposits Resources creating a hybrid landscape in its path. Scouts, small drones with seed silos, survey landscapes in need of remediation or that are ready to be harvested and report back to the assemblage. The scouts act as pollinators of physical and digital data. This data is used to make autonomous decisions about the health of the land and the movement of the assemblage.

Daily Transformation : Section : Tool Deployment

The assemblage responds directly to the seasonal changes of the landscape, returning back to a more Ritualistic and synchronistic relationship with its environment. Spring consists of agroforestry measures of re-seeding depleted landscapes.

Summer consists of grazing and growing. Fall consists of harvesting for the winter, and distributing surplus resources to local ecologies. Winter is a time for rest. The assemblage remains fixed and the herd is fed through resources harvested from the previous season.

Dawn : Scouts deployed

Covering Conctracts // Animals go out to pasture

Covering Fully Contracted // Rainwater + weather Data Peak Sunlight Hours

Covering Gradually expands to provide shade + shelter as animals wander back in

Rainwater + weather Data collection as animals Graze

Sunlight Hours

Sunset - Midnight - Silos lower to provide Food and Water // Creatures rest

Dusk : Scouts Return

“2015-2019 Desert Infrastructures & El Paisaje Mineral Tiene El Cielo Celeste y Dos Montañas Blancas. – Marcos Zegers.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://marcoszegers.cl/2015-2019_water-mining-and-exodus/.

“2017_Fire in Mono culture Plantations – Marcos Zegers.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://marcoszegers. cl/2017_fire-in-mono culture-plantations/.

Richard Barnes. “Animal Logic.” Accessed October 18, 2022. http://www.richardbarnes.net/animal-logic.

Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/ books/book/chicago/A/bo5956755.html.

“BLACK ALMANAC | BLACK ALMANAC.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://almanac.black/.

Brott, Simone. Architecture for a Free Subjectivity: Deleuze and Guattari at the Horizon of the Real. London: Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315262208.

Burger, Joanna, Michael Greenberg, Charles W. Powers, and Michael Gochfeld. “Reducing the Footprint of Contaminated Lands: US Department of Energy Sites as a Case Study.” Risk Management 6, no. 4 (2004): 41–63.

Routledge & CRC Press. “Cybernetic Architectures: Informational Thinking and Digital Design.” Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.routledge.com/Cybernetic-Architectures-Informational-Thinking-and-Digital-Design/Quin/p/ book/9781032019406.

Drdoš, J. “Landscape Research and Its Anthropocentric Orientation.” GeoJournal 7, no. 2 (1983): 155–60.

Escobar, Arturo. “After Nature: Steps to an Antiessentialist Political Ecology.” Current Anthropology 40, no. 1 (1999): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1086/515799. fabric. “URBAN METABOLISM – Rotterdam | FABRICations.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.fabrications.nl/portfolio-item/rotterdammetabolism/. Grant, Richard J., and Martin Oteng-Ababio. “The Global Transformation of Materials and the Emergence of Informal Urban Mining in Accra, Ghana.” Africa Today 62, no. 4 (2016): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.62.4.01.

Hale, Jonathan. “Architecture, Technology and the Body: From the Prehuman to the Posthuman.” In The SAGE Handbook of Architectural Theory, by C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, and Hilde Heynen, 513–33. 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012. https://doi. org/10.4135/9781446201756.n31.

Heisel, F., D. E. Hebel, and W. Sobek. “Resource-Respectful Construction – the Case of the Urban Mining and Recycling Unit (UMAR).” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 225 (February 2019): 012049. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/225/1/012049.

“Holly Hendry Wins the 2019 Experimental Architecture Awards with Playful Sculptural Works | ArchDaily.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.archdaily.com/910351/holly-hendry-wins-the-2019-experimental-architecture-awards-with-playful-sculptural-works.

“Ilya Iskhakov | RISD Museum Publications.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://publications.risdmuseum.org/ grad-show-2021-landscape-architecture/ilya-iskhakov.

“Index : P A K U I H A R D W A R E.” Accessed October 18, 2022. http://www.pakuihardware.org/.

Iskhakov, Ilya. “Mutable Landscapes: Diversity through the Lens of the Earth’s Biomass.” Masters Theses, June 1, 2021. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/masterstheses/772.

Jorgensen, Estelle R., and Iris M. Yob. “Deconstructing Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus for Music Education.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 47, no. 3 (2013): 36–55. https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.47.3.0036.

“Jun Jiang | RISD Museum Publications.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://publications.risdmuseum.org/ grad-show-2021-landscape-architecture/jun-jiang.

Keller, David R. “Toward a Post-Mechanistic Philosophy of Nature.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 16, no. 4 (2009): 709–25.

Kennedy, Christopher, John Cuddihy, and Joshua Engel-Yan. “The Changing Metabolism of Cities,” n.d., 17.

Langevin, Jared. “Reyner Banham: In Search of an Imageable, Invisible Architecture.” Architectural Theory Review 16, no. 1 (April 2011): 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2011.560389.

———. “Reyner Banham: In Search of an Imageable, Invisible Architecture.” Architectural Theory Review 16, no. 1 (April 2011): 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2011.560389.

Latour, Bruno. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime. John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

JeremyBlum.com. “Machine Metabolism,” November 21, 2011. https://www.jeremyblum.com/portfolio/machine-metabolism/.

Moore, Jason W. “Introduction: World-Ecological Imaginations.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 37, no. 3–4 (2014): 165–72.

Andrés Jaque / Office for Political Innovation. “More-than-Human.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://officeforpoliticalinnovation.com/book/more-than-human/.

Morton, Timothy. Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Harvard University Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1n3x1c9.

Nelson, Howard J. “The Spread of an Artificial Landscape Over Southern California.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 49, no. 3 (1959): 80–99.

MAX SHUSTER Photography. “OCTOPODAL ORIGINS.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.maxshuster. com/octopodal.

CCCB LAB. “Our Monsters,” July 18, 2017. https://lab.cccb.org/en/our-monsters/.

“Participants – TAB.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://2022.tab.ee/participants/.

“Permafrost. Forms of Disaster at MO.CO. Panacée – Art Viewer.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://artviewer.org/ permafrost-forms-of-disaster-at-mo-co-panacee/.

Pevzner, Nicholas, and Sanjukta Sen. “Preparing Ground.” Places Journal, June 29, 2010. https://doi. org/10.22269/100629.

“Post Natural History — Film 3’30 – Vincent Fournier.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.vincentfournier. co.uk/www/portfolio/post-natural-history-film-330/.

“Preparing Ground.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://placesjournal.org/article/preparing-ground-interview/?cn-reloaded=1.

Richard Barnes. “Projects + Exhibitions.” Accessed October 18, 2022. http://www.richardbarnes.net/projects.

“Robot Protective Jacket for Food Processing(For VS((Options(DENSOWAVE.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.denso-wave.com/en/robot/product/option/rpjacket.html.

Seidler, Paul, Paul Kolling, and Max Hampshire. “Can an Augmented Forest Own and Utilise Itself?,” n.d., 6.

Sheller, Mimi. “The Origins Of Global Carbon Form.” Log, no. 47 (2019): 56–68.

Smith, Albert C., and Kendra Schank Smith. “Architecture as Inspired Machine.” Built Environment (1978-) 31, no. 1 (2005): 79–88.

Stevermer, Tyler Jon. “Preposthuman : An Architectural Propaedeutic for the Digitally-Enhanced.” Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2015. https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/97274.

Stuck, Franz, Ritter von, 1863-1928. “Internationale Hygiene-Ausstellung.” Accessed October 11, 2022. https://jstor. org/stable/community.28561477.

Synthetic Landscapes. “Synthetic Landscapes.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://architecture.pratt.edu/articles/ synthetic-landscapes.

“The Man Machine – Vincent Fournier.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://www.vincentfournier.co.uk/www/category-portfolio/works/the-man-machine/.

sabukaru. “THE METABOLISM MOVEMENT - THE PROMISED TOKYO.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://sabukaru.online/articles/the-promised-tokyo.

MIT Press. “Things We Could Design.” Accessed October 11, 2022. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262542999/thingswe-could-design/.

“Tia Randall – UNIT 21.” Accessed October 18, 2022. https://unit-21.com/?p=149.

“Urban Morphogenesis Lab - MICROBIAL CELLULOSE [Metabolizing Urban Waste] 2015/2016.” Accessed October 18, 2022.

https://urbanmorphogenesislab.com/microbial-cellulose-20152016.

Wang, Hsi-Chuan. “Case Studies of Urban Metabolism: What Should Be Addressed Next?” Urban Affairs Review, February 15, 2022, 10780874221080144. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874221080145.

“Wayback Machine,” December 17, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20081217050150/http://www.iwa.tuwien. ac.at/htmd2264/publikat/aws-publikationen/Publikationen/2001/Anthropogenic%20Metabolism%20and%20Environmental%20Legacies.pdf.

Yaneva, Albena. “Beatriz Colomina, X-Ray Architecture.” Ardeth. A Magazine on the Power of the Project, no. 8 (November 1, 2021): 194–96.

Zonaga, Anthony. “Anthropotopia: Kisho Kurokawa and the Metamorphosis of the Metabolist Utopia.” Accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.academia.edu/27022556/Anthropotopia_Kisho_Kurokawa_and_the_Metamorphosis_of_the_Metabolist_Utopia.

Thank you.