International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Kazi Samina Shamsi Huq

M.Sc., Urban Management and Development (IHS, Erasmus University Rotterdam), Netherlands

Abstract – The urban housing landscape in Bangladesh is evolving rapidly, driven by factors such as urbanization, migration, andeconomic growth. However, disparitiespersist in terms of housing quality and spatial opportunities, particularly with women often facing unique barriers. In Dhaka’s low-income housing areas, inadequate socio-spatial planning often deepens social fragmentation At the same time, it highlights how the differential use of space by gender shapes community bonds and the capacity to cultivate social capital. For women, in particular, the absence of adequate social spaces in these settings exacerbates their marginalization, restricting their opportunities to build networks and access vital social support. Despite the recognized significance of social capital in urban sociology and planning studies, limited research has examined how shared social spaces in housing environments specifically influence women's social capital formation in Dhaka. This paper addresses this gap by exploring the intersection of gender and social capital in Dhaka’ s low-income housing. By using the World Bank’s social capital measurement frameworkandqualitative methods, thefindings identifythat women ’s access to such social spaces significantly influences socialcapitalformation andmutualsupport.Hence,thepaper underlines the essential part of gender in shaping social capitaldynamicsandadvocatesforgender-responsivehousing spatial planning to address women’s specific challenges and unique spatial needs in low-income contexts.

KeyWords: Gender,SocialCapital,Spatialexperience,Social Space,Low-incomehousing

1.

Theassociationbetweenspaceandgenderisbothsocially and,tosomeextent,culturallyconstructed,oftenshapedby societalexpectations,genderroles,andpatternsofspatial usage.Thesedynamicsinfluencethedifferentdemographic group's interactions and interpretations of spaces, which significantlyimpactbothindividualexperiencesandsocietal relationships Inthecontextofurbanhousing,evenwithin the same physical spaces, these dynamics result in varied rolesandparticipationsfordifferentgroups Besides,social capitalwhichischaracterizedbynetworksandconnections, supports communal well-being, it is essential for creating unified communities and encouraging constructive civic outcomes[1].

Nevertheless,thegenderaspectsofsocialcapitalalongwith itsdevelopmentsandmanifestationsareoftendisregarded. [2]. This oversight is especially crucial in Dhaka’s lowincome neighborhoods, where women’ s vulnerabilities persistduetounequaldistributionsofdomesticchoresand caregivingduties Additionally,theseareintensifiedbythe culturalnormsthatfrequentlylimittheiraccesstothepublic sphere. These limitations hinder their capacity to interact with others, participate in collective events, and develop socialcapitalingeneral.InDhaka’sdenselypopulatedurban fabricwherehousingconditionsoftenincludesubstandard living units and limited social spaces. These social spaces such as front or backyards, alleys, common fields, or communal facilities serve as vital sites for daily communicationsandrelationshipbuilding.Inthesesettings, social capital is not only confined to traditional kinship networks but also extends localized, socially bound connections, particularly among women. Furthermore, substandard living conditions are frequently cited by researchersasasignificantparameterwhichcontributesto weakersocietaltiesandreducedsocialcapital[3]

However,spatialpracticeasdefinedby[4]Lefebvre(1991), highlights how everyday appropriation and spatial usage reflect and reinforce social dynamics These practices are inherently shaped by societal expectations and cultural norms, resulting in varied individual experiences and contributions to spaces. Housing, as a lived experience, servesadualroleinboththephysicalstructureandsocial space where relationships are formed, negotiated, and contested [5] Despite this, current research primarily focusesonthestructuraloreconomicaspectsoflow-income housing, paying little attention to the complex genderspecificspatialexperiencesthatoccurwithinthesesettings ThisgapisprominentlyvisibleinDhaka,wherelow-income communities experience distinct social and spatial disparities duetourban density, economic hardships,and cultural norms. Addressing this gap, this paper explores women ’s spatial experiences through the lens of social capital.GuidedbytheWorldBanks’sframework,thisstudy seekstoanswerthecentralquestion: “How do shared social spaces influencewomen’s social capital formationwithinlowincome housing in Dhaka?” By offering a gendered perspectiveonsocialcapital,thispapercontributestourban sociology, gender studies, and housing design, providing

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

practical insights for more inclusive urban and housing policies.

Housing constitutes a fundamental determinant of individuals and collective well-being. Within this domain, low-income housing represents a critical strategy for addressingurbanandsocio-spatialinequalitiesbyproviding affordable shelter to economically deprived populations. However,suchhousingoftenlackswell-designedspacesand hassystematicissues.Thispaperusesqualitativeresearch methods to explore how women perceive shared social spaces and how these spaces influence in development of socialcapital Therefore,thepaperaimstoexaminehowthe availability of these spaces impacts women’s capacity to buildrelationshipsandaccessresourceswithinthehousing environment

2.1

Housingisoneofthefundamentalhumanrightsandconsists ofelementsthatformacompleteecosystem.Housingandits builtenvironmentbothinternallyandexternallyplaycritical roles in balancing and maintaining societal sustainability Whilehousingisperceivedprimarilyasaphysicalentity,its social aspects are equally significant as the tangible amenities.Thearrangementandconfigurationoftheliving units along with the spaces surrounding them, deeply influence the socio-cultural values and the formation of social capital within the community However, in recent times, due to land scarcity and housing shortages, urban populationsaremorelikelytoadjustandadapttocompact living conditions, which leads to more congested accommodation and reduced opportunities for social interaction. Moreover, the spatial layout and quality of accommodation not only affect physical comfort but also impacttheestablishmentoftrustandcommunicationwithin communalenvironments

Social capital was firstintroduced asa concept inthe20th century and has obtained prominence in recent studies Manyscholarshavefrequentlyciteditsspatialsignificance and explained its function as a shared resource for communities [6][7]. Even though, factors such as context, time, or the characteristics of the community affect the dynamics of interactions between people and their surroundings. At the same time, these factors impact the gradual development of social capital. Additionally, these aspects also shape the nature and efficacy of this capital, allowing people to utilize the resources to overcome obstacles [8] According to [9] Jacob (1961), in urban settings, social capital is essential for improving sustainabilityasthiscapitaldevelopsmutualrelationships which are defined by reciprocity and cohesion towards

sharedgoals.Atthemicrolevel,socialcapitalcontributesto familywell-being,andcommunitystrengths,andimproves overalllivingstandards[10].

Hence,socialcapitalisnotmerelyadefinitionoranidea,it hasthefullcapacitytoempowerthecommunityparticularly whenthereisinadequateinstitutionalsupportorinsufficient infrastructure [11]Putnam’s(2000) work offers insights intothetwotypesofsocialcapital Thefirstone-bonding capitaldiscussesthehorizontalconnectionsandassociations withinhomogenousgroups.Thisformofcapitalfostersclose tiesandinternalcohesion.Ontheotherhand,thesecondone - bridging capital describes the association across diverse demographic and cross-cultural groups that contribute to inclusivity and integration. In the low-income settlements especially in the developing regions, the establishment of social capital is linked to social and cultural norms which oftenplayavitalroleinshapingcommunityperspectives In ordertoenhancethecollectivegrowthandfunctionalityof thiscapital,thisisimperativetocomprehendbothbonding andbridgingcapitalalongwithitsdynamicsinsuchsettings.

Housingofferswomensafety,leisure,andincomegeneration opportunities, as well as access to necessary facilities and infrastructure [12] According to [13] UN-Habitat (2014), women actively participate in economic and household dutieswhilealsofosteringsocialconnectionsandpromoting communal well-being. However, in low-income housing, culturalexpectationsandsocietalstructuresstronglyimpact howwomeninteractwiththeirimmediateenvironment.The spaces inside and outside of their living units are not just physical areas for them but also important parts of their sociallives.

In Bangladesh, cultural norms often emphasize domestic rolesandlimitwomen’sindependencewhichrestrictstheir accesstofinancialandeconomicresources.Astheprimary caregivers and homemakers, women remain confined to their homes, where they perform regular chores and, in some cases, involve themselves in home-based incomegeneration activities like sewing or preparing food. This physical and cultural confinement highlights the unequal relationshipbetweenmenandwomenindomesticspaces, with women taking on responsibilities of household management [13] The lack of safe and accessible spaces makes these challenges worse According to [14] Rolnik (2011), women are disproportionately affected by the gender gap, making it challenging for them to access adequatehousingandworseningtheirlivingconditions. In low-income or marginalized settings, women's spatial experiences are closely linked to everyday domestic responsibilities,andinurbanareas,thisisevenmorevisible as mobility and safety is a major concern. Shared social spaces such as water points, narrow alleys, or courtyards serve as regular venues for communication and practical support Theseinteractionsareessentialforfosteringsocial

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

capitalwhichoffersemotionalsupport,sharesinformation, and helps overcome regular obstacles such as safety concernsandresourceshortages.

According to [4] Lefebvre (1991), social spaces are a dynamicconstructandareshapedbysocietalrelationships He further argued that space is both a product of human activities and a means of production, reflecting larger structures and inequalities of society When talking about shared social spaces in low-income housing, where the spatialdynamicsoftenmirrorthesystematicdisparities,this perspective is relevant In unplanned or poorly designed housingareas,spacesgenerallydeveloporganicallyrather thanintentionallydesigned

The housing social spaces mainly refer to the traditional courtyards, common playgrounds, shared facilities, or transitional spaces but in the context of low-income and marginalized settlements, all these are largely absent. In suchsettings,socialspacesarein-betweenspaces,narrow alleys, or water points, usually those that are not intentionallydesigned Often,suchlackofplanningleadsto crowded,congestedareasthatarenotsufficientorinclusive of all facilities. Even today, women, children, and elderly peopleareamongthemostdeprivedpeopleinsocietyand are mainly excluded from the benefits of such spaces Women,inparticular,areforcedtomakedifficulttrade-offs between social engagement and their safety when shared spacesarenotproperlygivenordesigned.Accordingto[15] Emmanuel (2012), low-income housing is not merely a componentoftheurbanlandscapebutalsoasiteofsocietal struggle. For those at the bottom of the hierarchy, it underpins inequalities that limit their access to opportunities

This paper adopts a qualitative method to understand women ’ s spatial experiences in social spaces within a selected case study. The case area was chosen for its representation of low-income status and due to having availablespaces.

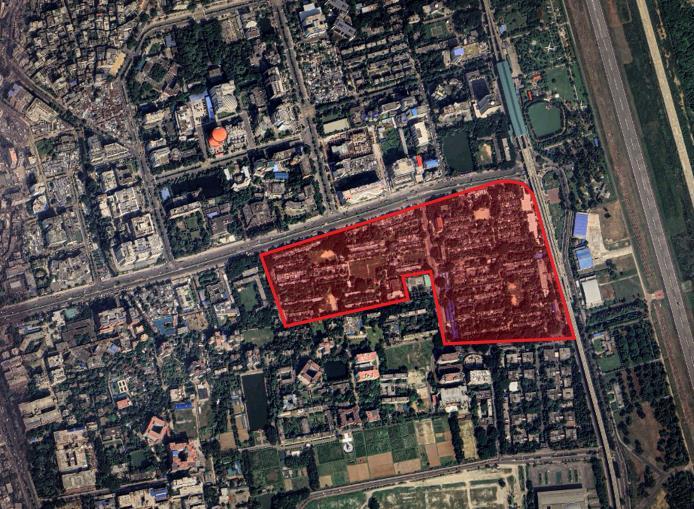

The case study aims to demonstrate how a concept or theoreticalframeworkcanbeappliedinvariedcontexts.In thispaper,thestudyiscontextualandseekstolookintothe daily lives of women to address the spatial aspects and currentrealitiesthatareoftenoverlookedbyexperts.Hence, thispapercentersonDhaka,thecapitalofBangladesh,with aspecificfocusontheSher-EBanglanagarHousing Thecase is located in the heart of the city and comprises prime landmarks, along with both primary and secondary connecting roads The housing has three major blocks namely,F-G-H.Theselectionof thissitewasguided by its

demographiccompositionandthespatialorganizationofthe housing premises. Spanning an area of approximately 30 acres,thecomplexconsistsofaround600residentialunits.

These housing units primarily serve individuals in lowerrankingpositionsinthepublicsector,reflectingtheirmodest income levels. Allocations are determined by income bracketsandhierarchicalpositionswithinthegovernment sector.Thespatiallayoutincludessocialspacessuchasfront yards, adjacent alleys, common intersection points, communal facilities, and three main fields. All these available spaces are part of the quarters and the complex whichwerealreadyincorporatedduringthedesignphase. Thesedefiningattributesmakethishousinganidealcasefor explaining the intersection between social capital and genderperspectivesinlow-incomehousing.

Giventheexplanatorynatureoftheresearchquestion,this paper incorporates a widespread literature review to comprehend the key dimensions of the study at hand. To ensureinternalvalidity,atriangulationapproachhasbeen employed, combining multiple data collection methods. Whilearchitecturaldrawingsandplanningdocumentswere considered secondary data; to gather primary data, semistructuredinterviewsalongwithobservationswereused.A total of 15 interviews with women occupants were conductedtounderstandtheirregularusageandperception of the spaces. Participants were chosen according to their age using purposive sampling to ensure diversity in representation. The age groups were divided into three categories,young(13-29),middle-aged(30-44),andelderly (45-65),eachcategoryconsistedoffiverespondents.Allof the interviews were performed and recorded with prior consent

Aninterviewguidewasdevelopedbasedondimensionsof social capital, including both open and closed-ended questions.Tocomplementtheinterviewdata,bothstaticand

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

mobileobservationswereexecuted.Whilestaticobservation took place at predetermined points using the observation guide,mobileobservationinvolvedwalkingthroughthe spacestogatherdynamicperspectives.Inadditiontothat, sketches,photographs,andnoteswerealsousedtokeepthe informationanddataupdated. Allinterviewswereanalyzed withAtlas tiandthematiccodingwereapplied,focusingon theWorldBank’soutlineddimensionsassociatedwithsocial capital.Forcoding,thedimensions wereusedasthemain indicators,andinterviewswerearrangedaccordingtothe agegroups. Finally,thepaperconcludesbypresentingthe findings withscientific reasoning grounded in thespecific contextthatdirectlyanswersthemainresearchquestion.

Social capital, according to [16] Grootaert et al. (2004), is generallyacknowledgedasamultifacetedtermandcanbe defined through two interconnected lenses [17] The first lenswhichisinfluencedbysociologistslike[18]Burt(2000), focusesonhowpeopleobtainsupport,assistanceaswellas information from their interpersonal interactions. In contrasttophysicalcapitalsuchastechnologyorequipment andhumancapitallikeexperienceorwisdom,socialcapital is derived solely from social relationships and communications. The nature and frequency of these relationsareimpactedbythevalueoftheconnections[18]. On the other hand, the second lens looks into how engagement in both formal and informal networks contributestotheadvancementofsocialcapital[17] This ranges from various activities, for instance, informal interaction with neighbors to involvement in communal organizationsorhavingpoliticalaffiliations

Thispaperbuildsonthetheoreticalfoundations,employing theframeworkoutlinedin“World Bank’s socialcapitaland social cohesion measurement toolkit” . Four main dimensionsofsocialcapitaldefinedbythisframeworkarerelationships,resources,trust,andcollectiveactionnorms. Therefore, in this paper, these dimensions are applied to examine the spatial experiences of women within shared social spaces in the surveyed low-income housing. These componentsarefurtherbrokendownintosubcategoriesto thoroughlycomprehendthemultipleaspectstoanalyzethe spatialandsocialdynamics Thefollowingtableprovidesa

structured approach to understanding the interplay of relations,resourceexchange,trust,andcollectiveactions.

Table -1: Dimensionsandsubcategoriesusedtoanalyze socialcapital:

Dimensions

Social relations

Resource exchange

Subcategories Description

Bonding

Bridging

Material resources

Non-material resources

Collective action norms

-Connectionwithin homogenousgroups, fosteringmutualsupport

-Interactionsbetween diversegroupsor networkscreatebroader socialties.

-Physicalitemsshared orexchangedsuchas goodsortools.

-Emotionalor informationalexchange supportingsocialand economicneeds.

Interpersonal trust -Trustinindividualsto actineachother’s interest

Institutional trust -Trustinorganizations orauthoritiestoact responsibly

Shared purposes -Collaborationsto achievecommongoals

Guidedby responsibility

-Activitiesdrivenby moralorethical obligationswithinthe community

Inthecontextoflow-incomehousing,socialrelationsoften emerge naturally and are intertwined with their social connections or economic activities. According to [19] Massey’s(1994)claim,ratherthanbeingneutralorstatic, spaceisshapedbysocietalrelations.Shefurtherarguedthat space is an “inherently dynamic simultaneity”, where multiplesocialprocessesco-existandmayvarydepending on how things are arranged [19]. In Sher-E Banglanagar Housing,thisframeworkisevidentasthegenderedactivities areintegratedintotheavailablesocialspacesbasedontheir usage and meaning. During the interview, women particularlymidtoelderly,showedstrongbondingcapital withintheirimmediatesurroundings.Accordingtomultiple interviews,theydependon theirfellowresidents for both practical and emotional support. This underscores, how these spaces act both as a necessity and a means of connection. The social spaces function as an extension of

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

privatedwellingswherewomenperformhouseholdchores likepreparingfood,dryingclothes,orsupervisingchildren. All these informal gatherings or interactions strengthen intra-group ties, creating opportunities for frequent and meaningful communication For instance, common fields becomesitesofcelebrationduringfestivalssuchasEid,or frontyardsareusedforchildcareexchange,allowingwomen to engage in shared experiences that deepen their connections.Asa52-year-oldrespondentshared:

“While cooking or watching the children, we often chat with ourneighbors- it’showwestayconnected.Evenduringfestival preparations, we all pitch in, whether it's cooking or decorating, everyone helps- it feels like we are one family.”

Thestrikingthemewasthegenderednatureoftheavailable social spaces, as women are the primary users of these shared spaces during the daytime since men are largely absentduetowork.Thisdominancehighlightstheircentral roleinnurturingsocialtieswithinthehousingcommunity

One58-year-oldelderlywomanmentioned:

“Men leave for work early, but we are here, keeping an eye on everythingandeveryone. Thesespaces belongtousduringthe day.

”

While bonding social capital thrived within smaller and homogenousgroups,interactionsacrosssocioeconomicor cultural groups were notably limited Most cross-group exchanges were confined to polite greetings or brief conversations However, respondents reported that occasionalmomentsofbridgingcapitaloccurinopenareas such as common fields, where children play together and womenengageinconservationduringfestivals.One36years oldmotherreported:

“Sometimes duringfestivals, wechatwithpeoplefromthenext block. It'snice, butitdoesnot happenoften.Whenthechildren play together, it’seasier tostart aconversation with someone you don’t know well. But once the event is over, everyone goes back to their routines.”

Theseinteractionsthoughlimited,providedglimpsesofthe potentialforsocialspacestoactasbridgesamongdifferent groups Theydemonstratethefactthatwhengiventheright

conditionswhetherthroughcommunityeventsorfunctional spaces,individualsandgroupscouldconnectmeaningfully. However, the limited nature of such interaction also exhibited the critical shortcomings of the lack of intentionallydesignedspaces.Respondentsnotedthatwhile some spaces tend to favor certain activities, they lack the infrastructure or layout that is needed to encourage consistentengagementacrossdiversegroups. Asa46-yearoldsaid:

“The openfieldisjustanemptyplot. Iftherewerebenchesora small seating area, maybe more people would gather here regularly.”

In low-income housing, where an individual faces deprivation of necessary allocation, resource exchange amongthemismorelikelytooccurviainformalnetworksor social connections. In such settings, people often rely on mutual aid and reciprocity to offset the formal resource deficiency. Those social spaces are not only the sites for materialexchangesuchasborrowingtoolsorfetchingwater butalsoplayakeyroleinfunctionalneeds.Onerespondent explained how these spaces are woven into their daily routines:

“The front yards are not just for chores, it's where we discuss problems, planevents, andsupporteachother, thenagain,the communal field or staircase is where we meet every morning, we talk about family or work, and sometimes even help with each other with small tasks. It's like starting the day with a connection.”

Theaccessibilityofmaterialresourcesinsocialspacesalso shapedwomen’smobilityandparticipation.However,their effectiveuseoftendependsonfactorslikemaintenanceand safety For instance, poorly maintained staircases or overcrowdedwaterpointspotentiallylimitaccessandeven create tension among users. While the material resource exchangeoffersthefoundation,non-materialexchangesuch asemotionalorinformationalexchangeemergedasthekey enabler of social capital during interviews. The intangible resourcesareoftenactivatedinspecificspatialsettingssuch asbackyardsorfrontyards,providingprivacyandsafetyfor certaindiscussions.A55-year-oldwomanreported:

“The front yards are a safespace for ustotalkfreely, weshare our problems discuss challenges, and help each other to find solutions ”

InSher-EBanglanagarHousing,womenusetheseinformal gatheringstoexchangeknowledgeonchildcare,health,or financial matters. All these sentiments were echoed in multiple interviews. The value of material spaces is inherently tied to the non-material dynamics within the community. For instance, older women usually share parentingadvice,whileyoungerwomenofferemployment

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

opportunities, highlighting the interplay of spatial arrangement and non-material resource flow. These findings align with [20] Bourdieu’s (1986) interpretation, which states that resources are inherent in links and relationships. Hence, non-material resources extend the utilizationofphysicalspaces,resultingintransformingthem frommerestructuresintositesofempowerment.Thiswas particularlyseeninthewayswomenusedcollectiveidentity to overcome resource constraints in Sher-E Banglanagar Housing

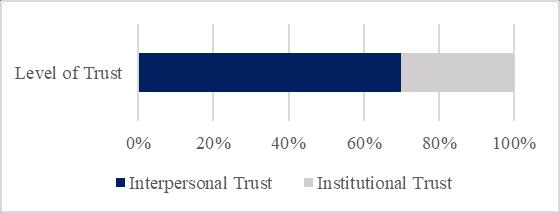

Thispaperdistinguishesbetweentwotypesoftrust-oneis interpersonal trustwhichunderlinessocial bondsandthe other one is institutional trust. Here, institutional trust discusses the residents’ confidence in authority and governance along with the maintenance of their shared environments. Both forms of trust are reinforced by the spatial arrangement. In Sher-E Banglanagar Housing, interpersonal trust appears as a cornerstone in fostering resilience among women in communal settings. As [21] Dempsey et al. (2011) added trust acts as a foundational component in establishing ties among individuals and creatinglong-lastingsupportiverelations Duringinterviews, almostallwomenregardlessofage,reportedhighlevelsof interpersonaltrust,cateredinsharedsocialspaces.Women described how these spaces serve as an environment for their children to play and foster cooperative behaviors amongresidents.A35-year-oldwomannoted:

“I usually leave my children to play in common alleys or front yards with other kids, anyone passing by or watching them from their own homes keeps an eye on them Even in the afternoons, we all gather around the field and everyone feels safe, everyone is trusted and we feel safe. These spaces are maintained by us, we keep them well-lit ”

These spatially mediated interactions strengthen social capitalassharedspacesprovideopportunitiestoengagein reciprocal care and mutual trust. However, in contrast, institutional trust remains fragile. Women expressed dissatisfaction over inadequate governance of spaces that undermines their confidence in formal actors Poorly maintained streets and common fields as well as a lackof secureentrypointswerecitedasbarrierstotrust.

Table -2: Identifiedthreeprimaryconcernsaffecting institutionaltrust,allofwhicharetiedtospatial conditions:

Aspect

Percentages (%)

Maintenance issues 50%

Safety 30%

Governance 20%

Examples

Brokenlights, uncleanspaces

Concernsaboutthe maingate

Delaysincomplaint responses

Suchfrustrationsanddissatisfactionsrevealadisconnection betweenthespace ’sintendedfunctionandactualcondition in recent times which limits its usability and weakens institutionaltrustinhousingmanagement.

The collective action norms, promote cooperative performances among women and are defined by shared goals along with a sense of responsibility. The physical layoutofthesurveyedhousinghasastrongimpactonthese norms. According to [22] Uphoff and Wijayaratna (2000), norms of reciprocity and shared responsibilities are essential for nourishing collective efforts, particularly in settingswithlimitedcapitalorresources.Inadditiontothat, thepresenceofsharedobjectivescanalsoreducetheimpact ofinsufficientformalinstitutionalsupportsincecommunity needsareoftenmetbygrassrootsinitiatives.Itwasnotedby therespondentsduringinterviewsthatitwasnecessaryto makecoordinatedeffortstokeepthestaircasesandcommon spacesfunctionalandclean.Thissyncswith[11]Putnam's (2000) view of social capital, which elaborates that communitycohesionisenhancedwhencollectiveactionis guidedbycommongoalsthatgobeyondindividualbenefits

Furthermore,astrongsenseofresponsibilityalsoactedas theinitialgroundforcollectiveactions.Whileinstitutional supportsareeitherabsentorinsufficient,womenreported taking the initiative to address security concerns, lighting

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

issuesforsafety,orwatershortages.A32-year-oldwoman said:

“Insteadof waitingforthehousingauthoritytorespond,weall triedtofixanybrokenlightsorbrokenpumps. Welookafterit because it's our space If we don’t do it all by ourselves, they remain the same, unsolved for months ”

Thisisinlinewith[23]Ostrom's(1990)outlineoncollective actionandsharedresources,whichhighlightsthestrengthof community-led authority and shared goals in managing common purposes, especially when formal actors are inadequate.

Table -3: DynamicsofCollectiveactionnormsinsocial spaces:

Dimensions

Shared purposes

Sense of responsibility

Spatial configuration

Community Impact

Actions

Collaborativegoalsthatunifywomen anddrivecollectiveengagement

Womentakeownershipofissues affectingsharedspaces,steppingin whereinstitutionsfail.

Sharedspacesasdynamicplatforms thatenableinteractions,problemsolving,anddecision-making

Strengthentiesandimprovethe functionalityofspacesthrough grassrootsactions

Urbanhousingplanningandpolicyinterventionsareoften intended to encourage inclusivity, making it crucial to consider the spatial significance to reach socio-spatial sustainability. The existing body of scholarly works and examinationsonsocialcapitalandspatialdynamicsismostly influenced by Western perspectives and narratives. In addition to that, it has been noted that an acute lack of gender-focusedanalysisinsocialcapitalresearchprevails Addressing the gap, this study presents some significant findings. The key outcome of this paper underscores the positiveassociationbetweenspatialconfigurationandsocial capital formation among women within the housing premises.Thispaperbuildsontheargumentbyexamining howwomeninsurveyedhousingusesharedsocialspaces andhowtheseinfluencesfostersocialcapital.Thefindings indicated in most aspects that respondents who were regular users of shared social spaces, reported stronger social ties and mutual support systems over time. These housingspacesservemultiplefunctionsatatime,theyactas centers for creating vital social networks simultaneously reinforcingopportunitiesforwomentoperformcollectively Scholarshavearguedthatwomen’sinvolvementwithspace is closely related to their socio-economic responsibilities,

positioningthemaskeyagentsinformingsocialconnections [19].

A hierarchy of private to public spaces was seen in the spatiallayoutofthehousingthatwasunderstudy,allowing womentoutilizethesespacesindiversewayseveninthe absenceofadditionalamenities.Inlow-incomesettings,such spaces are usually adapted to meet daily necessities Thematiccodingofthefindingsrevealedthatcompactfront yardsandsharedalleyswereusedextensivelyformutualaid that contributes to community resilience. These spatial experiences among women aided in developing bonding socialcapitalbyestablishingasupportsystemthroughdaily communication. This aligns with [20] Bourdieu’s (1986) notion that social capital is embedded in associations and everydaypractices.Duetothefactthatmostoftheresidents ofthecommunitybelongedtoasimilarincomegroup,they showedahomogenouscharacter Thishomogeneityfurther supported the development of positive bonding capital However,thefindingsindicatedthelackofbridgingcapital, highlighting the limited inclusivity among different socioeconomicgroups.Respondentsmentionedthatspaces,such asthecommonfieldwereprimarilyusedforcross-cultural communicationsduringfestivalsorweekendgatherings

Besides, material exchangessuchasborrowinggoodsand non-material exchanges like emotional support were integraltowomen'suseofspaces.Thisperspectiveenhances theintegrationofspatialandsocialphenomenabyenabling adeeperunderstandingoftheopportunitiesanddifficulties specific groups face in utilizing spaces. Furthermore, the findingsofinterpersonaltrustsupport[21]Dempseyetal. (2011)claimthattrustisthebasisforcohesion,yetthistrust remainsspatially mediated,relyingonthefunctionality of overallspatialexperience Ontheotherhand,lowlevelsof institutionaltrustwerefoundduetothelargergovernance disparities in low-income housing environments This segregation is a common scenario in low-income settings, which further exacerbates the marginalization of such communities. Moreover, [11] Putnam's (2000) theory of social capital as the driver of shared involvement and resiliencecomplieswithwomen ’sproactiveinvolvementin tackling communal issues Nevertheless, the reliance on grassrootsinitiativesalsosuggestsstructuraldeficienciesin formalgovernance,whichmayrestricttheoverallviabilityof theseoutcomes.Atthesametime,ithasbeennotedbythe respondents that merely providing spaces without additionalfacilitiesmaynotbeadequatetofulfillthedesired community needs. The elderly women, in particular, expressed concerns about the spatial insufficiently to supporttheirmobilityandsocial engagement.Despitethe challenges, the active use of space by women of all ages illustratedtheiradaptabilityandresourcefulnessinutilizing spatial opportunities for social networking and resilience building,thereforefosteringsocialcapital.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

The association between social capital and gender is a multifaceted topic, shaped by multiple interconnected factors that influence each other and operate both individuallyandcollectively.InthecaseofBangladesh,these dynamicsgetfurthercomplicatedbyculturalinfluencesand norms. Social capital and gender perspective are not only affected by contextual factors but also by the constraints imposed due to social values, which often limit women’ s opportunities Addressingthesechallengesrequiresamore sensitive approach to housing design particularly that considerstheinternalenvironments

Housingisthefoundationalspaceforwomenandchildrento create formal and informal networks, making spatial considerationessential. Hence,theone-size-fits-allmethod may fail to account for gender-specific needs. Promoting genderequityinhousingdesignrequiresacknowledgingthe diverse ways in which men and women contribute at the neighborhood scale to the development of social capital. Context-specific indicators and cultural norms need to be consideredtoensureeffectivesocio-spatialsustainabilityin low-income settings. This paper highlighted the spatial relevance in the development of women ’ s social capital Lookingintowomen’sspatialexperience,revealedthatthey consistently utilize shared social spaces to build mutual support, even when these spaces are not intentionally designed for that purpose. Even though the analysis indicated positive findings regarding the social capital dimensions, it also revealed disparities in cross-cultural integrationalongwithgapsininstitutionalsupportthatlimit thefullpotentialofcapitalformation.Thispapercontributes tothebroadertheoreticaldiscourseontheintersectionof gender,space,andsocialcapitalbyshowcasingwomen’srole in negotiating the socio-spatial constraints. The findings highlightedtheneed forinclusiveandparticipatoryurban and housing planning that prioritizes gender-sensitive approachestoensureequitableaccesstospaces Thispaper concludes that, in low-income settings, when spatial opportunitiesaregiven,womeneffectivelyfostercommunity networks that enable them to address challenges when required. While it underscores the resilience of women in utilizing spatial opportunities, it also calls for systematic changesinplanningandgovernance.

Despitethecontributions,thepaperhascertainlimitations Thefindingsshowninthepaperarebasedonthequalitative interviewsandobservationswithinasinglecasearea,which mayhavelimitedthegeneralizabilityofitsconclusionstothe otherlow-incomehousingcontexts.Furtherresearchcould explorethelimitationbyconductingcomparativestudiesin different housing areas. Moreover, investigating multiple caseareasthatencompassdiversedemographicgroupscan capture the social capital more effectively. Furthermore, longitudinal studies may have provided insights into how socialcapitalevolveswithchangesinspatialarrangements

Such research would deepen the understanding of how space can support community development and gender justiceinhousingpoliciesanddesign.

[1] Agnitsch, K., Flora, J. & Ryan, V. (2009). Bonding and bridging social capital: The interactive effects on communityaction. Community Development, 37(1),3651.doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330609490153

[2] Hodgkin, S. (2009). INNER WHEEL OR INNER SANCTUM. AustralianFeministStudies, 24(62),439–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164640903289310

[3] Moser, G., Ratiu, E., & Fleury-Bahi G. (2002), “Appropriation and interpersonal relationships: From dwelling to the city through the neighborhood”, In Environment and behavior, 43,no1.

[4] Lefebvre,H.(1991)TheProductionofSpace.Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. First published as La Production de L’espace

[5] Lefebvre,H.(1984).EverydayLifeintheModern World(1sted.).Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351318280

[6] Lin Nan. (1999). Building a Network Theory of Social Capital.Connections,22(1),28–51.

[7] Mpanje,D.,Gibbons,P.,&McDermott,R.(2018).Social capital in vulnerable urban settings: an analytical framework. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-0180032-9

[8] Rayner, A. D. (2011). Space cannot be cut Why selfidentity naturally includes neighborhood. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 45(2), 161–184.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-011-9154-y

[9] Jacobs,J.(1961).ThedeathandlifeofgreatAmerican cities. New York, NY: Vintage Books. Retrieved from: https://www.buurtwijs.nl/sites/default/files/buurtwijs /bestanden/jane_jacobs_the_deat h_and_life_of_great_american.pdf

[10] Hamdan,H.,Yusof,F.,&Marzukhi,M.A.(2014).Social capitalandqualityoflifeinurbanneighborhoodshighdensityhousing. Procedia: Social & Behavioral Sciences, 153, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.051

[11] Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone Conference: Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on computersupported cooperative work https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 01 | Jan 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[12] United Nations. (2012). Women and the Right to Adequate Housing. New York and Geneva: United NationsHumanRights.

[13] UN-Habitat. (2014). Women and Housing: Towards Inclusive Cities. Nairobi: United Nations Human SettlementsProgramme

[14] Rolnik, R. (2011). Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living and on the right to nondiscrimination in this context.GeneralAssemblyUnited Nations.

[15] Emmanuel, J. B. (2012). “Housing quality” to the lowincome housing producers in Ogbere, Ibadan, Nigeria. Procedia: Social & Behavioral Sciences, 35, 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.02.114

[16] Grootaert,C.,Narayan, D.,Jones,V.N.,&Woolcock,M. (2004). Measuring Social Capital: An Integrated Questionnaire (Washington, DC, World Bank). https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/08213-5661-5

[17] Woolcock, M. & Narayan, D. (2000). Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research, and Policy. The World Bank Research Observer, 15(2),225249.doi:10.1093/wbro/15.2.225

[18] Burt, R. S. (2000). The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 345–423.https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-3085(00)22009-1

[19] Massey,D.(1994). Space, Place, and Gender (NED-New edition). University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttw2z

[20] Bourdieu, P. (1986). The Forms of Capital. In J. Richardson(Ed.),HandbookofTheoryandResearchfor the Sociology of Education New York Greenwood.References - Scientific Research Publishing. (n.d.). Retrieved fromhttps://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespaper s?referenceid=1558112

[21] Dempsey,N.,Bramley,G.,Power,S.,&Brown,C.(2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19(5), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.417

[22] Uphoff,N.,&Wijayaratna,C.M.(2000).Demonstrated benefitsfromsocialcapital:Theproductivityoffarmer organizationsinGalOya,Srilanka. World Development, 28(11), 1875–1890. doi:10.1016/S0305750X(00)00063-2.

[23] Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The EvolutionofInstitutionsforCollectiveAction.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress.