Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance 1st Edition

Amy Kenny

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/humorality-in-early-modern-art-material-culture-and-p erformance-1st-edition-amy-kenny/

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN LITERATURE, SCIENCE AND MEDICINE

Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance

Edited by Amy Kenny Kaara L. Peterson

Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine

Series Editors

Sharon Ruston

Department of English and Creative Writing

Lancaster University

Lancaster, UK

Alice Jenkins School of Critical Studies

University of Glasgow

Glasgow, UK

Jessica Howell

Department of English

Texas A&M University

College Station, TX, USA

Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine is an exciting series that focuses on one of the most vibrant and interdisciplinary areas in literary studies: the intersection of literature, science and medicine. Comprised of academic monographs, essay collections, and Palgrave Pivot books, the series will emphasize a historical approach to its subjects, in conjunction with a range of other theoretical approaches. The series will cover all aspects of this rich and varied feld and is open to new and emerging topics as well as established ones.

Editorial board

Andrew M. Beresford, Professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, Durham University, UK

Steven Connor, Professor of English, University of Cambridge, UK

Lisa Diedrich, Associate Professor in Women’s and Gender Studies, Stony Brook University, USA

Kate Hayles, Professor of English, Duke University, USA

Jessica Howell, Associate Professor of English, Texas A&M University, USA

Peter Middleton, Professor of English, University of Southampton, UK

Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, Professor of English and Theatre Studies, University of Oxford, UK

Sally Shuttleworth, Professorial Fellow in English, St Anne’s College, University of Oxford, UK

Susan Squier, Professor of Women’s Studies and English, Pennsylvania State University, USA

Martin Willis, Professor of English, University of Westminster, UK

Karen A. Winstead, Professor of English, The Ohio State University, USA

More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14613

Amy Kenny • Kaara L. Peterson Editors

Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance

Editors

Amy Kenny

University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA, USA

Kaara L. Peterson

Miami University of Ohio Oxford, OH, USA

ISSN 2634-6435

ISSN 2634-6443 (electronic)

Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine

ISBN 978-3-030-77617-6

ISBN 978-3-030-77618-3 (eBook)

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77618-3

© The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affliations.

Cover illustration: The Artchives / Alamy Stock Photo

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

Acknowledgments

The editors would like to thank everyone at Palgrave who worked on this book for their support and enthusiasm throughout the process. Some of the essays featured in this collection emerged from a Shakespeare Association of America seminar entitled “Performing the Humoral Body” at the Los Angeles conference in 2018. We would like to thank the organizing committee for their support of the seminar.

v

vii 1 Introduction—Everyday Humoralism 1 Amy Kenny and Kaara L. Peterson Part I Per formance and Embodiment 11 2 Humoural Versifcation 13 Robert Stagg 3 Like Furnace: Sighing on the Shakespearean Stage 31 Darryl Chalk 4 “Great Annoyance to Their Mindes”: Humours, Intoxication, and Addiction in English Medical and Moral Discourses, 1550–1730 51 David Clemis 5 Performing Pain 69 Michael Schoenfeldt 6 A “Dummy Corpse Full of Bones and Entrails”: Staging Dismemberment in the Early Modern Playhouse 85 Amy Kenny contents

viii CONTENTS Part II Art and Material Culture 103 7 Elizabeth I’s Mettle: Metallic/Medallic Portraits 105 Kaara L. Peterson 8 Seeing Saints in the Forest of Arden: Melancholic Vision in As You Like It 125 Kimberly Rhodes 9 Humors, Fruit, and Botanical Ar t in Early Modern England 147 Amy L. Tigner 10 The Humorality of Toys and Games in Early Modern English Domestic Tragedy 167 Ariane Balizet 11 Afterword—No One Is Ever Just Breathing or, a Sigh Is (Not) Just a Sigh 189 Gail Kern Paster Index 199

notes on contributors

Ariane Balizet is the author of two monographs—Shakespeare and Girls’ Studies (Routledge, 2020) and Blood and Home in Early Modern Drama: Domestic Identity on the Renaissance Stage (Routledge, 2014)—and many articles on blood, bodies, and domesticity in the literature of the English Renaissance. Her work has been published in Comparative Literature Studies, Early Modern Literary Studies, Women’s Studies, and Borrowers and Lenders, and elsewhere.

Darryl Chalk is Senior Lecturer in Theatre at the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, and Treasurer on the Executive Committee of the Australian and New Zealand Shakespeare Association. He researches medicine, disease, magic, and emotion in Shakespearean drama and early modern theatre. His most recent book is Contagion and the Shakespearean Stage (Palgrave, 2019), a volume of essays coedited with Mary Floyd-Wilson. A monograph, with the working title Pathological Shakespeare: Contagion, Embodiment, and the Early Modern Scientifc Imaginary, is currently in progress.

David Clemis is Associate Professor of History at Mount Royal University, Calgary, Canada. His research focuses on understandings of alcohol intoxication and conceptions of craving, habit, and addiction in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He is the author of “Medical Expertise and the Understandings of Intoxication In Britain, 1660 to 1830,” in Intoxication and Society: Problematic Pleasures (Palgrave, 2013), “The History and Culture of Alcohol and Drinking: 18th

ix

Century” and “The History of Addiction and Alcoholism” in Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives (SAGE, 2015).

Amy Kenny teaches at University of California, Riverside and has a PhD in early modern literature and culture. She has worked as Research Coordinator at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, where she was the chief dramaturge for 15 productions and conducted over 80 interviews with actors and directors on architecture, audiences, and performance, as part of an archival resource for future scholarship. She is co-editor of The Hare, a peer-reviewed, on-line academic journal of untimely reviews, on the editorial board of Shakespeare Bulletin, and has published articles on dramaturgy, the performance of laughter, the senses, and disease in Shakespeare. Her frst monograph, entitled Humoral Wombs on the Shakespearean Stage, was published in 2019.

Gail Kern Paster is Director Emerita of the Folger Shakespeare Library and Editor Emerita of Shakespeare Quarterly. She is the author of The Idea of the City in the Age of Shakespeare (University of Georgia, 1986), The Body Embarrassed: Drama and the Disciplines of Shame in Early Modern England (Cornell, 1993), and Humoring the Body: Emotions on the Shakespearean Stage (University of Chicago, 2004). She co-edited Reading the Early Modern Passions (University of Pennsylvania, 2004), and has written many essays on the history of emotion. She has been a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow, a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellow, and a Mellon Fellow. She has served as President of the Shakespeare Association of America and, in 2011, was named to the Queen’s Honours List as Commander of the British Empire.

Kaara L. Peterson is an Associate Professor of English at Miami University of Ohio. Exploring the intersections of Renaissance medical history, art history, and literature, she has published most recently in English Literary Renaissance, Renaissance Quarterly and Studies in Philology, focusing on the representations and iconography of virginity and Elizabeth I. Her other published work appears in Shakespeare Quarterly, Shakespeare Studies, and Mosaic and includes a monograph on early modern literature and popular medicine (Ashgate, 2010), as well as co-edited volumes with Stephanie Moss on the staging of early modern pathology (Ashgate, 2004) and with Deanne Williams on the interdisciplinary “afterlives” of Ophelia (Palgrave, 2012).

x NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

Kimberly Rhodes is NEH Distinguished Teaching Professor of the Humanities and Professor of Art History at Drew University. She has written extensively on Ophelia and visual culture, most recently for a monograph of contemporary artist Nadja Verena Marcin’s work. Her new research concerns the representation of deer in British art and literature and includes the essay “‘A haunch of a countess’: John Constable and the Deer Park at Helmingham Hall,” published in collection Ecocriticism and the Anthropocene in Nineteenth Century Art and Visual Culture (Routledge, 2019).

Michael Schoenfeldt is the John Knott Professor of English Literature at the University of Michigan. He is the author of Prayer and Power: George Herbert and Renaissance Courtship (University of Chicago, 1991), Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England: Physiology and Inwardness in Spenser, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton (Cambridge, 1999), and The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare’s Poetry (2010), as well as editor of the Blackwell Companion to Shakespeare’s Sonnets (Blackwell, 2006), and John Donne in Context (Cambridge University, 2019).

Robert Stagg is a Leverhulme Research Fellow at the Shakespeare Institute and an Associate Senior Member of St Anne’s College, University of Oxford. Stagg has published essays in Shakespeare Survey, Essays in Criticism, Studies in Philology, and numerous edited collections, and is fnishing a book about Shakespeare’s blank verse.

Amy L. Tigner teaches English at the University of Texas, Arlington and writes about early modern food, gardens, and ecological concerns. Her most recent co-edited books include Literature and Food Studies with Allison Carruth (Routledge, 2018) and Culinary Shakespeare with David B. Goldstein (Duquesne, 2017). She is the author of Literature and the Renaissance Garden from Elizabeth I to Charles II (Ashgate, 2012). Tigner is also the founding editor of Early Modern Studies Journal and a founding member of Early Modern Recipes Online Collective (EMROC), a digital humanities project dedicated to manuscript recipe books.

xi NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

list of figures

xiii

Fig. 7.1 Elizabetha Angliae et Hiberniae Reginae, Thomas Cecill, c. 1625. © The Trustees of the British Museum 106 Fig. 7.2 Detail from Elizabetha Angliae et Hiberniae Reginae, Thomas Cecill, c. 1625 © The Trustees of the British Museum 107 Fig. 7.3 “Dangers Averted” Medal, Elizabeth I (1558–1603), CM.YG.1401-R. Attributed to Nicholas Hilliard (1537–1619), c.1588. Gold medal. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge 109 Fig. 7.4 Wax seal, The Great Seal of Elizabeth I, 1586–1603, reverse. The National Archives of the UK, ref. SC13/N3 113 Fig. 8.1 Albrecht Dürer, Saint Eustace, c. 1501, engraving, 35 × 25.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1919. www.metmuseum.org 126 Fig. 8.2 Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia 1, 1514, engraving, 24 × 18.5 cm., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1943, www.metmuseum.org 132 Fig. 8.3 The Legend of St. Eustace, c. 1480, wall painting, Canterbury Cathedral, International Photobank/Alamy Stock Photo 137 Fig. 8.4 Titian, St. Eustace, drawing, 21.6 × 31.6 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum 140 Fig. 9.1 “The Tradescant Cherry” from The Tradescants’ Orchard, Ashmole MS. 1461, f.25r, with permission from Bodleian Libraries 157

Fig. 9.2 Nathaniel Bacon, Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit, c. 1620–25, Tate

Fig. 10.1 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Children’s Games (1560), detail. Image credit: KHM-Museumsverband. Reproduced with permission

xiv LIST OF FIGURES

159

177

CHAPTER 1

Introduction—Everyday Humoralism

Amy Kenny and Kaara L. Peterson

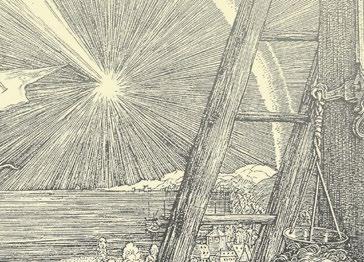

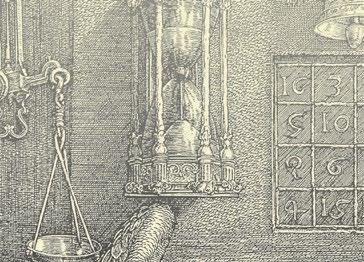

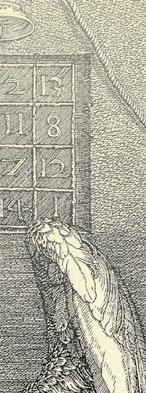

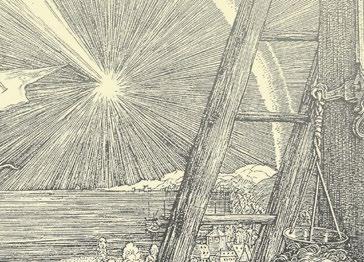

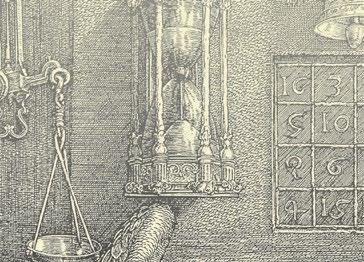

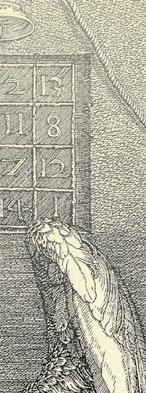

Beneath the laurel-crowned, winged allegory of Melancholy in Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia 1 (1514), several objects are strewn about the foor, including carpenter’s tools—a set-square, a plane, and a few scattered nails—along with pincers, a crucible, and a clyster (used to evacuate plethoric humors). This engraving, a focus of Chap. 8 in this volume, prompts the beholder to consider the humorality and lived experience of melancholy by depicting it through a series of symbolic, scientifc, and material objects, capturing an arcane symbolism. Dürer asks the viewer to contemplate the multivalent nature of melancholy, not merely imagined as an inward, corporeal state theorized by Galenism, but also as an embodied experience, linked to the natural, mathematical, and scientifc phenomena of the early modern world. While an excess of melancholy humor, or black bile, was associated with insanity and a requisite melancholy complexion,

A. Kenny (*)

University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA e-mail: amy.kenny@ucr.edu

K. L. Peterson

Miami University of Ohio, Oxford, OH, USA e-mail: petersk7@miamioh.edu

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

A. Kenny, K. L. Peterson (eds.), Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance, Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77618-3_1

1

it was also long alleged to be a source of creative genius in the period, a notion the image refers to through its many objects related to intellectual study. By depicting melancholy in this multi-faceted way, the engraving reminds viewers that the medical instruments and carpenter’s tools scattered across the foor at Melancholy’s feet were all linked to the cosmos, humors, and elements in ways that now seem remarkably strange to modern readers. Objects or inanimate things were believed to contain elemental characteristics, not merely metaphorically, but materially within humoral discourse. Seen in this light, Dürer’s famed image partly suggests one of the central premises of this collection that we invite readers to contemplate: the way in which Galenic humoralityin its different expressions and composition fnds exemplifcation in one of the period’s most iconic works of art as well as in many accessory objects and social practices, all more familiar to early modern viewers’ eyes than to ours.

It is now well recognized that Galenic humoral theory underpinned early modern medical practices and the maintenance of health, an antique discourse used to describe interiority and emotion: medical practitioners understood “temperament” or psychological and physiological bodily systems according to a subject’s individual balance of four essential humors— yellow bile (or choler), black bile (or melancholy), phlegm, and blood. But beyond this now-familiar early modern medical framework, how were the humors more broadly understood, constructed, and appropriated to elucidate the experiences of daily life and the broader phenomenological world? For instance, how might Galenic humorality be perceived beyond the immediate example of the human body whose fabric we have grown accustomed to seeing as Galenically infected? How is Galenism understood by early modern individuals as surprisingly constitutive of and manifest within, if latently so, inanimate objects or physical things, both natural (such as fruit or metal) and manufactured (such as a stage property), or even as intrinsic to particular social practices, such as gaming? Beyond the discourse of the traditional Renaissance medical canon, how did early modern humorality materialize in everyday life? How can the humors be understood to lie within the solid matter of Dürer’s many scattered objects, as analogues to metals that grow underground or to the metalwork in which royal portraits are fashioned, or even to underpin the somatic mechanisms of performing verse or breathing? Our collection seeks to address these questions, among others, examining the representation of the humors from less traditional and more abstract, or materialist perspectives, in order to consider more closely the humorality of ordinary,

2

A. KENNY AND K. L. PETERSON

even unremarkable objects, activities, and embodied performance in early modernity.

While we cannot recreate the actual lived experience of another era, the essays here explore how works of art, theater, and various physical objects from the period communicate the extent to which Galenic humoralism shaped individuals’ understanding of routine encounters. Despite the inherently inward human experience that is the typical focus of most critical scholarship, the diverse set of things featured in this collection— from poetry and drama, to paintings and metallic/medallic images, to botanicals and deer, to toys and games—reveal and interrogate different facets of the quotidian humoral experience of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. What unites our collection’s chapters is a recognition that early modern subjects utilize humoral language to articulate a broad range of experiences and matter frequently external to the body’s borders. Of course, as we emphasize above, Dürer’s Melencolia does not allude merely to the melancholy humor in his engraving—a fact established so long ago by Erwin Panofsky as to be a commonplace—but also depicts a veritable catalogue of objects that are equally worthy of note. Taking up this charge, the essays here are concerned more urgently to explore what we might call a broader “catalogue of humorality” that investigates artworks, material culture, and performance in order to uncover the contours of humoral theory in daily life and to render visible the tangible, external markers of this discourse of interiority in new and compelling ways.

Accordingly, our title, Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance, highlights how our contributors discuss representations of the humors in highly diverse mediums. Although the collection is separated into two parts, “Performance and Embodiment” and “Art and Material Culture,” in order to distinguish how humorality informs cultural practice and embodiment versus its different manifestation as a form of production within material culture, we recognize that the chapters occasionally and productively overlap in focus, complicating the orderly distinctions between or among physical body, material object, and created artwork. As a totality that is also the sum of its disparate parts, then, the collection attempts to explore alternative forms of Galenism or thinking heavily infected by Galenism, as well as to reveal just how pervasive humoral theory is in early modern England, underpinning even the most unlikely or unusual things.

3

1 INTRODUCTION—EVERYDAY HUMORALISM

We are honored to have Gail Kern Paster and Michael Schoenfeldt among the contributors to the book, for these scholars stand as undisputed giants who have largely established a feld of early modern studies, specifcally a body of work demonstrating the reach of Galenic humoral theory as well as a focus on how the culture articulates notions of interiority and affect as a means of self-knowledge. Paster’s ground-breaking The Body Embarrassed (1993) and Humoring the Body (2004) consider the portrayal of the humoral body in drama, perhaps most famously identifying the “leaky” female body (a kind of everyday example of Galenic humoralism) and the importance of affect and the “passions” for early modern subjectivity. Another cornerstone of this collection, Michael Schoenfeldt’s Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England (1999) examines the pathologizing of inwardness in humoral bodies in early modern writing. Likewise, Mary Floyd-Wilson’s monographs Occult Knowledge, Science and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage (2013) and English Ethnicity and Race in Early Modern Drama (2003) introduced to many scholars now-familiar concepts of the Galenic “non-naturals” and the humoralclimatological basis for constructions of subjectivity and identity. Beyond analysis of the human body alone, in their important contributions to a growing feld Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Vin Nardizzi have also explored the vital materiality of things in Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (2015) and The Indistinct Human in Renaissance Literature (2012), inviting scholars to consider the often fuid boundaries among object, the natural environment, and human subject. Our collection extends but does not repeat this analysis by extending the scope of humorality to a variety of things or natural phenomena that denote a broader application of the Galenic framework in the period.

While medical theory was undeniably infuenced by Galen, the Hippocratic corpus, and, to a lesser degree, Paracelsus and anatomical discovery throughout the early modern period, there existed a variety of other competing and heterogeneous medical philosophies and practices. Some recent scholarship has suggested an overemphasis on Galenic precepts can produce a reductive approach to thinking about the early modern body, emotions, and spirituality. Works such as Katharine Craik’s collection, Shakespeare and Emotion (2020); Ronda Arab, Michelle M. Dowd, and Adam Zucker’s collection Historical Affects and the Early Modern Theater (2015); and Richard Meek and Erin Sullivan’s The Renaissance of Emotion: Understanding Affect in Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (2015) have all contributed to discussions of emotion and

4

A. KENNY AND K. L. PETERSON

embodiment beyond humorality, showing in compelling ways that Galenism is not the sole means of articulating embodiment, affect, and emotion in the period. Galenic humoral theory is a stable if not static body of knowledge in the early modern period, however; its dominance may be perceived as a matter of degree. Notions of interiority, physicality, health, and emotion were constantly shifting, as were phenomenologies of the natural world, though Galenism stubbornly resists eclipsing. Our collection seeks to expand on existing critical considerations of how the humors gain representation in highly varied media—within material culture, performance, and other forms of cultural production and activities—without necessarily shifting the dominant medical discourse. Recognizing the contributions of recent scholarship, Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance seeks to expand the perspective of everyday humoral experiences and objects or materials to a range of novel focuses. The essays in this collection accordingly do not seek to challenge the dominance of Galenism, rather to supplement the period’s articulation of it as demonstrated more broadly by early modern culture. Ultimately, the volume offers a different account of the signifcance of Galenism by examining new manifestations of its deployment instead of limiting analysis to the human body alone, though many of our essays necessarily situate the human actor or individual within its physical environment.

As most famously outlined by Paster, Galenic models are predicated on the porous nature of the humoral body or “fungibility,” defned by the body’s vulnerability to the surrounding environment, rendering the discourse of physicality as an exploration of the permeable self.1 Paster’s pioneering work sets out how early modern scientifc explanations of animals, plants, and human subjects are deeply informed and characterized by humoralism. Describing the “psychophysiological reciprocity” between a subject and the broader world, Paster notes, “the link between inner and outer is often described in the language of the qualities, since the forces of cold, hot, moist, and dry not only determine a individual subject’s characteristic humors and behaviors but also describe the characteristic behaviors of other living things—animate and inanimate.”2 As she makes clear, Galenic classifcations of temperament do not simply defne human subjects but interpellate the animal and botanical natural worlds. It is these other aspects of the natural world that several of our contributors explore, within two principal areas of investigation outlined below.

The frst section, “Performance and Embodiment,” contains fve essays, each tracing how the humoral body is in fact performative, both on the

5

1 INTRODUCTION—EVERYDAY HUMORALISM

early modern stage and in daily life. The essays in this section are attentive to the affective infuence of the humors in embodiment in various contexts, with each tracing the consequences of performing pain, verse, sighs, dismemberment, alcoholism, or the effect of playing a role on the body, including the actor’s interaction with stage properties. Anti-theatrical tracts from the period often bring together criticism on assorted forms of idleness, playing, drinking, and, as will be explored later in Part II, dicing and gaming, suggesting a range of similar deleterious effects of participating in any of these indulgent revelries.3

Robert Stagg’s chapter, “Humoural Versifcation,” opens the collection by focusing on how rhythms of breathing and heartbeats cultivate a type of humoral versifcation in performance. His essay examines the pace and pauses that make up the somatic experience of performing verse, with a particular focus on how caesuras and (un)stressed syllables infuence the actor’s body on stage. “Like Furnace: Sighing on the Shakespearean Stage,” Darryl Chalk’s chapter, takes up a related thread, focusing on the performativity of sighing and considering how the passions were understood in the early modern playhouse. By connecting the somatic mechanism of sighs to their expression of melancholic affictions, Chalk questions how repetitive sighing might have affected the actor’s body. These questions set the stage for David Clemis’ essay, “‘Great Annoyance to Their Mindes’: Humours, Intoxication, and Addiction in English Medical and Moral Discourses, 1550–1730,” which considers how humoral language defnes the morality of intoxication for individuals in the real world. Clemis traces the early modern Galenic understanding of the unifed mind and body to explore how alcohol consumption shifted an individual’s humoral balance, temperament, and character. He then turns to an epistemology of drunkenness and demonstrates how the very malleability of the humoral body is at work in notions of addiction and intoxication in the period, given that humoral discourse asserts that the construction of the self lies in the interplay between naturals and non-naturals. Alcohol consumption, Clemis argues, thus acts as a non-natural that results in a state of very real cognitive impairment for the subject.

Like Chalk’s and Stagg’s chapters, Schoenfeldt’s “Performing Pain” shows how the rhetoric of inwardness borrowed from humoral discourse can help elucidate the actor’s emotive performance of counterfeiting pain. While pain is invisible, it must be witnessed by theatergoers, Schoenfeldt argues, and therefore is dependent on the audience’s understanding of humoral physiology. The body of the actor, then, is subject to the

6

A. KENNY AND K. L. PETERSON

corrosive consequences of im-passioned performance all the while his task is paradoxically duplicitous, to convince the audience of feigned pain’s authenticity. Drawing on Schoenfeldt’s exploration of how actors performed excruciating dismemberment scenes, Amy Kenny’s essay, “‘A dummy corpse full of bones and entrails’: Staging Dismemberment in the Early Modern Playhouse,” shifts the focus from bodies to objects. Her essay traces how the material composition of disarticulated stage properties—wax, blood, animal products, and paint—retained and were imbued with humoral attributes, capable of exerting their infuence on the body of the actor performing in the theater. Kenny’s essay bridges the two sections by exploring the humorality of objects within the theater and in performance, laying the groundwork for the second section’s focus on art and material culture. Part I’s survey of the quotidian experiences of drinking, watching a play, and performing pain broadens how Galenic models of affect are constituted outside of but also in relation to the individual body. The collection’s two parts thus move from a more pronounced focus on bodies to things, demonstrating their complex interplay.

Part II, “Art and Material Culture,” explores early modern artistic representations and accounts of the relationship between the humors and objects. Attending to the material histories of the humors expressed through things or objects—such as artworks or coins fashioned of metal or mineral paints; the cultural perception of vision construed as “melancholic” or what determines the social practice of consuming and cultivating fruits and fowers; and the potential humoral risk of playing games—this group of essays considers the relationship between the humoral body and the objects that represent or infuence it. In the frst chapter in this section, “Elizabeth I’s Mettle: Metallic/Medallic Portraits,” Kaara L. Peterson investigates what she terms “elemental perfection,” or interpreting Queen Elizabeth I’s embodied material fawlessness as akin to “noble” precious metals of gold and silver. Beginning with Elizabeth’s famous speech from the battlefeld of Tilbury and an illustration of the scene by Thomas Cecill in which the queen’s “mettle” is conveyed by her metal armor, Peterson examines the queen’s image in contemporary metallic portraits, coins, jewels, and badges. Ultimately, the essay offers an alternative to the typical “leaky vessel” discourse about female bodies in the period, instead demonstrating how Elizabeth’s contemporaries perceived her body as elemental, metallic perfection with a “mind of gold” and a “body of brass,” in the Earl of Essex’s phrasing. Her essay offers a more materialist reading, paving the way for deeper explorations of the humoralism that underlies and

7

1 INTRODUCTION—EVERYDAY HUMORALISM

A. KENNY AND K. L. PETERSON

even constitutes individuals’ relationships to other forms of matter or phenomenological experience.

Turning to melancholy stags in Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden, Kimberly Rhodes’ essay, “Seeing Saints in the Forest of Arden: Melancholic Vision in As You Like It,” investigates religious pastoral paintings in her discussion of Jaques’ conversion from melancholic courtier to religious seeker, focusing particularly on St. Eustace as engraved by Albrecht Dürer.

Employing the term “melancholic vision” to defne the humoral and affective impact of the play, Rhodes explores early modern religious visual culture, particularly the fgure of the hunted deer, through the lens of Topsell’s Historie of Four-footed Beasts. If vision itself can be melancholic, then fruit is frequently perceived as humorally suspect. In “Humors, Fruits, and Botanical Art in Early Modern England,” Amy L. Tigner outlines the shift in medical advice about the healthfulness of fruit, from banning fruit consumption in 1569 after the plague to promoting fruit’s salubriousness at the turn of the seventeenth century. Tracing dietary practices and trends in botanical specimen collecting—some also featured in seventeenth-century illustrated books and artworks, including The Tradescants’ Orchard Chap. 9 argues that reproducing beautiful images of fruit, some paired with portraits of female sitters, helped to alter the perception of the humoral status of fruit in the period.

In the fnal essay, “The Humorality of Toys and Games in Early Modern English Domestic Tragedy,” Ariane Balizet considers early modern domestic tragedies, primarily Arden of Faversham and A Yorkshire Tragedy, alongside the cultural history and visual culture of toys and game play to demonstrate how playing games stimulated the humors and Galenic nonnaturals. Her reading situates games as instruments with the ability to regulate the humoral body, posing a potential risk to domesticity by threatening to provoke confict. Through an intersectional approach that locates specifc games such as dice and spinning tops within prevailing humoral precepts, Balizet demonstrates the effect of play on the everfuctuating body and on domestic households and individuals. Balizet’s essay completes the second section, linking materialist and performative understandings of the humors together. The collection concludes with an Afterword from Gail Kern Paster, “No One Is Ever Just Breathing or, a Sigh Is (Not) Just a Sigh,” highlighting the implications for the feld of the new scholarship offered by our contributors. We are pleased to close the collection with Paster’s perspective, given that her work as a totality has almost single-handedly created the possibility for novel interpretations of

8

the humors in early modern culture, demonstrating just how widely construed and pervasive, how urgently resident Galenic humoralism is within visual objects and things. Like Dürer’s Melencolia, the collection is an illustration of the multivalent nature of humoralism that is now largely alien to our modern, subject-oriented ontologies: like Dürer’s famous engraving, our authors also invite readers to extend the view of humorality further beyond traditional limits, locating an everyday humoralism in the quotidian objects that populate the scene of sixteenth- and seventeenthcentury English domestic life.

Notes

1. Paster, Body Embarrassed, 133.

2. Paster, Humoring the Body, 19.

3. See, for instance, Northbrooke, Treatise, and Stubbes, Anatomy of Abuses.

BiBliography

Northbrooke, John. A treatise wherein dicing, dauncing, vaine playes or enterluds with other idle pastimes. London, 1577.

Paster, Gail Kern. The Body Embarrassed: Drama and the Disciplines of Shame in Early Modern England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Paster, Gail Kern. Humoring the Body: Emotions and the Shakespearean Stage Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Stubbes, Philip. The Anatomy of Abuses. London, 1583.

9

1 INTRODUCTION—EVERYDAY HUMORALISM

Performance and Embodiment

PART I

CHAPTER 2

Humoural Versifcation

Robert Stagg

There are “clichés of rhythm” as well as of speech.1 One of those clichés, at least as old as the nineteenth century, hears blank verse adopting the rhythm of a heart. Thus a popular TED-Ed video purporting to explain “Why Shakespeare loved iambic pentameter” cutely concludes that “Shakespeare’s most poetic lines don’t just talk about matters of the heart”—wait for it—“They follow its rhythm.”2 In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, any equation between the heartbeat and metrical beat would have been more diffcult to sustain. Contemporary physicians disputed whether the heartbeat and the pulse were synchronous or alternating (Galen, the fons of much Renaissance physiology, reckoned that the pulse was uneven, sometimes beating rapidly, sometimes slowly, sometimes in an unpredictable mixture of the two) which, if transferred by analogy to the metrical, promises something more various than a twotone, de-dum-de-dum prosody.3 Moreover, the heart was generally conceived of less as a pump than as a “fountain, maintaining the vital economy

R. Stagg (*)

Shakespeare Institute, Warwickshire, UK

University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

e-mail: robert.stagg@ell.ox.ac.uk

© The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

A. Kenny, K. L. Peterson (eds.), Humorality in Early Modern Art, Material Culture, and Performance, Palgrave Studies in Literature, Science and Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77618-3_2

13

R. STAGG

of the body” (while being, as today, “the source of desire, volition, truth, understanding”).4

The relationship between heartbeat and metrical beat—“the cardiac connection,” in Alan Holder’s phrase—is rarely conceived the other way around, but if both heart and metre survive on pulse then why should metre not affect the heart too?5 In the manuscript of The Return from Parnassus (c. 1601), Judicio refers to Shakespeare’s “heart-throbbing lines” (2.1.302; “heart-robbing” in the 1606 printed text) as though the lines provoke the heart’s throbbing rather than the heart the lines’ throbbing.6 The heart’s metre, such as it was, might in fact tell us more about the rhythm of the passions than the rhythm of iambic pentameter. As Thomas Wright had it, writing of The Passions of the Mind in General (1601), “All passions may be distinguished by the dilation, enlargement or diffusion of the heart, and the contraction, collection or compression of the same, for (as afterwards shall be declared in all passions) the heart is dilated or coarcted more or less” (that last verb of Wright’s is now medically specifc to the heart’s aorta, whereas in 1601 “coarct” could mean more generally “To press or draw together; to compress, constrict, contract, tighten”).7 The distinguishing done by the heart in Wright’s treatise is far from binary or two-tone, despite its culmination in a twofold division between dilation and coarction. Dilation is earlier distinguished from diffusion and contraction from compression, for instance. The heart’s movements are fexible, plural, improvisational, even, as it seeks or happens to record the action of the passions around the body. Where the “pulse” theory of the heart produces a metrical account of verse, straitening it into two discrete stress categories, Wright’s yields something more rhythmic, which is suffciently protean to work outside a strict metrical time signature or structure.

Another popular physiological account of metre fgures it as corresponsive with breath or breathing. There is often said to be a natural relationship between iambic pentameter and breath; specifcally, that we can comfortably speak an iambic pentameter line with one breath (though the director Tyrone Guthrie thought that actors should be able to manage twelve syllables in one gulp).8 However, this “cliché of rhythm” is also dubious. Given that the alexandrine (twelve-syllable line) is the French equivalent of the iambic pentameter, and is similarly lauded in France as a natural, breathable form, in order to sustain the cliché “we would have to develop a poetics of respiration that has the French breathing less often than the English.”9

14

At least the connection between metre and breath has proper sixteenthand seventeenth-century precedent; it is not wholly anachronistic, as metrical accounts of the pulse often are. Verse (as well as prose) punctuation of the period was “a guide to breathing and pausing rather than […] to the syntactical relationship between grammatical clauses,” a notion that is sometimes expressed with the term “rhetorical punctuation” (which risks being misleading, since it implies that early modern punctuation was designed for oratorical performance).10 Thus for Mindele Treip, Milton’s epic similes in Paradise Lost (1667) should be read “as a single, extended verse period, punctuated not grammatically but rhetorically.”11 They should be read by the lungs as much as by the eyes and ears. Grammarians from Francis Clement to Elisha Coles consistently identifed the syllable with breath, and Thomas Campion described how “English monosyllables enforce many breathings.”12 Most notably of all, the caesura was routinely described as a “breathing place.”13

Today we think of the caesura as a pause. This need not, of course, mean that every constituent element of the verse simply stops. The pause could be more analogous to a musical rest, where the momentum of the phrase is unabated; pause “does not necessarily imply a cessation of the voice” since the prolongation of a word can constitute a pause.14 Indeed Shakespeare often treats subclause as a type of pause, where his language seems to pause (or brace) against itself. In the manuscript of Sir Thomas More (c. 1596), for example, he writes the words “Alas, alas!” in the middle of a verse line, separating an exasperated ejaculation, “And lead the majesty of law in lyam/To slip him like a hound” (6.136–37), from a new, steadier phrase, “Say now the King” (137).15 “Alas, alas!” appears interlined above a cancelled syllabic equivalent (“saying,” spelled “sayeng” in the manuscript).16 In revising More for publication, Hand C deleted “Alas, alas!”—suspicious of the long line it created but also, perhaps, of the wordy caesura it effected. If the caesura is a pause, whether of cessation or prolongation, it usually allows for the inhalation or exhalation of breath. Richard Mulcaster, the sixteenth-century headmaster of Merchant Taylors’ and St Paul’s schools, taught his pupils how to breathe their way through verse: “Now in the breathing there are three things to be considered, the taking in, the letting out, and the holding in of the breath” (Mulcaster’s vocal coaching helps us to hear how the caesura can also be a pause in breathing, a “holding in,” rather than or as well as a cue for breathing).17

Accounts of the humours or passions conceived of the body not only as permeable by fuid but by “wind,” “spirit,” and “air”—the body was, as

15

2 HUMOURAL VERSIFICATION

R. STAGG

Helkiah Crooke put it, “Transpirable and Trans-fuxible, that is, so open to the air that it may pass and repass through” it.18 For Crooke, the body’s spirits have a “motion” which is “sudden and momentary like the lightning, which in the twinkling of an eye shooteth through the whole cope of Heaven” or—he swivels about his simile—“they are like the wind which whisks about in every corner and turns the heavy sail of a windmill, yet can we not see that which transports it.”19 “The air works on all men,” Robert Burton writes, “when the humours by the air be stirred, he goes in with them, exagitates our spirits, and vexeth our souls; as the sea waves, so are the spirits and humors in our bodies, tossed with tempestuous winds and storms.”20 The tightenings and loosenings of the heart, by which we might read the body’s humours, are accompanied by the gusting and buffeting of the winds coursing along and within it.

While the humoural body is often considered heavy with fuid, groaning under the weight of its accumulated bile and phlegm, needing drainage for precisely this reason, it can also seem remarkably empty, a sort of corridor through which breezes whizz and skim, with those breezes held back and shaped only by the throat and mouth. The throat supplies “the greater or lesser restraining of the air”; the mouth is “vaulted” such “that the air being repercussed, the voice may be sharper.”21 We might, then, think of the caesura as a porous point in the verse—allowing breath to leak out of or be allowed into the line—but also as a vector by which the fow of that breath (or air or spirit or wind) can be controlled and directed; the caesura may therefore work a little like the Tudor surgeon Thomas Vicary’s extraordinary conception of the hair, in which the hair suppresses the body’s vapours lest “the fumosities of the brain might ascend and pass lightlier out” of the leaky bald head.22

The staging of a play depends on “windy suspiration of forced breath” (as Hamlet bitterly describes it (1.2.79)), where the spirits or winds of the body are ostensibly regulated and expelled by the “propulsive force” of the actors’ mouths, throats and lungs.23 Carolyn Sale has described the 1599 Globe Theatre as “a pair of lungs that scatter throughout its environment” the actors’ particular breath, even as it also draws on and allows space for the breathing lungs of its individual audience members.24 Put this way, the experience of a theatre can seem grotesque—even, during a time of airborne pandemic, dangerous—rather than pleasingly collaborative. In any event, if the theatre itself serves as an “instrument” for the breath, or the various breaths of its constituent peoples, then so too does the caesura.25 It structures and moulds the breathy spirits of an actor’s

16

utterances, helping to decide (though without absolutely or unilaterally determining) whether those utterances should be sighed or soughed or panted or wheezed or many other things besides.

And what happens when the caesura becomes not a “breathing place” but a place where breathing ends? Knowing that she has been poisoned, John Ford’s character Hippolita (in ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore, frst printed 1633) inhales as much breath as she can over twelve lines, each of which heave with caesura: “Kept promise, (o, my torment) thou this houre/ Had’st dyed Soranzo—heate aboue hell fre—/Yet ere I passe away— Cruell, cruell fames—” (4.1.89–91; G4r in 1633 quarto text).26 These caesuras pant with desperate, expiring life; we can almost hear Hippolita’s breath escaping through the gaps or pores in her verse lines. All the characters in 5.1 of Christopher Marlowe’s (and Thomas Nashe’s?) Dido Queen of Carthage (frst printed 1594) can be heard to die upon their caesuras. Dido pivots on a caesura to make an antithesis between “false Aeneas,” who will live, and herself, who will die, so that the caesura becomes her last breath (at least in English): “Liue false Aeneas, truest Dido dyes” (312; G3v in the 1594 quarto text).27 Iarbas follows Dido onto the pyre through her caesura (“Dido, I come to thee, aye me Aeneas” (319; G3v)). Then Anna follows Iarbus: “Now sweet Iarbas stay, I come to thee” (328; G3v). In the 1594 quarto text of the play, quoted here, the caesuras are relatively “lightly pointed”; in a modernised edition, there would in all likelihood be more punctuated caesuras in the lines (though they would still cluster or hinge around the lines’ midpoint).28 These caesuras are the moment at which the play’s characters decide upon death or, alternatively, they are the characters’ last breaths having made their resolution to die. Doctor Faustus’ dying caesura is likewise both a last gasp and a last gasp attempt at salvation: it comes between his fnal clutchings at the material world (“I’le burne my bookes,” he says, having promised to “breathe a while” (14.120, 118; F3v in the 1604 “A” text; H3v in the 1616 “B” text)) and the ultimate realisation of his demise (“oh, Mephistophilis” (120; “Ile burne my books, ah Mephastophilis” in the 1604 text)). The caesura allows room for a range of tones to mingle—the “oh” or “ah” that breathes out of it, at the last, is an undecidable combination of regret, consummation, release, and surrender.

We might think too of how caesura works (or does not work) in “shared lines”—one line spoken by more than one character—which smudge or fudge the point of breathing, in that it becomes more diffcult to determine quite where that breathing happens (the verb “shared” does

17

2 HUMOURAL VERSIFICATION

insuffcient justice to the range of ways in which verse lines can be divided between their speakers). Where is the caesura, the breathing place or places, in these lines? The shared lines of modern-day Shakespeare editions can seem a textual anachronism—following in the metrical footsteps of George Steevens, the eighteenth-century pioneer of the editorial shared line, modern editors can seem to be “making use of what may be called metrical white space” to present a series of fragmentary or short lines as really being part of a whole, “platonic,” perfect pentameter.29 Yet shared lines do appear in a number of Shakespeare’s sixteenth- and seventeenthcentury texts. Here is how one episode is formatted in the quarto or “history” text of King Lear (1608):

Duke. Great thing of vs forgot, Speake Edmund, whers the king, and whers Cordelia

Seest thou this obiect Kent

The bodies of Gonorill and Kent. Alack why thus. Regan are brought in.

Bast. Yet Edmund was beloued, The one the other poysoned for my sake, And after slue her selfe. Duke. Euen so, couer their faces. (5.3.235–41; Q 3192–99)

The quarto heaves with shared lines, as though every character wants to participate in one (does Kent’s “Alack why thus” share with Albany’s “Seest thou this obiect Kent” or the Bastard’s “Yet Edmund was beloued” or, somehow, both?). Could we imagine these characters stealing breath from one another, or sharing breath in the space of the caesura as the line relays between voices, or simply speaking in order to allow another to breathe? Edmund’s short line—“Yet Edmund was beloued”—could be an answer to Kent’s question (“Alack why thus”), interposed so quickly as to take Kent’s breath away, but it is not framed as such, for it begins in a syntax of self-disputation not conversational response (“Yet Edmund was beloved”). His epiphanic line appears to share more with the action described in the stage direction (“The bodies of Gonorill and Regan are brought in”) than it does with Kent’s question. His line is audaciously shared with Goneril’s and Regan’s corpses, which cannot breathe. But then, as Jean-Thomas Tremblay has put it, “no one is ever just breathing.”30

As printed in a modern Shakespeare edition, the shared line exists both horizontally and vertically. Readers’ eyes will run up and down the page, putting the component elements of the line together, and from gutter to

18

R. STAGG

margin, reading along the length or duration of the line. The humoural body is oriented more vertically than horizontally, however. For example, Gail Kern Paster opened her germinal 2004 book about the humours with a “surprisingly vivid comparison” towards this point.31 The comparison belongs to Edward Reynolds, specifcally his Treatise of the Passions and Faculties of the Soule of Man (1640), and it is between the passions of Christ and those of ordinary men: “The Passions of sinfull men are many times like the tossings of the Sea, which bringeth up mire and durt; but the Passions of Christ were like the shaking of pure Water in a cleane Vessell, which though it be thereby troubled, yet it is not fouled at all.”32 One of the striking things about this “anti-Stoic defense of emotion” is its “depth ontology,” the ways in which “The Passions of sinfull men” get “bringeth up” from some undisclosed location beneath.33 The sentence has, Paster notes, a “dense metaphorical layering” and, with it, a syntactical layering that subdues the “mire and durt” of the deep sea in a subclause that itself exists vertically, in grammatical terms, layered as it is beneath the main clause.34

In their myriad imaginings, the humours are frequently subtended by the vertical. Thus, Helkiah Crooke conceives of “the faeculunt excrements” of digestion having “free and direct ascent to the upper parts,” only to be “smothered” downward “in those gulphs of the guts.”35 In fact, the very notion of the humours depends on a “depth model” of somatic truth. It takes the inner meaning of the body, ultimately manifest in its surface symptoms, “to be hidden, repressed […] in need of detection and disclosure by an interpreter” (in this case, primarily a physician).36 Thomas Fienus, the Flemish professor of medicine, warned how “the humours and spirits are borne upwards, downwards, within and without” while Thomas Rogers, writing an Anatomy of the Mind (1576), saw a possibility to “subdue” these “coltish affections.”37

It is possible, albeit with some strain, to map or graft this humoral vocabulary onto a more modern sort of (particularly Shakespearean) character criticism. As Lorna Hutson has noted, character criticism (in its more blatant and its more implicit forms) thrives on “the sense of the inner life implied by words like […] ‘depth.’’’38 So: Shakespeare’s characters have a “deeply physical sense of self” (Michael Schoenfeldt), a “deep subjectivity” (Wes Folkerth), and a “depth” which suggests “all sorts of possibilities in them” (Imtiaz Habib), even if those possibilities are—as one of the frst, eighteenth-century character critics observed—“those parts of the composition which are inferred only and not directly shown,” lingering

19

2 HUMOURAL VERSIFICATION

somewhere below the surface of expression.39 Shakespeare’s characters are routinely fgured as both horizontal, “rounded,” and vertical, plunging from surface simplicity to deep complexity.40 They are psychologically or characteristically voluminous, with “Inner selves,” “inwardness” or “an interior space capable of containing a complicated inner self.”41 “[D]epth,” “deep,” and “deeply”—those keywords of character criticism—all rely on a perception of verticality supervened by authorial pressure (early moderns likewise kept the word “character” very “close to its etymological roots: it meant a brand, stamp or other graphic sign,” something authorially pressed or stuffed down into an otherwise “fat” persona).42

We might fnd one connection between the humours and a particularly twentieth-century character criticism in the earliest phase of Freudian psychoanalysis, as Freud worked out “the corporeal topography of interior and exterior,” yielding a Tiefenpsychologie or “depth psychology” (a term frst adopted by Eugen Bleuler and promptly adapted by Freud).43 By the 1920s, Freud was fguring consciousness as “the surface of the mental apparatus; that is, we have ascribed it a function to a system which is spatially the frst one reached from the external world—and spatially not only in the functional sense but, on this occasion, also in the sense of anatomical dissection.”44 Both psychoanalysis and character criticism can therefore seem to be modes of humourality in centuries that no longer had a strict positivist use for the humours; they re-purpose the vertical language of humourality to new, but also old, effect.

Versifcation is likewise often a matter of depth, for prosodic lineation has a vertical as well as lateral dimension. We have seen and heard how the caesura fgures breath as coming up out of or down into the line. This seems true, too, of prosodic stress, which pressures us to think of “style as though it had an altitude.”45 The sixteenth-century prosodist George Puttenham defned “the sharp accent” as “that which was highest lifted up and most elevated” in the ear; contrarily, “the heavy accent” was that which “seemed to fall down rather than to rise up.”46 Seventeenth-century pedagogues like Charles Hoole and Edward Coote afforded stress a similar verticality, defning it as “the manner of pronouncing a syllable by lifting it up, or letting it down” and “the lifting up of the voice higher in one syllable than in another.”47 Even Derek Attridge, a modern prosodist, who uses the term “beat” rather than the word “stress,” writes of syllables being “promoted” and “demoted,” up and down, in a reader’s ear.48

Both character and stress depend on a sense of virtual space: the depth of a character (or “the psychological depth to which we have given the

20

R. STAGG

name ‘character’”49) is partly related to the depth of stress rhythm in the lines that they speak—such that when we hear a character talk a verse of incessant binary, of de-dum-de-dum, we tend to fnd them obvious. Metrical complexity can entail and inculcate other sorts of complexity. For example, when we make our way through one of Shakespeare’s verse lines we are often vibrating between what George T. Wright calls “the marked syllables of the meter [de-dum-de-dum], and the stressed syllables of the line [a more natural or speech-like stress]” (Wright is indebted to Halle and Keyser’s effort “to differentiate actual stressing from the abstract metrical scheme”).50 We sometimes bestow natural or speech stress on a syllable which the metre (in, as it were, offcial terms) downplays as unstressed. Conversely, the metre sometimes foists emphasis upon a syllable which might otherwise have gone unstressed (and unnoticed). As such, we sometimes feel in Shakespeare’s stresses and unstresses “less the immediacy of statement, and more the preventions that lurk just behind what is being spoken,” a metrical undertone, or what A. D. Nuttall called “undermeaning” and Constantin Stanislavski called “subtext […] the meaning lying underneath the text.”51

This is keenly the case in Hamlet (c.1601), a play of “corporeal inwardness”52 that is busily preoccupied with “The inward service of the mind and soul” (1.3.13). Characters in the drama dwell obsessively upon Hamlet’s interiority, and do so often in terms of depth. Claudius thinks about Hamlet’s “inward man” (2.2.6) and his “deep grief” (4.5.74), Polonius of what exists “Within the centre” of Hamlet (2.2.161). “There’s something in his soul,” reckons Claudius, “O’er which his melancholy sits” (3.1.167–68). For his own person, Hamlet speaks about his “heart’s core” (3.2.71) and his “lowest note” (355). He wants Gertrude to see her “inmost part” (3.4.20) and knows Claudius is deceiving him “as deep as to the lungs” (2.2.577). The play stages its own sorts of depth: the ghost crying from beneath the stage (1.5), the submerged and buried Ophelia (4.7), the gravediggers digging (5.1). Modern productions have laboured to represent Hamlet’s depth with physical space—in the case of Laurence Olivier’s 1948 flm, almost literally zooming in and out of Hamlet’s head. In 1964 Richard Burton’s Hamlet soliloquised entirely to himself, recessed within the proscenium arch of New York’s Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, whereas in the next year David Warner’s Hamlet moved to the lip of the Stratford stage and addressed the audience directly—these being dramaturgical manifestations of Hamlet’s psychological amplitude, employing the depth of the set to communicate the depth of the character (an older

21

2 HUMOURAL VERSIFICATION

R. STAGG

model of locus and platea exists behind the arras of these stagings).53 Yet, as Katherine Maus puts it, “inwardness as it becomes a concern in the theatre is always perforce inwardness displayed: an inwardness, in other words, that has already ceased to exist.”54

Like the humours, the play’s rhetoric of inwardness is strung on a vertical axis; this can help it make audible “the symptomological effects of the humors” as they reach the surface of the verse line.55 To take one example: at the end of 4.4 Hamlet pledges to “spur”—or let “occasions” spur—his otherwise “dull revenge” (31–32). His speech (omitted in the Folio text of the play) ends with a vow promising “fresh determination,” concluding “O, from this time forth/My thoughts be bloody or be nothing worth” (64–65).56 In Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 flm adaptation, the line became a yell of resolution as the camera zoomed out to reveal Fortinbras’ vast army massing in the distance. The flm’s complementarily swelling music suggests that Hamlet’s newfound bloodiness is a match for Fortinbras’ military clout even as what viewers see before their eyes might insist otherwise. If the speech can be a “striking climax,” it also has “a touch of the claptrap”; David Garrick was unconvinced by its ending, revising the fnal line of Hamlet’s speech to “My thoughts be bloody all! The hour is come” and then adding another: “I’ll fy my keepers—sweep to my revenge.”57 In most performances of 4.4.65, the frst major (or “primary”) stress of the line alights on “bloody” (with a much gentler stress on “thoughts,” this being a moment when an “apparently heavy beat surrenders its metrical precedence to other syllables elsewhere”).58 Such a voicing emphasises Hamlet’s offcial line, as it were, that his thoughts will be realised in blood and therefore, presumably, in action. Thoughts will turn into bloody deeds. Hamlet fgures his bloodiness, or bloody-mindedness, in terms of what Paster has called “Laudable Blood,” a blood awash with benignly energetic “vital spirits.”59 For Ambroise Paré, the royal barber surgeon, this blood “runs forth as it were by leaping, by reason of the vital spirit contained together within it.”60 However, if we exclusively hear the line’s metrical stresses a different Hamlet emerges—or rather, the tentative, vacillating Hamlet of critical legend. When reading only with the metre’s stresses in our ears, we fnd that emphasis settles not on Hamlet’s promise of action but (once again) on his thoughts: “My thoughts be bloody or be nothing worth.” Hamlet’s newfound conviction will manifest not (or not so much) in physical action, as we might crave by this late point in this long play, but in a “somatic consciousness,” a kind of deep humoral blood that is by contrast “sluggish” or “inanimate.”61 However humoral

22

Hamlet’s thoughts, on this stressing of the line they will scarce translate into deeds. If this is a prosodic slip on Hamlet’s part, like the Freudian parapraxis, it is a confession of his essential inertia, but it is also a humoural exudation or secretion of that which “lies hid” in Shakespeare, where the distinction between marked and stressed syllables can (paradoxically) give voice to impulses which are “not speakable at all.”62

How can an actor perform this moment, or any other moment in which the humoural versifcation of a text rises closer to the surface? Paster speculates that an actor “can offer the image of an affective and physical control so masterful as to quell, if only for a time, the inner turbulence of his own humorality.”63 The actor thereby manages to have a humour or humours “well within his affective command.”64 This would be near to what Erin Sullivan has called “emotive improvisation,” a happening in which the “radically conficting paradigms” governing or shaping the understanding of emotion in the period necessitate “a corresponding need” to clarify such emotions “through active and wilful interpretation,” an interpretation that could be a species of performed mastery.65 However, a humoural versifcation such as Hamlet’s could end up cueing the humours of the actor’s body quite independently of his volition, rather than allowing him to perform such humours with careful supervision or indeed pretence. The humours, after all, were “forces […] at once extremely powerful and actually or potentially beyond our control”; they were “always active, always escaping notice, always exceeding the domain of the will.”66 The same might justly be said for prosody, which through its subtle, insinuating rhythms “could control you without your knowledge.”67 A humoural versifcation could pose a challenge to an actor’s sense of agency: are these performed humours chosen by the actor or is the actor being acted upon by the verse’s humoural prosody (even if the verse’s “pre-articulate command” is “to act—now—in some defnitively undefned new way”68)? And where might this leave a reader or audience member, also exercised upon by the humoural energies of verse? Ultimately, after all, “[t]o be in one’s humor or out of it is not always in a man’s power to decide.”69

Notes

1. The phrase “cliché of rhythm” occurs in Steele, “Boundless Wealth,” 95.

2. Freeman and Taylor, “Why Shakespeare loved iambic pentameter.”

3. Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy, 334–37. See also Galen’s commentary on “The pulse for beginners,” Galen: Selected Works, 327.

4. Erickson, Language of the Heart, 15, 11.

23

2 HUMOURAL VERSIFICATION