Chief Editor: Bernard

Co-Editor:

The IAFOR Journal of Literature and Librarianship Volume 14 – Issue 1

Chief Editor: Bernard

Co-Editor:

The IAFOR Journal of Literature and Librarianship Volume 14 – Issue 1

The International Academic Forum

The IAFOR Journal of Literature and Librarianship

Chief Editor

Dr Bernard Montoneri, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

Co-Editor:

Dr Michaela Keck, Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany

Associate Editors:

Dr Murielle El Hajj, Lusail University, Qatar

Dr Fernando Darío González Grueso, Tamkang University, Taiwan

Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan

IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008

Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane

Publications & Communications Coordinator: Mark Kenneth Camiling Publications Manager: Nick Potts

The IAFOR Journal of Literature and Librarianship Volume 14 – Issue 1 – 2025

Pubication date: August 25, 2025

IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2025

ISSN: 2187-0594 ijll.iafor.org

Cover image: The Beauty Of Reality, Pexels https://www.pexels.com/photo/intricate-bronze-statues-on-brick-wall-background-29683380/

The IAFOR Journal of Literature and Librarianship – Volume 14 – Issue 1

Chief Editor:

Dr Bernard Montoneri, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

Co-Editor:

Dr Michaela Keck, Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany

Like Asteroids Spinning through Time and Space: Chronotopicity in 7 The Whole Family

Michaela Keck

Asura Becomes Bishōnen: Decoding the “Shōjo-manga-fication” of 23 Rig Vedic Deities in CLAMP’s RG Veda

Kunal Debnath

Nagendra Kumar

The World of Yōkai: Gods and Demons in Hayao Miyazaki’s 43

Princess Mononoke (1997)

Xinnia Ejaz

Factors Affecting Academic Law Libraries’ Preparedness and 55 Compliance with the Philippine Legal Education System

Willian S.A. Frias

Alvin E. Halcon

Wilfredo A. Frias, Jr.

Short Article –

From Scarcity to Solidarity: Food, Resistance, and Corporate Control 87 in Saad Hossain’s Bring Your Own Spoon

Pritam Panda

Panchali Bhattacharya

Speculative Fiction, the Aesthetics of Discomfort, and Muslim Futurity 95 in Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West

Netty Mattar

Short Article –A New Insight into Anton Chekhov’s Psychological Prose 111

Anna Toom

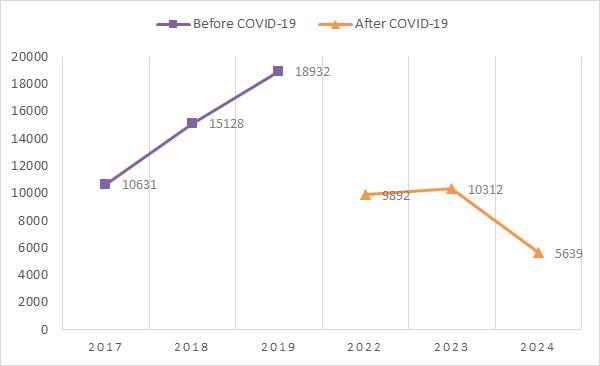

Trends in the Utilization of Circulation Services in University Libraries: 119 Analysis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic

Andi Saputra

Nanik Rahmawati

It is our great pleasure and my personal honour as the editor-in-chief to introduce Volume 14 Issue 1 of the IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship. This issue is a selection of papers received through open submissions directly to our journal.

This is the eleventh issue of the journal that I have edited and the 24th for IAFOR journals, this time, with the precious help of our Co-Editor, Dr Michaela Keck (Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany), and our two Associate Editors, Dr Murielle El Hajj (Lusail University, Qatar) and Dr. Fernando Darío González Grueso (Tamkang University, Taiwan).

We are now 32 teachers and scholars from various countries, always eager to help, and willing to review the submissions we receive. Many thanks to the IAFOR Publications Office and its manager, Nick Potts, for his support and hard work. Also, many thanks to Mark Kenneth Camiling, IAFOR’s Publications & Communications Coordinator.

We hope our journal, indexed in Scopus since December 2019, will become more international in time and we still welcome teachers and scholars from all regions of the world who wish to join us. Please join us on Academia and LinkedIn to help us promote our journal.

Finally, we would like to thank all those authors who entrusted our journal with their research. Manuscripts, once passing initial screening, were peer-reviewed anonymously by four to six members of our team, resulting in eight being accepted for this issue.

Note that we accept submissions of short original essays and articles (1,500 to 2,500 words at the time of submission, NOT including tables, figures and references) that are peer-reviewed by several members of our team, like regular research papers. All are welcome to submit a paper for our regular 2026 Issue (submissions should open in March).

Please see the journal website for the latest information and to read past issues: https://iafor.org/journal/iafor-journal-of-literature-and-librarianship. Issues are freely available to read online, and free of publication fees for authors.

With this wealth of thought-provoking manuscripts in this issue, I wish you a wonderful and educative journey through the pages that follow.

Best regards,

Dr Bernard Montoneri Associate Professor, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

Editor IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship editor.literature@iafor.org

Article 1:

Like Asteroids Spinning through Time and Space: Chronotopicity in The Whole Family

Dr Michaela Keck

Michaela Keck is a senior lecturer at the Institute of English and American Studies at Carl von Ossietzky University in Oldenburg in Germany. She received her doctorate degree in American Studies at Goethe University in Frankfurt and has taught at universities in Taiwan, Holland, and Germany. Her research foci include nineteenth-century American literature and culture at the intersections between literature, visual culture, gender, the reception of myth, and the environment. Further research interests include captivity narratives and African-American literature and culture. She is the author of Walking in the Wilderness: The Peripatetic Tradition in Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Painting (2006) and Deliberately Out of Bounds: Women’s Work Classical on Myth in Nineteenth-Century American Fiction (2017). Among her research articles, which have been published in various peer-reviewed European and international journals, are studies of North American women writers, ranging from Louisa May Alcott to Margaret Atwood.

E-mail: michaela.keck@gmail.com

Article 2:

Asura Becomes Bishōnen: Decoding the “Shōjo-manga-fication” of Rig Vedic Deities in CLAMP’s RG Veda

Mr Kunal Debnath

Kunal Debnath is a Doctoral Research Scholar of English at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee, INDIA-247667. He completed his MA in English from Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University in 2019. His research interests include Anime & Manga Studies, Myth & Archetypal Criticism, Postmodernism, and Popular Culture. He has published papers in reputed journals such as East Asian Journal of Popular Culture (Intellect Ltd.), Literary Voice, and IAFOR Journal of Arts and Humanities. His latest publication is “Fullmetal Alchemist and the hero’s journey: Decoding the monomyth in Hiromu Arakawa’s shōnen masterpiece” which has been published in East Asian Journal of Popular Culture.

E-mail: kunal_d@hs.iitr.ac.in

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6186-9410

Dr Nagendra Kumar

Nagendra Kumar is a Professor of English at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee, INDIA-247667. He completed his PhD in English from Banaras Hindu University in 1998. He is currently working on the project “Surrogate Women,” which is funded by the National Commission for Women. He received the “Outstanding Teacher Award” from IIT Roorkee in 2015. His research interests include Diaspora Studies, South Asian Literature and Culture, Contemporary Fiction, Dalit Studies,

Soft Skills, Modern Literature, Myth & Archetypal Criticism, Posthumanism, Graphic Novel, and Postcolonial Literature. He has published research papers in Partial Answers (JHU), Neohelicon (Springer), Textual Practice (Taylor & Francis), Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (Taylor & Francis), and many other reputed journals.

E-mail: nagendra.kumar@hs.iitr.ac.in

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8292-7947

Article 3:

The World of Yōkai: Gods and Demons in Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997)

Ms Xinnia Ejaz

Xinnia Ejaz is a postgraduate student of Comparative Literature at SOAS, University of London. She has published her research in both local and international journals, as well as short stories and a feature article. Recently, she presented her research on resistance literature at the SOAS Centre for Cultural, Literary, and Postcolonial Studies Conference. Her current research interests include folklore and fairytales, representation of gender in media, and detective fiction. E-mail: 722896@soas.ac.uk

Article 4:

Factors Affecting Academic Law Libraries’ Preparedness and Compliance with the Philippine Legal Education System

Ms Willian S. A. Frias

Willian S.A. Frias is the Law Librarian of De La Salle University and a distinguished leader in the field of library and information science. She earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of the Philippines Institute of Library Science (now the School of Library and Information Studies) and has dedicated over three decades to the profession. A recipient of the 2017 Bursary Award from the International Association of Law Libraries (IALL), she had the opportunity to participate in IALL’s Annual Course in Atlanta, Georgia that same year. As an active law librarianship practitioner, she took part in crafting The Academic Law Library Standards and Guidelines as a member of the Technical Working Group of the Legal Education Board. As the founding president of the Network of Academic Law Librarians (NALL), she is committed to establishing the organization as a respected and recognized professional body in the country. Her advocacy focuses on upskilling academic law librarians to reinforce their role in the Philippine legal education system. She is the immediate past president of the Association of Special Libraries of the Philippines (ASLP) and currently serves as the Assistant Secretary of the Philippine Federation of Professional Associations (PFPA). A strong advocate for research development in the profession, she actively works to enhance the research capabilities of librarians, particularly those in special libraries.

E-mail: willian.frias@dlsu.edu.ph

Mr Alvin E. Halcon

Alvin E. Halcon is the Law Librarian of the Lyceum of the Philippines University (LPU)–Makati and currently the President of the Philippine Group of Law Librarians (PGLL). He has conducted and presented papers in national and international conferences with interests focusing on legal education reform, quality assurance, inclusive librarianship, and indigenous knowledge systems. He has helped organize and lead multiple training programs, most dedicatedly in law librarianship-related forums, such as the Academic Law Librarians Certification Program (ALLCP). Mr. Halcon also contributed to national policy development through his role in the Legal Education Board’s (LEB) Technical Working Group that drafted the 2022 Academic Law Library Standards. He has also been recognized by LPU for excellence in leadership and institutional audit work. His work reflects a strong commitment to advancing legal education, institutional excellence, and empowering underserved communities through access to information.

E-mail: alvin.halcon@lpu.edu.ph

Mr Wilfredo A. Frias, Jr.

Wilfredo A. Frias, Jr. earned his Bachelor’s degree in Banking and Finance from the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) and later completed a post-baccalaureate specialization in Library and Information Science at the Philippine Normal University. He has recently completed and successfully defended his thesis for the Master of Library and Information Science degree. With over two decades of service at De La Salle University, Mr Frias has made meaningful contributions to both its academic and administrative landscape. Throughout his career, he has held various key positions in the library, including Reference Assistant Librarian, Filipiniana Assistant Librarian, and Acquisitions Assistant Librarian. He currently serves as Project Manager of the De La Salle University Libraries, where he leads initiatives focused on improving library services, infrastructure, and user experience. His longstanding dedication to the University reflects a deep commitment to educational excellence, professional growth, and institutional development.

E-mail: wilfredo.frias@dlsu.edu.ph

Article 5: Short Article

From Scarcity to Solidarity: Food, Resistance, and Corporate Control in Saad Hossain’s Bring Your Own Spoon

Dr Pritam Panda

Pritam Panda works as an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Jogananda Deva Satradhikar Goswami College, Assam, India. He has completed his PhD from the University of Lucknow, India. The title of his doctoral thesis is “Re-enactment of Today’s Myths and the Creation of Tomorrow’s Myths in Science Fiction and Cinema.” His research interest focuses on the juncture of technology and indigenous knowledge traditions, specifically from the South-Asian literary perspective.

E-mail: pritampanda2009@gmail.com

Dr Panchali Bhattacharya

Panchali Bhattacharya is an Assistant Professor (English) at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology Silchar, Assam, India. She holds a Ph.D. from the Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. Her doctoral dissertation focused on the revival of green lore in contemporary Northeast Indian literature from the Indigenous women writers’ perspective. She has extensively published her research findings with reputable publishing houses, like Routledge, Springer Nature, Bloomsbury, Lexington Books, and so on. Her research interest lies at the intersection of eco-literature, folk, and Indigenous studies, with a special focus on the South Asian context.

E-mail: panchali@hum.nits.ac.in

Article 6:

Speculative Fiction, the Aesthetics of Discomfort, and Muslim Futurity in Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West

Dr Netty Mattar

Netty Mattar holds a PhD in English Literature from the National University of Singapore, where she currently teaches. Her research focuses on the intersections among speculative literature, science, and technoculture, with a particular interest in issues related to decolonization, trauma, memory, and posthumanism.

E-mail: nmattar@nus.edu.sg

Article 7: Short Article

A New Insight into Anton Chekhov’s

Dr Anna Toom

Anna Toom is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the Graduate School of Education at Touro University, USA. She earned her MS in computer science from the Moscow Institute of Radio Engineering, Electronics, and Automation (1972), her MS in psychology from Moscow State University (1978), and her PhD in psychology from the Moscow State University of Management (1991). She has 50 years’ research experience and 48 publications. The psychology of fiction literature and film arts has always been a subject of special interest in Anna Toom’s research and teaching activities. She took part in many international conferences with her presentations on the psychological/psychoanalytic analysis of poetry (E. Dickinson, M. Tsvetaeva, P. Antokolsky), prose (A. Chekhov, H. C. Andersen, M. Bulgakov, A. Belyaev, N. Nosov), and films (I. Bergman, St. Kramer). As an expert in integrative education, Dr. Toom has been creating new instructional methods to teach psychology, combining literature and film arts with information technology for explaining complicated ideas and concepts. In Anna Toom’s Virtual Psychological Laboratories, current and prospective schoolteachers study theories of child development in dialogue with interactive computer programs and based on the best samples of the world's children's literature.

E-mail: annatoom@gmail.com

Article 8:

Trends in the Utilization of Circulation Services in University Libraries: Analysis Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic

Mr Andi Saputra

Andi Saputra is a lecturer in the Department of Information, Library, and Archives at Padang State University. He completed his master's degree in information systems at Diponegoro University, Indonesia, in 2014. Currently, he is continuing his doctoral studies at Padang State University. He is active in writing books and conducting research in the field of library and information science, especially digital libraries and the implementation of information technology in libraries.

E-mail: andisaputra@fbs.unp.ac.id

Mr Nanik Rahmawati

Nanik Rahmawati currently works as an Associate Expert Librarian at the UPA Library of the University of Bengkulu. He completed his Master's degree in Library Science Management at Gadjah Mada University (UGM), Indonesia, in 2008. He is active in conducting research in the field of library and information science.

E-mail: nanikr@unib.ac.id

Michaela Keck

Carl von Ossietzky University, Oldenburg, Germany

Devised by William Dean Howells as a jointly written, serialized novel about a middling American family and edited by Elizabeth Jordan, The Whole Family (1907–1908) has been defined above all by the contention among its twelve authors rather than their collaboration. Scholars have explored the discordant voices within and outside of the novel, including the writers’ outspoken critique of their peers’ differing literary styles, formal and thematic choices as well as the diverging interests of writers, editors, and publishers. Also, the authorial discord has come to represent the American family in crisis at the beginning of the twentieth century, a discord heightened by the diverse individual and gender perspectives that the novel opens up. This study redirects our attention to the text as a collaborative project aimed at the family novel in American modernist literature. By drawing on Mikhail M. Bakhtin’s notion of chronotopicity, it demonstrates that the authors of The Whole Family jointly rework the traditional family idyll into an exhilarating composite family portrait, whose individual chapters experiment with multitudinous spatiotemporal perspectives, individual space-time experiences, and life sequences. At the same time, the chapters in themselves grapple with the tensions resulting from the modernist experience of multiplying time, space, and identity while the American family likewise undergoes major discursive changes.

Keywords: chronotope, Mikhail M. Bakhtin, collaborative novel, The Whole Family, American literary modernism

The rivalries and bickering among the twelve authors of The Whole Family has become a defining feature of this twentieth century American collaborative novel. Published in monthly installments in Harper’s Bazar from December 1907 through November 1908, the novel opens with a chapter by one of the most significant arbiters of literary taste in America at the time, William Dean Howells; then follow the contributions by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Mary Heaton Vorse, Mary Stewart Cutting, Elizabeth Jordan (who also orchestrated this venture as the newly recruited editor of the New York women’s magazine), John Kendrick Bangs, Henry James, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Edith Wyatt, Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews, Alice Brown, and Henry van Dyke. Howells, who established the main plot lines and issues, and who introduced the family patriarch, Cyrus Talbert, envisioned the collaboration as both a serious and “fun” (as cited in Howard, 2001, p. 13) literary project, in which each writer was to contribute a chapter narrated and focalized by a different family member. With an eye to the target audience of Harper’s Bazar, and to facilitate the cooperation among the writers, he suggested a common narrative thread, namely that “[t]he family might be in some such moment of vital agitation as that attending the Young Girl’s engagement, or pending engagement, and each witness could treat of it in character” (as cited in Howard, 2001, p. 13).

It did not take very long, however, until tensions arose about the meanings of a normative, middling family. Also, gender-related issues as well as the differing literary conventions that male and female writers were expected to fulfill caused contention (Kilcup, 1999, p. 9). Freeman’s second chapter, e.g., directly launched a first “battle over” (Howard, 2001, p. 19) the family’s old-maid aunt. The subsequent chapters added yet other interpretations of this unorthodox figure, most of them to depotentiate the threat of an attractive, sexually experienced, and independent single woman (Baur, 1991, pp. 114–120). Moreover, some writers openly expressed their disapproval in their correspondence with Jordan.1

The contentious group of twelve has, therefore, often been compared to the American family in crisis at the turn of the twentieth century. Defined by alienation and fragmentation, it no longer constitutes a close-knit collective. Indeed, the contentious cooperation of these authors demonstrates in itself “the struggle between the individual and the family as a whole” (Beal, 2016, p. 45) at the same time as it constitutes a larger social argument “over converging models [of the family]” (Howard, 2001, p. 20). While scholars agree that, as a composite text and as an important sociocultural contributor to the discursive construction of the American family, the novel oscillates between discordance and unity, Susanna Ashton (2001) reminds us that the tensions in the individual chapters themselves point up the importance of multiplicity in modernist literature: “The success of the project was dependent upon acknowledgment of cacophony as harmonic. Coherence was achieved because of competing visions, not despite them” (p. 55). This article continues exploring these very tensions within exemplary chapters of The Whole Family. It focuses on the hitherto neglected chronotopicity that shapes not only

1 Phelps, for instance, considered James’ chapter as “long and heavy” (as cited in Ashton, 2001, p. 68). James, in turn, disliked Phelps’s sentimental writing. Even more scorchingly, he judged Wyatt’s chapter on the mother as a “small convulsion of debility” (as cited in Howard, 2001, p. 248). For a helpful introduction to the collaboration of The Whole Family and serialized productions related to authorship, art, and commerce, see Howard, 2001, pp. 13–30; on the tensions and competition during the collaborative process, see Ashton, 2001, pp. 51–78.

the identities of the various family members and their narrative perspectives, but also individual chapters’ contributions to the larger composite family portrait. On the one hand, the special form of the collaborative novel challenged writers to produce a vignette that would “‘stand up’” (Ashton, 2001, p. 62) to and stand out among the others in a format that, once submitted, was out of their hands; on the other hand, it offered them an opportunity for experimenting to their heart’s content with the crafting of a character who was at once related to a white middle-class family of America’s East coast yet also different from the rest of its members. As the analysis will demonstrate, the result of these collaborative efforts is an exhilarating array of differing chronotopes and chronotopic identities, both in the chapters themselves and in the novel as a whole.2 Indeed, the juxtaposition of all these multitudinous time-space constellations enhances the novel’s modernist “cacophony” (Ashton, 2001, p. 55) of voices, chronotopic identities, and points of views.

According to Mikhail Bakhtin (1981), the family as a conglomerate of alienated individuals rather than a cohesive unit is central to the changes and developments in the chronotopicity of “the family novel and the novel of generations” (p. 231) as which we can classify The Whole Family formally and thematically. As a composite text, it focuses on family matters and provides ten intimate portraits narrated by characters belonging to three different generations: Grandmother Evarts; the parent generation of the Talbert family; and their children. These portraits are framed by Howells’s and Henry van Dyke’s opening and concluding chapters, respectively, each narrated by members of the extended family (if we include the neighbor Ned Temple as such).

The chronotopicity of the family in the modern novel is, as Bakhtin (1981) observes, subject to “a radical reworking” (p. 231) of the traditional family idyll with its “immanent unity in folkloric time” in a “little spatially limited world” (p. 225). Here, the lives of different generations are rooted in the same familiar place, and temporal boundaries tend to blur into repeating cycles of seasonal labor, human births and deaths. At the threshold to modernism, the idyllic elements are “scattered sporadically throughout the family novel” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 233), whereas the dominant theme becomes that of the destruction of the close-knit family unit. Now, time is no longer a collective experience but disperses into manifold “individual life sequences” or “series” (Bakhtin, 1981, pp. 214–215) that involve different identities, values, and narratives that take on an interior, private character.

In The Whole Family, this traditional family idyll still features prominently in Grandmother Evarts’s individual life sequence written by Mary Heaton Vorse. Because Grandmother Evarts still clings to the cyclical rhythms of life within, as Bakhtin (1981) calls it, “the strictly delimited locale” (p. 229) of the nuclear family, Peggy’s engagement makes the grandmother’s heart ache as if it were her own troubled love affair. Generally, she sees traditional family life

2 Although I address all chapters at least briefly, an in-depth analysis of each and every chapter is beyond the scope of this study.

and values threatened by degenerating moral principles and lifestyles caused by the industrial revolution, coeducation, and new ideas about man- and womanhood. On the one hand, she has adapted well to the fact that medicine and psychology have replaced the curative function of religion;3 on the other hand, she construes the “vanity” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 74) of the unmarried Elizabeth and her, therefore, inappropriate “comings and goings” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 68) into a variant of the old story of Eve’s sinful fall as the root cause for the disintegration of the family. In this way, Vorse’s chapter carries the “mischief” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 79) and intrigues of urban society right into the heart of the Talbert family. Before I examine the ways in which the chapters’ heterogeneous spatiotemporal configurations shape the individual characters’ sense of self and interiority vis-à-vis the family in more depth, Bakhtin’s (1981) chronotope and its relevance for identity formation will be outlined in more detail.4

Derived from the Greek chronus (time) and topos (space), Bakhtin’s (1981) chronotope is never a mere backdrop in literature but constitutive of giving concrete shape and “flesh” (p. 84) to the physical and spatial representations of the novelistic world. It is, in fact, the chronotope that enables us “to ‘see’ time in space” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 247) and observe how time “thickens” and becomes “artistically visible” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 84). According to Bakhtin (1981), “[a]ll the novel’s abstract elements—philosophical and social generalizations, ideas, analyses of cause and effect—gravitate toward the chronotope and through it take on flesh and blood, permitting the imaging power of art to do its work” (p. 250). In this way, a novel’s world is established by numerous chronotopes which, however, are always “specific to the given work or author” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 252). At the same time, they relate to each other in manifold ways. Bakhtin (1981) explains that even though it “is common for one of these chronotopes to envelope or dominate the others,” they are also “mutually inclusive, they co-exist, they may be interwoven with, replace or oppose one another, contradict one another or find themselves in ever more complex interrelationships” (p. 252) with each other.

Importantly, Bakhtin’s (1981) notion of the chronotope relates to a universe that comprises multiple simultaneous possibilities and reference points with regard to timespace configurations as we also find them in The Whole Family. Indeed, we can take the comment by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s character as a pertinent expression of the differing subjective perspectives and spatiotemporal life-series when she states that she and her husband “are like … asteroids spinning through space, neither knowing the other’s route or destination” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 192). As a result, the Talbert family becomes a novelistic universe that is, to speak with Jonathan Stone (2008), “composed of [multiple] independent, autonomous worlds” (p. 415).

3 Rather than the Bible, Grandmother Evarts reads William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience to take her mind off family troubles (Howells et al., 1908, p. 70). Likewise, she unburdens her mind to Dr. Denbigh rather than to a priest (Howells et al., 1908, p. 77).

4 With this outline, I do not aim to provide a general introduction to Bakhtin’s theorizing in order to trace and capture his (changing) thought regarding chronotopicity. Rather, and for the purposes of this study, I merely delineate the main ideas, its relevance to the (modernist) family novel, and identity construction.

Bakhtin (1981) also considers the chronotope as central to identity and its cultural representation, stating that “as a formally constitutive category [it] determines to a significant degree the image of man in literature as well. The image of man is always intrinsically chronotopic” (p. 85). In more contemporary terms, we can explain this idea as the discursive social constructedness of the identity and sense of self of a fictional character or a social group within specific timespace configurations and socio-cultural contexts. Hence, chronotopes can produce and reproduce as well as explore and counter ideologies, values, and sociocultural scripts that empower and regulate, enable and constrain characters as they move through their novelistic universe.

To further elucidate the interrelation between chronotopicity and identity, Jan Blommaert and Anna De Fina (2016) point to Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron’s The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture from 1979. In their study of the “timespace of student life” (Blommaert & De Fina, 2016, p. 3), the French sociologists observe that students’ lives are temporally organized according to the academic calendar with its semester courses, lectures, and exams, at the same time that, spatially, students move around the campus between seminars, lecture halls, and libraries, but also in specific urban neighborhoods where they frequent their favorite eating places or various cultural events like dances and concerts. Bourdieu and Passeron (1979) emphasize, however, that student identity is only temporarily grafted onto the much deeper-rooted sociocultural individual and group identities that the students already bring with them to their life and time at university (pp. 35–36).

For Blommaert and De Fina (2016), the study illuminates the multilayered as well as dynamic chronotopicity of social identities as they are represented in the novelistic “description[s] of the looks, behavior, actions and speech of certain characters, enacted in specific timespace frames” (p. 5). Moreover, chronotopic identities come with “specific patterns of social behavior [that] ‘belong,’ so to speak, to particular timespace configurations,” which, “when they ‘fit’ … respond to existing frames of recognizable identity, while when they don’t they are ‘out of place,’ ‘out of order’ or transgressive” (Blommaert & De Fina, 2016, p. 5).

These explanations are relevant to The Whole Family in so far as Peggy’s engagement to Harry Goward is a result of her immersion into the specific timespace of an American coeducational college. Her engagement temporarily exacerbates the usual differences among the Talberts; and although it shows her as an educated young woman with choices that she, at least in part, actively pursues, her identity and belonging to New England’s white suburban upper class do not change. She does, however, depart from the American suburban life that her mother and grandmother live. The older generations’ lives are symbolized in the Victorian family home with its “mansard-roof” and “square tower in front,” built according to “[t]he taste of 1875” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 9). Here, the days are structured according to a schedule of regular housekeeping, meals, children, and leisure.

Peggy’s departure to Europe as newlywed Mrs. Stillman Dane suggests a future life apart from the traditional Victorian family unit, but remains ambiguous regarding her very own status as professional teacher. This is because, repeatedly, different chapters suggest that Peggy will subordinate some of her professional ambitions to the marital life with her husband, who shows some reluctance regarding her professional ambitions. In fact, in the later chapter by Alice Brown, Peggy’s determination to “make [her] own life” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 283) and “to have a profession” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 292) is repeatedly undermined by her own appeal to and dependence on Stillman’s male authority in questions of profession, love, and marriage. Hence, Peggy’s departure from the family harbors the contradictions in keeping with the identity of what Howard (2001) identifies as “the sometimes-new woman” (p. 158), whose submission and passivity as a true woman combines with the new woman’s active choices in education, marriage, and profession.

Howells’s opening chapter, “The Father,” already invests Peggy’s identity with the “syncretism” (Howard, 2001, p. 160) of old and new ideologies of womanhood by placing her inbetween the contrasting timespace configurations of the different generational biographies and histories of parents and children. Ned Temple, the neighbor, and Cyrus Talbert, her father, note that she comes after him in her robust physical “constitution” and looks; whereas in “temperament and character” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 25) she comes after her mother, the “ideal mother” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 18) and obedient, submissive wife who neither openly contradicts nor even adds to her husband’s ideas. The men, then, associate Peggy with the parent generation, and specifically with Ada Talbert’s domestic routines as wife and mother.5 Still, they acknowledge Peggy’s student life and coeducation, which indicates a chronotopic identity that surpasses that of her mother and links Peggy with the young generation of new men and women, even if the underlying deep-seated national, racial identification and class affiliation of their family lineage remains, as Bourdieu’s and Passeron’s (1979) study reminds us (pp. 35–36).

In contrast to Howells’s opening chapter, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s subsequent chapter of “The Old-Maid Aunt” narrates the existence of multiple individual chronotopic selves. In Eastridge, we are told, Elizabeth takes to the “rôle” of “the old-maid aunt” to fit the identity that the family and suburban society have assigned her according to a premodern belief system harkening back to “the prophets of old” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 31), a belief system Elizabeth herself condemns as “unsophisticated and fatuous” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 32). Meanwhile, her actual self observes all this with great detachment and amusement from a position located in a “present” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 33) timespace “outside Eastridge” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 31) that neither marginalizes nor patronizes single women. Here, she identifies as an

5 While Grandmother Evarts clings to Victorian family space-times, Ada identifies with the suburban family world of her husband Cyrus. This world is characterized by a reciprocal relation between the economic and the private domain so that the wife is as much out and about as the husband enters into and determines life at home. Ada’s experience of time and self, Edith Wyatt’s chapter (“The Mother”) demonstrates with some irony, is as much defined by its cyclical household routine as it is shaped by a breathtaking succession of activities that results in a highly fragmented sociality and identity. Besides her regular roles as mother, wife, daughter, or family nurse, she also finds herself in such other roles as that of a chauffeur, a visitor, or a board-member of the local library.

attractive, stylish, still young-looking, and proud single Lily who, in turn, condescends to the “pathetic” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 35) residents of her hometown. To her, Peggy is still a “child” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 31) who possesses beauty but little intellect and knowledge of the world despite her coeducation and engagement, while she, Lily, feels misunderstood, even offended, by her family’s incredulity that a young man like Harry, Peggy’s fiancé, could be in love with her.

At times, Lily becomes entangled with yet another—albeit minor—self steeped in what Bakhtin (1981) calls the “extratemporal hiatus” (p. 90) of “adventure-time” (p. 87; emphasis in original), which lacks an identity rooted in specific sociohistorical circumstances. This additional self transports her to the “ancient history” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 47) and strange world of love and romance with Lyman Wild. Looking back, she describes her former love affair as a “tragedy” that “was never righted” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 44), an experience from which she wants to protect Peggy. Notably, the combination of Elizabeth/Lily as an unreliable, homodiegetic narrator and the mixture of self-irony and sincerity in her narrative open up a potentially satirical reading of her figure (Howard, 2001, p. 171), which is heightened by the anachronisms resulting from the entanglements of different chronotopes and identities. For example, Elizabeth/Lily casts her past in heroic terms as “wandering[s]” and muses that her former lover now leads a life “in the Far East, with a harem” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 47). She herself, beleaguered by the smitten Harry, grandly “ar[i]se[s] to the occasion” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 42) and notes with comic relief that he can neither carry her away in “a gallant steed” nor in an “automobile” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 43). The chapter ends with the outcome of the romance and domestic drama—both amounting to a veritable “deluge” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 56)—still pending, while Elizabeth/Lily braces herself for more heroic deeds on behalf of Peggy’s future happiness in love and marriage.

Similarly, Phelps’s chapter about Peggy’s older sister towards the end of the novel (“The Married Daughter”) can be read as a humorous portrait of the bossy, meddlesome Maria or “Meddlymaria” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 186). Like Elizabeth/Lily, she casts herself in the role of the female protector who courageously rescues “poor little Peggy” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 188) while also looking down on her as a young girl whose looks exceed her intellect and good sense (Howells et al., 1908, p. 193). Although Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s train travels from her home in Eastridge to the boarding houses and streets of New York dominate in search of Peggy’s fiancé Harry, Phelps interrelates her character’s individual life-sequence more pronouncedly and consistently with elements of adventure-time than Freeman does with Elizabeth/Lily. More specifically, Phelps draws on the chronotope of the “miraculous world in adventure-time” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 154; emphasis in original) of chivalric romance, which Bakhtin (1981) describes as a characteristically emotional “subjective playing with time” (p. 155; emphasis in original) that hyperbolizes and distorts timespace configurations. Indeed, Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s narrative animates, bends, and plays with spacetime in innovative and creative ways.

On the one hand, in Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s world time “thickens” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 84) in a fast-paced chronology of her swift actions and successful time management: she follows the

time-tables of the trains; marks her entries in her travelogue with temporal references—“It is now ten o’clock”; “Eleven o’clock”; “‘The Sphinx,’ New York, 10 P.M.”; “Twenty-four hours later” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 191; 193; 196; 204; emphasis in original); and she receives and dispatches various letters and telegraphs. On the other hand, Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s world is not miraculous in a divine sense but wondrous because it is filled with sudden temporal ruptures and hiatus in the form of chance encounters, unlikely opportunities, and incidents beyond human control. Events happen suddently yet also simultaneously and apart from each other so that humans, trains, and messages cross paths as if magnetically attracted to each other, or passing each other by “like … asteroids spinning through space, neither knowing the other’s route or destination” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 192), as she notes herself.

Like time, space also comes alive in Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s wondrous world: she finds the family home “in its usual gelatinous condition” without “a back-bone in it, [and] scarcely an ankle-joint to stand upon” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 188); she and Tom kiss good-bye “by electricity” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 192); Aunt Elizabeth “rolls” into the New York boarding house “like a spent wave,” leaving “her weeds upon this beach” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 192); whereas the metropolis “strikes [Maria] on the head like some heavy thing blown down” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 204). Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s strange universe perforce threatens with alienation and nihilism, were it not for the contagious as well as restorative humor of Doctor Denbigh. It is his and Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s laughter at the absurdities of their adventures in the metropolis that forges some form of community, for example, when other family members gravitate by sheer coincidence toward the group that escorts Maria/Meddlymaria from the hotel named “The Sphinx” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 206) to—what irony!—a hotel called “The Happy Family” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 208). Indeed, their merriment alleviates the uncertainty of a world that ultimately cannot be managed or controlled.

Henry James’s chapter about Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s brother shows Charles Edward responding to the absurdities of life and his estrangement from the family by writing in his diary rather than by taking action. In so doing, he attempts to make sense of the events and to re-gain mastery over his life. As he puts it: “I had really heard our [i.e. Lorraine’s and my] hour begin to strike …” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 174). In contrast to Phelps’s chapter about Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s travels through a strange world, James’s pendant of “The Married Son” reveals above all Charles Edward’s interiority. Seated at his desk writing, re-reading, interpreting, and arranging past events in light of present circumstances, he moves through time and space in his mind and psyche in a stream of conciousness indicated by numerous em-dashes, exclamation marks, and side remarks added in brackets. Here, time branches out and multiplies. In the first half of the chapter, the past, present, and future commingle and “thicken” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 84) in the daily monotony of Eastridge’s business and social life, which he and Lorraine do their utmost to counter by not fitting their parents’ and grandparents’ tastes and strict daily routines. But time also becomes visible in the relationships with other family members, specifically that with his mother, whom he plans to rid of “the deadly Eliza” at the

same time as he vows to “save little pathetic Peg[gy]” and “whisk [her and Lorraine] off to Europe … for a year’s true culture” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 176).6

Mentally and psychologically, Charles Edwards likewise expands into numerous, conflicting selves and identities. He prides himself that his artist self is unquestionably out of place in his daily work at the parental company and yearns for Europe, which to him is “the very antithesis of Eastridge” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 180). Meanwhile, he nurtures his Oedipus complex. Deeply resentful of his father’s patriarchal role, on the one hand, he admits that he “dream[s] at times” of being “recognized” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 166) as a male authority, on the other. In his need to be considered a force to be reckoned with among the family, and despite his companionate marriage with Lorraine, he clings to a Victorian past when women—here Peggy—ought to “be kept for the dovecote and the garden” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 162) rather than being educated into a woman with her own mind, desires, and ambitions.

In the course of Charles Edwards’s mental, psychological outpourings, however, there is a noticeable shift in space and temporality. Once he envisions himself as the heroic agent who will resolve the family crisis with one genial stroke that “save[s] poor Mother” and “little pathetic Peg” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 176), while also releasing Lorraine and himself from the grip (and potential punishment) of Eastridge’s insularity, he resorts to what Ronald Schleifer (2000) calls “an aesthetics of accumulated moments” (p. 55). His experiences begin to “multiply” and “shine out in as many aspects as the hues of the prism” and “in all the dimensions” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 167) until they become “extraordinary moments” amounting to a “cluster of documentary impressions” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 171). In these unique moments, Charles Edward envisions himself transforming from the family’s metaphorical captain at the ship’s helm into a New York driver “of trolley-cars charged with electric force and prepared to go any distance” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 168), even if the ultimate destination in futurity—Paris—is still far away and the journey uncertain. Increasingly, he defines his chronotopic experience in terms of speed and fast approaching junctures, bringing about “flash[es]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 173) of knowledge and “glimmer[ing]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 175; 176) opportunities, an exhilarating “rush” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 174) and the “rich thrill” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 180) of the roar and glitter of the metropolis:

I roamed, I quite careered about, in those uptown streets, … I felt, I don’t know why, miraculously sure of some favoring chance and as if I were floating in the current of success. I was on the way to our reward, I was positively on the way to Paris, and New York itself, vast and glittering and roaring … was already almost Paris for me … (Howells et al., 1908, p. 180).

6 Charles Edwards shares his disidentification with the traditional family with his wife Lorraine. Mary Stuart Cutting’s chapter (“The Daughter-in-Law”) represents Lorraine’s anti-domestic stance that, paradoxically, is anchored in the domestic regime she defies. Lorraine, therefore, does not perform the role of Peter’s the name she gives Charles Edward to spite family traditions wife, but the roles of companion, fellow artist, and lover. Accordingly, she embraces irregularity, spontaneity, and improvisation. As June Howard has persuasively argued, her refusal to adhere to the family’s spatiotemporal routine unites Cutting’s with James’s chapter (2001, pp. 138–151).

Caught up in and energized by the intense, rapid pulse and noisy shine of metropolitan timespace and motion, Charles Edward is “uplift[ed]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 180) and vitalized to the point of becoming a powerful predator deciding over Harry’s future: “I hovered there—I couldn’t help it, a bit gloatingly—before I pounced; … he waked up … to the sense that something natural must happen …; and I was simply the form in which it was happening” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 183; emphasis in original). The mixture of nature and fate echoes Bakhtin’s (1981) chronotope of the “miraculous world in adventure-time” (p. 154; emphasis in original) of chivalric romance with its subjective, emotional hyperbolization and “playing with” (p. 155; emphasis in original) timespace figurations as we have seen it also in Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s narration. In contrast to her, however, Charles Edward’s evident thrill at being part of a chronotopical force beyond human control signals his sense of belonging in the noisy, fastpaced flashes of life in the cosmopolitan wilderness as opposed to his role of the son and brother in the silent, dark, and monotonously insular suburban Eastridge.

Updating the Traditional Family Idyll for the American Youth: Jordan’s and Andrew’s Perspectives on Early Twentieth Century Suburban Homelife

The individual life-series of the two youngest Talberts, Alice (“The School-Girl”) and Billy (“The School-Boy”), written by Elizabeth Jordan and Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews, respectively, update the traditional family idyll into the white middle-class homelife and upbringing of early twentieth century suburban America. With their homodiegetic child narrator-focalizers, the chapters retain the family’s limited circumference and familiar locale to some degree as they intertwine the timeflow of the present with a heavily gendered adventure-time. Alice finds her thrills in the troubled love affairs of her female relatives as she moves inbetween their different homes and interiors, whereas Billy’s narrative echoes Huck Finn’s rejection of domesticity, education, and socialization. Andrews’s humorous portrait of Billy’s preference for an uncivilized, manly life along the river invokes a prelapsarian spacetime cut off from the present and reminiscent of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884/1885 in the USA), but avoids the racial complications that Twain’s novel confronts. Like Twain, however, Andrews directly, to borrow an expression from Schleifer (2000), “pressur[es] the present moment” (p. 8) by opening the chapter with the young boy’s stream of consciousness:

Rabbits.

Automobile. (Painted red, with yellow lines.)

Automatic reel. (The 3-dollar kind.)

New stamp-book. (The puppy chewed my other.) (Howells et al., 1908, p. 240)7

7 Apart from Andrews and James, John Kenrick Bangs employs stream of consciousness as a narrative mode as well. In characteristic humorist fashion, his chapter about Tom Price, Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s husband (“The Sonin-Law”) defines him as a somewhat pompous lawyer who seeks to establish himself as the moral anchor of the family yet finds himself severely challenged by Elizabeth’s/Lily’s single and sexually active lifestyle. While Tom’s interior monologues show his awareness of an atomic age in which even his heart can fly into “myriad atoms” (Howells et al. 1908, p. 134) and “facts” flash through his brain “like the quick succession of pictures in the cinematograph” (Howells et al. 1908, p. 139), he nevertheless clings to the idea of an essential self, unwilling to embrace an identity beyond that of the lawyer, husband, or son-in-law.

In contrast to Andrews’s listing of Billy’s thought fragments, which includes all kinds of treasures—of the outdoors, male status symbols, and games—Jordan’s chapter humorously portrays Alice as trying, and failing, to make sense of events through her reading and imagination. Indeed, her “receptive min[d]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 105) commands over a large amount of stories, which she lumps together as indiscriminately as she discloses family matters.8 Especially the latter earns her the nickname Clarry after Eastridge’s local daily paper, the Clarion Call.

The first half of the chapter in particular intermingles the flow of the present with a fictional past until, unsurprisingly, Alice takes on the role of the heroine of her very own narrative, “‘plann[ing] my course of action,’ as they say in books” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 111). From this moment onwards, she is on a mission to restore Peggy’s happiness by retrieving the letter her fiancé directed at Elizabeth/Lily. The second half of the chapter draws on the “chronotope of the road” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 243; emphasis in original) and its random encounters with people in the heroine’s own, familiar territory. On the one hand, and notwithstanding her conflation of fact and fiction, for Alice/Clarry family life still plays out in a limited locale with its daily routines at school and at home, which invokes the traditional family idyll; on the other hand, her hometurf is the American suburb with its orderly, white middle-class propriety, where the lawns of the family homes sprawl out onto the sidewalks and streets. And although she moves mostly within the immediate vicinity of school and the different household interiors, it is also a world in which “trolley-car[s]” and “bicycle[s]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 114) speed up people’s travels and her own adventurous mission, as does the fast-paced communication system of local newspapers, letters, and “telegram[s]” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 106). Only once does she venture into Billy’s favorite outdoor haunt along the river, an encounter that she casts in terms of crossing into foreign territory where time is arrested, “dirt and degradation” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 115) as well as forgetfulness reign.

In light of Alice’s/Clarry’s random conflation of fictional with actual events, her remark to the readers—“you can dimly imagine the kind of time I have” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 101; emphasis in original)—proves highly ironic. Similarly, her declaration that she will piece “together [the secrets of the individual family members] like a patch-work quilt” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 104) humorously inverts women writers’ common use of the quilt metaphor as a community-building practice and art “firmly grounded in the details of daily life” (Shepard, 2001, p. 4)—and we may add, time and space. In fact, by first misreading and then stiching the family members’ multiple life-sequences into what can be called her very own “‘crazy quilt’ style” (Shepard, 2001, p. 6) that does not distinguish between fact and fiction, Alice/Clarry further inflames the misunderstandings and quarrels within the family. Even so, I want to suggest that the chapter’s tongue-in-cheek inversion of the patchwork quilt metaphor still captures important elements of modernist timespace experiences of estrangement and fragmentation at the same time as it comments on the composite production of the collaborative family novel.

8 Alice’s/Clarry’s reading matter ranges from the Bible to Romantic poetry, fairy tales, Gothic novels, historical plays, and novels.

According to Suzanne V. Shepard (2001), from the early nineteenth to the early twentieth century, women’s patchwork quilt fiction shifted from what was known as the “log cabin quilt” (p. 11) with its emphasis on the central unit of the house to the pattern of the “album quilt” (p. 13) with its stress on fragmentation and the loss of a close-knit community. With her chapter on Alice/Clarry, Jordan revises the characteristically “‘elegiac’” (Shepard, 2001, p. 117) prose of the album quilt into a humorous tone, but likewise accentuates the multiplication of diverse chronotopic identities within a family whose members feel increasingly alienated from each other. The individual patches of the quilt, then, much like each vignette of the collaborative novel, contain distinct chronotopical universes or “temporalized ‘truth[s]’” (Schleifer, 2000, p. 9) which, in turn, shape the subjective consciousnesses and identities articulated within them. Given Alice’s/Clarry’s child perspective, the metaphor of the patchwork quilt indicates the still awkward, naïve, and, due to her inability to distinguish between fact and fiction, misguided quilting and text production. At the same time, her point of view also prefigures the modernist rejection of realist mimesis, albeit in a humorous manner.

In contrast to Jordan, Alice Brown draws on sentiment rather than humor. Notably, she ends her chapter about Peggy, the younger Talbert daughter’s individual life-sequence, on a threshold chronotope, i.e. the staircase of the Talbert home where Peggy bids good-bye to Elizabeth/Lily. According to Bakhtin (1981), the threshold chronotope and related ones like the staircase are “highly charged with emotion and value” and “connected with the breaking point of a life, the moment of crisis, the decision that changes a life (or the indecisiveness that fails to change a life, the fear to step over the threshold)” (p. 248). Here, time is “instantaneous; it is as if it has no duration and falls out of the normal course of biographical time” (Bakhtin, 1981, 248). Indeed, Peggy’s and Elizabeth’s/Lily’s tear-filled good-bye intermingles the sadness of their parting with Peggy’s new-found love for Stillman Dane. It also signals the women’s determination to become professionals in a similar, and if we think with William James (Henry James’s brother) even related field: Elizabeth embarks on a career as a spiritualist medium; Peggy on that of a psychology professor. Spatially, their encounter is removed from the characteristic chronotopes of the family idyll—nature and the family table (Bakhtin, 1981, pp. 225–26; 227)—signalling their momentous break with a life dedicated to domestic work.

For Peggy’s actual departure from her family in the final chapter (“The Friend of the Family”), Henry van Dyke employs the heterotopia of the ship. He places the newly-weds who travel together with the artist couple, Charles Edward and Lorraine, on the steamer with the telling name Chromatic, a reference to the heterogeneous simultaneity of multiple colors and/or musical notes and, thus, to heterotopia. Indeed, according to Cesare Casarino (1995), the “paradoxical symbiosis … of sameness and difference” (p. 4), is a defining feature of heterotopias, enabling the association of incompatible spaces with each other in the “simultaneity” (p. 4) and “rapid succession” (p. 11) that we know from looking at “holograms”

(p. 4). In holograms as well as in heterotopias, Casarino (1995) explains, we can behold “a series of parallel representational planes” (p. 11) that exist in a kind of additive overlay although each of these representational layers is also “self-contained” (p. 11). Moreover, as Foucault (1986) so famously posited, heterotopias resemble “counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which … all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted” (p. 24). And while the ship always strives to be an “autarchic and monadic” (Casarino, 1995, p. 3) spacetime configuration away from land, it is never fully separate in that it represents, contests, and reconfigures it. As with space, heterotopian time configurations likewise involve the simultaneity of time or “multiple temporalities at work” (Rankin & Collins, 2017, p. 230) at the same time as processes of becoming and the “suspension and inversion of fixed notions of time” (p. 226) indicate a consistent temporal reconfiguration and reordering.

Notably, van Dyke’s concluding paragraphs mention “the music-room” and “the dining-salon” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 314) of the Chromatic, indicating the representation as well as rearticulation of the home and the family.9 Although the Chromatic leaves these spaces intact, it celebrates the party’s triumphant exodus from American family and home life in Eastridge by arranging the travel group in a dynamic pyramid that bears striking parallels to Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting Liberty Leading the People (1830), 10 with which he commemorated the end of the monarchy by the July Revolution:

Charles Edward and Lorraine were standing on the hurricane-deck, Peggy close beside them. Dane had given her his walking-stick, and she had tied her handkerchief to the handle. She was standing up on a chair, with one of his hands to steady her. Her hat had slipped back on her head. The last thing that we could distinguish on the ship was that brave little girl, her red hair like an aureole, waving her flag of victory and peace. (Howells et al., 1908, p. 315)

Peggy, whose red hair invokes the Phrygian liberty cap, is cast into the role of Liberty waving her victory flag. Yet the mention of peace ironically contrasts her with the figure of the French Liberty bloodied from the fight in the streets of Paris. Still, Peggy’s departure from the family also signals a historical caesura, namely that of twentieth century American women’s desires for expanding their lives and work—including their participation in American empire-building and capitalist expansion—outside of the home. On the Chromatic, however, this is done without eliminating the men and husbands at Peggy’s side. On the contrary, her victory is supported by Stillman, with only “the hurricane deck” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 315; emphasis added) a latent reminder of the violent upheaval and temporal rupture involved in the transformation as well as destabilization of the American family at the turn of the century.

9 Given that the Talberts belong to the middle-upper class, “the music-room” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 314) points to yet another discursive and chronotopical layer that is associated with travel, leisure, and tourism for those Americans who can afford it. Quotidien temporality is suspended predominantly through the pleasures of artistic performances, be they on board of a ship or during the Grand Tour through the Old World, and reordered according to the consumption of the arts, foreign cultures, and pleasurable performances.

10 A digital image of the painting can be viewed at https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065872.

In the final paragraphs of the novel, the homodiegetic narrator and friend of the Talbert family, Gerrit Wendell, leads us from the heterotopian desires for a generation of New Women parading victoriously into the new century without threatening a bloodbath back to the American (nuclear) family. The remaining family members, it appears, want to have it both ways. After Gerrit’s dictum, they split into two groups: there is the conventional family unit consisting of the younger generation (Maria and Tom with their children Alice and Billy); and the older generation of grand/parents (Cyrus, Ada, and Gerrit). By separating them, van Dyke’s narrator arguably reestablishes a universe in which the lives and timespaces of the young and the old are relegated to clearly designated spacetimes and identities. The potentially messy complications and dormant threats inherent in the heterotopia of the revolutionary travelers and New Women aboard the Chromatic are categorically rejected: “we don’t want the whole family” (Howells et al., 1908, p. 315).

The examination of chronotopicity in The Whole Family enables us to understand this collaborative project as contributing to the modernist reworking of the chronotope of the family idyll from an American perspective. More specifically, the composite novel directs our attention to three generations of men and women (including boys and girls) of New England’s white, leisured suburban middle and upper class. Telling the story of a family in crisis at the moment of the daughter’s engagement, it shows the traditional family idyll colliding with as well as fanning out into multiple individual life sequences that, despite their family relations, significantly differ from each other. Indeed, in each chapter, and for each individual family member, time, space, and identity begin to multiply in ways unreconcilable with the repeated cycles, rhythms, familiar routines and locales of the traditional family novel, albeit to varying degrees. Characters whose desires and actions depart from or run counter to the ideal of the family unit—like Freeman’s single Elizabeth/Lily; James’s Charles Edward; but also Phelps’s active, confident Maria/Meddlymaria; and young Alice/Clarry, whose rejection of traditional quilt-patterns symbolizes both the experience and expression of a modernist chronotopicity— struggle with a greater degree of alienation. Their estrangement from the family and the world they inhabit is intensified by their very own contradictory selves brought about by major chronotopic transformations. But also those characters who identify more closely with the nuclear family are shown to combine the family idyll with novel spatiotemporal regimes and unknown selves: Cyrus, for instance, recognizes Peggy’s coeducation in Howell’s introductory contribution; Grandmother Evarts replaces religion with a new medical regimens for the health of her mind and soul in the chapter by Vorse; Billy’s stream of consciousness is added to the dominant adventure time by Andrews; and Gerrit’s view of heterotopia clashes with his final desire for a generational separation in van Dyke’s concluding chapter. But no matter to which degree, the authors and their individual characters are all entangled in the momentous changes when the American family finds itself—like Maria’s/Meddlymaria’s asteroids—spinning through multiplying spacetimes and discursive transformations as well.

Ashton, S. (2001). Veribly a purple cow: The Whole Family and the collaborative search for coherence. Studies in the Novel, 33(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403982575_5

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin: University of Texas Press (Original work published 1934–1941).

Baur, D. M. (1991). The politics of collaboration in The Whole Family. In L. L. Doan (Ed.) Old maids to radical spinsters: Unmarried women in the twentieth-century novel (pp. 107–122). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Beal, W. (2016). Visualizing The Whole Family. Intertexts, 20(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/itx.2016.0002

Blommaert, J., & De Fina, A. (2016). Chronotopic identities: On the timespace organization of who we are. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 153, 1–26. Retrieved July 28, 2025 from https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/32302149/TPCS_153_Blommaert_DeFina.pdf

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1979). The inheritors: French students and their relation to culture. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Casarino, C. (1995). Gomorrahs of the deep or, Melville, Foucault, and the question of heterotopia. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, 51(4), 1–25. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/arq.1995.0002

Delacroix, E. (1830). Liberty leading the people. Louvre. Paris, France. Retrieved July 28, 2025 from https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065872

Foucault, M. (1986). Of other places. Diacritics, 16(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/464648

Howard, J. 2001. Publishing the family. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11hpmd1

Howells, W. D., et al. (1908). The Whole Family: A novel by twelve authors. New York and London: Harper & Brothers.

Kilcup, K. 1999. Soft canons: American women writers and masculine tradition. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/book80

Rankin, J. R., & Collins, F. L. (2017). Enclosing difference and disruption: Assemblage, heterotopia and the cruise ship. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(2), 224–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1171389

Schleifer, R. (2000). Modernism and time: The logic of abundance in literature, science, and culture, 1880–1930. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511485299

Shepard, S. V. (2001). The patchwork quilt: Ideas of community in nineteenth-century American women’s fiction. New York: Peter Lang.

Stone, J. (2008). Polyphony and the atomic age: Bakhtin’s assimilation of an Einsteinian universe. Modern Language Association, 123(2), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2008.123.2.405

Corresponding author: Michaela Keck

Contact email: michaela.keck@gmail.com

Asura Becomes Bishōnen: Decoding the “Shōjo-manga-fication” of Rig Vedic Deities in CLAMP’s RG Veda

Kunal Debnath

Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, India

Nagendra Kumar

Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, India

The present study aims to explore the representation of Rig Vedic deities in Japanese manga artist group CLAMP’s RG Veda manga There are several genres of manga, such as shōnen manga (manga for adolescent boys), seinen manga (manga for young-adult/adult men), josei manga (manga for adult women), et cetera. RG Veda manga falls into the shōjo manga genre. The genre denotes manga that are aimed at the adolescent female demographic. Shōjo manga have a distinct set of generic conventions that distinguish them from shōnen manga and seinen manga, such as the presence of bishōnen/biseinen, playing with gender, focus on ningen kankei, doe-eyed characters, and so on. Using the shōjo manga generic conventions of bishōnen, ningen kankei, Boys Love, gender-swapping, and visual aesthetics as the theoretical background, the article aims to decode the representation of Rig Vedic deities in the manga, mainly concentrating on the role of the generic conventions of shōjo manga in their depiction. There is a dearth of critical literature dealing with the issue of the representation of Rig Vedic deities in RG Veda manga, and the study aims to fill that research gap.

Keywords: bishōnen, Boys Love, Hinduism, mythology, ningen kankei, shōjo manga

Manga are comics created in Japan and conform to a style developed in Japan. Manga are produced and divided into genres based on age and gender. The four most popular genres of manga are:

1. Shōnen: Manga aimed at adolescent boys;

2. Shōjo: Manga aimed at adolescent girls;

3. Seinen: Manga aimed at young-adult/adult men;

4. Josei: Manga aimed at adult women.

Shōjo manga are created for a female audience ranging from twelve to eighteen years of age (Brenner, 2007). The roots of shōjo manga can be traced back to shōjo bunka (Shamoon, 2012). Shōjo bunka was the prewar girls’ culture that was born from certain cultural phenomena, such as girls’ magazines, fan meetings, poetry, illustrations, shōjo shōsetsu 1 , and a focus on homosocial relationships (Takahashi, 2008). Although manga was also included in prewar magazines, the pages dedicated to it were few and cannot be considered shojo manga per se. It was during the 1950s that shōjo magazines began to increase the number of pages dedicated to manga, and they soon became entirely shōjo manga magazines. During the 50s, shōjo manga artists were mostly male. However, the number of female manga artists gradually increased in this period. From the 60s, female manga artists started to dominate the genre. Then, a revolution happened in the 1970s female manga artists took over the shōjo genre. The revolution started with the Year 24 Group 2 or “The Magnificent Forty-Niners”. They pioneered most of the characteristics visible in shōjo manga today. Some of these traits include questioning gender roles, playing with gender, focusing on ningen kankei3, bishōnen characters, fluid or nonlinear manga panels, layering, and a focus on interiority (Shamoon, 2012; Natsume, 2020). They also included homosexual romance in their manga, particularly male homosexual romance or “shōnen-ai” it would later pave the way for today’s Boys Love and yaoi subgenres in shōjo manga (Toku, 2007). During this period, shōjo manga also began to include new genres, such as sci-fi, historical drama, sports, et cetera. Though the genres have diversified since the 1970s, romance and ningen kankei are still thematic concerns in a lot of shōjo manga (Prough, 2011).

RG Veda4 is a manga work created by the Japanese all-female artist group CLAMP. It was serialized from 1989 to 1996 in the monthly magazine Wings, published by Shinshokan, and was completed in ten volumes. RG Veda falls into the shōjo manga genre. This manga is an appropriation of the Rig Veda, the Hindu holy scripture. Appropriation is different from adaptation. As Sanders writes, “[…] appropriation frequently effects a more decisive journey away from the informing text into a wholly new cultural product and domain, often through the actions of interpolation and critique as much as through the movement from one genre to others […]” (35-36). Manga artists love to borrow myths from various cultures and religions,

1 Girls’ fiction: a genre of Japanese popular fiction aimed at girls that emerged in the late 19th century.

2 The reason why they are called the Year 24 Group is that they were born in or around 1949, the 24th year of the Showa Era in Japan.

3 Human relations.

4 The term RG Veda (in italics) is used to refer to the manga by CLAMP

including Hinduism (Levi, 2000; Debnath & Kumar, 2024). CLAMP’s narrative oeuvre also showcases this aspect. One issue to mention is the influence of generic conventions. Though some manga defy generic conventions (Petersen, 2010), there is no denying that genre acts as a significant structuring framework for the storylines in manga (Shamoon, 2024). The present study will primarily focus on the generic conventions of Japanese shōjo manga in CLAMP’s manga RG Veda to study the representation of Rig Vedic5 deities.

Although there are studies on CLAMP’s other manga, such as Cardcaptor Sakura (Rattanamathuwong, 2021), Chobits (Bryce & Davis, 2010), and Tsubasa: RESERVoir CHRoNiCLE (King, 2019), no exhaustive study is available on RG Veda manga, let alone on its portrayal of Rig Vedic deities. Though there are slight mentions of the manga here and there (Bryce & Davis, 2010; Brenner, 2007; Xu & Yang, 2013), no comprehensive study exists on this manga’s depiction of Rig Vedic deities. Therefore, the present study aims to bridge that research gap by analyzing the portrayal of Rig Vedic deities in RG Veda manga, with a primary focus on the influence of generic conventions of shōjo manga. The paper will adhere to the shōjo manga generic conventions of bishōnen, ningen kankei, BL 6 , gender-swapping, and visual aesthetics as the theoretical background to study the portrayal of Rig Vedic deities. The paper will unravel the “shōjo-manga-fication” of Rig Vedic deities.

The plot of RG Veda manga follows the story of Ashura and Lord Yasha, who embark on an adventure to defeat Taishakuten, the god of thunder. Taishakuten rebelled against the Heavenly Emperor, killed Lord Ashura, and usurped the throne of heaven. The story narrates how Ashura, the son of Lord Ashura, and Lord Yasha gather allies such as Lady Karura and Sōma, go through tests and trials, and reach heaven to defeat Taishakuten. The story has many twists and turns, and the climax does not provide a wholesome ending. In the end, it is shown that Taishakuten committed all the atrocities to keep a promise to his late lover, Lord Ashura. The promise was to stop the gathering of the Six Stars and hinder Ashura’s transformation into the god of destruction. All through his life, Taishakuten lived in loneliness. The manga follows the narrative template of kishōtenketsu Kishōtenketsu— consisting of “ki” (introduction), “shō” (development), “ten” (twist), and “ketsu” (conclusion) is a four-act story structure traditionally followed in East Asia (Debnath & Kumar, 2025). This story structure emphasizes the absence of binary oppositions and presents a plurality of perspectives. Thus, the death of Taishakuten is not shown as a triumph of good vs evil. Instead, it is shown in a way that the audience will feel sad, even for a tyrant.

The “Shōjo-manga-fication” of Rig Vedic

A genre is a categorization of texts based on their similarity of setting, plot structure, emotional effect, theme, et cetera. It is also a pact between consumers and producers, which lets the consumers know beforehand what they can expect from the story (Valaskivi, 2000). The storylines of literary texts are, to a great extent, influenced by the genres and subgenres they

5 The terms “Rig Veda” & “Rig Vedic” are used to refer to the Rig Veda, the ancient Hindu scripture.

6 Boys Love

belong to (Thomas, 2010). This, however, does not mean that there are no genre-defying texts or that texts belonging to a certain genre blindly follow that genre’s conventions. Still, the genre of a text nevertheless gives us some idea of what the story will look like. Similarly, the storylines and characters of shōjo manga are, more or less, shaped by the genre and subgenre. As Deborah Shamoon observes:

The manga genre is… more than just a marketing segment or a series of editorial guidelines. Understanding the parameters and meanings of manga genres explains not only specific narrative and aesthetic choices but also how manga narratives function socially for readers… they inform readers of the type of content they can expect in terms of both narrative and art style (2024, pp. 161-62).

This aspect, in turn, relates to the portrayal of myth in manga and anime. As Castello and Scilabra write, “… myth, its use (and abuse) and its alteration depend on the anime genre and the plot” (2015, p. 193). Though they are speaking in relation to anime, the same thing is true for manga. For instance, when a manga uses Greco-Roman mythology, there is hardly any focus on authentic adaptation or source-centric fidelity; instead, the story is always appropriated in relation to the generic conventions or the individual imagination of the manga artist (Thiesen, 2011). This observation also applies to the depiction of Rig Vedic mythology in RG Veda manga, as explained in the following subsections, which unravel the “Shōjomanga-fication” of Rig Vedic deities. By “Shōjo-manga-fication,7” I mean the filtering and reimagining of Rig Vedic deities through the generic conventions of shōjo manga. In light of the norms of Japanese shōjo manga (since the manga in question originated in Japan), the following points can be made regarding the appropriation of Rig Vedic deities in RG Veda manga.

In the early parts of the Rig Veda, the term “Asura” does not refer to any particular deity or a group of supernatural beings. It has been used as an adjective to mark a Vedic deity as wise and powerful (Rigveda8, I.24.14). However, in the Rig Veda’s later parts, the God/Asura duality starts. The term “Asura” begins to denote beings who are against the gods (Rigveda, X.53.4). As Hale writes, “…the asuras do not seem to form a group in the early parts of the RV [Rig Veda], and in the later parts they are anti-godly, not divine” (1986, p. 27). In the later Vedic and post-Vedic ages, the Deva9/Asura duality becomes more prominent, and the term “Asura” gains the pejorative connotation the enemy of the gods (Chawla, 1990). However, we do not find any concrete description of Asuras’ iconography in the Rig Veda.

7 My coinage.

8 The term “Rigveda” (without space in-between) is used in the paper as a citation.

9 The Hindu term for “God.”