How nature adapts in lean times

Honouring the people and projects leading the way for local wildlife WILDER AWARDS 2025

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Digital copies of Wild Life magazine are also available. If you would prefer to receive a digital copy, please email membership@hiwwt.org.uk and we will update your record.

In winter, the leaves may have fallen but the roots are actively storing energy for spring – reminding us that even in stillness, brighter days are ahead. In this issue, we observe the extraordinary ways wildlife endures, from the habitats that shelter life through the harshest months (page 26) to the winter warriors (page 22) – species that keep going no matter what.

This resilience inspires our own. At the Wilder Conference & Awards, we launched our refreshed Wilder 2030 Strategy, a renewed call to action for bold, systemswide change that puts nature at the heart of progress. At the event, we honoured our brilliant award winners and nominees – congratulations to everyone involved.

Turn to page 28 for an inspiring round-up of positive action these wildlife heroes are taking for nature.

Thanks to generous donations from a number of individuals we have been able to offer four traineeships – two in the ecology team and two in the reserves team. These posts allow us to reinvest in our talented teams on the ground, unlocking greater resources to protect our reserves.

On pages 18-21 we feature bats, symbols of adaptability, demonstrating how our work helps wildlife survive and thrive. But survival isn’t guaranteed, and your support helps ensure it. Thank you to all our members who continue to campaign for stronger protections so that development happens responsibly, working in wildlife’s favour. This is just one of the many ways your voices make a difference. Together, we are standing up for nature wherever it’s under threat.

The Trust has raised significant concerns over Associated British Ports’ Solent Gateway 2 proposals in Dibden Bay, which threaten internationally important wetlands and wildlife habitats. We will continue to monitor the proposals and push for an approach that safeguards the Solent’s integrity. Visit hiwwt.org.uk/ news/solent-gateway for updates.

Editor Sara Mills

Designer Keely Docherty-Lee

Registered charity number 201081. Company limited by guarantee and registered in England and Wales No. 676313. Website hiwwt.org.uk

● We manage 70 nature reserves.

● We are supported by over 29,000 members and friends, and over 1,400 volunteers.

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust is registered with the UK Fundraising Regulator. We aim to meet the highest standards in the way we fundraise.

Cover image Fox - Shutterstock

From making our voices heard to taking action on the ground, we help nature survive. We love sharing stories about people like Mathilde Chanvin, a Trust super champion who is transforming her community in Southsea through planting and greening. Her work inspires individuals to make a tangible difference in their neighbourhoods, strengthening community spirit and creating a deeper sense of purpose. Go to page 15 for more.

As a magazine, we too are embracing change. We’re refreshing our look and content – and we’d love your input. We’ll be selecting members to join a steering group to help shape the magazine’s future. If you’d like to be involved, please get in touch: editor@hiwwt.org.uk

So this winter, take a moment to notice nature’s quiet strength. Every act, large or small, helps wildlife survive, flourish, and prepare for spring. Through protection, restoration and community action, we will ensure the wild world continues to thrive. Thank you for making a difference. Your membership matters.

Sara Mills, Editor Email: editor@hiwwt.org.uk

You can change your contact preferences at any time by contacting Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust at:

Email membership@hiwwt.org.uk

Telephone 01489 774400

Address Beechcroft House, Vicarage Lane, Curdridge, Hampshire SO32 2DP

For more information on our privacy notice visit hiwwt.org.uk/privacy-notice

Please pass on or recycle this magazine once you’ve finished with it.

4 Your wild winter

The best of this season’s nature, including the versatile shrew.

8 Reserves spotlight

Discover an inner-city oasis at Winnall Moors Nature Reserve.

10 Wild news

Stay up to date with the latest Trust news and successes.

14 Team Wilder

How people and communities are pulling together for a wilder future.

18 On bat watch

How we are protecting roosting sites and feeding areas to boost numbers.

22 Winter warriors

We take a closer look at the way wildlife adapts to scarcity in the cold season.

26 Seeking sanctuary

From setts to redds – the habitats that mammals call home during the winter.

28 Wilder Conference and Awards

We reveal our refined 2030 strategy and shine a light on nature’s champions.

16 A word from our CEO

Reflections and strategy from Debbie Tann MBE, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust Chief Executive.

17 Six of the best

Six mysterious moths and their special abilities.

30 My wild life

Community Ecologist Susan Simmonds on the rewards of engaging people with wildlife.

The best of the season’s wildlife and where to enjoy it.

When winter settles in and insects vanish, some UK mammals either hibernate or slow their bodies to save fuel. The common shrew, Sorex araneus, however, keeps racing. This thumb-sized hunter has such a high energy need that it can’t afford a long nap — it must keep eating or it will die. So, instead of sleeping through the cold, the shrew changes itself.

First, it literally shrinks. Beginning in late autumn, a shrew’s skull, brain, and several internal organs get smaller losing up to one fifth of its summer size. With less tissue to warm and maintain, the animal’s daily fuel drops just enough to stretch the limited supply of winter insects and worms. Come early spring, everything starts to grow again until it is roughly its original size. Scientists call this reversible shrinking Dehnel’s phenomenon — nature’s version of turning down the thermostat until the weather improves.

Shrews also change their daily routine. In summer it defends territories fiercely, chasing off intruders to protect food stashes. In winter it relaxes slightly. Several shrews may overlap their feeding routes or share snug nests made of dry leaves under logs or in grassy tussocks.

By tolerating neighbours, each individual shrew spends less energy on fights and more on foraging. It feeds primarily on insects, worms, and other invertebrates, relying on a keen sense of smell and touch, as its eyesight is poor.

The shrew’s elongated snout and constantly twitching nose help it detect prey in the soil and under leaf litter.

There isn’t often heavy snowfall in Hampshire and the Isle of the Wight, but when it lays, finding food under snow is tricky for wildlife. The shrew exploits the ‘subnivean zone’ — the narrow airspace between soil and compressed snow. This hidden corridor stays just above freezing and is rich in dormant insects and larvae. Guided by a twitching, highly sensitive snout, a shrew zips through these tunnels almost nonstop, pausing only for brief naps of a few minutes.

Though a common shrew lives barely a year, its winter strategy is a masterclass in adaptability: shrink the body, share the space, and keep moving. Against icy odds, through relentless foraging, territorial instincts, and seasonal adaptation, this tiny creature embodies the raw, instinctual will to survive in nature’s complex web.

With their unique head rst climbs and habit of storing seeds for later, the nuthatch combines acrobatics with ingenuity – a small bird perfectly adapted to life among winter trees.

The woodlands may seem quiet in winter, but listen closely and you might hear the sharp, fluting “dwit-dwit” call of a nuthatch echoing through the trees.

HAVE YOU SEEN?

Sleek, playful and superbly adapted to life in water, the Eurasian otter, Lutra lutra, is one of Hampshire’s most charismatic mammals. Once in steep decline due to pollution and habitat loss, otters have made a remarkable comeback in recent decades, thanks to improved water quality, conservation efforts and the banning of chemicals. With streamlined bodies, dense waterproof fur and webbed feet, they are built for hunting fish, amphibians and crustaceans in rivers, lakes and coastal areas.

Otters remain active all year, including the depths of winter. They grow an even denser underfur for insulation, allowing them to slip into icy rivers without losing warmth. In hard freezes,

These striking little birds, with their slateblue backs and russet flanks, stay with us all year, and are especially active in the colder months.

The nutchatch, sitta Europaea, thrives in mature, broadleaved woodland, where it forages by creeping along branches and trunks searching for overwintering insects, seeds, and nuts. Unlike the woodpecker, it is expert at moving headfirst down the tree as well as up. Look for nuthatch at our Nature Reserves like Roydon Woods in the New Forest or St Clair’s Meadow in the Meon Valley, where plenty of deadwood offers the best winter shelter and feeding opportunities.

Territorial even in winter, nuthatch cache food in bark crevices and cover it with moss or lichen, returning when supplies are scarce. It relies on good memory and a ready supply of natural shelter – old trees, ivy-clad trunks, and undisturbed leaf litter – to survive winter’s toughest days.

While not rare, nuthatch are sensitive to habitat loss and woodland fragmentation. That is why restoring and connecting woodland habitats is so vital – not only for breeding birds in spring, but also for their survival through winter. This bold little bird, often spotted clinging upside down to a tree trunk, is a welcome reminder that life goes on even in the coldest months.

they may keep fishing holes open in frozen waterways, returning to them repeatedly. Winter’s bare riverbanks can sometimes make spotting them easier, though they still prefer the cover of overhanging vegetation or reedbeds.

The rivers Test and Itchen are excellent places to look for signs of otters. Visitors may find signs of their presence like spraints and footprints, along the water’s edge or tracks in mud or snow. They are known to frequent Blashford Lakes

Nature Reserve while coastal estuaries such as Langstone Harbour and the Lymington-Keyhaven Marshes can also be productive, especially at dawn or dusk. Watch patiently and quietly, staying downwind, for a sleek head breaking the surface or ripples marking their silent passage downstream.

Red squirrels make sharp “chuk-chuk” calls and high-pitched squeaks to warn of danger. Listen for these lively sounds echoing through the trees at Alverstone Mead on the Isle of Wight.

Take a dawn walk for golden light and active wildlife.

Bring a flask and sit quietly near a reedbed at sunset.

At dusk spot little owls perched on fence posts or old barns in open farmland and parkland – especially around Titchfield, Arreton, and East Meon – watching for prey with their bright fierce eyes.

Celebrate the magic of the colder months by tuning into the sights, sounds, and hidden stories of wildlife that thrives in winter. Here are some species to spot, sensory details to look out for, and simple ways to connect with nature, even on the frostiest days.

Start a winter nature logbook – noting sights, sounds, and changes.

Or join a guided winter wildlife walk to spot unusual sights –check the website for events!

Look for signs of pine martens in the quiet woodlands of the New Forest, especially around dense conifer, or mixed woodland near Brockenhurst and Bolderwood – early morning is best.

Witness the mesmerising swoosh and swirl of roosting starlings at dusk over Farlington Marshes, Fishlake Meadows, or Blashford Lakes, from late autumn through to winter on calm, dry evenings.

Even in winter, harbour seals ‘haul out’ of the sea to regulate their body temperature. See them resting on the sandbanks off Farlington and on sheltered shores and estuaries around the Solent.

Step off the bustling streets of Winchester and, within minutes, you’ll find yourself surrounded by birdsong and the clear, steady flow of a chalk stream. Winnall Moors Nature Reserve is a rare kind of wild place: a mosaic of wet meadows, reedbeds, and willow woodland lying right on the edge of a city. Managed by the Trust in partnership with Winchester City Council, this peaceful sanctuary is abundant with wildlife such as otters and kingfishers, warblers and roe deer.

At the heart of the reserve lies the River Itchen, one of the world’s most precious chalk streams. England has over 200 chalk streams – 85% of the global resource – and the Itchen is one of only 11 granted with the highest protection as a Site

of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and only four with European Special Area of Conservation (SAC) status. Fed by underground aquifers in the South Downs, its waters run crystal-clear, cool, and mineral-rich. This creates the perfect habitat for species that depend on unpolluted water: brown trout, grayling, and even white-clawed crayfish. Peer down from a bridge and you may spot shoals of fish holding steady against the current, or the sudden flash of a kingfisher streaking low above the surface. A network of smaller streams reflects the reserve’s past use as traditional water meadows.

While the river is the reserve’s backbone, the surrounding habitats are just as important. Seasonally flooded meadows burst into flower in late spring and summer, with orchids, ragged-robin, and meadowsweet creating swathes of

colour and scent. These damp grasslands attract clouds of pollinators and provide hunting grounds for dragonflies, damselflies, and swallows skimming low in the evening light.

Alder and willow line the stream banks, their roots binding the soil and creating shady refuges for fish and nesting sites for birds. In autumn, golden reflections shimmer in the water, fungi sprout in the damp ground beneath and careful coppicing ensures these trees remain vital parts of the wetland ecosystem. Reedbeds harbour reed buntings and sedge warblers, while water rails squeal unseen in the undergrowth. If you’re very lucky, you might hear the soft

plop of a water vole slipping into the water — one of the reserve’s most rare and treasured residents. During autumn, flocks of migrant long-tailed tits and goldcrests arrive to forage in the trees, while the last dragonflies patrol the meadows. As days shorten, otters sometimes become more visible, particularly around dusk.

Winter is a good time to look for siskins and starling murmurations above the reedbed, and to appreciate the remarkable clarity of the water.

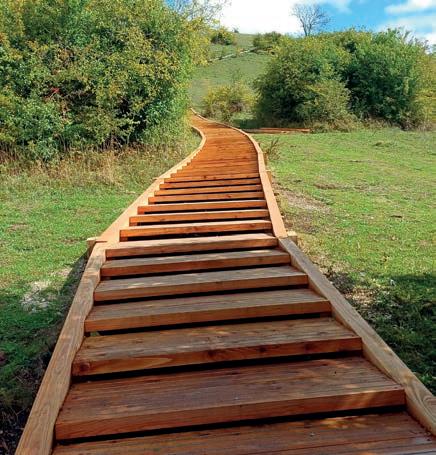

The Trust manages the reserve carefully to restore wetland habitats, improve water quality, and create space for species like water voles and otters to thrive. All this is only made possible by the vital support from volunteers. From monitoring wildlife to coppicing willows, clearing scrub, and repairing boardwalks, their work ensures the delicate balance of habitats continues.

Winnall Moors is more than a place to spot wildlife. It also plays a vital role in the health of Winchester itself. Wetlands slow the flow of water, reduce flood risk, filter pollutants, and improve the quality of the Itchen, providing a green corridor linking the city to the wider countryside.

Protecting the Itchen and its wetlands is especially important in a time of growing pressure from pollution, climate change, and development. Visiting the reserve is not only a chance to enjoy its beauty, but also to support its future: every membership, donation, or hour volunteered helps keep this city-centre haven thriving.

The new, well-surfaced, boardwalk

“Seeing people of all ages reconnect with this landscape is what makes all the hard work worthwhile.”

Samuel Martin, Reserves Officer

which was replaced this summer offers a smoother, more accessible route across the wet peat soil through the heart of fen. The sturdier new path gives space for families and friends to pause at resting points and take in views of reedbeds and wetlands. The level trails make it accessible to wheelchair users and families with buggies. Benches invite you to pause and soak up the surroundings. For many, it’s a lunchtime refuge or an introduction to nature for children – and a reminder that even in a city, wildness is never far away.

Access: Free entry, open all year. To protect wildlife, dogs are not allowed. No toilets or cafés on site; Winchester’s amenities are a short walk away.

Size: 64 hectares (158 acres) with 11 hectares (27 acres) open to the public. Location: Durngate Place, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 8DX, OS Map Reference: SU 490 306. Parking: Durngate pay-and-display or use the city’s park-and-ride; five-minute walk from Broadway. Getting around: One-mile flat circular path with boardwalk. For a longer 4.5-mile route, follow the Itchen Way east, cross at Fulling Mill, return via St Swithun’s Way. Footbridge and ramp access from North Walls Recreation Ground; five steps down to the reserve.

Trails: From Bridge Street, follow the water vole trail along the watercourse into the reserve.

With its bright blue and metallic copper colours it can be spotted sitting on low-hanging branches over the water.

Otter

This elusive mammal is one of our top predators feeding on fish, waterbirds, amphibians and crustaceans. It needs clean rivers with an abundant source of food and plenty of vegetation to hide in.

The brown trout lives in fast-flowing, stony and gravelly rivers. This predatory fish feeds on insect larvae, small fish and flying insects.

This year, The Wildlife Trusts (TWT) and other environmental organisations have raised the alarm over risks to wildlife from rollbacks in environmental safeguards, threatening our most precious places. The UK Government has been considering major changes to the planning system through a new Planning and Infrastructure Bill and proposals to weaken Biodiversity Net Gain – the requirement on developers to leave nature in a better state than before.

house building. Locally, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust also submitted evidence to the Bill Committee, drawing on the success of the Solent’s nitrate market within the existing regulatory framework.

requirements for development sites. This could

Despite promises of a ‘win-win’ for development and the environment, early readings of the Bill looked set to strip away protections and remove requirements for developers to avoid harming nature. In response, TWT launched the Broken Promises campaign, meeting MPs across the counties to highlight the lack of safeguards and the risk of regression in law. During the Climate Coalition ‘Lobby Week’ members raised concerns with their MPs, and over 30,000 Wildlife Trust supporters emailed calling for unsafe parts of the Bill to be withdrawn and for the Government to stop claiming nature protections block

Thanks to member support, some progress has been made. Government amendments were added in July to deal with some, but not all, concerns. These were accompanied by a statement recognising that nature protections are not a barrier to growth. During October, the House of Lords added a number of crucial amendments to the Bill, including some which would limit the risks to wildlife.

However, these have been rejected by the Government meaning the Bill will now enter parliamentary ‘ping pong.’ We are still seriously concerned about the risks to nature from this Bill, which will take us backwards in terms of protections (forbidden under ‘non-regression’ agreements with the EU).

requirements for Biodiversity Net Gain by exempting small development sites. This could allow 97% of applications to avoid any requirement, making this ground-breaking policy virtually meaningless.

According to new research by the Environmental Economics Consultancy (eftec), this could change could cut funding for nature’s recovery by around £250 million a year.

We expect further policy changes will come forward aimed at speeding up development, such as changes to the Habitat Regulations themselves and steps to make legal challenge more difficult.

Deregulation pulls the rug from under green investment and the hope of a thriving economy – a case we will keep making to decision-makers.

parts of the Bill to be withdrawn and

(forbidden under ‘non-regression’

Alongside the Planning Bill, the Government is also proposing to relax

As we publish, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill is in the final stages of debate before becoming law. For the latest updates, visit: hiwwt.org.uk/ planning-and-infrastructure-bill

The Trust has raised concerns over Associated British Ports’ (ABP) proposals for Solent Gateway 2, warning the plans could damage sensitive wildlife habitats.

The proposals include a new automotive terminal on reclaimed land between Marchwood and Hythe, plus a jetty, road infrastructure and a country park.

The Solent and surrounding sites, including the New Forest, are of exceptional ecological importance. They support breeding and wintering birds, nationally significant invertebrates, and carbon-storing habitats such as saltmarsh and seagrass.

The Trust is particularly concerned that the port expansion would encroach on Dibden Bay Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), harming nationally rare species, including breeding birds such as lapwing. The project could infringe on more than 100 hectares of the SSSI – an unprecedented level of development incompatible with its protected status.

Debbie Tann MBE, Chief Executive, said: “The Solent and the New Forest are already under significant ecological pressure, with many habitats and species in long-term decline. Further development must not push these ecosystems beyond recovery thresholds. We are advocating strong safeguards and offering advice to ensure impacts on wildlife, habitats

Above: Waders such as grey plover are at risk at Dibden Bay.

and the proposed country park are fully considered.”

The Trust also warns that the development would affect the Solent and Southampton Water Special Protection Area (SPA), an internationally important refuge for tens of thousands of wintering birds, including dark-bellied brent geese, with potential knock-on effects on nearby protected sites such as the Hythe to Calshot Marshes SSSI and the New Forest National Park.

Strict adherence to the mitigation hierarchy is essential for any proposals: developers must avoid harm first, reduce impacts second, and only as a last resort provide replacement habitat.

The consultation on Solent Gateway 2 closed on 13 October 2025, with a statutory consultation expected in 2026. For more: hiwwt.org.uk/news/solent-gateway

A nationally scarce moth has made a welcome return to a South Downs reserve.

The striped lychnis moth, Shargacucullia lychnitis, has successfully bred on-site thanks to habitat work by the Trust. The caterpillars (inset), with their bold black and yellow stripes, rely entirely on the wildflower dark mullein, Verbascum nigrum. Targeted management has helped this plant spread across the reserve in recent years.

Fi Haynes, Reserves Officer, said: “It is brilliant to see striped lychnis moths colonising a reserve near Winchester. While still low in numbers, the increase in

dark mullein gives real hope for the future.”

• You can help too: dark mullein is easy to grow from seed, providing food for caterpillars as well as nectar for pollinators and seeds for birds. For best results, start seeds in trays to grow plug plants before planting out, rather than sowing straight into wildflower areas. Sow in autumn or spring, and enjoy its tall yellow flower spikes as part of a wildlifefriendly garden.

Tracey Middleton, Membership and Supporter Assistant, has completed the 50k Run to the Sea Ultramarathon, raising £1,128 for The Trust. Starting at Moors Valley Country Park and finishing along Bournemouth seafront, Tracey covered around 30 miles of forest trails and coastal paths in seven hours and 20 minutes.

Tracey, who has worked for the Trust for three years, said she kept noticing nature to inspire her to keep going. She added: “Nature is so important to me; I wanted to raise awareness and vital funds for the Trust’s work, and help create a wilder future.”

Support Tracey: justgiving.com/ page/tracey-middleton-1

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Michael Baron, one of the Trust’s Vice-Presidents. An early and dedicated member, he served for many years on Council as Trustee and Chair, making a lasting contribution to the Trust and to wildlife conservation.

Our heartfelt condolences go to his family and friends.

A rare splash of colour arrived on our shores this winter! A small flock of glossy ibis, Plegadis falcinellus, with their shimmering green and purple feathers, were sighted by rangers from Bird Aware Solent in the Titchfield and Meon shore areas. The birds have journeyed all the way from southern Europe.

The Trust has recently completed important habitat restoration and road-safety improvements at Hook Common and Bartley Heath Nature Reserve in north Hampshire. The works were designed to restore rare wooded heath habitat while improving safety along the A287 dual carriageway that borders the site.

Wooded heath is one of the UK’s rarest habitats, supporting species such as adders, tree pipits, ground-nesting birds and specialist plants like heather. To help this fragile ecosystem recover, the Trust carefully cleared around three hectares of dense birch and scrub from woodland edges. This created open glades and

sunny margins where heathland plants can regenerate, while also providing valuable nesting and feeding habitat for birds and invertebrates.

Only selected trees, mainly birch and aspen, were removed, following thorough ecological assessment. While the work initially looked dramatic, it was essential

a

route to the

thanks to the replacement of the reserve’s iconic steps. The new structure secures access to this muchloved Iron Age Hillfort while protecting its fragile chalk grassland - home to the

silver-spotted skipper, as well as frog orchids, bastard toadflax and a variety of invertebrates.

The old steps had deteriorated, often forcing walkers onto damaging alternative routes. The new timber steps, with an anti-slip surface, provide a secure, long-lasting route expected to last three decades, reducing the need for frequent repairs.

Construction was carried out with great care. All materials were carried by hand to prevent vehicle damage, and a small buffer zone on the wildflower meadow was used to store materials. This temporarily paused new growth but will naturally recover next season.

for restoring a more diverse and resilient landscape that benefits wildlife. All activities were fully licensed and overseen by ecological specialists. With the project now complete, the reserve is in a stronger position to support its rare species and offer visitors a richer experience of this special environment.

A redshank ringed at Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve in 2013 has resurfaced at RSPB Leighton Moss Nature Reserve in Lancashire — making it nearly 13 years old, far beyond the species’ usual lifespan of four years. Spotted by amateur ornithologist Richard du Feu, the bird underlines the importance of UK wetland networks and long-term ringing studies. Redshank is amber listed, with breeding numbers down 45% in 30 years.

Community Infrastructure Levy

The project has been supported by Winchester College as landowner, with consents from Historic England, Natural England and the South Downs National Park Authority. Funding came from the Park’s Community Infrastructure Levy and a generous legacy gift.

Large numbers of redshank fly here from Iceland to spend the winter around our coasts.

The Trust is very grateful to both.

A major conservation project is underway near Tangley, north of Andover, to secure the future of the endangered, white-clawed crayfish, Austropotamobius pallipes the UK’s only native crayfish species. Once abundant in Hampshire’s chalk streams, populations have collapsed since the 1970s driven by a combination of habitat loss, pollution, and, crucially, the introduction of invasive non-native signal crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus, and the crayfish plague they carry.

new population of our native crayfish. Their establishment locally is a fundamental aim of our conservation work to secure the long-term survival of white-clawed crayfish within Hampshire.

Seagrass planted earlier this year in the River Hamble is taking root, marking a historic return for one of the UK’s most threatened marine habitats.

The Trust’s marine team sowed over 2,000 seeds and now healthy plants are growing in the estuary –the first signs of a comeback for a habitat lost from the Hamble since the 1920s and ’30s. Once stretching from Southampton Water to Bursledon, seagrass was wiped out by a wasting disease in the 1930s. A 2023 survey found no remaining beds in the Hamble. Nationally, up to 92% has been lost through pollution, dredging, anchoring and development.

“Seeing seagrass growing again in the Hamble was truly emotional,” said Tim Ferrero, Senior Specialist, Marine Conservation at the Trust. “For the first time in living memory, it’s back. These tiny seedlings, flowering and producing more seed, give me so much hope.”

To help protect the species, a purposebuilt “ark site” is being created – a safe, isolated pond designed to support a

The site will be closely monitored to ensure water quality and habitat conditions are suitable before crayfish are introduced. If successful, it will bolster the resilience of local populations to existing threats and the potential impact of climate change, and could even provide stock for future reintroductions.

*The project is being delivered at a private site with support from a private landowner through the Watercress and Winterbournes Landscape Partnership Scheme funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Match-funding also being provided by the Test and Itchen Catchment Partnership’s Ecological Resilience Fund (supported by Southern Water), North Wessex Downs National Landscape, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, and Test Valley Borough Council.

Emma Hunt, Senior Reserves Officer, said: “The display of flowers this year was absolutely incredible. This tiny but mighty reserve is proving how even the smallest spaces can have big impacts for biodiversity when managed sensitively.” SPECIES RECOVERY

Seagrass meadows are vital nurseries for fish, cuttlefish and rays, and capture carbon, helping to tackle climate change. The seeds were collected in autumn 2024 from Langstone Harbour with volunteers, stored over winter and planted using Dispenser Injection Seeding – an innovative, low-disturbance method that places seeds directly into the seabed.

The Hamble work is part of the Solent Seascape Project, a partnership restoring seagrass, oyster reefs, saltmarsh and seabird nesting habitats across the Solent. Turn to page 14 to discover how volunteers are helping this project thrive.

One of the world’s smallest Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) has seen one of the rarest UK plants make a comeback. Around 10,000 field cow-wheat plants were recorded at St Lawrence Field Nature Reserve on the Isle of Wight this summer, marking one of the strongest years since its population peaked in 2021.

Team Wilder invites everyone across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight to take part in our Winter Survey Challenge — the next phase of our Citizen Science project. After a summer of spotting everything from red kites to tortoise bugs, we’re now asking people to record the wildlife they see this winter using Survey123, a simple digital tool. From garden birds and fungi to fox tracks in the snow, every sighting helps build a richer picture of how wildlife weathers the cold months and reveals the hidden stories of our resilient local nature.

● Every record counts, and the stories and photos shared bring our collective wildlife map to life. Visit: hiwwt.org.uk/get-involved/ citizen-science

It has been a record year for our Solent Seagrass Restoration and Solent Seascape Projects, with more volunteers than ever before joining us to help restore one of our most important coastal habitats.

Across the summer we hosted 24 seed collection events – 15 at Seaview on the Isle of Wight and nine at Calshot – where volunteers donned snorkels and waders to gather seagrass spathes while enjoying the meadows’ stunning marine life.

We also tripled last year’s volunteer record, logging over 600 hours (up from 226 in 2024) – an incredible effort that is helping to bring back this vital habitat.

The collected seed (from the common eelgrass, Zostera marina) is now being processed at the University of Portsmouth’s Institute of Marine Science to allow the seed to mature. A new system using large seawater tanks and modified garden trugs has made separating seed from the plant quicker and more efficient. Once cleaned, the seed is placed into cold, high-salinity

storage to keep it healthy and dormant over winter – ready for planting in spring.

With extra help from our Solent Seagrass Champions, we sorted and counted an additional 13,000 seeds to complete the separation process, bringing the total now in storage to an incredible 160,000.

Thanks to our dedicated volunteers and supporters, the future of Solent seagrass meadows is looking bright.

Forest School isn’t just for sunny days. In winter, children wrap up in waterproofs and woolly hats to discover the magic of bare trees, storm-blown leaves and rain-splashed adventures. Fires provide warmth, hot drinks and a sense of togetherness, while puddles, mud and makeshift shelters spark play and resilience. Winter Forest School helps children tune into their senses – from listening to the sound of rain and calls of winter birds to handling conkers, holly

Left: Forest School Leader Debbie Cunningham with youngsters ready to take part at Swanwick Lakes.

and acorns – reminding them that every season has its gifts.

For more details about how and when to join, visit hiwwt.org.uk/forest-school

“Resilience, curiosity and joy grow outdoors – whatever the weather.”

Trainee Assistant Training Officer, Abi Gibbard

Mathilde lives in Southsea and works as an Art Engagement O cer at Portsmouth Museum and Art Gallery. An ambassador for wildlife and Super Champion for the Trust, she is also active in our Wilder Portsmouth project and volunteers with the Portsmouth and Southsea Wildlife Watch group.

You’ve lived in some diverse places. I grew up and studied in France, then joined an NGO project in the Prespa National Park in northern Greece, delivering arts and environmental activities for children. The area was so wild and beautiful, and it was a joy to help the communities to appreciate and care for it. Then I worked in the tropical rainforests of Sulawesi island in Indonesia, raising environmental awareness in schools. I came to Portsmouth in 2012, focusing on education and community work while gaining skills as a learning support assistant in my son’s school. How did you become involved in conservation here?

I joined the Trust in 2016, helping with Forest School and activities at Milton Locks and Swanwick Lakes, as well as school visits to Wicor Primary in Portchester. I also coordinate Portsmouth and Southsea Wildlife Watch, a family group that meets monthly for outdoor games and crafts, beach events and bat walks. In 2021, wanting more green space locally, I helped set up the Fawcett Road Greening Group. It started with neighbours and councillors in

Portchester. I also

the local pub, talking about how to bring nature to the area. With support from Andy Ames, the Trust’s Wilder Community Support Officer at the time, we had the tools and encouragement to begin. We won small grants, filled forecourts with planters, trees and swift boxes, and organised community events. The group grew through Facebook, which helped us expand greening in the neighbourhood.

What has been the impact of the group?

When we’re planting or watering, families stop to smell the lavender or watch butterflies and people stop to chat. These small things make people happy and connect them to nature. With more trees and flowers, the neighbourhood has changed for the better. Now local businesses, the church, school and community centre are involved. It brings people together and shows that small steps can build into something bigger. Even a windowsill planter can make a difference. It’s not easy when people are busy, but it’s about creating opportunities to get people involved where they live, work, and spend time.

What are your next plans?

Becoming a Super Champion for the Trust means I can do even more for the city. Our greening work has inspired others, and now we’re in a position to help people replicate what we’ve achieved in their own areas.

If you would like to make a difference, start a local group or become a champion, visit hiwwt.org.uk/ team-wilder

Inspired by nature on their doorstep, Mansbridge Primary pupils worked with Hampshire Poet Laureate Damian KellyBasher to create a joyful collection of wild poems capturing the colours and textures of the natural world around them – a true celebration of Team Wilder in action.

● Local businesses, B Corps, and environmental supporters joined a nature-focused networking event on the Isle of Wight, co-hosted by the Trust and B Local Hampshire, Dorset and Isle of Wight.

The day began with a tour of The Garlic Farm, led by director Barnes Edwards, highlighting their nature-positive farming practices. Attendees learned about mob grazing for soil health and sustainable garlic production, along with the farm’s WET system — a wetland filtration solution that purifies wastewater for crop irrigation.

Afterwards, there was a panel discussion, networking and a guided tour of Little Duxmore, the Trust’s rewilding site.

● A huge thank you to the latest corporate members to confirm their membership renewals: WightFibre Ltd and Hildon Ltd It is wonderful to have this vital support for another year and we look forward to working with them again.

We’d also like to thank our newest corporate members DHI Water Environments (UK) Ltd and Aviva Plc. We look forward to exploring some exciting opportunities together in the coming year.

We welcome interest from local businesses in joining our growing network of corporate members. This is a great way to support nature’s recovery and develop a deeper relationship with the Trust.

● For more information on corporate membership or supporting the Trust through your business, please contact corporates@hiwwt.org.uk

Debbie Tann MBE, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust Chief Executive, shares her

views on the region’s most urgent nature and climate challenges.

“In recent months, there has been a noticeable rise in anti-nature rhetoric, with many in the Government trying to sell a false story of nature being a problem. Newts, bats, snails and spiders are being blamed for the housing crisis, painted as a barrier to economic growth. This is a deliberately misleading narrative, using a cynically chosen group of species that could be found in a witch’s cauldron.

Sadly, this latest attack on nature is not new; wildlife has been used as a scapegoat for failures in the system for decades, with successive governments trying to weaken nature protections in the name of growth. It needs to stop.

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill looks set to fundamentally change the way nature is protected in England. Proposed powers could allow ministers to override existing safeguards or let developers buy their way out of responsibility for local habitats – which we have dubbed “cash to trash” in much of our campaigning. We hope the Bill will be improved as a result of months of lobbying and campaigning (including some welcome interventions by the House of Lords). However the ongoing quest for growth will bring further threats to our beloved wildlife, unless something

more fundamental changes.

That’s why our refreshed Wilder 2030 Strategy calls out this false story about nature getting in the way of economic growth and tells a truthful one. We know that nature isn’t the problem – and in fact it is a solution to many issues facing us today. Wetlands reduce flooding. Trees clean our air. Earthworms keep our soils healthy. Green spaces support our health and wellbeing. Indeed, our pioneering naturebased solutions work in the past five years has demonstrated incredible benefits of nature recovery not only for wildlife, soil health and pollution reduction, but also for the economy. When we lose nature, we lose the systems that protect and sustain us, as well as undermining our security and prosperity.

Our refreshed strategy gives us the opportunity to readjust our goals, realign our efforts and push further, faster, towards a nature-positive society. The next four years must be about systems change – restoring wildlife, repairing soils, cleaning water, and supporting jobs and wellbeing in ways that regenerate rather than deplete our natural world. We believe that transformative change is possible when people work together, and that if we can show the benefits of nature to the economy, to our health and

Left: The cover of the refreshed Wilder 2030 Strategy. Main image taken from The Wildlife Trust’s #CashToTrash campaign.

to our long-term security, this will help tip the balance in favour of change. Thank you for your ongoing support as we strive to create a wilder world for us all. Read more: hiwwt.org.uk/our-strategy

Debbie Tann MBE, Chief Executive

Debbie Tann MBE

camouflage

Rather than blend in, the stunning garden tiger moth chooses to stand out and its bright colours aren’t the only loud thing about them. When threatened they can rub their wings together to make an unpleasant rasping noise to deter predators. The caterpillars stand out too, with long mohawk-style hairs that irritate predators.

Rocking the military camouflage look, the lime hawk-moth is fast and aerobatic with scallop-edged wings that help conceal it from predators. With a wingspan reaching nearly 8cms, it is the largest moth on this list and one of the larger moths in the UK. The large, green caterpillars have a rhinolike horn at the tail end.

Often referred to as Darwin’s moth, the peppered moth is one of the best-known examples of evolution by natural selection. In woodland, its white, speckled wings blend perfectly with lichen-covered trunks, but during the Industrial Revolution, a dark form thrived, better camouflaged against soot-blackened trees and walls.

The master of camouflage, the buff-tip perfectly disguises itself as a broken silver birch twig. The caterpillars are large, hairy and yellow with a black head and a ring of short black stripes –a vivid warning to predators.

The white-ermine takes its name from the white-do ed fur traditionally worn by royalty. Its lack of camouflage is offset by a chemical defence toxic to predators. As caterpillars they group together, weaving intricate silk webs that serve as protective shelters.

While the cold forces most moths to stay inactive in winter, the December moth is well equipped to keep going. Its thick, fur-like scales provide insulation, keeping it warm and allowing its flight muscles to work as efficiently in winter as the other moths do in spring and summer.

Bats have ruled the twilight skies for over 50 million years, but climate change and habitat loss are threatening their survival. Discover how these elusive creatures live, the challenges they face, and how you can help them thrive.

Bats are wondrous. Agile and incredibly efficient, they’ve carved out a nocturnal niche – feeding on insects under cover of darkness, with fewer predators and less competition from birds.

As the only mammals capable of true flight, bats use their wings – thin membrane stretched across elongated fingers – giving them remarkable manoeuvrability. While they have good vision, bats rely on echolocation to navigate – emitting high-frequency calls and interpreting the returning echoes to “see” with sound. Some, like the long-eared bat, make quieter calls to avoid detection by prey like moths.

Essential to ecosystems, bats are important insect pest controllers for farmland and gardens as they consume huge numbers of insects. A single pipistrelle bat, for example, can eat up to 3,000 midges in a night. Using aerial hawking, they snatch prey mid-flight and eat on the wing.

When not flying, bats are roosting –resting in tree hollows, under bark, or in buildings like barns, cellars, bridges, and attics. In Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, they have been found in railway tunnels

and even in old air raid shelters. Summer roosts provide shelter for breeding females; winter roosts offer the cool, humid conditions needed for hibernation. This occurs around mid-October when nights get colder and insect numbers drop and lasts until March-April.

Bats are hugely resilient too. Data collected over the past 25 years suggests that bat populations have actually held steady and, in some areas, even increased due to robust legislation and conservation efforts. However, potential policy changes could change all this. Bats’ foraging grounds and habitats – such as woodland edges, meadows, riversides, and wetlands –could be under threat once more from urban developments which can fragment the landscape, while artificial lighting can disrupt bats’ nocturnal feeding and commuting routes. In addition, the use of pesticides in farming reduces the abundance of insects they rely on and climate change adds further pressure, altering insect populations, shifting seasonal food availability, and in some cases dry out the wetland habitats that support rich feeding grounds. These pressures make our work even more vital.

The Trust manages key habitats for bats across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, supporting all 17 breeding bat species recorded in the United Kingdom, each present to varying extents within the region. Our conservation work protects both roosting sites and rich feeding areas.

Old trees make ideal bat roosts – but they’re often removed for safety or aesthetics. Where safe, we retain standing deadwood like old oak trees, which develop cracks, cavities, and lifted bark – ideal for bats.

When tree work is needed, licenced ecologists inspect roost features using torches and endoscopes, returning at night to assess further using detectors and infrared cameras, ensuring any action is guided by bat presence and legal protections.

We install bat boxes to provide safe roosts where natural sites are lacking. In areas rich in chalk streams, boxes offer shelter near key foraging areas. In 2022, as part of the Watercress and Winterbournes Landscapes Partnership Scheme, we helped install 65 bat boxes in the Alresford and Ovington areas.

Bats thrive where insects are abundant. We manage flower-rich grasslands and encourage grazing by livestock, whose dung attracts insects like beetles – food for bats such as the greater horseshoe. Locating these habitats near known roosts means bats expend less energy reaching food – especially important for breeding females.

For over three decades, the Trust has surveyed bat populations to understand which species are present and how they use our reserves. As methods and technology evolve, our insights continue to grow.

We begin with daytime assessments of trees for potential roost features, using endoscopes to look for signs of occupancy.

At night, we walk transect routes with handheld detectors to record bat calls – identifying species and behaviour like feeding or commuting. The timing and pattern of activity can suggest proximity to roosts.

Working with licensed ecologists, we occasionally catch bats using mist nets or harp traps, attaching a temporary radio tag to track their movements. This helps locate hidden roosts and understand landscape use.

Another way of surveying bats is using a harp trap. Chris Challis, Assistant Reserves Officer at Pamber Forest, explains: “A licensed bat handler surveys bats using a harp trap (like the one pictured). It’s made of a frame strung with fine, taut lines—similar to fishing line—with a canvas bag underneath. The trap is placed in a narrow habitat corridor, ideally beneath

overhanging branches, so that bats flying along cannot easily avoid it. When they hit the lines, they drop gently into the bag, which the surveyor checks regularly— about every 20 minutes, depending on temperature and conditions.”

The trapping and handling of bats is strictly limited to licensed individuals to

protect both the animals and people. Welfare measures include wearing gloves and face masks to prevent injury and reduce the risk of disease transmission.

Static bat detectors, which record calls triggered by sound, have transformed our survey work. Unlike transect walks, which offer monthly snapshots, static devices record across multiple nights and seasons – giving a more complete picture.

Advanced acoustic analysis means more species can be confidently identified from their echolocation calls – including rare ones that may have previously been missed.

Common pipistrelle – Our smallest and most common species, emerging at dusk.

Daubenton’s bat – Flies low over water, scooping insects with its feet.

Brown long-eared bat – A late flyer, using its large ears to hear faint sounds.

Noctule bat – One of the largest UK bats, often seen over open fields.

Barbastelle bat – A rare woodland specialist with a pug-like face.

● Roydon Woods Woodland habitat for barbastelle bats.

● Blashford Lakes Greater horseshoe bats use this site around hibernation.

● Winnall Moors Watch Daubenton’s bats feeding over the River Itchen.

● Pamber Forest Mature trees with cracks and holes are perfect for woodland specialists like barbastelle and noctule.

● Alverstone Mead (IOW) See common pipistrelles and serotine bats forage over the Mead.

● Eaglehead and Bloodstone Copse (IOW) This ancient woodland provides Bechstein and noctule bats great habitat for these tree roosting species.

Over the past 30 years, surveys in Pamber Forest have consistently recorded common species like brown long-eared, pipistrelle and noctule. But in 2024, static detectors revealed four other species present on site: Leisler’s, serotine, Nathusius’ pipistrelle, and barbastelle – dramatically expanding our understanding of local bat diversity.

“These bats were likely here all along,” said Graham Dennis, Pamber Forest’s Reserves Officer. “But it’s only through recent technology and focused management that we’ve been able to confirm their presence and identify bat ‘hotspots’ created through habitat work.”

Above: Leisler’s bat, one of the latest bats to be confirmed living in Pamber Forest.

We regularly host bat walks and talks during the summer – offering the public a chance to see bats in action, learn about their behaviour, and understand more about why they matter.

To find out more about bats, visit: hiwwt.org.uk/wildlife-explorer

As frost grips the fields and trees stand bare, the countryside can seem hushed and lifeless. Yet look closer and you’ll find winter warriors all around – creatures enduring the cold, adapting to scarcity, and thriving through the darkest season.

Even after their leaves die, many young oak trees hang onto them all winter long — a phenomenon called ‘marcescence’. Scientists think this might be to help the tree recycle nutrients when the leaves finally fall in spring.

Winter can be a time of hardship, yet for certain wildlife it is also a season of opportunity – when predators hunt more freely, hardy plants sustain hungry mouths, and resilient creatures show just how well adapted they are to Britain’s chill.

Take the robin, its flame-bright breast seems even more vivid against bare branches and snow-dusted gardens. Far from retreating, robins claim their territories with defiant song, a melody that carries through the stillness of winter days. They are bold companions to gardeners, watching closely for the chance to snatch an unearthed worm.

eat. These periods of time are known as winter lethargy. As they rest, their body continues to function by using the energy in those fat reserves.

Beneath the frost, voles keep to their hidden runs, safe from the chill and the kestrel’s gaze. Here they feed and rest, sometimes lapsing into brief dormancy as the cold deepens.

Warmer winters and earlier springs can disrupt the sleep of hibernators like bats, dormice and hedgehogs, causing them to wake without sufficient food. The imbalance of time between activity and the availability of food, potentially disrupts ecosystems. Warmer weather late in the winter or early in spring also confuses fish, amphibians and reptiles which change their body temperature to match their surroundings. Butterflies like red admirals and small tortoiseshells, along with other insects, can also be tricked into emerging early. Without nectar to refuel, they risk exhausting energy reserves, leaving them vulnerable if cold weather returns – with potentially disastrous consequences.

Traditionally, cold winters with deep freezes help control tick populations by killing off many adults and nymphs. But milder winters allow more ticks to survive until spring, while earlier warmer weather gives ticks longer to search for hosts and reproduce, increasing the risk of tick-bourne illnesses like Lyme Disease.

calls carrying across frosty nights as

In the deep chill of winter, the fox wears a thickened coat like a cloak of survival. Though a skilled hunter, it turns scavenger when pickings grow slim, slipping into cities, villages and farmyards in search of scraps. Winter is also a season of renewal: between January and March foxes pair and breed, their yipping calls carrying across frosty nights as territories are staked and defended.

All autumn long, the squirrel caches food, tucking away seeds and nuts in secret stores. In the grip of winter, it slows into torpor, curled against the cold, waking only to feast on its hidden treasures.

In winter, the beaver is huddled deep within its lodge, keeping its family close.

As the days shorten and temperatures fall, badgers retreat deeper into their setts, entering a state of torpor as their metabolism slows and they become less active. Fallen fruit, nuts and berries combined with insects, worms and carrion all provide a badger with enough body fats to go to sleep for weeks at a time and not need to worry about waking up to

not need to worry about waking up to

Lizzie Laybourne, Nature-Based Solutions Officer at The Trust, said: “The warming climate is changing breeding cycles, food availability, and even behaviours like hibernation. Mild winters can cause some species to emerge from hibernation earlier, which is a problem if there isn’t enough food available yet to replace the energy they’ve used. We have seen these changes in hedgehogs, and other species such as bats and dormice, but we need to do more research to better understand the impacts on these and all hibernating species.”

● Learn more about hibernation patterns: wildlifetrusts.org/blog/ guest/hibernation-wildlifeswinter-survival-strategy

In autumn they fatten up, foraging less as the season advances. Their bodies have some special adaptations for winter – glands that secrete oils to help waterproof their fur, keeping it sleek against icy

rivers, and extra fat stored in their tails which they use for an energy boost as their winter stores deplete. The frozen waters do little to halt their cycle of life – it is courtship time in January and February, with the promise of new kits in springtime.

Along the Itchen and Test, otter slip between worlds — rivers and land, flood and frost. Hidden holts beneath tree roots and burrows offer rest, though swollen waters may force them to move between multiple holts. Their sleek coats and insulating underfur keep them at ease in ice-edged currents, hunting fish with ease where salmon redds mark the

riverbed. In the stillness of winter, their prints on frosty banks tell of a life as vigorous as ever.

On short days and long nights, the barn owl sometimes hunts in daylight, quartering meadows in search of voles and shrew. These small mammals become less active in winter, making them even harder to detect and catch. Barn owls will often hunt from perches rather than flying, to conserve energy and they seek sheltered draft-free nesting spaces to keep warm.

Many birds vanish southward, opening space for hardy visitors from colder lands. Flocks of redwing and fieldfare descend on berry-laden hedgerows, their chatter carrying on cold winds. Others remain, conserving energy with careful foraging, every fat-rich seed and berry a lifeline until spring.

In the still air of winter evenings herald moths, December moths and the aptly named winter moths flutter

Each autumn and winter Atlantic salmon will embark on an epic journey up Hampshire’s rivers. Guided by scent and temperature, they return to spawn in the very waters in which they were born. It’s an extraordinary yet challenging part of their life cycle: battling against the current, scaling obstacles and evading predators. When they reach their destination, females dig grooves in the riverbed called redds (see page 26 for more on habitats), she lays eggs inside and

males fertilise them. It’s common for both parents to die afterwards, making it vital that the next generation survives to return to sea.

Spawning salmon need clean, cold, oxygen-rich water with stable flows, plenty of streamside vegetation, and gravelly riverbeds - conditions that are globally rare but can be found in our chalk streams. In the headwaters of the River Itchen however, Atlantic salmon face mounting threats. Habitat destruction, pollution, climate change,

through the darkness, fragile proof that life does not wait for warmth. In fact, the December moth has evolved some fascinating traits to keep it flying even on the coldest of nights. They have alcohols in their blood acting as an antifreeze, they can vibrate to warm themselves up and purge water to stop them freezing. Flying in winter also has some perks – as night flyers the December moth has longer to fly under the cover of darkness therefore avoiding being picked off by hibernating bats.

Meanwhile, unseen beneath the frozen mirror of ponds and streams, water boatmen row tirelessly, dragonfly nymphs lurk, and even some mayflies time their hatching for the brief warmth of midwinter thaws.

Winter may seem a season of absence, yet it is also a time of endurance. These winter warriors remind us that life is never truly stilled, only reshaped, holding fast until the turning of the year brings warmth and abundance once more.

and human-made barriers all impair salmon’s ability to complete their life cycle.

1. Leave berries on shrubs and hedgerows

Holly, hawthorn, and rowan berries are vital for thrushes, blackbirds, and fieldfares. These natural winter foods provide sugars and nutrients birds need to survive long, cold nights.

2. Keep bird feeders clean

Washing feeders and birdbaths regularly prevents the spread of diseases such as salmonella and trichomonosis, which can decimate local bird populations in winter.

4. Plant wildlife-friendly shrubs

Evergreens and native plants provide winter shelter and berries for birds and insects. Species such as holly, ivy, and hawthorn support multiple animals, from pollinators to small mammals.

3. Avoid disturbing hibernating animals

Hedgehogs, bats, and amphibians hibernate to conserve energy. Disturbing them forces them to use precious fat reserves, reducing survival chances until spring.

5. Leave some seed heads and stems

Teasel (pictured), thistle, and sunflower heads offer food for birds such as goldfinches and seed-eating insects. Tall stems can also act as perches and shelter during frost. Insects will over winter inside hollow stems therefore it’s advisable to leave any cutting back of dead stems until the temperature in spring is consistently above 10 degrees or so.

Badgers are master excavators, digging extensive tunnel systems known as setts in well-drained soils. These setts (or badger’s dens) are passed down through generations, offering warmth and safety during the winter months. Although not true hibernators, badgers slow down, sleeping for days at a time and emerging only on milder nights to forage.

As winter tightens its grip on Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, mammals respond in quiet but remarkable ways – seeking places to rest, hibernate, or weather the cold. From the upland chalk of the South Downs to the wetland edges of the Test and Avon, each species has its winter strategy, shaped by the habitat it calls home.

Hampshire’s iconic chalk streams, like the Test and Itchen, are vital winter habitats for Atlantic salmon. In late autumn and early winter, females dig gravel nests called redds to lay their eggs. These remain buried in the streambed throughout the winter, hatching in early spring – so long as the water stays clean, cold, and free.

In sandy soils, rabbits occupy complex underground warrens. These burrow systems provide shelter from predators such as foxes and stoats as well as the worst of the weather. Winter is a time of caution: with food scarcer, rabbits venture out less frequently, often feeding at dusk and dawn to avoid detection.

Sunken lanes and overgrown hedgerows, known locally as holloways, offer excellent hibernation sites for hedgehogs. In autumn, hedgehogs begin to collect dry leaves, grass, bracken, reeds and use these materials for building nests called hibernacula at the bottom of hedgerows, fallen logs or piles of brushwood. These nests prove to be surprisingly waterproof and good insulation against the cold in winter. Wildlife-friendly gardens and connected green corridors are key to supporting these vulnerable creatures through the cold months.

Few mammals are more finely attuned to the seasons than the hazel dormouse. This elusive, golden-furred rodent is almost entirely absent from our winter countryside – not because it has migrated or vanished, but because it is fast asleep, its tail wrapped around itself for warmth, hidden beneath the leaf litter of ancient woods and tangled hedgerows. Tucked away at ground level, they build a nest ball of tightly woven vegetation to keep themselves cosy. Woodland edges, coppiced hazel stands, and thick, scrubby undergrowth often provide the right conditions, where temperatures stay more constant.

Beavers are once again shaping our waterways in the UK. The Trust is excited to bring closer the potential of a wild release and is currently working towards the licence approval before next steps can be taken to release them into the Eastern Yar river on the Isle of Wight. Beavers build lodges or dig bank-side holts to survive the colder months. These structures, insulated with mud and branches, provide a warm refuge and play a vital role in slowing winter floodwaters, improving wetland resilience for other wildlife too.

Britain’s fastest-declining mammal, the water vole, digs burrows into the soft banks of the river and its tributaries that flow along the edges. In winter, they retreat to dry, grass-lined chambers and feed on stored vegetation. Habitat loss and predation by invasive American mink have made safe holts increasingly rare –though conservation efforts are beginning to reverse this trend.

In the wooded copses and scrub-fringed fields of Hampshire, red foxes retreat to burrow systems known as ‘earths’ during the colder months. These underground shelters – often repurposed from rabbit warrens or badger setts – provide a safe, dry refuge for resting or raising cubs. They scent-mark their territorial borders with urine, creating a strong, recognisable odour. When the cold bites hardest, foxes rest up in the earth, curled tightly to conserve warmth.

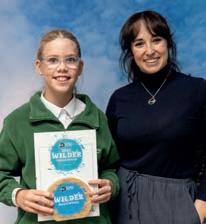

The Trust transformed Eastleigh’s Point Theatre into a vibrant hub of ideas and celebration for this year’s Wilder Conference & Awards 2025 — bringing together experts, communities, and local nature champions, all united in accelerating action for wildlife.

The day began with the launch of our refreshed Wilder 2030 strategy, building on the bold ambitions first set out in 2020. The updated plan is a fresh call to drive ambitious, landscape-wide change, placing nature at the centre of every decision. You can read more about it at hiwwt.org.uk/our-strategy

Two lively panel sessions followed, featuring national and local voices from conservation, farming, business, and community action. Among the speakers were Craig Bennett, CEO of The Wildlife

Trusts; Liz Bonnin, Broadcaster; Sue Pritchard, CEO of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission; Siôn McGeever, CEO of the South Downs National Park; and Julia Davies, Impact Investor.

The first panel looked at the bigger picture – how policies, investment and leadership can make doing right by nature the norm, not the exception.

The second panel, featuring Megan McCubbin; Cllr Kate Tuck; Nick Smith, Retail and Hospitality Director, Southern Co-op; Theo Vickers, Underwater Photographer; and Barnes Edwards, Garlic Farm, brought the conversation closer to home, exploring how choices made on farms, coastlines, in businesses and communities can build momentum for change. Watch highlights at hiwwt.org.uk/wilder-conference

“ ere are absolute gems of humanity across Hampshire and the

Isle of Wight – people who go above and beyond for the natural world. eir passion inspires us all, and their value cannot be underestimated.”

Trust

Megan McCubbin presented 16 awards celebrating schools, businesses, landowners, volunteers, and young leaders who are all driving action for nature across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.

Wicor Primary School, Portchester

Wicor Primary received the Wilder School Award for weaving nature into everyday learning. From gardening and recycling to selling produce at their student-run ‘Thrug’ shop, pupils develop real-world skills and a deep connection with the environment, even taking their care for nature into the community through local litter picks and planting 30 new trees.

Brian Matthews and Linda Seekings

Brian Matthews (right) has given 16 years of service as a New Forest conservation volunteer, tackling invasive species and supporting river restoration. Linda Seekings, an education volunteer at Testwood Lakes, has inspired thousands through Forest School sessions and mentoring new volunteers. Their dedication embodies the spirit of the Trust.

Southern Co-op, Portsmouth

Southern Co-op was honoured for long-term leadership in sustainability and biodiversity. The business donated £100,000 to help support the Trust with its purchase of two key nature sites, safeguarding habitats for wildlife and showing how local companies can make a lasting environmental impact.

Emily, Kings Worthy Primary

Ten-yearold Emily impressed judges with her eco-leadership, introducing recycling for soft plastics, leading litter picks, and improving school grounds for wildlife. She also raises awareness and funds for Surfers Against Sewage – a true young force for nature.

Nature Restoration Project Award Biddenfield and South Holt, South Downs

Here, landowner Harvey Jones has transformed woodland, pasture and farmland to support a remarkable diversity of wildlife.

Ewhurst Park, Tadley

Once a shooting estate, Ewhurst Park is being transformed into 374 hectares (925 acres) of grassland, wetland and woodland. The community-led restoration creates vital habitats and reconnects people with a recovering landscape rich in wildlife.

River Meon Conservation Volunteers

This group of volunteers (above) have positively impacted our rivers through outreach work, habitat restoration and invasive species removal.

Additional winners:

• Food and Farming with Nature Award The Garlic Farm, Isle of Wight

• Nature Restoration Project Award

Lower Anton Westfair Project, Andover (pictured on page 3)

• Individual Action for Nature Award Adrian Smith, Bishop’s Waltham

Highly commended:

• Wilder School Award

Medstead C of E Primary School, Alton

• Food and Farming with Nature Award

Warren Farm, Totland

• Collective Action for Nature Award

Friends of Portswood Recreation Ground, Southampton

• Young Changemaker Award Ben and Nye, Brockenhurst; Portsmouth Youth Cabinet

For more details about our nature champions, visit: hiwwt.org.uk/ wilder-conference

Among the beautiful chalk downland at St Catherine’s Hill, Community Ecologist (and college lecturer) Susan Simmonds explains how, nearly 30 years ago, she was steered towards working in nature and has never looked back.

I’ve been with the Trust since 2000, working across engagement and education. I now run adult training courses on wildflowers, mammal tracks, water vole and river fly surveys, with attendees ranging from students and professionals to local nature enthusiasts. It’s the perfect mix of people and wildlife. I’m also a lecturer at Sparsholt College in Winchester.

Popular courses have included water vole surveying for environmental professionals wanting to monitor populations along watercourses Wildflower identification training has also been hugely in demand: I’ve recently been working with Vitacress (salad growers), training their staff to identify wildflowers and insects on their land and teaching them how to encourage more wildlife in.

My earliest memory of wildlife in Hampshire is when we moved to my second childhood home in Andover, when I was eight or nine. Our house backed onto some chalk downland and I’d sit in the field with a little butterfly book, trying to work out which blue species I’d seen. My granddad regularly took us down to the river to fish for minnows and sticklebacks.

My interest in the environment really took off when I began studying Environmental Science at Plymouth University. I started by studying languages at Keele and realised it wasn’t for me, so I switched. A brilliant decision, as wildlife is what I truly love.

At the time, I don’t remember hearing much about biodiversity loss. News reports focussed more on fossil fuels and the ozone layer. It only hit home after my degree when I started volunteering and conducting surveys, and people said things like, “Did you know, we’ve lost 97% of our wildflower meadows?”

My conservation career began after recovering from a difficult period in my early twenties. One day, I spotted a butterfly in my mum’s garden. I remember getting up and going over to see what it was. It was a real turning point as I knew I was getting better. Soon after, I volunteered with the Trust monitoring butterflies at a local nature reserve. I continued volunteering, taking on more work until I felt fully recovered. The Trust then began employing me in small temporary positions, and that was nearly

30 years ago. I feel extremely grateful still to be doing the work that I love after all these years.

One special memory for me is of a child described by his teacher as ‘really naughty,’ who became completely focussed, engaged and alive with enthusiasm when outside exploring nature. Another time, a Polish child who spoke no English became fully involved in a wildlife activity. The teacher commented that it was the first time she had seen him completely engaged in any activity. Those moments stay with you. Other highlights include filming in the river with John Craven for Countryfile in 2019. But the best moments are always when a group I’m with sees something rare and exciting. I love being able to open people’s eyes to the wonders of nature that is so often on their doorstep.

During lockdown, I started making short Bringing Nature to You videos for the Trust’s Facebook page It was exciting to think of all the people watching, and the chance to influence them in a positive way during such a difficult time for everyone.

Recently, I presented a feature on insect decline with ITV Meridian. I know some people don’t enjoy being on camera, but I’m so passionate about the subject which somehow overrides any nerves. Also, life is short: sometimes you need to go for it!

It might sound corny, but the Trust is a part of me now. Even when I’m not working, I’m walking somewhere looking for butterflies, wild orchids or something new.

Visit St Catherine’s Hill Nature Reserve, Garnier Road, Winchester, SO23 9PA or what3words: mental/thumbnail/clenching

Visit hiwwt.org.uk/events to see our upcoming courses, walks and talks. We’re currently planning our 2026 spring/summer schedule, which will be added to the website early in the new year. Bespoke courses on environmental topics can also be arranged — contact wilder@hiwwt. org.uk for details.

Treat the nature lover in your life with the gi of membership to Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust and help protect the wildlife and wild places that mean the most to you.

Recipients will receive:

● An exciting welcome pack

● Three issues of Wild Life magazine per year

● Wildlife and Wild Places Nature Reserve Guide

● Wildflower seeds

Family members also receive junior membership, including a pack to open for Christmas, with stickers, poster, and a wildlife handbook. Plus, four Wildlife Watch magazines per year!

Membership starts from just £27 per year. Contact our membership team today on 01489 774408, visit hiwwt.org.uk/shop or scan the QR code.