Policy Brief

Policy Brief

SAVING LIVES CHANGING LIVES

Social protection can play a key role in supporting climate change adaptation and mitigation by providing income protection to those affected by climate shocks and disasters and facilitating a green economy transition through skill development and employment opportunities. To enhance their effectiveness in responding to climate shocks, social protection systems require robust data on population characteristics and detailed information about the intensity and likelihood of potential shocks. However, many countries operate with social registries1 focused on collecting data to assess chronic poverty based on proxies that are fixed or change slowly over time, limiting their ability to predict and respond to climate shocks effectively.

This brief provides recommendations for enhancing the quality of social registry data and integrating it with climate risk information. These measures aim to improve the identification of vulnerable populations and inform the design of adaptive and shock-responsive social protection interventions to support climate adaptation and mitigation efforts.

1. A social registry is a database or system that contains information on households and individuals within a specific population. Its purpose is to provide a centralized and up-to-date data source that can be used for targeting, planning, and implementing social protection programs.

Sri Lanka experiences significant natural hazards, primarily floods, droughts, extreme heat, and landslides, which are exacerbated by climate change. Floods are the most common type of natural hazard in Sri Lanka with 37 recorded events between 1981-2020, followed by droughts, then storms. In Sri Lanka, flood hazards are common across the country’s lowland areas, whereas drought hazards are closely related to the timing and geography of the country’s two monsoon seasons, the more robust Maha season and the milder Yala season, spanning from November to February and May to September respectively. 19 million Sri Lankans are projected to live in locations set to become moderate or severe climate hotspots by 2050. Climate change projections show an increasing trend in extreme events and natural disasters that pose significant threats to Sri Lanka’s economy and human health.

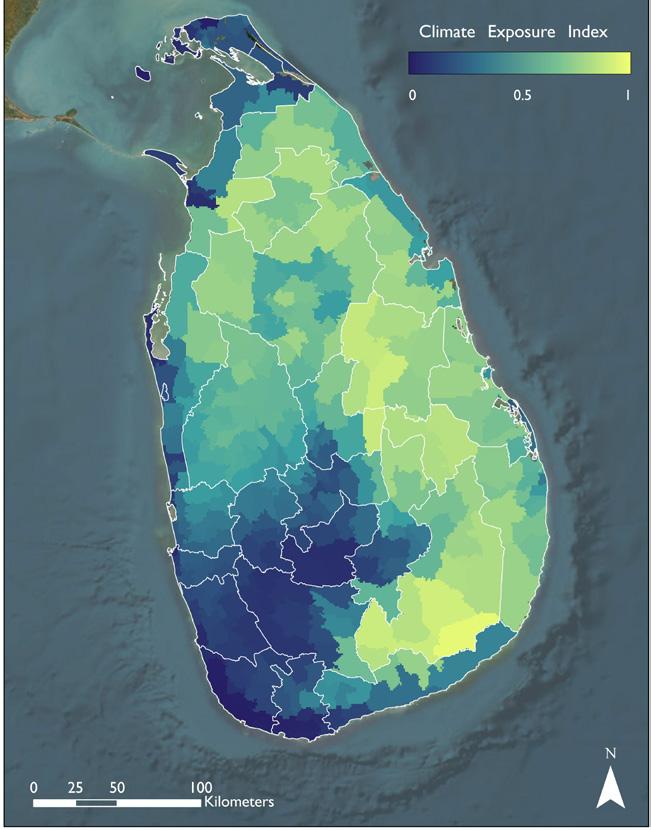

A Climate Risk and Vulnerability Analysis conducted by Tetra Tech (Map 1) shows households located in high-exposure areas. The most climate exposed households can be found fin northern and north-central provinces, where droughts, floods, and landslides threaten main livelihoods, like rain-fed rice paddy agriculture. Additionally, in the southeastern Uva Province, extreme heat and drought impact main livelihoods like rice farms and tea plantations in relation with Sri Lanka’s monsoon seasons. The analysis estimates that 7% of the national population (369,644 households) reside in regions highly susceptible to climate-related hazards.

Sri Lanka’s Social Protection System Overview

The newly introduced Aswesuma scheme, launched in 2023, is a consolidated welfare system that aims to create a poverty-free Sri Lanka by 2048, focusing on livelihood development. It marked a significant evolution in Sri Lanka’s approach to social protection, progressing towards beneficiary identification, coverage, targeting, and delivery mechanisms, wich will enhance the country’s ability to respond to climate risks through more efficient systems.

Sri Lanka’s key progress includes:

• Reaching nearly two million poor and vulnerable families and providing benefits through Aswesuma.

• Improved targeting using a multidimensional poverty indicator has ensured that nearly 950,000 new families, who previously did not qualify for government assistance, now do.

• Introduction of direct digital benefit transfers to beneficiaries’ bank accounts enables foster transfer of assistance.

• Identification of beneficiaries based four categories—transitional, vulnerable, poor, and extremely poor, allowing Aswesuma to tailor its assistance based on the degree of need.

The Aswesuma program uses a new Integrated Welfare Management System, run by the Welfare Benefits Board, to store beneficiary data collected from both online and physical registrations. The social registry for the program currently holds data on 3.4 million households, while only targeting 1.8 million families. The program uses 22 criteria to assess eligibility, which includes data on household information, assets, income, demographic details, and educational attainment. These criteria are based on multidimensional poverty indicators developed by the Department of Census and Statistics for the 2019 Household Income and Expenditure Survey. The social registry in Sri Lanka serves as a crucial tool for identifying and targeting vulnerable populations for social assistance programs, yet some limitations exist.

• Sri Lanka lacks a unified social registry. The functionalities of the consolidated digital and data management systems, IWMS, remain limited with other social assistance programs, like the Elderly Allowance programme, Disability Allowance programme, and the Thriposha National Supplementary Food Programme.

• The Aswesuma program intake grievance process is not fully digitized. 70% of forms are submitted via hard copy and manually inputted into the IWMS system, slowing data processing and increasing opportunities for errors. Processing all the information collected during the first round of data collection for the Aswesuma programme took approximately 2.5 months.

• The Aswesuma 2022 enrollment data is accessible via IWMS’ online portal. However datasharing agreements with agencies outside of government has been slow, and there is limited use of social registry for social protection programming outside of Aswesuma. Increasing linkages with other ministries and development agencies could support more shock-responsive programming.

• Aswesuma has encountered issues with beneficiaries’ understanding of its objectives and eligibility requirements. The programme could benefit from a public awareness campaign to clarify Aswesuma’s objectives and goals for cash transfers.

Integrating social protection into disaster risk management and climate risk indicators into social protection registries allows for a holistic approach to managing risks faced by vulnerable populations. Sri Lanka’s strong disaster risk management sector tracks historical climate and hazard data and flood and landslide vulnerability assessments. Despite these resources, significant gaps remain in terms of accessing and using the data for improved social protection program targeting.

• Climate risk data exists, especially amongst disaster management agencies, but siloed databases and limited data sharing lead to a lack of integration and use of climate risk data in social protection programming. Beyond individual champions, there is currently no integration at the policy level encouraging collaborative efforts amongst the ministries governing these sectors.

• Disaster management agencies are not yet utilising impact-based forecasting, which could improve predictions on how vulnerable population will be affected by disasters. Utilising socio-economic data from the Aswesuma registry could provide more granular details, such as the distributions of specific populations or the manifestation of disabilities.

• Climate vulnerability data is not captured in the current registry, yet a disproportionate amount of vulnerable households (about 65,000 hh.2 ) live in climate-sensitive areas. Expanding the registry to capture additional climate-vulnerable information can help social assistance programs improve targeting for shock responsiveness.

2. Estimates based on Tetra Tech’s Climate Vulnerability Assessment from May 2024.

Strengthening social protection in Sri Lanka while integrating climate data involves leveraging existing government capacities. Key strategic points and recommendations for consideration include:

Invest in robust climate hazard and exposure analysis for geographic targeting.

Investing in climate hazard analysis is essential for identifying vulnerable regions and supporting low-income households. Various efforts are ongoing to develop climate hazard maps, but efforts need to be centralized to create a comprehensive mapping for social protection.

Integrate climate vulnerability indicators in the multidimensional poverty index. The Aswesuma program uses a Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) to assess well-being across various dimensions, but does not yet include climate vulnerability indicators. To address this, the government should integrate climate risk factors into the MPI, considering physical exposure, impacts on households, adaptive capacities, and input from relevant ministries. Technical support and guidance from the Department of National Planning and the Department of Census and Statistics is essential for effective implementation and addressing the dynamics of vulnerability in a changing climate.

Identify and register climate-vulnerable “near poor” households.

Risks posed by climate change are not factored into the four poverty classifications of severely poor, poor, vulnerable, or transitional under Aswesuma. Concerns exists that households may experience downward mobility within these categories due to their exposure to climate-related shocks. A climate vulnerability score is recommended, categorizing risk into high, moderate, and minimal levels. This would enable targeted support and improve targeting of early warning dissemination for climate-vulnerable households, including those not currently benefiting from Aswesuma.

4

Progressively build a household-level climate risk index in the Integrated Welfare Management System for long-term use.

While a climate vulnerability score based on the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) can enhance targeting strategies, using it without climate risk considerations may miss specific household vulnerabilities. It is recommended that a detailed risk and vulnerability analysis at the household level be conducted and integrated into the Integrated Welfare Management System (IWMS). Creating a multifaceted climate risk index that incorporates various hazards, exposure levels, and vulnerabilities at the

household level is vital for enabling detailed risk mapping and prioritization of support at a household level to facilitate effective shock-responsive programming.

5

Revamp the existing livelihood component of the Samurdhi program to address climate risks and impacts to livelihoods.

It is recommended that Samurdhi pilot projects from 2024 to 2026 be designed with risk-informed approaches by conducting a comprehensive mapping exercise to identify the most vulnerable livelihoods and the specific climate risks the initiatives may encounter. Additionally, exploring different climate financing options and partnership models could bring more stability to the program.

6

Strengthen coordination among key government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and international partners to better engage in disaster management, climate change and social protection.

Noting the siloed nature of various agencies, a comprehensive climate risk management strategy could be developed to effectively address disaster management, climate change, and social protection challenges. Establishing a national climate-smart social protection task force could also address coordination gaps between government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and international partners.

7

Strengthen the existing social protection systems and build the capacities of actors. Each sector has specific technical and capacity constraints that currently stand in the way of more cross-sectoral collaboration on the issue. For example, the Aswesuma program targeting, intake, and grievance processes need additional support to reduce exclusion errors and increase the speed and accuracy of data processing. The disaster management sector could use additional resources to upgrade data collection efforts on vulnerability, exposure and coping capacity. It is recommended that the government of Sri Lanka prioritise investments in existing social protection system components and implementation processes to build capacities for stakeholders to establish a strong shock-responsive social protection system.