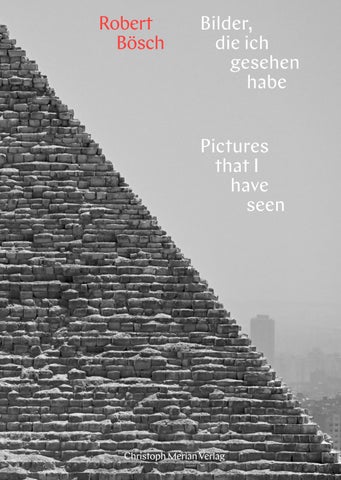

Robert Bösch Bilder, die

ich gesehen habe

Pictures that I have seen

Christoph Merian Verlag

ich gesehen habe

Pictures that I have seen

Christoph Merian Verlag

Pictures that I have seen

Christoph Merian Verlag

Vorwort / Foreword

«Weil er da ist», war die schlichte Antwort von George Mallory 1924 auf die Frage, wieso er den Mount Everest besteigen wolle.

«Weil sie da sind», hätte meine Antwort lauten können auf die Frage, wieso ich diese Bilder machen wollte.

Der Berg war da, die Bilder waren da. Ich musste sie nur erkennen, während Mallory ihn besteigen musste, was er beim Versuch mit seinem Leben bezahlte. Bergsteigen und Fotografie – zwei völlig verschiedene Welten, die beide mein Leben geprägt haben. Während die Intensität und das Können meines Bergsteigens im Verlauf des Lebens bedauerlicherweise, aber naturbedingt nachgelassen haben, begleitet mich die Fotografie nach wie vor und hat mich immer wieder in für mich neue Bereiche weitergehen lassen.

Dieses Buch – ich war auf allen sieben Kontinenten unterwegs – zeigt weder die Welt, noch wie ich diese Welt wahrgenommen habe. Dieses Buch zeigt nur Bilder, die ich gesehen habe. Es sind Ausschnitte, Momente, willkürlich gewählt aus der Unendlichkeit des Sichtbaren. Entkoppelt von der Umgebung, geben sie oft nur einen kleinen Ausschnitt dieser Wirklichkeit wieder, aus der ich sie mit meiner Kamera herausgelöst habe. Wie der Maler sich entscheidet, was auf das leere Viereck seiner Leinwand kommen soll, entscheide ich, was nicht auf das Bild kommt.

Manche meiner Bilder stehen für das, was war, aber mehrheitlich sind sie bildliche, aus dem Zusammenhang gerissene Zitate aus der endlosen Geschichte des Weltenlaufs. Die Bilder stehen nicht für etwas Grösseres, sie stehen nicht für das, was davor oder daneben war, sie stehen für nichts anderes als für sich selbst – wie Monets Seerosen oder Segantinis Berglandschaften.

Ein Bild sagt mehr als tausend Worte. Aber manchmal sagt ein Satz mehr als tausend Bilder. Bilder zeigen, Worte erklären.

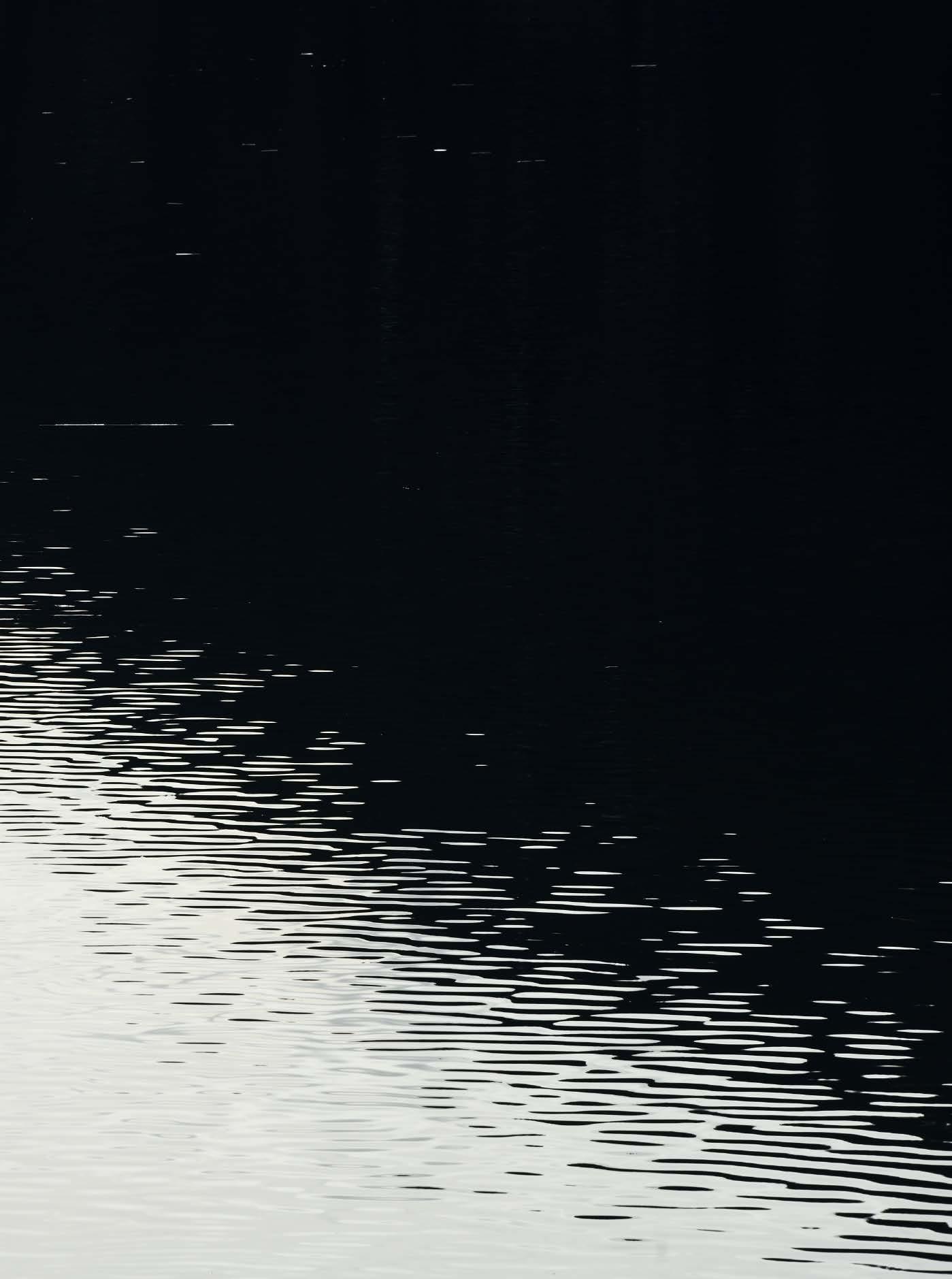

Wer die Welt verstehen will, muss sich an Worte halten. Bilder werden reflexartig «verstanden» und sind deshalb mit Vorsicht zu geniessen. Denn das Meer ist schief, wie die Fotografie auf Seite 136/137 zeigt. Was auf diesem Bild offensichtlich ist, vergisst man oft beim Betrachten von Fotografien: Es ist eine subjektiv wahrgenommene und abgebildete Situation. Bilder zeigen selten und häufig nur ansatzweise, wie es wirklich ist. Fotografie, so wie sie in diesem Buch zur Geltung kommt, verstehe ich als die Kunst, aus dem ‹Alles um uns herum› etwas herauszulösen, das es so eigentlich nicht gibt, das erst losgelöst vom Ganzen eine Eigenständigkeit als Bild bekommt.

Ich bin ein Bild-Suchender. Das macht mein Unterwegssein auf diesem Planeten für mich spannend – egal, ob in einer Stadt, im Gebirge, vor meiner Haustür oder in der Wüste. Mein Fotografenleben lang habe ich versucht, immer einen Schritt weiterzugehen. In den letzten Jahren habe ich gelernt, anders zu schauen, anderes wahrzunehmen – ich habe Neues an Orten entdeckt, die ich

längst kannte, aber so noch nicht gesehen hatte. Manchmal erkenne ich ein Bild auf den ersten Blick. Meist ist es aber ein Herantasten. Ich spüre, dass da ‹etwas ist›, das mich fasziniert, wo ich vermute, dass es ein starkes Bild geben könnte. Mit der Kamera nähere ich mich dem Bild an. Dabei habe ich gelernt, nicht überheblich zu sein und zu glauben, ich wisse schon intuitiv auf den ersten Blick, wie es einzig und allein am besten wird.

Ich täusche mich immer wieder. Bei der Umwandlung der dreidimensionalen Welt in ein zweidimensionales Bild passiert etwas, das ich trotz meiner langjährigen fotografischen Erfahrung nicht komplett im Griff habe. Auch wenn es oft enttäuschend ist: Letztlich ist es wohl dieses Nicht-sicher-Sein, dass das Bild gelingt, was die Fotografie interessant und spannend macht. Ich verändere nachträglich weder den Bildausschnitt noch setze ich etwas ins Bild hinein oder entferne es – weil ich überzeugt bin, dass man dem Misslingen seine Chance erhalten muss. Wo alles machbar ist und gelingt, wird es schnell langweilig und beliebig.

Natürlich weiss ich, nach einem Leben als Fotograf, wie man fotografiert. Aber eigentlich weiss ich immer noch nicht, ‹wie Fotografie funktioniert›.

Jedes Bild hat seine eigenen Gesetze.

Was ein gutes Bild ist, ist ähnlich schwierig zu beantworten wie die Frage, was Kunst ist. Es ist zwar einfach aufzuzählen, was Kunst alles sein kann – ein Filz, Fett, tote Hasen, ein Musikstück, eine Performance, ein Text, Stille, ein Gemälde, eine Verpackung – all das kann Kunst sein. Doch was Kunst ist, kann niemand wirklich sagen.

Ein gutes Bild muss ‹etwas haben›. Es muss eine Kraft haben, Gleichgewicht, Ruhe – oder Ungleichgewicht, Unruhe. Es kann schräg sein, es kann in die Augen springen, es kann leise sein, es kann schrill sein – es muss einfach in sich stimmen. Wie ein guter Film. Wie ein gutes Bild.

“Because it is there”, was George Mallory’s simple answer in 1924 when asked why he was determined to climb Mount Everest.

“Because they are there”, could have been my answer as to why I wanted to take these photographs.

The mountain was there, the pictures were there. I merely had to recognise them, while Mallory had to climb it, for which attempt he paid with his life. Mountaineering and photography – two completely different worlds, each of which have shaped my life. While the intensity and proficiency of my mountaineering has unfortunately, but inevitably, diminished over the course of my life, photography still accompanies me and has always allowed me to explore new areas.

This book – I have travelled to all seven continents – shows neither the world nor how I perceived this world. This book only shows pictures that I have seen. They are excerpts, moments, chosen at random from the infinity of the visible. Decoupled from their surroundings, they often only show a small section of this reality from which I have extracted them with my camera. Just as the painter decides what to put on the empty square of his canvas, I decide what not to put in the picture.

Some of my pictures represent things as they were, but for the most part they are pictorial quotations taken out of context from the endless history of the course of the world. The pictures do not signify something greater, they do not stand for what came before or alongside, they represent nothing other than themselves – like Monet’s water lilies or Segantini’s mountain landscapes.

A picture is worth a thousand words. But sometimes a sentence says more than a thousand pictures. Pictures show, words explain.

Whoever wants to understand the world must stick to words. Images are ‘understood’ reflexively and should therefore be treated with caution. For the sea is askew, as the photograph on page 136/137 shows. What is obvious in this picture is often forgotten when looking at photographs: it is a subjectively perceived and depicted situation. Photos rarely show, and often only rudimentarily, how things really are. I see photography, as is evident from this book, as the art of extracting something from everything around us that doesn’t actually exist, something that only becomes independent as an image when detached from the whole.

I am a picture seeker. That’s what makes travelling the planet so exciting for me –whether in a city, in the mountains, on my doorstep or in the desert. Throughout my life as a photographer, I have always tried to go one step further. In recent years, I have learned to look differently, to perceive things differently – I have discovered new things in places that I have known for a long time but had never seen before. Sometimes I recognise a picture at first glance. Mostly, however,

it’s a case of feeling my way around. I sense that there is ‘something there’ that fascinates me, where I suspect there might be a strong image. I approach the image with the camera. In doing so, I have learned not to be arrogant or to believe that I intuitively know at first glance how it will turn out best.

I err constantly. When transforming the three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional image, something happens that I cannot completely control despite my many years of photographic experience. Even if it is often disappointing: ultimately, it is probably this lack of certainty that the picture will turn out well that makes photography interesting and exciting. I don’t change the framing afterwards, nor do I add to or remove from the picture – because I am convinced that you have to give failure a chance. If everything is feasible and successful, it quickly becomes boring and arbitrary.

Of course, after a lifetime as a photographer, I know how to take pictures. But I still don’t actually know ‘how photography works’.

Every picture has its own laws.

What makes a good picture is as difficult to answer as the question of what art is. It is easy to list everything that art can be – bits of felt, fat, dead rabbits, a piece of music, a performance, a text, silence, a painting, packaging – all of these can be art. But nobody can really say what art is.

A good picture must ‘have something’. It must have strength, balance, calm – or imbalance, restlessness. It can be oblique, it can catch the eye, it can be quiet, it can be shrill – it simply has to be right in itself. Like a good film. Like a good picture.