The Future Business District

October 2021

Anne Green, Rebecca Riley, Alex Smith, Ben Brittain, Hannes Read

With contributions on provocation pieces on megatrends from:

Abigail Taylor

Alice Pugh

Georgina Hunt

Liam O’Farrell

Magda Cepeda Zorrilla

Ros McDermott

Verity Parkin

The research team worked closely with the Future Business District Project Team and wider executive at Colmore BID as well as the independent Advisory Panel established to support the Study.

Future Business District Steering Group

Mike Best, Chair

Nicola Fleet-Milne

Cllr Sir Albert Bore

Cllr Brigid Jones

Alan Bain

Alex Tross

Kevin Johnson, Future Business District Project Director (Urban Communications)

Michele Wilby, Chief Executive, Colmore Business District

Jonathan Bryce, Operations Manager, Colmore Business District

Chris Brown, Communications Manager, Colmore Business District

Katy Paddock, Events Manager, Colmore Business District

Advisory Panel

Alex Bishop (Chair)

Joe Barratt

Anita Bhalla

Joel Blake

Andrew Carter

Simon Delahunty-Forrest

Nigel Driffield

Rosie Ginday

John Griffiths

Adam Hawksbee

Martin Prince-Parrott

Rory Sutherland

Supporters: Centre for Cities, Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce

The West Midlands Regional Economic Development Institute and the City-Region Economic Development Institute Funded by UKRI

FOREWORD

Mike Best, Chair, Steering Group and Kevin Johnson, Project Director

We started thinking about the impact of the pandemic on the business district just weeks into the first lockdown in 2020. The hollowing out of our city centres, switching to remote working and online shopping, not only reduced office occupancy but had a devastating impact on retail, culture and hospitality as well as transport.

Many policymakers, business leaders and commentators turned their attention to the future of work, offices and high streets. But there was little focus on the organisms of business districts, the places where offices co-locate with the supporting infrastructure of transport connections, business networking, conferencing, hotels, retail, hospitality and cultural attractions, public realm and green spaces all in close proximity to town halls. These mature ecosystems of large corporates, SMEs and independent businesses have historically thrived by and from each other.

The business district was facing an existential crisis.

For Colmore Business District, this was particularly acute as the historic heart of a thriving BPFS sector. The area has revived with new investors and occupiers of Grade-A office developments, the refurbishment of many older buildings and an explosion of food and drink offers.

It was clear COVID-19 would have a ‘supercharging’ impact on several underlying developments. Technology and automation, sustainability and inclusivity were not trends ushered in by the pandemic, but it accelerated them and reshaped attitudes and values.

We believed the business case for cities – and their commercial districts – would need to be refreshed and restated, countering claims that ‘the office is dead’ whilst acknowledging new ways of working have become embedded.

The two questions we set - about the long-term impact of COVID-19 and keeping business districts successful as part of the wider city centre - needed a deep dive. But we wanted to co-produce the work rather than simply issue a contract.

It was also important to work closely with public partners, our fellow city centre BIDs and other stakeholders.

We were delighted to engage City-REDI | WMREDI at the University of Birmingham, supported by UKRI, working with the Office of Data Analytics at the WMCA to deliver the research programme. They worked alongside Colmore BID’s Steering Group and Project Team, our independent Advisory Panel and partners in shaping the research and providing us with the insight to develop the vision and emerging propositions for the Future Business District.

Our thanks to the team and their commitment to real partnership working.

The resulting document we have produced as Colmore BID, The Space Between, builds on the research in this report and provides the basis for us to curate the Future Business District.

SUMMARY

Context

Prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic Birmingham enjoyed a period of sustained economic growth. Birmingham city centre was transformed physically and economically, with a thriving business, professional and financial services (BPFS) sector driving high levels of business tourism, alongside vibrant hospitality and retail sectors.

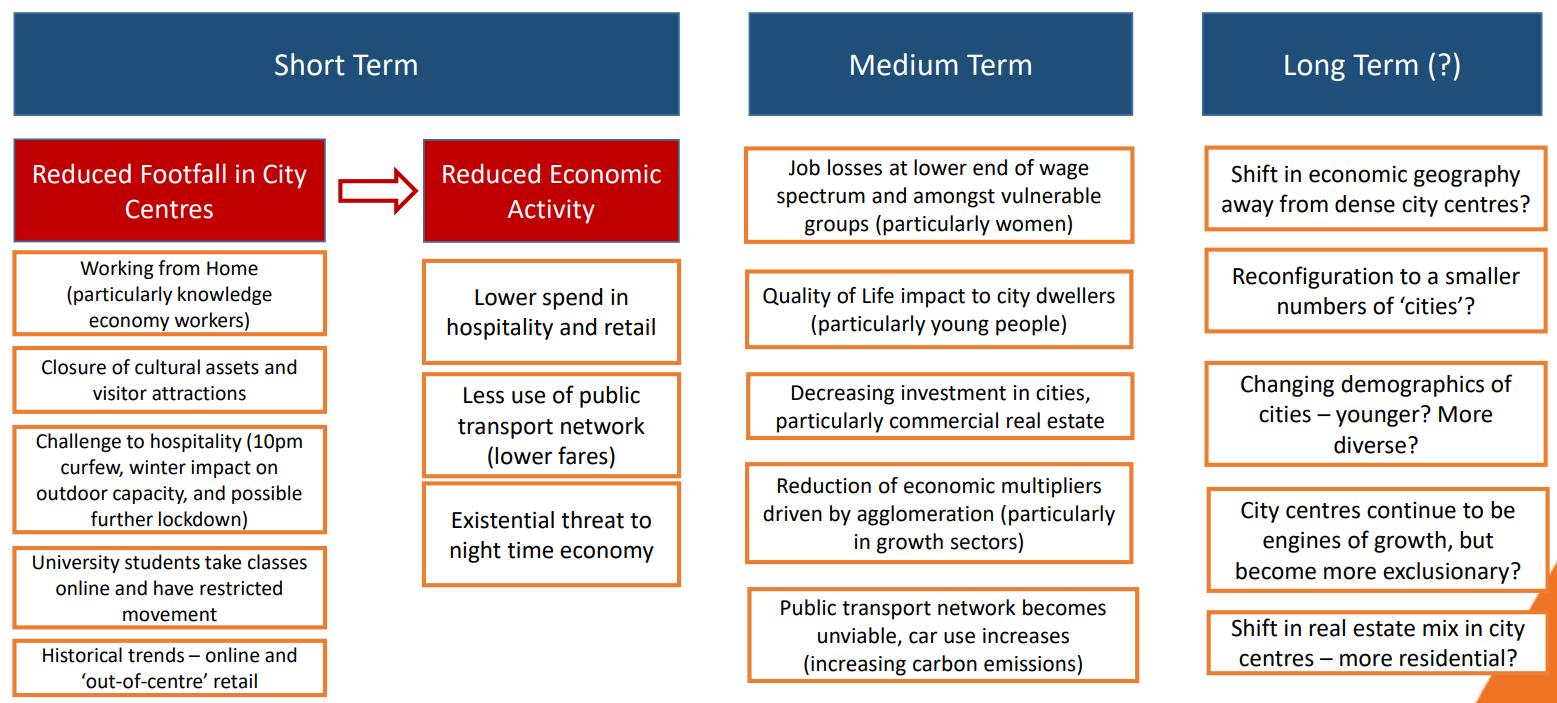

In March 2020 the instruction to work from home and the shutdown of hospitality and retail in the first national lockdown brought rapid and radical change to city centre business districts. Since then the economy and society has seen phases of opening up, closing down and opening up once again. Individuals and firms have had to respond in real time to a developing health and economic situation. Cities have overcome pandemics and shocks before, but the recent period has no recent precedent.

The ‘Future Business District’ Study

As part of its response to the radical changes being experienced, the Colmore Business District (Colmore BID) established the Future Business District Study to inform long-term recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and offer policy directions on best practice for central business districts across the UK. It commissioned a team from City-REDI (University of Birmingham) and the West Midlands Combined Authority to deliver a research programme, supported by an independent Advisory Panel and a range of partners.

The project focused on prospects for Birmingham’s city centre business district in the medium- and longer-term, addressing two questions:

1. What is the likely long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on city centre business districts?

2. How can we ensure they remain successful as places to attract businesses and people and contribute to vibrant city centres?

An initial research phase involved an evidence and data review; workshops on ‘megatrends’; and a call for evidence. A subsequent engagement phase involved in-depth interviews with 21 businesses and stakeholders; Advisory Panel meetings to help develop future scenarios; facilitated discussions on future infrastructure, place and urban experience; supplementary individual meetings; and engagement with a broader community panel on working patterns and broader use of cities and city centres.

Historical and geographical perspectives

Pandemics in history have had social, economic and political impacts and have spurred developments in medicine. Cities have survived and re-emerged in a relatively strong position in the wake of these pandemics. Contemporary economic geographers argue that the ‘agglomeration advantages’ of cities are likely to remain even given the existence of alternatives to face-to-face working for many office workers because of the importance of proximity in collaborative knowledge creation (especially in finance and business services, high tech and media clusters) and due to shortcomings in the extent to which video-conferencing can replicate for in-person interaction. The dense urban labour markets of large cities, and their associated friendship networks and other amenities, are attractive to many highly educated young people.

The longer the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic lasts, the greater the likelihood that some shifts in activity associated with the initial response to lockdown result in more radical, permanent shifts.

Trends shaping the future business districts

From the research and engagement phases the following key trends were apparent:

1) Digital transformation of the workplace and tech disruption will continue to impact on business models and where and how work is done.

2) Hybrid working is here to stay for many (not all) – two-three days working in the office and threetwo days working from home (or elsewhere), especially in sectors such as business, professional and financial services, driven by broader ‘life’ considerations as well as ‘work’ ones.

3) Access to talent is ever more critical and there is an increased demand for skills and jobs that emphasise human interaction - networking, problem solving, collaboration, selling, creating and innovating.

4) Future business districts will need to be even more focused around connections and culture – a place to connect, interact and collaborate and to enjoy urban experiences.

5) Safety – on transport, in public spaces and at offices – has risen up the agenda considerably. Meanwhile, encouraging commuters back onto public transport system – that feel safe and meets the needs of new working patterns – is a major challenge.

6) Demand for recognising social value, climate change and inclusivity among consumers and employees will continue to rise.

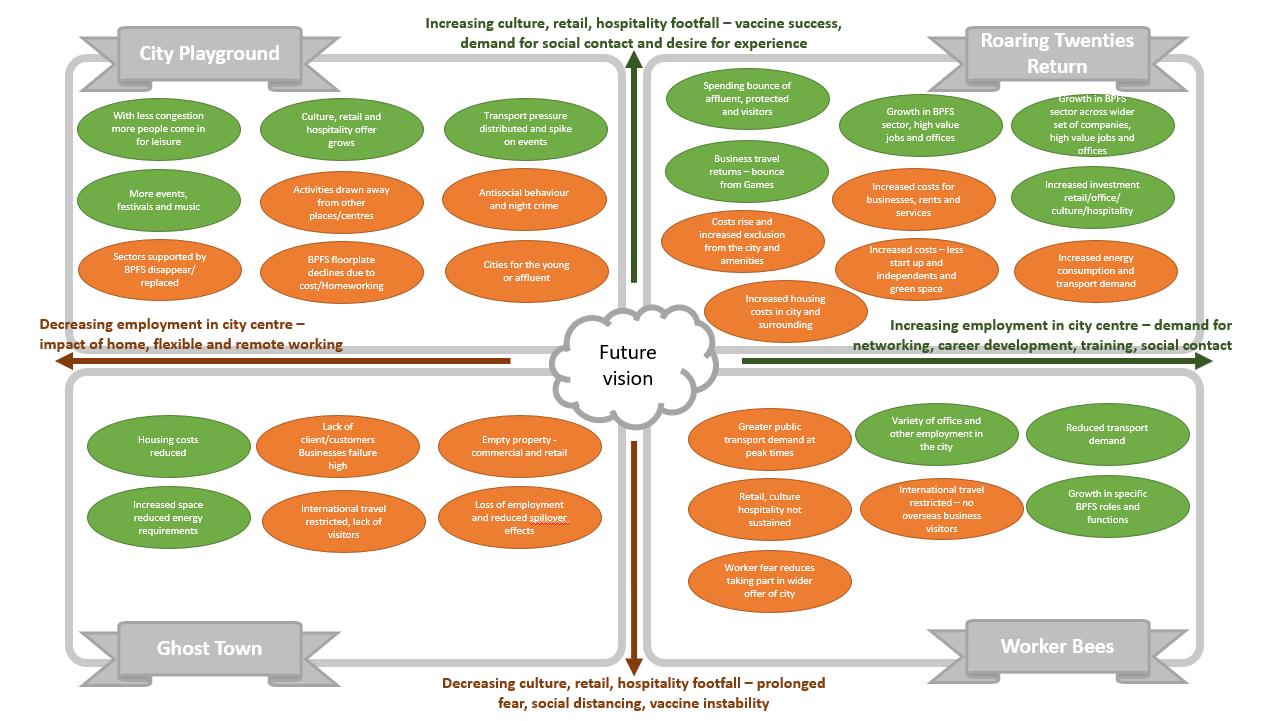

Future Scenarios

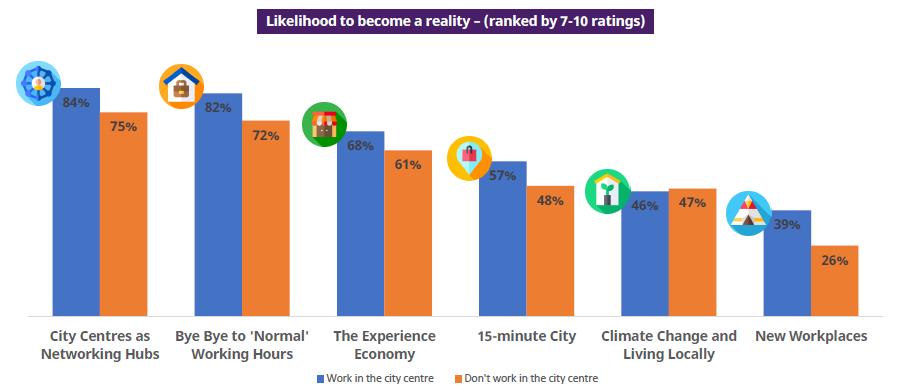

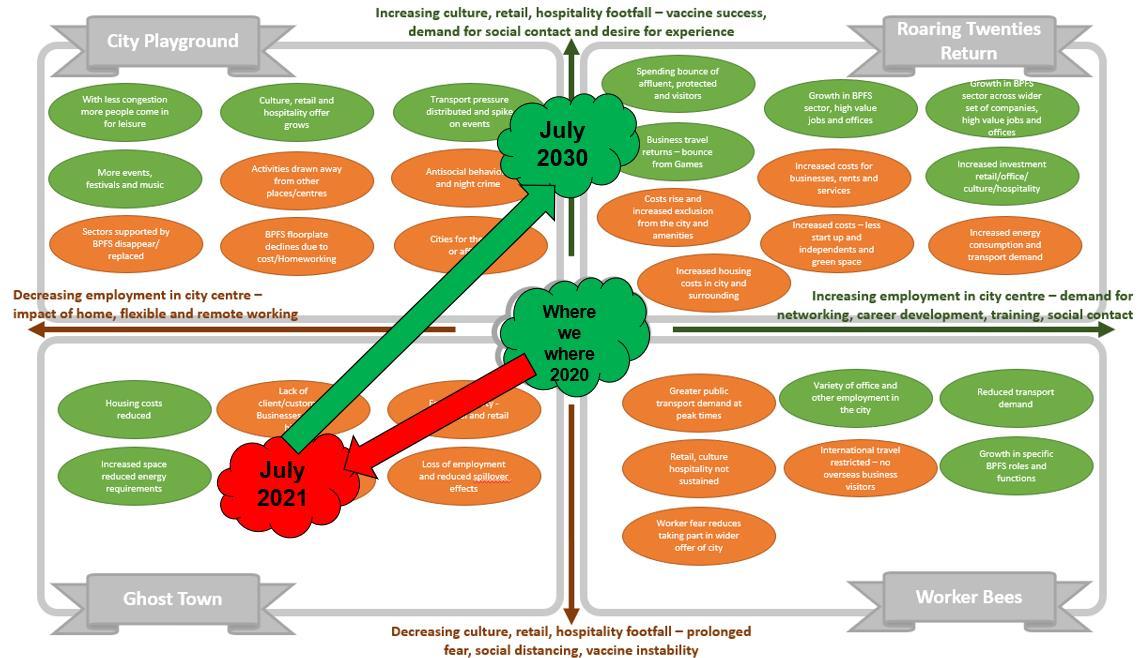

Four scenarios were developed that analysed possible outcomes based on changes in employment in the city centre and in footfall associated with culture, hospitality and retail.

The preferred vision Is one which sees increasing employment in the city centre and increasing culture, hospitality and retail footfall. It would avoid the business district becoming a ghost town or being solely focussed on work. This would encourage workers in the BPFS sector to return to the city centre not solely for work but for the wider benefits of city life. This requires a diverse offer to meet the needs of office workers operating on a hybrid working model, alongside the needs of consumers of cultural, retail, entertainment and leisure activities. It also requires action to positively address inequalities and lack of inclusion and mitigate against spatial and economic overheating.

Themes for action

The key findings from the interviews, and reflections on them, were distilled into one overarching theme and six further themes around which policy-makers, researchers, central and local government, as well as wider business partners and other stakeholders, can join together.

The Space Between – This overarching theme highlights how a high-quality public realm, plus hospitality and retail venues, together with green and open spaces, make the city centre attractive to businesses and individuals, and support well-being. The ‘space between’ is the hidden, unrecognised space utilised on an ongoing basis - including transport, public realm, green space, cultural/ entertainment space - which is essential to the growth, performance and activity of the ‘space within’ businesses. It provides opportunities for workers, residents and visitors to relax, connect and recharge.

1) Connections and Culture - A place to meet remains the big idea behind successful cities and their central business districts; office workers and consumers are likely to be driven back into city centres by the need to connect with others via networking and socialising. More collaboration and meeting spaces and leisure/cultural experiences will be needed to keep people returning to the city to connect and exchange.

2) Agile and Flexible – There is considerable appetite amongst office workers for more flexible and hybrid working Workspaces and employees are becoming more agile, so the business environment needs to support this trend

3) Colmore Collaborates – The prominence of hybrid working in the short- to- medium-term is likely to have a significant impact on how floor space demands will evolve and how workers interact with the office as a social space, calling for different types of space and placing prominence on the ‘office as a destination’ and on exploiting opportunities for growing collaborative workspaces to be utilised by more users.

4) On the Move – There is an opportunity to re-shape an integrated transport system, with greater reliance on active travel modes and the evolution of public transport to accommodate the changing needs of the day-time and night-time economies.

5) Safe and Sound - The priority people attach to safety on transport, in offices and in public places has grown, the future business district will need to meet rising expectations.

6) Open to All – The emphasis is on opening and enhancing the city centre business district to more businesses and more people, and to harness green and open spaces, so resonating with concerns about climate issues, inclusivity and well-being.

Recommendations

Businesses need to:

• Understand the impact their business decisions have on place and how their offices interact with the space they are in and make this an active part of business case development and corporate social responsibility activities.

• Work with local businesses to help stimulate demand for their services, ideally through a focus on employee benefits, career development, networking and training.

• Lobby and invest in better transport, safety and external space development in order to create an environment workers and visitors want to come back to - or visit for the first time.

The public sector needs to:

• Encourage the development of a city with green space, open places and a high-quality public realm that promotes well-being through providing safe spaces for people to come together, as well as venues to enjoy leisure and participate in culture.

• Rethink transport in light of the Covid-19 pandemic and work with transport operators and businesses to design systems that promote worker return and engagement with the city.

• Promote the city, dispel negative images and attract new investments, visitors and workers which complement and fit with the focus of the city centre BIDs.

There is a greater need than was formerly the case for a flexible BID model that can be a city curator that promotes and accelerates:

• Being the place for hybrid working: Supporting businesses to adapt to a hybrid working model and its implications. This entails backing both core BPFS businesses in the district but also taking account of the spillover effects on retail, hospitality and accommodation services

• Being the centre of experience for employees: Developing the experience portfolio of the city centre business district – attract former city centre workers back and engaging a new diverse workforce with the enjoyment of interaction and experience of place and activities

Being the place to network and grow: Developing networks and communities – with a focus on recruitment, training, career development and opportunities for innovation for a diverse workforce in a hybrid world.

1. INTRODUCTION

Context

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic the UK, the West Midlands and Birmingham enjoyed a period of sustained economic growth, with employment rates reaching historically high levels. Birmingham city centre was transformed physically and economically – with a thriving business, professional and financial services (BPFS) sector driving high levels of business tourism, alongside a vibrant retail and hospitality sector.

Circumstances changed in the first quarter of 2020 with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. On 26 March 2020 national lockdown measures were put in place, with an instruction to those who could do so to work from home. June and July 2020 saw a re-opening first of schools and non-essential shops, followed by a re-opening of other shops, pubs and restaurants. In August 2020 an ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme was introduced to provide a boost for the latter. Late September 2020 marked a return to ‘work from home’ advice to those able to do so and the introduction of a curfew for the hospitality sector. In mid-October 2020 a tiered-system for local lockdowns was introduced, prior to a four-week second national lockdown across England from early November 2020. In December 2020 the local tiered system was in force with restrictions varying across tiers, followed by the imposition of a third national lockdown from 6 January 2021. From early 2021 the national vaccination programme was rolled out at pace. Spring 2021 saw a phased reopening from the third national lockdown, with schools reopening in March, non-essential shops in April along with outdoor opening of hospitality venues. Further easing of restrictions followed in May with a final lifting of restrictions in mid-July 2021. At the time of writing from August 2021 daily confirmed coronavirus cases are rising once again.

The timeline outlined above is important for three reasons. First it outlines the dynamism of the situation over the period since March 2020. Secondly, it hints at the variable impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic by sector1 – with the retail and hospitality sectors particularly hard hit (and amongst some of the largest recipients of furlough and other government support) while many office-based workers in the business, professional and financial services (BPFS) sector were able to perform their roles working from home. Thirdly, it provides the context for individuals’ and firms’ responses to the developing health and economic situation. This period is a time like no other, with no recent precedent.

The instruction to work from home where possible and the shutdown of hospitality and retail brought rapid and radical change to city centre business districts typically characterised by office workers and the hospitality and other services that support them. As part of its response to the radical changes experienced, the Colmore Business Improvement District (BID), which was set up in 2009 to project manage improvements and the provision of services to the business quarter of Birmingham, established ‘The Future Business District’ Study to inform long-term recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and offer policy directions on best practice for central business districts across the UK. It commissioned a team from City-REDI at the University of Birmingham and the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) on.to deliver the research programme. In particular, the project focused on prospects for Birmingham’s city centre business district in the medium- and longer-term. The project has been a collaborative endeavour, with Colmore BID leading and shaping the project

1 WMREDI (2021). The State of the Region, WMCA. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-socialsciences/business/research/city-redi/2021/state-of-the-region.pdf

throughout, with the input of an Advisory Panel2 commenting on emerging findings and possible responses. The research and engagement elements of the work presented here are taken forward in a response developed by the Colmore BID.

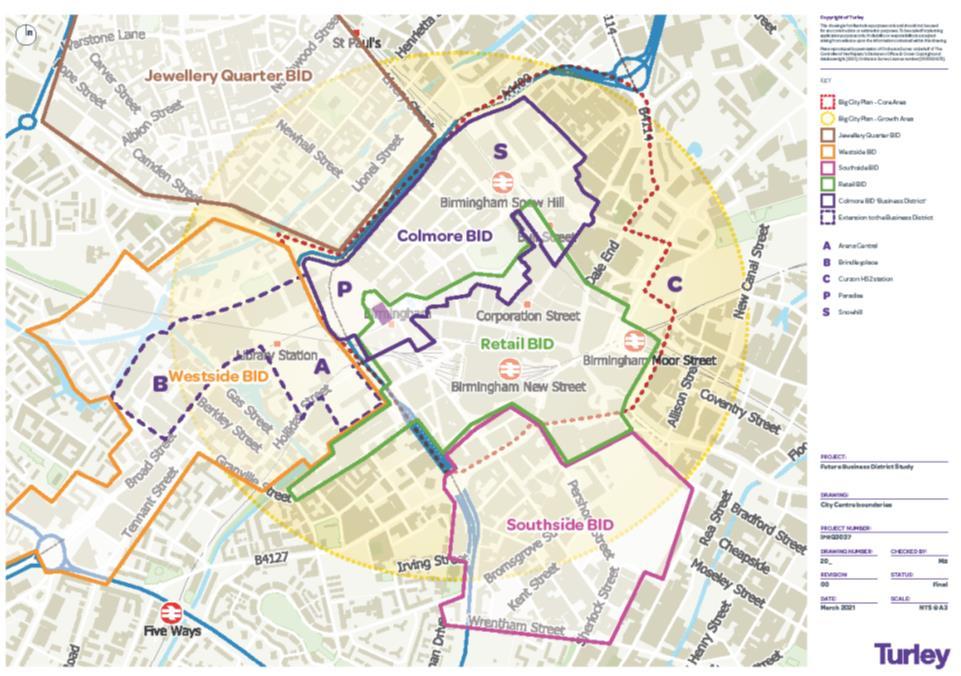

As well as WMCA, the Future Business District project was quickly backed by Birmingham City Council. The Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership (GBSLEP) and the other four city centre BIDS – Jewellery Quarter, Retail, Southside and Westside - supported the Study. Commercial support came from Balfour Beatty and MEPC with additional input from Centre for Cities and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce.

Research questions

This research addresses two key questions:

1. What is the likely long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on city centre business districts?

2. How can we ensure they remain successful as places to attract businesses and people and contribute to vibrant city centres?

Addressing these research questions involved analysis of data and trends relating to the future uses and functions of city centres and city centre business districts, an evidence review, primary research with local/regional stakeholders, and engagement with industrial strategies and economic recovery plans at local, regional and national scales (as outlined further in the Methodology section below).

The research has a specific focus on business, professional and financial services (BPFS) workplace communities and interdependencies with creative, digital, retail, leisure/hospitality and cultural sectors which play a key role in the successful functioning of city centres; (hence it does not attempt to cover the full breadth of the workforce in all sectors and all locations). It has sought to learn from previous experience of city centre responses to depressions, conflicts, pandemics, and major technological and behavioural changes. However, its main focus is on the present and the future (especially the period to 2030), with particular emphasis on the changing nature of work, the expectations of ‘Generation Z’ (i.e. the cohort of people born after 1997 who have grown up with technology who are now entering the workforce) and the future uses and functions of city centre business districts In so doing it engages with related agendas on technological change and digitalisation, climate change, sustainability and green issues, city living and well-being.

Methods

The research reported here had two main phases: research and engagement.

The first research phase draws on five main components:

1. A review of the academic and policy literature relating to cities’ responses to shocks, economic trends, business developments and changing working patterns and associated implications.

2. A series of provocation pieces were written on topics encompassing future business models, future mobilities, health and well-being, hybrid workplaces and the future of work, adjusting business models and operations, attitudes and values, changing functions and functioning of places, local living, generational attitudes, and learning from previous crises.

3. Seven workshops held in February 2021 bringing together stakeholders from the West Midlands to discuss ‘megatrends’ – focusing on mobilities, health, hybrid workplaces and the future of work,

2 Comprising industry professionals, analysts and public sector stakeholders, all of whom had an acute insight into the Birmingham area and wider cities trends as result of either firms operating within Birmingham or public sector policy work.

business models and operations, attitudes and values, changing functions and functioning of places, and business districts.3

4. Compilation and analyses of secondary data sources to provide information on the impact of the pandemic on Birmingham city centre and the wider local area and to underpin the development of scenarios for discussion in the engagement phase of the research.

5. A Call for Evidence (see Annex A) on developments over the last 12 months and likely changes over the next 10 years, with a particular emphasis on hybrid working, changing office space requirements, doing business and transport implications. It also invited ideas on how city centre business districts should prepare for the future. The call was open to anyone with relevant expertise and was live from late January to early March 2021.

The second engagement phase, conducted in close collaboration with Colmore BID, involved consultation with stakeholders to provoke debate and invited wider contributions. It drew on the findings from, and also contributed to, the research phase. It had five main components:

1. Expert in-depth interviews with 21 businesses (both large firms and smaller enterprises across the Colmore BID area and wider city centre) and stakeholders (see Annex B for a list of questions) in the period from April to June 2021. Key topics addressed included hybrid working, (office) space requirements, (changing ways of) doing business, transport, place, and social, economic and environmental issues.

2. Three meetings with the Advisory Panel in the period from March to June 2021 to provide feedback on findings and help develop scenarios as the basis for discussions about likely and preferred possible futures and how to facilitate desirable and mitigate undesirable outcomes. (A fourth workshop to discuss the response to findings was held in early September 2021.)

3. Three follow-up workshops, facilitated and conducted in collaboration with Colmore BID in May and June 2021 to discuss scenarios and policy actions in more detail. These workshops were attended by selected invited interviewees and other stakeholders able to offer particular insights on ‘future infrastructure’ , ‘future place’ and ‘future urban experience’ .

4. Supplementary individual meetings with stakeholders with an interest and viewpoints to feed into the research. (These meetings took place between May and July 2021.)

5. Two separate engagement exercises, in early April 2021, with a broader panel of West Midlands residents participating in a Transport for West Midlands (TFWM) community panel, in which we sought views on working patterns and jobs and broader use of cities and city centres.

Structure of the report

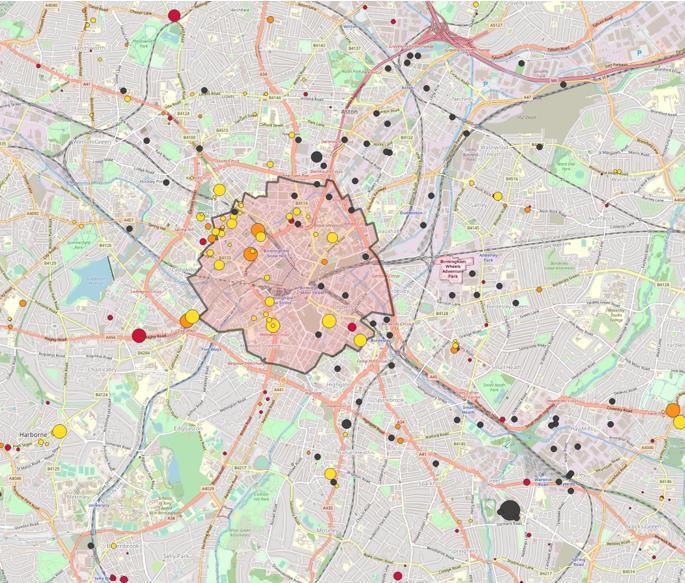

Section 2 of the report presents an evidence review drawing on the academic and grey literature and material in the provocation pieces outlined above. This section sets the broad context for the study, along with section 3 which outlines broad findings from discussions in the megatrends workshops. Section 4 presents an analysis of selected secondary data, focusing on Birmingham city centre and the wider city area and West Midlands.

Section 5 presents findings from the various consultations with businesses and stakeholders and incorporates material from deliberations with the Advisory Panel and views proffered in the initial call for evidence, while section 6 presents key headlines from an analysis of citizens’ views about changing working patterns and the future use of city centres from the Transport for West Midlands (TfWM)

3 We acknowledge UKRI for providing funding for research on ‘Megatrends and cities – understanding the future and its impact on three West Midlands’ cities’ which funded Megatrends Workshops and also partfunded production of ‘Provocation Pieces’ which are drawn on in this report. We also acknowledge the role of Future Agenda with whom we worked in developing and implementing the Workshops.

community panel Section 7 describes four scenarios outlining possible futures and which helped both prompt and further develop the future vision for the business district. Section 8 presents conclusions and recommendations.

2. EVIDENCE REVIEW

Introduction

This section outlines key themes from the extant evidence of relevance to the Future Business District. Types of evidence drawn upon include the academic and grey literature – including sources highlighted in the initial call for evidence. The section also draws on evidence presented in the provocations prepared in the period from January to March 2021 (see section 3).

The topics covered include macro level considerations, such as the role of cities and changes in the urban system – with reference to lessons from history and the role of agglomeration economies; technological change and implications for business models, employment and jobs; the rise of hybrid working and its wider implications, including for the use of offices; and aspects of health, well-being, design of the built environment and future mobility.

Changing cities: macro- and micro-geographic scales

It is instructive to consider the Future Business District in the context of wider historical and prospective urban trends. A distinction is made here between macro trends relating to the function of cities in international, national and sub-national urban systems and micro trends relating to the internal structure of cities. Both macro and micro trends are pertinent to the Future Business District.

Lessons from history4

There is a tendency at moments of crisis to see events as ‘unprecedented’, with economic models tending to pay insufficient attention to history and geography.5 Yet societies have quite considerable previous experience of pandemics and of severe economic crises.

The Black Death of the fourteenth century was a defining event of medieval Europe and is associated with the breakdown of feudalism.6 The ‘population shock’ resulting from 75-150 million deaths left a new world in its wake,7 with long-term impacts on urban development and population growth, and structural changes in national economies owing to major labour shortages. In England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries residents lived in the shadow of the plague and it has been estimated that in the years between 1606 and 1610 when Shakespeare wrote some of his greatest plays, London playhouses were not likely to have been open for more than a total of nine months.8

Around one hundred years ago the Spanish Flu of 1918-20 led to mandatory closures of schools, bars and restaurants, and libertarian protestors decried public health orders to wear face masks as “big government” overreach.9 Premature relaxation of measures led to subsequent waves which far outstripped the first in their intensity.10 It is estimated that this pandemic claimed the lives of 50-100 million people. In general, death rates were higher in cities than in rural areas, and were highest in

4 This section draws in part on material from O’Farrell L. (2021) Urban responses to pandemics and economic shocks in historical perspective, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

5 Garretsen, H. and Martin, R. (2010) ‘Rethinking (New) Economic Geography models: taking geography and history more seriously’, Spatial Economic Analysis, 5(2), 127-160.

6 Cantor, N. F. (2001) In the wake of the plague: the Black Death and the world it made. New York: Free Press.

7 Jedwab, R., Johnson, N. D. and Koyama, M. (2020) Pandemics and cities: evidence from the Black Death and the long-run. Washington, D.C.: George Washington University.

8 Greenblatt, S. (2020) ‘What Shakespeare actually wrote about the plague’, The New Yorker. 7th May.

9 Hauser, C. (2020) ‘The mask slackers of 1918’, The New York Times, 3rd August.

10 Wheelock, D. (2020) ‘What can we learn from the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 for COVID-19?’, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1st June.

deprived areas, so exacerbating inequalities.11 The social disruption of the pandemic undermined trust and constrained future economic growth.12

Medical science has progressed immensely since these examples from history. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was the first deadly infectious disease of the 21st century. It started in China in November 2002 and by August 2003 it had spread to 29 countries, with a cumulative total of 8,422 cases and over 900 deaths. East Asian countries with dense urban populations were amongst those worst affected. One such was Hong Kong. Analysis of the impact of SARS in Hong Kong shows that while there was a negative shock on the demand, with local consumption and travel and tourism affected in the short-run, initial alarmist reports of the extent of the impact were not borne out and when the outbreak was brought under control the economy rebounded rapidly.13 The H1N114 pandemic (“swine flu”) pandemic, starting in Mexico in April 2009 was more wide-reaching, infecting over 10% of the global population. Estimates of the death toll varied from 20,000 to over 500,000. Much of the concern regarding this pandemic was its impact on formerly healthy young people.15

Pandemics in history have had social, economic and political impacts and have spurred developments in medicine. Cities have survived and re-emerged in a relatively strong position in the wake of these pandemics. So, why is this the case and what are the implications for the Covid-19 pandemic, especially given the wider availability of alternatives for face-to-face work and shopping?

Agglomeration economies and macro-geographies

The key feature of central business districts in major cities in wider metropolitan areas is that they provide advantages of agglomeration economies. Leading economic geographers have highlighted the critical mass in cities of talent and assets and the consequent buzz, the potential for exchange of ideas/ innovation in urban centres,16 and the associated growth in employment in business, financial and professional services, together with technology-rich activities However, the proximity that is important in harnessing agglomeration advantages became a ‘friction’ with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic as many office workers with workplaces in the centre of the largest cities worked from home.

17

Yet the same economic geographers who highlight the important role of agglomeration economies counter against this friction leading to a widespread change in macro-geographies in the longer-term. They argue that the Covid-19 pandemic is unlikely to alter the winner-take-all economic geography and spatial inequality of the global city system in a significant way.18 After all, the conversion of office work to remote work from employees’ homes, and the mass substitution of information and communications technologies for physical movement, so enabling a widespread shift in population and employment from big cities to towns and semi-rural settlements, did not occur with the

11 Riley, R. (2020) ‘A Review of the Impacts of the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic’, City-REDI blog, 25th June.

12 Aassve, A., Alfani, G., Gandolfi, F. and Le Mogile, M. (2020) ‘Pandemics and social capital: from the Spanish flu of 1918-19 to COVID-19’, Vox EU Centre for Economic Policy Research, 12th March.

13 Siu, A. and Wong, Y. C. R. (2006) ‘Economic impact of SARS: the case of Hong Kong’, Asian Economic Papers, 3(1), pp.62-83.

14 The same strain as caused the Spanish Flu.

15 Huremovic, D. (2019) ‘Brief History of Pandemics (Pandemics Throughout History)’, Psychiatry of Pandemics 16, pp. 7-35.

16 Storper, M. and Venables, A.J. (2004) ‘Buzz: Face-To-Face Contact and the Urban Economy’, Journal of Economic Geography 4(4), pp. 351-370.

17 Nathan, M. (2020). The city and the virus. https://maxnathan.medium.com/the-city-and-thevirusdb8f4a68e404

18 Florida R., Rodriguez-Pose A., Storper M. (2021) ‘Cities in a post-COVID world’, Urban Studies, DOI: 10.1177/00420980211018072

widespread adoption of the internet.19 They argue that the agglomeration advantages of cities are likely to remain both because of the importance of proximity in collaborative knowledge creation20 (especially in finance, high tech and media clusters),21 and because of shortcomings in the extent to which video-conferencing can replicate for in-person interaction.22 Young educated people, in particular, have been attracted to the dense urban labour markets of the largest cities,23 and their associated friendship markets and other amenities, often choosing to live in central areas.24 However, the longer the Covid-19 pandemic lasts, the greater the likelihood that some of the shifts in activity associated with the initial response to lockdown result in more radical permanent shifts.25

Changing functions of places and urban micro-geographies

While the consensus amongst leading economic geographers is that the largest cities are likely to retain their pre-eminence in the urban system, there is acknowledgement that their functions could change. Their role as meeting places, including for cultural activities, is likely to become more important, while their prior roles as office hubs and shopping centres may be somewhat diluted.26 These trends have implications for the built environment (as discussed below).

Covid-19 has contracted the psychology of space, making the local increasingly important – especially during lockdowns,27 leading some people to reassess what they want from a place. In the immediate aftermath of lockdown, ‘Zoomshock’28 resulted in a substantial amount of economic activity shifting away from traditional ‘workplaces’ to ‘residences’ in suburbs and more accessible areas outside cities. Trends in the housing market suggest that larger residences with gardens in attractive areas are at a premium, with some workers trading off longer for less frequent commutes to the workplace.29

Within urban areas, an increase in local living is consistent with growing interest in concepts of ‘complete neighbourhoods’/ ’20-minute neighbourhoods’/ ‘15-minute cities’ (explored in places such as Portland Oregon, Paris and Melbourne), based on principles of proximity, diversity, density and ubiquity, with neighbourhoods fulfilling functions of living, working, supplying, caring, learning and enjoying.3031 Greater local living associated with these concepts has implications for mobility, with shorter journeys, creating more opportunity for walking and cycling and reducing dependence on cars.

19 Couclelis, H. (2020) ‘There will be no Post-Covid city’, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 47(7), pp. 1121-1123.

20 Crescenzi, R., Nathan, M., and Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2016) ‘Do inventors talk to strangers? On proximity and collaborative knowledge creation’, Research Policy 45(1), pp. 177–194.

21 Florida, R. (2020) Cities and the COVID-19 Crisis, Centre for Cities.

22 Spicer, A. (2020) ‘Finding endless video calls exhausting? You’re not alone’, The Conversation

23 Moos, M. (2016) ‘From gentrification to youthification? The increasing importance of young age in delineating high-density living’, Urban Studies 53(14), pp. 2903–2920.

24 Cortright, J. (2020) Youth movement: Accelerating America’s urban renaissance. City Observatory, 14 June. Available at: https://cityobser vatory.org/youthmovement/

25 Nathan, M. and Overman, H. (2020) ‘Will coronavirus cause a big city exodus?’, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 47(9), pp. 1537-1542.

26 Florida R. et al. (2021) op cit.

27 Hunt, G. (2021) Local Living, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

28 De Fraja G., Matheson J. and Rockey J. (2020) ‘Zoomshock: The Geography and Local Labour Market Consequences of Working from Home’, Covid Economics, Issue 64, 13 January 2021, 1-41.

29 Cheshire, P. and Hilber, C. (2020) COVID-19: Crashing the Economy so what will it do for the housing market? Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

30 Green, A. and Riley, R. (2021) ‘Implications for places of remote working’ in Wheatley, D., Hardill, I. and Buglass, S. (ed.) Handbook of Research on Remote Work and Worker Well-Being in the Post Covid-19 Era, IGI Global, pp. 161-180.

31 Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C. and Pratlong, F. (2021) ‘Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities’, Smart Cities 4(1), 93-111.

As well as being environmentally beneficial, active travel brings physical and mental health benefits (discussed below).

Technological change

Changing business models32

Increasing levels of digitalisation and automation associated with ongoing technological change are perhaps foremost amongst key trends underlying changing business models. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a rapid acceleration of these trends. As a result, businesses have become increasingly vulnerable to advanced cyber-attacks, which represent one of the biggest risks to business operations 33 Technological advancement and the inherent interconnectivity and transparency of smart cities enhances their vulnerability.34 Disruptive technologies, such as AI, augmented reality, virtual reality, sensors and blockchain, drive such changes while also generating new products and services.35

Other ‘megatrends’ impacting on business models are environmental sustainability, which has now become a necessity for firms, and growing prominence of ethical considerations, marked by a sustained shift to ethical buying habits. ‘Generation Z’ (i.e. the cohort of people born after 1997 who have grown up with technology who are now entering the workforce) place particular emphasis on employers adopting an ethical corporate social responsibility strategy and mainstreaming equality, diversity, and inclusion practices.36 Contrasting tastes of different generations impact on consumption. Whilst six in ten Millennials agreed that they would choose a brand because it supports a cause they believe in, only one in three Baby Boomers said the same 37

The shift to online and experiential retail

Given the importance of city centres and urban high streets for shopping, the shift to online retail is of particular relevance to the future of city centres. The move to online retail was well-established before the Covid-19 pandemic with the number of physical stores in decline while the number of distribution centres increasing. The British Retail Consortium38 and Retail Economics39 both pointed to a continuation of a significant transfer from in-person retail to online retail, but this trend has accelerated as a result of the pandemic. Midway through 2020 footfall in retail centres remained

32 This section draws in part on material from Pugh, A. (2021) Changing Business Models, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

33 Airmic (2020) Top risks and megatrends 2020 Airmic annual survey report, https://www.airmic.com/system/files/technical-documents/Airmic-Survey-Report-top-risks-and-megatrends2020_0.pdf

34 Roke Manor Research (2020) Cyber resilience and the UK’s evolving Smart City ecosystem https://www.roke.co.uk/media/f13bv4mi/insights-2020-summer-cyber-resilience-and-the-uks-evolving-smartcities-pdf.pdf

35 EY (2018) What’s after what’s next? The upside of disruption Megatrends shaping 2018 and beyond https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/megatrends/ey-megatrends-finalonscreen.pdf

36 Francis, T. and Hoefel, F. (2018) ‘True Gen’: Generation Z and its implications for companies. São Paulo: McKinsey & Company.

37 Deloitte (2020) Shifting Sands: The Changing Consumer Landscape. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/consumer-business/deloitte-uk-shiftingsands-changing-consumer-landscape.pdf

38 British Retail Consortium (2019) A vision for the UK retail industry https://brc.org.uk/media/601330/avision-for-the-uk-retail-industry.pdf

39 Retail Economics (2019) The Digital Tipping Point: 2019 Retail Report, Retail Economics, Womble Bond Dickinson.

significantly reduced and store closures had increased by 25% since 2019.40 Property managers and developers are looking to reposition urban shopping centres to reduce their retail space and repurpose vacant units into homes, hotels and workspaces.41

Commentators expect that this shift to online is structural, with consumers continuing to favour online retail in product categories where they can get more competitive prices and greater variety online. Concurrently the trend towards experiential retail is expected to gather pace, with showrooms for customers to try out products before buying them online. 42 Competing with online retail by creating an experience blurs the line between leisure and retail.43 Creating a destination entices younger consumers, dubbed the ‘Instagram generation’, who want to be able to document their experiences.4445 Primark in Birmingham city centre now provides additional in-person services such as a beauty studio, and a Disney themed café 46 Covid-19 has also accelerated the desire for experiences, with many people beginning to place more value on experiences than goods.

Retailers and other businesses have an opportunity to cater towards the demand of an ageing population in the UK (i.e. the growth of the ‘grey pound’).47 Older people are more likely to spend and hold a significant amount of wealth. People aged 55-70 years make up around 23% of the UK’s population and are able to take part in online shopping as much as other demographic groups, as 71% of baby boomers in the UK have a smartphone.4849

There has also been a shift to increased spending in local independent retailers.50 This trend could see a growth in local, independent businesses that bring high streets a unique retail offering to counter generic online shopping and out-of-town retail parks. Local high streets that are authentic, human and unique are likely to fare better with Generation Z consumers, who are committed to environmental protection and supporting local industry 51

40 Jahshan, E. (2020) ‘14,000 shops have shut down so far in 2020, a +25% increase on 2019’, Retail Gazette, 28th September. Available at: https://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/2020/09/14000-shops-have-shut-down-sofar-in-2020-a-25-increase-on-2019/.

41 Clarence-Smith, L. (2021) ‘Hammerson’s vacant shops to be given change of use’, The Times, 6 August.

42 KPMG (2021) The Future of Towns and Cities post Covid-19, https://home.kpmg/uk/en/home/insights/2021/01/future-of-towns-and-cities-post-covid-19.html

43 Litherland, E. (2021) ‘Experience is Everything’, blog.yorksj.ac.uk, https://blog.yorksj.ac.uk/ellieglobalfashionconsumers/2021/01/12/experience-is-everything/

44 Buni, J. (2019) ‘For the High Street to Survive, Retailers Must Put Customer Experience First’, Retailgazette.co.uk https://www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/2019/04/comment-high-street-survive-retailersmust-put-customer-experience-first/

45 Nicholas, B. (2019) ‘Can Experiential Save the High Street?’, Campaignlive.co.uk https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/experiential-save-high-street/1667575

46 See https://stores.primark.com/united-kingdom/birmingham/38-high-street/primark-cafe-with-disney

47 MacGinnis, G. (2020) ‘Why No Products for Older People?’, Innovateuk.blog.gov.uk, https://innovateuk.blog.gov.uk/2020/11/10/why-no-products-for-older-people/

48 Baines, A. (2019) ‘Getting to Know the Baby Boomers: Their Presence in the Online Retail Sector’, Walnutunlimited.com, https://www.walnutunlimited.com/getting-to-know-baby-boomers-their-presence-inthe-online-retail-sector/

49 Kelion, L. (2017) ‘Smartphone Sales Boom with Over-55s’, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology41319684

50 Savills (2020) The initial impact of Covid-19 on the retail and leisure market. London: Savills.

51 Hunt, G. (2021) op cit.

Implications for employers and jobs

The technological and other changes outlined above have implications for the types of jobs available and for skills required.52 Sales and clerical roles in business sectors are particularly vulnerable to automation.53 In the medium-term, there are particular concerns about a shortfall in basic digital skills.54 Employees with a range of social, emotional, analytical, interpretative and digital skills are likely to be best placed to adapt to changing job requirements,55 so pointing to a trend towards increasing labour market inequalities.

To retain and attract the skilled workers they require, employers need to pay cognisance to the preferences and motivations of different generations in the workforce. Despite growing with technology, those in Generation Z are less enthusiastic about remote digital working than is often assumed. 56 Returning to physical workplaces and creating opportunities for social interaction in the office and the wider business district and city centre is in line with their preferences for collaboration and active engagement at work. Even more than ‘Millennials’ (born between 1981 and 1996) they are likely to favour job hopping than building a career in a single organisation. Those in ‘Generation X’ (born between 1965 and 1980) tend to value greater autonomy and work-life balance to a greater extent than the ‘Baby Boomers’ (born between World War II and 1964), who value a more structured environment. These varied preferences pose challenges for employers and also point towards benefits of hybrid working (discussed below) to cater for desires for collaboration, autonomy and work-life balance.

More generally, the uncertain and precarious nature of work has led to an increasing amount of instability for younger people who are starting careers. Providing secure jobs at Real Living Wage rates (£9.50/hour outside London or £10.85/hour inside London) helps increase motivation and retention rates for employees. Providing a commitment to Living Hours where staff are provided a minimum number of hours each week further improves job stability and leads to improvements in the health of employees.57 People who tend to work in retail, hospitality, and leisure sectors, such as younger people, women, and those from more deprived areas have significant amounts to gain from working with employers who guarantee a Real Living Wage with Living Hours.58 The importance of good worklife balance is important for all sectors, as the burnout associated with excessive working has led to around half of employees becoming less career-focused following the Covid-19 pandemic.59

52 For further discussion see Taylor, A. (2021) The Future of Work and Training: A provocation for the West Midlands, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

53 Kanders, K., Djumalieva, J. Sleeman, C. and Orlik, J. (2020). Mapping Career Causeways: Supporting workers at risk https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/mapping-career-causeways-supporting-workers-risk/

54 McKinsey (2019) UK Skills Mismatch in 2030, Industrial Strategy Council. https://industrialstrategycouncil.org/sites/default/files/UK%20Skills%20Mismatch%202030%20%20Research%20Paper.pdf

55 Lyons, H., Green, A. and Taylor, A. (2020) Rising to the UK’s Skills Challenges, Industrial Strategy Council. https://industrialstrategycouncil.org/rising-uks-skills-challenges

56 For further discussion see O’Farrell L. (2021) Boomers versus Zoomers? Exploring the myths and reality of how generations think, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

57 For further discussion see Read H. (2021) The ‘New Normal’ and ‘Building Back Better’: Changing City Centre Business Districts, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

58 Living Wage Foundation (2019) Living Hours: Providing Security of Hours Alongside a Real Living Wage https://www.livingwage.org.uk/sites/default/files/Living%20Hours%20Final%20Report%20110619_1.pdf

59 Aviva (2021). Number of UK Workers Planning Career Changes Rises. https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases/2021/04/number-of-uk-workers-planning-career-changesas-a-result-of-pandemic-rises/

Remote and hybrid working

The shock of the Covid-19 pandemic precipitated short-term changes in how, where and whether people worked in the short-term. The key question for the Future Business District in the mediumterm is the extent to which, and for whom, these various changes ‘stick’ and presage a paradigm shift in ways of working, and in turn what this means for the future office and wider business environment. There are other implications – including for mobility, well-being and the urban realm (these are considered in more detail in subsequent sections)

Trends in remote working

An increase in remote working has been evident for several decades, but despite claims about teleworking presaging the ‘death of distance’60, the pace of change has been gradual in the UK until the Covid-19 pandemic: 1.5% of people in employment were working mainly from home in 1981 rising to 4.7% in 2019. This marks a slow detachment of workers from conventional ‘spatially fixed’ workplaces. The first Covid-19 lockdown changed this picture: in April 2020 over 43% of workers nationally were working from home, up from just under 6% in early 2020.61

Not all jobs/ tasks are conducive to being executed remotely. In contrast to ‘anywhere jobs’,62 where the highly qualified (and more highly paid)63 in professional and technical roles, and workers in administrative occupations, are over-represented, there are high-touch public facing roles in the caring and hospitality sectors, as well as in construction, infrastructure, manufacturing sectors and many maintenance tasks that cannot be can be done remotely.

While remote working is applicable for detailed and asynchronous tasks and those involving limited responsibility, it is less well-suited for onboarding new colleagues, organising new projects and developing new collaborations, where face-to-face contact helps build social networks and social capital, corporate behaviours and trust-based relationships. This suggests (even without taking account of practical considerations such as whether workers have a suitable base from which to work remotely) that for many jobs previously undertaken in central business district offices, future working patterns will be ‘hybrid’ – working partly in an office and partly remotely. The ‘forced experiment’ has shown it is possible for many to work effectively and productively remotely (at least for some of the time), with some reaping benefits of work-life balance.64

Evidence shows that a substantial majority of employees who worked at home during lockdown want to continue working at home in some capacity in the future.65 Preliminary analysis of findings of 3,140 responses (two-thirds of whom were females and 72% who were in non-managerial/supervisory positions) from a UK-wide survey of office workers working from home during the Covid-19 pandemic show that the main reasons for wanting to continue working from home were not having the hassle or expense of travelling to work (cited by 88% and 75% of respondents, respectively) and that working

60 Cairncross, F. (1997). The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Will Change Our Lives Harvard Business School.

61 Felstead, A. and Reuschke, D. (2020) Homeworking in the UK: before and during the 2020 lockdown. Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research.

62 Kakkad, J., Palmou, C., Britto, D. and Browne, J. (2021) Anywhere Jobs: Reshaping the Geography of Work, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, London. https://institute.global/policy/anywhere-jobs-reshapinggeography-work

63 Rodriguez, J. (2020) Covid-19 and the Welsh economy: working from home, Wales Fiscal Analysis, Cardiff University.

64 London First, EY (2021) Renew London: Hybrid Working. https://www.londonfirst.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2021-06/EYFutureOfWork.pdf

65 Felstead A. and Reuschke D. (2020) op cit.

from home gives more flexibility (mentioned by 71% of respondents).66 This desire amongst a substantial number of employees to continue working from home (at least to some extent) is in tandem with intentions of approximately three-quarters of employers to increase remote working from home following the Covid-19 pandemic,67 indicating that new working conventions have become socially accepted Indeed, a YouGov survey for the BBC in September 202168 showed that 79% of senior business leaders and 70% of the general public surveyed considered that it was unlikely that people would return to the office at the same rate as before the pandemic.

Implications: the rise of hybrid working

The swift acceleration and extensiveness of the take-up of digital tools during the ‘forced experiment’ of digital working has shown it is possible for many to work effectively and productively remotely (at least for some of the time), so reaping benefits of work-life balance in many instances.69. This experience will undoubtedly have an important legacy for people and places. The key question is what form that legacy will take. At the time of writing in late summer 2021 it is probably too early to say, but it seems reasonable to assume that for many jobs previously undertaken in central business district offices, future working patterns will be ‘hybrid’ – working partly in an office and partly remotely. A survey of 321 senior representatives of businesses across the UK indicated that 93% of firms planned to adopt hybrid working models, citing employee preference (and here it is notable that a survey of office workers working from home found that 78% stated a preference for working in the office two days per week or less70) and well-being as key drivers. Three-quarters expected to have such models underway by the end of 2021.71 The successful implementation of hybrid working models requires good management as workers and businesses adapt.

72

Evidence suggests that working from home does not necessarily have large negative impacts on productivity albeit the picture varies by sector. Results from a working at home experiment in 2013 amongst call centre employees at a Chinese travel agency, revealed a 13% performance increase amongst those working from home.73 But those selected to take part in this experiment had home environments conducive to home working Conversely, data from the ONS Business Insights and Conditions Survey suggests that permanent remote working is associated with a perceived decrease in productivity albeit there are variations by sector.74 What seems clear from a review of the evidence is that the advantages and disadvantages of home-based/ remote working intersect with social

66 Taylor, P., Scholarios, D. and Howcroft, D. (2021) Covid-19 and Working from Home Survey: Preliminary Findings http://www.stuc.org.uk/files/Policy/Research-papers/WFH_Preliminary%20Findings.pdf

67 Institute of Directors (2020) Home-working here to stay, new IoD figures suggest, 5 October https://www.iod.com/news/news/articles/Home-working-here-to-stay-new-IoD-figures-suggest

68 Jones, L. and Wearn, R. (2021) Most workers do not expect full-time office return, survey says, BBC, 16 September. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-58559179

69 London First, EY (2021) Renew London: Hybrid Working. https://www.londonfirst.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2021-06/EYFutureOfWork.pdf

70 Taylor, P. et al. (2021) op cit.

71 CBI Economics (2021) The revolution of work: A survey of the world of work post-COVID-19. https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/7029/12680_cbi-economics_nexus_report_web.pdf

72 Bajorek, Z. (2021) Why ‘i-deals’ may not be idyllic for managing hybrid work, Institute for Employment Studies. 23 August. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/news/why-%E2%80%98i-deals%E2%80%99-maynot-be-idyllic-managing-hybrid-work

73 Bloom, N. (2020) ‘Stanford research provides a snapshot of a new working from home economy’, Stanford News, 29 June.

74 Haskel, J. (2021) ‘What is the future of working from home?’, Economics Observatory.

experiences and life circumstances.75 Analysis from 20 countries shows that more than a fifth of the workforce could work remotely three to five days a week as effectively as they could if working from an office, a proportion considerably greater than before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.76

But what is possible is not necessarily desirable or achievable in practice. Virtual interaction is not a full substitute for all face-to-face interaction where it is easier to pick up visual cues using facial expressions and body language, which also help in developing trust-based relationships. In particular, subtle and serendipitous exchanges (so-called ‘water cooler’ moments) cannot be replicated in online meetings,77 which tend to accentuate interaction with colleagues and others with whom there are pre-existing strong ties, rather than enabling mobilisation of the ‘strength of weak ties’78 shown in the socio-economic literature to foster new opportunities. An analysis of data on virtual interaction of over 61,000 Microsoft employees in the first six months of 2020 showed that remote working across the firm caused the collaboration of network of workers to become more static and siloed. The fact that asynchronous communication increased while synchronous communication decreased suggests that the acquisition of sharing of new information is more difficult in a virtual context.79 So, while virtual interaction may be a reasonable substitute for small meetings with known individuals with whom a worker has a pre-existing relationship, it is more limited where individual relationships are weaker, for integrating new colleagues and building new business relationships with partners and clients (activities which become more important as time elapses) and for other collaborative and creative activities where tacit knowledge is at a premium.80 Aside from the business advantages of face-to-face interaction in an office environment, there is also evidence from workers that they miss social interaction in the workplace.81

It appears likely on the basis of available evidence that working from home will fall relative to the levels seen during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK, but that it will be more common than before the pandemic, with most firms expecting and allowing workers to work from home two days out of five.82 These trends suggest that the hybrid working of the future will incorporate a combination of lifestyle choices, new working norms and the potential for reduced costs amongst employers. Ceteris paribus this will lead to a decrease in demand for retail, hospitality and cleaning services in city centre business districts83 (i.e. the types of jobs that traditionally employ young people and those with lower qualifications).

75 Reuschke, D. and Ekinsmyth, C. (2021) ‘New spatialities of work in the city’, Urban Studies 58(11), pp. 2177–2187.

76 Lund, S., Madgavkar, A., Manyika, J and Smit, S. (2020). What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries. McKinsey & Company [Online]: https://www.mckinsey.com/featuredinsights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries

77 Duranton, G., and Puga, D. (2020) ‘The economics of urban density’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), pp. 3–26. doi:10.1257/jep.34.3

78 Granovetter, M.S. (1973) ‘The strength of weak ties’, American Journal of Sociology, 78(6): pp. 1360-1380.

79 Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Weston, J., Joyce, C., Shah, N., Sherman, K., Hecht, B. and Teevan, J. (2021) ‘The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers’, Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

80 Florida, R. et al. (2021) op cit.

81 Taylor, P. et al. (2021) op cit.

82 Haskel, J. (2021) op cit

83 Arup, Gerald Eve, LSE (2021) The Economic Future of the Central Activity Zone (CAZ) Phase 2 Final Report: Scenario development, model findings and policy recommendations, Report to the Greater London Authority. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/caz_economic_future_phase_2_report.pdf

How offices are used

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic commercial property sector trends pointed towards enhanced emphasis on health and safety issues, space for activity-based working, flexibility and improved space utilisation. Sustainability, smart buildings and developments in the digital workplace were already reshaping the nature of offices. The Covid-19 crisis seems likely to accentuate pre-existing trends so that in future the primary use of the office will be as a multifunctional, flexible hub for meaningful interaction (i.e. connecting, collaborating, brainstorming and socialising with colleagues and customers), rather than a mono-purpose ‘get-things done’ place.84

Office design is changing to accommodate the new balance of functions, with collaboration, creativity and culture taking precedence. These trends culminate in a ‘flight to quality’ in office space 85

Health, well-being, mobility and the built environment

The economy, society, health, well-being and urban form are all interconnected. The pandemic has accentuated pressure for more health-oriented urban design. This is a feature of previous health scares: “we design and inhabit physical space [that] has been a primary defence against epidemics” 86 An example is the movement that emerged in the 19th century that sought changes in bathroom design after the cholera outbreak in London.87 The result was changes in the design of internal spaces of housing and where there were causes of disease spread 88 The Covid-19 pandemic has been a health crisis first and foremost. There are remarkable similarities with the number of cases, deaths, and economic impacts resulting from Covid-19; and economic deprivation, pre-pandemic life expectancy, and social inequalities.89 Hence, it is imperative that the future city centre plays a leading role in improving health and wellbeing outcomes for its citizens and users.

It is reasonable to expect that the city centre ecosystem and its built environment will be substantially affected by the accelerated trends caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. With a greater demand for green spaces, more active travel, fewer retail outlets and greater opportunity for conversion to alternative uses such as housing, the city centre is likely to change substantially. These changes, unlike changes to collaboration workspaces within buildings, will be visible to all that interact with the city centre.

Promoting health, well-being and sustainable growth

The National Design Guide,90 published by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), is part of a wider appetite in government to develop a revised approach to planning and urban design. Alongside the National Planning Policy Framework, it underscores the thought in government that creating high quality buildings and places is a crucial part of what urban development and the planning process should achieve. The policy is packaged with the National Design Guide, and the National Model Design Code and Guidance Notes for Design Codes, which detail

84 Arup (2020) Future of offices: in a post-pandemic world, Arup.

85 Arup (2021) the https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/future_ of_the_central_activities_zone.pdf

86 Budds, D. (2020) Design in the age of pandemics available at: Curbed website: https://www.curbed.com/2020/3/17/21178962/design-pandemics-coronavirus-quarantine

87 Berk, B. (2020), Life after COVID-19: How interior design will change, https://bobbyberk.com/life-after-covid19-how-interior-design-will-change/

88 Tomes, N. (1999) The gospel of germs: Men, women, and the microbe in American life, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

89 Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J. and Matthews, F., (2020) ‘The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74, 964-968.

90 MHCLG (2021) National Design Code, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/962113/ National_design_guide.pdf

how well-designed places can be beautiful, healthy, greener, and more enduring, with practical examples and support for relevant bodies to develop concise and sustainable localised design codes.

The desire for more green spaces and the fusion of the natural and urban realm, with greater inclusivity and democratisation of place, alongside a more beautiful and interactive environment, were mentioned in consultations with businesses and stakeholders (discussed later).

Repurposing shops to homes

The UK is experiencing a substantial housing crisis. The ratio of homes to households is tighter in the UK than most peer European countries (0.99 compared to the European average of 1.12) 91 As a result of this reduced availability, the UK is suffering a housing affordability crisis. Average house prices in the UK rose by 378% between 1970 and 2015 compared with 94% in the OECD.92 Comparatively, there are too many shops. Analysis suggests that the UK currently has 158 million square feet of vacant retail space, which translates to nearly 13% of retail units, with some UK regions experiencing a 17% surplus of retail spaces.93 The trend in online shopping (outlined above) has fuelled this, but this trend has been substantially accelerated as a result of Covid-19, with 33% of all retail shopping done online in 2020. If this trend, or a similar share of online sales continues, vacant retail units will become an even more familiar appearance across the city centre. Trends suggest that the space retail requires will be condensed post the Covid-19 pandemic

Converting these vacant units into attractive homes that enhance the urban environment and provide housing to people will be a positive way to ensure the city centre remains relevant. Create Streets, in their Permitting Beauty94 report, advocate for councils and neighbourhood forums to make use of the government’s new Model National Design Code. This Design Code could be embedded in local policy through additional planning documents or in local plans.

Fluid and flexible modifications of neighbourhood streetscapes: the tactical urbanism trend Aria Group95 architects have proposed a re-designed approach to the streetscape that enables scalable solutions to the pandemic, with fluid and flexible modifications of a neighbourhood streetscape. The designs allow restaurants and bars to stay open whilst maintaining safety and hygiene measures. They suggest that shop fronts are likely to include operable designs which incorporate larger windows for ventilation and street markers for queuing. The need for social distancing may stay beyond legal mandates, with restaurant seating providing different shade options and solar-powered heat/light, within 1m+ floor markings. There is scope for these modifications to remain in place following the Covid-19 pandemic and for greater fluidity and flexibility in urban streetscapes generally.

These types of initiatives are part of a more general global trend towards ‘tactical urbanism’: “an approach to neighbourhood building and activation using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies”.96 Tactical urbanism offers three key opportunities: it is a tool for low-cost prototyping, envisioning a different future and reducing inequalities in access to shaping city space

91 Create Streets (2021) Permitting Beauty, https://www.createstreets.com/wpcontent/uploads/2021/03/Permitting-beauty_online.pdf

92 OECD (2021) Housing Prices, https://data.oecd.org/price/housing-prices.htm

93 Savills analysis, found in Create Streets (2021) op cit.

94 Create Streets (2021) op cit.

95 Aria Group (2020) Pandemic Design: A New City Streetscape, https://www.ariainc.com/pandemic-design-forretail-and-hospitality/

96 Lydon, M. and Garcia, A. (2015) Tactical urbanism, Island Press, Washington.

through increasing inclusivity. It is appealing for future business districts/ city centres in the it can be utilised at a range of scales, from the individual, to groups and organisations and local government.97

Creative fusion of the natural and built urban environment

As a result of previous pandemics there has historically been a revival in merging green spaces with the urban realm. English thinker, Ebenezer Howard98 proposed and later developed a Garden City that sought to address the welfare of industrial city residents that were suffering the negative consequences of large urban and industrialised cities. Similarly, the French modernist architecturbanist Le Corbusier proposed a tower-in-the-park skyscraper as a way of offsetting some of the problems with urbanisation. Currently, there is increasing recognition of the importance of urban greenspace as a resource for health.99

Extreme weather patterns arising from climate change point to more frequent substantial bouts of rain, threatening the city’s vitality with street flooding. There are currently durable concepts of urbanism that fuse the natural environment with the urban one, that propose practical and readily available solutions to the increasing desire for green spaces in the built-environment. As the examples of street furniture below illustrate, there are various ways of greening the urban environment. There is also scope to use smart technology here, as in the case of solar powered irrigation and an app for a living pillar, converting a street lamp in to something that successfully introduces biodiversity in urban places.

Reclaiming the street from the car to the pedestrian, and placing greenery and planters with seating and hospitality spill-over facilities (in Oxford)

Mobility: public and active transport

‘Bee bus stops’, with a ‘living roof’, which are topped with a mix of wildflowers and sedum plants, to support biodiversity100

It is essential to rethink the design of transport to improve the wellbeing of people, while providing access to important activities. It is notable here that during the Covid-19 pandemic, government restrictions to travel disproportionately affected more vulnerable people.

97 For further discussion see Parkin, V. (2021) Tactical urbanism: a global trend key to ‘building back better’ across West Midlands cities following COVID-19? Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

98 Howard, E. (1898) To-Morrow: A peaceful path to real reform/garden cities of tomorrow, Swan Sonnenschein, London

99 For further discussion see McDermott, R. (2021) Health and Urban Greenspace Post Covid, Provocation Paper, City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

100 https://www.leicestermercury.co.uk/news/leicester-news/bee-friendly-bus-stops-topped-5462984

101 https://www.scotscape.co.uk/projects/living-pillars-southend-sea-council

Living pillars – smart technology and greenery101

Lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic led to a reduction in traffic congestion, improved air quality and growth in walking and cycling due to the lockdown restrictions. Longer-term, besides their health benefits, walking and cycling can have positive effects on the central business districts. Evaluations conducted prior to the Covid-19 pandemic pointed to economic and social value from pedestrianisation.102 However, when considering active transport, there is still an imperative to take account of the requirements for people with disabilities. Investing in infrastructure that encourages greater walking and cycling needs to consider the requirements of people with disabilities to encourage greater accessibility for self-sustained transport.

Alongside the promotion of more local travel, the future business district/ city centre requires people travelling in from the suburbs and further afield.103 Crowded peak time transport may not instil confidence in commuting following a pandemic. Spreading out peak times by offering flexible tickets, and requiring masks to be mandatory at peak times, are practical opportunities to instil confidence in the use of public transport in the future.104 The aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, new ways of working and changes in attitudes in principle provide an opportunity to integrate public and other forms of transport to improve mobility. Models with state or municipal control can be best placed to pull together the integrated transport system with fully devolved funding.105

102 Living Streets (2018) The Pedestrian Pound–The business case for better streets and places https://www.livingstreets.org.uk/media/3890/pedestrian-pound-2018.pdf

103 For further discussion see Cepeda-Zorrilla, M. (2021) Adapting to Future Mobilities, Provocation Paper, CityREDI, University of Birmingham.

104 Gkiotsalitis, K. and Cats, O. (2020) ‘Public transport planning adaption under the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: literature review of research needs and directions’, Transport Reviews 41(3), 374-392.

105 Gutierrez, A., Miravet, D. and Domenech, A. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and urban public transport services: emerging challenges and research agenda’, Cities and Health, DOI:10.1080/23748834.2020.1804291

3. MEGATRENDS WORKSHOPS

Overview

A megatrend is a major movement, pattern or trend emerging that has a transformative impact on business, economy, society, cultures and personal lives. Examples include technological developments, the move to Net Zero and demographic changes such as population ageing.

This section outlines the findings from seven virtual workshops held in February 2021 bringing together stakeholders and academics from the West Midlands to discuss megatrends Each workshop lasted 90 minutes and involved around 20-23 participants. Each workshop explored a particular topic – (1) mobilities, (2) health and well-being, (3) hybrid workplaces and the future of work, (4) business models and operations, (5) attitudes and values, (6) changing functions and functioning of places, (7) business districts.

The workshops proceeded using the same format and were facilitated by Future Agenda:106

1. Workshop attendees were asked to post digitally their initial views on the biggest shift looking ahead to 2030 relating to the workshop topic. Concurrently, other attendees could then provide support for particular views by registering a ‘like’ for a particular comment.

2. The workshop facilitator selected comments from the composite list of views and invited individuals who proposed the view to explain why they considered the shift important, so stimulating wider discussion.

3. A member of the research team presented twelve pre-prepared trends pointing the way towards possible future scenarios for 2030. It was noted that these did not encompass all possible trends, but they highlighted a range of possible futures.

4. A virtual poll was conducted with workshop participants asked to identify which five of these twelve trends (plus any other key trends identified from the first stage of the workshop and receiving substantial support) would have the greatest possible impact in the UK to 2030. As votes were posted the trends were ranked in order of those receiving the most support.

5. There was a short discussion on the results of the poll, with the facilitator inviting advocates of particular trends to indicate why they considered that trend was important and then inviting wider comments and observations on the trends emerging as having the greatest possible impact.

6. A virtual poll was conducted was conducted with workshop participants asked to identify which three of the trends used as the basis of the poll in step 4 above would see most innovation happening in the period to 2030. As votes were posted the trends were ranked in order of those receiving the most support.

7. There was a short discussion on the results of the poll – and in most instances it was noted that the same trends were not necessarily identified for innovation (in step 6) as for impact (in step 4).

8. Participants were divided into four breakout groups and were asked to select one of the top threefive trends from the ‘innovation’ poll in step 6 and then discuss their manifestation over the next 10 years in comparison with the current situation, prior to exploring specific implications for the West Midlands (noting down key points on a template).

9. A brief report back in plenary from each of the breakout discussions, with an opportunity for quick questions and comments.

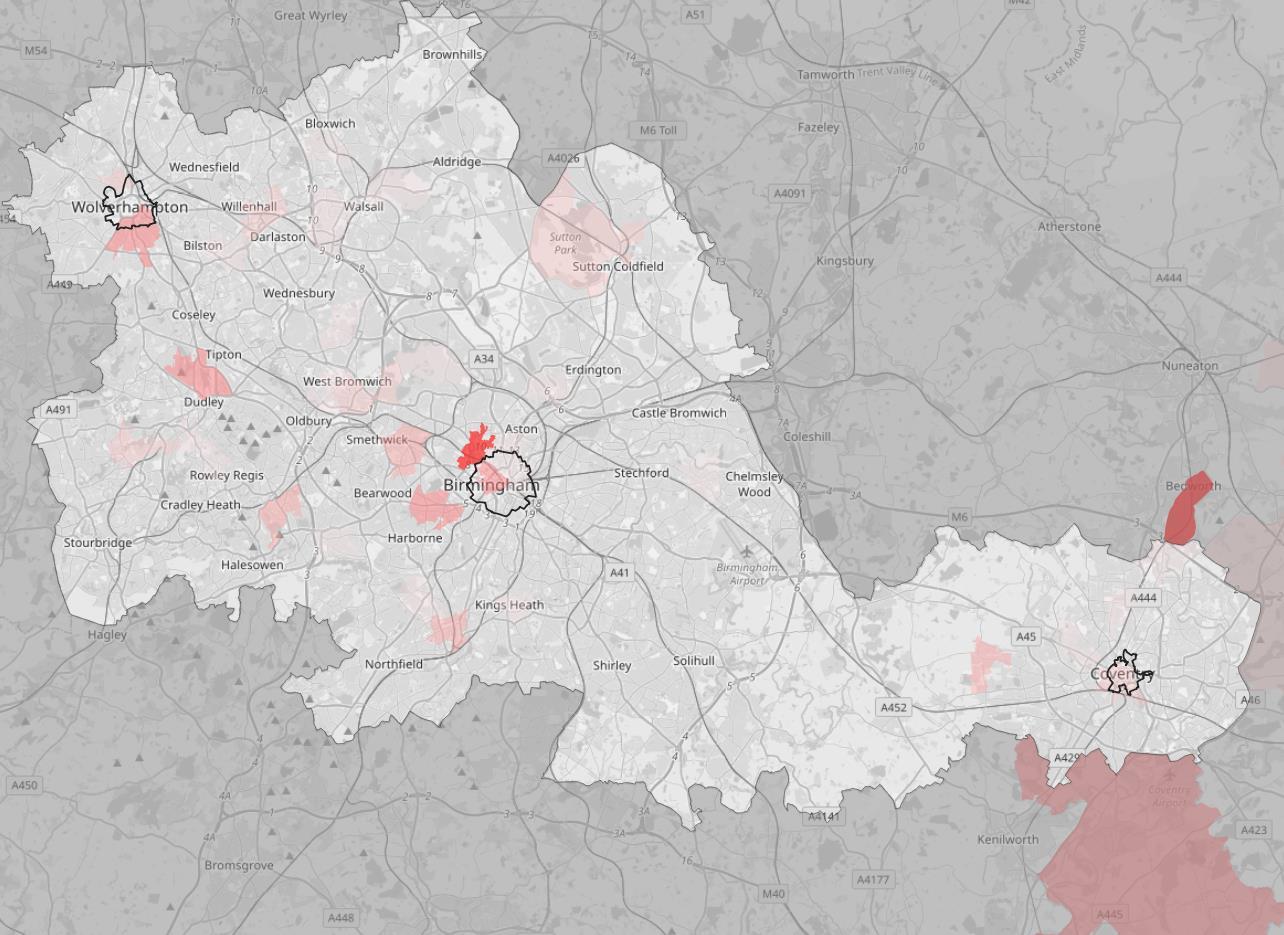

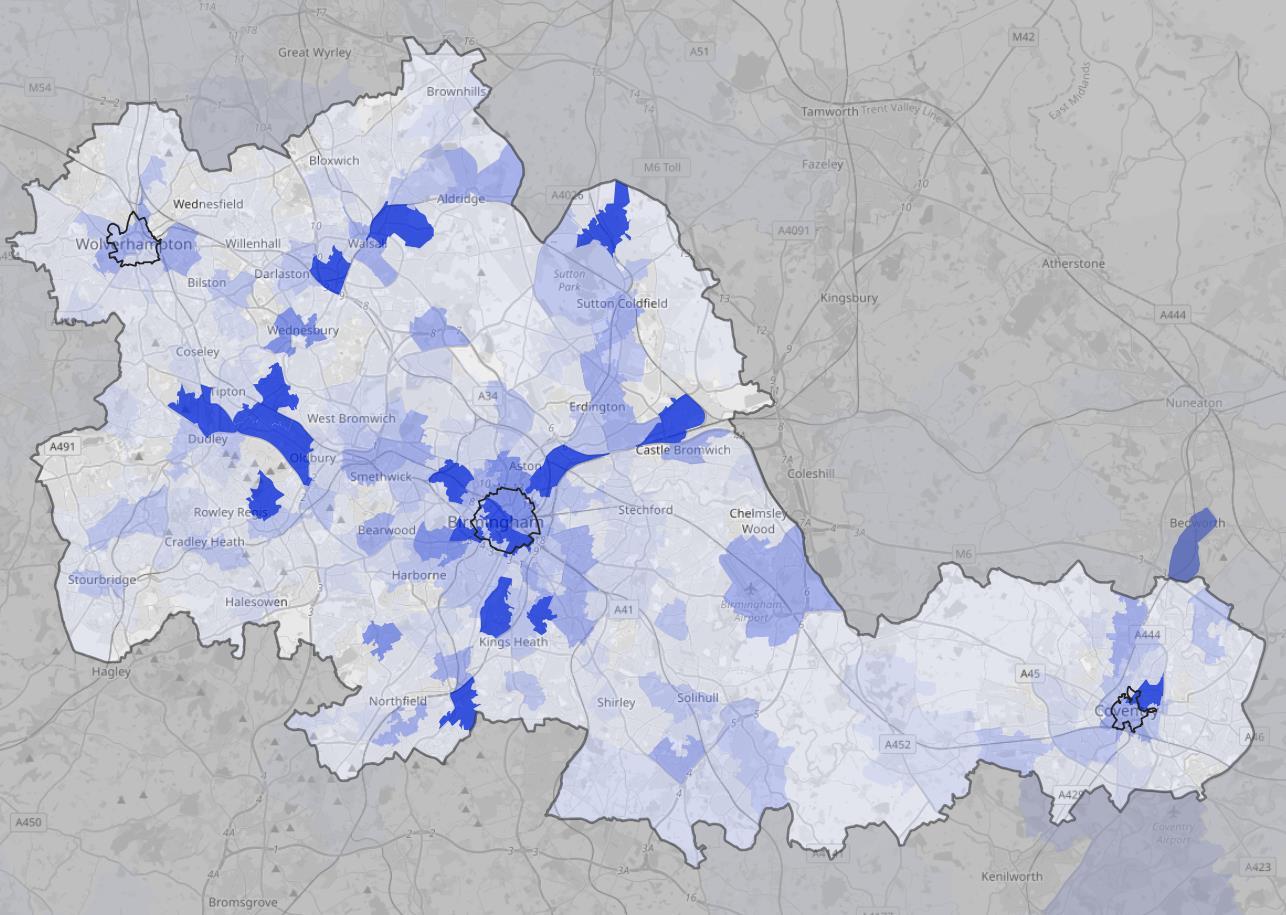

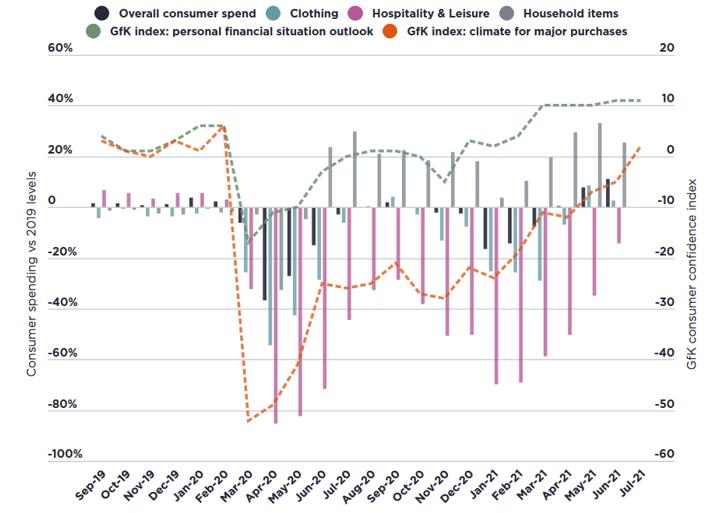

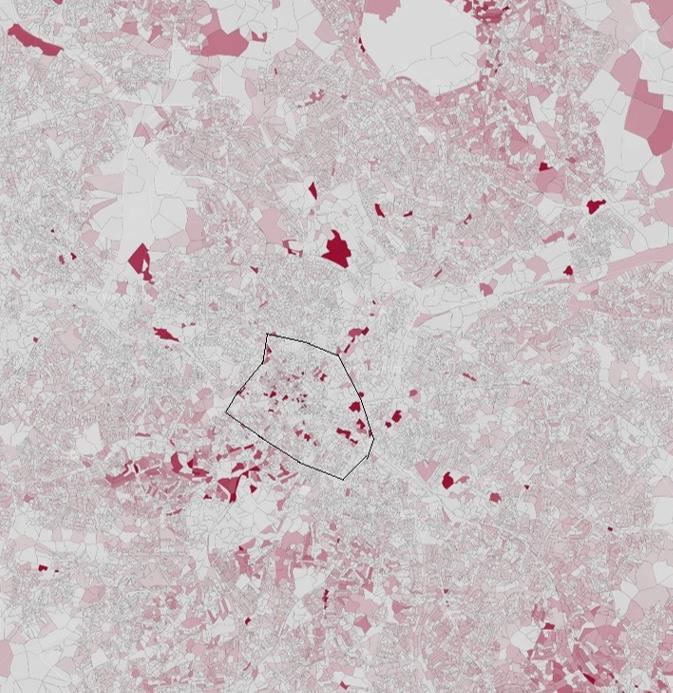

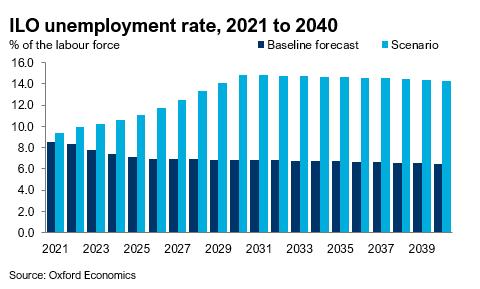

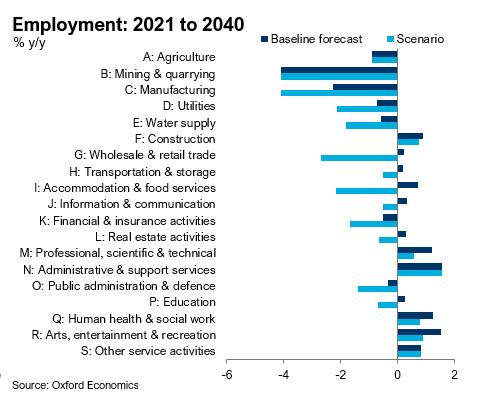

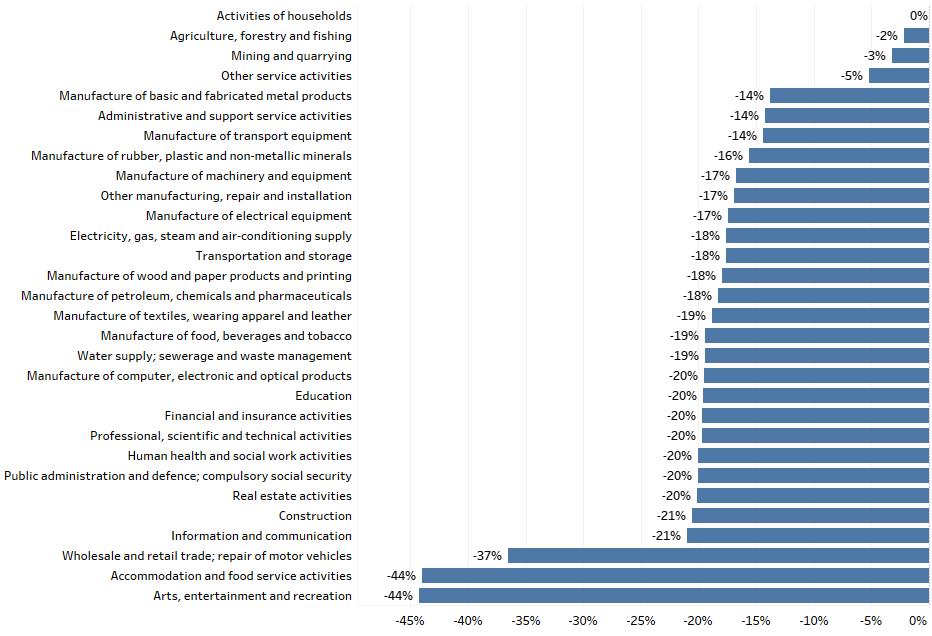

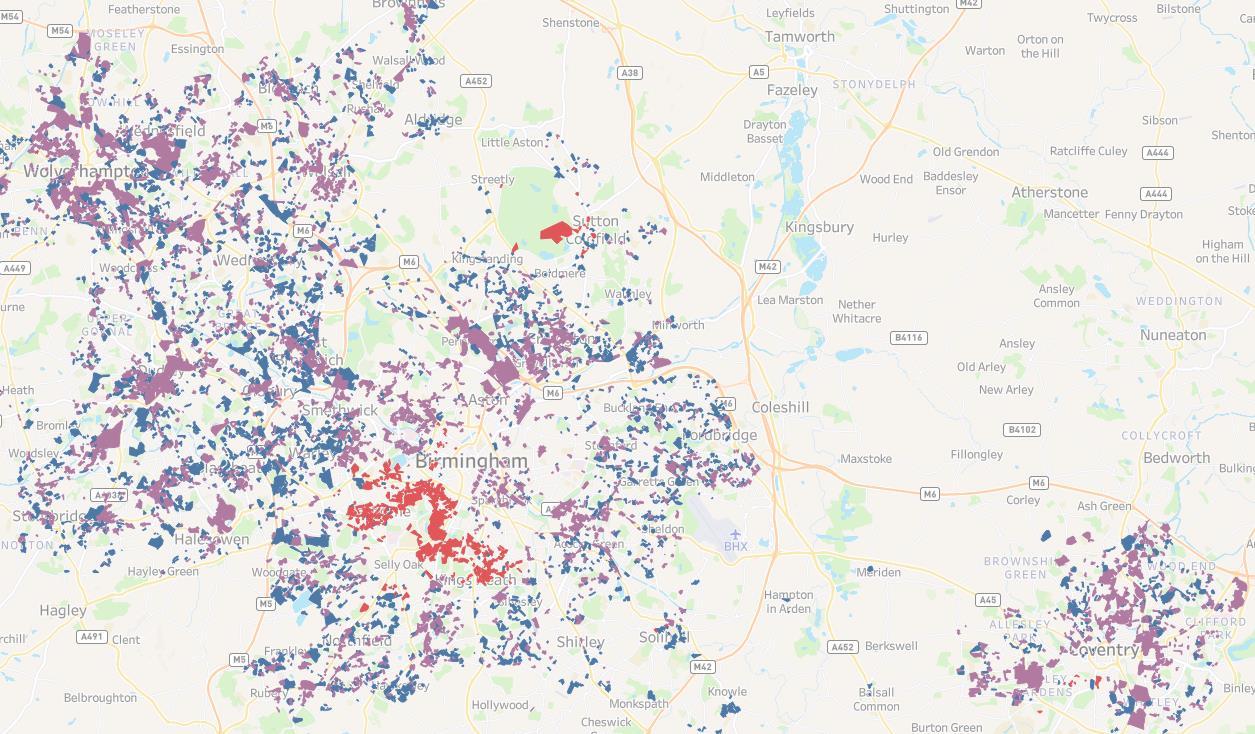

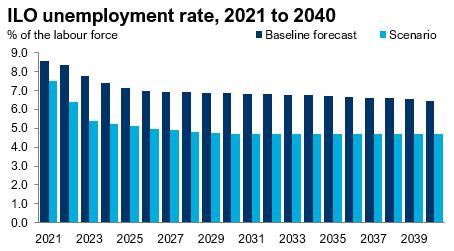

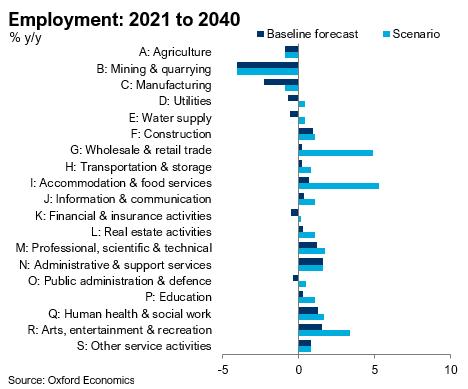

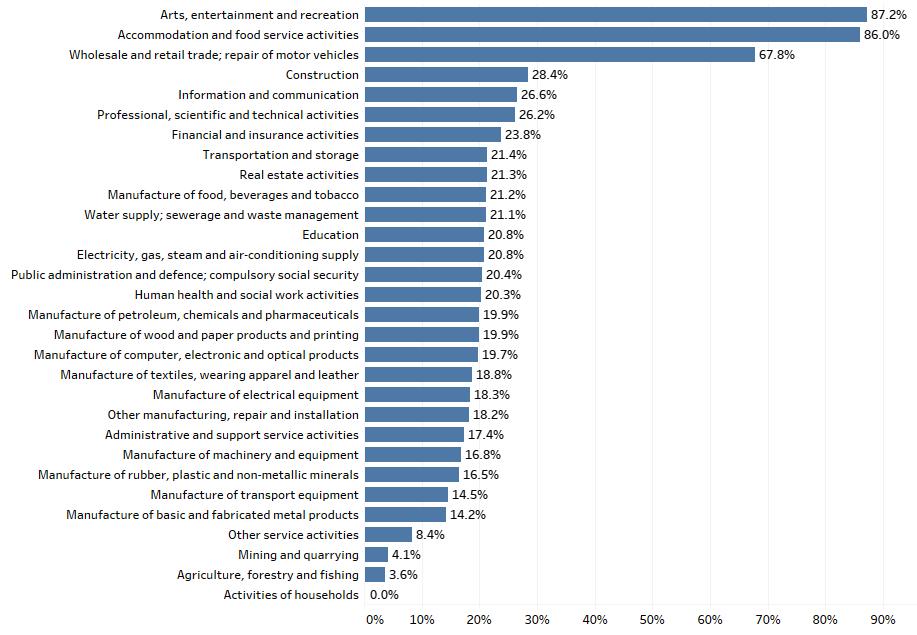

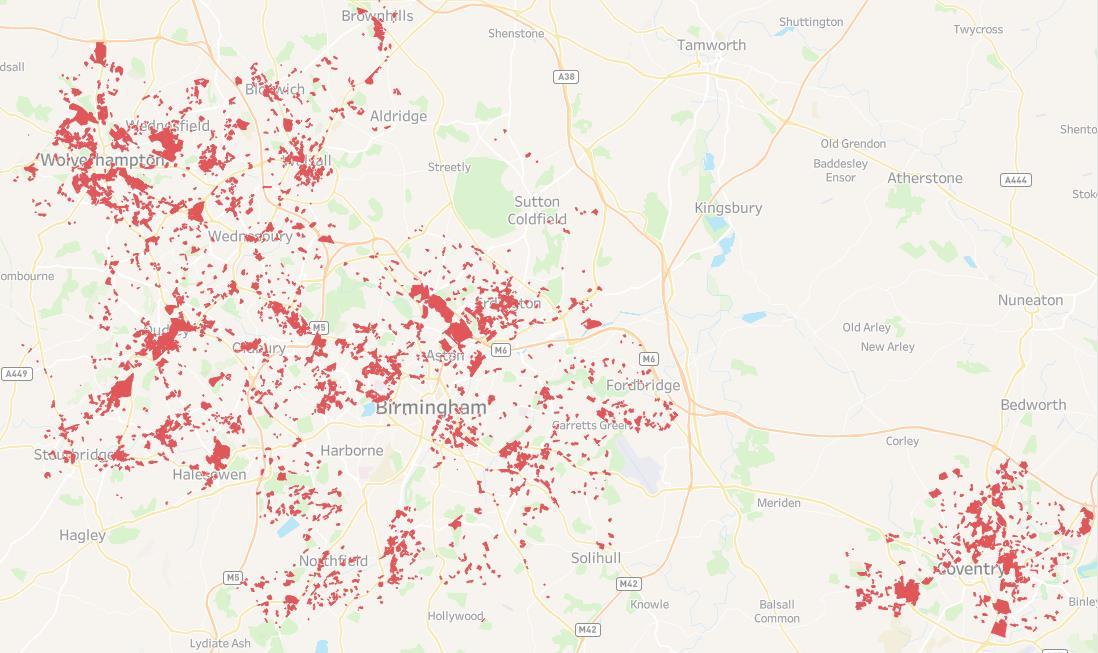

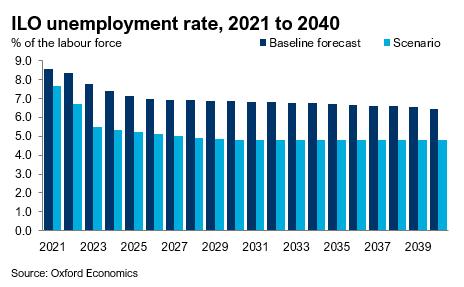

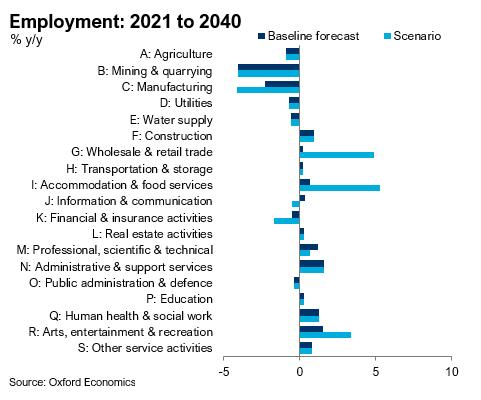

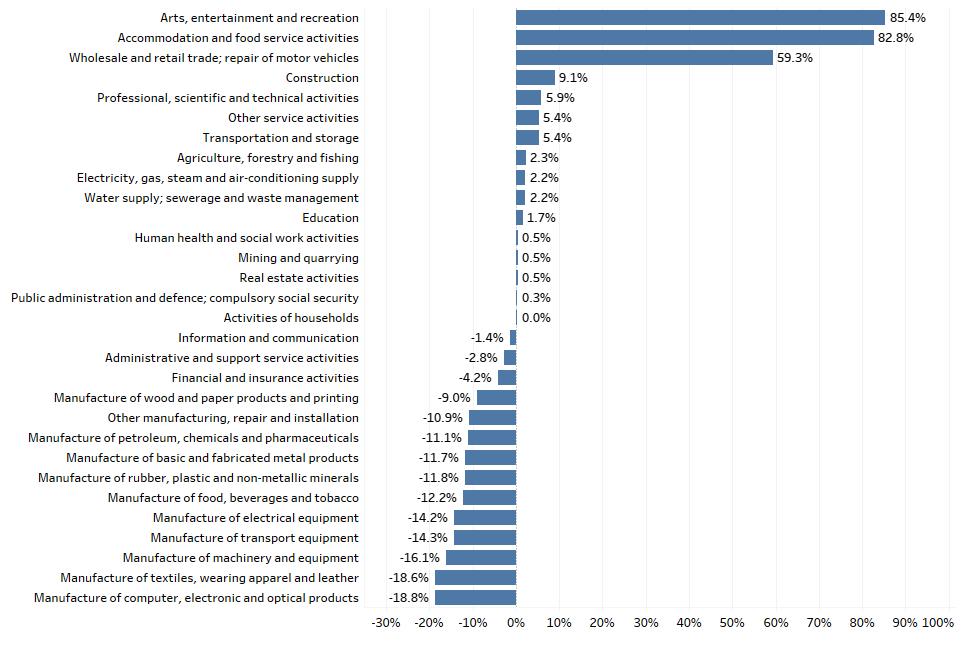

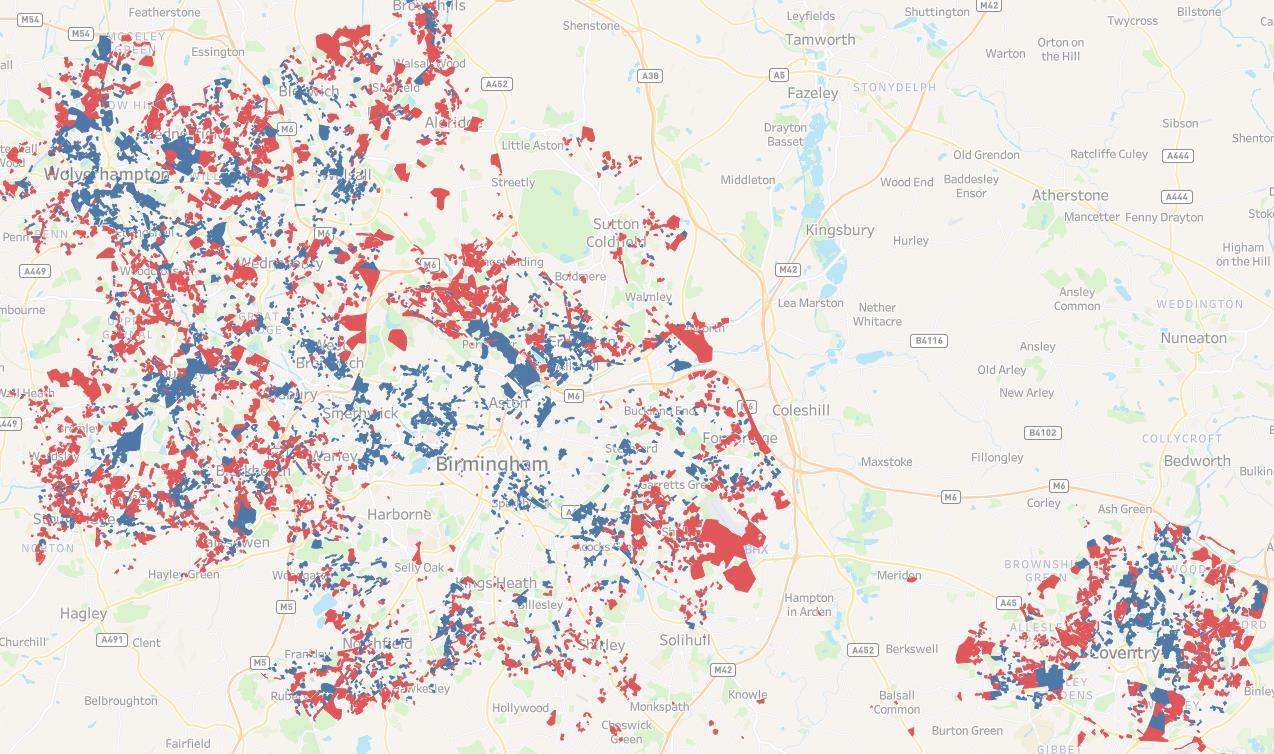

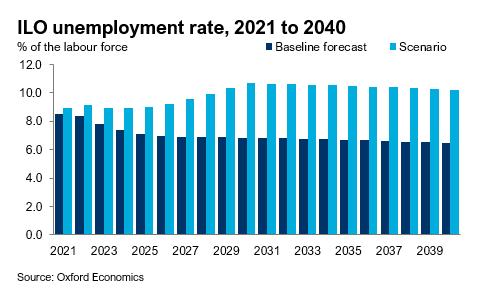

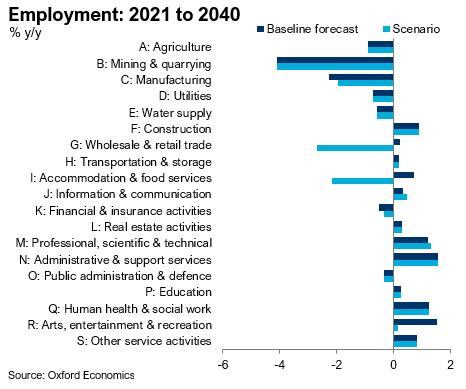

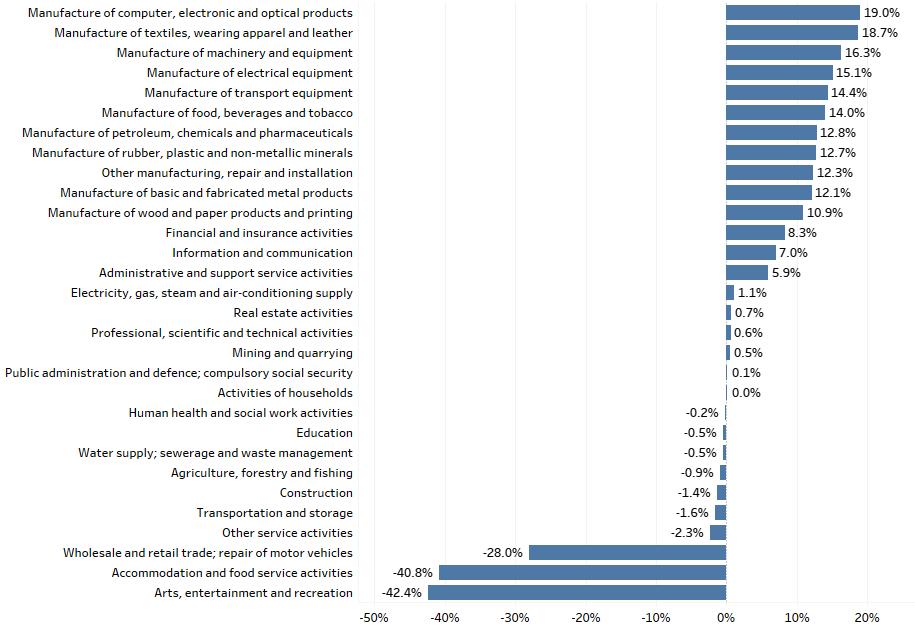

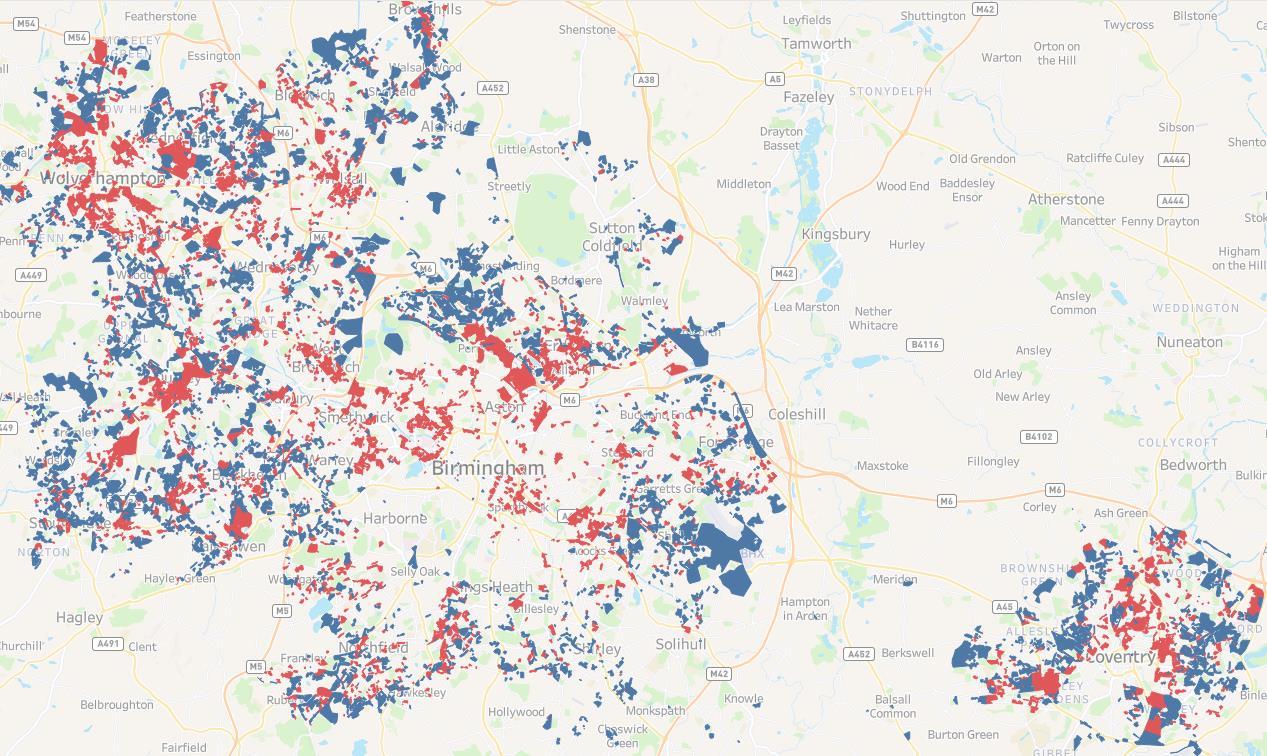

10. Participants were invited to post a word or phrase capturing the key future insight from the discussion pertaining to the topic of the workshop and then invited to explain their selection.