Mahan Esfahani

GBSR Duo

Siwan Rhys

Mahan Esfahani

GBSR Duo

Siwan Rhys

LAURENCE OSBORN (b. 1989)

GBSR Duo

Siwan Rhys

Mahan Esfahani Clement Power piano harpsichord conductor George Barton percussion Siwan Rhys piano track 1 tracks 6–8 tracks 9–10 tracks 1, 9–10 tracks 1–10 �� Ensemble

1 TOMB! (2022) [18:46]

Lakes, Mists, Bats, Daggers and Fountains (2023)

2 I. Subdued, emerging, like lost, old music [5:40]

3 II. Nocturnal [5:27]

4 III. Soft and light [3:00]

5 IV. Always light and airy [6:41] Me and 4 Ponys (2018)

6 I. Mechanical [3:32]

7 II. Jerky and toy-like – Broad and sweeping [4:04]

8 III. Airy, supernatural – Slightly slower, distant [6:52]

Coin Op Automata (2021)

9 I. Mechanical [4:18]

10 II. Sweet and sad [7:46] Total playing time [66:11] premiere recordings

This recording was made possible by generous financial support from the Vaughan Williams Foundation, the Francis Routh Trust, and an anonymous donor. Thanks are due also to the Master & Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge, where Laurence Osborn is a Fellow Commoner in the Creative Arts from 2024 to 2026, as well as to Paul Nicholson and Alison Sutton in the Chapel and Music Office for practical support in the organisation of the recording sessions.

Violin

Eloisa-Fleur Thom*

David López Ibáñez*

Oliver Cave

Guy Button

Ellie Consta

Coco Inman

Viola

Miguel Sobrinho*

Tetsuumi Nagata

Dominic Stokes

* string quartet in tracks 2–10

Cello

Max Ruisi*

Sergio Serra

Double bass

Toby Hughes

Harpsichord: a double-manual instrument by Jukka Ollikka (Prague, 2018), based on models by Michael Mietke (Berlin, c.1710)

with the addition of a 16’ register; carbon-fibre composite soundboard; compass EE–f3

Piano: Steinway model D, serial no 558473 (c.2001–2)

Recorded on 15-17 April 2025 in Trinity

College Chapel, Cambridge

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mixing & mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano technician: Marcel Kunkel

(Cambridge Pianoforte)

Harpsichord technician: Simon Neal

Cover image composite:

photographs by Levi Meir Clancy & JRvV / both Unsplash

Design: John Christ

Session photography © Ben Reason

Booklet editor: John Fallas

Delphian Records Ltd – Oxford – UK www.delphianrecords.com

At the centre of Laurence Osborn’s Coin Op Automata , for harpsichord and string quartet, three of the previously busy quartet members fall silent while their leader plays an ornately decorated, stop-start melody, right up in the violin’s highest register. The harpsichord, too, is briefly reduced to a single strand of melody – the same melody, in fact, but deep down in the bass, sounding a full five octaves below the violin.

mounted on retractable tongues, whose early development was historically coterminous with various forms of clocks and levers. Hearing it here tracking the violin so closely, we are more than usually aware of the fact that it is something paradoxical: a machine that sings.

@ delphianrecords.com

@ delphianrecords

@ delphian_records

The gap between the two instruments is not just a question of register. By producing as it were a ‘double image’ of a single melody, with violin and harpsichord tracing in parallel the same pitches and rhythms yet in every other respect sharply contrasted – low vs high, plucked strings vs bowed strings, decaying sounds vs sustained ones – Osborn draws attention to the very nature of sound production by the respective instruments. When the violin ‘sings’, it is as a result of visible human actions: bow speed and direction, finger placement and vibrato. The harpsichord, by contrast, translates keystrokes into sound by means of a complex plucking mechanism hidden out of sight – a system of jacks and plectra

The coexistence of the mechanical and the transcendent or spiritual, as Osborn observes, has animated much music. ‘That’s what Ravel does so brilliantly,’ he has said: ‘it’s music that’s at once the most magical, extraordinary, miraculous thing you’ve ever heard, and at the same time it’s a mechanical object that bears the trace of human design.’ Here, in this strange, winding melody, the way the harpsichord is ‘pulled along’ by the violin – this uncanny, almost ventriloquistic moment at the centre of a work whose very subject matter is puppets and automata – makes the paradox explicit, just as the first work on this album, TOMB!, makes explicit what is arguably always going on when a composer revisits aspects of music’s past, revoicing old melodies or reusing old forms. The questions raised in the process are ultimately questions about life: about what it is to be human, and what it is to represent that humanness in music.

Border states between life and something not-quite-life are a central concern in the aria ‘Possente spirto’ from Monteverdi’s opera Orfeo, in which the eponymous hero pleads with Charon for passage into the underworld in terms which cast him as alive only in outward appearance:

I do not live, no; since my dear bride Was deprived of life, my heart is no longer with me, And without a heart how can it be that I live?

Osborn quotes Monteverdi’s aria at the centre of TOMB!, a twenty-minute piece for twelve solo strings, percussion and piano which draws on the concept of the tombeau, a musical genre originating in seventeenthcentury French lute music (though now largely known through Ravel’s 1917 piano suite Le tombeau de Couperin, itself already edging in the direction of a meta-commentary on the genre). The tombeau was a memorial piece for a composer colleague, avoiding many of the expressive features of mourning associated with the Italian lamento style in favour of a cool stylistic homage. ‘Like its granite namesake [tombeau is also French for “tombstone” in the literal sense], the tombeau is constructed to preserve an impression of a person in defiance of their mortality,’ writes Osborn. ‘But unlike a literal tomb, the deceased person is commemorated through impersonation rather than representation: the artist honours

the dedicatee by assuming their voice. Viewed this way, the tombeau becomes a séance, the composer a medium, the dedicatee a voice from beyond the grave. If the tombeau is commemoration-as-necromancy, its content might constitute an undead voice: the macabre reanimation of a lifeless music. TOMB! expands on this conceit, re-imagining dead musical objects and forms as decomposing material to be exhumed and reanimated.’

Although it plays continuously, TOMB! falls into three broad sections, defined registrally and timbrally as well as symbolically by the notions of ascent and descent. The opening is audibly a sort of passacaglia, with a C minor-ish tonality and a repeating theme, or ‘ground’, in the bass register, though the assignation of this ground to tuned percussion (timpani and rototoms, later adding Thai gongs and steel drums as the register expands upwards) already estranges it from Baroque models, and its repetitions gradually reveal composed-in ‘irritants’, harmonic and rhythmic kinks which imbue the formal model with what Osborn describes as a ‘lurching, zombified’ quality. The music accelerates in stages, taking on as it does so the outlines of Baroque dance forms – first a forlane, then a gigue – while all the time seeming not quite human, as if its rapid progress through these different formal (dis)guises were being impelled by some unseen force: a hand operating a puppet,

or a living being placed under a spell. The grotesque aspect of reanimating antiquated forms is made vividly tangible. At the same time, the increase in tempo throughout the section is paralleled by a progressive shift from deep, resonant sonorities to high, bright, metallic ones, as well as a gradual expansion of pitch content from pentatonic to diatonic to chromatic. ‘My intention’, Osborn has commented, ‘was to endow TOMB! ’s opening [section] with sonic illusions depicting the exhumation of music from somewhere deep within the earth.’

As the gigue reaches its high point, it gives way to a clock-like ticking in pizzicato high violins and xylophone, against which the ‘Possente spirto’ melody is heard for the first time, shared between the three violas (all playing with practice mutes). Throughout this middle third of the piece, these two elements coexist: song and mechanism, that juxtaposition that is so crucial to both TOMB! and Coin Op Automata. The ticking slowly decelerates as it descends in register, and at the same time darkens in sonority, reversing the trajectory of the piece’s opening section. And as the music around it descends and darkens, the melody appears to come closer – an illusion produced by the gradual removal of mutes and reduction of resonance in the accompanying string ‘halo’ as it shifts up into the violins. Both layers in their different

ways are leading us into the underworld, approaching the undead Orpheus and his song.

The piece’s final third is another ascent, but towards a more uncertain destination. It begins animatedly enough, led by moto perpetuo semiquavers in the piano and with tuned percussion joining in as the music presses forward. Back down in the bass, a transformed version of the work’s opening passacaglia starts up, evolving this time into a four-part fugato passage – another Baroque reanimation. As the passacaglia material resumes more forcefully, the music begins to be invaded by returning fragments of Orpheus’s song. At first taking the form of insistent, closely overlapping entries in high violins, with repetition these begin to lose their motivic identity, eventually dissolving into simple C major and minor scale patterns. Is this apotheosis or defeat? Victory or annihilation? The ambiguity, Osborn suggests, is deliberate: ‘the ending reaches back, ouroboros-like, into the same liminal realm between life and death from which the piece emerged’.

TOMB! is in many respects the end of a chapter in Osborn’s output. His next major piece, the string quartet Lakes, Mists, Bats, Daggers and Fountains, again reaches back into the Baroque for its viol-consort-like opening movement, all dusky timbres and harmonic false relations, but evolves from here into a much freer, less historically self- conscious dialogue with

aspects of more recent music history, and does so through the vehicle of an instrumentation and genre – the string quartet – whose own history entirely postdates the Baroque, stretching from the mid-eighteenth century into our own day. Something of this change of attitude may be signalled by the title, which quotes a disparaging description of Romanticism from the nineteenth-century French newspaper Le Corsaire that Osborn came across in David Cairns’ biography of Berlioz. Osborn says he chose it because he found the chain of images irresistible but that he made no attempt to depict them in the music; still, it’s hard not to see it as symbolic of a new-found willingness to abandon pre-existing conceptual scaffolds and let the imagination roam freely.

Spontaneity extends to the work’s formal aspect: Osborn’s original plan for a symmetrical five-movement arch shape modelled on Bartók’s fourth and fifth quartets gave way in the course of composition to a looser scheme of echoes and pre-echoes, both motivic/thematic and structural. Typically for Osborn, the movements were not composed in the order they are finally heard, so that material is sometimes encountered first in a more developed state, and only later in the form in which it was first composed.

The primary vector of unity is the four-note stepwise descent which is already present

in the first movement’s opening figure. It is there again at the beginning of the third movement, where it is recast as a ghostly melody shared between high violins and viola harmonics before dropping down to its original treble register; its pitches also inform the dance-like episode at that movement’s centre. But its overlapping minor thirds also form the basis for the extended melody which first appears as an eerie, then increasingly impassioned, violin duet over the Bartókian ‘night sounds’ of the second movement, and which in both concealed and more ostentatious guises permeates the moto perpetuo finale, whose insistent irregular metres again suggest that the Bartókian model has not been left so far behind after all.

If the ‘exorcism’ of TOMB! allowed Osborn to approach the classical genre of the string quartet head on, the piano quintet Me and 4 Ponys – the earliest work included on this album – takes a much more unorthodox, even cavalier approach to the generic history of its chosen medium, which it seems to reinvent as if from first principles. The composer’s own programme note gives a vivid flavour of his concerns while writing the piece:

I love drawings by children because they are completely unconcerned with consequence or correction. The first mark on paper is always part of the final work. Each line is fearlessly drawn.

Form, scale and subject change constantly throughout the creative process, at the whim and intuition of the artist. The results are always endearing and grotesque in equal measure.

Me and 4 Ponys wasn’t made in this way – I rewrote and scrapped a lot of music while writing it. But it musicalises aspects of children’s drawings: hard, wax-crayon-like textures, and big, unannounced gestures like handprints or blobs of paint.

Although the title clearly at some level reflects the one-plus-four instrumental formation, there is no clear mapping of, say, ‘me’ on to the piano and ‘four ponies’ on to the four string instruments. Rather, the image is translated into music as through a child’s logic, by means of a single, bold compositional choice – the galloping, jig-like pulse which imposes itself at the very beginning and persists throughout the first and parts of the third movement. It functions, like the dance forms in TOMB!, as an object plucked out of music history, reanimated and made to ‘lurch rather than dance, disintegrate rather than develop’.

Coin Op Automata, too, draws its inspiration partly from childhood – in this case, from a memory Osborn’s wife Karis shared with him of trips she used to take with her mother to a museum in Covent Garden filled with coin-operated machines: a mechanical family slurping spaghetti, a singing bird with a metal

throat, a miniature unicyclist lurching along a wire … The structure of the piece, as Osborn points out, is itself an arcade: a series of little musical automata, notionally separate although placed together in the same space. It begins, he says, ‘as an expansion of the harpsichord’s inner mechanism, wires crawling out of the belly of the instrument to lasso the string players and lead them in a clockwork dance’.

The series of mechanical tableaux that follows is grouped into two movements, the first made primarily from wood-like sounds and the second – which begins with the chimerical ‘double voice’ and its long thread of melody – more metallic in sonority.

In making a piece out of a succession of mechanisms, Osborn found that the individual tableaux were not as entirely self-contained as the concept might initially have suggested; the machines share parts as well as space, as it were, with musical ideas recurring in both obvious and more hidden ways between the different episodes and movements.

As in the string quartet, individual sections were composed out of sequence and the connections between them are deliberately non-linear, opposed to conventional ideas of musical ‘development’. Moreover, the final form, with the tableaux arranged into a diptych shape inspired by an otherwise very different, more dreamlike but equally episodic work, Henri Dutilleux’s string quartet

Ainsi la nuit, * is in a certain sense arbitrary: the order of episodes could have been different. Yet the structure in itself encourages a joined-up kind of listening which a larger number of short movements might have denied – an awareness of potential connections and points of contact, however tenuous.

In this sense, the piece, ostensibly about machines which imitate human activity while remaining clearly machine-like, perhaps has something more indirect, too, to say about life – not so much by representation

as by analogy. It would be foolish to push the point too far, but we might at least note the particular resonance, in a piece composed in 2021, of the idea of little pockets of life, or of something not-quite-life: almost but not quite self-contained, perhaps a little stuck, intermittently showing awareness of a fuller existence just beyond reach.

John Fallas is a writer and editor with a special interest in the music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

* Specifically, the way in which the forceful unison D that concludes that work’s section ‘III. Litanies’ gives the work an overall bipartite shape.

Formed in 2012 by artistic directors Eloisa-Fleur Thom and Max Ruisi, the 12 Ensemble is now recognised as one of Europe’s leading string orchestras. Innovative programming and fearless performances of intensity and commitment have garnered the group a reputation as an influential collective, reaching audiences worldwide with powerful performances.

The 12 Ensemble performs regularly across major venues and international stages – the Barbican, Southbank Centre, Royal Ballet and Opera, BBC Proms, De Doelen (Rotterdam), Philharmonie de Paris – and held an Artist in Residence position at Wigmore Hall between 2023 and 2025. Bringing together some of London’s finest chamber musicians, the group’s collaborative, conductorless approach produces exhilarating performances of rare immediacy and musical integrity. Alongside its commitment to exceptional performances of core repertoire, the group is a champion of new music and regularly commissions new works. Collaborating closely with a new generation of composers, the ensemble has premiered a number of award-winning works in recent years, with Oliver Leith’s Honey Siren receiving an Ivor Novello Award in 2020 and Laurence Osborn’s TOMB! both an Ivor Novello Award and a Royal Philharmonic Society Award in 2024. The ensemble joined forces with Leith once again at the Royal Opera House for his

acclaimed opera Last Days in 2022, and recently premiered and toured his Doom and the Dooms with GBSR Duo and guitarist Sean Shibe.

The ensemble’s reputation for adventurous collaboration extends well beyond the classical sphere, working regularly with Jonny Greenwood on both concert works and film scores, as well as collaborations with artists including Nick Cave, Bryce Dessner, Max Richter, Oliver Coates, Danny Harle, Laura Marling and Ichiko Aoba. The ensemble has released three critically acclaimed albums: Resurrection (2018), Death and the Maiden (2021) and Metamorphosis (2024).

Mahan Esfahani has made it his life’s mission to rehabilitate the harpsichord in the mainstream of concert instruments, and to that end his creative programming and work in commissioning new repertoire have drawn the attention of critics and audiences across Europe, Asia and North America. The first and only harpsichordist to be a BBC New Generation Artist (2008–10), he is also a Borletti-Buitoni Trust prizewinner (2009) and a three-time nominee for Gramophone Artist of the Year (2014, 2015 and 2017). In 2022, he became the youngest recipient to date of the Wigmore Medal, in recognition of his significant contribution and longstanding relationship with Wigmore Hall.

His work for the harpsichord has resulted in recitals in most of the major series and concert halls, amongst them Wigmore Hall and the Barbican Centre, London, Oji Hall in Tokyo, the Forbidden City Concert Hall in Beijing, Shanghai Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House, Melbourne Recital Centre, Walt Disney Concert Hall (Los Angeles) and Carnegie Hall (New York), Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival, the 92nd St Y, San Francisco Performances, Konzerthaus Berlin, Tonhalle Zurich, Kölner Philharmonie, Wiener Konzerthaus, Fundación Juan March (Madrid), Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, Edinburgh International Festival, Aldeburgh Festival, Aspen Music Festival, Bergen Festival, Festival MecklenburgVorpommern, Al Bustan Festival (Beirut), Jerusalem Arts Festival and the Leipzig Bach Festival, and concerto appearances with the Chicago Symphony, Ensemble Modern, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony, Melbourne Symphony, Auckland Philharmonia, Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orquesta Sinfónica de Navarra, Malta Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestra La Scintilla, Aarhus Symfoniorkester, Les Violons du Roy (Montreal), Symphoniker Hamburg, Munich Chamber Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Royal Northern Sinfonia, and Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, with whom he was an artistic partner for 2016–18.

His richly varied discography includes seven critically acclaimed recordings for Hyperion and Deutsche Grammophon – garnering one Gramophone Award, two BBC Music Magazine Awards, a Diapason d’Or and ‘Choc de Classica’ in France, and two ICMAs (International Classical Music Awards).

Sinfonietta and the LA Philharmonic, to inventive cross-disciplinary pairings with artists like Angharad Davies and Dejan Mrdja.

GBSR Duo – George Barton (percussion) and Siwan Rhys (piano) – combines two of the UK’s finest young contemporary chamber instrumentalists: ‘a wonderful, adventuresome, sensitive pair of musicians’ (Kate Molleson, BBC Radio 3).

Known for their fearless, intense performances, GBSR’s work ranges from the twentieth-century modernism of Stockhausen and Ustvolskaya to music by Brian Eno and Aphex Twin; from the exquisite delicacy of composers like Morton Feldman, Eva-Maria Houben and Barbara Monk Feldman to the cracked virtuosity of Alex Paxton and Arne Gieshoff; and from the classic experimentalism of John White and Christopher Hobbs to the contemporary cross-genre work of Oliver Leith, Laura Bowler and CHAINES.

Their collaborations range from team-ups with leading soloists and ensembles such as the Heath Quartet, EXAUDI, 12 Ensemble, Twenty Fingers Duo, Sean Shibe, the Basel

GBSR’s recordings are praised for their exceptional fidelity and variety, whether bringing new depths of appreciation to existing repertoire through benchmark recordings of Stockhausen (‘Album of the Week’ – The Guardian; ‘the best spatial audio purchase I’ve made this year’ –Seth Colter Walls, The New York Times ) and Barbara Monk Feldman (‘achingly beautiful’ – Christian Carey, Sequenza 21 ) or highlighting new works in premiere recordings of Oliver Leith, Eva-Maria Houben, Lisa Illean, Alex Paxton, Lawrence Dunn, Julius Aglinskas and others.

Regular performers at Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Kings Place and Bold Tendencies (London), the Duo have also performed at venues including Wigmore Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room, Linbury Theatre (Royal Opera House) and Walt Disney Concert Hall (Los Angeles), and at festivals including Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Muzikos Ruduo Vilnius, Presteigne Festival, Sound Aberdeen, Spitalfields Music Festival, No Bounds, Cheltenham Festival, Norfolk and Norwich Festival and the Three Choirs Festival.

GBSR are hcmf// Fielding Talent artists and were the winners of the Royal Philharmonic Society 2025 Young Artist award, the judges commending them for a ‘commitment to new music that’s thrilling in its fearlessness … their programmes and collaborations fizz with style, energy and invention’.

Welsh pianist Siwan Rhys enjoys a varied career of solo, chamber and ensemble work with a strong focus on contemporary music and collaboration with composers and other artists. Her playing is renowned for its multifaceted virtuosity, unerring rhythmic precision, and for its rich palette of timbral control, even when pushing the limits of the piano’s dynamic capabilities – from her recordings of Barbara Monk Feldman (‘luminous, gorgeous piano sound … a beautiful vulnerability’ – Gillian Moore, BBC Radio 3 Record Review ) to her performances of Ustvolskaya piano music (‘singular, stupendous, percussive works, superbly played’ – Fiona Maddocks, The Observer ).

Her exploration of the extremes of her instrument’s potential has also led to a specialism in inside-piano and preparedpiano techniques, as heard in many notable performances and recordings including her own transcriptions of Aphex Twin, Thomas Larcher’s virtuosic Ouroboros (with the

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra) and Sarah Lianne Lewis’s RPS Awardwinning solo work letting the light in Her recordings include solo piano music by Barbara Monk Feldman, Ryoko Akama and Mira Calix/John Cage, and chamber music by Lisa Illean, Oliver Leith, Alex Paxton, Cassandra Miller, Eva-Maria Houben, Lawrence Dunn, Stockhausen and Steve Reich, featuring on labels such as NMC, Platoon, HCR, all that dust, Nonesuch and Another Timbre.

Her work has taken her to venues including all the major London concert halls, Concertgebouw (Amsterdam), Elbphilharmonie (Hamburg), Philharmonie de Paris, Carnegie Hall, Walt Disney Concert Hall and Tokyo Opera City. She has appeared at the BBC Proms, Aldeburgh Festival, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, MaerzMusik (Berlin), the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Warsaw Autumn and many others.

In addition to her work as one half of GBSR Duo, Siwan is also a member of new music groups Explore Ensemble and the Colin Currie Group, and works regularly with other ensembles including London Sinfonietta, the London Symphony Orchestra and Riot Ensemble.

Born in 1980, Clement Power studied at Cambridge University and the Royal College of Music, then held assistant conductorships with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Ensemble intercontemporain. Strongly committed to music as a living tradition, he regularly collaborates with leading new music ensembles worldwide.

Recent conducting engagements include Ensemble Musikfabrik (Cologne), Klangforum Wien (Vienna), London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Philharmonia, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, NHK Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo), Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart, hr-Sinfonieorchester (Frankfurt),

Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, Estonian National Symphony Orchestra, Ensemble intercontemporain (Paris), Ensemble Contrechamps (Geneva), Avanti! Chamber Orchestra (Helsinki), Ictus Ensemble (Brussels), Ensemble Modern (Frankfurt), Munich Chamber Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia (Cambridge) and Ensemble TIMF (South Korea). He has been the guest of festivals including Lucerne Festival, Salzburg Biennale, Darmstädter Ferienkurse, Wien Modern, Acht Brücken, Eclat Festival, Warsaw Autumn, Venice Biennale, Aldeburgh Festival and Agora (IRCAM). Opera premieres include Hèctor Parra Hypermusic Prologue (Liceu, Barcelona), Wolfgang Mitterer Marta (Ictus / Opéra de Lille), and Liza Lim Tree of Codes (Musikfabrik / Oper Köln).

Previous recordings have appeared on Kairos, col legno, Wergo and Orchid Classics. Since October 2024, Clement is Professor of New Music at the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna.

Alex Paxton: Happy Music

Dreammusics Orchestra & Ensemble

DCD34290

An album of joyful music for orchestra, ensemble and improvisers, from a multi-award-winning composer described as ‘unique, inventive, brave and arresting’. With inspirations as wide-ranging as the artists Ody Saban, Madge Gill and Grayson Perry, the cartoon music of Roobarb and Custard, the water drumming of the African Baka women, or the sheer chaotic joy of getting a class of primary-school children to make music together, Paxton’s work finds happiness in mess, friction, imprecision and excess.

‘structures that miraculously hold together, while threatening constantly to burst apart from sheer exuberance’

— The Wire, May 2023

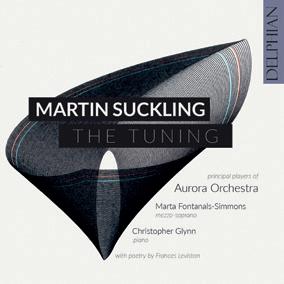

Martin Suckling: The Tuning Aurora Orchestra principal players;

Marta Fontanals-Simmons mezzo-soprano, Christopher Glynn piano

DCD34235

The everyday is transfigured in this intimate collection of chamber music and songs – settings of five magical, moonlit poems by Michael Donaghy and a string quintet written in collaboration with the poet Frances Leviston, whose readings of her own texts frame the four movements of a piece which pays dual homage to Schubert and to Emily Dickinson. Nocturne for violin and cello bears witness to Suckling’s night vigils at the composing desk, setting down his pen as the stillness starts to ripple with birdsong, while the cello solo Her Lullaby is a nostalgic reflection on the early years of parenthood that also displays Suckling’s characteristically refined harmonic palette.

‘This beautifully played and recorded disc shows [Suckling’s] more intimate side’ — BBC Music Magazine, March 2022, FIVE STARS

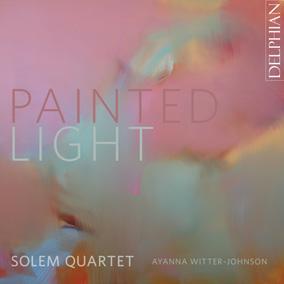

Solem Quartet, Ayanna Witter-Johnson voice

DCD34308

This inventively curated album from the ever-exploratory Solem Quartet presents music that is awash with colour. The refined beauty of Edmund Finnis’s Devotions and stained-glass luminosity of Camden Reeves’s The Blue Windows are complemented by works by Lili Boulanger and Henriëtte Bosmans from the early twentieth century, when the depth and vividness of colour in Impressionist paintings seemed to spill into music. A sense of awed wonder before the natural world informs Ayanna Witter-Johnson’s Earth, for which the Quartet is joined by the composer as vocalist, while Joni Mitchell’s Both Sides Now – heard here in an arrangement by the Quartet’s violinist William Newell – provides a delicate lesson in perspective.

‘Solem Quartet have produced a thing of beauty … catches your breath for all the right reasons’ — dCS: Only the Music, Classical Choices, October 2023

AWARDS ���� Shortlisted – Vocal

Héloïse Werner: close-ups

Héloïse Werner and friends

DCD34312

Héloïse Werner’s first album, Phrases – released on Delphian in June 2022 – was received ecstatically. For her second, she wanted to create a programme with a cohesive narrative arc: a journey, but one that the listener can take in their own time and their own way. For it, she has assembled a group of musicians who share in her concept but also bring to the project their own varied musical personalities to complement Héloïse’s own distinctive voice. These collaborators

– Colin Alexander, Julian Azkoul, Max Baillie, Kit Downes, Ruth Gibson and Marianne Schofield – stitch their individual contributions into close-ups in colours just as vibrant as Héloïse’s own.

‘jaw-dropping technical agility combined with an innate, instinctive musicality and boundless, breathless creativity’

— Gramophone, August 2024