Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

e-ISSN:2395-0056

p-ISSN:2395-0072

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

e-ISSN:2395-0056

p-ISSN:2395-0072

K. Lakachew Abitew1, Liu Tao, 2 Meiyan Xing 2 Menber Asmare

3

Birhanu Germa 3

1, 3 College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tongji University,1239 siping road, Shanghai 200092, China 2* College of Environmental Science and Engineering, Department of Environmental Science and Engineering.

This study examines the economic impact of urban parks in Ethiopia, focusing on carbon sequestration, property values, and revenue generation. The research surveyed 561 visitors, revealing that 95.88% have at least a high school education, with 65.05% holding some college education or higher. Analysis of six urban parks showed significant variations in their economic contributions. Entoto Park emerged as the highest revenue generator, contributing 42,224,000 in entrance fees, while Shegre Park generated the least at 1,816,000. The study found that properties near urban parks commanded a 20.8% price premium compared to those farther away. Carbon sequestration analysis of Gullele Botanical Garden (GBG) revealed a total carbon stock of 690,140.49075 tons, with 99.85% stored in biomass and 0.15% in soil the monetary value of this carbon stock calculated at USD 3,315,834.39. Job creation varied significantly among parks, with Entoto Park creating 1,442 jobs and Shegre Park only 57. The research also projected that over 99 years; the carbon stock value of GBG could increase to USD 8,879,276.15, surpassing its current land value of USD 8,151,548.73

Keywords: Carbon Sequestration, Urban Parks, Economic Impact, Land Value, Job Creation, Property Enhancement, Climate Mitigation

1.1.

The global rise in population has led to a substantial increaseintheurbanpopulation.In1960,only34%ofthe world’spopulationresidedincities,whereasby2022,this number had almost doubled to 57 %. The World Bank (2023) projects that this trend will continue, with an estimated urban population of 70 % by 2050 [1]. The European Union has already reached this level, as evidencedbythefactthat75%ofitspopulationresidedin urbanizedareasin2022[1].Urbanizationisamajordriver ofsocio-economicchangesthatnotonlyaffectlandusebut also have additional impacts on multiple layers of the

In the rapidly urbanizing landscape of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the role of green spaces and urban parks is undergoing a profound reevaluation. Once viewed International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET)

Earth’s surface, significantly affecting urban core zones (UCZs)[2] Urbanization is a major catalyst for land use change worldwide, accelerating the expansion of impermeable surfaces and causing catastrophic loss of natural and agricultural lands [3]. This rapid urbanization trend has numerous negative consequences for the environment. Urban green spaces like parks, forests, and wetlands play a crucial role in mitigating climate change by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide. However, the loss of these areas diminishes their capacity to sequester carbon, exacerbating global warming. Research indicates that urban trees are particularly effective carbon sinks, withstoragecapacitiesvaryingfrom25to400metrictons per hectare. As these natural carbon capture systems disappear,theEarth'sabilitytocounteractgreenhousegas emissionssignificantlyreduced[4].Greenspacesarebeing marketed as efficient urban cooling solutions as cities struggle with the growing problems of urban heat and its effectsonvulnerablegroups,especiallyelderlyindividuals [5]. Their absence has negative impacts on human health and energy consumption, especially during heat waves, duetorisingtemperatures.Studieshaveshownthaturban heat island effects can increase temperatures by several degrees Celsius, leading to increased heat-related deaths and illnesses [6]. Green spaces play a vital role in maintaininghealthyandresilientecosystemsbyproviding habitat for a variety of plants and animals [7]. Their loss leadstolossofbiodiversity,disruptionoffoodchains,and potentiallyimpactsfoodsecurityandresourceavailability. The Convention on Biological Diversity estimates that urban sprawl is the leading cause of biodiversity loss worldwide [8]. City dwellers rely on green spaces forrelaxation,exercise,andstressrelief.Theirabsencecan have a significant impact on mental and physical wellbeing,leadingtoincreasedhealthcarecostsandreducedqu ality of life. Studies have shown thathavinggreen spacesimprovesmental health,reducesstress levels, andincreasesphysicalactivitylevels[9]

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

primarily through the lens of recreation and aesthetics, these verdant pockets within the city now recognized for their substantial economic contributions, particularly in termsoftheirimpactonpropertyvaluesandtheircapacity for carbon storage. This shift in perspective is not only reshaping urban planning strategies but also offering innovative solutions to the dual challenges of economic development and environmental sustainability faced by many developing cities. The economic benefits of urban parks in are most immediately evident in the real estate market. Properties in close proximity to well-maintained green spaces observed to command higher prices, a trend that mirrors findings from cities around the world[10].Thispricepremiumnotonlybenefitsindividual homeownersbutalsocontributestothecity'sfiscalhealth through increased property tax revenues. In a city where land is at a premium and development pressures are intense, the ability of parks to generate economic value provides a powerful counterargument to those who view green spaces as unproductive land use. Beyond their impact on property values, the urban forests of Addis Ababa serve ascrucial carbonsinks,playinga vital role in the city's efforts to combat climate change. Recent studies have revealed that the carbon sequestration potential of urban green areas is remarkably high, with some forests demonstrating carbon storage capacities that exceed global averages for urban areas [11].This ecological service not only contributes to Ethiopia's national climate actiongoalsbutalsopositionsAddisAbabaasamodelfor sustainable urban development in Africa. The intersection of these two economic benefits enhanced land values and carbon storage creates a compelling narrative for the preservationandexpansionofurbangreenspacesinAddis Ababa. As the city continues to grow and evolve, policymakers and urban planners are increasingly recognizing that investments in parks and green areas yield multifaceted returns. By quantifying these benefits, stakeholders more informed decisions about land use, balancing the immediate pressures of urban development with the long-term goals of creating a livable, sustainable city

1.2.

1.2.1. Ecosystem Services

Urban green spaces play a vital role in improving the quality of life in cities and provide a range of benefits to residents. They serve as natural sanctuaries in the concrete landscape of urban environments and provide a tranquil refuge from the fast-paced urban lifestyle [12]. Urban trees make a significant contribution to Goal 3 of sustainabledevelopmentrelatedtopromotinggoodhealth

and well-being, Goal 11 focused on creating sustainable cities and communities, and Goal 13 centered on taking actiontocombatclimatechange(Unitedations,2015)[13]. This contribution stems from their ability to generate a multitudeofecosystemservices.Urbangreenspaces,such as parks and forests, are crucial for addressing environmental challenges in cities. These areas help regulate climate by providing shade and releasing moisture through evapotranspiration, resulting in cooler temperatures. Additionally, they enhance air quality, makingthemanessentialcomponentofsustainableurban ecosystems and overall environmental health [14]. Urban green spaces promote outdoor activities, improve safety, and strengthen social ties between neighbors, reducing social disorder, anxiety, and depression. These areas help alleviate mental fatigue and stress [15] Trees and shrubs can effectively act as sound barriers, reducing noise pollution. When space allows, thick vegetation strips combined with landforms or solid barriers can decrease highway noise by 6 to 15 decibels [16] Park users visit these spaces for fresh air, stress relief, relaxation, and social interaction. The absence of noise and improved air quality in green spaces contribute to users' relaxation in both small and large areas [17]. Urban parks serve as critical ecological sanctuaries, offering essential habitats thatsupportdiversewildlifepopulationsandcontributeto maintaining biodiversity within city environments [18]. Improved public health: Park access encourages physical activity, reduces stress, and promotes mental well-being [19]

Urban parks significantly enhance property values, offering both direct and indirect economic advantages to nearby areas [20]. These green spaces improve neighborhood aesthetics, making them more appealing to potential homebuyers. Properties close to parks often see valueincreasesofupto20%,astheyproviderecreational opportunities, scenic views, and healthier environments. Additionally, parks attract businesses and tourism, stimulating local economies [21]. They also promote physical activity and mental well-being, which can further elevate property values by fostering a healthier community. Thus, investing in urban parks not only improves quality of life but also yields substantial returns forpropertyownersandurbanplanners.Parksandpublic gardens provide a welcome opportunity to ‘escape’ from urban life, delivering a wide range of so-called landscape services (Termorshuizen & Opdam, 2009; Vallés-Planells et al., 2014) that include recreation opportunities and aestheticviews[22]

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

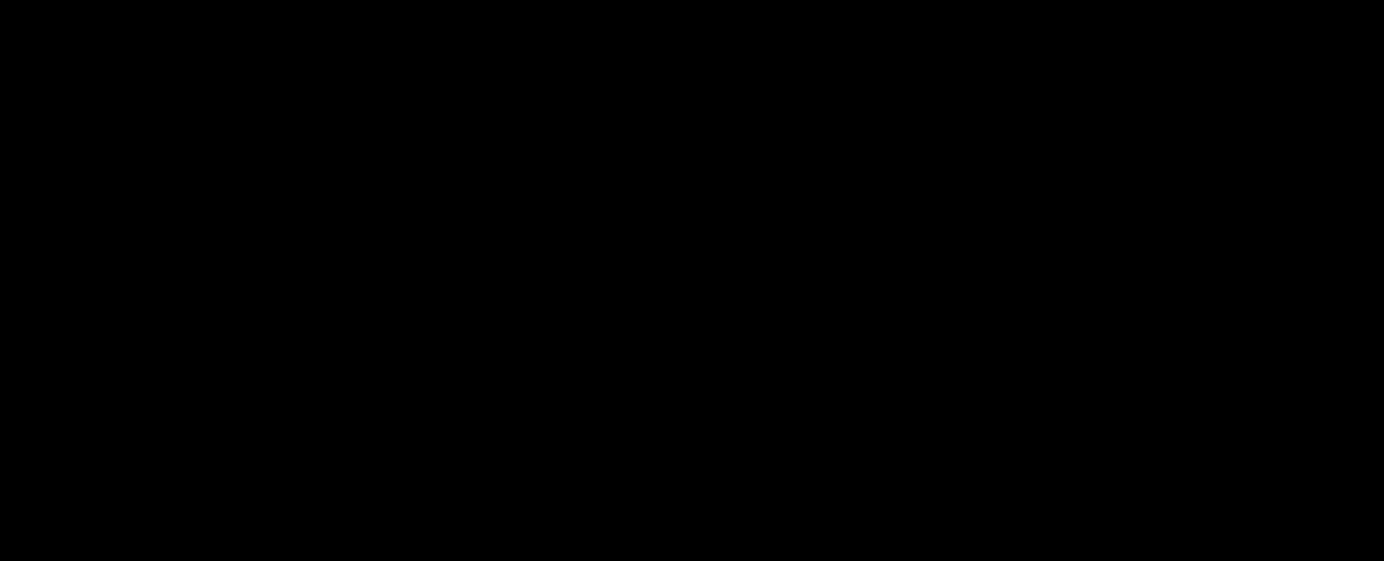

2.1. Study Area: -

The research conducted within Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, thenation'scapitalandaburgeoningmetropolisexceeding 4.7 million inhabitants. Situated at an elevation of 2,355 metersintheEthiopiancentralhighlands,AddisAbabahas

undergone rapidurbanizationin recent decades, resulting in a significant decline in urban green spaces. This study specifically focuses on Green Spaces and Property Prices: TheEconomicBenefitsofUrbanParksthroughLandValue and Carbon Storage" in Addis Ababa , primarily in the centralandinnercityareas.

2.2.1. Visitor surveys in six parks

The six parks chosen with purposive selection, guaranteeing a varied representation of park kinds and visitor experiences. The method used to gather information for visitor surveys in Friendship, Kentiba, Shegre, and Future, Entoto, and Beheretsige six parks specifically chosen. Create a standardized survey that addressesthemostimportanteconomicfactors.Toensure unpredictability, choose participants via systematic random sampling, approaching each nth visitor. One hundred surveys distributedto eachpark forguests to fill out. At several points in each park, including entrances, well-known attractions, and rest spots, trained surveyors will approach guests. To gather a wide variety of visitors, surveyscarriedoutonweekdaysandweekends,aswellas atvarioustimesoftheday. Thequestionnairelikelycover topics such as Visitor demographics, Trip characteristics, Activities undertaken in the park, Visitor satisfaction and experiences,Suggestionsforimprovement

2.2.2. Land value assessment of one park

UsedComparativeProperty Method(COMP Method):This methodcomparesthesubjectpropertytosimilar,recently sold properties that have undergone similar conversions. The value is adjusted based on characteristics such as location,condition,utilityaccess,andcurrentzoning

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072 © 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008

2.2.3. Carbon stock measurement and valuation

Measurementofcarbonstocksinsoilandforests requires aboveground biomass, Tree dimensions sampled in the fieldusingallometricequations.Usingroot-to-shootratios derivedfromabovegroundbiomass,belowgroundbiomass estimated. Soil carbon, Laboratory analysis and sampling of soil cores. Using the proper carbon fractions, carbon computedbyconvertingbiomasstocarbon.Carbonstocks are usually valued by monetizing them using marketpricingcostofcarbon.

2.2.4. Park entrance fee

Data obtained directly from the administrative office's managementteamsofthesevenselectedparks.

2.2.5. Real estate value comparison near and far from parks

Select ten residential properties for analysis: five located within0.5km of majorurbanparks(near properties)and fivemorethan1.5kmaway(farproperties).Allproperties chosen to have similar characteristics, such as size and type,ensuringcomparablevalueper/m2.

2.3. Techniques for Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics like means, percentages, and frequencies used to examine the visitor survey data from six parks to compile information about visitor demographics, attitudes, and usage trends. Visitors' characteristics and park impressions compared using chi-

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

square tests, and visitor satisfaction compared across parks using a one-way ANOVA and Origin for graphical analysis.

ThecomparativepropertymethodevaluatedGBGPark's land worth by contrasting recent sales information of neighboring properties. Using soil sampling and standard allometric equations, the carbon stock in forest biomass

3.1.

A survey of five hundred sixty one visitors revealed that the majority (95.88%) have at least a high school education,with65.05%holdingsomecollegeeducationor higher. The largest group (38.14%) comprised visitors with some college education, followed by high school graduates (30.83%) and college graduates (24.42%). Postgraduates were the smallest group, at 2.49%, while only4%ofvisitorshadlessthanahighschooleducation.

p-ISSN:2395-0072

and soil is measured, and its value is determined using carbon market prices. Descriptive techniques used to examineentrancefeedatafromsevenparksincludingGBG Park in order to identify income trends. Paired sample ttests used to assess differences in property values per squarebetweenpropertiesclosetoandfarfromparks.

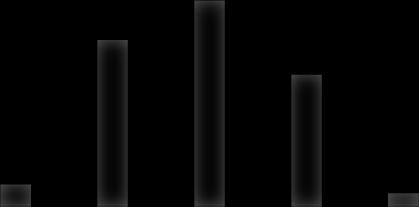

The survey findings in the overall economic impact of parks highlight a predominantly educated audience, with significant representation at the college and high school levels.Themajorityofresponders(morethan93%)agree orstronglyagreethatEntoto,Beheretsige,andFriendship Parks have a considerable economic impact. With 95% of thevote,EntotoParkhasthemostpositiverating,followed by Beheretsige (93%) and Friendship (94%), all of which show broad agreement about their financial advantages and little dissent. In comparison to the top three parks, Kentiba Park hasstrong but somewhatlowerperceptions, scoring 89% of the responses favorably. Shegre Park, on theotherhand,hasthelowestperception,withjust72%of respondents expressing a favorable opinion and the greatest levels of dissent (13% disagreement and 8% extreme disagreement), suggesting a significant degree of skepticism. Though it lags behind the top parks, Future Park has a moderately good 82% rating, indicating room for development. Although the majority of parks have a positive economic impact on the community, the results showthatspecificmeasurestoimproveShegreandFuture Parks could increase their economic impact and communityperception

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

Table- 1: Land value assessment data

Source: -Gullele subcity Land management office, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

3.3. Carbon Stock and Economic Value

3.3.1.Soil Carbon Stocks

The total carbon stock of the park has been assessed by calculating both biomass and soil carbon contributions. For soil carbon, calculations performed at three depths: 10cm,20cm,and30cm.Theformulausedincorporatessoil carbon content, bulk density, and depth, converting these

into tons of carbon perhectare.Resultsshow thatthesoil carbonstockfor10cm,20cm,and30cmdepthsis0.54945 t/ha,0.42525t/ha,and0.52245t/ha,respectively,leading to a total soil carbon stock of 1.49715 t/ha. Given the park's area of 705 hectares, the total soil carbon stock acrosstheentireparkcalculatedat1,055.49075tons.

Ph.Result%

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

3.3.2. Above ground biomass(AGB) & Below ground biomass( BGB) carbo stock

Finally, the total carbon stock of the forest calculated by adding the AGB and BGB. The carbon content of AGB and BGB was obtained by multiplying the biomass value by

47% [23]. The 47% is usually used because it was recommended by IPCC guidelines chapter 2 indicates it. The carbon stock changed into a monitory value by using theformula:

Monetary value (USD) = Carbon stock (tons/hectare) * Area(hectares)*CarbonPrice(USD/tonCO2equivalent).

Table- 3: AGBand BGBcarbonstock.

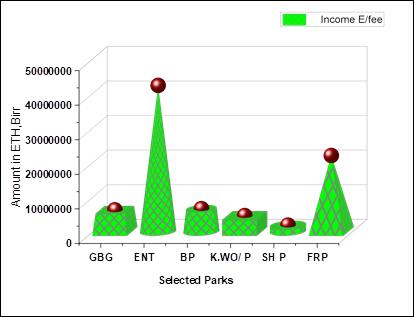

3.4. Park Revenue from Entrance Fees

The Income Contribution Index (ICI) reveals significant disparities in revenue generation among urban parks. Entoto Park stands out as the highest contributor, generating 42,224,000, followed by Friendship Park with 21,938,400. Beheretsige Park (6,579,980) and GBG (6,232,572) show moderate contributions, while K. WO/P (4,569,362) reflects a smaller but notable economic impact. These parks demonstrate the importance of strategic development and popularity in driving revenue. On the other hand, Shegre Park has the lowest ICI fee at 1,816,000, indicating minimal economic contribution. FuturePark,privatelyowned,doesnotchargeanentrance fee.

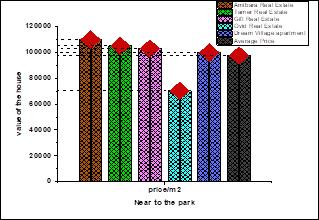

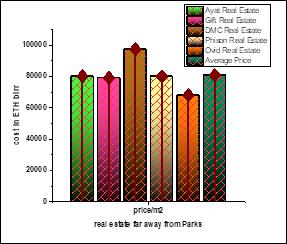

3.5. Real Estate Value Comparison

When comparing real estate prices near and far from urban parks, properties near urban parks show a significant premium. The price for properties near urban parksrangesfrom70,361ETHBirrpersquaremeter(Ovid Real Estate) to 110,000 ETH Birr per square meter (Amibara Real Estate). The average price in this group is 97,672 ETH Birr, which is 20.8% higher than the average price of properties located farther from urban parks, which stands at 80,819 ETH Birr. Simultaneous with introducing green infrastructure, brownfield land is experiencing some of the greatest and most rapid land cover changes in many post-industrial cities (Wong and Schulze Bäing, 2010)[24]. Outlines how official, City land value data utilized to assess the economic value of parkland.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

4.1.1. Parks contribute local economies

According to the Ministry of Commerce, as reported on December 28, 2023, China's 230 national economic development zones achieved a GDP of 14 trillion yuan (approximately 1.97 trillion U.S. dollars) in 2022[25]. The Income Contribution Index (ICI) reveals significant disparities in revenue generation among urban parks. Entoto Park stands out as the highest contributor, generating 42,224,000, followed by Friendship Park with 21,938,400. Beheretsige Park (6,579,980) and GBG (6,232,572) show moderate contributions, while K. WO/P (4,569,362) reflects a smaller but notable economic

Fig- 4: entrance fee ofparks

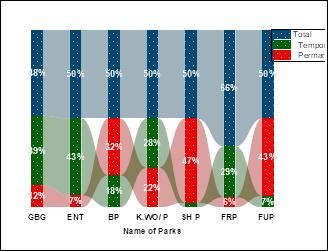

4.1.2. Urban parks contribute to the creation of job opportunities in the community. The job creation data across various parks shows significant variation in employment opportunities, with someparkscontributingnotablymorethanothers.Entoto Park stands out as the largest job creator, with 1,442 positions, of which 1,246 are temporary and 196 are permanent. This reflects the park’s capacity to provide both short-term and long-term employment, likely due to its popularity and the scale of its operations. Friendship Park (FRP) follows with 744 total jobs, including 325 temporary positions and 65 permanent jobs, demonstrating its strong role in local employment, particularlyintemporaryroles.

On the other hand, parks like Shegre Park (SH P) and Kentiba wo/Tsadqepark,(K.WO/P) showrelativelylower job creation, with only 57 and 47 total positions, respectively. Shegre Park offers a small number of permanent (54) and temporary (3) roles, while K.WO/P provides 21 permanent and 26 temporary jobs. Beheretsige Park (BP) also has fewer employment opportunities, with 160 total jobs, 102 of which are

p-ISSN:2395-0072

impact. These parks demonstrate the importance of strategicdevelopmentandpopularityindrivingrevenue. On the other hand, Shegre Park has the lowest income contribution index (ICI) fee at 1,816,000, indicating minimal economic contribution. Future Park, privately owned,doesnotchargeanentrancefee,insteadleveraging freeaccesstoattractmorevisitors.inthiscasetheparkhas 900 customers average a day. While this approach may boost visitation, it limits direct revenue generation. Overall, Entoto and Friendship Parks emerge as major economicdrivers,whileparkslikeShegreandFuturePark highlight the need for innovative strategies to balance accessibility with financial sustainability. The factors that motivated greenspace users to access a greenspace were notidenticaltothebenefitstheyderived[26]

permanent.ThisdatasuggeststhatwhileparkslikeEntoto andFriendshiphavealargereconomicimpactthroughjob creation, others may need further development or strategic planning to boost employment outcomes. The value obtained from ecosystems services divided into threetypesuse,option,andnon-usevalues.Thesumofall thesevaluescalledtheTotalEconomicValue(TEV)[27].

Fig-

Urban green infrastructure serves as an effective strategy for microscale, mesoscale, and even macroscale climate change mitigation and adaptation because vegetation can capture and securely store carbon through biotic sequestration[28] Across various strata, the data highlights significant Above Ground Biomass (AGB) and Below Ground Biomass (BGB), with the Eucalyptus woodlandstratacontributingthemost.205,674.62kg.AGE and 41,134.92 kg BGB. This reflects the high carbon storage potential of dense woodland areas, underscoring theirecologicalimportance.Otherstrata,suchaslow-and mid-altitude areas, also demonstrate substantial

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

contributions, collectively accounting for significant carbonsequestrationwithinurbanlandscapes.

High-altitude and recreational area strata, though smaller in tree density and biomass, still contribute meaningfully to overall carbon storage. Recreational areas, with 351 trees, store 61,210.15 kg AGE and 12,242.03 kg BGB, demonstrating that even parks with a primary focus on leisure can serve as carbon sinks. Urban parks have a

Sincethecarbon,marketandtraditional financial markets share many traits, numerous financial market models, used to characterize the carbon market[31] The total carbonstock ofthepark calculatedbycombiningbiomass and soil carbon storage. Biomass carbon accounts for 689,084.52 tons, while soil carbon, calculated using soil carbon content, bulk density, and depth across 10cm, 20cm, and 30cm, totals 1,055.49075 tons. Together, the park's carbon stock amounts to 690,140.49075 tons, with the majority (99.85%) stored in biomass and a smaller portion (0.15%) in soil. These findings underscore the park's significant role in carbon sequestration, primarily throughitsvegetation,withsoilcontributingasmalleryet importantsharetotheoverallcarbonstorage Finally,the carbon stock changed into a monitory value by using the formula:

Monetary value (USD) = Carbon stock (tons/hectare) * Area (hectares) * Carbon Price (USD/ton CO2 equivalent) According to the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) report, the average global carbon market price in 2023 varied throughout the year[32]. The average prices for 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024 are $47–50, $75–$85, $85–$90, and $90-$100, respectively. However, for safety, the lowest price of $85 per ton of CO2 equivalent used in this study. Monetary value (USD) = (51.6226(t/ha) + 1.49715 (t/ha)) * 705ha *85USD/ton CO2 equivalent = 3,183,201.01875USD.Thisamount ofcarbon dioxidesunk into the plants and the soil from the atmosphere into whichcarsandindustriesreleasethegas.

4.1.5. Economic Importance of Parks and Longterm Carbon Value.

Quantified emissions and sinks in forest ecosystems and climatechangeinthe WesternGhatswereusedina study on carbon budgeting. This will help develop appropriate mitigation strategies to reduce the effects of global warming and promote sustainable forest management. According to Sun et al. (2020), the forest area's overall storage and sequestration value would reach US$9,775 million by the end of 2050[33] This analysis underscores how parks like GBG provide substantial long-term economic benefits through carbon sequestration. Beyond their immediate monetary worth, they contribute to climate mitigation and ecological balance, offering a compelling case for conservation-focused land

higher degree of variation in carbon sequestration (CS) than forest carbon sinks, and their carbon sink mechanisms are comparatively more intricate[29]. This dual function highlights urban parks' ability to balance ecological contributions with recreational purposes, making them valuable in mitigating urban carbon emissionsandimprovingairquality[30].

management strategies. The economic analysis of GBG's 707-hectarearea highlights thelong-termvalueofnatural parks, considering both land value and carbon sequestrationpotential.

4.1.5.1. Current Land and Carbon Values

LandValue:-Thecurrentrealestatemarketvalue fora99-yearleaseofGBG'slandestimatedatUSD 8,151,548.73

CarbonMarketValue:-

From entrance fees in 2023:USD 49,860.57

From soil and forest carbon stock (excluding leaf and dead wood):USD 3,315,834.39

Totalinitialcarbonstockvalue:USD3,365,694.96

4.1.5.2. Projected Carbon Sequestration Value

Assuming a conservative1% annual increase in carbon stock, the future value of carbon sequestration over 99 yearsiscalculated

FutureValue=3,365,694.96 x (1.01)99 = 8,879,276.15 USD FutureValue=3,365,694.96×(1.01)99=8,879,276.15USD. Thisprojectionindicatesthatthecarbonstockvaluecould morethandoubleoverthenextcentury.

4.1.5.3. Comparison of Economic Values

CurrentLandValue:$8,151,548.73USD.

Projected Carbon Stock Value (after 99 years):$8,879,276.15USD.

The projected carbon stock value surpasses the current land value, emphasizing the long-term economic importance of preserving GBG's natural ecosystem.

4.2. Property Value Enhancement

This indicates a clear market preference for the added benefitsofproximitytogreenspaces.

In the group of properties located farther from urban parks, the pricing is more moderate, ranging from 67,907.13 ETH Birr (Ovid Real Estate) to 97,246 ETH Birr (DMCRealEstate).Theaveragepriceofthesepropertiesis 80,819 ETH Birr. Among the listed developers, Ayat Real Estate,GiftRealEstate,andPhisonHomes’sRealEstate,all have similar prices of around 79,000 ETH Birr. These properties reflect reduced perceived value from being locatedfurtherfromurbanparks.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net

The comparison in percentage terms shows that propertiesnearurbanparksgenerallypricedabout20.8% higheronaveragecomparedtothoselocatedfartheraway. Thispremiumhighlightstheaddedthatproximitytourban parks provides in terms of desirability and potential benefits to residents, including better access to green spaces and a more pleasant living environment. While the price variation within each group exists, the overarching trend remains clear: urban park-adjacent properties commandasignificantpricepremium.

The presence of parks significantly enhances neighborhood property values, as reflected in varying levels of positive perceptions across six parks. Friendship Park enjoys one of the highest positive ratings, with 90% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with its impactonpropertyvalues. Similarly,KentibaPark follows closely with 85% positive responses, emphasizing its strongcontributiontopropertyvalueappreciation.Future Park, while moderately perceived, achieves 76% positive responses, indicating potential for improvement in its perceived value. Shegre Park, with 70% positive perception and higher neutral (12%) and disagreement (18%)responses,reflectsacomparativelyweakerimpact. Entoto Park and Beheretsige Park stand out as top contributors to property value enhancement. Entoto Park garners 93% positive responses, while Beheretsige Park achieves the highest rating with 94% agreement, indicating strong consensus on their significant neighborhood impact. Overall, the findings emphasize the critical role of urban parks in increasing property values. In urban settings, differences in land prices are indicative ofthelocationalandgeographicalbenefitsofspecificsites, alongside local external factors and government policies that govern land use. Regulations surrounding land use in cities play a vital role in shaping urban forms, influencing the spatial distribution of development and occupancy, as well as affecting residents' housing and transportation expensesandtheiroveralleconomicwell-being[34].

p-ISSN:2395-0072

Urban parks offer significant economic benefits through their contribution to local economies, job creation, and carbon sequestration. For example, Entoto Park generates substantial revenue of 42,224,000, while also providing 1,442 jobs. Gullele Botanic Garden (GBG) has a carbon stock valued at $3,183,201.02 USD, which could increase by 1% annually, potentially reaching $8,879,276.15 USD over 99 years, surpassing its current land value. This highlights the long-term economic benefits of preserving and managing green spaces for their carbon storage capabilities.

The carbon sequestration value of urban parks is a powerful argument for conservation efforts. GBG’s projected future carbon value significantly outpaces its current land value, reinforcing the idea that ecological

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

preservation can have substantial financial returns. In addition to environmental benefits, urban parks play a critical role in enhancing property values, with properties neargreenspacestypicallypriced20.8%higherthanthose farther away. This illustrates the economic value of green spaces in increasing real estate attractiveness and contributingtooverallurbanlivability.

First,praiseGod,thesonoftheHolyVirginMary.

I sincerely thank my professors, Liu Tao, and Meiyan Xing, for their unwavering support, guidance, and encouragement throughout my journey.

I thank you too much next to God, for everything, youhave done for my SweetheartEmbet Tesfaw, and dear brother and sister, Misganew Abitew, Mehari Meskelo, Aselfe Lulu. Armiyas Mehari, TezazuZelekeandGizawAshenafi.

Reference

[1] S. Bahr, "The relationship between urban greenery, mixed land use and life satisfaction: An examination using remote sensing data and deep learning," Landscape and Urban Planning, vol.251, p. 105174, 2024/11/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2024.1051 74.

[2] P. Yu, Y. Wei, L. Ma, B. Wang, E. H. K. Yung, and Y. Chen, "Urbanization and the urban critical zone," Earth Critical Zone, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 100011, 2024/06/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecz.2024.100011.

[3] B. Wu et al., "Urbanization promotes carbon storage or not? The evidence during the rapid process of China," Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 359, p. 121061, 2024/05/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121061

[4] B. F. Nero, D. Callo-Concha, A. Anning, and M. Denich, "Urban Green Spaces Enhance Climate Change Mitigation in Cities of the Global South: TheCaseofKumasi,Ghana," Procedia Engineering, vol. 198, pp. 69-83, 2017/01/01/ 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.07.074

[5] L.Vasconcelos, J.Langemeyer, H. V.S. Cole, and F Baró, "Nature-based climate shelters? Exploring urban green spaces as cooling solutions for older adultsina warmingcity," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 98, p. 128408, 2024/08/01/ 2024, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128408

[6] P. K. Diem et al., "Remote sensing for urban heat island research: Progress, current issues, and

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072 © 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page189

Based on these findings, it recommended that city planners invest in the development of urban parks, prioritizetheirlong-termconservation,andintegratethem intourbanplanningstrategies.Policiesshoulddesignedto incentivize the economic and environmental benefits of these parks, fostering both job creation and sustainable development while enhancing the quality of life in urban areas.

perspectives," Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, vol. 33, p. 101081, 2024/01/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsase.2023.101081.

[7] P. Biella et al., "Biodiversity-friendly practices to support urban nature across ecosystem levels in green areas at different scales," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, p. 128682, 2025/01/22/ 2025, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2025.128682

[8] A. Pfenning-Butterworth et al., "Interconnecting global threats: climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases," The Lancet Planetary Health, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. e270-e283, 2024/04/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S25425196(24)00021-4.

[9] A. A. Tehrani et al., "Predicting urban Heat Island in European cities: A comparative study of GRU, DNN,andANNmodelsusingurbanmorphological variables," Urban Climate, vol. 56, p. 102061, 2024/07/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2024.102061.

[10] W.Zong,L.Qin,S.Jiao,H.Chen,andR.Zhang,"An innovative approach for equitable urban green space allocation through population demand and accessibility modeling," Ecological Indicators, vol. 160, p. 111861, 2024/03/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111861

[11] M. Queißer, M. Burton, and R. Kazahaya, "Insights intogeologicalprocesseswithCO2remotesensing –Areviewoftechnologyandapplications," EarthScience Reviews, vol. 188, pp. 389-426, 2019/01/01/ 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.11.016

[12] P. Odhengo, A. I. Lutta, P. Osano, and R. Opiyo, "Urbangreenspacesinrapidlyurbanizingcities:A socio-economic valuation of Nairobi City, Kenya," Cities, vol. 155, p. 105430, 2024/12/01/ 2024, doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105430

[13] Y. Yousofpour, L. Abolhassani, S. Hirabayashi, D. Burgess, M. Sabouhi Sabouni, and M. Daneshvarkakhki, "Ecosystem services and economic values provided by urban park trees in the air polluted city of Mashhad," Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 101, p. 105110,

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

2024/02/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.105110.

[14] S. Arzberger, M. Egerer, M. Suda, and P. Annighöfer, "Thermal regulation potential of urban green spaces in a changing climate: Winter insights," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 100, p. 128488, 2024/10/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128488.

[15] J. Zhao, F. A. Aziz, and N. Ujang, "Factors influencing the usage, restrictions, accessibility, and preference of urban neighborhood parks - A review of the empirical evidence," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 100, p. 128473, 2024/10/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128473

[16] J. P. Arenas, "Potential problems with environmental sound barriers when used in mitigating surface transportation noise," Science of The Total Environment, vol. 405, no. 1, pp. 173179, 2008/11/01/ 2008, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.049

[17] N.AbdeenandT.Rafaat,"Assessingverticalgreen wallsforindoorcorridorsineducationalbuildings and its impact outdoor: A field study at the universities of Canada in Egypt," Results in Engineering, vol. 21, p. 101838, 2024/03/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101838.

[18] O. Dondina et al., "Spatial and habitat determinants of small-mammal biodiversity in urban green areas: Lessons for nature-based solutions," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 104, p. 128641, 2025/02/01/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128641

[19] M. Cardinali, M. A. Beenackers, A. van Timmeren, and U. Pottgiesser, "The relation between proximitytoandcharacteristicsofgreenspacesto physical activity and health: A multi-dimensional sensitivity analysis in four European cities," Environmental Research, vol. 241, p. 117605, 2024/01/15/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.117605

[20] J. Chen et al., "Actual supply-demand of the urban green space in a populous and highly developed city: Evidence based on mobile signal data in Guangzhou," Ecological Indicators, vol. 169, p. 112839, 2024/12/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112839.

[21] G.Chrobak et al.,"GraphEnhancedCo-Occurrence: Deepdiveintourbanparksoundscape," Ecological Indicators, vol. 165, p. 112172, 2024/08/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112172.

[22] Y.Ma,E.Koomen,J.Rouwendal,andZ.Wang,"The increasing value of urban parks in a growing metropole," Cities, vol. 147, p. 104794, 2024/04/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.104794

[23] I. I. P. o. C. C. , " Guidelines for the national greenhouse gas inventories. Chapter 2: Forest land.," Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change),2006.

[24] C.Wong,"Aframeworkfor‘CityProsperityIndex’: Linking indicators, analysis and policy," Habitat International, vol.45,pp.3-9,2015/01/01/2015, doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.06.018

[25] D.YangandW.Luan,"Spatial-temporalpatternsof urban land use efficiency in china’s national specialeconomicparks," Ecological Indicators, vol. 163, p. 111959, 2024/06/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111959.

[26] M. Oviedo, M. Drescher, and J. Dean, "Urban greenspace access, uses, and values: A case study ofuserperceptionsinmetropolitanravineparks," Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, vol. 70, p. 127522, 2022/04/01/ 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127522

[27] T. M. Silva, S. Silva, and A. Carvalho, "Economic valuation of urban parks with historical importance: The case of Quinta do Castelo, Portugal," Land Use Policy, vol. 115, p. 106042, 2022/04/01/ 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.10604 2

[28] W.Y.Chen,"Theroleofurbangreeninfrastructure inoffsettingcarbonemissionsin35majorChinese cities: A nationwide estimate," Cities, vol. 44, pp. 112-120, 2015/04/01/ 2015, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.01.005.

[29] D.Zhao,J.Cai,S.Shen,Q.Liu,andY.Lan,"Naturebased solutions: Assessing the carbon sink potential and influencing factors of urban park plant communities in the temperate monsoon climate zone," Science of The Total Environment, vol. 950, p. 175347, 2024/11/10/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175347.

[30] B. Choudhary, V. Dhar, and A. S. Pawase, "Blue carbon and the role of mangroves in carbon sequestration:Itsmechanisms,estimation,human impacts and conservation strategies for economic incentives," Journal of Sea Research, vol. 199, p. 102504, 2024/06/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2024.102504

[31] N. Wang, Q. Wang, and Y. Li, "Estimation and forecast of carbon emission market volatility

© 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal | Page190

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 02 | Feb 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

based on model averaging method," Economic Modelling, vol. 143, p. 106976, 2025/02/01/ 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2024.106976

[32] I. Frankovic and B. Kolb, "The role of emission disclosure for the low-carbon transition," European Economic Review, vol. 167, p. 104792, 2024/08/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2024.1047 92

[33] W.Ma,S.Hou,W.Su,T.Mao,X.Wang,andT.Liang, "Estimationofcarbonstockandeconomicvalueof Sanjiangyuan National Park, China," Ecological Indicators, vol. 169, p. 112856, 2024/12/01/ 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112856

[34] N.Kok,P.Monkkonen,andJ.M.Quigley,"Landuse regulationsand the valueof landandhousing:An intra-metropolitan analysis," Journal of Urban Economics, vol. 81, pp. 136-148, 2014/05/01/ 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2014.03.004.

© 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008