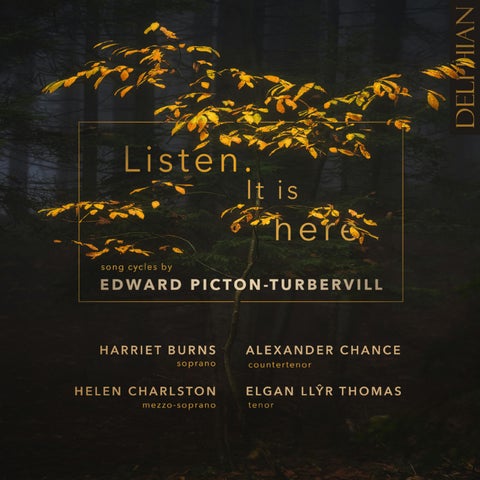

Listen. It is here.

song

cycles by

EDWARD PICTON-TURBERVILL (b. 1993)

HARRIET BURNS soprano 2–5, 21, 26–28

HELEN CHARLSTON mezzo-soprano 1, 23–25, 29

1 We have not long to love

Poems of the Sky

2 I. Oh, not to be separated

3 II. Onto a vast plain

4 III. Tombs of the Hetaerae [4:00]

5 IV. Immer wieder [2:33] To The Old Gods

6 I. Santa Decca [2:51]

7 II. Song of Ionia [2:16]

8 III. To the Old Gods [2:08] Songs for A

9 I. I know the place

10 II. Denmark Hill

11 III. To my Wife

ALEXANDER CHANCE countertenor 6–8

ELGAN LLŶR THOMAS tenor 9–13, 22

EDWARD PICTON-TURBERVILL piano

21 O ignis Spiritus Paracliti [6:42] Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), arr. Edward Picton-Turbervill Edward Picton-Turbervill & Thomas Eeckhout piano duet

22 The Prize Song of Taliesin

I want to be a cow

23 I want to be a cow

24 Nothing fancy [2:02]

25 The Tibetans [3:46] Two Vedic Hymns

26 I. Love is the one who gives [2:01]

27 II. Gaze gently [1:38]

28 Arise, my love [2:09]

29 To the place of trumpets [6:05]

Total playing time [73:35]

All tracks are premiere recordings

I wish to thank the City Music Foundation and the Viola Tunnard Trust, without whose generous support this album would never have been possible. I also wish to thank Lady Antonia Fraser for graciously granting permission for the use of a line of Harold Pinter for the title of the album, and to Tim Watts for writing such thoughtful and perceptive liner notes. And finally, I would like to thank all my many inspirational teachers, without whom this album would not exist. — Edward Picton-Turbervill

Over a rippling pianistic ocean sails an ecstatic voice. It sings of love: ‘Love is the one who gives. Love is the one who receives. Love is the one who gives and receives.’ Edward Picton-Turbervill’s setting of these lines in the first of his Two Vedic Hymns casts the duo of voice and piano as lovers, bound to each other by constantly renewed reciprocation. Wire strings stirred to life by the warmth of a singer’s breath … breath made to dance on the fingers’ rhythmic tides …

Imagined through the lens of the intimate connection of singer and pianist, all songs are love-songs, and this is resoundingly true of Edward’s contributions to the genre. Yet they sing not of an exclusive love that shuts out the world beyond the bubble of two lovers, but of song as a teeming gathering point. For in songs like these, the two ‘protagonists’, like any pair of lovers, are brought together and borne on the swirl of submerged currents. This is the meeting place of words and music, sound and silence, past and present, memory and prophecy, where innumerable voices mingle. And in the union of song is also the possibility of reaching towards, even touching, the divine.

Edward’s musical idiom is steeped in the pulse and patterning of Anglican psalmody, enriched with sensuous impressionistic harmonies and disarmingly undercut by hints of folk or show songs. Significantly, there is often little

musical distinction between his setting of texts taken from the Judaeo-Christian tradition (represented by Arise, my love, from the erotically charged Song of Songs, and by the equally idiosyncratic mysticism of Hildegard of Bingen’s O ignis Spiritus Paracliti) and those from other religious traditions or with pagan, pantheistic or supposedly secular themes. The numinous qualities evoked in this music are to be found everywhere, irrespective of time, place or doctrine. Yet a song such as To the Old Gods reminds us of both the power and ephemerality of the kind of worship that song enacts. Edwin Muir’s poem wonders if it might be better for the old gods and goddesses if they had ‘fled our ever-dying song’, which suggests the disconcerting possibility that song may be as much a curse as a blessing. For while song may briefly deify its objects, in its transience it forgets them, too.

Brevity is essential to the notion of the song as a fleeting glimpse of mysteries too big and too mysterious to grasp for more than a moment. This is also the moment, too soon passed, of human love, both celebrated and lamented in the bittersweet Tennessee Williams setting, We have not long to love. Its urgent awareness of time passing courses through all these songs: some of them telescope centuries or millennia into minutes, while others, short as they are, amplify (as if seeking to hold on to) tiny epiphanies. According to Edward, the songs themselves

often crystallise in such instantaneous realisations, germinating in ‘a shiver down the spine’. The very shortest of them are the Songs for A, which set five minuscule, yet emotionally overwhelming poems addressed by Harold Pinter to his wife, Antonia Fraser. The story that the composer tells of their genesis illustrates well the many confluences that may underlie a song’s coming into being. During his studies at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, Edward had been working on Stephen Hough’s setting of Fraser’s words and wrote to her ‘out of the blue’, offering to perform them for her since the pandemic had managed to deprive her of the opportunity to hear them. Delightedly, she accepted and over tea at her home, the composer spotted a stone in her fireplace bearing the inscription, ‘Listen. It is here.’ These final four words of what was to be the last song of this miniature cycle ignited a spark, illuminating some nebulous but potent foreknowledge of the musical setting that was to come. It was in more ways than one, a beginning born from an ending. Sensing his interest had been piqued, Lady Antonia gifted him the pamphlet from which the other songs would emerge.

Equally aphoristic in nature, yet collected over a much longer time period, are the enigmatic piano miniatures that honour seven close friendships. Together, these Seven Portraits form a kind of diary of three or more years of life, spanning the composer’s student

experiences in Cambridge, Heidelberg and London. Quirkily characterised as each little movement may be, the set, taken as a whole, universalises the theme of friendship. All seven people are housed under one pianistic ‘roof’ to form a family, in which the piano itself emerges as the composer’s constant companion.

At the opposite end of the size spectrum sit The Prize Song of Taliesin and I want to be a cow. Both occupy a genre described in the composer’s own coinage as ‘megasong’, quasi-operatic in their sense of proportion and personality, and unfolding through a series of theatrically conceived changes of scene and pace. Written during a period of Covid-induced isolation in Alabama, The Prize Song casts the legendary Welsh bard as a being so wholly identified with his extraordinary gifts as a singer that he is able through them to become one with the world he inhabits, shapeshifting into anything from a ‘a blue salmon’ to ‘a ramping great bull’. For the feminine persona of I want to be a cow, the bovine state is fervently desired yet, despite the shift near the end of the song from ‘I want’ to the more decisive ‘I’m going to be a cow’, it remains fantastically out of reach. A parade of music theatre-tinged comic turns gives voice to the frustrations of a woman defined and compromised by her relationships to her mother and lover, while hankering after the ‘dumb’ simplicity that she imagines to be the happy lot of the ‘counted cow’. If it seems paradoxical that the singer

of a song should aspire to muteness, it is perhaps a reflection of the possibility that song represents a retreat (or flight) from the mundane heaviness of the spoken or written word, which it begins to silence even as it fills the air. I want to be a cow, for all its apparent (and mischievously incongruous) humour is as imbued with melancholy – even tragedy – as any of the other songs recorded here. The longer it goes on, the sadder it gets.

Poems of the Sky and To the place of trumpets (the latter another ‘megasong’) both express deep longing for a lost state of oneness: in Rilke’s words, ‘Oh, not to be separated, shut off from the starry dimensions by so thin a wall’. Both settings end in the contemplation of a kind of liberating surrender, depicted in the act of lying down in the flowers or in the grass. This is a gesture that, in permitting the body to succumb to Earth’s gravity, returns the gaze upwards. Sinking down, we once again may contemplate the sky, which is, according to Rilke, nothing more than what we already contain, albeit ‘intensified’ within us. In this way it represents a kind of ‘homecoming’ that helps to heal our sense of separation from the cosmos. It is a surrender from the individualised agency of our bipedal lives in favour of what Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s poem tellingly speaks of as going ‘back to where the self is song’. Hers is a vision of a paradisiacal reconciliation of opposites where, strikingly, ‘trust turns to betrayal as its friend’.

Many friends are folded into the pages of these songs, some openly acknowledged, others felt as more shadowy, yet no less vital presences. As Edward tells me, ‘In the fabric of the songs I can point you towards lines and moments that were written by people I love.’ For him, this makes the collection a ‘magic compilation … with lots of special people coming in and out’, and a ‘tapestry’ in which ‘years of memories and relationships are encoded’. The process of encoding is by its nature a complex and ambiguous one, implying both the losses and gains of translation and therefore fraught with the risk – perhaps the inevitability – of some degree of betrayal. Vowels are distorted or prolonged by being sung, texts are framed or angled differently through the composer’s intervention, human partnerships shrink down to the silhouettes of notes on staves. Yet at the same time, abbreviations, shorthands and secret ciphers are also the currency of familiarity and love. ‘Antonia’ becomes ‘A’ in Pinter’s poems, which in these settings is further encoded as the key centre of A. Like the nymph Arethusa transformed by Artemis into a fountain, the object of the poet’s love is transposed into the invisible force of musical tonality.

Heard collectively and cumulatively, the ‘thin walls’ between the songs themselves begin to blur and they form a window onto a singular and visionary terrain, which may well be described by Rilke’s phrase, ‘the landscape of

love’. It is a dreamscape, an Ionia overlaid with Christian compassion, Solomon and his lover transplanted to an English shire, a Welsh harp haunting a Steinway … In this way the songs build a world that seeks to reveal our world’s true strangeness, radiance and holiness: as the composer puts it, ‘all of creation humming with energy, all interconnected’. The vision these songs build, moment by precious moment, transcends their modest dimensions and lingers in the mind. Edward firmly believes in the ‘personhood’ of songs and in the agency of

these ‘children’ of many parents: ‘As the world gets darker … I hope that these pieces will have an effect on people, will change people, will make them more loving, more open to mystery.’ © 2026 Tim Watts

Tim Watts is a composer, pianist, writer and teacher. He is a Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge and a professor at the Royal College of Music, London.

Recorded on 9-11 January 2025 in SJE Arts, Oxford

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano: Steinway, model D, serial no. 582241 (2008)

Piano technician: Joseph Taylor

Cover image: Ales Krivec

Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Session photography: Will Coates-Gibson/Foxbrush

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.com

www.delphianrecords.com

and translations

1 We have not long to love

We have not long to love. Light does not stay.

The tender things are those we fold away.

Coarse fabrics are the ones for common wear.

In silence I have watched you comb your hair.

Intimate the silence, dim and warm.

I could but did not, reach to touch your arm.

I could, but do not, break that which is still.

[(Almost the faintest whisper would be shrill.)]*

So moments pass as though they wished to stay.

We have not long to love. A night. A day …

*This line is not included in the setting

Tennessee Williams (1911–1983), from the poem ‘We Have Not Long to Love’ from The Collected Poems of Tennessee Williams. Copyright © 2002 by The University of the South. Used by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc. on behalf of the University of the South. All rights reserved.

traversed with birds, and deep with winds of homecoming?

3 II. Onto a vast plain

Now you must step out into your heart, as onto a vast plain. Now the immense loneliness begins. The days grow numb, the wind sucks the world from your senses like withered leaves. Through the empty branches, the sky remains. Be Earth now, and evensong. Be the ground lying under that sky. Be humble, so that He who began it all can feel you, when he reaches for you.

4 III. Tombs of the Hetaerae

Poems of the Sky

2 I. Oh, not to be separated

Oh, not to be separated, shut off from the starry dimensions by so thin a wall. What is within us if not intensified sky,

They lie in their long hair, and their brown faces have long ago withdrawn into themselves. Eyes shut as though before too great a distance. And there are flowers, slender bones, woven cloth decaying over the shrivelled heart. But there, beneath those rings, talismans and gems, there still remains the silent womb, filled to its vaulted roof with flowers. And so they lie, and they darken as a river’s depths. For they were riverbeds once, and over them surged the bodies of countless young men. And in them roared the currents of grown men. Then they filled with cool shallow water, the whole breadth of this broad canal, and set little whirlpools turning in the depths. And for the first time, mirrored the green banks and the distant call of birds. While in the sky, the starry nights of another sweeter country blossomed above

them, blossomed above them and would never close!

5 IV. Immer wieder

Again and again, however we know the landscape of love

And the little churchyard with its sorrowful names

And the terrible concealing gorge, in which the others

End: again and again, the two of us walk out together

Under the ancient trees, and lie down among the flowers, face to face with the sky.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), translations by Joanna Macy & Anita Burrows, Stephen Mitchell and Edward Picton-Turbervill, adapted by Edward Picton-Turbervill. Translations by Stephen Mitchell from Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, published by Penguin Random House Limited, used with permission. Translations by Joanna Macy & Anita Burrows used with their permission.

To the Old Gods

6 I. Santa Decca

The Gods are dead: no longer do we bring To grey-eyed Pallas crowns of olive-leaves!

Demeter’s child no more hath tithe of sheaves,

And in the noon the careless shepherds sing, For Pan is dead, and all the wantoning

By secret glade is o’er:

Young Hylas seeks the water-springs no more; Great Pan is dead, and Mary’s Son is King.

And yet – perchance in this sea-trancèd isle, Chewing the bitter fruit of memory,

Some God lies hidden in the asphodel. If such there be it were well

For us to fly his anger: but see

The leaves are stirring: let us watch a-while.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

7 II. Song of Ionia

Because we smashed their statues, Because we chased them from their temples –

This hardly means that the gods have died.

O Land of Ionia, they love you still It’s you whom their souls remember still. And as an August morning’s light breaks over you,

Your atmosphere grows vivid with their living. And occasionally an ethereal ephebe’s form, Indeterminate, stepping swiftly, Makes its way along your crested hills.

C.P. Cavafy (1863–1933), tr. Daniel Mendelsohn (b. 1960). Translation Copyright © 2021 Daniel Mendelsohn. All rights reserved.

8 III. To the Old Gods

Old gods and goddesses who have lived so long

Through time and never found eternity, Fettered by wasting wood and hollowing hill,

You should have fled our ever-dying song, The mound, the well, and the green trysting tree. They have forgotten, yet you linger still.

Forests of autumn fading in your eyes, Eternity marvels at your counted years, And wonders how There could be thoughts so bountiful and wise

As yours beneath the ever-breaking bough, And vast compassion curving like the skies.

Edwin Muir (1887–1959), adapted. Text copyright The Estate of Edwin Muir, used by Permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Songs for A

9 I. I know the place

10 II. Denmark Hill

11 III. To my Wife

12 IV. Poem

13 V. It is here

poems by Harold Pinter (1930–2008)

I know the place (1975) © 1977 FPinter Limited

Denmark Hill (1977) © 1991 FPinter Limited

To My Wife (June 2004) © 2004 Fraser52 Limited

Poem (To A) (June 2007) © 2007 Fraser52 Limited

It is here (For A) (1990) © 1990 Fraser52 Limited

All rights reserved.

21 O ignis Spiritus Paracliti

O ignis Spiritus Paracliti, vita vite omnis creature sanctus es vivificando formas. sanctus es ungendo periculose fractos, sanctus es tergendo fetida vulnera.

O spiraculum sanctitatis, O ignis caritatis,

O dulcis gustus in pectoribus et infusio cordium in bono odore virtutum.

O iter fortissimum, quod penetravit omnia in altissimis et in terrenis et in omnibus abyssis tu omnes componis et colligis.

De te nubes fluunt, ether volat, lapides humorem habent, aque rivulos educunt, et terra viriditatem sudat.

Unde laus tibi sit, qui est sonus laudis et gaudium vite, spes et honor fortissimus, dans praemia lucis.

Hildegard of Bingen, adapted

O fire of the protecting Spirit, life of the life of all that is created, holy you are, giving life to empty forms, holy you are, anointing those who are dangerously broken, holy you are, wiping clean festering wounds.

O breath of holiness,

O fire of divine love,

O sweet taste in our breasts and infusion of our hearts in the good odour of virtues.

O most mighty path that has penetrated all that is in the highest heaven and on earth and in all the abysses, you arrange all and bind them together. Out of you clouds flow down, the upper air flies, stones have springs, waters bear streams, and the earth exudes verdure. Therefore praise be to you who are the sound of praise and the joy of life, hope and most mighty honour, giver of the rewards of light.

Translation © Henry Howard

22 The Prize Song of Taliesin

Neither of mother Nor of father was I formed; My creation was created Out of nine elements.

From fruit:

From primroses and gossiping flowers; From wood and trees’ pollen From Earth, from the soil Was I formed; From nettle flowers.

From the ninth wave’s water.

I was conjured by the wisdom Of sages, before the world, Before I had being, Before the world began. I played in the light, Slept wrapped in purple.

My tongue ran freely I sang for a glorious master On Severnside meadows For Brochfael of Powys, Beloved of my Awen.

I sang in the shield-wall At dawn before Urien.

And my inspired voice, my God formed it Just as he made milk, dew and hazelnuts.

I am Taliesin, Speech flowing with wisdom. My Praise of Prince Elffin Will endure till the Last Day.

I was a drop in the air

The sparkling of stars, A word inscribed

A book in priest’s hands

A lantern shining For a year and a half.

A bridge for crossing Over threescore estuaries.

I was path, I was eagle, I was a coracle at sea.

I was bubbles in beer, I was raindrop in shower. I was a sword in battle, I was a shield in the hand. I was a harp string.

I was a blue salmon, A hound and a stag

A roebuck on mountain

A clod and a spade an axe in the hand

An auger in tongs

A stallion at stud

A ramping great bull.

I was tinder in fire, I was forest ablaze.

Enchanted nine years in water, foaming,

I’m not struck dumb, I’m not going to stammer

When singers sing what they’ve learned by heart

No miracle they work will leave me beaten.

Thus I address the battling bards:

Contending with me is

Like dressing yourself when you have no hands

Like diving in lakes when you know you can’t swim

Like planning to travel without any feet

Like gathering nuts when there aren’t any trees

Lke ordering a raid without uttering a sound

Like an army of soldiers with none in command

Like feeding the needy with scraps of skin

Like a light that you show to a man who is blind

I’m the bard of the hall – I’m the lad in the chair I make poets stutter when they speak.

So most learned bard, tell me –

Where are the bones of the mist

And the wind’s twin waterfalls?

What draws smoke skyward?

What brought evil to birth?

What well pours out radiance

Above darkness’ canopy?

Now, skilful singer

Why do you not tell me?

Do you know where Night waits out the daytime?

Do you know the tally Of leaves on the trees?

What will lift up the mountains

Before the world ends?

Whence cometh Night and Day? Whence the sea’s seething?

What’s the measure of Hell?

How thick is the veil?

Whence flow the night and the flood?

How many the winds, the waters, How many the waters, the winds?

I know how many instants a day has How many days in the year, How many shafts fall in battle And drops fall in rain.

Poetry adapted by the composer from The Book of Taliesin: Poems of Warfare and Praise in an Enchanted Britain, tr. by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams. Translation copyright © Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams, 2019.

I want to be a cow

23 I want to be a cow and not my mother’s daughter. I want to be a cow and not in love with you. I want to feel free to feel calm.

A queenly cow, with hips as big and sound as a department store, a cow the farmer milks on bended knee, who when she dies will feel dawn bending over her like lawn to wet her lips.

24 I want to be a cow, nothing fancy –a cargo of grass, a hammock of soupy milk whose floating and rocking and dribbling’s undisturbed by the echo of hooves to the city; of crunching boots; of suspicious-looking trailers parked on verges; of unscrupulous restaurant-owners who stumble, pink-eyed, from stale beds into a world of lobsters and warm telephones; of streamlined Japanese freighters ironing the night, heavy with sweet desire like bowls of jam.

black in your gloves and stockings and sleeves and large hat.

Don’t call the tractorman.

Don’t call the neighbours.

Don’t make a special fruit-cake for when I come home:

I’m not coming home.

I’m going to be a cowman’s counted cow.

I’m going to be a cow and you won’t know me.

Selima Hill (b.1945), from Gloria: Selected Poems by Selima Hill (Bloodaxe Books, 2008). Reproduced with permission of Bloodaxe Books.

The parents of heroes, Be devoted to the gods, Bestow happiness.

Be good and kind to us, and to all creatures.

Rig Veda 10.85.44

25 The Tibetans have 85 words for states of consciousness. This dozy cow I want to be has none. She doesn’t speak. She doesn’t do housework or worry about her appearance. She doesn’t roam. Safe in her fleet of shorn-white-bowl-like friends, she needs, and loves, and is loved by, only this –the farm I want to be a cow on too.

Don’t come looking for me.

Don’t come walking out into the bright sunlight looking for me,

Two Vedic Hymns

26 I. Love is the one who gives Love is the one who gives.

Love is the one who receives.

Love is the one who gives and receives.

Love has entered into the ocean of being. Through love I receive you.

O love, all this is for you.

Atharva Veda 3.29.7 (adapted)

27 II. Gaze gently Gaze gently upon each other, Never be hostile to each other, Be tender to animals, Of cheerful mind.

Gaze gently upon each other, Beautiful in your glory. Be devoted to the gods,

28 Arise, my love

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

For lo, the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth, the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtle is heard in our land. The fig tree putteth forth its figs, and the vines give a good smell. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

Song of Songs 2:13b, 11–13

29 To the place of trumpets

We are going.

To the place of trumpets,

To the place where the sun sets, To the place where peace sits.

By twos and threes, going to choose

New weather and new clothes,

The new sound of words walking

As trees among the winging Fields, the fields on herons’ wings;

Where all who wake, wake undone, Back beyond their fragile bones, Back to where the self is song,

Lay us here, lay us long, Let us in this grass as one Sleep now where we first began.

Winds unwinding the last Sheets on streets where past And present meet, where West

Marries East, and trust turns

To betrayal as its friend, Where days and moon and sins are one

Blessed wind passing over

The passing plains, over The sea, the comforter,

Full of salt so sweet it fills

The hollow tongue until It splits as time will

Split. In the place where quiet ways grow, Where the wound loves the arrow, Where the lion’s lamb

Leads him with her song,

Lay us here, lay us long,

Let us in this grass as one Sleep now where we first began,

Here on the sand where we first met, Under the trees before His seat, Out of the cold, out of the heat,

In the place of trumpets.

Brigit Pegeen Kelly (1951–2016), adapted by the composer

Biographies

‘Brilliant and rich, comfortable even in stratospheric heights’ (BBC Music Magazine), British soprano Harriet Burns is in demand for her singing both in recital and on stage. An acclaimed interpreter of song, Harriet has performed at Wigmore Hall, Philharmonie Luxembourg and de Singel with Graham Johnson, Oxford International Song Festival with Imogen Cooper and Sholto Kynoch, Leeds Song with Joseph Middleton and Ryedale Festival with Christopher Glynn. Harriet regularly works with Ian Tindale, with whom she has released two discs on Delphian: Schubert Lieder: Love’s Lasting Power (DCD34251) and A Short Story of Falling (DCD34346).

On the operatic stage, recent roles include Berta (cover, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Rossini) for West Green House Opera, King Harald’s Saga (Judith Weir) for Waterperry Opera, Sifare (cover, Mitridate, re di Ponto, Mozart) and Oriana (cover, Amadigi, Handel) for Garsington Opera. In concert, she has sung Thea Musgrave Songs for a Winter’s Evening with the Southbank Sinfonia and Gabriella Teychenné, Handel and Mozart arias with Michael Bawtree at the National Concert Hall in Dublin, Bach Magnificat and Vivaldi Dixit Dominus with Nicholas McGegan and the Royal Northern Sinfonia at Sage Gateshead and Handel Messiah with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields.

Harriet is a 2021 City Music Foundation Artist and in 2023 was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music.

Since winning the London Handel Singing Competition in 2018, mezzo-soprano Helen Charlston has crafted a place for herself at the forefront of the classical music scene in the UK and abroad. Following the critical acclaim of Helen's debut Delphian album, Isolation Songbook (DCD34253) – recorded during lockdown – in 2023 she won a Gramophone Award for Best Concept Album and in the same year collected the BBC Music Magazine Vocal Award, both for her second Delphian album: Battle Cry: She Speaks (DCD34283). She was a BBC New Generation Artist (2021–23), a member of Le Jardin des Voix academy with Les Arts Florissants in 2021–22, and won the Loveday Song Prize at the 2021 Kathleen Ferrier Awards.

Helen has worked across the globe with the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra in San Francisco, Akadamie für Alte Musik Berlin, Warsaw Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic, RIAS Kammerchor, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra and Royal Northern Sinfonia. She made her BBC Proms debut in 2022 and returned the following two years. An avid recitalist, she has given performances at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Leeds Lieder, Oxford International Song Festival, and Brucknerhaus Linz.

On the operatic stage, she has sung roles at Gran Teatre del Liceu, Versailles Royal Opera, The Grange Festival, and covered a title role at Opéra national de Paris.

Countertenor Alexander Chance was born in London in 1992, and educated at New College, Oxford, where he was a Choral Scholar and read Classics.

He regularly works with many of the leading conductors in the early music world, including Sir John Eliot Gardiner, Masaaki Suzuki, René Jacobs, Masato Suzuki, Laurence Cummings, Jonathan Cohen, John Butt, Kristian Bezuidenhout, Marcus Creed, David Bates and Lionel Meunier. He is in demand as a concert soloist and has given many recitals around Europe, making his recital debut at the Wigmore Hall and Concertgebouw Amsterdam in 2024.

His debut recording, Drop not, mine eyes with lutenist Toby Carr, was named one of Gramophone’s ‘Best albums of 2023’. His recent opera roles include Oberon (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Britten) for The Grange Festival; Apollo (Death in Venice, Britten) for Welsh National Opera; and Tolomeo (Giulio Cesare, Handel) for English Touring Opera.

Recent and future highlights include his debut appearance at the BBC Proms, regular appearances at Wigmore Hall with the London Handel Players, Fretwork, Arcangelo and other groups, solo recitals with the English Concert, Freiburger Barockorchester and Dunedin Consort, and Andronico (Tamerlano) at the International Handel Festival in Karlsruhe.

In 2022, he became the first countertenor to win the International Handel Singing Competition, also winning the Audience Prize.

Tenor Elgan Llŷr Thomas hails from Llandudno, North Wales. He is a former English National Opera Harewood Artist, a former Scottish Opera Emerging Artist and Equilibrium Young Artists alumnus.

Appearances on the opera stage have included François (A Quiet Place) for London’s Royal Ballet & Opera; Dr Richardson in Mizzy Mazzoli’s Breaking the Waves at Opéra-Comique, Paris; Prunier (La Rondine) for Opera North; and the title role in Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress on a European tour with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Barbara Hannigan. With Grange Park Opera, he has sung Cassio (Otello) and The Steersman (Der fliegende Holländer), as well as Gonzalve in the lockdown film of Ravel’s L’heure espagnole

On the concert platform he has performed with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in A Child of our Time conducted by Martyn Brabbins; with the Boston Symphony and Barcelona Symphony Orchestras as tenor soloist in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, both conducted by Ludovic Morlot; and with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic in Mahler’s Das klagende Lied conducted by Ryan Bancroft.

Elgan Llŷr Thomas’ recordings include his debut recital Unveiled, with Iain Burnside and Craig Ogden, also available on Delphian (DCD34293).

Edward Picton-Turbervill is a British pianist, organist and composer, and is rapidly establishing himself as one of the most creative, imaginative and versatile classical musicians of his generation. He was a Britten–Pears Young Artist for 2024/25 and a City Music Foundation Artist for 2024/25, and can regularly be heard performing on BBC Radio 3. From 2012 to 2015, he was organ scholar at St John’s College, Cambridge, where he studied Music. After working as Head of Music at Atlantic College, he returned to study piano accompaniment at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama with Caroline Palmer, graduating with distinction and a concert recital diploma in 2023.

Edward’s first major choral work, Out of Eden, was premiered in Smith Square Hall in April 2025, and subsequently recorded by London Choral Sinfonia for release in Spring 2026. He is the organist at St John the Divine, Kennington, where he is proud to assist in the church’s renowned youth programme. He holds a Master’s in Environment Policy from Cambridge, and his first book, Talking Through Trees, was published by the Old Stile Press in 2017. He believes passionately in the importance of education and outreach, and in the power of art to transform society.

Thomas Eeckhout was born in 1992 and started studying piano at the age of eight at the music academy in Gent with Rolande Spanoghe. At the age of eighteen, he started his studies with Levente Kende, Nikolaas Kende and Heidi Hendrickx at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp, where he also took courses in pianoforte with Piet Kuijken and vocal accompaniment with Lucienne Van Deyck and Jozef De Beenhouwer. In 2016, he graduated with great distinction. In October 2019, soprano Lisa Willems and he were finalists in the Paola Salomon-LindbergCompetition in Berlin. In September 2020, he commenced postgraduate studies in piano accompaniment at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, where he won the Piano Accompaniment Prize. His teachers are Caroline Palmer and Bretton Brown. In September 2022, he became a Junior Fellow at Guildhall. In 2025–26, he will be a Young Artist at the Oxford International Song Festival, along with baritone George Robarts; he will also be performing at the Ludlow Song Festival and Konzerthaus Berlin.

Unveiled: Britten – Tippett – Gipps – Browne – Thomas

Elgan Llŷr Thomas tenor, Craig Ogden guitar, Iain Burnside piano

DCD34293

In Jeremy Sams’ new English-language singing version of Britten’s Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, the passionate sentiments are liberated from the safe historical distance of the Italian Renaissance and unveiled in a way that was not possible in 1940, when Britten wrote the cycle – his first for his partner Peter Pears. Presenting it alongside Tippett’s equally ardent Songs for Achilles and premiere recordings of songs by Ruth Gipps and Elgan Llŷr Thomas himself, the programme tackles themes of love, shame, acceptance, war and death to traverse a history of male homosexuality from necessary discretion to the (relatively) liberated present.

‘Thomas and Burnside do [the Britten] full, impassioned justice, and the Welsh tenor’s own song-cycle SWAN acts as a most effective counterpart.

— Presto Music, April 2023, EDITOR’S CHOICE

A Short Story of Falling

Harriet Burns soprano, Ian Tindale piano

DCD34346

There are many ways to fall and many stories about falling. Long-established duo Harriet Burns and Ian Tindale have a passion for telling these stories, be they metaphorical, literal or mystical. Through a programme ranging from the Victorian era to premiere recordings of works written for them by Christopher Churcher and Derri Joseph Lewis, they explore the topic of ‘falling’ in a playful and eclectic way. In doing so they create a web of connections between themes such as war, power and queerness, highlighting less often heard voices such as Morfydd Owen and Maude Valérie White alongside major composers of the present – including two epic solo pieces, for voice and piano respectively, by Judith Weir.

New in August 2025

Battle Cry: She Speaks

Helen Charlston mezzo-soprano, Toby Carr theorbo DCD34283

This powerful yet understated recital of seventeenth-century and modern works aims to revisit but also to re-balance the obsession of earlier music with female abandonment and lament. The stories of women such as Dido and Ariadne have been told and retold throughout history. Mezzo-soprano Helen Charlston reconsiders the assumed helplessness of those often seen as being left behind by male adventure and success. A recent work commissioned for Charlston from the composer Owain Park further takes up the challenge of giving ‘abandoned women’ their own platform, as well as exploring new possibilities for an instrumental pairing – that of voice and theorbo – that remains little explored in contemporary music.

‘surely one of the most exciting voices in the new generation of British singers’ — Gramophone, June 2022, EDITOR’S CHOICE

Winner (vocal category) — BBC Music Awards 2023

Isolation Songbook

Helen Charlston mezzo-soprano, Michael Craddock baritone, Alexander Soares piano

DCD34253

The feeling of life gone into standstill which so many of us experienced in spring 2020 was especially acute for singers Helen Charlston and Michael Craddock, not only deprived of live concert opportunities but forced to put their April marriage plans on hold. Seeking ways to redirect her creative energies, Helen wrote a poem for Michael to mark their postponed wedding date, and the composer Owain Park, a friend of the couple, set it to music. Helen began to contact other composers and poets, and unexpectedly but quickly a recording project took shape that would both fill the empty time and bear witness to it, with music proving its ability to build connections across physical distance.

‘A recital that’s hard to resist, at once fresh and profoundly familiar’ — Gramophone, March 2021

Dallapiccola: a portrait

David Wilde piano, Susan Hamilton soprano, Nicola Stonehouse mezzosoprano, Robert Irvine cello

DCD34020

Luigi Dallapiccola is one of the most celebrated Italian composers of the twentieth century. This disc features chamber music and songs alongside his complete works for solo piano. Whether drawing on the music of the past to nourish the contrapuntal organisation of his own, or concentrating on the opportunities for gentle lyricism afforded by bell-like instrumental and vocal sonorities, Dallapiccola’s commitment to traditional expressive nuance has been seen by critics as a powerful aspect of his Italian insistence upon cantabilità – songfulness.

‘a marriage of discipline and imagination of which Wilde is fully aware … Susan Hamilton is eloquence itself in the Goethe-Lieder’ — Gramophone, April 2007

Our Indifferent Century: Britten – Finzi – Marsey – Ward

Francesca Chiejina, Fleur Barron; Natalie Burch piano

DCD34311

In 1914 Thomas Hardy wrote of ‘our indifferent century’; a generation later W.H. Auden urgently sought to fuse the political with the creative. Today, profoundly unsettled by the turn of the world’s politics, three artists respond with a programme that explores the changes and challenges we face presently, but one that also offers hope, levity an even a degree of irreverence, and never loses sight of the joy and beauty of nature. Hardy and Auden found their perfect musical counterparts in the songwriting of Finzi and Britten; in our own times William Marsey and Joanna Ward add their own musical voices of political urgency and wistful yearning.

‘thought-provoking, beautifully executed and timely’ — BBC Music Magazine, December 2023

Brindley Sherratt: Fear No More

Brindley Sherratt bass, Julius Drake piano

DCD34313

Brindley Sherratt’s pre-eminence as an operatic bass is the result of two daring career shifts. Initially trained as a trumpeter, it was only in his midthirties that he left the professional security of a position in the BBC Singers to explore the world of opera. Now, the voyage of discovery continues as Sherratt turns to the intimate medium of the song recital. With the superb pianist Julius Drake as collaborator, in Fear No More Sherratt draws on all of his accumulated technical and expressive wisdom in death-haunted songs by Schubert, Mussorgsky and Richard Strauss and a group of five twentiethcentury English songs in which consolation and acceptance are the keynotes.

‘Sherratt’s interpretations have an imposing power all their own, the deep, oaky patina of the voice carrying with it a special emotional weight’ — Gramophone, May 2024

William Walton: Complete Song Collection

Siân Dicker soprano, Krystal Tunnicliffe piano, Saki Kato guitar

DCD34328

‘These Walton songs are really terrific,’ wrote the great accompanist Gerald Moore; ‘everything WW does is impressive – why the devil doesn’t he write more songs?’ From early experiments, via Edith Sitwell settings that build on the success of Façade, to music for the silver screen and two well-loved cycles heard here in their original intimate versions with piano and guitar, the complete collection fits on a single album. But what an album! Four decades after Walton’s death, three imaginative young artists bring fresh voices to the feast, revelling with infectious enjoyment in the composer’s endlessly beguiling inventiveness and sparkling wit.

‘I cannot fault Siân Dicker’s imaginative and sympathetic performances of these songs, and her wide-ranging vocal accomplishments. She is an ideal interpreter of Walton’s music. Equally wonderful is the outstanding accompaniment’ — MusicWeb International, January 2025