Love language by James Fox-Smith 6

REFLECTIONS

8 NOTEWORTHIES

New monuments in Pointe Coupée, Mississippi monsters, free entrance to museums & 225 Theatre Collective’s new home

30

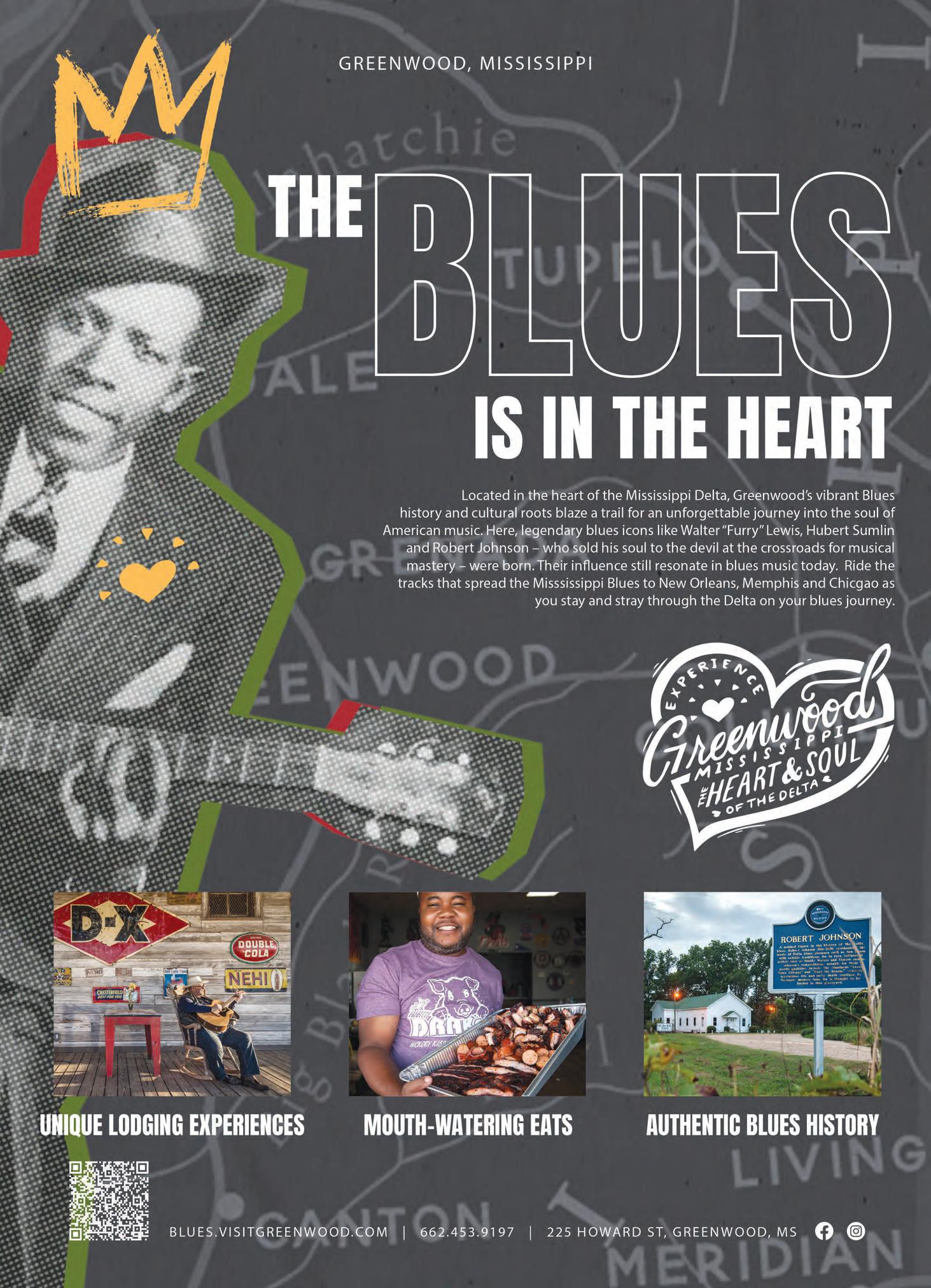

BRING IT ON HOME

Dustin Dale Gaspard on ancestry, language, and singing Cajun French for America by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

BATON ROUGE GOTTA HAVE A BAND

35

More than a century in the making, the Capital City’s concert band marches on, strong as ever by Sam Irwin

THE FIRST OF THEIR NAME

The Holiday Playgirls and the sacred work of playing Cajun music true by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

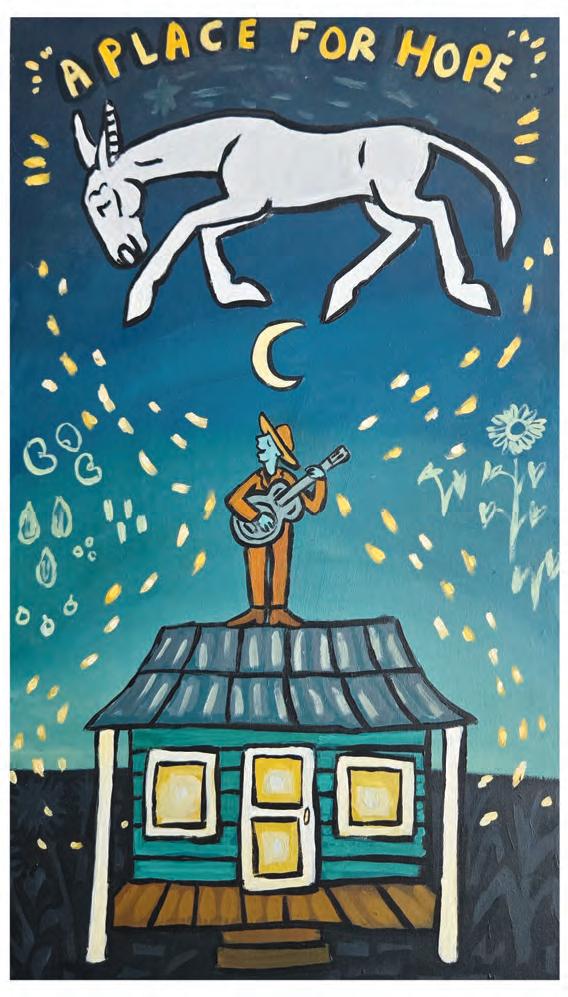

“A PLACE FOR HOPE”

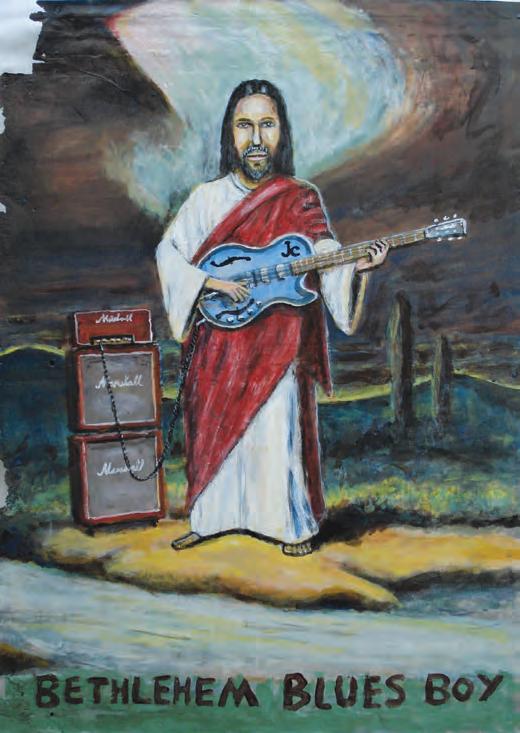

Artwork by Marshall Blevins

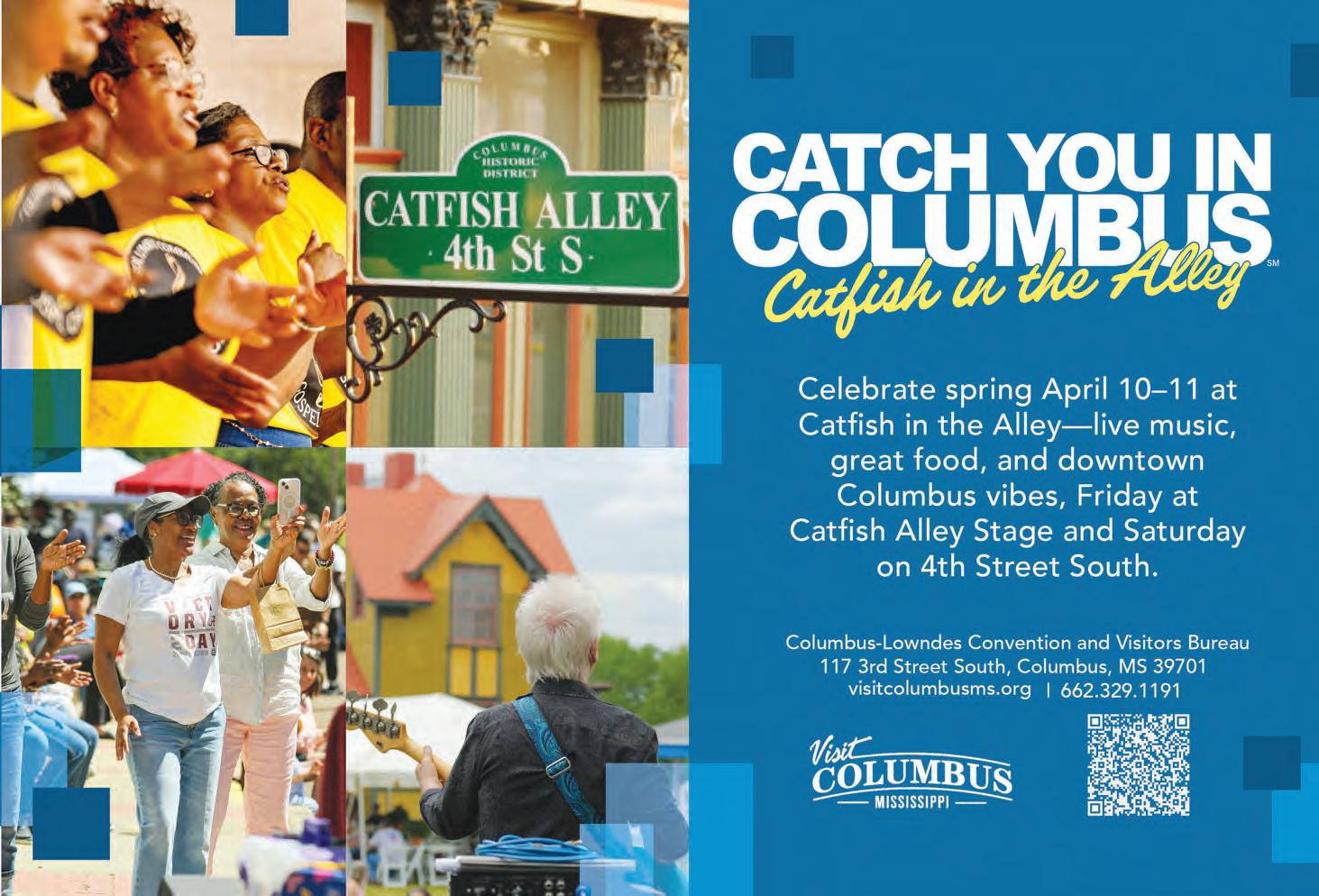

When Dustin Dale Gaspard first received word that he might get the opportunity to compete on the NBC reality show, The Voice, he stepped out beneath the stars. He looked up and he prayed to his Vermilion Parish ancestors, and he told them, “I’m ready.”

In the original version of Marshall “Church Goin’ Mule” Blevins’s artwork, above her signature mule—a symbol of common ground, of shared experiences the likes of those provoked by the blues—appear the words, “A place for hope.”

Gaspard, in his interview on page 30, speaks of a particular place he’s always reaching for when he plays music: a place of conviction, and vulnerability, and yearning, “where other people are invited in.” Renée Reed and Juliane Mahoney allude to it, too, in their own practice playing old Cajun music as The Holiday Playgirls. “There’s this release … it’s passionate. Cajun people, they’re passionate, and they’re heartbroken.” And you can hear it. It’s something shared, between the player and the listener, between all of us. There is hope in it, surely. But maybe what it actually is, is home.

Veracruz Coastal Mexican brings new distinctions to Baton Rouge’s dining scene by Lucie Monk Carter

SOUPÇON

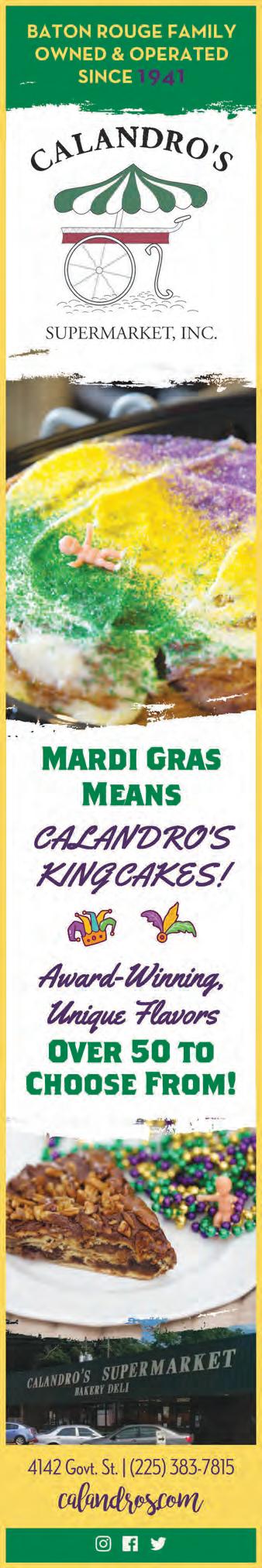

Mr. Weatherall’s king cake crawl, a call for gas station gourmet & more by CR staff 39

THOUGHTS ON IRISES

The beauty of botanical obsessions

42 HOMEGROWN HOOTENANY

The Louisiana Grandstand imagines a new future for Shreveport’s music scene by Chris Jay

43 THE IRISH GOODBYE

A book review by Chris Turner-Neal

44 THE MYSTERY OF “THE FREEZE”

And how to help solve it by Megan Broussard Maughan

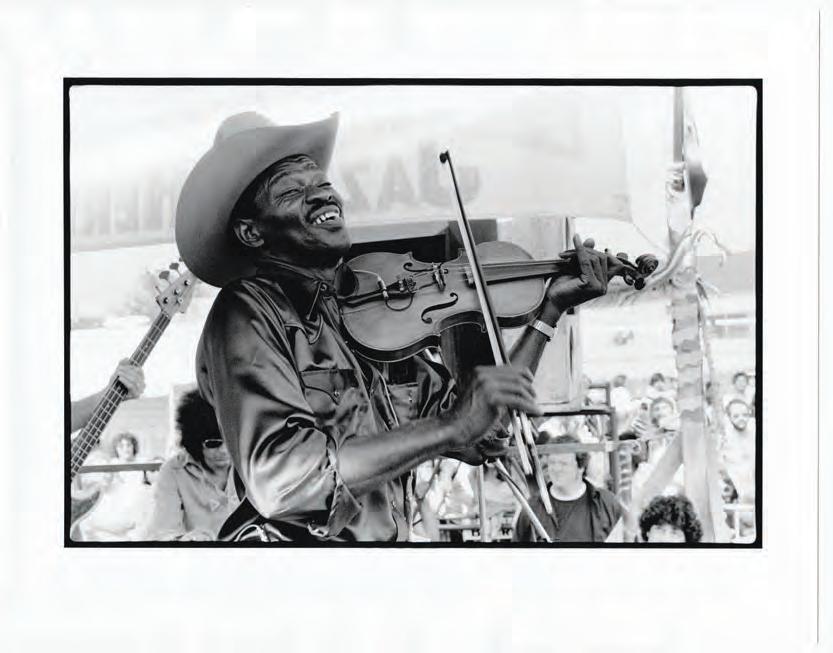

46 FIDDLING IS STILL OUR JOY

A living history of Black fiddling in America, and a playlist to boot by Dom Flemons

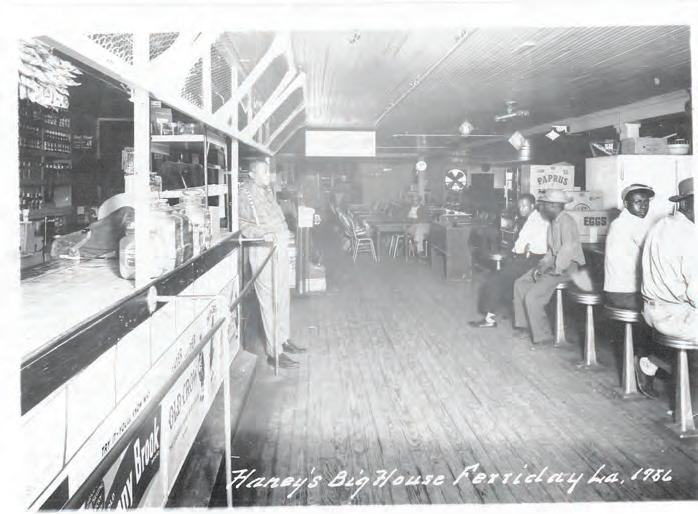

48 THERE IS A HOUSE IN NEW ORLEANS

An old Southern warning, still echoing by James Taylor Foreman

50 DOWN THE ROAD, THE MUSIC’S PLAYING

A music museum roadtrip through Louisiana by Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

54

WUNDERBOB

An outsider artist and musician you likely have never heard of, unless you’re from Germany by Chris Jay

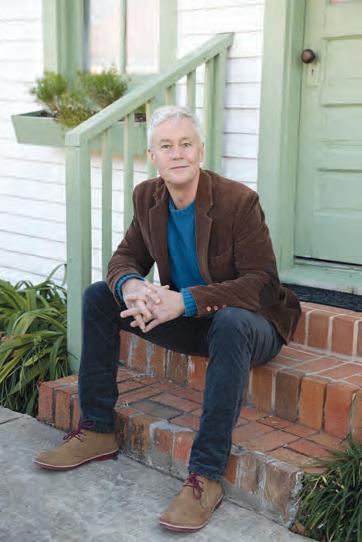

Publisher James Fox-Smith

Associate

Publisher

Ashley Fox-Smith

Managing Editor Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

Arts & Entertainment

Editor

Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

Creative Director Kourtney Zimmerman

Contributors:

Brooke Broussard, Megan Broussard Maughan, Jess Cole, Dom Flemons, Sean Gasser, Sam Irwin, Chris Jay, Lucie Monk Carter, James Taylor Foreman, Chris Turner-Neal

Cover Artist

Marshall Blevins

Advertising

SALES@COUNTRYROADSMAG.COM

Sales Team

Heather Gammill, Heather Gibbons, Mary Margaret Lindsey

Operations Coordinator Molly C. McNeal

President Dorcas Woods Brown Country Roads

the views of the publisher, nor do they constitute an endorsement of products or services herein. Country Roads magazine retains the right to refuse any advertisement. Country Roads cannot be responsible for delays in subscription deliveries due to U.S. Post Office handling of third-class mail.

FROM THE PUBLISHER

To celebrate this season of love, my wife and I have been invited to a Valentine’s gift exchange party. If you grew up in America, perhaps you don’t need the rules of a Valentine’s gift exchange explained. But I didn’t, and apparently, I do. To this event I’m told that each attendee is expected to bring enough tasteful and appropriate tokens of affection to ensure that no-one on the guest list goes home feeling under-loved. My wife, a champion gift-giver and an incurable romantic, seems delighted by the challenge of coming up with perfect gifts for a couple of dozen fellow citizens. I on the other hand, as someone with a bit of a blind spot for the etiquette of appropriate gift-giving, find the whole prospect quite intimidating. That our union has endured all these years is probably proof that the opposing forces of yin and yang are the only things holding the universe together in the first place.

I can’t conjure up any childhood memories of Valentine’s Day at all, besides a vague sense that there was a language in use that I didn’t fully comprehend. Perhaps this was a result of being raised by “no-romanceplease-we’re-British” parents. Or perhaps it’s because you Americans started learning to speak that language in grade school, when the members of the Australian all-boys’ school I attended were still out on the playground, hitting each other with cricket bats. My wife tells me that by the time she was in elementary school, Valentine’s Day was already part of the curriculum. In second or third grade, she recalls spending weeks filling hand-made cards with sweet nothings for her friends and classmates, then arriving on the big day bearing an elaborately decorated shoebox, with a mail slot cut in the top for receiving reciprocal expressions of affection. By middle school, when the training wheels started coming off the whole romance thing and her contemporaries moved on from homemade cards to teddy bears and heart-shaped boxes of chocolates, the little girl with frizzy blonde hair and coke bottle

glasses, finding her shoebox lighter on professions of love than she might have wished, set about perfecting the art of thoughtful, nuanced, occasionally passive-aggressive gift-giving. For an oblivious young husband recently arrived from overseas and imperfectly schooled in the etiquette of Southern gifting, this meant spending early years hopping through an unfamiliar cultural landscape—foot wedged in mouth— where each unfamiliar national holiday, celebration, or life milestone might bring the expectation of gift-giving. But which holiday? And what gift? And to whom should it be given?! In such a landscape, learning the importance of ignoring statements such as, “You don’t need to get me anything big for Valentine’s

Day,” took me longer than it should have done.

Still, given time, patience, and repetition, even the most emotionally stunted student makes progress eventually. So, I hope that my wife will agree that the long journey to spousal enlightenment has been one worth sharing (and not only because the responsibility for coming up with appropriate gifts falls to someone besides me). Among many lessons we have learned during thirty years of married life is that measuring Valentine’s Day or any other celebration by the quality of the gift is missing the point. What seems most special about this upcoming gathering is that, on some level, it hearkens back to an earlier, pre-adult concept of affection—one that preferences good company, shared experience, kindness; and, now we’ve become people-of-a-certain-age, the very real benefits of having been together for a long, long time. Now, I’m off to buy a box of chocolates.

Still trying to get the hang of this, I remain,

—James Fox-Smith, publisher james@countryroadsmag.com

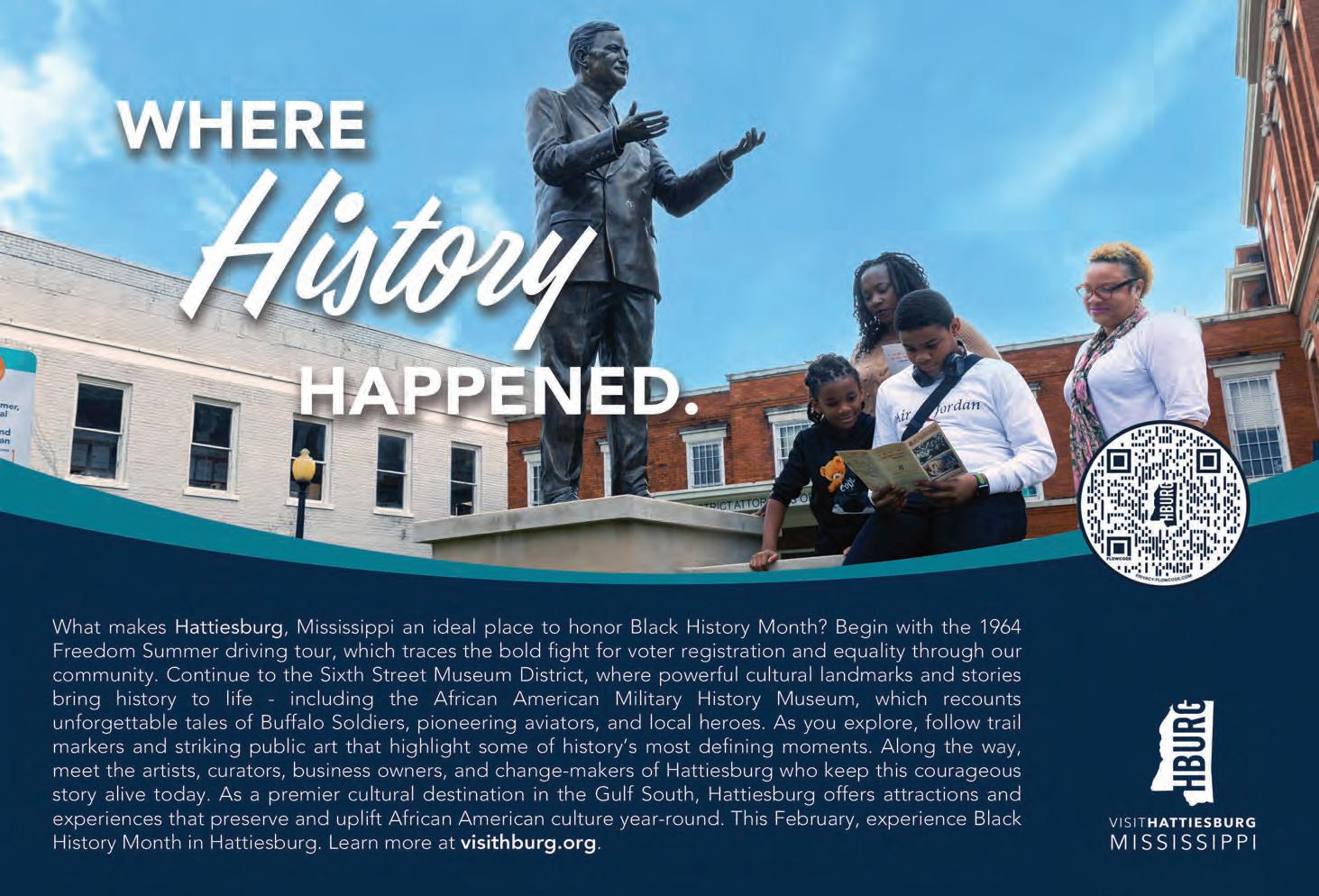

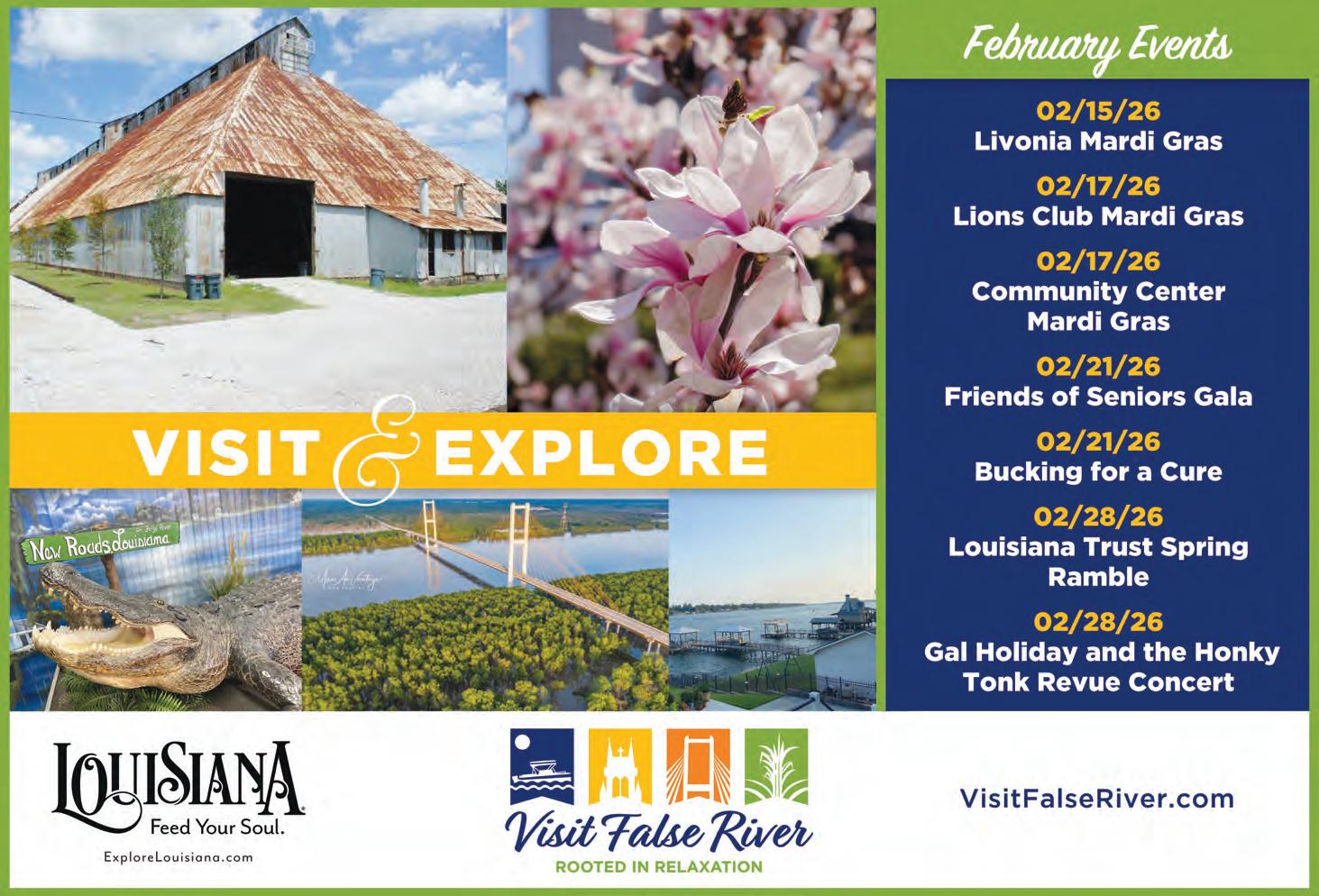

POINTE COUPÉE PARISH COMMEMORATES THE 1927 GREAT FLOOD AND HONORS THE OAK THAT INSPIRED ERNEST J. GAINES

Ihn recent months, Pointe Coupée Parish has gathered its cultural engines around two sites of hishtoric significance—first, a memorial of one of America’s most devastating natural disasters, the other a place of inspiration for one of our country’s most profound literary voices.

On December 16, 2025, community members gathered at the Pointe Coupée Museum in New Roads to dedicate the very first official historic marker commemorating the upcoming centennial of the 1927 Mississippi River Flood.

A two-year initiative by the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation (LTHP), the Great Flood Centennial project aims to work with communities along the Mississippi Delta to remember, document, and interpret the longstanding impact of the greatest flood in American history—which engulfed 23,000 square miles across the Mississippi River Valley. In addition to the hundreds of deaths and thousands of individuals displaced in the flood’s immediate aftermath, lasting effects included new legislation, population and economic shifts, the establishment of modern levee and transportation systems, and environmental and cultural losses.

“There are so many stories within our communities that were impacted by the flood,” said Kriston McCullum, the project manager for The Great Flood Project at LTHP. “One of our goals is to highlight and make visible these stories from individuals and communities.”

To achieve this, LTHP has created a collaborative digital archive of written stories, oral tellings, photos, videos, and other ephemera telling the many stories of the flood, and invites organizations and individuals to contribute.

The other major branch of this project is the historical marker program—officially launched with the Pointe Coupée marker, which recognizes the parish as the site of the last levee breach of the 1927 flood. The marker itself, designed by local artist Joel Breaux, is a tall aluminum pole with a spun funnel on top, which will collect rainwater. A gauge on the marker will indicate the floodwaters’

depth during 1927, and a compass at the foot of the installation provides historical facts on other nearby impacted sites.

McCullum said the hope is more communities will invest in historical markers to commemorate their own stories of the flood, as well as collaborate with the Great Flood Project to create specialized programming, events, and exhibitions leading up to the centennial in 2027.

Follow False River five miles east, and you’ll find the parish’s other newly recognized historic site right beneath a fourhundred-year-old oak tree, one of the legendary survivors of the 1927 flood. Known colloquially as the “Miss Jane Pittman Oak,” the tree served as inspiration for the Louisiana literary icon, Ernest J. Gaines, in his 1971 novel The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman

A landmark of Gaines’s own youth, which he passed daily walking from his home at River Lake Plantation, the tree gained immortality as a symbol of endurance for Gaines’s character, Miss Jane.

In October of 2022, the original historical marker—dedicated earlier that year—was stolen and never recovered. Four years later, on January 18, 2026, thanks to the joint efforts of the Pointe Coupée Historical Society, the Albert Family Foundation, the Curet Family, and donors of the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, a new marker was finally purchased and installed to recognize the tree’s historical, literary, and spiritual significance to the region.

“What a wonderful time to be alive to pause and celebrate the life and legacy of our native son, Ernest J. Gaines and the Miss Jane Pittman Oak,” said Katrice Albert. “The replacement and rededication of this important historical marker allows us to remember his literary excellence and his enduring love for Pointe Coupée. For citizens and visitors alike, it educates us about our cultural heritage, creates a sense of place and pride, and preserves the stories of our people and our community.

Learn more about the Great Flood Project at 1927flood.lthp.org. Visit the new markers at the Pointe Coupée Museum and at 11850 LA-416 Lakeland, LA 70752. —Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

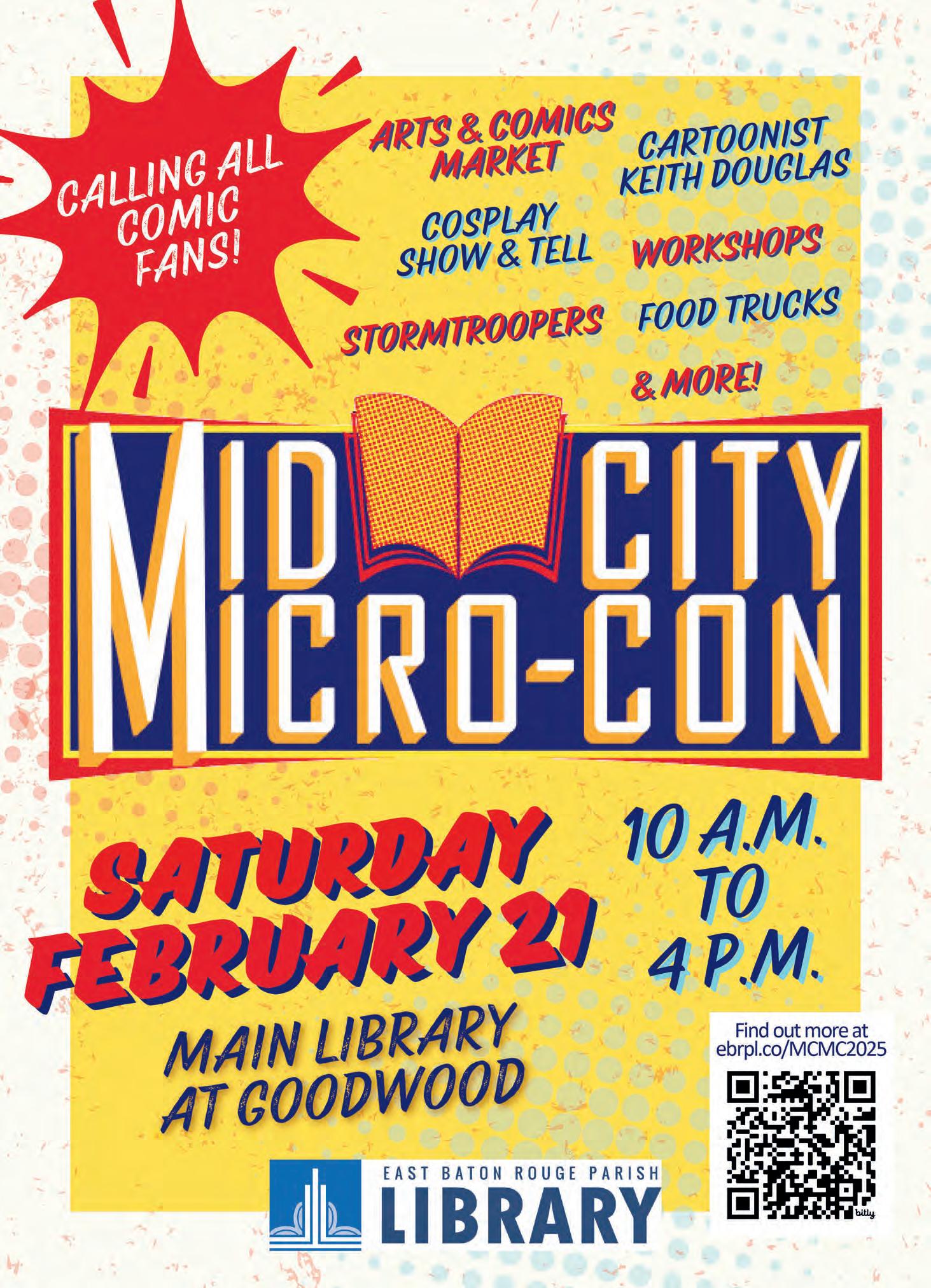

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH LIBRARY CARDHOLDERS NOW HAVE (EVEN MORE) ACCESS TO THINGS BEYOND BOOKS

Looking for ways to make the most of—and support—your local library? Just in time for spring, the East Baton Rouge Parish Library recently announced it has joined the State Library of Louisiana’s “Check Out Louisiana Museums” program.

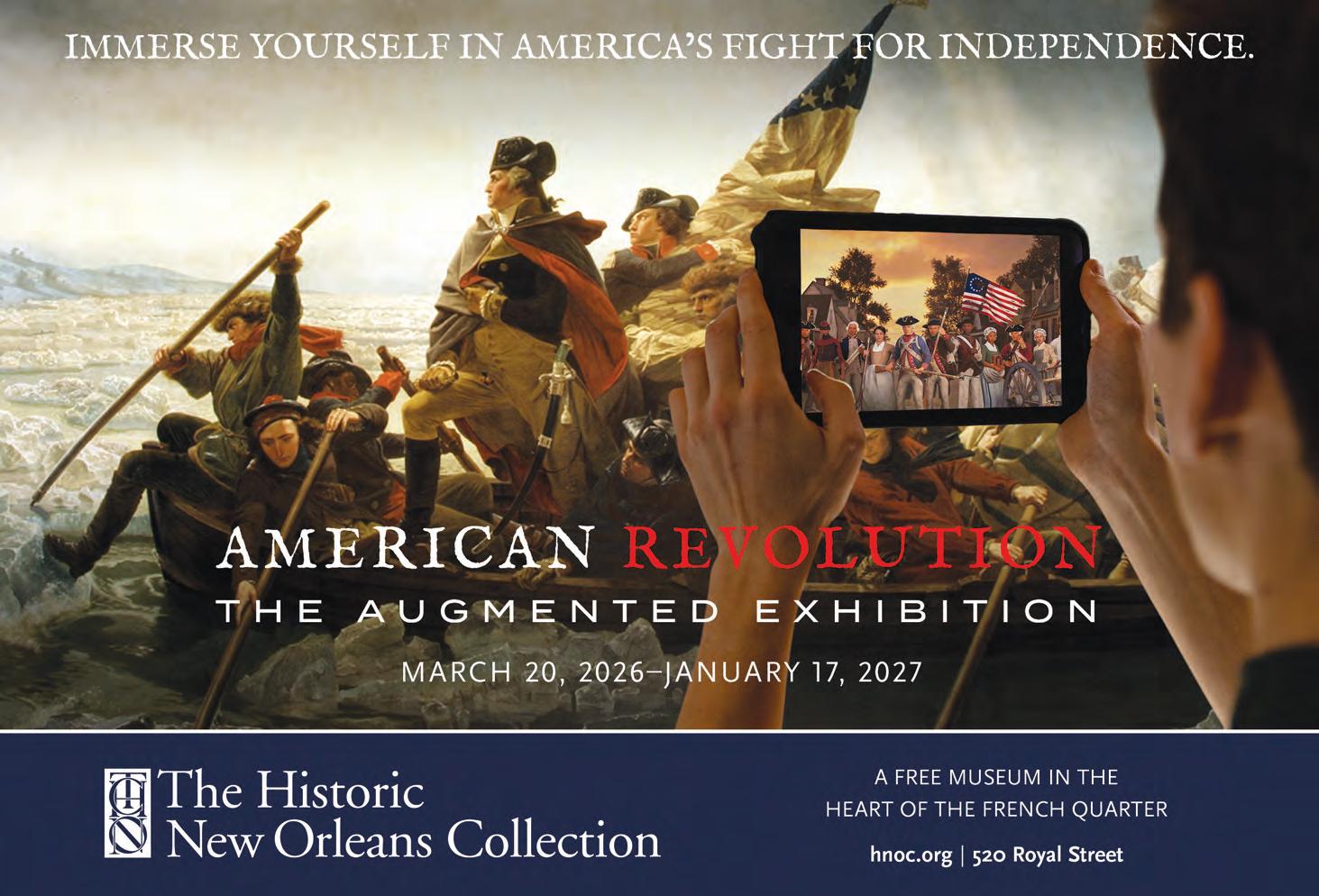

Now, cardholders will be granted free access to Louisiana museums and cultural attractions across Louisiana. These include: the 1850 House, The Cabildo, Capitol Park Museum, E.D. White Historic Site, Louisiana Civil Rights Museum, Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame & Northwest Louisiana History Museum, The National WWII Museum, New Orleans Jazz Museum at the Old U.S. Mint, The Presbytére, Wedell-Williams Aviation & Cypress Sawmill Museum, Alexandria Museum of Art, The Historic New Orleans Collection (Tour), Pontchartrain Conservancy: New Canal Lighthouse, West Baton Rouge Museum, and the Whitney Plantation Museum.

This new partnership comes as the East Baton Rouge Library asks voters to continue its previous millage, which expired in 2025. Now, the library has proposed a stand-alone, dedicated tax of 9.5 mills to fund almost 100% of the system over the next decade. Notably, this proposition is a lower rate than previous measures approved in 1995, 2005, and 2015.

“We examined the fresh information as it became available to us, we studied the statistical data we carefully collected over time, and we listened to you, our community stakeholders,” said Library Director Katrina Stokes. “With this millage, EBRPL will continue to provide the excellent services our community deserves, while fully funding the Capital Improvements Plan, which protects the public's investment."

Reserve your pass at checkoutlouisiana.org.

—Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

If you think of the Mississippi River as a superhighway that connects Louisiana and the entire hMississippi Valley with global agricultural trade, then the LSU AgCenter’s recent receipt of $1 million in federal funding to combat invasive species makes good sense. The funding, which was secured by U.S. Rep. Julia Letlow of Louisiana’s 5th Congressional District with assistance from members of the state’s congressional delegation, enables the creation of the Mississippi River Invasive Species Consortium—a regional hub for research to identify and manage invasive and non-native pest species along the Mississippi corridor. Housed within the LSU AgCenter, the consortium will unite scientists from land-grant institutions throughout the Mississippi River valley in coordinated efforts to combat the spread of invasive species, such as giant salvinia, feral hogs, apple snails, Mexican rice borers, and Asian carp—species that thrive in Louisiana’s climate and pose economic, environmental, and social challenges to ecosystems and agricultural operations in all the states connected by the river.

The AgCenter has an existing commitment to researching invasive species.

It already houses a Center of Research Excellence for the Study of Invasive Species. AgCenter leaders anticipate that the Invasive Species Consortium will expand the center’s influence to a regional level that extends from the Gulf Coast to the Great Lakes. In a press release published

in January, Senior Vice Chancellor of the LSU AgCenter and Dean of the LSU College of Agriculture Matt Lee said, “Invasive species cost Louisiana’s agricultural producers and the state’s economy tens of millions of dollars annually, with a national impact exceeding $120 billion

each year. This funding will allow us to coordinate detection, identification, research and best management practices to mitigate these threats and protect our region’s vital agricultural and natural resources.” lsuagcenter.com.

—James Fox-Smith

Amid a resurgence in the Baton Rouge drama community, 225 Theatre Collective has found a new home at the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge. Now, the collective will regularly hold performances and workshops at the Cary Saurage Community Arts Center on St. Ferdinand Street, providing it with a dedicated brick-and-mortar site that will make a difference for future programming.

“Moving 225 Theatre Collective into the Cary Saurage Community Arts Center is a huge step forward for us,” said Stephanie Calero, 225 Collective’s artistic director. “It gives our team a true creative home where we can grow our programming, support local artists, and welcome more of the community into the arts.”

Victoria Brown, the collective’s production designer, added that she, too, was excited about the step forward for the company.

“Moving into the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge has not only shown us the benefits of teaming up with other artists, but it also has demonstrated how kind and supportive the arts community in Baton Rouge is,” she said. “By uplifting, collaborating, and encouraging each other, artists can create more and give back to the community. We are so happy to be able to use the Arts Council building as a safe space to continue our mission of diversity and creativity.”

Calero added that partnering with the Arts Council of Greater Baton Rouge as one of its resident theatre companies allows the collective to offer consistent programming in a space that was specifically designed to bring people together through creativity. “We’re excited to build an even stronger and more accessible arts scene in Baton Rouge,” she said. “We are beyond grateful!” Learn more about the 225 Theatre Collective at 225theatrecollective.com.

—Jacqueline DeRobertis-Braun

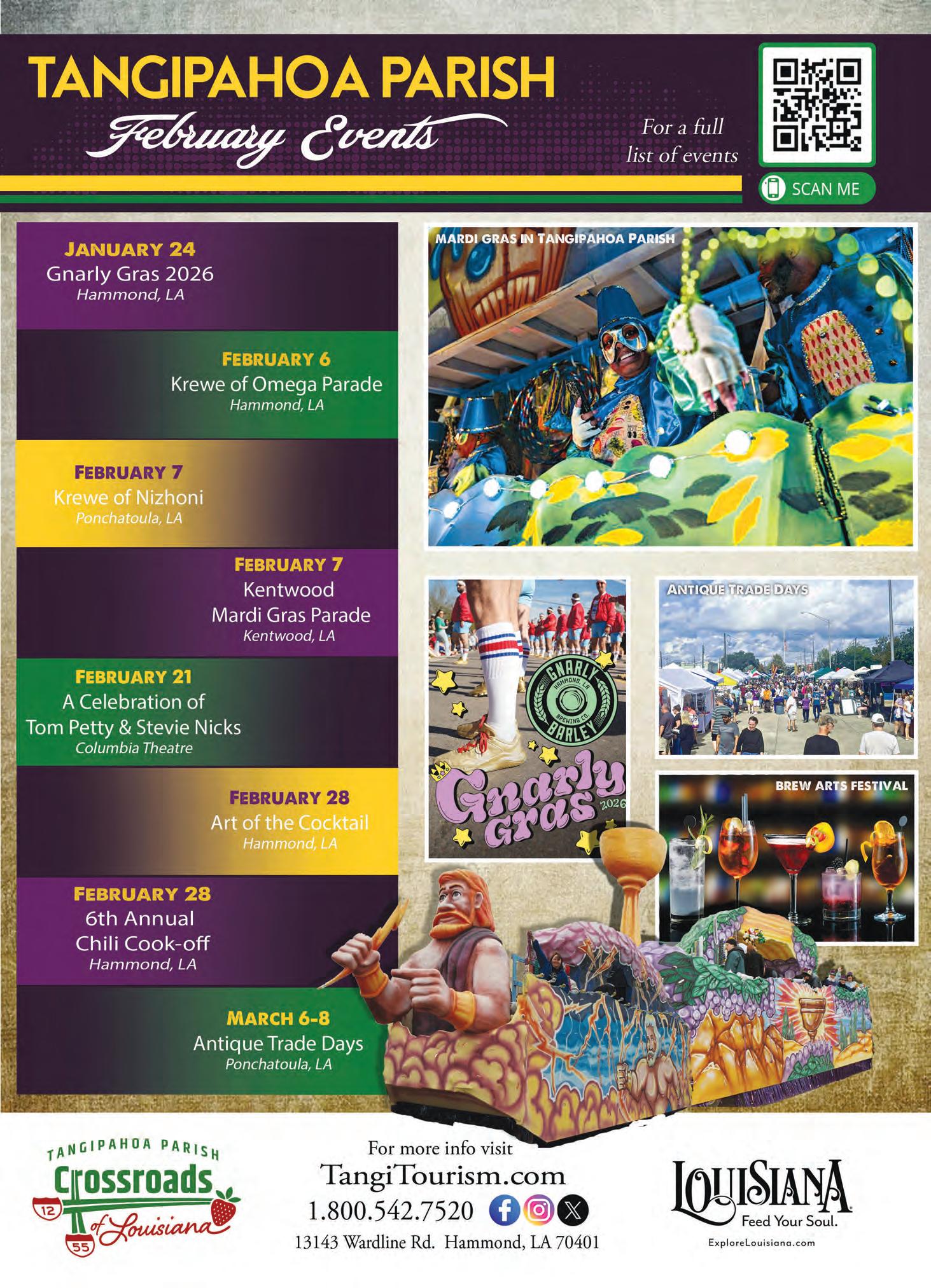

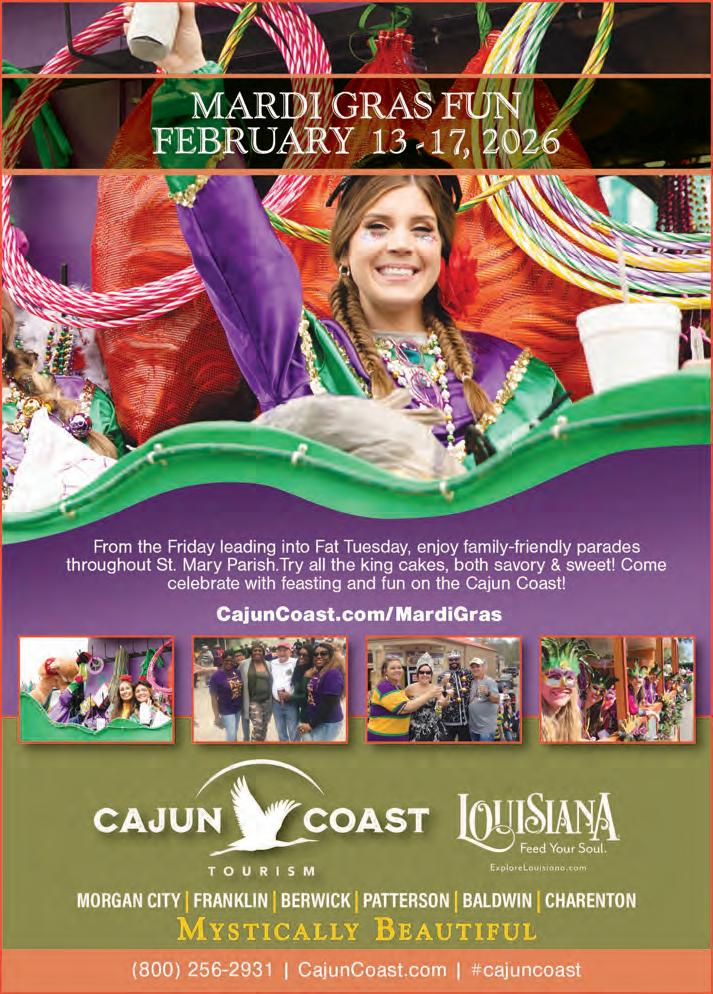

WHETHER YOU SHOW UP FOR PARADES, COURIRS, OR THE CELEBRATIONS IN-BETWEEN, WE'VE GOT YOUR CARNIVAL SEASON COVERED • FEBRUARY 2026

THROW ME SOME THIN'

Catch up on all the Carnival revelry across the South leading up to Fat Tuesday. Find non-Mardi Gras events happening throughout February beginning on page 24.

February 6

Krewe of Oceanus: Founded in 2020 by the residents of Southern Hills, this aquatic-themed Shreveport parade begins at Mall St. Vincent. 7 pm. For details see the Krewe of Oceanus Arklatex Facebook page.

February 7

Krewe of Janus Children's Parade: A cute parade with even cuter riders at Pecanland Mall's Center Court. 10 am. kreweofjanus.com.

African American History Parade: This thirty-seventh annual parade celebrating the many contributions of Black Americans starts at the Shreveport Municipal Auditorium. 11 am. sbfunguide.com.

Krewe of Paws Parade: Furry friends of all shapes and sizes will be in West Monroe dressed in their Mardi Gras best, beginning on the 100 block of Commerce Street. Noon. pawsnela.org.

Krewe de Riviere Mardi Gras Parade: Enjoy a traditional New Orleans feel with floats, walking groups, riding groups, and plenty of goodies. Parade starts at 1118 Natchitoches Street and ends at the intersection of Louisville Avenue and Oliver Road. 3 pm. monroe-westmonroe.org.

Krewe of Centaur: The largest parade in the Ark-La-Tex area, Shreveport's “Fun Krewe” is known for its centurion celebration of the regional gambling industry. 3:30 pm starting at the corner of Lake Street and Clyde Fant Parkway, before traveling down the ShreveportBarksdale Highway. kreweofcentaur.org.

Krewe of Janus: Northeast Louisiana’s oldest parade joins the Twin Cities by parading through West Monroe and Monroe, mostly down Louisville Avenue. 6 pm. kreweofjanus.com.

February 8

Krewe of Barkus and Meoux : The crowd acts like animals for this Shreveport favorite. 2 pm. barkusandmeoux.com.

February 14

Krewe of Gemini: Shreveport and Bossier City's first parading krewe of modern times, this event is one of distinctly royal revelry. In downtown Shreveport at 3:30 pm. kreweofgemini.com.

February 15

Krewe of Highland: Lunch will be supplied at this eclectic Shreveport parade in the form of grilled hot dogs and packaged ramen noodles hurled off of floats. Rolls at 2 pm through the Highland neighborhood. kreweofhighland.org.

February 6

Krewe of Cork : New Orleans’s wine krewe will be sippin’ and steppin’ through the French Quarter. 3 pm. kreweofcork.com.

Krewe of Oshun: This krewe includes marching Baby Dolls, a band contest, peacocks, and the goddess of love—all making their way down St. Charles. 5:30 pm. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Cleopatra : The first all-female organization on the Uptown route will roll again. 6 pm. kreweofcleopatra.org.

February 7

Krewe of Pontchartrain: Famous for its history of celebrity Grand Marshals, this St. Charles Avenue parade is one of New Orleans’s longest-standing. 11:30 am. kofp.com.

Krewe of Choctaw : Starting their more than eighty-year history on mail wagons as floats, this krewe will march down St. Charles. 12:30 pm. kreweofchoctaw.com.

Knights of Nemesis: The krewe of St. Bernard Parish will make its annual, unforgettable appearance coming down Judge Perez Drive. 1 pm. knightsofnemesis.org.

Krewe of Freret: This krewe has a focus of preserving New Orleans Mardi Gras

tradition, and will march down St. Charles. 1 pm. kreweoffreret.org.

Magical Krewe of Mad Hatters: This recently-founded Metairie krewe aimed at capturing the imagination brings Alice in Wonderland to life with colorful lights, costumes, and dance troops on Veteran’s Boulevard. 5 pm. madhattersparade.com.

Knights of Sparta : This all-male krewe has been around since the fifties. 5:30 pm. knightsofsparta.com.

Krewe of Pygmalion: This parade founded by Carnival veterans in 1999 rolls down the St. Charles route, floats only, at 6:15 pm. kreweofpygmalion.org.

February 8

The Mystic Krewe of Femme Fatale: The first krewe founded by African American women for African American women, their signature throw is a designer lady's compact, symbolizing constant inward and outward reflection. 11 am down St. Charles. mkfemmefatale.org.

Krewe of Carrollton: Carrollton is the fourth-oldest parading krewe of the New Orleans Carnival season. They are known for throwing shrimp boots. Follows

Femme Fatale at 12:30 pm down St. Charles. kreweofcarrollton.org.

Krewe of King Arthur and Merlin: One of the largest New Orleans krewes, Arthur and Merlin’s signature throw is the King Arthur Grail—hand-made goblets that are bestowed upon the most esteemed parade-goers. Follows St. Charles at 1 pm. kreweofkingarthur.com.

Mystic Krewe of Barkus: This one has gone to the dogs—see them all, including the four-legged royalty. In the French Quarter, starting at 2 pm. kreweofbarkus.org.

February 11

Krewe of Druids: This secret society is known for its wit and tendency to ruffle feathers. One year it featured a float saying: “Seriously...The Parade Behind us is not Worth the Wait.” 6:15 pm down St. Charles. kreweofthedruids.org.

Krewe of ALLA : One of the oldest of the New Orleans krewes, ALLA has been marching in Uptown since the Great Depression. Step out to catch one of their signature genie lamp throws. 7 pm. kreweofalla.net.

February 12

Knights of Chaos: Parading on the traditional "Momus Thursday," Chaos picks up where Momus left off—in the grand tradition of satire. Uptown route at 4:30 pm. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Knights of Babylon: Traditional to the max, this Uptown krewe designs their floats exactly as they were drawn up over eighty years ago. The king’s identity is never revealed to the public. 5:30 pm. knightsofbabylon.org.

Krewe of Muses: Why shop for shoes when you can catch a pair? One of the most coveted throws of the season comes from this incredibly popular all-female parade. Uptown at 6 pm. kreweofmuses.org.

February 13

Krewe of Bosom Buddies: This French Quarter walking parade celebrates women of all walks of life, and throws out handdecorated bras along the way. 11:30 am. bosombuddiesnola.org.

Krewe of Hermes: Every year, the Hermes captain leads the Uptown procession in full regalia on a white horse, followed by innovative neon floats and 800 male riders. 5:30 pm. kreweofhermes.com.

Krewe d'Etat: Led by a dictator instead of a king, this secret society gets a kick

out of throwing blinking skulls at its audience. Pick up a copy of the D'Etat Gazette, a bulletin with pictures and descriptions of the floats. 6:30 pm down St. Charles. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Morpheus: Looking through the chaos and tomfoolery for an "old school" parade down St. Charles? This one's for you. 7 pm. kreweofmorpheus.com.

February 14

Krewe of NOMTOC: The Krewe of New Orleans Most Talked of Club was founded in 1969 by the Jugs Social Club. The all Black krewe tosses out ceramic medallion beads, jug banks, and signature Jug Man dolls. Starts in the Westbank at 10:45 am. nomtoc.com.

Krewe of Iris: One of the oldest and largest female Carnival organizations for women, Iris continues to follow old-school tradition, its 3,600 members donning white gloves and masks and throwing decorated sunglasses and king cake babies, as well as a bunch of Iristhemed items. 11 am down St. Charles. kreweofiris.org.

Krewe of Tucks: This one got its start at a pub, and has developed a fond reputation for its potty humor, including toilet paper throws draping St. Charles's live oaks. Watch out for the King's throne (a giant toilet). Noon. kreweoftucks.com.

Krewe of Endymion: If you’re heading to watch this New Orleans “Super-Krewe,” be sure to get out to your viewing spot on Canal early. The krewe hosts Samedi Gras, a block party that draws 30,000+ people to kick off the parade. Previous grand marshals include Kelly Clarkson, Carrie Underwood, Luke Bryan, Steven Tyler, Pitbull, Kiss, and Flo-Rida. 4 pm. endymion.org.

Krewe of Isis: As Jefferson Parish’s oldest-consecutively parading Carnival organization and largest all-female krewe, the Metairie Egyptian-themed parade features marching bands, dance teams, and spectacularly-attired maids. Starts at the Esplanade Mall at 6 pm. kreweofisis.org.

February 15

Krewe of Okeanos: Back in the '50s, Okeanos started as a small neighborhood parade, and evolved into the over 300-rider krewe it is today, traveling on the traditional Uptown/Downtown route. 11 am. kreweofokeanos.org.

Krewe of Mid-City : This one is famed for its foil-covered floats and childrenoriented themes. 11:45 am along the St. Charles Route. kreweofmid-city.com.

Krewe of Thoth: This parade's route is uniquely designed to reach extended healthcare facilities so that individuals unable to attend other parades can participate in the holiday as well. Noon on the Uptown route. thothkrewe.com.

Krewe of Bacchus: Revered as one of the most spectacular krewes in Carnival history, this parade is known for staging celebrities Bob Hope, Dick Clark, Will Ferrell, and Drew Brees as its namesake, Bacchus. The parade ends inside the Convention Center for a black-tie Rendezvous party of over 9,000 guests. 5:15 pm. kreweofbacchus.org.

Krewe of Athena : Jefferson Parish's newest all-female krewe, founded on Sisterhood, Service, Fellowship, and Fun, will be tossing out hand-decorated fedoras down Veteran's Memorial Boulevard. 6 pm. kreweofathena.org.

February 16

Krewe of Proteus: Founded in 1882, this St. Charles parade is the second-oldest krewe in Carnival history, and still uses the original chassis for their floats. Once known as the most miserly throw-ers, they now joust 60-inch red-and-white pearl bead necklaces, plastic tridents, and polystone medallions. 5:15 pm. kreweofproteus.com.

Krewe of Orpheus: This parade was established as a superkrewe immediately after its debut, which rolled out 700 riders. One of their most famous floats is the Dolly Trolley, the horse-drawn bus used in the opening of Hello, Dolly! with

Barbara Streisand. Rolls on the Uptown Route at 6 pm. kreweoforpheus.com.

Krewe of Centurions: The familyfriendly Centurions parade is comprised of over 300 riders, and rolls on the Metairie route. 6 pm. kreweofcenturions.com.

Krewe of Atlas: This Metairie Krewe was founded on the principle of equality for all. 7 pm down Veterans. kreweofatlas.org.

Krewe of Zulu: A parading krewe since 1909, Zulu was the first and for many years the only krewe representing New Orleans’s Black community. Its extraordinary costumes, float designs, and history distinguish it from other Mardi Gras parades. 8 am on St. Charles. kreweofzulu.com.

Krewe of Rex : Elaborately decorated, hand-painted floats, masked riders in historic costumes, and a rich and colorful history make Rex one of the cultural centerpieces of Mardi Gras. Rex was formed in 1872, making it the oldest continually-operating krewe. The identities of Rex’s king and queen remains secret until Lundi Gras. 10:30 am down St. Charles. rexorganization.com.

ELKS, Krewe of Orleanians: The world’s largest truck parade features over fifty individually designed truck floats and comprises 4,500 riders. Follows Rex at 11 am. neworleans.com.

Krewe of Argus: One of Jefferson Parish’s largest and most family friendly parades, Argus draws over a million revelers to Metairie. Past celebrity guests include Barbara Eden, Phyllis Diller, and Shirley Jones. Starts from 41st Street and Severn Avenue at 11 am. kreweofargus.com.

Krewe of Crescent City : Each truck in the Crescent City Truck Parade represents a different Carnival organization. This parade signals the official "beginning of the end" of Carnival. Follows

ELKS Orleanians at 11:30 am. crescentcitytruckparade.com.

ELKS, Krewe of Jeffersonians: Featuring more than ninety trucks and 4,000 riders, this krewe shares the Elk mascot with its sister krewe, the Krewe of Elks-Orleanians. 11:30 am on the Veterans Memorial Boulevard route. neworleans.com.

February 6

Krewe de Canailles: Celebrating inclusivity, creativity, and sustainability, this walking parade down Jefferson Street in Lafayette does allow for floats—if you drag them yourself. Tossing out

eco-friendly throws and joining together groups of sub-krewes, these carnival crusaders have found a way to party their way to a better Lafayette. This year's theme is Roadside Attractions. 7 pm. krewedecanailles.com.

February 6–7

La Rivière Mardi Gras: Hosted at the Riverview RV Resort in Krotz Springs, this two-day Mardi Gras festival begins on Friday evening at 6 pm with the children's wagon parade and chicken run. Saturday brings the family-friendly adult parade, which launches from the resort at 9 am, with chicken stops (men only) along the way until a boudin intermission at Nall Park, and ends with a bowl of gumbo and live music back at Riverview for the women's chicken run. $10 to watch, $20 to participate in the parade; $20 to participate in the chicken run, cash only. 9 am. (337) 351-4260.

February 7

Courir de Mardi Gras de L’anse: The men of Mermentau Cove are suiting up traditional courir-style and rambling around its backroads. Come for the run, stay for the fais-do-do and gumbo

afterwards at a home on Lafosse Road. Courir begins at 8 am, Fais Do Do at 4 pm. acadiatourism.org.

Lebeau Mardi Gras Festival: This St. Landry celebration starts out with an old-school courir with all the trappings, including a greased pig chase and zydeco tunes. Then the Lebeau Mardi Gras Parade steps out on horseback, ATVs, automobiles, wagons, and traditional floats. Festivities start at 8 am, parade departs at 1 pm and it all ends at a music fest at the Immaculate Conception Church from 4 pm–7 pm. cajuntravel.com. (337) 945-4238.

Lake Arthur Mardi Gras Run/ Parade: Bringing the extravagance of New Orleans Carnival, Lake Arthur's celebration kicks off with a courir coming from Lake Arthur Park at 9 am, with several chicken run stops along the way. Back at Arthur Avenue, at 3 pm the parade—floats and all—will embark on its own journey. jeffdavis.org.

Krewe Des Chiens: The least we can do for our dogs is to parade them, in all their grandeur, through the streets of Lafayette. Noon on West Vemilion Street. krewedeschiens.org.

Krewe of Carnivale en Rio: Known for its vibrant floats, dazzling lights, and the jubilant accompaniment of maracas, the Parada—which honors Brazil’s first emperor Dom Pedro I and his granddaughter Dona Isabel—has become Lafayette’s premier Mardi Gras event. 6:30 pm down Johnston and Vermilion. riolafayette.com.

February 8

Courir de Mardi Gras at Vermilionville: Vermilionville and the Basile Mardi Gras Association are hosting a traditional country Cajun Mardi Gras run in the historic village. Things kick off at 10 am with a discussion by historian Barry Jean Ancelet, followed by a demonstration on the traditional "Chanson de Mardi Gras" by Kevin Rees. Then, experience the traditional run through the village, ending with a chicken chase for the children. Afterwards, enjoy lunch at the onsite restaurant, sample king cakes, learn how to make a capuchon, and more. 10 am–4 pm. $12; $10 for seniors; $7 for students; and children younger than five are free. bayouvermiliondistrict.org.

February 12–17

Eunice Cajun Mardi Gras Festival: Every Carnival season, Eunice convenes downtown for five days of fais dodoing. Don't miss out on events like the accordion & fiddle contest, Cajun

dance lessons, a boucherie, a children's courir, a pet parade, and more. Expect to watch the end of Eunice's courir come through town at 3 pm Tuesday afternoon, then dance until the dang day is done. eunicemardigras.com.

February 13

Krewe of Allons Kick-Off Parade: Getting things started for the slate of events that makes up the Greater Southwest Louisiana Mardi Gras Association's celebration of Mardi Gras in Lafayette, this parade travels from the corner of Simcoe, Surry, and Jefferson through the Downtown area over to Johnston, turning on to College to land at Cajun Field. Rolls at 6:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

February 13–17

Le Festival de Mardi Gras à Lafayette: Head to Cajun Field in Lafayette for Carnival rides (see what we did there?) and games, live music from local favorites, and delicious food. Times vary. 800-346-1958. gomardigras.com.

February 14

Cankton Courir de Mardi Gras: Join in on a chicken run, trail ride, gumbo cook-off, live music, and more at Landon Pitre Memorial Park. Live music from 2:30 pm–5:30 pm, with a live DJ starting at 9 am. Costumes encouraged. 7 am–

6 pm. $5 to enter; $60 per gumbo team; $20 to participate in the chicken run/ trail ride. All proceeds benefit the Special Olympics of Louisiana. cajuntravel.com.

Eunice Lil' Mardi Gras: Watch 'lil costumed runners race after the courir's mascot—dreaming of a chicken-shaped trophy. The day begins at 9 am with the traditional run at the Eunice Recreation Complex, followed by the official chicken chasing competition at 1:15 and the children's parade through downtown Eunice at 3 pm. Ages 1–14. $10 per child to participate; $10 per vehicle to follow along the route. cajuntravel.com.

Church Point Children's Mardi Gras Run: A miniature version of one of Acadiana's most famous traditional Mardi Gras celebrations, open to children ages fourteen and younger. Begins at 10 am, and marches down Main Street at 1 pm. $10 to participate; no horses. saddletrampridersclub.org.

Lafayette Children's Parade: The city's tiniest krewes will head down Johnston, in all their majesty, at 12:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

Lafayette's Krewe of Bonaparte: A hallmark of Lafayette Mardi Gras since 1972, this krewe infuses excitement and youth into the city's annual traditions. See them roll down the Greater Southwest Louisiana Mardi Gras route, from Jefferson to Johnston, to the CajunDome, starting at 6:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

Oberlin Courir de Mardi Gras: Oberlin starts the Saturday before Fat Tuesday with their Children's Courir at 8 am, with gumbo served at The Crawfish Shack and live music performances to follow beginning at noon. The Oberlin Mardi Gras Marches begin at 6:30 pm and 7:30 pm. allenparish.com.

February 15

Courir de Mardi Gras Church Point: This run features costumed horseback riders, wagons, buggies, floats, and live music along with all your characteristic chicken chasing and greased pig capturing. 7 am–2 pm. $50 to participate, must be in costume. Main Street parade begins at 1 pm. saddletrampridersclub.com.

Grand Marais Mardi Gras Parade: Admire costumes from the artistic to the repulsive—all elaborate, plus floats and dance troops at this family-friendly afternoon Jeanerette parade, which begins at Grand Marais Park at 2 pm. iberiatravel.com.

Eunice Parade of Paws: It's a ruff world out there, but not on the Sunday before Mardi Gras. Come see the prettiest and most pampered pups parade through Downtown Eunice. 3 pm. eunicemardigras.com.

February 16

Lafayette's Monday Night Parade: In Lafayette, Lundi Gras is for the queens—Evangeline LXXXII and LXXXIII will reign over the city's most regal krewes, rolling down the Southwest Louisiana Mardi Gras route at 6 pm. gomardigras.com.

February 17

Courir de Mardi Gras de Grand Mamou: One of the most raucous and famous Cajun chicken runs on the prairies. Starts at 6:30 am, and travels throughout the country roads collecting goods for that end-of-the-day gumbo. Catch the parade at the end of the day in downtown Mamou around 3 pm (watch where you step, horses have been known to enter the bars). evangelineparishtourism.org.

Faquetaigue Courir de Mardi Gras: Designed to be appropriate for all ages, to be family friendly, and to emphasize culture, this run takes place on horseback, on foot, and via trailer, journeying throughout the Faquetaigue community. Begins at 8 am; full costumes with hats and masks are required. $25. faquetaigue.com.

Le Vieux Mardi Gras de Cajuns de Eunice: Eunice’s Courir de Mardi Gras features riders on horseback in masks, conspiring in chicken-chasing, revelry, general silliness, and an effort to make a community-wide gumbo. Costumeclad trailers follow behind—and all join together in downtown Eunice for a final fais do do at 3 pm. The day starts long before that, though, at 8 am at the Northwest Community Center. facebook.com/eunicemardigras.

Tee Mamou-Iota Mardi Gras Folklife Festival: Experience the handmade costumes and masks, the masterfully medieval capuchons, and the unbridled chaos of it all—the Folklife Festival also celebrates with live music, folk crafts, and local food booths on the prairie. 9 am–4 pm. acadiatourism.org.

Carnival D’Acadie: Run into the heart of the Cajun Prairie to celebrate Fat Tuesday, Rice City Style. Crowley’s Fat Tuesday festival includes carnival rides, live music, and a grand parade at 2 pm. Music starts at 10 am. acadiatourism.org.

King Gabriel's Parade: Lafayette's grandest of parades, honoring the King of Carnival and the hundreds of volunteers who make the vibrant showcase down Johnston possible. Rolls at 10 am. gomardigras.com.

Opelousas Mardi Gras Parade: Floats, beads, and reigning royalty make up this Opelousas parade, marching through downtown Opelousas starting at Le Vieux Village Heritage Park. Begins at 11 am.

Get there early to see the Mystic Krewe of Fur Babies' pre-parade, and stay late for a musical performance on the Square. cajuntravel.com.

Lafayette Mardi Gras Festival Parade: Emitting the spirit fueled by the carnival atmosphere at Cajun Field, this parade will run down Johnston at 1 pm. gomardigras.com.

Independent Parade: Anyone can participate in this parade, which closes out Mardi Gras day in Lafayette. Enjoy the show of "independent" floats rolling down Johnston, starting at 2:30 pm. gomardigras.com.

February 6

Krewe of Artemis: The first all-female krewe in Baton Rouge begins and ends at the corner of Government Street by the River Center. Revelers will be treated to themed throws, including the Krewe of Artemis’s signature High-Heeled Shoe. 7 pm. kreweofartemis.net.

February 7

Krewe of Diversion: The annual

Livingston boat parade benefiting St. Jude Children's Research Hospital floats starting at noon at Manny's. Free. livingstontourism.com.

Addis Fireman's Mardi Gras Parade: In the little town of Addis, the Volunteer Fire Department will sponsor its familyfriendly line of celebration for all. 1 pm. Visit the Addis Fireman's Mardi Gras Parade for details.

Krewe of Tickfaw River: Mardi Gras comes to the Tickfaw River, with boats decked out in ways unimaginable. Begins at Dendinger Road in Killian at 1 pm. livingstontourism.com.

Krewe Mystique de la Capitale: Baton Rouge's oldest parading Mardi Gras krewe continues its mission to uphold Carnival season in the Capital City. Family oriented, it starts at the River Center and winds around downtown. 2 pm. krewemystique.com.

Krewe of Ascension Mambo Parade: Prepare to be awed as the creative masterpieces that are Ascension Parish's Mardi Gras floats pass down Irma Boulevard to Burnside Ave. 2 pm. visitlasweetspot.com.

Krewe of Orion: A Carnival-themed tractor pull through downtown Baton Rouge, this year's parade, themed "Famous Hollywood Faces," begins and ends at the River Center. 6:30 pm. kreweoforion.com.

February 8

Mid City Gras: Baton Rouge’s freshest Mardi Gras parade returns to Mid City. The one-afternoon revel goes down North Blvd., ending at Baton Rouge Community College, and invites locals to “get nuts” with an annual squirrelly theme in this wildly unpretentious neighborhood strut. 1 pm. midcitygras.org.

February 13

Krewe of Southdowns: Catch this family-friendly flambeaux-inspired nighttime parade glittering and glaring along its usual route from Glasgow Middle School through the Southdowns neighborhood. This year's theme is "vacation." 7 pm. southdowns.org.

February 14

Baton Rouge Mardi Gras Festival: An incredible line-up from Henry Turner Jr.'s Listening Room in North Boulevard Town Square is the highlight of this family-friendly Mardi Gras celebration. This year’s lineup to date features blues, soul, R&B, reggae, gospel, jazz, pop/

rock, spoken word, and comedy. Packages with meal tickets range from $50–$100. The festival is free to the public, and will be held from 10 am–7 pm. visitbatonrouge.com. bontempstix.com.

Spanish Town Parade: Spanish Town’s annual parade of miscreants rolls from Spanish Town Road and Fifth Street, to Lafayette Street and Main. The krewes dole out dozens of infamously irreverent floats, with marching bands, dance troupes, and waves of pink throws. Come early. This year’s theme is "Pink, Proud, and Provocative.” Noon. mardigrasspanishtown.com.

February 15

Krewe of Good Friends of the Oaks Parade: Residents of the Port Allen community, “The Oaks,” established this krewe in 1985, and it has been rolling right along ever since. 1 pm. westbatonrouge.net.

Zachary Mardi Gras Parade: Zachary's inaugural Mardi Gras parade is themed "Celebrating Everyday Heroes," and will feature the usual Mardi Gras magic— floats, marching bands, dance teams, car clubs, organizations, and local heroes. Begins at Church Street Park, ends at Ridgeway. 2 pm. zmardigras.com.

Krewe of Comogo Night Parade: See Plaquemine like you never have before

when Comogo rolls, sure to dazzle. 7 pm, starting at St. John the Evangelist Church and heading down Belleview Drive. kreweofcomogo.com.

February 16

Krewe of Shenandoah Parade: Powered by floats and enthusiastic local support, this third annual Baton Rouge parade rolls through the Shenandoah neighborhood beginning at 6:30 pm near Woodlawn Middle School, with the theme "Boogie on the Bayou." kreweofshenandoah.com.

February 17

Community Center of Pointe Coupée Parade: Every Carnival season the population of New Roads multiplies tenfold as parade-goers searching for a more laid-back time flock to the “Little Carnival Capital.” Rolls at 10 am through downtown New Roads. Visit the New Roads Mardi Gras Facebook page for details.

New Roads Lions Club Parade: This bead-heavy annual parade follows right behind the Community Center of Pointe Coupée Parade. 1 pm. Visit the New

Roads Mardi Gras Facebook page for details.

February 6

Krewe of Omega : See the regal King Brandon Phares and Queen Renee Donewar when they roll through the streets of downtown Hammond as monarchs of the Omega parade. 6:30 pm. kreweofomega.org.

Krewe of Eve: It began with six women, and now has close to five hundred members. With beautifully decorated Blaine Kern floats, this parade begins at the intersection of Ashbury Drive and Highway 190 in Mandeville and ends on the West Causeway Approach at its intersection with North Causeway Boulevard. 7 pm. kreweofeve.com.

February 7

Krewe of Tchefuncte: Cruising down Madisonville's Tchefuncte River, this boat parade celebrates maritime life on the historic river. Noon. kreweoftchefuncte.org.

Krewe of Push Mow : A group of

artists in Abita Springs decided it would be a hoot if they decorated lawn mowers for a parade (spoiler alert: it is). 12:30 pm starting at Abita Springs Recreation District 11. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Krewe of Olympia : The oldest parade in St. Tammany, King Zeus’s identity is kept secret until the parade, which starts on Columbia Street. 6 pm. kreweofolympia.net.

February 8

Krewe of Dionysus: Named for the Greek god of wine, Slidell's first allmale krewe will set out at 1 pm at the intersection of Spartan Drive and Highway 11. kreweofdionysus.com.

February 13

Krewe of Selene: Slidell's only allfemale krewe tosses out one-of-a-kind hand-decorated purses. Rolls at 6:30 pm starting at Spartan Drive and Highway 11. kreweofselene.net.

February 14

Krewe of Bush: The Northshore community of Bush hosts its own family-friendly parade featuring trucks, boats, horses, and more. 9 am. mardigrasneworleans.com.

February 16

CMST Kids Krewe Parade: Celebrate

Carnival with the joy and excitement of a child at the Children's Museum of St. Tammany Kids Krewe Parade on Lundi Gras. Secure your spot by registering your wagon and join the festive procession. 11 am. cmstkids.org.

February 17

Covington Lions Club: Keep an eye out for The Ride of the Brotherhood on motorcycles, along with the Shriners in buggies and Saints Super Fans. The parade begins at North Jefferson Ave. and North Columbia St. at 9:15 am. visitthenorthshore.com.

Krewe of Kidz Wagon Parade: For its fifth year, more than 100 little walkers toting their wagons will roll through Old Towne at 10 am. The parade begins in the parking lot behind KY's Restaurant. visitthenorthshore.com.

Krewe of Bogue Falaya Mardi Gras Parade: This vibrant parade rolls after the Covington Lions Club parade, featuring traditional Mardi Gras floats, marching bands, walking groups, horses, and costume contests. visitthenorthshore.com.

Mystic Krewe of Covington: Founded in 1951, the Mystic Krewe of Covington— the city's oldest—will roll right after the Krewe of Bogue Falaya parade. visitthenorthshore.com.

Krewe of Chahta : Named for Chahta-

Ima High School, this Lacombe parade will roll at 1 pm, featuring floats, marching units, cars, and horse groups. visitthenorthshore.com.

Krewe of Folsom: An eclectic parade invites all to join in on the fun with the citizens of Folsom. 2 pm. Begins at Magnolia Park on the corner of Olive Street and Garfield Street. mardigrasneworleans.com.

Carnival in Covington: Mardi Gras After Party : Following the Krewe of Bogue Falaya Mardi Gras Parade, the City of Covington hosts a lively party at the Covington Trailhead from noon–4 pm, featuring live music, food trucks, and more. visitthenorthshore.com.

February 6

Krewe of Hercules Parade: A favorite along the traditional West Side Route in Houma, Hercules has been rolling for over forty years now. 6 pm. Details at the Krewe of Hercules Facebook Page.

February 7

Krewe of Tee Caillou Parade: A favorite parade in the small town of Chauvin, where the throws are as good as the fishing. Noon. explorehouma.com.

Krewe of Versailles Parade: Lafourche Parish's first parade of the season

rolls right out of Larose. Noon. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Aquarius Parade: This massive, all-women's Houma parade rolls from Southland mall and ends at Town Hall Shopping Center. 6:30 pm. Details at the Krewe of Aquarius Facebook Page.

February 8

Krewe of Shaka Parade: Noted for its remarkable contributions to the Thibodaux community, this parade's King and Queen are annually presented with the Key to Thibodaux. Expect floats, local bands, and dance groups. 12:30 pm in downtown Thibodaux. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Hyacinthians Parade: The Ladies Carnival Club, Inc. is the largest carnival club in Terrebonne Parish. Signature throws are sunglasses and top hats. Kicking off at 12:30 pm down Houma’s West Side Route. hyacinthians.org.

Krewe of Titans Parade: Following the Hyacinthians, the Titans will roll right through Houma. 1 pm. explorehouma.com.

Krewe des Couyons Parade: Celebrate the "Heroes of Mardi Gras" on the route of this parade in Golden Meadow. 1 pm. More details at the Lafourche Concert and Events Club Facebook Page.

Krewe of Ambrosia Parade: This parade has floated through Thibodaux for more than forty years now with themed floats shoveling out enviable beads. 2 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

February 13

Krewe of Aphrodite Parade: Rolling from Southland mall, and landing at Town Hall Shopping Center, this Houma parade is a rousing way to spend an evening this Mardi Gras season. 6 pm. explorehouma.com.

Krewe of Athena Parade: Golden Meadow ladies take the night again in this evening parade. 7 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Adonis Parade: St. Mary Parish's first parade of the season is this historic night parade in downtown Morgan City, and has been drawing delight for almost forty-five years now. 7 pm. cajuncoast.com.

February 14

Krewe of Apollo Parade: Launching off of the streets of Lockport for almost sixty years, this men's and women's krewe is known for a raucous good time. Noon. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Lul Parade: Rolling at noon, Luling's parade will begin on LA 52 at Angus Drive to LA 18 to Sugarhouse Road to Angus Drive. cajuncoast.com.

Le Krewe du Bon Temps Parade: Larose's Krewe of Good Times brings plenty of them the weekend before the big day. 6:30 pm. Details at Le Krewe du Bon Temps Facebook Page.

February 15

Krewe of Terreanians Parade: One of Houma's oldest parading carnival clubs, Terreanians rolls through Houma at 12:30 pm. explorehouma.com.

Krewe of Cleophas Parade: Thibodaux’s oldest parade will march again, featuring over fifty floats, bands, stilt walkers, dance teams, and more. 12:30 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Des Allemands Parade: Head to Des Allemands at 1 pm for bon temps, with local school bands, dance teams, fire trucks, boats, and—of course— creatively themed floats and royalty. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Montegut Parade: This children's parade rolls at 2 pm in downtown Houma. explorehouma.com.

Krewe of Galatea Parade: St. Mary Parish's first female krewe has been rolling the streets of Morgan City since 1969. Begins on 2nd Street, through downtown. 2 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Chronos Parade: One of Thibodaux’s most celebrated parades of the season, Chronos believes in the slogan

“Every Man a King,” and “Every Woman a Queen.” 2 pm. kreweofchronos.com.

Krewe of Nike Parade: The children's Krewe of Nike will roll immediately after Galatea in Morgan City. 2:30 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Hannibal Parade: Another reputable Morgan City krewe to close out Friday's parades at 2:45 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Nereids Parade: This Golden Meadow women's krewe is known for its fun themes and parade of floats, entertainment, and throws. 6 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

February 16

Krewe du Gheens Celebration and Parade: Kicking off the parade schedule on Mardi Gras day in Louisiana's Cajun Bayou region, the Krewe of Gheens will roll at 11 am. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Cleopatra Parade: The six hundred plus ladies of Cleopatra steal the night for the only Lundi Gras parade in Terrebonne Parish. 6 pm down Houma’s West Side Route. houmatravel.com.

Krewe of Hera Parade: One of the Cajun

Coast’s newer parades, this Morgan City procession is all excess and excitement. See them heading down Second Street to Onstead to the auditorium on Myrtle. 7 pm. cajuncoast.com.

February 17

Krewe of Neptune Parade: As it's done since 2019, Neptune rolls in Golden Meadow on the big day. Noon. lacajunbayou.com.

Krewe of Houmas Parade: This historically-rich krewe was the first to ever parade down Houma’s West Side Route. On each float, a family is honored with at least one fatherson duo or pair of brothers. 1 pm. kreweofhoumas.wildapricot.org.

Krewe of Ghana Parade: Fun floats and dancers will make their way through downtown Thibodaux on Mardi Gras Day. 1 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Siracusaville Parade: This small town parade lines up on Siracusa Road before ending at the Siracusaville Recreation Center. 1 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Choupic Parade: Even Chackbay turns out for this afternoon Fat Tuesday parade. 1 pm. lacajunbayou.com.

Franklin Mardi Gras Parade: Bringing together all the krewes of the little Cajun town of Franklin, this Fat Tuesday parade can be traced back to 1934. It runs from Franklin Senior High School, along Main Street, then turns back around onto Willow and Third. 1 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe of Kajuns Parade: Parading behind the Krewe of Houmas, this canaille club is a must-see. 2 pm. explorehouma.com.

Krewe of Hephaestus Mardi Gras Parade: The oldest krewe in St. Mary Parish dates back to 1914, rolling on Mardi Gras day from Sixth and Sycamore to the Morgan City Municipal Auditorium. 2 pm. cajuncoast.com.

Krewe de Bonne Terre: This Montegut parade rolls at 4:30 pm. mardigraskrewe.com.

February 6

Pineville Night of Lights Parade: This parade glows and shimmers through the streets of Pineville, beginning on Main Street. 7 pm. pineville.net.

February 13

Classic Cars & College Cheerleaders Parade: The name of this parade really says it all, and will cheer and roll through the streets of Downtown Alexandria. 5 pm. alexmardigras.net.

February 14

Children's Parade: Alexandria’s kiddo parade brings loads of festive cuteness to the streets of Downtown. 10 am. alexmardigras.net.

Alexandria Zoo Mardi Gras Party : They're all asking for you at the Alexandria Zoo's vibrant Mardi Gras celebration. Join the festivities in your best purple, green, and gold attire, indulge in king cake, and groove to some wild tunes with all the animals. thealexandriazoo.com.

February 15

Krewes Parade: Alexandria’s Krewes Parade is one of CenLA’s biggest. Rolls at 2 pm from Texas Avenue to the Mall. alexmardigras.net.

February 13

Merchants Parade: Local business and civic leaders march the streets of downtown-midtown Lake Charles during this glowing, community-oriented night parade. Begins at the Lake Charles Event Center, travels along West Pine to Ryan, and concludes at Sale Road. 7 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

February 14

World Famous Cajun Extravaganza and Gumbo Cook-off : Amateur and

professional teams compete for the chicken & sausage, seafood, and wild game gumbos. Tasting begins at 11 am at the Civic Center, with live music and DJs keeping the energy up throughout the day. $10 presale; $15 day-of, kids ten and younger free. visitlakecharles.org.

Mystical Krewe of Barkus Parade: Furry and fabulous, costumed pets parade down Gill Street in Lake Charles for one of the most highly-attended parades of the season. 1 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Krewe of Omega Parade: An old and revered krewe, Omega celebrates the African American community of the southwest region. Begins at 2 pm on the north side of the Event Center and loops around to end in the same place. visitlakecharles.org.

DeRidder Parade: Returning for its second year, DeRidder Mardi Gras kicks off on Mardi Gras Saturday with a Gumbo Cook-Off, children's chicken run, costume contest, crawfish races, a king cake contest, a children's shoebox float parade, a line dancing contest, and more. It all leads up to the parade, which rolls at 4 pm from the Beauregard Parish Fairgrounds. Details on the DeRidder Mardi Gras Events Facebook Page.

February 15

SWLA Mardi Gras Children's Day Parade: Carnival fun on wheels for the little ones. Begins downtown on Ryan Street at 3:30 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

February 16

Mardi Gras Royal Gala : Experience one of the most inclusive and accessible Mardi Gras balls in the region, with all the glitz and the glamour. Be part of the magical, lavish promenade of krewe royalty, in all their museum-quality costumes, sure to dazzle. $10; free for children younger than ten. 7 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

February 17

Iowa Chicken Run: Even if you don't catch a chicken, you still can have gumbo after the courir departs from the Iowa Knights of Columbus Hall at 8 am, with performances at area homes—given in exchange for gumbo ingredients. Parade ends back at the KC Hall, where the pot is waiting. Live music will be performed by Rusty Metoyer & the Zydeco Crush. $15 for adults and $10 for children twelve and under. visitlakecharles.org.

Second Line Stroll: Watch groups strut down Ryan Street to the tunes of Mardi Gras music in this walking parade. 1 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Jeeps on Parade: The name says it all about this Jeep-centric Lake Charles Mardi Gras parade down Ryan Street. 2 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Motor Gras Parade: Right behind

the Jeep-snobs, hot rods classics and motorcycles ride down Ryan. 3 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

Mardi Gras Southwest Krewe of Krewes Parade: Over a hundred floats roll through downtown Lake Charles starting at 5 pm. visitlakecharles.org.

February 6

Jester's Ball: The City of Vicksburg sponsors this all-out affair, complete with flowing drinks, moon pies, food, and music. 7 pm. $40. vicksburgconventioncenter.com.

February 13

Krewe of Phoenix : Natchez has a Mardi Gras parade of their own up there, too— the Krewe of Phoenix, and they go pretty big. Lit-up floats, live bands, and more free fun will abound starting at 6:30 pm. kreweofphoenixnatchez.com.

February 14

Vicksburg Downtown Mardi Gras Parade: Local churches, businesses, drill teams and more strut through downtown Vicksburg during this community parade. 4 pm. vicksburgconventioncenter.com.

Carnaval de Mardi Gras Gumbo Cook–Off : Spice up your Mardi Gras

celebrations at the Carnaval de Mardi Gras Gumbo Cook-off at the Southern Heritage Cultural Center Auditorium 5 pm–7 pm for an evening of delectable gumbo and live music. $10; $5 for children, and includes a complimentary gumbo bowl. (601)-636-5010.

February 15

Mardi Gras Pet Parade: This rollicking parade asks proud pet parents to "strut your stuff" with a costumed furry friend in tow, held on the Natchez Bluff. Treats, music, and prizes abound at this fest for furry friends. 2 pm. Learn more at the Natchez's Own Mardi Gras Pet Parade Facebook event page.

FEB 1st - FEB 8th

THEATRE

"THE LION IN WINTER"

Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi

Eleanor of Aquitaine takes center stage in The Lion in Winter, to be performed at Bay Saint Louis Little Theatre. In this riveting account of the Plantagenet family, the queen has been imprisoned since raising an army against her husband, King Henry II. The play follows the royal family drama as it unfolds over Christmas of 1183. 8 pm; matinees on February 1 and 8 at 2 pm. $28; $20 for seniors, first responders, military, and students; $12 for children twelve and younger. bontempstix.com.1

FEB 3rd

CHITCHATS

LSU OLLI SPRING COFFEE TALK

Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Come grab a cup of coffee at St. Francisville Baptist Church, part of LSU OLLI's spring get-together. Don't miss featured guests Peter and Debbie Alongia, who will discuss their experiences along the Camino de Santiago. There will also be a preview of the new OLLI Spring Classes offered. Free, for ages fifty and older. ce.lsu.edu/oll i. 1

FEB 4th

FILM

LIVE MOVIE CONCERT: "RIGHT IN THE EYE"

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

At the Manship Theatre, experience a live music and cinematic event featuring the productions of Georges Méliès.

Created by Jean-François Alcoléa and featuring a multi-layered score performed by three musicians using a range of instruments, the multimedia production showcases twelve films to blend live performance with powerful visuals, bringing early cinema to life. 7:30 pm. $35. manshiptheatre.org. 1

VERSES

POETRY OUT LOUD

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

A national high school poetry recitation competition from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Poetry Foundation, Poetry Out Loud returns to Baton Rouge, with its regional competition taking place at the Cary Saurage Community Arts Center this February. Students across a ten-parish

region in the greater Baton Rouge area are invited to participate. Learn more at artsbr.org/poetry-out-loud. 1

GOOD EATS

BANKFIRST CHILI COOK OFF Laurel, Mississippi

Come warm up this February at the BankFirst Chili Cook Off, featuring teams across the region all competing for best traditional or homestyle chili. The top team takes home the coveted giant chili pepper. 11 am–3 pm. $15 for all-you-can-eat samples from participating teams; $30 for a handmade pottery bowl, along with entry. business.visitjones.com. 1

FEB 7th

SOCIAL DANCE

SATURDAY NIGHT BALLROOM'S MARDI GRAS MADNESS DANCE PARTY

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Saturday Night Ballroom presents its "Mardi Gras Madness" dance party at the American Legion Hall on Wooddale Blvd. in Baton Rouge. Dance the night away to celebrate Carnival season with a mix of Latin, ballroom, and swing styles. A cash bar will be available, along with food trays and snacks. Don your best Mardi Gras colors—dressy casual or whatever you feel comfortable wearing. 7 pm–10 pm. $15. Find the event on Facebook. 1

FEB 8th

CONCERT

SALLY BABY'S SILVER DOLLARS

New Orleans, Louisiana

Don't miss this all-local New Orleans five-piece at the Marigny Opera House—performing a sonic fusion of 50s/60s NOLA RnB, Jazz, & Calypso. Sally Baby's Silver Dollars brings the brass in this concert that features the soulful sounds of jam sessions to block parties. Doors open at 7:30 pm; performances at 8 pm. $25 suggested donation; $15 for students, seniors, etc. marignyoperahouse.org. 1

FEB 11th - FEB 12th

MARDI GRAS MUSIC

IT'S CARNIVAL TIME: A CONCERT IN THE COSMOS

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

It's time to let the good times roll at the Irene W. Pennington Planetarium. Join the Baton Rouge Symphony

Orchestra for a musical and visual concert experience celebrating the state's Carnival culture. Costumes encouraged, and wine and small bites will be available. 7:30 pm both nights. $40–$60. brso.org. 1

FEB 20th

CELEBRATIONS

HENRY TURNER JR.’S LISTENING ROOM ANNIVERSARY

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Celebrate twelve years of Henry Turner Jr.’s Listening Room—so-called "the last blues live music juke joint" in the capital area—with performances by Henry Turner Jr. & the Listening Room AllStars and screenings of Henry Turner Jr. The Architect of Celebration and Minutes into the Life of Henry Turner Jr. 7 pm–midnight. $25 in advance, $30 at the door. (225) 802-9681. 1

FEB 21st

SOUND ON "ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE"

Natchez, Mississippi

Bring a plus one to this romantic evening of operatic arias, musical theater songs, and highlights from the “Great American Songbook.” Featuring the Robert Grayson Studio Singers from LSU, the night will include original paintings, sculptures by local artists, and regional, national, and international travel packages, along with a silent auction, cash bar, and buffet. Hosted at the David O’Connor Family Life Center on Main Street in Natchez. 7 pm. $75. natchezfestivalofmusic.com. 1

FEB 26th - FEB 28th

BOOKWORMS

NATCHEZ LITERARY AND CINEMA CELEBRATION

Natchez, Mississippi

Back for another year celebrating Southern authors and filmmakers, this year's Natchez Literary and Cinema Celebration will be held at Natchez Convention Center. Themed, “Stories of American Freedom,” the festival will feature lectures and panels on various topics ranging from different wars across the decades to suffragists, code talkers, the Civil Rights movement, and many other historical subjects. Learn more and find the full schedule at colin.edu/community. 1

GAMERS

RETRO CON

Morgan City, Louisiana

Head to the Morgan City Municipal Auditorium for Retro Con, a video game convention that celebrates everything across the gaming spectrum and beyond. Saturday from 10 am–6 pm; Sunday from 11 am–5 pm. $22 for Saturday; $16 for Sunday; $33 for a weekend pass. louisianaretroconvention.com. 1

DIY-ERS

ST. TAMMANY HOME AND REMODELING SHOW

Mandeville, Louisiana

The Northshore's only home and garden show returns to the Castine Center in Mandeville. Teaming up with Certified Louisiana Food Fest, the show will showcase the best products and services for everything in your home, from kitchens, bathrooms, remodeling, siding, and more. 10 am–5 pm both days. For ticketing details see jaaspro.com. 1

FEB 28th

FESTIVALS

225 FEST

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Head to Galvez & Rhorer Plaza in downtown Baton Rouge for the biggest celebration of culture in the Capital region. Enjoy an afternoon of delicious bites from local vendors and food trucks, live music, art, and more. Free. Noon–6 pm. 225fest.com. 1

FEB 28th

ALL A-TWITTER

"THE ART OF BIRDS"

Saint Francisville, Louisiana

Wander over to Magnolia Village in the heart of Saint Francisville to experience The Art of Bird s. The day is dedicated to original art about our feathered friends, including paintings, drawings, photography, and more, located in three galleries in the historic 3V Tourist Court. Noon. Free. For details, contact birdmancoffeeshop@gmail.com. 1

For more events visit countryroadsmag.com/eventsand-festivals.

Growing St. Francisville Beautiful—one hanging basket, one planter box, one shade tree at a time

“Julie and I have ended up being the faces of St. Francisville Beautiful,” hremarked Leigh Anne Jones, then added with a grin, “although what most people see of us is our backsides.” The sight of Jones and her friend and fellow Historic District resident, Julie Brashier, on hands and knees tending the planters, flowerbeds, and hanging baskets dotting downtown St. Francisville, has become as familiar as the Victorian façades that line its streets. Founded by former mayor Bobee Leake and a handful of green thumbs in 2021, St. Francisville Beautiful is dedicated to bringing seasonal and permanent ornamental plantings to the town’s streetscapes. Today the organization cares for eight flowerbeds, thirty-five hanging baskets, and multiple large planters throughout the Historic District, and is adding elms and live oaks along major thoroughfares to expand the green canopy. On any given day Jones and Brashier might be spotted, up to the wrists in a planter box or garden bed tending to petunias, dianthus, pansies, alyssum, foxgloves, and other annuals selected in spring and fall for year-round color. In permanent beds like one in Fountain Park, Jones and Brashier prefer perennials like day lilies and split leaf philodendron, with im-

patiens and zinnias to fill in during summer months. Their vision: a St. Francisville “supergarden,” anchored by public plantings to beautify streetscapes year-round and inspire residents to extend the effort in their own gardens. It seems to be working. “People stop and say how much they enjoy the beds,” noted Jones. “They come to see what’s been planted, and what they can put in their own yard.” But as any gardener will tell you, a garden doesn’t grow itself. A townsized supergarden needs time, talent, and treasure to flourish. To that end, St. Francisville Beautiful, a 501c3 non-profit, invites members and volunteers to support the project by purchasing a membership, sponsoring a planter box or hanging basket, or by volunteering to plant, water, and weed. The organization is also looking for volunteers to help with its two major annual fundraisers. On Mother’s Day weekend (May 9) St. Francisville Beautiful will join forces with the Feliciana Master Gardeners to host the St. Francisville Spring Garden Stroll. Or during December’s Christmas in the Country, lend a hand when St. Francisville Beautiful presents Saturday evening’s blockbuster Christmas Spirits Stroll.

For tickets, details, and contact info, visit stfrancisvillebeautiful.com.

DUSTIN DALE GASPARD ON ANCESTRY, LANGUAGE, AND SINGING CAJUN FRENCH FOR AMERICA

Story by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot

On October 6, 2025, the hmore than 5 million hviewers tuned into NBC’s reality singing competition, The Voice, watched Michael Bublé get a frisson at the sound of Dustin Dale Gaspard’s harmonica. Reba nodded her head as he shifted into the first verse of Sam Cooke’s classic soul ballad, “Bring It on Home To Me.” Niall Horan and Snoop Dog couldn’t help but sing along, their growing excitement at the voice behind them palpable. None of them had even seen Gaspard’s face yet.

The song is one that the thirty-threeyear-old musician from Cow Island, Louisiana has sung at most every show he’s played since he began his career as an itinerant singer-songwriter, performing for mostly small crowds and at festivals across North America with the occasional jaunt to Europe—mostly living in his car. “[‘Bring It On Home To Me’ is] overdone,” he said in mid-December in an interview conducted over fried okra and fries at Mickey’s Drive Inn in Kaplan.

“Everybody plays it. But it is because it is a true song. It has real heart and soul.”

The song was also his PawPaw’s favorite, and the very last thing Gaspard sang to him before he passed away.

The previous October, when Gaspard had first gotten a response to his application for The Voice, inviting him to move into the interview process, he stepped outside beneath the night sky. And he prayed to his grandparents, his greatest inspirations. “I said, ‘Hey, if this is a real thing you want to happen for me, I’m ready. I’m gonna find a way.’”

It wasn’t about fame, or about winning. Gaspard’s only goal, only hope, was to have the opportunity to stand on a national stage and sing, in his own style, the language of his ancestors from Vermilion Parish. “I just wanted to get on stage and sing in Cajun French and go home, then look at the stars and tell my grandparents, ‘Thank you so much for sending me on that journey.’”

Seamless as it sounded, the shift to French in such a well-known song was

a surprise to the celebrity coaches of The Voice. You could see the moment of confusion on their faces as Gaspard crooned, “J’sais que j’ai ri / Quand t’as partie.” Horan turned to Bublé (a Canadian) and asked, “French?” It wasn’t French like anyone had ever heard, though. The translation and arrangement of Cooke’s second verse had been a labor of love, completed with help from Cajun/Creole language experts Drake LeBlanc and Barry Jean Ancelet.

Behind their backs, Gaspard felt as though the whole world had stopped. “All went silent,” he said. “And I remember looking at the big lights above the coaches’ chairs and seeing almost like a big star just shining back at me.” He closed his eyes and thought, “There it is. This is the moment I’ve been waiting on forever. I had this dream to do all these things, to explore my heritage and legacy, to travel and perform, to get on national television and sing in the Cajun language, and it is happening.”

After completing the French verse, Gaspard almost stopped singing and walked off the stage. “That was it, I had done it,” he said. But when he opened his eyes, all four of the coaches’ chairs had turned to face him, signaling that they wanted him on their team for the competition. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh God, no, this wasn’t supposed to happen,’” said Gaspard. Holding back tears, he finished the song in “complete disbelief.”

When Horan told him, “There’s nothing better than hearing a proper, unique, full-of-character voice … that was absolutely incredible, the bit of French, you could sing ‘Baa, Baa, Black Sheep’ and it would sound good,” Gaspard only responded with, “This is a weird dream.”

When Gaspard imagines how his grandparents might have reacted to his historic performance on The Voice, he can hear his grandfather’s voice saying, “Oh, that’s my boy, I knew, when you started singing in French!”

“When I hear people from home tell me that it resonated for them, I hear him saying it,” said Gaspard.

The musician attributes much of his current lifestyle, ever-transient, to a childhood going back and forth between his divorced parents’ homes, where he spent most of his time with his grandparents on each side. Days spent with his maternal grandfather, who ran the 26,000acre Paul J. Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary southwest of Vermilion Bay, were days of adventure. “With him, there was this exploratory appreciation for the wonders of the water and the stars and nature,” said Gaspard. “And also, an understanding that this is the land that raised my people, it was the foundation of who we are.”

His paternal grandmother, by contrast, rarely left her little brick home in Cow Island. “She was a very superstitious Cajun woman, a traiteur,” said Gaspard. “And that kind of lent itself to this deep, meditative mysticism. She told her stories within this world, and I came to recognize the tiny universe in which she existed. I feel like she made me think a lot about internal emotions that you deal with. Like the way she lived was this giant metaphor.”

When he imagines his grandmother’s reaction to his performance, he doesn’t think she’d say very much. She almost never left Vermilion Parish except, in her final years, to occasionally attend her grandson’s gigs until two in the morning. “She believed in me so much,” he said. “It was such a lifetime love, I don’t know that I’ll ever experience anything like that again.”

So no, she wouldn’t say much at all, just, “I knew,” with a smile.

Growing up between these two worlds, with access to the depths of the internal as well as the wealth of the external, gave Gaspard a foundation upon which he’s built his life as an artist. Such folklore is the stuff great music is made of; references to Gaspard’s early life in Vermilion

Parish, and especially to his grandparents, permeate his body of work—especially in his 2022 album, Hoping Heaven Got a Kitchen

“They gave me the courage to say, ‘I know who I am,” he said.

Listening to Gaspard’s discography, you’ll hear more influence from Otis Redding and Al Green than Iry LeJeune or Nathan Abshire; he plays guitar and harmonica instead of an accordion or a fiddle. When asked, he’ll lean toward soul and blues as classifications for his body of work, and often he’ll lift up the umbrella of folk or Americana. But still, he doesn’t shy away from dubbing his music “Cajun,” because the fact is, “I am undeniably Cajun, and I’m not outrunning who I am.”

As a young musician, Gaspard’s impression of Cajun music was that it existed on a pedestal, in the often-isolated realm of strict tradition and Acadiana dancehalls, to be admired from afar. By contrast, he found himself connecting deeply with the universality, timelessness, and tradition of adaptation within classic African American soul and blues.

“It just comes from something that is a deep resonance that everyone needs,” he explained. “I think all of the best music, it’s just ripples of what soul and blues music is. That music makes me want to tell a story, it makes me want to sing my guts out. But it also just makes me want to love and nurture close.”

There’s a conviction to the blues, an “undeniability,” as Gaspard describes it, that can also be heard in the old Cajun music. “They’re not just doing vocal runs, they’re singing from a particular place. They have these crazy, impeccable voices that are so specific but so full of yearning ... Tapping into that is what I enjoy doing most. Because that translates itself to the highest form of art, which is just making people feel at their depths.”

The link Gaspard draws between the two genres is not without precedent. In the 1950s, many Cajun and Creole musicians began leaning more mainstream, drawing in the sounds of rising genres of rock n’ roll, country, soul, and blues, while maintaining a regional flare. The genre eventually became distinguished as “Swamp Pop,” a label Gaspard also proudly embraces as a way to define his music.

“It’s like, all these Cajun artists that heard the conviction of soul and blues music—they wanted to provide their version of it, so they covered some of these songs, or wrote songs that were specifically emulating that,” he explained. “But what was inescapable was their heritage, their legacy of being Cajun men and women. So, there is this sprinkle of dust of Cajunness on it, an asterisk that it’s not purely blues music, and it’s performed by Cajuns.”

As an artist, Gaspard holds a supreme reverence for the soul and blues genres that he continues to be drawn to, “but

I’ll never be a Black soul artist,” he said. “I love this music, it’s undeniable for me. How do I filter it through me, so that it feels like it is me, not like I’m trying to mimic someone else?”

The answer, he found, was to try to integrate the language of his ancestors, the story of his ancestors, into his songs. He wanted to pull his Cajunness off the pedestal and into his art, into himself.

“I don’t want my Cajun heritage to live in a room in a different house from who I am,” he said. “I think we’ve com-

In 2023, Gaspard received a grant from the Acadiana Center for the Arts’ ArtSpark program to create a bilingual, conceptual folk album telling the story of his Acadian ancestor, Angelique Pinet Lege, who traveled with her three sons to Louisiana following Le Grand Dérangement and who serves, according to Gaspard, as “the Divine Feminine perspective” of the story.

Titled Avec le Courant, the project is still in production as Gaspard has

“THERE IT IS. THIS IS THE MOMENT I’VE BEEN WAITING ON FOREVER. I HAD THIS DREAM TO DO ALL THESE THINGS, TO EXPLORE MY HERITAGE AND LEGACY, TO TRAVEL AND PERFORM, TO GET ON NATIONAL TELEVISION AND SING IN THE CAJUN LANGUAGE, AND IT IS HAPPENING.” —DUSTIN DALE GASPARD