FOR WHICH IT STANDS…

JANUARY 23 – JULY 25, 2026

Published by

Fairfield University Art Museum

1073 N. Benson Rd.

Fairfield, CT 06824

www.fairfield.edu/museum

Copyright © 2026

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or information retrieval system, without permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025951545

ISBN: 979-8-218-89480-1

The publication of For Which It Stands… was made possible in part by a generous grant from Connecticut Humanities.

Carey Mack Weber, Executive Director, Exhibition Curator

Michelle DiMarzo, Curator of Education and Academic Engagement, Copy Editor

Megan Paqua, Registrar, Manager of Rights and Reproductions

Edmund Ross, Senior Designer, Designer

Susan Cipollaro, Senior Associate Director, Media and Public Relations

Kiersten Bjork, Associate Director, Integrated Marketing & Communications, Copy Editor

I ntrodu C t I on

For Which It Stands… was created to be an integral part of the nationwide conversations and commemorations surrounding the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in July 2026. Bringing together more than 70 works by a diverse group of artists, in a wide array of media, the exhibition traces the image of the American flag in art from World War I to the present. Across more than a century of history, the artworks on view both document and protest, celebrate and critique, offering a complex visual record of the nation’s triumphs and struggles.

The exhibition title comes from the Pledge of Allegiance, first written in 1892: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Since its standardization in 1912, the flag has served as one of the most powerful symbols available to artists. It has appeared in nearly every medium invoked to affirm national identity, but also to challenge it.

This project is also personal. I grew up in Concord, Mass., where each April the “shot heard round the world” is commemorated on Patriots’ Day. As a teenager in 1975, I witnessed the Bicentennial celebrations that began there, experiences that shaped my sense of history and civic identity. With this exhibition, I wanted to mark the Semiquincentennial in a meaningful way for both the Museum and the University: by presenting artworks that use our most enduring national symbol to question, to commemorate, and to engage.

When I began developing this exhibition five years ago, I could not have anticipated the turbulence of our current moment. My goal, however, has remained constant: to create an exhibition that fosters civic engagement through art—highlighting artists whose work invites us to confront the complexity of our past, acknowledge present challenges, and imagine future possibilities. As the artists here reimagine the flag, they reveal not only our shared victories but also the injustices that demand reckoning.

The installation unfolds across both of the Museum’s special exhibition spaces in a loose chronology. The Bellarmine Hall Galleries present works from ca. 1918–1990, beginning with Childe Hassam and N.C. Wyeth’s flag imagery from World War I, and Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photograph from the end of World War II at Iwo Jima. By the 1960s, Pop Art and social protest dominated, including Jasper Johns’ groundbreaking Flag I (1960), which subverted the national emblem by flattening and distorting its familiar form. Faith Ringgold’s 1970 The People’s Flag Show Poster—created to promote an exhibition that tested the limits of laws against flag desecration—represents the heightened symbolism of the flag for artists in the era of Civil Rights and Vietnam War protests. The Bicentennial and the space race further underscore the ways in which the flag has been marshaled as a marker of national pride.

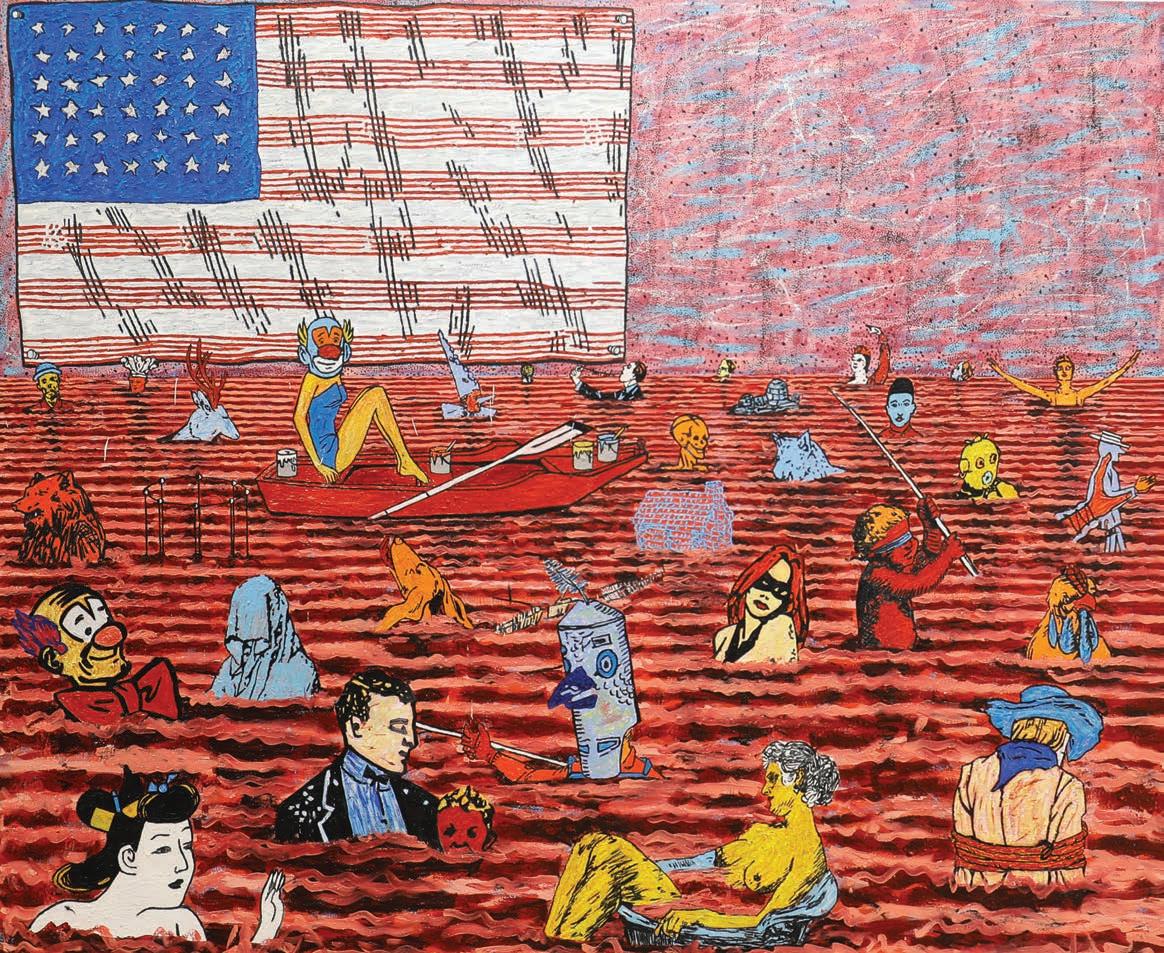

In the Walsh Gallery, visitors encounter more recent works (1990–2025) where artists address urgent issues of social justice, from police violence and gun violence to Black Lives Matter and Indigenous rights. The Museum has commissioned a major new work for this exhibition: Maria de Los Angeles’ monumental textile sculpture Freedom Is Not Free?, which stands over seven feet tall, interrogating migration, belonging, and citizenship from the perspective of a formerly undocumented immigrant. Other contemporary artists take celebratory or contemplative approaches to the flag, underscoring the range of meanings it continues to carry.

As James Baldwin wrote in his 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son: “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Baldwin’s insistence that love of country demands honest critique reflects the very tension embodied in the artworks gathered here—between patriotism and protest, belonging and exclusion. In a 1963 speech, Baldwin returned to this theme when he observed: “It comes as a great shock…to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance…has not pledged allegiance to you.” Spoken in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, his words capture the disillusionment of those for whom America’s promises of equality remained unfulfilled. Taken together, Baldwin’s insights help to illuminate the central question posed by the artworks brought together in For Which It Stands…: can we love this country, take pride in its ideals, and still confront its failures with honesty? The artworks on view suggest that we can—and that the enduring image of the flag provides us with a uniquely charged symbol that can be used for both celebration and critique.

~ Carey Mack Weber Exhibition Curator

Frank and Clara Meditz Executive Director

A

P rom I se A nd t H e PA r A dox

American higher education is the embodiment of American exceptionalism. From the founding of Harvard College in 1635 to the founding of Fairfield University in 1942 to today, our higher education institutions have been central to the American project. Our nation’s extraordinary history and example is in no small part a product of the breadth and depth of our remarkable model for higher education.

It is with this Tocquevillian ethos in mind, that we are most excited to be hosting a series of events and exhibitions in conjunction with our country’s semiquincentennial, America250: The Promise and Paradox.

The cornerstone of this offering is the exhibition we share here: For Which It Stands…. This thoughtfully crafted exhibition examines depictions of the American flag over the past century—from patriotic to politically charged.

A painting which stands as the representation of both is Childe Hassam’s Italian Day, May 1918 (cat. 1, opp. page). I was blessed to see this painting as a returning college freshman at my home museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in August of 1988 as part of the exhibition The Flag Paintings of Childe Hassam and have kept the catalogue ever since. As the curator and author of that volume, Ilene Susan Fort, notes, this is the only flag painting to depict an airplane, a modern—but in the context of the first world war also a daunting—marvel. Hassam’s paintings speak to us as they call us to both celebrate and examine with a nuanced and layered complexity.

Far beyond a singular painting, each work in this exhibition stands on its own, but just as importantly they stand as a collective, reflecting a spirit of inquiry and rigor and asking us to engage thoughtfully with the American experiment. Thus, we host this exhibition as not simply a museum, but as a university—a university whose societal role in our American context is to ensure public ideas and public discourse are essential. For as I have written previously, “if the university comes to be broadly perceived as simply a vested interest inhibiting the consideration of reform, rather than as an agenda-setting institution, its unique societal position—its relevance—is lost.”

Fairfield University’s relevance stems not just from our commitment to free inquiry, but from our over 500-year Jesuit, Catholic educational tradition which embraces the centrality of the arts in our shared endeavor of advancing human flourishing and seeking wisdom in support of dignity of every individual and the greater good—or as our motto states, Per Fidem ad Plenam Veritatem —Through Faith to the Fullness of Truth.

And in this spirit, we welcome you both to this exhibition and our university, an institution which is blessed to be a model of the modern Jesuit, Catholic, American university embracing the duality of our context and the bright promise of our future.

~ Mark R. Nemec, PhD President, Fairfield University Professor of Politics

A mer ICA n C A nvA s : tH e F l A g , A rt, A nd C ontested m e A n I ng I n u. s . Pol I t IC s

It’s easy to think the U.S. flag is the least ambiguous symbol in American politics. It stands for America! But as the Fairfield University Art Museum’s semiquincentennial exhibition For Which It Stands… shows, the flag’s meaning is anything but static. It is constantly open to interpretation, re-interpretation, and contestation. We all understand the flag stands for America, but what America stands for . . . that’s a different question.

This brief essay will give you some tools for understanding what the flag “means.” These may be somewhat technical terms for feelings you already have. Put differently: a lot of what I’m going to tell you, you already know—even if you can’t quite put it into words. My goal is to give you names and concepts, drawn from the political science literature, to contextualize why the flag makes you feel a certain way. As we go, I will highlight a selection of items on display in For Which It Stands... Regrettably, I don’t have the space to mention all of the wonderful artworks you can see in the Museum’s galleries during your visit. Instead, I invite you to take the following brief discussion and apply it to your experience in the exhibition.

A Brief Primer on National Attachment

People want to feel like they are part of something bigger than themselves. Although there are many such groups (families, religions, etc.), I want to talk about nation states—or what Benedict Anderson calls “imagined communities.” These aren’t fictional relationships, but they are abstract. After all, none of us can ever know all our fellow citizens individually. All forms of national attachment are effectuated by political symbols, the rituals attached to those icons, and the beliefs associated with them. The United States has many such symbols: the Constitution, the Founders, Lady Liberty, and—of course—the U.S. flag.

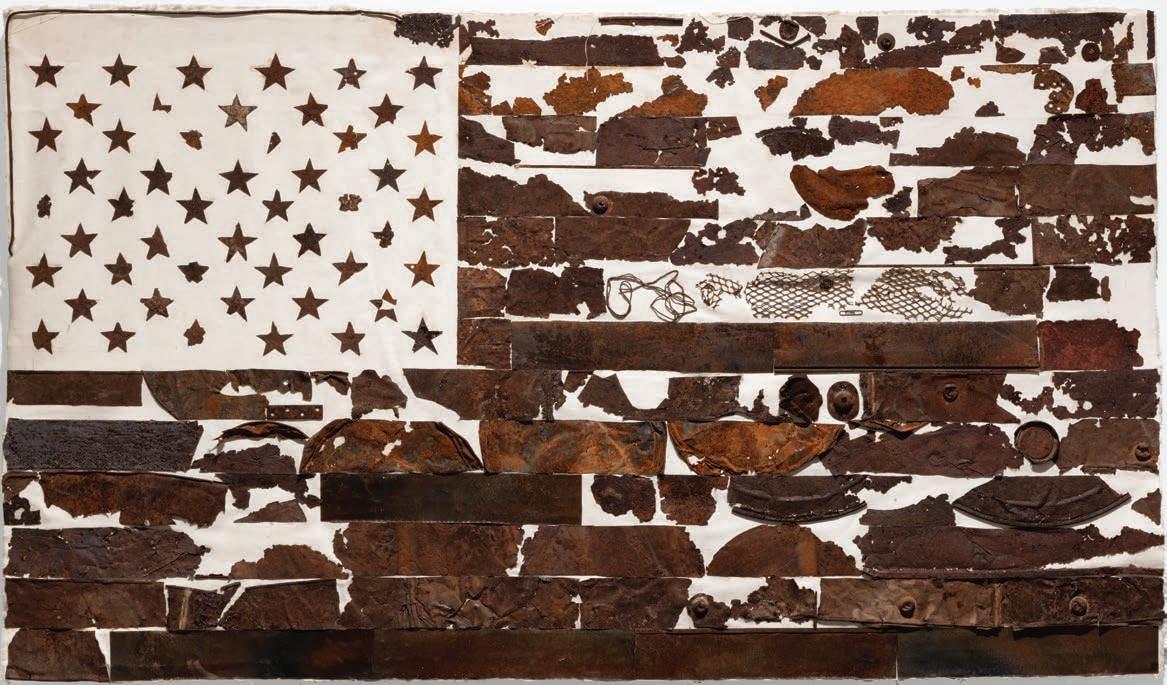

But not all forms of national attachment are created equal. Some are desirable, others less so. In diverse, liberal democracies like the United States, national attachment is good when it makes room for contestation and bad when it doesn’t. Scholars tend to associate the former (good) with patriotism, and the latter (bad) with nationalism. Patriotism implies a deep love for one’s country, but a willingness to dissent when criticism is necessary. Nationalism, by contrast, asserts that one’s nation is superior to all others. This makes it intolerant of dissent, demanding uncritical loyalty. To understand the distinction between nationalism and patriotism in action, consider Carl Schurz’s famed quotation: “My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right, if wrong, to be set right.” The first half of the quotation (the famous part) is nationalism: it implies a blind loyalty to one’s nation, regardless of merit; the second half (arguably Schurz’s point) is patriotism: anyone who loves their nation must be willing to criticize it, when necessary. As I will demonstrate, you can see both patriotism and nationalism in the United States. But before I do, it is necessary to address a second question: who or what determines the form our national attachment takes?

There are two basic sources for national identity: the first comes from above, the second from below. For the most part, the Top-Down variety (associated with the political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who called it “Civil Religion”) is the purview of the State. It is the State that establishes the ideal form of national attachment. This variety prioritizes national unity, cohesion, and legitimating state institutions. I should also be clear: Top-Down national attachment originates with the State, but everyday citizens often buy into and reproduce it. By contrast, a Bottom-Up approach (which we associate with the Father of Sociology, Émile Durkheim) embraces cultural symbols like the flag as the product of social interpretation. If the State establishes what a flag “is,” then We The People are the ones who establish what it “means.” This may mean parroting the State’s official version, but not always. The Bottom-Up approach is inherently more democratic: while some

people may view the flag in ways consistent with State preferences, others do not. Whether protestors or artists, everyday Americans imbue the flag with meaning the State wouldn’t necessarily approve of.

These four concepts—nationalism v. patriotism, and Top-Down v. Bottom-Up—can help us consider how the flag is presented in For Which It Stands… Does an exhibit encourage or discourage criticism? What about inclusivity? Is it representing the United States as a geographic entity, form of government, or set of abstract principles? Who is speaking? Is it the State, or is it the people?

The “Sacred” Flag v. Free Speech

The flag is the ultimate avatar of the U.S. government, its population, and the nation’s higher ideals. You can see it fulfilling this duty throughout the exhibition: for instance, Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945) [cat. 10, below left], or Keith Mayerson’s First Men on the Moon (2012) [cat. 18, below right]. These works don’t portray individuals operating in their personal capacities, but rather existing as extensions of the State. Because the flag is perhaps the indispensable signifier of the State, the State’s agents—at both the state and national levels—have attempted to codify its appearance and regulate its usage.

These flag desecration laws have varied over time. Initially, they (1) came from the states, not the national government; and (2) weren’t intended to prevent political misuse of the flag, but rather its commercial abuse.1 In Halter v. Nebraska (1907), the Supreme Court upheld a state law preventing such uses because they threatened to denigrate the flag in the public’s

1 For much of the following state-level jurisprudence, I am indebted to Albert Rosenblatt’s analysis. Albert M. Rosenblatt, “Flag Desecration Statutes: History and Analysis,” Washington University Law Quarterly 1972, no. 2 (1972): 2.

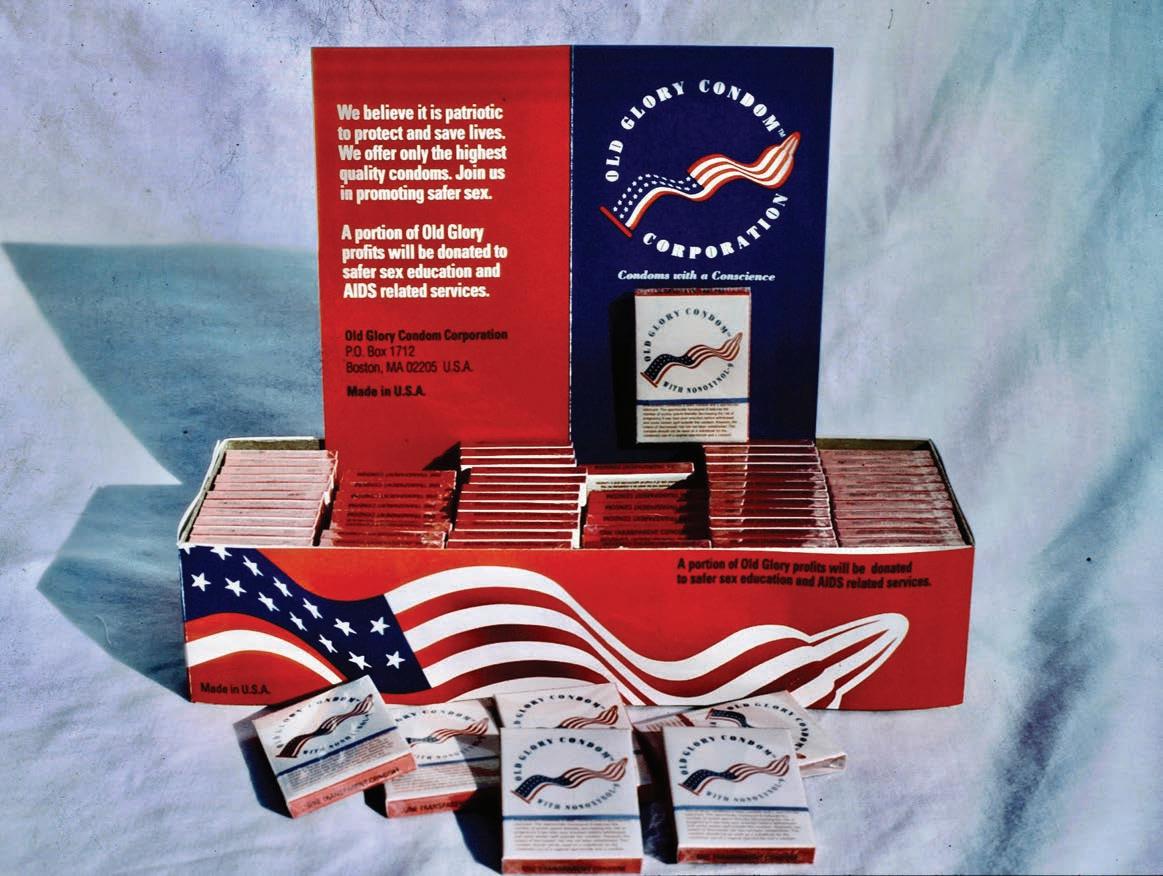

estimation. (Although the imagery used on the Old Glory Condoms created by Jay Critchley in 1990 (cat. 71, pg. 40) came out decades after the Court shifted away from this interpretation, they arguably embody the “disparaging” uses at issue in Halter.) Notably absent from Halter, however, was attention to individuals’ First Amendment right to free expression. This logic didn’t emerge until World Wars I and II, when states—fearing dissent would threaten the war effort—amended the laws to address speech. In 1942 Congress joined the states in protecting the flag by passing the Flag Code (4 U.S. Code Chapter 1). This is the Code you are likely familiar with: it prescribes certain behaviors (e.g., saluting the flag and pledging allegiance), and proscribes others (e.g., burning it outside of ceremonial disposal, allowing it to touch the ground, or hanging it upside down unless in distress). Although it’s largely advisory, Congress formalized these recommendations via the Flag Protection Act (1968). The result was that, for a brief time, the flag enjoyed significant state and federal protections.

But this period was short-lived. Starting in 1969, the Supreme Court began handing down a series of decisions declaring desecration laws unconstitutional. In Street v. New York (1969), the Court overturned the conviction of a man who verbally disparaged the flag; in Smith v. Goguen (1974), the justices declared unconstitutional a Massachusetts law that criminalized treating the flag with “contempt” (in this case, sewing it onto the seat of one’s pants); and in Spence v. Washington (1974), the Court overturned the conviction of a man who had taped a peace sign over the flag (violating the state’s prohibition of superimposing another symbol atop it). But the big case came in Texas v. Johnson (1989), when the Supreme Court ruled that Gregory Lee Johnson was exercising his First Amendment right to free speech when he burned a flag in protest of the Reagan Administration’s policies. In short, they found that any law criminalizing conduct merely because of the ideas it expresses violates the Constitution. Later that year, Congress amended the Flag Protection Act to bring it in line with the Court’s decision– but to no avail. In United States v. Eichman (1990), the Supreme Court determined the new Flag Protection Act suffered from the same flaws as the previous iteration.

This debate over desecration laws demonstrates the ongoing tension between Top-Down and Bottom-Up interpretations of the flag. The Johnson decision makes clear which interpretation the Court backs. As Justice Brennan wrote for the Majority:

If we were to hold that a State may forbid flag burning whenever it is likely to endanger the flag’s symbolic role [e.g., in protest], but allow it wherever burning a flag promotes that role [e.g., ceremonial retirement] . . . we would be saying that when it comes to impairing the flag’s physical integrity, the flag may be used as a symbol . . . only in one direction.

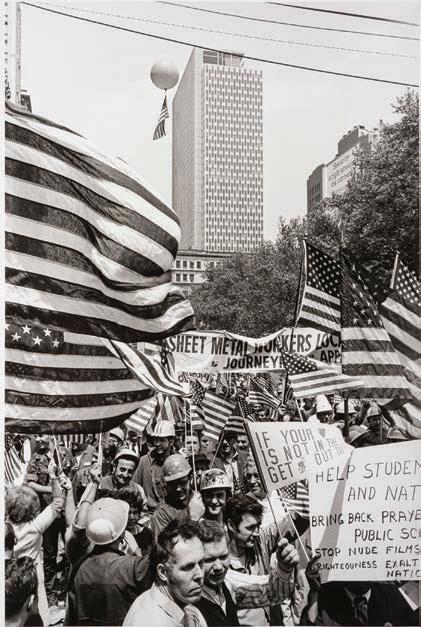

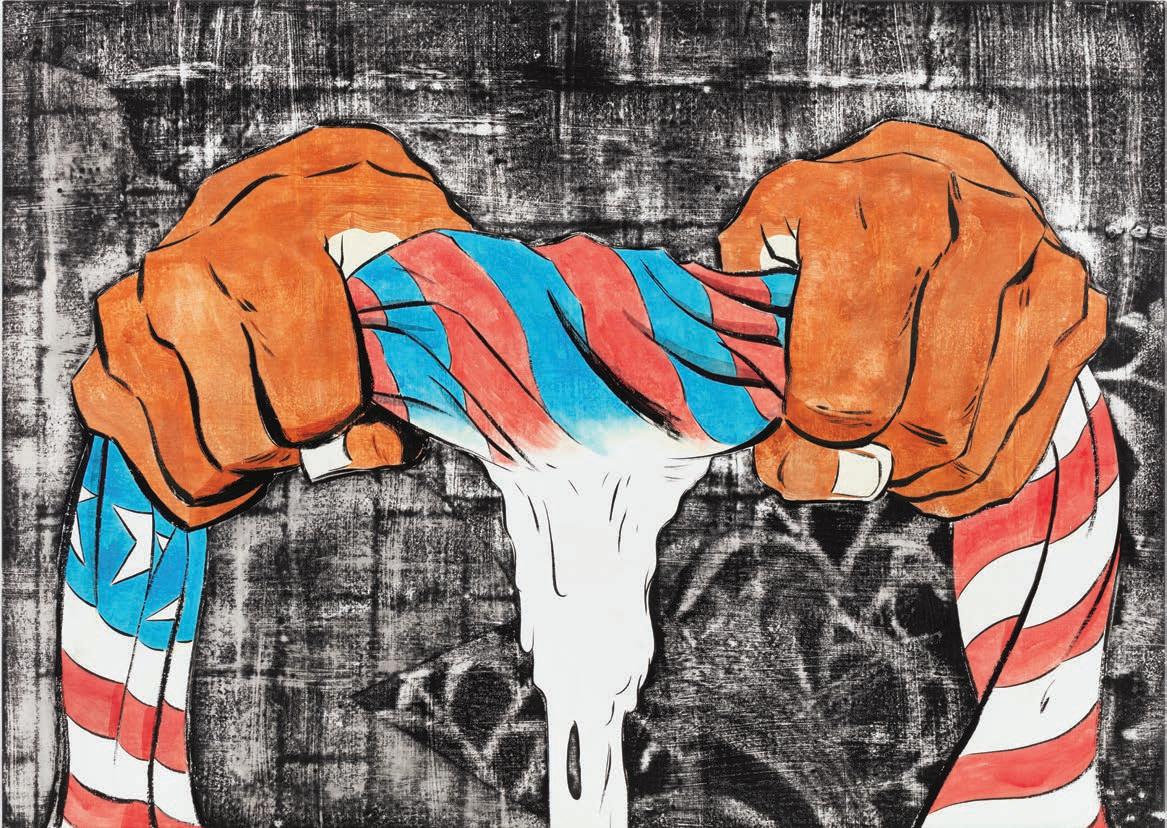

Beyond protecting so-called “respectful” engagement with the flag (e.g., the pro-Vietnam War protestors photographed in Leonard Freed’s Hard Hat Cat. 23

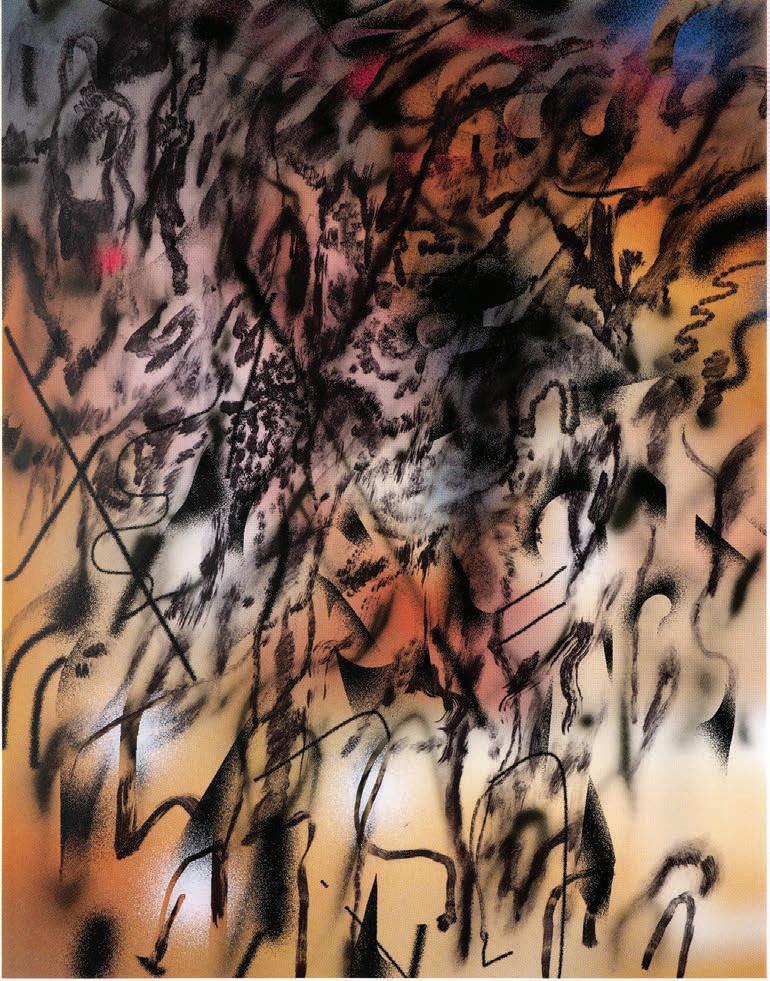

Rally (1970) [cat. 23, opp. page], these Court decisions signaled a commitment to a broad range of political expression some could find unpalatable. Some of these offenses may seem mild today: for instance, the protestors in Larry Fink’s Vietnam Demonstrations (1967) [cat. 24, below], who are captured engaging with the flag in ways Flag Code proponents would find distasteful (e.g., holding it “flat or horizontally” and allowing it to “touch anything beneath it”). Then there are the more obvious violations: both Glenn Ligon’s photograph of a crumpled flag in a wash bucket (cat. 61) and Dread Scott’s Emancipation Proclamation (2020) [cat. 60, right] violate the physical integrity of the flag in precisely the ways that Johnson protects. I would even add to this list James Rosenquist’s Mirrored Flag (1971) [cat. 16]. Although not explicitly political, it presents the flag mirrored in two senses: once as actual reflective material, but a second time as an inverted Union. Given the controversy that surrounded planting the flag on the moon (the U.N. Treaty on Outer Space prohibits lunar territorial claims), the inclusion of an upside-down flag is pregnant with meaning.

Flag desecration laws are always topical. Should sewing the flag into a shirt be prohibited? It violates the spirit of the U.S. Flag Code, to be sure. Yet the problem is that offense, by its nature, is subjective. What I find distasteful may be benign to you. Many of those who called for the Yippie Abbie Hoffman’s prosecution after he wore the flag as a shirt seemed unperturbed when General Richard Meyers did exactly the same thing. It is in this context that Donald Trump’s August 2025 executive order to prosecute flag burning must be read. To be clear: the executive order does not criminalize flag burning. Instead, it relies upon the “imminent lawless action” test the Court established in Brandenburg v. Ohio (i.e., speech that can reasonably be expected to lead directly to criminal activity is unprotected). The implication is that while burning the flag in theory is permissible, this speech can be prosecuted if it can be tied to illegal activity. The executive order directs the Attorney General to prosecute such violations. The problem, of course, is that the AG has prosecutorial discretion when pursuing charges. The danger is that, just as with Abbie Hoffman and Richard Meyer above, one’s point of view of “offensive” may lead to an uneven—even targeted—application of the law.

The Flag as Reservoir of Meaning

The flag’s potency as a symbol extends beyond the “Official” or State-issue flag. How many times have you seen something that looks like a flag—but isn’t—that

nonetheless inspires intense emotions? Because the State cannot control meaning, protestors and activists are free to interpret and reinterpret the Stars and Stripes as they see fit. The result is an array of politically potent (and constitutionally protected) speech.

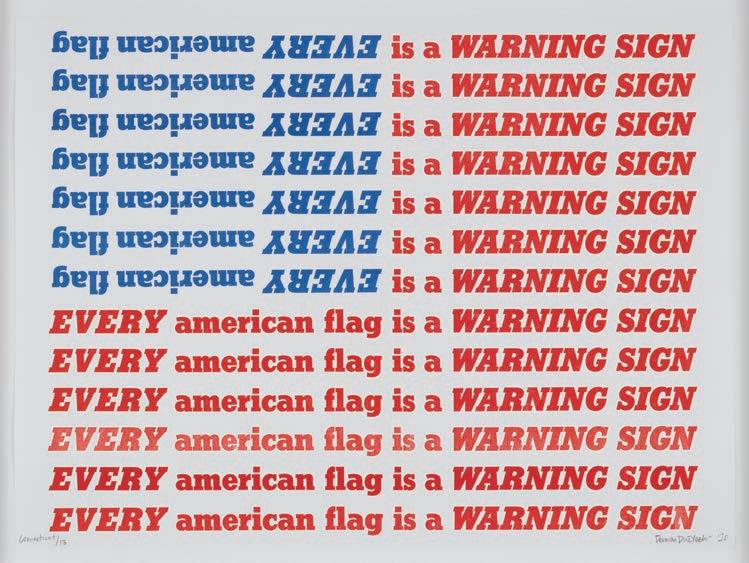

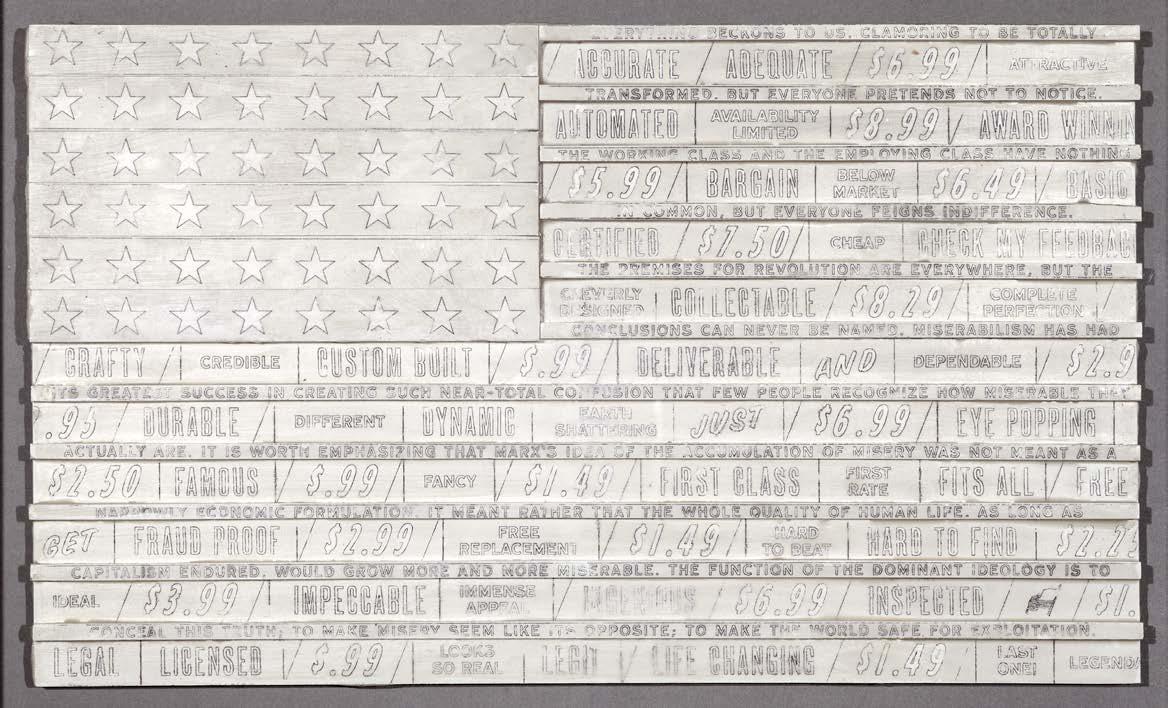

Sometimes these alterations are small. David Hammons’s African American Flag (1990) [cat. 39] preserves the size and dimensions of the traditional flag, but replaces the colors. Instead of the traditional Red, White, and Blue he uses Red, Black, and Green, colors inspired by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Society. The flag captures both the centrality and marginality of African Americans in the U.S. experiment. Another example of a modified official flag is Sara Rahbar’s I don’t trust you anymore, Flag #59 (2019) [cat. 43, left], which criticizes U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East by superimposing military and ammunitions belts atop an American flag. Alterations can also be more considerable. Danielle Scott’s False Flag (2020) [cat. 41, opp. page] is an indictment of U.S. race relations: it uses shotgun shells instead of stars and prints images of lynchings across the white stripes. Then there is Deborah Nehmad’s old glory? (2017) [cat. 73, pg. 45], which constructs a flag out of 33,000 stitches (one for every gun death per year), including markers for suicides (x’s) and homicides (crosshairs). And just because a picture is worth a thousand words doesn’t mean artists won’t find meaningful ways to incorporate text. The indigenous artist Demian DinéYazhi’ creates a flag by repeating the phrase “EVERY American flag is a WARNING SIGN” in red and blue (cat. 63, pg. 17); and William N. Copley’s contribution to the 1967 Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Viet Nam (cat. 25), replaces the stars in the canton with the word: THINK.

Are these U.S. flags? They certainly don’t do what the Top-Down flag is supposed to do. They don’t project unity or respect for institutions; rather, they highlight differences of opinion and critique the status quo. But as we said earlier, this is the mark of patriotism: the willingness to voice unpopular opinions with the goal of correcting political and social injustices. These Bottom-Up flags represent the generational attempt to help the United States realize its unfulfilled promises.

E Pluribus Unum? Race, Borders, and U.S. National Identity

The flag is an avatar of the American people. But how do these people see themselves? Nationalists and patriots will disagree. The former likely have restricted definitions, focusing upon either race or religious affiliation (an orientation legal scholars call jus sanguinis, or “right of blood”). The latter, on the other hand, have more open definitions that don’t tie citizenship to parentage but rather to where one is born (called jus soli, or “right of soil”). One has a place in a vibrant and multicultural democracy, the other does not.

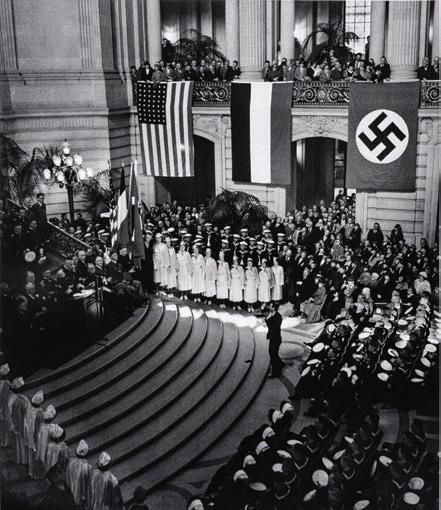

Consider America’s ongoing and tragic struggles against racism. Although there are not many instances of purely nationalistic sentiment in For Which It Stands… , its excesses and evils are never far away. Sometimes it’s out in the open, as with John Gutmann’s photograph of a Nazi rally at the San Francisco City Hall that placed the U.S. flag alongside the Swastika (cat. 6, opp. page). The message is unmistakable: U.S. citizenship is open to Whites only. Generations of Americans have been forced to push back against this bigotry. There are the everyday citizens, like the SNCC workers pictured waving an American flag in Danny Lyon’s 1963 photograph outside the funerals of victims of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombings (cat. 27, opp. page). Or there are the artists using the tension between what the flag should stand for and what it does stand for. I actually use Stanley Joseph Forman’s Soiling of Old Glory (1976) [cat. 33, opp. page] in my “Intro to American Politics” class every year. The photograph, which went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, captures the moment a White protestor threatens to impale an African American man with a flagpole. These examples only scratch the surface. Throughout the exhibition, you will find citizens and artists seeking to reclaim the flag from the original sin of slavery.

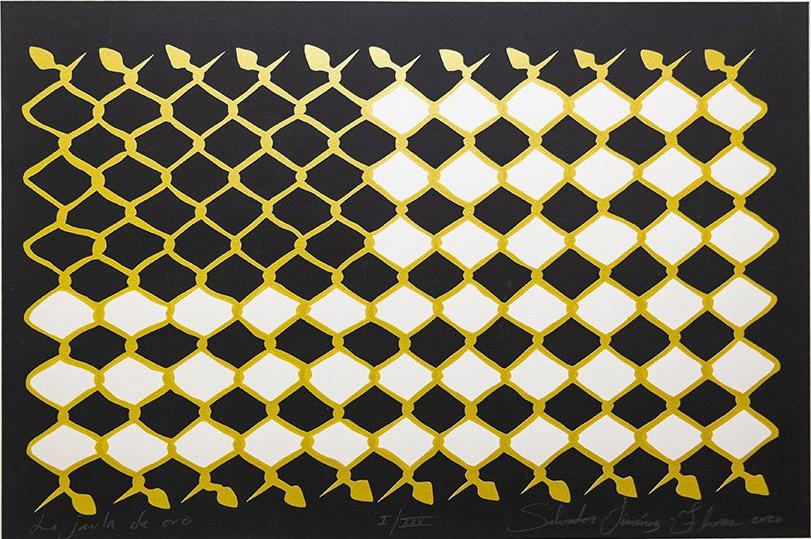

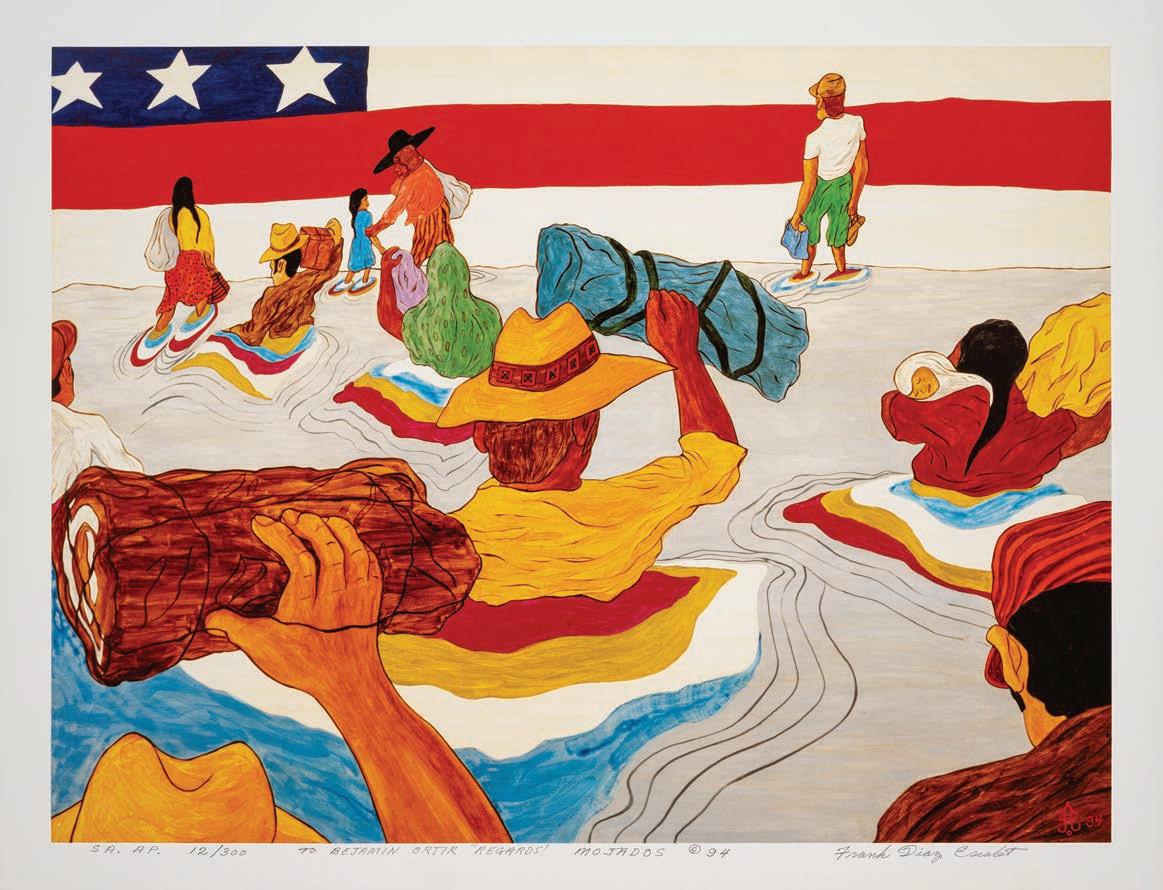

Who gets to be an American? Who is accepted as us and who is rejected as them? National identity is constructed out of borders that are both metaphysical as well as material. Consider Frank Diaz Escalet’s Mojados (1994) [cat. 54, pg. 42], which represents the border as the U.S. flag. The image appears optimistic: immigrants—many with children—fording a river, seeking a new life in the United States. For many, however, the U.S. border isn’t a gateway but rather a prison. Salvador Jiménez-Flores’s La Jaula de Oro (The Golden Cage) [cat. 53, p. 41] presents the American flag as a chain-link fence. This Bottom-Up flag juxtaposes the promise of the American Dream alongside the reality of border cages. Yet the beauty of the flag as a stand-in for U.S. borders is that it doesn’t just limit membership—it can extend it, as well. James Prosek’s Invisible Boundaries (2021) [cat. 55, pg. 19] replaces the Union stars with a bald eagle and integrates the silhouettes of indigenous American wildlife. It is a reminder that membership in the U.S. imagined community needn’t be limited to merely human life.

Concluding Thoughts

Throughout this brief essay, I have tried to give you some tools for understanding what the flag means to you. We have discussed how its meaning is, to some extent, determined by our political leaders and laws (Top-Down); and that, in a vibrant democracy, disagreements will naturally lead to alternative approaches (Bottom-Up). We have also illustrated the differences between a patriotic national attachment and a nationalistic one. I hope the examples we covered have been helpful in illustrating these differences.

I’ll end this essay with a brief discussion of one last piece that I think sums up For Which It Stands… Maria de Los Angeles’ contribution (cat. 72, pg. 20) is a microcosm of our discussion: an artist literally sewing herself into the American story. Her work combines iconography from her Mexican heritage alongside U.S. symbols. But this work isn’t just about her: you have the ability to contribute to it. I encourage you to join one of her workshops, where you will exercise your constitutional right to generate your own flag (whether or not it’s inspired by the U.S. flag is up to you) for inclusion into de Los Angeles’ sculpture. And as the United States gets ready to turn 250, I can’t think of a better way to celebrate than engaging with what Faith Ringgold beautifully called The People’s Flag.

~ Aaron Q. Weinstein, PhD Assistant Professor of Politics, Fairfield University Faculty Liaison to the Exhibition

tH e A mer ICA

n F l A g : For WHA t d oes I t s tA nd?

Flags originally served as a rallying point in warfare, and it’s interesting that at an early date it was discovered that having a flag carrier who had no weapons, whose sole function was to hold a flag, served a useful military role. We can trace this practice back to the Eagle standards that rallied the Roman legions, and then forward a few thousand years to the national flags that marshalled troops at Austerlitz, Leipzig, and Waterloo. From this sort of practical function, a country’s flag developed a larger symbolic function as a rallying point for the crowds who gather at ceremonies and parades, or even as a symbolic rallying point for a nation at large. Flags became something to proudly display in shops and homes, over entrances to homes and on barn doors, and to add a touch of nobility and glamor to daily life.

The American flag is an unusual one. Most national flags are symmetrical or feature a central motif such as a lion or an eagle or the rising sun of Japan. The American flag has a little blue rectangle on the upper left that is off center, and it is unusually busy in its design, with its 13 alternating red and white stripes and the rectangle crowded with a constellation of white stars.

There are symbolic reasons for this which we tend to forget, for the American flag was adopted when America had not yet achieved independence from England, and ten years before the Constitution of the United States was ratified. When the American flag was adopted in 1777, the United States was not yet united but was a loose confederation of independent states, closer in character to the common market that exists in Europe today than to a unified country.

Even after the Constitution was adopted, it took many years for the federal government to exert any sort of control over this disorderly confederation, and to establish the powers necessary to raise taxes, build an army and navy, and establish national laws that applied to the whole terrain. One of the curious characteristics of the American flag, as well, is that while most national flags are fixed, the American flag keeps changing. Originally it had 13 stripes and 13 stars, one for each of the American colonies. As it developed it kept the 13 stripes but kept changing the number of stars, which at this point have reached 50, and someday may number even more.

In this regard, the changing form of the American flag serves as a sort of chronicle—a tabulation of the progress of America’s growth—as the nation expanded from a thin strip along the Eastern seaboard to a continental empire. Built into the American flag is the notion of continuous change and growth. It’s a celebration of progress—a notion that became a central element of American identity and an essential part of the American dream.

From an aesthetic standpoint, it seems to me that the American flag is very much open to criticism if we consider it as a flat design. But when it flutters in the wind such criticism seems beside the point. The profusion of stripes and stars creates a rich array of patterns that are constantly changing, like the changing patterns of a kaleidoscope. To view the American flag in the wind is a mesmerizing experience.

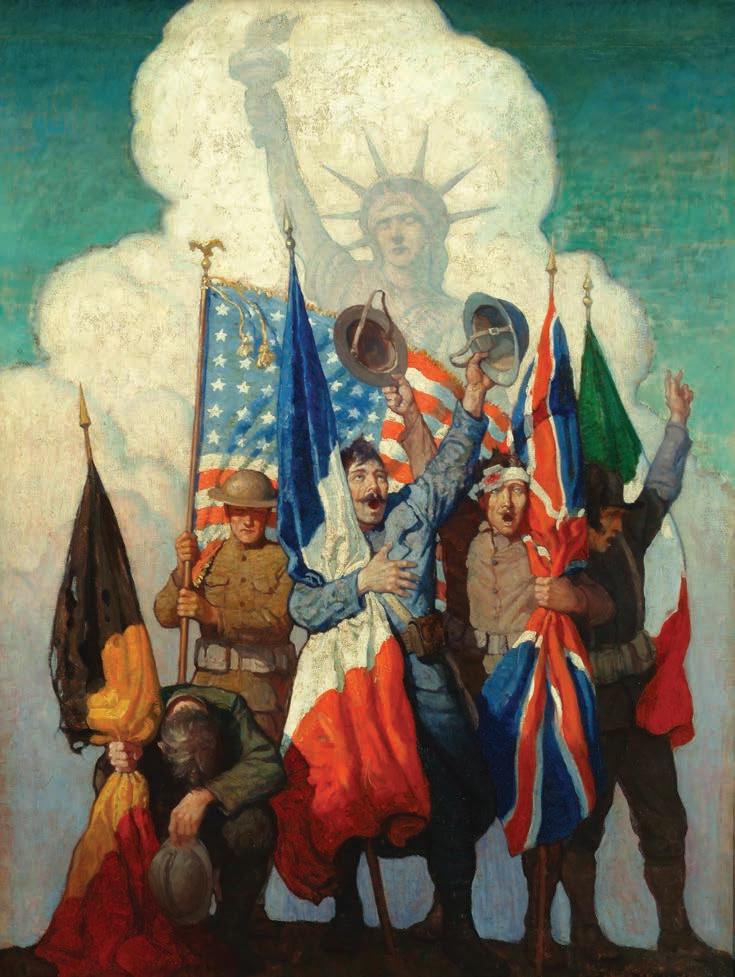

Some of the most remarkable paintings of the late 19 th century celebrate this fact, with an innocence that is hard to recapture today. Figures such as N. C. Wyeth (cat. 3, pg. 28) treated the American flag in a purely celebratory way, delighting in the parades and the pomp and pageantry that naturally formed around it. For figures such as Childe Hassam, the American flag became a near-abstract patch of color that gave life and color to a gray city street. Notably, for figures like these the American flag stood for deeper values as well. It stood for American values that were exceptional, that had a

sacred character, that had a sort of moral and religious holiness. For when the United States was formed it not only had an unusual flag but a form of government that was unusual in fundamental ways—a fact that we tend to forget today since this new form of government has since become rather standard.

Two of these ways stand out: First, at a time when most of the world lived under the sway of hereditary rulers, it was a democracy—a form of government that existed in some of the territories of ancient Greece, but had not been practiced for about two thousand years (outside of a few tiny city-states, such as the Republic of San Marino). Second, it was also a constitutional form of government, which is to say that it was based on a single written contract, rather than a haphazard collection of precedents. The role of men was to play by the rules rather than to make up the rules to bolster their own interests, and the underlying foundation for this form of governance was the democratic belief that all men should live free and that all men had equal rights under the law.

These two features gave American nationhood a somewhat peculiar character, since “Americanness” was not simply a matter of protecting American boundaries. It was the belief in the natural rights of all humankind, and it included the hope that eventually these rights would extend to the entire globe. In short, to an unusual degree, the American flag symbolized not only patriotism, but a commitment to an unusually demanding moral framework of equal rights for all.

No human society has ever quite attained this ideal, and from the moment of its founding, the United States was saddled with the uncomfortable paradox that many of those, such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson—who campaigned so earnestly for the cause of freedom and are widely revered as leading “founding fathers” of this country—were in fact slaveholders, seemingly oblivious in real life of the human rights they celebrated in their rhetoric. Winslow Homer’s painting Dressing for Carnival (1877, Metropolitan Museum of Art) for example, uses an American flag to drive this point home. It depicts a black man being costumed for the Jonkonnu festival—a celebration originating in the British West Indies, with roots in West African culture, that was adapted by enslaved people in the southern United States. Originally a Christmas day celebration, after the Civil War its forms and costumes were adopted for Fourth of July and Emancipation Day festivities. Homer’s painting emphasizes the very dark skin of the celebrants and the exotic nature of their costumes, but one of the children in the scene proudly displays an American flag. Surely the painting poses the question of whether these individuals, who had just been technically granted their freedom, would actually enjoy the same freedoms as those enjoyed by white people, or if they would be treated with repugnance, as sub-human outcasts.

For all its critical edge, Homer’s painting does not question the noble qualities associated with the flag itself. This did become a central theme in much of the imagery of the 1960s and 1970s, when episodes such as the brutal My Lai massacre of completely unarmed women and small children led many to question whether the war in Vietnam was serving the cause of human freedom or of dictatorial, totalitarian rule. During this period, the American flag was often deliberately burned and desecrated in protests, as well as flaunted in a mocking way by hippies and drug dealers.

Since that period, it seems that the American flag has never quite recovered its innocence. Plastered on cars, barns, and houses, it has come to carry implications that are rude and in-your-face rather than polite or high-minded. It seems to symbolize disdain for a pluralistic society, and an embrace of right-wing values. Strikingly, if you’re driving down the highway and spot a truly enormous American flag, it’s generally not one that serves to mark a school, a hospital, or an art museum,

but instead to advertise an auto dealer and to serve as a ploy to sell cars. The flag has become a symbol of divisiveness and shifty salesmanship rather than of the qualities of honor, diversity, variety, and multi-culturalism that it once celebrated— those invoked in the American shield’s motto, E Pluribus Unum —“Out of many, one.”

Its innocence sullied, it has become a tarnished symbol of the fractured society we live in today. Will it remain tarnished? Or can it serve again, as it did in Winslow Homer’s painting, as an invocation to do a better job of living up to our ideals?

~

Henry

Adams,

PhD Ruth Coulter Heede Professor of Art History, Case Western Reserve University

1. Childe Hassam (American, 1859-1935)

Italian Day, May 1918, 1918

Oil on canvas

36 x 26 inches

Art Bridges

2 . Florine Stettheimer (American, 1871-1944)

George Washington in New York, ca. 1932-1933

Oil and mixed media on canvas

60 x 49 7/8 inches

Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer

3 . N . C. Wyeth (American, 1882-1945)

The Victorious Allies, 1918

Cover of The Red Cross Magazine, May 1919

Oil on canvas

45 ¼ × 34 ¼ inches

Delaware Museum of Art, Gift of the Bank of Delaware, 1989

4. Ernest Lawson (American, 1873-1939)

Washington Bridge, New York City, ca. 1915-1925

Oil on canvas

25 ¼ x 30 ¼ inches

Delaware Museum of Art, Gift of the Friends of Art, 1964

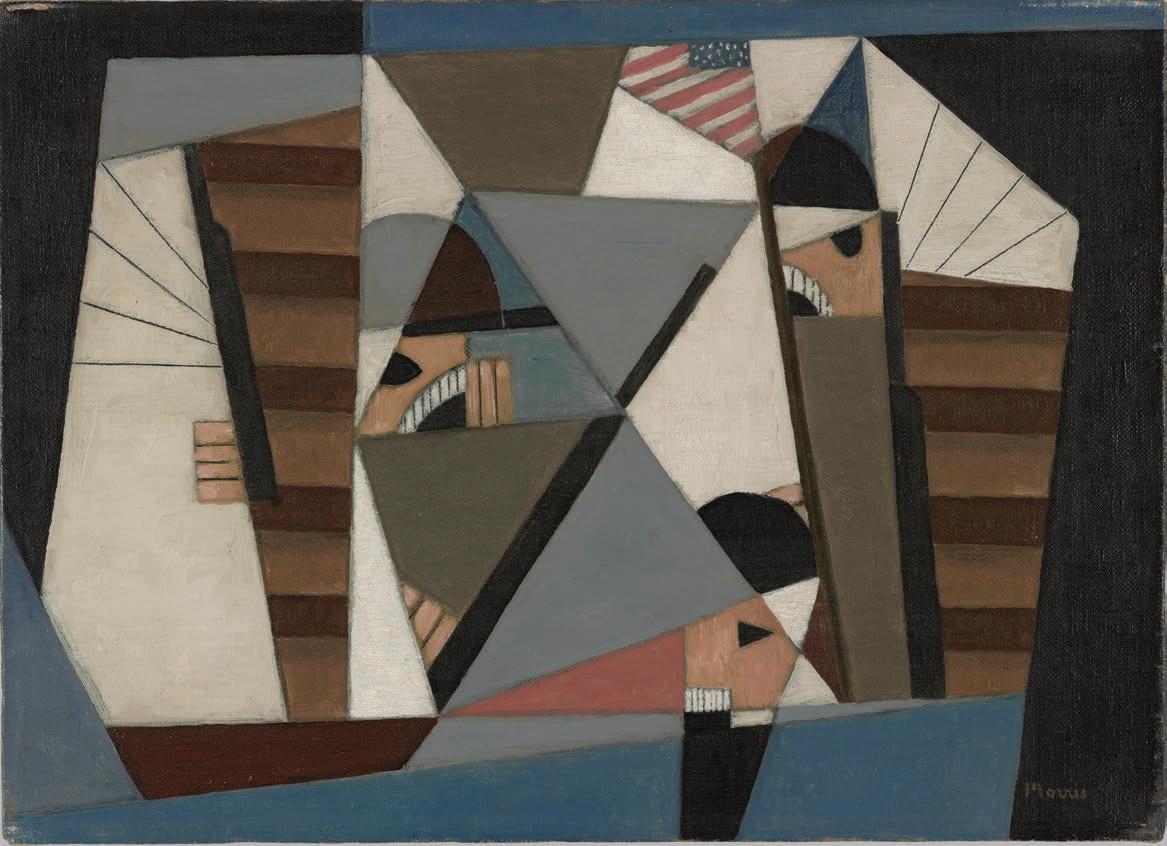

5. G eorge L. K. Morris (American, 1905-1975)

Invasion Barge, 1943

Oil on canvas

10 x 14 inches

Yale University Art Gallery, Purchased with The Iola S. Haverstick Fund for American Art in honor of Professor Alexander Nemerov, Ph.D. 1992

6 . John Gutmann (American, born Germany, 1905-1998)

The News Photographer, San Francisco City Hall, 1935

Gelatin silver print

14 x 11 inches

Private Collection, New York

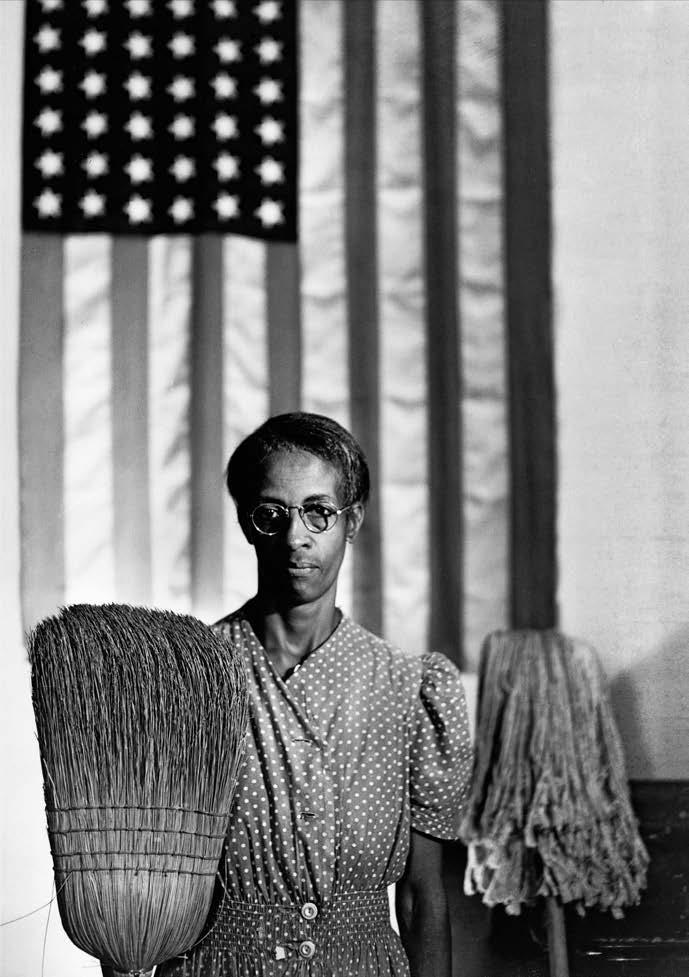

7. G ordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

American Gothic, Washington D.C., 1942

Gelatin silver print (exhibition print)

20 x 16 inches

Collection of the Gordon Parks Foundation

8. Herman Maril (American, 1908-1986)

Old Glory, 1943

Watercolor on paper

10 ½ x 14 inches

The Herman Maril Foundation, Courtesy of Debra Force Fine Art, New York

9. Barnaby Furnas (American, born 1973)

Untitled (Iwo Jima), 2000

Watercolor on paper

11 x 8 ¾ inches

Richard and Monica Segal

10. Joe Rosenthal (American, 1911-2006)

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, 1945

Gelatin silver print

9 7/16 x 7 11/16 inches

Lent by the Estate of Hanns & Patricia Kohl

11. Robert Lynn Lambdin (American, 1886-1981)

[Heroes of World War II], 1958

Oil on canvas

80 ¼ x 105 inches

Bridgeport Public Library Collections

12. Al Hirschfeld (American, 1903-2003)

Eisenhower’s Inauguration, After Covarrubias

Published in Vogue, February 1, 1953

Gouache on board

19 x 25 inches

Collection of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation

13. Faith Ringgold (American, 1930-2024)

The People’s Flag Show Poster, 1970

Offset lithograph

18 x 24 inches

Courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York

14. Paul Camacho (Puerto Rican, 1929-1989)

American Beauty, 1966

Oil on canvas

31 x 25 inches

Westport Public Art Collections

15. Jasper Johns (American, born 1930)

Flag I, 1960

Lithograph

Printed and published by ULAE, West Islip, New York

21 7/8 x 29 ¾ inches

Edition: 23, plus artist’s proofs

Susan Sheehan Gallery, New York

16. James Rosenquist (American, 1933-2017)

Mirrored Flag, from the Cold Light Suite (G.37), 1971

Color lithograph with mirrored-Mylar foil

Printed and published by Graphicstudio/ University of South Florida

29 x 22 3/8 inches

Edition: 70, plus artist’s proofs

Fairfield University Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 2024.29.01

17. Jane Hammond (American, born 1950)

Untitled (28, 157, 272, 179, 64, 95, 45, 244, 247, 109, 146, 185, 9, 234, 207), 1993

Oil on canvas with metal leaf

70 x 80 inches

Collection of the Orlando Museum of Art.

Purchased with funds provided by the Acquisition Trust

© Jane Hammond

18. Keith Mayerson (American, born 1966)

First Men on the Moon, 2012

Oil on linen

28 x 36 inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of Avo Samuelian and Hector Manuel Gonzalez, 2023, 2023.25.10

19. Audrey Flack (American, 1931-1924)

Fourth of July Still Life, from the Kent Bicentennial

Portfolio: Spirit of Independence, 1975

16-color screenprint with stencil, die-cutting, and lamination

Printed by Lorillard Co., published by Styria Studio

40 x 40 inches

Edition: 125, plus 10 artist’s proofs

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of Audrey Flack, 2023, 2023.29.01

20. Ming Smith (American, born 1947)

America Seen Through Stars and Stripes (New York), 1976

Archival pigment print

40 x 60 inches

Edition: 5, 1 artist’s proof

© Ming Smith. Courtesy of the artist and Nicola Vassell Gallery

21. Fritz Scholder (Luiseño and American, 1937-2005)

Bicentennial Indian, from the Kent Bicentennial Portfolio: Spirit of Independence, 1974

Color lithograph

22 ¼ × 29 ¾ inches

Printed by Lorillard Co., published by Styria Studio

Edition: 125

Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of the Lorillard Company

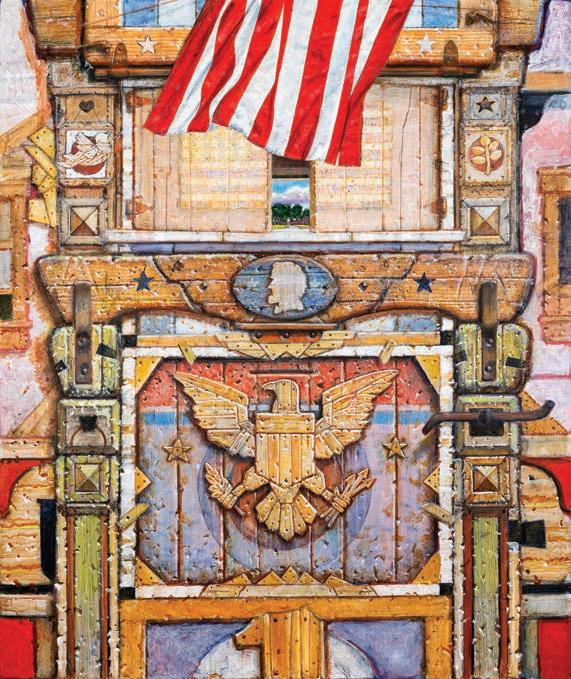

22. Fred Otnes (American, 1925-2015)

America: A Nostalgic View, 1975

Mixed media on wood

31 x 32 inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of the Robert K. Otnes Trust, in Memory of Fred Otnes, 2021, 2021.07.127

23. Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

Support America’s Policy in Vietnam. Hard Hat Rally in Downtown Manhattan, 1970

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 x 7 7/8 inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of anonymous benefactors, 2025, 2025.35.80

24. L arry Fink (American, 1941-2023)

Vietnam Demonstrations, photographed April 1967, printed 2019

Archival pigment print

12 7/8 x 19 1/16 inches

Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of Ron Sadi

25. William N. Copley (American, 1919-1996)

Untitled (Think/flag), part of the series Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Viet Nam, 1967

Screenprint

Printed by Chiron Press Inc., published by Artists and Writers Protest, Inc.

20 7/8 x 25 ¾ inches

Edition: 100

Courtesy of David Nolan Gallery

26. Artist unknown

Gather for Victory March: Marchers gather near the Capitol today for a demonstration calling for a military victory in Vietnam, Washington, D.C., October 3, 1970, 1970

Associated Press wire photo

9 ¾ x 6 inches

Private Collection, New York

27. Danny Lyon (American, born 1942)

SNCC workers stand outside the funeral: Emma Bell, Dorie Ladner, Dona Richards, Sam Shirah, and Doris Derby, Birmingham, 1963

Gelatin silver print, printed later 11 x 14 inches

Private Collection, New York

28. Adger Cowans (American, born 1936)

Mississippi, 1963

Gelatin silver print

14 x 11 inches

Courtesy of the artist

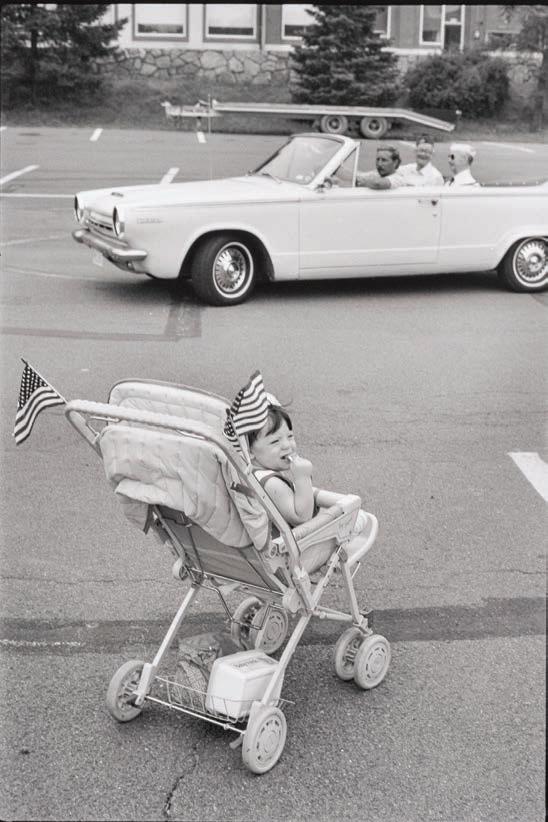

29. Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

A baby sits in a stroller adorned with American flags, 1989

Gelatin silver print

9 ¼ x 6 inches

Private Collection, New York

30. Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

God Bless America—sign in private garden in South Carolina, 1964

Gelatin silver print

8 ¼ x 5 ½ inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of anonymous benefactors, 2025, 2025.35.95

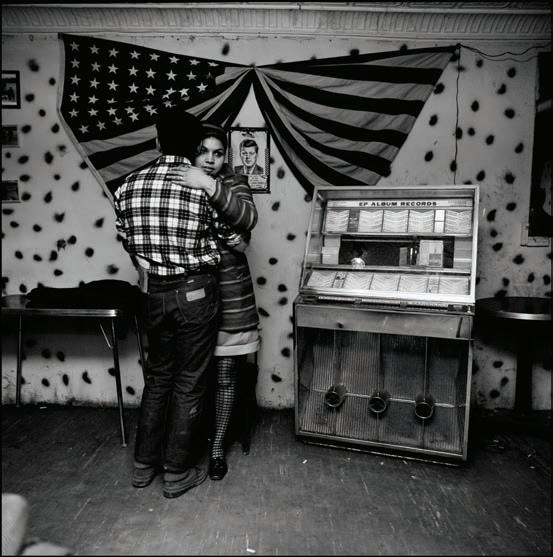

31. B ruce Davidson (American, born 1933)

Untitled, from the series East 100th Street, photographed 1966-68, printed 2014

Archival pigment print

15 x 15 inches

Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of Hugh and Sandra Lawson

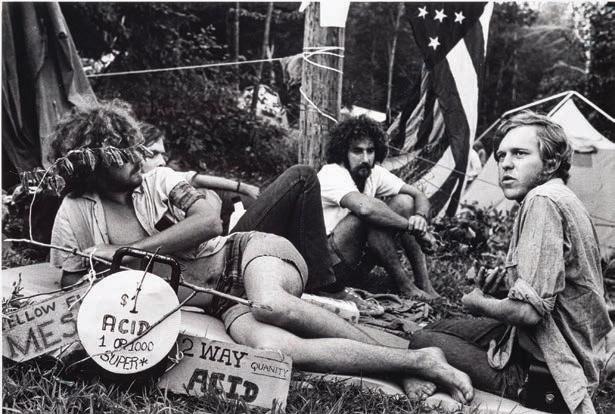

32. Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

Drug dealers advertising acid for $1 at the Powder Ridge Rock Festival, Connecticut, 1970

Gelatin silver print

6 ¼ x 9 ½ inches

Private Collection, New York

33. Stanley Joseph Forman (American, born 1945)

The Soiling of Old Glory, photographed 1976, printed in 1982

Gelatin silver print

11 x 14 inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Museum purchase, 2024, 2024.32.01

34. Leandro Joo (Cuban, born 1957)

Y lo que nos une sellama estrella Selladora, 1998

( And what unites us is called Star Sealing Machine)

Gelatin silver print

10 ½ x 7 inches

Courtesy of Benjamin Ortiz and Victor Torchia, Jr.

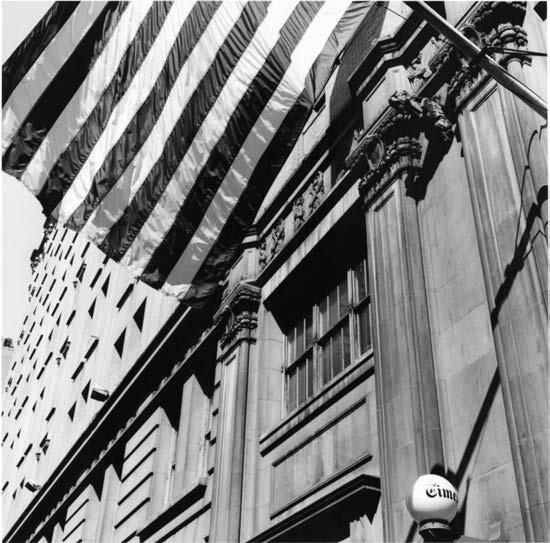

35. Philip Trager (American, born 1935)

Times Square at Duffy Square, from 7th Avenue between West Forty-sixth and West Forty-seventh, 1977-1979

Archival pigment print

29 7/8 x 37 ¾ inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, 2024, Gift of Philip and Ina Trager, 2024, 2024.28.03

36. Robert Longo (American, born 1953)

Black Flag, 1990

Lithograph in black ink on wove paper

Published by Bill Bradley for U.S. Senate

22 3/8 x 30 inches

Edition: 50, plus 14 artist’s proofs

Lent by Adam Reich and Clare Walker

37. Adger Cowans (American, born 1936)

South Ferry, Coenties Slip, ca. 1980

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist

38. Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925-2008)

Kennedy Campaign Print, 1994

Color offset lithograph

Printed and published by ULAE, West Islip, New York

28 ½ x 20 ½ inches

Edition: 100

Lent by Heather and David Joinnides

39. David Hammons (American, born 1943)

African American Flag, 1990

Dyed cotton

96 × 60 inches

Courtesy of the New School Art Collection

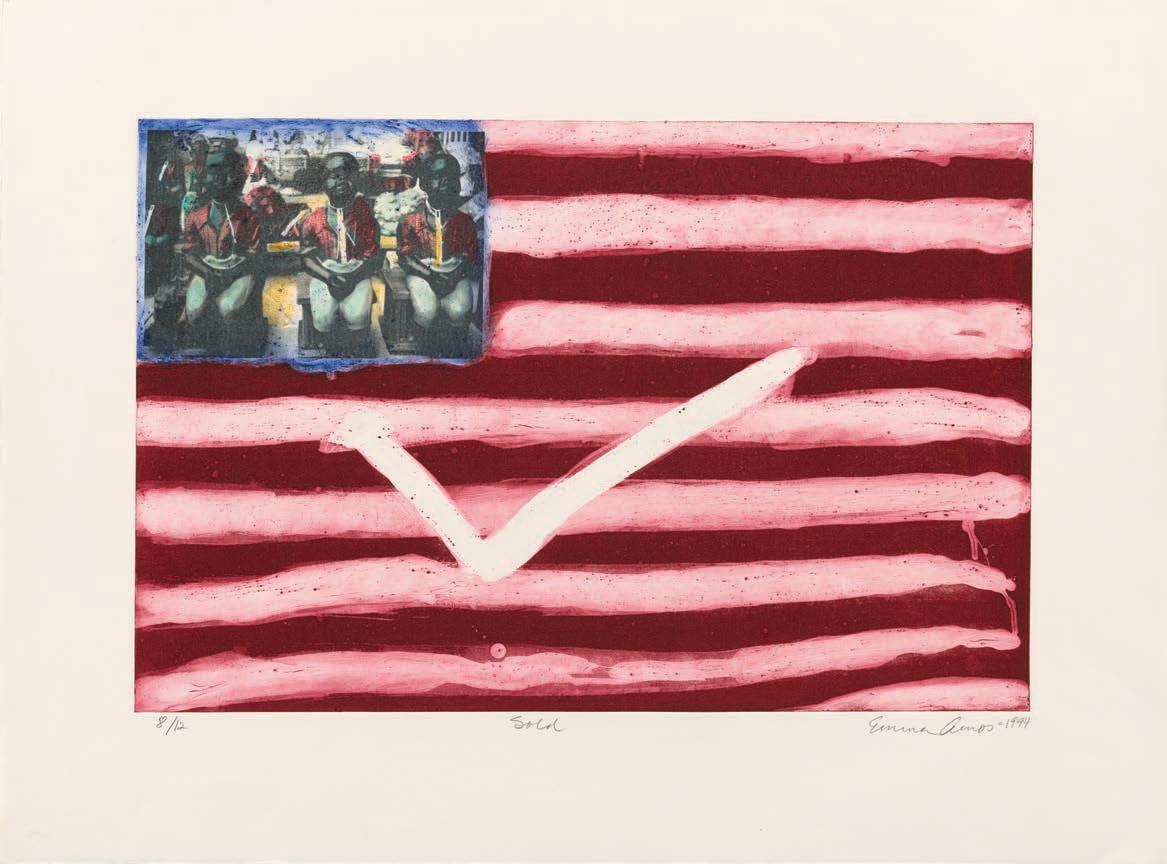

40. Emma Amos (American, 1937-2020)

Sold, 1994

Color silk aquatint with photo transfer

K. Caraccio Studio, printer and publisher

15 x 22 13/16 inches

Edition: 12

Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Jean and Robert E. Steele, M.P.H. 1971, M.S. 1974, Ph.D. 1975

41. Danielle Scott (American, born 1978)

False Flag, 2020

Photo transfer and found objects (shotgun shells) on U.S. flag

48 x 96 inches

Courtesy of the artist

42. Imo Nse Imeh (American, born Nigeria, 1980)

and i’ll be there with you, 2021

Charcoal, India ink, and conte crayon on unstretched canvas

84 x 108 inches

Courtesy of the artist

43. Sara Rahbar (American, born Iran, 1976)

I don’t trust you anymore, Flag #59, 2019

Mixed media, collected vintage objects, on vintage U.S. flag

78 x 48 inches

Courtesy of Sara Rahbar

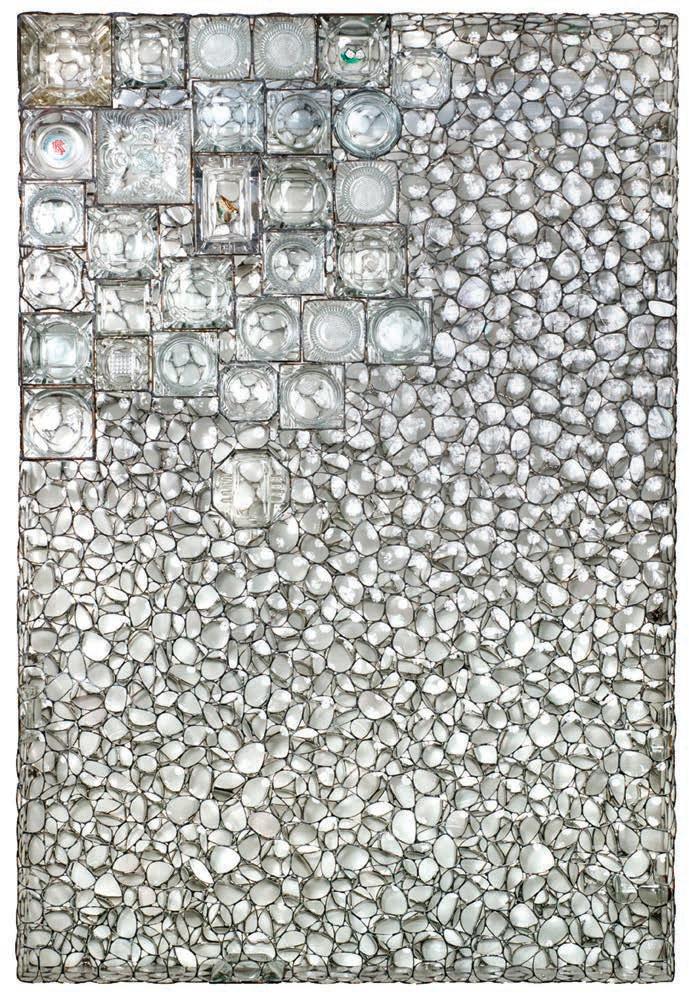

44. Richard Klein (American, born 1955)

Transparency, 2007

Eyeglasses, ashtrays, glass jars, brass

62 x 42 ½ x 5 ½ inches

Courtesy of the Connecticut Artists Collection, Connecticut Office of the Arts

45. June Clark (Canadian, born USA, 1941)

Dirge, 2003-2004

Oxidized metal on canvas

36 x 51 ¼ inches

Collection Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Purchase, with funds by exchange, and funds from Joyce and Fred Zemans, 2021

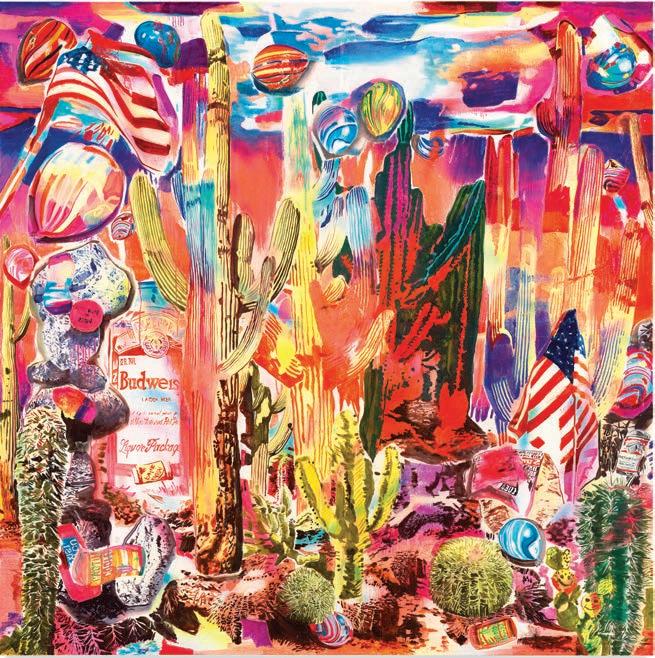

46. Rosson Crow (American, born 1982)

Fragility (Pax Americana), 2023

Acrylic, spray paint, photo transfer, and oil on canvas

67 x 67 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery

47. Eric Fischl (American, born 1948)

You Don’t Need a Weatherman…, 2022

Acrylic on linen

75 x 65 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Skarstedt Gallery

48. Jeannette Montgomery Barron (American, born 1956)

Flag #1, July 2000, CT, 2000

Gelatin silver print

11 x 14 inches

Edition: 8/25

Courtesy of the artist, and James Barron Fine Art

49. Skylar Fein (American, born 1968)

White Flag for Franklin Rosemont (small), 2019

Acrylic on plaster and wood, ink and encaustic 11 x 18 inches

Courtesy of Ferrara Showman Gallery, New Orleans

50. Marina Kamena (French, born Yugoslavia, 1945)

We the People, 2023

Acrylic on canvas mounted on aluminum stretchers, encased in wood crate

72 ¼ x 68 ¼ x 12 inches

Courtesy of the artist

51. Liu Zhong (Chinese, born 1969)

Ting Fēng (Listening to the Wind), 2014

Ink on paper

53 9/16 x 26 ¾ inches

Fairfield University Art Museum,

Gift of Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. ’85 and Kimberly Rockefeller ’85, 2024, 2024.33.01

52. Katharine Kuharic (American, born 1962)

Girl’s Army – the bitches, 2003

Oil on linen

60 x 40 inches

Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York

53. Salvador Jiménez-Flores

(American, born Mexico, 1985)

La Jaula de Oro (The Golden Cage), 2020

Color screenprint

12 x 18 inches

Edition: 25

Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Connecticut, Museum Purchase, Acquisitions Fund, 2022, 2022.31.1

54. Frank Diaz Escalet (Puerto Rican, 1930-2012)

Mojados, 1994

Color offset print

18 x 24 inches

Edition: 300, plus artist’s proofs

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of Ben Ortiz and Victor Torchia, Jr., 2024, 2024.34.03

55. James Prosek (American, born 1975)

Invisible Boundaries, 2021

Acrylic on panel

22 7/8 x 36 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Waqas Wajahat, New York

56. Jeremy Dean (American, born 1977)

Executive Order 13769, USA, 2018

From the Rended series

Flag threads, 3,000 needles

24 x 27 x 5 inches

Lent by Gabrielle Selz

57. Mark Thomas Gibson (American, born 1980)

The Wringer, 2021

Ink on canvas

45 ½ x 64 inches

The Collection of Michael Citrone

58. Ju lie Mehretu (American, born 1970)

Corner of Lake and Minnehaha, 2022

17-run color screenprint on white Coventry Rag paper

Co-published by Highpoint Editions and the Walker Art Center

47 x 37 inches

Edition: 45

© 2022 Julie Mehretu, courtesy of the artist, Highpoint Editions, and the Walker Art Center

59. Tim Ferguson Sauder (American, born 1972)

Return Design Lab, Olin College

American Flag 5, 2019 [Nature, VT + Honorary Heather Heyer Way, Charlottesville, VA],

Plywood with gathered marks, fixative

25 ½ x 37 ½ inches

Courtesy of the artist

60. D read Scott (American, born 1965)

Emancipation Proclamation, 2020

Pigment print

20 x 16 3/8 inches

Edition: 2/4, with 1 artist’s proof

Courtesy of the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery

61. G lenn Ligon (American, born 1960)

Untitled, 2002-2024

Digital pigment print on Canson Platine paper

16 1/8 x 24 ¼ inches

Edition of 7 and 3 APs

Courtesy of the artist

62. Shepard Fairey (American, born 1970)

American Rage, 2020

Offset lithograph on Speckletone paper

36 x 24 inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 2023, 2023.03.01

63. Demian DinéYazhi’ (Diné, born 1983)

My Ancestors Will Not Let Me Forget This, 2020

Letterpress print

18 x 24 inches

Forge Project Collection, traditional lands of the Moh-He-Con-Nuck

64. Stephanie Syjuco (American, born Philippines, 1974)

Color Checker (Pileup), 2019

Archival pigment print

26 ½ x 40 inches

Edition: 8

© Stephanie Syjuco. Courtesy of the artist; Catharine Clark Gallery, CA; and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

65. Robert von Sternberg (American, born 1939)

9/11 Flags, Pepperdine University, Malibu, California, 2012

Archival inkjet print

11 x 16 ½ inches

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 2025, 2025.09.04

66. James Prez (American, born 1953)

Twin Towers: Everyday’s A Bonus, September 15, 2001

Acrylic on wood panel

9 ¼ x 10 1/8 inches

Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Connecticut, Gift of Benjamin Ortiz and Victor Torchia, Jr., 2023, 2024.9.2

67. Nathan Lyons (American, 1930-2016)

Untitled [2 flags over God Bless America poster], from the series After 9/11, 2001

Gelatin silver print

4 ½ x 6 ¾ inches

Yale University Art Gallery, Purchased with the Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund and gifts from Arthur Fleischer, Jr., B.A. 1953, LL.B. 1958 and Betsy Karel

68. Kristin Capp (American, born 1964)

West 43 rd Street, New York, 1998

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Edition: 2/25

Fairfield University Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 2025, 2025.42.01

69. Morton Kaish (American, 1927-2025)

Stars and Stripes, 1996 (completed 2021)

Acrylic on linen

78 x 66 inches

Collection of the Kaish Family Art Project

70. H ank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976)

This Ain’t America, You Can’t Fool Me, 2020

Hand-glazed porcelain

9 x 15 x 6 inches

Edition: 5/5, with 2 artist’s proofs

© Hank Willis Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

71. Jay Critchley (American, born 1947)

Old Glory Condom Corporation condom package display, 1990

Cardboard box with condom packages

8 x 9 ½ x 3 inches (box), 2 x 1 ½ x ¼ inches (each condom package)

Courtesy of the artist

72. Maria de Los Angeles (American, born Mexico, 1988)

Freedom Is Not Free?, 2025-2026

Mixed media textile, painting, drawing, collage, American Flag, Mexican Flag, self-made flags, painting fragments

Contributions by workshop participants, embroidery by Marina Cisneros

Size variable

Courtesy of the artist

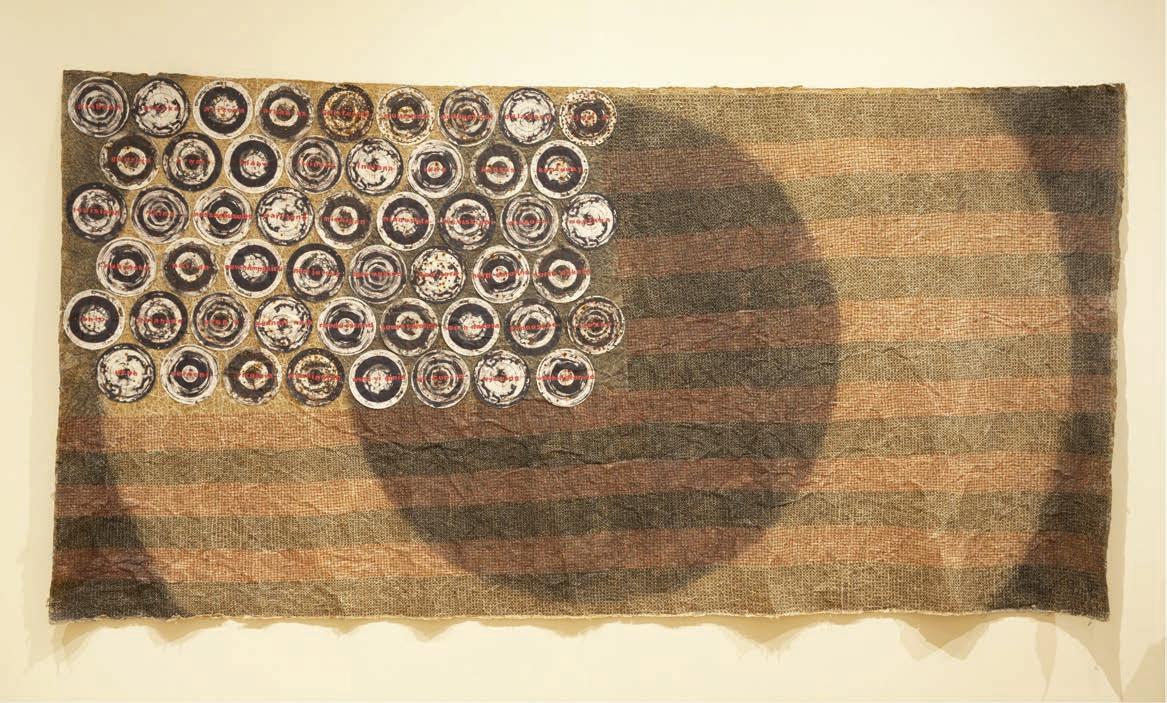

73. Deborah Nehmad (American, born 1952)

old glory?, 2017

Waxed handmade Nepalese paper, hand stitching, pigmented prints, pyrography, collage

58 x 116 inches

Courtesy of Deborah G. Nehmad

74. Joseph Smolinski (American, born 1975)

Thin Ice, 2020

Digital animation

6:30

Courtesy of the artist

Events listed below with a location are live, in-person programs. When possible, those events will also be streamed on Arts & Minds Live and the recordings posted to the Museum’s YouTube channel.

Register at: fuam.eventbrite.com

Thursday, January 22, 5:30 p.m.

Opening Night Lecture: For Which It Stands…

Aaron Q. Weinstein, PhD (Assistant Professor of Politics, Fairfield University, and Exhibition Faculty Liaison)

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Kelley Theatre and streaming

Thursday, January 22, 6:30 p.m.

Opening Reception: For Which It Stands…

Bellarmine Hall, Great Hall and Bellarmine Hall Galleries (the Walsh Gallery will also be open for viewing)

Thursday, January 29, 7:30 p.m.

Short Film Screening and Panel Discussion:

Reclaim the Flag (2025), with filmmaker

Alexis Bittar, chaired by Sean Edgecomb, PhD (Associate Professor of Theatre and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Fairfield University Department of Visual & Performing Arts) with additional panelists Luchina Fisher (Visiting Assistant Professor of Film, Fairfield University Department of Visual & Performing Arts) and Shane Vogel, PhD (Professor of English and Black Studies, and Chair of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies, Yale University)

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Kelley Theatre (co-sponsored by FUAM)

Free; tickets required via QCA Box Office

Thursday, February 26, 5 p.m.

Lecture: American Art at the Crossroads: Between WPA

Realism and Post-War Abstraction

Viviana Bucarelli, PhD (Independent Scholar)

Bellarmine Hall, Diffley Board Room and streaming

Part of the Edwin L. Weisl, Jr. Lectureships in Art History, funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation

Thursday, March 19, 5:30 p.m.

Lecture: The Soiling of Old Glory: The Story of a Photograph That Shocked America

Louis P. Masur, PhD (Distinguished Professor of American Studies and History, Rutgers University)

Dolan School of Business Event Hall

Note: this event will not be livestreamed

Thursday, April 9, 6 p.m.

Art Speaks! Campus and community members are invited to share their own responses to the For Which It Stands… exhibition through works of poetry and short prose.

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Walsh Gallery

Thursday, April 16, 5:30 p.m.

Lecture: Florine Stettheimer and Americana

Barbara Bloemink, PhD

Bellarmine Hall, Diffley Board Room and streaming

Part of the Edwin L. Weisl, Jr. Lectureships in Art History, funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation e x HI b I t I on P rogr A ms

Thursday, February 12, 5:30 p.m.

Lecture: Pictures and Progress: The Path of Black Liberation in American Photography

Sarah Churchill, PhD (Adjunct Faculty, Art History, Fairfield University Department of Visual & Performing Arts)

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Wien Experimental Theatre and streaming

CURATOR’S TOURS

Limited to 25 participants; registration required

• Thursday, March 26, 5:30 p.m.: Bellarmine Hall Galleries

• Thursday, April 30, noon: Bellarmine Hall Galleries

• Thursday, April 30, 5:30 p.m.: Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Walsh Gallery

• Wednesday, May 27, noon: Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Walsh Gallery

• Thursday, June 18, 5:30 p.m.: Bellarmine Hall Galleries

GALLERY TALKS

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Walsh Gallery

• Thursday, March 5, 5:30 p.m.: Sara Rahbar and Maria de Los Angeles

• Tuesday, April 14, noon: Richard Klein and James Prosek

• Thursday, April 23, 5:30 p.m.: Danielle Scott and Imo Nse Imeh

ART IN FOCUS

In-person, select Thursdays at noon and streaming at 1 p.m.

• February 12: Childe Hassam, Italian Day, May 1918, 1918, oil on canvas

• March 12: Jane Hammond, Untitled, 1993, oil on canvas with metal leaf

• April 9: Julie Mehretu, Corner of Lake and Minnehaha, 2022, color screenprint

• May 7: Rosson Crow, Fragility (Pax Americana), 2023, acrylic, spray paint, photo transfer, and oil on canvas

FAMILY DAYS

Select Saturdays, 12:30-2 p.m. and 2:30-4 p.m. (Space limited; registration required)

• Saturday, January 24: Stars, Stripes & Brushstrokes: American Impressionism Workshop

Bellarmine Hall, Museum Classroom

• Saturday, February 21: Red, White, and YOU!: A Comics Workshop

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Lobby

• Saturday, March 28: Stitching Stories: Design Your Family Flag

Bellarmine Hall, Museum Classroom

• Saturday, April 25: Bits & Pieces, Stars & Stripes: Reimagined Flags from Recycled Finds

Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts, Lobby

fairfield.edu/museum/for-which-it-stands

P H otogr APHIC C red I ts

Pg. 3, cat. 45: © June Clark, courtesy of the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: LF Documentation. 2020/137

Pg. 6, cat. 42: © Imo Nse Imeh

Pg. 8, cat. 65: © Robert von Sternberg

Pg. 9, cat. 1: Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Italian Day, May 1918, 1918, oil on canvas, 36 x 26 in. Art Bridges

Pg. 12, cat. 10: © Joe Rosenthal

Pg. 12, cat. 18: © 2012 Keith Mayerson

Pg. 13, cat. 23: © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

Pg. 14, cat. 60: Courtesy of the Artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York

Pg. 14, cat. 24: Photograph © Larry Fink/MUUS Collection. Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of Ron Sadi

Pg. 15, cat. 43: © Sara Rahbar

Pg. 16, cat. 41: © Danielle Scott

Pg. 17, cat. 63: Forge Project Collection, traditional lands of the Moh-He-Con-Nuck

Pg. 18, cat. 6: Photograph by John Gutmann. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Pg. 18, cat. 27: © Danny Lyon / Magnum Photos. www.bleakbeauty.com.

Instagram: @dannylyonphotos2

Pg. 18, cat. 33: © Stanley Forman

Pg. 19, cat. 55: © James Prosek

Pg. 20, cat. 72: © Maria de Los Angeles

Pg. 27, cat. 4: Ernest Lawson (1873-1939), Washington Bridge, New York City, c. 1915-1925. Oil on canvas. 25 1/4 x 30 1/4 in. (64.1 x 76.8 cm).

Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the Friends of Art, 1964

Pg. 28, cat. 3: N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945), The Victorious Allies, 1918. Oil on canvas. 45 1/4 × 34 1/4 in. (114.9 × 87 cm). Delaware Art Museum, Gift of the Bank of Delaware, 1989

Pg. 29, cat. 2: Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer

Pg. 30, cat. 6: © Frelinghuysen Morris House & Studio, Lenox, Massachusetts. Yale University Art Gallery. Purchased with The Iola S. Haverstick Fund for American Art in honor of Professor Alexander Nemerov, Ph.D. 1992

Pg. 31, cat. 7: Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Pg. 32, cat. 21: © Fritz Scholder. Courtesy the estate of the artist and

Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, New York. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of the Lorillard Company

Pg. 33, cat. 19: © Audrey Flack Foundation

Pg. 34, cat. 21: © Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos. Art Properties, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, Gift of Hugh and Sandra Lawson

Pg. 34, cat. 29: © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

Pg. 35, cat. 30: © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

Pg. 35, cat. 32: © Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

Pg. 39, cat. 46: Courtesy of the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

Pg. 40, cat. 71: © Jay Critchley

Pg. 41, cat. 40: © 2025 Emma Amos / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY, Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Jean and Robert E. Steele, M.P.H. 1971, M.S. 1974, Ph.D. 1975

Pg. 42, cat. 54: © Frank Diaz Escalet

Pg. 43, cat. 53: © 2025 Salvador Jiménez-Flores. Collection of the Mattatuck Museum, Museum Purchase, Acquisitions Fund, 2022

Pg. 44, cat. 68: © Kristin Capp

Pg. 44, cat. 69: © 2026 Morton Kaish / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pg. 45, cat. 73: © Deborah G. Nehmad

Pg. 46, cat. 44: © Richard Klein

Pg. 47, cat. 52: © Katharine Kuharic. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W., New York

Pg. 48, cat. 49: © Skylar Fein

Pg. 49, cat. 64: © Stephanie Syjuco. Courtesy of the artist; Catharine Clark Gallery, CA; and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Pg. 50, cat. 70: © Hank Willis Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Pg. 51, cat. 58: © Julie Mehretu. Image Courtesy of Highpoint Editions and Julie Mehretu

Pg. 55, cat. 17: © Jane Hammond. Courtesy Galerie Lelong

Pg. 58, cat. 48: © Jeannette Montgomery Barron

Pg. 59, cat. 57: © Mark Thomas Gibson. Photo Credit: M+B

Pg. 61, cat. 35: © Philip Trager

A C knoW ledgements

For Which It Stands… is the centerpiece of the Museum’s year-long programming focused on the commemoration of the U.S. Semiquincentennial. This exhibition is the product of great goodwill and generosity by many people.

The invaluable collaboration of numerous colleagues at Fairfield University is gratefully acknowledged: Christine Siegel, Provost; Richard Greenwald, Dean of the John Charles Meditz College of Arts & Sciences; and Geri Derbyshire, Senior Vice President for University Advancement, as well as museum staff members Michelle DiMarzo, Curator of Education and Academic Engagement; Megan Paqua, Registrar; Heather Coleman, Museum Assistant; and Elizabeth Vienneau, Museum Educator. Further acknowledgement is due to Marie-Laure Kugel, Edmund Ross, Jennifer Anderson, Susan Cipollaro, Kiersten Bjork, Jackie Bertolone, Katy Reed, Julie Peters, Alistair Highet, Tess Long, Charlie McMahon, Lisa Thornell, Keith Broderick, Lori Jones, Katie Lang, Russ Nagy, Dan Vasconez, and Robert Bove.

We especially thank Aaron Weinstein, faculty liaison to the exhibition and assistant professor of Politics, for his contribution of the essay in this catalogue entitled “American Canvas: The Flag, Art, and Contested Meaning in U.S. Politics,” and for his opening night lecture. The Museum is also grateful to Fairfield University President Mark R. Nemec and Henry Adams for their thoughtful essays.

The majority of the “traditional” wall labels were written by Emily Handlin, and we are grateful for her precision, promptness, and collegiality. Those wall labels are enriched by a variety of faculty and staff from across the University, who contributed additional wall labels, each contextualizing a particular artwork within the framework of their own disciplinary lens or personal experience. The Museum is so appreciative of the University community members who contributed their unique voices to this project: Gayle A. Alberda, Peter L. Bayers, Suzanne Chamlin, Joanna Chang, Sarah Churchill, Jennifer Cook, Ive E. Covaci, Erin S. Craw, Sean F. Edgecomb, Cheryl Yun Edwards, Philip I. Eliasoph, Johanna Garvey, Richard A. Greenwald, Kim Gunter, Phil Klay, Danke Li, Julie Leavitt Learson, Silvia Marsans-Sakly, Meryl C. O’Connor, Marice Rose, Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, Gabriel Sacco, L. Kraig Steffen, Lisa Thornell, Andrew Farinholt Ward, Brian Walker, Aaron Q. Weinstein, Lydia Willsky-Ciollo, and Jo Yarrington.

In addition, we are indebted to the Museum’s Collections Committee for their wisdom and support: Nora Daley, Mike Goss, John Meditz, Suzanne Nemec, Benjamin Ortiz, Russell Panczenko, Christine Siegel, Christopher Steiner, Diallo Simon-Ponte, Michael Vigario, and Matthieu Waldemar.

Finally, the Museum acknowledges with gratitude the many generous lenders (and donors of artworks) to this exhibition, without whom it would not have been possible:

ACA Galleries, New York

Adger Cowans and Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York

Al Hirschfeld Foundation

Art Bridges

Art Gallery of Ontario and June Clark

Jeanette Montgomery Barron and James Barron Fine Art

Bridgeport Public Library Collections

Kristin Capp

Michael Citrone

Jay Critchley ’69

Columbia University, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Rosson Crow and Miles McEnery Gallery

Delaware Museum of Art

Skylar Fein and Ferrara Showman Gallery, New Orleans

Eric Fischl and Skarstedt Gallery

Forge Project Collection

Audrey Flack

Imo Nse Imeh

Glenn Ligon and Hauser & Wirth, New York

Kaish Family Art Project

Marina Kamena

Estate of Hanns and Patricia Kohl

Heather and David Joinnides

Katharine Kuharic and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York

Maria de Los Angeles

Herman Maril Foundation and Debra Force Fine Art, New York

Mattatuck Museum

Julie Mehretu, Highpoint Editions, and the Walker Art Center

Deborah G. Nehmad

The New School Art Collection

David Nolan Gallery, New York

Orlando Museum of Art

Benjamin Ortiz and Victor Torchia, Jr.

Robert K. Otnes Trust

Gordon Parks Foundation

James Prosek and Waqas Wajahat, New York

Sara Rahbar

Adam Reich and Clare Walker

Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. ’85 and Kimberly Rockefeller ’85

Avo Samuelian and Hector Manuel Gonzalez

Tim Ferguson Sauder

Danielle Scott

Dread Scott and Cristin Tierney Gallery

Richard and Monica Segal

Gabrielle Selz

Susan Sheehan Gallery, New York

Ming Smith, Mingus Murray, and Nicola Vassell Gallery

Joseph Smolinski

Stephanie Syjuco and Ryan Lee Gallery, New York

Philip and Ina Trager

State of Connecticut, CT Artists Collection, Office of the Arts

Hank Willis Thomas and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Robert von Sternberg

Westport Public Art Collections

Demian DinéYazhi’ and Forge Project Collection

Yale University Art Gallery

Support for this exhibition and related programs has been generously provided by:

National Endowment for the Humanities

Horizon Kinetics

Maximilian E. & Marion O. Hoffman Foundation, Inc.

Connecticut Humanities

Art Bridges

The Robert Lehman Foundation

Delamar Southport

Aquarion Water Company

Media Sponsors

WSHU/Public Radio

Westport Journal

Fairfield University Arts Institute

Berggruen Gallery

Kaish Family Art Project

Michael Vigario ’08

Diana Bowes

Patricia and Joseph Sacco P’13

Anonymous Donors

The Fairfield University Art Museum is deeply grateful to the following corporations, foundations, and government agencies for their generous support of this year’s exhibitions and programs. We also acknowledge the generosity of the Museum’s 2010 Society members, together with the many individual donors who are keeping our excellent exhibitions and programs free and accessible to all and who support our efforts to build and diversify our permanent collection.