There are around 1900 active volcanoes on the Earth. Some erupt almost continuously whereas others may go for hundreds of years between eruptions. Volcanoes can cause great destruction and loss of life, but they can also bring benefits to those who live in their shadow. Volcanoes vary in the type of material produced in an eruption and the shape of the resulting mountains. This chapter will explore volcanoes in several locations, and will consider the nature of risk and the benefits of living in tectonically active areas.

This chapter has a particular focus on Iceland which is now experiencing a period of active volcanism close to its capital city that is beginning to have negative impacts on important infrastructure.

The chapter finishes by exploring some of the ways in which communities lying close to active volcanoes predict, plan and prepare for future eruptions to mitigate the impacts, while recognising the risks and measuring them against the potential benefits of such locations.

In this chapter, students will learn about:

• using a range of mapping tools to investigate different types of volcanoes and their global location along plate boundaries

• the idea of risk and how to communicate this in different ways

• creating and interpreting infographics

• drawing field sketches.

By the end of this chapter, students will understand:

• that volcanoes can be classified in different ways

• why volcanoes occur where they do, and the link with tectonic plates and the boundaries between them

• the different impacts that eruptions can have on human activity, both positive and negative, and how those might be measured, and mitigated

• that volcanoes can bring benefits as well as cause problems

• why people live alongside volcanoes despite the risks they pose.

National Curriculum for England

• Plate tectonics

• International development

• Population

• Geographic Information Systems

Cambridge Lower Secondary Humanities

• LP.01

• PF.04

Coverage of volcanic eruptions in the media often features lava flowing rapidly away from the vent or fissure, or lava fountains being thrown upwards. The variety of eruptions makes every volcano unique, but there is a sense that they are all conical peaks with hot lava emerging from the ground. Students should be shown images of a variety of volcanoes in addition to those used in the Student’s Book. There is a directory of volcanoes produced as part of the Global Volcanism Program which could be used to identify the nearest volcano to your location.

1 Why do some volcanic eruptions cause more destruction than others?

Students may think that there is not a volcano near them, but geological maps of your area may indicate igneous rocks, produced by volcanic activity. This may reveal that extinct volcanoes are found closer to them than students might imagine. One persistent phrase is “natural disasters”. The “No Natural Disasters” movement suggests that there is no such thing. This is because no disaster exists that is not made worse or less impactful through decisions taken by people. This may include decisions taken by those living close to active volcanoes to farm there despite the obvious risks.

The final misconception is that volcanoes always cause death and destruction. Technology can now give some prior warning of the need for evacuation, and many volcanoes erupt in such a way that they do not cause problems and people can live alongside them.

Students are likely to have been introduced to volcanoes during the primary phase of their education, although the level of detail will vary. Some students will be familiar with the idea of tectonic plates and how they move (this is covered in detail in Chapter 2, Lesson 2). They may also know about geothermal energy as a source of renewable energy.

Chapter 2, Lesson 2 looks at how the movement of tectonic plates shapes the land and causes earthquakes. Some volcanic activity is linked to earthquakes, which are tectonic hazards and may trigger volcanic eruptions or show signs that they are about to happen.

It is unlikely that you will be able to visit a volcano, although you may have the opportunity for an overseas trip to locations such as Iceland, Sicily or Naples (to visit locations such as Pompeii). A volcano would need suitable risk assessment before being approached, but this is likely to be as part of an organised excursion with a company, who would have risk assessments in place.

You may be able to visit a museum that has details of previous eruptions or artefacts from locations which have been affected by them. The Natural History Museum in London has an earth science exhibition telling a compelling story of tectonic activity.

The location of your school will determine whether there are any local opportunities to see evidence of volcanic activity. However, you could create papier mâché volcanoes which can be made to “erupt” using various chemical reactions, for example, baking soda and vinegar. You could hold a competition to create the most realistic volcano shape. There may be some rocks in the local area that are volcanic; for example, the setts in speed bumps in city centres tend to be granite so that they can withstand the weight of vehicles.

This lesson explains what volcanoes are, and why they are found in locations linked to the boundaries between the world’s tectonic plates. The distribution of volcanoes is not even, and they are often found in the most densely populated parts of the world, despite the risks they pose. This suggests that their existence also brings benefits to those who live near them.

Some students may not think that there are any volcanoes nearby, but you may be able to prove them wrong. Students may also have a view that all volcanic eruptions are similar, with molten lava flowing out of a hole in the ground at the top of a conical peak.

Volcanic activity is not always treated accurately in films. Once the chapter has been taught, you could show students clips from films such as Dante’s Peak, which has several scientific errors. Some fiction books also overstress the suggestion that volcanoes can be predicted.

Students need to appreciate that volcanic activity tends to lie along tectonic plate boundaries (although not exclusively).

Figure 1.4 in the Student’s Book shows the world’s tectonic plates. Along some of the boundaries between these plates, magma can make its way to the surface more easily. Some of these boundaries lie beneath the ocean, and the accumulated material has made new land in some places, but not others. Volcanoes particularly form along divergent plate boundaries, where plates move apart. When plates move together, volcanoes are not found directly along the plate boundary. This is explored further in Chapter 2, Lesson 2.

It is important for students to understand the difference between magma (below the ground) and lava (above the ground), plus the fact that lava varies in its viscosity (you may want to model this using some treacle or similar substance to show how it spreads out slowly).

Figure 1.4 could be used in different ways, and various websites also exist which show the movement of plates over time. This will be developed further in Chapter 2, Lesson 2.

Use a GIS map to explore the location of the world’s tectonic plates. The mapping company ESRI offers a free online map viewer which can be used to display map layers including tectonic plates. Search “ESRI volcano viewer” to find the map.

Use this map to identify the location of Iceland. The ESRI Living Atlas has plate tectonic layers which can be added to show the location along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

There has been a lot of news coverage of recent volcanic activity. Webcams have been in place on the Reykjanes peninsula for some years and there are recordings of previous eruptions on YouTube which can be viewed to show the nature of the fissure eruptions, with lava fountains followed by lava flows, some of which have damaged or threatened infrastructure, including the Blue Lagoon. Iceland has a range of media sites which keep residents informed of volcanic activity. These include RUV and Reykjavik Grapevine. The Veður site is also very useful.

1 The lesson introduces the idea of what a volcano is, before the various types are described in Lesson 1.2, so a simple definition of a volcano is needed here.

2 The Earth’s crust varies in thickness from around 5 km to 70 km. It is thinnest where oceanic and continental plates meet. Students should reference thickness and density, or chemical content.

3 Various online maps are available. ESRI’s ArcGIS offers a range of maps showing the ridge. An alternative would be to use a physical map from a printed atlas.

4 Locate Iceland in an atlas and look at where it sits in relation to the two tectonic plates to the east and west of the country. Look along to the ridge to see where else there is some land above the surface of the ocean.

5 These are alternative terms from crust and mantle and provide a little more scientific explanation which may be useful for study at the next level after this course.

1 A volcano is a gap in the Earth’s crust – which could be a vent or a fissure – through which material can erupt.

2 Oceanic crust is generally denser and thinner than continental crust. Continental crust is also older and generally made of granite and gneiss with a high silica and aluminium content (SiAl). It is generally between 20 km and 70 km thick

Oceanic crust is newer, as it is being created and destroyed as part of the process of subduction (which is returned to in Chapter 2, Lesson 2). It is typically 5–10 km thick and generally less than 200 million years old (rather than the billions of years of some continental crust).

3 Iceland is the only country that sits on the ridge, but there are several islands belonging to the UK and Norway, including Ascension Island.

4 Iceland is on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, but also has a mantle plume beneath it, providing extra opportunity for lava to reach the surface –this has created the country over millions of years and continues to build it now.

5 Asthenosphere is a term that is often used to appreciate that the division between the mantle and the crust is not a line, but a zone where the heat from the mantle partially melts the lower layer of the crust or lithosphere.

We can classify volcanoes in different ways, including the way in which they erupt. Some volcanic eruptions may be more destructive to property in the vicinity of the volcano, whereas others can have an impact on places a long way from the eruption. Some volcanoes have resulted in thousands of deaths, while others have caused no fatalities. Some produce fast-flowing lava flows, while others throw ash into the upper levels of the atmosphere. Volcanoes vary depending on the viscosity of the magma, how much gas it contains, its chemical composition and how it reaches the surface.

Volcanoes are often classified as being in one of three states:

• extinct

• dormant

• active.

The lesson explains that there are some issues with these terms. They are not always used consistently, and additional words are sometimes used. Dormant volcanoes may still erupt, but some are more likely than others to become active again. Some volcanoes may be actively erupting, such as Stromboli, Italy, or they may be potentially active (dormant). Some are long-term dormant, while others are “restless” and show signs of coming back to life.

The term “stratovolcano” suggests strata (layers). The Student’s Book image of such volcanoes shows neat layers of ash and lava, which is not the case in reality. Eruptions are not as tidy, and thickness and coverage will vary – for example, lava may only flow down one side of the peak in some eruptions, and ash may be blown by the wind.

The Streva Project has made several films looking at the impact of ash fall on communities close to Mount Tungurahua in Ecuador. Between 1999 and 2016, it erupted at least twice a year, with each eruption lasting several days or even weeks. Ash fall is the main hazard affecting people living on the slopes of the volcano. Farmers have found ways to respond to the ash and protect crops and animals. The Streva films show how they managed to adapt and live next to an active volcano, mitigating the impacts and eventually seeing some benefits. You might also find some useful information on the Lava Academy podcast. This is produced by the Lava Show in Reykjavik, Iceland. It provides information about volcanic eruptions in an accessible format, which could be used for homework tasks or listened to in class. Other podcasts are also available. You could ask students to record their own podcasts to explain some aspects of their learning once they have completed this chapter. This is suggested in the “End-of-chapter review” task as one option for how students can present their work.

1 Why do some volcanic eruptions cause more destruction than others?

There are quite a few new terms here, so the use of flash cards or visual representations might help some students to get to grips with them.

Remember that there are thousands of volcanoes, and each is unique. They are not all as conical and symmetrical as Mount Fuji, Japan, or Mount Egmont, New Zealand. Show students a range of images sourced online. A search engine image search for “volcano” will tend to result in conical volcanoes with either huge lava flows or ash clouds. This is not their usual state or shape.

Keep an eye on the news for volcanic eruptions happening as you teach this topic (and also when working on Chapter 2). You could set up a large world map on the classroom wall on which to plot events that happen while teaching this chapter (this is not restricted to volcanic eruptions). This would reinforce the relevance and contemporary nature of the course.

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) is an unusual index because it is open ended. The amount of material needed to be ejected increases between each level of the index. The largest eruption ever recorded was an 8 on this scale.

1 Refer to the section on lava in the Student’s Book. Lava varies in viscosity, which means it will move further away from the vent before it cools and stops moving.

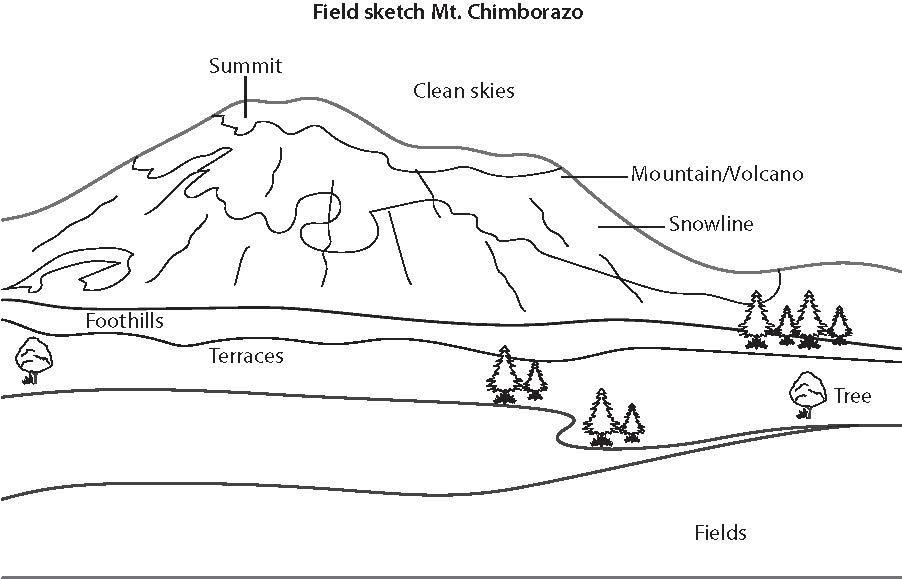

2 Field sketches are a useful skill for students to practise. They are particularly useful when carrying out fieldwork but can also be drawn from images. The example shown in Figure 1.1 is based on the photo of Mount Chimborazo in the Student’s Book.

3 Students should think about the different ways that volcanoes can be classified. When looking at words and their meanings, they should think about other words with similar sounds or letters, for example, for dormant, there is a French verb dormir, or perhaps a dormitory.

4 The VEI is an index, which means it uses specific data values to calculate a score. What are the things about an eruption that can be measured so that different eruptions can be compared?

5 This will require some appropriate internet searches.

1 Viscosity of lava varies according to its chemical composition, particularly the amount of silica it contains, and the amount of gas within it.

More “ runny ” lavas will travel further from the vent before cooling, resulting in the low, wide shape of a shield volcano.

2 See Figure 1.1. This should be based on the image in the Student’s Book, although other cinder cones are also available including Kerid in Iceland and Paricutin in Mexico.

3 Dormancy is a state which means that the volcano has not erupted recently but it is possible that it will erupt again. Dormancy can last thousands of years. People live on the slopes of active volcanoes, so a discussion around what we mean by “safe” could follow. Some are clearly unsafe, for example Merapi in Indonesia, whereas others are safer.

4 The VEI measures the amount of material ejected from an eruption, in the form of lava or pyroclastic material. The daily eruptions of Stromboli would measure 1–3 on this scale. The eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in 2010 was a 4 on the scale, and Mount St Helens in 1980 was a 5.

5 In recent years, there have been a few eruptions which may have reached VEI 6, but these are not confirmed. The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption in Indonesia in January 2022 is the largest that has occurred for some time.

Every volcano is unique. Although students may have a picture in their head of flowing lava from a pointed mountain peak, eruptions may involve gas, lava of differing viscosities, ash and other tephra or lahar. They may last for weeks, or just a few hours. Their impacts may be limited to the immediate area, or they may place ash into the upper atmosphere which encircles the whole globe and cools the Earth. Volcanoes are not predictable in the sense that we can never really know what they will do, but the science around this is improving all the time.

Student misconceptions about the nature of eruptions can be tackled here. They may be used to seeing images of lava flows from volcanoes, such as those on Hawai’i or featured in films or games they may have seen.

Volcanic eruptions, and the material that erupts from them, vary hugely in their nature, and this should be reinforced throughout the teaching of the topic. There is an amusing Pixar short film called Lava (2014) which tells a love story between two volcanoes who erupt in different ways.

If you have access to some rock samples, you could show students what happens to lava after it cools down. Granite and basalt samples would help to show the differences in the crystals that form as the rock cools. They can compare the density of these rocks with sedimentary rocks, and also see their hardness which is caused by the crystals locking together as they cool.

You can learn how to pronounce pahoehoe from online videos if needed. It is par-hoe-i-hoe-i.

You could model the sizes of grains in tephra by bringing in some sand grains, marbles and tennis balls for students to work out in which classification they would fit.

Also, explain the significance of the weather conditions during volcanic eruptions. Wind speed and direction will affect fine ash dispersal. Heavy rain can mix with ash to produce a lahar, which will flow rapidly away from the volcano, following the topography of existing valleys.

1 Tephra is a general term which encompasses material of different sizes. Students should be familiar with the classification and be able to come up with a simple definition of what tephra is.

1 Why do some volcanic eruptions cause more destruction than others?

2 Students should use the classification system to identify how material of different sizes would be classified.

3 The VEI was explored in the previous lesson. If a large eruption occurs, why might the impact reach further from the volcano, and what form will those impacts likely take?

4 The mapping activity is based around an eruption which throws up ash. This is carried by the wind towards the south-west of the vent. The ash builds up to significant depths. A line marking equal depth is called an isopach. Other isolines used in geography include isobars (equal atmospheric pressure), isohyets (equal rainfall) and isotherms (equal temperature).

You may want to tell students that in the 1980 eruption of Mount St Helens, which was a lateral blast, the ash quickly spread ash across the USA and lay 15 cm deep as far away as 15 km from the volcano.

1 Tephra is the general term for all loose rock of various sizes that is thrown out from a volcanic vent.

2 a Fine ash

b Volcanic bomb

c Coarse ash

d Lapilli

3 Volcanic Explosivity Index is a measure of the amount of material ejected during an eruption. If a large amount of fine ash is produced, this can be carried around the globe, potentially in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

4 a The wind direction was north-easterly – remember that winds are named for the direction they come from, not blow towards.

b Approximately 9 km