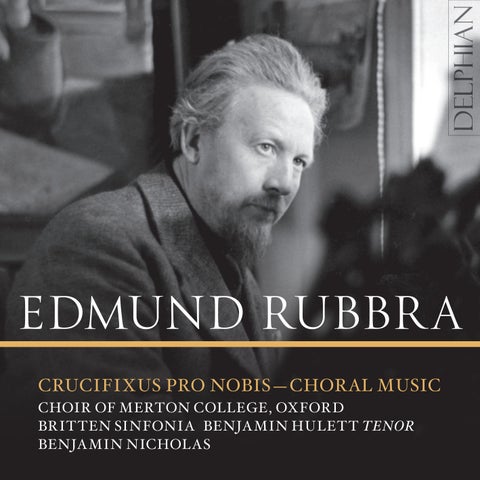

Edmund rubbra

CRUCIFIXUS PRO NOBIS—CHORAL MUSIC

CHOIR OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD

BRITTEN SINFONIA BENJAMIN HULETT TENOR

BENJAMIN NICHOLAS

Edmund Rubbra

(1901–1986)

CHOIR OF MERTON COLLEGE, OXFORD BENJAMIN NICHOLAS

Benjamin Hulett tenor †

Britten Sinfonia †

Thomas Hancox flute

Marcus Barcham Stevens violin

Ben Chappell cello

Sally Pryce harp

François Cloete ‡, Owen Chan organ

Recorded with the kind support of the Rubbra estate With thanks to the Warden and Fellows of the House of Scholars of Merton College, Oxford

Recorded on 23-25 June 2024 in the Chapel of Merton College, Oxford

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Design: John Christ

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Cover photo: Haywood Magee/Picture Post/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Session photography: Will Coates-Gibson/foxbrush

Delphian Records Ltd – Oxford – UK www.delphianrecords.com

Cantata di Camera: Crucifixus pro Nobis Op. 111 *†‡

1 I. Christ in the Cradle [3:29]

2 II. Christ in the Garden [3:09]

3 III. Christ in his Passion

Edward Chesterman solo from the choir [4:54]

4 IV. Most glorious Lord of life [1:57]

5 The Revival Op. 58 * [3:02]

6 Eternitie (Five Motets for Unaccompanied Choir) Op. 37 No. 1 [2:53]

Prelude and Fugue (on a Theme by Cyril Scott) Op. 69

arr. Bernard Rose (1916–1996)

François Cloete organ

7 Prelude [2:10]

8 Fugue [2:41]

9 The Virgin’s Cradle Hymn Op. 3 [1:35]

Missa in Honorem Sancti Dominici Op. 66

10 I. Kyrie [2:14]

11 II. Gloria [3:55]

12 III. Credo

Henry Le Feber Robertson cantor [6:59]

13 IV. Sanctus [1:15]

14 V. Benedictus [1:30]

15 VI. Agnus Dei [1:51]

16 Meditation Op. 79 Owen Chan organ [3:08]

17 A Hymn to God the Father (Five Motets for Unaccompanied Choir) Op. 37 No. 3 [3:43]

18 Symphonic Prelude Op. 164a * arr. Michael Dawney (b. 1942) & Robert Matthew-Walker (b. 1939) Owen Chan organ [1:44] Evening Service in A flat

delphianrecords.com

delphianrecords @ delphian_records

premiere recordings

It was Adrian Boult who cut to the heart of Edmund Rubbra, writing of the composer that he ‘never made any effort to popularise anything he has done, but goes on creating masterpieces’. The musicologist and critic Hugh Ottaway fills out the picture further, speaking of Rubbra’s ‘determination to be himself, regardless of fashions and fetishes’, while the composer Harold Truscott points to the ‘absence from his work of anything in the nature of fireworks or gimmicks’.

A silhouette starts to take shape of a musician apart, defined as yet by what he is not, and does not do. But to paint Rubbra as a blackand-white contrarian would be misleading. A staunch adherent to traditional harmony in an age of avant-garde experimentation, a critic with a keen understanding of serial processes, whose own music unfolds with disarmingly organic ease, Rubbra wasn’t rejecting fashion so much as following his own path: choice did not come into it. ‘The composer’s task’, he wrote, ‘is not the creation of something new, but actually the discovery of something that already exists.’

The discovery of something that already exists could be the subtitle of Rubbra’s biography: an unlikely but persistent journey from working-class Northampton to the heart of the classical establishment. Musical curiosity and conviction seems to have animated

Rubbra from his earliest years in the ‘small, box-like red-brick house’ he shared with his parents, both keen amateur musicians. When he later recalled his childhood, so many of the composer’s keenest memories – an overnight snowfall inverting the morning light on his bedroom wall, distant bells heard while out walking in the fields with his father – coalesced into the sounds and textures of his adult music.

Music was encouraged, but money was essential. Rubbra left school at fourteen to supplement the household’s ‘meagre’ income, fitting his studies in harmony and counterpoint, piano and organ into early mornings and late nights. It was the enterprising seventeenyear-old’s plan to stage a concert of Cyril Scott’s music that proved the turning point – prompting the composer to accept him as a pupil. Scholarships to Reading University and the Royal College of Music followed, as well as studies with Holst, R.O. Morris and occasionally Vaughan Williams (a sometime-substitute whom Rubbra remembered as ‘not a very good teacher’).

Tumbling into professional life in the 1920s before he had even completed his studies – co-opted as pianist to a travelling theatre company – Rubbra became a jobbing musician: teaching privately, playing for ballet rehearsals and writing music criticism. Composing had to fit into any remaining gaps. The 1940s saw

Rubbra called up, channelling his skills into performances for the Army Classical Music Group, before moving into the academic roles that would be a constant through his mature career, principally at Oxford University and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

If the eleven symphonies represent the public face of Rubbra’s music – a vehicle, as the composer put it, ‘for the profoundest abstract statements in music’, then the sacred works offer a window onto the private side of a man for whom faith was the defining force.

‘All his music is about God,’ Harold Truscott wrote, an observation based both on Rubbra’s own all-encompassing view of religion ‘not as a watertight compartment’ but ‘a way of connecting oneself to all creation’, and on the unifying processes at work within his music itself: music that often rejects traditional structures built around opposition and contrast in favour of monothematic development, growing outwards from a single seed.

A recording that includes Rubbra’s earliest published piece (The Virgin’s Cradle Hymn ) as well as the Symphonic Prelude (based on sketches written just a few months before his death) reflects the constant presence of sacred works in Rubbra’s output – touchstones of a life steeped in faith, that progressed from an upbringing in the ‘hymn-singing milieu of the Congregational

Church’ to a Catholic conversion in 1948, a lifelong fascination with Eastern mysticism and metaphysics running alongside.

The Virgin’s Cradle Hymn (1924) is a work of ‘special importance’ for Rubbra: his first to be published, chosen for the Oxford Book of Carols (1928). The composer may still have been a student in his early twenties, but many of his musical fingerprints are already present in this simple, strophic carol. Latin verse, copied by Coleridge from a print ‘found in a German village’, paints an intimate picture of the infant Christ in the manger, his mother smiling tenderly down. Rubbra responds with a gently rocking soprano melody, supported by a lulling accompaniment in the lower voices: the regular inhaling and exhaling of sleeping breath. The delicate modal counterpoint nods not just to Holst and Vaughan Williams but further back to the English Tudor composers.

Composed as Rubbra was on the brink of his First Symphony, Five Motets (1934) was his first major choral work, a significant statement of musical and spiritual intent. All five texts are drawn from the metaphysical poets, with John Donne’s Hymn to God the Father the stark central panel. The opening motet, Eternitie (Robert Herrick) is poised on the brink of life and death. Earth-rooted lower voices bid farewell to bodily life, as the music passes to sopranos and tenors

– carried upwards into cloudy uncertainty. The imitative entries of the Renaissance are set against great architectural blocks of chordal movement: human endeavour assimilated into inexorable spiritual power?

A Hymn to God the Father broods on sin, testing the limits of forgiveness in a series of first-person confessions. Set in six parts, SSAATB, the dense, suggestively chromatic, harmonies are intensified by voices yoked into homophony, moving heavily as one. The first two verses are mirrors of one another, but the third – ‘I have a sin of fear’ – breaks jagged new ground, abandoning the prevailing modal D minor for A flat minor: a strange new harmonic land, ambiguous in its promise.

The metaphysical theme continues with 1944’s The Revival – the first of three premiere recordings here. Where Donne’s poem curves inward in shameful self-examination, Vaughan’s reaches out to the listener directly at the start of two verses that celebrate a return and rekindling of faith – a topic surely of personal significance to a composer who would convert to Catholicism just four years later. The imitative SATB polyphony of the first verse could be a Tallis motet, harmonically stretched and distorted by distance. As the poet’s focus shifts for the second verse – turning to Spring’s return as a mirror to God’s – so does Rubbra’s harmonic centre,

wandering until ‘the Lilies of his love appear’ in an unambiguous final cadence that offers all the certainty A Hymn to God the Father denies.

While the Missa in Honorem Sancti Dominici would shortly mark Rubbra’s advent into Catholicism, his Evening Service in A flat from the late 1940s celebrate the Anglican tradition he was leaving behind. The Magnificat opens arrestingly: primal organ pedals summon the choir into guttural life. Mary’s song of joy takes unusually muscular form, only gradually softening and fragmenting into lyrical imitation for ‘And his mercy’. The mighty and the proud get plenty of scornful, exotic pomp in Rubbra’s parallel movement, before mercy once again melts the texture, leaving just the upper voices.

A Gloria shared with the Nunc Dimittis opens in pealing organ scales (echoes of those distant childhood bells?), playing notorious rhythmic games in the accompaniment – duplets and triplets tugging against one another. All the tensions and bombast of the Magnificat drain away in the Nunc Dimittis, whose unison melody stretches yearningly across bar lines, reaching inexorably towards the pealing outpourings of the Gloria.

On 4 August 1948 – the Feast of St Dominic –Rubbra was received into the Catholic Church. He honoured the saint with a Mass setting: the unaccompanied Missa in Honorem

Sancti Dominici whose six movements were intended for liturgical use, and therefore ‘as succinct’, Rubbra wrote, ‘as I could possibly make them’ – a contrast to the earlier, more expansive, Missa Cantuariensis. But despite its pragmatic concision, the music retains the spark of that ‘inner compulsion’ that inspired the composer to write without a commission – a Mass, as he put it, with ‘red blood’ running through its musical veins.

The block movement of medieval organum and the intricate counterpoint of the Renaissance meet in a Mass rooted in the musical past, but with its harmonic gaze fixed to the future. The work is typical of Rubbra; nothing is strictly new, but it sounds like nothing and no one before. The graphic intensity of the Kyrie, the delicate tracery of the ‘qui venit in nomine’ entries of the Benedictus, and the fluid, inflected speech-song of the Credo all share a common quality – what Robert Saxton has described as a ‘radiance … only won by means of an internal quest’.

The four-movement Cantata di Camera, published in 1961, is recorded here for the first time – its neglect a product perhaps of both unusual instrumentation (solo tenor, sixteenvoice choir, flute, violin, cello, harp and organ) as well as a composite structure that unites a sequence of three continuous settings of poems by the seventeenth-century author

Patrick Carey with an arrangement of the last of Rubbra’s 1935 Sonnets of Spenser (originally scored for solo tenor and string orchestra).

A sequence subtitled ‘Crucifixus pro Nobis’ opens with the infant Christ (‘Christ in the Cradle’), and travels through the confrontation of Gethsemane (‘Christ in the Garden’) and the Crucifixion (‘Christ’s Passion’) before arriving in triumphant resurrection with Edmund Spenser’s ‘Most Glorious Lord of Life’. The solo tenor is our guide and constant through the movements, a still observer who sings a chilly lullaby over Jesus, shivering harp to the fore in the accompaniment. Strings usher in a more expansive, heightened vision of Gethsemane, melismas in the vocal part wringing the blood and sweat from Carey’s unabashedly melodramatic text. The choir join the tenor at the foot of the cross in the third movement, before pulling us out of the action in an unaccompanied chorale that – for the first time – invites us not to just to listen but question: ‘Why, O why, suffered he?’ Repetition drives this question painfully home. The answer comes in the form of the final movement: a celebration of Christ ‘triumphant over death’, a lively, quasi-courtly dance after three movements of anguished contemplation.

Surprisingly for a composer of such spiritual conviction, solo organ music isn’t substantially represented in Rubbra’s output. Two of this

recording’s three works are in fact borrowings and adaptations; only the Meditation represents Rubbra’s original thinking.

The earliest harks back to the composer’s musical beginnings. The Prelude and Fugue on a Theme by Cyril Scott (originally written in 1950 for piano, transcribed for organ by Bernard Rose) was Rubbra’s seventiethbirthday gift to his former teacher. Based on a theme from Scott’s Piano Sonata No. 1, the Prelude supplies a supple, original countermelody for Scott’s own subject, while the Fugue showcases Rubbra’s overflowing kit-bag of contrapuntal skills in a masterly manipulation of its subject in the tradition of Bach. Meditation (1953) couldn’t be in greater contrast: a rapt, contemplative work rooted to the harmonic spot by a pedal C that supplies the anchor around which the composer weaves ornamental gestures that nod to the sixteenth century.

The last of this recording’s organ works is also its third premiere – a curiosity that represents some of Rubbra’s final musical thoughts.

At his death in 1986 the composer was working on a Twelfth Symphony. Just two pages of the manuscript survive in short score, arranged by the composers Michael Dawney (a former pupil of Rubbra’s) and Robert Matthew-Walker and published as the Symphonic Prelude in 1990. The result is a brooding musical premonition: a gaze into the beyond that grasps one more time – as all Rubbra’s music seeks to – after ‘the Divine forces that shape all existence’.

© 2026 Alexandra Coghlan

Alexandra Coghlan is a music journalist and critic. She has written for publications including the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, I Paper, Prospect, the Spectator, Opera and Gramophone.

Cantata di Camera: Crucifixus pro Nobis

1 I. Christ in the Cradle

Look, how he shakes for cold! How pale his lips are grown! Wherein his limbs to fold Yet mantle has he none. His pretty feet and hands (Of late more pure and white Than is the snow That pains them so) Have lost their candour quite. His lips are blue (Where roses grew), He’s frozen everywhere: All th’ heat he has Joseph, alas, Gives in a groan: or Mary in a tear.

2 II. Christ in the Garden

Look, how he glows for heat! What flames come from his eyes! ’Tis blood that he does sweat, Blood his bright forehead dyes: See, see! It trickles down: Look, how it showers amain! Through every pore His blood runs o’er, And empty leaves each vein. His very heart Burns in each part;

A fire his breast doth sear: For all this flame, To cool the same He only breathes a sigh, and weeps a tear.

3 III. Christ in his Passion

What bruises do I see!

What hideous stripes are those! Could any cruel be Enough to give such blows?

Look, how they bind his arms And vex his soul with scorns, Upon his hair They make him wear A crown of piercing thorns. Through hands and feet Sharp nails they beat: And now the cross they rear: Many look on; But only John Stands by to sigh, Mary to shed a tear.

Why did he shake for cold? Why did he glow for heat? Dissolve that frost he could, He could call back that sweat. Those bruises, stripes, bonds, taunts, Those thorns, which thou didst see, Those nails, that cross, His own life’s loss, Why, oh, why suffered he? ’Twas for thy sake.

Thou, thou didst make Him all those torments bear: If then his love

Do thy soul move, Sigh out a groan, weep down a melting tear.

Patrick Carey (c.1624–1657)

4 IV. Most glorious Lord of life

Most glorious Lord of life, that on this day, Didst make thy triumph over death and sin: And having harrowed hell, didst bring away

Captivity thence captive us to win:

This joyous day, dear Lord, with joy begin, And grant that we for whom thou diddest die, Being with thy dear blood clean washed from sin, May live for ever in felicity. And that thy love we weighing worthily, May likewise love thee for the same again: And for thy sake that all like dear didst buy, With love may one another entertain. So let us love, dear love, like as we ought, Love is the lesson which the Lord us taught.

Edmund Spenser (1552–1599), Amoretti LXVIII

5 The Revival

Unfold! unfold! Take in his light, Who makes thy cares more short than night.

The joys which with his daystar rise, He deals to all but drowsy eyes;

And (what the men of this world miss)

Some drops and dews of future bliss.

Hark! how his winds have changed their note, And with warm whispers call thee out. The frosts are past, the storms are gone, And backward life at last comes on.

The lofty groves in express joys Reply unto the turtle’s voice; And here in dust and dirt, O here The lilies of his love appear!

Henry Vaughan (1621–1693)

6 Eternitie

O Yeares! and Age! Farewell: Behold I go, Where I do know Infinitie to dwell.

And these mine eyes shall see All times, how they Are lost i’ th’ Sea Of vast Eternitie. Where never Moone shall sway The Starres; but she, And Night, shall be Drown’d in one endlesse Day.

Robert Herrick (1591–1674)

9 The Virgin’s Cradle Hymn

Dormi, Jesu! mater ridet

Quae tam dulcem somnum videt, Dormi, Jesu, blandule!

Si non dormis, mater plorat Inter fila cantans orat, Blande, veni, somnule!

Sleep on, Jesus! Mother smiles to see such sweet sleep.

Sleep on, Jesus, sweet little one!

If you don’t sleep, Mother will cry, and pray, singing amid her needlework: Come, sweet little sleep!

From an engraving by Hieronymus Wierix (1553–1619); text reprinted in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Sibylline Leaves (1817)

Missa in Honorem Sancti Dominici

10 I. Kyrie Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison.

Lord have mercy. Christ have mercy. Lord have mercy.

11 II. Gloria

Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. Laudamus te. Benedicimus te. Adoramus te. Glorificamus te. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe; Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe. Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will. We praise you. We bless you. We worship you. We glorify you. We give you thanks for your great glory.

Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty.

Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father:

Who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us. Who takes away the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy upon us. For only you are Holy, only you are Lord, only you are Most High, Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

et Filio simul adoratur et conglorificatur, qui locutus est per prophetas. Et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam. Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum, et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum, et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen.

13 IV. Sanctus

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus.

Dominus Deus Sabaoth: Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Hosanna in excelsis.

17 A Hymn to God the Father

Wilt thou forgive that sinne where I begunne, Which was my sin, though it were done before?

Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem, factorem caeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, filium Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula, Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine, Deum verum de Deo vero. Genitum non factum, consubstantialem Patri; per quem omnia facta sunt. Qui propter nos homines et propter nostram salutem descendit de caelis. Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria Virgine; et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die secundum scripturas, et ascendit in caelum, sedet ad dexteram Patris, et iterum venturus est cum gloria iudicare vivos et mortuos, cuius regni non erit finis. Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum et vivificantem, qui ex Patre Filioque procedit, qui cum Patre

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages. God of God, light of light, true God of true God; begotten, not made; consubstantial with the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. He was crucified also for us, suffered under Pontius Pilate, and was buried. On the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven. He sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead. And his kingdom shall have no end. I believe in the Holy Ghost, Lord and giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son, who together with the Father and the Son is worshipped and glorified, who spoke through the prophets. I believe in one holy catholic and apostolic church. I confess one baptism for the remission of sins. And I await the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth.

Heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

14 V. Benedictus

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini: Hosanna in excelsis.

Blessed is he that comes in the name of the Lord: Hosanna in the highest.

15 VI. Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.

Lamb of God, who take away the sins of the world, grant us peace.

Wilt thou forgive those sinnes through which I runne,

And do run still: though still I do deplore? When thou hast done, thou hast not done, For, I have more.

Wilt thou forgive that sinne which I’have wonne

Others to sinne? and, made my sinne their doore?

Wilt thou forgive that sinne which I did shunne

A yeare, or two: but wallowed in, a score?

When thou hast done, thou hast not done, For, I have more.

I have a sinne of feare, that when I have spunne

My last thred, I shall perish on the shore; But sweare by thy selfe, that at my death thy sonne

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore;

And, having done that, thou hast done, I feare no more.

John Donne (1572–1631)

12 III. Credo

Evening Service in A flat

19 Magnificat

My soul doth magnify the Lord: and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour.

For he hath regarded the lowliness of his handmaiden.

For behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath magnified me, and holy is his name.

And his mercy is on them that fear him throughout all generations.

He hath shewed strength with his arm: he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seat: and hath exalted the humble and meek. He hath filled the hungry with good things: and the rich he hath sent empty away. He remembering his mercy hath holpen his servant Israel:

as he promised to our forefathers, Abraham and his seed for ever.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost.

As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end. Amen.

20 Nunc dimittis

Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace: according to thy word. For mine eyes have seen thy salvation: which thou hast prepared before the face of all people; to be a light to lighten the gentiles: and to be the glory of thy people Israel.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost.

As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end. Amen.

Described by Gramophone as ‘one of the UK’s finest choral ensembles’, the Choir of Merton College, Oxford is known as one of the most exciting University choirs in the country. In addition to services in the thirteenth-century chapel during term, an extensive touring schedule has seen the choir perform in the USA, Hong Kong, Singapore, France, Germany, Italy, Denmark and Sweden. In 2016, the choir sang the first Anglican service in St Peter’s Basilica, Rome, which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Merton College Choir has performed with many major ensembles, including recent concerts with The King’s Singers, Britten Sinfonia and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

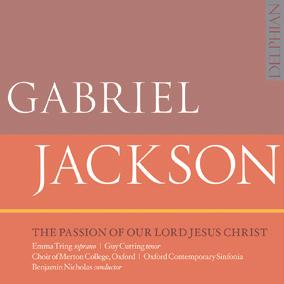

The choir has recorded extensively with Delphian, winning the highest critical praise; in 2020, the choir won a BBC Music Magazine Award for its recording of Gabriel Jackson’s The Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ (DCD34222). Recent recordings include two volumes of English orchestral anthems with Britten Sinfonia (DCD34291/34351). On Good Friday, 2023 the choir made its debut at London’s Barbican with a performance of Bach’s St John Passion.

Benjamin Nicholas is Reed Rubin Organist and Director of Music at Merton College, Oxford and Music Director of The Oxford Bach Choir. He has held posts at Chichester and St Paul’s Cathedrals and was Director of the Edington Music Festival. Prior to moving to Merton College, he was, for twelve years, Director of Tewkesbury Abbey Schola Cantorum.

As a conductor, Benjamin Nicholas has appeared with the Philharmonia, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the London Mozart Players and The BBC Singers, and has premiered the works of numerous composers including Birtwistle, Dove, MacMillan, McDowall, Rutter and Weir. His recording of Elgar’s organ music (Delphian DCD34162) was an Organists’ Review Editor’s Choice.

Tenor Benjamin Hulett studied at New College, Oxford and at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. He has sung for the Royal Ballet and Opera; the Wiener Staatsoper; Hamburgische Staatsoper; Bayerische Staatsoper; Deutsche Staatsoper; La Scala, Milan; Opéra de Lille, Opéra National de Lyon, the Teatro Real in Madrid and at the Glyndebourne, Salzburg, Edinburgh and Baden-Baden festivals.

In concert his appearances include the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Boston Symphony Orchestras under Charles Dutoit; the Montreal Symphony Orchestra under Kent Nagano; Salzburg Mozartwoche under Ivor Bolton; Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under John Wilson and the Berliner Philharmoniker under Sir Simon Rattle, Sir Roger Norrington, Emmanuelle Haïm, Trevor Pinnock, Christopher Hogwood and Vladimir Jurowski. His recital appearances include London’s Wigmore Hall and the Aldeburgh, Buxton, Oxford Lieder and Leeds Lieder festivals and his many recordings have received nominations and awards from BBC Music Magazine, Gramophone, the Grammys, L’Orphée d’Or and Diapason.

Britten Sinfonia creates impactful and inspirational musical experiences, whether through its adventurous programming and innovative formats – such as its immersive Surround Sound Playlist – or its projects created especially for school pupils, hospital patients and local communities.

Rooted in the East of England, where it is the only professional orchestra working throughout the region, Britten Sinfonia also has a national and international reputation as one of today’s finest ensembles. ‘Innovative as always’ (Guardian, 2025), it is equally renowned for the remarkable breadth of its collaborations – from Steve Reich, Mahan Esfahani and Alison Balsom to Anoushka Shankar, Jacob Collier and Pagrav Dance Company – and for its nurturing of new compositional voices: over three decades, Britten Sinfonia has premiered more than 250 new works.

Britten Sinfonia’s main concert activity is in London, Saffron Walden, Cambridge and Norwich, and it also performs in Bury St Edmunds, Ely, Peterborough and Chelmsford. The orchestra often performs at London’s Wigmore Hall and appears at UK festivals including Aldeburgh, Brighton, Norfolk & Norwich and the BBC Proms. Its prolific discography features numerous award-winning recordings.

Choir of Merton College, Oxford on Delphian

Orchestral Anthems Vol. 2:

Choir of Merton College, Oxford; Britten Sinfonia / Benjamin Nicholas DCD34351

The Choir of Merton College reunites with Britten Sinfonia to explore some much-loved Anglican repertoire in its full orchestral splendour. Stanford in A, as it was originally heard in 1880, reveals its symphonic side, not least in the masterful and eloquently scored Nunc dimittis Walton’s The Twelve matches W.H. Auden’s striking and dramatic poetry with typically dynamic vocal and instrumental writing; Ireland’s Greater love and Wesley’s mighty Ascribe unto the Lord bring to the anthem tradition a richness of harmony and orchestral colour to which Benjamin Nicholas’s combined forces do full-blooded justice.

‘soaring melodic lines which, for me, enrich and uplift the soul … a beautifully put together album, which puts a totally different light on everything’ — BBC Radio3, Record Review, June 2025

Ian Venables: Requiem; Howells: anthems for choir & orchestra

Choir of Merton College, Oxford; Oxford Contemporary Sinfonia; Benjamin Nicholas conductor & solo organ DCD34252

Ian Venables’ Requiem, warmly received at its 2020 premiere with organ accompaniment, is heard here in an orchestrated version made specially for this recording. Conductor Benjamin Nicholas draws parallels between Venables’ work and the familiar English choral sound of Herbert Howells, whose work is also heard here in unfamiliar orchestrated versions – new arrangements of two of his Four Anthems by Howells scholars Howard Eckdahl and Jonathan Clinch, and the first recording of Howells’ original orchestration of The House of the Mind.

‘The fresh-voiced young singers of the Choir of Merton College sing quite gloriously with perfect balance, blend and intonation’ — MusicWeb International, October 2022, RECORDINGS OF THE YEAR

Orchestral Anthems: Dyson | Howells | Elgar | Finzi

Choir of Merton College, Oxford; Britten Sinfonia / Benjamin Nicholas DCD34291

For the Choir of Merton College, Oxford’s first collaboration with Britten Sinfonia, Benjamin Nicholas has brought together a collection of sacred works from the first half of the twentieth century. A littleknown fact is that these stalwarts of the English repertory were either originally intended to be heard with orchestra, or subsequently orchestrated by their composer or a close colleague. Written for enthronements, coronations and the nation’s grandest choral festivals, these national ‘standards’ are here brought back to life in Delphian’s largest recording to date, their orchestral accompaniments affording them the richness, pomp and majesty associated with their epoch.

‘Nicholas maintains excellent control of his forces in a recording that is sonorously generous and forward in sound ... Britten Sinfonia play a colourful and sensitive role’ — Gramophone, August 2023

Gabriel Jackson: The Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ

Emma Tring soprano, Guy Cutting tenor ; Choir of Merton College, Oxford; Oxford Contemporary Sinfonia / Benjamin Nicholas DCD34222

Strikingly coloured and richly imaginative, Gabriel Jackson’s re-telling of the age-old story of Christ’s betrayal and crucifixion interweaves biblical narrative, English poetry and Latin hymns, culminating in a rare setting of poetry by T.S. Eliot – himself an alumnus of Merton College, Oxford, which commissioned the present work. It is heard here under the direction of long-time Jackson collaborator Benjamin Nicholas, and with soloists and instrumentalists handpicked by the composer.

‘This outstanding recording bursts with energy ... Jackson’s engaging score is richly colourful and his instrumental writing proves a particular highlight’ — BBC Music Magazine, June 2019, CHORAL & SONG CHOICE

Choral Award Winner