Carbon accounting as a strategic imperative for private equity fund managers

Why greenhouse gas emissions measurement and governance now deliver a competitive advantage in private markets

January 2026

Executive summary

Private equity fund managers are at a pivotal point in the global transition to a low-carbon economy. Carbon accounting has evolved into a strategic imperative that drives investment resilience, regulatory alignment, and long-term value creation. This paper explains why robust greenhouse gas (“GHG”) measurement and governance now provide a competitive advantage in private markets.

Investor expectations are rising sharply, with over 70% of global limited partners (“LPs”) assessing general partners (“GPs”) on their ability to measure and reduce financed emissions (PRI, 2023). Climate competence is increasingly linked to fiduciary performance and the cost of capital, while regulatory frameworks such as International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) S2, European Sustainability Reporting Standard (“ESRS”) E1, and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”) embed emissions accounting into financial disclosure and governance. Beyond compliance, carbon performance influences valuation, exit timing, and access to sustainability-linked financing, making emissions data a critical input for strategic decision-making.

Despite these benefits, significant challenges remain. Scope 3 emissions continue to be the hardest to measure and manage, creating coverage gaps and data quality issues that undermine comparability and investor confidence. Methodological trade-offs between topdown and bottom-up approaches require careful alignment with purpose, as each offers distinct advantages and limitations. Emerging risks from AI-driven tools further complicate the landscape, introducing concerns around data integrity, regulatory compliance, and governance that demand human oversight.

To navigate these complexities, fund managers should establish robust carbon baselines across portfolios; focus on material emissions sources across their portfolio; and implement clear data quality policies and improvement roadmaps. A hybrid approach, using top-down methods for rapid coverage and bottom-up methods for decision-grade insights, offers a practical pathway to accuracy and scalability. Integrating carbon metrics into investment processes, 100-day plans, and exit strategies will strengthen value creation, while governance frameworks for AI-enabled tools will ensure auditability and compliance. Although geopolitical uncertainty and regulatory pushback persist, market forces driven by technology, economics, and risk management are accelerating decarbonisation. Fund managers who act decisively will not only mitigate climate risk but also unlock competitive advantages in a rapidly evolving global economy.

1. Introduction

Private equity sits at a unique intersection of influence and responsibility in the global economy. Across developed markets, private capital owns a substantial share of midmarket industrials, manufacturing, logistics, consumer goods, and infrastructure companies. With the widespread impacts of the economic transition, the imperative to decarbonise, and the threat of physical climate risk, most of these companies have an impetus to consider climate change in a strategic way.

At the same time, LP expectations have shifted. Pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and insurance investors increasingly require private-market managers to demonstrate clear oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities. A 2023 PRI survey found that over 70% of global LPs assess GPs on their ability to measure and reduce financed emissions (PRI, 2023). The largest allocators now link climate competence with fiduciary performance.

Finally, the regulatory landscape has matured. The European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR”), international accounting standards (IFRS S2, part of the ISSB standards for sustainability disclosure), and climate-risk frameworks (TCFD) all embed emissions accounting and climate strategy in the definition of corporate governance and financial disclosure. Even where fund-level regulation remains relatively light, portfolio companies in developed markets are increasingly subject to mandatory disclosure.

In this context, carbon accounting is no longer simply one component of ESG reporting. It is the foundation for strategic decisions across the investment cycle, from due diligence to value creation, capital expenditure (“CapEx”), and exit planning. Having an accurate, up-to-date carbon footprint is a cornerstone of managing climate risks.

That being said, there are still several challenges and pitfalls that private equity fund managers encounter related to both their own and their portfolio companies’ carbon footprints. A lack of data-native approach, opaque estimation methods, and new technologies with unclear underlying methodologies result in a credibility gap.

In this paper, we aim to set out why a carbon footprint is a strategic imperative for fund managers. We then explore common pitfalls and challenges that companies face, from Scope 3 data gaps to methodological choices like bottom-up versus top-

down approaches, and the emerging risks of relying too heavily on AI-driven tools without proper oversight. We also offer our perspective on the evolving role of carbon in a shifting geopolitical landscape, where climate policy, trade, and energy security are increasingly intertwined.

2. Primer on carbon accounting for fund managers

Carbon accounting (also referred to as carbon footprinting or compiling a GHG inventory) is the process of evaluating a company’s GHG emissions to understand its contribution to climate change and identify opportunities for reduction. The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard has become the de facto approach to compiling a GHG inventory.i The GHG Protocol has been supplemented by the Scope 2 Guidance and Scope 3 Standard, and there is ongoing work being undertaken to update these standards. The GHG Protocol categorises GHG emissions into three main scopes (shown in Figure 1):

• Scope 1: Direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by the company, such as fuel combustion in company vehicles or on-site boilers.

• Scope 2: Indirect emissions from purchased energy, primarily electricity, heating, or cooling consumed by the company.

• Scope 3: All other indirect emissions across the value chain. Scope 3 is further subdivided into 15 categories, such as purchased goods and services, employee commuting, or downstream transportation.

As GHG emissions are seldom measured directly (except by industry and utilities), determining a company’s carbon footprint typically relies on using proxy data (e.g., fuel use, electricity consumption) and emission (conversion) factors to approximate GHG emissions in carbon dioxide-equivalent (“CO₂e”) terms.ii This uniform approach

Figure 1: Diagram illustrating different carbon footprint scopes.

enables companies to set reduction targets, track progress, and report transparently to stakeholders.

Scope 3, often the largest share of a company’s carbon footprint (often 95% or greater) (Carbon Disclosure Project and Boston Consulting Group, 2024), is made even more complex by the dependence on third parties for GHG emissions data. Throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, the focus of carbon accounting was on large companies and their Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions.

However, Scope 3’s broad applicability and the importance of value-chain engagement as a decarbonisation lever has also greatly increased the attention paid to these indirect emissions.

The general process followed to determine a company’s carbon footprint includes the following steps:

In addition to the GHG Protocol and ISO standards, the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (“PCAF”) has published three standards relevant to the financial sector. Financial sector companies’ GHG emissions are primarily linked to their financing activities (referred to as Scope 3 Category 15 – Financed Emissions by the GHG Protocol). PCAF provides a standardised approach for these companies to determine their financed emissions carbon footprint while taking into account that only some of an investee’s GHG emissions should be attributed to the investor.

For example, a trucking company would typically determine the carbon footprint of its entire fleet of trucks, but only the portion that is financed by a bank is attributed to the bank’s financed emissions. For fund managers, this typically means determining the attribution factor of portfolio companies’ GHG emissions.iii A full guide on performing a carbon footprint is beyond the scope of this document, and for more details on the process, we direct readers to the GHG Protocol and PCAF

Step 1: Scoping

Step 5: Calculation and reporting of carbon footprint

3. Strategic importance to fund managers

3.1 Investors increasingly evaluate carbon metrics as signals of value and resilience

Carbon performance is no longer just an ESG data point; it is also increasingly being used as a financial signal. High emissions correlate with higher exposure to carbon pricing risk, supply-chain disruption, CapEx needs, and transition risk (IPCC AR6, NGFS). LPs (especially pension funds and sovereign wealth funds) are now requiring PCAF-quality emissions data at the mandate level. A review by McKinsey (2023) found that major LPs factor emissions intensity and decarbonisation potential into mandate design and manager selection.

Furthermore, the cost of capital is beginning to diverge between climate-aligned and climate-exposed firms. Investors and lenders increasingly price climate risk into capital allocation decisions. Firms with credible transition plans or strong ESG performance often enjoy lower financing costs, while those exposed to transition or physical risks face higher costs (TCFD, 2021; MSCI, 2023). In debt markets, most sustainability-linked loans (“SLLs”) include emissions KPIs to set pricing curves (LMA, 2023). SLLs tie loan pricing (margin ratchets) to sustainability performance targets, often including GHG emissions reduction KPIs. If targets are met, borrowers receive a margin discount.

The global shift towards lower-carbon economies affects valuation differentiation, competitive positioning, and exit timing. This is influenced by factors such as carbon pricing and regulatory pressure that increase operating costs of emissions intensive businesses, and disruptive technologies that create winners and losers across sectors (CDP, 2023). Climate-aligned private equity demonstrates stronger longterm value creation where decarbonisation reduces OpEx, CapEx risk, and earnings volatility (Bain, 2025; KPMG, 2024; BCG, 2024). Carbon accounting is the visibility mechanism through which private equity firms understand exposure, identify levers, and shape strategy.

In private equity and private credit in particular:

• Vendors increasingly expect buyers to price carbon and assess decarbonisation investment needs.

• Data-rich asset managers can spot transition-aligned assets earlier and more accurately.

• Funds with strong carbon baselines can structure sustainability-linked loans, KPIs, and value-creation plans more credibly.

Carbon accounting is foundational to climate-risk analysis and pricing. Climate-risk frameworks (TCFD, NGFS, ECB/DNB stress tests) require emissions data to quantify transition-risk exposure, sensitivity to carbon-pricing trajectories, sector-level decarbonisation pressure, and pathways such as the International Energy Agency (“IEA”) or Network for Greening the Financial System (“NGFS”) scenarios. Without robust emissions accounting, climate-risk models degrade into guesswork.

Carbon accounting is becoming integral to operational efficiency and data strategy at technology-led funds. Fund managers are moving toward automated and centralised climate data collection, calculation and streamlined reporting, and integration of emissions into core portfolio-management benchmarking and analytics. This shift is moving carbon data from ESG-only to mainstream investment operations.

3.2 Carbon accounting as a value -creation tool

Historically, carbon emissions reporting was often considered part compliance or qualitative box-ticking. Today, emissions insights drive real operational and strategic value by enabling cost savings, stronger supply chain competitiveness, and improved market positioning. Energy costs remain a significant input for many portfolio companies. Emissions data can help these companies identify energy efficiency opportunities, processes suitable for electrification or fuel switching, and opportunities for improved controls and energy recovery.

A 2022 study by the IEA found that energy efficiency investments in manufacturing deliver median returns of 18–32% compared to baseline, depending on the technology. These opportunities are difficult to systematically identify without structured carbon accounting.

Large corporates, especially listed ones, increasingly require suppliers to disclose emissions data and reduction plans, with many committing to significant Scope 3 reductions (including purchased goods, services, and capital goods). By implementing carbon accounting, portfolio companies can meet these requirements, safeguard key relationships, unlock new opportunities, and gain a competitive edge.

In Northern Europe, this trend is borne out in the public sector with the growing popularity of the CO2 Performance Ladder programme. Under this programme, companies that have been certified as compliant (basic compliance involves performing a carbon footprint) can receive a commercial benefit on participating tenders. Participation in the programme has grown steadily since its inception in the early 2010s, with nearly 2,000 businesses now certified.

Leading private equity firms now integrate carbon metrics and decarbonisation trajectories directly into 100-day plans,iv value-creation programmes, or

Environmental and Social Action Plans (“ESAPs”). This helps identify CapEx priorities, establish KPIs, tie management incentives to decarbonisation outcomes, and prepare companies for exit valuations that increasingly consider climatereadiness. Carbon accounting enables these firms to translate climate competence into financial upside.

3.3 Carbon accounting is key to risk management

Fund managers and portfolio companies face various climate-related risks. For carbon accounting, transition risks are particularly relevant; these include regulatory, market, technological, reputational, and legal risks. While not the sole factor, a complete carbon inventory is essential for conducting a thorough transition risk assessment (Khan et al., 2024).

Quantifying Scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emissions allows fund managers to identify exposure to carbon pricing, potential for stranded assets, reliance on fossil-energy or feedstocks, and operational vulnerabilities. Without a carbon footprint, fund managers and portfolio companies must rely on sector analysis, which may not consider the nuance of individual firms. In addition, companies that want to assess climate impacts on their long-term strategy will find scenario analysis far less useful without an emissions baseline (TCFD, 2021).

Finally, credible carbon accounting is an essential step in limiting reputational risk linked to greenwashing and greenhushing allegations. Despite growing scrutiny, many companies still make green claims with insubstantial supporting data that doesn’t hold up to scrutiny (EU Commission, 2023). With an accurate and reliable carbon footprint, companies can accurately gauge and report their climate impacts to the public.

3.4 Regulatory convergence

Transparent carbon reporting is core to many ESG reporting standards in use or under development. Across the EU, UK, and other major global markets, regulatory frameworks are hard-wiring GHG accounting into reporting requirements. In the EU, ESRS E1 has extensive GHG reporting requirements, including an independent assurance requirement. While the application of the ESRS is limited in its current state (and will likely remain so in the context of the omnibus proposals), many large financial institutions are subject to it and are therefore increasing data requirements for the service providers and clients in their value chain. More directly, fund managers in the EU also have SFDR disclosure requirements. Internationally, uptake of IFRS S2 is also growing.

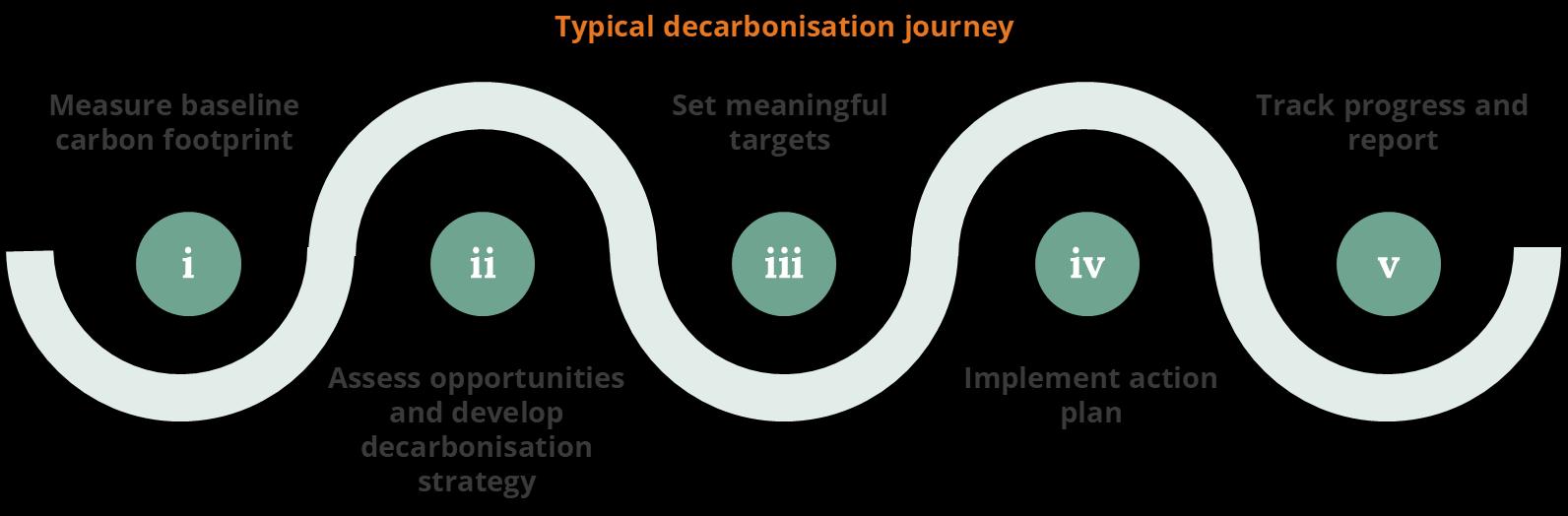

3.5 Underpinning credible net -zero transition commitments and strategies

A comprehensive carbon footprint baseline is an early step in a credible decarbonisation journey, as shown in the figure below. Leading investor alliances (e.g., NZAM, NZAOA, PAII, PMDR) and standard setting frameworks such as the Science Based Targets initiative and the Financial Institutions Net Zero standard (SBTi FINZ) all anchor decarbonisation pathways in financed-emissions baselines. The Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance’s (“NZAOA”) Target Setting Protocol v3/4 requires asset-class-level baselines, sector pathways, and year-on-year performance tracking. Financial institutions reporting to the Science-based Target Initiative (“SBTi”) must provide accurate and verifiable Scope 1, 2, and Scope 3 Category 15 (Financed Emissions). Fund managers cannot credibly claim to manage climate risk if carbon accounting lags behind.

Figure 2: Diagram showing an illustrative decarbonisation journey

4. Challenges and pitfalls

4.1 The Scope 3 data dilemma: coverage and quality

Despite the progress that has been made and the maturing carbon reporting frameworks, Scope 3 emissions remain the hardest to measure and manage for most companies. According to the SBTi, nearly half of companies are currently off track in meeting their Scope 3 goals, highlighting the need for more effective strategies (SBTi, 2023).

Scope 3 emissions encompass a wide range of activities, from upstream supplier operations to downstream product use and disposal. This breadth creates two major challenges: coverage gaps and data quality issues. Global supply chains are fragmented, and many suppliers lack the systems or incentives to provide accurate emissions data. Downstream, estimating emissions from product use and end-of-life treatment requires assumptions about consumer behaviour, energy mixes, and product lifecycles – heterogeneous factors largely outside a company’s control.

For portfolio companies and other corporates, incomplete GHG emissions data complicates operational decisions, such as supplier selection, logistics optimisation, and prioritising emissions-reduction initiatives – choices that can directly impact compliance and cost efficiency. For fund managers, data gaps undermine due diligence, making it harder to assess ESG risks and opportunities during acquisitions, and weaken value creation by limiting the ability to identify efficiency gains or enhance exit valuations. Inconsistent methodologies also hinder comparability across assets, increasing reputational and regulatory exposure. These challenges are becoming more material as regulatory frameworks tighten and investor scrutiny intensifies.

To address these gaps, companies often rely on secondary data or industry averages. While this makes assessments easier to scale, it compromises both coverage (by oversimplifying complex value chains) and quality (by reducing accuracy and comparability) (Buchenau, Oetzel, and Hechelmann, 2024; UNFCCC, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2023). This issue is particularly evident in sectors such as automotive, apparel, and technology, where value chains are especially complex.

These industries depend on multi-tier suppliers, extensive outsourcing, and frequent product refresh cycles, making it difficult to obtain consistent supplier-specific emissions data and to assign emissions accurately across products. As a result, companies in these sectors rely more heavily on spend-based or generic emission factors, leading to higher uncertainty and reduced accuracy and decision-usefulness of reported estimates (Buchenau, Oetzel, and Hechelmann, 2024; UNFCCC, 2023;

World Economic Forum, 2023). Methodologies vary widely, from spend-based models to supplier-specific data, complicating benchmarking and assurance.

For investors, poor Scope 3 data quality – particularly in Category 15 (Investments) –creates significant challenges in aggregating financed emissions across portfolios, identifying hotspots, and benchmarking performance. While the PCAF standards provide a robust methodology for quantifying these emissions, data availability remains uneven across asset classes and buy-and-build strategies often exacerbate inconsistencies when subsidiaries use different emission factors.

What can fund managers do?

As a first step, having portfolio companies focus on material Scope 3 categories ensures resources are focused where emissions impact is greatest. Research shows that one or two categories often account for most Scope 3 emissions, making targeted data collection far more efficient than full coverage upfront (ICE, 2023). The integration of materiality assessments allows firms to set clear timelines for expanding data coverage as data maturity improves, while maintaining credibility with investors.

Firms can further reduce data coverage and quality risks by implementing portfoliowide data quality policies and scoring systems. This includes defining acceptable methods per category, factor sources, and improvement timelines, e.g., via PACT/Pathfinder exchanges (PCAF, 2022; WBCSD, 2023). Moreover, deploying technology platforms that automate data collection and validation can minimise manual errors and improve comparability. These tools can also enable scenario modelling and performance tracking, which are critical for meeting investor and regulatory expectations for forward-looking climate risk management.

Lastly, fund managers should consider third-party verification as a key step to strengthen Scope 3 data integrity. Independent assurance not only validates reported emissions and identifies reporting gaps but also ensures alignment with climate disclosure frameworks. Beyond compliance, verification adds strategic value by maintaining investor trust and demonstrating robust climate risk management.

4.2 Methodological trade -offs: bottom -up vs. top -down

Carbon accounting methodologies fall broadly into two categories: top-down and bottom-up.

• Top-down methods, including environmentally extended input-output (“EEIO”) models,v offer speed and coverage by relying on sector averages and financial performance data (e.g., revenue). These are useful for initial

screening or estimating exposure but lack the fidelity needed for performance management or contractual KPIs. They can misplace emissions hotspots and are sensitive to price fluctuations, making them risky as a primary tool (WBCSD, 2023; IPCC, 2023).

• Bottom-up methods use supplier-specific or process-level data to deliver high-resolution insights at the site or product level. This granularity enables targeted interventions such as input substitutions, stock keeping unit redesigns, and supplier switching. It can support robust reporting, auditability, and sustainability-linked financing. Though resource-intensive, bottom-up accounting is consistently seen as more precise and defensible (GHG Protocol, 2024; ISO/IEC 42001, 2023).

What can fund managers do?

Fund managers should adapt the approach based on the purpose of carbon accounting within their investment cycle and overall strategy:

• Use top-down approaches for rapid portfolio coverage, initial screening, and regulatory reporting where completeness is the priority.

• Apply bottom-up methods for holdings that are material to climate targets or investor commitments, as these provide the detail needed for engagement and performance management.

Many companies adopt a hybrid approach, using top-down data to conduct a broad, high-level assessment and fill gaps, then transitioning to bottom-up methods as systems mature. This approach is consistent with SBTi guidance, which accepts the use of estimates where primary data is not yet available. However, SBTi also emphasises that companies should work to improve data quality over time, as heavy reliance on estimates can create challenges for decarbonisation planning and lead to significant discrepancies once better data becomes available.

Evidence from municipal construction and AI-assisted tender analysis shows that bottom-up methods yield materially different results than top-down Multi-Regional Input-Output (“MRIO”) estimates, reinforcing their role in decision-grade carbon accounting (NIST AI RMF, 2023; EU AI Act, 2024). This underscores the importance of prioritising bottom-up data for assets that drive climate targets, while using topdown estimates as a starting point for coverage and risk mapping.

4.3 Risks of using AI -related tools

AI is increasingly being applied to streamline carbon accounting processes, from data aggregation to predictive modelling. While AI offers efficiency gains, it introduces risks that businesses must manage carefully.

1. AI models are less reliable in managing data gaps. In the context of Scope 3 emissions, where data is often incomplete, inconsistent, or based on estimates, AI-driven outputs can amplify inaccuracies rather than resolve them (NIST, 2023). AI-models can, for example, overlook or fill data gaps without communicating this to the user.

2. AI lacks the nuanced judgment required to navigate evolving regulatory frameworks. Without human oversight, companies risk non-compliance, as standards such as CSRD and IFRS S2 continue to evolve (EU, 2024).

3. An over-reliance on AI for emissions improvements can create blind spots in broader ESG performance. For example, an AI-driven procurement tool might recommend switching to a lower-emission supplier without considering whether that supplier adheres to fair labour practices or human rights obligations. This narrow focus on carbon metrics can expose companies to reputational and legal risks, particularly under emerging due diligence regulations like the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDDD”).

What can fund managers do?

These risks are not limited to corporate operations – they extend to the investment landscape as well. For fund managers, AI adoption across portfolio companies raises governance and liability questions. The EU AI Act and frameworks like the NIST AI RMF or ISO/IEC 42001 establish expectations for inventorying, documenting, and monitoring AI systems. Investors should ensure that portfolio companies deploying AI in carbon accounting maintain audit trails, freeze conversion factor libraries per reporting cycle, and involve human reviewers. Without such controls, portfolio-wide GHG inventories risk challenge during verification or by LPs.

Carbon accounting remains a complex, evolving challenge at both corporate and portfolio levels. Companies must address data gaps, navigate methodological tradeoffs, and manage emerging AI risks while ensuring compliance and credibility. For investors, these same pitfalls translate into portfolio-wide comparability issues, diligence risks, and exposure to LP scrutiny. A balanced approach – combining rigorous data governance, hybrid methodologies, and responsible AI integration – will be essential for building robust, future-proof carbon accounting systems that create both climate impact and financial value.

5. Carbon in the geopolitical environment

In the challenging macroeconomic environment of today, where pushback on ESG regulation had gained momentum and sustainability requirements were being diluted in some jurisdictions, decarbonisation efforts often found themselves subordinated to more immediate geopolitical and commercial priorities. Yet underneath the surface, shifting technological and market dynamics are reshaping the global energy landscape in ways that may ultimately transcend short-term political considerations.

The renewable technology sector continues its rapid scaling, with solar panel costs decreasing by 30% from 2022 to 2024 and prospective solar and wind capacity growing by over 20% globally in 2024 (IEA, 2024; Global Energy Monitor, 2024). AIpowered innovations are springing up across battery technology, advanced geothermal systems, small modular reactors, and grid infrastructure upgrades. A combination of expanding capacity, more efficient supply chain integration, and increased recycling capabilities continue to drive battery prices down (IEA, 2025; IDTechEx, 2025). These technological developments are hastening the onset of electrification tipping points in various economies, where the economics of clean energy reaches self-sustaining momentum (e.g., battery electric cars in Norway (Global Tipping Points, 2025).

Moreover, climate change presents both escalating costs and emerging opportunities that are reshaping investment calculations. The economics are stark: physical climate change costs the global economy $16 million per hour (World Economic Forum, 2023). For the world’s largest companies, the total cost of climate risk can reach $1.2 trillion annually by 2050 (S&P Global, 2025). As climate risks translate into tangible business impacts, from supply chain disruptions to lost productivity and physical asset damage, companies are discovering that climate resilience has become a core business imperative. Traditional financial metrics now incorporate climate risk premiums, affecting everything from capital access to longterm planning, and concerns are growing that climate risk may render some assets uninsurable (Thallinger, 2025).

We anticipate that while short-term political priorities may slow coordinated global action, the fundamental economics of the energy transition suggest that market dynamics will increasingly take precedence. Driven by cost competitiveness, risk management, and technological capabilities, market forces may ultimately prove more decisive than political agreements in driving the pace and scale of decarbonisation.

Even so, indirect policy is also driving decarbonisation due to renewable energy being a potential key to energy sovereignty. While already presented in the EU REPowerEU roadmap in 2022, rising geopolitical tension has accelerated progress on this front (IEA, 2025; Bosshard, 2025). Therefore, even as sustainability regulation gets reduced by the EU Commission, decarbonisation progress is likely to continue (and even accelerate).

One silver lining in 2025 was China’s announcement of a 7-10% reduction in its peak GHG emissions by 2035, the first absolute target the country has committed to. While still rated as highly insufficient by Climate Action Tracker (Climate Action Tracker, 2025), the commitment is the latest in a series of positive signals for the world’s largest emitter (Hilton, 2025).

Conclusion

Carbon accounting has moved from a compliance exercise to a strategic imperative that underpins business resilience, investor confidence, and long-term value creation for fund managers and their portfolio companies. Fund managers that adopt robust methodologies and integrate carbon considerations into their investment process will be best positioned to navigate regulatory shifts and stakeholder expectations, and to increase long-term value creation potential.

While challenges such as Scope 3 data gaps, methodological trade-offs, and emerging AI risks persist, these can be mitigated through rigorous data governance, hybrid approaches, and human oversight. Fund managers should ensure portfolio companies focus on reporting material Scope 3 emissions sources and have plans in place to improve the overall quality of the carbon footprint over time. Moreover, managers should make sure carbon accounting approaches are fit for purpose. Top down estimation approaches are better suited to investment screening, while bottom up approaches are recommended for risk management and decarbonisation planning.

Even though geopolitical instability and pushback on sustainability regulation persists, market dynamics underscore that decarbonisation is no longer solely policy-driven; it is increasingly shaped by technology, economics, and risk management.

It is our view that fund managers that act decisively will not only reduce climate risk but also unlock competitive advantages in a rapidly evolving global economy.

i The ISO 14060 family of standards is also widely used and accepted in regulated reporting standards such as the ESRS. Further, the GHG Protocol and ISO have recently announced a project to deliver unified carbon accounting standards

ii CO2-equivalent is a single, catch-all unit that represents the combined Global Warming Potential of different types of GHGs, such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, etc.

iii The attribution factor is an asset-class specific factor used to apportion emissions. Generally, for fund managers it is the outstanding amount divided by the total equity and debt of the portfolio company.

iv A roadmap used by many private equity firms for the period immediately after deal close, focusing on establishing momentum on strategic aspects.

v Environmentally Extended Input-Output (EEIO) modelling links monetary flows between sectors with their environmental intensities (e.g., emissions per dollar), allowing us to estimate how the production in one sector indirectly drives environmental impacts across other sectors through economic interdependencies.

Bibliography

• Arxiv. (2024) Carbon accounting in the age of AI. Available at: https://arxiv.org/html/2410.01818v1

• Bain. (2025) Decarbonization that works: Five key actions in private equity. Available at: https://www.bain.com/insights/decarbonization-that-works-five-key-actions-in-privateequity-ceo-sustainability-guide-2025/

• BMJ. (2024) Climate change and health: A call to action. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/388/bmj.r505.full.pdf

• Bosshard, V. (2025) Energy sovereignty in Europe: What’s at stake? Available at: https://www.meer.com/en/91678-energy-sovereignty-in-europe-whats-at-stake

• Boston Consulting Group (“BCG”). (2024) Where are private equity firms on their way to net zero? Available at: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/private-equity-firmsnet-zero

• Buchenau, N., Oetzel, J. and Hechelmann, R.H. (2024) Category-specific benchmarking of Scope 3 emissions for corporate clusters. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 208, p.115019. Available at: https://kobra.uni-kassel.de/items/48ed6f9f-7f7647a1-a3ea-b9f5e3ba9c9d

• Carbon Disclosure Project. (2023) Climate change questionnaire: Guidance for companies.

• Carbon Disclosure Project and Boston Consulting Group. (2024) Scope 3 upstream: Big challenges, simple remedies. Available at: https://cdn.cdp.net/cdpproduction/cms/reports/documents/000/007/834/original/Scope-3-UpstreamReport.pdf

• Climate Action Tracker. (2025) China country summary. Available at: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/china/

• Crownhart, C. (2025) In a first, Google has released data on how much energy an AI prompt uses. Available at: https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/08/21/1122288/google-gemini-ai-energy/

• European Commission. (2023) Green Claims Directive proposal. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu

• European Commission. (2024) EU Artificial Intelligence Act. Available at: https://eurlex.europa.eu

• GHG Protocol. (2024) Scope 3 calculation guidance. Available at: https://ghgprotocol.org

• GHG Protocol. (2024) Scope 3 Subgroup B discussion paper. Available at: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/Scope%203-Subgroup%20BMeeting1-Discussion%20paper-%20final.pdf

• GHG Protocol. (2024) Corporate value chain (Scope 3) standard. Available at: https://ghgprotocol.org

• Global Tipping Points. (2025) Global tipping points report 2025. Available at: https://global-tipping-points.org/positive-tipping-points/

• Hilton, I. (2025) As U.S. and E.U. retreat on climate, China takes the leadership role. Available at: https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-climate-diplomacy

• ICE. (2023) Scope 3 materiality: The full picture. Available at: https://www.ice.com/insights/sustainable-finance/scope-3-materiality-the-full-picture

• IDTechEx. (2025) Energizing electrification – A future of batteries, AI and hydrogen. Available at: https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-article/energizing-electrification-afuture-of-batteries-ai-and-hydrogen/33585

• IFRS Foundation. (2025) ISSB standards for sustainability disclosure. Available at: https://www.ifrs.org

• International Energy Agency (“IEA”). (2022) Energy efficiency 2022 report. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2022

• IEA. (2024) Overview and key findings – World energy investment 2024. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024/overview-and-key-findings

• IEA. (2025) The battery industry has entered a new phase. Available at: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-battery-industry-has-entered-a-new-phase

• IEA. (2025) World energy outlook 2025. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/worldenergy-outlook-2025

• Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”). (2023) AR6 synthesis report. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch

• International Organization for Standardization (“ISO”). (2023) ISO/IEC 42001: AI management system standard. Available at: https://www.iso.org

• Khan, F., Byers, E., Carlin, D. and Riahi, K. (2024) Science-based principles for corporate climate transition risk quantification. Nature Climate Change, 14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02067-2

• KPMG. (2024) Climate, decarbonization, and nature strategy for private equity. Available at: https://kpmg.com/kpmg-us/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2024/climate-decarbonizationnature-strategy-private-equity.pdf

• Loan Market Association. (2023) Sustainability-linked loan principles.

• McKinsey and Company. (2023) Climate investing: The state of play in private markets.

• MSCI. (2023) Climate and credit: How climate risk influences credit spreads.

• National Institute of Standards and Technology (“NIST”). (2023) AI risk management framework. Available at: https://airc.nist.gov

• Oviedo, F., Kazhamiaka, F., Choukse, E., Kim, A., Luers, A., Nakagawa, M., Bianchini, R. and Lavista Ferres, J.M. (2025) Energy use of AI inference: Efficiency pathways and testtime compute. Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2509.20241

• Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (“PCAF”). (2022) Global GHG accounting and reporting standard for the financial industry. Available at: https://carbonaccountingfinancials.com

• Science Based Targets Initiative (“SBTi”). (2024) Ambitious corporate climate action. Available at: https://sciencebasedtargets.org

• SBTi. (2024) Corporate net-zero standard. Available at: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/net-zero

• SBTi. (2024) Standards and guidance. Available at: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/standards-and-guidance

• S&P Global. (2025) For the world’s largest companies, climate physical risks have a $1.2 trillion annual price tag by the 2050s. Available at: https://www.spglobal.com/sustainable1/en/insights/special-editorial/ceraweekphysical-risk

• Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. (2021) Guidance on scenario analysis for non-financial companies.

• Thallinger, G. (2025) Climate, risk, insurance: The future of capitalism. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/climate-risk-insurance-future-capitalismg%C3%BCnther-thallinger-smw5f/

• United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (“UNFCCC”). (2015) The Paris Agreement. Available at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-parisagreement

• UNFCCC. (2023) Guidance for measuring greenhouse gas emissions for purchased goods and services for the apparel and footwear industry. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Guidance%20for%20Measuring%20Gree nhouse%20Gas%20Emissions%20Scope%203%20PG%26S.pdf

• Wiley. (2024) Geopolitical dynamics and carbon strategy. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bse.3486

• World Business Council for Sustainable Development (“WBCSD”). (2023) Pathfinder framework. Available at: https://www.wbcsd.org

• World Economic Forum. (2023) The “no-excuse” opportunities to tackle Scope 3 emissions in manufacturing and value chains. Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_NoExcuse%E2%80%9D_Opportunities_to_Tackle_Scope_3_Emissions_in_Manufacturing_a nd_Value_Chains_2023.pdf

• World Economic Forum. (2023) Climate change is costing the world $16 million per hour. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/10/climate-loss-and-damage-cost16-million-per-hour/