ART vs. Alzheimer ’ s

By DENISE CARVALHO

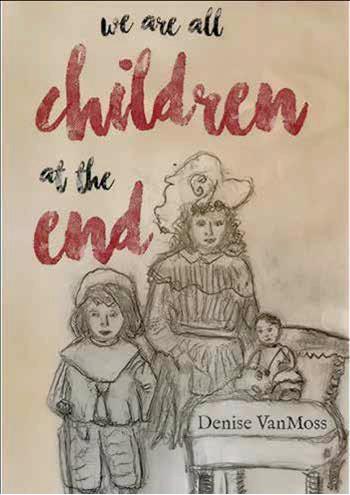

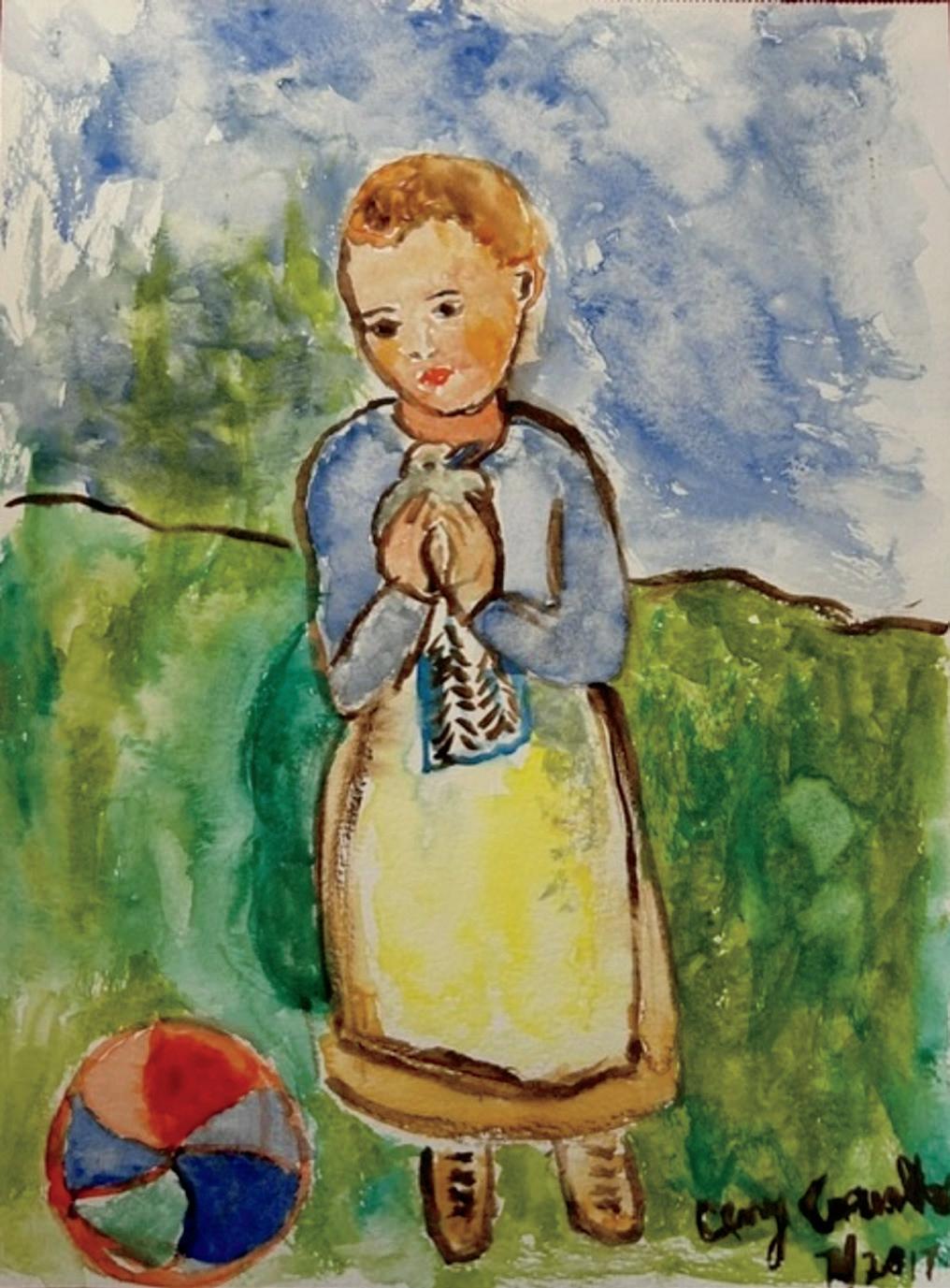

The following story is excerpted from WE ARE ALL CHILDREN AT THE END, a book which covers the author’s experiences with her mother Ceny who in the last few years of her life began suffering with Alzheimer’s. During these last years, learning how to draw and paint could be said that greatly expanded her time here on earth by giving her hope and beauty.

Maybe any of us would think that the opportunity to experience life through one's freedom of expression, or through the right to earn a living in anything one believes in or feels good at, or even being strong and determined to win against impossible odds, or facing life with courage and resilience despite the fact that no one believed you, maybe all of that wouldn't be enough to fight against this numbing of oneself, this predator of hope, turning hope into becoming zero.

you can no longer drive, as you have been diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s.” She didn’t believe him but was forced to accept or at least pretended she agreed with him. The point was, she couldn’t forget she had given reasons for his ultimatum: crashing in a tunnel when she couldn’t remember where she was.

These are words one does not want to hear:

Tbe neurologist gave mother the ultimatum: “Ceny,

It was in Rio, around 2012 or 2013 when she crashed her car in a tunnel as she was wondering “where am I?” That led to a visit to her neurologist, and to various exams, leading to the diagnose and treatment. Strangely though, mom’s high blood pressure (which she had since she was in her 50s’) and incontinence (when she was in her early 80s) led to a series of exams showing an excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or Hydrocephalus. We, her children, were stunned, when we found out that she needed a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt. It seemed that it was not so unusual with patients with Alzheimer.’

Mom's life had been robbed from her in so many ways, perhaps, she thought she agreed with some of the many choices she never made.

One could say that Ceny had a good life. She was cared for, loved by many, guided by a few, never worked for a living although she wanted to, she played the piano to entertain her graundchildren, but hardly believed she had any talent. She also forgave others and never gave up on them. She always believed in God and trusted his will unconditionally. But she wanted to know herself, to know whether she could be somebody, though she accepted the love of her family, but feeling deeply unknown. Once she asked me on the phone from Brazil: "Why can't I remember who I am?" And I responded to her from thousands of miles away in the United States: "You are my mother, and you are a wonderful human being. Just feel who you are inside your heart."

Mom always wanted to earn her own money, having a career as a librarian or a teacher, but she wasn’t allowed, although she earned her diploma as a Librarian from the Military Academy. She also spoke French, Spanish, some English, besides being a gifted writer in her own native Portuguese.

Since Ceny became a mother at 18, a role which was assigned by a social tradition to her, she grounded herself through the structures contained within her marriage, motherhood, and home. Ceny saw herself through an objective optics regarding her daily chores, which

demanded a certain control and capacity to judge and choose. Yet, she kept selfless, patient, understanding, somewhat trapped in her submissive housewife practices and seldom feeling free in performing her sociable everyday life. Quiet, she had learned to be a listener rather than an influencer, aware of her inclusion amongst the women she grew up with, keeping herself groomed, tasteful, and someone whose appearance made her look distinct, yet humble.

I came to understand that I could help my mother via art and we began the process of making art

As mom didn’t believe in her artistic talents, I decided to teach her to draw first, and that was totally by intuition. While teaching art history at Bloomington University, I found a byzantine book of architecture, and although it looked difficult at first, I realized that every church or castle were clearly defined by repetivive geometric forms. I decided to teach Mom to copy these churches, but using a playful manner, almost trivializing the task, stating: “All you have to do is to copy the geometric forms, the rectangles of the buildings, the triangles of the roofs, the squares of the windows, etc. etc. etc.”

As an artist myself, I had discovered that the best way of developing one’s creative abilities is to follow one’s own path toward discovery, whether by intuition or by copying. By using the simple rules of copying something as simple as squares and rectangles, mom began to realize that she could do much more than what she first thought.

Before that, Mom had never studied art except in preschool. She had never seriously learned to draw or paint as an adult. A couple of times, she helped my aunt to color some of her decorative flowery designs on fabric. These works on fabric were so beautiful that I collected and tried showing them when I was directing Agartha Art Gallery, an online gallery owned by the British artist Rose Feller. My aunt had been a metal sculptor and later began learning how to paint on fabric. But Mom accepted the impositions of her generation, without ever considering if she had any talent.

In fact, one day, when Mom and aunt Necy were still kids in primary school, Ceny had done her first drawing for an art class and was so proud of it. She came running to show her sister, excited, wanting her to be the first one to see it. It wasn’t a tree house, but a house on top of a tree. It would be great to see this work now, but it was probably trashed or left behind.

But seeing my mother’s abilities to challenge what was the norm, I could perceive her as a genuine artist. Through her art, one can state that Ceny was beyond the obvious expectations of her generation. She was probably a conceptual artist in her own right but didn’t know it.

When Necy (her sister) saw the tree over a house, she coulnd’t stop laughing, thinking how completely incongruous it was. She even showed it to her school buddy next to her and both exploded in laughter.

The young Ceny felt deeply embarrassed, but swallowed it with a smile, as she had done it many times. Yet, that sorrow, that rejection, was still there. She didn’t say a word. She seemed to have realized how that thought discouraged her. Yet, her smile was there, frozen, unaware of itself.That day in school, she realized she had no artistic talent. A light dimmed in her eyes. “She told me that my drawing didn’t make any sense,” without a shred of emotion.

Aunt Necy expected her to draw a house like eveyone else would have done it. But Ceny’s house was so much more creative, so avant-garde that no one could understand it. If she was born in Matisse’s or Picasso’s household, she would have been seen as a child prodigy. I wish she still had that drawing.

Back to her geriatric age, Ceny used to practice the piano two or three days a week, but lately, she couldn’t keep up, feeling lost reading the score, something she couldn’t have anticipated. It felt like emptying the past by letting go. Perhaps she was too young when she realized her own lack, aware that she could never surpass or even equate to her mother’s prodigious talent as a concert violinist and accomplished pianist even as a child.

Yet, Ceny was never envious of her mother’s talents. Instead, she deeply and sincerely admired her mom's amazing accomplishments, always encouraging her to play the piano, having the entire family completely silent watching her recital at home, as that was something seen in the theater. Before she married, Ceny's mom Nice (like the French city, Nice), had to let go of her career as a concert violinist after Juarez (her future husband at the time) expressed his jealousy to her fans begging her to let go. He was concerned that her career would destroy everything, her role as a wife and their love for each other.

“Strangers to Our Bodies” (p. 207)

When Mom first came from Brazil, unfortunately, she slipped in the shower and broke her hip. I held Mom’s legs slowly down and out of the SUV, placing her feet on the ground.We were both petrified that she would fall again; I vigilantly coached her every step; her eyes so fixated on the ground she couldn’t see the door. Her fear was contrasted by my obsession with detail, our perceptions so close and so far, like lines that could never meet.

After my mom was discharged from the hospital, I took over doing her rehabilitation at home as we had no more financial means to pay for any more medical support. In front of the dresser, staring at the mirror, we began our daily workout.

I counted, “One, Ceny Myriam Gomes de Carvalho; two, Ceny Myriam Gomes de Carvalho; three... Keep it up,” running back and forth from the kitchen as I was preparing the food. Lying down in bed, Mom continued the exercise, slowly turning her foot around one at a time. Then, she slightly raised each of her legs ten times, with a folded towel under the upper part of the left leg. Finally, she tried to move her legs sideways, the most difficult and painful of the exercises. We counted together. Mom could hear my voice from the kitchen, as she repeated the numbers with me, her voice stronger. Counting together gave her rhythm; it worked like a metronome, giving her purpose and a sense of time. Working five days a week, the exercises made her stronger. Being fit reminded her of her own diligence a few years earlier in Brazil, a time when she practiced Tai Chi at the beach. She was already in her early 80s then.”

“The two sisters were best of friends, together for more than eighty years for thick and thin, witnessing their own experiences as a film, sitting on the first row.”

Her mind was not always there. Mom stared at me expressing confusion when she was about to begin her exercises. “Who are you?” she asked. “Are you my teacher or my daughter?” “I am both,” I answered surprised. Anything I did revealed Mom’s confusion about who was performing those tasks. At breakfast the next morning, she asked again when the teacher would come back, fascinated, I suppose, with the teacher’s decisiveness and forceful nature. For mom, the teacher and I were opposites. When I came back from work in the evening, she greeted me with a kiss as mother to daughter. Then at six p.m., the usual time for the physiotherapy, she opened a big smile and welcomed the teacher. A few hours later, with calmer eyes, she kissed me goodnight.

“Alone at Home” (p. 213-215)

Mom understood how privilege could be lost. Privilege was not just money, but freedom of moving your limbs freely, coming and going as you please, even if it was to follow your daily routine. For me, it was the freedom to choose who to be, and what way of life spoke deeper within me.

For mom was a different story. Being in the now, allowed her to make choices of what to contemplate, whether a breakfast on Skype with her sister who lived in Brazil, or to daydream while waiting for me to return from work. She thought about days gone by, and how she was as a young adult. She wanted to do so many things, and to do them well. She wanted to be proficient in French and English, believing that she would be free to express it, but she never imagined herself working. Deep down she never earned that freedom to work. She translated a research paper from French to English for me. But now, it wasn’t her dictating her actions, but Alzheimer’s erasing her fluency. Even before Alzheimer’s, many times she mixed her children’s names, but now she couldn’t even remember them, lost wondering who they were.

“Ceny, are you listening?” Necy asked on Skype. “Cenyyyyy???”

“Yes,” struggling to make a simple ‘yah’ heard. “What?” insisting, “I can hear.”

Finally sound came out of her mouth. Slowing down to make each word clear to her, “NOW YOU ARE BECOMING AN AMERICAN... SO... you have to speak English.”

Every word took a lot of repetition, but neither Necy, nor Diche (my nickname as a child) wanted her to give up. The feeling was that her brain didn’t let her push further. Or she was so down to have lost everything that she was giving up. It was a huge effort from Ceny to respond, almost as her brain cells weighed tons. No matter what, she opened a smile when I reminded her of how ‘titia’, as I called Aunt Necy, enjoyed teasing her. “She has always been your most avid teaser and supporter,” humorously. Her eyes glittered, and she smiled. She knew I meant it.

“ The two sisters were best of friends, together for more than eighty years for thick and thin, witnessing their own experiences as a film, sitting on the first row. Holding each other’s hands, both sisters had gone through so much — love and marriage, raising their children, the insurmountable loss of loved ones. How could time become other than history? Mom loved Necy maybe even more than her own children. But their idiosyncrasies didn’t change over time. Necy’s teasing tendencies made her see life lighter, humor holding her to this earth; mom’s timidity allowed her to deepen her spirituality, distilling the love she learned from her parents like the finest wine.

Now as Mom was recovering in my place in Bloominghton, her lonely eighty-eight-year-old sister always left a strong impression, with her presence lingering hours after they exited the internet. Mom and Aunt Necy had always been close. In the last decades, they had kept a two-hand diary that was never written, their daily phone conversations, sharing even the most uninteresting details of their routines. Now that both had reached old age, they were suddenly separated by thousands of miles. Even when Mom was in the hospital, skype was the great invention that enabled them to prove they were hanging in there. At home, they ate together on Skype, Mom showing off her morning blueberries or lunch’s yummy yogurts, the latter she previously disliked, but it was worth it to stir a bit of envy into her sister.

The two sisters had their names invented. Necy was Nice (their mother) backwards, and Mom was Necy backwards. Their identities might have been defined by their own reversal as a strategy of acceptance of their differences. Their physical appearances were also very distinct. Mom had dark hair and brown eyes, while Necy had blond hair and green eyes. While Necy was vain and flirtatious, Mom was shy and innocent. Her introverted temperament was a target for being put on the spot by Necy, but without malice. Mom’s naivete was some-what encouraged or teased by family members picking on everyone’s typical features as a form of humor. Being laughed at was friendly conflated with laughing with, and everyone’s uniqueness was perceived as an original trait neither to be proud nor shameful.” (pgs. 215 and 216)

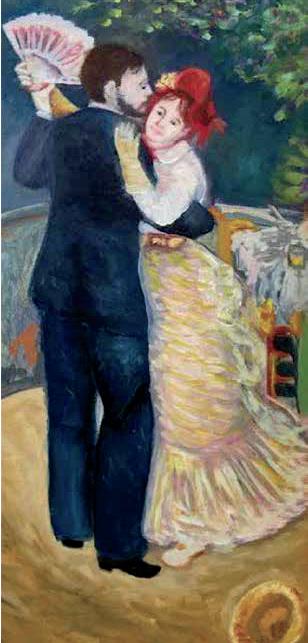

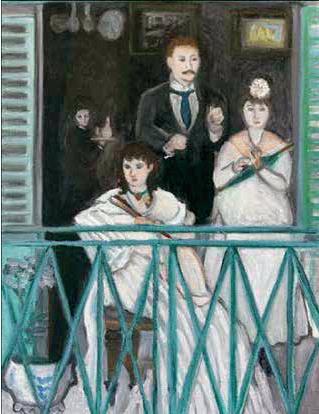

The couple dancing is one of the paintings Mom copied from a book of Renoir’s works, including this series of paintings titled Dance at Bougival, Dance in the Country and Dance in the City, painted between 1883 and 1919.

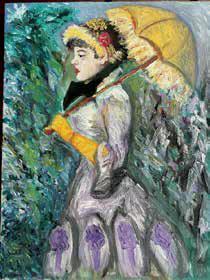

Mom also copied Renoir’s painting titled Woman Holding a Fan. I was so impressed with mom’s painting as it looks almost exactly as Renoir's. It seems that she caught the aura of this woman’s face. Her eyes and teeth showed through her slightly opened lips is so realistic to the point that it captures the aura of the original piece by Renoir.

This makes me think that or she was extremely talented and never found out, or this ability to copy almost precisely is an ability that many people with autism also have. Perhaps, could be possible that my mother was able to focus on much greater depth due to her complete isolation within her thoughts, which here also shows as an aspect of her survival determination, despite her own complete disconnect from other aspects of reality.

I also noticed that many of the early modernists made copies of other artists’ paintings. So, copying amongst artists was a manner of learning and yet redefining one's own perception of the object of interest, and perhaps complimenting the achievement of the first artist by reentering the path to that specific painting.

Excerpts from the chapter “Finding a Method” (p. 243-249)

“Mom’s memory was a mixture of fragments of the past, dreams, visions or words that she saw or heard in her mind, ghosts as guests, and in some moments, there were rare but funny and preplexing moments of acute clarity.

Before I began teaching mom to draw, I wanted to exercise her moments of clarity by trying something simple: asking her to correct a multiple-choice test my students have taken a couple of days before. She only had to find if the questions were right or wrong according to the exam key. After half an hour staring at the exam sheet, Mom could not apply herself to match the key to the student’s answer. I realized she needed a different approach than a logical one to apply more mechanical tasks.

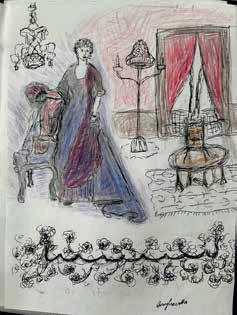

On the following days, I continued to research what could stimulate or enhance her logical capacity. One afternoon, flipping the pages of a catalogue with photographs of French Rococo furniture, I noticed how the high quality of the images made the furniture’s contours and texture appear so clear, so precise. The sumptuous lines of the Louis XV chair provided a simple but complex experiment. My eyes were glued to its details. They reminded me and Mom of Grandma Nice.

Grandma Nice used to love Louis XV furniture. She loved it so much that she needed to have one, or two, in her home. The thought that it was probably a museum collectible had not been contemplated. She consulted with her son, the Benedictine Monk who had lived in Rome and spent five years in the Vatican writing his doctoral dissertation in theology. She knew he knew all about Gothic and Rococo architecture, art, and even furniture. They had talked about how much she admired Rococo design, the elegance, the dreamy and sweeping buoyancy.

For Grandma, and now for Mom, it was not vanity, but memory. Grandma Nice had Louis XV furniture in her parents’ home, when she was a baby. That baby sat on the Rococo chair seen on the cover of the book, We are All Children at the End. Next to Nice was her eldest sister, Edmée, dressed in a long puff sleeve organza dress with a rubbled collar beautifully embroidered with pearls and wearing shiny boots and white gloves. Her hair was red and curly and on her head was a large Victorian hat. Her brother stood with long linen shorts and white collar over a navy sailor long sleeve boy shirt,also wearing a hat, boots, and a Victorian era cane for his three and a half feet size. The baby, Nice, sat calmly with a serious look on her face, dressed more simply in a baby dress with ribbon ties on top of her tiny shoulders.

Now Mom delved deep down in her own restrained self, probing, examining, calm, withdrawn, trying not to show how anxious she felt attempting to draw this photo. But I could see through her, and she slightly smiled a Mona Lisa smile. To draw this chair will be mom’s task, I thought with great expectation almost as if I had found the cure for Alzheimer’s.

Indeed, copying seems quite mechanical, but copying something challenging can be enthralling, as it makes us aware of the shifting in the perception of the object, giving an experience of cocreation. Initiation or mimesis had been claimed by the ancient philosopher Aristotle to be part of the human capacity to apprehend, and the beginning of creativity. The history of painting shows that the emulating nature enables humans to first wonder by perceiving its apparently unpredictable method. Imitation then was not creating a mirror image of the original but entering an in-between experience of perceiving and creating. If any extraordinary copy would rather become another matrix, then we have reached the ability to create.

As if each line was a filament of a path followed by her eyes, I wanted my mom to see up and personal the walking details of each of these filaments and then realize the forms that they made. I wanted Mom to forget what object it was, its name and what function it had, to think of it as fragments of a puzzle. Although consciousness is not a puzzle, the thrill engaging with an object is that it takes us to understand it little by little.

Mom began her first drawing, then her second, third, and so on. Copying from an art history magazine of Rococo furniture, amongs other styles. Mom was copying and redefining chairs, lamps, chandeliers, tables, armoires, and even a couple of women dressed “dreamy” Victorian Era gowns became her most desirable subject matter. She could see her mother or sister in them, and each day drawing had become an opportunity to find someone from her past.

Mom improved quite a bit from her broken femur, and from an infection that almost killed her. When we finally returned from Indiana, USA, back to my home in the Poconos, Pennsylvania, Mom was in great shape. For that reason, she decided to visit her sister and children in Brazil, as she wanted to bring them some of her paintings as gifts from her most recent passion for the arts. So, she traveled by plane alone but completely guided in what to do during her trip. I spoke with the airline's airtraffic controller, making sure that she would have assistance during the flight. My younger brother was going to pick her up at the airport, and she would be brought to him on a wheelchair, just to avoid another accident. After a month in Rio, she finally returned to the United States, now with her American Green Card.

After celebrating her return with a few good laughs, Mom and I dedicated the next couple of weekends to start a new body of work. Since she had donated several works to her family and friends in Brazil, her stack of paintings had diminished, as she generously donated several of her pieces to friends and family, she now needed to get back into production. I was her guiding source, while she acknowledged her responsibility through her painterly tasks, as I also had to travel to New Jersey to teach. At one moment, Mom owned the full praise of her painting’s accomplishment, at another she’d admire it but had trouble remembering that she did it. I couldn’t trust mom’s cognition about her own improvement, so I decided to assume that she must be getting better, since she wasn’t getting worse.

After celebrating her return with a few good laughs, Mom and I dedicated the next couple of weekends to starting a new body of work.

The art process was not scientific enough to provide a clear evaluation of cognitive success. Artists who were at the edge of insanity could be geniuses in capturing great lucidity in their own reality. Other artists borrowed from the mentally insane to make their own artwork, such as the Art Brut of Jean Dubuffet. A famous Brazilian modernist, Ivan Serpa, not only painted portraits of the mentally disabled, but also organized exhibitions with works made by them. Reason and art would stand on opposite stances as an artist’s profusely subjective vision defined the prerogatives of the piece. How viewers saw it could define if it was art at all, as in Gabriel Orozco’s Empty Shoebox, dismissed, or kicked by visitors as expected, when entering one of the main galleries of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The completion of an artwork was another issue. Most artists considered their pieces finished when they decided they were finished, which concluded it was impossible to determine whether an artwork was ever completed. Obliquely, the history of art was based on the judgment artists and viewers shared of the work’s successful completion. Contradictorily, unfinished works could also be considered beautiful and successful. And what was thought as Unfinished would work as being subsumed as finished.

Leonardo’s Mona Lisa exemplified a real woman whose soul could not be perfectly captured by the artist, and he continued to develop the work further, until someone else decided the work was completed. Nonetheless, the painting was considered the quintessential female image of the Italian Renaissance as its iconic standard of beauty passed on to the next generations.

“Between a Probable Impossible and An Impossible Probable”

(p. 250-255)

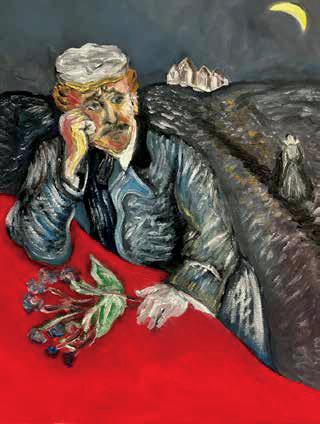

Mom discovered the local shades of green and mixed them with the yellows and ochre tones of the landscapes of van Gogh in the South of France. I told her that in the twentieth century color composed the language of expression and purity redefined the logics of any method. By building an allusive structure of color juxtaposing color, in two hands, we focused on the linear development of major works of art. I told Mom about the importance of

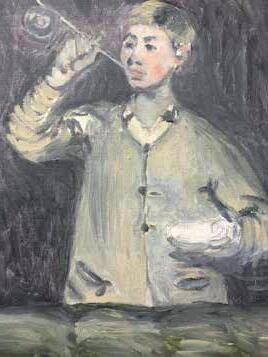

virtuoso precision in artworks of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Then we tried to meticulously copy Jean-Baptiste Greuze's Child Asleep on His Book, aware we could never reach his genius on punctilios detail. Not in our wildest dreams could we become the old masters or even their forgers. Mom laughed with joy as she noticed the unprecedented possibilities that were unfolding, yet aware of her shortcomings. For her to become an artist was to have a new life, not succumbing to her own forgetfulness, not being forgotten by others, turning into an immortal. Perhaps, only a dream. We both laughed. Then we worked on copying Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun's happy self-portrait, inspired by the early writings of the Enlightenment. She was a court painter celebrated by her numerous portraits of the French aristocracy. She made thirty portraits of Marie Antoinette, the last one with her children, known as being a propaganda painting in pleas of the Queen as a mother, before she was sentenced for treason and death by decapitation. In a period when only men vied to become court painters, Vigée-Lebrun was a painter and a privileged woman. Even today, women artists were still relegated to less visibility and access than their male counterparts. But privilege still determines whether a woman can shatter the unseen and, apparently unbreakable, glass ceiling.

Painting could be a gift to that spiritual strength, even if unexpected. The universe presented the situation; it defined its donor and its receiver. No self- or other inter-

est, no world systems orchestrating or financing it. The gift of painting could only happen in the present tense, without promises, without expectations. It was more important than fame and fortune. It was about hope, health, joy, surprise, and persistence. It was also about finding beauty. Mom used to think of beauty as someone’s beautiful face or a crispy and clear day of spring. But now, beauty was much more. It was the incomprehensibility of shape in an illusively field of time and space, colors changing in front of her eyes; an expression she didn’t know she had in her to create it.

One morning, she surprised me with a drawing of the blue sky. She said, “it is so beautiful, so blue.” Blue was now both beauty and color in an entire sheet of paper, made with a color blue pencil, with a few green shades alluding to the trees, and lines promising an airplane flying in the open sky. I showed her a book with paintings by Monet and said that the impressionists captured color in a similar fashion. It was about capturing, as if you were manifesting it as matter from the fleeting perception of your sight. Capturing color was making it hers.

I realized that I was not the one teaching Mom, but it was she who was teaching me. Mom stood totally static and almost breathless observing my brushstrokes, altering her initial sketch on the canvas. She followed along my expectations, or better frustrations, with changes on her own breathing pattern, surprising me when she noticed the same inconsistencies and shortcomings in the paintings as I, thinking I had more knowledge, was wrestling to find. As an artist I could go on forever seeking a resolution for the challenges in my work. Both excited and anxious, I kept going in search of the perfect stroke, of the ultimate shape that rendered the work its feeling of completion. But it was like a continuous labyrinth of tortuous dead ends, like life itself. I finally told mom, we had to leave the painting unfinished, waiting for it to dry a bit so we could continue our tour de force.

For mom, the vision of beauty and the wonder of art was far more valuable than the things to be produced or consumed. It was unprecedented for her, unknown and profound, which could transform her humble but bold chance-taking into a palpable skill, her beginner’s cultural vision into a higher grasp of universal mystery. Her art functioned to expand her own personal desire, and as I saw it, to make her more proactive in her own ability to crush the reactive tendencies of her illness. She didn’t grasp that, but her loss of memory and of her own identity put her in the perfect position to find the unpredictable. What could be better than that for someone who had given up on her perception of the world?

Our next paintings became more complex, as portraits of Renoir and Picasso generated richer palettes and new metaphors to the human portrait. The modernists allowed much more freedom than the more classical portraitists. Mom could finally begin a canvas totally on her own, still afraid but daring, aware that in painting some traces could be accidents. She still thought of family members as she began copying the artists’ works but then arrived at a new place where these painted figures became something new. They could be more dignified, less sad, or with different body features, as we noticed that through our mistakes we could create new possibilities, new references, new memories. The portrait of a Spanish woman with her shawl and fan became her best oil painting so far. As we continued to paint, we studied what in the works were awareness of the artists’ experiences. In Picasso’s original work, how the model was sitting in his studio, the walls behind the woman which contained sketched lines, accidental and intentional were left as part of the work. We noticed that the wavy shades of gray on the wall created a silhouetted shadow of the woman’s body, as Picasso might have intended to redefine the objective detail of the room by playing with the possibility of the unexpected. Mom was impressed with the ability to rethink what was seen with what was imagined. I asked her to add something new to her work.

She created a lamp with a lobster’s foot, pushing the bar further along her imaginary.

Intrigued by how I was capturing her, mom decided to paint me. She depicted me as a byzantine icon, with a halo over my head. I told her I wasn’t a saint. “I don’t even know if I still can paint. Painting is a gift, and sometimes you can’t find it again.” Mom didn’t listen. Instead, I insisted I would help her to paint my portrait. For me to paint myself was very difficult. I didn’t want to use the mirror, although it wouldn't be too easy copying my own image, and it probably wouldn’t help Mom or me to discover what we knew about each other. Memory image, I thought, is known as a primal art language used in the Paleolithic Age. Helping my mother to make my portrait, I sought my own features through lines, colors, lights and shades. I was determined that whatever I knew about myself was misinformation, assimilated traces of seeing, not being. I wanted to deconstruct myself as a finding in the making. As I was helping Mom to paint my portrait, both she and I cried when we suddenly recognized me as a younger girl, long before I’ve left home to live in a foreign country. We were both the only ones who could recognize me as a young woman in the painting.

Mom’s portrait would have to follow a similar approach, a memory image that could lead to a primal understanding of who she was. It started quite predictable, as I copied what I saw, from the part where an assimilated

image dictated the composite of forms. Then, I allowed more flexibility, more flow, letting my eyes depict more than the obvious, trying to grasp the real person, returning to something archaeological, primal of mom’s face.

After I saw the exhibition Unfinished at the MET in 2016, I realized how Mom’s Portrait had something to add to the idea of an unfinished painting.

Just a note about these thoughts added here, that when I began to write this book, I had decided to create various forms of claiming the characters, sometimes shifting from one character to another, or experimenting with the narrator as taking over various voices of the characters as if intentionally suggesting a multiplicity of personas sharing identities in the book.

In these two chapters of the book, the distinction between my experience as an artist and professor of art history and my mother’s beginning with a process she had never studied or experimented herself is expressed. My first realization from mom is that she could not do anything that once was based on memory and practice, such as playing the piano or peeling a potato. Maybe it is interesting to consider the difference from playing the piano (which she never thought of herself great at, perhaps by comparison to her mother) and making a painting. But under this challenge, Mom seems to have awakened a new ability to overcome her own limitations by taking a new approach to painting through her imagination. She decided to copy from a very old photograph from her mother as a baby, with her aunt and uncle also as children.

For Mom, to paint was the renewal of some form of private language. By observing her interest awakening, I began revisiting her own memories of painting. I started making mom’s portrait, as I wanted to test how much I could capture about my own mother. I studied her eyes, searching for knowledge beyond judgement. I didn’t want to see the logics of her features, but to capture the complexity and contradictions of her being the concern, the frailty, the despair, the melancholy, the hope that escaped without her knowledge. I wanted to find a new energy and the freedom to express it all over again.

Author's Note:

I would like to acknowledge the works of the great masters that my mother, Ceny, had the opportunity to be inspired, transforming her own experience. This is an Alzheimer’s patient's interpretation.