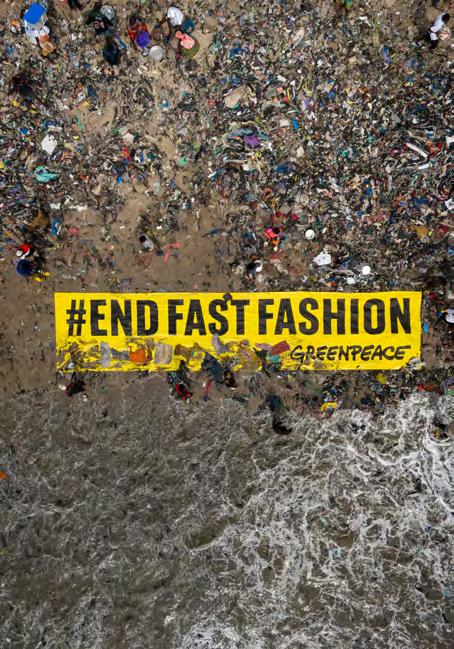

A new Greenpeace investigation reveals that Shein’s chemical management is failing — hazardous substances are still turning up in fast fashion goods

Shein embodies the acceleration of fast fashion. The company tracks trends in real time, copies designs using AI and pushes production through a dense network of Chinese suppliers working under extreme pressure. The result: thousands of new designs every day — on peak days more than 10,000 — many available for only a few weeks. With 363 million monthly visits, Shein.com is now the world’s most visited fashion website — attracting more traffic than Nike, Myntra and H&M combined. At any given time, the platform carries over half a million styles — twenty times H&M’s range. Aggressive marketing, “dark patterns” in its app and a huge presence on TikTok and Instagram create a buying frenzy among their mainly young consumers. Prices are artificially low; the real costs are paid through environmental destruction and human exploitation. Polyester accounts for 82 % of fibres used — in other words: fossil fuel — and the company’s emissions have quadrupled in the last three years. Shein exploits customs loopholes and breaches consumer protection and environmental regulations — despite repeated multimillion-euro fines. The

Greenpeace purchased a total of 56 garments and shoes from Shein across eight countries and had them analyzed for hazardous chemicals.

company's practices show where an unrestrained economic system leads — and it is pulling the entire industry along in its wake. Fast fashion means overproduction, exploitation and a reckless transgression of planetary boundaries.

In 2022, Greenpeace found hazardous chemicals above EU regulatory limits (REACH) in 7 of 47 Shein products tested. Since then, Shein’s platform has surged in popularity: the company continued to grow rapidly, with revenue up from $23 billion (2022) to $38 billion (2024) – making it the biggest online fashion store worldwide. In the meantime, Shein acknowledged the chemical contamination and pledged substantial improvements to its chemical management.

To verify whether those promises hold, Greenpeace re-tested Shein products in 2025.

Greenpeace purchased 56 garments and shoes from Shein across eight countries and had them analysed for hazardous chemicals at an independent, accredited laboratory in Germany. The results are alarming:

> 18 of 56 products (32 %) exceeded EU REACH limits; including children's clothing (3 items)

> 7 products (jackets) exceeded PFAS limits by up to 3,300 times.

> 14 products exceeded phthalates limits, 6 by 100 times or more.

Even a single jacket or pair of shoes can pose risks: many items contained chemicals that are persistent and bioaccumulative, polluting rivers, lakes, seas and threatening the life within them. Particularly concerning are persistent, hormone-disrupting substances such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) — used to make jackets water and stain-repellent — and phthalates, used as plasticisers in footwear. Workers in producing countries are likely to be exposed without protection, while chemicals are discharged into waterways and soils. Consumers are also at risk as they can be exposed to these

chemicals in several ways — directly through the skin (e.g. when sweating), by inhaling textile fibres in the air, and in the case of babies and small children through mouthing contaminated clothes – hazardous chemicals in textiles can also enter the environment during washing or disposal, eventually reaching rivers and the food chain.

The substances detected above legal limits include:

PHTHALATES (in 14 products): linked to impaired growth, fertility and child development; also toxic to aquatic life, with long-term biodiversity impacts.

PER- AND POLYFLUOROALKYL SUBSTANCES (PFAS) (in 7 products): extremely persistent in the environment, PFAS can accumulate over time reaching acutely toxic concentrations. Some of these substances can also build up in the human body and are suspected of being carcinogenic. They can impair fertility and child development, weaken the immune system, and disrupt liver and kidney function. PFAS exposure may also increase the risk of thyroid and metabolic disorders. Highly mobile in the environment, these “forever chemicals” contaminate groundwater, rivers, oceans and even remote regions.

HEAVY METALS (LEAD & CADMIUM)

(in 2 products): lead (Pb) is particularly harmful to children (affecting brain development, IQ, learning and behaviour) and damages the nervous system, kidneys and reproductive organs and can affect hormonal balance. Cadmium (Cd) is a probable carcinogen that can harm kidneys, lungs, liver, the cardiovascular and nervous systems, as well as negatively affect fertility and birthweight. Both are toxic to aquatic organisms and bioaccumulate in the food chain, affect organs, disrupt physiological and hormonal functions and impair growth and reproduction.

ALKYLPHENOL ETHOXYLATES (APEO) (in 1 product): break down in the environment to hazardous compounds such as nonylphenol and octylphenol, which are highly persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They disrupt the

hormonal systems of aquatic organisms, cause feminisation in male fish, alter sex ratios and impair reproduction.

FORMALDEHYDE (in 1 product): can cause DNA damage that may lead to cancer and genetic disorders. Also irritating to the skin, eyes and respiratory tract.

In early 2025, Shein again claimed major improvements in its chemical management — including (i) publishing a Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (MRSL), (ii) expanding internal testing and (iii) excluding non-compliant suppliers. Our results suggest these measures are not effective. Shein products still contain hazardous chemicals above EU limits. Greenpeace identifies a pattern: some items flagged in earlier tests reappear in near-identical form — with the same hazardous substances. Shein removes individual items once exposed, only to replace some of them with near clones — possibly even from the same supplier. Given the extreme product range and vast supplier base, Shein appears unable to control the chemicals used in products sold on its platform.

At the same time, Shein seems to exploit loopholes in EU chemicals legislation. Because sellers on the platform ship directly to consumers within the EU, Shein can circumvent the REACH obligations — putting profit before people and the planet. As a result, Shein and similar platforms can continue to place non-compliant products on the European market without facing meaningful legal consequences. Our latest investigation exposes, once more, how voluntary self-regulation and inadequate enforcement fails to protect people and the environment.

Fast fashion is a systemic problem. There is already more than enough clothing in the world to dress everyone. Yet the industry continues to flood markets with volumes far beyond global needs. To make sure these clothes are still sold, the sector deliberately fuels consumer frenzy through social media, influencer marketing and advertising. Fast fashion thrives on exploitation and appalling working conditions — producing garments designed for the bin. Every second, a truckload of clothing ends up in landfill or incineration somewhere in the world.

To stop this destructive cycle, governments worldwide must introduce a comprehensive Anti-Fast-Fashion Law.

More concretely:

• A fast-fashion levy, to make producers finally pay for the damage caused by their excessive production.

• A ban on fast-fashion advertising, including on social media, to cool down today’s artificially overheated consumption climate.

• Support truly circular business models, such as second-hand, swapping and repair schemes.

France has already taken an important first step with its anti-fast-fashion law. Other countries must now follow suit — to create a truly circular textile economy with less waste, longer-lasting, higher-quality clothing, and a vibrant culture of repair and reuse.

EU regulation must urgently be updated so that online platforms like Shein and Temu can no longer bypass existing law.

Greenpeace specifically calls for:

• applying EU chemicals legislation to all products sold within the EU, including those offered by online platforms,

• making platforms legally liable under EU law for any breaches,

• allowing authorities to suspend platforms in cases of repeated violations.

Only binding, enforceable regulation can prevent hazardous chemicals from entering the EU unchecked — and protect the health of consumers and ecosystems worldwide.

Fast fashion come with a cheap price tag, but the real bill is footed by the environment, workers and future generations. The ever-growing piles of discarded clothing reflect extreme resource use, severe pollution, microplastic contamination and exploitative working conditions. The harm is not only systemic; it is also present in the garments themselves. The clothes can contain hazardous chemicals that are linked to cancer, hormonal and immune system disruption, allergic reactions, as well as toxic effects on fish, plants and other organisms in rivers, lakes and seas. People in producing countries are particularly affected, as these substances are often used and disposed of with little or no oversight, contaminating waterways and soils [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

In 2022, Greenpeace [6] tested clothing from the online retailer Shein for hazardous substances for the first time. The results were alarming: seven of 47 products exceeded regulatory limits under the EU’s REACH regulation. Since then, Shein’s growth — and the scale of the problem — have surged. Revenue rose from US$23 billion (2022) to US$38 billion (2024) [7], [8]. Platforms such as Shein and Temu have become fixtures in e-commerce: in 2024, Shein was the biggest online fashion store worldwide [9]. That same year, an estimated 4.6 billion small parcels entered the EU below the customs de minimis threshold — 90 % originating from China [10]

Shein pushes the fast-fashion model to the limit: thousands of new designs each day, many directly copied or plagiarised — produced at the lowest possible cost and promoted via aggressive, misleading social-media marketing [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. The clothes are made almost entirely from synthetic fibres, which are cheaper and quicker to process than cotton [16]. The use of hazardous chemicals is not an aberration but a deliberate feature of the business model: they are cheaper than safer alternatives and enable rapid, high-volume production [6]

In response to criticism over hazardous chemicals in its products, Shein introduced a Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (MRSL) in 2024.

Additionally in early 2025, Shein again claimed improvements to its chemicals management — citing more than two million product tests in 2024 and the exclusion of 260 suppliers for non-compliance [17].

Do these promises stand up to independent scrutiny?

Greenpeace repeated its 2022 tests, purchasing a total of 56 Shein products in eight countries and having them analysed by an independent laboratory. The findings are alarming: hazardous chemicals exceeding EU limits were detected in 18 items – 32 % of the total – in some cases at extremely high concentrations. Our conclusion is clear: Shein’s measures are having no measurable effect.

The findings leave no doubt: voluntary pledges are nowhere near enough to protect people and the planet. Political action is overdue. The EU must close the regulatory loophole that allows online platforms such as Shein and Temu to sell non-compliant products in the EU without consequences. Beyond that, an Anti-Fast-Fashion Law is needed — introducing a fast-fashion levy, a ban on advertising, and targeted support for circular alternatives such as renting, swapping and repairing — to rein in the fastfashion system.

This report shows that fast fashion is not just a matter of overconsumption — it is a structural threat to both the environment and human health. And it explains why the system itself must change — urgently.

Between May and June 2025, we purchased a total of 56 Shein items - such as shoes, dresses, outerwear and pyjamas for adults, and including 17 items for children (Annex I). These products were tested for hazardous chemicals regulated under EU law. The items were bought through Shein’s online shops in Austria (5), Germany (24), Israel (5), Portugal (4), Spain (4), Sweden (3), Switzerland (4) and Thailand (5), as well as directly from a Shein pop-up store in Frankfurt, Germany (2), and sent to a certified, independent laboratory in Germany for analysis.

In the laboratory, each item first underwent a series of preliminary screenings — including Beilstein tests, odour assessments and water and oil-repellency checks — to determine which substances to analyse in each case. Particular attention was paid to hazardous chemicals commonly used in textiles such as detergents, coatings, dyes, antimicrobial agents, solvents, flame retardants and plasticisers. Based on the results of these initial tests and the composition of the materials, samples were taken from parts of the products and analysed for a range of substances. These included phthalates, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), heavy metals, formaldehyde, alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEO — ethoxylated nonylphenols and octylphenols), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), aromatic amines, quinoline, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), organotin compounds and brominated flame retardants. All analyses were conducted in line with established standard procedures (Annex II). Comprehensive details on the textile items, the respective samples, the chemicals tested and the analytical methods are provided in the laboratory’s test report (Annex III, available online).

In total, 11 hazardous substances from five chemical groups were detected in 18 of the 56 products tested (32 %) at concentrations exceeding EU REACH limits [18]. These chemicals pose risks to both human health and the environment as they are toxic and hardly degradable in the environment. They can destroy ecosystems and endanger

biodiversity. Additionally, they can cause cancer, disrupt the immune system, and trigger skin or eye allergies.

Humans are exposed to these chemicals from textiles in various ways. The most common route is through the skin, particularly when sweating, as this facilitates the release of these substances. Inhaling tiny textile fibres also plays a role. In infants and young children, sucking on fabrics can also lead to exposure. Ultimately, chemicals enter the environment via wastewater or textile disposal, where they can reach rivers, soil and, via the food chain, animals.

The most frequently detected substances found above regulatory limits were phthalates, used as plasticisers in synthetic materials. Excessive concentrations of phthalates were identified in 14 products. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), particularly the fluorotelomers, exceeded EU limits in seven products — all of them water-repellent outdoor jackets. Heavy metals, specifically lead and cadmium, as well as formaldehyde, nonylphenol and dimethylformamide (DMF), each exceeded REACH thresholds in one product. The levels of hazardous substances detected above REACH limits ranged from 1.1 to as much as 3,269 times the permitted concentrations. The highest exceedances were found for PFAS (up to 3,269 times) and for phthalates (up to 200 times).

In addition to the substances exceeding REACH limits, measurable amounts of hazardous chemicals below those limits were also found in the tested products. The analysis further identified other potentially harmful substances not currently regulated under REACH. A summary of the overall findings is provided below. Detailed results for each product are listed in Annex I, and the full laboratory data for all samples can be found in the complete test report.

Phthalate: plasticiser to increase flexibility and softness [19].

28 samples from 24 products were tested. All samples contained between one and four phthalates, at concentrations ranging from 100 to 340,000 mg / kg. The levels measured in 15 samples from 14 products exceeded the REACH limit by up to 200 times. Phthalates can be toxic to both humans and the environment. They can disrupt the hormonal

One-third of the products tested contain hazardous chemicals above the EU regulatory limits (REACH).

system and impair growth, fertility and the healthy development of children. Similar toxic effects have been observed in aquatic organisms, with long-term repercussions for biodiversity [20]

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): used in textiles — particularly outdoor products — to make them repellent to water, oil and dirt [21]. 9 samples from 9 products were tested for PFAS. Seven samples — all from water-repellent outdoor jackets — contained between two and four PFAS compounds, all of them fluorotelomers (4:2, 6:2, 8:2, 10:2 FTOH), at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 650 mg / kg. In all 7 products, PFAS levels exceeded the REACH limit by between 1.8 and 3,269 times. PFAS are extremely persistent in the environment — they barely break down and can accumulate over time to reach acutely toxic concentrations. They are highly mobile, spreading widely and contaminating groundwater, rivers and oceans — even in remote regions such as the Arctic [22]. Some PFAS accumulate in the human body and are suspected of being carcinogenic. They can also disrupt the hormonal system — affecting fertility and the healthy development of children — as well as the immune

system, increasing susceptibility to infections. In addition, PFAS can impair liver and kidney function and raise the risk of thyroid and metabolic disorders [20]

Heavy metals (lead, cadmium, nickel and antimony): components of dyes and fixing agents used to enhance colour fastness [23]. 62 samples from 53 products were subjected to various metal analyses (lead, cadmium, nickel and antimony) depending on their composition and product type.

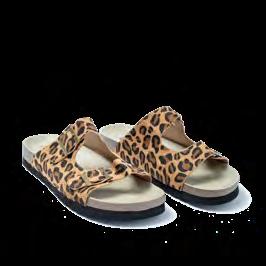

• Lead (Pb): Pb was detected in three products at concentrations of 103, 156 and 2,670 mg / kg. The highest level — 2,670 mg / kg, or 2.67 times the REACH limit — was found in the insole of a pair of sandals (FT-50).

Lead is highly dangerous to children — it can impair brain development, lower IQ, and affect learning and behaviour. It may also cause anaemia, growth delays and kidney damage. In addition, lead can disrupt the body’s hormonal balance, interfering with the normal function of the thyroid, adrenal and reproductive systems.

• Cadmium (Cd): Cd was detected in 3 samples at concentrations of 2, 24 and 120 mg / kg. The concentration of 120 mg / kg — found in the sole of a women’s shoe (FT-36) — exceeds the REACH limit of 100 mg / kg. Cadmium is carcinogenic and can damage vital organs including the kidneys, lungs, liver, nervous and cardiovascular systems, as well as bones. It can also reduce fertility and lower birthweight.

• Nickel (Ni): Nickel was detected in the metal components of a children’s swimsuit at a concentration of 42,000 mg / kg. There is no REACH regulation for nickel content in textiles; instead, REACH sets a limit for the rate of nickel release from textile materials. Only one product — a motorcycle jacket (FT-44) — showed a measurable nickel release rate of 0.2 μg / m²/week, which is below the REACH threshold. Nickel is suspected of being carcinogenic and can cause skin allergies as well as respiratory damage.

• Antimony (Sb): Extractable antimony was detected in 21 products at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 55 mg / kg — indicating the potential for release through perspiration. The REACH limit for certain extractable metals in textile products is 1 mg / kg,

but no specific threshold currently exists for antimony. Antimony (Sb) can cause skin and eye irritation and may damage the respiratory system, liver and kidneys.

Beyond their risks to human health, these heavy metals are also toxic to aquatic organisms. They accumulate in the food chain, damage vital organs, disrupt physiological and hormonal functions, and impair growth and reproduction [20].

Formaldehyde: used as a finishing agent to make textiles wrinkle-free and dimensionally stable during production [24] 20 samples from 20 products were tested for formaldehyde. 6 contained the substance at levels ranging from 6 to 260 mg / kg. The highest concentration — 260 mg / kg, or 3.5 times the REACH limit — was found in a children’s costume (FT-27). Formaldehyde can damage DNA, leading to cancer and hereditary disorders. It can also cause irritation of the skin, eyes and respiratory system [20]

Children‘s clothing also exceeds REACH limits.

Alkylphenol ethoxylates (APEOs): nonylphenol ethoxylate and octylphenol ethoxylate): used as detergents and wetting agents in textile processing [25].

24 samples from 24 products were tested for APEOs. Only nonylphenol ethoxylate was detected — in a raincoat (FT-49) — at a concentration of 130 mg / kg, exceeding the REACH limit of 100 mg / kg.

Alkylphenol ethoxylates such as nonylphenol ethoxylate and octylphenol ethoxylate degrade in the environment into persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic compounds, including nonylphenol and octylphenol. These substances can disrupt the hormonal systems of aquatic organisms — they can cause feminisaton in fish, hence altering sex ratios and interfering with reproduction. In humans, they can cause irritation to the skin and eyes [20]

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): not intentionally used in textile production, but may occur as contaminants originating from dyes, processing lubricants or synthetic materials [26]

7 samples from 7 products were tested for PAHs. All tested products contained between 1 and 18 PAH compounds, with concentrations ranging from the detection limit (0.1 mg / kg) to 48 mg / kg.

PAHs are carcinogenic compounds that can damage DNA, potentially leading to cancer, genetic disorders and developmental abnormalities. They can harm the lungs, liver and heart, persist in the environment, and accumulate in plants, animals and throughout the food chain. PAHs are also toxic to aquatic organisms, causing DNA damage, genetic mutations and disruptions to reproduction and growth [20].

Aromatic amines: by-products of azo dyes, which are used to produce bright, long-lasting colours in textiles [27]

7 samples from 7 products were tested for aromatic amines. 3 products showed measurable levels of 2,4-toluenediamine (6 mg / kg), p-phenylenediamine (15 mg / kg) and aniline (53 mg / kg). The detected aromatic amines are not regulated under REACH. Some aromatic amines are persistent in the environment, bioaccumulative and toxic to aquatic organisms. They can cause reproductive and developmental disorders, behavioural changes and, in severe cases, death in aquatic species. In humans, they are suspected of causing genetic mutations, cancer and damage to the blood, liver, kidneys, skin and eyes [20].

Quinoline: a component of dyes and whitening agents in textiles [28].

24 samples from 24 products were tested for quinoline. 2 products showed concentrations of 3 and 6 mg / kg — both below the REACH limit of 50 mg / kg.

Quinoline can cause skin and eye irritation and is suspected of causing genetic damage and cancer. It is highly toxic to aquatic organisms and can cause acute mortality as well as reproductive and developmental disorders [20].

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs): derived from solvents used in dyes, coatings and finishing agents during textile production [29]

20 samples from 19 products were tested for VOCs. Various VOCs were detected in all samples, with at least one identified in each product.

Dimethylformamide (DMF) was found in 15 samples at concentrations ranging from 13–1,100 mg / kg, and formamide in 4 samples at 38–420 mg / kg. While most measured levels were below REACH limits, the DMF concentration of 1,100 mg / kg exceeds the threshold of 1,000 mg / kg for Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC).

DMF and formamide can harm the unborn child and cause irritation to the skin, eyes and respiratory tract. Most other detected volatile organic compounds can cause similar health effects; long-term exposure may lead to organ damage and, in some cases, cancer [20].

After Greenpeace published the 2022 test results, Shein removed all products found to exceed REACH limits from its platform. At the same time, the company insisted it takes product safety very seriously, claiming that all suppliers are required to follow standards — including chemical control lists and regulations aligned with REACH — and that it works closely with independent international testing bodies such as TÜV (Technical Inspection Association, Germany), SGS (Société Générale de Surveillance, Switzerland) and BV (Bureau Veritas, France) to carry out regular products safety checks [30]. Shein gave a similar response following other investigations — including one by the German consumer magazine ÖKO-TEST in August 2024 [31].

Shein has since responded to repeated findings of hazardous chemicals in its products (e. g. [31], [32], [33]). In 2024, the company published a Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (MRSL) setting out the regulated chemicals that its suppliers must comply with. In early 2025, Shein again claimed to have strengthened its chemicals management system — stating that in 2024 it had carried out more than two million product tests and terminated contracts with 260 suppliers for non-compliance. The company announced plans to invest over US$15 million in 2025 to further enhance its product safety testing and documentation systems [17].

Our findings, however, show no sign of any real progress in Shein’s chemical management. Many of the products tested still exceed EU limits — items that should not be available on the European market at all. Shein’s voluntary pledges clearly fall short of protecting people and the planet from hazardous chemicals.

As in our previous investigations, the most common non-compliance involved the plasticiser phthalate — an endocrine disruptor — found in 25 % of the products, mainly in footwear, as in 2022. Unlike the earlier tests, this year’s analysis also included jackets.

PFAS are widely used in such garments to make them water and stain-repellent. We detected these so-called “forever chemicals” in 12 % of the products. The highest recorded level — fluorotelomer alcohols in a women’s outdoor jacket (FT-43) — exceeded EU limits by up to 3,300 times.

Moreover, similar products examined in this study, in Greenpeace’s 2022 report, and in other investigations into chemicals in Shein products ([31], [32], [33]) revealed the same types of hazardous substances at comparable concentrations. In our 2022 tests, a children’s costume exceeded REACH limits for formaldehyde — a carcinogenic and mutagenic chemical known to damage DNA, promote cancer and genetic disorders, and interfere with development and reproduction [20], [34]. In the current tests, a very similar costume once again exceeded formaldehyde limits. In a pair of women’s sandals, we found lead (Pb) and phthalates above the regulatory thresholds — as ÖKO-TEST [31] did with a comparable model in 2024.

Shein may remove individual products from its platform once they are proven to breach EU limits, but these are often replaced with near-identical items containing the same hazardous chemicals — possibly even from the same supplier.

Given the sheer volume of products and suppliers, Shein appears to have little control over the chemicals contained in the items sold on its platform. The company is exploiting a loophole in the EU’s chemicals regulation: because sellers on the platform ship directly to consumers within the EU, Shein can circumvent the REACH obligations. The company knows it faces no real consequences for selling non-compliant products — putting profit before the safety of people and the planet.

Non-compliant products that were removed from the platform after previous tests (right: Ökotest Yearbook Children and Families 2025, left: Greenpeace Shein Report 2022 “Taking the shine of SHEIN”).

Strikingly similar Shein products from the latest Greenpeace 2025 test. Near-identical products again exceed REACH limits.

Launched in 2011, Greenpeace’s global Detox My Fashion campaign set out to eliminate hazardous chemicals from the textile industry. Despite decades of regulation and corporate responsibility programmes, our investigations at the time revealed dangerous substances in wastewater from textile factories, in finished products and in the environment around the world. Hundreds of thousands of supporters helped achieve what many thought impossible: worldwide more than 80 — including H&M, Zara and Adidas — committed to zero discharges of hazardous chemicals by eliminating their use in their supply chains and to disclosing data on toxic discharges from their factories. The campaign led to major progress in reducing environmental pollution from the textile industry. By 2021, many of these companies had significantly cut contamination in their supply chains and improved transparency around chemical releases in wastewater. Detox My Fashion also inspired key industry initiatives — including OEKO-TEX (an international certification system for textile safety), ZDHC (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals), the Detox Consortium in Italy (CID) and Bluesign — all working towards the same detox goal. The campaign also identified that the deeper and growing problems of overconsumption and overproduction driving the fashion industry were increasingly becoming a major barrier to implementing the Detox objective across the whole sector. [34], [35], [36].

Since 2000, global clothing production has more than tripled. Every year, an estimated 180 billion garments are produced worldwide [27], [28] — and 10–40 % of them are destroyed without ever being sold [39]. Yet each item is worn far less often. Between 2000 and 2015, the average number of times a garment was used before being discarded fell by 35 % [38]. Producing such vast quantities of clothing consumes immense amounts of water, energy and raw materials — resources our planet cannot provide indefinitely [40].

In Germany alone, an estimated 1.6 to 2 million tonnes of clothing end up as waste every year [41]. More than 60 % of collected textiles are exported abroad [41], where they often end up in rivers, on dumps or burned in open fires [2]. Worldwide, this creates more than 120 million tonnes of textile waste a year — a growing avalanche of fabric that cannot be recycled [42].

The global fashion industry is responsible for up to 8 % of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions [43] — more than all international flights and shipping combined [44]. Instead of offering solutions, fastfashion companies are accelerating the climate crisis with ever-shorter production and trend cycles.

More than two-thirds of all fibres used in textile production are now synthetic [45] — in other words, processed crude oil. Every wash of synthetic fabrics releases microplastics that end up in rivers, oceans and ultimately in our food. Fashion has thus become a major driver of global plastic pollution [46]

Millions of garment workers toil for poverty wages in unsafe factories, with little protection and few rights. The collapse of the Rana Plaza factory complex in 2013 — which killed more than 1,100 people — exposed the brutal reality of this system [47]. Even today, workers risk their health and lives every day so that T-shirts can be sold in Europe and the United States for just a few euros [48].

Fast fashion is wrecking the environment, fuelling the climate crisis and exploiting people without mercy — all for clothes that are often worn only a handful of times before ending up as waste.

Shein takes fast fashion to the extreme. The company’s model is driven by digital, real-time monitoring of trends, stolen and AI-generated designs, and a dense network of supplier factories in China operating under intense pressure [11], [49]. The result: thousands of new garments go online every day — more than 10,000 on peak days. On average, each item remains available for just over two months, while around 500,000 different styles are listed on the platform at any given time. For comparison, H&M offers around 25,000 [12].

With 363 million visits per month, Shein.com is the most-visited fashion website in the world — attracting more traffic than Nike, Myntra and H&M combined [50]. The app manipulates consumers through dark patterns: fake discounts, low-stock alerts and countdown timers designed to create artificial pressure to buy [14]. Shein maintains a powerful

With thousands of new designs every day and aggressive marketing, Shein is pulling the entire industry along in its wake.

presence on social media, particularly TikTok and Instagram, with Gen Z as its main target group. The company relies heavily on user-generated content and collaborates with thousands of influencers who promote Shein clothing and entice followers to shop using discount codes [13]. Combined with ultra-low prices achieved at the expense of people and the planet, these tactics deliberately manufacture demand — driving an ever-accelerating cycle of overconsumption.

But Shein is not only a consumption giant — it is also a lawbreaker. An investigation by the European Commission found that the company systematically violates EU consumer law, including through misleading discounts, coercive sales tactics, and missing or deceptive product information [15]. In July 2025, France fined Shein €40 million, followed by Italy in August 2025 with a further €1 million penalty — both for repeated consumer deception and unsubstantiated environmental claims [51]

The number of shipments from China has exploded: in 2024, 4.6 billion parcels were sent to the EU — the vast majority from Shein and Temu — equivalent

to 145 every second, 91 % of them originating in China. Shein and Temu systematically exploit the de minimis rule. Belgian authorities estimate that 65 % of all duty-free parcels are undervalued, meaning their actual worth exceeds the declared amount. In doing so, Shein and Temu evade customs duties and inspections — aided by the fact that customs authorities are simply unable to keep pace with the sheer volume of incoming parcels [10], [52].

82 % of the fibres used by Shein are polyester — in other words, processed fossil fuel [16]. The company’s greenhouse gas emissions quadrupled between 2021 and 2024 [16], [53]. Shein epitomises an industry that continues to ignore every warning while accelerating the destruction of our planet. Fast fashion is the very opposite of sustainability. Unless governments and companies act to stop this madness, the piles of discarded clothes will keep growing, the environment will continue to be polluted, and people will continue to be exploited and exposed to hazardous chemicals.

To put an end to the destructive fast-fashion system, clear legislation is needed — as this investigation and past experience [54] show, voluntary commitments are simply not enough. The EU and France have taken the first steps with three key regulatory initiatives.

The EU’s REACH chemicals regulation is a cornerstone of European environmental and consumer protection law. It requires companies to register, assess and replace hazardous substances in their products. For clothing, this means no carcinogenic dyes, no hormone-disrupting plasticisers, and no highly toxic “forever chemicals”. Greenpeace has long advocated for strong EU chemicals legislation because it holds manufacturers accountable. Yet one dangerous loophole remains: through online sales, platforms such as Shein can ship products directly from China to European consumers — without REACH verification and without customs checks. Legally, the responsibility lies with individual buyers. As a result, textiles that would otherwise be banned in the EU continue to enter the market. This loophole must be closed urgently by the EU.

France has become the first country in the world to adopt an Anti-Fast-Fashion Law [56]. It introduces a fast fashion levy of up to €5 per item — rising to €10 by 2030 — and a ban on advertising clothing that is particularly harmful to the environment or designed for short-term use. Originally intended to cover the entire fast fashion industry, the law was narrowed to ultra-fast-fashion platforms such as Shein, Temu and AliExpress following intense lobbying [55] Nevertheless, it marks a milestone: for the first time, a government is using legislation to curb the fast fashion business model — setting an example for others to follow.

On 16 October 2025, the revised EU Waste Framework Directive entered into force. For the first time, the EU has introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) obligations for textiles [57]. From April 2028, manufacturers will be responsible for their clothing products after disposal and must cover the costs of collection, sorting and recycling. These costs will be financed through fees paid by producers when placing textiles on the market, with contributions modulated to favour sustainable design. The precise criteria for this tiered system have yet to be defined. Member states are required to transpose the directive into national law by June 2027. The textiles EPR is an important first step towards funding the collection and management of textile waste — and, if properly implemented, could create incentives for more sustainable design. Yet it does not address the core problem of fast fashion: overconsumption. To truly end this cycle — and to hold those responsible for pollution, waste, the climate crisis and exploitation to account — much more is needed.

To stop this destructive cycle, governments worldwide must introduce a comprehensive Anti-Fast-Fashion Law. More concretely:

> A fast-fashion levy, to make producers finally pay for the damage caused by their excessive production.

> A ban on fast-fashion advertising , including on social media, to cool down today’s artificially overheated consumption climate.

> Support truly circular business models , such as second-hand, swapping and repair schemes.

France has already taken an important first step with its anti-fast-fashion law. Other countries must now follow suit — to create a truly circular textile economy with less waste, longer-lasting, higherquality clothing, and a vibrant culture of repair and reuse.

EU regulation must urgently be updated so that online platforms like Shein and Temu can no longer bypass existing law. Greenpeace specifically calls for:

> applying EU chemicals legislation to all products sold within the EU, including those offered by online platforms

> making platforms legally liable under EU law for any breaches,

> allowing authorities to suspend platforms in cases of repeated violations.

Only binding, enforceable regulation can prevent hazardous chemicals from entering the EU unchecked — and protect the health of consumers and ecosystems worldwide.

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 1

SKU: sx25051073251287759

M 3487 FT - 2

SKU: sx2409015255935290

M 3487 FT - 3

SKU: sk2409257212235785

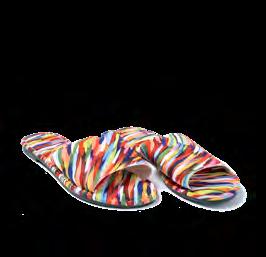

Shoe Women's Flower Slippers Germany VOCs (+, DMF)

Shoe Women's Waterproof Snow Boots Germany

Shoe Girls' Flower Clogs Portugal

Aromatic amines: 2,4-TDA, Heavy metals (Sb)

VOCs (+) & Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Phthalate: DBP (55x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sx2208087656858869

5

SKU: sx2407065708600234

3487 FT - 6

SKU: sx2309268046965801

Shoe Bubble Slide Slippers Germany

Shoe Men's Criss-Cross Slide Sandals Germany

PAH (NAP); Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP); PAH (PHE, FLU, PYR, CHR) & VOCs (+, DMF)

Phthalate: DBP (4.2x) & DEHP (39x)

Shoe Women's Rain Shoes Switzerland Phthalate (DBP, DEHP)

Phthalate: DBP (71x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein

SKU: sx2209220587811315

SKU: sx2409257684216101

SKU: sx25042395225517988

Shoe Men's Studded Combat Boots Germany

PAH (NAP, ANA, ACE, FLU, PHE, ANT, FLA, PYR, CHR, BaA, BbF, BjF, BkF, BaP, BeP, IcdP, DahA, BghiP); Heavy Metal (Pb), VOCs (+, DMF), Quinoline & Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Shoe Women's Ruched Pointed Fashion Boots Germany

VOCs (+, DMF) & PAHs (NAP, ANA, ACE, FLU, PHE, ANT, FLA, PYR, CHR, BaA, BaP, BeP, BghiP)

Shoe Women's Flat Slip-On Sandals Israel

PAH: NAP, FLU, PHE, ANT, FLA, PYR, CHR, BaA, BbF, BaP, BeP, IcdP, BghiP; Heavy metals (Cd, Pb) & Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP, DIP)

Phthalate: DEHP (28x), DINP (1.5x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sx2407298863657451

SKU: st25030399175495063

SKU: sm25040683897627921

Shoe

Women's Plus Size Short Snow Boots Austria

Shoe

Women's Lace-Up Platform Sneakers Austria

Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP, DEP) & VOCs (+, DMF)

Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Phthalate: DBP (134x) und VOC: DMF (1.1x)

Shoe

Men's Lightweight Running Sneakers Germany

Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP) & VOCs (+)

Phthalate: DBP (110x)

Phthalate: DBP (5x), DEHP (110x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sk2311231677695323

SKU: sz2408159102937006

SKU: sm2212213346647014

Top (T-shirt) Teen Girls' Graphic T-Shirt Switzerland

Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP) & Heavy metal (Sb)

Top (T-shirt) Women's Custom Printed T-Shirt Portugal Quinoline

Top (T-shirt)

Men's Metallic Short-Sleeve Button Shirt Israel

Heavy metals (Sb) & Phthalate (DEHtP)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sm2409146266001936

SKU: sm2208041350633838

SKU: sz2411143543072244

Top (Shirt)

Top (Shirt)

Men's 3D Christmas Hawaiian Shirt Portugal Heavy metal (Sb)

Top (Blouse)

Men's Loose Glitter Button-Up Shirt Switzerland Heavy metal (Sb)

Women's Sequin V-Neck Blouse Israel

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sm2211300945939410

SKU: sz2406275541714328

SKU: sz2409057697744399

Top (Shirt)

Jacket

Men's Reflective Splash-Ink Shirt Germany

Top (T-shirt)

Women's Cropped Fringe Leather Jacket Germany

Heavy metal (Sb)

Women's Santa Graphic T-Shirt Germany

Heavy metal (Sb) & Formaldehyde; VOCs(+)

Heavy metal (Sb) & Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sz2402299798805448

SKU: sz2410218552235515

SKU: sz2405096224476190

Dress

Women's Sequin Fishtail Party Dress Sweden

Dress

Women's Sequin Cocktail Dress Germany

Formaldehyde; Aromatic amine (PPD) & Heavy metal (Sb)

Dress

Women's Paisley Print Maxi Skirt Spain

Heavy metal (Sb); Formaldehyde

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sz2405280992220891

SKU: sw2209138758508600

SKU: sk2309192015124624

Dress

Dress

Women's Metallic Shimmer Two-Piece Set Germany

Heavy metals (Sb) & VOCs (+, DMF)

Women's Sequin Wide-Leg Jumpsuit Germany Heavy

(Sb)

Costume dress

Girls' Mesh Mermaid Dress & Headband Set Germany Formaldehyde Formaldehyde: (3.5x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sk2408084999389350

SKU: sk2412254123997662

SKU: sk2408071273732320

Dress

Tween Girls' 2-Piece Reversible Outfit Germany

Costume dress Girls' 'Frozen' Princess Dress Thailand

VOCs (+, DMF)

Heavy metal (Sb)

Top (T-shirt)

Boys' Dinosaur Lightning T-Shirt Israel

Heavy metal (Sb) & Phthalate (DEHtP)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 31

SKU: sk2411045510045491

M

FT - 32

SKU: sk25030591367491111

M 3487 FT - 33

SKU: sk2411135175179716

Costume dress

Shoe

Boys' Spider Superhero Costume Set Thailand

Costume dress

Girls' LED Roller Sneakers Spain

Heavy metal (Sb); Phthalate (DEHP) & VOCs (+)

Tween Girls' 3-Piece Ruffle Bikini Set Sweden

Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP); Bromine & VOCs (+)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 34

SKU: sk2407154412452525

M 3487 FT - 35

SKU: sk25022467866708972

M 3487 FT - 36

SKU: sx2309025137536549

Shoe Toddler Cartoon Rain Boots Sweden Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP)

Pyjamas

Girls' Glowin-the-Dark Pajama Set Thailand

Shoe Women's Platform Mary Jane Heels Thailand

Heavy metals (Sb)

Heavy metal (Cd); PAH (PHE, FLA, PYR, CHR, BaA); Phthalates (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP) & VOCs(+)

Heavy metal: Cd (1.2x) & Phthalate: DBP (1.1x), DEHP (110x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 37

SKU: sa2408272834527510

M 3487 FT - 38

SKU: sk2407162760755335

M 3487 FT - 39

SKU: sk2406178934043401

Shoe Kids' Thick Padded Snow Boots Germany VOCs (+)

Jacket Girls' Unicorn Fluffy Hooded Jacket Austria Heavy metals (Sb) & PFAS (8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH)

Jacket Toddler Girls' Unicorn Raincoat Spain Phthalates (DBP, DEHtP)

PFAS: ∑8:2

FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (1.8x)

SKU: st2501025550510174

FT - 42

SKU: st2309208171191818

3487 FT - 43

SKU: st2411143707130047

Jacket Women's Hooded Softshell Jacket Spain

PFAS (6:2FTOH, 8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH) & Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

PFAS: ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (634x) & Phthalate: DBP (1.1x), DEHP (120x)

Jacket Women's Outdoor Windproof Jacket Thailand

PFAS (6:2FTOH, 8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH)

Jacket Women's Casual Hooded Rain Jacket Israel

PFAS (PFOA, 6:2FTOH, 8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH)

PFAS: ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (519x)

PFAS: 6:2 FTOH (7.6x) & PFAS: ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (3269x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU Product

M 3487 FT - 44

SKU: sm2306014334316141

SKU: sm2410191710927828

- 46

SKU: sz2406011999887893

Jacket

Men's Casual Zipper Faux Leather Jacket Portugal

Formaldehyde; Nickel release (+) & VOCs (+)

Jacket Men's Thermal Waterproof Motorcycle Jacket Germany

Jacket Women's Letter Pattern Bomber Jacket Germany

Phthalates (DEHP, DEHtP) & VOCs (+)

Phthalate: DEHP (200x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein

SKU: sz2408139757945079

SKU: st2410243521722842

SKU: sh2404232402498418

Jacket Women's Shiny Thermal Winter Coat Germany

Heavy metal (Sb); VOCs (+); Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP); PFAS (8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH) & Formaldehyde

Phthalate: DEHP (7.2x) & PFAS: ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (1.8x)

Jacket Women's Casual Hooded Hiking Jacket Austria

PFAS (4.2 FTOH, 6:2FTOH, 8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH)

PFAS: 6:2 FTOH (140x) & ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (3.8x)

Jacket Adult Reflective Rain Suit (Jacket & Pants) Austria

Heavy metal (Cd); PFAS (4:2FTOH, 6:2FTOH, 8:2FTOH, 10:2FTOH); Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP) & APEO (NPE)

Phthalate: DEHP (20x); PFAS: ∑8:2 FTOH, 10:2 FTOH (677x) & APEO: NPE (1.3x)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

SKU: sx2404042379710014

SKU: sz2501104028729622

SKU: sz2411261770373817

Shoe

Women's Leopard Platform Beach Slides Germany

Heavy metal (Sb, Pb); PAH (NAP, ANA, ACE, FLU, PHE, ANT, FLA, PYR, CHR, BaA, BaP, BeP, IcdP, BghiP), Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP, DINP) & VOCs (+)

Heavy metal: Pb (2.8x) & Phthalate: DBP (19x), DEHP (33x), DINP (1.4x)

Top (Blouse) Floral Print Blouse Germany (Pop-Up Store)

Top (T-shirt)

Women's Slim-Fit Knitted T-Shirt Germany (Pop-Up Store)

Heavy metal (Sb) & Formaldehyde

Aromatic amine (Aniline)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 53

SKU: sk25031882366546146

M 3487 FT - 54

SKU: sS2105110064913765

M 3487 FT - 55

SKU: sk25031766136220011

Shoe Kids' 3D Duck Rain Boots Switzerland Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Pyjamas

Preschool Penguin T-Shirt & Shorts Set Germany

Top (T-shirt)

Tween Girls' Round-Neck Summer T-Shirt Germany

Heavy metal (Sb) & Phthalate (DEHP, DEHtP)

Heavy metal (Sb) & Phthalate (DBP, DEHP, DEHtP)

Product ID, Picture & Shein SKU

M 3487 FT - 56

SKU: st2409095242562340

M 3487 FT - 57

SKU: sk2410041092323392

Dress

Top (Pullover)

Women's Contrast Pocket Fitness Leggings

Boys' Graphic Animal Pullover Hoodie

Germany Heavy metal (Sb)

Germany Heavy

(Sb)

Abbreviations: VOCs (Volatile organic compounds), DMF (N,N-Dimethylformamide), PAH (Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), DBP (Dibutylphthalate), DEHP (Diethylhexyl phthalate), DEHtP (Di-(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate), DEP (Diethylphthalate), DINP (Diiso-butylphthalate), 2,4-TDA (2,4-toluoylenediamine), PPD (p-phenylenediamine), 6:2FTOH (6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol), 8:2FTOH (8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol), 10:2FTOH (10:2 fluorotelomer alcohol), APEO (Alkylphenol ethoxylate), NPE (Nonylphenol ethoxylate), Sb (Antimony), Pb (Lead), Cd (Cadmium), Ni (Nickel), NAP (Naphthalene), ACY (Acenaphthalene), ACE (Acenaphthene), FLU (Fluorene), PHE (Phenanthrene), ANT (Anthracene), FLA (Fluoranthene), PYR (Pyrene), CHR (Chrysene), BaA (Benz(a) anthracene), BbF (Benzo(b)fluoranthene), BjF (Benzo(j)fluoranthene), BkF (Benzo(k)fluoranthene), BaP (Benzo(a)pyrene), BeP (Benzo(e)pyrene), IcdP (Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene), DahA (Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene), BghiP (Benzo(g,h,i)perylene). + (Detected)

REACH-regulated chemicals tested and standard test methods used

Chemicals

Alkylphenol ethoxylate

Formaldehyde

Arylamines

Measurement method / Standard

DIN EN ISO 18254-1:2016-09, LC-MS / MS

DIN EN ISO 14184-1:2011-12

BVL B 82.02-2:2017-12 / DIN EN ISO 14362-1:2017-05

BVL B 82.02-15:2017-12 / DIN EN ISO 14362-3:2017-05

VOC screening PAW 078:2023-05

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) DIN EN 17681-1:2025-06

Heavy metals (eluate)

DIN EN 16711-2:2016-02 & DIN EN ISO 17294-2:2024-12

Heavy metals (fabric surfaces) XRF P504-506-1:01/2017 & DIN EN 62321-3-1:2014-10

Nickel release

DIN EN 112472:2004-04; DIN EN 1811:2015-10 & DIN EN ISO 17294-2:2017-01

Heavy metals (acid digestion): lead and cadmium DIN ISO 16711-1:2016-02 & DIN EN ISO 17294-2:2024-12

Phthalates

DIN EN ISO 14389:2023-01

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) AfPS GS 2019:01 PAK

Quinoline

Organotin compounds

DIN 54231

DIN EN ISO 22744-1:2020-09

Full report by the Bremer Umweltinstitut (Bremen Environmental Institute)

[1] K. Niinimäki, G. Peters, H. Dahlbo, P. Perry, T. Rissanen, und A. Gwilt, ”The environmental price of fast fashion“, Nat Rev Earth Environ, Bd. 1, Nr. 4, S. 189–200, Apr. 2020, http://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

[2] Greenpeace Africa, ”Fast Fashion Slow Poison“. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4africa-stateless/2024/09/925601ff-fastfashionslowpoison_reportbygreenpeace.pdf

[3] J. Rovira, M. C. O. Souza, M. Nadal, und J. L. Domingo, ”Human health risks from textile chemicals: a critical review of recent evidence (2019-2025)“, J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng, Bd. 60, Nr. 2, S. 79–91, 2025, http://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2025.2514406

[4] V. C. D. Pinto und M. Peleg Mizrachi, ”The Health Impact of Fast Fashion: Exploring Toxic Chemicals in Clothing and Textiles“, Encyclopedia, Bd. 5, Nr. 2, S. 84, Juni 2025, http://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5020084

[5] Greenpeace International, ”Dirty Laundry: Unravelling the corporate connections to toxic water pollution in China“, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2011/07/3da806cc-dirtylaundry-report.pdf

[6] M. Cobbing, V. Wohlgemuth, und L. Panhuber, ”Taking the Shine off SHEIN:A business model based on hazardous chemicals and environmental destruction“. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/S04261_Konsumwende_StudieEN_Mehr%20Schein_v9.pdf

[7] Statista, ”Estimated annual revenue of Shein from 2016 to 2023“. Januar 2025. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1360515/shein-estimated-annual-revenue/

[8] D. Cao und P. Li, ”Shein Revenue Neared $10 Billion in Quarter Before Tariffs“, The Business of Fashion, 31. Juli 2025. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.businessoffashion.com/news/retail/shein-revenueneared-10-billion-in-quarter-before-tariffs/ [9] [9] ECDB, ”Top fashion online stores worldwide in 2024.“ July 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/860718/top-online-stores-global-fashion-ecom mercedb

[10] Deutschlandfunk.de, ”Billigware aus China – EU und USA verschärfen Kurs gegen Shein und Temu“ [Cheap goods from China – EU and US tighten stance against Shein and Temu]. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/temu-shein-china-zoll-onlineshop-100.html

[11] M. Kläsgen und J. Schmieder, ”Fast Fashion: Shein, der vielleicht dreisteste Raubkopierer der Welt“ [Fast fashion: Shein, perhaps the world's most brazen pirate], Süddeutsche.de. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/shein-temu-ki-fashion-mode-1.6119095

[12] Friends of the Earth France, ”Quand la mode surchauffe“ [When fashion overheats]. 2023. [Online].

Available: https://www.amisdelaterre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/decryptage-fast-fashion-vdef.pdf

[13] Storyclash, ”Inside Shein’s Influencer Marketing Strategy“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.storyclash.com/blog/en/shein-germany-influencer-marketing/

[14] The European Consumer Organisation, ”Click to buy (more)“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.beuc.eu/sites/default/files/publications/BEUC-X-2025-051_How_fast_fashion_giant_SHEIN_uses_dark_ patterns.pdf

[15] EU Kommission, ”Online-Shopping: Commission and national authorities urge SHEIN to respect EU consumer protection laws, European Commission – European Commission. Accessed: 15. October 2025. [Online].

Available: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1331

[16] Shein, ”2024 Sustainability and Social Impact Report“, Juni 2025. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sheingroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/SHEIN-2024-Sustainability-and-Social-Impact-Report-Final-14-June.pdf

[17] Shein, ”SHEIN Conducted Over Two Million Product Safety Tests in 2024, Reinforces Commitment to Product Safety and Sustainability – SHEIN Group“. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sheingroup.com/ corporate-news/shein-conducted-over-two-million-product-safety-tests-in-2024-reinforces-commitment-to-product-safety-and-sustainability/

[18] Europäische Union, Verordnung (EG) Nr. 1907/2006. 2006. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006R1907

[19] ZDHC, ”ZDHC MRSL: Phthalates (including all other esters of ortho-phthalic acid)“. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheethtml?sheet=16

[20] European Chemicals Agency, ”ECHA CHEM database“, ECHA CHEM. Accessed: 3. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://chem.echa.europa.eu/

[21] ZDHC, ”PER–FLUOROALKYL AND POLY-FLUOROALKYL SUBSTANCES (PFAS)“. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheethtml?sheet=22

[22] Umwelt Bundesamt, ”PFAS Came to Stay“, Magazine of the German Environment Agency 1/2020, 2020.

[23] ZDHC, ”Chemical Information Document: Total Heavy Metals“. ZDHC. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheet?sheet=13

[24] P. Piccinini, C. Senaldi, und C. Summa, ”European Survey on the Release of Formaldehyde from Textiles“, JRC Publications Repository. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ repository/handle/JRC36150

[25] ZDHC Manufacturing Restricted Substances List (MRSL). Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheethtml?sheet=29

[26] ZDHC, ”Chemical Information Document: Polycyclic Aromartic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)“. ZDHC. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheet?sheet=17

[27] ZDHC, ”Chemical Information Document: Dyes – Azo (Forming Restricted Amines)“. ZDHC. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheet?sheet=6

[28] AG AFIRM Group, ”Chemical Information Sheet: QUINOLINE“. 2021. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://afirm-group.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/afirm_quinoline_v2.pdf

[29] ”mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheethtml?sheet=31“. Accessed: 14. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mrsl-30.roadmaptozero.com/guidancesheethtml?sheet=31

[30] S. Preuss, ”Greenpeace-Bericht: Gefährliche Chemikalien in Shein-Kleidung verstoßen gegen EU-Vorschriften“ [Greenpeace report: Dangerous chemicals in Shein clothing violate EU regulations], FashionUnited, 24. November 2022. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://fashionunited.de/nachrichten/mode/ greenpeace-bericht-gefaehrliche-chemikalien-in-shein-kleidung-verstossen-gegen-eu-vorschriften/2022112449241

[31] C. Throl und H. Baier, ”Ultra unnötig“ [Extremely unnecessary], ÖKO-TEST, Nr. Jahrbuch Kinder und Familie für 2025 [Children and Family Yearbook for 2025], S. 192–197, Dez. 2024.

[32] J. Cowley, S. Matteis, und C. Agro, ”Experts warn of high levels of chemicals in clothes by some fast-fashion retailers“, CBC News, 1. October 2021. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/marketplace-fast-fashion-chemicals-1.6193385

[33] AFP, ”Seoul authorities find toxic substances in Shein and Temu products“, France 24, 14. August 2024. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240814-seoul-authorities-find-toxicsubstances-in-shein-and-temu-products

[34] PubChem, ”PubChem“. Accessed: 9. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

[35] OEKO-TEX, ”DETOX TO ZERO“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.oeko-tex.com/en/our-standards/oeko-tex-step/oeko-tex-detox-to-zero/

[36] Greenpeace, „Self regulation: a fashion fairytale / Part 1: Progress of Detox committed brands on hazardous chemicals and slowing the flow/closing the loop“, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/20211122-greenpeace-detox-fashion-fairytale-engl-pt1.pdf

[37] Statista Market Insights, ”Apparel – Worldwide“, Statista. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: http://frontend.xmo.prod.aws.statista.com/outlook/cmo/apparel/worldwide?srsltid=AfmBOoq3Sf_JrbkzpsX1qRV2DsPIpExfXX7AvLbILtOnECDRweONd6qo

[38] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, ”A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning fashion’s future“. 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

[39] OC&C und WGSN, ”Doing more with less“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mlp.wgsn.com/ rs/669-IKC-742/images/WGSN_OC%26C_Doing_More_With_Less.pdf?aliId=eyJpIjoielY3eFl6bjM0Z01RSmtvYSIsInQiOiI5SkdMZzhRYklrRnhXQ2haWEdJUDBBPT0ifQ%253D%253D

[40] European Environment Agency, ”Circularity of the EU textiles value chain in numbers“. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/circularity-of-the-eu-textiles-value-chain-innumbers

[41] C. Löw, H. Lorösch, und K. Moch, ”Textilrecycling – Status Quo und aktuelle Entwicklungen“, 2024, [Online].

Available: https://www.oeko.de/fileadmin/oekodoc/Textilrecycling-Status-Quo.pdf

[42] Boston Consulting Group, ”Spinning Textile Waste into Value“. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/spinning-textile-waste-into-value

[43] Mc Kinsey, ”Sustainable style: How fashion can afford decarbonization“. Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/sustainable-style-how-fashion-can-afford-and-accelerate-decarbonization#/

[44] H. Ritchie, ”Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?“, Our World in Data, Sep. 2020, Accessed: 1. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector

[45] Textile Exchange, ”Materials Market Report“, 2024. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://textileexchange.org/knowledge-center/reports/materials-market-report-2024/

[46] European Environment Agency, ”Microplastics from textiles: towards a circular economy for textiles in Europe“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/microplastics-from-textiles-towards-a-circular-economy-for-textiles-in-europe

[47] Clean Clothes Campaign, ”Rana Plaza“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/past/rana-plaza

[48] Clean Clothes Campaign, ”What are the issues plaguing fashion?“ Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://cleanclothes.org/faq/why

[49] O. Classen und D. Hachfeld, ”Interviews with factory employees refute Shein’s promises to make improvements“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.publiceye.ch/en/topics/fashion/interviews-with-factory-employees-refute-sheins-promises-to-make-improvements

[50] Statista, ”Mode und Bekleidung – Meistbesuchte Websites weltweit 2025“ [Fashion and clothing – Most visited websites worldwide in 2025]. August 2025. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://de.statista.com/ statistik/daten/studie/1379969/umfrage/meistbesuchte-websites-mode-bekleidung-weltweit/

[51] Reuters, ”Greenwashing handelt Shein hohe Geldstrafe in Italien ein“ [Greenwashing lands Shein a hefty fine in Italy]. Accessed: 15. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/handelkonsumgueter/modehandel-greenwashing-handelt-shein-hohe-geldstrafe-in-italien-ein/100146112.html

[52] J. G. SWR, ”Wie chinesische Onlinehändler den europäischen Zoll austricksen“ [How Chinese online retailers are circumventing European customs], tagesschau.de. Accessed: 15. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/verbraucher/temu-pakete-zoll-steuern-100.html

[53] Shein, ”Sharing Our 2021 GHG Emissions Inventory and Plans to Reduce Emissions – SHEIN Group“. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sheingroup.com/corporate-news/press-releases/2021-ghg-emissions-inventory/

[54] Greenpeace, ”Self regulation: a fashion fairytale / Part 1: Progress of Detox committed brands on hazardous chemicals and slowing the flow/closing the loop“, 2021. [Online].

Available: https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/20211122-greenpeace-detox-fashion-fairytale-engl-pt1.pdf

[55] ”French Senate adopts bill to regulate fast fashion industry“, France 24. Accessed: 2. October 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250610-french-senate-to-vote-on-regulating-fast-fashion

[56] République française, ”Proposition de loi visant à réduire l’impact environnemental de l’industrie textile – Dossiers législatifs – Légifrance“ [Proposed law aimed at reducing the environmental impact of the textile industry –Legislative files – Légifrance]. Accessed: 13. October 2025. [Online].

Available: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/dossierlegislatif/JORFDOLE000049284718/

[57] European Union, Waste Framework Directive. 2008 (Last Revised 16.10.2025). [Online].

Available: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj

Imprint

Greenpeace e. V., Hongkongstraße 10, 20457 Hamburg; Phone +49 40 306 18 - 0 Press Office Phone +49 40 306 18 - 340, F +49 40 3 06 18 - 340; presse@greenpeace.de; www.greenpeace.de Political Unit in Berlin Marienstraße 19-20, 10117 Berlin; Phone +49 30 30 88 99 - 0 Responsible for content Moritz Jäger-Roschko Text/Editor Moritz Jäger-Roschko, Julios Armand Kontchou, Andrea Nolte Photos Fred Dott (Cover, p. 12, 15, 18 – 36); Kevin McElvaney (p. 5, 13), Florian Manz (p. 7, 8, 9); Jana Kühle (p. 14); Paul Lovis Wagner (p. 16), all: © Greenpeace

Layout/Design Janitha Banda/Spektral3000 November 2025

greenpeace.org