PROLOGUE

THE TELEGRAM ON January 24, 1965, time-stamped 3:49 p.m., extended a formal invitation to an ailing, largely forgotten ninety-three-yearold British army general in Canada to attend the funeral of a famous ninety-year-old statesman in England. “Please cable if you can or cannot accept invitation to state funeral of Sir Winston Churchill St. Paul’s Cathedral London Saturday 30th January 1965 Stop.”

The invitation was delivered to a name and an address in a distant place, St. John’s, Newfoundland, the recipient presumably unfamiliar and irrelevant to the organizers of an event of global interest and historical significance. Major General Sir Hugh Tudor had lived a quiet life in self-imposed exile in Newfoundland for nearly forty years and by 1965 was almost immobilized by the infirmities of old age.

He had not seen his old friend Winston Churchill in twenty-seven years, but the friendship obviously remained as fresh in 1965 as when it began seven decades earlier. Their correspondence had continued until, it would seem, both lost interest in the diminished empire they had served and a society that, over time, had disappointed them. Tudor’s name was on the list because he was prominent among the

LINDEN

M AC INTYRE

people who were still loved and admired by the great Englishman Churchill as he approached the end of his life on earth.

Over the years Tudor had accepted several important invitations and requests from Churchill he might prudently have declined. This one he would have wanted to accept, but by January 24, 1965, his own mortality obliged him to turn it down. The general would follow his old friend to the grave eight months and one day later, on September 25, 1965.

The broad outline of their lives offers a superficial explanation of their friendship. They met as young men in a still robust British Empire, as ardent imperialists and English army officers; both had started military careers in India and had crossed paths often as they fought in or observed the various wars of their early years.

The essence of the friendship is harder to define. While Tudor shared a surname with British kings and queens, he had no genetic link to royalty or privilege. The army had offered him a departure from the conventional Tudor family experience in commerce and religion. For Churchill, the army promised the excitement of violent conflict. He had a seemingly voracious appetite for danger. War, he once insisted to his wife, was “a game played with a smile.” His destiny, however, was determined by his DNA and British history. War would make him famous, but his role in the conflicts that would define his legacy would be, essentially, political.

It is possible that Churchill envied the clarity of his friend’s career. He and Tudor met frequently during the First World War, when Churchill served briefly as a battalion commander on the Western Front while Tudor was rising through the ranks as an artilleryman, soon to be the youngest divisional commander in the British army. Their contacts at the front continued even after Churchill became a key minister in the wartime British cabinet.

By the end of the Great War, Tudor had been ten times mentioned in dispatches for gallantry in combat.1 He was promoted in the field to the rank of major general. At forty-seven, he was still young. His reputation was solid. His rank guaranteed a comfortable living and, at the end, a pension that promised a sustainable retirement. He had a young family—four children whom he hoped to help through all their youthful challenges and nurture to maturity.

Instead, within two years, Tudor would be at war again, a brief war, but one that would consume his hopeful future. In the spring of 1920, he was summoned by his oldest friend to serve the British Empire in another conflict, this one close to home—in Ireland. Churchill was, by then, British secretary of state for war.

This would be a war that mocked the value of Tudor’s prior military knowledge, a war that would, for future generations, provoke debate about who, if anybody, won it—or if, in fact, it ever ended. It would affect Tudor’s life in ways he could not have imagined in the days of victory after November 1918 and then as a leader of the occupation forces in defeated Germany.

In Ireland, Major General Tudor would oversee a war for which he was personally and professionally unprepared—a war inflamed by hatred and propaganda too deeply sourced in history for a conventional response; battles fought in ditches, behind hedges; an enemy without uniforms or discipline or rules or scruples; an enemy who looked like him, who spoke his language. What he would experience in Ireland would bear little resemblance to the wars he had studied, the wars he’d fought. This would be a conflict that foreshadowed a future in which citizens demanding self-determination, freedom from colonial authority and institutions, would make armies of their own, deploying their own propaganda and any form of violence that might advance their cause.

LINDEN M AC INTYRE

His time in Ireland would mark the beginning of the end of the world as Hugh Tudor, his profession and his class, had known it. In Ireland, Tudor would be swept up by the primal energies that surface, even in the most seasoned military leader, when personal survival is at stake. And he would come to understand that the First World War was not, as his generation had hoped, “the war to end all wars.” It was, instead, the beginning of a century of conflict, wars of liberation from the past and struggles to control the future of a world as it was being redefined by ideology.

Ireland was, in many ways, a hopeless war for both the British war minister and the British soldier on the ground. They both knew they had but one imperative—to win. Winston Churchill would find a way to define the outcome of the Irish war as a victory. But for Churchill’s friend the soldier, his engagement with the Irish War of Independence would be the beginning of a long journey into personal oblivion.

Part I A NEW FOUND LAND

Word over all, beautiful as the sky!

Beautiful that war, and all its deeds of carnage, must in time be utterly lost . . .

Walt Whitman, “Reconciliation”

(a poem admired by Michael Collins, IRA leader and commander-in-chief, Irish National Army, July to August 1922)

Wednesday, November 25, 1925

THE RMS NEWFOUNDLAND was ten hours late as she slowly approached the narrow entrance to St. John’s Harbour just before one o’clock in the afternoon. The North Atlantic was still heaving after a prolonged southeaster that had tied up shipping in and around the island through the night and for most of the previous day. The temperature hovered just above forty degrees Fahrenheit. Dark clouds raced across a broken sky, and a bitter autumn gale whipped the city streets clear of most pedestrians. Among the anxious passengers aboard the Newfoundland were two Irish doctors, an Irish priest, and a quiet English merchant who might have offered a distraction from the weather had the Irishmen been aware of who he was or inclined to start a conversation with a controversial Englishman.

Major General Sir Henry Hugh Tudor, now in transition to civilian life, had survived nearly thirty-five years of active service in the British army: colonial skirmishes and intrigues in India, Egypt and Palestine and in the Boer War, four years on the Western Front in the First World War, and, recently, a dirty war in Ireland. His name would have been familiar, thanks to the notoriety he had attained in Ireland as commander of policemen called the Black and Tans. Most of the English-speaking world was familiar with their reputation for brutality—part myth, part propaganda, but by 1925 rooted in enough reality to make anyone associated with the outfit a fugitive.

There was little else about him that would have sparked the curiosity of fellow passengers. Average height, dark eyes, a trim military moustache. A female admirer had recently noted “a close-knit athletic figure . . . the clear complexion of a boy; no one would imagine him to be in his early fifties.” 1 He was well dressed, reserved. He looked the part of the provincial merchant he had decided to become.

While his name, in recent years, had been in the news, he’d rarely been photographed. His job in Ireland as head of a police force with an aggressive military mandate had made him permanently vulnerable. He rarely ventured anywhere unarmed. In one of the few snapshots from his time in Ireland, he is in civilian clothes, wearing a hat that partially obscures his face and a long, baggy overcoat that conceals a slim physique. He is pinning a medal on a policeman, and he seems shorter than the man receiving the decoration—then again, perhaps he stooped to conceal his fitness, age and height.

Being inconspicuous was a large part of a carefully managed survival strategy. People who were intent on capturing or killing him wouldn’t recognize him out of uniform. Efforts to track him around Dublin had inevitably failed because he avoided predictable routes. He abstained from socializing outside the walls of Dublin Castle. Even in those presumably secure confines, headquarters for the British administration in Ireland, the occupants ate with their revolvers on the table.2

Some Castle colleagues had openly criticized Tudor’s tolerance for rough, sometimes criminal behaviour by his policemen. His tight relationship with Winston Churchill, the British minister for war, and what seemed to be a fawning admiration and unconcealed encouragement by the prime minister, David Lloyd George, would have limited the possibility of real collegiality among the bureaucrats and army officers with whom he lived and worked in Dublin. But he had his own group of loyal friends, a half-dozen officers with

whom he had served in the Great War. They rewarded his unquestioning support by performing or at least tolerating often brutal duties without hesitation.

It was Tudor’s first trip to North America. According to the passenger manifest, he was employed by Holmwood and Holmwood, a London trading company that also specialized in finance and insurance— two challenging professions for which the career soldier had neither experience nor expertise. There had been speculation in the British press in May 1925, repeated in a St. John’s gossip column in June, that the British general was moving to Newfoundland to “engage in the fishery” 3 —another line of work for which absolutely nothing in his resumé could have prepared him. The son of an Anglican priest, he’d grown up in the shadow of cathedrals, untroubled by the unsteady fortunes of factories, fish plants or finance.

The November storm in the mid-Atlantic would have come as a shock after a pleasant voyage out of Liverpool under sunny skies a week earlier. Tudor’s first impression of his new home might have come as yet another jolt. Travellers arriving in St. John’s would sometimes comment on the twin spires of a grand cathedral that loomed over the low-rise city, or the dramatic citadel on the north side of the harbour entrance, Signal Hill, a memorable spectacle diminished by a squalid sprawl of shacks on the hillside and the shore below.

In the opinion of at least one visitor, it was preferable to arrive at night, when the only visible evidence of settlement was a warm glitter of city lights that “lend romance that is somewhat lacking by daylight.” 4 Had his ship been on schedule, Tudor would have arrived in darkness. Now, in the early afternoon of a stormy day, the harsh daylight revealed ramshackle structures huddled along the waterfront behind rickety finger piers and tiers of wooden buildings sprawled against a steep hillside.

General Tudor left no record of his first impressions. That he would settle in St. John’s, die there, and find eternal rest in a local cemetery might indicate that he grew to like the place.

Whether he knew it or not, Tudor shared a lot of history with the old North Atlantic city. He grew up in Devon, southwest England. Over several centuries, many Newfoundlanders had arrived as settlers from Devon, determined, like Tudor, to take up the fishing business. Near where he landed in St. John’s, there was an old city neighbourhood called Devon Row.

It was a famous Devon man, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who had first claimed Newfoundland for the English Crown. Another Devon nobleman, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Humphrey’s half-brother, had attempted to colonize the island. Like Sir Hugh, both Sir Humphrey and Sir Walter had won their knighthoods for heavy-handed military operations in rebellious Ireland.5

St. John’s was, in many ways, a microcosm of the world Tudor had left behind him. As a highly decorated British soldier with a knighthood, he would move easily among the anglophiles and Anglicans who dominated politics and commerce in Newfoundland. But he had a more visceral connection that drew him to this remote dominion, and it would serve him well through all the years he would spend here—his life-and-death experience with Newfoundlanders under fire in the final months of the Great War. 2.

HIS ADULT LIFE, like the lives of millions in his generation, and of almost everyone in Newfoundland, had been redefined by war. Henry Hugh Tudor had joined the British army at the age of seventeen. After two years at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, England, he

had spent seven years refining military skills in India. In 1899, while back in Britain, an army friend who was recently married persuaded Lieutenant Tudor to replace him on a draft to South Africa to fight in the Boer War. The newlywed sweetened the deal by offering five hundred pounds in payment, which Tudor cheerfully accepted.6

The young lieutenant was only in the war a matter of weeks when he was nearly killed by shrapnel during an artillery barrage. The army tried to send him home after three months of surgery and healing. He balked. Four days after his release from hospital, Tudor walked up and over Table Mountain, a thousand-foot-high landmark near Cape Town, to prove his fitness for continued combat. He was promptly cleared for duty and remained in South Africa for the duration of the war.7

When war broke out in Europe, in August 1914, Tudor was travelling from Egypt, where he had been based for the previous five years, to begin a holiday in England. He was Major Tudor then, commander of a battery in the Royal Horse Artillery. Like most professional soldiers, he welcomed an important war. It would be good for his career and, in the minds of many, it wasn’t going to last long—maybe until Christmas. As he wrote in the war diary that he kept for the four years he would spend on the Western Front, he “wanted no other job than to command [his battery] in war.” 8

But Tudor’s battery was stuck in Egypt, and he was stuck in England. It was frustrating, but his “orders were definite and [he] just had to lump it.” Which he did for more than three months while the enemy romped through Belgium and into France, threatening to end the war by Christmas by winning it decisively. Eventually, by midDecember, the enemy offensive had stalled and Tudor and his battery were on their way to the front. They spent Christmas Eve, 1914, digging four artillery emplacements just behind the lines on a muddy battlefield.

Then on Christmas Day, to Tudor’s surprise, an unnerving silence descended on his sector of the Western Front, what was clearly a seasonal respite from killing—a bad idea, as he would record in his war diary. “It seems to me that regular armies can indulge in this sort of thing without impairing fighting efficiency; but that an army of excivilians must be stirred up by the propaganda of hate.” 9

Tudor need not have worried about the fighting efficiency of ex-civilians. Millions throughout the British Empire, stirred up by patriotism as well as propaganda, were itching for the fight. One of them was a thirteenyear-old boy named Tommy Ricketts, the son of a fisherman from Middle Arm, White Bay, a tiny village on the northeast coast of Newfoundland. His brother, George, who was four years older, had already volunteered.10 If he could have pulled it off, Tommy Ricketts would probably have lined up right away with hundreds of young Newfoundlanders to join a regiment of “ex-civilians” that was destined to intersect with the life and the career of Major Tudor.

Newfoundland, as a British colony, had a long military history. A Newfoundland regiment helped fight off an American invasion of Quebec in 1775, and in the War of 1812, troops from Newfoundland were prominent in the defence of York (Toronto) and the British capture of Detroit. But the British government eventually withdrew its soldiers from the colony in 1870, and by 1914, the military presence in Newfoundland was almost nonexistent—four cadet brigades sponsored by the island’s dominant religions, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist and Presbyterian.

In a fit of patriotic fervour, the government of Newfoundland—no longer a colony, but now an independent dominion in the British Commonwealth—started enlisting five hundred men to become the core of a new regiment “for land service abroad.” 11 The Newfoundland Regiment would win renown for its sacrifices and achievements on

the battlefield. Before the war was over, it would become the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in honour of its battlefield heroics, the only British army unit to receive such recognition during the fighting.

But in August 1914, the reality of war was inconceivable to the office workers, fishermen and schoolboys who were suddenly determined to be soldiers. War offered immediate relief from civilian drudgery for many, the social status of an officer’s commission for a few, and for almost everyone, a rescue from the tedium of peace.

The government delegated the creation of a regiment to a committee made up of fifty influential citizens. By October 2, five hundred newly minted soldiers were marching to the St. John’s waterfront, on their way to Britain. The Newfoundland Bible Society had equipped every one of them with a copy of the New Testament. But their uniforms, like their military training, were conspicuously incomplete, part military, part civilian, trouser legs tucked into blue puttees.

The Canadian army had contributed five hundred military greatcoats. Winter wasn’t far away. The coats were extra long, the bottoms left unhemmed so they could later be tailored to match the owner’s height. But there hadn’t been time for necessary alterations and so, in many cases, the heavy coats dragged on the ground. Only the officers had proper military headgear. The rank and file wore their best civilian caps and hats.12

Thousands of spectators lined the city streets as “the first five hundred” trudged from their camp on Quidi Vidi pond toward the waiting liner that would take them off for proper training at a military base in Britain. As one young officer later described the scene, “Marching was impossible, discipline vanished as the boys struggled to board the ship, tearing themselves away from the arms of their loved ones.”

They were game for an adventure. If they were afraid of anything, it was that the war might end before they got to it. But as it turned out, they had no cause to worry that they might miss the action.

Before the conflict was finished, nearly twelve thousand men—10 percent of the male population of the island—would go to war.

Of the 500 volunteers who sailed away in October 1914, 429 became casualties. Only 71, almost all non-combatants, survived unscathed; 169 of the first 500 never saw St. John’s again.13

By the summer of 1918, the officer who would lead the regiment through the final and decisive months of war had risen through the ranks to become a major general, commander of the 9th Scottish Division in the British army. By the time the Newfoundlanders came under Major General Tudor’s command in September 1918, they had been hardened by experience. Heavy casualties in late 1917 and early 1918 had reduced their numbers to the point where they were forced out of the shooting war for months while they recovered and replaced lost fighters.

Tudor had been less than thrilled on learning that a battalion of Newfoundlanders would be joining one of his three infantry brigades, replacing a contingent of South Africans that he revered. The Newfoundlanders were, he observed in his diary, older than most of the Scotsmen serving under him. And half of this Newfoundland battalion, old or otherwise, had never been in battle. Fresh replacements for the dead or wounded of earlier encounters, they were about to be front and centre in an Allied offensive calculated to drive the Germans out of Belgium and, finally, to win the war.

The veteran fighters among the Newfoundlanders were also less than excited when they learned about the move. Since coming to the war, they had been in the British 29th Division, where they had survived Gallipoli in 1915 and had been almost wiped out at BeaumontHamel on July 1, 1916, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. They had barely survived a more recent slaughter at the First Battle of Cambrai, in November and December of 1917.

Tommy Ricketts, now seventeen years old, was one of the battletested “old-timers.” He’d been ready to join when he was thirteen. He was fifteen when he finally convinced a gullible recruiting officer that he was older and tougher than he looked. Though he was only five foot six, that was close enough to average height for Newfoundland men at the time. He could neither read nor write and, like his brother, signed his recruitment papers with an X. 14

Shortly after his sixteenth birthday, he was at the Western Front, and soon after that, he was in the thick of fighting: Langemarck in August; Poelcappelle in October; and in November, Cambrai, two weeks of carnage in which eight out of ten Newfoundland soldiers were either killed or wounded in the fighting.

The Newfoundlanders might not have known, nor would they have been impressed to know, that General Tudor had designed the initial plan of attack for the Battle of Cambrai; or that, before the battle began, military analysts praised the innovative tactics he was recommending—a surprise attack, obscured by a heavy smoke screen and supported by an artillery barrage that would coincide with, rather than precede, a massive infantry assault. The battle followed Tudor’s design except for one crucial detail—timing.

The attack appeared to have succeeded as planned on November 20, 1917, and almost immediately, Tudor was being congratulated by his superiors. The praise was premature.15 The final battle plan had failed to include sufficient reserves of infantry support to stop a German counterattack. Over the two weeks of fighting, the Cambrai battle cost the British army 75,000 casualties. One hundred and fifteen Newfoundlanders died, including a renowned sniper, John Shiwak, who was an Innu hunter from Labrador, and George Ricketts, Tommy’s older brother. 16

Tommy himself was seriously wounded. A bullet in the leg would take him out of action for the next ten months. By September 1918, he

was back in the front lines in time for some of the most decisive fighting of the war. He was only seventeen, but he was destined for a date with history, a battle that would make him Newfoundland’s most famous soldier and fame that would in time become an insufferable burden.

3.

EVEN AS A young man Hugh Tudor was obviously destined for the military career that Winston Churchill, had he been less ambitious, less political, less weighted down by history, would have wanted for himself. Tudor was dedicated to the civilizing mission of the British Empire, as was Churchill, and he proved in the Boer War that he was brave and resilient.

Churchill had joined the South African campaign as a “fighting journalist,” writing action-packed war stories for the London newspapers. While technically on leave from the army, usually he was able to place himself front and centre in his sensational accounts of combat. After a shootout in December 1899, he was briefly captured and held prisoner by the Boers.

He escaped captivity to great acclaim back home, an experience that launched a long, adventurous political career. But when he discovered, just days later, that his friend Tudor had been seriously wounded that same month and was recuperating in a hospital in Cape Town, Churchill took the trouble to send a get-well telegram.

Their paths would cross again in the chaotic drama of the First World War. In 1915, Churchill was forced to take a break from parliament because of political controversy over his role in a failed attempt to seize the offensive in the war by attacking Turkey through the Dardanelles Strait and Gallipoli peninsula. He was demoted within cabinet, and, when completely excluded from decision-making, he

kept his seat in parliament but quit the government of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, put on a uniform and went to war as a relatively junior army officer. He took charge of an infantry battalion in the 9th Scottish Division, where his old friend, Hughie Tudor, now a brigadier general, significantly outranked him.17

In Tudor’s Great War diaries, there are more than thirty references to encounters with Churchill on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. They hadn’t seen each other since the Boer War, but in his account of February 7, 1916, the day they reunited on the Western Front, Tudor noted that Churchill was “the same as ever.”

Churchill, in a letter to his wife, Clementine, on February 8, wrote how pleased he was that they were back together, in uniform: “I had tea with General Tudor yesterday. He commands all the artillery of the Division and is quite young—my age about. He and I were friends in Bangalore as lieutenants—and much good polo did we play together.” 18 In personality, they were polar opposites. Tudor was reserved; Churchill was flamboyant. His arrival at the Western Front on Monday, January 3, 1916, would not have gone unnoticed by either British soldiers in the 9th Division or the nearby enemy. A junior officer in his battalion would recall the spectacle:

Just before noon an imposing cavalcade arrived. Churchill on a black charger, Archie Sinclair [his second-in-command] on a black charger, two grooms on black chargers followed by a limber filled with Churchill’s luggage—much more than the 35 pounds allowed weight. In the rear half we saw a curious contraption: a long bath and boiler for heating the bath water.19

The enemy acknowledged the new high-value target in the neighbourhood by maintaining a heavy artillery bombardment on the battalion for as long as Churchill was there.

Tudor, the professional soldier, avoided unnecessary risks. Churchill seemed to thrive on danger, leading hair-raising nighttime reconnaissance patrols into no man’s land, displaying what appeared to be a careless indifference to crashing shells and snipers’ bullets and the possibility of sudden death. After a heavy enemy bombardment while Tudor and Churchill were observing action from a front-line trench on February 8, he described the experience in a letter to Clementine: “I found my nerves in excellent order and I don’t think my pulse quickened at any time. But after it was over, I felt strangely tired.”20

One of his battalion officers, Lieutenant Edmund HakewillSmith, would write that Churchill was like “a baby elephant out in No-man’s land at night . . . He never fell when a shell went off; he never ducked when a bullet went past with a loud crack. He used to say, after watching me duck: ‘It’s no damn use ducking; the bullet has gone a long way past you by now.’” 21

Even after a tragic incident on the night of February 26, when one of Tudor’s guns miscalculated distance and landed an artillery round on one of Churchill’s night patrols, Churchill didn’t seem especially concerned, though the shell killed two British soldiers and seriously wounded four others. Over lunch the next day, Tudor expressed regrets to Churchill, but Churchill seemed to shrug off the episode. Bad things happen during wars. War was “a game,” as he told his wife in a letter home, recounting a pep talk he had recently delivered to his junior officers: “Laugh a little and teach your men to laugh—great good humour under fire—war is a game played with a smile. If you can’t smile, grin. If you can’t grin, keep out of the way till you can.” 22

Tudor’s frequent meetings with his friend while Churchill was at the front were mostly social, but the war was impossible to ignore when drinks and dinners were interrupted by enemy artillery exploding just outside their bunker. Churchill clearly trusted Tudor and he would often seek the perspective and advice of the more experienced

soldier. Tudor’s diary entry for February 11, 1916, records “a very pleasant dinner” during which they drank their favourite champagne, Veuve Clicquot, which was readily available in Bailleul, a French town just two miles from the Belgian border.

That evening Churchill laid out plans for a new fighting machine that was already on the drawing boards and would soon revolutionize the technology of war—what he then called “land cruisers,” soon to be better known colloquially as “tanks.” Tudor wrote, “Churchill visioned them lined up some dark night behind our front trenches and, just before dawn, advanced them to smash through the enemy wire and trenches. I was greatly impressed.” 23

For his part, Tudor bent his friend’s ear with his own idea for improving the effectiveness of infantry assaults by cloaking no man’s land in smoke. Conventional assaults, in which men went “over the top” of their trenches, were generally preceded by heavy artillery bombardment by mostly high-explosive shells. The shelling would destroy barbed wire and intimidate the enemy, but the attacking soldiers remained easy targets for enemy machine guns. But what if the shelling also produced a pall of smoke that concealed the advance and, at least partially, blinded defenders?

At the beginning of May 1916, Churchill abandoned his brief adventure in the trenches and returned to the political battlefield in England. Four days before he left the front, in a letter to his wife, he reported: “The Germans have just fired 30 shells at our farm hitting it four times, but no one has been hurt. This I trust is a parting salute.”

Tudor’s May 7 diary entry was wistful: “I saw Churchill off in the afternoon. I shall miss him very much . . . but he is right to go back to a more important duty than a battalion commander.”

His friend would eventually join a new wartime cabinet, a coalition led by a Liberal, David Lloyd George, as minister for munitions. It was a job that would enable fulfillment of the two initiatives he and

Tudor had discussed in the field, tanks and smoke. Both would play a major role in the first successful round of the ultimately disastrous Battle of Cambrai in November 1917.

In March 1918, Tudor was given temporary command of the 9th Scottish Division when the divisional commander went on leave. Almost immediately, the German army launched a desperate offensive to regain control of a war that, for months, they had been losing.

On March 19, Churchill showed up at Tudor’s headquarters in Nurlu, at the Somme, during a brief period of calm before the anticipated battle. The general and the cabinet minister strolled among the front-line trenches on March 20, clearly visible to enemy observers. No one shot at them. The silence was ominous.

At 4:40 the next morning they were awakened by a series of explosions followed by what Churchill would describe as “the most tremendous cannonade” that he would ever hear. It was the beginning of what the Germans would call Operation Michael, a major offensive to split and overwhelm the French and British armies. Churchill wanted to stay to watch the action. Tudor was in favour. But Churchill’s travelling companions thought it was a bad idea for a senior British cabinet minister to risk his life and the lives of those around him by lingering in what would soon be a ferocious battle.

In the early days of the attack, the Germans threatened to wipe out two British armies. Tudor’s 9th Division helped enable a tactical British withdrawal when the Third and Fifth Armies were forced to fall back to new defensive positions. The prime minister, Lloyd George, later credited Tudor and his division with “a gallant and successful fight” that helped prevent the annihilation of the British Fifth Army.24 Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the British forces, conveyed high praise through a subordinate: “Tell Tudor that but for him and the 9th Division the situation of Flanders

would have been very much worse.” 25 On March 28, 1918, Tudor was informed that for the rest of the war he would remain commander of the 9th Scottish Division, soon to include a group of battle-hardened Newfoundlanders.

Tudor’s tenacity—in Churchill’s words, his division had been “an iron peg hammered into frozen ground”—would be remembered two years later when Lloyd George and Churchill were recruiting talent for another war, a conflict close to home, a rebellion that would mark “the fighting general,” Henry Hugh Tudor, for a lifetime.

Part II

IRELAND: FROM MUTINY TO MURDER

. . . the hands of the sisters Death and Night, incessantly softly wash again, and ever again, this soil’d world . . .

Walt Whitman, “Reconciliation”

IT IS UNCLEAR exactly when General Tudor first became a part of the Irish war. Though he had kept a diary during the Boer War and diligently recorded his experience on the Western Front, he left no record of his time in Ireland, even though the twenty-three months he spent there redefined his life, his career and, arguably, his personality.

Tudor and Churchill were frequently in touch on the Western Front during critical moments in an evolving Irish crisis in April 1916. It is not unreasonable to speculate that the two old friends, both die-hard imperialists, would have exchanged tactical ideas about Ireland during long discussions about politics and war. Irish independence had been a cause of violent conflict for centuries and had dominated British politics for decades. Easter week that year became a historic flashpoint.

Churchill was still a member of parliament while in uniform and had returned to London on April 19 for a debate on conscription that would inevitably focus on Ireland’s contribution to the Great War. While in London he had dinner on April 24 with Edward Carson, a hard-line Protestant leader of Irish unionists in the British parliament and vehemently opposed to any form of Irish independence. It isn’t hard to imagine what they spoke about. April 24 was Easter Monday, the first day of the rebellion that would define Anglo-Irish politics for all time.

On April 26, two days into the Easter week uprising in Dublin, Tudor commented in his diary that “the papers are full of the Irish

rebellion. We all hope that [Sir Roger] Casement will be hanged.” (And he surely was, in August, after a controversial trial for treason.) 1

Churchill saw Tudor shortly after he returned from London to the front lines the next day, April 27. The timing of the Irish crisis would be difficult for two high-ranking British soldiers, one of them an ambitious politician, to ignore.

As they socialized in the final days of Churchill’s service at the front, brutal British military justice was polarizing Ireland, where fourteen accused rebels were shot by army firing squads in Dublin between the third and twelfth of May. It would soon be obvious to both Churchill and his friend that Ireland’s long campaign for self-determination wasn’t going to lose momentum, as many British politicians had hoped it would during the distraction of the First World War.

After Easter week, 1916, Irish nationalists made ever more provocative demands for a republic, once and for all divorced from Britain, her Empire and her Crown.

Before the Great War, the demand for Irish independence might have been satisfied by some form of Home Rule, perhaps the status of a self-governing dominion, like Canada or Newfoundland. But by 1920, Irish politics were dominated by radical nationalists. The most aggressive independence party, Sinn Féin, even had a military wing: the Irish Volunteers, more widely known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

The Lloyd George coalition government was unimpressed by the popular support for Sinn Féin politicians. Unlike earlier Irish nationalists, they refused to sit in the British House of Commons. Their power, to the pragmatic Lloyd George, was therefore largely symbolic. The violent tactics of the IRA were becoming a problem, however. The government was determined to keep Ireland in a United Kingdom no matter the cost, and it had formulated an aggressive new strategy for defeating the republicans.

Winston Churchill with his second-in-command, Archie Sinclair, in 1916, while serving in the 9th Scottish Division at the Western Front. Churchill Archives

Tudor at the end of the First World War. Courtesy John Davenport

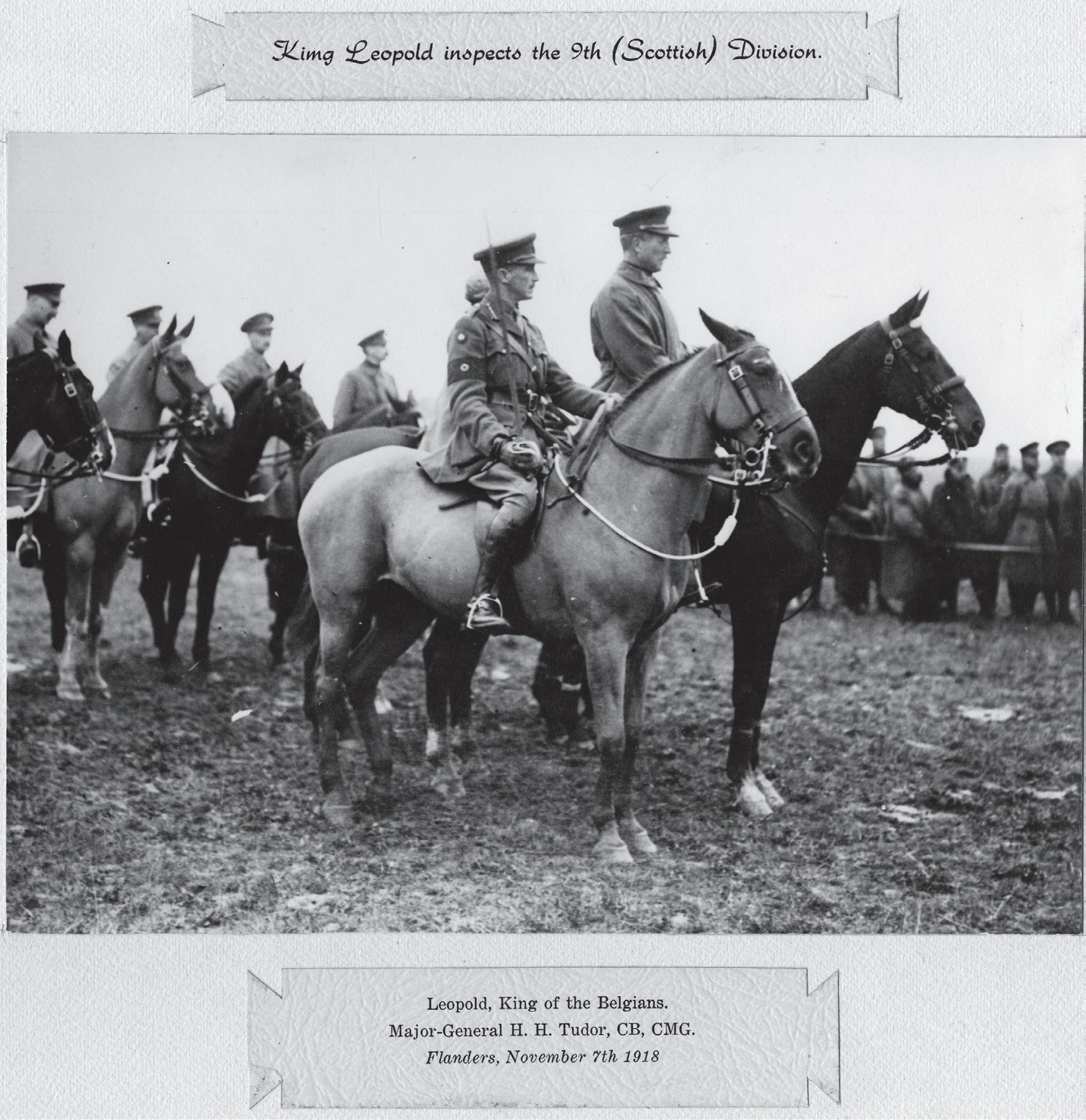

General Tudor and the Belgian king, Albert 1, on November 5, 1918, inspecting Tudor’s 9th Scottish Division at Flanders. (The official photo of the occasion incorrectly identifies the king as “Leopold” and the date as November 7.)

The Rooms, Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador