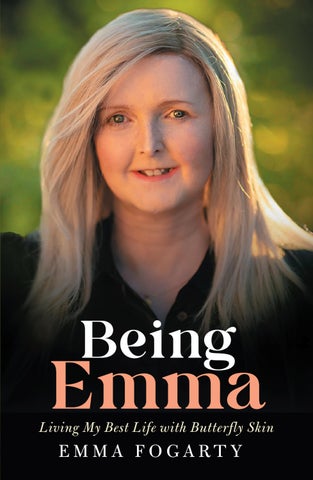

Being Emma

Emma Fogarty is a writer, activist and advocate living with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), a rare and painful skin condition. At forty-one in 2025, she is the oldest living Irish person with the condition, continuing to defy the odds with her extraordinary strength and resilience, as well as her remarkable achievements, including taking part in the 2024 Dublin Marathon.

To my mother and father, for taking me home.

Author ’s Note

Some of the names in this book have been changed to protect the identity of those involved in certain incidents.

Foreword Colin Farrell

My friend Emma Fogarty is truly one of the most extraordinary women I have ever had the good fortune of meeting. We’ve been friends for some fifteen years now, and since our first meeting our friendship and knowledge of each other’s lives has deepened, as tends to happen over time. I feel in a very fortunate position to be at the receiving end of her kindness and generosity, her spirited humour and sense of fun.

I also feel uncommonly blessed that she pulls no punches in her sharing of life’s struggles, the totality of her story. Emma has always been keen never to feel sorry for herself. She is quick to remind me and others that there is always someone worse off. And yet, the constant and excruciating pain she lives with, by being trapped in a body that has been punishing to inhabit, is real.

Her journey in and through life has been a remarkable one. Born with a cruel and debilitating disease, whose sole concern is to inflict pain and suffering upon those who live with it, she has defied the odds in so many ways. It’s indeed a miracle that she is still with us, and our lives – everyone fortunate enough to encounter her – have become more rich for that fact. But Emma’s greatest defiance is not that she has lived to see her forty-first birthday, though doctors – as soon as she was born – said she would live

only weeks. Her greatest defiance is her insistence on living a full and meaningful life. A life of adventure and joy. A life that is, of course, limited in many ways by Epidermolysis Bullosa, but a life that has shared so much laughter, so much friendship, had so many challenges chosen and imposed, and has triumphed over them all.

It is not that Emma is still alive that is the miracle. It is how Emma has chosen to live in the face of such adversity that is the true miracle. Her story is one that I feel needs to be shared. I have, in our years as friends, derived incredible hope through the power of her spirit. I have also felt anger and pain at what she has had to go through. And … I have been baffled by her courage. She squirms when I say such things, but it’s just the way it is.

I’m so thrilled she has decided to share her story. It is a story not only of an individual’s call to arms in the daily fight of having a warrior spirit trapped in a battle-broken body. It is also a family story. Of her mother, Pat, and father, Malachy, and her sister, Catherine. The love they have shared. The triumph of that love through all the challenges that life has thrown in their shared path.

Emma’s life is an extraordinary one and she is quite simply a beautiful and powerful human being. She’s one of the greatest teachers we have and if the reader can feel even an ounce of the wonder, the sorrow, the strength and hope that I have felt in knowing her, then they will walk away with a life enriched for the time spent in the company of this amazing woman.

Los Angeles June 2025

What is Butterfly Skin?

Epidermolysis

Bullosa (EB), commonly nicknamed ‘butterfly skin’, is a rare genetic condition that makes a person’s skin incredibly fragile – so fragile that even small things most people wouldn’t notice, like rubbing against bedsheets or wearing shoes, can cause painful blisters or open wounds. People with EB are often called ‘butterfly children’ because their skin is as delicate as a butterfly’s wing.

On the surface, skin with EB may look normal. But underneath, the layers don’t hold together the way they should. So the skin can peel apart simply from friction – walking, hugging, eating, even sleeping. For some, the condition is relatively mild. For others, it affects not only the skin but also the eyes, mouth, throat and internal linings of the body.

In the most severe forms, it can be life-threatening.

EB is caused by a fault in the genes that means the proteins needed to hold the skin together are missing. These are like the glue or anchors that keep the skin’s structure in place. If the gene is damaged or missing, the body can’t make those anchors properly. Which gene is affected determines what type of EB someone has. Some people inherit it from one parent, others from both. In most cases, it’s something a person is born with and lives with every day of their life.

One of the more serious forms of EB is called Recessive Dystrophic EB. In this type, the faulty gene affects collagen –

specifically collagen type VII, a protein that normally forms tiny rope-like structures called anchoring fibrils. These fibrils work like nails, holding the top layer of skin to the layer beneath it. Without them, the skin slides and tears easily, often leaving deep wounds that scar. Over time, the constant damage can cause the fingers and toes to fuse, and even simple acts like eating or swallowing can become incredibly painful and even impossible if the lining of the throat is affected.

People with EB also suffer from osteoporosis. This can make life even harder and more painful, suffering constant breaks and bone disintegration.

Living with EB means daily bandaging, constant wound care and a lifetime of managing pain, risk of infection and complications. There is no cure.

Prologue

I’m a Survivor

My mother tells me that when I was born the room fell deathly silent. She knew something was wrong, but she didn’t know what. Neither did the nurses, nor the doctor they rushed to find. That silence didn’t last because I began to cry, and my mother tells me I didn’t stop at all. Because I was born in terrible pain. My name is Emma Fogarty and I’ve just turned forty-one. I live in Abbeyleix, in a nice home with views of the fields, and I love my fashion, my shoes, my music and a glass of bubbly at any opportunity.

Oh, and I have a genetic skin condition called Epidermolysis Bullosa. We shorten that mouthful to EB. What it means is that I’m missing the collagen that sits between the layers of my skin. I’ll explain it to you this way. Imagine that your skin is attached to your muscle with a sort of Velcro. Well, I don’t have the Velcro at all and so there’s nothing giving my skin any stick. The layers of my skin just float around on top of each other. Skin is fragile anyway, but with no collagen, if I get hit, my skin tears like paper. And there is nothing anyone can do about it.

With my form of EB, both parents have to have a faulty gene to cause the condition. Of course, my parents didn’t know that when their eyes met across a dance hall in Limerick, and they didn’t know it when they married and when my mom was pregnant with

me. The first time they knew of it was when they were told what was wrong with their new baby. And it was a while before they heard the words ‘Epidermolysis Bullosa’ at all. The first thing said to them by the doctor was that I would not live a week.

Maybe the fact that I did survive the week, and the next one, and the year, and on and on, formed in me a sort of stubborn insistence that I would live and I would be happy. Because I am. I love my life and I love living every day of it, even the hardest ones. And there are plenty of those.

You see, I have EB, but it is not me; EB is not who I am. EB is a condition I have. But I am not my skin. I am Emma. I am Catherine’s sister, Pat and Malachy’s daughter, Kim’s friend. I’ve got a life behind me and a life ahead of me. Just like you.

This is my story.

Part One

Becoming Emma

1

Delicate

You probably haven’t heard of EB. Most people haven’t. It’s not something that gets big news coverage or massive awareness campaigns. There aren’t films about it.

But for the people who live with it – and for their families – it’s our whole lives.

Epidermolysis Bullosa doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue – it sounds like something scientific you read about in journals, but that’s not what it’s like when you have it.

In real life, EB is up close and personal.

Imagine your skin is as fragile as paper. Imagine a hug can cause a wound. Imagine that wearing clothes can tear your skin. EB makes the simple things brutal.

There’s no cure, not yet, though researchers always promise them. There’s not even a treatment, not in the way most people would think of it. With EB it’s all about management. Daily, long, painful routines just to keep the body safe and us sufferers alive.

For me, with the type of EB I have, it’s a full-time job. For me, EB means bandage changes that take up to four hours, three times a week, and partial changes in between. It means infections that need constant monitoring, skin that won’t heal properly and pain that no painkiller ever quite covers. EB, for me, means being always cautious, always careful, yet still, somehow, always covered in wounds.

Some people’s bodies carry them through the world. My body has always needed a plan, always needed someone else to help. And so, I have never experienced freedom.

But …

EB is not my whole story. It’s a part of me. A big part, yes, but not the only part.

Because EB has given me a viewpoint I don’t think I would have had otherwise. It has made me see the world differently. It has taught me patience, resilience, compassion. It has taught me how to listen – really listen – to other people’s pain. And it has made me stubborn in the best way – EB has made me really determined.

EB has also given me community. Through Debra Ireland, through other families and kids like me, I’ve found people who get it. People who don’t need it explained. That’s a rare gift and a precious one.

People always ask, ‘Is EB rare?’ and the answer is yes – it’s very rare. Fewer than 300 people in Ireland have it. However, just because it’s rare doesn’t mean it’s not worth talking about. It’s the rare things that need shouting about the most. Because when you’re rare, sometimes you’re at risk of being forgotten.

People also ask me, ‘Do you wish you didn’t have EB?’ and that’s a complicated one. Of course I do. Of course I wish I could run, or wear what I like, or stand at a concert for hours without pain. But I also know that EB shaped me – my values, my choices, my voice. EB made me who I am. And I like who I am.

So yeah, EB is brutal. It’s exhausting. It’s unforgiving. But I am still here.

That’s EB. And that’s me.

When my mother, Pat, was pregnant with me, there was no need for anyone to worry. It was her first baby and things went along as normal. There were no warning signs, no unusual scans. Labour went ahead with no alarm bells, nothing to cause any concern.

But as soon as I arrived into the world, all of our lives – my mother’s, my father’s and mine – were changed. I was born badly wounded, with no skin at all on my left foot, and they didn’t know why. Then a nurse tried to feed me and the metal edge of her little nurse’s watch hit off my cheek and pulled the skin off it. Just a normal smooth-sided watch – something every nurse used to wear – and it injured me so badly. My skin was like tissue paper.

‘We don’t know what’s wrong with this baby,’ the doctor said to my mom and dad and, just like that, the floor dropped out from under them.

The doctors were baffled. They sent a sample of my skin away for testing. As they waited, my parents rang their loved ones. My dad’s mother, Nana Fogarty, set down the phone and made arrangements to get up to Dublin. As soon as she could, she drove to the hospital without stopping. I imagine she prayed all the way there.

By the time Nana Fogarty arrived in the hospital, I had been baptised, just in case. In those days Ireland was still fully immersed in the idea that purgatory and limbo existed, and so, within hours of my birth, a priest was called. He blessed some tap water and gently poured it over my head. That was my christening. Just Mom, Dad and the priest were there. My name, chosen quickly from the shortlist they’d hoped to mull over, was Emma.

Also by the time Nana Fogarty got there, the biopsy results had come back. My parents had an answer. Now they knew what was wrong with this baby.

The words were new to everyone in the room: Epidermolysis Bullosa. The words that would come to define my whole life.

‘She won’t live a week,’ the paediatrician said. And just like that, my life was given an expiry date. Just like that, there was a ticking clock.

He added something else. ‘I’m sorry to say this, but she would be better off if she didn’t.’

My aunt Angela was the first person my mom told.

‘Her skin is like paper,’ she said, ‘I don’t know what to do.’

Angela hung up the phone and ran straight away across the back fields behind her house to bang on the door of a nurse she knew. She wouldn’t have known this woman well enough to bang on her door like that, but she did it anyway because she just needed something, anything – an answer that would give my mother hope.

The nurse told her everything she knew, but her words hurt. ‘Babies with that condition rarely make it,’ she said, ‘and if they do it’s a very hard illness to live with; there will be no quality of life whatsoever.’

I’ve been told this story so many times it plays in my head like a film – my aunt running all that way to get hope, information, a reason. I don’t know what it would have felt like for my family to hear such devastating news delivered so sharply. Although I definitely know what that baby would have felt when her skin tore. Because I still feel that every day and have done for my entire life.

I couldn’t suck on a bottle because the rubber tore my lips, so I was a ball of frustration until they figured out how to drip milk

into my mouth. My mother cut a hole in the teat so the milk could be brought out without much work, and I was fed that way – drop by drop, hour by hour.

On my mom’s side, the Bowens mobilised and gathered in Angela’s house – my aunts Marguerite, Martina, Marie and my uncle Sean – to start making baby clothes inside out so the seams wouldn’t harm me. They sewed through the night to get clothes to Mom so she could dress me.

That memory, though it’s not mine directly, burns so vividly in my heart.

Aunt Angela, God bless her, also bought me my first doll. I still have it, a little soft thing with long legs and closed eyes stitched on. Sleeping Dolly became her name. I clung to her then and sometimes still cling to her now. Sleeping Dolly became one of those sacred belongings that babies (and grown-ups) cannot be without. Myself and Sleeping Dolly have been through a lot.

I spent the first few months of my life in Crumlin Hospital, in and out of incubators.

Despite what the doctor had said, I lived a week, then a month, and when I was three months old, they told my parents there was nothing they could do for me.

‘We are sorry for you,’ they told them, ‘but your child will not live for long.’

‘I think Emma is a survivor,’ my mother said.

‘Well, if she lives,’ came the reply, ‘she will have a very hard life. You should take her home.’

So they did. They brought me back to the home we still live in, in Abbeyleix, County Laois.

That was probably the moment when my parents could have given up on me. No one would have blamed them. They’d been told I could never survive this condition. But I think my mother decided then and there that even if that was the case, I would have a life. Not an existence, a life. Even if it was just a few months or a year, there would be family and friends and adventures.

When my parents left the hospital with me in their arms, Aunt Angela showed up with a camera and started snapping photos.

Mom turned to her and told her to stop.

‘I won’t,’ Angela said. ‘Emma wasn’t supposed to live a week and look at her now, coming home.’ For her it was a momentous day.

She took a whole roll of film of me that day. I’m glad she did because I have the photos now and I will admit I was a very cute little baby.

Then, one day not long after I came home, Nana Fogarty rang and told my parents she had found another Irish family whose little boy had EB too. That felt like a light shining through the dark for my parents, and they went to visit them the very next time they were in Limerick, which is – coincidentally, as my parents are both from there – where this child was from.

‘This is Bobby,’ his parents said as soon as they opened the door. My parents looked down at a little boy with blistered skin. He was playing with his toys, happy out, on the floor of the sitting room.

Just seeing Bobby there so happy gave my parents real hope. It also gave them something else: a connection to another family who knew exactly what they were going through. This family were ahead on the road they were just starting out on, and they

gave my parents the promise that I could make it along that road too.

My parents could have wrapped me up in cotton wool and kept me in a box – I was small enough. But they decided that day that they wouldn’t. Their daughter wasn’t going to spend her life in the shadow of EB. No matter how long I lived, I would be out in the open.

If this family and this boy could do it, so could we.

My parents were open-minded in ways that you don’t always see in people who find themselves faced with something so brutal. They refused to see me as broken. It was never what can’t Emma do? It was always what can Emma do?

That’s something I carried into every year that followed and maybe it’s where I get my stubborn streak and determination.

I wasn’t supposed to make it to my first birthday, but I did.

I wasn’t supposed to go to school. But I did.

I wasn’t supposed to see my tens, my twenties, my thirties, my forties.

But I did.

There is a power in being underestimated – is that the lesson we take from this? Maybe those words – ‘she won’t live a week’ –went in. Even as a newborn, did I hear those words somehow and did they make me brave?

I had nothing to lose by being scrappy. The world goes around regardless, whether you’re here or not, so you may as well cling on. And maybe because of the start I had, the pain I felt from the beginning, it gave me a sense that even when you fall, even when it hurts so much your eyes water and your chest heaves, you just have to keep going.

Because it’s worth it. It’s so worth it to be alive.

My parents didn’t give up on me, they didn’t hand me back to

the hospital and say this is too hard. They didn’t shrink from the hard work of keeping me alive. They rolled up their sleeves, got on with it and taught me to do the same.

And that’s what I’ve done every day since.

Try

Tomy family I was simply a normal child who needed extra care. I didn’t know what it was to have normal skin. For me it was a case of realising as soon as I learned to walk that falling meant real pain.

My mother was on the phone to the doctor when she first saw me stand up, hands out in front of me, starting to toddle across the room in front of her. She told the doctor she had to go, not so she could get the camera, but because she needed to make sure I didn’t fall. And after the first few times, I learned falling was not something I could easily recover from. So I avoided it as much as I could.

I was a little girl who walked and didn’t run, who took care when getting up or down from the couch or my mom’s lap. I was never going to do tumbles, but I wasn’t upset by that. I didn’t want to do those things because I knew the consequences. I knew the risk wasn’t worth the reward, not for me. I was absolutely content sitting on the floor playing with my little dolls and my teddies.

Still, my memories of being little are just like yours: playing in the garden or my bedroom, watching TV, going on outings with cousins. Sitting in the back of the family car on the way down to my Nana Fogarty’s, looking out the window every time my mom said, ‘Horses, Emma, look!’

Dad taught in secondary school, primarily maths, but he could cover a bit of everything when needed. He started off in a small school in Abbeyleix, and later, when the population of Laois grew a bit, his little school got absorbed into the larger community school. That’s where he stayed until he retired.

I remember one year when I was really small, maybe only three, the school Dad taught at was putting on a show, Oliver Twist, and they were stuck for the role of Fagin. Totally against character, Dad said he would do it. I don’t know how reluctantly, but I do know he learned the songs, the lines, the whole thing, and he sang them over and over at home until we knew them too.

When the night of the play came, Mom and I went along to the school to see it. I was excited, waiting for my dad to come on. Anyway, the lights dimmed, the music started and on came this man – this scraggly, bearded old rogue of a character.

Mom leaned down and whispered, ‘There’s Daddy.’

Well, I wasn’t having a bar of that. That wasn’t my dad, that was some stranger with a beard dancing around the stage. And when Dad came down after the show, still in costume, and tried to sit beside us and coax me onto his lap, I refused point blank. No matter how much my mom tried to convince me it was Daddy, I would not believe it. In my child’s mind I thought Dad could only ever look one way. He had to take the beard off before I would so much as consider that it was him at all. Then I got it. It’s a cute memory.

Even though I cried a lot, I was a happy child. My parents took me to Lourdes when I was six, just before I started school. I don’t remember much about it, but I know we stayed in a hotel. One thing I do remember is the priests dipping me in and out of the cold baths and my mother warning them, ‘Gently! Gently!’ – of course they weren’t gentle and so I screamed the whole time. But in the evening people gathered together and sang lovely folk songs. I

thought that was great craic. I would sit on whichever knee would have me and enjoy the music.

I started Junior Infants in Scoil Mhuire in Abbeyleix a year late. I knew most of the kids in my class already – we’d been together in play school. Abbeyleix is the kind of small town where everyone knew who you were – especially if you were me.

The teachers knew us too. They knew who might need help with reading, who might cry if their mam was late, and who (me) needed to be handled with a little more care. Not that they ever made a big show of it. They were just kind. And I loved it there.

I didn’t think it was special that I was going to school, but the local paper did. They took my picture and wrote a whole article describing me as a miracle child who was going to school. I didn’t get it at all, not at six. I could hardly see myself as a miracle. I still don’t. I have always seen myself as just Emma. But, of course, it was a miracle. All the odds were stacked against me.

For me, going to school was an obvious step. Now I know that my parents were behind the scenes, working with the school and speaking to the other parents, asking them to explain to their children that they needed to be gentle with Emma and why. And so, of course, on my first day I was something of interest. But kids don’t tend to dwell on things, and before long I was just Emma to them too.

I loved primary school because of that. I didn’t get stared at. I wasn’t different or unusual. I was simply a classmate, the one who came in after everyone else was sitting down and the one who left just before the bell rang, to avoid getting jostled in the crowd.

My mother drove me to school at first, as slowly as she could without causing a traffic jam, taking the bumps in the road at five miles an hour. Ours was a busy school and cars would pull up outside and let the children out, and so would she – though a bit later than everyone else – and I would walk inside like every other child.

I loved that small moment of being by myself because I was rarely ever by myself.

My first few years of school were mostly just like yours, with tadpoles and márla and learning the letters phonetically in songs, only I couldn’t do PE and I couldn’t go out to the yard. I would observe other children as I walked along, watching for the smallest sign that they might move unexpectedly – the lowering of a shoulder, the twitch of a hand. If there was a group of children ahead of me, I would give them a wide berth and hope to get by before someone started a sudden game of chase. I still do that.

The teacher would ask for volunteers, usually four, to stay inside with me at lunch time and play in the classroom. There was something about that – access to the classroom without a teacher – that made every hand in the class go up. That became my thing. Staying in at lunch with eager volunteers.

As well as my first day at school, another milestone was my communion, where the whole family got together and dressed for the occasion. I had the little white dress, little soft ballet slippers and a silk halo on my head with ribbons down the back. I even wore gloves, and I was delighted with myself. I still have the little white drawstring bag that you see on the arms of little girls all over Ireland on that special day.

Afterwards, we had people back to our house for a cup of tea and I was slipped pound notes and fivers, which I stuffed into that little bag. I’d imagine I put it in the post office, and it might still be there because I don’t remember ever taking it out!

As I got older, I took the chance of going out to the yard quite a few times. It was too enticing, hearing the big games planned. I’d convince myself I could play too, convince myself I could avoid a bump. I never could, not with one group playing football and another playing chase. Once I turned just in time to see a football heading straight for me.

‘You gave it a header, Emma!’ the lads kept shouting over in good spirits, but I could see they were worried. I was okay. No skin tore, but I did have to go home. I soon learned that going out was never worth it.