This document was written and collated by staff from the Environment Agency, Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, Nottingham Trent University, Wessex Rivers Trust and the Wild Trout Trust.

It has been provided to answer calls for guidance from landowners and organisations responsible for managing winterbournes. This is an area that is not well researched or documented and the intention is that this guidance will be updated as knowledge on the subject improves.

4. Executive Summary

5. An introduction to winterbournes

7. Why are winterbournes important?

8. Life in a winterbourne

11. Human pressures on winterbourne health

15. Managing winterbournes

24. Strategic Restoration of winterbournes

RESTORING WINTERBOURNES - CASE STUDIES

25. Candover Brook, Hampshire, 2011

26. South Winterbourne, Dorset, 2009–18

28. Hamble Brook, Buckinghamshire, 2023

30. River Og, Wiltshire, 2023

36. Conclusions

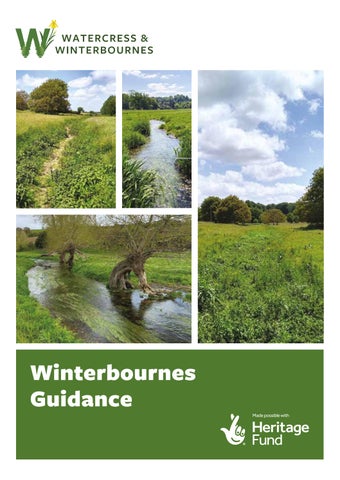

Winterbournes are rare and special stretches of chalk streams that naturally dry at certain times of the year as groundwater levels in the aquifer fluctuate. They support high biodiversity and specialist wildlife that is adapted to the alternating dry and flowing phases, including several rare invertebrates and plants.

Winterbournes support fragile ecosystems that are likely to be impacted by climate change if summers are drier and winters are wetter.

Therefore, any management carried out within a winterbourne must be done with sensitivity, taking into account the needs of the wildlife that relies on this dynamic habitat.

Restoring natural processes to winterbournes to increase resilience to current pressures and future change should be strategically prioritised.

Winterbournes are often headwaters so are a good place to start in any plan to restore and improve a catchment. The health of headwaters helps to define the health of the river downstream, so any improvements in winterbournes have high potential to positively impact the whole catchment.

One of the rare and special characteristics of our chalk streams is the winterbourne stretch – the naturally intermittent ‘bourne’ that only flows when there has been enough rain to saturate the aquifer enough for the groundwater to rise and springs to flow.

Located in the headwaters, at the top of the catchment, winterbournes are groundwater fed and typically only flow at certain times of the year, their presence determined by the fluctuating groundwater levels within the chalk aquifer. The cycle and extent of the winterbourne changes each year, but there is natural predictability; in a dry year, some winterbourne sections may not flow at all, and in a wet year they may flow all year round. As the groundwater falls below the level of the stream bed and springs stop flowing, the stream dries. Thus, chalk streams are often several kilometres longer in winter than in summer, when the winterbourne retreats downstream to the ‘perennial head’, below which point the river always flows.

In their dry phases, winterbournes can look more like a dry ditch or a path, and they are therefore often overlooked as functioning ecosystems. For this reason, historically, winterbournes have frequently been moved, straightened, ploughed or otherwise modified. In these situations, the natural vegetation mosaics that transition between fen, swamp, unimproved chalk and neutral grasslands and are integral to the winterbourne feature have often been lost. Whenever flowing water is absent, people can easily misunderstand the function of the winterbourne, making them particularly vulnerable to damage.

As winterbournes transition between flowing, ponded and dry states, they create ever-changing habitat mosaics that support high biodiversity, including aquatic and terrestrial species. For example, during the ponded phase, specialists like caddisfly larvae – which are usually restricted to floodplain ponds – move into the temporary pools in the river. As those pools dry up, mud beetles arrive to graze on the rotting algal material that has been left behind, and ground beetles eat the dying aquatic invertebrates.

Looking beneath the surface, it is possible to find a hive of activity in winterbournes during both their wet and dry phases. Winterbournes can have an even greater biodiversity than the constantly flowing reaches; in fact, the unique ‘aquatic–terrestrial’ biodiversity of our winterbournes is considered to be internationally important with species that timeshare the channel as it shifts between flowing, pool and dry phases.

Those on the gentle slopes of chalk downland are typically long; for example, the Nailbourne in Kent, the River Bourne in Wiltshire, and the River Lavant in West Sussex. Those that rise at the foot of steep slopes are much shorter, and quickly take on different characteristics due to changes in the geology; good examples of this are the Ewelme Brook and Ladybrook in Oxfordshire, and numerous unnamed streams across the South Downs in West Sussex.

Chalk streams are rare and wonderful, celebrated for their biodiversity and cultural value, but their winterbourne stretches are perhaps their most mysterious and interesting element. They need better protection, management, and recognition as the amazing and unique treasures that they are.

Winterbournes are found in chalk landscapes across Dorset, Wiltshire, Berkshire and Hampshire to Buckinghamshire, Kent, and Hertfordshire. Elsewhere – in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and Norfolk, for instance – these intermittent streams are less common and often go by different names, such as the Gypsey Race near Bridlington. The length and nature of chalk winterbournes also differs due to their topography and underlying geology.

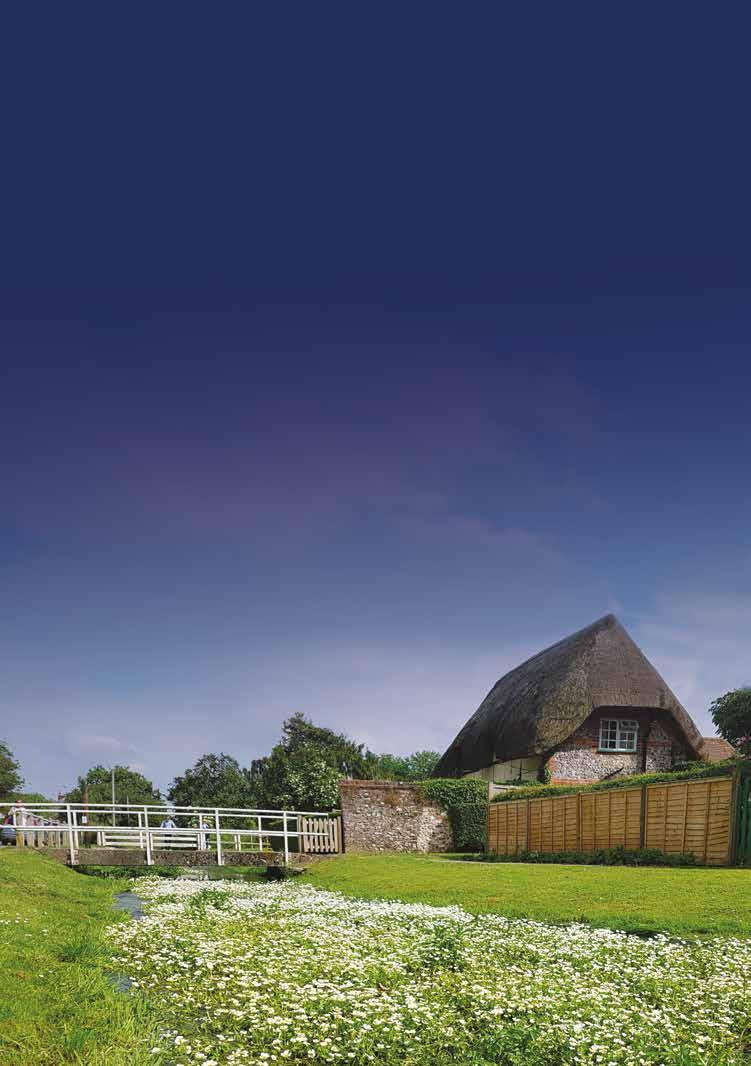

Winterbournes create a strong sense of place because of their enigmatic cyclical character. Evocative winterbourne names include the Gypsey Race, Nailbourne and Nine Mile River and they are etched into our cultural heritage through place names such as Otterbourne, Lambourn, King’s Somborne and Winterbourne Abbas. Historically, rural communities may have been more in tune with the natural fluctuations in winterbourne hydrology than many people these days, because they relied on wells fed by water from the chalk aquifer. Hence, people would have been able to observe or get a feel of local groundwater levels rising and falling, even when the winterbourne was dry, as the aquifer was recharged through percolating rainfall and then depleted again. In some cases, such as the Bourne Rivulet or Hamble Brook, groundwater levels can naturally fall by 8 metres or more when recharge is low.

In their flowing phase, winterbournes resemble perennial chalk streams in their iconic beauty: crystal-clear water, flint and fragmented chalk substrate, prolific plant growth, and high biodiversity and bio-abundance. They offer opportunities for fishing, swimming, art and poetry,

research and learning, and appreciation of nature and cultural heritage such as watercress growing or water meadows. In this phase, they have the same capacity for inspiring awe in nature and enhancing one’s mood as their ever-flowing counterparts.

In their natural ponded phase, winterbournes are characterised by decaying vegetation, stagnant water, and stranded, sometimes dying aquatic animals including fish and invertebrates, but the ponds that persist are valuable refuges for aquatic species. This transitional phase gives way to the dry phase, where the silts and flints of the stream bed are fully exposed. Some remain rocky for the entire dry phase, while many are gradually colonized by terrestrial grasses, ruderal communities and terrestrial invertebrates such as ground beetles, spiders and ants. In these non-flowing phases then, winterbournes may be misinterpreted as being damaged or degraded chalk streams, the assumption being that they should be perennial, flowing year-round. However, it is their non-perennial nature that creates a distinct sense of place. These non-flowing phases afford opportunities for nature appreciation in different ways and some people connect with their winterbourne by exploring the unique perspective from a dry stream bed like a hollow-way and even finding fossils.

Hence, many winterbourne owners and managers highly value these temporary streams for their diverse wildlife and curious aesthetic beauty. Winterbournes boost their emotional wellbeing, foster connection to nature and afford space for contemplation and perspective. There is often also a strong sense of stewardship, a wish to restore and improve their winterbournes for future generations.

This management guide aims to support winterbourne owners and managers in progressing towards that goal.

The composition and species richness of the communities of aquatic microorganisms, plants, invertebrates, and fish differ between perennial and winterbourne streams. Winterbournes typically have lower taxonomic richness than equivalent perennial streams due to the absence of desiccation-sensitive species, but they often contain rarer species that are adapted to cope with seasonal shifts between wet and dry conditions.

The terrestrial plants and invertebrates that colonise from adjacent riparian zones and further afield will quickly establish biodiverse communities as a winterbourne dries. Taxon-specific responses to local variation in the types and levels of human pressures could enable these communities to act as biomonitors of dry-phase health.

Dry-phase plant communities comprise a mix of persisting aquatic species and colonising terrestrial species. These plants can be easy to survey, and even specimens that are difficult to identify to species level can be recorded as different types, enabling estimation of species richness. Like the aquatic communities present in flowing reaches, dry-phase plants differ between sites depending on levels of nutrient pollution. Simple metrics, such as the number of different grass species, can summarise these differences, thus identifying nutrient-polluted sites at which action is required to improve river health.

habitat modification and fine sediment pollution. And as with plants, specimens that are challenging to identify can be recorded as distinct types, allowing estimation of simple, informative metrics such as species richness.

Winterbournes support a range of specialist species that are adapted to their unusual pattern of wet and dry flows,

Terrestrial invertebrate communities comprise a wide range of species, including ants, beetles, spiders, and woodlice. These communities can be sampled using standard methods developed for terrestrial habitats like grassland, including pitfall traps (cups installed in the bed for periods of e.g. 1–2 weeks) and simple ‘hand searching’ (e.g. turning over stones, woody material, and plants by hand to search for organisms).

As with dry-phase plants, invertebrate communities will differ depending on the physical and chemical characteristics of their environment. They can thus indicate ecological responses to human pressures such as physical

Similarly, the nationally rare winterbourne stonefly (Nemoura lacustris) is rarely found in perennial streams but is common in winterbournes. Its life stages are carefully timed to coincide with the stream’s fluctuations between wet and dry: juveniles develop in water and then emerge as flying adults before the dry phase starts. These adults then lay desiccation-tolerant eggs, and the cycle continues.

The winterbourne blackfly (Metacnephia amphora) is restricted to winterbournes in southern England. Its filterfeeding larvae – and that of the blackfly (Simulium latipes) – survive as dormant eggs within the stream bed and then hatch when flow returns.

Some riverine beetle species have also evolved to inhabit sediment along the stream margins that becomes wet and dry with the winterbourne cycle.

It is important to understand that although during the dry phase a winterbourne can appear dead or damaged, it is actually still a functioning ecosystem and management of the winterbourne needs to be adapted to recognise this.

Terrestrial invertebrates in the headwaters of the Rivers Test and Itchen recorded eight species of ground beetle (the family Carabidae) that are particularly rare. Two, Amara nitida and Badister peltatus, are nationally rare and six (Amara montivaga, Badister dilatatus, Badister unipustulatus, Elaphrus uliginosus, Panagaeus bipustulatus, and Pterostichus anthracinus) are nationally scarce.

WINTERBOURNE FISH COMMUNITIES

Seasonal dry phases prevent many fish from inhabiting winterbournes. Nonetheless, winterbourne reaches can make an important contribution to a stream’s overall fish community.

Brown trout are the fish most commonly associated with chalk streams, but winterbournes often also support populations of other species in their lower stretches, such as minnows, sticklebacks, and occasionally brook lampreys, bullheads, and eels. Indeed, the biomass of fish in these streams is often dominated by these ‘minor’ species, as they can exploit microhabitats located in extremely shallow water. Fish such as the minnow and stickleback can persist even in isolated pools.

Brown trout are hard-wired to exploit potential spawning sites in headwaters and tributaries by travelling upstream. Some will swim as far upstream as possible, typically when flows increase over winter. The fittest and strongest fish will reach areas unavailable to the weaker ones, but all will seek areas with fast-flowing waters and clean gravelly beds for productive spawning.

Trout eggs laid in winterbournes in December or January may hatch relatively early the following spring, due in part to the stable water temperatures which are usually above the winter average compared to surface water-fed systems. Upon emerging from the gravel in March or April, the trout ‘fry’ are perhaps 20 millimetres long and must grow quickly to have the best chance of survival. Many will seek refuge from predators in very shallow, well-vegetated stream margins, making this one of many species that benefits from our leaving these areas ‘shaggy’ and unmown. The fish will move downstream as they grow into juvenile ‘parr’ and will then migrate both up and down as the flow fluctuates. It is likely that wild chalk stream trout have local genetic adaptations that drive this instinct for migration.

After the winter spawning period, most adult fish will move back downstream as flows decline, but a proportion often stay, especially if there is good adult habitat in the form of deeper, well-vegetated pools. Such pools usually reflect some kind of human-caused channel modification, such as the bed being scoured away by fast-flowing water immediately downstream of a culvert. This can be problematic, as many of these fish will seek to stay in the

deeper pools even when they become isolated by the dropping water level. As the summer unfolds and these pools shrink, the fish can be an important food resource for predators like the otter and heron, or provide nutrients back into the base of the food chain if suffocation occurs in the warmer months.

The typical plant of the flowing winterbourne is the pondwater crowfoot (Ranunculus peltatus) an emblematic early flowering species that grows as an annual, thriving at sites that dry for over 6 months but flow every year. Marginal plants including watercress (Rorippa nasturtiumaquaticum), fool’s watercress (Apium nodiflorum), sweetgrass (Glyceria spp.), brooklime (Veronica beccabunga), water speedwell (Veronica anagallisaquatica), water forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpiodes) and water mint (Mentha aquatica) also often occur, becoming more dominant as flow recedes. By late autumn, dry conditions may mean that grass species, willowherb and nettles may dominate the channel again.

There is a clear succession of plant communities growing in these intermittent streams, which makes them a conundrum for habitat managers. Terrestrial grasses and herbs that prefer dry conditions give way to marsh foxtail (Alopecurus geniculatus), flote grass (Glyceria fluitans), water mint (Mentha aquatica), followed by fast-growing annuals like watercress (Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum), fool’s watercress (Apium nodiflorum) and water speedwell (Veronica anagallis-aquatica/catenata). Where the perennial stream begins, different plant communities – dominated by water starwort (Callitriche spp.) and water crowfoot (Ranunculus penicillatus subsp. Pseudofluitans) – take over.

In unmodified winterbournes, the riparian area shows a transition from wet to dry fen, swamp, unimproved chalk and neutral grasslands and include species such as tufted

hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa), marsh bedstraw (Galium palustre), common meadow rue (Thalictrum flavum), pepper-saxifrage (Silaum silaus), marsh speedwell (Veronica scutellata) and various sedges including greater tussock sedge (Carex paniculata). Willow and alder carr will also form part of this wetland mosaic.

Many winterbournes are home to a range of vertebrates during the flowing phase. Ducks, moorhens, and coots move in as soon as flows reappear, and commonly nest in these reaches. When winterbournes dry out earlier than usual, ducks have been observed leading their ducklings along adjacent roads, in essence, moving downstream with the receding flows. The ponded phase, where flow has ceased but water remains in pools, is a time of plenty for herons. It is best not to rescue fish from these pools, because they play an important role in the food chain. As the water returns, predators such as otter, egrets and kingfishers have been observed expanding their territories upstream and water voles will also move into winterbournes during the flowing phase, if the habitat is right. During dry phases, badger and roe deer are also frequently seen in winterbournes, possibly using them as routes.

Although they occur further upstream than perennial chalk stream reaches, winterbournes are exposed to the same, if not greater range of anthropogenic pressures as the river downstream. These include climate change, physical habitat modification, abstraction, pollution, invasive non-native species, and poor management practices. As in every river, these pressures have multiple individual and interacting effects on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

Their seasonal shifts between wet and dry phases can leave winterbournes at risk from a number of these pressures. It is, for example, easier to dredge or even reroute a watercourse when it is dry and damage from grazing can often be an issue for winterbournes. In addition, our limited understanding and appreciation of these dynamic ecosystems has left winterbournes excluded from the policies and practices that protect some of our perennial reaches.

Due to their dynamic nature, winterbournes are sensitive ecosystems and so changing weather patterns can have a significant negative impact on them. Winterbournes that retain more natural physical form and processes, including their connection to the floodplain and that have a diversity of habitat species have more resilience and protection against the extremes of weather associated with climate change. For this reason, restoration for channels that have been changed from their natural state is now increasingly important.

In our changing climate, the frequency, duration, and severity of droughts and floods are increasingly changing winterbourne flow regimes, including the timing and rates of the wet/dry and dry/wet transitions.

Drought typically increases the length of dry phases in both space and time, causing declines in the abundance and diversity of aquatic communities that depend upon the flow.

Winterbournes are often shallower than perennial downstream reaches. Rising air temperatures can therefore increase their water temperature – especially during summer heatwaves – despite the buffering effect of the cooler groundwater. These increases could push fish and sensitive invertebrate species such as riverflies past their thermal tolerances, with brown trout among those at risk of local extinction.

Lower water levels during drought also exacerbate other pressures, for example, increasing concentrations of some pollutants. Lower flows are also less able to transport fine sediment, which may thus be deposited on gravel within the winterbourne.

At the opposite end of the scale, high groundwater and flooding can cause sewage and drainage systems to be inundated and road runoff to increase, transporting harmful sediment and other pollutants into winterbournes.

Winterbourne wildlife needs a diversity of complex habitats to thrive. But like their perennial counterparts, many winterbournes have been straightened, widened, deepened, rerouted, dredged, dammed and disconnected from their floodplain. Natural winterbournes probably had fairly uniform bed profiles given their low gradients and lowenergy flow regimes, and natural bed variation is likely to have been due to localised scour caused by mats of dense vegetation and fallen trees, and rare major flood events.

In their dry phases, many winterbournes have been cultivated, reseeded, agriculturally intensified and

drained. These activities lead to a loss of rich plant community mosaics and the invertebrate and wider wildlife that they support.

For winterbournes to function well for fish communities, they need to be naturally connected to perennial reaches downstream. Most chalk stream channels are modified, in particular by water level control structures, culverts, and bridges, which act as barriers to migration. Just one or two inappropriately located and/or poorly designed, structures can seriously impact both upstream and downstream fish migrations, preventing them from reaching their spawning grounds. On such systems, access for weak swimming fish such as bullhead is usually impossible: unlike trout, they cannot negotiate even modest (a few cms) steps in the streambed.

The abstraction of water from chalk catchments can have particularly severe impacts on winterbournes. It can result in moving the entire winterbourne downstream but it can also extend the length of dry phase and drying of the riparian zone in both space and time. This, reduces the length and area of the wetted channel and water depth and velocity during the flowing phase. As a result, aquatic species are more likely to be lost when their capacity to tolerate drying is exceeded, or when their ability to migrate upstream and downstream with the fluctuating flow is impeded by obstructions such as weirs.

Winterbournes are particularly vulnerable to the same increasingly wide range of pollutants that affect all chalk streams.

In their natural state, flowing winterbournes are ‘crystal clear’ with little sediment, low nutrient levels, and stable temperatures. However, due to inputs from off-mains sewage treatment plants, sewage treatment works, agricultural practices, and road and track runoff, many have elevated levels of nutrients, sediment, and chemicals such as pesticides.

Inorganic nutrient pollution – particularly from agricultural land, but also from sewage – promotes the excessive growth of a few competitive plants in particular nettles and grasses during the dry phase, and algae during the wet phase. These plants can outcompete other native flora, reducing overall biodiversity. Respiration by these plants and algae can reduce dissolved oxygen levels during low flow periods and ponded phases; in particular at night, when oxygen-producing photosynthesis ceases. This can result in the death of many fish species as well as sensitive invertebrate species such as riverflies.

Fine sediment inputs from road runoff and bare arable land are particularly important sources. As flows recede and

aquatic habitats contract, polluting nutrients can become concentrated in isolated pools. This promotes the growth of filamentous algae at the expense of total biodiversity, and can cause declines in water crowfoot in particular. In addition, fine sediment is often deposited as flows recede, smothering the stream bed and reducing habitat diversity. Chalk streams – and winterbournes in particular – are ‘lowenergy’, and so often lack the powerful flows needed to move this fine sediment downstream.

Many winterbournes are in rural locations, in which properties are often not connected to the main sewer system. Instead, they use private ‘off-mains’ alternatives: cesspits, septic tanks, and package treatments plants. Cesspits are fully contained, while septic tanks discharge wastewater into a soakaway (such as a gravel pit) which seeps into the groundwater. Package treatment plants release more highly treated wastewater, and so may be permitted to discharge directly into a winterbourne.

If these systems are poorly managed, they can introduce nutrient and chemical pollution to both groundwater and surface water. As winterbourne flows experience their seasonal declines, input from off-mains sewage becomes increasingly concentrated, presenting a risk to water quality. Standard advice to mitigate pollution is thus particularly important in winterbournes and there are legal requirements for homeowners.

Homeowners are advised to use phosphate-free cleaning products that have been specifically designed for use with septic tanks. Avoid using bleach, paint, disinfectants, pesticides, medicines, and solvents like white spirit, as these can kill the bacteria that break down the waste within the tank.

Furthermore, avoid introducing solids like food waste, sanitary products, and flushable wipes, as these can cause blockages. Keep your tank working effectively by having it emptied and maintained regularly. Further guidance on septic tank management is listed in the Further Information section at the end of this document.

An invasive non-native species (INNS) is one that has been introduced outside of its natural range and has negative impacts, for example on ecosystem health. There are many invasive non-native species that will have a detrimental impact on the fragile ecosystem of a chalk stream. For a list of floral and faunal INNS in your area, contact your local biodiversity centre or Wildlife Trust.

Some INNS can damage winterbourne habitats, competing for space and light with the native flora, whilst species such as the American mink voraciously predate native trout, wildfowl, and water vole and can lead to localised extinction of other animals.

Mink numbers should be controlled to preserve water vole populations and other native species. Advice on managing mink can be provided by your local Rivers Trust or Natural England officers.

Ideally, mink should be tackled across the whole catchment. It is recommended that riparian landowners work with neighbours and wildlife organisations to manage this species. The Waterlife Recovery Trust have new and improved initiatives that should be investigated regarding mink; they also have useful information and factsheets: waterliferecoverytrust.org.uk

Full details and photos of all of the invasive non-native species found on chalk streams are provided on the Test & Itchen INNS Project Site: storymaps.arcgis.com/ stories/176a464b691a44158f626f3594127a4d

Floral INNS – notably Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera) and Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) are two species that are commonly found in winterbourne corridors. They should be removed and disposed of in accordance with the current guidance, summarised on the project website above.

Due to their vulnerability and exposure to human pressures, winterbourne channels require sensitive management to maintain healthy conditions for the wide community of species that are adapted to their ever-changing habitats. A good place to start is by contacting expert bodies for bespoke advice, such as the Wild Trout Trust or your local Rivers or Wildlife Trust.

Poor appreciation of their aquatic–terrestrial biodiversity leaves winterbournes particularly vulnerable to inappropriate management activities. Mowing the vegetation within the channel and on the banks will damage aquatic, marginal and riparian plants, and also reduce habitat quality for the terrestrial invertebrates that rapidly colonise drying channels.

In general, vegetation should be left unmanaged to naturally change through the different phases. However, in areas such as the Thames catchment where prolific growth of aquatic submerged and emergent vegetation in small channels creates serious flood risk, then careful vegetation cuts can be carried out creating a sinuous channel through the plants.

Managers should avoid removing species that don’t appear to be growing and should not be tempted to infill bare areas with ornamental garden plants. The seedbank just needs the conditions to be right before the natural vegetation reappears. Plants from perennial watercourses may not be adapted to winterbourne conditions.

Timing your work

Due to the vulnerability of winterbourne species to disturbance, any work carried out in or near the channel needs to be carefully timed.

Working in or near the channel in winter and spring should be avoided, to prevent disturbance to spawning fish. It is

also important, during this time, to avoid stirring up silt and fine sediment; these can clog the gravels that fish need to spawn successfully.

Work done in summer should recognise that dry channels support high biodiversity, including dormant, desiccationtolerant invertebrate life stages and microorganisms, which are key to the natural functioning of the winterbourne. Amphibians may also shelter under rocks in a hot summer so any activity within the winterbourne needs to be sensitively carried out.

A varied channel shape helps to sustain natural processes such as sediment transport, but many winterbourne channels have been modified by unsympathetic land-use practices. Winterbournes would naturally be reasonably broad but shallow channels, closely connected to their floodplain. A common cause of channel damage is excessive cattle ‘poaching’, in which trampling by livestock compacts streambed sediments, erodes the banks, and increases channel width. Livestock grazing should be extensive to protect the winterbourne habitat (including the riparian area) and fertiliser should not be applied to the floodplain. Fencing can be controversial in chalk stream landscapes, but temporary fencing can present a solution when livestock densities cannot be reduced or the grazing regime altered to less harmful levels (e.g. short-term, intensive ‘mob’ grazing).

Winterbournes can also be damaged by deliberate landscape modification, such as drainage for agriculture. A natural winterbourne channel should have a shallow ‘dished’ (or U-shaped) cross-section with an almost indistinguishable boundary between the channel and riparian habitat, along with gentle meanders or wiggles. A sinuous channel indicates less historic intervention and is better able to support a range of natural processes and favourable habitat conditions, including shallow gravelly riffles, deeper pools, steady flowing glides, and exposed areas of stream bed.

The width of a winterbourne channel also warrants consideration. If the channel has been over-widened, the flow power will be insufficient to flush away sediment that has accumulated during dry phases or been washed in from riparian areas; this removes an important habitat feature in the form of clean gravels.

Natural winterbourne chalk springs are a rare and precious type of temporary habitat. In the past, some such springs were excavated, often with the aim of forming perennial ponds.

Whilst ponds are important wildlife habitats, the loss of temporary springs is highly undesirable, and so they should never be excavated. Where possible such artificial ponds should also be restored to natural spring features.

Except during floods, winterbournes have low-energy flows which often lack a perennial reach’s capacity to mould their channels into a diversity of habitats. The natural shape and form of each winterbourne will depend on the landscape. Some have a single channel, whereas others consist of multiple, braided channels. Organisations such as the Wild Trout Trust or your local Rivers Trust or Wildlife Trust can advise on potential options for restoration depending on the channel in question.

In their slightly steeper upper reaches, many dip-slope chalk streams follow a reasonably well-defined dry valleybottom topography and despite past engineering, they may originally have had predominantly single-channel characteristics. In those cases, management of a defined channel form is logical. But further downstream, where the dry valleys widen, it is likely that before engineering intervention, they were large spring-fed fens, with a network of temporary channels across a wider, wetter floodplain. In such cases, creating a new single channel may not be appropriate.

Understanding the natural shape and form of the winterbourne is critical in planning any restoration works. Where the channel’s previous form is not known, it may be possible to identify it via historic maps or using LiDAR or aerial photography. Noticing where water pools or where the ground is more squelchy or where plant communities include more sedge, reed or other wetland species can also be informative, as can observing where the water flows across floodplains in times of groundwater flooding.

Where a single channel is an appropriate goal, excavating a dished cross-section and meandering channel form will concentrate flows and recreate a more natural winterbourne connected to its floodplain. Avoid the temptation to narrow winterbourne channels too much –they should have a shallow dish shaped form.

Where a channel shape has lost its definition, the stream flow can also be reharnessed by strategically pinning woody materials, even whole trees into (along and at angles across) the stream bed. Large woody materials, along with a good depth of natural flinty substrate and a diverse aquatic vegetation community, are the principal drivers for dynamic geomorphological processes. Such wood imitates the natural process in which fallen trees force the flow into a beneficial course that eventually becomes self-sustaining. The design and installation of these woody flow deflectors is a cheap and sustainable tool in helping to repair stream channels; further guidance is available from organisations, including the Wild Trout Trust.

In winterbourne channels that retain their natural shape, activities that could damage this should be avoided during both wet and dry phases. Such activities include dredging, driving heavy machinery across or along the channel, and excessive poaching by livestock. Any natural bed substrate (flints and chalk fragments) should be retained, as this provides habitat aquatic and terrestrial species. Where such gravel has been removed through dredging, adding more is an important restorative measure, especially if it can be sourced from the adjacent floodplain, which can also create wetland ‘scrapes’.

Winterbournes with multiple braided channels can create a mosaic of a floodplain wetland habitats. In these instances, the winterbourne can be encouraged to naturally move through multiple, low banked branching channels that are hydrologically well connected to the floodplain. In such cases, the winterbourne should be managed as a floodplain wetland.

Where machinery needs to be used on site for restoration, low ground pressure plant and excavators are recommended to minimise damage. Careful positioning of equipment can maximise useful rotation and reach and minimise lateral movement.

Before starting any works in or near a wet or dry winterbourne, you must contact the Environment Agency to see what permissions are required.

In winterbourne reaches that remain dry for some time, sediment can accumulate and cover the gravelly stream bed. If the channel width is sufficiently narrow, this will be removed by the returning water without the need for mechanical intervention. This scenario is preferable as it reduces disturbance of the stream bed, thus reducing the risk of harm to wildlife. Actively removing silt is only appropriate where the channel shape cannot be restored through options such as narrowing with woody material or introducing new gravel substrate. Desilting often disconnects the channel from the landscape by creating a bund (mound of soil). It should absolutely be a last resort, and all material must be completely removed from the floodplain not left on the banktop.

Generally, management of in-channel vegetation is not required in any of the phases and may disrupt natural processes and sensitive habitats and species. The clogging of channels by extensive plant growth is a natural stage in the winterbourne cycle and may mean that water is backed up and retained for longer in pools which promotes survival of aquatic species when the rest of the winterbourne dries.

However, in areas where development has encroached on the floodplain, creating flood risk, Parish Councils and the Environment Agency may take action to reduce risk. In these cases, intervention should be minimised, for example by cutting a sinuous linear swathe through dense in-channel vegetation. Cutting up to 20% of the whole channel width is enough to provide 80% conveyance efficiency, so complete clearance of all in-channel vegetation is unnecessary.

Terrestrial grasses may dominate the vegetation of many winterbournes during their dry phase. As flows return, these grasses can survive being submerged for many months. In this period, before the aquatic vegetation re-establishes, grasses may be the only in-channel vegetation and thus provide valuable cover for invertebrates and fish. As such, the removal of in-channel grasses is not recommended during any phase.

Some species of water crowfoot are adapted to winterbourne flow regimes, growing and receding in time with the seasons. These plants are the building blocks of life in our chalk streams. In places, water crowfoot can naturally become prolific in the channel and is critically important to wildlife during flowing phases. As such, removal of this or other submerged aquatic vegetation can be harmful and should be avoided.

Hand-pulling should be performed before the roots grow too deep, and only in a sinuous corridor of around 1 metre wide; some vegetation should be retained, as it supports a range

Fool’s watercress (Apium nodiflorum) and hemlock water dropwort (Oenanthe crocata) can both grow profusely, especially as flows recede. These plants can sometimes dominate entire winterbourne channels in the drying phase, causing dense shade and increasing competition for space, to the detriment of overall biodiversity.

Strimming these plants is likely to spread them further, but selective hand-pulling – including the roots – can reduce their growth in subsequent years and creates a varied pattern of shade. Handpull in patches rather than complete removal, as these plants are a natural component of a healthy winterbourne plant community. Hemlock water dropwort is poisonous, and another plant – common hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) – can cause skin irritation. Neither should be strimmed, and protective clothing should be worn for hand-pulling.

Similarly, dense, uniform stands of reed canary grass

can grow to the point of dominating winterbourne channels. Cutting a narrow, sinuous swathe through such stands can promote the healthy flow of water – cutting only 20% of the channel width is enough to let the water flow well. You can do a careful, minimal cut to in-channel vegetation once flows have fully returned to the winterbourne. Complete removal is not advised, as these plants provide a host of benefits to a range of aquatic and terrestrial animals. Any cut vegetation should be left on the bank for a few days to allow invertebrates or amphibians caught in the vegetation to find their way back into the water. After this, the vegetation should be taken well away from the bank to prevent it from falling back in and causing blockages downstream and to

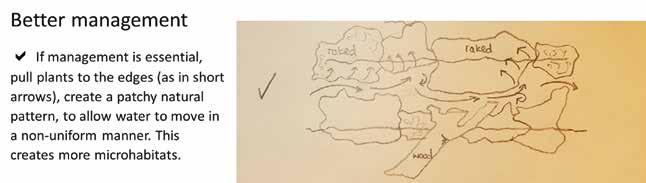

Avoid creating a straight channel.

If management of the weed is essential, use a rake to pull the plants towards the edges of the channel, creating a patchy natural pattern which will allow water to move in a non-uniform manner. This will create diversity of microhabitats.

Various types of algae thrive in warm, slow-flowing, nutrient-rich waters. As winterbourne flows recede and cease, and as surface water is lost, algal mats can smother the stream bed. These mats of dead filaments/algae can remain on the bed during the subsequent dry phase.

Removal is not recommended, as the algae are a natural component of the winterbourne flora that offer habitat and refuge for aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates. However, because excessive nutrients can cause prolific algal growth, tackling the source of artificial nutrient pollution can improve winterbourne health.

In nutrient-polluted channels, stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) can encroach into the channel from riparian and marginal habitats as flow declines and forms increasingly dense stands in dry channels. Nettles (including the roots) should be selectively pulled by mid-summer, before they have a chance to seed to create space for a wider array of flora to thrive. Plants should be taken off-site to avoid releasing nutrients as the plants decompose. This may need to be repeated over several years, to deplete the seed stock and remove nutrients bound up in the plants. Retain some nettles which provide valuable shade and habitat for terrestrial invertebrates.

There are actions that can be taken to control Invasive NonNative Species (INNS):

Keep an eye out for any unusual plant or animal and have it identified by someone knowledgeable. INNS should be tackled straight away as they can establish and, over time, cause ecological damage. Your site could be the source of a problem further downstream, so tackling it will be beneficial to the whole river.

Never use herbicides by a water course. Investigate whether the INNS can be removed by you, or if it should be treated by a licensed contractor who may be able to treat a plant chemically. You may also need to consult the Environment Agency and Natural England and if a permit is required, this can take time to obtain. For information factsheets about INNS you can visit the GB non-native species secretariat website. nonnativespecies.org/whatcan-i-do

Find out about your INNS and how it spreads. Seeds can remain in the seedbank for many years so after initial removal or treatment, continue to check the site for many

years according to the plant in question. Some spread by fragments, so biosecurity is very important. We advocate the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat’s Check, Clean, Dry approach. This means that any clothing or kit used in the river should be checked for fragments, then washed in hot soapy water and allowed to dry thoroughly before being used in a different water body.

Check your equipment, boat, and clothing after leaving the water for mud, aquatic animals or plant material. Remove anything you find and leave it at the site.

Clean everything thoroughly as soon as you can, paying attention to areas that are damp or hard to access. Use hot water if possible.

Dry everything for as long as you can before using elsewhere as some invasive plants and animals can survive for over two weeks in damp conditions.

Sediment-laden runoff can clog the spaces between the streambed gravels, home for a whole host of invertebrates. It is recommended that managers should avoid using pesticides, fertilisers, or manure on land immediately adjacent to winterbourne (and other) channels. and maintain riparian buffers of at least 4 metres wide, comprising grasses, tall herbs, and scattered shrubs and trees.

Sediment-laden diffuse runoff can be managed by first identifying sources and pathways into the channel, for example by looking for cloudy water after heavy rain or rivulets cut into the banks. These could be areas in which to increase vegetation growth, maximising riparian buffer strips or an alternative approach could be to create a scrape to collect the water elsewhere.

Winterbournes are particularly at risk of runoff being diverted straight into the channel from the highway as

they are often immediately adjacent to the road. Where possible, it is much better to divert any such runoff from roads into vegetated areas or sediment traps away from any watercourses.

Any road grips (channels cut through the verge) draining directly to the winterbourne, or overladen sediment traps, should be reported to the Local Authority’s highways department. However, although a good starting point, Local Authorities are not responsible for excavating or maintaining all roadside grips – it could be done by private individuals living close by, or by the Parish Council (or a contractor working on their behalf).

Where hard surfaces, such as tarmac or concrete are due to be built or changed, consider using permeable surfaces that allow water to infiltrate, thus supporting the recharge of the aquifer and reducing surface runoff and the associated risks of flooding and pollution.

Wider land management practices that occur during a winterbourne’s dry phase can have a significant impact on its health – including flood risk– once the flow returns.

Two types of flooding occur from winterbournes: groundwater and surface water.

Surface water flooding is typically caused by rainfallinduced runoff or flows from upstream, often during or after intense downpours. The risks to local communities from surface water flooding can usually be managed using natural, low-cost methods, very few of which can be applied to groundwater flood management.

Groundwater flooding occurs when groundwater levels rise above ground level at which point the groundwater behaves like surface water. One manifestation of groundwater flooding is the emergence of winterbournes further upstream than usual, and springs ‘bursting’ in the surrounding landscape – a natural process, but one which can represent flood risk where development has encroached on the natural floodplain.

Excavating or dredging of winterbournes will not alleviate groundwater flooding and must be avoided. While water remains in the ground its flow is naturally slow. But when it emerges above the land surface it will behave as surface water – with flow pathways and velocities determined by topography. The sheer quantities of water emerging from

the aquifer can simply overwhelm the capacity of the drainage network. A deeper – dredged - watercourse will intercept the groundwater before a natural channel would do, and hence actually increases flood flows.

Recognising and accepting floodplain inundation as a natural and beneficial process is important. Flooding helps to create and fertilise soils, capturing carbon, ameliorating pollution, and sustaining ecology. In order to enjoy these multiple benefits, we want to increase flooding in the floodplain where it represents little harm to society and reduces flood risk downstream. Conversely, we need to reduce flooding where people and property are at risk.

Where flood risk to development applies in the natural floodplain, measures to slow the surface water flow should be considered, as they will reduce flood risk downstream. You could, for example, leave areas of floodplain unmanaged to provide a natural function during floods and, in the meantime, support a wide range of wildlife, and leave marginal vegetation and woody material in the winterbourne channel. These measures will slow the flow and, when levels recede, increase infiltration into the ground, rather than sitting on the land, helping to recharge water to the aquifer before the drier months arrive. This will increase resilience to both surface water flooding and drought.

If there is a high risk of surface water flooding to properties and the winterbourne is choked with vegetation, cutting a narrow, sinuous swathe through the in-channel vegetation will help improve water conveyance away from the location at risk, although downstream flood risk may increase.

Do not dispose of garden waste in or near a winterbourne, as this can create blockages that increase flood risk. Local Authority, Parish Council, and Environment Agency staff should also avoid letting cut material float downstream when cutting bankside and roadside vegetation.

Marginal and riparian plants are key to a healthy winterbourne. This vegetation helps to maintain water quality and provides a range of habitats and food sources for many invertebrates, birds, and small mammals. As the winterbourne dries, these plants spread into the channel. It is recommended to maintain a riparian buffer zone with a range of plants of differing heights, both for biodiversity and to intercept polluting runoff. Where this buffer zone has been removed, restoration can be considered. Planting ornamental and garden plants is not advised as many will not be adapted to the changing in-channel conditions, and some may become invasive.

Many winterbournes are devoid of bank-top trees and shrubs because of past clearance for fuel and pasture and now because of ongoing agricultural management. Willow and alder woodlands and areas of scrub would have been a natural and integral part of the habitat mosaic of winterbournes. Climate change is causing an increase in average and peak water temperatures and the frequency and intensity of heatwaves. Accordingly, planting trees and scrub is an increasingly valuable means of promoting chalk stream ecosystem resilience. Dappled shade helps to keep the stream water cool and reduces evaporation, thus mitigating climate change impacts.

Planting large tree species like oak, set back from the immediate bankside will, in time, afford valuable shade for grazing stock as well as cast shade over the winterbourne whilst planting scattered single and groups of trees immediately bankside, including willow, oak, hazel, black poplar and alder will provide shade in the long term. Planting clusters of bankside and riparian shrubs such as hawthorn, blackthorn and guelder rose will provide shade more quickly. Also consider planting areas of riparian woodland to restore this habitat feature to the landscape. Such areas can also add aesthetic interest to the landscape.

Care should be taken to create only dappled shade, as excessive shade limits aquatic plant growth. Where this occurs, judicious thinning to create a mosaic of woody vegetation providing dappled shade and more open areas will allow light to reach the channel whilst retaining the benefits of shade. Many of our native tree species can be pollarded with multiple benefits to wildlife. In addition, many bankside trees, such as hazel, hawthorn and elder can be coppiced which reduces shade and encourages strong regrowth of new shoots. Tree work including pollarding and

coppicing must not be done during the main bird nesting season which is from March-July, and checks for nesting birds should continue to be made through to September.

Woody material is vital to kick-starting natural processes. It creates variability in water depth and flow velocities, and forces water through the stream bed, supplying oxygen to invertebrates and fish eggs within the gravels. Wood also provides a substrate onto which animals (such as filterfeeding insect larvae or limpets) and plants can attach themselves. Fallen branches, brash, and especially whole trees should be left in the riparian zone and the channel; actively adding woody material to winterbourne channels is also highly recommended.

Winterbournes exist in a variety of landscapes: they flow through well-shaded wet fen, in which peaty soil overlays the chalk substrate, and through open sloping downland with thin topsoil, which is often over-grazed and consequently devoid of significant tree and vegetation cover. Both of these environments pose challenges for fish.

To support diverse fish communities, and the free movement of sediment, the course of any winterbourne must be free of barriers, such as weirs and sluices, which can restrict their movement of fish, including during migrations. Natural barriers to fish movement are rare in the stream bed of chalk streams, but artificial structures are common. Some of these structures are associated with historic water meadow irrigation systems, and thus sometimes have archaeological and heritage value. But where the meadow systems are no longer functional or of cultural value, it should be possible to remove or modify the structure. Even if you know of a barrier to fish downstream, it is still worth improving fish passage in your reach as that will mean your section of channel is ready to respond well if/when that downstream barrier is removed.

If you think trout might be spawning in your stretch of river, look for signs of trout redds (spawning nests in the gravel) and avoid bank or river work during the fish spawning season (i.e. December to March). It is a good idea to communicate this with your neighbours who may not be aware of this.

The in-channel base of culverts and farm bridges are often raised, with a distinct drop in the bed level downstream

that hinder fish passage through the structure itself. Ideally, culverts should be removed and replaced with clear span bridges.

Any step in the stream bed is problematic for the migration of small fish (e.g. juvenile trout, and bullhead), and even a drop of a few centimetres is likely to prevent them from repopulating a winterbourne after flow returns. Larger trout can negotiate smaller barriers, but any structure which requires the fish to jump upstream is likely to restrict their migration. Various techniques can help trout to overcome these barriers but the most effective is barrier removal. Professional advice on managing and ameliorating the impacts of in-stream structures is available from the Wild Trout Trust, Wildlife Trusts, Rivers Trust, and Environment Agency.

Very occasionally, natural barriers form in chalk streams such as a build-up of calcium carbonate (tufa) deposit creating a dam. Tree roots can meet across a stream or masses of fallen and standing tree branches can tangle together, forming a woody material dam; these are rare in winterbournes, but occur in some types of fen where willow proliferates and probably used to be far more common. These natural features are rare and should be left alone unless they are obviously compacted and impermeable,

as evidenced by a notable difference in upstream and downstream water levels. In such situations, easing out a water-level gap can allow fish – as well as other organisms and materials – to pass through a woody dam.

Maintaining a natural channel form and ensuring that there is linear connectivity, are crucial to maintaining a concentrated flow instead of shallow flows diffused across the floodplain where there is not a distinct channel. Ensuring that marginal vegetation is not strimmed or heavily grazed will also help to increase fish productivity.

Grazing livestock, including horses, in and around winterbournes requires careful management to minimise ecological impacts.

Low intensity grazing through the winter (with small numbers of livestock) is one option. The livestock need to be taken off ideally in March to allow a full season of vegetative growth and then are returned in the late autumn. Alternatively, short-term, intensive ‘mob grazing’ (with a much larger number of livestock) can be carried out in late autumn (October) and early Spring (March) for a maximum of one week each time. The livestock should be kept off the site for the remainder of the year.

Both of these options protect the river channel and the riparian zone during the main growth, flowering and seeddispersal phases.

Conversely, intensive grazing – whether in wet or dry phases – can result in bank erosion and soil/ground compaction, thereby increasing the risk of flooding and sediment pollution. If livestock faeces accumulate during their dry phases, winterbournes can also receive influxes of nutrient-loaded water upon the flow’s return.

Where intensive grazing cannot be avoided, fencing off access to the banks and riparian zone will allow a more structurally and species diverse sward of vegetation to form, providing habitat for wildlife, and intercepting fine sediment and other pollutants from reaching the channel. The fenced off area should be as wide as possible (we recommend at least 10 metres), because the width will determine how well it can act as a buffer zone for sediment and pollution. A wider area will also facilitate access to this riparian zone for low densities of livestock to mob-graze for 1-2 weeks per year. This selective grazing will result in increased diversity in vegetation structure and composition.

The flint and chalk fragments that form the bed of winterbournes streams is critically important to protect and, where it has been removed through dredging, should be replaced. Compaction of this substrate by machinery should be avoided.

The spaces between the fragments of chalk and flints that form the bed allow groundwater to flow upwards into the stream and surface water to flow downwards to recharge the aquifer. Water flows through these spaces longitudinally bringing oxygen to the fish eggs, invertebrates and other organisms within the bed. Plant seeds filter down and will germinate in these spaces.

Heavy machinery can compact the substrate, damaging the micro-habitat and inhibiting natural processes that sustain the special life of winterbournes. Avoid using heavy machinery in winterbourne streams e.g. farming machinery and robomowers.

Using strimmers with nylon cord leaves tiny fragments of microplastic in the channel, often invisible to the eye. Normal strimmer line can last for up to 600 years before it is broken down so these microplastics will be in the environment for centuries to come. Biodegradable strimmer lines are now available and are preferable to nylon cord, and hand pulling, although harder work, is a better choice for the environment.

Chalk streams are one of our most fragile and least resilient ecosystems and the winterbournes are at the sharp end of this, being particularly prone to the impacts of droughts and floods.

Winterbournes are often headwaters so are strategically a good place to start in any plan to restore and improve the catchment. The health of our headwaters helps to define the health of

the river downstream, so any improvements in the winterbournes are likely to positively impact the whole catchment.

Restoring winterbournes to their natural form and function will improve vulnerability and resilience and should be strategically prioritised in any catchment management plan.

Historic engineering had created a very straight, uniform channel, both in its longitudinal profile and its crosssection. The stream bed substrate, although still in situ, had been compacted by agricultural machinery. This restoration project aimed to create a naturally variable channel form in a roughly 600 metre stretch of winterbourne. This was to be achieved by subtly moving the existing stream bed substrate, rather than by importing new material.

A sinuous channel 1–2 metres wide and 0.25 metres deep was excavated within the existing channel bed. For some reaches this was a single low-flow channel and in other places it was a double channel, in effect, creating a chain of low islands in the channel bed. Seven hollows were excavated across 75% of the channel width; each was up to 0.5 metres deep and 3 metres long.

The excess soil and flint was heaped into crescent shaped berms (raised areas), creating reaches with contrasting flow velocities – fast and slow. These were located on alternating sides of the channel to create sinuosity, and were placed opposite each other when upstream of pools.

After the project was completed, the stream bed form within the pre-existing straight channel footprint became more variable in depth and width, with exposed flint gravels and a range of flow conditions.

No specific ecological pre- or post-project monitoring was conducted at the time, but a photographic record exists. Samples collected in 2019 contained the nationally rare winterbourne stonefly (Nemoura lacustris), which was first recorded in the UK in 2010.

The owner stopped driving machinery along the channel and maintained a regime of seasonal light sheep grazing.

Funded by the Environment Agency - £2,000. Managed by Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust. Led by Nigel T.H. Holmes.

This series of restoration projects aimed to reverse historic land drainage and agricultural impacts, kick-start a range of geomorphological processes, and create a range of natural winterbourne habitat features. Projects in 2009, 2010 and 2012 restored a total of 2.2 kilometres and created 400 metres of new winterbourne channel. Temporary ponds were created, and a further adjacent reach of winterbourne was restored in 2016 and 2018, with extensive riparian tree planting throughout that period.

Channels were re-excavated where they had become filled in with fine sediment through livestock trampling, or where the stream bed had been compacted by machinery. This recreated the dish-shaped cross-section and gently meandering longitudinal profile. In effect, the winterbourne was returned to its original course and form.

In one reach, where the winterbourne had been moved elsewhere in the floodplain, the old course was re-excavated and the flow was diverted back to that original course.

Riffles, pools, glides, wet berms, and gravel bars were created, and large woody material was incorporated into the channel. Most of the channel has been reconnected to the floodplain. A hectare of adjacent wet woodland was planted, and grazing pressure was reduced.

Three shallow seasonal ponds were excavated in the floodplain in 2016.

Prior to the works, exploratory excavations revealed that the original bed substrate was still in situ. As such, no new materials were imported to the site. The removed topsoil was used by the farmer elsewhere on the estate.

The targeted reaches of the winterbourne have been returned to their original course and form.

Aquatic invertebrate communities were sampled before and after works by the Freshwater Biological Association. Survey data indicated that the work was successful: rare and notable specialist winterbourne invertebrate species, which were absent prior to the project – were found only six months after the 2009 work was completed. The Community Conservation Index, which summarizes the richness and rarity of species in a sampled community, indicated that the restored sites had twice the conservation value of adjacent unrestored sites.

A site visit in January 2017 showed that the three seasonal ponds were filling with water, and wading birds including snipe were using the habitat.

The owner has stopped driving machinery along the channel, manages a regime of seasonal light cattle grazing, and undertakes no mowing.

Funded by the Environment Agency - £35,500. Managed by Dorset Wildlife Trust.

Channel pre-restoration

The Hamble Brook has been extensively modified over many centuries, largely through activities such as agricultural cultivation, ornamental landscaping, flood alleviation, and possibly milling. This has had a deleterious impact on its natural function and ecology.

The plan was to re-naturalise three reaches within a 1.1 kilometre stretch of the stream by increasing the hydromorphological variation, and improving connectivity with the adjacent landscape, through:

• Using cut and fill techniques to reintroduce sinuosity to the channel.

• Creating a narrow first-stage higher-energy channel, including pools and riffles, to encourage sediment mobilisation during low-flow periods.

• Create shallow, sloping berms to encourage the growth of marginal vegetation.

• Softening the gradient of the bank and, where practicable, removing previously dredged material from the bank tops.

• Sculpting two ponds to create a variety of water depths and slope gradients.

• Replacing one bridge to improve fish passage and reduce flow impoundment.

• Lowering the bank top at strategic sites to promote the flow of water from the channel into the adjacent landscape during high-flow periods.

• Improving the balance of light and shade through a combination of bankside tree and scrub management and planting native saplings.

Post project monitoring is on-going, supported by citizen scientists who have conducted a range of surveys including mammals, birds, plants, macroinvertebrates and physical habitats.

Funded by the Environment Agency - £50,000 - and the landowners - £46k.

Contractor: R.J.Bull.

Managed by the Chilterns Chalk Stream Project. Images by Adrian Porter.

Following centuries of physical modifications, relating to historic milling and water meadow activities, this reach of winterbourne had been diverted into a trapezoidal shaped ditch which was perched at the edge of the floodplain and bounded by a busy main road. As a result of the modifications, the winterbourne had become disconnected from its floodplain, was polluted by road runoff and had been overshadowed by trees and scrub. Sections of the abandoned paleo channel and water meadow drain still remained in the field but most had become lost. Only a 350m section of historic channel was still reasonably well defined.

The aim for this project was to restore floodplain connectivity to 1.2km of river using natural resources. This would result in a mosaic of winterbourne and floodplain habitats increasing biodiversity, improving natural flood management and creating an ecologically rich and diverse landscape. This was achieved by excavating a short reach of new channel, towards the upstream end of the site, creating a shallow linear depression in the floodplain which connected the ditch to the natural low point of the valley. The small amount of excavated material was placed as a bung in the roadside ditch, to divert flows into the old channel. Flows in the field were left to find their own course, in effect tracing the meander patterns of the original watercourse.

Monitoring data was collected by researchers from Nottingham Trent University in 2023 and 2024. Physical habitats were surveyed, aquatic invertebrates were sampled from the ditch (2023) and restored channel (2024), and terrestrial invertebrates were sampled from the restored channel’s floodplain. At the time of writing, data analysis is underway and funding is required to enable characterisation of the project’s longer-term effects.

The site is being managed under a Countryside Stewardship Mid-Tier agreement with a hay cut taken in the summer and extensive grazing in the autumn.

Funded by Thames Regional Flood and Coastal Committee (Natural Flood Management fund) - £50,000

Contractor: Cain Bioengineering

Managed by Action for the River Kennet (ARK). Led by Rupert Kelton. Images by Rupert Kelton.

Some winterbournes are designated as ‘main river’, and others are non-main river (ordinary) watercourses. This distinction determines which body regulates activities such as river restoration.

Under the Environmental Permitting Regulations any works on or within 8 metres of a main river are likely to require permission from the Environment Agency in the form of a Flood Risk Activity Permit (FRAP). For non-main river watercourses, permission may be required from the Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA), usually a county or unitary authority.

Landowners, managers or project leads are advised to contact both the Environment Agency and the LLFA consenting team at the pre-application stage, to confirm permitting/consenting requirements.

For large-scale projects, landowners should also discuss their proposals with the Local Planning Authority, to determine whether planning permission is required for any elements of the works.

The Environmental Permitting Regulations provide for different levels of permission depending upon the nature and risk of the works. Very minor works may not need permission or can be registered online as an exemption (i.e. specific works that do not need a FRAP). A standard rules permit might be required for medium-risk works, i.e. works for which the environmental risks from a specific discrete activity are known and so can be managed under standard rules. Works that do not fall within these lower-risk categories will require a bespoke application for a FRAP. Most river restoration works will require a bespoke FRAP.

The link below provides guidance on the different permissions available, the relevant application forms and access to the EA’s main river map for England.

gov.uk/guidance/flood-risk-activities-environmentalpermits

Where a winterbourne is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended), or is adjacent to a SSSI, then consent from Natural England is required to avoid harm and ensure that works contribute to achieving favourable condition.

The methods and metrics used to monitor perennial streams require adaptation for use in winterbourne reaches so that they accurately indicate ecosystem health. Biomonitoring data can then be used to inform both the maintenance of good quality habitat and the identification of sites requiring restoration. Monitoring of winterbournes has been rare until recently, but citizen science programmes now increasingly include winterbournes, for example the ‘MoRPh’ (Modular River Physical habitat) survey method has been adapted to include dry channels and their plant communities.

The Environment Agency has developed winterbourne monitoring protocols, recognising that we need better biological and environmental data and evidence to inform the management of winterbournes. A key difference compared to perennial rivers is the monitoring of both dry and wet phases. Details of these protocols will be available in 2026, but a few of the key recommendations from this are as follows:

Taxa including ground beetles and rove beetles (Carabidae and Staphylinidae) are considered good indicators of habitat quality. Beetle activity varies among families, with a common peak in April–June. If this peak coincides with a winterbourne dry phase, the channel is likely to support a diverse beetle assemblage. There is no one ‘best’ way to survey terrestrial invertebrates, but a 1-hour hand search can—after appropriate training—be effective and accessible to citizen scientists - 30 minutes spent searching in the channel and 30 minutes spent in the riparian zone. Use one or more of the following techniques to find beetles, depending on the habitats present:

• Trample or pat soft sediments, and poot observed insects directly.

• Splash exposed sediment at the water’s edge with water, where pools persist. This works best on steeper banks where a sieve can be used to catch insects washed into the water or beetles can be pooted as they run back up the slope.

• The basal parts of plants, stems and flowers are examined or pulled apart; tussocks can be closely inspected over a sheet or tray. Observed organisms are then pooted.

• Leaf litter and dense mats of fallen vegetation are sieved over a plastic sheet or tray, using a sieve ideally with a mesh of 4 to 8 mm.

• Emergent vegetation is submerged where pools persist and the insects that float to the surface are scooped up with a sieve.

• Large stones can be lifted, and large woody debris can be broken apart, before organisms are pooted.

Collect samples during the wet phase (flowing and/ or ponded) in spring (March, April or May) and autumn (September, October or November), annually.

Following standard kick sampling protocols should be adequate—3-min kick/sweep technique using a pond-net, supplemented by 1-min hand searching—although the interpretation of data needs to be adapted to account for the temporary nature of the sample site.

Plants should be surveyed once between May and September. For sites with water crowfoot species, surveys should be undertaken in May/June, when these species flower, to enable identification – in particular, to distinguish between Ranunculus peltatus vs Ranunculus penicillatus pseudofluitans. Terrestrial grasses flower in June–September, making them easier to identify in these months.

You should include the same survey area each time the site is surveyed—define the upstream and downstream extent of each site using a ten figure National Grid Reference.

You should take photographs of the survey area, at both the upstream at downstream extent, at the same location on each visit; this ensures the photographs are comparable between surveys. Take additional photographs of the survey reach, the channel, and its vegetation, especially if there is variability in physical habitat and flow habitat within the survey reach. Clearly mark on the photographs the survey area / boundary, to ensure the same survey can be repeated in future years.

Site visits to monitor in-channel state—ideally on the same day every month—to create over time a detailed understanding of environmental conditions, thus supporting interpretation of biotic data where possible on a comparable date each month. Take a photograph at the same location at each site, every month. Monthly

observations can be used to calculate the proportion of dry channel days in a year.

Additionally, the monthly observations can be used to help to schedule wet (flowing and ponding) and dry phases of associated biological monitoring. Record flow state in-line with standard flow categories (Table 1).

Table 1. ‘Flow type’ categories and description

Flow Type Description

Dry No surface water present

Damp/Wet No evident surface water but bed may be damp

Streambed No visible water, but the streambed is wet

Isolated Pools The only surface water present is in still isolated pools

Ponded / Still Water may be extensive or may connect pools but there is no flow

Low Flow Flow (velocity and/or depth) is below “normal”

Moderate Flow Flow (velocity and depth) is considered “normal” (will be different in different streams)

High Flow Water is flowing fast and is approaching bank full

Over-bank Flow Water has overtopped banks and is inundating adjacent land

Frozen Water is frozen from the surface to the bed

If resources are available, water quality parameters can be recorded using a multi-parameter handheld device, to help detect any stress associated with stream drying, extreme weather, or pollution incidents:

Record water temperature, Dissolved Oxygen (%), Dissolved Oxygen mg/l, Conductivity, pH and, if possible, other parameters such as ammonium (if available). Multi-meters will often display two determinants: NH3-N – Ammoniacal Nitrogen and/or NH4-N – Ammonium.

In summary, a robust monitoring programme for a site could include the following elements;

Invertebrates (wet phase)

Invertebrates (dry phase)

Modular River Survey (MoRPh)

Monthly flow observations and fixed-point photography

or when dry

– review requirements every 5 years

Advice on biological monitoring of winterbournes, in all their phases, can be obtained from the EA.

The global rarity of chalk streams and winterbournes means that local authorities have a responsibility to consider the effects of development on them. Plan makers should consider both chalk streams and winterbournes as part of plan making, whether it be through local or neighbourhood plans.

There is no explicit reference to winterbournes in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), but the NPPF does require plan makers to consider the following factors relevant to winterbournes:

• water supply and wastewater as key aspects of infrastructure to support the Plan

• taking a proactive approach to mitigating and adapting to climate change taking into account long term implications for water supply

• enhancing the natural and local environment by preventing new and existing development from contributing to, being put at unacceptable risk from, or being adversely affected by, unacceptable levels of water pollution

• encouraging development to help improve water quality, taking into account relevant information such as river basin management plans.

• protection and enhancement of sites of biodiversity value (commensurate with their statutory status or identified quality in the development plan)

The NPPF sets out requirements for Local Plans and decision makers to protect and enhance the natural environment.

The Planning Practice Guidance provides more detailed information on how Local Planning Authorities should consider water supply, wastewater and water quality in their Local Plans. The main focus is on ensuring that Plans have due regard to the relevant River Basin Management Plan.

When drafting a Local Plan, Local Planning Authorities should ensure that their plan accurately and adequately addresses the presence of chalk streams and winterbournes in their area. Rather than the inclusion of a single “chalk streams and winterbournes” policy, it is recommended that Authorities reflect on how the presence of chalk streams and winterbournes in their area should be interwoven throughout the Local Plan. Policies should consider habitat and species, sustainable drainage, water use and demand as well as impacts from site allocations. Development should avoid winterbournes in the same way as surface water floodplains – they naturally flood intermittently.

Neighbourhood plans contain planning policies related to locally specific issues. Where neighbourhood plan areas contain winterbournes, Parish Councils and Neighbourhood Forums should consider including detailed policies relating to buffer zones, water quality management relating to sustainable drainage solutions, water consumption and winterbourne improvements, such as renaturalisation or de-culverting. Opportunities for allowing people access to winterbournes and chalk streams should be encouraged – to experience the biodiversity and find tranquil space for wellbeing.

All development requiring planning permission is determined in accordance with the Development Plan (Local Plan) for the area, taking into account relevant material considerations.