SPRING/SUMMER 2025

SPRING/SUMMER 2025

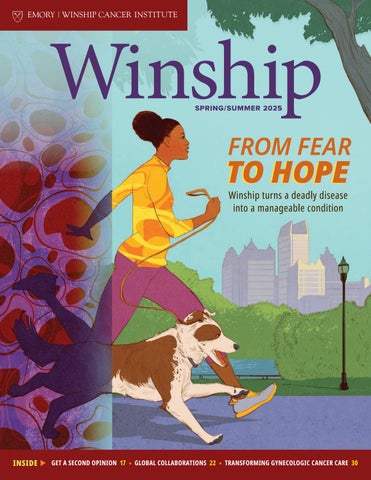

Winship turns a deadly disease into a manageable condition

10

The story of multiple myeloma treatment at Winship is one of perseverance, partnerships and science becoming hope for all those diagnosed or living with the condition today.

30

Susan C. Modesitt has built a gynecologic cancer care center and revolutionized gynecologic cancer care for Georgia women.

22

Winship is part of a global network of cancer research, sharing expertise and learning from colleagues abroad.

17

Getting a second opinion is about having a different medical perspective and assessing your comfort level with a physician.

34

"You can still do incredible things after a cancer diagnosis," Christy Erickson says. She would know.

From the Executive Director 2

Pioneering Perspective 3

GABE A. KWONG

A glimpse into the future of cancer screening

Trailblazers 5

COVER STORY

Turning the Tide 10

Winship leads the way in multiple myeloma advances.

FEATURES

Why a Second Opinion for Cancer Care Matters 17

A second opinion could make all the difference in the experience and the outcomes.

How Collaborations Abroad

Strengthen Communities at Home 22

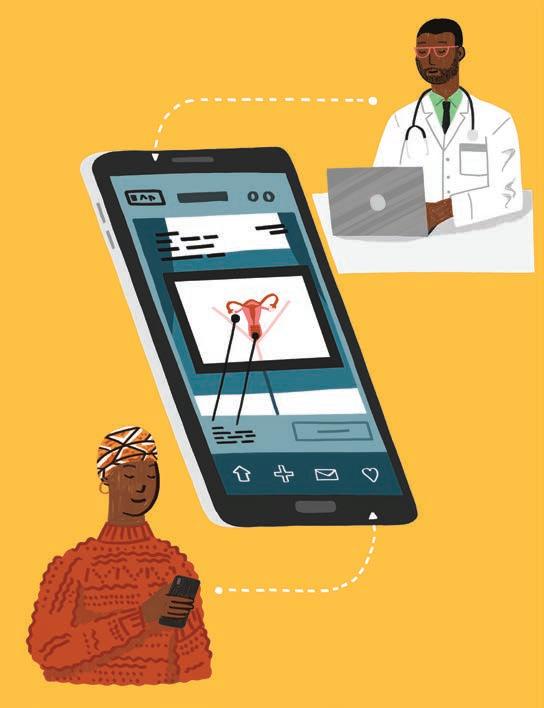

Transforming Gynecologic Cancer Care for Georgia Women 30

Winship offers clinical trials and leading-edge care as regional “powerhouse” in the field.

PATIENT PROFILE | Medical Research, Expert Care and Targeted Therapy

Changed Christy Erickson’s Life 34

AROUND WINSHIP

PHILANTHROPY

Edye Bradford found a second family at Winship. 38

INSPIRING HOPE

Q&A with director of Winship's Palliative Medicine Program Kimberly A. Curseen 40

EDITORIAL

Editor

John-Manuel Andriote

Art Director

Linda Dobson

Lead Photographer

Jenni Girtman

Contributors

Andrea Clement

Susannah Conroy

Javier De Jesus

Heitor De Paula

Jenny Owen

Denise Ribeiro

Chatanya Tucker

Michelle Varraveto

GET IN TOUCH

john.manuel.andriote@emory.edu

CHECK OUT OUR ONLINE VERSION

ON THE COVER: Once an invariably fatal illness, multiple myeloma today can be managed with medication. Winship has played a big role in making it possible.

ILLUSTRATION BY PAUL TONG

Emory | Winship Magazine is published by the communications office of Winship Cancer Institute, a part of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center of Emory University, emoryhealthsciences.org. Articles may be reprinted in full or in part if source is acknowledged. If you have story ideas or feedback, please contact john.manuel.andriote@emory.edu. © Emory University

Emory is an equal opportunity employer, and qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, protected veteran status or other characteristics protected by state or federal law. Inquiries should be directed to the Department of Equity and Civil Rights Compliance, 201 Dowman Drive, Administration Bldg, Atlanta, GA 30322. Telephone: 404-727-9867 (V) | 404-712-2049 (TDD).

Website: winshipcancer.emory.edu. To view past magazine issues, go to winshipcancer.emory.edu/magazine.

Welcome to the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of Winship Magazine.

We are especially excited with this issue to share the magazine’s refreshed look and hope you will find its contents both informative and inspiring.

We begin with a look into the future of cancer screening to a time when today’s research

transform Winship’s formerly small gynecologic program into a regional powerhouse.

Our patient profile in this issue shares the inspiring story of one of my own patients, Christy Erickson. As a nonsmoker she was shocked to learn she had stage four lung cancer. Her particular cancer was associated with very poor outcomes. But research from the LAURA study, which I led, offered another transformation by enabling us to treat and manage this once-deadly form of cancer as more of a chronic condition—enabling people like Christy to live longer, fuller lives.

Edye Bradford’s relationship with Winship began in 2006, when she was treated successfully for colon cancer. After her treatment, and because of the wide network of friends she made during her visits, Bradford decided to support cancer research through her estate. The legacy fund she will leave bears her name and her late husband’s, The William and Edith Bradford Cancer Research Endowment. “When someone gives you your life back, you remember it,” she says.

We close out the issue with our “Inspiring Hope” interview, this time with Kimberly A. Curseen, director of Winship’s Palliative Medicine Program and director of Supportive and Palliative Care Outpatient Services for Emory Healthcare. Curseen explains that palliative care doesn’t replace your doctors, but helps manage the symptoms of your illness, whether those symptoms are physical, emotional, spiritual or social.

Thanks for your interest and support on behalf of our clinicians, researchers and, most of all, our patients.

With deep appreciation, SURESH S. RAMALINGAM

By Gabe A. Kwong • Illustration by Chris Gash

Amulti-cancer early detection (MCED) test for general screening could help find more cancers earlier and potentially save lives But aside from five cancers with approved screening tests—colonoscopy for colorectal cancer, Pap smears and HPV tests for cervical cancer, mammograms for breast cancer, low-dose CT scans for lung cancer and PSA tests, often along with digital rectal exams, for prostate cancer—there are no effective screening methods for other types of cancer, much less a single test that can detect multiple cancers.

The most widely adopted approach to tackling this grand health challenge mainly focuses on the identification of markers released by tumor cells, such as cell-free DNA and proteins, in the blood or other bodily fluids to spot early signs of cancer. But the trouble is that these tumor markers are present in such vanishingly small quantities that it can be difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish early signs of cancer from normal healthy tissue.

For instance, one of the most promising methods for multi-cancer screening involves ultra-sensitive sequencing of circulating tumor DNA, which is released into the blood from dead or dying cancer cells. Yet, regulatory agencies do not currently recommend these commercially available tests for routine use, as they have been inadequate in detecting cancer at its earliest and most treatable stages in patient studies.

Over the past decade, my research team and I have introduced a radically new approach to early cancer detection based on bioengineering sensors to query tissues. Instead of searching for rare biomarkers in blood, we deploy these tiny sensors throughout the body to hunt for cancer cells, producing a signal that can be easily identified in samples like urine that would otherwise not be present in healthy individuals.

These sensors are activated when they encounter cancer enzymes that are overexpressed by nascent tumors as they grow and invade surrounding tissues. These enzymes act as a biological switch, turning on the sensors to amplify the release of a synthetic biomarker that can rise to far higher levels than natural tumor markers. This gives us a much stronger signal to detect cancer, improving the likelihood of finding cancer early. In preclinical cancer models, synthetic biomarkers were found to outperform native biomarkers, including circulating tumor DNA, making it possible to detect cancer much earlier.

Where do we go from here? It turns out that while enzymes make up more than 15% of all human genes, it is not fully understood how their activity differs between various types of cancers and healthy tissue. To change this, we are creating a cancer atlas that focuses on mapping enzyme activity rather than just the abundance of genes, aiming to significantly increase our understanding of the biology of human cancers. We envision that this groundbreaking catalog will pave the way for the development of sensor panels for multi-cancer screening, by helping us pinpoint the best enzymatic signals around which to build future screening tools.

Giant strides are also being made in sensor design. It is now possible to create sensors that implement computer logic, such as the “AND” operation. Just as you need both a username and password to access your account, these logic-based sensors require multiple enzymatic inputs, occurring at the same location within the body, to unlock a detection signal. This level of precision means that these sensors are adept at avoiding false signals, like those that could be caused by common illnesses such as the flu, to reduce the chances of misdiagnosis. In other words, it adds an extra layer of accuracy, helping to ensure that the detected signal is caused by cancer, and not by something else.

Perhaps the most enabling aspect of our approach is that it paves the way forward to engineer bespoke screening tests tailored to specific requirements. For instance, these sensors can be paired with different carriers to target different parts of the body. They can be designed to produce signals in the blood, urine or

breath samples, which can then be detected using ultrasensitive lab equipment, or low-cost paper tests for point-of-care use in resource-limited environments. There are even successful examples of genetically engineered immune cells designed to function as living sentinels for cancer detection—these special cells essentially patrol the body and flag the presence of cancer.

As these sensors move closer toward human use, their safety will need to be carefully and rigorously evaluated. A multiscreening test for widespread use needs to be safe for routine administration and should not provoke an immune response that could neutralize the sensors or prevent future reuse. Additionally, the clinical entry point will need to be carefully selected to minimize risk and demonstrate early success of the technology. Demonstrating success in detecting early responses to common cancer drugs or recurrence in patients in remission could expedite large-scale deployment for MCED screening.

While much work remains, technological advancements are rapidly accelerating at an incredible pace to meet the challenge soon. Imagine a future where we can screen for multiple types of cancer at their earliest stages, picking up where current tests fall short. Picture a world where the success of early cancer screening leads to better treatment outcomes, longer patient lifespans and a reduced economic burden on our health care system. The future of multi-cancer screening is on the horizon, and it is closer than ever. WM

GABE A. KWONG is a member of the Cancer Immunology Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute, and an assistant professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech School of Engineering and Emory University School of Medicine.

Meet four of Winship's outstanding research scientists whose day-to-day work is changing the game in important ways for people with cancer.

HANIA A. AL-HALLAQ is vice chair and division chief of medical physics in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, which she joined in 2024. She is also a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program. Al-Hallaq is widely recognized for her work on computed tomography (CT) radiomics and has served as principal investigator for national protocols studying the safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for metastatic disease.

WM: IN LAY TERMS, WHAT IS MEDICAL PHYSICS, AND HOW DOES PHYSICS CONTRIBUTE TO THE PRACTICE OF MEDICINE?

HA-H: We study the principles of physics and apply them to medical treatments that involve the use of radiation. We work in conjunction with the radiation oncology physicians. Physicians determine if a patient needs radiation, how much and to which areas of the body. The medical physicist works on ensuring that the calculations are accurate and that treatment machines are working correctly so that the physician’s treatment plan is delivered to the patient as intended. Medical physicists are also heavily involved in innovating cancer treatment—by designing new treatment machines and software tools or implementing new technologies into the clinic in a safe manner. We spend a lot of time analyzing data and proposing solutions to improve the safety and quality of treatments. At academic centers like Emory, we also train the next generation of medical physicists.

WM: HOW DO PATIENTS BENEFIT FROM X-RAY AND 3D SURFACE IMAGING MODALITIES FOR BREAST CANCER TREATMENTS?

HA-H: A radiation plan is developed based on a CT scan of the patient in the treatment position. When the patient returns for treatment (usually for many sessions), it’s important to ensure that the patient is positioned in the same way as when the radiation plan was developed. It’s amazing that radiation treatments have been tailored to individual patients for so long, but the challenge lies in reproducing this plan that is uniquely tailored to the patient’s anatomy. Because we have X-ray capabilities built into our treatment machines, we use X-ray imaging to re-position patients for treatment to match the planned position. Surface imaging is a unique method of using light instead of ionizing radiation to map a 3D model of the patient’s body surface. It can also track that surface in real time to allow us to observe changes due to breathing or a deep breath-hold. It turns out that during a deep breath-hold, the tissue targeted by the physician during breast cancer irradiation naturally moves away from critical organs like the heart and lungs. This is a wonderful advantage allowing physicians to treat breast cancer while reducing some of the side effects. But because treatments are tailored to the patient’s anatomy, we need to make sure that patients can reproduce their breath-hold in addition to their planned treatment position. Surface imaging allows us to accomplish this without the need for ionizing radiation, reducing the patient’s exposure to harmful radiation. And because we can keep the surface imaging

cameras on indefinitely, we’ve also been able to make improvements in the quality of treatment since we physicists are constantly analyzing the data and learning from it.

WM: WHAT ARE YOU MOST EXCITED ABOUT IN YOUR RESEARCH?

HA-H: There are many artificial intelligence (AI) tools being developed to make the radiation treatment workflow more efficient and robust. But implementing these tools into clinical use is challenging because sometimes they make things less efficient, or they create new error modes. I’m excited about learning how humans will interact with these tools and identifying ways to make the tools more useful in our field. In a sense, learning about how humans use AI will help us learn about the qualities, both good and bad, that make us human. WM

DANIEL M. HALPERIN is a medical oncologist on Winship’s gastrointestinal oncology team specialized in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). As a clinical investigator in Winship’s Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program, Halperin is dedicated to developing novel therapies for patients with NETs. He has played a leading role in clinical trials of immunotherapy and radioligands for patients with NETs. He also collaborates with laboratory and population scientists to deepen our understanding of the molecular basis and clinical presentation of NETs.

WM: YOU JOINED WINSHIP IN SEPTEMBER 2024. WHAT MADE YOU DECIDE TO COME TO WINSHIP FROM MD ANDERSON?

DH: There are so many wonderful things about Winship, and it is difficult to name just one. However, the opportunity to contribute to the ongoing growth and development of an organization of such amazing people was impossible to pass up. In my own area of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), there is a clear need for clinical care and research in this region, and there is a strong commitment from our leadership to develop into a destination center of excellence for patients with NETs. But more broadly, this is such an exciting time in the

organization. We are growing and learning on a daily basis, and it is so invigorating to be a part of that process.

WM: WHAT ARE YOU MOST EXCITED ABOUT IN YOUR RESEARCH RIGHT NOW?

DH: We are involved in several studies of agents at different points in their development cycle, and each is exciting in its own way. At the more advanced end of the spectrum, we have ongoing and oncoming clinical trials of more advanced radioligand therapies targeting the somatostatin receptor. The currently available agent has been a tremendous advancement for our patients, but there is substantial opportunity to improve the outcomes for those patients. We are also very excited to be involved in the early studies of a new cellular therapy for patients with NETs, which is an entirely new approach for our patients. It takes advantage of a new target, making it a potential option for patients who would not benefit from our current radioligands. Those patients are in particularly profound need of new options, so we are very excited to have something to offer.

WM: HOW WILL THIS RESEARCH BENEFIT PATIENTS WITH NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (NETs)?

DH: While we must always bear in mind that experimental therapies are by definition not yet known to provide benefit, offering and systematically evaluating new and innovative therapies will lead to more options in the future to further improve the lives of our patients. We are hopeful about the potential of the specific experimental agents that we are bringing into the clinic at Winship to reduce the burden of suffering for our patients, both here in Georgia and globally. However, regardless of the outcome of each specific trial, each completed study successfully moves us toward better lives for our patients. And our patients inspire us every day to keep working toward that reality. WM

BERYL MANNING-GEIST is a gynecologic oncologist and assistant professor in the Division of Gynecologic Oncology in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine. She specializes in treating patients with uterine, ovarian and cervical cancers. She practices at Winship Cancer Institute at Emory Midtown and is a member of Winship’s Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program.

WM: WHAT ARE YOU MOST EXCITED ABOUT IN THE AREA OF GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY RIGHT NOW?

BM-G: Honestly, it is such an exciting time for the field. First, the rapid advancements in targeted therapies and immunotherapies are revolutionizing how we treat gynecologic cancers. We're moving beyond traditional chemotherapy, offering patients more personalized and potentially less toxic options. It is incredibly rewarding to see firsthand how these innovative treatments can improve outcomes and quality of life for patients with ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer. Last week alone, we opened two clinical trials that will bring these targeted treatments to bedside for women with recurrent endometrial and ovarian cancer. We will soon be opening another clinical trial at Emory that I designed while at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center that replaces chemotherapy with targeted therapy at time of diagnosis in women with low-grade serous ovarian cancer, a less common, but aggressive, type of ovarian cancer that grows more slowly than high-grade ovarian cancer.

Beyond advances in targeted and immunotherapies for treatment, improved understanding of cancer genomics is opening up new avenues for early detection and prevention so that we can intercept cancer in its earliest stages to save lives. Our division recently opened a clinic for patients with inherited risks of gynecologic cancers, and we have started a large-scale biobanking project with the intention of designing an early detection test for ovarian cancer.

And finally, as a surgeon, I'm devoted to the continuous refinement of minimally invasive surgical techniques, including robotic surgery. These technological advancements allow us to perform complex procedures with greater precision, smaller incisions and faster recovery times for our patients.

WM: HOW HAS GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY CHANGED/IMPROVED?

BM-G: Gynecologic oncology has undergone a remarkable transformation in recent years. Perhaps the most significant change is the shift toward a more multidisciplinary and personalized approach to patient care. We now work much more closely with radiation oncologists, pathologists, geneticists and other specialists here at Emory who are truly leaders in the field. Every patient with gynecologic cancer who walks through our doors receives an individualized treatment plan designed by this

multidisciplinary team that is tailored to their needs and cancer characteristics. This collaborative approach has significantly improved outcomes.

WM: WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT FOR WOMEN?

BM-G: These advancements are profoundly important for women for several reasons. First and foremost, they offer hope. Hope for longer survival, improved quality of life and even the possibility of cure for cancers that were once considered almost universally fatal. The development of less invasive surgical techniques means women can recover faster and return to their normal lives sooner. The focus on personalized medicine means that treatments are becoming more effective and less toxic, that we are minimizing side effects and improving overall well-being. But beyond the individual benefits, these advancements are important for all women because they represent a broader shift towards prioritizing women's health. Investing in gynecologic oncology research and care sends a powerful message that women's health matters. It's about empowering women to take control of their health, knowing that they have access to the most cutting-edge treatments and the best possible care. Ultimately, we hope that continuing to move the needle on gynecologic cancer care gives women more time with their loved ones, allowing them to live full and healthy lives. WM

WEI ZHOU co-leads Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program. He is a professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, a Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Research Scholar and American Cancer Society Research Scholar.

WM: WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED ABOUT THE TUMOR SUPPRESSOR GENE SOX7 AND ITS ROLE IN CANCER?

WZ: The Sox7 story centers around the WNT signaling pathway, a network of proteins that transmit signals into cells, which is always activated in colon cancer through genetic changes in the APC or beta-catenin genes. When we began our work on prostate cancer, it was known that WNT signaling is activated, but genetic changes in these two genes were not found. We discovered the missing piece, Sox7, which physically interacts with betacatenin to normally suppress its function. In most colon cancers and half of prostate cancers, the expression of Sox7 is suppressed. Because there is no Sox7, betacatenin is overactivated, driving cancer development. Other laboratories have followed up on our work and demonstrated that Sox7’s function is suppressed in lung, breast, kidney and ovarian cancers. More recently, we discovered that another marker for prostate cancer, PSMA, is regulated by Sox7. Active Sox7 keeps PSMA levels low, but when Sox7 is silenced, PSMA levels surge, contributing to cancer progression. Our work suggests that restoring Sox7 function could offer a promising therapeutic approach for human cancers.

WM: WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO STUDY "MECHANISMS," AND HOW CAN THEY

WZ: Mechanisms are the details of how things work. For example, when discussing the mechanism of cell growth, you can envision it as controlling the speed of a car. The accelerator is the oncogene, and the brake is the tumor suppressor. They interact with many other car components to control the speed of that car. If any one of these components fails, you lose speed control, and uncontrolled cell growth is a hallmark of human cancer. We study mechanisms to figure out how everything works together, and more importantly, what went wrong in cancer. These understandings are essential for developing better cancer therapies. For example, if a type of cancer relies heavily on a particular abnormal onco-protein for survival, that protein becomes a potential Achilles’ heel, and we can develop drugs to inhibit its function. Different cancers, even within the

WEI ZHOU

same organ, can have different mechanisms. By understanding the specific mechanisms driving a cancer subtype, we can evaluate the most effective treatment, which is the idea behind personalized therapy.

WZ: Currently, we are most interested in sex differences in cancer development. It turns out that for most cancers, the incidence is higher in males than in females. There are many reasons for this difference, but we recently discovered that in smoking-related cancers with the loss of the LKB1 tumor suppressor gene, there is a twofold difference in incidence based on sex. In this specific case, the innate immune system in females is responsible for the suppression of this cancer subtype. The innate immune system is the body's first line of defense against pathogens or cancer because it can detect these entities without prior exposure. We are currently studying this immune-based mechanism in detail so that we can develop a new treatment strategy for this cancer subtype. WM

Winship leads the way in multiple myeloma advances

By Stacia Pelletier • Illustration by Paul Tong

When executive assistant

Danielle Spann began feeling severe pain in her lower back and hips, she assumed it was just the price of getting in shape.

“I was working out a great deal at the time,” she says. She did what most of us would do: tried to ignore it.

Two months passed, but the pain didn’t subside. She visited an orthopedist, who ordered X-rays. The images revealed a mass on her spine, and the orthopedist referred

her to Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

After a series of tests, Spann learned she had multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that develops in plasma cells within the bone marrow. She would need chemotherapy, a stem cell transplant and other medications. Even with treatment, her prognosis was grim: doctors told her she had about five years to live.

“That was in 2011,” Spann says. “And here I am now.”

The story of multiple myeloma treatment at Winship is one of perseverance and partnerships.

Advances made by the Winship myeloma team should bring hope to anyone diagnosed with —or living with—the condition today. Over the past two decades, these physicians and researchers have helped transform multiple myeloma from a death sentence into a manageable condition. More patients are living well past their initial prognosis—and not just surviving but thriving.

“I’m doing anything and everything I can to stay on this earth as long as possible,” Spann says. “Where I am today, it’s because of Emory. It’s because of my Winship doctors.”

“THIS TOO SHALL PASS”

Spann’s 15-year cancer experience offers a window into the challenges many multiple myeloma patients face. Soon after her diagnosis, she sneezed and fractured a vertebra, necessitating emergency surgery. “That’s how weak the myeloma had made my bones,” she says. She began receiving chemotherapy and steroids on an innovative clinical trial, but the disease progressed despite using modern drugs. She needed an autologous stem cell transplant, where her own stem cells were harvested before chemotherapy, frozen and then infused back into her body after chemotherapy—an arduous process that required a 28-day hospital stay.

Although she felt better afterward, her myeloma numbers had not improved as much as her doctors had hoped. Doctors told her she needed a second, “tandem,” stem cell transplant. Spann returned to the hospital for another 15 days.

Everything about that second transplant was grueling, she recalls. “I kept telling myself, ‘This too shall pass,’” Spann says. She vomited almost constantly—she couldn’t hear the food cart rolling down the hospital hallway without becoming nauseated. She developed a skin reaction that made receiving visitors difficult. “This too

shall pass” has since become her life motto. “Whatever it is, whatever the difficulty, it’s temporary,” she says. “How I’m feeling right now, it’s not going to be forever.”

Take what Spann was experiencing and multiply it by 700 to 800 people: That’s how many new cases of multiple myeloma Winship’s myeloma clinic sees each year.

Multiple myeloma disproportionately affects Black people—30% to 40% of Winship’s patients with multiple myeloma are Black—and they have approximately twice the incidence and mortality rates as white people. Since Winship serves a large African American population, the myeloma team manages one of the largest caseloads in the country.

“From the 1970s through the early 2000s, survival rates were just three years on average for these patients,” says Ajay K. Nooka, Winship’s associate director of clinical research and director of the Myeloma Program in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “We needed to do something different. We needed to rethink almost everything.”

Sagar Lonial is Winship’s chief medical officer, the Anne and Bernard Gray Family Chair in Cancer and

professor and chair in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Together with Nooka and other Winship physicians and researchers, Lonial spearheaded a comprehensive initiative to help prolong the lives of patients with multiple myeloma. Early on, the team had one overarching objective: Get out in front of the cancer.

“We didn’t want to try a treatment and then just wait to see what happened,” Lonial says. “We needed a long-term plan: treatment regimens that would maximize how long the disease could be controlled or remain in remission. We had to start thinking five or 10 years ahead for each patient. That was the way to stay ahead of this cancer.”

Two new medications tested in clinical trials at Winship helped make this planning more than a pipe dream: bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor introduced in 2003, and lenalidomide, an immune modulating drug introduced three years later, in 2006.

Patients saw marked improvements when these new therapies were deployed as combination treatments along with a steroid. Even those with relapsing or refractory multiple myeloma, which is notoriously difficult to treat, responded positively. “We were one of the pioneers here,”

Nooka says. “Winship started offering these drugs to patients very early as frontline treatments.”

Since then, the number of new medications for multiple myeloma has risen sharply, from just two in 2006 to 13 and counting today. Every single myeloma drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the last two decades has been tested in clinical trials at Winship. And it’s not just the individual drug that matters: it’s their combination.

“Combination therapy is key,” says Lonial. “It allows us to hit the disease from multiple different angles.” Using a single medication until it no longer works isn’t helpful. “That approach just induces drug resistance,” he says. To combat this challenge, the Winship team has tested a variety of combination strategies to put the disease into remission, and developed lower-intensity treatments that can serve as maintenance therapy for the long term.

Following her tandem stem cell transplant, Spann started on one of those combination treatments, a drug cocktail that, in her words, “kept my numbers down until it didn’t.” Her myeloma was particularly aggressive, and

A timeline of U.S. Food and Drug Administration multiple myeloma drug approvals/withdrawals from 2003-2023

CLASS/MECHANISM OF ACTION

Proteasome inhibitor (PI)

Immunomodulatory drug (IMID)

Monoclonal antibody (mAb)

Antibody drug conjugate (ADC)

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T)

Bispecific antibody (bsAb)

Other

* Approval withdrawn

her Winship physicians tried several combinations over the next few years, seeking the mix that would send the cancer into remission. Some of the medications she received came through Winship’s clinical trials. Spann remembers one treatment working so well, and for so long, that she received permission to stay on it after the study ended. “That formula worked for me for a long time,” she says.

Today, the latest therapeutic options for multiple myeloma include bispecific antibodies, which bridge tumor and immune cells to help recruit the patient’s immune system to fight the cancer, and CAR T-cell therapy, which engineers the patient’s T cells, a type of white blood cell, to recognize and attack myeloma cells. They potentially help to achieve and extend deep remission of the disease over longer periods. The myeloma team at Winship has helped lead both developments, offering a clinical trial of a bispecific antibody during the COVID-19 pandemic and conducting close to 100 CAR T-cell procedures in Winship patients just in the last year. Those living with a multiple

myeloma diagnosis are eager for what’s coming down the research pipeline. “In some health care settings, people are skeptical about clinical trials,” Nooka says. “But our patients are asking to join these studies. In a trial of this kind, there are no sugar pills; you’re either getting the regular standard of care or the new treatment. There’s no downside. Patients want to be part of it.”

With research momentum on their side, Winship investigators are turning to two new frontiers in the progress against multiple myeloma: prevention and cure.

Smoldering myeloma is a precursor condition that leads to multiple myeloma in 10% to 15% of those diagnosed. The condition doesn’t cause noticeable symptoms and is often caught only after an abnormality shows up in routine bloodwork. In the past, physicians didn’t treat smoldering myeloma; they simply monitored the patient to see if cancer developed. Now, however, they’re preparing to intervene earlier. If clinicians can intercept the

disease during this “smoldering” stage, they could prevent multiple myeloma from ever developing.

“If you intervene early enough and prevent the organ damage, the fractures and the kidney failure that multiple myeloma can cause, that’s a huge win for patients,” Lonial says.

For those who have been living with this cancer for 10 or 15 years, another transformation could be on the horizon: stopping treatment altogether. The new classes of drugs are so effective at controlling multiple myeloma that Winship researchers are now talking about the prospect of ending maintenance therapy for some people—though they caution that such discussion is still very preliminary.

“One of the longstanding tenets of therapy in myeloma is the principle of continuous or maintenance treatment,” says Lonial. “Until now, patients have always been on some sort of low-dose therapy, even when they’re in remission.” Think of it like taking medication for high blood pressure: Your blood pressure might drop to normal levels, but that’s

Daratumumab (2015)

Panobinostat (2015) *

Ixazomib (2015)

Elotuzumab (2015)

Selinexor (2019)

Isatuximab (2020)

Belantamab mafodotin (2020) *

Idecabtagene vicleucel (2021)

Melphalan flufenamide (2021) *

Daratumumab hyaluronidase (2020)

Teclistamab (2022)

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (2022)

Elrantamab (2023)

Talquetamab (2023)

because you’re taking the drug, so you stay on it. A similar assumption has guided the treatment of multiple myeloma—until very recently.

Today, Winship investigators are working to combine multiple immune therapies, deliver them to the patient over a short period of time, stop the cancer in its tracks—and then stop treatment. Lonial and his colleagues are in the early stages of concept development for a possible clinical trial exploring this potential “cure.”

Even five years ago, such talk might have been considered farfetched. Not anymore.

“There’s a possibility that some patients could come off these drugs and not need to stay on them forever,” says Nooka.

As for Spann, she’s on another combination regimen these days, and it’s working. When she had her bloodwork done this past summer, she was declared to have a “confirmed complete response”—no myeloma cells detected in her urine, bone

marrow or blood. She still comes in once a month for treatment, but she has also started volunteering at the clinic, talking with patients newly diagnosed with myeloma and offering encouragement. “I’m not the first person, nor will I be the last, to have a multiple myeloma diagnosis,” she says. “I want to let others know they’re not alone, and there’s hope.”

Winship now has close to 5,000 patients in the myeloma clinic—and counting. The increased numbers are because those diagnosed are living so much longer. That expanding timeframe fosters strong bonds between a patient and their care team. “Dr. Nooka is like family to me,” Spann says.

Lonial recently took training fellows on rounds through the clinic. In a single day, they saw a 15-year multiple myeloma survivor, a 12-year survivor and an 11-year survivor, all living full lives. “It was a good day,” Lonial says.

Nooka and Lonial both credit Winship’s leaders with investing in an ecosystem that supports

clinical trials. They’re grateful for partnerships with basic scientists across Emory who analyze tissue samples and help determine which drugs will best support remission. But it’s the relationships with patients, they say, that have the most enduring impact.

“It’s a multi-pronged partnership,” Lonial says. “We’re working with a very strong internal team, but we’re also partnering with other myeloma programs, with industry and— importantly—with patients and patient advocacy groups.”

Spann agrees. In her spare time, she travels to multiple myeloma conferences to share her story. She tells others with the disease to stay focused on what’s important, to have a long-term goal and strive for it.

“I’m here because of my faith and because of Dr. Nooka,” she says. “And I’m an advocate for Emory. I would not give these doctors up for anything.” WM

STACIA PELLETIER, novelist and freelance writer, is a former senior director of development for the Woodruff Health Sciences Center.

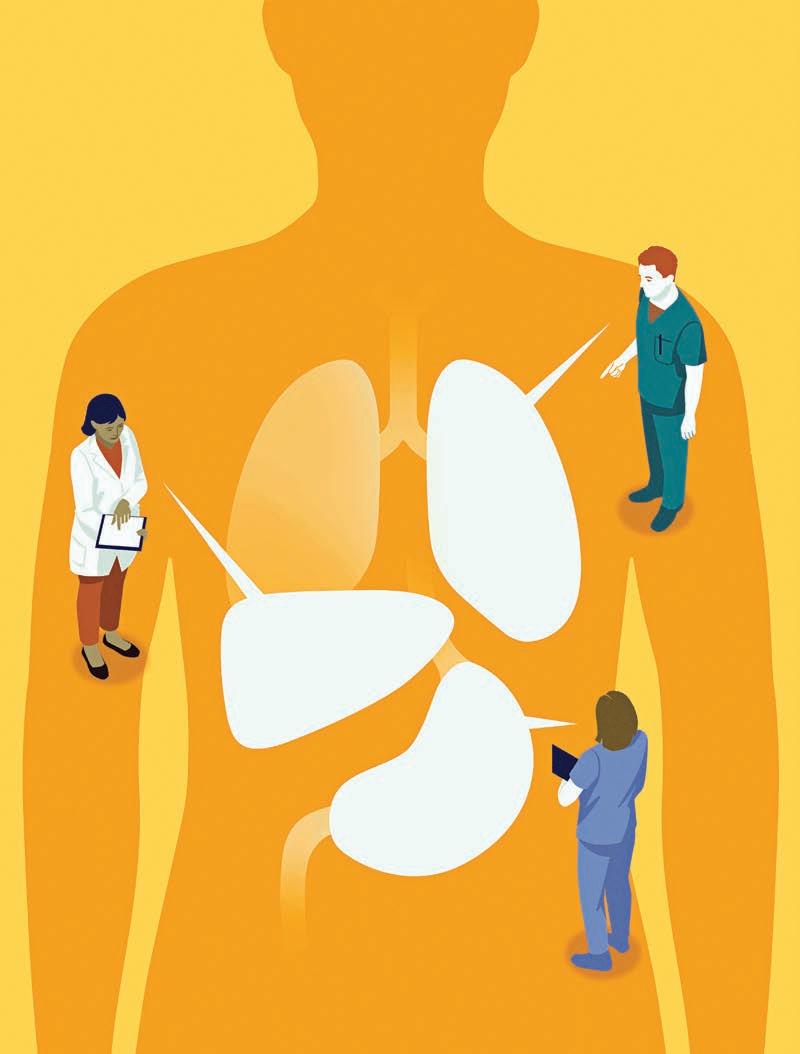

A second opinion could make all the difference in the experience and the outcomes

By Eric Butterman • Illustration by Joey Guidone

Phyllis Hollowell wasn’t about to leave her life to chance. “As soon as I was told I had cancer,” she says, “I just wanted to do whatever it took to live.” Although she respected the medical team that gave her the diagnosis, “whatever it took” included getting a second opinion.

“When I went to Winship, they confirmed my diagnosis and gave me a plan,” Hollowell says. “This gave me more doctors behind me and gave me more confidence because I wanted to get to what needed to be done right away.”

With that first diagnosis, most patients generally don’t know much about cancer. Then suddenly they are expected to make big decisions, fast. It’s easy to feel confused, overwhelmed and emotionally drained. After working up the strength and courage to face the news and make sense of unfamiliar medical terms, the idea of starting over to get a second opinion may seem exhausting. For many, the path of least resistance is simply to accept the first opinion without seeking another.

Cancer experts strongly recommend that you need a second opinion when it comes to cancer care. From receiving a more accurate diagnosis or, even in rare cases, learning that you don’t even have cancer at all, to identifying a better treatment plan—there are many important reasons to seek another perspective and additional insight in what could be a matter of life and death.

Often, doctors agree on a diagnosis, but not always. Still, many patients hesitate to get a second opinion, sometimes out of fear that the news might be worse. While that’s possible, the unknown could turn out to be their greatest fear.

“The diagnosis and management of a patient is not just dependent on what a pathology report says,” according to Sagar Lonial, chief medical officer at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair and professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. “There are many other factors that go into designing or creating a treatment plan beyond the pathology report,” he says.

Lonial says there is a real advantage in seeking a second opinion at a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center like Winship. “What coming to an NCI-designated cancer center allows you to do is to be seen at a place that really focuses on the subtleties that may not be as simple as just a pathology report giving you a certain treatment approach,” he says.

Lonial says those subtleties include understanding the potential impact of genetics or gene profiling on treatment selection, patient functional status, performance status, co-morbidities and treatment approaches.

It’s possible to receive an incorrect diagnosis—and when that happens, it can significantly impact the quality of care and a patient’s outcome.

Misdiagnoses can result from limited access to advanced technology, or lack of experience with a specific rare cancer type, says Suresh S. Ramalingam, Winship’s executive director and the Roberto C. Goizueta Chair in Cancer Research at Emory University School of Medicine. “If a patient, say, has breast cancer and has initially been seen by a general oncologist, having a second opinion from a breast cancer specialist will add to the care of that patient.” He adds, “Sometimes it may not change what is being done but it helps make sure that everything that needs to be done to maximize the possibility of a good outcome has been done.”

That’s another advantage of getting a second opinion from an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center: access to physicians with experience and expertise in diagnosing and treating your type of cancer, including rare and complex cancers.

It’s not uncommon for a diagnosis to be very different in a second opinion—sometimes dramatically different.

“Patients have been sent to me with a cancer diagnosis who didn’t have cancer,” Lonial says. “I won’t say that happens every week in clinic, but it certainly happens

a couple times a year in my group. There are other times when the diagnosis is subtly changed such that it impacts the treatment proposed for a diagnosis that wasn’t exactly correct. With a little more time and effort spent on reviewing the diagnosis, we made a different diagnosis that changed the treatment approach for a given patient. That’s not uncommon at a center like ours.”

Getting a second opinion at an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center also offers patients more treatment options because NCI-designated centers provide —and pioneer—the latest innovations in treatment, including clinical trials of novel therapies.

Patients sometimes worry that their oncologist will be insulted or feel a lack of trust if they go for a second opinion. But in many cases they need not worry.

“I think if you’re dealing with a generalist who sees a lot of different cancers, I can count on one hand the number of generalists that have not wanted to take the feedback I’m giving as a specialist in terms of management of that disease,” Lonial says. “I think from a patient perspective, it’s just building a bigger team.”

Lonial says that if your physician is offended by your going to a specialized center and getting a second

SURESH S. RAMALINGAM

opinion, “you almost need to wonder whether that physician is really the optimal partner for you. Because if they’re not willing to learn and listen, then are they really the best doctor to take care of you?”

This brings up another misconception about second opinions: that it’s about choosing between doctors. It actually doesn’t always result in an either/or scenario. Sometimes the second opinion physician brings an approach to the table which complements the initial physician, and they can then partner together to help the patient, rather than selecting one over the other.

“As a surgeon, you will have to pick between us for the surgery,” says surgical oncologist Maria C. Russell, Winship’s chief quality officer and the Wadley R. Glenn Chair of Surgery for Academic Programs at Emory University School of Medicine. “But there have been times when I’m providing the expert opinion, and the patient can work with their local medical team but with me guiding them.” She adds, “Collaboration can work, and the great thing is most people in medicine are focused on the optimal result, not on who is in the lead. The care of the patient should come first.”

A second opinion isn’t just about hearing a different medical perspective—it’s also an opportunity to assess your own comfort level with the physician. Does this doctor communicate clearly? Do they make you feel heard and supported? “Many people don’t consider this aspect of a second opinion, but you need to feel comfortable with your oncologist, beyond just their treatment plan,” Russell says. “You are starting a long process of care, and you don’t want to be with the wrong partner.”

This isn’t just a time to assess bedside manner, but also communication skills. After all, this person will not only be your physician but your guide through a medical world that can be confusing.

“It’s important because we want the person seeking care to feel like they understand what’s being discussed— even when the topics are complex. And you want a doctor who won’t get frustrated if you need something explained more than once,” says Ticiana Leal, leader of Winship’s lung cancer disease team and director of the Thoracic Medical Oncology Program in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University

“Collaboration can work, and the great thing is most people in medicine are focused on the optimal result, not on who is in the lead. The care of the patient should come first.”

—MARIA C. RUSSELL

School of Medicine. “You already may feel apprehensive when it comes to what treatments you have to do—you don’t want more confusion adding to this feeling.”

The second opinion has one more vital strength: it can put you at ease. Patients often worry there has been a mistake in their diagnosis. Having it confirmed by a second opinion can give you greater confidence in your oncologist and path forward.

“Many times the second opinion reveals that your physician has it right,” Leal says. “Just hearing that can take you from tense to ready to take things on. That can be worth so much in terms of the process.”

Phyllis Hollowell, who went on to have surgery at Winship, is adamant about going for that extra step. “Not getting a second opinion is gambling with your health,” she says. “It just isn’t worth it.” WM

ERIC BUTTERMAN has written for more than 50 publications, including Glamour and Men's Journal.

Asecond opinion doesn’t always mean going elsewhere. At Winship, for example, doctors come together in multidisciplinary tumor board meetings to provide second—and sometimes third or fourth—opinions. The tumor board meeting is a conference often focused on the more complicated cancer cases, says Maria C. Russell, Winship’s chief quality officer, and a hallmark of NCI-designated cancer centers.

“A group of physicians from multiple medical disciplines, including surgery, medical oncology, radiation oncology and radiology, with experience in treating the patient’s condition together review the patient’s medical files and then discuss treatment options,” Russell explains. “Everyone has an equal voice, regardless of years of experience, with value coming from each of them having different points of view. We give our thoughts on what is appropriate treatment and sequencing of treatment for each patient.”

Russell says it can be less confusing for patients by getting the expert opinions of all attending the tumor board meeting. “This way, they have a comprehensive plan before starting on treatment,” she says. “This is one of the key advantages of our multidisciplinary institution.” WM

Winship researchers share expertise and learn from global colleagues

By John-Manuel Andriote • Illustration by Alex Foster

Cancer wears different faces around the world. In some regions, it’s driven by infectious agents such as human papilloma virus (HPV); in others, by behaviors such as cigarette smoking or exposure to environmental hazards like polluted air or water. Wherever it appears, and in whatever form, cancer disrupts lives.

Because cancer is a global challenge, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University is part of an international network of doctors and scientists researching and working to advance knowledge and

improve care for people living with cancer here in the United States and around the world.

“What we learn here is applicable to people in other parts of the world, and what we learn in other parts of the world is applicable to patients we serve in our communities here in Georgia,” says Suresh S. Ramalingam, Winship’s executive director and the Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair for Cancer Research at Emory University School of Medicine. He notes that the interactions of Winship’s researchers with their counterparts in other countries “inform our research and our ability to adapt in a rapidly changing world in every single way.”

Here are a few examples of Winship’s work around the world where it is actively involved in both sharing expertise and increasing its own understanding of the most effective ways to detect, diagnose, prevent, treat and live beyond cancer.

“Smoke-Free Homes: Some Things are Better Outside” is an evidence-based program developed at Emory and included on the National Cancer Institute’s list of evidence-based cancer control programs. The intervention consists of four components: three mailings of educational print materials, including a toolkit for creating a smoke-free home and one coaching call designed to help participants create a smokefree home using the five steps outlined in the print materials.

Michelle C. Kegler, director of the Emory Prevention Research Center, professor in the Department of Behavioral, Social and Health Education Sciences at Rollins School of Public Health of Emory University and a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program, was centrally involved in developing “Smoke-Free Homes.” In the years since its inception, the intervention has been adapted in a number of U.S. states and several countries to make it relevant in different cultures.

Kegler says partnerships with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the country of Georgia and in Armenia with the National Ministry of Health and the American University of Armenia, allowed her and her team to adapt the “Smoke-Free Homes” campaign for those countries. She says, “They conducted focus groups with people who smoke and people who live with someone who smokes, and changed out the pictures, translated them into their languages and then got local reactions to the intervention materials.”

Making the materials culturally relevant included adjustments such as adding a father to the photos that had depicted a mother and child wherein the mother was a smoker. In those countries, men smoke at 10 times the rate of women and there isn’t strong awareness about secondhand smoke. Because fewer people have household pets, they switched the images of a little boy and a dog in the materials—showing the dog peeing on a couch (best done outside)—to a boy playing with a soccer ball, also best done outside.

“Smoke-Free Homes” has been adapted for use in Brazil and Spain, as well as for several subpopulations within the U.S. Kegler says, “We’re working with tribes here in the United States, in the Dakotas and Michigan, where we’re doing almost the same process of adapting the intervention for the local context and then testing it.” For example, the images in the materials that had featured a young African American child weren’t relevant for the tribal communities. It also required a sensitivity to the tribes’ traditional uses of tobacco.

Kegler has been contacted by colleagues within the U.S. who want to adapt “SmokeFree Homes” for ethnic subpopulations in their communities. One in Minnesota wants to adopt the program for Somalis living in the state. Another colleague in New York City wants to adopt it for Chinese Americans living there. Still another in Texas is trying it out in Spanish. Right here in the state of Georgia, a partnership with Georgia State University is exploring the possibility of adapting the program to fit in their nationally disseminated parenting program for families interacting with child protective services.

Helping people to create smoke-free homes is important for cancer prevention. Kegler says, “I like to do research that focuses on the home as a setting because people spend so much time in their homes. So, the better the home is structured to promote health, the more likely you are to engage in healthy behaviors.”

The main outcome of a collaboration with India’s Center for Chronic Disease Control, in Delhi, was establishing an infrastructure for a long-term series of studies, according to Michael Goodman, a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program and a professor in the Department of Epidemiology at Rollins School of Public Health of Emory University. One key step involved developing a solution to a major challenge: India’s lack of unique personal identifiers for each citizen—such as Social Security numbers in the U.S.—which makes linking health data to individuals more difficult.

Because Indian names may be repetitive or only contain first names or an initial, Goodman says it’s necessary to “triangulate multiple variables,” such as a phone number, address, year of birth or sometimes even a relative’s name. “If you are trying to link a woman’s record to a cancer registry record, you may want to also consider her husband’s name if that is available. It turns out to be a big job, but we were able to accomplish it with reasonable success.”

Another challenge is stigma related to cancer, which is “a big, big issue” in India, Goodman says. “For some reason there is a shame and motivation for people to hide their diagnosis. Because of that, there’s a delay in going to see the doctor. It has nothing to do with the ability to screen or the availability of screening or even availability of treatment. The barrier is that people don’t want their neighbors to know. In some parts of the country, it may affect the likelihood of their child getting married.” Goodman says this kind of stigma—the belief that cancer is caused by past sins or misbehaviors—is unfamiliar in the U.S.

To date, Goodman and his fellow researchers have only gotten as far as describing the problem. But, he says, “That in and of itself was a very important contribution because now our colleagues in India know that this is a problem of big magnitude that prevents people from getting treatment.”

THE IMMUNE SYSTEM’S ROLE

IN HPV-CAUSED CERVICAL CANCER

Because HPV is common throughout the world,

collaborations and partnerships are essential to address the virus’s risks and potential dangers. HPV is most often transmitted through sexual contact, though some of the more than 200 types of HPV can be passed through skin contact. The majority of people who have sex will be exposed to HPV at some point in their lives. Most people will not experience any symptoms, and their bodies will eventually clear the virus.

But some HPV types can cause genital warts, cervical cancer, anal cancer and other types of cancer, particularly cancers of the head and neck. Although there is no cure for HPV, there is a vaccine to prevent HPV-related cancers and treatments for the conditions caused by HPV, including genital wart removal (with surgery, freezing or medication) and cancer therapies.

After more than two decades, one such collaboration in India continues to generate new insights into HPVrelated cancers that have far-reaching value.

“We were very successful in making a lot of new insights in terms of the immune responses generated in people who have head and neck cancer,” says Rafi Ahmed, co-leader of Winship’s Cancer Immunology Research Program, director of the Emory Vaccine Center and professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Emory University School of Medicine. He says the team’s observations in head and neck cancer “led to the obvious question” of whether these immune responses are different from or similar to those in women who have HPV cervical cancer.

Ahmed says that India has the world’s largest number of cervical cancer cases. He explains that in the U.S., HPV cervical cancer has significantly decreased thanks to women receiving regular Pap smears and the HPV vaccine. “But in most parts of the world, the HPV vaccine coverage is very low, and the more economically lower-class women are not getting regular checkups.” For this reason, cervical cancer is “one of the worst cancers for women in low- and middle-income countries.”

After working for many years on infectious diseases with the International Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), one of India’s premier biomedical institutes, Ahmed and his team are now working with the

institute’s obstetrics-gynecology department to look at three cohorts of women. For the new study they will recruit about 60 to 80 women with cervical cancer, 60 to 80 women who are HPV-positive and have pre-invasive lesions and a larger group of about 200 women who are HPV-positive for one of the high-risk HPV genotypes yet have no symptoms.

“We’ll recruit them and then we will enroll these women in our cohort and monitor their immune responses and then see if some of them actually control the infection or not,” Ahmed says. The researchers will seek to find the right therapeutic vaccination regimen for the women with pre-invasive cancer and study why and how women whose immune systems can clear the high-risk virus from their body are able to do so. “The knowledge that we get from the cervical cancer studies could be of value for many other things that could be applicable here in the U.S.,” Ahmed says.

Lisa Flowers, director of Colposcopy Services at Grady Cancer Center, professor in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine and member of Winship’s Discovery and

Developmental Therapeutics Research Program, recently returned from Panama, where she has worked with colleagues for the past seven years to address cervical cancer among indigenous women.

During her latest visit, Flowers saw 800 women in two days, screening them for HPV and cervical cancer with Pap smears and follow-up colposcopy for those whose Pap test indicated possible HPV infection, precancerous or cancerous changes in the cervix or other abnormalities. Colposcopy is a procedure involving a magnifying device called a colposcope to visualize the cervix, the lower part of the uterus, for abnormalities and take biopsies if necessary.

Most of the women Flowers examined with colposcopy because their Pap test indicated some type of abnormality— such as inflammation—had no disease. Flowers says, “It really showed that Pap smear screening is not ideal in certain populations, and that the best thing to do is to actually do primary HPV testing.” Primary HPV testing screens for the presence of high-risk HPV types that can lead to cervical cancer. It can detect HPV infections sooner and is more sensitive than traditional Pap smear screening at detecting precancerous cervical lesions.

Cervical cancer is considered an “AIDS -defining” illness

THE LOCATIONS & THE TYPES OF CANCER WINSHIP IS ADDRESSING

Kenya, Nigeria

Cervical cancer in HIV+ women (cervical cancer is an “AIDS-defining” illness in women living with HIV)

Armenia, Georgia (country)

Cigarette smoking cessation

Barcelona, Brazil, and in the US (working with Native American tribes in North and South Dakota; Minnesota; California)

Cigarette smoking cessation

India

Head and neck cancer in men (caused by chewing tobacco and the betel nut, a popular ingredient in the preparation of the chewed mixture "paan"); cervical cancer (caused by HPV) and gall bladder cancer in women

Panama HPV-caused cervical cancer in HIV+ women

in women who are living with HIV because they are at higher risk of developing it, and it can indicate an advanced stage of HIV disease (AIDS). For this reason, Flowers also is working with a network of 15 clinics in Nigeria, each of which is screening 100 women with HIV using self-collection for primary HPV testing.

Flowers explains that the women are taught how to do self-collection of specimens by “Mentor Mothers,” a nationwide peer-based support network of women living with HIV who partner with new mothers recently diagnosed with HIV to improve the women’s access and retention in HIV care. She says self-collection involves “using a swab in their vagina and putting it in a solution for primary HPV testing to see if they need the next diagnostic test—colposcopy—to detect for HPV.”

If they end up being positive for high-risk, cancercausing HPV types, Flowers says, “we are doing what we call digital colposcopy on their cervix and taking biopsies of areas that are abnormal. If we don’t find any abnormal areas, we are taking quadrant biopsies to be sure. If we see areas that are white on their cervix that are suspicious for pre-cancer, they get automatic treatment that day with either ablation (removal of

tissue) or, if we think they may have a cancer, referral to an oncologist.” She adds, “We estimate there’s about a 30% to 40% positive rate of high-risk HPV.”

HPV-caused cervical cancer is also a focus for Michael H. Chung, professor of medicine, global health and epidemiology at Emory and associate director of the Emory Global Health Institute.

For more than two decades, Chung has focused on infectious diseases and HIV research in Kenya and is currently working on research funded by the National Cancer Institute to improve cervical cancer screening and treatment in the country. He is leading several implementation science studies and clinical trials to determine how best to support busy government clinics to improve their cervical cancer screening rates and diagnostic accuracy. He and his colleagues are also determining how to treat pre-cancerous cervical lesions identified by HPV testing using thermal ablation, an inexpensive method that is widely available in resourcelimited settings as a battery-operated device that can be handled by nurses. This research brings Emory together in partnership with some of the best research and medical institutions in Kenya including the University of Nairobi,

Lisa Flowers shares her enthusiasm about a phone app developed in Nigeria that she says could make an important difference right here in the rural areas of Georgia. What Flowers calls the “digital colposcopy” uses a smartphone to provide the magnification needed to examine the cervix for abnormalities—and to capture photos. Colposcopy is a procedure that uses a magnifying device called a colposcope to examine the cervix for abnormalities and guide biopsies, if necessary. Flowers explains that digital colposcopy allows clinicians to mark biopsy sites, record their impressions and upload HPV test results and pathology images directly into the patient’s medical records.

Flowers says using the app allows some patients to be treated on the same day or brought back quickly if their condition appears to have worsened. Then they are monitored with primary HPV testing to confirm whether their disease is resolved.

“We realize that in rural Georgia there aren’t many clinicians trained to perform colposcopy or deliver treatment,” Flowers says. After applying vinegar to highlight abnormal areas of the cervix, clinicians can take biopsies or treat the area using thermal ablation—a handheld device that uses heat to destroy abnormal cells on the cervix. She says the procedure is welltolerated, and the most patients need for discomfort is ibuprofen.

All this data goes into the app and the

Kenyatta National Hospital, Coptic Hospital, Kenya Medical Research Institute, and Aga Khan University.

Chung says there are methods to improve cervical cancer screening in Kenya that could potentially be used to improve prevention efforts in the state of Georgia as well. Incidence of cervical cancer here is 8 per 100,000 women-years, which is above the target of 4 identified by the World Health Organization as needed to eliminate cervical cancer. Certain groups in Georgia also appear to be at higher risk including Black women, who are more likely to die from cervical cancer than white women, and Korean American women who are less likely to have been screened with a Pap smear.

Chung says that using clinic navigators to help patients find their way from screening to treatment, apps on phones to facilitate communication between health providers and patients and inform them of their test results and implementing HPV self-testing to simplify screening are all being tested in Kenya to increase access to cervical cancer screening. He says these methods could be used in Georgia, too, “particularly in rural areas where there is limited access to specialized care and among groups who encounter greater barriers to screening.” With colleagues at Emory's Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Chung is exploring how to examine the implementation of these methods locally

in Atlanta and has invited his research colleagues from the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta National Hospital to visit Winship Cancer Institute and share their best practices.

Clearly the partnerships that support crosstalk and collaboration between major research institutions like Emory University and the cancer and public health institutes in low- and middle-income countries offer many opportunities for “bidirectional” learning. Most importantly, they provide quantifiable benefits for the people of Georgia and beyond who count on Winship to provide world-class care and treatment for themselves and their loved ones dealing with cancer.

Ramalingam says, “Winship researchers who are leveraging the knowledge that exists here in collaborative opportunities in various parts of the world are directly helping to reduce the burden of cancer.” He adds, “This aligns with our growing stature as not just a nationally prominent cancer center, but as part of an internationally recognized research and clinical enterprise here at Emory. Emory University has a long track record of addressing global health problems. So, what Winship is doing is in keeping with the true tradition of our academic aspirations.”

WM

JOHN-MANUEL ANDRIOTE, an author and seasoned health/medical journalist, is Winship’s senior writer and editor of Winship Magazine.

patient’s medical record and can be shared with a gynecologist, either in real time or later, who can determine whether to treat the patient or not based on the images and data held in the app. “It will be a teaching tool because all these cases are maintained within the cloud, so that clinicians get better and better,” Flowers says.

A colposcope is expensive, limiting its availability and use in resource-limited countries and areas of Georgia itself.

Flowers says, “Having the app and the phone to be able to take the images where we can guide them and stay in communication with them, is a way by which we can empower frontline care teams in rural Georgia just by using an app that’s been created in Nigeria.” WM

Winship offers clinical trials and leadingedge care as regional “powerhouse” in the field

After Dianne Sacks was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at her local hospital in late 2021, she proceeded through standard treatments, surgery and chemotherapy.

“I seemed to respond pretty quickly to the chemotherapy,” she says. But after six months, her tumor markers began to rise again, signaling the need for something beyond the standard of care.

“My doctors didn't have much confidence in the next step and thought that I might benefit from joining a clinical trial,” Sacks, now 78, recalls. “That’s how we ended up at Emory. My brother, who’s at the University of Texas at Houston, found out about Dr. Modesitt from folks at MD Anderson, and he referred me to her.” Winship gynecologic oncologist Susan C. Modesitt is professor and chair in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

Since entering Modesitt’s care, Sacks has enrolled in two nationwide, Phase 3 clinical trials seeking to discover treatments for “platinum-resistant” ovarian cancer, which evades standard interventions. Both trials initially showed promise for Sacks, but after her disease progressed, her trial therapies ended.

“It feels good to have access to clinical trials, especially under wise eyes like Dr. Modesitt’s,” Sacks says. “Winship has more tools in the tool chest.”

Modesitt, who is also the editor-in-chief of the journal Gynecologic Oncology Reports, joined Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University in 2022. Her task: turn a small gynecologic cancer program into a regional research powerhouse. She is well on her way, with an expanded faculty, multiple clinical trials and a high-risk comprehensive care center all newly—or nearly—at fruition.

“We started off with four faculty. We are up to seven. We started with one clinical trial. We are up to 15 or 20,” Modesitt says. Some of those trials are led by in-house faculty; others are nationwide studies with enrollment sites at Winship, like the two that Sacks was able to join.

Modesitt also oversaw the start of a fellowship program accredited by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Now in its second year, the fellowship program attracts young gynecologic oncologists looking to bolster their research and clinical skills under the leadership of Winship gynecologic oncologist Sarah Dilley, an assistant professor in the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine.

“I’m collaborating with a lot of other physicians, pharmacists and other training programs to make sure my fellows are getting exposed to all different aspects of oncology,” Dilley says. The first accepted fellow developed a study, now funded and enrolling patients, looking at preventing neuropathy, the painful nerve damage that’s a common chemotherapy side effect.

Modesitt says her goal is to make Winship the national leader in gynecologic cancer treatments and innovation, while bolstering the care available to the diverse, historically underserved population in the Atlanta metro area and the southeast more broadly.

“It’s all kind of coming together,” she says.

Building up Winship as a prominent site for gynecologic cancer clinical trials enables more patients to easily and conveniently participate in potentially lifesaving studies, without the disruption

of traveling to major research hubs.

“There’s a real energy and excitement around bringing that innovation to a different patient population, to people who are not necessarily in Boston or New York,” says Winship gynecologic oncologist

Beryl Manning-Geist, an Emory medical school Woodruff Scholar alumna whom Modesitt recruited back after ManningGeist's advanced training at Harvard and Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Manning-Geist, an assistant professor in the Division of Gynecologic Oncology within the medical school’s Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, is now working on opening a secondary site for a clinical trial she helped start at Sloan Kettering, bringing her work home to Winship.

The trial takes a precision medicine approach to low-grade serous ovarian cancer, a rare, mostly chemo-resistant form of the disease that tends to occur disproportionately in younger patients. Although researchers know the standard treatment lacks clinical efficacy, patients are often subjected to multiple rounds of chemotherapy before becoming eligible to enroll in clinical trials for other options.

That is, patients are subjected to punishing rounds of chemo even though doctors know it’s unlikely to help them. Manning-Geist’s trial skips right to the experimental therapies.

“We used these sledgehammers when maybe we could use scalpels,” she says of using chemotherapy versus more targeted interventions.

For platinum-resistant ovarian cancers—cases

where multiple ‘sledgehammers’ have failed—researchers are exploring new strategies. Namita Khanna, an associate professor and director of the pelvic surgery fellowship in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, is running a pilot study repurposing an antifungal medication, atovaquone, to see if it helps inhibit disease progression. She notes a similar ongoing study using metformin, a commonly used type 2 diabetes medication, to treat endometrial cancer.

“Therapies for patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer tend to perform poorly, and these patients really need something that can produce some positive results,” says Khanna. She adds that her study uses an existing drug known to be well-tolerated. Khanna collaborates on both studies with Winship hematologist-oncologist David A. Frank, director of the Winship Innovation Initiative, director of the Division of Hematology and a professor in Emory University School of Medicine's Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology.

“We are expanding our research portfolio pretty quickly,” Khanna says, with the goal of being able to offer every Winship gynecologic oncology patient access to a clinical trial. “As a division, we’re working hard to bring more trials to patients.”

Besides expanding access to clinical trials, the department recently launched a collaborative clinic in Decatur for patients at high-risk for breast and gynecologic cancers. Modesitt built a similar program during her tenure at the University of Virginia and was eager to offer the same coordinated patient services at Winship.

The clinic, which soft-opened in mid-February, serves patients with a confirmed or likely genetic mutation that increases their risk of developing breast, ovarian and uterine cancers, according to clinic lead Jennifer M. Scalici,

gynecologic oncology program lead at Winship and division director for gynecologic oncology in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine.

Scalici describes the new clinic as “a place where there is time and space to really counsel patients about the gravity of some of these genetic mutations.” She adds, “I’m very excited about it. It’s a need in the community.”

In addition to leading the new clinic, Scalici is completing a Department of Defensefunded study looking at using chemoprevention to interrupt the development of ovarian cancer in hens, the only other species aside from humans with ovaries in which the disease spontaneously develops.

The bulk of the research was conducted at the University of South Alabama, Scalici’s prior institution, and she is now leading the data analysis at Winship.

“The problem in studying ovarian cancer in women is it’s a relatively rare disease and, in a hen model, it’s super common,” Scalici explains, noting that hens ovulate daily, accelerating any potential cancer growth. Its rarity in humans is fortunate, but also means limited data exists to guide care.

Scalici hopes her research will eventually yield better surveillance tools for high-risk patients, like targeted screenings that catch cancers early, or before they even develop. “It really is the bench-to-bedside model,” she says.

Another benefit of expanding trial access and opening a dedicated clinic for high-risk patients is the ability to build out Winship’s in-house research database on gynecologic cancers. This resource, which already contains over a decade of patient data, is essential to advancing research and is a potentially valuable asset due to Winship’s uniquely diverse patient population. Black women, historically and still today, remain vastly underrepresented in cancer research data sets. The Winship team is actively working to change that.

Black women with endometrial cancer are more likely to develop more aggressive versions of the disease, making their inclusion in research vital to addressing disparities in this—and other types of—cancer.

“There’s this subset of really aggressive types of cancers that are much more prevalent in African American patients,” Modesitt says.

Dilley adds, “We need to learn more about why this is happening to our patients, and we need to understand the nuances of their particular experiences.”

The growing gynecologic oncology team is united in their commitment to increasing patient care resources and to their role—unique in the oncology field—of caring for patients throughout their course of treatment.

“Gynecologic oncology is unique because we are able to care for our patients throughout their care continuum—from surgery to chemotherapy and beyond,” says Modesitt. “It’s a privilege to care for women who have so often spent their lives caring for others.”

Modesitt has a special tie to the patients in this community. She began her academic career at Emory as an undergraduate Woodruff Scholar, where she met her husband, “a Georgia boy.” Her medical training and career subsequently took her to Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky and Texas, but she promised him they would return to Georgia one day.

“I have a huge loyalty to Emory,” she says. “Even when I could only give ten bucks because I had no money, I gave back every year.” She continues giving back, by expanding access, increasing resources and leading a team focused on better outcomes for patients with gynecologic cancers.

“I love talking about how much work we have done to really transform the care that’s available to the women of Georgia,” Modesitt says.